Submitted:

01 September 2024

Posted:

02 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Amyloid-β Protein Preparation

2.2. Ligands Selection

2.3. In Silico ADME Screening

2.4. Active site-Targeted Molecular Docking of Flavonoids

2.5. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Studies

2.6. Density Functionality Theory (DFT)

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Binding Site Identification

3.2. Active Molecules and Their Structures

3.3. In Silico ADME Screening

3.4. Molecular Docking

3.5. Interpretation of Ligands-Amyloid-β Fibrils Interactions

3.6. MD Simulation Studies

3.7. DFT Studies

4. Conclusion

Funding

Acknowledgments

Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

References

- Atri A. The Alzheimer’s disease clinical spectrum: diagnosis and management. Medical Clinics 2019; 103: 263-293. [CrossRef]

- Harris PB. The person with Alzheimer's disease: Pathways to understanding the experience. JHU Press; 2002.

- Rajeshkumar RR, Kumar BK, Parasuraman P, Sundar K, Ammunje DN,. Pandian SRK, Murugesan S, Kabilan SJ, Kunjiappan S. Graph theoretical network analysis, in silico exploration, and validation of bioactive compounds from Cynodon dactylon as potential neuroprotective agents against α-synuclein. BioImpacts: BI 2022; 12: 487. [CrossRef]

- Rajmohan R, Reddy PH. Amyloid-beta and phosphorylated tau accumulations cause abnormalities at synapses of Alzheimer’s disease neurons. J Alzheimer's Dis 2017; 57: 975-999. [CrossRef]

- van der Kant R, Goldstein LS, Ossenkoppele R. Amyloid-β-independent regulators of tau pathology in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 2020; 21: 21-35. [CrossRef]

- Bignante EA, Heredia F, Morfini G, Lorenzo A. Amyloid β precursor protein as a molecular target for amyloid β–induced neuronal degeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 2013; 34: 2525-2537. [CrossRef]

- Butterfield DA, Swomley AM, Sultana R. Amyloid β-peptide (1–42)-induced oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease: importance in disease pathogenesis and progression. Antioxidants Redox Signal 2013; 19: 823-835. [CrossRef]

- Michaels TC, Šarić A, Curk S, Bernfur K, Arosio P, Meisl G, Dear AJ, Cohen SI, Dobson CM, Vendruscolo M. Dynamics of oligomer populations formed during the aggregation of Alzheimer’s Aβ42 peptide. Nat Chem 2020; 12: 445-451. [CrossRef]

- Barucker C, Bittner HJ, Chang PK-Y, Cameron S, Hancock MA, Liebsch F, Hossain S, Harmeier A, Shaw H, Charron FM. Aβ42-oligomer Interacting Peptide (AIP) neutralizes toxic amyloid-β42 species and protects synaptic structure and function. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 15410. [CrossRef]

- Salahuddin P, Khan RH, Furkan M, Uversky VN, Islam Z, Fatima MT. Mechanisms of amyloid proteins aggregation and their inhibition by antibodies, small molecule inhibitors, nano-particles and nano-bodies. Int J Biol Macromol 2021; 186: 580-590. [CrossRef]

- Jakhria TC. Amyloid fibrils are nanoparticles that target lysosomes. University of Leeds; 2014. eThesis id: uk.bl.ethos.638882.

- Gupta S, Dasmahapatra AK. Lycopene destabilizes preformed Aβ fibrils: Mechanistic insights from all-atom molecular dynamics simulation. Comput Biol Chem 2023; 105: 107903. [CrossRef]

- Stefani M, Rigacci S. Protein folding and aggregation into amyloid: the interference by natural phenolic compounds. Int J Mol Sci 2013; 14: 12411-12457. [CrossRef]

- Kunjiappan S, Pandian SRK, Panneerselvam T, Pavadai P, Kabilan SJ, Sankaranarayanan M. Exploring the Role of Plant Secondary Metabolites for Aphrodisiacs. In: Plant Specialized Metabolites: Phytochemistry, Ecology and Biotechnology. Springer; 2023: 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Sawicka B, Ziarati P, Messaoudi M, Agarpanah J, Skiba D, Bienia B, Barbaś P, Rebiai A, Krochmal-Marczak B, Yeganehpoor F. Role of Herbal Bioactive Compounds as a Potential Bioavailability Enhancer for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients. In: Handbook of Research on Advanced Phytochemicals and Plant-Based Drug Discovery. IGI Global; 2022: 450-495. [CrossRef]

- Ullah A, Munir S, Badshah SL, Khan N, Ghani L, Poulson BG, Emwas AH, Jaremko M. Important flavonoids and their role as a therapeutic agent. Molecules 2020; 25: 5243. [CrossRef]

- Sun X, Chen W-D, Wang Y-D. β-Amyloid: the key peptide in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Pharmacol 2015; 6: 221. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Su B, Perry G. Smith MA, Zhu X. Insights into amyloid-β-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. Free Radic Biol Med 2007; 43: 1569-1573. [CrossRef]

