1. Introduction

1.1. Banana Production and Waste

Banana is cultivated in five continents, in more than 130 countries, and is among the four most significant crops in global production, alongside wheat, rice, and maize. Bananas are predominantly produced in Asia, Latin America, and Africa, and have a particular significance in some of the least developed and low income countries with a food deficit, where they contribute not only to household food as a staple but also to income as a cash crop [

1]. However, production at low-income sites results to a great amount of banana waste due to luck of storage and refrigeration infrastructure. Fruits and vegetables, bananas included, have the highest wastage rates of any food product, with almost half of the production wasted [

2]. Food waste is defined as food and the associated inedible parts removed from the human food supply chain retail, food service, and households [

3]. Ideas for the valorization of banana waste include the use of banana waste as animal feed [

4,

5], in the textile industry [

6,

7,

8], even as an insulator [

9]. Bananas can also be processed and sold in the form of chips [

10,

11] or flour [

12,

13], which helps reduce banana waste. Generally speaking, consumers generate food waste either in the store when deciding what to buy, and in the household when deciding what to consume [

14].

The banana, as a climacteric fruit, presents a decreasing rate of respiration, followed by a sharp increase (respiratory climacteric period), during which a series of biochemical changes occur, such as the autocatalytic production of ethylene and the beginning of fruit ripening [

15]. During the ripening process, the peel changes color from green to yellow, then yellow with brown spots, and finally total black. Moreover, the chlorophyll, responsible for the green color of the fruit peel, degrades, and the perception of carotenoids becomes more apparent. As a result, the green color of the peel becomes yellow. Browning significantly affects quality perception, as it is considered a defect by consumers, thus decreasing liking and willingness to purchase [

14,

16]. The appeal and acceptability of bananas at different stages of ripening varies significantly between consumers and is affected by sensorial reception, emotions, and culture [

17]. To effectively manage banana production and to limit waste, it is necessary to understand consumer perception of bananas ripening stages and banana waste.

1.2. Sensory Attributes of Banana and Consumer Acceptance

The stages of fruit ripeness are key to determining consumer purchase intention. Consumers show different acceptability degrees towards fruits at various degrees of ripeness [

16]. Edible bananas can be classified on the basis of peel color into seven ripeness degrees, usually assigned by using a standardized color chart: (1) totally green; (2) green with yellow traces; (3) more green than yellow; (4) more yellow than green; (5) yellow with green edges; (6) totally yellow; and (7) yellow with brown spots [

18]. Consumers were found to prefer to buy banana from stage 4 to stage 7 [

19]. Food shape abnormality, bananas included, affects purchase intention [

14,

20,

21]. Furthermore, the acceptable level of ripeness can differ between cultures, maybe due to different food preferences between cultures in general [

22].

1.3. Consumer Perception and Emotion Measurement

Understanding consumers’ perception of various degrees of banana ripeness requires a multidisciplinary approach. Studying the entirety of the experience requires explicit and implicit techniques that capture emotional responses elicited by food, beyond sensory liking. It is highlighted in literature that hedonic liking scores are more discriminating that facial expressions, and that explicit self-report of emotions provides the greatest discrimination of all three methods. However, further research to understand the contribution of implicit measures to understanding emotional response, their association with explicit measures and their representation of unconscious response in particular, is required [

23].

Various implicit emotion measurement methods have been developed: physiological and behavioral, each focusing on a different component of emotion. Physiological measures include electroencephalography (EEG), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), electrocardiography (ECG), and skin conductance response measurements, used to measure automatic bodily reactions to emotion elicitation. Behavioral measures include voice tone, pitch, facial expression, bodily expression, and posture measurements, used to measure expression of emotion. One of the methods used to monitor facial expressions and emotional responses to foods is the FaceReader [

24], which can be a useful tool to gain insight into consumer perception [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. It is programmed to recognize six (basic) emotions with 89 percent accuracy: happy, sad, surprised, angry, disgusted, and scared, and the neutral emotional state. Each facial expression gets an intensity value from zero to one, meaning that the expression can be totally absent or fully present, respectively. Habits, nationality, and familiarity with the product have been found to affect the results of FaceReader [

30].

On the other hand, explicit cognitive measures are used to measure feeling, action tendency, and appraisal. In these methods, participants are expected to self-report on how they are feeling by answering questionnaires that depict emotions as cartoons [

31], pictures [

32], or emojis [

33]. PrEmo

® is a popular online non-verbal self-report measurement tool, featuring a hand-drawn character (either male or female) who expresses 14 different emotions (seven positive, seven negative), which was originally developed to measure emotions elicited by product design [

34] and is extensively used in food consumer studies [

35,

36].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology and Samples

Two studies were conducted with European and Chinese participants: In the first study, the emotional reactions of one hundred and thirty-five adults (N=135) of European and Chinese origin [European: 68 (31 male), Chinese: 66 (22 male)] to videos of bananas of various stages of ripeness were assessed, using an implicit method (FaceReader). In the second study, one hundred and thirty-four adults (N=134) of European and Chinese origin [European: 64 (30 male), Chinese: 70 (22 male)], reported their liking and emotional reactions to the same degrees of ripeness, using PrEmo®, an explicit method. All participants were recruited in Birmingham.

