Submitted:

29 August 2024

Posted:

30 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

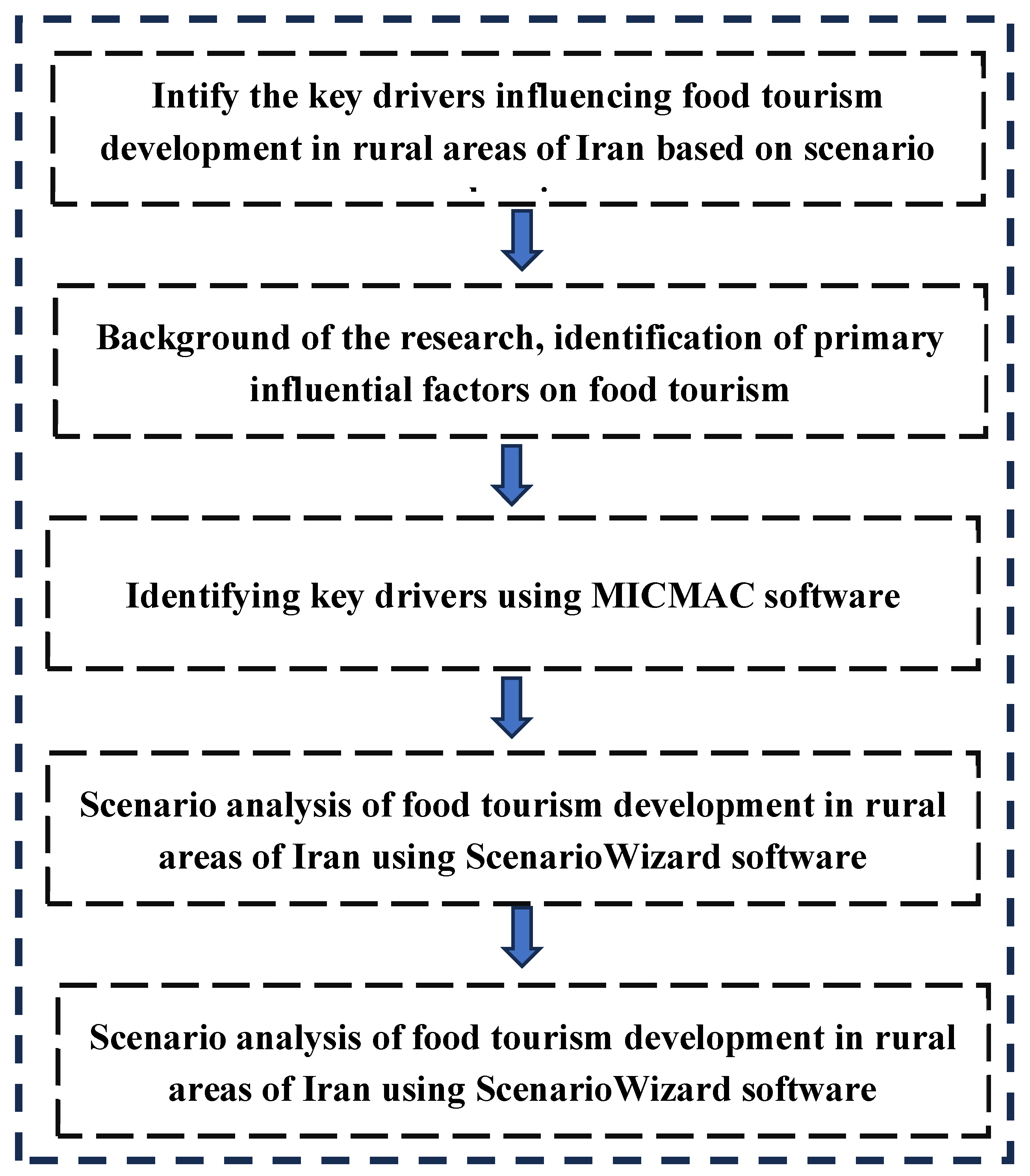

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Key Drivers Influencing Food Tourism in Rural Areas of Iran

3.1.1. Evaluation of the Impact and Influence of Factors Affecting the Development of Food Tourism in Rural Areas of Iran

