Introduction

People with severe and persistent mental illness (SPMI) are relatively low in number but consume a high proportion of mental healthcare resources due to the complexity and longer-term nature of their mental health problems. The term ‘SPMI’ was introduced by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in 1987 to replace “chronic mental illness” (CMI), in part to address the negative associations and therapeutic pessimism associated with the word ‘chronic’ [

1]. The NIMH definition of SPMI comprises three dimensions: diagnosis, disability, and duration. People with SPMI usually have a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar affective disorder, or personality disorder, with functional limitations in managing usual life activities, and the condition is likely to be persistent through the adult lifespan. The majority are unemployed or require supportive work environments, most are in receipt of welfare benefits and require assistance to manage everyday activities and many struggle with interpersonal skills and relationships as a result of their illness [

1].

The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recently published clinical guidance on the mental health rehabilitation services and interventions that should be available to adults with SPMI (NICE, 2020). This guidance recommends that local rehabilitation services should comprise both inpatient rehabilitation units and community-based supported accommodation services that receive specialist clinical input from multidisciplinary community rehabilitation teams. These services should be embedded within the wider local mental health system and organized into a defined rehabilitation care pathway that supports people to progress in their recovery, with the aim of stabilizing symptoms and enabling people to gain the confidence and skills to live successfully in the community and achieve optimum autonomy. All rehabilitation services should adopt a recovery-oriented approach that is, by definition, collaborative and individualized [

2]. (

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng181. (Date accessed September 21, 2023).

There is mounting evidence from the UK that mental health rehabilitation services are clinically effective. About two-thirds of people supported by rehabilitation services progress to successful community living within 18 months of admission to an NHS (National Health Services) inpatient rehabilitation unit; two-thirds sustain this over five years without requiring further hospital admissions, and around 10% achieve independent living within this period. Patients receiving support from rehabilitation services are eight times more likely to achieve/sustain community living, compared to those supported by generic community mental health services [

3,

4]. Without specialist mental health rehabilitation, people with severe and complex mental health problems are at very high risk of self-neglect, exploitation from others and long-term institutionalization [

4].

A recent systematic review (Dalton-Locke et al 2021) of the evidence for the effectiveness of inpatient and community-based mental health rehabilitation services included 65 studies conducted across 14 countries. Inpatient rehabilitation was found to be associated with a reduction in subsequent acute inpatient service use. However, once in the community, only around a half of people with SPMI graduated from higher to lower levels of supported accommodation within the expected timeframes [

5]. One of the included studies by Bunyan et al (2016) also showed reductions in inpatient service costs associated with inpatient rehabilitation due to the reduced inpatient service use following the rehabilitation admission [

6]. A further study investigated the effectiveness of a specialist inpatient facility (the National Psychosis Unit) that provides evidence-based, personalized, multidisciplinary interventions for patients with complex psychosis in London, UK. This two year ‘mirror image’ study reported the service to be associated with reduced inpatient service use [

7].

Dalton-Locke’s systematic review (2021) has also identified eight studies that evaluated community rehabilitation teams. These included teams delivering manualized models of psychosocial support (such as the Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) program, which primarily involves psychoeducation and personal recovery promotion delivered through group sessions over several months) and teams providing case management and other, less defined approaches. The findings were mixed, likely due in part to the heterogeneity of the interventions delivered and differences in the target client group and context within which the studies were conducted (for example, whether the service was part of a wider mental health system) [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

The clinical effectiveness of rehabilitation services has not been studied in Canada. This study aimed to address this through an evaluation of one community rehabilitation service based in Dartmouth, a city within Nova Scotia, Canada, known as 'Dartmouth Connections'. The primary hypothesis was that care from the team would be associated with a reduction in inpatient service utilization, as evidenced by decreases in admissions and length of stay, as well as a reduction in emergency services presentations.

Method

Study Design

Before and after study of inpatient service use and emergency room presentations in the year prior to being taken on by the community rehabilitation team and the year after.