Banana samples (Musa Cavendish) were ripened under controlled conditions, in order to produce the samples for the two trials. Bananas were placed in groups of three into separate containers, and ripening was accelerated by ethylene in the incubator at 20

oC in dark conditions, to avoid ripening acceleration due to light [

37,

38]. Banana samples in the boxes were photographed daily to capture ripeness degrees. Five ripeness degrees were used for both studies (

Figure 1).

2.2. Study 1: Measurement of Emotional Responses to Various Degrees of Banana Ripeness Using Facial Expression Analysis

Five videos were filmed, showing consumption of bananas at five degrees of ripeness (green, more green than yellow, all yellow, yellow with brown spots, and total black). For each sample, a model peeled the banana and consumed it, without showing face

1. The testing procedure was carried out according to He et al. (2016) [

39] and Kemp et al. (2009) [

40]. Each video lasted 15 seconds and, in between the videos of banana consumption, a photo (relaxing beach scenery) was shown for ten seconds to reduce transfer of emotions and minimize potential anticipatory effects [

41] (see Supplementary file,

Figure S1).

After this test, participants were asked to answer a grocery shopping attitudes questionnaire. Questions concerned banana eating and purchasing habits to ensure participants were banana consumers and to monitor banana related preferences. Banana shopping cues were divided into external attributes (color, price, brand, sustainability labels), internal sensory attributes (texture, smell, firmness), and credence attributes (depending on consumers’ trust in a brand) (

Figure S2).

2.3. Study 2: Liking and Emotional Responses to Various Degrees of Banana Ripeness Using PrEmo®

Banana photos of the five ripening degrees (same as in study 1;

Figure 1) were used as stimuli for liking rating. Pictures of a model consuming each sample were used for emotion measurement (

Figure S4)

2. The tests were conducted in individual sensory booths. Participants were instructed to watch each one of the five pictures of various degrees of banana ripeness and report liking on 9-point Likert scales (1 = dislike extremely, 9 = like extremely). Then, they were instructed to watch pictures of a model consuming bananas of various degrees of ripeness and report evoked emotions using PrEmo

®, i.e., by rating the 14 emotions from 0 (I do not feel it at all) to 4 (I feel it extremely). The stimuli for both liking and emotion measurement were presented in a randomized order with randomly selected three-digit code labels. After the tests, participants were asked to answer a grocery shopping attitudes questionnaire (same as in Study 1).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Facial expression data were analyzed by FaceReader 7.1 (Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen). All data from FaceReader software were exported as text file for further analysis in Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corp.). Text files contained values of intensity (0 = not expressed; 1 = expressed) of the seven emotional states measured by FaceReader. Mean values (M) and standard deviation (SD) were estimated. The data of the assessments were analyzed using SPSS (IBM SPSS software version 22). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) by Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests (p = 0.005) was used to determine differences among the intensities of the seven emotional states between European and Chinese participants.

Data of liking on 9-point hedonic scale and emotion measurement using PrEmo

® were downloaded from Google Forms and PrEmo

® website respectively were transferred to a Microsoft Excel file. Statistical software SPSS 25 (IBM Deutschland GmbH, Ehningen, Germany) was used to perform all statistical calculations. To test for differences in emotional profiles among different ripeness degrees of banana using PrEmo

®, mixed-model ANOVA’’ s on each emotion and liking (dependent variable) were performed, using participants as a random factor and samples as the fixed factor. Results are reported corrected for Tamhane’‘s’ T2 (T2) (post hoc tests algorithms) with a significance level of p < 0.05. Correlation between liking and each one of the emotions was evaluated by Pearson correlation coefficients (r) [

36] and Spearman correlation coefficients. Logistic multiple linear regression was used to explain the correlations between banana hedonic ratings and emotion measurement from PrEmo

®, mean values were considered at 95% confidence level (p = 0.05), and average values were considered significantly different when P ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Implicit Measurement of Emotional Responses to Various Degrees of Banana Ripeness Using Facial Expresion Analysis

