1. Introduction

The urban population is still growing, and it is expected 5 billion people will live in towns and cities by 2030 [

1] and in 2050 will swell to 70% of the global population [

1,

2,

3]. Most of this population growth will occur in the developing countries, mainly in Asia and Africa [

1,

4], and in cities of countries with low income and a young and poorer population ([

2,

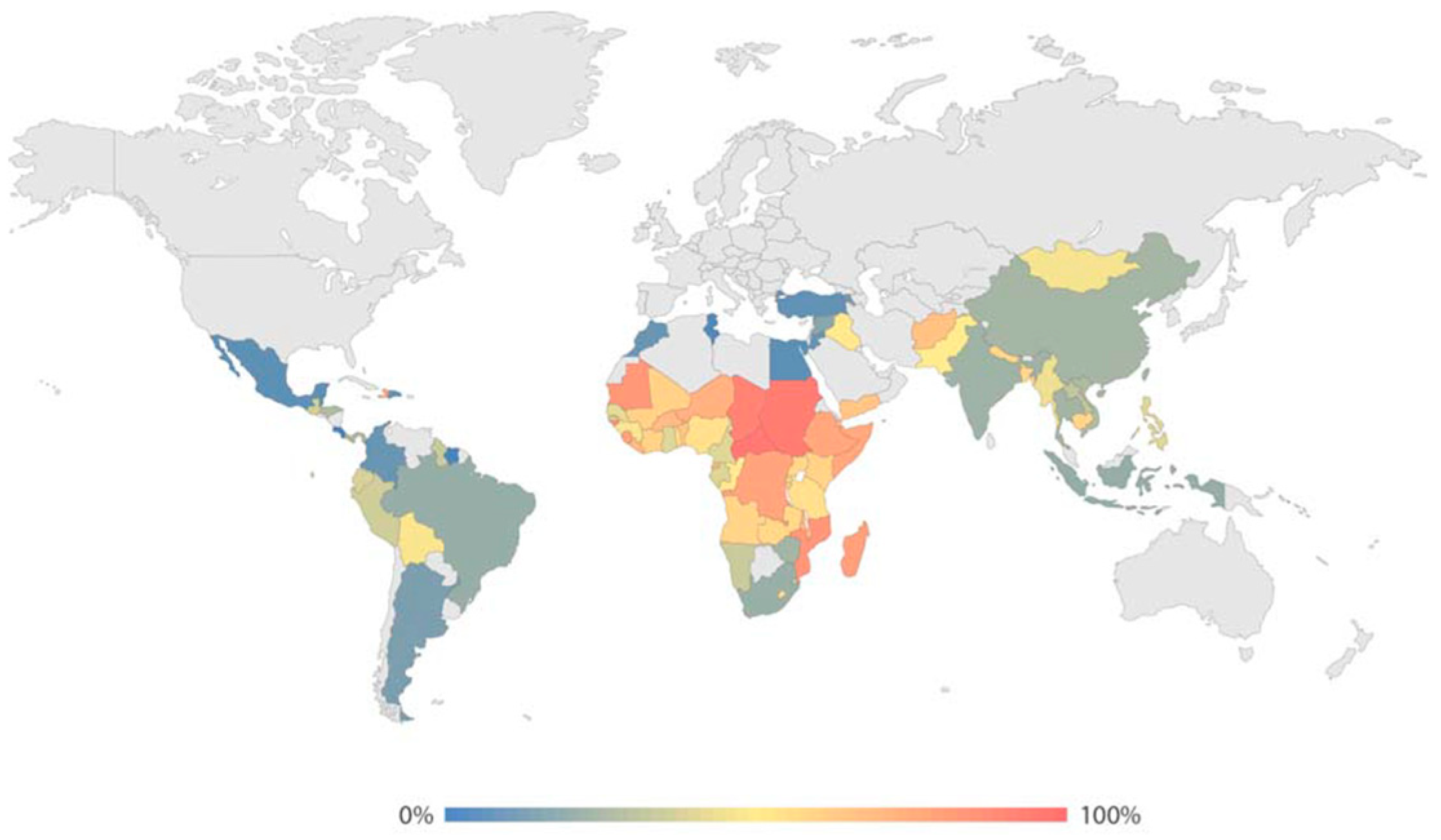

4]. At present, 61,7% of urban population in Africa lives in slums (

Figure 1), and until 2050, estimates revealed this continent will present 1.2 billion of urban population [

4].

Majority of the informal settlements are developed in areas non-appropriate for habitation and with high public health and environmental risks, exacerbated by the type of land use and climate change [

6,

7,

8,

9]. In general, living in a city in the “global south”, with latrines, septic tanks and aging sewers, and fecal sludge with no adequate final disposal, is not the same as living in the “global north”, with sewers, Wastewater Treatment Plants (WWTP), and regulated services. Informal settlement “present a severe problem to the development of society, particularly to public health and respective socioeconomic context” [

10] (p.59). Despite the better results in decreasing the number of people living in slums and informal settlements in the last few years [

3] over 1 billion of people are still living in slums without basic infrastructures [

3,

11,

12]. But cities have an important role in combating climate change, epidemics, and poverty, and seems to have a negative correlation between urbanization and poverty (

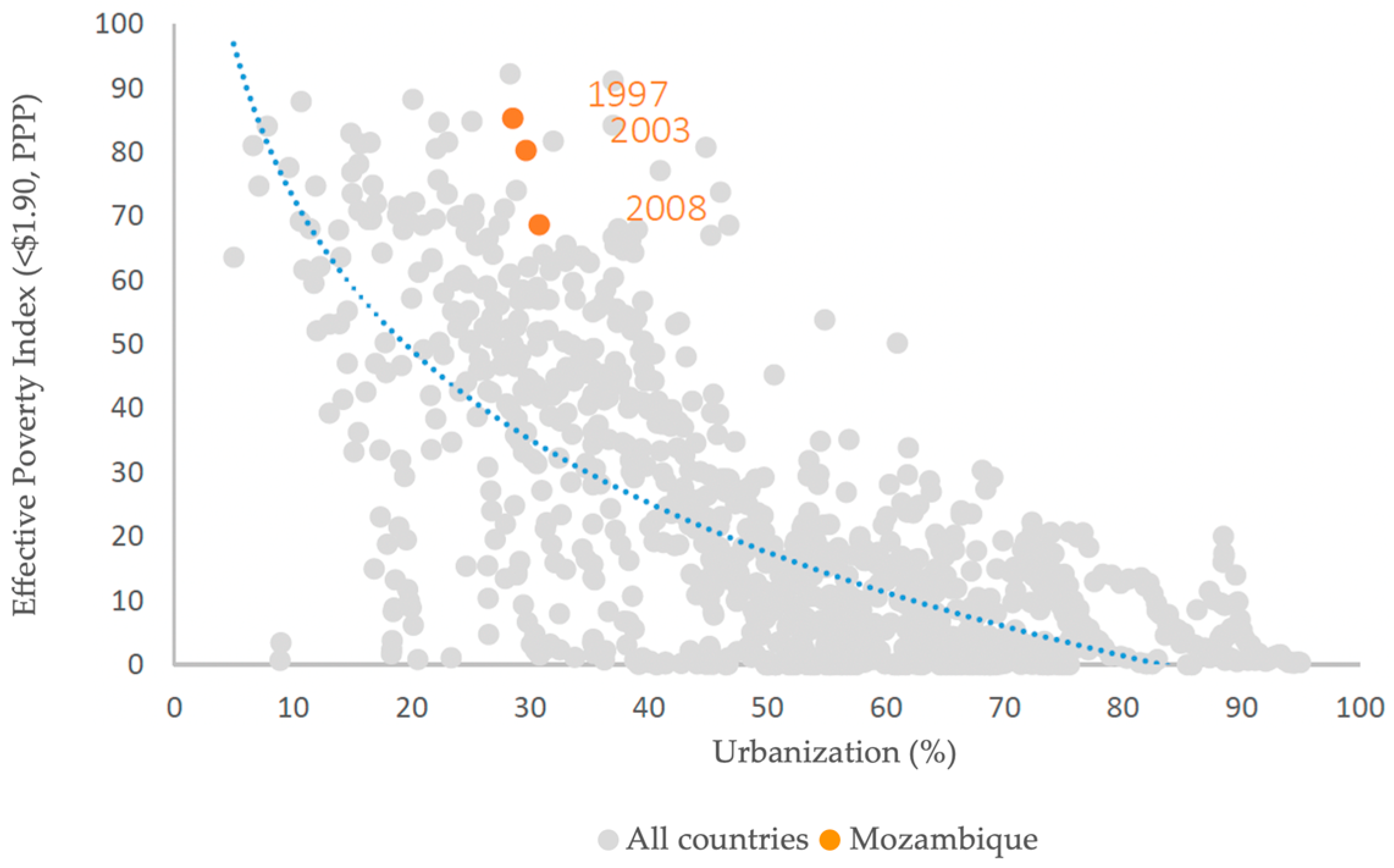

Figure 2).

