Submitted:

29 August 2024

Posted:

30 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Selection of the experimental stimuli

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Questionnaire Measuring Demographics and Trauma Exposure

2.3.2. PTSD Symptom Screening

2.3.3. Affective Ratings

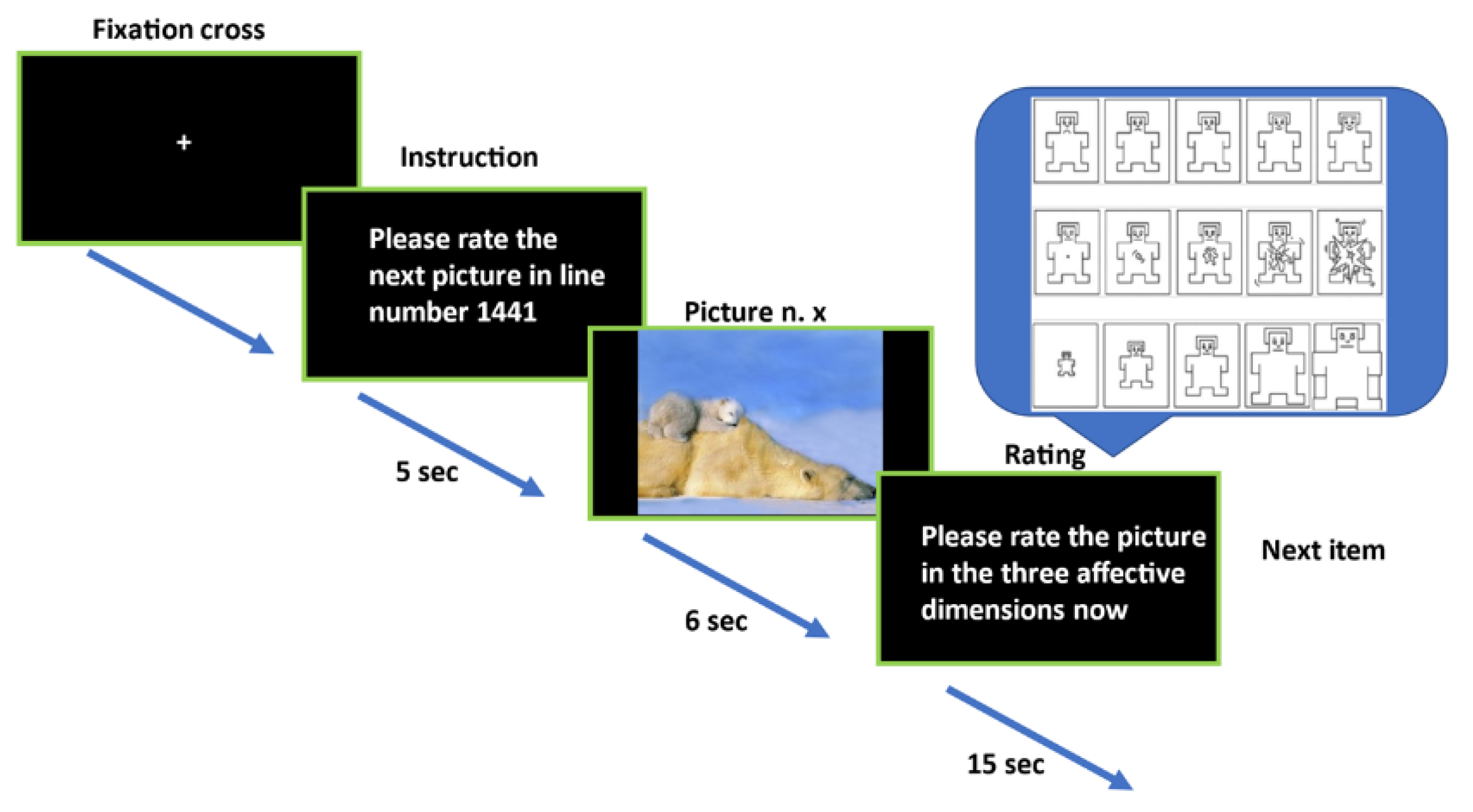

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

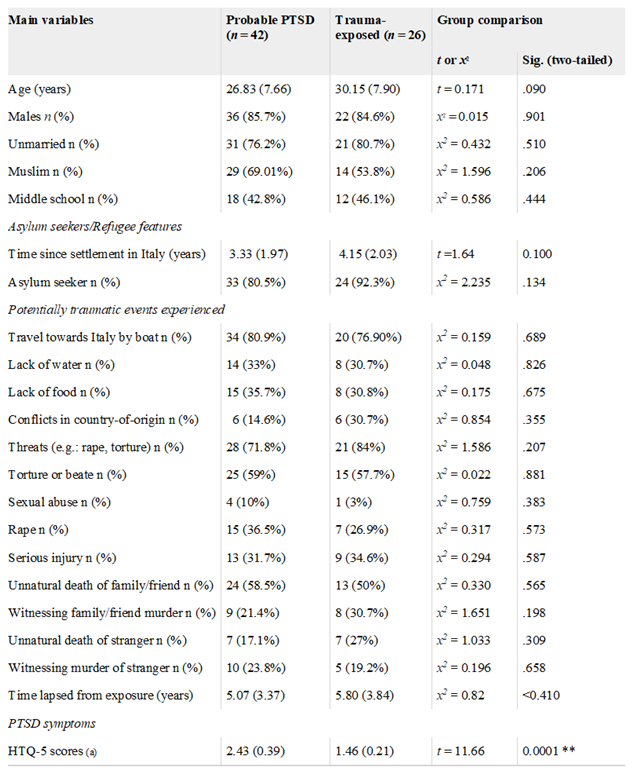

3.1. Sample Characteristics

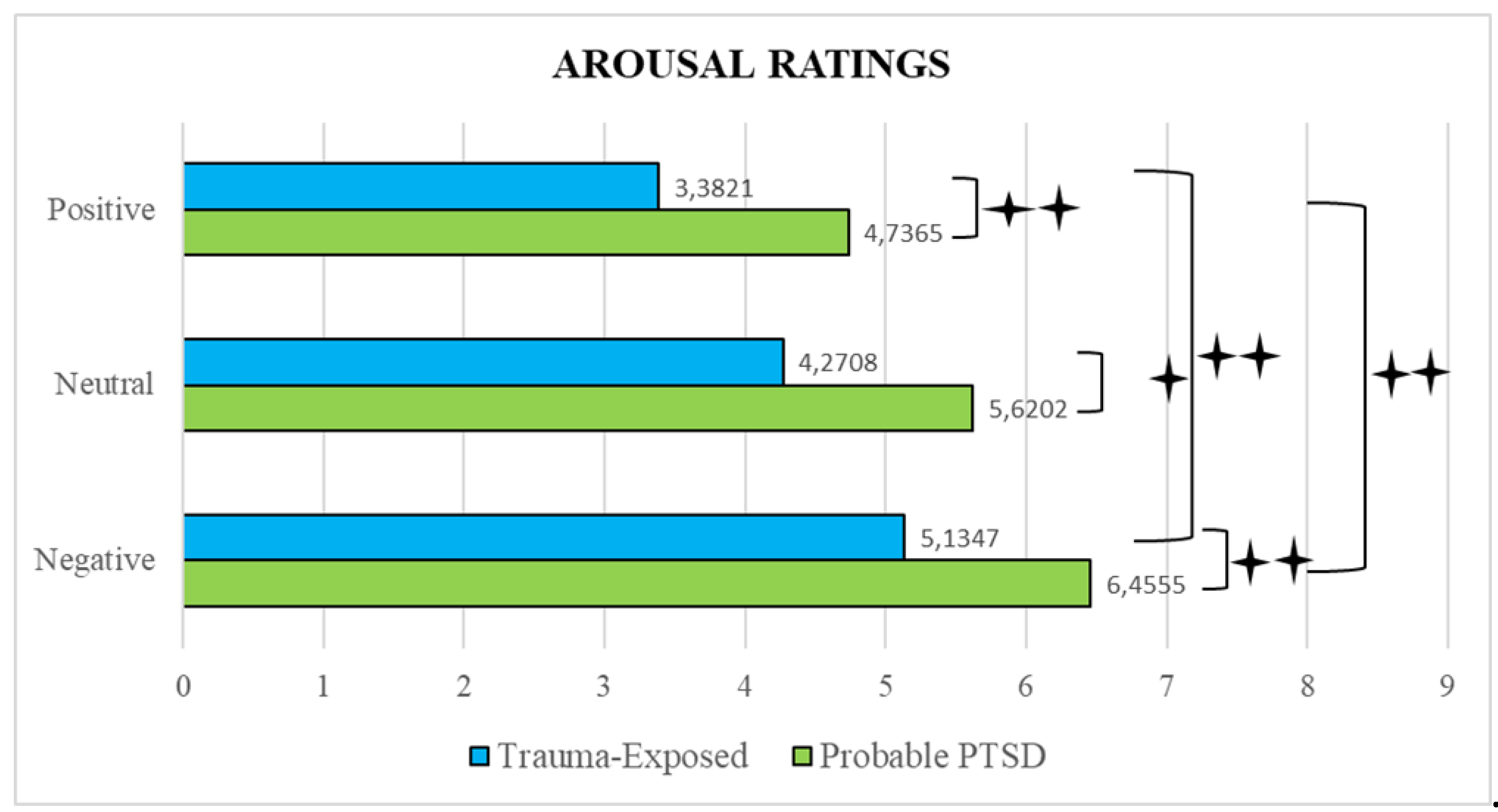

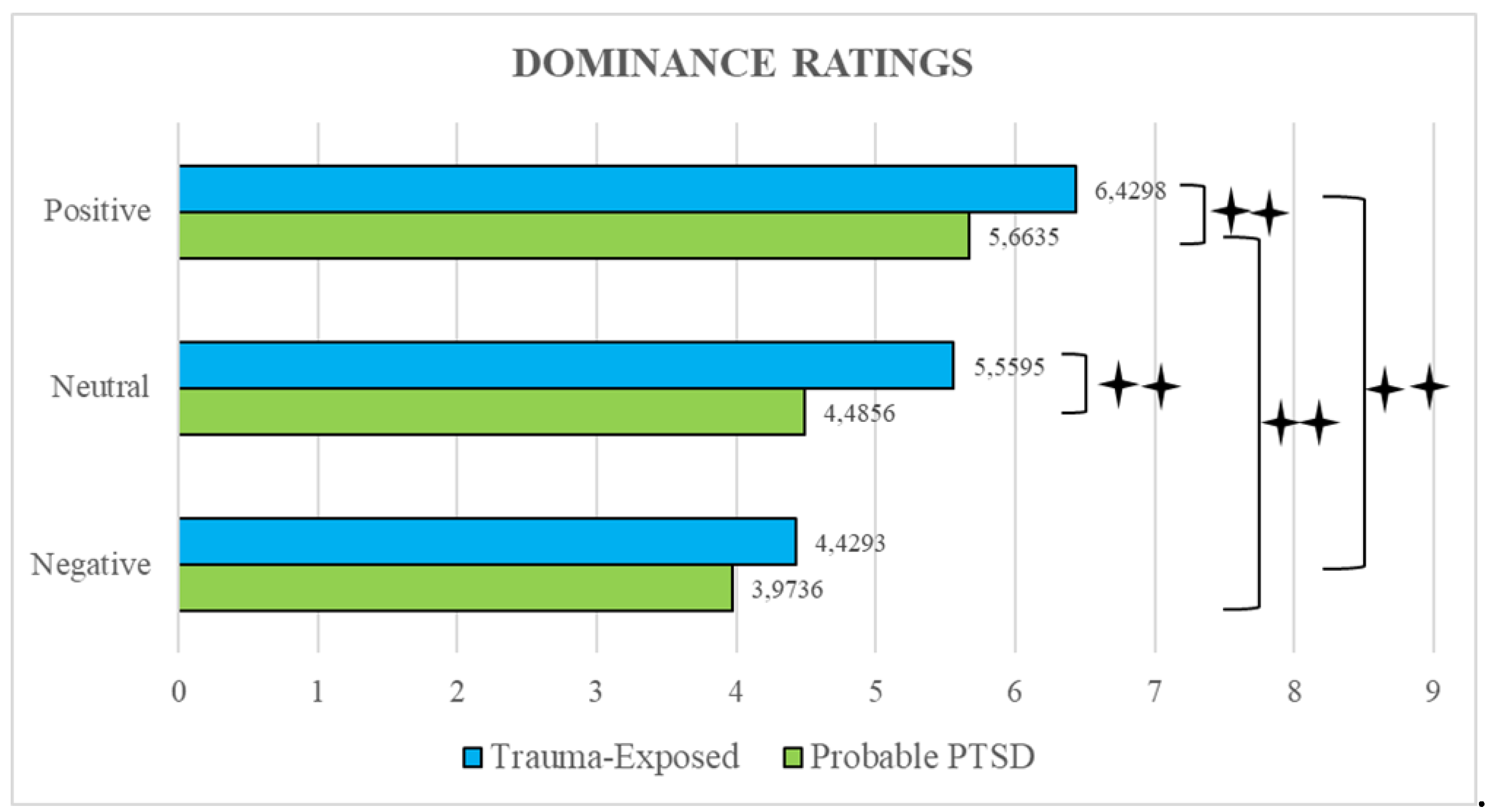