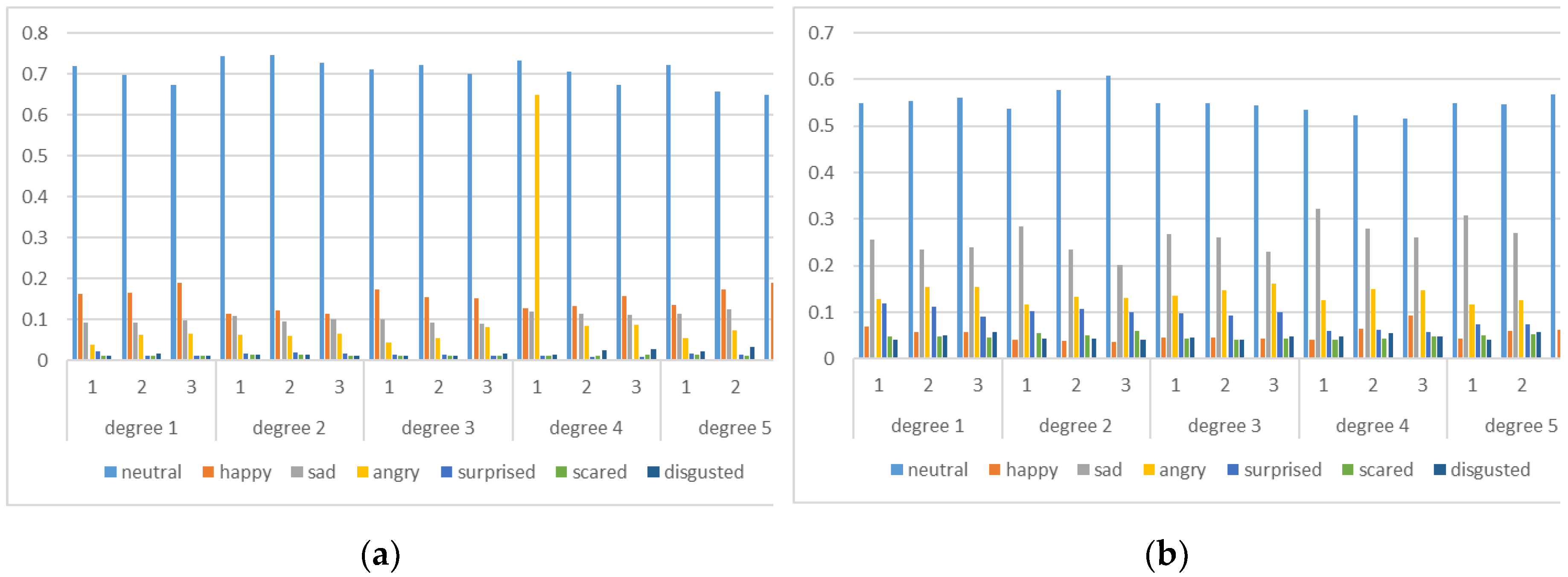

FaceReader measurements of emotional reactions were analysed in three stages (pre - peeling, peeling, and during consumption) and averagely for each ripeness degree (

Figure 2,

Table S2). The neutral emotional state was found to be the dominant one for all participants and all ripeness degrees and comparatively higher for Europeans for all ripeness degrees. Disgust was slightly more intensely felt (or expressed) by Europeans for ripeness degree 5, while by the Chinese for degree 1. The emotion of scare was higher for all degrees for Chinese participants. Surprise was more evident in the Chinese participants. Anger was intense for Europeans for degree 4 only, while for the Chinese it was relatively more intense for all degrees. Happiness was a permanent state for Europeans, while for the Chinese it was significantly lower in general. Sadness was less intense for Europeans, elicited mainly by degrees 1 and 3, while for the Chinese it was relatively higher, elicited mainly by degrees 2 and 4.

3.2. Explicit Self-Report of Liking Various Degrees of Banana Ripeness

European and Chinese participants reported liking ripeness degree 3 the most. Degree 2, degree 1, and degree 4 followed in this order. Degree 5 was the least liked (

Table 1).