Setting

Dartmouth Connections is a community mental health rehabilitation team that works with an average caseload of 200 clients with SPMI. It is part of the Recovery and Integration service portfolio of the Nova Scotia Health “Mental Health and Addictions Program” which provides community-based rehabilitation services for a total population of 420,000. It is one of three recovery-oriented local services that support adults with SPMI. The team receives referrals from forensic services, acute inpatient services, other community mental health teams, early psychosis services, primary care, and child and adolescent services.

The service is staffed by a multidisciplinary team of psychiatrists, social workers, occupational therapists, and registered nurses with individual case manager caseloads between 12 and 20. Recreation therapists, an occupational therapy assistant, a developmental worker and a secretary support them.

Members of the team provide services on-site and outreach to community settings. Many clients experience a high degree of complexity in addition to mental illness, including trauma history, behavioural disorders, substance misuse, cognitive impairment, and significant psychosocial challenges such as homelessness and poverty. The team works with each client towards personalized and self-identified psychosocial goals. These vary widely and comprise addressing direct mental health issues through symptom reduction as well as working on environmental aspects that impact psychological well-being. The latter includes, but is not limited to improving clients’ housing situation, employment or education opportunities to improve skills and prospects, reducing social isolation and building relationships within a community that provides friendship, empathy, support, and hope. The aim is for the client to be an active partner in their own recovery plan while being supported by the team, with the goal of living a meaningful life in their community.

The service offers facilitated group programs to build skills (e.g. cooking/baking, running, yoga, mindfulness, social skills). Clients can also join community-based work skills programs (e.g. carpentry, rubbish collection from hospitals, cleaning, etc.) and the team also works closely with local voluntary sector organizations that provide additional support and employment opportunities.

Sample

The study included all 137 individuals accepted into the service by the team over 12 months spanning September 2016 to September 2017, who received a minimum of one year of community rehabilitation from the team.

Data

Data on acute and rehabilitation inpatient mental health admissions one year before being taken on by the team and one year after this point were retrieved from the Discharge Abstract Database (i.e. during the period between September 2015 and September 2018). Emergency room (ER) visit data, specific to instances where a mental health presenting problem was identified or where the ER visit resulted in a mental health diagnosis upon ER discharge, was obtained from the Emergency Department Information System (EDIS) for the same period.

Service utilization costs were estimated during the pre- and post-rehabilitation years using the Canadian billing system of the Medical Service Insurance (MSI) in Nova Scotia, Canada: $1450 per patient day for inpatient acute mental health care and $359 for an ER visit or outpatient community rehabilitation visit.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including mean, median, standard deviations, and 95% confidence intervals, were calculated. Due to the non-normal distribution of the data, comparisons of inpatient service use and emergency room presentations in the year before being taken on by the rehabilitation service and the year after were conducted using Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks tests. Statistical analyses were conducted at a 95% confidence interval (α = 0.05) using SAS JMP version 15.0.

The study has been approved by the Nova Scotia Health Research Ethics Board File Number #: 1029840.

