1. Introduction

Adolescence is a unique and formative time. Unfortunately, about one in seven adolescents, translating to an estimated 166 million adolescents globally, experience mental illnesses [

1]. Major mental illnesses include anxiety, depression, and health risk behaviors, such as illicit drug use, smoking, drinking, and suicidality. While a recent study [

2] using the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) data of 2001-2021 shows a decreasing trend of drug use in the United States, it is the opposite of the case in certain southern states of the country. Consequently, adolescents are often victims of negative mental health outcomes, developmental issues, and threats to brain functions, resulting in short- and long-term mental illnesses [

3,

4].

The global pandemic of COVID-19 has had a profound impact on the mental health of individuals globally. Factors such as the continued fear of infection and death due to the virus, the insecurity of resources, and social isolation contributed to the rise in mental health issues during the pandemic [

5,

6]. The United States Surgeon General warned against the public health crisis and the potential increase in the risk of mental health problems due to the COVID-19 pandemic [

7]. Among all nations in the world, the burden of COVID-19 cases in India was second, only next to the United States [

6].

As a result of social isolation and the continued fear of infection and death due to the virus, negative mental health consequences that are associated with the COVID-19 crisis are monumental [

8,

9]. Researchers have focused more of their attention to the mental health impact of this rapidly evolving global crisis in the elderly population [

10], and with less attention being given to the psychological toll of COVID-19 on adolescent mental health [

11]. Threats to adolescents’ mental health worsened after COVID-19, due to school closures, repeated periods of quarantine, lack of children’s recreational facilities, social distancing, loss of loved ones, and loneliness, among many [

12,

13]. The mental health toll of the COVID-19 pandemic among youth and adolescents serves as a greater challenge because people of this age lack the psychological maturity, coping techniques, and mental resilience of adults [

14,

15].

Adolescent mental health in India is even worse, and the reasons are multiple. Despite progress in improving access to health care, inequalities based on socioeconomic status, rural-urban differences, and gender differences in health care continue to persist in several parts of India [

16]. This is compounded by the lack of healthcare access for most socioeconomically disadvantaged people in the rural communities of India. A recent study in India [

17] suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic may put adolescents at an increased risk of school dropout, gender gaps in education, increased child labor, stress, smartphone dependence or addiction, early age initiation of smoking, drinking, or drug addiction, exposure to violence, neglect, and exploitation including sexual abuse/maltreatment. Another narrative review article on COVID-19 and the effects of lockdowns on the mental health of children and adolescents suggested implementing an evidence-based plan of action for the psychosocial and mental health needs of vulnerable children [

18].

In this context, there is a pressing need to fill in the gap in our knowledge about risk identification and the prevalence of mental health issues among adolescents due to the COVID-19 pandemic in underprivileged rural communities so that further strategies can be initiated to prevent poor mental health outcomes of the people in these communities. The present study aimed to determine the prevalence of and risk factors for predicting anxiety and depression among adolescents in rural India.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Study Design

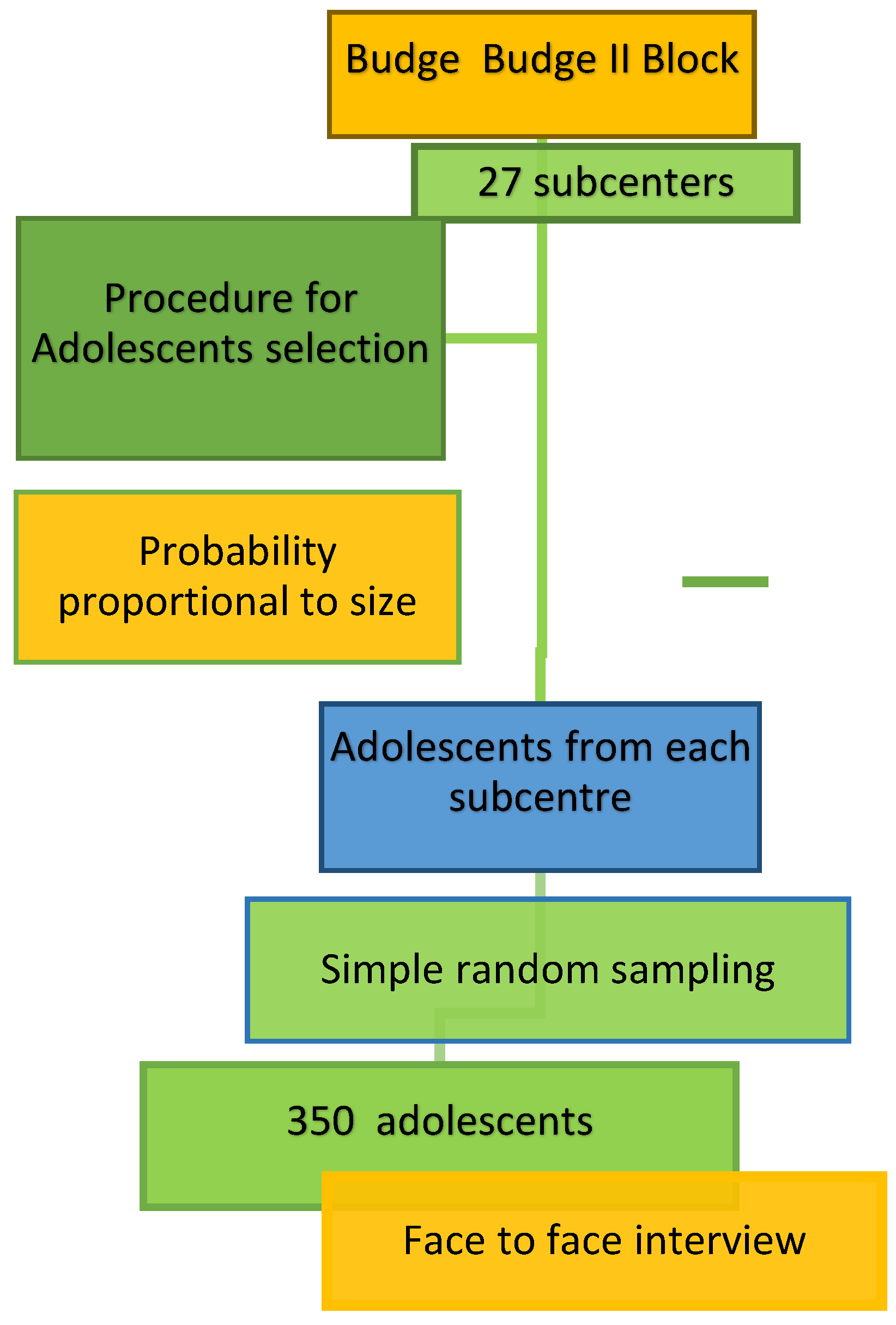

A cross-sectional community-based study was conducted among the adolescents residing under the aegis of the 27 subcenters of Budge-Budge II Block, West Bengal from January-June 2023. The rural field practice areas of the Institute of Post-Graduate Medical Education and Research (IPGME&R), Kolkata are in Budge Budge II Block of South 24 Parganas district of West Bengal. The study areas are shown in

Figure 1.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Adolescents between 10-19 years of age and those residing in the study area for more than 3 years were included in this study. Those participants previously having any mental health disorders either self-reported or diagnosed by a doctor, or with any ongoing major health issues (such as congenital disease, other comorbidities – pneumonia, asthma, heart disease, etc.) or were absent from their homes during the data collection period on three separate occasions were excluded from the study.