The challenge of urbanization was recognized in 1976 at the Conference – Habitat I, which took place in Vancouver, Canada. This conference focused on issues related to urbanization, housing, and sustainable human settlements. At this time, three principal components of the human settlements have been identified: shelter, infrastructure, and services. Furthermore, it was recommended that, given their interrelationships, they should be planned in an integrated way, even if it is not possible to implement them at the same time [

14].

Although the slums and informal settlements have existed for a long time, mainly because of rapid population growth, migrations from rural to urban areas (towns and cities) [

10], and the historical urbanization of cities mainly in Africa [

15] challenges are getting more critical. Only in 2001 on Declaration Cities was identified the term slums and unplanned settlements and defined the Program “

Cities without slums”.

In 2015, regarding The State of the World Cities Report, United Nations presented the concept of informal settlements:

(…) are residential areas where 1) inhabitants have no security of tenure vis-à-vis the land (…), 2) the neighborhoods usually lack, or are cut off from, basic services and city infrastructure and 3) the housing may not comply with current planning and building regulations and is often situated in geographically and environmentally hazardous areas. (…). [

4] (p.1)

Also, in 2015 the United Nations defined the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) with measures targets to achieve until 2030 and one specific related to cities and human settlements: the SDG 11 – “Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable,” and for water and sanitation, SDG 6 – “Ensure available and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all.” Despite the identification of the principal components of human settlements, the definition of informal settlements, and the obtained achievements, the concept of integrated basic or critical infrastructures seems to be lost.

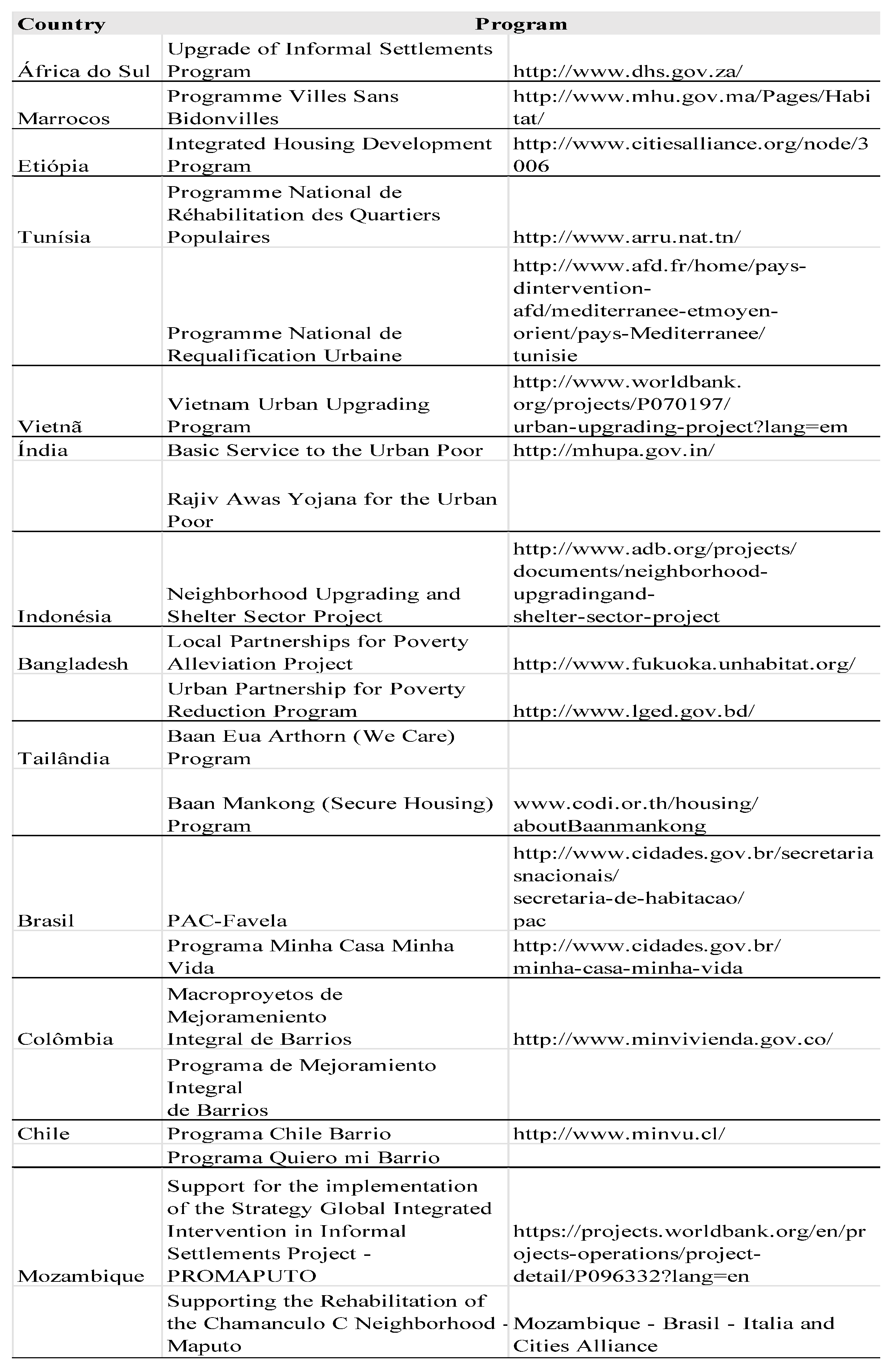

Although between 1976 and today, many issues have changed, the challenge of urbanization is still present, mainly in developing countries. So far, some old issues remain the same, high birth rates, migrations from rural to urban areas, urban planning difficulties, lack of basic infrastructure in informal settlements (e.g., water supply, sanitation, stormwater drainage, solid waste management, electricity supply and mobility). But others appear, namely climate change, violent conflicts, and epidemics. And beside the Program

“Cities without slums” in 2001, many others development urban programs have been applied all around the world in informal settlements, by governments, trust funds and non-governmental organizations and multilateral agencies such as the World Bank, the African Development Bank, The Millennium Challenge Corporation (US MCC), and the Cities Alliance, among others (

Table 1). At this time are being applied to Maputo, four projects all of them related to urban infrastructure:

Maputo Urban Transformation Project (PTUM)

Regenera Project

Mozambique Urban Sanitation Project

Maputo Metropolitan Area Urban Mobility Project

Table 1.

Examples of programs applied in Informal Settlements in different countries.

Table 1.

Examples of programs applied in Informal Settlements in different countries.

