Submitted:

28 August 2024

Posted:

12 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

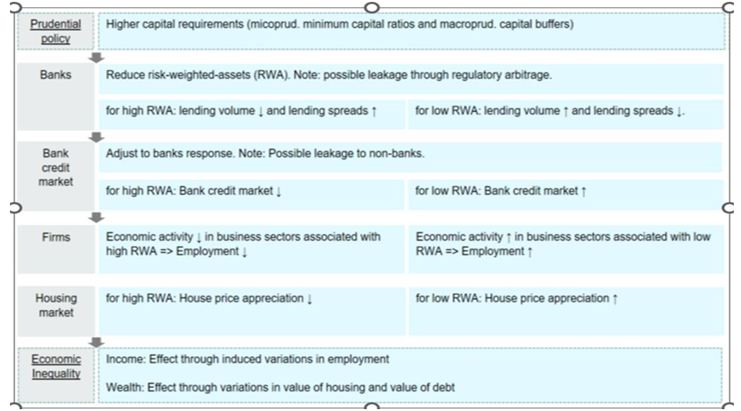

2.1. Theoretical Channels of Macroprudential Policy and Income Inequality

2.1.1. Transmission Channels

2.2. Review of Empirical Literature

3. Research Methods and Data Used for the Study

3.1. Bayesian Panel Vector Autoregressive (BPVAR) Model

3.2. The Two-Step System Dynamic Panel Data: BGMM: Bayesian Framework Setup

3.2.1. Dynamic Panel Data with GMME Estimators Setup

4. Analysis of Empirical Results

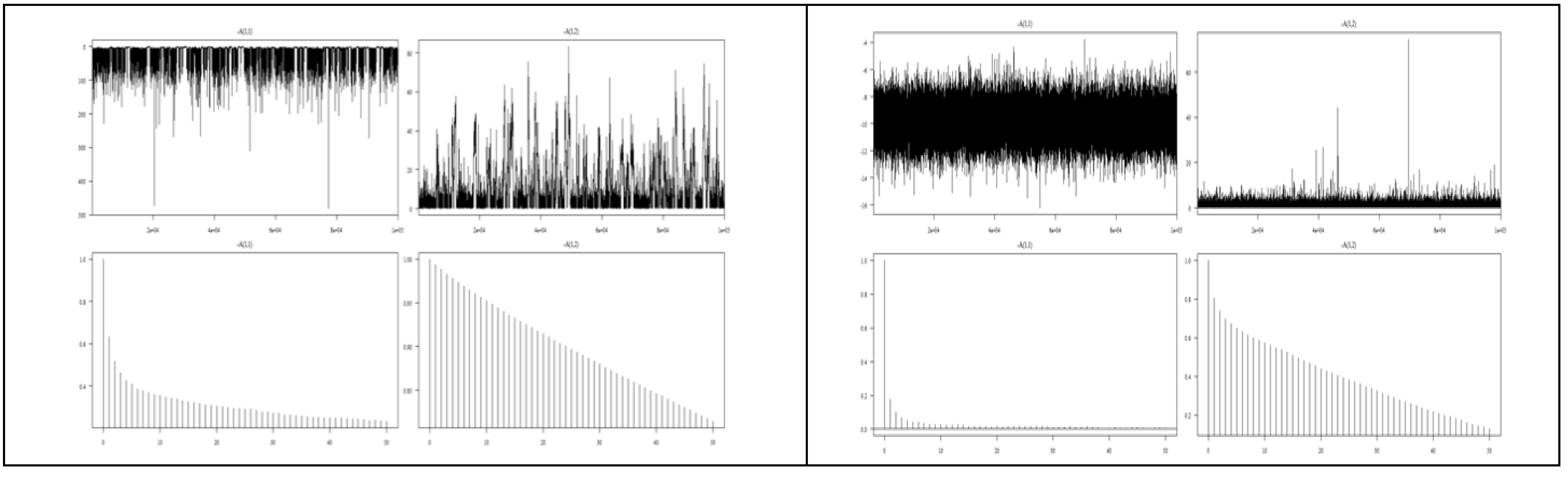

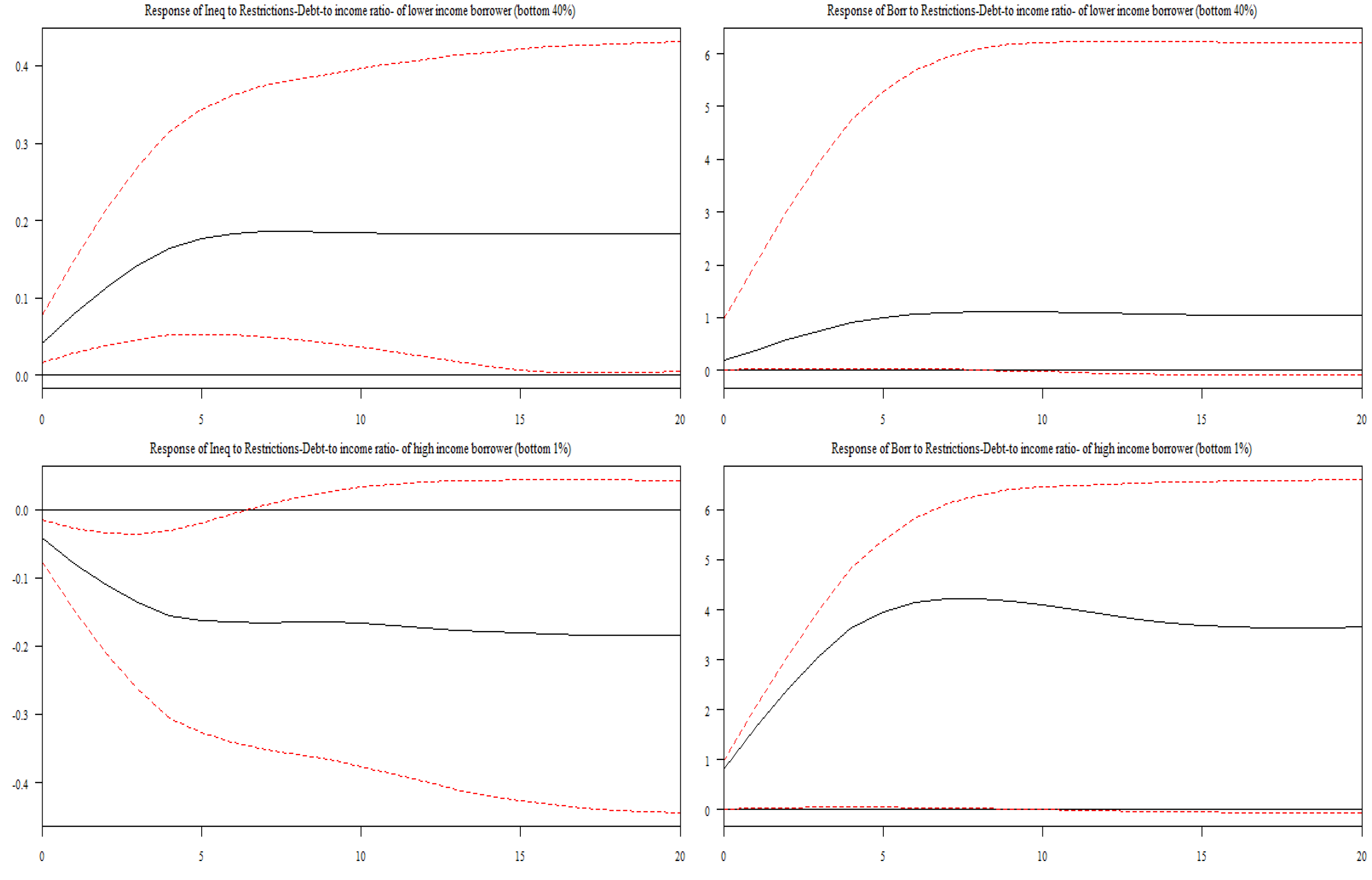

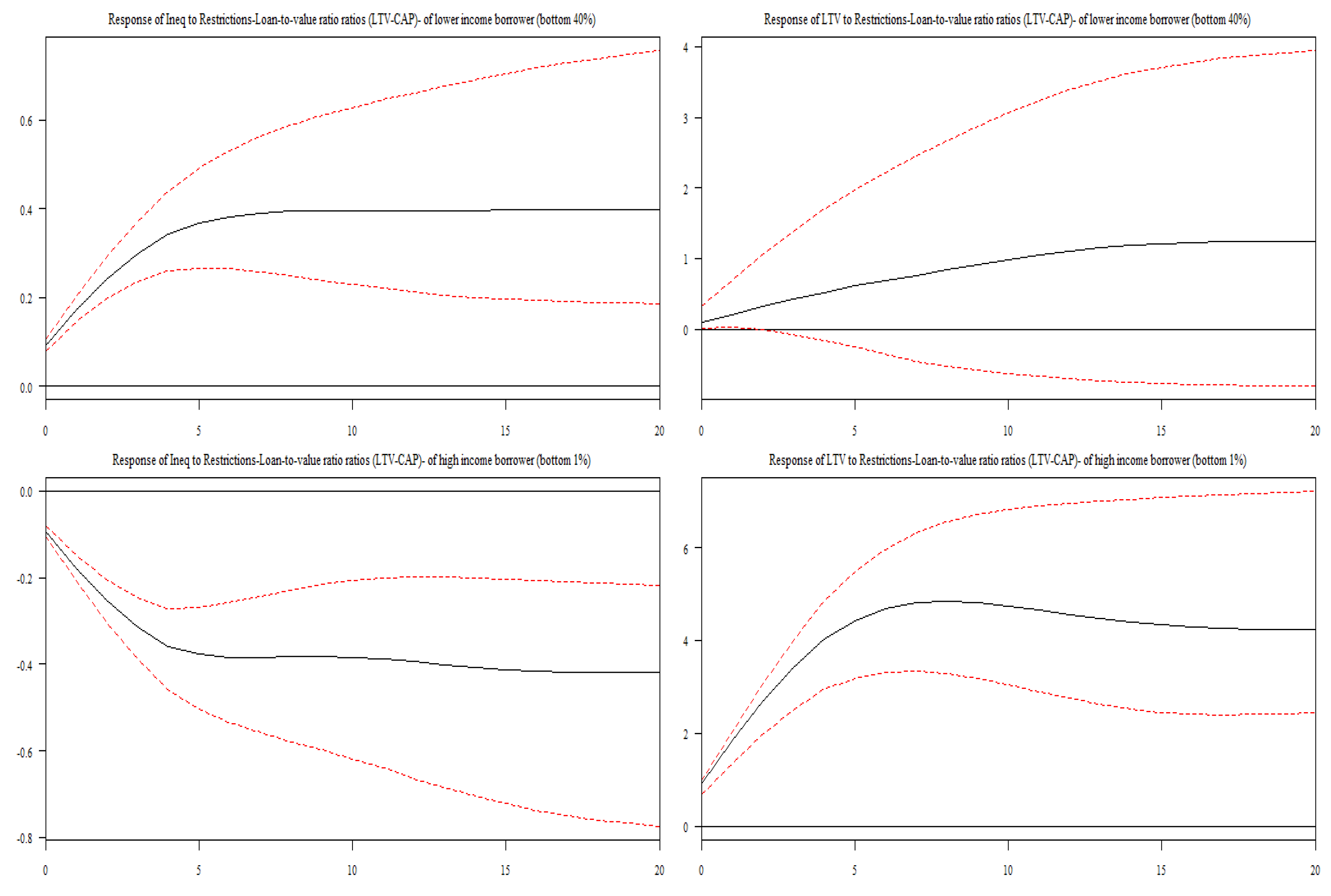

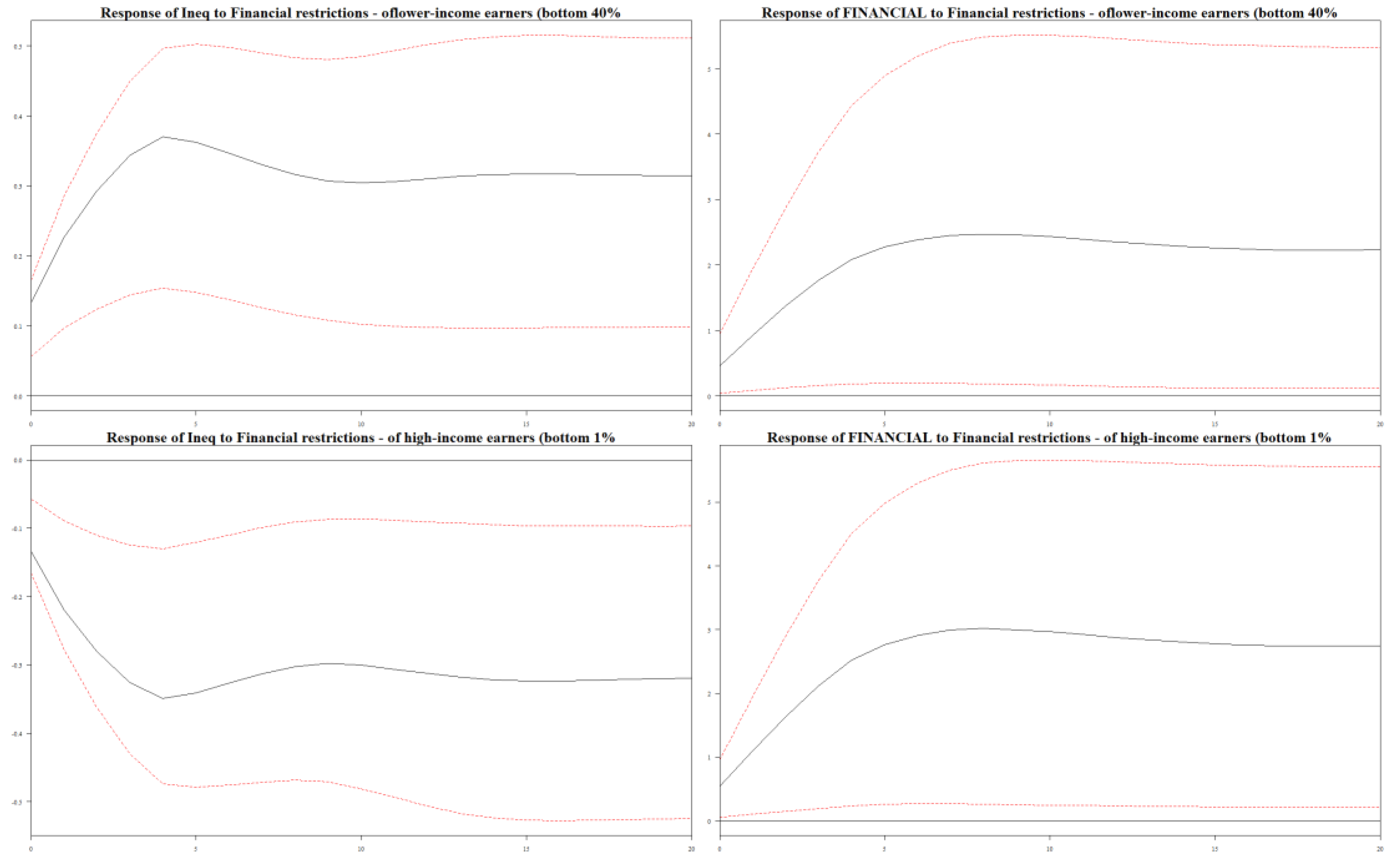

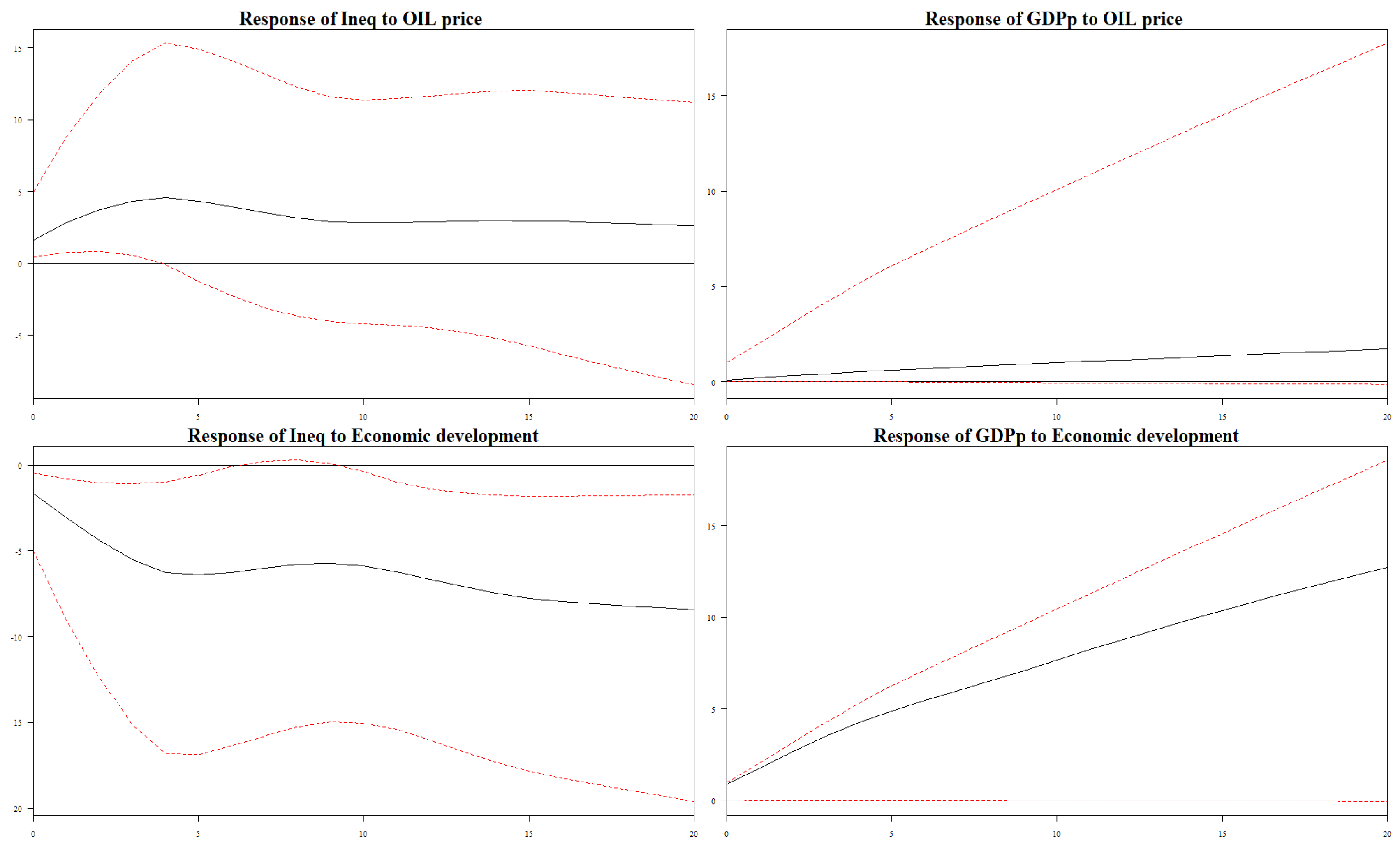

4.1. The Result of the BPVAR Model

4.1.1. Discussion of the BPVAR Results

4.2. Empirical Results of the Robustness and Sensitivity Analysis Using the BGMM

5. Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1. | The DTI ratio of lower-income borrowers (the bottom 40% of the income distribution) and high-income borrowers (the top 1% of the income distribution), as well as the LTV ratio of lower-income borrowers (the bottom 40% of the income distribution) and high-income borrowers (the top 1% of the income distribution). |

Appendix A

| Variables | SWIID | incPT10 | incPT1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Debt-to-Income ratio (DTI) | 2.78**[0.88] | 2.30**[0.32] | -1.13**[-0.48] |

| Loan-to-Value ratio (LTV) | 2.57[5.00] | 1.98[2.00] | -2.09**[3.94] |

| Financial instrument (FNCE) | 1.06**[0.06] | 1.96**[0.22] | -2.00**[1.00] |

| Government spending (GE) | -2.93*** [1.07] | -1.99** [0.98] | -1.33**[0.31] |

| Broad money supply (MBS) | 1.90**[0.28] | 2.90**[1.02] | 2.93**[0.28] |

| Economic development (GDPp) | -2.83** [1.00] | -2.30**[1.15] | -1.90** [0.50] |

| Oil price (OIL price) | 1.80**[0.28] | 2.93** [0.32] | 2.33[4.28] |

| Inflation (INFL) | 0.06**[0.009] | 0.23[1.10] | 0.90**[0.10] |

| Variables | SWIID | incPT10 | incPT1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Debt-to-Income ratio (DTI) | 0.87**[0.20] | 2.93***[0.32] | -2.04[2.56] |

| Loan-to-Value ratio (LTV) | 1.80[2.48] | 2.00[1.98] | -1.94[1.70] |

| Financial instrument (FNCE) | 2.60**[1.00] | 1.69***[0.22] | -1.78**[0.43] |

| Government spending (GE) | -1.03** [0.25] | -2.83*** [0.85] | -2.87***[0.27] |

| Broad money supply (MBS) | 1.03**[0.32] | 1.93**[0.32] | 2.44**[0.56] |

| Economic development (GDPp) | -2.30**[0.75] | -1.93**[0.55] | -1.37**[0.27] |

| Oil price (OIL price) | 2.00**[0.91] | 0.43[1.09] | 2.34 [3.56] |

| Inflation (INFL) | 0.43***[0.03] | 1.10**[0.32] | 2.06*** [0.96] |

| R2 | 0.9345 | 0.8857 | 0.9154 |

References

