1. Introduction

In criminal law enforcement, legal certainty plays an important role in creating order and justice in people’s lives. Legal certainty is one of the fundamental principles in any legal system and is an important aspect of the rule of law. Certainty means “provision or statute,” while if the word “certainty” is combined with the word “law,” it becomes legal certainty, which is interpreted as a legal instrument of a country that is able to guarantee the rights and obligations of every citizen (Nyoman Gede, 2014).

The problem of crime always arises in every society according to its time, and various efforts have been made to overcome it. One of the means of countermeasures used in overcoming crime is to use criminal law. In criminal law, legal certainty has a very important role (Parman, 2012). The principle of legal certainty in the context of criminal law must be written clearly and unequivocally to provide a clear understanding of what acts are considered criminal acts (Best, 2005).

Statistics as a discipline and practice in Indonesia is growing rapidly along with the development of a country’s government and economy. Statistics as a science plays an important role in collecting data on various aspects of business, in industry, and in all fields in the economy (Firdaus, 2021). In Indonesia, legal certainty for statistical crimes is not fully guaranteed. Although there is a legal framework governing the use of statistical data in Indonesia, its implementation still faces challenges (Nazwaraji, 2020). Normatively, there is a legal framework that regulates statistical crimes, but empirically law enforcement of statistical crimes is still not optimal (Sulistomo, 2016).

The current legal framework regarding statistical crimes is contained in Law Number 16 of 1997 concerning Statistics (Statistics Law). Crimes have been regulated in Article 34, Article 36 paragraph (2), Article 37, Article 38, and Article 39 of the Statistics Law. The criminal sanctions that can be given in the context of such statistical crimes have been regulated depending on the level of crime proven (Brown, 2023). Such sanctions include imprisonment, fines, or a combination of both in accordance with the applicable provisions of the law. But in reality, until now there has never been any action against statistical crimes imposed on individuals or corporations (Smith and Doe, 2022).

Article 37 of the Statistics Law emphasizes that the guarantee of confidentiality of information applies also to statistical officers. The confidentiality of information involving statistical officers is important to maintain the integrity of data and the privacy of individuals involved in statistical activities (Shahrullah, Park, and Irwansyah, 2024). In practice, statisticians are usually required to carry out their duties in compliance with high ethics and professional standards, including maintaining the confidentiality of data obtained (Tan, 2021). Statistical officers are non-Civil Servant partners recruited to carry out census/survey activities conducted by BPS. Statistical officers are given employment contracts for a certain period of time with the target of completing the work that has become their duty load.

This research focuses on law enforcement of criminal data leakage acts carried out by statistical officers where the confidentiality of respondents’ information is explicitly guaranteed. Criminal acts of data leakage carried out by statistical officers may violate legal provisions related to privacy, confidentiality, or unauthorized use of data (Irwansyah, 2021). Although there is no specific information regarding related articles in the Statistics Law, in the context of Indonesian law in general, several other laws and regulations may apply in cases of data leakage involving statistical officers (Kristian and Tanuwijaya, 2016).

2. Methods

The method used in this study is an empirical research method. The study used data analysis and facts related to statistical crime cases and law enforcement related to statistical data leaks (Damanik and Shauki, 2019). The study involved interviews with statisticians as the primary data source. The approach taken in this research is an empirical approach or sociological approach. In principle, the empirical approach views law as a phenomenon or reality that exists in society and its relationship reciprocally with other systems outside the law (Juliati and Ludji, 2022).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Essence of Leak Law Enforcement

Illegal acts involving the misuse of data or statistical methods, including data manipulation, falsification of research results, or violations of data privacy, are considered statistical lies. Presumably, lying with statistics involves knowingly spreading false numbers or at least deceptive figures. The results show that the enforcement of statistical crime laws, especially regarding the crime of statistical data leakage by statistical officers, has not been optimal. This finding aligns with Bayu Sulistomo’s research, which examines law enforcement against respondents as legal subjects or perpetrators of statistical crimes and finds that such enforcement does not work effectively (Sulistomo, 2016).

Another study by Dian Hayati Nazwaraji reveals that the use of criminal sanctions in the current Statistics Law has not been effectively integrated with the criminal law enforcement system. This integration includes consideration of law enforcement factors such as legal substance, law enforcement actors, and community factors, as outlined by Soerjono Soekanto (Nazwaraji, 2020). This research focuses on the nature of law enforcement, the potential and obstacles of law enforcement, and the application of ideal law enforcement strategies that can be applied to perpetrators of statistical data leakage crimes.