Most of the projects ongoing are supported by the World Bank, except

Regenera Project, which is supported by the Italian Cooperation and applied to the neighborhood of Chamanculo C. Some of them are related to previous projects applied. Most programs and projects have an approach to Upgrading Informal Settlements, and have been or will implement basic infrastructures, namely roads, drainage, sanitation, solid waste management, public spaces, and houses, or also, integrated infrastructure. But how has been identified which urban infrastructure should be intervened and why? In a situation of limited financial resources, how do we prioritize infrastructure interventions? How can we ensure this infrastructure will be integrated, sustainable and adapted to population growth, land use and climate change? Is there any interrelationships and interdependencies between these infrastructures? Has already been asked by Schrecongost “

What do we need to learn in order to prioritize interventions that will optimize health and dignity benefits?” [

16] (p.7).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Integrated Infrastructure in Informal Settlements

For Saidi “

Integrated infrastructure systems could be described as a combination of two or more infrastructural systems working with an explicit awareness of one another” [

17]. In most of the documentation analyzed the authors considered infrastructure systems crucial for improving live conditions in informal settlements: water supply and sanitation, electricity, lighting, solid waste management, drainage, roads, [

10,

12,

18]. But also, communication infrastructures [

19,

20]. Besides that, UN- Habitat [

12] highlights that clean drinking water and sanitation and electricity are human rights (life lines). Also, the lack of safe sanitation leads to the contamination of water sources and is also one of the causes of deadly diseases such as cholera and diarrhea. And as mentioned by Chitamba

“according to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), diarrhea caused by unsafe sanitation practices is the third leading cause of death for children under five, with 55% of these deaths directly related to inadequate sanitation practices” [

21]. So, access to clean water and sanitation leads to improved health outcomes, reduced medical expenses, and increased productivity [

18] and human development [

22].

The lack of basic infrastructure is mentioned in the definition of informal settlements [

4] and it is usually mentioned in research related to informal settlements [

10,

18,

19,

20]. The recent research’s also highlights the importance of the maintenance, and the services related to the infrastructure systems [

18,

19,

20,

23]), namely sanitation [

21,

24,

25].

Many projects have been applied to informal settlements in the world with different approach as: i) public house directly provide by the state, ii) site and service schemes, iii) upgrading informal settlements, iv) partnerships scheme for housing access and v) adjustment of building codes and standards [

10]. For Abbott [

26], there is two categories of upgrading informal settlements, one more common applied in Anglo-Saxons language countries, that operate on a sectorial basis, and the objective is addressed to a specific need, for example water supply or housing- this approach works reasonably well in very poor areas where there is little chance of achieving more than the provision of basic needs and where there is little or no relocation of existing dwelling, and don’t change the status of informal settlements. The other is pioneered in Belo Horizonte (Brazil), and it is mostly applied in Latin America. The second approach is based more upon principle for formalizing the settlements and requires modifying the spatial layout of the settlement.

Maputo has two projects that have been applied to the second approach in Chamanculo C and George Dimitroff neighborhood (

Figure 3). In both the decision on infrastructure to intervene as identified by the communities, mostly drainage, roads, and public spaces. In these projects the principles applied were: 1) integrated approach, 2) community participation; and 3) institutional development [

6].

As several methodologies have been defined and applied in the context of urban regeneration of informal settlements, other approaches have also been given to upgrade infrastructure systems, as in the case of the City Wide Inclusive Sanitation (CWIS) (

Figure 4). This new approach to sanitation focuses on the services; that is, infrastructure is one of the parts that help to achieve sanitation services, but the focus is on obtaining the quality of services, including a comprehensive approach to improving sanitation in developing countries and achieving SDG 6 [

16,

21,

25]. In this approach, sanitation services should include concerns with: i) water supply; ii) domestic wastewater; iii) stormwater; iv) fecal sludge management; and solid waste.

The CIWS focuses on the development and maintenance of critical infrastructure, such as water distribution, toilets, latrines/septic tanks/sewerage, wastewater and feacal sludge treatment plants, solid waste management facilities, and stormwater drainage systems [

24]. As mentioned by Chitamba the “

CIWS integrates concerns across multiple sectors and services that have multiple interdependencies” [

21] (pp.37-38).

As we have previously seen, water supply and sanitation, as well as electricity, are human rights, and drainage should be also serving safe sanitation objectives. Regarding sanitation, currently there is evidence that the separation of stormwater drainage and domestic sewage networks (separate sewer systems, typical of some European counties, USA and Canada), despite being more appropriate, have been facing critical challenges in developing countries, in face of the large investments needed and implementation difficulties. Therefore, in situations where there are no sewer networks, on-site sanitation works should be considered, along with traditional drainage systems (sewers and open channels) depending on the part of the city [

21,

27]. Sometimes, a “condominial” or a small gravity sewer system may be implemented, to transport overflows and leachate from existing latrines and septic tanks, and discharging the effluent adequately, using land treatment works and nature-based solutions (such as stabilization ponds or constructed wetlands) with the possibility of connecting later to traditional trunk sewers and to the existing Wastewater Treatment Plant [

27].

Roads in the context of informal settlements are often used to promote the urban integration of these areas and services [

27,

28]. Informal settlements quality of life improves with the integration of other infrastructure such as pipe-borne water, refuse dumps, electricity, streetlights, drainage, and postal addresses [

28].Poor fecal sludge and solid waste management in informal settlements is often related to: i) blocking of drainage systems; ii) contamination of soil and water; iii) spreading of diseases; iii) key contributors to climate change [

29,

30].

Despite the importance of integrated infrastructures in optimizing the health and dignity of the communities in informal settlements, this type of intervention has direct implications for the value of the land [

13] and subsequently increases situations of gentrification. Also, this type of intervention represents a huge financial effort by the government or partner and is non-cost for the beneficiaries. As the land becomes more affordable in areas without basic infrastructure, informal areas and land markets will tend to increase [

31].

Finally, security of land tenure must bring urbanization closer; even in the case of informal settlements, charges must have been associated with urbanization. Urbanization cannot be just the responsibility of the State or Partners. There should be more reflection regarding the distribution of costs associated with urbanization and the installation of integrated infrastructure in informal settlements. Any cost applied to the low-income households can be a challenge, but when this does not happen, more homes tend to be built in areas without basic infrastructure, which are expected to have infrastructure implemented by public authorities.

2.2. Methods

This study is aligned with the definition of a problem in the professional context of implementing an urban intervention project in Maputo, related to integrated critical infrastructures. Although many questions lack answers, the authors try to understand if there is interdependence on urban infrastructure, which can help identify what combination of systems should be prioritized, ensuring infrastructure interventions in informal settlements that optimize the benefits of the applied resources.

In the first step, a bibliography assessment was made, mostly of scientific papers related to urbanization in the world, the challenges of informal settlements, and the contextualization of integrated infrastructures. As the bibliography assessment is ongoing, it was clearer that, in terms of methodology, focuses should be addressed to a case study. So, it was decided to analyze infrastructure data from one neighborhood of Maputo, Inhagoia B, related to: i) stormwater drainage; ii) water supply; iii) sanitation; iii) roads and accessibility; iv) solid waste management; and v) energy. All the secondary data has been collected in Maputo Municipality.