- Dajas F, Rivera-Megret F, Blasina F, Arredondo F, Abin-Carriquiry J, Costa G, Echeverry C, Lafon L, Heizen H, Ferreira M. Neuroprotection by flavonoids. Braz J Med Biol Res 2003; 36: 1613-1620. [CrossRef]

- Pritam P, Deka R, Bhardwaj A, Srivastava R, Kumar D, Jha AK, Jha NK, Villa C, Jha SK. Antioxidants in Alzheimer’s disease: Current therapeutic significance and future prospects. Biology 2022; 11: 212. [CrossRef]

- Calderaro A, Patanè GT, Tellone E, Barreca D, Ficarra S, Misiti F, Laganà G. The neuroprotective potentiality of flavonoids on Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Mol Sci 2022; 23: 14835. [CrossRef]

- Palanichamy C, Pavadai P, Panneerselvam T, Arunachalam S, Babkiewicz E, Ram Kumar Pandian S, Shanmugampillai Jeyarajaguru K, Nayak Ammunje D, Kannan S,. Chandrasekaran J, Kunjiappan S. Aphrodisiac performance of bioactive compounds from Mimosa pudica Linn.: In silico molecular docking and dynamics simulation approach. Molecules 2022; 27: 3799. [CrossRef]

- Mohanraj K, Karthikeyan BS, Vivek-Ananth R, Chand RB, Aparna S, Mangalapandi P, Samal A. IMPPAT: A curated database of Indian Medicinal Plants, Phytochemistry And Therapeutics. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 4329. [CrossRef]

- Duke JA. Dr. Duke's phytochemical and ethnobotanical databases. 1994.

- Wu D, Chen Q, Chen X, Chen, Han F, Chen Z, Wang Y. The blood–brain barrier: structure, regulation, and drug delivery. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023; 8: 217. [CrossRef]

- Kuntz CP. Molecular Mechanisms of Ligand Recognition by the Human Serotonin Transporter: A Molecular Modeling Approach. Purdue University; 2015.

- Espinosa JR, Wand CR, Vega C, Sanz E, Frenkel D. Calculation of the water-octanol partition coefficient of cholesterol for SPC, TIP3P, and TIP4P water. J Chem Phys 2018; 149. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y. Novel theoretical analysis methods and algorithms for classical and ab initio molecular dynamics. New York University; 2002. [CrossRef]

- Kim M, Kim E, Lee S, Kim JS, Lee S. New method for constant-NPT molecular dynamics. J Chem Phys Chem A 2019; 123: 1689-1699. [CrossRef]

- Ghosal A, Roy AK. DFT calculations of atoms and molecules in Cartesian grids. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Kumar A, Srivastava S, Tripathi S, Singh SK, Srikrishna S, Sharma A. Molecular insight into amyloid oligomer destabilizing mechanism of flavonoid derivative 2-(4′ benzyloxyphenyl)-3-hydroxy-chromen-4-one through docking and molecular dynamics simulations. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2016; 34: 1252-1263. [CrossRef]

- Gupta S, Dasmahapatra AK. Destabilization potential of phenolics on Aβ fibrils: Mechanistic insights from molecular dynamics simulation. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2020; 22: 19643-19658. [CrossRef]

- Fahim AM, Farag AM. Synthesis, antimicrobial evaluation, molecular docking and theoretical calculations of novel pyrazolo [1, 5-a] pyrimidine derivatives. J Mol Struct 2020; 1199: 127025. [CrossRef]

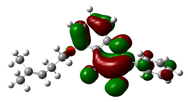

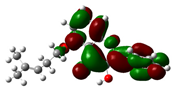

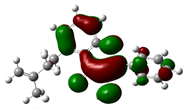

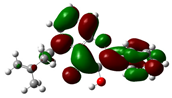

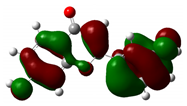

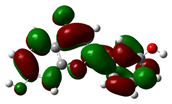

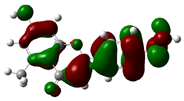

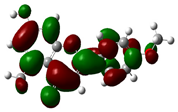

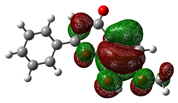

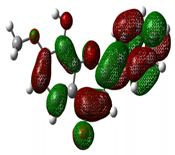

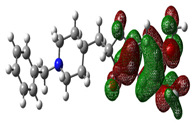

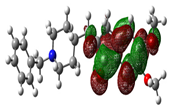

| Compound Name | HOMO | EHOMO (ev) | LUMO | ELUMO (ev) | Energy gap (Δev) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prenylmethoxy flavonol |

|

-8.578 |

|

-5.828 | 2.750 |

| Isopentenyl flavonol |  |

-8.604 |  |

-5.917 | 2.687 |

| 7,3'-Dihydroxyflavone |  |

-9.285 |  |

-5.880 | 3.404 |

| 7-Hydroxy-5-methyl-4'-methoxyflavone |

|

-8.771 |  |

-5.654 | 3.117 |

| 8-hydroxy-7-methoxyflavone |

|

-8.515 |  |

-5.850 | 2.665 |

| Donepezil |  |

-8.794 |  |

-5.667 | 3.127 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).