The essence of enforcing laws against statistical data leakage is to ensure that violations of statistical data security are investigated, prosecuted, and addressed in accordance with applicable laws. The nature of law enforcement for statistical data leakage is related to institutional theory, as described by Lawrence, Suddaby, and Leca, which explains why and how actors in organizations are motivated to make changes to their organizational systems. In this context, a statistical officer appointed to conduct data collection in the field has a motivation that aims to advance the organization, specifically BPS (Badan Pusat Statistik) (Lawrence, Suddaby, and Leca, 2009).

This motivation leads to a sense of responsibility. Immanuel Kant developed a theory of responsibility that is closely related to ethics, emphasizing the importance of individuals as moral agents who act in accordance with moral responsibilities to produce ethical actions. Kant’s theory views responsibility as a moral obligation that individuals must obey. A statistical officer, as a legally appointed individual, must adhere to the rules set by the agency. The officer becomes a moral agent who acts in line with assigned responsibilities, which include not only completing tasks but also adhering to rules related to the work process (Kant, 1785).

Statistical officers are morally responsible for maintaining the confidentiality of data collected in the field, in accordance with Statistics Law Number 16 of 1997, Article 24. According to Kantian ethics, a statistician who maintains data confidentiality throughout their work is engaging in ethical behavior (Kant, 1785).

Based on these theories, the main objectives of law enforcement in this context are as follows:

Law Enforcement: Conduct investigations and identify perpetrators responsible for statistical data leaks. This involves bringing them to court if there is sufficient evidence to support legal action.

Legal Compliance: Ensure that all parties involved in statistical data breaches, both individuals and organizations, comply with applicable laws and regulations regarding the collection, processing, and storage of data.

Victim Protection: Provide protection and support to victims of statistical data breaches, including assistance in recovering lost data and offering necessary information and support.

Crime Prevention: Develop systems and policies to prevent future data leaks. This requires collaboration among different parties to identify vulnerabilities and take steps to strengthen data security.

Appropriate Punishment: Impose suitable and fair sanctions on perpetrators of data leakage in accordance with the law, which may include fines, imprisonment, or other relevant penalties.

Deterrence: Set an example to deter other potential data breaches by applying effective penalties. This helps reduce the motivation to break the law regarding statistical data leakage.

Education and Awareness: Increase awareness about the importance of statistical data security among individuals and organizations through training, guidance, and security awareness campaigns.

Consistency and Fairness: Ensure that law enforcement is carried out consistently and fairly, without discrimination or inequality.

Effective enforcement of laws against statistical data leakage is crucial for maintaining data integrity, protecting personal information, and promoting compliance with data security regulations. By ensuring that statistical data breaches are thoroughly investigated and appropriately addressed, public confidence in the use and storage of data can be strengthened (Smith and Doe, 2022).