2.3. Sample Size Estimation

The major variable of interest in the study was the prevalence of depression. We used the study reported by Shah and Bhattad (2022), in which the prevalence of depression was 13% among patients following COVID-19 [

4]. We calculated the sample size using the following formula:

Here, the proportion of the people with depression, p = 13% or 0.13

q = 1 – p = 0.87

Z = 1.96 for α = 0.05 (having 95% confidence)

Absolute precision, d = 4%

Adjusting for a non-response rate of 15%, the minimum required sample size was 313; while we collected data from 350 eligible adolescents.

2.4. Sampling Technique

The sampling frame was obtained from the line list of households with adolescents maintained at the subcenters. From each subcenter, the number of adolescents was selected by random sampling of subcenters according to the probability proportional to size. The adolescents from each subcenter were then selected by simple random sampling without replacement until the desired number of adolescents (

n = 350) was included. Accredited Social Health Activists (

ASHA) from the respective areas helped identify the selected households. Two trained research assistants from IPGME&R visited randomly selected households (

Figure 2).

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) of IPGME&R/SSKMH hospital (letter number IPGME&R/IEC/2023/047, dated 21 January 2023). Informed written consents and assents (above age 7) were taken before enrollment. The study objectives and the procedures were explained before the informed consent was obtained. Participation in the study was completely voluntary, and the participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any time during the study. They were assured about the anonymity, confidentiality of the data, and risks and benefits. No body samples (such as blood or urine) were obtained.