- Acharya, V.K,, Crosignani, B.M., Eisert, T., & McCann, F. (2017). The Anatomy of the Transmission of Macroprudential Policies: Evidence from Ireland. Presented at 16th International Conference on Credit Risk Evaluation, Interest Rates, Growth, and Regulation, Ireland. Evidence from Ireland.

- Adarov, M.A. Adarov, M.A. & Tchaidze, M.R. (2011). Development of financial markets in Central Europe: The case of the CE4 countries. International Monetary Fund 111, 11–101.

- Alvaredo, F., Chancel, L., Piketty, T., Saez, E. & Gabriel, Z. (2018). The elephant curve of global inequality and growth. AEA Papers and Proceedings 108, 103–08. [CrossRef]

- Andries, A.M. Andries, A.M. & Melnic, F. (2019). Macroprudential Policies and Economic Growth. Review of Economic and Business Studies 12, 95–112.

- Arregui, N., Benes, J., Krznar, I., Mitra, S. & Santos, A.O. (2013). Evaluating the Net Benefits of Macroprudential Policy: A Cookbook. IMF Working Paper No. 13/167, Monetary and Capital Markets, Research. Washington, DC: IMF. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2013/wp13167.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Atkinson, T. (2014); Public Economics in an Age of Austerity; New York; Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bernanke, Ben. 2015; Monetary Policy and Inequality. Ben Bernanke’s Blog at Brookings. Washington, DC; White House. [Google Scholar]

- Bivens, J. (2015). Gauging the Impact of the Fed on Inequality during the Great Recession. Hutchins Center on fiscal & monetary Policy at Brooking’s, Working Paper No. 12. Available online: https://files.epi.org/2015/quantitative-easing-and-inequality-josh-bivens.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Borio, C., Furfine, C. & Lowe, P. (2001). Procyclicality of Financial Systems and Financial Stability. BIS Papers. No.1. Basle; Bank for International Settlements.