3.2. Law Enforcement Barriers to Statistical Data Leakage

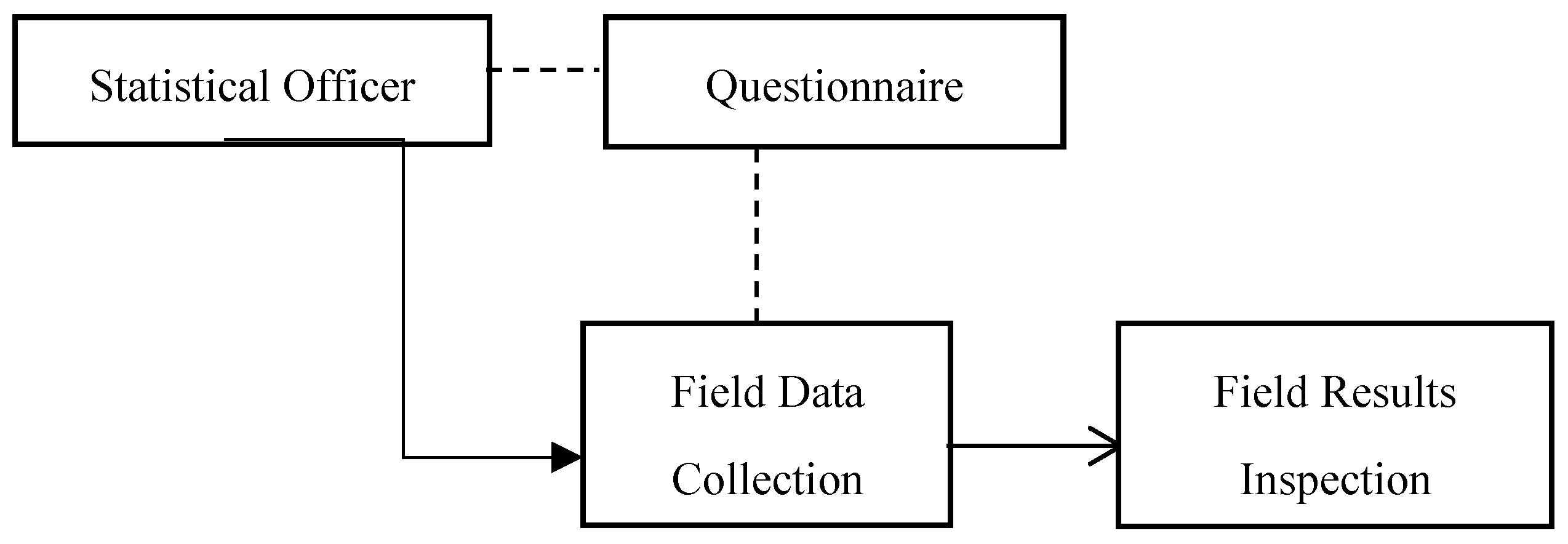

The potential for statistical data leakage refers to the possibility that confidential or sensitive statistical data may fall into the wrong hands or be misused, potentially harming individuals, companies, or governments that own the data (Tan, 2021). There are three types of respondents who may be involved in sample surveys or censuses: individuals/ households, companies, and government institutions or agencies, depending on the type of survey conducted by BPS. Data is collected using two methods: the CAPI (Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing) method, which utilizes a device with a census/survey application installed, and the PAPI (Pencil and Paper Interviewing) method, which involves using questionnaires containing questions asked directly to respondents.

Among these methods, the PAPI method presents the greatest potential for data leakage because the paper questionnaires used by statisticians are highly vulnerable to misuse. Studies have shown that filled questionnaires are often misused by copying them for use in subsequent data collection activities, as some information (e.g., respondents’ identities such as name, NIK, and number of family members) does not change significantly over time (Brown, 2023).

In addition to the data collection process, potential data leakage can occur during the stage of examining field results. This examination stage involves organizing and ensuring the consistency of responses between questions. At this stage, unethical or careless officers might intentionally or unintentionally leak data to third parties, causing fraud that harms BPS (Damanik and Shauki, 2019).

Statisticians are generally not made aware of the importance of maintaining data confidentiality during their training. Training primarily focuses on enhancing the knowledge of officers about surveys without addressing the legal consequences if statistical officers engage in unlawful actions. A lack of awareness among statisticians about the importance of data security can result in inadequate protection measures, making data vulnerable to threats such as social engineering. Social engineering involves manipulating data officers by enticing them to reveal confidential information, thereby creating an entry point for leaking statistical data (Irwansyah, 2021).

Law enforcement against data leakage under Statistics Law Number 16 of 1997 faces several complex obstacles, especially regarding the investigation of data leakage cases. Based on the study results, these obstacles include:

Technical Challenges: Enforcement of data leakage crimes often faces technical hurdles because the offenses under Statistics Law Number 16 of 1997 are categorized as ordinary crimes. In these cases, it is challenging for victims (respondents whose data was leaked) to prove evidence or report the crime to law enforcement authorities (Parman, 2012).

Lack of Resources: Law enforcement efforts are also hampered by a lack of understanding of legal mechanisms and applicable legal rules among BPS personnel. At the BPS regency/city level, there is no special division to handle legal issues, and the legal handling process involves a bureaucratic chain from district/city BPS to provincial BPS, and finally to central BPS. This lengthy process hinders law enforcement, as only the central BPS has divisions or bureaus responsible for legal matters (Kristian and Tanuwijaya, 2016).

Incompatibility of Laws and Regulations: There are inconsistencies in the application of laws and regulations concerning law enforcement at BPS. Current threats of punishment for technical and moral violations by statistical officers are limited to employment termination as an ultimatum of remedium. So far, BPS has not enforced criminal sanctions listed in the Statistics Law as an ultimatum of remedium for violations or statistical crimes (Shahrullah, Park, and Irwansyah, 2024).