2.6. Study Tools and Techniques

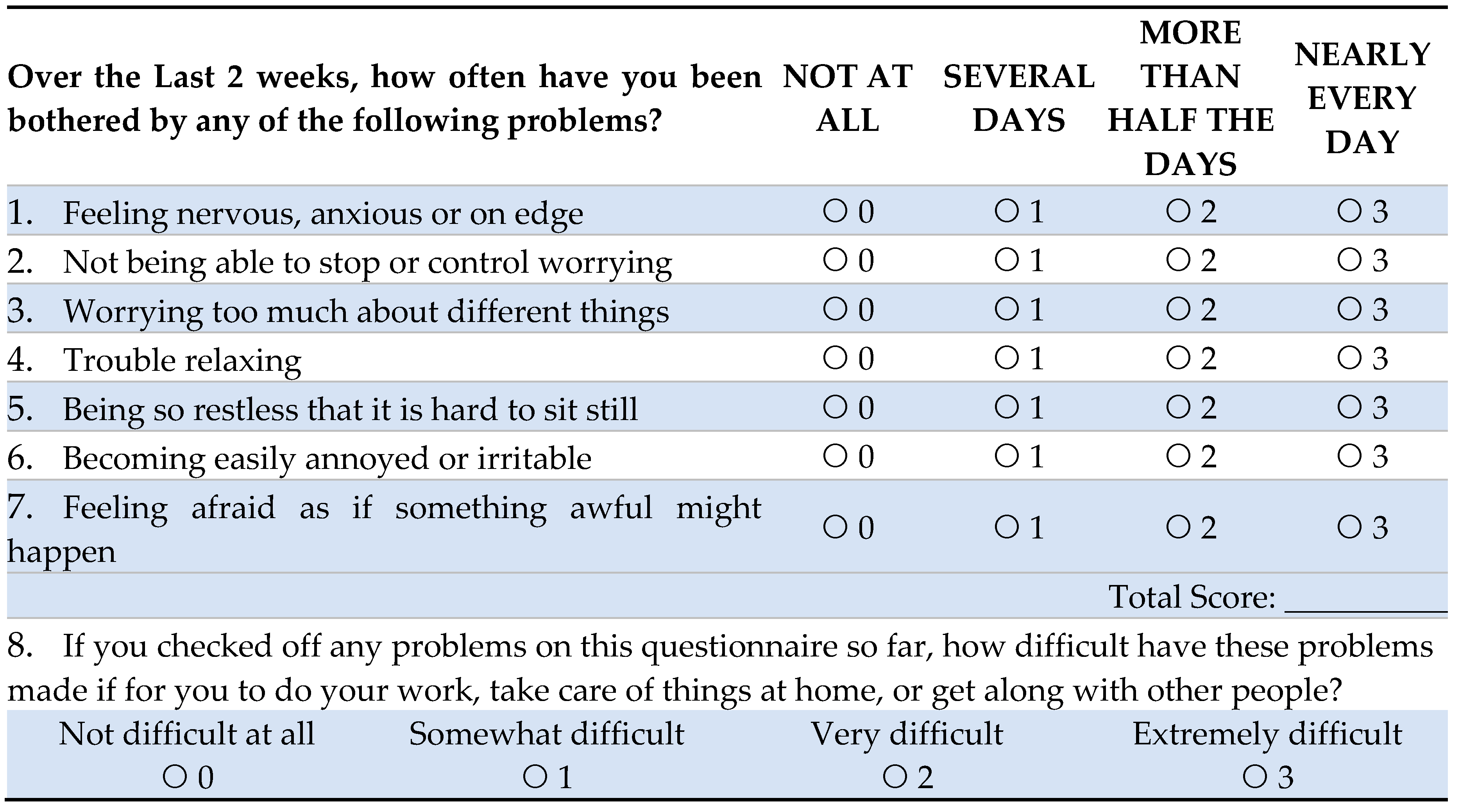

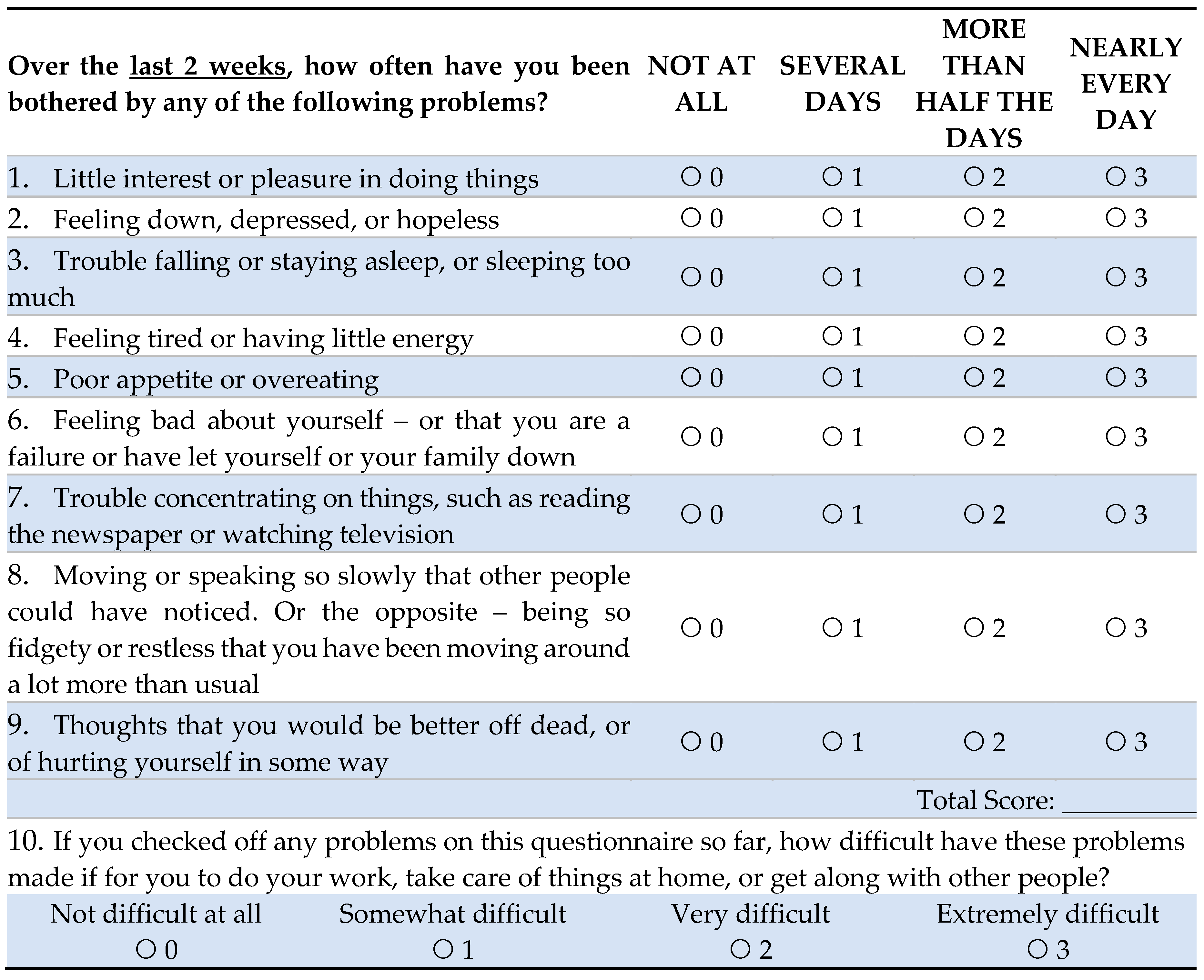

A predesigned, pretested, structured data instrument was used to collect data. The data instrument included the following: Demographic data, a Covid-related questionnaire, and two standardized questionnaires: a) Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9, and b) Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)-7 scales [

19,

20]. PHQ is a 9-item screening method that offers concise, self-administered tools for assessing depression. Participants will choose 1 of 4 responses about the frequency of depression during the previous two weeks. PHQ-9 scores >10 has a sensitivity of 0.88 (95% confidence intervals, 0.82 to 0.92) and a specificity of 0.86 (95% CI, 0.82 to 0.85) for major depressive disorder [

21]. GAD-7 has a sensitivity of 0.83 (95% CI, 0.71 to 0.91) and a specificity of 0.84 (95% CI, 0.70 to 0.92) for screening anxiety disorders [

22]. Both questionnaires have been extensively used around the world to assess mental health status. All questionnaires, including PHQ-9 and GAD-7, were translated from English to the local language (Bengali), and back-translated, as 98% of the study population spoke Bengali. A pre-tested Bengali version of the instruments was incorporated for data collection.

The local communities were approached, and households were identified by ASHA workers of the area. Trained interviewers made house-to-house visits to the selected households to administer the questionnaire. Data collection was monitored by the researchers to ensure quality.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were entered, cleaned, and analyzed by using SPSS (version 29, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). We assessed the data distribution by conventional methods, such as descriptive analysis, histogram, Boxplot, Q-Q plot, normality plot, and Shapiro-Wilk Test of Normality. The total numerical depression scores and anxiety scores were categorized as follows: none-to-minimal (scores 0-4); mild (scores 5-9); moderate (scores 10-14), and severe (scores 15 and above). The numerical values of monthly family income were categorized into four income groups. The major outcome variables being categorical (e.g., presence or absence of depression and anxiety), Chi-square tests were computed between age groups and gender with the outcome variable categories. A bivariate correlation test was computed between depression and anxiety numerical scores with the demographic variables. The variables that were found statistically significant in the correlation test were used in multiple linear regression model analyses to determine the independent risk factors or predictors of the dependent variables, anxiety and depression scores. A p-value of 0.05 was used for statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. COVID-19 and General Health

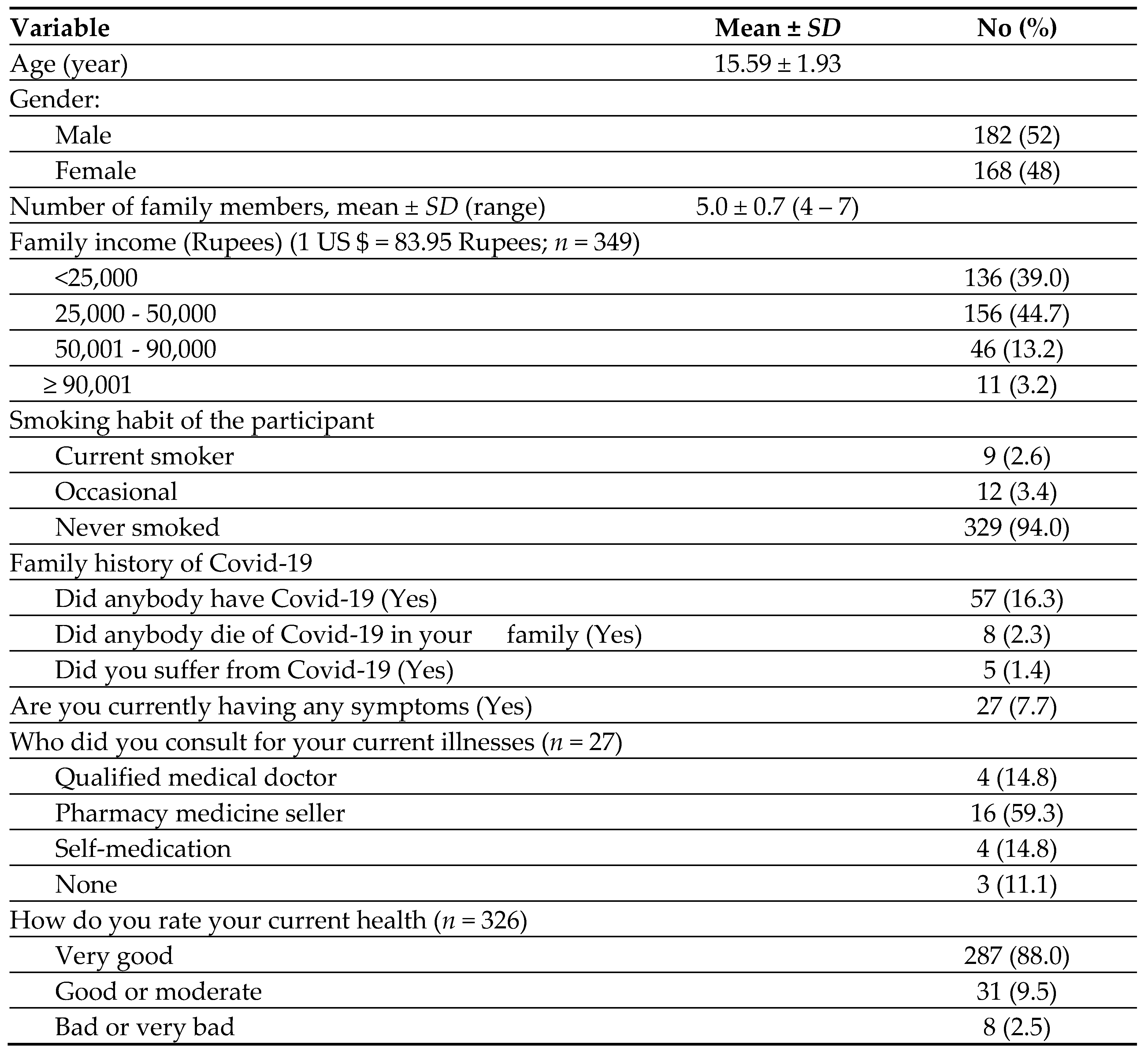

The study included 350 adolescents and had no dropouts. As mentioned in

Table 1, the mean ±

SD age of the participants was 15.56 ± 1.93. As expected, most of the families were from lower economic groups, because the study was conducted in rural areas of West Bengal, India.