3.3. Explicit Self-Report of Emotional Responses to Various Degrees of Banana Ripeness Using PrEmo®

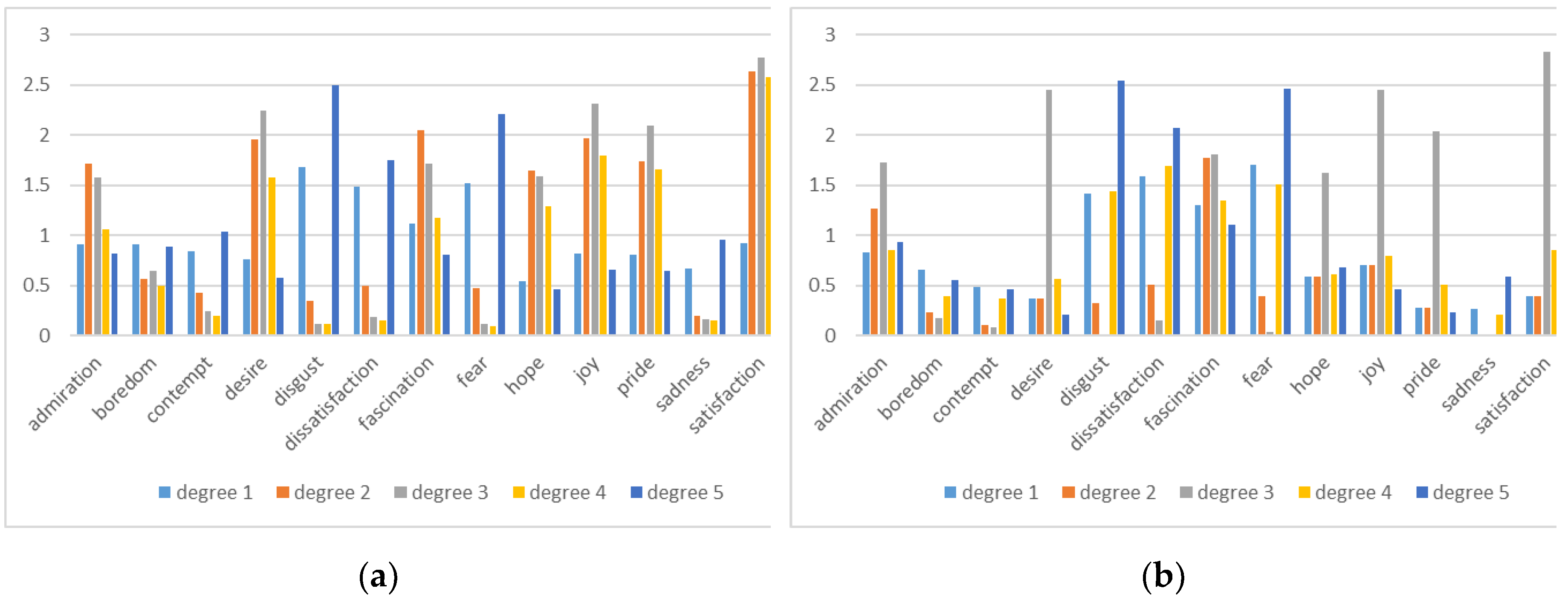

Participants’ emotional reactions were measured using PrEmo

® for all five ripeness degrees. Admiration was higher for degrees 2 and 3 for both Europeans and the Chinese, but in the opposite order. Boredom was rated low for all degrees, the lowest being for degree 3, by both populations. Contempt was also rated low for all degrees, the lowest being for degree 4 by Europeans and degree 2 by the Chinese. Desire was the most intense for degree 3 and the least intense for degree 5 for both Europeans and the Chinese. Disgust was rated the lowest by both populations for degree 3, the highest for degrees 3 and then 3, but the Chinese rated it high for degree 4 as well. Dissatisfaction was at its lowest for degree 4 for Europeans and degree 3 for the Chinese, and at its highest for degree 5 for both cultures, rated high for degree 4 by the Chinese. Fascination was rated the lowest for degree 5 by both populations. Fear was experienced the most by both population for degree 5 and degree 1, but the Chinese rated it high for degree 4 as well. Hope, joy, and pride received high ratings for degrees 2, 3, and 4 by the Europeans, while the Chinese rated it high for degree 3 only. Sadness was generally high by both populations for degrees 5 and 1. Satisfaction was rated the lowest by Europeans for degree 5 and degrees 1 and 2 by the Chinese. Shame was not rated high by any population for any degree, the lowest being for degree 2 by the Europeans and degree 3 by the Chinese (

Figure 3,

Table S3).

4. Discussion

4.1. Acceptance of Banana Ripeness Degrees by European and Chinese Populations

Based on FaceReader and PrEmo

® results combined, the neutral emotional state was the dominant one for all degrees and populations. Walsh et al. (2017) mention that food and eating is a positive everyday experience, making it difficult to observe big differences in consumers’ responses [

41]. It is also mentioned in literature that familiarity greatly affects sensory perception [

42,

43]. Cultural expectations also significantly affect consumer acceptability [

44], and there are significant differences in food preferences and habits between Europeans and the Chinese [

45,

46]. The European participants were more neutral to positive towards all ripeness degrees compared to the Chinese. The shopping preference questionnaire also showed Europeans to be more frequent buyers of banana, and they reported to like it more than the Chinese. Happiness and sadness did not discriminate among ripeness degrees for either population. Happiness was lower for Europeans for degree 2, which might mean that they are more familiar with it and thus do not experience any particular emotion at its sight. Disgust, scare, surprise, and boredom seemed to be irrelevant to banana consumption for both populations and all ripeness degrees, since they received very low ratings. For the Chinese participants, scare was relatively higher for all degrees, and surprise was higher for degrees 1, 2, and 3, which might mean that participants were less familiar with them. The only highly discriminating emotion was anger for degree 4 (pre-peeling stage) for Europeans. This could probably be due to a feeling of anger towards the first sight of food going bad. Both positive and negative emotions provided discrimination among liked and disliked degrees. Negative emotions seemed to discriminate among liked and disliked degrees even better. An interesting finding was that fear co-appeared with disgust indicating that what participants find appalling probably relates to a health hazard in their minds. The Chinese seemed to experience, or express, less intense emotions than the Europeans. Research has shown that Western participants tend to express high arousal emotions when assessing food products, while Asian participants express low arousal emotions [

46]. This could be a hint that implicit measures are more practical and discriminating with Chinese participants, while explicit measures are more suitable for Europeans.