To address these obstacles, it is necessary to raise legal awareness, particularly regarding the Statistics Law, among BPS employees at the district/city level, statistical officers, and respondents. Special training is needed to enhance the legal understanding of BPS employees. Furthermore, legal certainty is required regarding the level of offenses and crimes to determine appropriate punishments. Overcoming these barriers is the first step toward ideal law enforcement at BPS, especially concerning the crime of statistical data leakage (Tan, 2021).

3.3. Law Enforcement: Ideal Statistical Data Leak

Enforcing laws related to statistical data leakage is essential to protect data integrity and confidentiality and provide a deterrent effect against criminal behavior. According to G. Peter Hoefnagels, crime policy is “the rational organization of social reaction to crime” (Hoefnagels, 1969). Law enforcement for criminal acts can follow two paths: penal (using criminal law) and non-penal (non-criminal) measures.

Currently, the enforcement of laws against statistical data leakage primarily uses non-penal measures due to the high level of humanity considered in decision-making processes. The lengthy bureaucratic procedures, from district/city to provincial and central levels, also influence the resolution of data leakage crimes using non-penal measures, with the most severe punishment being the termination of employment contracts between BPS and statistical officers (Damanik and Shauki, 2019).

In line with Das Sollen, enforcement of data leakage crimes should refer to Statistics Law Number 16 of 1997, Article 37, where statistical officers who deliberately violate confidentiality provisions are subject to a maximum imprisonment of 1 year and 6 months and a maximum fine of Rp.15,000,000 (fifteen million rupiahs). The penal path focuses on repressive actions after a criminal act has occurred, while non-penal measures focus on preventive actions before a crime takes place (Nazwaraji, 2020).

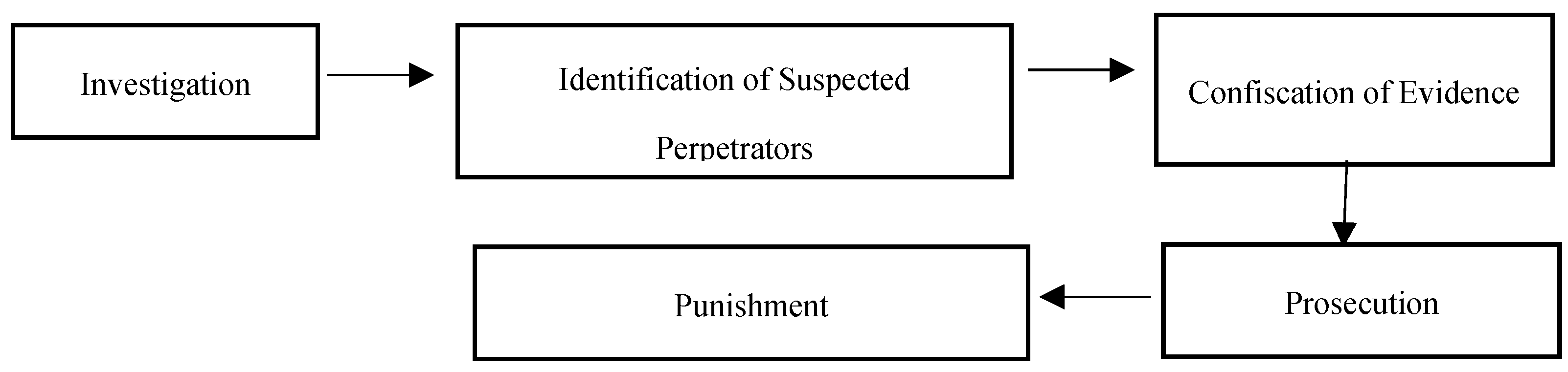

The study findings indicate that law enforcement against statistical data leakage crimes can follow the penal route outlined in Statistics Law Number 16 of 1997, Article 37. An investigation is the initial step in law enforcement, aiming to determine whether a crime has occurred. This is followed by an investigation to collect evidence, clarify criminal acts, and identify suspects. Investigation is thus a follow-up to the investigative process, carried out when preliminary results suggest a criminal act has been committed (Sulistomo, 2016).