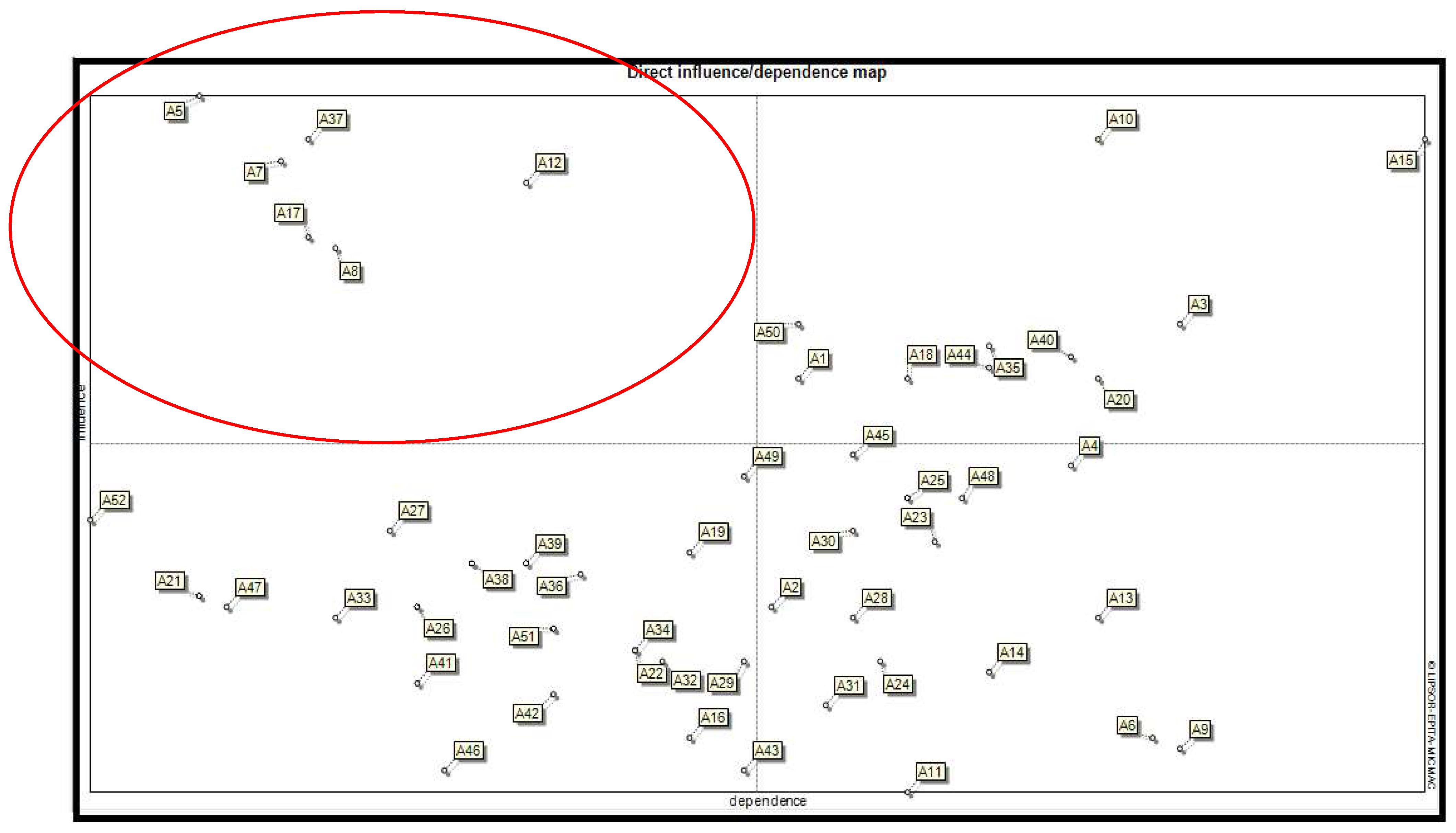

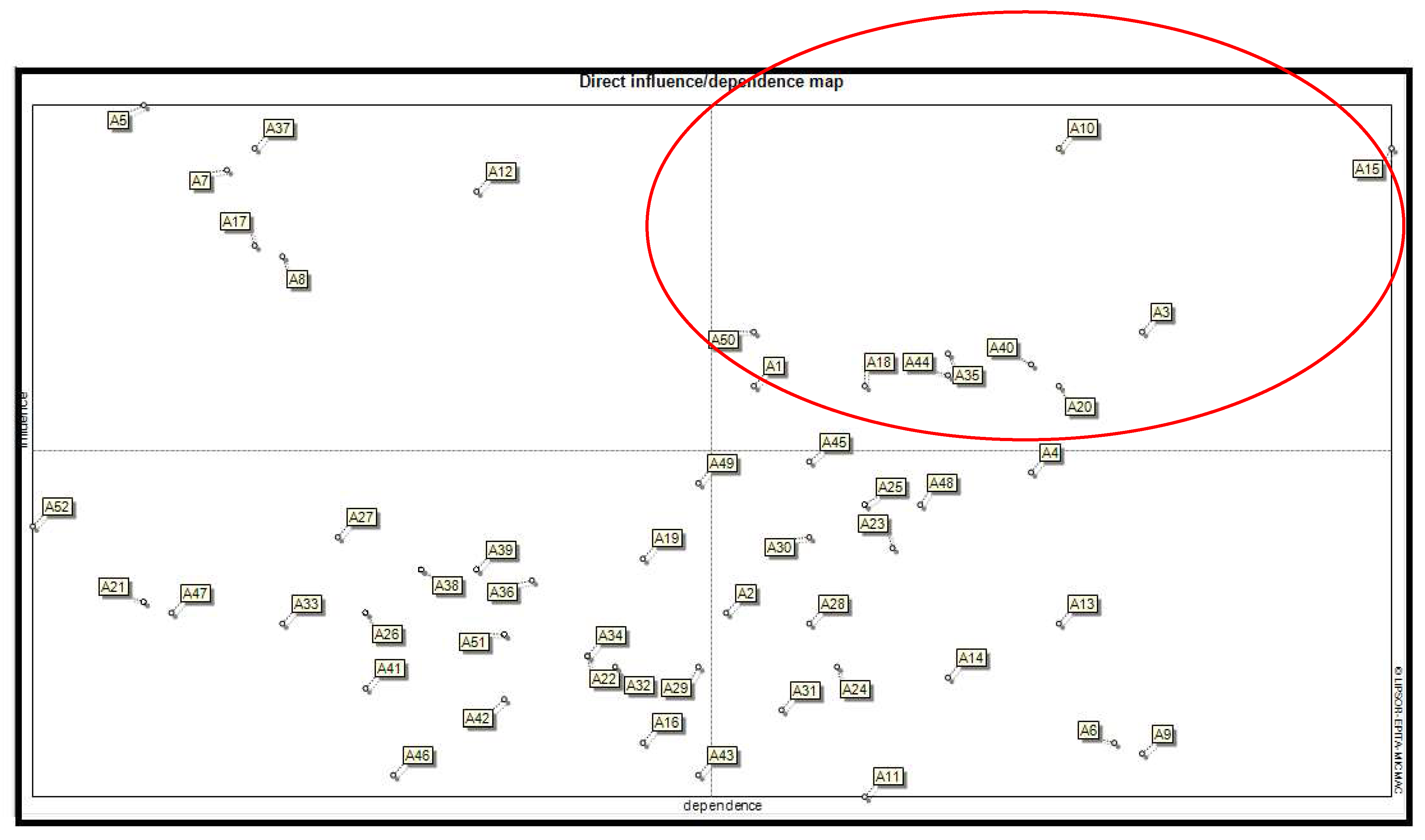

3.1.2. Factors Determining or Influencing the Development of Food Tourism in Rural Areas of Iran

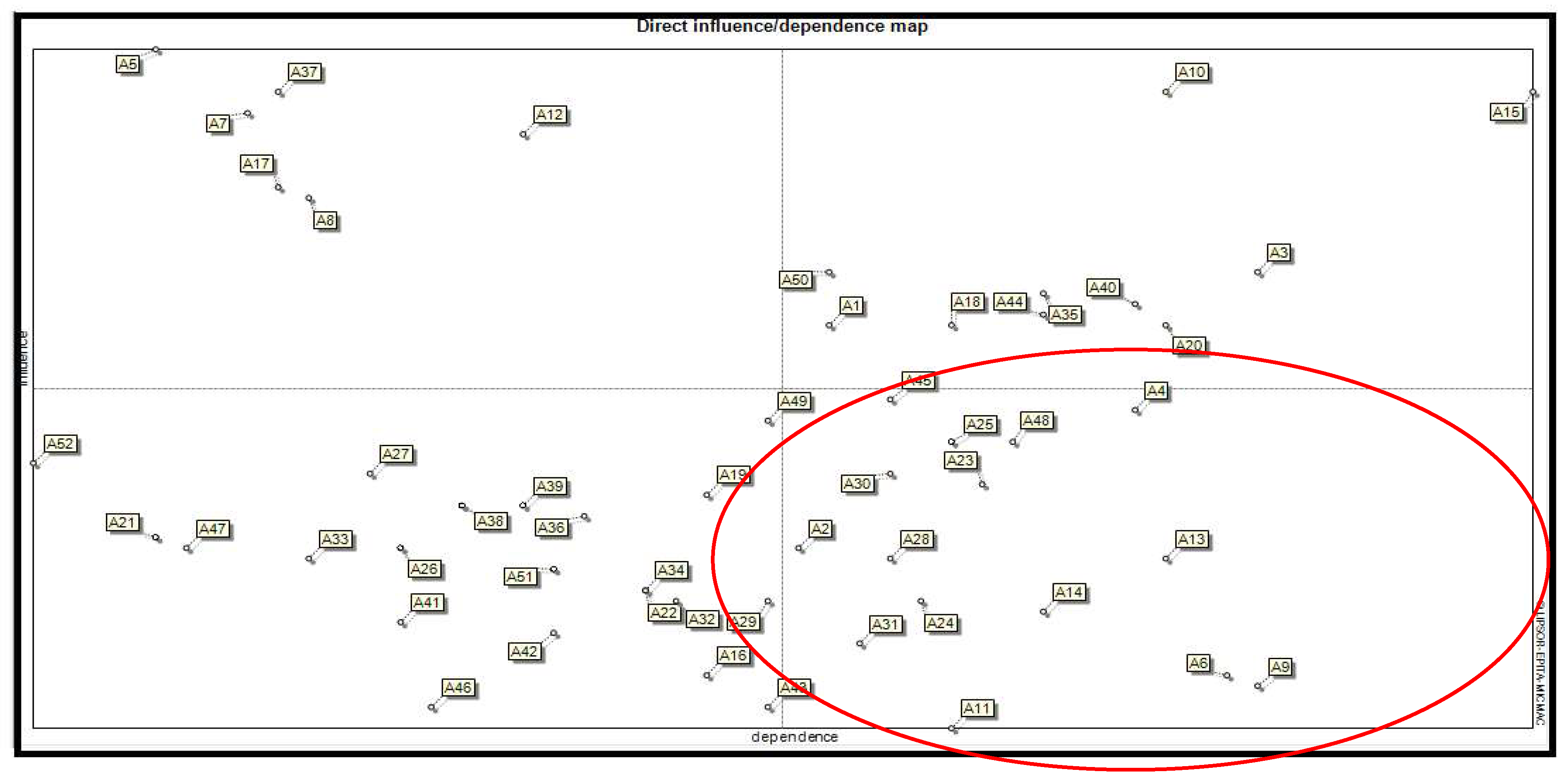

3.1.3. Dual-Purpose Factors (Risk Factors and Target Variables) of Food Tourism Development in Rural Areas of Iran

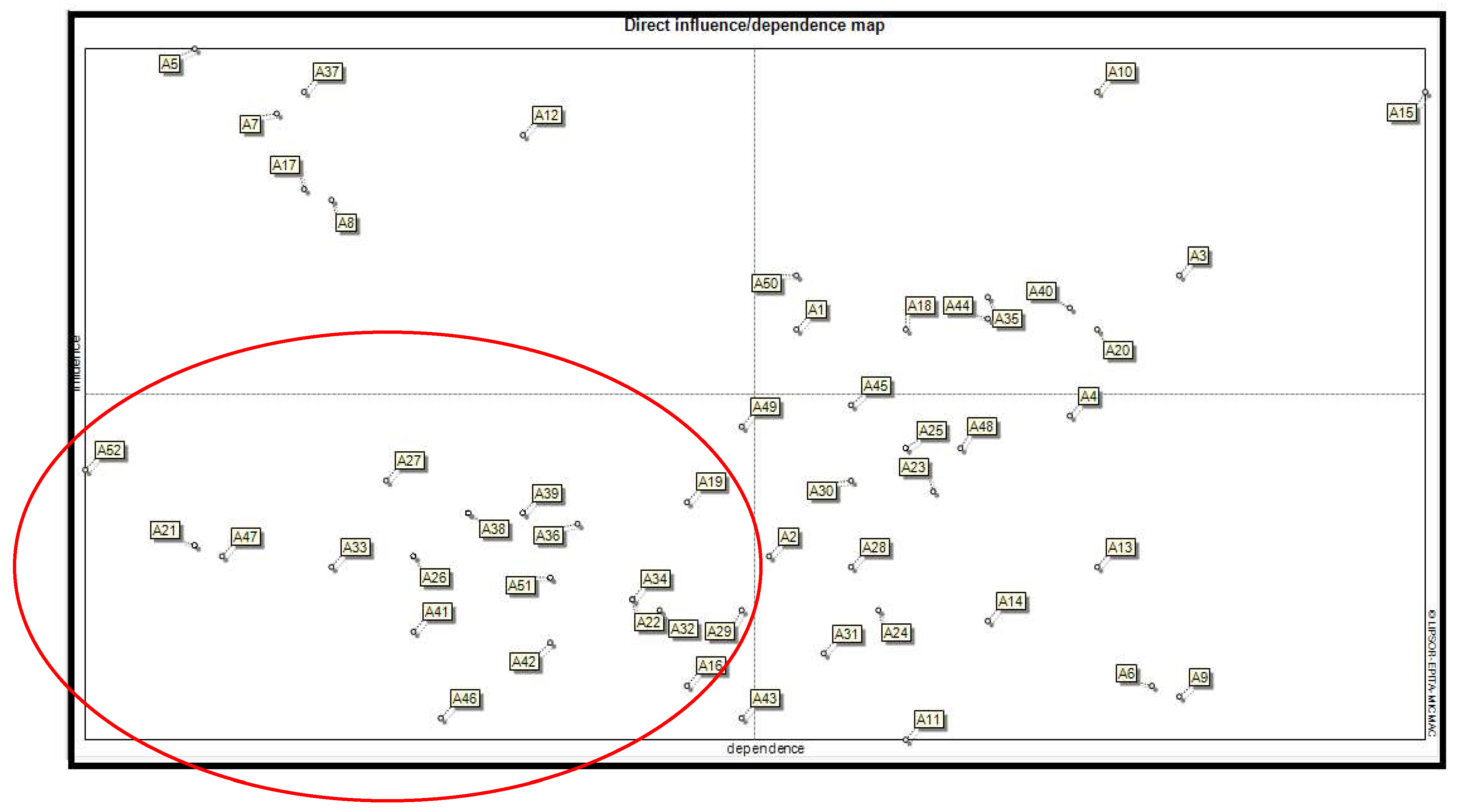

3.1.4. Influential Factors on Food Tourism Development in Rural Areas of Iran

3.1.5. Independent or Exceptional Factors in Food Tourism Development in Rural Areas of Iran

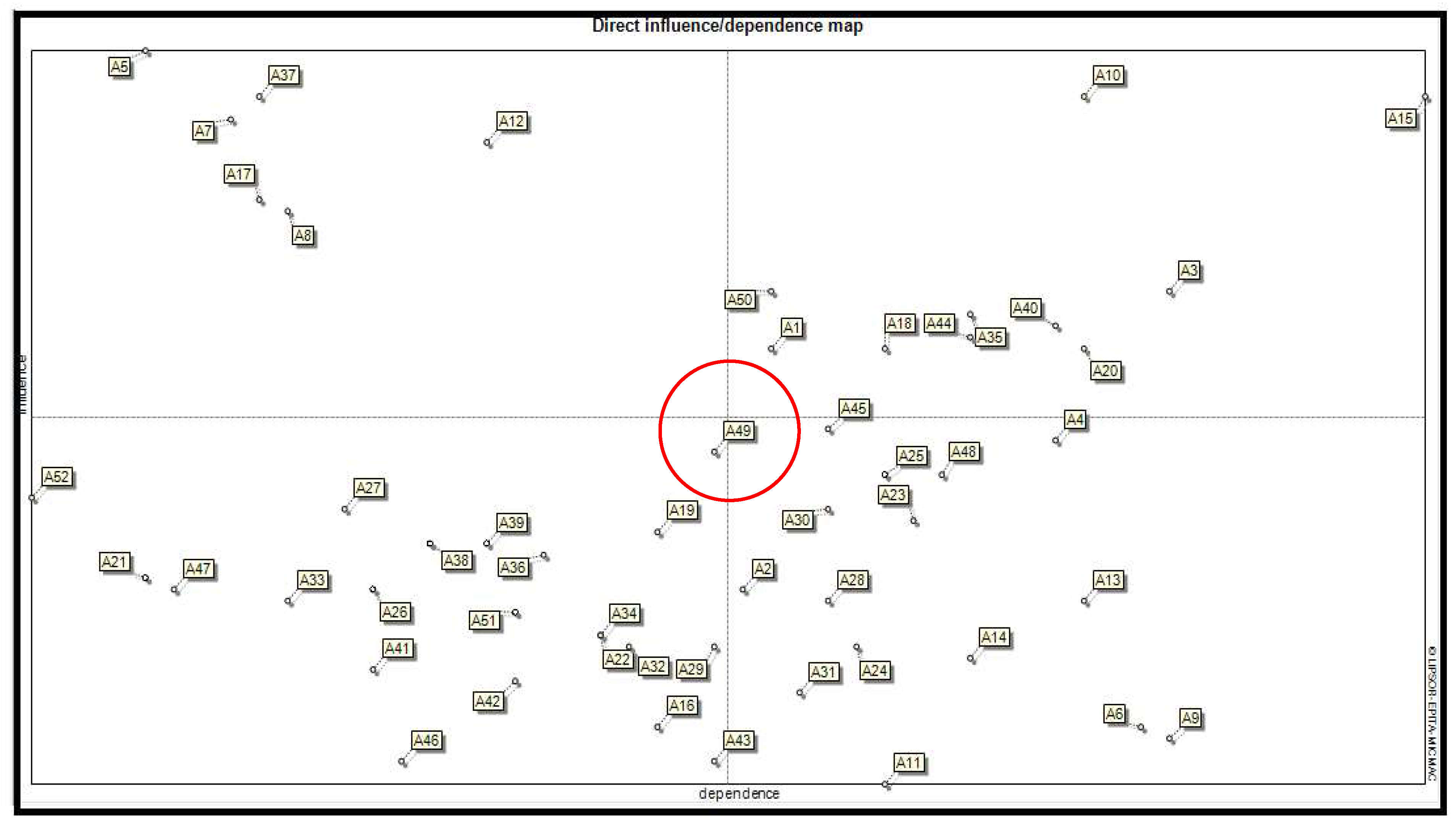

3.1.6. Regulatory Factors in Food Tourism Development in Rural Areas of Iran

3.2. Scenario development for food tourism in rural areas of Iran

Scenario Analysis for Food Tourism Development in Rural Areas of Iran

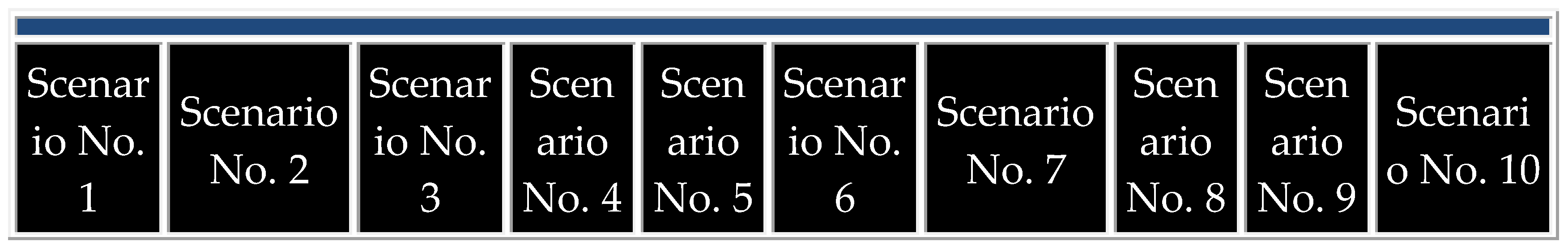

| Group | Scenario number | Consistency value | Icons. Descript. | Total impact score | Characteristics |

| 3 |

Scenario No. 9 | -1 | 1 | 15 | In this group, Scenario 9 and Scenario 10 are positioned in a state of complete crisis, as illustrated in Figure 5-5. These scenarios depict a full-scale crisis where there is no evidence of efforts to improve or even maintain the current situation, except for Government support and assistance, which continues along its current trajectory. The critical features of these scenarios, detailed in Table 10, encompass a severe reduction or deterioration in all key factors: a decrease in the number of festivals, an increase in prices, a decline in food quality, a degradation of infrastructure quality, reduced government support for food tourism, and diminished investments in the development of food tourism . |

| Scenario No. 10 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Conduct studies on the impact of food tourism development on other tourism sectors.

- Identify the competitiveness capacities of food tourism among the provinces of Iran.

- Assess the position of Iranian provinces in terms of food tourism development capacities using MCDM techniques.