Among the adolescents, 57 (16.3%) had occurrences of COVID-19 and 8 (2.3%) had COVID-19 deaths in the family. Twenty-seven of the adolescents reported having current illnesses at the time of the interview. Of those who had symptoms (

n = 27), the majority (59.3%) asked pharmacy sellers for their medication, and 4 (14.8%) used self-medication. Most of the symptoms were related to upper respiratory infections such as sore throat and cough but no fever. Only 3 adolescents thought they might have anxiety or depression. When asked about their overall health, the majority (88%) rated their health “very good” and about 10% mentioned it “good or moderate” (

Table 1).

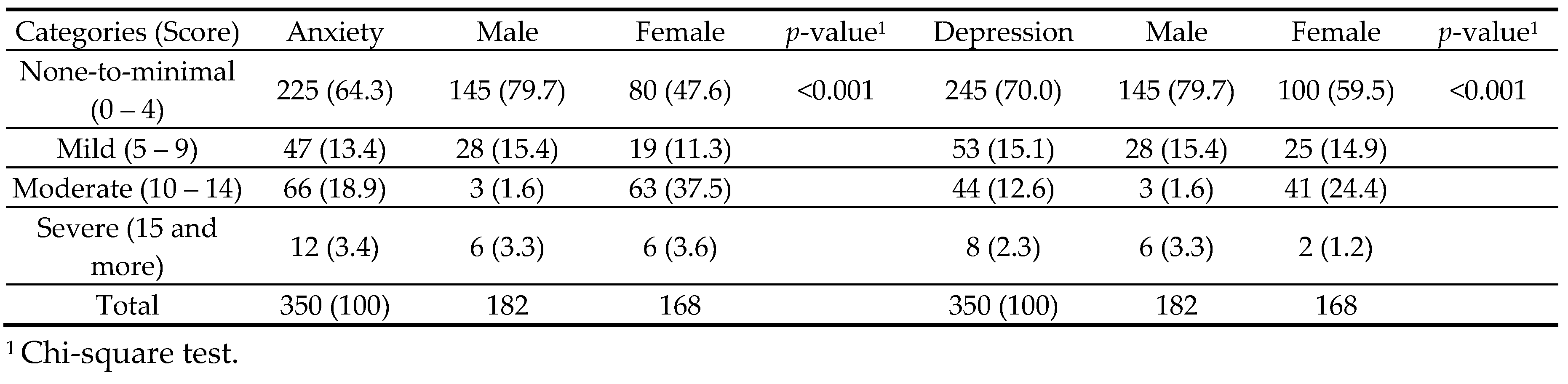

3.2. Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression

Table 2 shows that 125 (35.7%) of the adolescents had anxiety and 105 (30.0%) had depression. Of the four categories of severity scores (none-to-minimal, mild, moderate, and severe), females had significantly higher severity of both anxiety (

p <0.001) and depression (

p <0.001) compared with males.

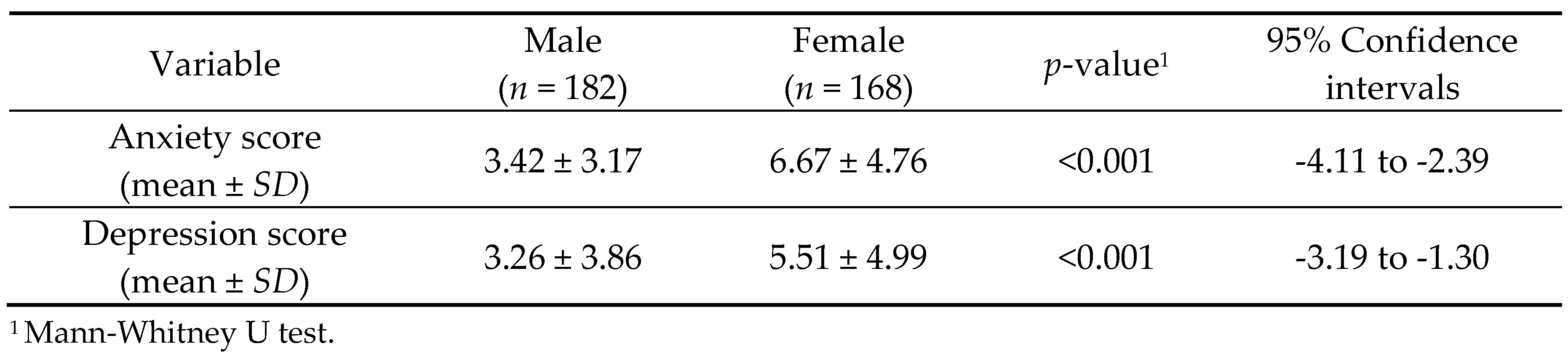

Table 3 shows that the mean ±

SD scores of anxiety and depression were significantly higher in females than males (6.67 ± 4.76

vs. 3.42 ± 3.17, respectively for anxiety,

p <0.001) and (5.51 ± 4.99

vs. 3.26 ± 3.86, respectively for depression,

p <0.001). Because of the non-normal distribution, we used Mann-Whitney U Tests to determine the gender differences in the anxiety- and depression scores.

3.3. Association between COVID-19 Cases in the Family with Anxiety and Depression

Mean ±

SE scores of anxiety and depression were compared between adolescents who had COVID-19 cases in the family (

n = 57) and those who did not (

n = 293). For anxiety, those who had COVID-19 cases in the family showed significantly higher GAD-7 scores compared with those who did not have COVID-19 cases in the family (6.79 ± 2.59

vs. 4.62 ± 4.50, respectively, Mann -Whitney U

p-value <0.001) (

Figure 3).

For depression, those who had COVID-19 cases in the family showed significantly higher PHQ-9 scores compared with those who did not have COVID-19 cases in the family (8.47 ± 2.41

vs. 3.54 ± 4.47, respectively, Mann -Whitney U

p-value <0.001) (

Figure 3).

