1. Introduction

In late XX century scientific literature has been becoming increasingly inaccessible due to growing subscription costs, leading to a crisis in scholarly communication system [

1]. At the same time, information technologies have seen a rapid breakthrough with the emergence of modern Internet and World Wide Web, giving rise to a hope that the crisis will be resolved soon by a complete transformation of research communication system, bringing forth a future where information published in scientific journals and books will become accessible online to every person completely free of charge [

2]. That served as a foundational idea behind ‘free online scholarship’ movement, that was steadily growing among librarians and researchers during 90s. The movement later became officially known as ‘open access movement’ after the BOAI declaration signed in 2001: the document emphasized the need for removing access barriers to scientific knowledge, making publications in peer-reviewed academic journals

open access, or freely accessible online ‘without financial, legal, or technical barriers’ [

3].

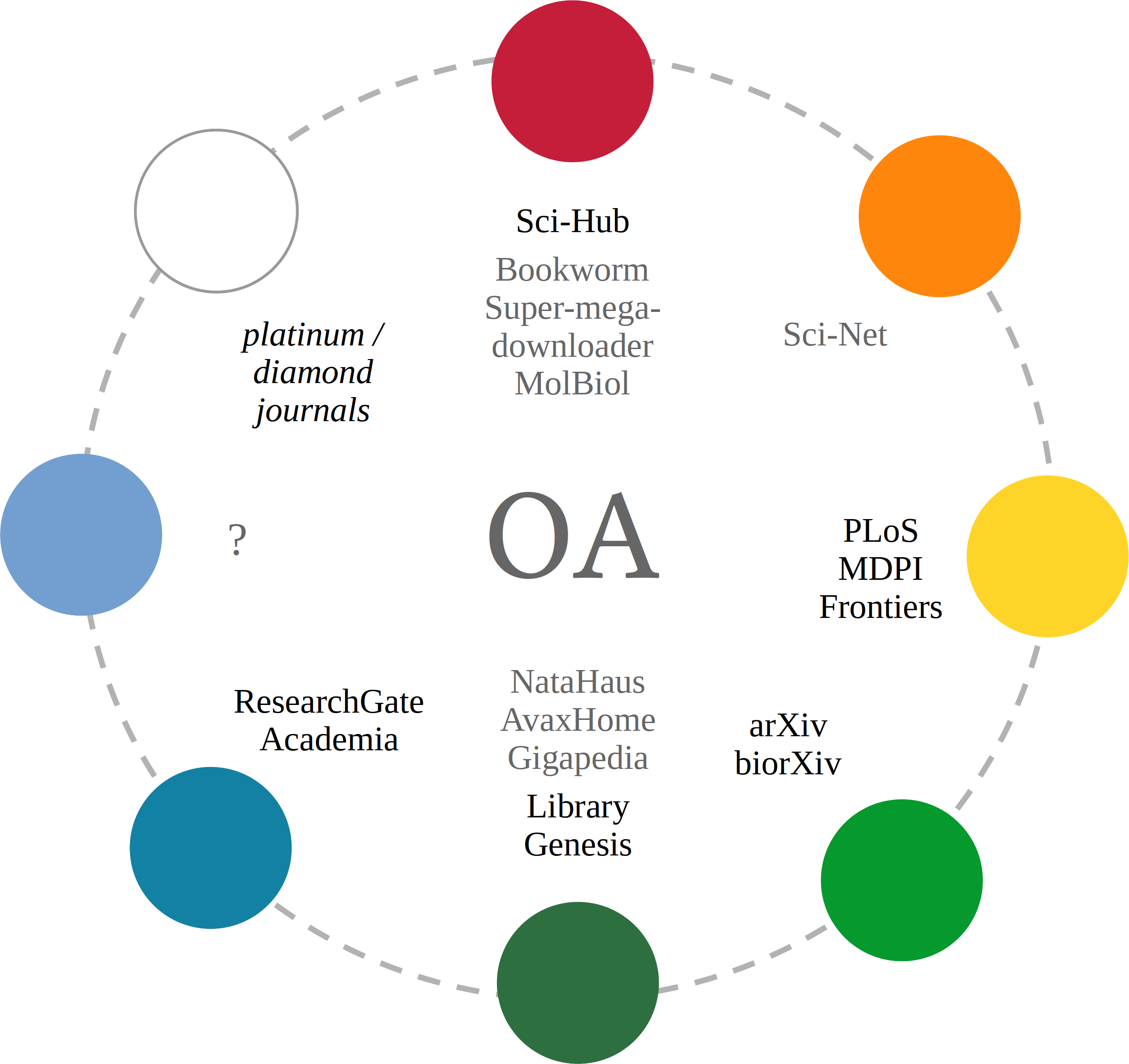

Since 2001, an active debate is ongoing in the academic literature on the topic of open access. In this discussion, the following categories of open access projects have been mentioned: green, gold, platinum or diamond, gratis and libre, bronze, hybrid, guerilla and black. These categories are by no means equal: while green and gold approaches are considered classic and have been discussed in many publications, other categories such as gratis/libre and bronze OA were proposed by a prominent researchers, but remain scarcely used. The present article will attempt to critically analyze categories that currently provide a theoretical framework for discussions on open access, with especial emphasis on black OA. Even though there were some studies published on the topic of black open access [

4] the exploration has been so far cursory and available information is fragmented, often containing inaccuracies and factual errors. As a result this type of open access remains poorly understood and largely neglected in the literature, despite having a large impact on research practice. There is a need for a more detailed and comprehensive exploration of black open access, that will be provided in this article.

I will start by briefly describing those approaches for implementing open access that can be considered classic: green, gold and diamond. I will then analyze gratis, libre and bronze OA and show how these categories address a completely different, legal dimension of open access. I will then turn to black open access and describe its historical development and impact, identifying four different types of projects in this area: (a) classical shadow libraries, (b) literature-sharing communities, (c) automatic paywall circumvention tools i.e., Sci-Hub and (d) academic social networks. I then propose the following categories of open access: red, green and blue to illustrate the rich diversity of black open access landscape.