As regards liking of ripeness degrees, degree 3 was liked the most and equally by both populations. Degree 2 followed, with Europeans liking it slightly more than the Chinese. Degree 1 came third in liking for both populations and equally so. Degree 4 came fourth, with Europeans disliking it slightly less than the Chinese. Degree 5 was the most disliked, equally by both populations. The range of allocated ratings also shows that degree 3 is universally liked very much, and degree 5 universally disliked extremely. Furthermore, according to our findings, Europeans seem to accept a wider range of banana ripeness degrees than the Chinese.

Participants’ responses to the grocery shopping questionnaire can shed some light on emotion measurements and liking. Attributes relative to ripeness, namely peel color, firmness, texture, and smell were reported to affect 95.31%, 84.37%, and 73.43% of participants’ purchasing decision, respectively. The stimuli for all measurements in this study were visual only, based on what the first impression of food products is when purchasing them in a store. There was no smelling (which could be considered a limitation) and no tasting (as there is no tasting before purchase). Consumers have to rely on their previous experience of what is edible and what tastes nice, based mainly on visual stimuli.

Ripeness degree 5 received the lowest liking scores and the highest ratings of negative emotions, leading to the conclusion that bananas that look like this (total black) are considered spoiled and non-edible. Based on previous experience, consuming spoiled fruit can cause food poisoning and undesirable health symptoms. As a result, people experience negative emotions [

41], such as disgust and fear. These emotions function as preventors to ensure safety [

47]. This leads to the conclusion that overripe bananas should not be sold as table fruit. Unsold bananas at ripeness degree 4 (yellow with brown spots) should be collected and used as fertilizer, biomass for energy production or mushroom cultivation, animal feed, or for juice and jam production, to name a few of its uses [

48].

According to literature, there is a correlation between banana color, firmness, and sweetness, although not to the same extent for all varieties [

49]. As bananas ripen, there is a degradation of cell wall compounds, leading to softening, starch content reduces and sugar content increases, leading to a sweeter pulp. Consumer acceptance of these attributes depends on personal preference, but could be promoted, as ripe bananas have been found to have increased health benefits. Banana is an excellent source of phenolic compounds, and thus has antibacterial, vasodilatory, and anti-inflammatory properties [

50]. Sulaiman et al. (2011) also stated that banana pulp with higher phenolic compounds acts as a natural antioxidant [

51]. Degree 4 (yellow with brown spots) was the second most disliked, more intensely so by the Chinese. Its health benefits could be promoted to increase acceptability, based on the finding that it has a higher value of total phenolics than unripe fruits [

49], thus decreasing waste. Convincing consumers that visually suboptimal food is still tasty is also of high relevance to waste reduction [

14]. The perceived health effects of food products are found to be more important for Asian consumers than Westerners [

46].

4.2. Comparison between Implicit and Explicit Emotion Measurement Instruments

FaceReader was not able to discriminate among ripeness degrees, which according to literature is attributed to the fact that banana is a widely known and accepted food product. Discrimination is better for products of low consumer acceptance when using implicit measurements [

52]. Nationality and familiarity with the product can also affect FaceReader results [

30]. Participants in this study were familiar with banana and consumed it in various frequencies, which makes distinction even harder. Negative facial expressions are more easily identified than positive ones [

53]. Previous studies mentioned that positive responses were often identified as neutral [

54,

55]. This may explain the intensity of the neutral emotional state measured for all ripeness degrees using FaceReader, if familiarity is not the reason behind this measurement.

PrEmo

® seems to provide clearer discrimination among the various ripeness degrees, especially between liked and disliked ones as verified by liking ratings, probably because it measures more emotional states than FaceReader. However, some of the participants expressed their confusion about the actual meaning of certain emotion depictions and sounds, shame for example. Some understood it to mean “feel shy to eat banana” and others had no idea what emotion the cartoon depicted. Another example is fear, which some confused with surprise. Moreover, as mentioned in King & Meiselman (2010), shyness and surprise are neither positive nor negative emotions

per se [

56]. An insightful comment has been made in Köster & Mojet (2015) who claimed that PrEmo

® was designed to be pleasurable, with a fun cartoon and expressive sounds; thus, there is a risk the pleasantness of the task to unduly influence emotional responses [