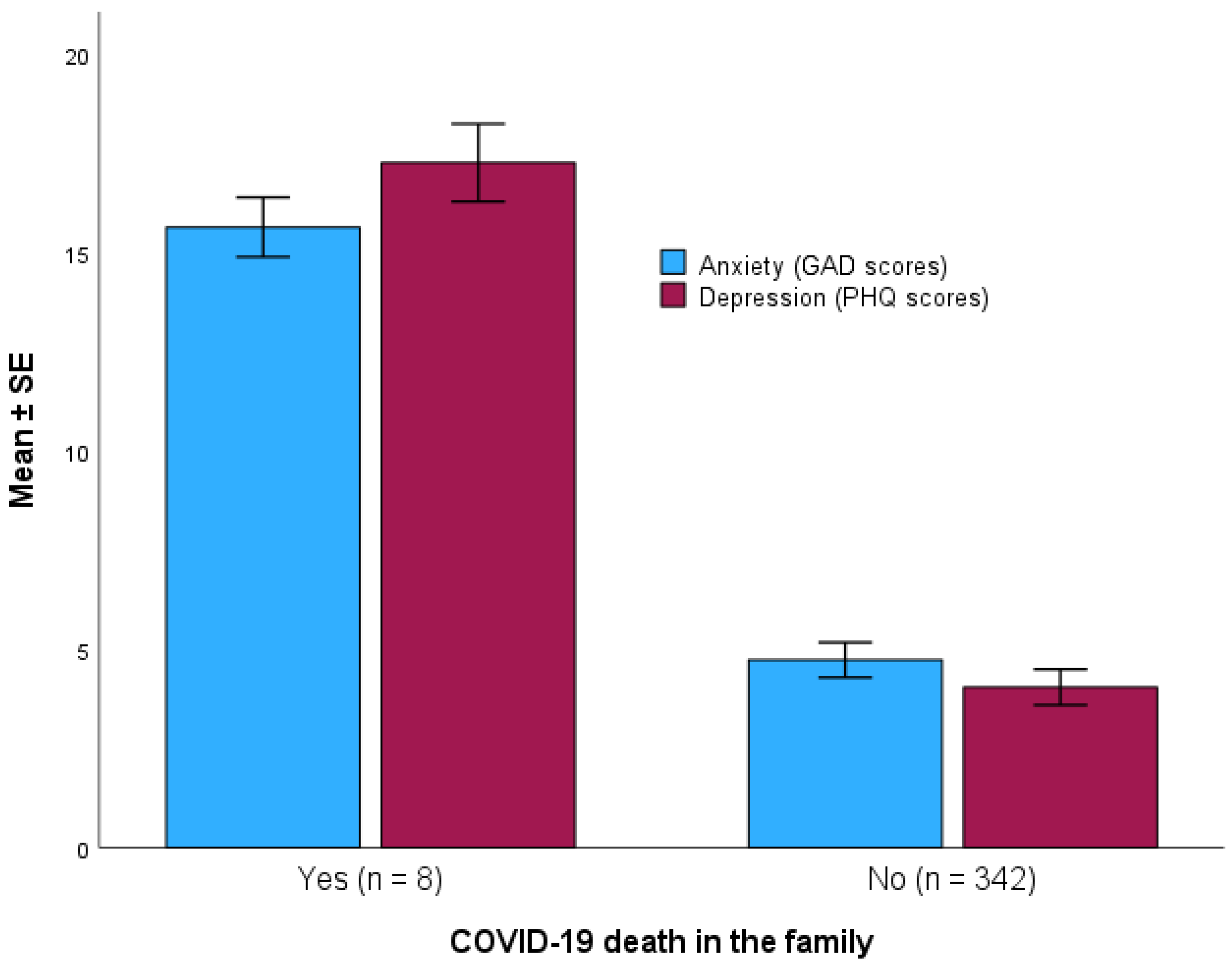

3.4. Association between COVID-19 Death in the Family with Anxiety and Depression

Mean ±

SE scores of anxiety and depression were compared between adolescents who had COVID-19 death in the family (

n = 8) and those who did not (

n = 342). For anxiety, those who had COVID-19 death in the family showed a significantly higher GAD-7 scores compared with those who did not have COVID-19 death in the family (15.63 ± 1.06

vs. 4.73 ± 4.05, respectively, Mann-Whitney U

p-value <0.001) (

Figure 4).

For depression, those who had COVID-19 death in the family showed a significantly higher PHQ-9 scores compared with those who did not have COVID-19 death in the family (17.25 ± 1.39

vs. 4.04 ± 4.17, respectively, Mann-Whitney U

p-value <0.001) (

Figure 4).

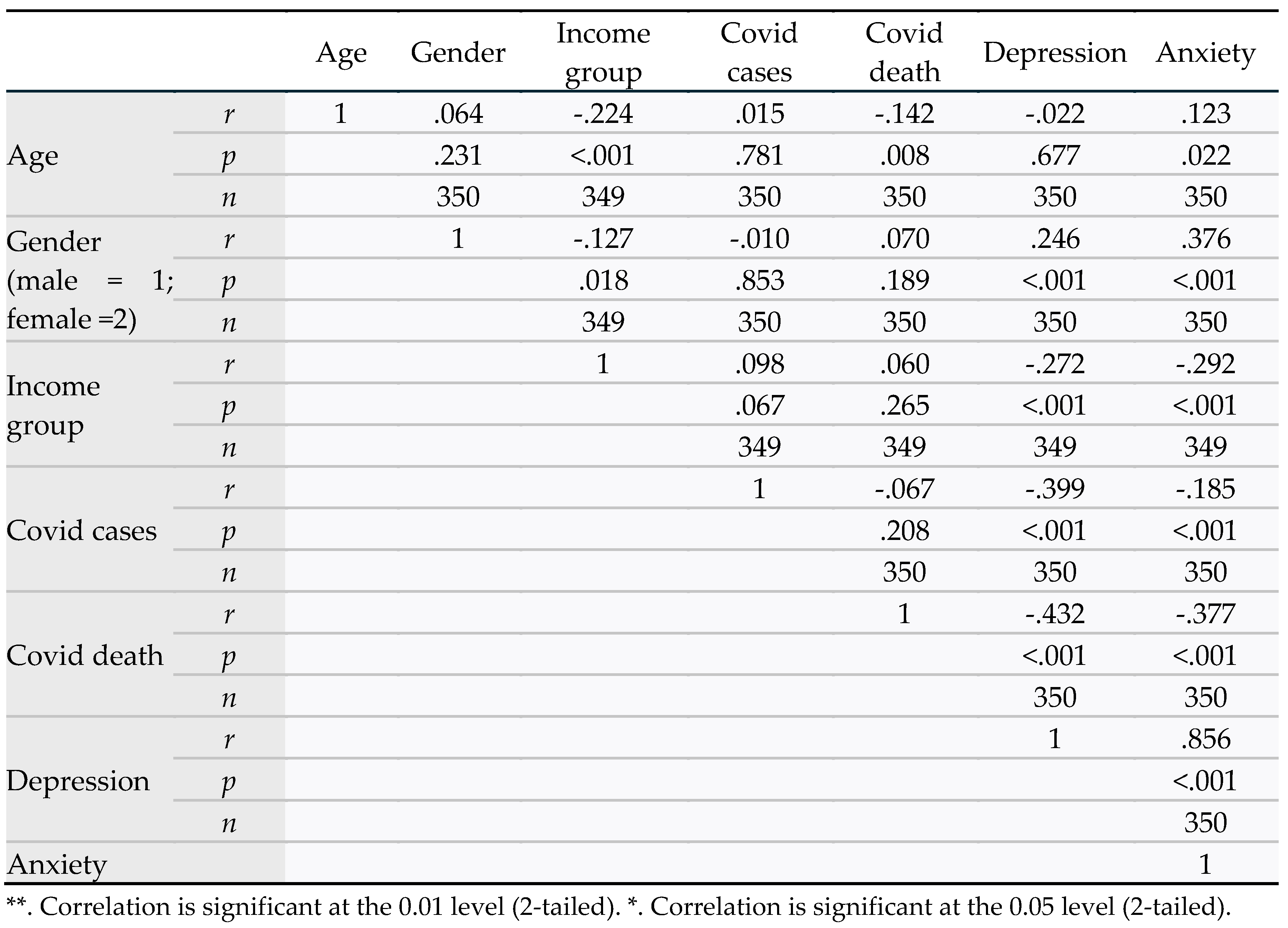

3.5. Association between Anxiety and Depression with Demographic Variables and COVID-19

Table 4 shows a bivariate correlation between age, gender, income group, COVID-19 cases in the family, COVID-19 death in the family, anxiety, and depression. The major outcome variables of this included anxiety and depression. Anxiety was significantly correlated with the following variables: age (

