Submitted:

29 August 2024

Posted:

30 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Works and Research Gap

| Game-related parameter | Source |

|---|---|

| Genesis | [21] |

| Gameplay goal/ mechanics | [21,23,25,26] |

| Challenge | [21] |

| Rules/ dynamics | [21,23,25] |

| Boundaries | [21] |

| Feedback | [21] |

| Identification data (name, release date) | [22,25,26] |

| Type/ technology | [22,25,26] |

| Genre | [22,25,26] |

| Aesthetics/ graphics | [23] |

| Process-related parameter | Source |

|---|---|

| Participant gender Participant age Religion Seniority in community |

[5] [5,22,24] [5] [5] |

| Supported SDG | [22] |

| Game topic/purpose of use | [22,24,26] |

| Location | [24] |

| Policy stage | [26,27] |

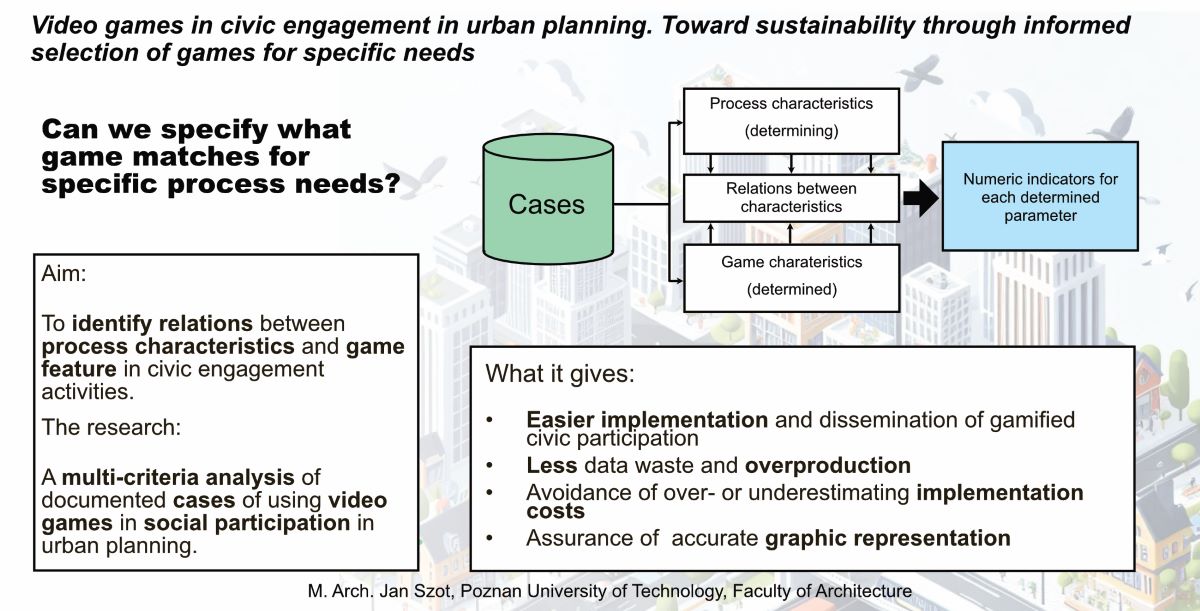

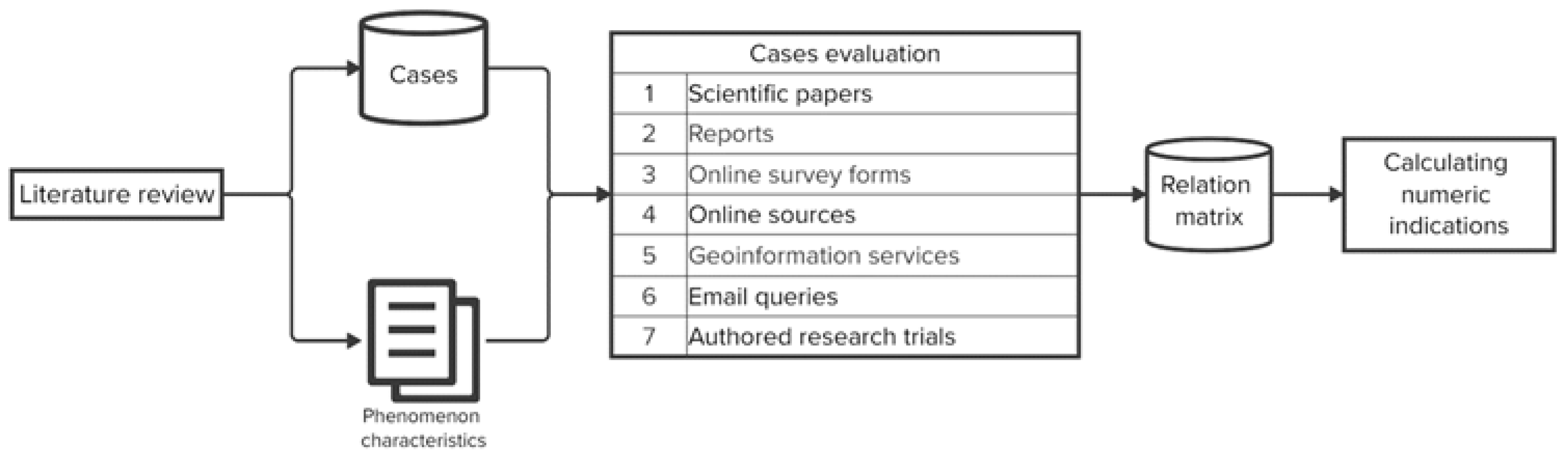

3. Concept and Development of the Tool Supporting Selection of Video Games for Participatory Process

- Scientific papers – works of researchers presenting selected case studies, provided most data for the study.

- Reports – publications of Non-Government Organizations that carried out some of the cases.

- Online survey forms – authored forms sent to researchers and other people involved in the participatory process, full survey is included in Appendix A.

- Internet sources – websites of serious game developers used in several cases

- Geoinformation services – platforms such as Google Earth provide information about areas of investigated cases.

- Email queries – correspondence with organizers of some cases provided information about participants and conducted process.

- Authored research trials - covered selected productions used in some cases and provided information on graphic style.

3.3. Evaluated Parameters

- Area – numeric value expressed in square meters describing the development area.

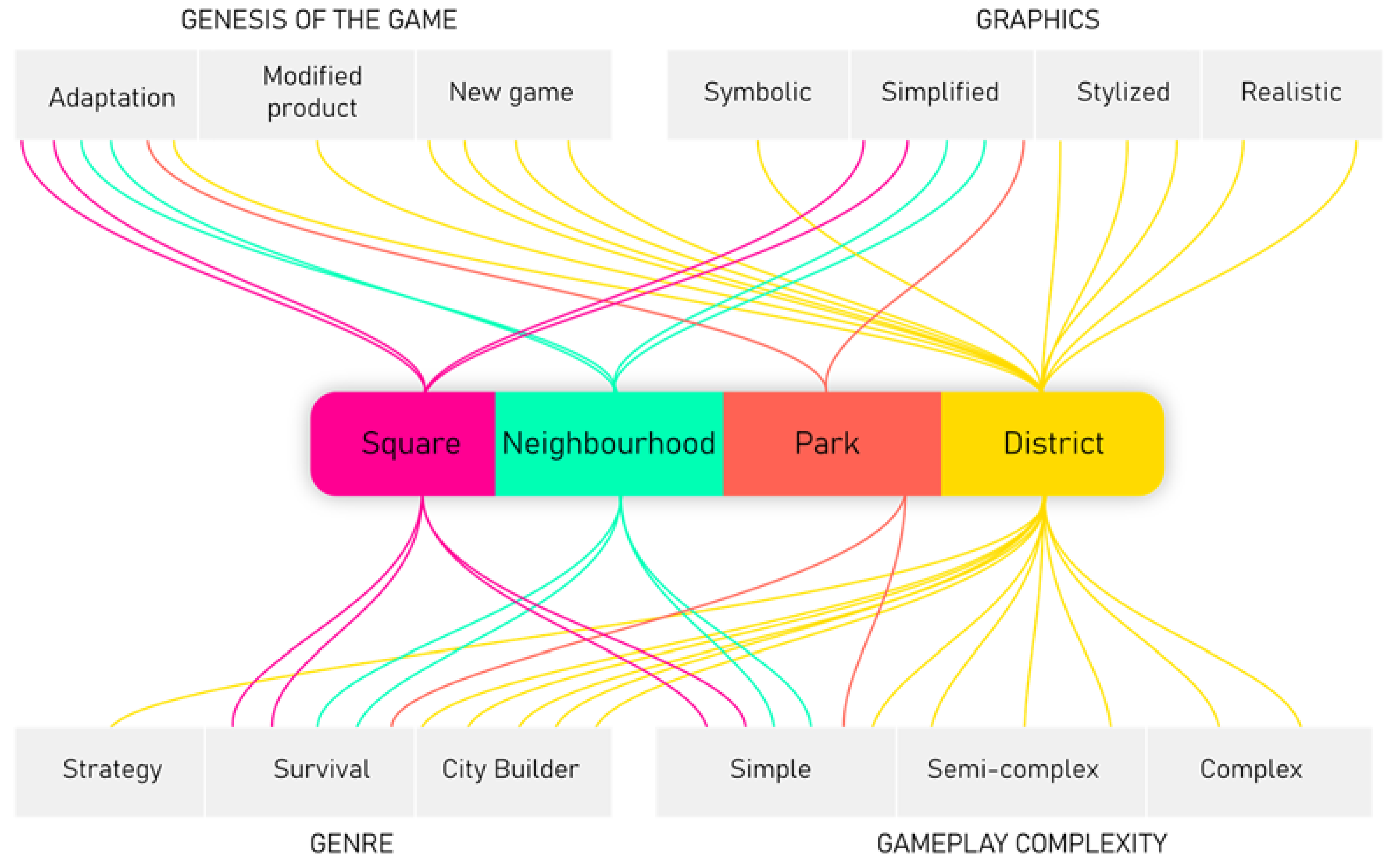

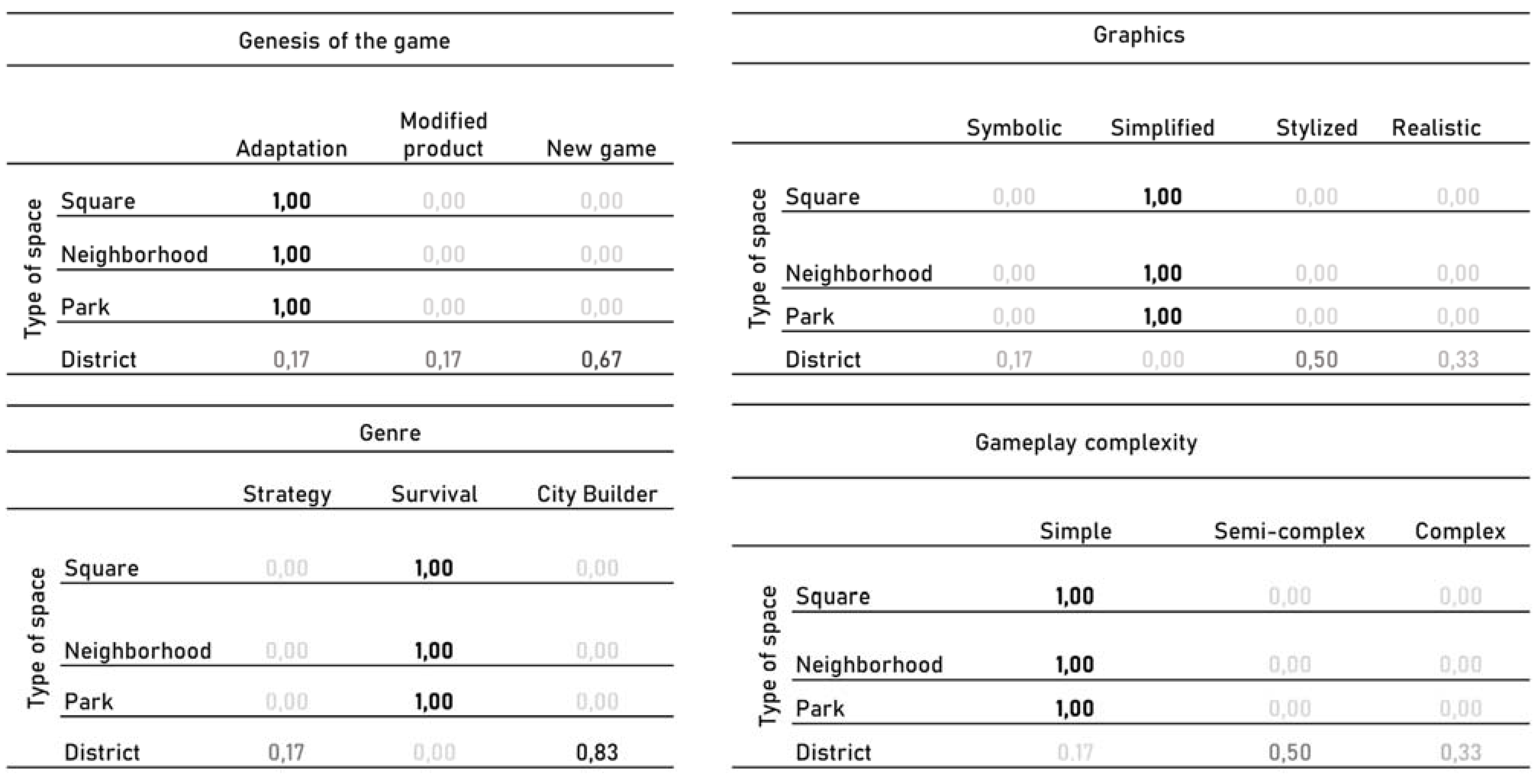

- Type of space – parameter presenting the general characteristic of the space ex. street, square, neighborhood, or district.