57]. More studies are needed for better depiction of emotions via cartoons.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, Europeans and Chinese seem to share a favorite ripeness degree. However, Europeans accept a wider range. Bananas towards the overripe end of the ripeness continuum could be promoted, especially to the Chinese, to extend the acceptable range, by promoting the health benefits of overripe bananas. The Chinese experience or express a wider range of emotions, mainly negative (such as scare and surprise), even at a low intensity, making it easier to discriminate among samples using both implicit and explicit measurements. Europeans are more neutral to positive towards all samples tested, probably because they are more familiar with bananas, and consume it more frequently. To reduce waste, bananas with brown spots could be promoted for their health benefits, and unsold overripe bananas could be collected to be used in the food, energy, and agricultural sectors.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1. The video sequence of samples presentation for facial recognition of emotions using FaceReader.; Figure S2. Grocery shopping questionnaire.; Figure S3. Quantification of color changes and development of brown spots in the same banana during ripening at 18oC and 90% relative humidity (Mendoza & Aguilera, 2004).; Table S1. Mean color intensities and standard deviation (pixels) (as measured by ImageJ software) in banana samples that were used in studies 1 and 2.; Figure S4. Pictures of model consuming bananas of various ripeness degrees provided as stimuli for emotion measurement using PrEmo®.; Table S2. FaceReader results for European and Chinese participants.; Table S3. PrEmo results for European and Chinese participants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ediriisa Mugampoza and Konstantinos Gkatzionis; Data curation, Malamatenia Panagiotou, Christina Ioannou, Lara Hachem and Qiya Huang; Formal analysis, Malamatenia Panagiotou, Christina Ioannou, Lara Hachem and Qiya Huang; Investigation, Malamatenia Panagiotou, Christina Ioannou, Lara Hachem and Qiya Huang; Methodology, Ediriisa Mugampoza and Konstantinos Gkatzionis; Project administration, Ediriisa Mugampoza and Konstantinos Gkatzionis; Resources, Konstantinos Gkatzionis; Supervision, Ediriisa Mugampoza and Konstantinos Gkatzionis; Visualization, Malamatenia Panagiotou, Christina Ioannou, Lara Hachem and Qiya Huang; Writing – original draft, Malamatenia Panagiotou; Writing – review & editing, Konstantinos Gkatzionis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Birmingham (protocol code AP-33431 and 26/7/2024).

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to PrEmo® for supporting this work by providing free access to the tool.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Banana Facts. Available online: https://www.fao.org/economic/est/est-commodities/oilcrops/bananas/bananafacts/en/ (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Food Waste Database. Available online: https://www.fao.org/platform-food-loss-waste/flw-data/en/ (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- the United Nations - Environment Programme Food Waste Index Report 2024; 2024.

- Mohd Zaini, H.; Pindi, W. Banana Peels in Livestock Breeding. In Banana Peels Valorization; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 37–60. ISBN 9780323959377. [Google Scholar]

- Nannyonga, S.; Mantzouridou, F.; Naziri, E.; Goode, K.; Fryer, P.; Robbins, P. Comparative Analysis of Banana Waste Bioengineering into Animal Feeds and Fertilizers. Bioresour. Technol. Reports 2018, 2, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuppuchamy, A.; K., R.; R., S. Novel Banana Core Stem Fiber from Agricultural Biomass for Lightweight Textile Applications. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 209, 117985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, C. V.; Araújo, J.C.; Chaves, D.M.; Fangueiro, R.; Ferreira, D.P. Improving Textile Circular Economy through Banana Fibers from the Leaves Central Rib: Effect of Different Extraction Methods. Food Bioprod. Process. 2024, 146, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Awais, M.; Mohsin, M.; Khan, A.; Cheema, K. Sustainable Yarns and Fabrics from Tri-Blends of Banana, Cotton and Tencel Fibres for Textile Applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 436, 140545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trobiani Di Canto, J.A.; Malfait, W.J.; Wernery, J. Turning Waste into Insulation – A New Sustainable Thermal Insulation Board Based on Wheat Bran and Banana Peels. Build. Environ. 2023, 244, 110740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingayat, A.; V.P., C. Numerical Investigation on Solar Air Collector and Its Practical Application in the Indirect Solar Dryer for Banana Chips Drying with Energy and Exergy Analysis. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2021, 26, 101077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.G.; Paramasivam, P.; Dzida, M.; Osman, S.M.; Le, D.T.N.; Cao, D.N.; Truong, T.H.; Tran, V.D. Development of Advanced Machine Learning for Prognostic Analysis of Drying Parameters for Banana Slices Using Indirect Solar Dryer. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 60, 104743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shini, V.S.; Billu, A.; Suvachan, A.; Nisha, P. Exploring the Nutritional, Physicochemical and Hypoglycemic Properties of Green Banana Flours from Unexploited Banana Cultivars of Southern India. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, L.M.; Rodrigues, F.S.R.; Santos, M.C.B.; Lima, A. dos S.; Nabeshima, E.H.; Leite, M. de O.; Martins, M.A.; Carvalho, C.W.P. de; Maltarollo, V.G.; Azevedo, L.; et al. Green Banana (Musa Ssp.) Mixed Pulp and Peel Flour: A New Ingredient with Interesting Bioactive, Nutritional, and Technological Properties for Food Applications. Food Chem. 2024, 451, 139506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symmank, C.; Zahn, S.; Rohm, H. Visually Suboptimal Bananas: How Ripeness Affects Consumer Expectation and Perception. Appetite 2018, 120, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kader, A. Postharvest Technology of Horticultural Crops (3rd Edition) | Postharvest Research and Extension Center; 2002.