- Investigate the obstacles and constraints of food tourism development in rural areas of Iran.

- Identify strategies to attract private and public sector participation in investments for food tourism development.

Appendix A

References

- M. Koyuncu, E. Yörük, and B. Gürel, “Does violent conflict affect the distribution of social welfare? Evidence from India’s Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act,” Soc Policy Adm, vol. 57, no. 5, pp. 656–678, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Paping and J. Pawlowski, “Success or Failure in the City? Social Mobility and Rural-Urban Migration in Nineteenth- and Early-Twentieth-Century Groningen, the Netherlands,” Hist Life Course Stud, vol. 6, pp. 69–94, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Rai, “The labor of social change: Seasonal labor migration and social change in rural western India,” Geoforum, vol. 92, pp. 171–180, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Bernzen, J. C. Jenkins, and B. Braun, “Climate Change-Induced Migration in Coastal Bangladesh? A Critical Assessment of Migration Drivers in Rural Households under Economic and Environmental Stress,” Geosciences (Basel), vol. 9, no. 1, p. 51, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Hofstede, K. Salemink, and T. Haartsen, “The appreciation of rural areas and their contribution to young adults’ staying expectations,” J Rural Stud, vol. 95, pp. 148–159, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Kaag, G. Baltissen, G. Steel, and A. Lodder, “Migration, Youth, and Land in West Africa: Making the Connections Work for Inclusive Development,” Land (Basel), vol. 8, no. 4, p. 60, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Sapena, M. Gamperl, M. Kühnl, C. Garcia-Londoño, J. Singer, and H. Taubenböck, “Cost estimation for the monitoring instrumentation of landslide early warning systems,” Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, vol. 23, no. 12, pp. 3913–3930, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Zeng et al., “Quantitative risk assessment of the Shilongmen reservoir landslide in the Three Gorges area of China,” Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment, vol. 82, no. 6, p. 214, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Wolniak, S. Saniuk, S. Grabowska, and B. Gajdzik, “Identification of Energy Efficiency Trends in the Context of the Development of Industry 4.0 Using the Polish Steel Sector as an Example,” Energies (Basel), vol. 13, no. 11, p. 2867, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Pakawanich, A. Udomsakdigool, and C. Khompatraporn, “Crop production scheduling for revenue inequality reduction among smallholder farmers in an agricultural cooperative,” Journal of the Operational Research Society, vol. 73, no. 12, pp. 2614–2625, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. AdrianaTisca, N. Istrat, C. D. Dumitrescu, and G. Cornu, “Management of Sustainable Development in Ecotourism. Case Study Romania,” Procedia Economics and Finance, vol. 39, pp. 427–432, 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Z. A. Abdurahman, J. K. Ali, L. Y. B. Khedif, Z. Bohari, J. A. Ahmad, and S. A. Kibat, “Ecotourism Product Attributes and Tourist Attractions: UiTM Undergraduate Studies,” Procedia Soc Behav Sci, vol. 224, pp. 360–367, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- P. Dang, L. Ren, and J. Li, “Livelihood Resilience or Policy Attraction? Factors Determining Households’ Willingness to Participate in Rural Tourism in Western China,” Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 19, no. 12, p. 7224, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. A. Quezada-Sarmiento, J. del C. Macas-Romero, C. Roman, and J. C. Martin, “A body of knowledge representation model of ecotourism products in southeastern Ecuador,” Heliyon, vol. 4, no. 12, p. e01063, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Mallick, S. Rudra, and R. Samanta, “Sustainable ecotourism development using SWOT and QSPM approach: A study on Rameswaram, Tamil Nadu,” International Journal of Geoheritage and Parks, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 185–193, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Huang, F. Lin, D. Chu, L. Wang, J. Liao, and J. Wu, “Spatiotemporal Evolution and Trend Prediction of Tourism Economic Vulnerability in China’s Major Tourist Cities,” ISPRS Int J Geoinf, vol. 10, no. 10, p. 644, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- I. Yeoman and U. McMahon-Beatte, “The future of food tourism,” Journal of Tourism Futures, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 95–98, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. M. Hall, “Chapter 9. Rural Wine and Food Tourism Cluster and Network Development,” in Rural Tourism and Sustainable Business, Multilingual Matters, 2005, pp. 149–164. [CrossRef]

- M. Šmid Hribar, N. Razpotnik Visković, and D. Bole, “Models of stakeholder collaboration in food tourism experiences,” Acta geographica Slovenica, vol. 61, no. 1, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Mariani and B. Okumus, “Features, drivers, and outcomes of food tourism,” British Food Journal, vol. 124, no. 2, pp. 401–405, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Fountain, “The future of food tourism in a post-COVID-19 world: insights from New Zealand,” Journal of Tourism Futures, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 220–233, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Dougherty and G. Green, “Local Food Tourism Networks and Word of Mouth,” J Ext, vol. 49, no. 2, Apr. 2011. [CrossRef]

- T. Jung, E. M. Ineson, M. Kim, and M. H. Yap, “Influence of festival attribute qualities on Slow Food tourists’ experience, satisfaction level and revisit intention,” Journal of Vacation Marketing, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 277–288, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- I. Yeoman, U. McMahon-Beattie, K. Findlay, S. Goh, S. Tieng, and S. Nhem, “Future Proofing the Success of Food Festivals Through Determining the Drivers of Change: A Case Study of Wellington on a Plate,” Tourism Analysis, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 167–193, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- I. Yeoman and U. McMahon-Beatte, “The future of food tourism,” Journal of Tourism Futures, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 95–98, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Lin et al., “Determining food tourism consumption of wild mushrooms in Yunnan Provence, China: A projection-pursuit approach,” Heliyon, vol. 9, no. 3, p. e14638, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Everett, “Production Places or Consumption Spaces? The Place-making Agency of Food Tourism in Ireland and Scotland,” Tourism Geographies, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 535–554, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- C.-T. (Simon) Tsai and Y.-C. Wang, “Experiential value in branding food tourism,” Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 56–65, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- E. Koc, “Food tourism: A practical marketing guide,” Ann Tour Res, vol. 54, pp. 233–234, Sep. 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. Fusté-Forné and T. Jamal, “Slow food tourism: an ethical microtrend for the Anthropocene,” Journal of Tourism Futures, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 227–232, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Wondirad, Y. Kebete, and Y. Li, “Culinary tourism as a driver of regional economic development and socio-cultural revitalization: Evidence from Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia,” Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, vol. 19, p. 100482, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. C. Nwokorie, “Food Tourism in Local Economic Development and National Branding in Nigeria,” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Stalmirska and A. Ali, “Sustainable development of urban food tourism : A cultural globalisation approach,” Tourism and Hospitality Research, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Diawati and H. H. Loupias, “The Negative Impact of Rapid Growth of Culinary Tourism in Bandung City: Implementation of Innovative and Eco- Friendly Model Are Imperative,” in Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Tourism, Gastronomy, and Tourist Destination (ICTGTD 2018), Paris, France: Atlantis Press, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Yang, J. Qiu, K. Ding, S. Zhang, and W. Fan, “Visitor preferences in rural gastronomic tourism environment and the related design implications,” Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 3, p. e25072, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Adriana, “Tourism of the Future – An on Going Challenge,” Studies in Business and Economics, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 258–272, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- I. Boavida-Portugal, J. Rocha, and C. C. Ferreira, “Exploring the impacts of future tourism development on land use/cover changes,” Applied Geography, vol. 77, pp. 82–91, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. QUİGLEY, M. CONNOLLY, E. MAHON, and M. MAC CON IOMAİRE, “Insight from Insiders: A Phenomenological Study for Exploring Food Tourism Policy in Ireland 2009-2019,” Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Research (AHTR), vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 188–215, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Rousta and D. Jamshidi, “Food tourism value: Investigating the factors that influence tourists to revisit,” Journal of Vacation Marketing, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 73–95, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Di-Clemente, J. M. Hernández-Mogollón, and T. López-Guzmán, “Culinary Tourism as An Effective Strategy for a Profitable Cooperation between Agriculture and Tourism,” Soc Sci, vol. 9, no. 3, p. 25, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Soltani, N. Soltani Nejad, F. Taheri Azad, B. Taheri, and M. J. Gannon, “Food consumption experiences: a framework for understanding food tourists’ behavioral intentions,” International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 75–100, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Al Harthy, A. M. Karim, and A. O. Rahid, “Investigating Determinants of Street Food Attributes and Tourist Satisfaction: An Empirical study of Food Tourism Perspective,” International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Management Sciences, vol. 11, no. 2, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. (Sam) Kim, J. Y. Choe, and S. Lee, “How are food value video clips effective in promoting food tourism? Generation Y versus non–Generation Y,” Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 377–393, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Pezeshki, N. Kalantari, A. Pourreza, and A. Haghighian Roudsari, “Comida como Atração Turística:,” Revista Rosa dos Ventos - Turismo e Hospitalidade, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 199–224, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Sims, “Putting place on the menu: The negotiation of locality in UK food tourism, from production to consumption,” J Rural Stud, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 105–115, Apr. 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. Everett, “Theoretical turns through tourism taste-scapes: the evolution of food tourism research,” Research in Hospitality Management, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 3–12, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Sidali, P. Morocho, and E. Garrido-Pérez, “Food Tourism in Indigenous Settings as a Strategy of Sustainable Development: The Case of Ilex guayusa Loes. in the Ecuadorian Amazon,” Sustainability, vol. 8, no. 10, p. 967, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- E. Park, K. Muangasame, and S. Kim, “‘We and our stories’: constructing food experiences in a UNESCO gastronomy city,” Tourism Geographies, vol. 25, no. 2–3, pp. 572–593, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, “Mapping Research on Food Tourism: A Review Study,” Paradigm: A Management Research Journal, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 50–69, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Pourfakhimi, Z. Nadim, G. Prayag, and R. Mulcahy, “The influence of neophobia and enduring food involvement on travelers’ perceptions of wellbeing—Evidence from international visitors to Iran,” International Journal of Tourism Research, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 178–191, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Mahmoodi, M. Roman, and P. Prus, “Features and Challenges of Agritourism: Evidence from Iran and Poland,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 8, p. 4555, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Torabi Farsani, H. Zeinali, and M. Moaiednia, “Food heritage and promoting herbal medicine-based niche tourism in Isfahan, Iran,” Journal of Heritage Tourism, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 77–87, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Varmazyari, M. Babaei, K. Vafadari, and B. Imani, “Motive-based segmentation of tourists in rural areas: the case of Maragheh, East Azerbaijan, Iran,” International Journal of Tourism Sciences, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 316–331, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. Dadvar-Khani, “Second Home Tourism and Agriculture in Rural Areas: Examining the Effects of Second Homes on Agricultural Resources in Northern Iran,” J Rural Dev, vol. 38, no. 1, p. 123, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Everett, “Beyond the visual gaze?,” Tour Stud, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 337–358, Dec. 2008. [CrossRef]