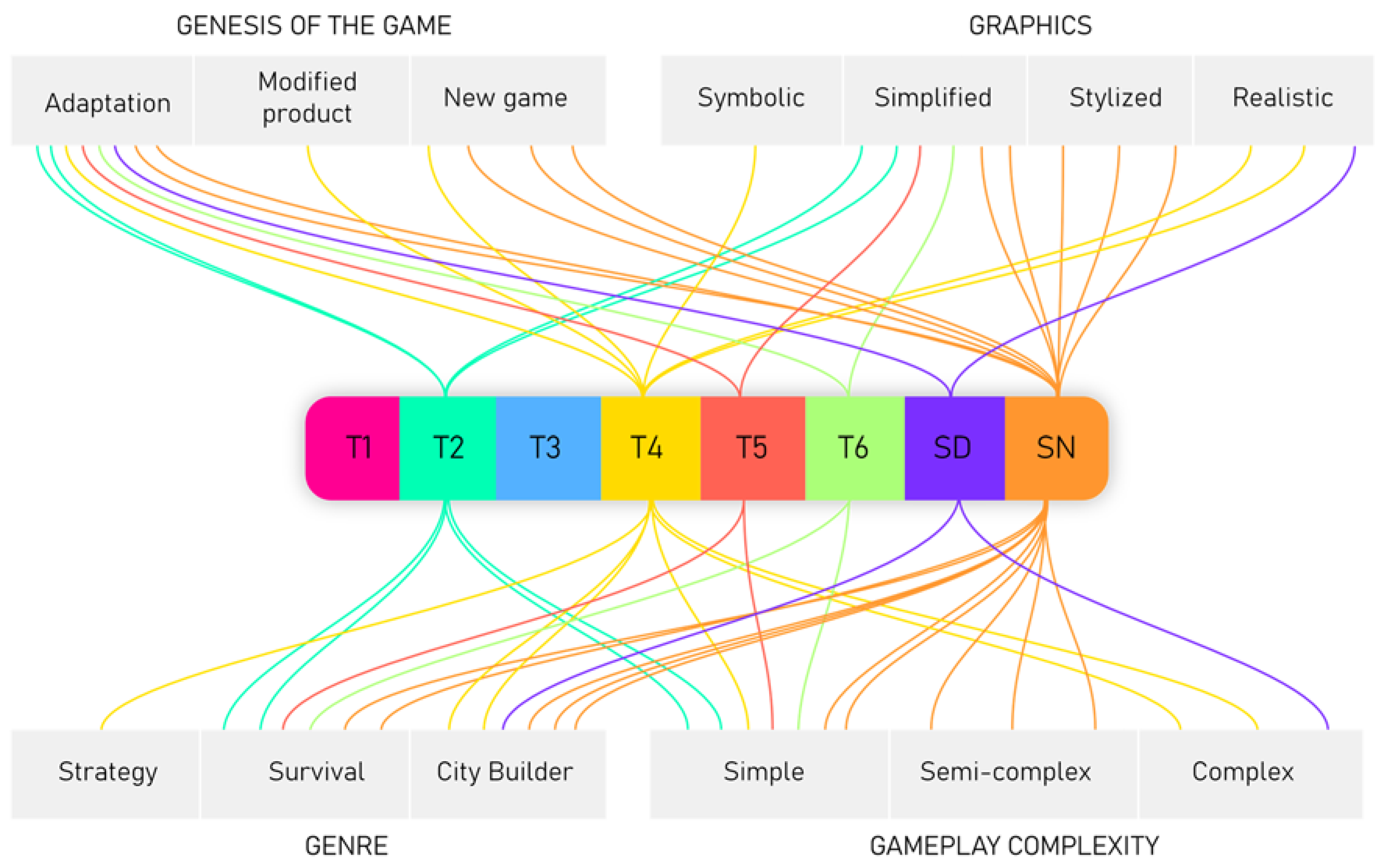

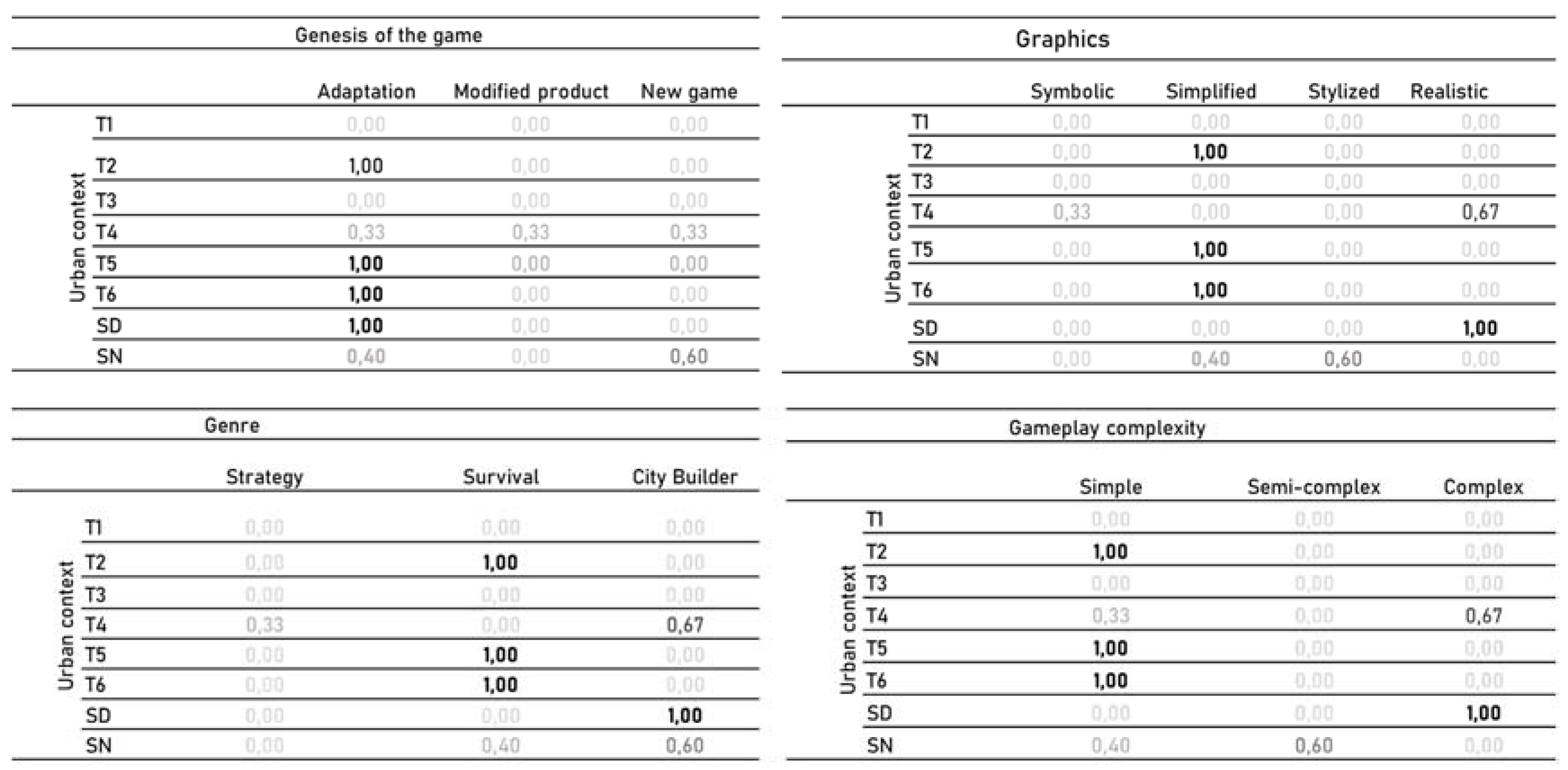

- Urban context – based on CNU urban transects, this parameter describes the surroundings of the subject area such as downtown, suburbs, and rural areas. To refer to non-formal settlements specific to the global south known commonly as slums additional value (SN) was added.

- Number of participants – a numeric value representing a number of participants from a variety of interested stakeholder groups.