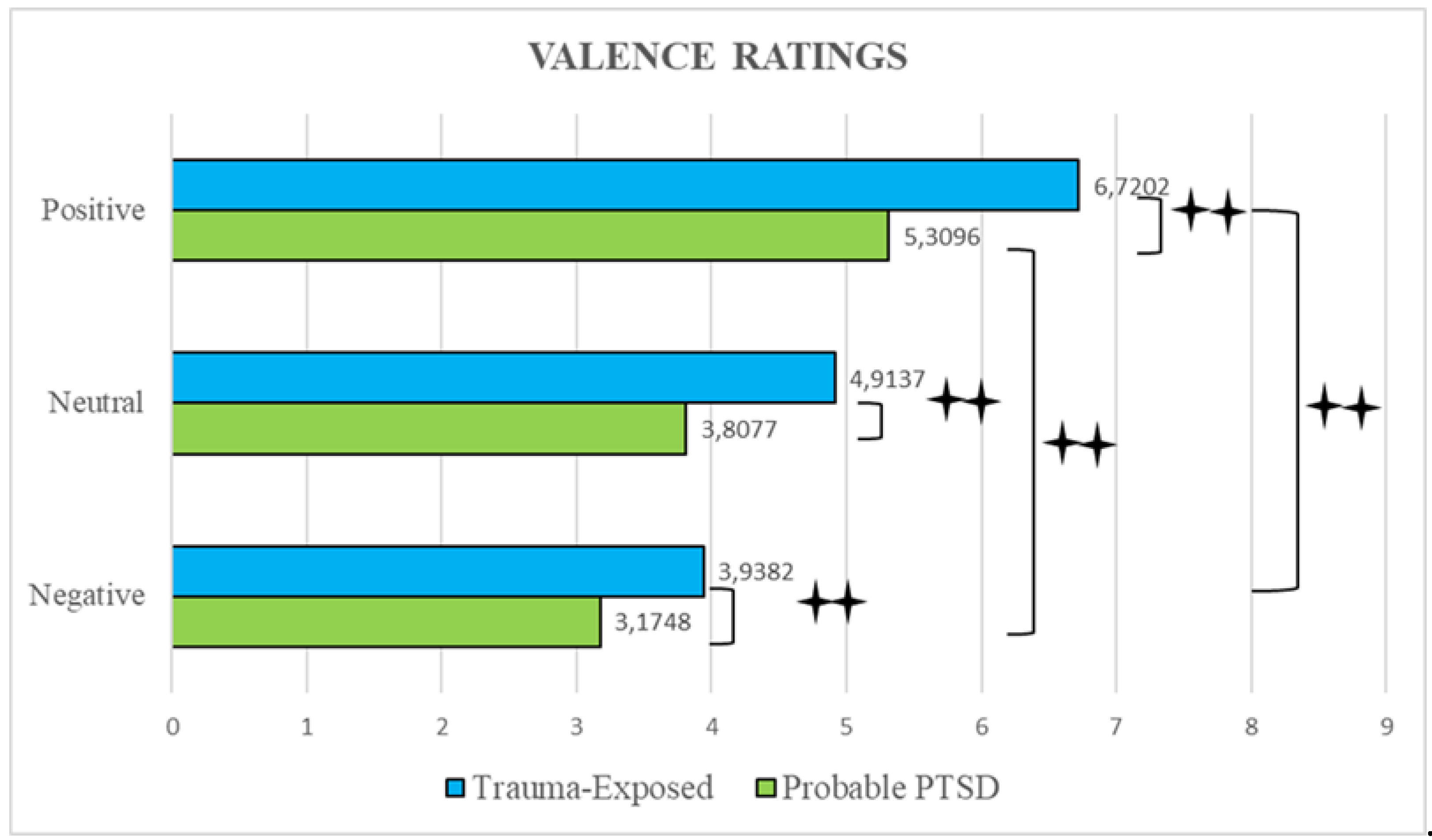

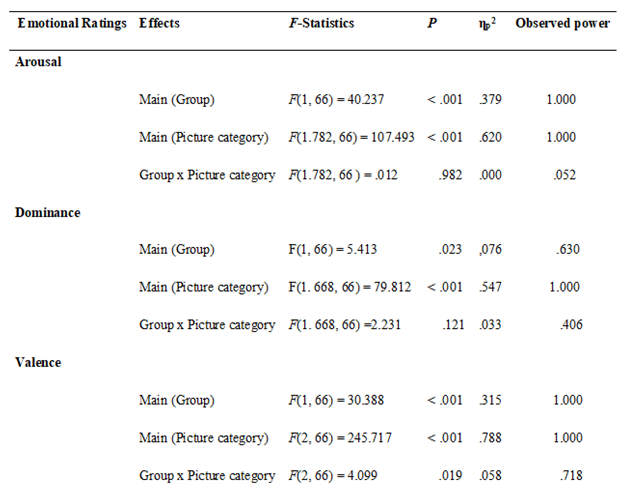

3.2. Emotional Ratings Analysis

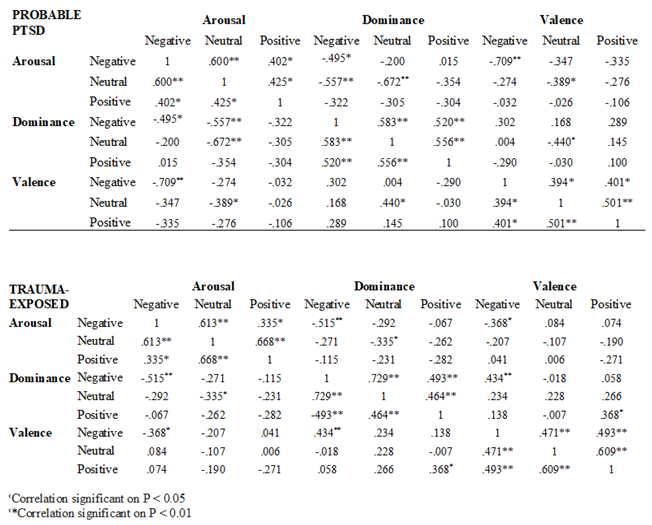

3.3. Correlations between Ratings

4. Discussion

5. Limitation and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III). Washington, DC: APA Publishing, 1980.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM V), Fifth Edition. Washington, DC: Author, 2013 https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