- T. Lunchaprasith and D. Macleod, “Food Tourism and the Use of Authenticity in Thailand,” Tourism Culture & Communication, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 101–116, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. AHLAWAT, P. SHARMA, and P. K. GAUTAM, “SLOW FOOD AND TOURISM DEVELOPMENT: A CASE STUDY OF SLOW FOOD TOURISM IN UTTARAKHAND, INDIA,” GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 751–760, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Rachão, Z. Breda, C. Fernandes, and V. Joukes, “Food tourism and regional development: A systematic literature review,” European Journal of Tourism Research, vol. 21, pp. 33–49, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Food tourism: a practical marketing guide. UK: CABI, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. (Sam) Kim, J. Y. Choe, and S. Lee, “How are food value video clips effective in promoting food tourism? Generation Y versus non–Generation Y,” Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 377–393, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Gittins and Gerard McElwee, “Constrained rural entrepreneurship: Upland farmer responses to the socio-political challenges in England’s beef and sheep sector,” J Rural Stud, vol. 104, p. 103141, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Wu et al., “Reverse entrepreneurship and integration in poor areas of China: Case studies of tourism entrepreneurship in Ganzi Tibetan Region of Sichuan,” J Rural Stud, vol. 96, pp. 358–368, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Nordbø, “Female entrepreneurs and path-dependency in rural tourism,” J Rural Stud, vol. 96, pp. 198–206, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Liu, X. Dou, J. Li, and L. A. Cai, “Analyzing government role in rural tourism development: An empirical investigation from China,” J Rural Stud, vol. 79, pp. 177–188, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. (Stephanie) Yang and H. Xu, “Producing an ideal village: Imagined rurality, tourism and rural gentrification in China,” J Rural Stud, vol. 96, pp. 1–10, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Jamini and A. Dehghani, “Evaluation and analysis of resilience of rural tourism and identification of key drivers affecting it in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic in Iran,” Journal of Research & Rural Planning, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 99–116, 2022.

- P. Chen, N. Clarke, and B. J. Hracs, “Urban-rural mobilities: The case of China’s rural tourism makers,” J Rural Stud, vol. 95, pp. 402–411, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Qu and S. Zollet, “Neo-endogenous revitalisation: Enhancing community resilience through art tourism and rural entrepreneurship,” J Rural Stud, vol. 97, pp. 105–114, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. A. Stokowski, W. F. Kuentzel, M. M. Derrien, and Y. L. Jakobcic, “Social, cultural and spatial imaginaries in rural tourism transitions,” J Rural Stud, vol. 87, pp. 243–253, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Wu et al., “Reverse entrepreneurship and integration in poor areas of China: Case studies of tourism entrepreneurship in Ganzi Tibetan Region of Sichuan,” J Rural Stud, vol. 96, pp. 358–368, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Renko, N. Renko, and T. Polonijo, “Understanding the Role of Food in Rural Tourism Development in a Recovering Economy,” Journal of Food Products Marketing, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 309–324, Jun. 2010. [CrossRef]

- L. W. Lan, W.-W. Wu, and Y.-T. Lee, “Promoting Food Tourism with Kansei Cuisine Design,” Procedia Soc Behav Sci, vol. 40, pp. 609–615, 2012. [CrossRef]

- A. de Jong and P. Varley, “Food tourism policy: Deconstructing boundaries of taste and class,” Tour Manag, vol. 60, pp. 212–222, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Ellis, E. Park, S. Kim, and I. Yeoman, “What is food tourism?,” Tour Manag, vol. 68, pp. 250–263, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. H. Kim, M. Kim, and B. K. Goh, “An examination of food tourist’s behavior: Using the modified theory of reasoned action,” Tour Manag, vol. 32, no. 5, pp. 1159–1165, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- C. Bellia, M. Pilato, and H. Seraphin, “Determining tourism drivers and followers: a methodological approach,” Anatolia, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 259–262, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Massidda, R. Piras, and N. Seetaram, “Analysing the drivers of itemised tourism expenditure from the UK using survey data,” Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights, vol. 3, no. 1, p. 100037, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Tikkanen, “Maslow’s hierarchy and food tourism in Finland: five cases,” British Food Journal, vol. 109, no. 9, pp. 721–734, Sep. 2007. [CrossRef]

- A. Correia, M. Moital, C. F. Da Costa, and R. Peres, “The determinants of gastronomic tourists’ satisfaction: a second-order factor analysis,” Journal of Foodservice, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 164–176, Jun. 2008. [CrossRef]

- T. Jung, E. M. Ineson, M. Kim, and M. H. Yap, “Influence of festival attribute qualities on Slow Food tourists’ experience, satisfaction level and revisit intention,” Journal of Vacation Marketing, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 277–288, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- K. QUİGLEY, M. CONNOLLY, E. MAHON, and M. MAC CON IOMAİRE, “Insight from Insiders: A Phenomenological Study for Exploring Food Tourism Policy in Ireland 2009-2019,” Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Research (AHTR), vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 188–215, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Hanafiah and N. A. A. Hamdan, “Determinants of Muslim travellers Halal food consumption attitude and behavioural intentions,” Journal of Islamic Marketing, vol. 12, no. 6, pp. 1197–1218, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Statistical Center of Iran, “The Statistical Yearbook of Iran contains,” 2023.

- H. Esfandyari, S. Choobchian, Y. Momenpour, and H. Azadi, “Sustainable rural development in Northwest Iran: proposing a wellness-based tourism pattern using a structural equation modeling approach,” Humanit Soc Sci Commun, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 499, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Komasi, S. Hashemkhani Zolfani, and F. Cavallaro, “The COVID-19 Pandemic and Nature-Based Tourism, Scenario Planning Approach (Case Study of Nature-Based Tourism in Iran),” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 7, p. 3954, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Komasi, S. Hashemkhani Zolfani, O. Prentkovskis, and P. Skačkauskas, “Urban Competitiveness: Identification and Analysis of Sustainable Key Drivers (A Case Study in Iran),” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 13, p. 7844, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Weimer-Jehle, “Cross-impact balances: A system-theoretical approach to cross-impact analysis,” Technol Forecast Soc Change, vol. 73, no. 4, pp. 334–361, May 2006. [CrossRef]

- K. QUİGLEY, M. CONNOLLY, E. MAHON, and M. MAC CON IOMAİRE, “Insight from Insiders: A Phenomenological Study for Exploring Food Tourism Policy in Ireland 2009-2019,” Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Research (AHTR), vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 188–215, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. W. Lan, W.-W. Wu, and Y.-T. Lee, “Promoting Food Tourism with Kansei Cuisine Design,” Procedia Soc Behav Sci, vol. 40, pp. 609–615, 2012. [CrossRef]

- A. Surenkok, R. Baggio, and M. A. Corigliano, “Gastronomy and Tourism in Turkey: The Role of ICTs,” in Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2010, Vienna: Springer Vienna, 2010, pp. 567–578. [CrossRef]

- M. Šmid Hribar, N. Razpotnik Visković, and D. Bole, “Models of stakeholder collaboration in food tourism experiences,” Acta geographica Slovenica, vol. 61, no. 1, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- I. Yeoman, U. McMahon-Beattie, K. Findlay, S. Goh, S. Tieng, and S. Nhem, “Future Proofing the Success of Food Festivals Through Determining the Drivers of Change: A Case Study of Wellington on a Plate,” Tourism Analysis, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 167–193, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Lan, H. Yu, and L. Cui, “Application of Telemedicine in COVID-19: A Bibliometric Analysis,” Front Public Health, vol. 10, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- O. C. T. , & P. S. Alliance, “The rise of food tourism.”.