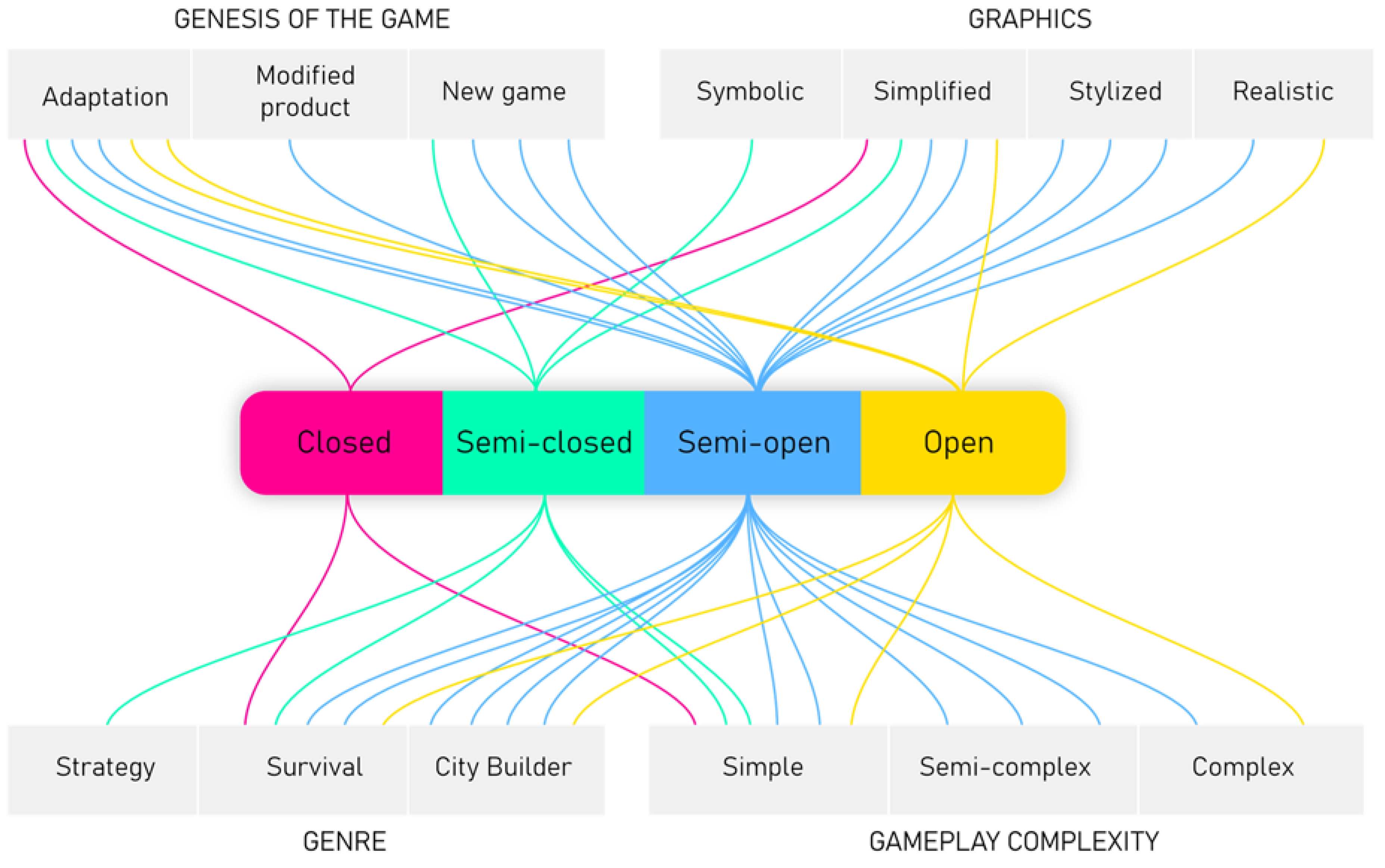

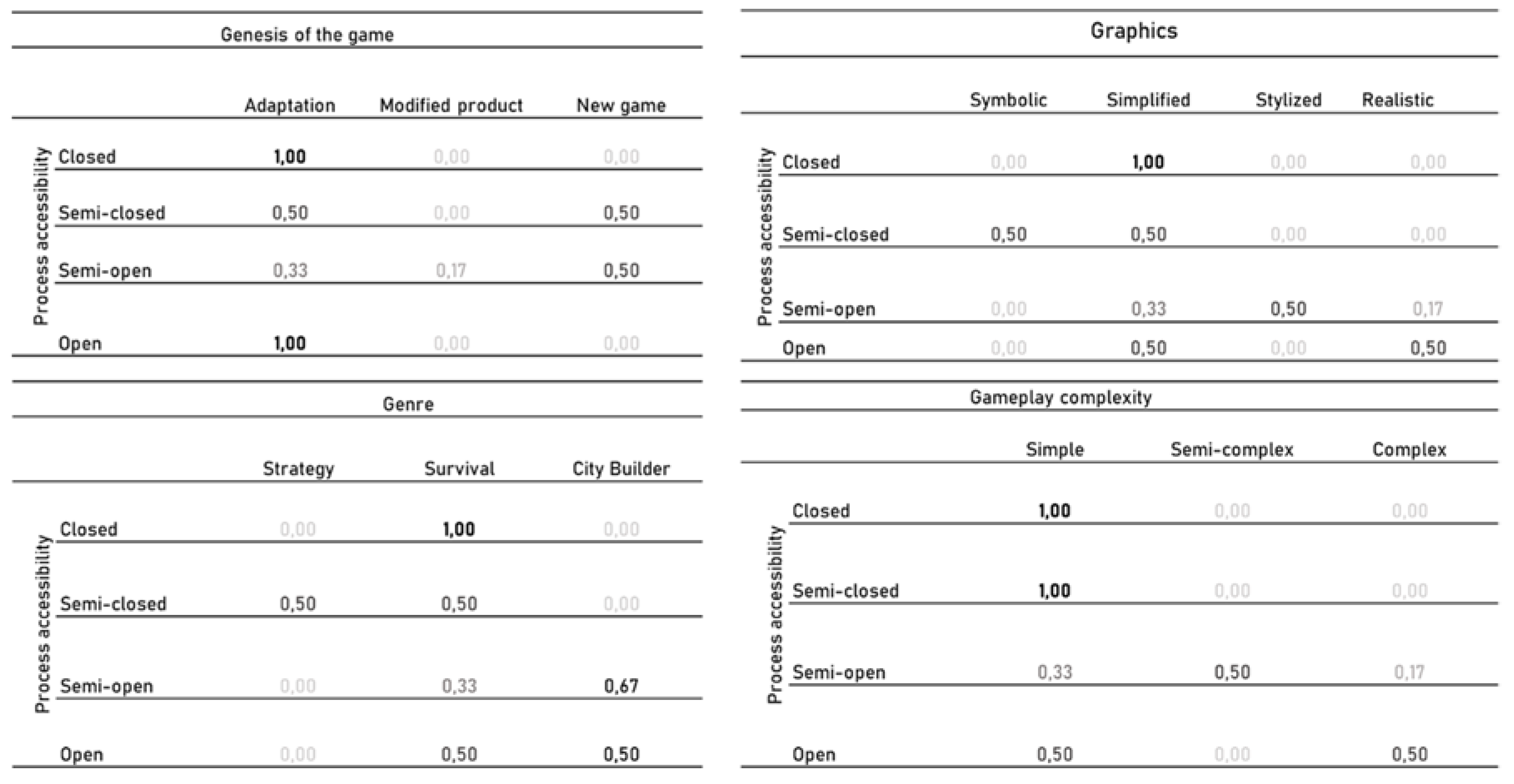

- Accessibility of the process – open for a fully accessible process (anyone can join), semi-open for fully open but with a selection of final participants, semi-closed for processes addressing specific groups of users (ex. students or workers of certain facilities), and closed for process dedicated to specific users.

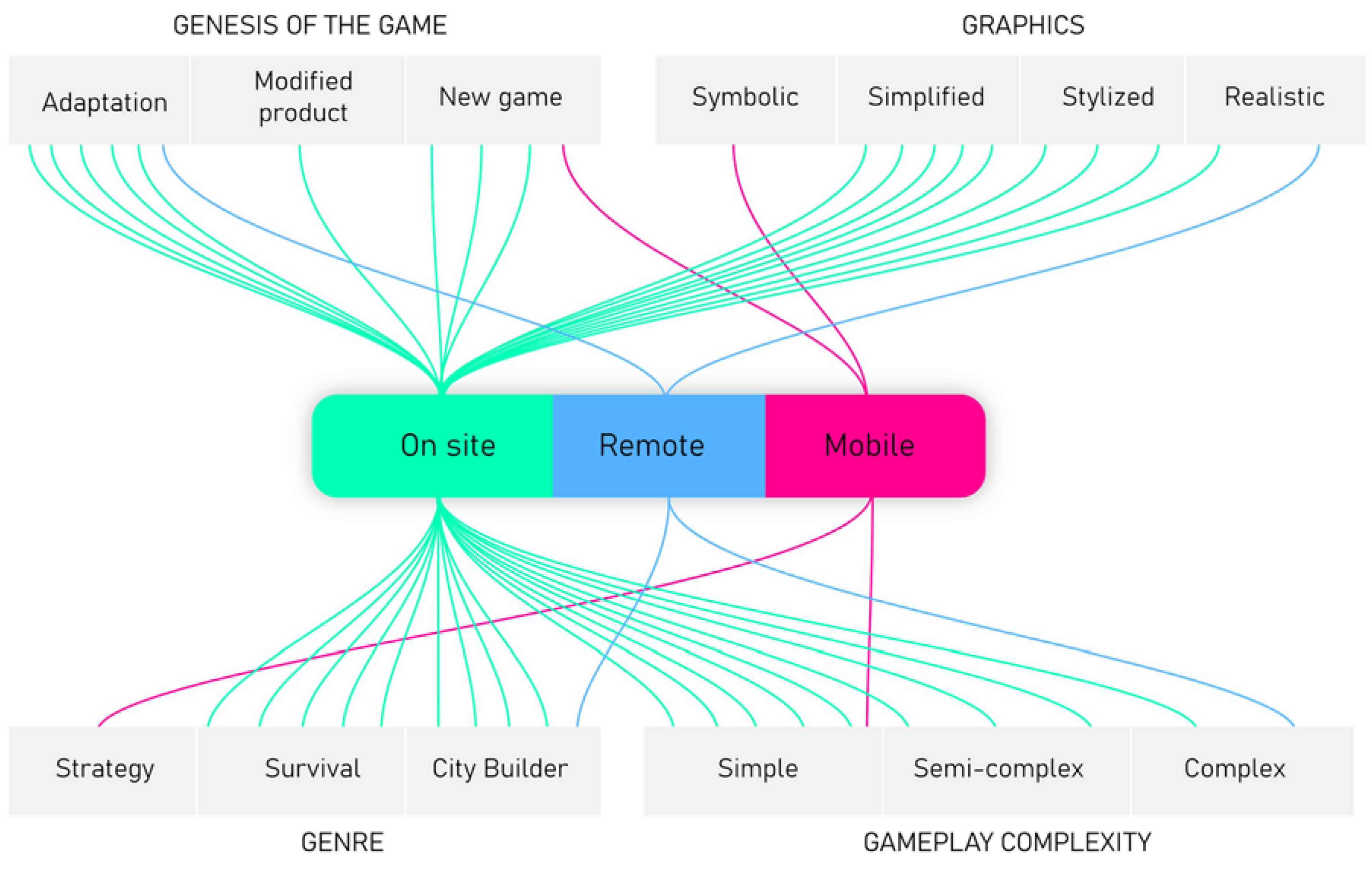

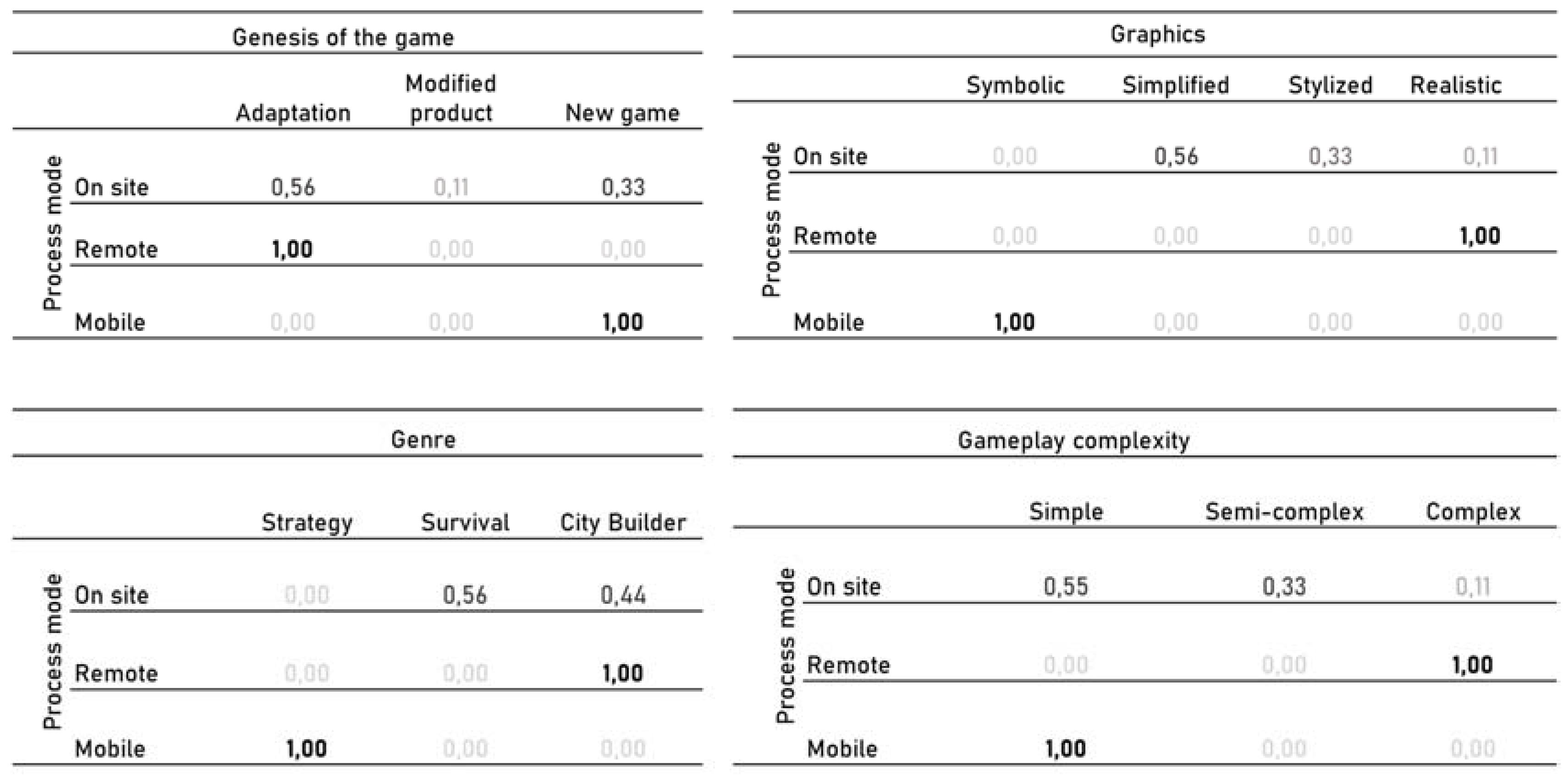

- Mode of the process – remote, mobile, on-site, hybrid respectively for the process including remote participation using stationary devices, remote participation using smartphones, smartwatches, and other mobile appliances, on-site participation at the designated place and time, a process combining the aforementioned modes.

- Level of participation – according to the commonly used Arnstein ladder.