3. Results

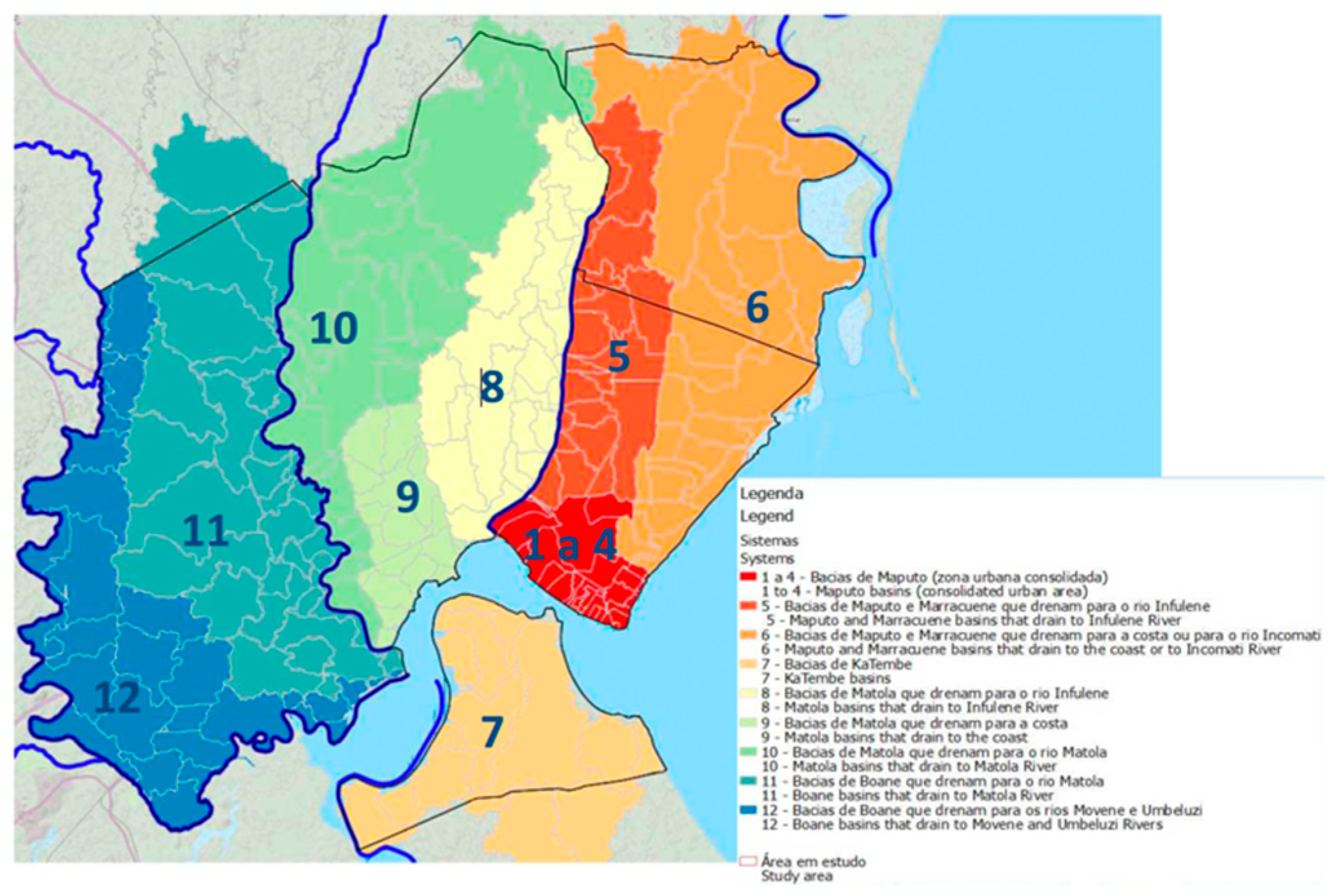

Inhagoia B, an informal settlement in Maputo city, the capital of Mozambique (

Figure 5), has an area of 154 ha and, according to the Census (2017), 15,481 habitants with a density of 101 hab/ha. The Inhagoia B neighborhood (

Figure 6) has been chosen, because it is ranked fourth among the neighborhoods most vulnerable in Maputo (

Figure 7), regarding climate vulnerability, poverty levels and access to infrastructure [

32] and some important data is available.

Regarding drainage aspects: i) there is no structured stormwater or wastewater sewer systems; ii) some natural open channels exist, but there are common flooding areas, and soil erosion associated with floods (

Figure 8). There is a wastewater collector next to the neighborhood with a connection to the Infulene WWTP, however it does not serve the neighborhood (

Figure 9). All the stormwater drains in Inhagoia B area discharging into the Infulene valley [

33], close to fertile agricultural land, used to produce crops by the local population.

Inhagoia B is served by a water supply network, in an intermittent way, but some households have water supply provided by private boreholes (

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12). Despite the existing water supply network, few households have water inside their homes, most of them have a connection in the backyard.

Inhagoia B do not have a wastewater collection system, and the sewer trunk that runs alongside the neighborhood only serves consolidated areas (

Figure 9, orange line).

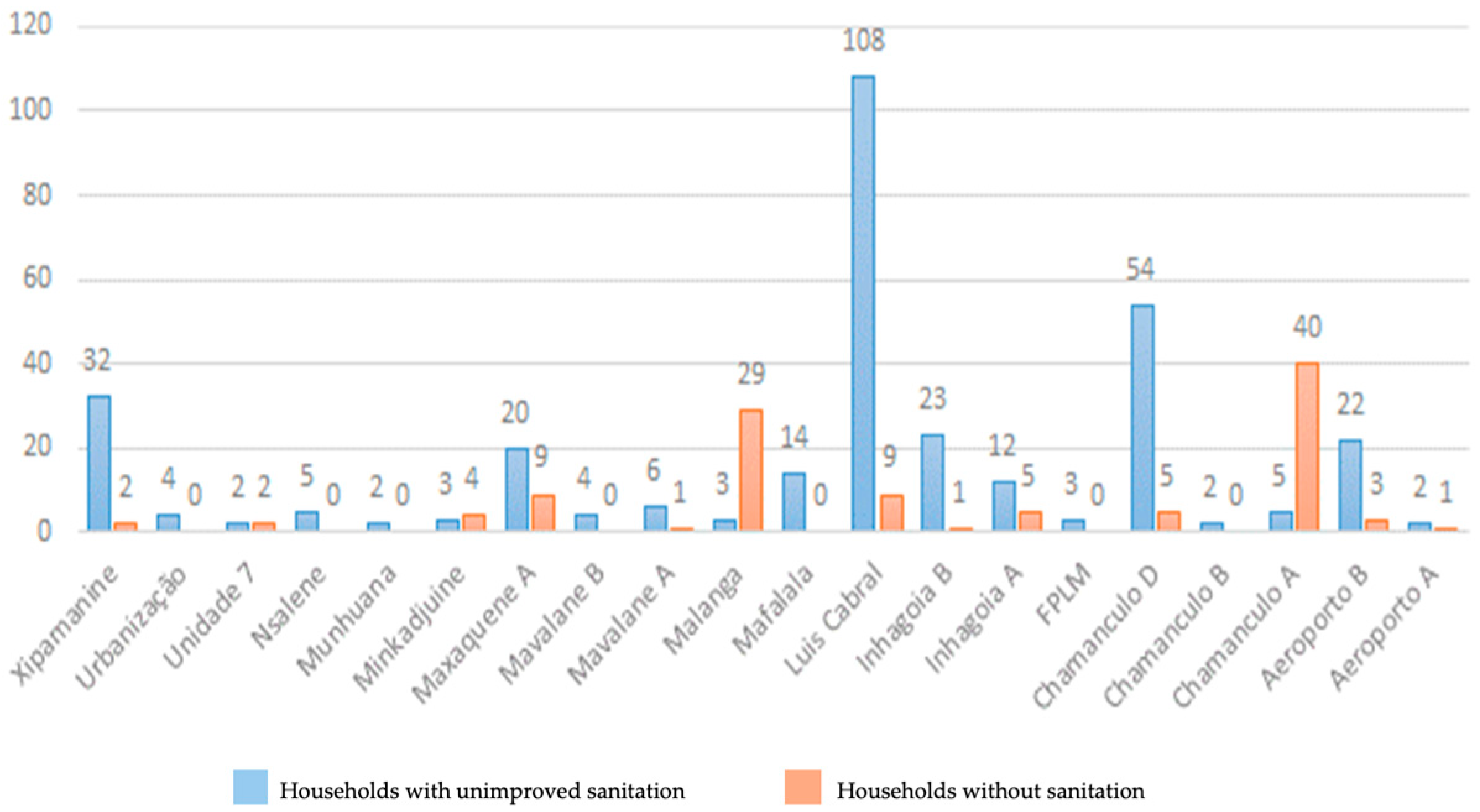

Most of the households have improved latrines and lavatory facilities without flushing (

Figure 13), but there are still cases of households without access to improved sanitation (

Figure 14). To the west of the neighborhood, the water table is high, and the latrines fill up very quickly. When this happens, families close the latrine and open another one if space is available.

In areas accessible to the suction truck, sludge collection is carried out by private operators (

Figure 15). However, due to the distance to the Infulene WWTP, a ponding system recently expanded and rehabilitated, the fecal sludge is often discharged into open areas close to the on-site works.

In most inaccessible areas, the latrines are emptied by individuals that provide this type of service, or by the user’s using buckets, being the sludge typically buried in backyards. Sometimes the fecal sludge is dumped into drainage ditches or placed in bags and left in solid waste containers [

33].