- S., C. R. , C. S. , K. R. , P. P. & B. B. Ecker, “Drivers of regional agritourism and food tourism in Australia. Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics – Bureau of Rural Sciences,” 2010.

- Z. , S. I. & T. S. Grigorova, “Rural Food Tourism. IBANESS Conference Series – Plovdiv.”.

- Z. Nader, “Regional development foresight with a scenario-based planning approach (Case study: East Azerbaijan Province),” Tabriz, 2009.

| Researcher / Researchers | Year | Title | Method | Results |

| [78] | 2007 | Maslow’s hierarchy and food tourism in Finland: five cases |

multiple-case design and Descriptive research The empirical data has been collected from literature, studies, websites, and conducting an interview. For data analysis, analytic generalization has been utilized. |

Understanding the needs and motivations of tourists, reducing taxation, selling products and goods at lower prices, income, harmonizing regulations, increasing competition among companies involved in food production, holding meetings, conferences, and trade shows, and cohesive marketing efforts can be effective in the development of food tourism in Finland |

| [79] | 2008 | The determinants of gastronomic tourists’ satisfaction: a second-order factor analysis | Descriptive research The data has been collected through a survey using 377 questionnaires. For data analysis, the AMOS software (structural equation modeling) has been utilized. |

The three main factors affecting the satisfaction of food tourists in Portugal are: Food-related factors (local dishes, presentation of food, authenticity, and uniqueness). Price and quality of food (beverage prices, course prices, food quality, and staff service). Atmosphere and environment (ethnic decor, decoration, modern music, lighting, and entertainment). |

| [22] | 2011 | Local Food Tourism Networks and Word of Mouth | The descriptive-analytical method has been employed for this study. Data has been gathered through postal surveys (475 questionnaires) and interviews. | In Wisconsin, oral advertising plays a pivotal role in forming and maintaining local food tourism networks by connecting farmers and restaurateurs. Additionally, word-of-mouth advertising primarily informs tourists about tourism opportunities in the region. |

| [75] | 2011 | An examination of food tourist’s behaviour: Using the modified theory of reasoned action |

The descriptive-analytical method was employed, and data was collected from 305 questionnaires among tourists participating in the food festival. The collected data was analyzed using SPSS 17.0 and AMOS 4.0 software. | In the southwestern United States, perceived value, contentment, and satisfaction for intention to return are important behavioural determinants for food tourism. |

| [80] | 2015 | Influence of Festival Attribute Qualities on Slow Food Tourists’ Experience, Satisfaction Level and Revisit Intention: The Case of the Mold Food and Drink Festival |

quantitative research Data was collected through 209 questionnaires completed among participants in the food festival. The data was analyzed using SPSS and AMOS software. |

Programs, food quality, and other recreational and welfare facilities at the festival can effectively develop food tourism in Wales by increasing visitor satisfaction and encouraging repeat visits. |

| [81] |

2019 |

Insight from insiders: A phenomenological study for exploring food tourism policy in Ireland 2009-2019 | Phenomenological hermeneutics (a qualitative method for examining the lived experience of stakeholders related to food tourism) Data were collected through conducting 10 semi-structured, in-depth interviews. The data were analyzed using thematic analysis method. |

Key policymakers, networking and clustering, social entrepreneurs, government support, creation of regional tourism brands, linking food with cultural initiatives, and marketing strategies have played a pivotal role in developing food tourism in Ireland. |

| [39] | 2020 | Food tourism value: Investigating the factors that influence tourists to revisit |

multivariate analysis method Multivariate analysis method 891 questionnaires were used to collect the data. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was used for data analysis. |

aste/quality value, health value, price, emotional value, and credibility are among the factors that have a positive impact on the attitude of food tourists in the city of Shiraz, Iran. |

| [42] | 2021 | Investigating Determinants of Street Food Attributes and Tourist Satisfaction: An Empirical study of Food Tourism Perspective | positivist research approach Positivist research approach Data were collected through questionnaire completion among 331 tourists. Smart PLS 3.0 was used for data evaluation. |

Quality of services, marketing techniques, diversification and coordination of tourism products, improvement of agricultural techniques, enhancement of destination reputation, and improvement of place branding are among the most important factors and strategies for food tourism growth in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. |

| [49] | 2022 | Mapping Research on Food Tourism: A Review Study |

descriptive and bibliometric analysis Descriptive and bibliographic analysis The data was collected from published articles (in the most reputable journals, with the participation of top authors, and from leading countries that have researched food tourism) from 2006 to 2021. Statistical tools such as modularity class and PageRank have been used for data analysis. |

Studies in the field of food tourism have mainly been conducted in Britain and Canada. During this period, the main focus of studies in food tourism has been increasing tourist satisfaction and loyalty. Additionally, the results have shown that experience, local, preservation, development, motivation, market, culture, cuisine, model, behaviour, image, perception, intention, loyalty, value, attitude, active, technology, content, use, and review are the key keywords in studies in the field of food tourism. |

| [26] | 2023 | Determining food tourism consumption of wild mushrooms in Yunnan Provence, China: A projection-pursuit approach |

quantitative methods The data was obtained through the completion of 500 questionnaires. The projection pursuit model (PPM) and structural equation modeling (SEM) were used for data analysis. |

The quality and quantity of food resources, attention to tourists’ needs, and tourists’ perceptions are the most important factors influencing the development of wild mushroom-related food tourism in Yunnan Province, China. |

| Encoding | Factors | Reference | Encoding | Factors | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Understanding the motivations and needs of tourists | [78] | A27 | Coordination of laws and policies | [19,72,80] |

| A2 | Reduction in tax rates | [78] | A28 | Attention to tourists’ food interests. | [89] |

| A3 | The decoration of food, its colour, and presentation | [72,79] | A29 | Satisfaction and contentment for repeat visit intention | [75] |

| A4 | Increasing competition among companies involved in food production | [78] | A30 | The internet and web (Information and Communication Technology) in the tourism sector |

[90] |

| A5 | Creating campaigns and organizing festivals, events, meetings, conferences, and trade shows. |

[78,79,80], [91,92] | A31 | Advertising, especially word-of-mouth and social media advertising | [20,22,41] |

| A6 | The authenticity of food | [40,79] | A32 | The quality, shape, and colour of food containers | [93] |

| A7 | Prices (for food, drinks, courses, etc.) | [39,78,79] | A33 | Personnel (attire and interaction manner, ensuring safety by them) | [20,79,89] |

| A8 | The quality of food | [79,89] | A34 | Marketing |

[41,42,48], [57,78] |

| A9 | Designing the ambient decoration of the destination (considering ethnicities, furniture, artworks, environmental embellishments, lighting quality, entertainment such as music, shows, etc.) | [79,89] | A35 | Accurate capacity assessment of assets | [94] |

| A10 | Industrial reconstruction | [95] | A36 | Continuous and comprehensive evaluation of food tourism destinations | [94] |

| A11 | Proximity/accessibility to accommodation | [95] | A37 | Investment. | [96] |

| A12 | The quality of infrastructure |

[57,95] | A38 | Collaboration and stakeholder participation | [19,74,92], [94] |

| A13 | Local lifestyle | [95] | A39 | Enhancing more interaction between tourists and local communities. | [19] |

| A14 | National food holidays calendar | [96] | A40 | Adding a dreamy aspect to festivals | [92] |

| A15 | High capacity in agriculture and animal husbandry | [26,96] | A41 | Elevating the level of motivation for well-being and exclusivity in the local community | [92] |

| A16 | Formation of tourism companies | [96] | A42 | The fluid identity of the festival and its food. | [92] |

| A17 | Government support and assistance | [57] | A43 | Travel information provision | [20] |

| A18 | Diversity of food | [40] | A44 | Development and promotion of street food | [76] |

| A19 | Respect for tourists’ dietary regime laws in tourist destinations | [82] | A45 | Food safety | [76] |

| A20 | Traditional restaurants | [96] | A46 | Attention to the authenticity of the tourism destination. | [56] |

| A21 | The perceived quality by tourists | [26] | A47 | Establishment of food museums |