r = 0.123,

p = 0.022), meaning anxiety increased with increasing age; more in females than males (1 = male, 2 = female) (

r = 0.376,

p <0.001); more in lower income group (

r = -0.292,

p <0.001); having COVID-19 cases (1 = yes, 2 = no) in the family (

r = -0.185,

p <0.001); and having COVID-19 death (1 = yes, 2 = no) in the family (

r =-0.377,

p <0.001).

Depression was significantly correlated with the following variables: more in females than males (1 = male, 2 = female) (r = 0.0.246, p <0.001); more in lower income group (r = -0.272, p <0.001); having COVID-19 cases (1 = yes, 2 = no) in the family (r = -0.399, p <0.001); and having COVID-19 death (1=yes, 2 = no) in the family (r =-0.432, p <0.001).

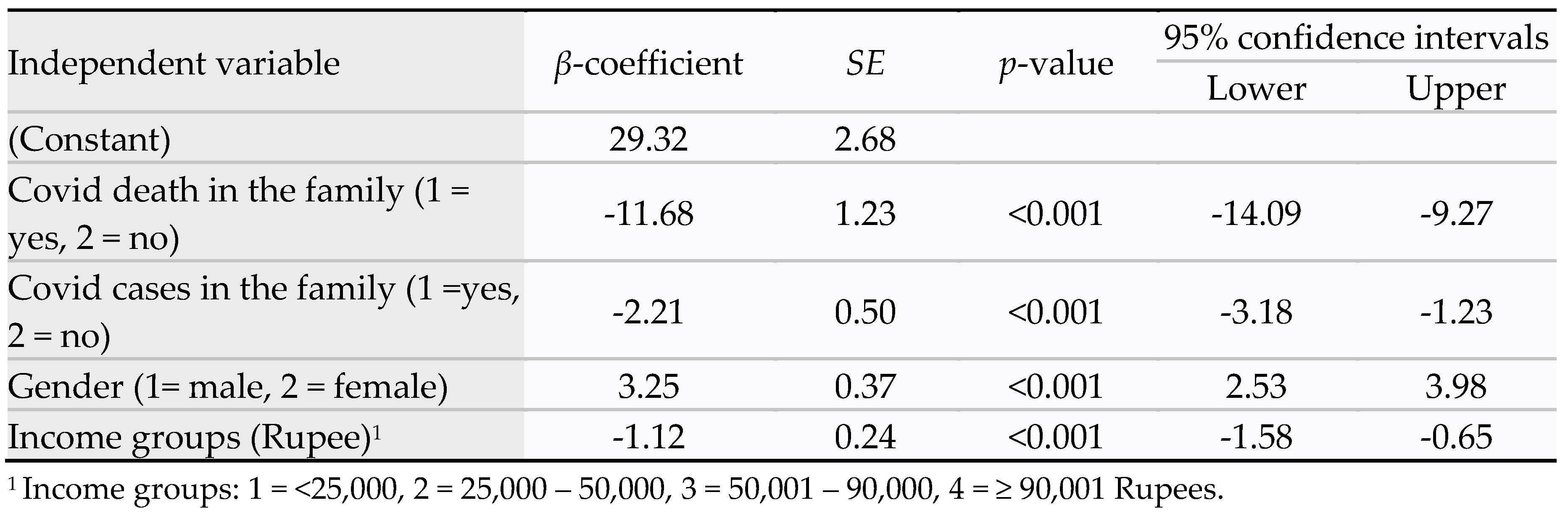

3.6. Multivariate Analysis of the Predictors of Anxiety

Multivariate linear regression analyses were conducted using the stepwise method of variable selection. A separate analysis was done using total scores of anxiety and total scores of depression as dependent variables, and demographic and COVID-19 variables as independent variables in the model.

Table 5 regression model data provides R

2 = 0.39. The statistically significant predictors of anxiety scores were as follows: COVID-19 death in the family (β-coefficient = -11.68,

p <0.001, 95% CI = -14.09 to -9.27); COVID-19 cases in the family (β-coefficient = -2.21,

p <0.001, 95% CI = -3.18 to -1.23); female gender (β-coefficient = 3.25,

p <0.001, 95% CI = 2.53 to 3.98); and lower income group (β-coefficient = -1.12,

p <0.001, 95% CI = -1.58, 4.09 to -0.65). The predicted model for anxiety was as follows:

Anxiety scores = 29.32 + 3.25 gender (1=male, 2 =female) – 1.12 income group – 2.2 covid cases (1=yes, 2=no) – 11.68 covid death (1=yes, 2=no). Age was excluded from the model (p = 0.98).