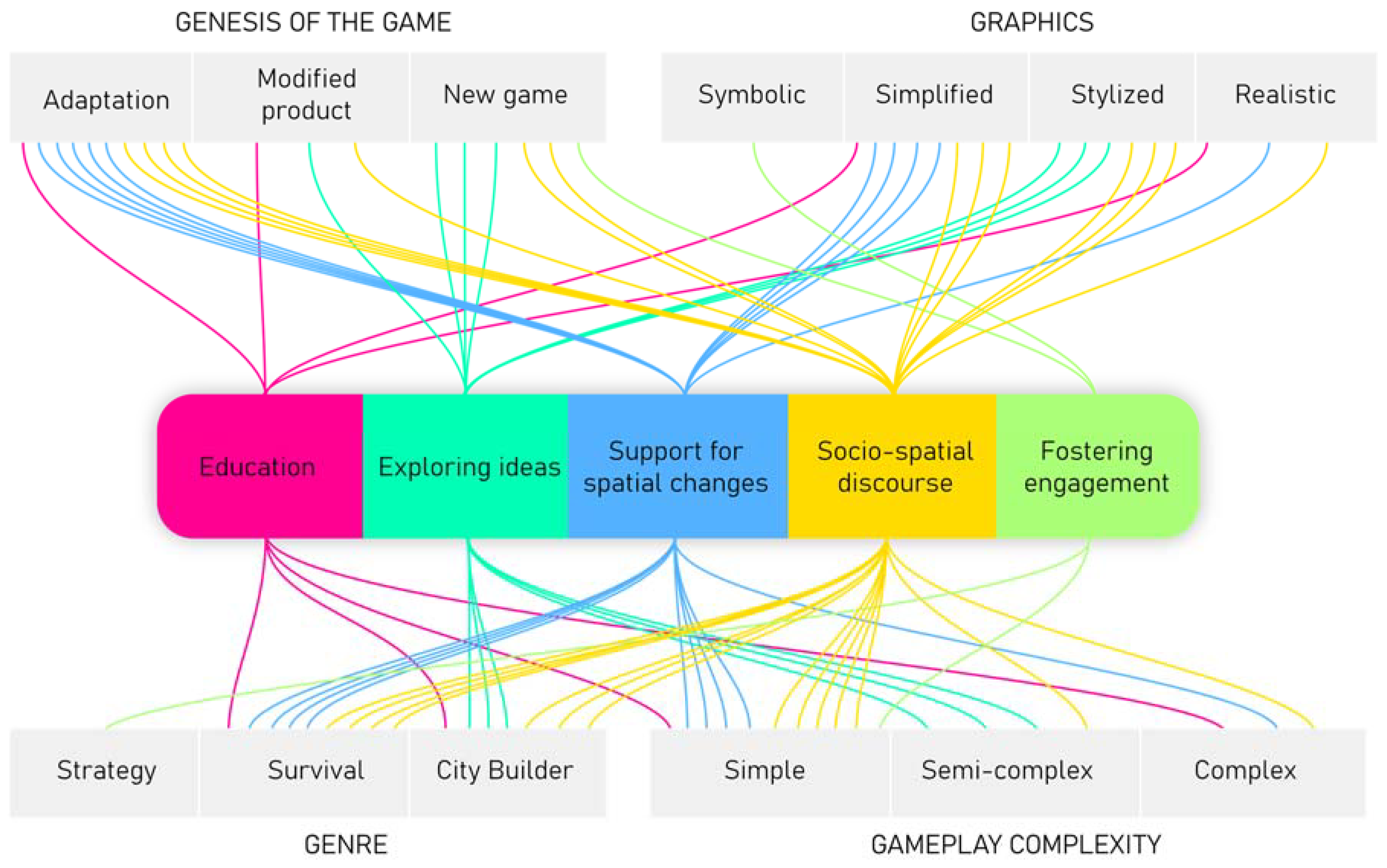

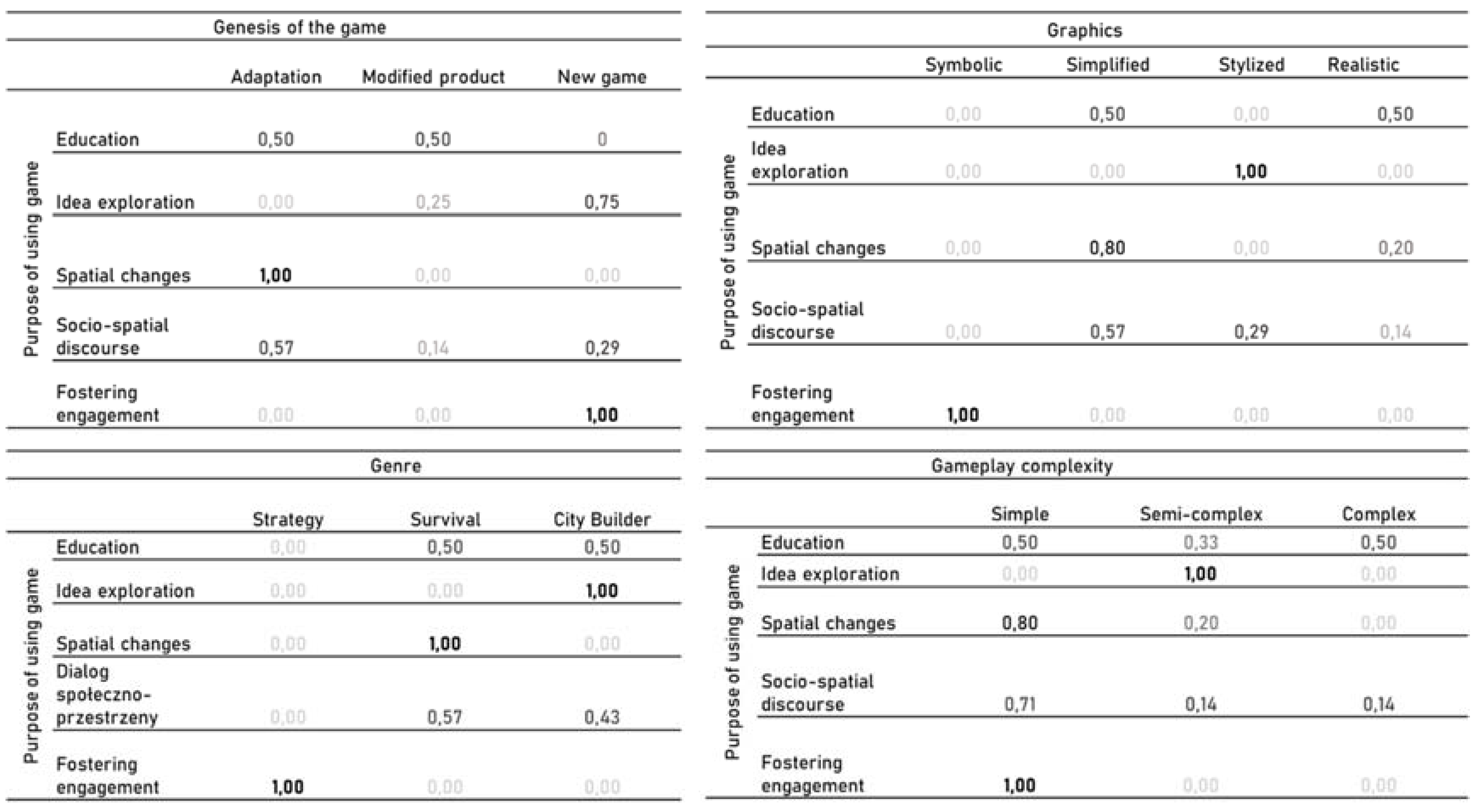

- Purpose of using a video game – reason why the video game was used – ex. social discourse, need for spatial changes, etc.

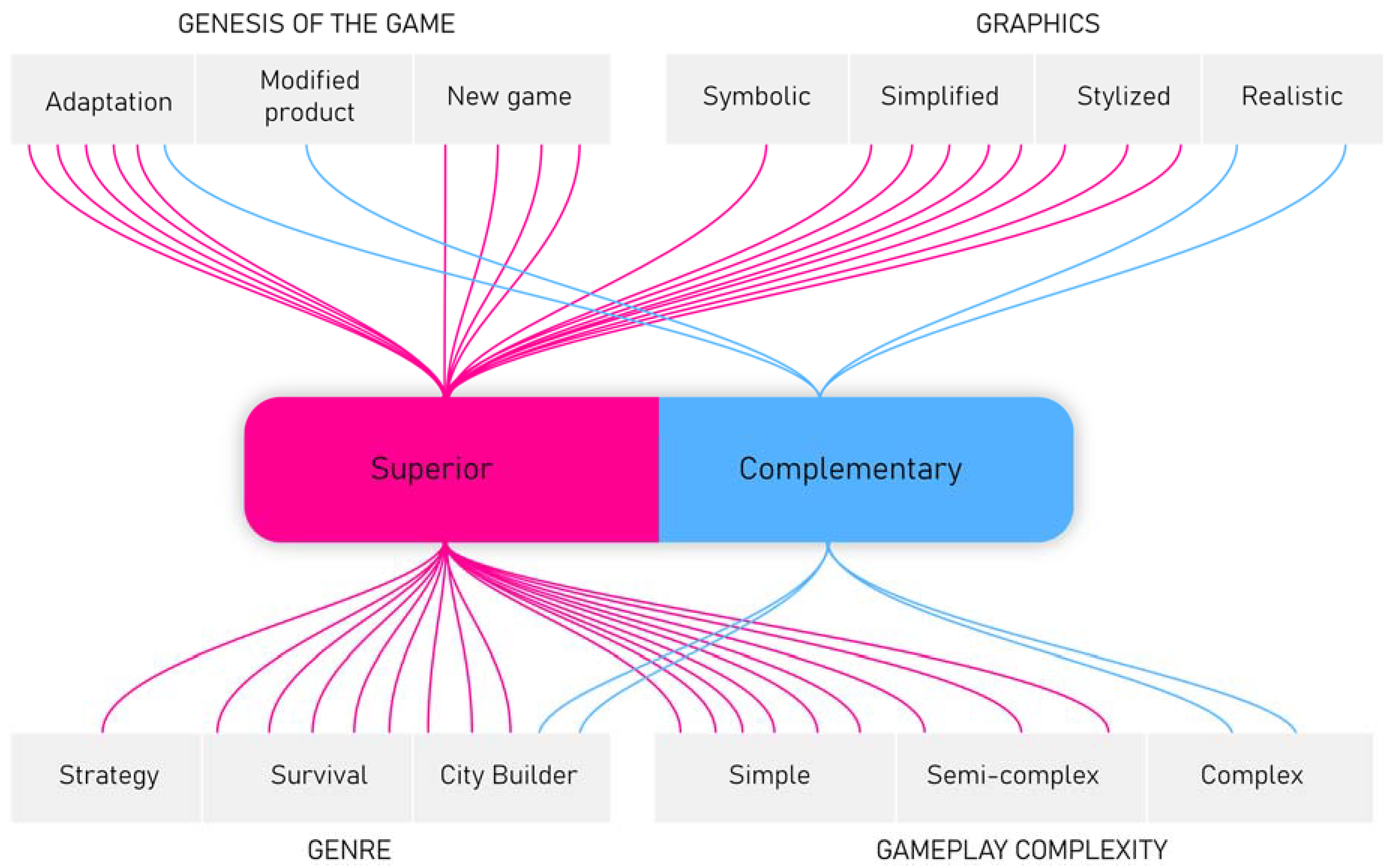

- Role of the game within the process - superior or complementary.