[96] |

| A22 | Improving communication between tourists and the host community | [96] | A48 | Providing quantitative and qualitative information about food |

[20] |

| A23 | Awareness (local and general) of tourists’ preferences and food tourism | [57] | A49 | Food tourism managers | [20] |

| A24 | Values (health value, emotional value, experience and consumption value of local food, perceived value for repeat visit intention, valuing local people) | [39,41,75] | A50 | Innovation and creativity in food and destination | [20,58,79], [95] |

| A25 | Cooking motivation | [40] | A51 | Observance of health protocols | [20] |

| A26 | Adaptation and coordination of tourism products | [42] | A52 | Human risks such as the COVID-19 pandemic and... | [20] |

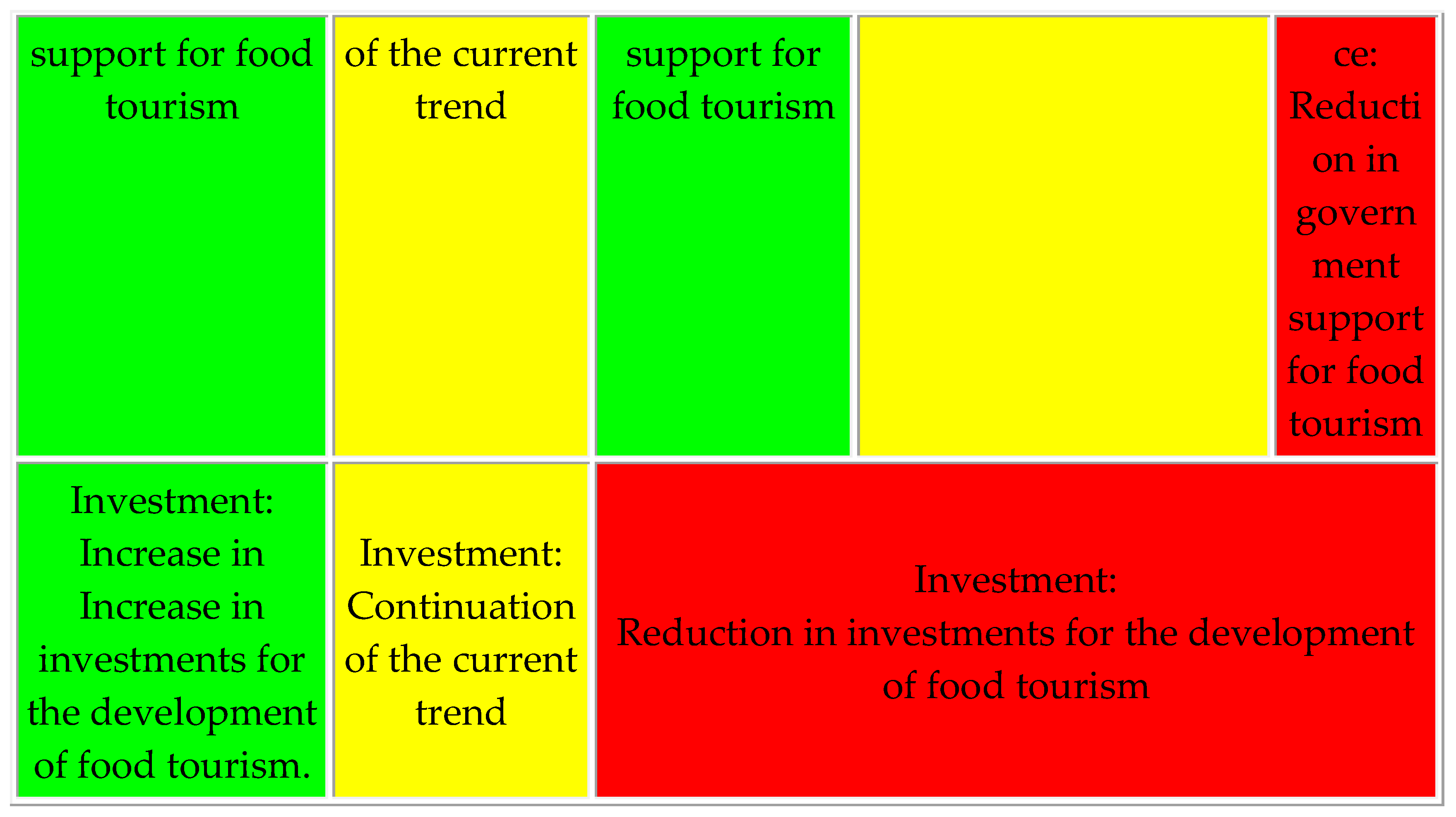

| MDI characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Matrix size | 52 |

| Number of iterations | 2 |

| Number of zeros | 359 |

| Number of ones | 896 |

| Number of twos | 874 |

| Number of threes | 575 |

| Number of P | 0 |

| Total | 2345 |

| Fillrat | 86.72 |

| Iteration | Influence | Dependence |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 99% | 96% |

| 2 | 100% | 100% |

| Rank | Label | Direct influence | Label | Direct dependence | Label | Indirect influence | Label | Indirect dependence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A5 | 279 | A15 | 251 | A5 | 271 | A15 | 248 |