- Bassir Nia, A., Bender, R., Harpaz-Rotem, I. Endocannabinoid system alterations in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A review of developmental and accumulative effects of trauma. Chronic Stress, 2019, 3, 2470547019864096. [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.A. et al. Acute and chronic Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms in the emergence of Post traumatic Stress Disorder: A network analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 2017, 74(2), 135-142. [CrossRef]

- Enman, N.M., Arthur, K., Ward, S.J., Perrine, S.A., Unterwald, E.M. Anhedonia, reduced cocaine reward, and dopamine dysfunction in a rat model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry, 2015, 78, 871-879. [CrossRef]

- Miethe, S.; et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and its association with rumination, thought suppression and experiential avoidance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychopathol Behav Assess, 2023, 45(2), 480-495. [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, L., Wild, J. Emotion regulation, physiological arousal, and PTSD symptoms in trauma-exposed individuals. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry, 2014, 45(3), 360-367. [CrossRef]

- Spiller, T.R. et al. Emotional reactivity, emotion regulation capacity, and posttraumatic stress disorder in traumatized refugees: An experimental investigation. J Trauma Stress, 2019, 32(1), 32-41. [CrossRef]

- Wisco, B.E. et al. Effects of trauma-focused rumination among trauma-exposed individuals with and without posttraumatic stress disorder: An experiment. J Trauma Stress, 2023, 36, 285-298. [CrossRef]