- Canova, F. Canova, F. & Ciccarelli, M. (2004). Forecasting and turning point predictions in a Bayesian panel VAR model. Journal of Econometrics 120, 327–359.

- Carpantier, J., Olivera, J. & Van Kerm, P. (2018). Macroprudential policy and household wealth inequality. Journal of International Money and Finance 2018, 85, 262–277. [CrossRef]

- Carpantier, J.F., Olivera, J., & van Kerm, P. (2018). Macroprudential policy and household wealth inequality. Journal of International Money and Finance 85, 262–277.

- Casiraghi, M., Gaiotti, E. Rodano, L & Secchi, A. (2018). A ‘reverse Robin Hood’? The distributional implications of non-standard monetary policy for Italian households. Journal of International Money and Finance 2018, 85, 215–35.

- Cerutti, E., Claessens, S. & Laeven, L. (2017). The use and effectiveness of macroprudential policies: New evidence. Journal of Financial Stability 28, 203–24. [CrossRef]

- Cerutti, E.R., Claessens, S. & Laeven, L. (2016). The use and effectiveness of macroprudential policies: New evidence. Journal of Financial Stability 28, 203–24.

- Ciccarelli, M. & Rebucci, A. (2003). Measuring Contagion with a Bayesian Time-Varying coefficient model (September). IMF Working Paper, No. 03/171. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=880216.

- Clerca, L. Clerca, L., Dervizb, A., Mendicinoc, C., Moyend, S., Nikolove, K., Straccaf, L., Suarezg., J. & Vardoulakish, A.P. (2015). Capital regulation in a macroeconomic model with three layers of default. International Journal of Central Banking 11, 9–63.

- Crespo-Cuaresma, J. Crespo-Cuaresma, J. & Fernandez-Amadorb, O. (2013). Business cycle convergence in EMU: A first look at the second moment. Journal of Macroeconomics 37, 265–284.

- Davityan, K. (2018). The distributive effect of monetary policy: The top one percent makes the difference. Economic Modelling 65, 106–118. [CrossRef]

- Dieppe, A., Legrand, R. & van Roye, B. (2016). The Bayesian Estimation, Analysis and Regression toolbox (BEAR). Working Paper, No. 1934. European Central Bank.

- Doan T., Litterman, R. & Sims, C. (1984). Forecasting and Conditional Projection Using Realistic Prior Distributions. Econometric Reviews 3, 1–100.

- Doepke, M. & Schneider, M. (2006). Inflation and the redistribution of nominal wealth. Journal of Political Economy 114, 1069–1097.

- Elekdag, S. & Wu, Y. (2011). Rapid credit growth: Boon or boom-bust? Working Paper, No. 11/241, International Monetary Fund.

- Frees, E. (1995). Assessing cross-sectional correlation in panel data. Journal of Econometrics 69, 393–414. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. (1937). The use of ranks to avoid the assumption of normality implicit in the analysis of variance. Journal of the American Statistical Association 32, 675–701. [CrossRef]

- Frost, J. & van Stralen, R. (2017). Macroprudential policy and income inequality. Journal of International Money and Finance 85, 278–290. [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, O. & Martin, V.D. (2022). Do macroprudential measures increase inequality? Evidence from the euro area household survey, Working Paper Series, No. 2567, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, June.

- Guerello, C. (2018). Conventional and unconventional monetary policy vs. household’s income distribution: An empirical analysis for the Euro Area. Journal of International Money and Finance 85, 187–214. [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.D.F. & Tzavalis, E. (1999). Inference for unit roots in dynamic panels where the time dimension is fixed. Journal of Econometrics 91, 201–226.

- Hauner, T. (2016). Aggregate wealth and its distribution as determinants of financial crises. The Journal of Economic Inequality 18, 319–338. [CrossRef]

- Im, K.S.M., Pesaran, H. & Shin.Y. (2003). Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics 115, 53–74. [CrossRef]

- International monetary Fund (IMF) (2014). Staff guidance note on macroprudential policy. IMF Policy Paper, December.

- Inui., M., Sudou, N. & Yamada, T. (2017). Effects of Monetary Policy Shocks on Inequality in Japan. Bank of Japan Working Paper, No. 17-e-3. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2982887 (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Juan-Francisco, A., Gómez-Fernández, N. & Claramunt, C.O. (2018). Effects of unconventional monetary policy on income and wealth distribution: Evidence from United States and Eurozone. Panoeconomicus First-Online (00), 7-7. [CrossRef]

- Kostantinou, P., Rizos, A and Stratopoulou, A. (2021). Macroprudential policies and income inequality in former transition economies. Economic Change and Restructuring 55, 1005–1062. [CrossRef]

- Lenza, M. & Slacalek. J. (2018). How Does Monetary Policy Affect Income and Wealth Inequality? Evidence from Quantitative Easing in the Euro Area. ECB Working Paper Series, No. 2190/October 201. EU publications. [CrossRef]

- Love, I. & Zicchino, L. (2006). Financial development and dynamic investment behavior: Evidence from panel vector autoregression. Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 46, 190–210.