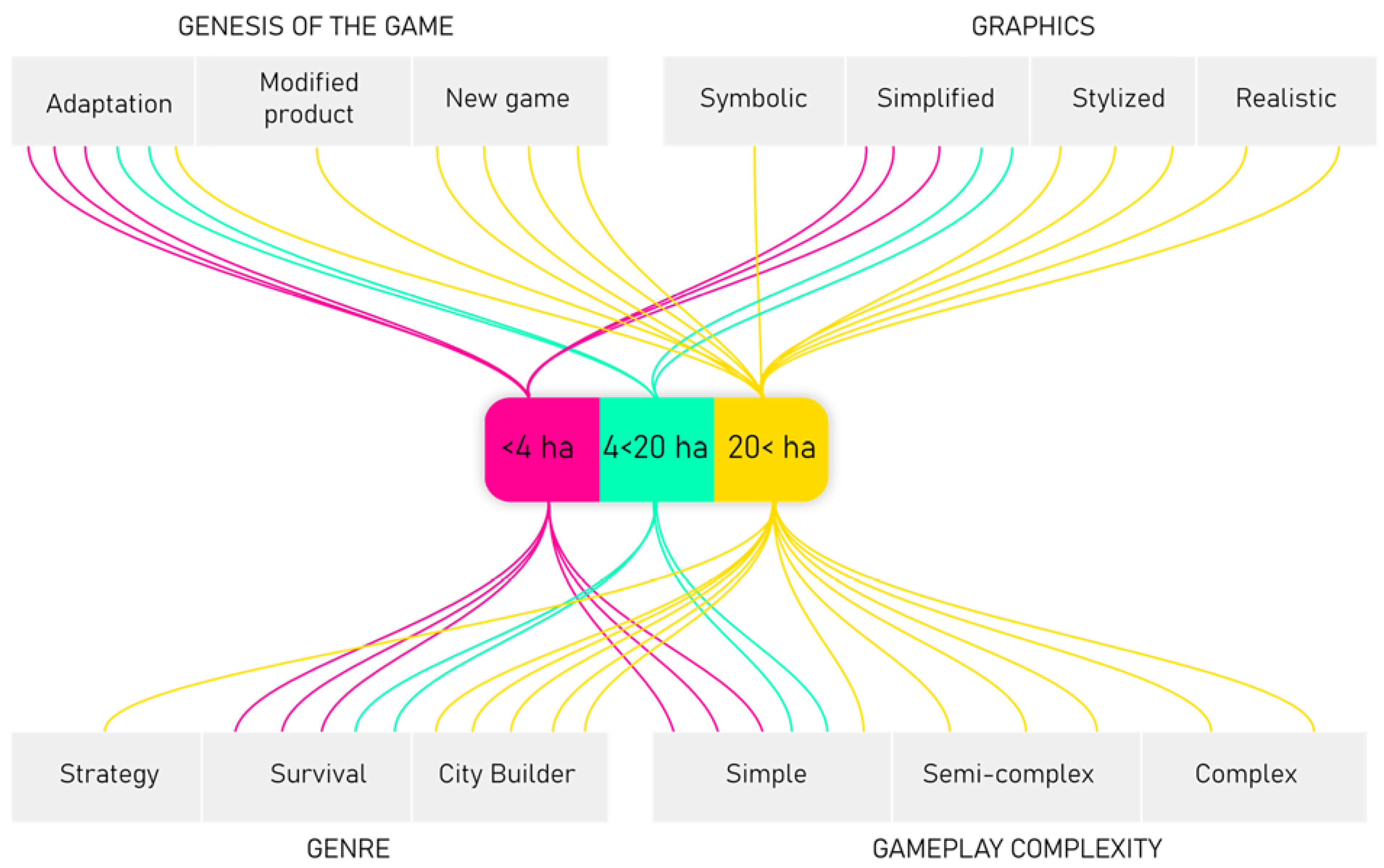

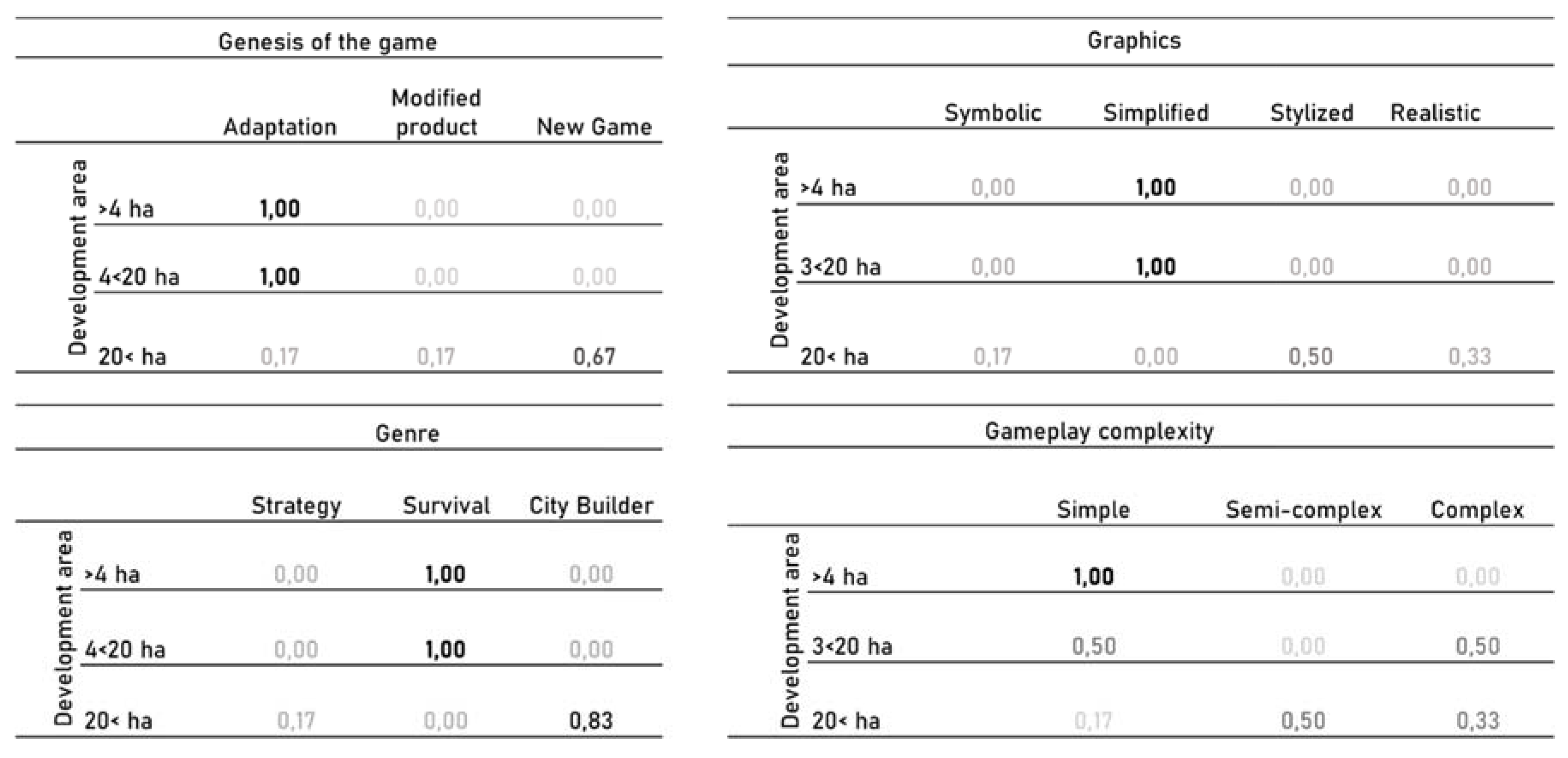

- Genesis – describes where the game comes from to the process whether it is an adaptation of a ready-made product, its modified version, or an entirely new game tailored for the process.

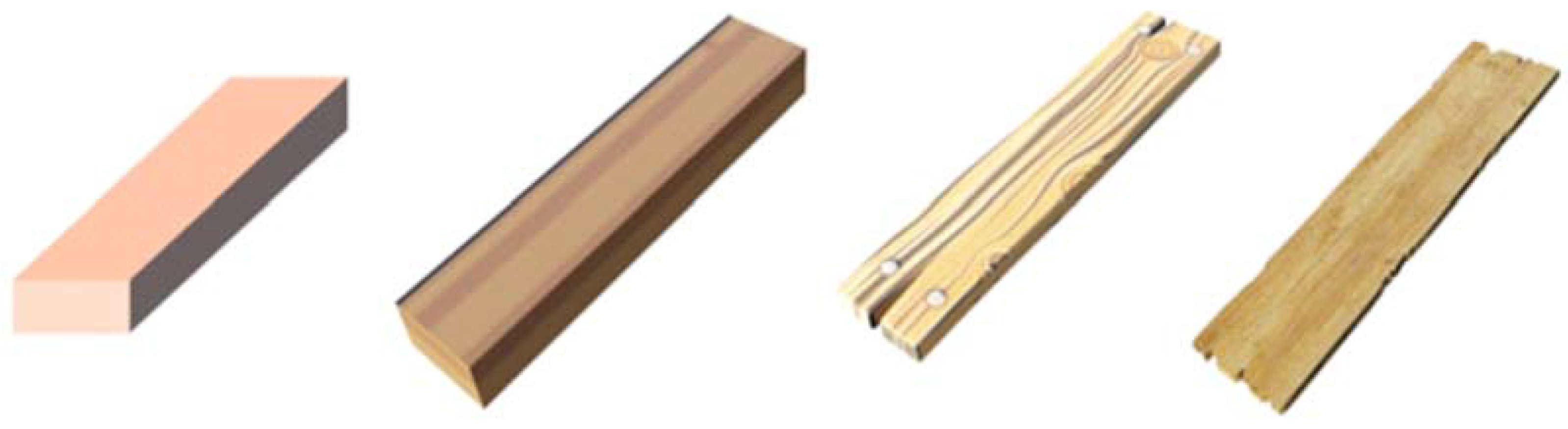

- Graphic style – this characteristic may be considered as the Level Of Detail of presented content with four possible values: symbolic, simple, stylized, and realistic. References for these values are presented in the figure 2.

- Genre – a type of the game – strategy, city builder, etc.

- Gameplay complexity – level of real-world accuracy of presented content.

3.4. Developing the Tool

- wDpir - target indication value for the r-th given value of the p-th parameter D;

- wdkiDpir - indication value for the r-th given value of the p-th parameter D at the assumed value of the k-th parameter d;

- k - the number of determining parameters.