- Freitag S, Braehler E, Schmidt S, Glaesmer H. The impact of forced displacement in World War II on mental health disorders and health-related quality of life in late life - a German population-based study. Int Psychogeriatr, 2013, 25(2), 310-319. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.S., Liddell, B.J., Nickerson, A. The relationship between post-migration stress and psychological disorders in refugees and asylum seekers. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 2016, 18(9):82. [CrossRef]

- Sandahl, H., Vindbjerg, E., Carlsson, J. Treatment of sleep disturbances in refugees suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. Transcult Psychiatry, 2017, 54, 806-23. [CrossRef]

- Bogic, M. et al. Factors associated with mental disorders in long-settled war refugees: Refugees from the former Yugoslavia in Germany, Italy, and the UK. Br J Psychiatry, 2012, 200, 216-223. [CrossRef]

- Jobst, S., Windeisen, M., Wuensch, A., Meng, M., Kugler, C. Supporting migrants and refugees with posttraumatic stress disorder: Development, pilot implementation, and pilot evaluation of a continuing interprofessional education for healthcare providers. BMC Med Educ, 2020, 20(1):311. [CrossRef]

- Koch, T., Liedl, A., Ehring, T. Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic factor in Afghan refugees. Psych Trauma: Theory, Res, Pract, Policy, 2020, 12(3), 235. [CrossRef]

- Porter, M., Haslam, N. Predisplacement and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons: A meta-analysis. JAMA, 2005, 294(5), 602-612. [CrossRef]

- Mollica, R.F., McInnes, K., Poole, C., Tor, S. Dose-effect relationships of trauma to symptoms of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder among Cambodian survivors of mass violence. Br J Psychiatry, 1998, 173, 482-488. [CrossRef]

- Morina, N., Akhtar, A., Barth, J., Schnyder, U. Psychiatric disorders in refugees and internally displaced persons after forced displacement: A systematic review. Front Psychiatry, 2018, 9, 433. [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, A. et al. Impact of cognitive reappraisal on negative affect, heart rate, and intrusive memories in traumatized refugees. Clin Psychol Sci, 2017, 5, 497-512. [CrossRef]

- Steel, Z. et al. Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 2009, 302(5), 537-49. [CrossRef]

- Carta, M.G. et al. A follow-up on psychiatric symptoms and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders in Tuareg refugees in Burkina Faso. Front Psychiatry, 2018, 9, 127. [CrossRef]

- Djelantik, A.A.A.M.J. et al. Post-migration stressors and their association with symptom reduction and non-completion during treatment for traumatic grief in refugees. Front Psychiatry, 2020, 11, 407. [CrossRef]

- Ehring, T., Quack, D. Emotion regulation difficulties in trauma survivors: The role of trauma type and PTSD symptom severity. Beh Ther, 2010, 41, 587-98. [CrossRef]

- Liddell, B.J. et al. Neural correlates of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, trauma exposure, and postmigration stress in response to fear faces in resettled refugees. Clin Psychol Sci, 2019, 27, 811-25. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B., Ocaka, K.F., Browne, J., Oyok, T., Sondorp, E. Factors associated with post-traumatic stress disorder and depression amongst internally displaced persons in northern Uganda. BMC Psychiatry, 2008, 8(1), 38. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Comprehensive mental health action plan 2013-2030. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240031029.

- Ben-Zion, Z. et al. Neural responsivity to reward versus punishment shortly after trauma predicts long-term development of Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms. Biol Psychiatry: Cogn Neurosci Neuroimag, 2022, 7(2), 150-161. [CrossRef]

- McCurry, K.L., Fruehm B.C., Chiu, P.H., King-Casas B. Opponent effects of hyperarousal and re-experiencing on affective habituation in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Biol Psychiatry Glob Open Sci, 2020, 5(2), 203-212. [CrossRef]

- Kujawa, A., Klein, D.N., Pegg, S., Weinberg, A. Developmental trajectories to reduced activation of positive valence systems: A review of biological and environmental contributions. Develop Cogn Neurosci, 2020, 43, 100791. [CrossRef]

- White, S.F., Costanzo, M.E., Blair, J.R., Roy, M.J. (2014). PTSD symptom severity is associated with increased recruitment of top-down attentional control in a trauma-exposed sample. Neuroimage: Clin, 2014, 7, 19-27. [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.A., Bryant, R.A., Gatt, J.M., Harris, A.W.F. Failure to differentiate between threat-related and positive emotion cues in healthy adults with childhood interpersonal or adult trauma. J Psychiatric Res, 2016, 78, 31-41. [CrossRef]

- Fonzo, G.A. Diminished positive affect and traumatic stress: A biobehavioral review and commentary on trauma affective neuroscience. Neurob Stress, 2018, 9, 214-230. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.G., Ullsperger, M. An update on the role of serotonin and its interplay with dopamine for reward. Front Human Neurosci, 2017, 11, 484. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00484/full.