- Manuel Rupprecht, M. (2020). Income and wealth of euro area households in times of ultra-loose monetary policy: Stylised facts from new national and financial accounts data. Austrian Economic Association 47, 281–302.

- Martynova, N. (2015). Effect of bank capital requirements on economic growth: A survey. De Nederlandsche Bank Working Paper, No. 467.

- Mendicino, C., Hoerova, M., Nikolov, K., Schepens, G. & van den Heuvel, S. (2018). Benefits and costs of liquidity regulation. ECB Working Paper, No. 2169. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecb.wp2169.en.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- Mumtaz, H. & Theophilopoulou, A. (2017). The impact of monetary policy on inequality in the UK. An empirical analysis. European Economic Review 98, 410–423. [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H. (2004). General diagnostic tests for cross section dependence in panels. IZA Discussion Paper No. 1240. docs.iza.org/dp1240.pdf.

- Piketty, T. (2014); Capital in the 21st Century; Cambridge; Harvard University Press.

- Punzi, M.T & Rabitsch, K. (2018). Effectiveness of macroprudential policies under borrower heterogeneity. Journal of International Money and Finance 85, 251–261.

- Rajan, R. (2010). Fault Lines: How hidden Fractures Still Threaten the world Economy; Princeton; Princeton University Press.

- Reinhart, C.M. & Rogoff, K.S. (2009). Growth in a time of debt. American Economic Review 100, 573–578.

- Rubio, M. & Carrasco-Gallego, J.A. (2014). Macroprudential and monetary policies: Implications for financial stability and welfare. Journal of Banking & Finance 49, 326–336.

- Rubio, M. & Unsal, F.D. (2017). Macroprudential policy, incomplete information and inequality: The case of low-income and developing countries. IMF Working Paper, No. WPIEA2017059/36. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2017/03/21/Macroprudential-Policy-Incomplete-Information-and-Inequality-The-case-of-Low-Income-and-44752 (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Saiki, A. & Frost, J. (2014). Does unconventional monetary policy affect inequality? Evidence from Japan. Applied Economics 46, 4445–4454. [CrossRef]

- Sarfati, H. Sarfati, H. (2016). OECD. In it together: Why less inequality benefits all. Paris, 2015. p. 332 ISBN 978–264-23266-2. International Social Security Review 68, 115–17. [CrossRef]

- Sims, C.A. (1980). Macroeconomics and reality. Econometrica 48, 1–48. [CrossRef]

- Solt, F. (2020). The Standardized World Income-inequality Database. Social Science Quarterly 90, 231–242. [CrossRef]

- Solt, F. (2021). Measuring Income Inequality Across Countries and Over Time: The Standardized World Income Inequality Database. Social Science Quarterly. 101, pp. 1183–1199, SWIID Version 9.2, December 2021. Available online: https://fsolt.org/swiid/ (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- Stiglitz. J. (2015). Inequality and Economic Growth. The Political Quarterly 86, 134–155. [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh-Hesary, F., Yoshino, N. & Shimizu, S. (2018). The Impact of Monetary and Tax Policy on Income Inequality in Japan. ADBI Working Paper 837. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325967488_The_Impact_of_Monetary_and_Tax_Policy_on_Income_Inequality_in_Japan (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Tenreyro, S and Thwaites, G. (2016). Pushing on a tring: US Monetary Policy Is Less Powerful in Recessions. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 8, 43–74.

- Tzur-Ilan, N. (2016).The effect of credit constraints on housing choices: The case of LTV limits. Paper presented at Bank of Israel, Hebrew Universit, Research Department Conference, December 2016; Available online: https://www.boi.org.il/he/NewsAndPublications/PressReleases/Documents/%D7%A0%D7%99%D7%A6%D7%9F%20%D7%A6%D7%95%D7%A8%20%D7%90%D7%99%D7%9C%D7%9F.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- World Development Indicators. World Development Indicators. (WDI)A (2023), World Bank Washington, D.C. Available online: http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Zellner, A., & Hong, C. (1989). Forecasting international growth rates using Bayesian shrinkage and other procedures. Journal of Econometrics 40, 183–202. [CrossRef]

- Zellner, A., Hong, C, & Min. C. (1991). Forecasting turning points in international output growth rates using Bayesian exponentially weighted autoregression, time-varying parameter, and pooling techniques. Journal of Econometrics 49, 275–304. [CrossRef]

- Zinman, J. (2010). Restricting consumer credit access: Household survey evidence on effects around the Oregon rate cap. Journal of Banking and Finance 34, 546–556. [CrossRef]

- Zungu, L.T. & Greyling, L. (2023). Investigating the asymmetric effect of income inequality on financial fragility in South Africa and selected emerging markets: A Bayesian approach with hierarchical priors. International Journal of Emerging Markets Vol. ahead-of-print, No. ahead-of-print. [CrossRef]