4. Results

4.1. Gathered Cases and Results for Determining Parameters

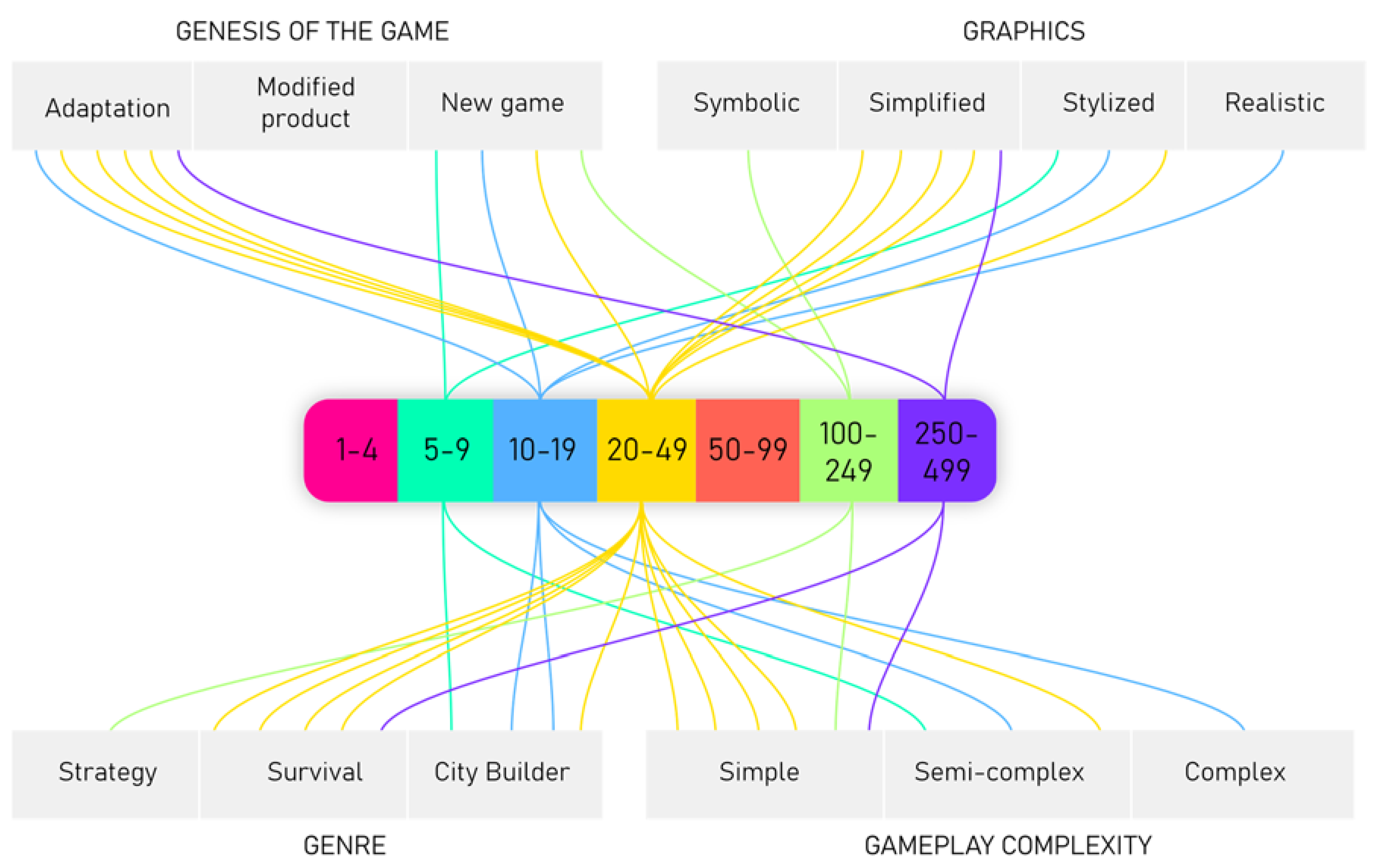

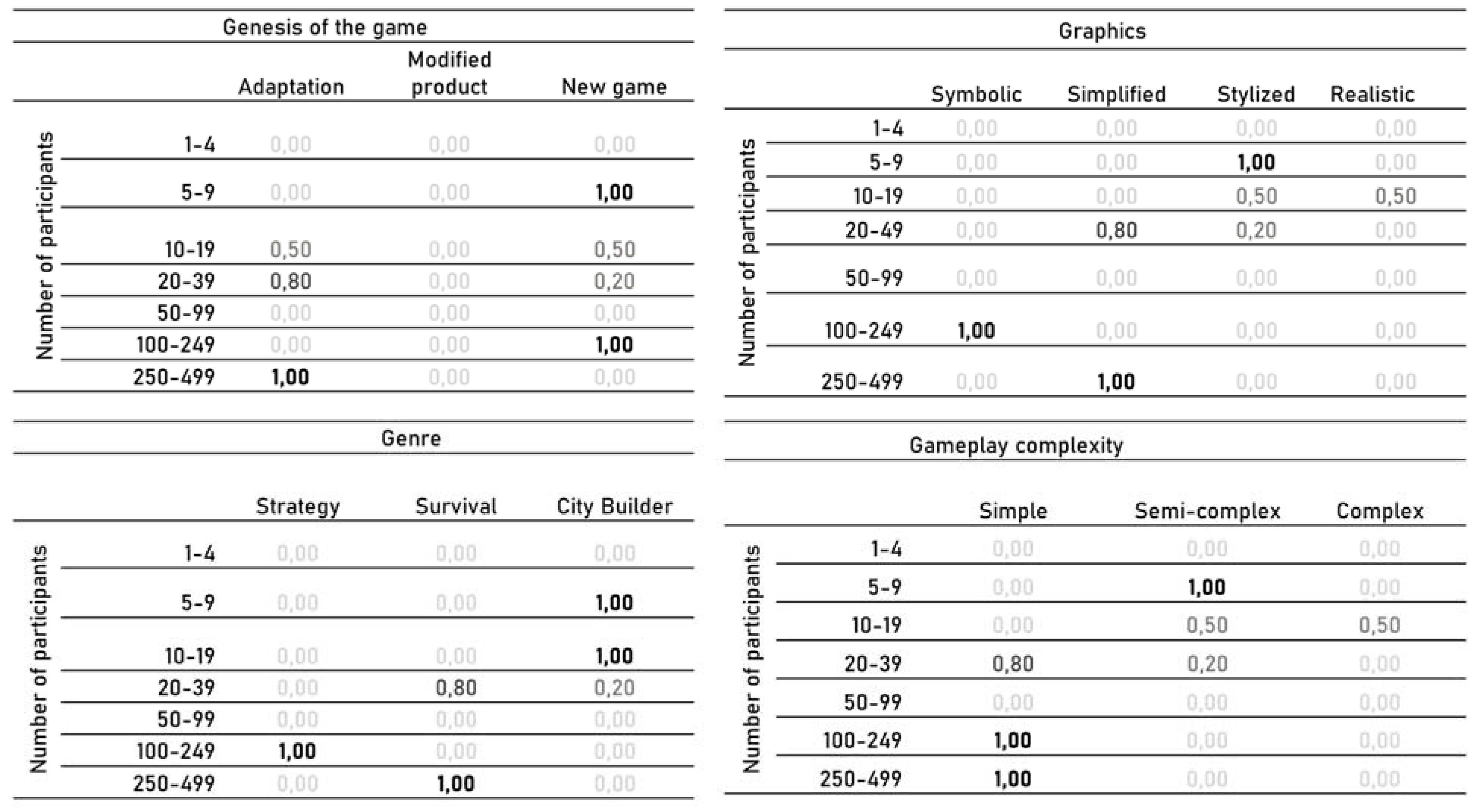

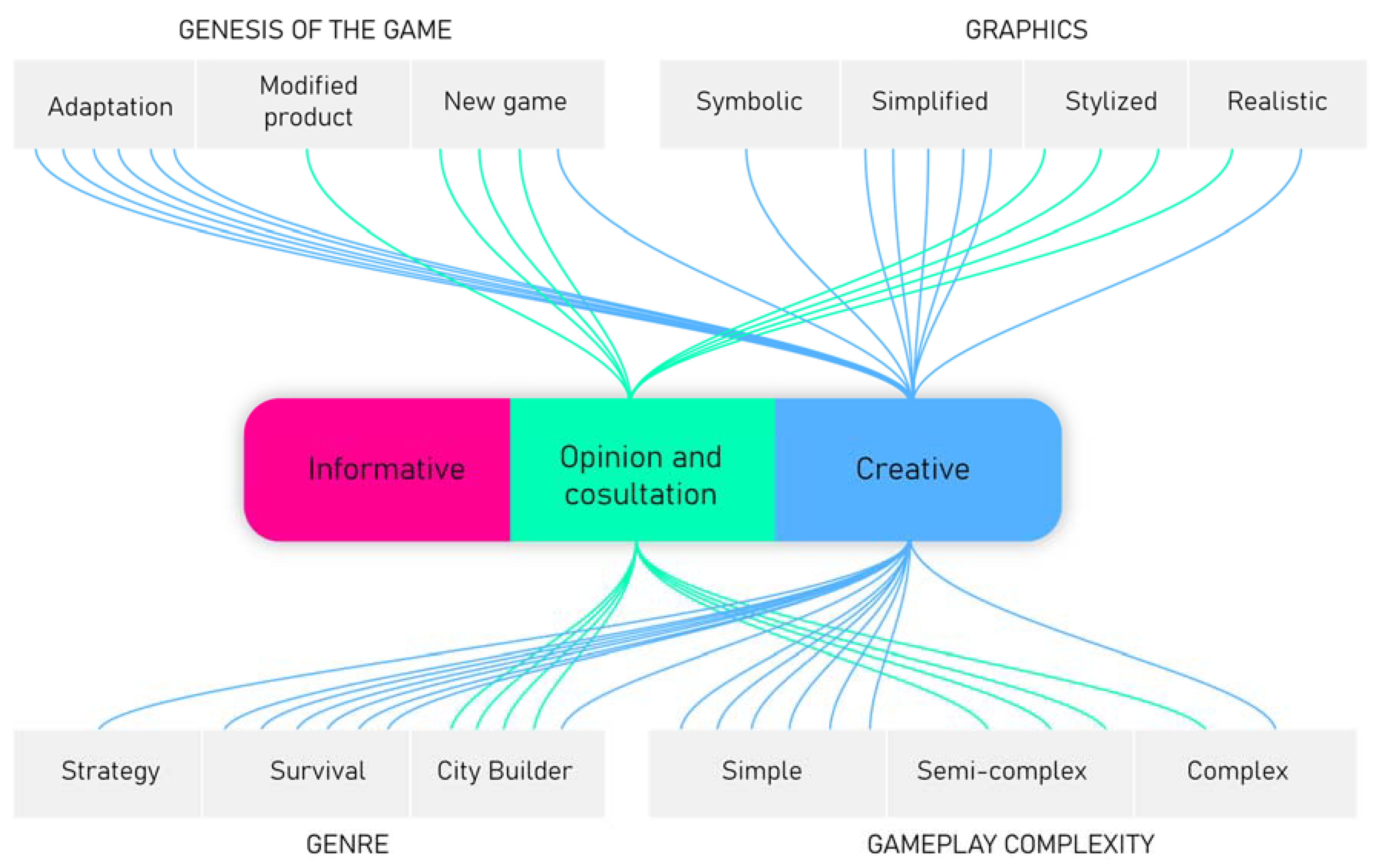

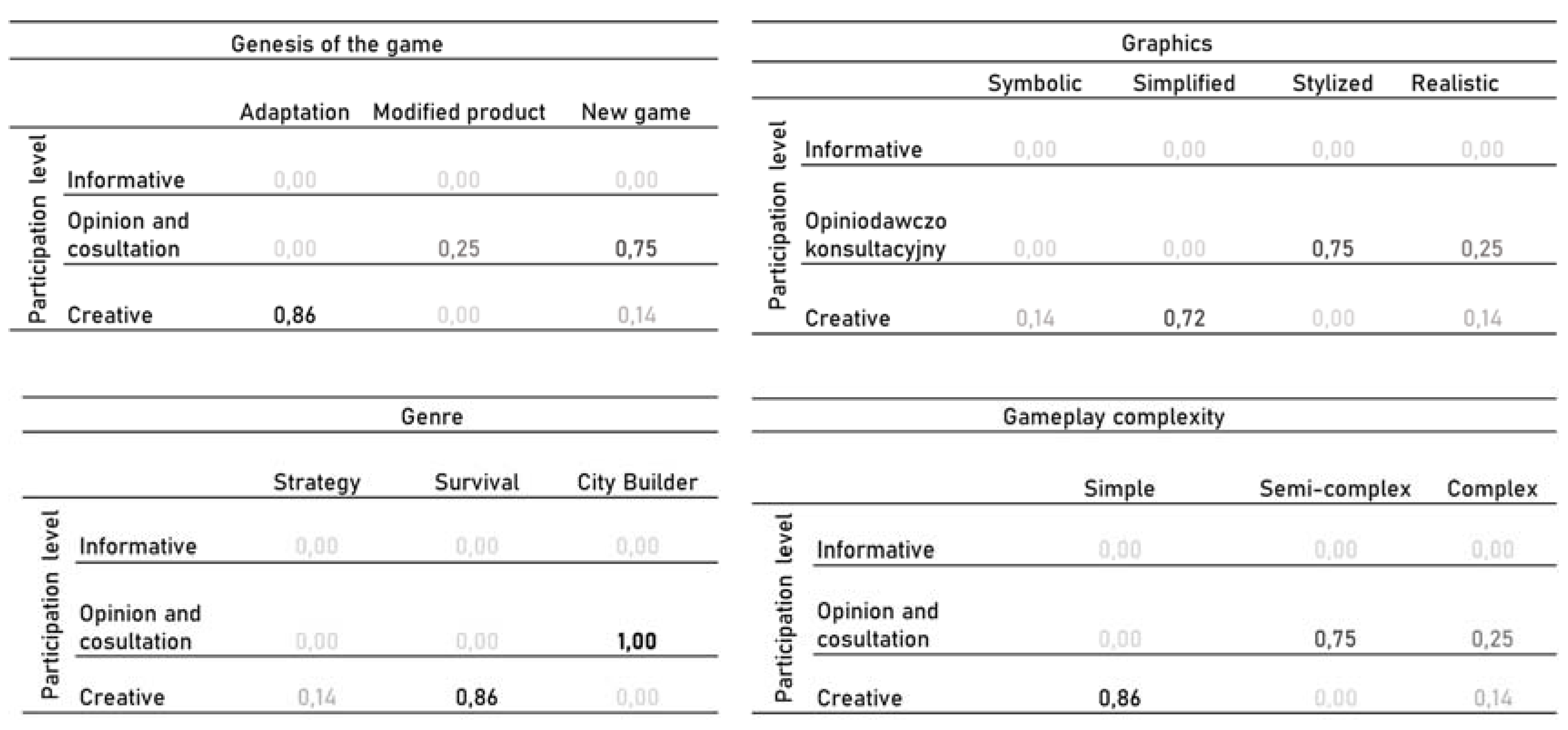

4.2. Summary of Calculated Values for Subsequent Determined Parameters

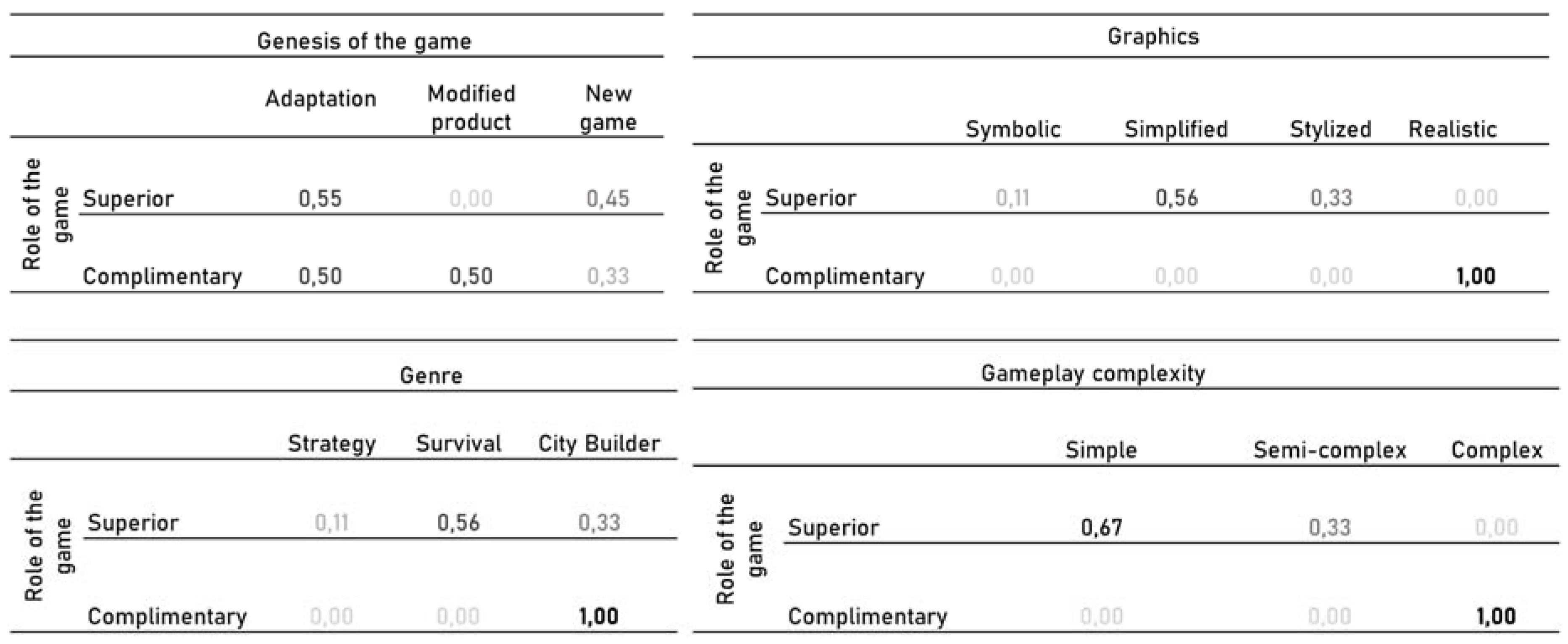

| Graphics | ||||||||||||

| Parameter | Symbolic | Simplified | Stylized | Realistic | ||||||||

| Area | none | up to 20 ha | 1,00 | 20+ ha | 0,50 | none | ||||||

| Type of space | none | Square, neighbourhood, park | 1,00 | District | 0,50 | none | ||||||