- de Hooge, I.E.; Oostindjer, M.; Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Normann, A.; Loose, S.M.; Almli, V.L. This Apple Is Too Ugly for Me! Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 56, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuprajhaa, T.; Mathav Raj, J.; Paramasivam, S.K.; Sheeba, K.N.; Uma, S. Deep Learning Based Intelligent Identification System for Ripening Stages of Banana. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 203, 112410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Loesecke, H.W. Bananas: Chemistry, Physiology, Technology. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1950, 142, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnato, N.; Klieber, A.; Barrett, R.; Sedgley, M. Optimising Ripening Temperatures of Cavendish Bananas Var. “Williams” Harvested throughout the Year in Queensland, Australia. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 2002, 42, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebnitz, N.; Grunert, K.G. The Effect of Food Shape Abnormality on Purchase Intentions in China. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 40, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nannyonga, S.; Bakalis, S.; Andrews, J.; Mugampoza, E.; Gkatzionis, K. Mathematical Modelling of Color, Texture Kinetics and Sensory Attributes Characterisation of Ripening Bananas for Waste Critical Point Determination. J. Food Eng. 2016, 190, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulmont-Rossé, C.; Drabek, R.; Almli, V.L.; van Zyl, H.; Silva, A.P.; Kern, M.; McEwan, J.A.; Ares, G. A Cross-Cultural Perspective on Feeling Good in the Context of Foods and Beverages. Food Res. Int. 2019, 115, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyts, C.; Chaya, C.; Dehrmann, F.; James, S.; Smart, K.; Hort, J. A Comparison of Self-Reported Emotional and Implicit Responses to Aromas in Beer. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 59, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noldus Facial Expression Recognition Software | FaceReader Available online: https://www.noldus.com/facereader.

- Leitch, K.A.; Duncan, S.E.; O’Keefe, S.; Rudd, R.; Gallagher, D.L. Characterizing Consumer Emotional Response to Sweeteners Using an Emotion Terminology Questionnaire and Facial Expression Analysis. Food Res. Int. 2015, 76, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bommel, R.; Stieger, M.; Visalli, M.; de Wijk, R.; Jager, G. Does the Face Show What the Mind Tells? A Comparison between Dynamic Emotions Obtained from Facial Expressions and Temporal Dominance of Emotions (TDE). Food Qual. Prefer. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Katsikari, A.; Pedersen, M.E.; Berget, I.; Varela, P. Use of Face Reading to Measure Oral Processing Behaviour and Its Relation to Product Perception. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 119, 105209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichierri, M.; Peluso, A.M.; Pino, G.; Guido, G. Health Claims’ Text Clarity, Perceived Healthiness of Extra-Virgin Olive Oil, and Arousal: An Experiment Using FaceReader. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 1186–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, B.; Torrico, D.D.; Hutchings, S.; Ha, M.; Ashman, H.; Warner, R.D. Understanding Consumer Liking of Beef Patties with Different Firmness among Younger and Older Adults Using FaceReaderTM and Biometrics. Meat Sci. 2023, 199, 109124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerrihard, A.L.; Khair, M.B.; Blumberg, R.; Feldman, C.H.; Wunderlich, S.M. The Effects of Acclimation to the United States and Other Demographic Factors on Responses to Salt Levels in Foods: An Examination Utilizing Face Reader Technology. Appetite 2017, 116, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmet, P.M.A.; Hekkert, P.; Jacobs, J.J. When a Car Makes You Smile: Development and Application of an Instrument to Measure Product Emotions. Adv. Consum. Res. 2000, 27, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Collinsworth, L.A.; Lammert, A.M.; Martinez, K.P.; Leidheiser, M.; Garza, J.; Keener, M.; Ashman, H. Development of a Novel Sensory Method: Image Measurement of Emotion and Texture (IMET). Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 38, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, G.; Jaeger, S.R. A Comparison of Five Methodological Variants of Emoji Questionnaires for Measuring Product Elicited Emotional Associations: An Application with Seafood among Chinese Consumers. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmet, P. The Product Emotion Measurement Instrument ( PrEmo ); 2002.