- Bruce, S.E. et al. Altered emotional interference processing in the amygdala and insula in women with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Neuroimage Clin, 2012, 2, 43-49. [CrossRef]

- Park, J. et al. The association between alexithymia and posttraumatic stress symptoms following multiple exposures to traumatic events in North Korean refugees. J Psychosom Res, 2015, 78(1), 77-81. [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Jimenez, B. et al. Attention allocation to negatively-valenced stimuli in PTSD is associated with reward-related neural pathways. Psychol Med, 2023, 53, 4666-4674. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. et al. Differential effects of acute stress on anticipatory and consummatory phases of reward processing. Neurosci, 2014, 266, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- María-Ríos, C.E., Morrow, J.D. Mechanisms of shared vulnerability to Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and Substance Use Disorders. Front Behav Neurosci, 2020, 14, 6. [CrossRef]

- Seidemann, R., Duek, O., Jia, R., Levy, I., Harpaz-Rotem, I. The reward system and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Does trauma affect the way we interact with positive stimuli? Chronic Stress, 2021, 5. [CrossRef]

- Ashley, V., Swick, D. Angry and fearful face conflict effects in Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. Front Psychol, 2019, 10, 136. [CrossRef]

- Catani, C., Adenauer, H., Keil, J., Aichinger, H., Neuner, F. Pattern of cortical activation during processing of aversive stimuli in traumatized survivors of war and torture. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, 2009, 259(6), 340-351. [CrossRef]

- Dunkley, B.T., Wong, S.M., Jetly, R., Wong, J.K., Taylor, M.J. Post-traumatic stress disorder and chronic hyperconnectivity in emotional processing. Neuroimage: Clin, 2018, 20, 197-204. [CrossRef]

- Fani, N. et al. Attentional control abnormalities in posttraumatic stress disorder: Functional, behavioral, and structural correlates. J Affect Disord, 2019, 253, 343-351. [CrossRef]

- Zukerman, G., Pinhas, M., Ben-Itzhak, E., Fostick, L. Reduced electrophysiological habituation to novelty after trauma reflects heightened salience network detection. Neuropsychol, 2019, 134, 107226. [CrossRef]

- Nawijn, L. et al. Reward functioning in PTSD: A systematic review exploring the mechanisms underlying anhedonia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2005, 51, 189-204. [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.L., Milanak, M.E., Judah, M.R., Berenbaum, H. (2018). The association between PTSD and facial affect recognition. Psychiatry Res, 2018, 265, 298-302. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E.J., Miller, M.W., McKinney, A.E. Emotional processing in PTSD: Heightened negative emotionality to unpleasant photographic stimuli. J Nerv Ment Dis, 2009, 197(6), 419-426. [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; et al. The time course of the influence of valence and arousal on the implicit processing of affective pictures. PLoS ONE, 2012, 7(1), e29668. [CrossRef]

- Berle, D. et al. Personal wellbeing in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Association with PTSD symptoms during and following treatment. BMC Psychol, 2018, 6(1), 7. [CrossRef]

- Doolan, E.L., Bryant, R.A., Liddell, B.J., Nickerson, A. The conceptualization of emotion regulation difficulties, and its association with posttraumatic stress symptoms in traumatized refugees. J Anxiety Disord, 2017, 50, 7-14. [CrossRef]

- Mollica, R., Massagli, L., Silove, D. Measuring trauma, measuring torture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, 2004.