Given the obstacles to enforcing data leakage laws at BPS, it is crucial to provide legal certainty through strict rules and limits regarding the severity of data leakage. BPS employees at the district/city level, who directly interact with statistical officers, should be equipped with an adequate understanding of law enforcement. Overcoming these barriers will enable the formulation of effective law enforcement policies for statistical data leakage (Nazwaraji, 2020). Some Formulations for Law Enforcement Against Statistical Data Leakage:

Investigation: If there is a suspicion of data leakage, the first step in law enforcement begins with investigating the primary source and assessing the extent of the damage caused by the crime. BPS at the district/city level can involve law enforcement officials to gather evidence and understand the data leakage process (Kristian and Tanuwijaya, 2016).

Identify the Alleged Perpetrator: Identifying the perpetrators of data leaks is a critical step. This may involve tracing the origin of the leak, identifying who is responsible, and understanding the motives behind the data leak. Perpetrators may include statistical officers or others who might have negligently handled questionnaires, leading to unauthorized access and subsequent leakage (Brown, 2023).

Confiscation of Evidence: Law enforcement will collect strong evidence for use in court, which may include questionnaires or other related items, such as duplicated copies. Evidence related to data leakage will be crucial (Damanik and Shauki, 2019).

Prosecution: Once sufficient evidence is gathered, law enforcement will bring the perpetrator to justice. This involves legal proceedings where the perpetrators face charges related to data leakage. BPS plays a crucial role in overseeing these legal procedures (Nazwaraji, 2020).

Punishment: If found guilty, the perpetrators of data leakage may be subject to legal sanctions. Penalties are in accordance with Statistics Law Number 16 of 1997, Article 37, which stipulates a maximum imprisonment of 1 year and 6 months and a maximum fine of Rp.15,000,000 (fifteen million rupiahs) (Shahrullah, Park, and Irwansyah, 2024).

In addition to penal sanctions, non-penal measures can also be applied. This includes the dismissal of the perpetrator from employment and compensating victims for losses incurred due to the data leak. Compensation could cover financial losses, recovery costs, or damage to reputation. Non-penal measures may also involve providing guidance on preventing future data leaks and assisting victims in recovering leaked data. Addressing statistical data leaks effectively often requires collaboration between public and private sectors (Smith and Doe, 2022).

The enforcement of laws related to statistical data leakage is critical for maintaining the integrity and confidentiality of data, as well as for providing a strong deterrent effect against criminal behavior. As noted by Hoefnagels (1969), crime policy should be a rational organization of social reactions to crime, and this principle applies to the realm of statistical data protection. Currently, the approach to law enforcement in cases of statistical data leakage tends to favor non-penal measures due to a focus on humane decision-making and the practical difficulties posed by bureaucratic processes (Damanik and Shauki, 2019). However, for law enforcement to be truly effective, it must balance both penal and non-penal strategies.

The application of penal measures, as outlined in Statistics Law Number 16 of 1997, Article 37, provides a clear legal framework for punitive actions against deliberate breaches of data confidentiality. The penal path, which includes imprisonment and fines, serves a repressive function to punish wrongdoing and prevent future violations (Nazwaraji, 2020). This repressive approach is essential in cases where the severity of the data breach justifies such measures, ensuring that justice is served and setting a precedent to deter potential offenders.

However, effective law enforcement also requires a robust investigative process to determine whether crimes have occurred, collect evidence, and identify suspects (Sulistomo, 2016). This process must be handled with precision to ensure that perpetrators are accurately identified and held accountable. As such, it is crucial for BPS employees, especially those at the district/city level who work closely with statistical officers, to have a clear understanding of law enforcement procedures and their roles in upholding data protection laws (Nazwaraji, 2020).

Addressing the systemic barriers to law enforcement—such as bureaucratic inefficiencies and lack of legal awareness among BPS staff—can significantly enhance the effectiveness of both penal and non-penal measures. By streamlining the law enforcement process and providing adequate training, BPS can ensure that its employees are well-equipped to handle cases of data leakage, thereby strengthening the overall framework for data protection. The commitment to improving both punitive and preventive measures will ultimately lead to a more secure and reliable statistical system, benefiting individuals, companies, and government agencies that rely on accurate and confidential data.