Results

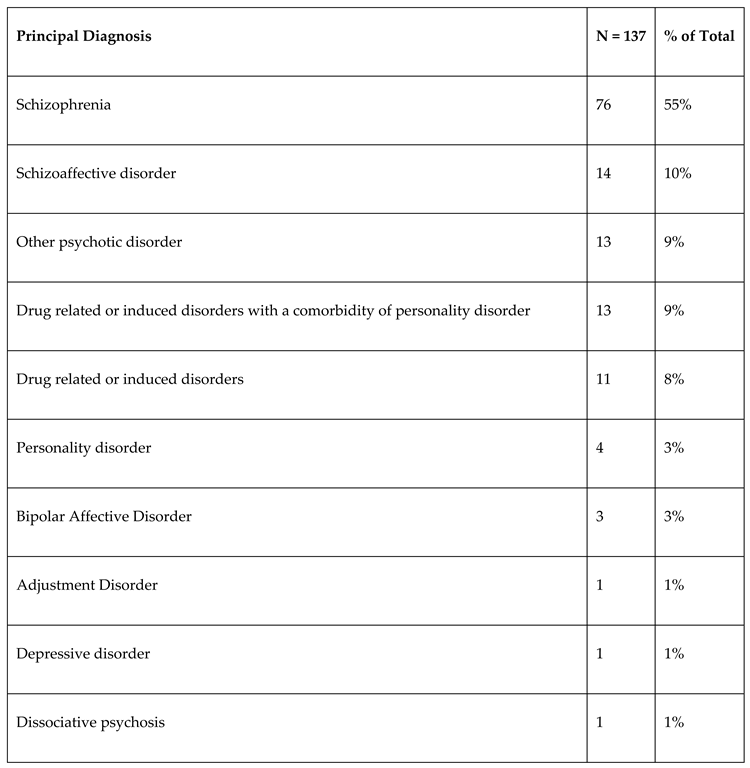

Most of the team’s clients were male with a mean age of 44 years. The primary diagnosis was schizophrenia (see

Table 1).

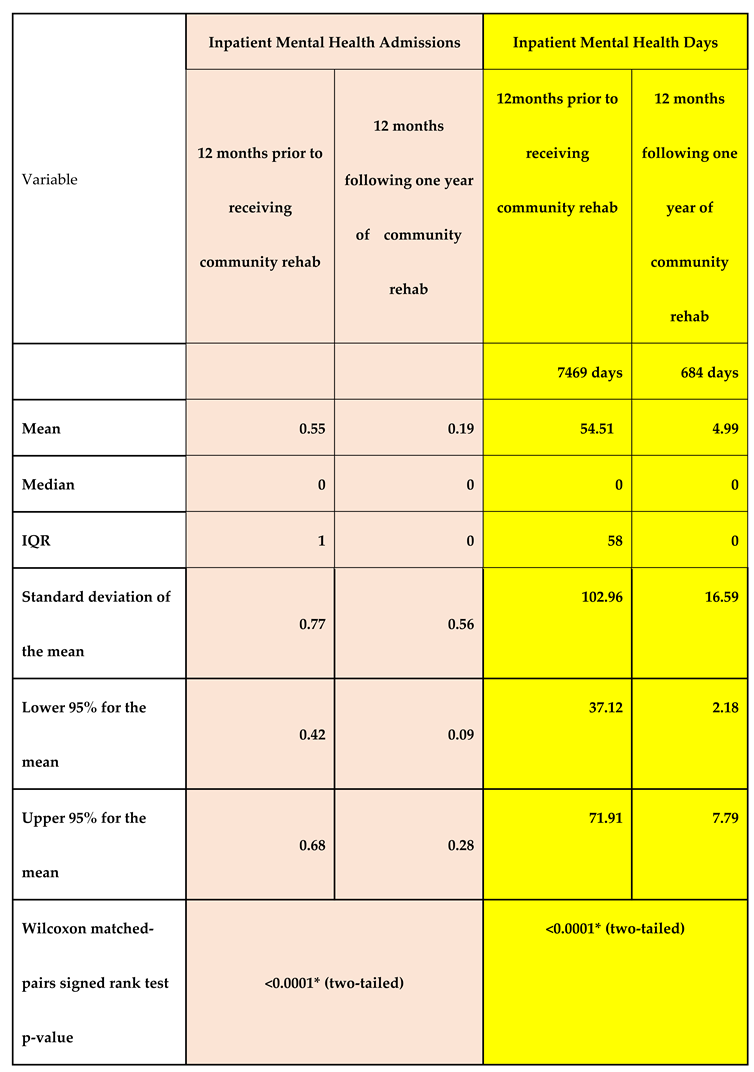

As illustrated in

Table 2 there was a statistically significant reduction in the mean admission rate and mean LOS in the post-rehabilitation year compared to pre-rehabilitation. In addition, there were no inpatient admissions in 88% of patients in the post-rehabilitation year compared to 69% in the pre-rehabilitation year. Similarly, 82% of patients in the post-rehabilitation year had no visits to the ER for mental health, compared to 67% in the pre-rehabilitation period.