- Kronick, R. Mental health of refugees and asylum seekers: Assessment and intervention. Can J Psychiatry, 2018, 63(5):290-296. [CrossRef]

- Madoro, D. et al. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and associated factors among internally displaced people in South Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat, 2020, 16, 2317-2326. [CrossRef]

- Shou, H. et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy increases amygdala connectivity with the cognitive control network in both MDD and PTSD. Neuroimage: Clinicl, 2017, 14, 464-470. [CrossRef]

- Watkins, L.E., Sprang, K.R., Rothbaum, B.O. Treating PTSD: A review of evidence-based psychotherapy interventions. Front Behav Neurosci, 2018, 12, 258. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J., Van Elzakker, M., Shin, L. Emotion and cognition interactions in PTSD: A review of neurocognitive and neuroimaging studies. Front Integr Neurosci, 2012, 6, 89. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H. et al. Neural correlates of emotional reactivity and regulation in traumatized North Korean refugees. Transl Psychiatry, 2021, 11, 452. [CrossRef]

- Olson, E.A., Kaiser, R.H., Pizzagalli, D.A., Rauch, S.L., Rosso, I.M. Anhedonia in trauma-exposed individuals: Functional connectivity and decision-making correlates. Biol Psychiatry Glob Open Sci, 2017. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2451902217302008.

- Postel, C. et al. Variations in response to trauma and hippocampal subfield changes. Neurobiol Stress, 2021, 15, 100346. [CrossRef]

- Bradley, M.M., Lang, P.J. Measuring emotion: The Self-Assessment Manikin and the semantic differential, J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry, 1994, 25(1), 49-59. [CrossRef]

- Blekić, W.; et al. Affective ratings of pictures related to interpersonal situations. Front Psychol, 2021, 12, 627849. [CrossRef]

- Lang, P.J., Bradley, M.M., Cuthbert, B.N. International affective picture system (IAPS): Affective ratings of pictures and instruction manual (Tech. Rep. A-8). University of Florida, 2008.

- Berthold, S.M. et al. The HTQ-5: Revision of the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire for measuring torture, trauma, and DSM-5 PTSD symptoms in refugee populations. Eur J Public Health, 2019, 29(3), 468-474. [CrossRef]

- Silove, D. et al. Screening for depression and PTSD in a Cambodian population unaffected by war: Comparing the Hopkins Symptom Checklist and Harvard Trauma Questionnaire with the structured clinical interview. J Nervous Mental Dis, 2007, 195(2), 152-157. [CrossRef]

- Sigvardsdotter, E., Malm, A., Tinghög, P., Vaez, M., Saboonchi, F. Refugee trauma measurement: A review of existing checklists. Public Health Rev, 2016, 37, 10. [CrossRef]

- Vindbjerg, E., Carlsson, J., Mortensen, E.L., Elklit, A., Makransky, G. The latent structure of post-traumatic stress disorder among Arabic-speaking refugees receiving psychiatric treatment in Denmark. BMC Psychiatry, 2016, 16, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- de Fouchier, C. et al. Validation of a French adaptation of the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire among torture survivors from sub-Saharan African countries. Eur J Psychotraumatol, 2012, 3, 10. [CrossRef]

- Pino, O.; et al. Post-traumatic outcomes among survivors of the earthquake in central Italy of August 24, 2016. A study on PTSD risk and vulnerability factors. Psychiatric Quart, 2021, 92, 1489-1511 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Lang, P.J., Bradley, M.M., Cuthbert, B.N. International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Instruction manual and affective ratings. Technical report A-5. University of Florida, 2001.

- Abu Suhaiban, H., Grasser, L. R., Javanbakht, A. Mental health of refugees and torture survivors: A critical review of prevalence, predictors, and integrated care. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2019, 16(13), 2309. [CrossRef]

- Duan, H., Wang, L., Wu, J. Psychophysiological correlates between emotional response inhibition and posttraumatic stress symptom clusters. Scien Rep, 2018, 8, 16876. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P. et al. The underlying dimensions of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in an epidemiological sample of Chinese earthquake survivors. J Mood Disord, 2014, 28(4), 345-351. [CrossRef]

- Cuthbert, B.N., Kozak, M.J. Constructing constructs for psychopathology: The NIMH research domain criteria. J Abnor Psychol, 2013, 122(4), 928-937. [CrossRef]

- Förstner, B.R. et al. The associations of Positive and Negative Valence Systems, cognitive systems, and social processes on disease severity in anxiety and depressive disorders. Front Psychiatry, 2023, 16 (14), 1161097. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).