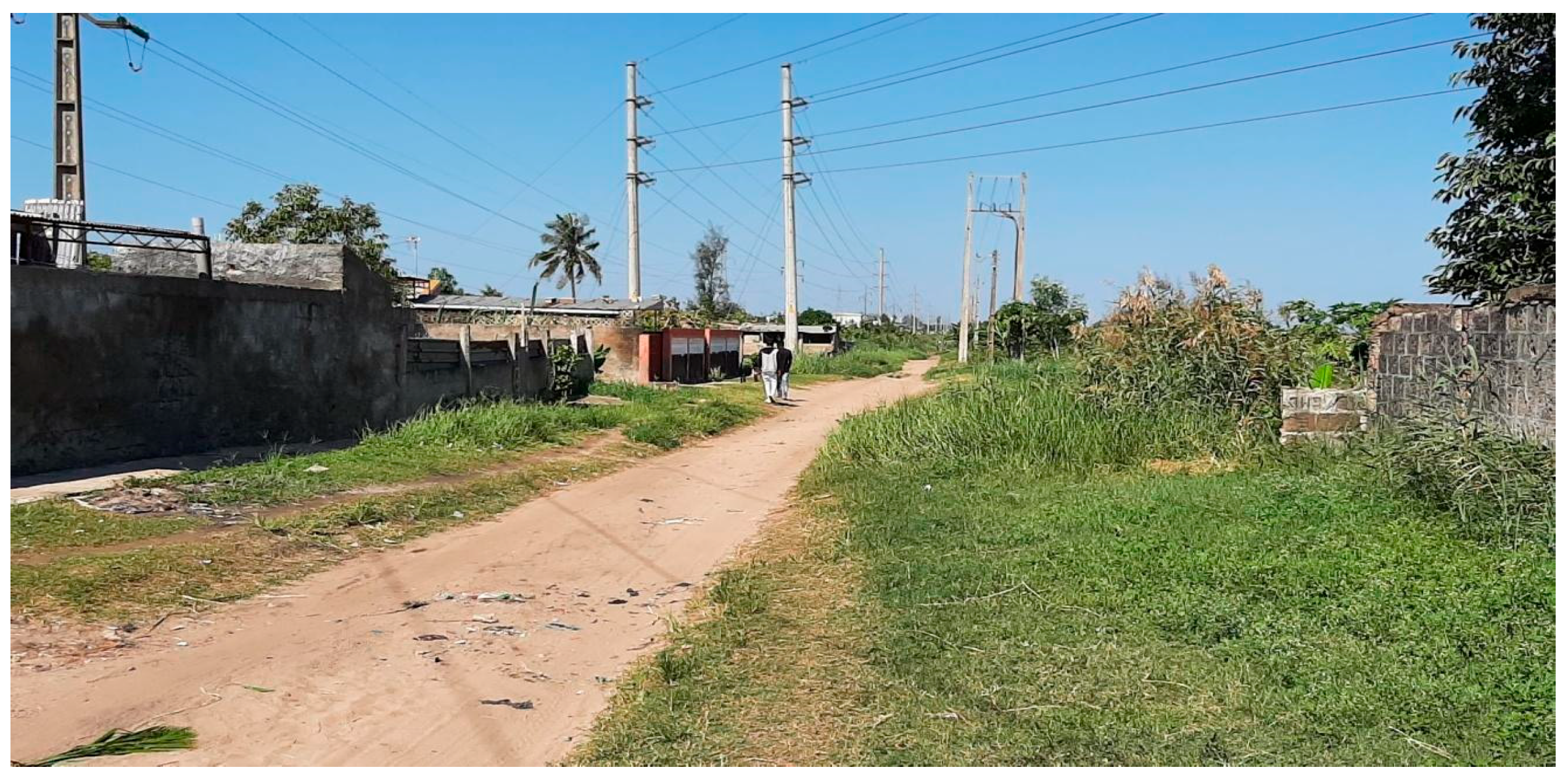

Inhagoia B is one of the neighborhoods with a lack of internal connectivity and a formal road network. The existing roads are not paved (

Figure 17), have varied and winding profiles, and in some situations only pedestrians can circulate [

33].

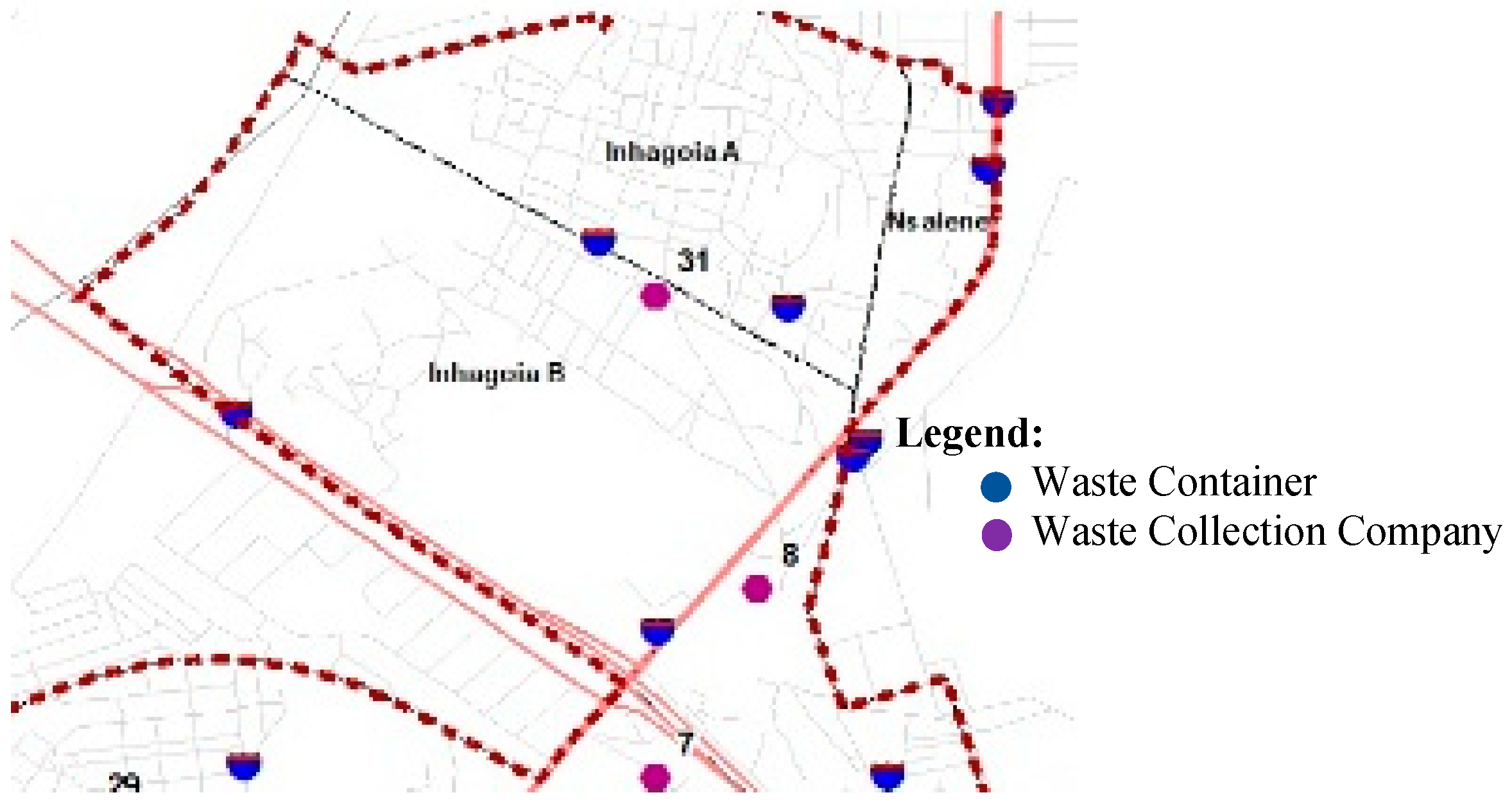

Solid waste management is still a major challenge due to limitations in terms of financial and human resources. Inhagoia B has three solid waste containers (

Figure 18), but one of these is shared with Inhagoia A.

Solid waste collection is carried out for the first time by local associations and micro-enterprises, contracted by the Municipality, which carry out primary door-to-door collection using hand trucks called “tchovas” and then deposit the solid waste in the containers (

Figure 19).

Afterward, collection is carried out in containers by companies that transport the waste to the Hulene dump, nearby. The amount that supports the costs of waste collection is paid by the population in the process of using energy on the first recharge of the month. Subsequently, EDM transfers this value to the Municipality's funds [

33].