When comparing the mean of Mental Health -related Emergency Department visits, in the year before (0.89) and after (0.34) being taken on by the community rehabilitation team, the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test p-value indicates a significant reduction (p=0.005).

Costs

The reduction in post-rehabilitation hospital stays, reflecting a decrease of 6,785 patient days at a daily cost savings of $1,450.00, results in a cumulative estimated savings of -$9,838,250.00. Additionally, the evaluation of MHA-related ED visits, employing an average cost per visit of $359.00 and considering a reduction of 76 visits, demonstrates a net cost saving of -$27,284.00.

In the context of community rehabilitation, the cohort comprising 137 clients underwent a total of 1,050 visits to a community rehabilitation clinic over a year. With an established average cost of $359.00 per outpatient visit, the comprehensive estimated expenditure for all visits amounts to $376,950.

The culmination of these analyses, when factoring in costs associated with community rehabilitation treatment, inpatient hospitalizations, and ED visits reduction, reveals a net savings of $9,488,584. This examination underscores the fiscal advantages arising from the implementation of community psychosocial rehabilitation intervention within the healthcare paradigm.

Discussion

The present study makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the importance of community rehabilitation services for individuals with severe persistent mental illness (SPMI) in Canada. The study evaluated the impact of a community rehabilitation team on inpatient service use and emergency department (ED) visits among individuals with SPMI over a one-year period before and one year after 12 months of engagement with the rehabilitation team. The findings not only revealed substantial reductions in both inpatient service use and ED visits but also significant associated cost savings. A notable percentage of patients experienced no inpatient admissions or ED visits following a year of rehabilitation. These findings underscore the potential economic and clinical benefits of community rehabilitation for this patient group.

Dalton-Locke et al., in their systematic review evaluating the effectiveness of mental health rehabilitation services, found consistent evidence for the effectiveness of inpatient rehabilitation services, particularly in terms of subsequent reductions in inpatient service utilization, but the impact of community rehabilitation services was less clear [

5]. This study provides evidence that community rehabilitation teams are clinically effective and the strengths of the study provide greater confidence in these results, including the relatively large sample size, the focus on people with SPMI and the use of robust (‘hard’) outcome measures, including admission rates, duration of hospital stays, and visits to Emergency Departments.

However, we also acknowledge the study's limitations, including the absence of a control group. Nevertheless, the service-use reductions are unlikely to be explained entirely by regression to the mean. In addition to analysis of similar services across Canada, future studies could examine outcome measures between various local mental health services, particularly services specializing in the treatment of primary psychotic illnesses (e.g., early psychosis programs), to better delineate the effectiveness of rehabilitation services in this population.

This study aligns with the resurgence of interest in mental health rehabilitation, as emphasized in recent NICE guidelines [

2] highlighting the importance of these services for people with complex psychosis. The findings contribute to the evolving understanding of the need for this subspecialty for individuals with SPMI.

In light of economic austerity and the demand for service efficiency, the cost-effectiveness of rehabilitation interventions is crucial. Whilst this study could not provide a full assessment of the service's cost-effectiveness, the reductions in service use and associated costs observed are encouraging. Although the community rehabilitation service cost was not included in our analyses, sustained benefits over the years in terms of reductions in service use could potentially offset these treatment costs.

Despite the scarcity of research on community rehabilitation in Canada, this study provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of such services. The authors hope that this research will inspire further investigations into the clinical and cost-effectiveness of community mental health rehabilitation teams.

Conclusions

This study adds to the growing body of literature supporting the effectiveness of psychosocial rehabilitation services for individuals with SPMI in Canada. The positive outcomes, including significant reductions in inpatient service use and associated cost savings, underscore the importance of further research and the potential economic benefits of investing in community psychosocial rehabilitation.

Authors Contributions

The first draft of the manuscript was written by Dr. Mahmoud A. Awara, who, along with the second author, contributed to the study conception and design, material preparation, data collection and analysis.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study has been approved by the Nova Scotia Health Research Ethics Board, waived obtaining of Consent by the Privacy Officer- File Number #: 102984.