2. Classic Approaches: Green, Gold and Diamond OA

The Budapest declaration of 2001 outlined two general approaches, or pathways towards implementing open access: self-archiving and publishing in an open journals. However, by that time both self-archiving and publishing in OA journals have been already practiced by scientific community for many years. Even though the percentage of open access publications remained relatively small compared to all research output, the BOAI declaration did not propose novel ideas, but merely codified and legitimized already existing practices.

The history of self-archiving can be traced back to the arXiv project created by P. Ginsparg in 1991 [

5]. The project was build upon a tradition of circulating preprints (i.e., draft versions of papers) by email before publication within the community of high-energy physics researchers. ArXiv was started as an electronic mail server that enabled a more convenient distribution of preprints, later evolving into a web site with a functionality for any researcher to upload preprints and make them available to readers completely free of charge [

6].

The idea of self-archiving was that all researchers should start depositing their work in publicly accessible online Internet repositories, or archives. That approach was named ‘green’ open access, probably after similarity to ‘grass-roots’ movements. Widely adopted, the practice of green self-archiving could potentially render traditional research journals obsolete, so the idea was initially perceived as highly controversial and subversive [

7].

Establishing new open access journals, that are not funded by subscriptions and therefore are completely free to read, was an alternative that could potentially provide a much smoother transition to open access compared to self-publishing. First online electronic scholarly journals that are free to read started to appear as early as in 1989 [

8]; by 1996 the number of such journals in circulation was estimated to be from 77 to 115 [

9]. These publications were non-commercial and the majority of them were funded by institutions.

Unfortunately, these early attempts did not succeed to become a standard model for OA journal publishing: instead, a commercial model that charged authors rather than readers, pioneered by BioMed central publisher in 1999, became widespread [

10,

11]. That model came later to be known as ‘gold’ OA, and that term was most likely to be selected because author processing charges (APC) were relatively high, approaching a few thousand US dollars. However, in the past few years there have been a revival of that initial model of open access journal publishing, free both for readers and authors, under the name of ‘platinum’ or ‘diamond’ OA [

12,

13].