| Urban context | none | T2, T5, T6 | 1,00 | SN | 0,60 | SD | 1,00 | |||||

| T4 | 0,67 | |||||||||||

| Number of participants | 100-249 | 1,00 | 250+ | 1,00 | 5-9 | 1,00 | 10-19 | 0,50 | ||||

| 20-49 | 0,80 | 10-19 | 0,50 | |||||||||

| Age groups | none | Seniors | 1,00 | Adult | 0,50 | none | ||||||

| Children | 0,75 | |||||||||||

| Youth | 0,57 | |||||||||||

| Adult | 0,50 | |||||||||||

| Process accessibility | Semi-closed | 0,50 | Closed | 1,00 | Semi-open | 0,50 | Open | 0,50 | ||||

| Semi-closed, Open | 0,50 | |||||||||||

| Process mode | Mobile | 1,00 | On site | 0,56 | none | Remote | 1,00 | |||||

| Participation level | none | Creative | 0,72 | Opinion and consultation | 0,75 | none | ||||||

| Purpose of using game | Fostering engagement | 1,00 | Spatial changes | 0,80 | Idea exploration | 1,00 | Education | 0,50 | ||||

| Socio-spatial discourse | 0,57 | |||||||||||

| Education | 0,50 | |||||||||||

| Role of the game | none | Superior | 0,56 | none | Complimentary | 1,00 | ||||||

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Please specify the location for which videogames were used during planning process. (Country, City, District<if applicable>)

- Please specify the time(years) of the process - from decision of taking videogames for account to realisation/change implementation/any other expected outcome that at least partially finalized the process.

- Please specify the area of developed space (if any) [w/ unit]

- Please indicate the type of space considered in the process (street, square, park, district, etc)

- Please specify urban context of developed space.

- a.

- Rural

- b.

- Downtown

- c.

- Brownfield

- d.

- Blocks

- e.

- Other

- 6.

- Please indicate age groups of the participants. Last answer is for additional

- 7.

- notes about this aspect.

- a.

- 15<

- b.

- 15<20

- c.

- 20<30

- d.

- 30<45

- e.

- 45<60

- f.

- 60<

- 8.

- Please specify openness of the process

- a.

- Closed - only requested participants

- b.

- Semi closed - open participation included but with priority of requested participants

- c.

- Semi-open - open participation but with limits (amount of participants, level of their priority)

- d.

- Full open participation - anyone could participate

- 9.

- What level of participation was assumed for the planning process?

- a.

- Only informing the public about planning actions

- b.

- Justification of the planning actions taken

- c.

- Enabling opinions on presented plans

- d.

- Enabling suggestions and changes to presented plans

- e.

- Enabling participants to present own ideas for consideration

- f.

- Participants as main source of ideas and planning assumptions

- 10.

- Please specify groups and organizations involved in the process and indicate their roles.

- 11.

- What kind of game was used for the process?

- 12.

- Adapted game - no or insignificant dose of modifications (such as Minecraft)

- 13.

- Significantly modified game (ex. Cities Skylines with mods)

- 14.

- Entirely new game crafted for this specific purpose

- 15.

- Gamified digital system (ex. GIS with gamified elements)

- 16.

- What was the purpose of using the game - visualization, spatial expression, consensus building, education etc.?

- 17.

- Please characterize main aspects of the game - was it mobile app, online game, geo-game, was it hybrid mix of digital game and some real-life artifacts?

- 18.

- What was the position of the videogame in the proses (core, supplementary, complementary)?

- 19.

- Was the process included any additional activities ex. urban planning workshops, game introduction, group survey walks.

- 20.

- Do You consider the case successful? Successful may be defined as fully realized project without any major changes in the process and assumptions. It also takes into account satisfaction of all participants. Any conclusions are welcome as well.

Appendix B

- Area of developed space.

- 2.

- Type of developed space.

- 3.

- Urban context.

- 4.

- Number of participants.

- 5.

- Number of particiapnts

- 6.

- Process accessibility

- 7.

- Mode of the process

- 8.

- Participation level

- 9.

- Purpose of using the game

References

- Poplin, A. Digital Serious Game for Urban Planning: “B3—Design Your Marketplace!” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 2014, 41, 493–511. [CrossRef]

- Di Mascio, D.; Dalton, R. Using Serious Games to Establish a Dialogue Between Designers and Citizens in Participatory Design. In Serious Games and Edutainment Applications : Volume II; Ma, M., Oikonomou, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 433–454. ISBN 978-3-319-51645-5. [CrossRef]

- O’Coill, C.; Doughty, M. Computer Game Technology as a Tool for Participatory Design. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Education and Research in Computer Aided Architectural Design in Europe (eCAADe); eCAADe: Kopenhaga, 2004; pp. 12–23.

- Poplin, A.; Vemuri, K. Spatial Game for Negotiations and Consensus Building in Urban Planning: YouPlaceIt! In Geogames and Geoplay: Game-based Approaches to the Analysis of Geo-Information; Ahlqvist, O., Schlieder, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 63–90 . ISBN 978-3-319-22774-0. [CrossRef]

- Beattie, H.; Brown, D.; Kindon, S. Solidarity through difference: Speculative participatory serious urban gaming (SPS-UG). International Journal of Architectural Computing 2020, 18, 141–154. [CrossRef]

- Kavouras, I.; Sardis, E.; Protopapadakis, E.; Rallis, I.; Doulamis, A.; Doulamis, N. A Low-Cost Gamified Urban Planning Methodology Enhanced with Co-Creation and Participatory Approaches. Sustainability 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- e Andrade, B.; Poplin, A.; Sousa de Sena, Í. Minecraft as a Tool for Engaging Children in Urban Planning: A Case Study in Tirol Town, Brazil. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J. Architecture for the Commons: Participatory Systems in the Age of Platforms; Taylor & Francis, 2020; ISBN 978-0-429-77801-8.

- Delaney, J. Minecraft and Playful Public Participation in Urban Design. Urban Planning 2022, 7, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westenberg, P.; von Heland, F. Using Minecraft for Youth Participation in Urban Design and Governance; UN Habitat: online, 2015.

- Hämäläinen, T. Instagram ja Cities Skylines herättelevät nuoria keskustelemaan kaupunkisuunnittelusta [Instagram oraz Cities Skylines wywołuje rozmowę o planowaniu urbanistycznym wśród młodych ludzi]. mdi.fi 2016.

- Krisman, V. “Cities: Skylines” Being Used By Stockholm City Planners. intelligentcommunity.org 2016.

- Prandi, C.; Roccetti, M.; Salomoni, P.; Nisi, V.; Nunes, N.J. Fighting exclusion: a multimedia mobile app with zombies and maps as a medium for civic engagement and design. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2017, 76, 4951–4979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulstick, B. Entrepreneurial Game Studio to Launch SIM-PHL, an Urban Planning Simulator Game Powered by Philadelphia’s Open Data. drexel.edu 2020.

- Prilenska, V. Current Research Trends in Games for Public Participation in Planning. Architecture and Urban Planning 2019, 15, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.; Tewdwr-Jones, M.; Comber, R. Urban planning, public participation and digital technology: App development as a method of generating citizen involvement in local planning processes. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 2019, 46, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewski, R.; Turek, A.; Laczynski, M. Urban Gamification as a Source of Information for Spatial Data Analysis and Predictive Participatory Modelling of a City’s Development. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Data Technologies and Applications; Francalanci, C., Helfert, M., Eds.; ScitePress: Colmar Francja, 2016; Vol. 1, pp. 176–181.

- Olszewski, R.; Turek, A. The Mordor Shaper—The Warsaw Participatory Experiment Using Gamification. In Proceedings of the ICT Systems and Sustainability; Tuba, M., Akashe, S., Joshi, A., Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2020; pp. 255–264.

- UN, G.A. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015 70/1. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development 2015.

- Mather, L.W.; Robinson, P.J. Durable Civic Technology. In Citizen-Responsive Urban E-Planning; Nunes Silva, C., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, 2020; pp. 252–281.

- Brooks, L. The Design and Development of Serious Games.; Victoria, Kanda, 2018; pp. 1–8.

- Cravero, S. Methods, strategies and tools to improve citizens’ engagement in the smart cities’ context: A Serious Game classification. Valori e Valutazioni 2020, 2020, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Devisch, O.; Gugerell, K.; Diephuis, J.; Constantinescu, T.; Ampatzidou, C.; Jauschneg, M. Mini is beautiful : Playing serious mini-games to facilitate collective learning on complex urban processes. Interaction Design and Architecture(s) 2017, 141–157.

- Toth, E. Potential of Games in the Field of Urban Planning. In Proceedings of the New Perspectives in Game Studies: Proceedings of the Central and Eastern European Game Studies Conference Brno 2014; Bártek, T., Miškov, J., Švelch, J., Eds.; Munipress: Brno, 2015; pp. 71–89.

- Poplin, A. Playful public participation in urban planning: A case study for online serious games. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 2012, 36, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, L.; Hamari, J. Gameful civic engagement: A review of the literature on gamification of e-participation. Government Information Quarterly 2020, 37, 101461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampatzidou, C.; Gugerell, K.; Constantinescu, T.; Devisch, O.; Jauschneg, M.; Berger, M. All Work and No Play? Facilitating Serious Games and Gamified Applications in Participatory Urban Planning and Governance. Urban Planning 2018, 3, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, A.; Westenberg, P. The Block By Block Playbook Using Minecraft as a Participatory Design Tool in Urban Design And Governance; UN Habitat: online, 2021.

- Westenberg, P.; Rana, S. Using Minecraft for Community Participation; UN Habitat: online, 2016.

- Guo Xiang, O. Participatory Design Games in Urban Planning: Towards a Distributed and Massively Multi-player Online Collaboration Model. Master thesis, National University of Singapore: Singapur, 2016.