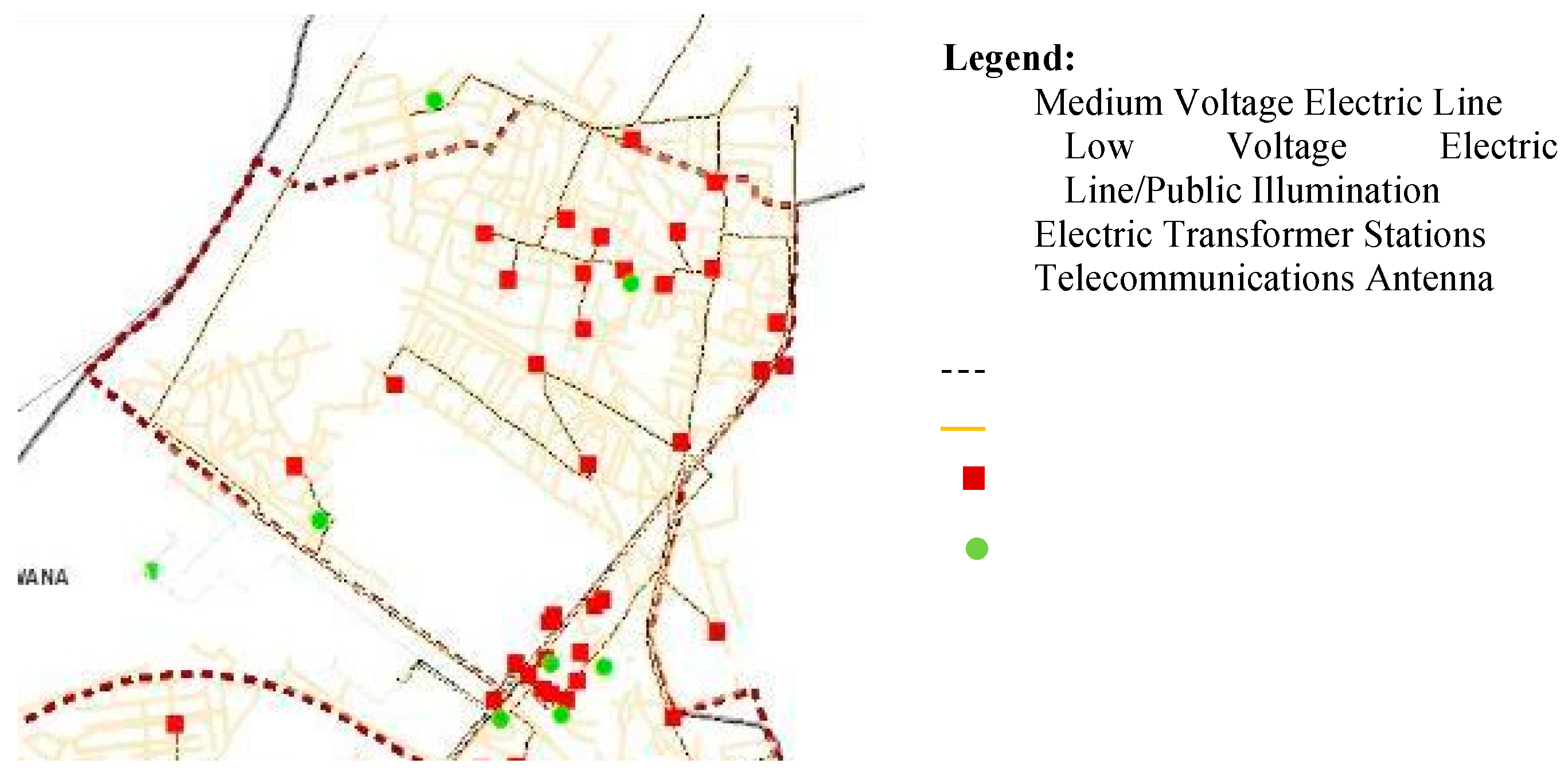

The electrical network (

Figure 20 and

Figure 21) covers the entire neighborhood, and is also crossed by corridors of electrical infrastructures, which combine high and medium voltage, namely the lower area of the Infulene River, which coincides with the Neighborhoods of Inhagoia A and B.

According to the “Master Plan for Sanitation and Drainage of the Greater Maputo Area” [

35], the Inhagoia B neighborhood is in System 5 (

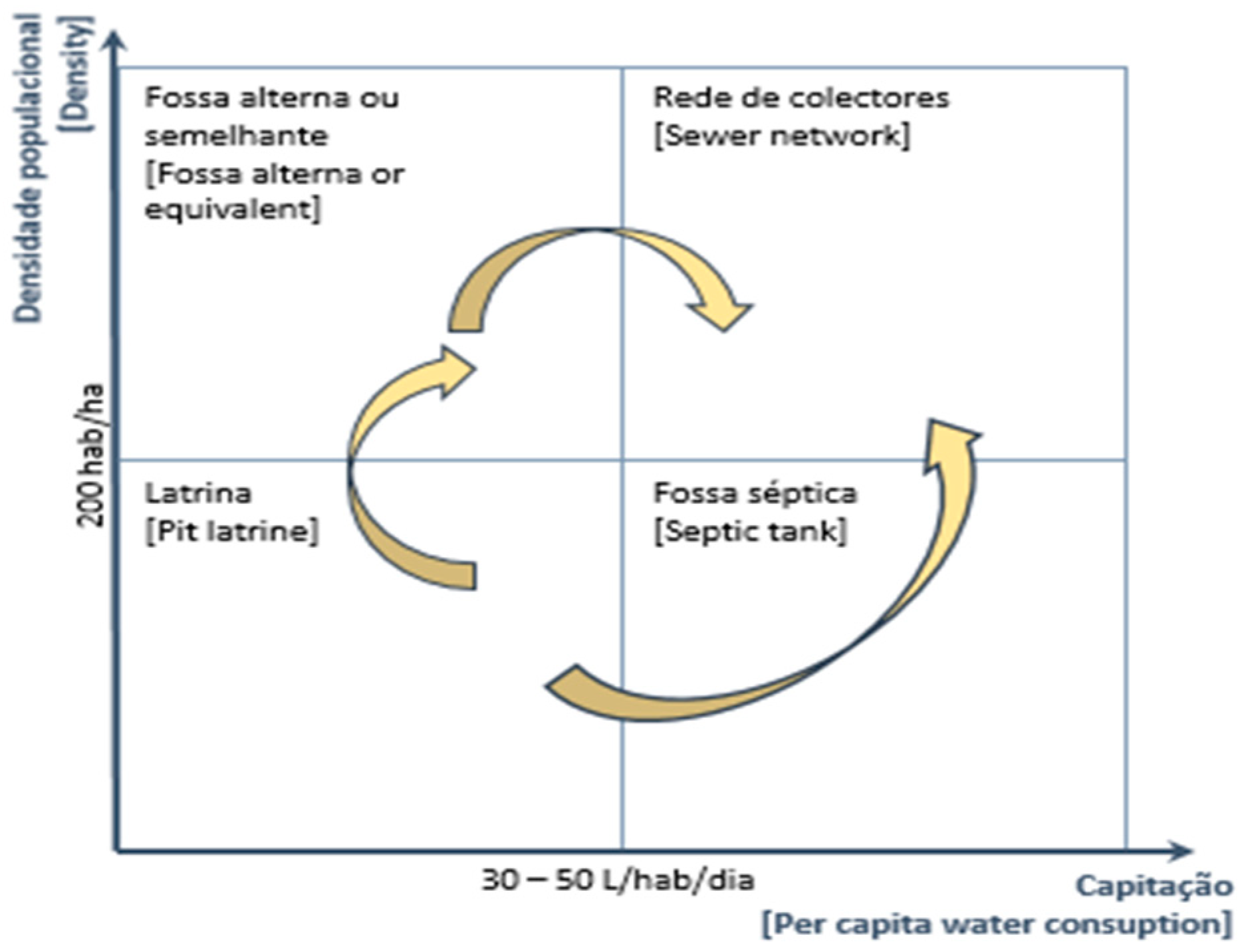

Figure 22), for which it is proposed to build open channels to collect rainwater to be discharged at Infulene River and two fecal sludge transfer stations. Sanitation solutions must consider, among other factors, population density and per capita water consumption (

Figure 23), as well as the various potential types of sanitation technologies (

Figure 24).