3. Legal Dimension: Gratis, Libre and Bronze OA

Peter Suber emphasized the need to differentiate between gratis and libre open access, or between a work being available free of charge vs. free of any usage restrictions [

14]. For example, an open access research article can be available on publisher’s website for reading without payment, but remain restricted from distribution through other databases, electronic libraries, social media and etc. The category of

gratis OA therefore includes all works available without price restrictions; the category of

libre OA is narrower: in addition to price it requires removal of at least some of permission barriers, e.g., by license that allows all uses of the work except commercial usage.

There is a difference between greed/gold and gratis/libre types of OA, according to the author, because in the first case the distinction goes about journals and venues, and in the second case about right and freedoms. Therefore, categories proposed by P. Suber are essentially

legal categories. Bronze OA introduced by Piwowar et. al. [

15] is another example of legal category, used to describe works that include articles free to read on publisher’s website, but without any clearly identifiable license.

Legal categories are essentially different from classic. While green and gold OA represent two pathways towards implementing OA vision that differ substantially both in organization and technical implementation, legal categories only measure whether access and usage of research work is permitted according to the law.

From that perspective, black OA [

16,

17] presents as a clear example of legal category. In such case research works are made available for reading free of charge, but without permission. The term itself was coined by [

18] to describe a novel type of open access to academic literature that was provided by Sci-Hub and Library Genesis websites without regard of copyright law; here the color black is meant to emphasize the illegal mode of operation of these projects. This type of open access will be explored in the next section.

4. Open Access After 2000: Many Shades of Black

Previously published literature on black open access [

4,

19,

20,

21] provided only a superficial overview of its landscape, without detailed distinctions between different projects, creating an impression of a monolithic domain. In fact, as will be discussed in following paragraphs, different types of black open access projects can be identified, namely:

classic shadow libraries e.g., Library Genesis;

online literature-sharing communities;

automatic tools for paywall circumvention e.g., Sci-Hub;

academic social networks.

There are substantial differences in approach and technical implementation between them. I will describe each sub-category in chronological order, starting from earliest one.

4.1. The Classic Shadow Library

Typical example projects in this category are AvaxHome [

22], Natahaus [

23], Gigapedia [

24] and Library Genesis [

25].

Shadow libraries have reached the popularity in the period from 2000 to 2010. Technically these were centralized file-sharing websites that accumulated content uploaded by users. AvaxHome (2008-2016) was a general-purpose website with a special section for books; Natahaus (2008-2012) website had a motto ‘knowledge without borders’ and was dedicated to books only. None of these websites provided access to academic journals, but large numbers of books were shared for free; the books were either scanned or downloaded from publishers’ website. The financial support was provided by ads, user donations or premium accounts. Because these projects operated without regard for copyright, they were routinely targeted by lawsuits from publishing companies. However, content shared on these websites often preserved online even after the project was shut down, because it had a backup on a decentralized BitTorrent network [

26].

The Gigapedia, also known as ebooksclub.org and libraru.nu (2004-2012) was destroyed after a lawsuit filed by 17 academic publishers. The library had about 1 million books available for free, and reportedly reached audience of half a million readers [

19].

Library Genesis started in 2008 as an initiative to make ‘KOLXO3’, a famous digital offline collection of 59,000 scientific ebooks, that was distributed on 64 manually-copied DVD drives, available online [

27]. An open-source indexing and search engine were developed. After that LibGen continued to grow by accepting uploads from users and absorbing collections of other shadow libraries, including Natahaus and Library.nu — but unlike these websites, LibGen did not emphasize community features and positioned itself as a kind of index or meta-library project instead. The project produced a number of mirrors and forks i.e., Z-Library and turned out to be the most resilient shadow library that still remains functional and updated with new literature, even though most of its mirrors got shut down.

Starting from 2012, Library Genesis became the first shadow library to start providing access to academic journals, in addition to books. However, it was second to Sci-Hub, a project that is not technically a shadow library, but an automatic tool for paywall circumvention, launched in 2011 [

28].