- Arnstein, S. A ladder of social participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners 1969, 4, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, S.-K.; Lehner, U. Exploring the Effects of Game Elements in M-Participation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2015 British HCI Conference; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 65–73. [CrossRef]

- Maaß, J. Serious Games in Sustainable Land Management. In Sustainable Land Management in a European Context: A Co-Design Approach; Weith, T., Barkmann, T., Gaasch, N., Rogga, S., Strauß, C., Zscheischler, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 185–205. ISBN 978-3-030-50841-8. [CrossRef]

| Dp | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dk | i1 | i2 | ir | |

| i1 | wdki1Dpi1 | wdki1Dpi2 | wdki1Dpir | |

| i2 | wdki2Dpi1 | wdki2Dpi2 | wdki2Dpir | |

| il | wdkl1Dpi1 | wdkilDpi2 | wdki1lDpir | |

| Dp | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| i1 | i2 | ir | |

| d1 | d1i; wdki1Dpi1 | d1i; wdki1Dpi2 | d1i; wdki1Dpir |

| d2 | d2i; wdki2Dpi1 | d2i; wdki2Dpi2 | d2i; wdki2Dpir |

| d3 | d3i; wdkl1Dpi1 | d3i; wdkilDpi2 | d3i; wdki1lDpir |

| Case | Game | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Block By Block Nairobi Block By Block Les Cayes Block By Block Mexico City Block By Block Kirtipur |

Minecraft | 2013 |

| Minecraft | 2014 | |

| Minecraft | 2014 | |

| Minecraft | 2014 | |

| Stockholm Royal Seaport | Cities: Skylines | 2016 |

| Hameenlinna, Kantola | Cities: Skylines | 2016 |

| Tirolcraft, Tirol | Minecraft | 2016 |

| New Delhi, Ghazipur | Maslows Palace | 2017 |

| New Delhi, Bhalswa | Maslows Palace | 2017 |

| Mumbai, Shivanji Nagar | Maslows Palace | 2017 |

| Warsaw, Mokotów | Mordor Shaper | 2018-2019 |

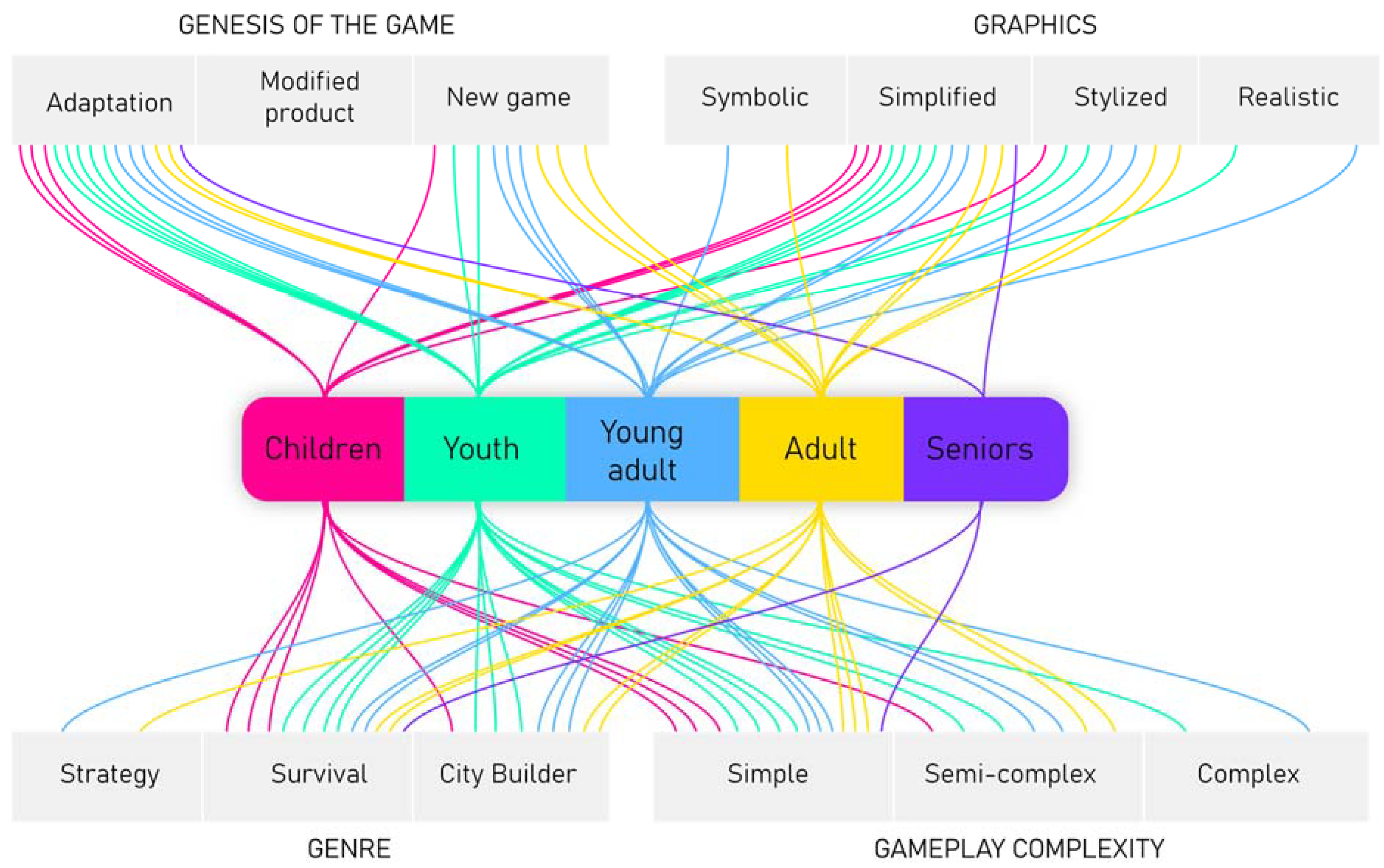

| Parameter | Genesis of the game | |||||||

| Adaptation | Modified product | New game | ||||||

| Area | up to 20 ha | 1,00 | none | over 20 ha | 0,83 | |||

| Type of space | neighborhood, square, park | 1,00 | none | District | 0,67 | |||

| Urban context | T2, T5, T6, SD | 1,00 | none | SN | 0,60 | |||

| Number of participants | 250+ | 1,00 | none | 5-9; 100-249 | 1,00 | |||

| 20-39 | 0,80 | none | ||||||

| Age groups | Seniors | 1,00 | none | Adults | 0,60 | |||

| Children | 0,75 | |||||||

| Youth | 0,71 | Young adults | 0,50 | |||||

| Young adults | 0,50 | |||||||

| Process accessibility | Closed, Open | 1,00 | none | Semi-closed, Semi-open | 0,50 | |||

| Semi-closed | 0,50 | |||||||

| Process mode | Remote | 1,00 | none | Mobile | 1,00 | |||

| On site | 0,56 | |||||||

| Participation level | Creative | 0,86 | none | Opinion and cosultation | 0,75 | |||

| Purpose of using game | Spatial changes | 1,00 | none | Fostering engagement | 1,00 | |||

| Socio-spatial discourse | 0,57 | Idea exploration | 0,75 | |||||

| Role of the game | Superior | 0,55 | Complimentary | 0,50 | none | |||

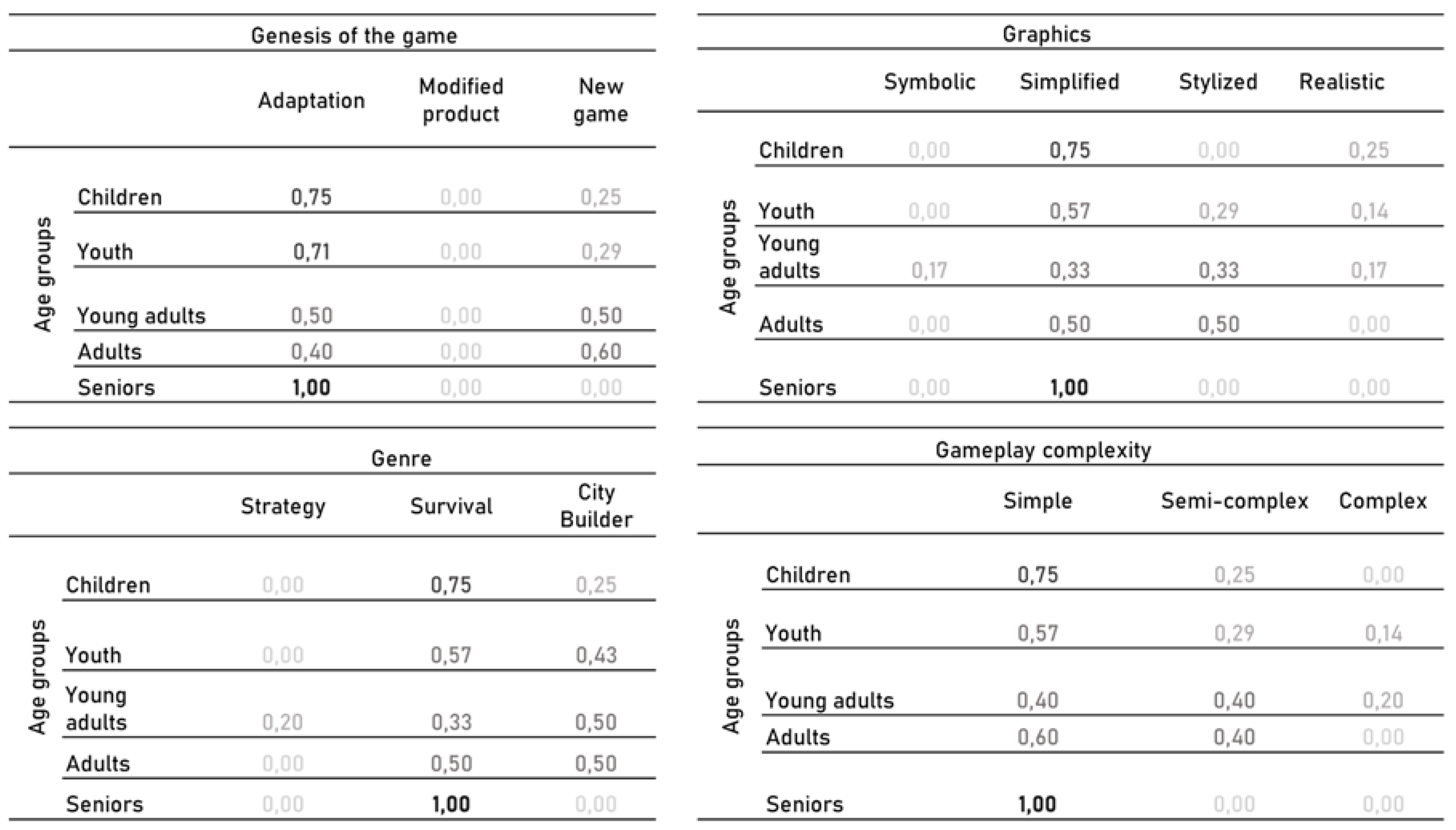

| Genre | ||||||

| Parameter | Strategy | Survival | City builder | |||

| Area | none | up to 20 ha | 1,00 | over 20 ha | 0,83 | |

| Type of space | none | Square, park, neighborhood | 1,00 | District | 0,83 | |

| Urban context | none | T2, T5, T6 | 1,00 | SD | 1,00 | |

| T4 | 0,67 | |||||

| Number of participants | 100-249 | 1,00 | over 250 | 1,00 | up to 19 | 1,00 |

| 20-49 | 0,80 | |||||

| Age groups | none | Seniors | 1,00 | Young adults, adults | 0,50 | |

| Children | 0,75 | |||||

| Youth | 0,57 | |||||

| Adult | 0,50 | |||||

| Process accessibility | Semi-closed | 0,50 | Closed | 1,00 | Semi-open | 0,67 |

| Semi-closed, open | 0,50 | Open | 0,50 | |||

| Process mode | Mobile | 1,00 | On site | 0,56 | Remote | 1,00 |

| Participation level | none | Creative | 0,86 | Opinion and consultation | 1,00 | |

| Purpose of using game | Fostering engagement | 1,00 | Spatial changes | 1,00 | Idea exploration | 1,00 |

| Socio-spatial discourse | 0,57 | Education | 0,50 | |||

| Education | 0,50 | |||||

| Role of the game | none | Superior | 0,56 | Complimentary | 1,00 | |

| Gameplay complexity | ||||||

| Parameter | Simple | Semi-complex | Complex | |||

| Area | up to 4 ha | 1,00 | over 20 ha | 0,50 | 4-20 ha | 0,50 |

| 4-20 ha | 0,50 | |||||

| Type of space | Square, neighborhood, park | 1,00 | District | 0,50 | none | |

| Urban context | T2, T5, T6 | 0,60 | SN | 0,60 | SD | 1,00 |

| T4 | 0,67 | |||||

| Number of participants | over 100 | 1,00 | 5-9 | 1,00 | 10-19 | 0,50 |

| 20-49 | 0,80 | 10-19 | 0,50 | |||

| Age groups | Seniors | 1,00 | none | none | ||

| Children | 0,75 | |||||

| Adults | 0,60 | |||||

| Youth | 0,57 | |||||

| Process accessibility | Closed, semi-closed | 1,00 | Semi-open | 0,50 | Open | 0,50 |

| Open | 0,50 | |||||

| Process mode | Mobile | 1,00 | none | Remote | 1,00 | |

| On site | 0,55 | |||||

| Participation level | Creative | 0,86 | Opinion and consultation | 0,75 | none | |

| Purpose of using game | Fostering engagement | 1,00 | Idea exploration | 1,00 | Education | 0,50 |

| Spatial changes | 0,80 | |||||

| Socio-spatial discourse | 0,71 | |||||

| Education | 0,50 | |||||

| Role of the game | Superior | 0,67 | none | Complimentary | 1,00 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).