- Zungu, L.T., Greyling, L. & Mbatha, N. (2023). Nonlinear Dynamics of the Development-Inequality Nexus in Emerging Countries: The Case of a Prudential Policy Regime. Economies 10, 120.

| Descriptive Statistics | Im–Pesaran–Shin | Harris–Tzavalis | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mea | Sth.d | Min | Max | SKW | KUR | JB-ST | JB-P | Level | 1st ∆ | Inte | Level | 1st ∆ | Inte |

| SWIID | 48.29 | 6.33 | 8.100 | 63.50 | -0.30 | 3.04 | 11.60 | 0.00 | 1.77 | -5.99*** | I(1) | 2.37 | -15.83*** | I(1) |

| incPalma-r | 40.40 | 5.09 | 4.00 | 56.90 | -0.98 | 2.00 | 9.40 | 0.00 | 2.44 | -7.40*** | I(1) | 0.60 | -17.99*** | I(1) |

| incPT10 | 50.54 | 0.06 | 30.58 | 65.44 | -0.03 | 2.19 | 8.23 | 0.01 | 1.48 | -4.96*** | I(1) | 0.68 | -4.41*** | I(1) |

| incPT1 | 45.39 | 0.04 | 8.10 | 63.50 | -0.33 | 2.16 | 35.51 | 0.00 | 2.46 | -6.88*** | I(1) | 3.89 | -15.45*** | I(1) |

| DTI | 23.56 | 0.02 | 0 | 1 | −0.22 | 2.73 | 20.33 | 0.00 | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| LTV | 35.25 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | −0.30 | 2.00 | 16.42 | 0.00 | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| FNCE | 27.94 | 0.40 | 0 | 1 | 0.10 | 2.43 | 13.54 | 0.00 | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| OIL price | 4.62 | 0.27 | 4.08 | 6.57 | -0.12 | 1.98 | 80.85 | 0.00 | -0.44 | -3.79** | I(1) | 0.72 | -8.80*** | I(1) |

| GE | 8.24 | 8.34 | 14.48 | 3.62 | -0.23 | 3.09 | 76.09 | 0.00 | -1.20 | -8.99*** | I(1) | 0.11 | -17.54*** | I(1) |

| MBS | 10.92 | 112.60 | 75.66 | 61.90 | -0.11 | 3.87 | 70.8 | 0.08 | 0.33 | -6.11 | I(1) | 2.41 | -14.59*** | I(1) |

| GDPp | 10.92 | 112.60 | 75.66 | 61.90 | -0.11 | 3.87 | 70.8 | 0.08 | 0.33 | -6.11 | I(1) | 2.41 | -14.59*** | I(1) |

| INFL | 6.92 | 112.60 | 75.66 | 61.90 | -0.11 | 3.87 | 70.8 | 0.08 | 0.33 | -6.11 | I(1) | 2.41 | -14.59*** | I(1) |

| Pedroni Tests for Cointegration | Tests for Cross-Sectional Independence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Augmented Dickey–Fuller t | 6.34 | Pr = 0.01 | Friedman’s test | 111.00 | Pr = 0.00 |

| Modified Phillips–Perron t | 4.64 | Pr = 0.08 | Frees’ test | 0.82 | Pr = 0.00 |

| Phillips Perron t | 6.00 | Pr = 0.000 | Pesaran’s test | 12.65 | Pr = 0.00 |

| Variables | SWIID | incPalma-ratio | incPT10 | incPT1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Debt-to-Income ratio (DTI) | 2.98**(1.00) | 3.87**(1.10) | 1.39***(0.10) | -3.22**(0.89) |

| Loan-to-Value ratio (LTV) | 3.43(2.20) | 1.92**(0.31) | 1.90(2.20) | -1.98(1.80) |

| Financial instrument (FNCE) | 2.01**(0.90) | -1.90**(0.50) | 2.70***(0.29) | -2.90**(0.50) |

| Government spending (GE) | -4.00**(2.00) | -2.10**(0.69) | -1.90**(0.90) | 1.30**(0.22) |

| Broad money supply (MBS) | 2.11***(0.10) | 3.77**(1.00) | 1.00**(0.10) | 2.50**(0.70) |

| Economic development (GDPp) | -3.00**(1.20) | -2.04**(0.70) | -2.44** (0.80) | -3.32**(1.30) |

| Oil price (OIL price) | 2.20***(0.24) | 3.09 **(0.90) | 2.10**(0.44) | 1.90***(0.20) |

| Inflation (INFL) | 2.98**(1.00) | 0.49***(0.04) | 2.87**(0.89) | 2.32**(1.00) |

| AR (1): p-value | 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.008 |

| AR (2): p-value | 0.320 | 0.230 | 0.580 | 0.450 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).