4. Discussion

So, regarding the research’s analysis, the following main reflections can be outlined:

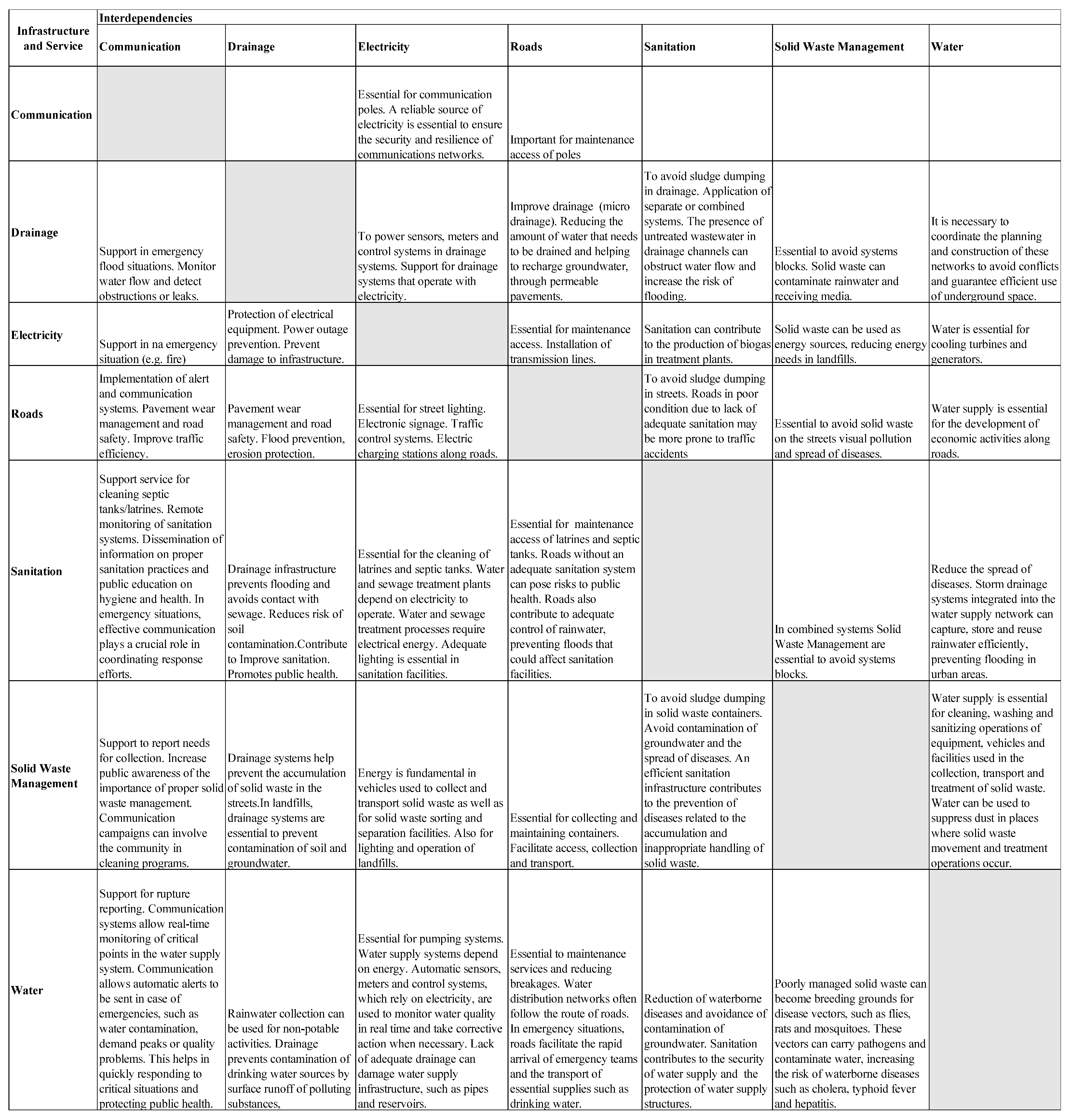

All the authors seem to agree that, in general, in informal settlements lack basic infrastructures, and the priorities intervention should focus on water supply, sanitation, stormwater drainage, roads, solid waste management and electricity. Some of the authors refer also communication lines.

Water supply and sanitation are human rights and “lifelines”, crucial for human development.

Few research studies analyze the interventions on informal settlements, covering the different types of infrastructures and its interdependencies in an integrated way; most studies focus on a specific type of infrastructure.

Little research identifies and explore the interactions among different critical sectors.

When the studies report on integrated infrastructures, commonly water and sanitation, and sometimes electricity and solid wastes came together.

Sanitation solutions need to be aligned with other services, to be effective. The sanitation solution depends mainly on the water per capita consumption and on population density, among other factors, such as depth of water table, soil permeability, and social culture and uses.

Solid waste management should be considered to ensure adequate functioning of stormwater channels and domestic drainage systems.

Reliable electricity supply is needed namely for pumping systems.

Good accesses and easy mobility are required for emptying latrines, particularly in crowded informal areas.

The intervention in infrastructures should be aligned with better land use and urbanization, to satisfy the goal of reducing poverty, and namely fulfill SDG 6 and SDG 11.

The interventions in informal settlements should be done in articulation with procedures regarding land tenure security, and a fair distribution of associated costs.

Regarding the infrastructure at Inhagoia B:

Most of the households have latrines, which fill very quickly because the water table is high. Under rainfall situations, and without a drainage system, all the leachate goes to natural open channels and to the Infulene valley contaminating the soil and the crops with associated health risks.

When latrines are full, two situations occur: i) in a situation of available space, the households close the latrine and open another one nearby; ii) when no space is available, households shall emptying the latrines using a bucket or ask some professional to do it (and pay). The fecal sludge is deposited near the house's backyard, and in some situations, close to private boreholes.

The roads are not paved, and some areas are not accessible for fecal sludge collection.

Because there is not a formal drainage network, when it rains some overflows may occur from latrines and septic tanks, and the polluted stormwater tends to run down the land, and some areas suffer from erosion.

The erosion in some areas makes it difficult to maintain basic infrastructures, namely water pipes, and sewers, and energy and communication lines.

The water network mostly follows the roads; however, as roads are unpaved, they often break and suffer from leakage.

Sanitation solutions to be selected should consider namely the population density, the per capita water consumption, and the accessibility, among other factors.

From the research and the case study, it is possible to verify that critical infrastructures in informal settlements have significant interdependencies (

Table 2), that can help to prioritize the interventions. Also, regarding

Table 2, the sanitation has a major importance. Sanitation is key to public health, but: i) its effectiveness depends on intervention in other sectors; ii) intervention in other sectors bring implications and other challenges to sanitation solutions; iii) intervention on roads brings gains to almost all other critical infrastructures.

An integrated infrastructure approach, can generate positive and negative impacts, for example:

Combination of sanitation and drainage may improve the environmental conditions and the quality of life in informal settlements. As said, any overflow in latrines and septic tanks can be transported downstream by a combination of simplified sanitation techniques and drainage systems. There will be less stagnant water in the streets and backyards, a reduction in the proliferation of mosquitoes, in diarrheal diseases, and in the contamination of soils and aquifers.

An intervention that improves water supply will increase the number of sanitation techniques that use water. If there is no intervention in the sanitation system, overflows from pits and tanks will increase dramatically, aggravating the proliferation of diseases and contamination of the water table, because water acts as an agent for pathogenic microorganisms spreading. It means if public water is supplied with no restrictions in dense urban areas, a wastewater centralized system, with sewers and WWTP, shall be implemented- local pits and septic tanks are no more sustainable solutions. An intermediate hybrid solution may be to implement a simplified sewer systems (condominium sewers or small diameter gravity sewer systems) conveying the effluent and overflows from septic tanks to a nearby ditch or stormwater drainage channel. This effluent is primarily treated in the septic tanks, with organics and suspended solids removal, and will be transported to receiving waters through these channels, being diluted under wet climate.