- Gutjar, S.; de Graaf, C.; Kooijman, V.; de Wijk, R.A.; Nys, A.; Ter Horst, G.J.; Jager, G. The Role of Emotions in Food Choice and Liking. Food Res. Int. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Dalenberg, J.R.; Gutjar, S.; ter Horst, G.J.; de Graaf, K.; Renken, R.J.; Jager, G. Evoked Emotions Predict Food Choice. PLoS One 2014, 9, e115388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dairi, M.; Pathare, P.B.; Al-Yahyai, R.; Jayasuriya, H.; Al-Attabi, Z. Postharvest Quality, Technologies, and Strategies to Reduce Losses along the Supply Chain of Banana: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 134, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Koutsidis, G.; Luo, R.; Hutchings, J.; Akhtar, M.; Megias, F.; Butterworth, M. A Digital Imaging Method for Measuring Banana Ripeness. Color Res. Appl. 2013, 38, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Boesveldt, S.; de Graaf, C.; de Wijk, R.A. The Relation between Continuous and Discrete Emotional Responses to Food Odors with Facial Expressions and Non-Verbal Reports. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 48, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, S.E.; Hollowood, T.; Hort, J. Sensory Evaluation: A Practical Handbook. 2013; ISBN 9781118688076. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, A.M.; Duncan, S.E.; Bell, M.A.; O’Keefe, S.F.; Gallagher, D.L. Integrating Implicit and Explicit Emotional Assessment of Food Quality and Safety Concerns. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 56, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Kim, S.-E.; Guinard, J.-X.; Kim, K.-O. Exploration of Flavor Familiarity Effect in Korean and US Consumers’ Hot Sauces Perceptions. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2016, 25, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.-K.; Jombart, L.; Valentin, D.; Kim, K.-O. Familiarity and Liking Playing a Role on the Perception of Trained Panelists: A Cross-Cultural Study on Teas. Food Res. Int. 2015, 71, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.-G.; Lee, S.M.; Sohn, K.-H.; Kim, K.-O. Sensory Characteristics and Cross-Cultural Acceptability of Chinese and Korean Consumers for Ready-to-Heat (RTH) Type Bulgogi (Korean Traditional Barbecued Beef). Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2015, 24, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blancher, G.; Chollet, S.; Kesteloot, R.; Hoang, D.N.; Cuvelier, G.; Sieffermann, J.-M. French and Vietnamese: How Do They Describe Texture Characteristics of the Same Food? A Case Study with Jellies. Food Qual. Prefer. 2007, 18, 560–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunaratne, T.M.; Gonzalez Viejo, C.; Fuentes, S.; Torrico, D.D.; Gunaratne, N.M.; Ashman, H.; Dunshea, F.R. Development of Emotion Lexicons to Describe Chocolate Using the Check-All-That-Apply (CATA) Methodology across Asian and Western Groups. Food Res. Int. 2019, 115, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, A.S.; Choinière, C.J.; Fein, S.B. Practice--Specific Risk Perceptions and Self--Reported Food Safety Practices. Risk Anal. 2008, 28, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose Vazhacharickal, P.; Augustine, A.; Sajeshkumar, N.K.; JohnMathew, J.; Sreejith, P.E.; Sabu, M. By-Products and Value Addition of Banana: An Overview. Int. J. Curr. Res. Acad. Rev. 2021, 9, 64–109. [Google Scholar]

- Suresh Kumar, P.; Shuprajhaa, T.; Subramaniyan, P.; Mohanasundaram, A.; Shiva, K.N.; Mayilvaganan, M.; Subbaraya, U. Ripening Dependent Changes in Skin Color, Physicochemical Attributes, in-Vitro Glycemic Response and Volatile Profiling of Banana Varieties. Food Biosci. 2023, 56, 103274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amri, F.S. Al; Hossain, M.A. Comparison of Total Phenols, Flavonoids and Antioxidant Potential of Local and Imported Ripe Bananas. Egypt. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2018, 5, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, S.F.; Yusoff, N.A.M.; Eldeen, I.M.; Seow, E.M.; Sajak, A.A.B.; Supriatno; Ooi, K.L. Correlation between Total Phenolic and Mineral Contents with Antioxidant Activity of Eight Malaysian Bananas (Musa Sp.). J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagast, S.; Gellynck, X.; Schouteten, J.J.; De Herdt, V.; De Steur, H. Consumers’ Emotions Elicited by Food: A Systematic Review of Explicit and Implicit Methods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendin, K.; Allesen-Holm, B.H.; Bredie, W.L.P. Do Facial Reactions Add New Dimensions to Measuring Sensory Responses to Basic Tastes? Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danner, L.; Haindl, S.; Joechl, M.; Duerrschmid, K. Facial Expressions and Autonomous Nervous System Responses Elicited by Tasting Different Juices. Food Res. Int. 2014, 64, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredie, W.L.P.; Tan, H.S.G.; Wendin, K. A Comparative Study on Facially Expressed Emotions in Response to Basic Tastes. Chemosens. Percept. 2014, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.C.; Meiselman, H.L. Development of a Method to Measure Consumer Emotions Associated with Foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojet, J.; Dürrschmid, K.; Danner, L.; Jöchl, M.; Heiniö, R.-L.; Holthuysen, N.; Köster, E. Are Implicit Emotion Measurements Evoked by Food Unrelated to Liking? Food Res. Int. 2015, 76, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).