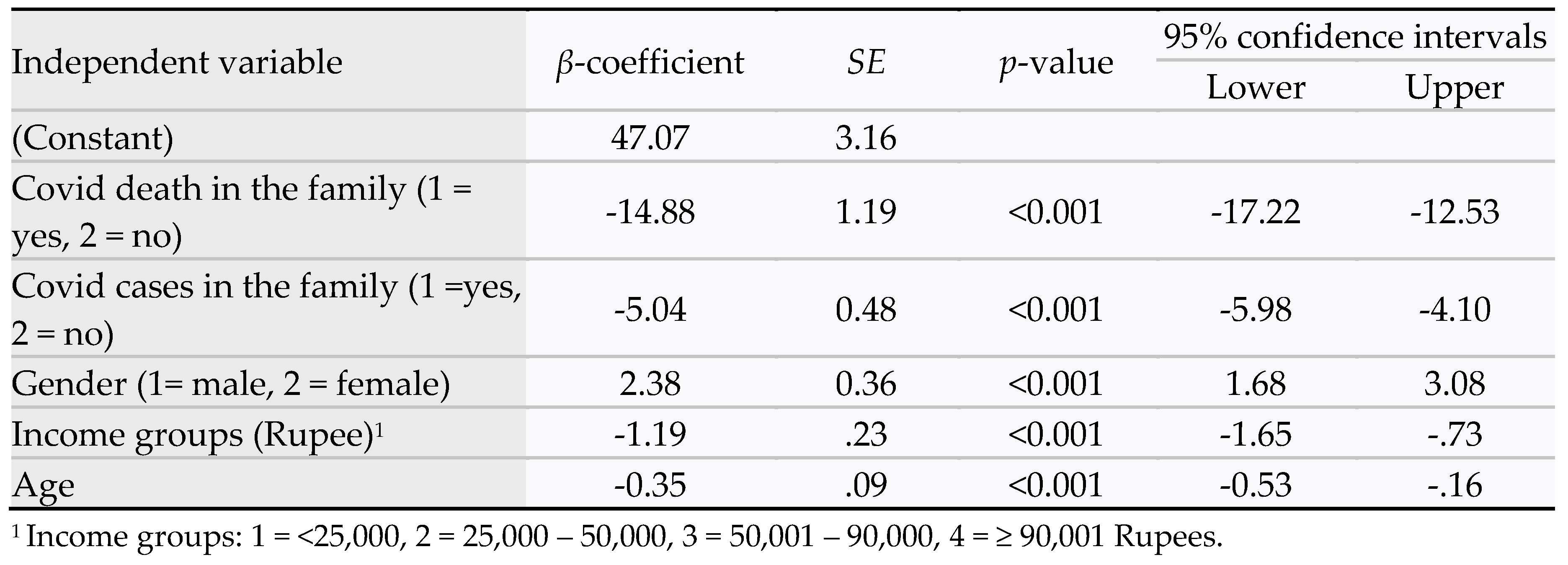

The regression analysis for depression showed R

2 = 0.50. The statistically significant predictors of depression scores were as follows: COVID-19 death in the family (β-coefficient = -14.88,

p <0.001, 95% CI = -17.22 to -12.53); COVID-19 cases in the family (β-coefficient = -5.04,

p <0.001, 95% CI = -5.98 to -4.10); female gender (β-coefficient = 2.38,

p <0.001, 95% CI = 1.68 to 3.08); and lower income group (β-coefficient = -1.19,

p <0.001, 95% CI = -1.65 to -0.73) (

Table 6). The predicted model for depression was as follows:

Depression scores = 47.07 + 2.38 gender (1=male, 2 =female) – 0.35 age – 1.19 income group – 5.04 covid cases (1=yes, 2=no) – 14.88 covid death (1=yes, 2=no) – 0.35 age.

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression in Adolescents

In this study, the prevalence of major mental health conditions, anxiety, and depression, was 35.7% and 30.0%, respectively. Among the categories of severity for anxiety, 13.4% had mild, 18.9% had moderate, and 3.4% had severe symptoms. For depression, 15.1% had mild, 12.6% had moderate, and 2.3% had severe symptoms. Overall, females had significantly higher scores for both anxiety and depression compared to their male counterparts (p <0.001).

Our study showed a relatively higher prevalence of anxiety (36% vs 20%) and depression (30% vs. 16%) when compared with another study conducted in Kashmir valley of India [

23]. Another meta-analysis reviewed data from 18 studies on COVID-related lockdown and stay-at-home measures on mental health of children and adolescents. In the later study, the prevalence of anxiety and depression in the South-East Asia Region were 22% and 23%, respectively [

24]. A Korean study [

25] among school-going adolescents during the pandemic reported the overall prevalence of depression to be 19.8% which was slightly less when compared to our study. The prevalence of severe depression in the study from Korea was also lower (1.2% vs 2.3%) when compared to the current study. Another meta-analysis [

26] included 89 studies comprising of 1,441,828 subjects of varying age groups and geographic regions (in developing and developed countries). The pooled prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms during the pandemic was 32% and 33%, respectively, which were comparable to the current study. Another Chinese study showed concurrence of anxiety and depressions prevalences with our study results among adolescents [

27].

The observed differences among many studies could be due to variations in study populations, geographic locations, and study designs. However, we used robust methods to analyze adolescents with and without COVID-19 cases and COVID-19 deaths in their families. In both univariate and multivariate analyses, our data convincingly quantified significantly higher scores of anxiety and depression (p <0.001) among adolescents having COVID-19 cases or COVID-19 deaths in the family. Our community-based approach in rural West Bengal and the study methodologies were novel.

4.2. Gender Differences

We observed a significantly higher prevalence of both anxiety and depression among females in this study. Consistent with our findings, a study among Chinese students aged 12-18 years during the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevalences for anxiety and depression were significantly higher in females than males (38.4% vs. 36.2%,

p = 0.038, respectively for anxiety; and 45.5% vs. 41.7%,

p = 0.001, respectively for depression) [

27]. In the multivariate logistic regression model, females had a higher risk for anxiety (OR

anxiety = 1.64, 95% CI, 1.39 to 1.93) and depression (OR

depression = 1.15, 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.26). In another study conducted in 15 countries in Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and the Pacific under the World Health Organization World Mental (WMH) Survey Initiative, women had significantly higher lifetime risk for anxiety-mood disorders and major depressive disorder than men [

28]. In another prospective study in the U.S. [

29], 113 middle school students, aged 11-to-14 years were assessed for three dimensions of anxiety (worry and oversensitivity, social concerns and concentration, and physiological anxiety) and depressive symptoms at an initial assessment and 1 year later. The U.S. study showed that anxiety symptoms (worry and oversensitivity in particular) predicted later depression symptoms more strongly for girls than for boys [

29]. In our study, anxiety and depression often co-existed in adolescents. Further studies are needed to explore whether anxiety leads to depression, as observed in the U.S. study mentioned earlier.

4.3. Determinants of Anxiety and Depression

In the current study, GAD scores for anxiety and PHQ scores for depression were significantly higher (

p <0.001) among adolescents who had a family member with COVID-19 infection or a death due to COVID-19 in the family – these findings were reiterated by the findings of Panda et al (2020) from India [

30]. Another meta-analysis by Lee et al (2021) in Korea [

25] found significantly higher prevalence of anxiety and depression in students who had a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis compared to those who did not. Among other risk factors, one study reported a poor parent-child relationship associated with high anxiety and depression levels in adolescents during the pandemic [

31]. However, our study being conducted primarily in a traditional rural Indian community, the occurrences of parent-child conflict are less common in the society. Lack of physical activities, online mode of education, and lack of interpersonal interactions were found as associated risk factors in several study [

25,

32,

33]; however, these data were not collected in our study.

While our study identified several important determinants of anxiety and depression in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to note some limitations of our research.

4.4. Limitations and Strengths

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results: 1) Cross-sectional design: Due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, we cannot establish a causal relationship between COVID-19 and mental health problems in adolescents. 2) Single time point data collection: As data were collected at a single point in time, our study does not account for changes in mental health over the course of the pandemic or how its impact may have evolved. 3) Limited factors analyzed: We lack data on several potentially influential factors, such as access to recreational facilities, levels of physical activity, and parental education, which might affect adolescent mental health.

Despite these limitations, our study has notable strengths: 1) Community-based approach: In contrast to many previous institute-based studies, our research involved a rural community in West Bengal, providing insights into a less-studied population. 2) Random selection: Households were selected using a random selection procedure, enhancing the representativeness of our sample and reducing potential selection bias. 3) Direct data collection: Data were collected and monitored through house-to-house visits and in-person interviews, ensuring accuracy and potentially reducing the impact of confounding variables.

These strengths contribute to the validity and uniqueness of our findings while acknowledging the constraints inherent to the study design.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study found that the prevalence of depression and anxiety was significantly higher among adolescents from families with COVID-19 cases and COVID-19 deaths. These findings underscore the need for immediate, targeted approaches to support adolescent mental health and stress coping strategies. Families, schools, and healthcare providers have specific roles to play:

Families: Encourage open communication to facilitate healthy decision-making and provide supervision to prevent antisocial activities.