| 2 | A10 | 270 | A3 | 231 | A15 | 267 | A9 | 234 |

| 3 | A15 | 270 | A9 | 231 | A37 | 267 | A3 | 233 |

| 4 | A37 | 270 | A6 | 228 | A10 | 266 | A6 | 228 |

| 5 | A7 | 265 | A10 | 224 | A7 | 264 | A20 | 224 |

| 6 | A12 | 260 | A13 | 224 | A12 | 258 | A10 | 224 |

| 7 | A17 | 249 | A20 | 224 | A17 | 252 | A13 | 223 |

| 8 | A8 | 247 | A4 | 222 | A8 | 237 | A40 | 223 |

| 9 | A3 | 231 | A40 | 222 | A3 | 227 | A4 | 222 |

| 10 | A50 | 231 | A14 | 215 | A50 | 226 | A35 | 213 |

| 11 | A35 | 226 | A35 | 215 | A35 | 223 | A44 | 213 |

| 12 | A40 | 224 | A44 | 215 | A20 | 223 | A14 | 212 |

| 13 | A44 | 222 | A48 | 212 | A40 | 220 | A23 | 211 |

| 14 | A1 | 219 | A23 | 210 | A18 | 220 | A48 | 211 |

| 15 | A18 | 219 | A11 | 208 | A1 | 218 | A18 | 210 |

| 16 | A20 | 219 | A18 | 208 | A44 | 217 | A25 | 210 |

| 17 | A45 | 203 | A25 | 208 | A4 | 201 | A11 | 205 |

| 18 | A4 | 201 | A24 | 205 | A45 | 200 | A30 | 204 |

| 19 | A49 | 199 | A28 | 203 | A49 | 200 | A45 | 203 |

| 20 | A25 | 194 | A30 | 203 | A25 | 193 | A1 | 202 |

| 21 | A48 | 194 | A45 | 203 | A48 | 193 | A24 | 202 |

| 22 | A52 | 189 | A31 | 201 | A30 | 192 | A28 | 201 |

| 23 | A27 | 187 | A1 | 199 | A27 | 191 | A31 | 199 |

| 24 | A30 | 187 | A50 | 199 | A52 | 191 | A2 | 197 |

| 25 | A23 | 185 | A2 | 196 | A23 | 189 | A50 | 197 |

| 26 | A19 | 183 | A29 | 194 | A19 | 182 | A29 | 194 |

| 27 | A38 | 180 | A43 | 194 | A38 | 181 | A49 | 193 |

| 28 | A39 | 180 | A49 | 194 | A36 | 180 | A43 | 193 |

| 29 | A36 | 178 | A16 | 189 | A39 | 179 | A32 | 189 |

| 30 | A21 | 173 | A19 | 189 | A21 | 175 | A19 | 188 |

| 31 | A2 | 171 | A32 | 187 | A47 | 175 | A22 | 188 |

| 32 | A26 | 171 | A22 | 185 | A28 | 172 | A16 | 187 |

| 33 | A47 | 171 | A34 | 185 | A2 | 171 | A34 | 180 |

| 34 | A13 | 169 | A36 | 180 | A33 | 170 | A51 | 180 |

| 35 | A28 | 169 | A42 | 178 | A13 | 170 | A39 | 178 |

| 36 | A33 | 169 | A51 | 178 | A26 | 169 | A36 | 177 |

| 37 | A51 | 167 | A12 | 176 | A34 | 168 | A42 | 177 |

| 38 | A22 | 162 | A39 | 176 | A51 | 167 | A12 | 176 |

| 39 | A34 | 162 | A38 | 171 | A32 | 163 | A38 | 171 |

| 40 | A24 | 160 | A46 | 169 | A14 | 162 | A46 | 170 |

| 41 | A29 | 160 | A26 | 167 | A22 | 161 | A27 | 168 |

| 42 | A32 | 160 | A41 | 167 | A29 | 161 | A41 | 168 |

| 43 | A14 | 157 | A27 | 164 | A24 | 159 | A26 | 165 |

| 44 | A41 | 155 | A8 | 160 | A31 | 154 | A17 | 162 |

| 45 | A42 | 153 | A33 | 160 | A42 | 153 | A33 | 159 |

| 46 | A31 | 151 | A17 | 157 | A41 | 152 | A37 | 159 |

| 47 | A6 | 144 | A37 | 157 | A9 | 145 | A8 | 157 |

| 48 | A16 | 144 | A7 | 155 | A16 | 145 | A7 | 154 |

| 49 | A9 | 141 | A47 | 151 | A6 | 143 | A21 | 151 |

| 50 | A43 | 137 | A5 | 148 | A46 | 138 | A47 | 150 |

| 51 | A46 | 137 | A21 | 148 | A43 | 136 | A5 | 146 |

| 52 | A11 | 132 | A52 | 139 | A11 | 135 | A52 | 145 |

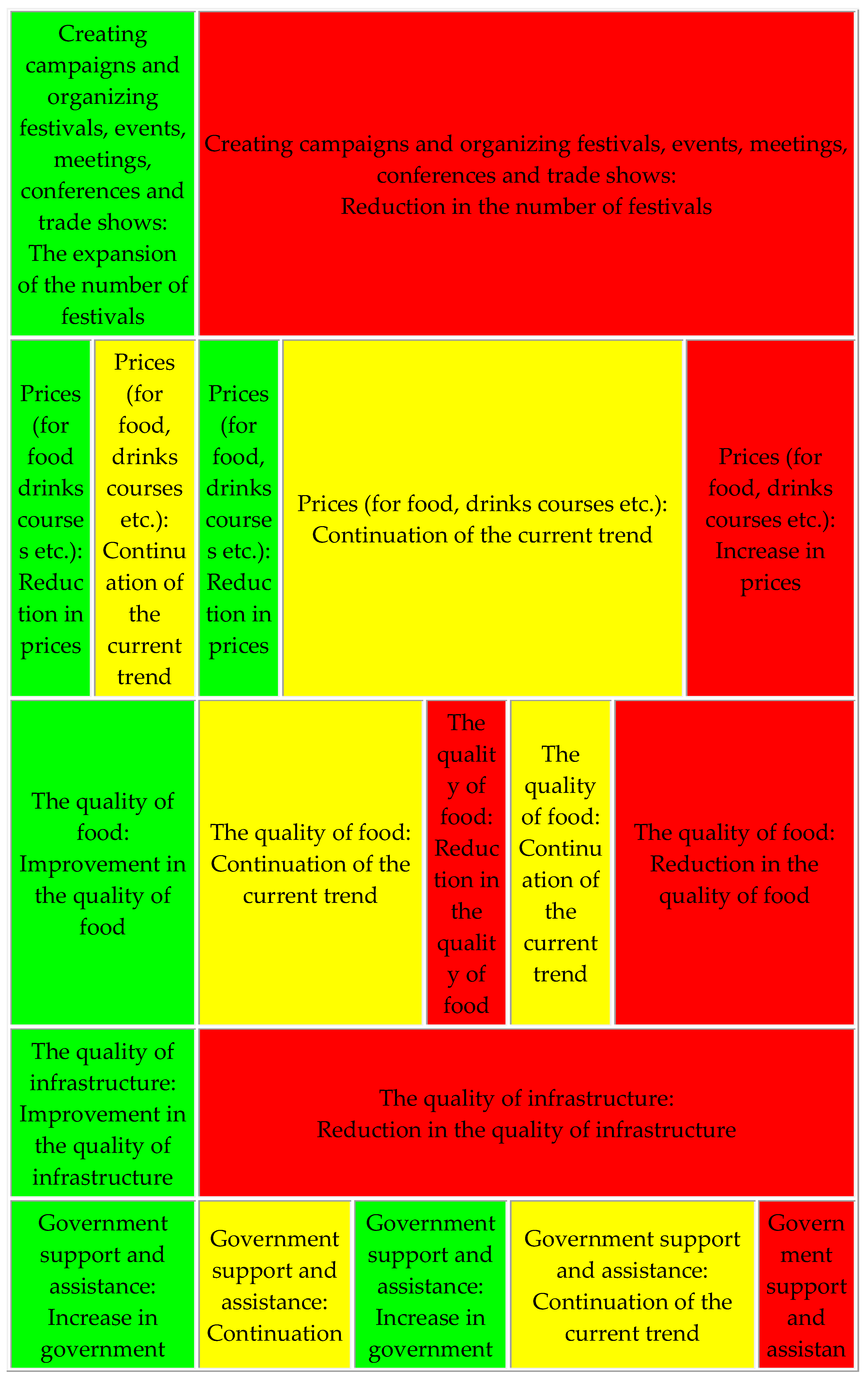

| Abbreviation mark | Key factors of food tourism development |

Possible scenarios for each factor |

Subcategories of each factor |

Degree of desirability | Status |

| A | Creating campaigns and organizing festivals, events, meetings, conferences, and trade shows |

A1 | The expansion of the number of festivals | Desirable | Green |

| A2 | Continuation of the current trend | Average | Yellow | ||

| A3 | Reduction in the number of festivals | Undesirable | Red | ||

| B | Prices (for food, drinks, courses, etc.) |

B1 | Reduction in prices | Desirable | Green |

| B2 | Continuation of the current trend | Average | Yellow | ||

| B3 | Increase in prices | Undesirable | Red | ||

| C | The quality of food |

C1 | Improvement in the quality of food | Desirable | Green |

| C2 | Continuation of the current trend | Average | Yellow | ||

| C3 | Reduction in the quality of food | Undesirable | Red | ||

| D | The quality of infrastructure |

D1 | Improvement in the quality of infrastructure | Desirable | Green |

| D2 | Continuation of the current trend | Average | Yellow | ||

| D3 | Reduction in the quality of infrastructure | Undesirable | Red | ||

| E | Government support and assistance |

E1 | Increase in government support for food tourism | Desirable | Green |

| E2 | Continuation of the current trend | Average | Yellow | ||

| E3 | Reduction in government support for food tourism | Undesirable | Red | ||

| F | Investment |

F1 | Increase in investments for the development of food tourism | Desirable | Green |

| F2 | Continuation of the current trend | Average | Yellow | ||

| F3 | Reduction in investments for the development of food tourism | Undesirable | Red | ||

| Total | 18 | ---- | ---- |

| Scenario Status | The number of scenarios |

| Weak (possible) scenarios | 196 |

| Scenarios with maximum incompatibility: 1 (Compatibility 1) | 10 |

| Strong or probable scenarios | 4 |

| Group | Scenario number | Consistency value | Icons. Descriptor. | Total impact score | Characteristics |

| 1 | Scenario No. 1 | 0 | 0 | 55 | All factors except one in this group will be in their most desirable state. These factors include creating campaigns and organizing festivals, events, meetings, conferences, and trade shows with an expanded number of festivals; improvement in the quality of food and infrastructure; increased government support for food tourism; and higher investments for its development. The only exception is the pricing factor, which continues its current trend in Scenario 2, reflecting ongoing conditions. |

| Scenario No. 2 | 0 | 0 | 49 |

| Group | Scenario number | Consistency value | Icons. Descript. | Total impact score | Characteristics |

| 2 |

Scenario No. 3 | -1 | 3 | 4 | In this group, two factors, Creating campaigns and organizing festivals, events, meetings, conferences and trade shows, and The quality of infrastructure, are collectively in critical conditions across all six scenarios. Scenario three involves a Reduction in prices for the Prices (for food drinks courses etc.) factor, while scenarios five and six for the Government support and assistance factor are favorable. Other factors remain in either current state continuation or critical conditions across all scenarios. |

| Scenario No. 4 | -1 | 3 | 2 | ||

| Scenario No. 5 | -1 | 2 | 10 | ||

| Scenario No. 6 | -1 | 2 | 14 | ||

| Scenario No. 7 | -1 | 1 | 9 | ||

| Scenario No. 8 | 0 | 0 | 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).