If a conventional stormwater drainage is planned, with sewers and channels, the implementation of paved roads may be relevant to avoid soil erosion, and pos-sedimentation, and contributing to sewer degradation and collapses. Clandestine connections between individuals’ sanitation systems and the environment, and contamination of stormwater with leachate will be present if an appropriate sanitation system will not be implemented at the same time.

For the success of the interventions, it is highly recommended the implementation at the same time of sanitation and stormwater drainage infrastructures, and paved roads.

Specifically, for Inhagoia B, it is recommended for the areas with formal water supply, jointly interventions on roads, small gravity sewers (after the septic tanks) and open drainage channels. A fecal sludge chain of services approach should be recommended for areas without formal sanitation e.g. depending on dry sanitation (collection, storage, transport and sludge treatment at anaerobic ponds and drying beds at the Infulene WWTP.

5. Conclusions

The main conclusions of the work were the following ones:

Roads have an accessibility function but also support the maintenance of the main critical urban services.

Intervention in sanitation needs a more systemic approach regarding the interdependencies with other infrastructure and services, mostly stormwater drainage and solid waste management.

Combining stormwater drainage and sanitation interventions, result in an opportunity to improve significantly health conditions and reduce deadly diseases.

Sanitation solutions should be defined considering the main characteristics of the area namely, among others, the population density, the water consumption, the climate, the average income and the accessibility.

The implementation of critical infrastructures in the Inhagoia B neighborhood case study justify, as priorities, urgent investments on sanitation, stormwater drainage, and roads.

In the areas with no formal water supply, a chain of services, including adequate equipment, sludge transfer stations and human and financial resources should be a priority.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C.; methodology, S.C and J.S.M.; software, S.C.; validation, S.C. and J.S.M.; formal analysis, S.C.; investigation, S.C.; resources, S.C; data curation, S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C. and J.S.M..; writing—review and editing, S.C., J.S.M. and F.F.; visualization, S.C.; supervision, J.S.M and F.F; project administration, S.C.; funding acquisition, S.C.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the first author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- UNFPA – United Nations Population Fund. Available online: www.unfpa.org/urbanization (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- Carrilho, J., Coelho, A.B., Palma, N. (2014). Que Arquitectura nos Países em Desenvolvimento?. Escolar Editora.

- United Nations (2023). The Sustainable Development Goals Report, Special edition. United Nations.

- United Nations (2015). Habitat III Issue Papers (22 – Informal Settlements). New York, United Nations.

- Gama, J. (2016). Géneses e Transformações de Áreas Urbanas Informais: Os casos de São Paulo, Luanda e Istambul (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade de Lisboa, Instituto Superior Técnico.

- CMM (2016). Manual de Intervenção Integrada em Assentamentos Informais. Maputo, Conselho Municipal de Maputo.

- Quesada-Román, A. (2022). Disaster Risk Assessment of Informal Settlements in the Global South. Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Ohlendorf, L. (2009). Climate change, vulnerability, and adaptation in Sub-Saharan African cities: new challenges for development policy (Discussion paper No. 25/2009). Bonn: Deutsches Institut fur Entwicklungspolitik. ISBN 978-3-88985-475-9.

- Satterthwaite, D., Archer, D., Colenbrander, S., Dodman, D., Hardoy, J.E., Mitlin, D., & Patel, S. (2020). Building Resilience to Climate Change in Informal Settlements. One Earth. [CrossRef]

- Amado, M., Ramalhete, I., Amado, A.R., & Freitas, J.C. (2016). Regeneration of informal areas an integrated approach. Cities, 58, 59-69. [CrossRef]

- GSG (2022). Informal Settlements Report. UK: Global Steering Group for Impact Investment.

- UN- Habitat (2022). Slum Upgrading Legal Assessment Tool. United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

- World Bank (2017). Análise da Urbanização em Moçambique: Aceleração da Urbanização em Apoio à Transformação Estrutural em Moçambique (Relatório Nº AUS15538). Mozambique – Country Management Unit.

- United Nations (1976). Report of Habitat: United Nations Conference on Human Settlements. New York: United Nations.

- Forjaz, J. , Carrilho, J., Laje, L., Mazembe, A., Nhachungue, E., Battino, L., Costa, M., Cani, A., Trindade, C. (2006). Moçambique, Melhoramento dos Assentamentos Informais, Análise da Situação & Proposta de Estratégias de Intervenção. (C. Trindade & M. Costa, Eds). Direcção Nacional de Planeamento e Ordenamento Territorial.

- Schrecongost, A., Pedi, D., Rosenboom, JW., Shrestha, R., and Ban, R. (2020) Citywide Inclusive Sanitation: A Public Service Approach for Reaching the Urban Sanitation SDGs. Front. Environ. Sci. 8:19. [CrossRef]

- Saidi, S., Kattan, L., Jayasinghe, P., Hettiaratchi, P., Taron, J. (2018). Integrated infrastructure systems—A review, Sustainable Cities and Society, Volume 36, 2018, Pages 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Parikh, P., Parikh, H., McRobie, A. (2012). The role of infrastructure in improving human settlements. [CrossRef]

- Arimah, B. (2017). Infrastructure as a Catalyst for The Prosperity of African Cities. ScienceDirect. [CrossRef]

- Roelich, K., Knoeri, C., Steinberger, J.K., Varga, L., Blythe, P.T., Butler, D., Gupta, R., Harrison, G.P., Martin, C.J., & Purnell, P. (2015). Towards resource-efficient and service-oriented integrated. [CrossRef]

- Chitamba, H., Catiola, M., Alves, L., Saldanha, J.M. (2023). Nota Técnica, Saneamento inclusivo à escala da cidade – uma abordagem integrada e alternativa à abordagem convencional de sistemas de saneamento. Águas & Resíduos, IV.12, 34-24. [CrossRef]

- Tilley, E., Ulrich, L., Lüthi, C., Reymond, P., & Zurbrügg, C. (2014). Compendium of sanitation systems and technologies.

- Muñiz, E., Jeyaraj, E.J., Button, K.M., & Ma, R.I. (2010). Adapting Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems to Stormwater Management in an Informal Setting. infrastructure operation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 92, 40-52.

- Ramôa, A. (2018). Planning Guiding Principles for improving sanitations urban areas of developing countries – case study application in Maputo (Tese de Doutoramento publicada), Universidade de Lisboa.

- WSP (2010). Marching Together with a Citywide Sanitation Strategy. Water and Sanitation Program.

- Abbott, J. (2000). An Integrated Spatial Information Framework for Informal Settlements Upgrading. International Archives of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Vol. XXXIII, Part B2.

- Magalhães, F., Di Villarosa, F. (Ed.) (2012). Urbanização de Favelas, Lições Aprendidas no Brasil. Banco Interamericano de Desenvolvimento.

- Iliya, S., & Gürdallı, H. (2020). A Sustainable Governmental Intervention Policy for Slum Upgrading: Road Infrastructure in Railway Down Quarter, Kaduna, Nigeria. European Journal of Sustainable Development, 9, 581. [CrossRef]

- Cities Alliance (2020). Solid Waste Management in the Global South. Cities Alliance. Issue Brief 03.

- UNICEF (2021). Waste Management in Informal Settlements, Challlenges, Opportunities and Strategic Pathways Forward. Link.

- Guevara, N. (2014). Informality and Formalization of Informal Settlements at the Turn of the Third Millennium: Practices and Challenges in Urban Planning. Journal of Studies in Social Sciences. Volume 9, Number 2, 247-299. ISSN 2201-4624.

- Fraym (2020). Updated Findings for the Maputo Informal Settlements Improvement Strategy. Municipal Council of Maputo and World Bank.

- CMM (2021). Diagnóstico Integrado da Componente 1: Melhoria Integrada dos Assentamentos Informais. Conselho Municipal de Maputo.

- Nippon Koei Mozambique/Engidro/AgriPro Ambiente (2022). Validação do Diagnóstico Integrado da Componente 1. Conselho Municipal de Maputo.

- ENGIDRO/HIDRA/AQUAPOR (2015). Plano Director de Saneamento e Drenagem da Área Metropolitana de Maputo.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).