Schools: Develop and implement specific training modules to help students cope with emergencies and their aftermath. Train teachers and staff to build a safe and supportive environment.

Healthcare providers: Clinicians and nurses can provide coaching and counseling and educate students on self-care and coping skills. Community-based health workers should be trained to provide early interventions for adolescent mental health and encourage positive parenting practices.

As pandemics cause unprecedented changes involving health, social, financial, and many other dimensions, a holistic approach is crucial. This approach should involve all stakeholders, including young people, schoolteachers, parents, clinicians, social workers, policymakers, and the media, to ensure the mental well-being of adolescents during and after a pandemic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.M; Methodology, A.K.M. and S.D.; Software, A.K.M.; Validation, A.K.M., S.D.; Formal Analysis, A.K.M; Investigation, S.D., A.M., M.R.; Resources, A.K.M., S.D.; Data Curation, A.M., M.R.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, A.K.M, S.D., A.M.; Writing – Review & Editing, A.K.M., S.D.; Visualization, A.K.M.; Supervision, S.D.; Project Administration, A.K.M., S.D.

Funding

This research was funded by The Fulbright Foreign Scholarship Board and The Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs of the United States Department of State, as part of the Fulbright-Nehru Academic and Professional Excellence Award, 2022-2023, and the APC was funded by Diseases.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) of IPGME&R/SSKMH hospital (letter number IPGME&R/IEC/2023/047, dated 21 January 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed written consents and assents (above age 7) were obtained from all subjects enrolled in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data collection questionnaires are provided in the Appendix. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

GAD-7 Anxiety Scale.

Table A1.

GAD-7 Anxiety Scale.

Appendix B

Table A2.

PHQ-9 Depression Scale.

Table A2.

PHQ-9 Depression Scale.

References

- World Health Organization. Mental health of adolescents. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Zhang, Z.; Mitra, A.K.; Schroeder, J.A.; Zhang, L. The prevalence of and trend in drug use among adolescents in Mississippi and the United States: Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) 2001–2021. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfeld, M.R.; Torregrossa, M.M. Consequences of adolescent drug use. Translational Psychiatry 2023, 13, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.; Bhattad, D. Immediate and short-term prevalence of depression in COVID-19 patients and its correlation with continued symptoms experience. Indian J Psychiatry. 2022, 64, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johns Hopkins University. Coronavirus Resource Center. COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE). Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (accessed on 2 August 2024).

- Worldometer. COVID-Coronavirus Statistics. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed on 2 August 2024).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. New Surgeon General advisory raises alarm about the devastating impact of the epidemic of loneliness and isolation in the United States. 2023. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2023/05/03/new-surgeon-general-advisory-raises-alarm-about-devastating-impact-epidemic-loneliness-isolation-united-states.html (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Ornell, F.; Schuch, J.B.; Sordi, A.O.; Kessler, F.H.P. “Pandemic fear” and COVID-19: Mental health burden and strategies. Braz J Psychiatry 2020, 42, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Xue, J.; Zhao, N.; Zhu, T. The impact of COVID-19 epidemic declaration on psychological consequences: A study on active weibo users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahia, I.V.; Blazer, D.G.; Smith, G.S.; Karp, J.F.; Steffens, D.C.; Forester, B.P.; et al. COVID-19, mental health and aging: A need for new knowledge to bridge science and service. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 695–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magson, N.R.; Freeman, J.Y.A.; Rapee, R.M.; Richardson, C.E.; Oar, E.L.; Fardouly, J. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2021, 50, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavira, D.A.; Ponting, C.; Ramos, G. The impact of COVID-19 on child and adolescent mental health and treatment considerations. Behav Res Ther 2022, 157, 104169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.A.K.; Mitra, A.K.; Bhuiyan, A.R. Impact of COVID-19 on mental health in adolescents: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin, B.; Lyne, J.; McNicholas, F. Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 37, 156–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Adolescent health in the Southeast Asia Region. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/health-topics/adolescent-health (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Balarajan, Y.; Selvaraj, S.; Subramanian, S.V. Health care and equity in India. Lancet 2011, 377, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.M.; Karpaga, P.P.; Panigrahi, S.K.; Raj, U.; Pathak, V.K. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on adolescent health in India. J Family Med Prim Care 2020, 9, 5484–5489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Roy, D.; Sinha, K.; Parveen, S.; Sharma, G.; Joshi, G. Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on mental health of children and adolescents: A narrative review with recommendations. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann 2002, 32, 509–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.; Monahan, P.O.; Löwe, B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med 2007, 146, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Levis, B.; Riehm, K.E.; Saadat, N.; Levis, A.W.; Azar, M.; et al. The accuracy of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 algorithm for screening to detect major depression: An individual participant data meta-analysis. Psychother Psychosom 2020, 89, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, F.; Manea, L.; Trepel, D.; McMillan, D. Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: a systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2016, 39, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeelani, A.; Dkhar, S.A.; Quansar, R.; Khan, S.M.S. Prevalence of depression and anxiety among school-going adolescents in Indian Kashmir valley during COVID-19 pandemic. Middle East Curr Psychiatry 2022, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, L.; Carducci, B.; Klein, J.D.; Bhutta, Z.A. Indirect effects of COVID- 19 on child and adolescent mental health: an overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Global Health 2022, 7, e010713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Noh, Y.; Seo, J.Y.; Park, S.H.; Kim, M.H.; Won, S. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Adolescent Students in Daegu, Korea. J Korean Med Sci 2021, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Deng, J.; Zhou, F.; Hou, W.; Silver, Z.; Wong, C.Y.; Chang, O.; Drakos, A.; Zuo, Q.K.; Huang, E. The prevalence of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms and sleep disturbance in higher education students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 301, 113863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.J.; Zhang, L.G.; Wang, L.L.; Guo, Z.C.; Wang, J.Q.; Chen, J.C.; et al. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2020, 29, 749–758. [Google Scholar]

- Seedat, S.; Scott, K.M.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Berglund, P.; Bromet, E.J.; Brugha, T.S.; et al. Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009, 66, 785–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaplin, T.M.; Gillham, J.E.; Seligman, M.E. Gender, anxiety, and depressive symptoms: A longitudinal study of early adolescents. J Early Adolesc. 2009, 29, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Panda, P.K.; Gupta, J.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Kumar, R.; Meena, A.K.; Madaan, P.; et al. Psychological and behavioral impact of lockdown and quarantine measures for COVID- 19 pandemic on children, adolescents and caregivers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Trop Pediatr 2021, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Lin, H.; Richards, M.; Yang, S.; Liang, H.; et al. Study problems and depressive symptoms in adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak: Poor parent-child relationship as a vulnerability. Global Health 2021, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Qi, H.; Liu, R.; Feng, Y.; Li, W.; Xiang, M.; et al. Depression, anxiety and associated factors among Chinese adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak: A comparison of two cross-sectional studies. Translational Psychiatry, 2021, 11, 148–156. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhai, A.; Yang, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, H.; Yang, C.; et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms of high school students in Shandong Province during the COVID-19 epidemic. Front Psychiatry 2020, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).