Acknowledgements

We extend our sincerest gratitude to Professor Helen Killaspy and Dr. Christian Dalton-Locke of University College London, UK, for their invaluable and professional contributions in reviewing our scholarly article on community psychosocial rehabilitation. Their expertise and insightful feedback have significantly enriched the quality and rigor of our work. We sincerely appreciate their time, dedication, and commitment to advancing knowledge in the field. Their input has undoubtedly strengthened the impact and relevance of our research. Thank you, Professor Killaspy and Dr. Dalton-Locke, for your invaluable support and collaboration. We thank the inpatient rehab multidisciplinary team and the data analysts for their dedication, endeavors, and hard work that enabled recovery for this group of patients. We also thank data analysts Bryanne Tayler and Patryk Simon for their significant contributions in collecting and analyzing data for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- National Institute of Mental Health. (1987). Towards a model for a comprehensive community-based mental health system. Washington, DC: Author.

- NICE. (2023). NICE guideline 181: Rehabilitation for adults with complex psychosis and related severe mental health conditions. Retrieved September 21, 2023, from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng181.

- Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health. (2016). Guidance for commissioners of rehabilitation services for people with complex mental health needs. London, England: Author.

- Killaspy, H., Marston, L., Green, N., et al. (2016). Clinical outcomes and costs for people with complex psychosis; a naturalistic prospective cohort study of mental health rehabilitation service users in England. BMC Psychiatry, 16, Article 95. [CrossRef]

- Dalton-Locke, C., Marston, L., McPherson, P., & Killaspy, H. (2021). The effectiveness of mental health rehabilitation services: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, Article 607933. [CrossRef]

- Bunyan, M., Ganeshalingam, Y., Morgan, E., et al. (2016). In-patient rehabilitation: Clinical outcomes and cost implications. BJPsych Bulletin, 40(1), 24-28. [CrossRef]

- Casetta, C., Gaughran, F., Oloyede, E., et al. (2020). Real-world effectiveness of admissions to a tertiary treatment-resistant psychosis service: 2-year mirror-image study. BJPsych Open, 6(5), Article e82. [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, W. (2000). Integrating cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for persons with schizophrenia into a psychiatric rehabilitation program: Results of a three-year trial. Community Mental Health Journal, 36(5), 491-500. [CrossRef]

- Chan, K. P. K., Kathryn, K., Igoumenou, A., & Killaspy, H. (2020). Predictors of successful move-on to more independent accommodation amongst users of the community mental health rehabilitation team: A prospective cohort study in inner London. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55, 407-416. [CrossRef]

- Färdig, R., Lewander, T., Melin, L., et al. (2011). A randomized controlled trial of the illness management and recovery program for persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services, 62(6), 606-612. [CrossRef]

- Incedere, A., & Yildiz, M. (2019). Case management for individuals with severe mental illness: Outcomes of a 24-month practice. Turkish Journal of Psychiatry, 30, 245-252. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, S. B., Dalum, H. S., Korsbek, L., et al. (2019). Illness management and recovery: One-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial in Danish community mental health centers. BMC Psychiatry, 19, Article 65. [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, P., Yip, B. H., Björk, C., et al. (2009). Common genetic determinants of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Swedish families: A population-based study. Lancet, 373(9659), 234-239. [CrossRef]

- Tan, C. H. S., Ishak, R. B., Lim, T. X. G., et al. (2017). Illness management and recovery program for mental health problems: Reducing symptoms and increasing social functioning. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(21-22), 3471-3485. [CrossRef]

- Dalum, H. S., Waldemar, A. K., Korsbek, L., et al. (2018). Illness management and recovery: Clinical outcomes of a randomized clinical trial in community mental health centers. PLoS ONE, 13(3), Article e0194027. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Principal Diagnoses Among the Study Population.

Table 1.

Principal Diagnoses Among the Study Population.

Table 2.

Comparative Analysis of Inpatient Service Utilization Before and After Intervention by a Community Rehabilitation Team.

Table 2.

Comparative Analysis of Inpatient Service Utilization Before and After Intervention by a Community Rehabilitation Team.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).