4. Conclusions

The enforcement of laws against statistical data leakage is essential not only for legal compliance but also for maintaining trust, data integrity, and privacy. This study shows that a dual approach—combining penal measures, as outlined in Statistics Law Number 16 of 1997, with non-penal strategies like education and prevention—offers a comprehensive framework for effectively addressing data breaches. Penal measures serve as a deterrent and punishment for violators, while non-penal measures focus on fostering a culture of ethical behavior and legal awareness among statistical officers and BPS employees.

To ensure effective enforcement, it is crucial to strengthen legal certainty and support these efforts with robust investigative processes. By addressing systemic barriers such as bureaucratic inefficiencies and enhancing coordination between public and private sectors, the legal framework can become more responsive and adaptable to emerging data security challenges. Committing to both preventive and punitive measures will not only protect individual privacy and uphold data integrity but also build a more secure and reliable statistical system, fostering public trust and informed decision-making.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Gusti Anom Wijaya and Aswanto; Methodology, Gusti Anom Wijaya, Aswanto, and Musakkir; validation, Gusti Anom Wijaya and Aswanto; investigation, Gusti Anom Wijaya; resources, Gusti Anom Wijaya and Ahsan Yunus; data curation, Gusti Anom Wijaya; writing—original draft preparation, Gusti Anom Wijaya; writing—review and editing, Gusti Anom Wijaya and Ahsan Yunus; supervision, Aswanto, Musakkir, and Muhadar. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bayu Sulistomo (2016) ‘Optimization of the implementation of basic statistical activities through the reform of Law Number 16 of 1997 concerning Statistics’. Thesis. Atmajaya University, Yogyakarta.

- Best, J. (2005) ‘Lies, calculations, and constructions: Beyond “How to Lie with Statistics”‘, Journal of American Culture, 20(3), pp. 211.

- Brown, E. (2023) ‘The role of legal frameworks in preventing data breaches in the public sector’, Journal of Cybersecurity Law, 11(2), pp. 100-122.

- Damanik, S. and Shauki, E.R. (2019) ‘Opinion analysis of BPK RI examination results report (Study on the Indonesian Maritime Security Agency)’, Indonesian Treasury Review Journal of State Treasury and Public Policy, 4(4), pp. 166.

- Firdaus, M. (2021) Econometrics: An Applicative Approach. Jakarta: PT Bumi Aksara.

- Hoefnagels, G.P. (1969) The other side of criminology: An inversion of the concept of crime. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Irwansyah. (2021) Legal Research on Choice of Article Writing Methods and Practices. Revised edition. Yogyakarta: Mirra Buana Media.

- Juliati, E.S. and Ludji, I. (2022) ‘Infodemic in the middle of a pandemic according to the perspective of Immanuel Kant’, Journal of Theology & Christian Education, 18(2), pp. 187.

- Kant, I. (1785) Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kristian and Tanuwijaya, K. (2016) ‘Criminal formulation policy against corporations as perpetrators of money laundering in Law Number 8 of 2010 concerning the prevention and eradication of money laundering’, Journal of the Pulpit of Justitia, 2(1), pp. 691.

- Lawrence, T.B. , Suddaby, R. and Leca, B. (2009) ‘Institutional work: Actors and agency in institutional studies of organizations’, Cambridge University Press.

- Nazwaraji, D.H. (2020) ‘Policy on reformulation of criminal sanctions law number 16 of 1997 concerning statistics’, Khairun Law Review, 1(1), pp. 34.

- Nyoman Gede, R. (2014) ‘Legal meaning and legal certainty’, Kertha Widya, 2(1), pp. 2.

- Parman, L. (2012) ‘Reorienting the thought of using criminal law as a means of crime reduction’, Jatiswara, 27(1), pp. 173.

- Shahrullah, R. , Park, J. and Irwansyah, I. (2024) ‘Examining personal data protection law of Indonesia and South Korea: The privacy rights fulfilment’, Hasanuddin Law Review, 10(1), pp. 1-20.

- Smith, J. and Doe, J. (2022) ‘Ensuring data security in government statistical offices: Challenges and solutions’, Journal of Information Security and Applications, 5(1), pp. 45-67.

- Sulistomo, B. (2016) ‘Optimization of the implementation of basic statistical activities through the reform of Law Number 16 of 1997 concerning Statistics’. Thesis. Atmajaya University, Yogyakarta.

- Tan, M. (2021) ‘Ethical implications of data leakage: A case study in public sector statistics’, Journal of Public Administration and Policy Research, 7(4), pp. 205-220.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).