4.2. Literature-Sharing Communities

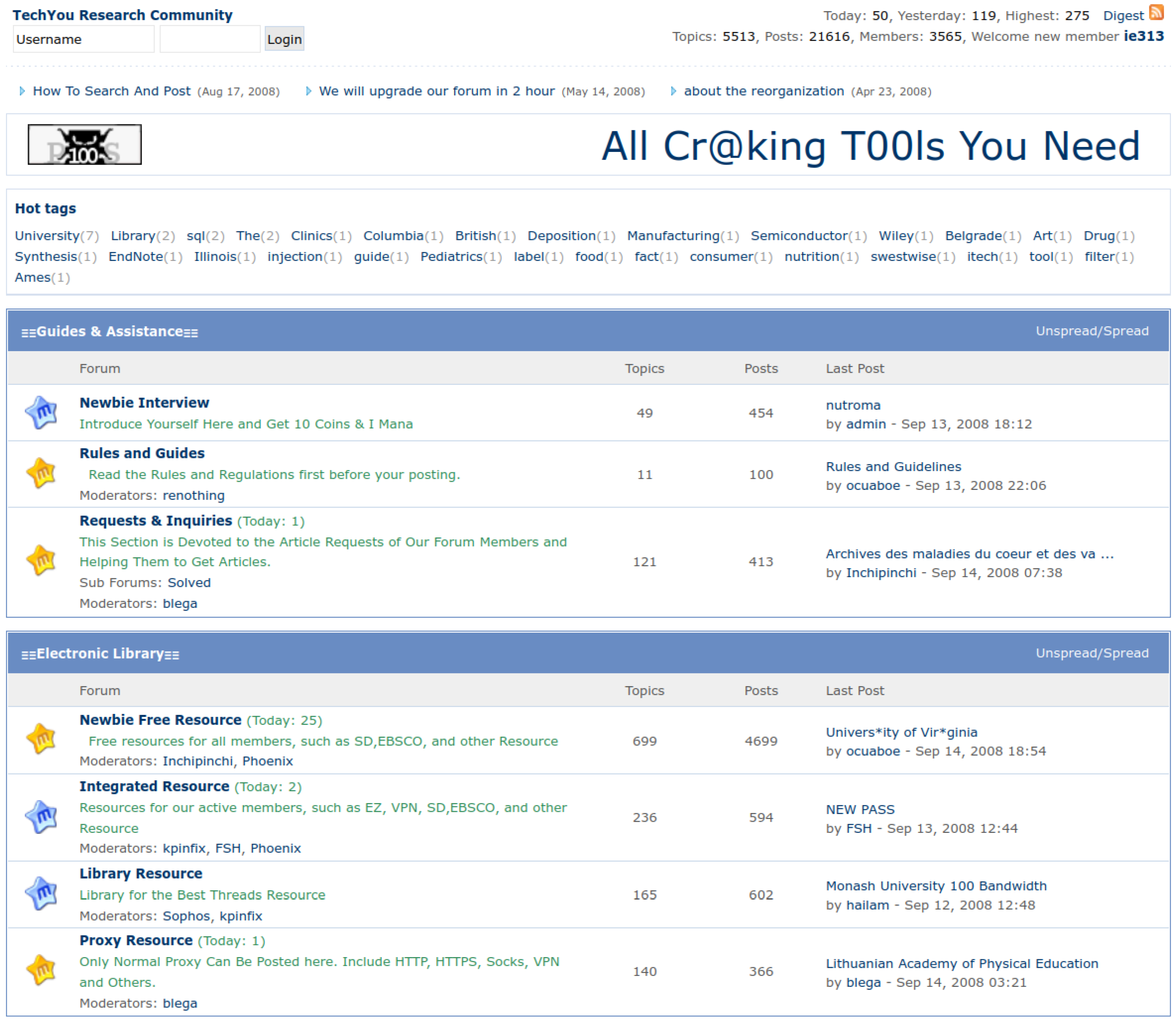

Before Sci-Hub was launched, some access to scientific journals was available through online research communities. These are almost never mentioned in publications, even though they were instrumental to the development of black open access, providing a necessary foundation for Sci-Hub.

In modern Internet, social media is a standard venue for online communication, however, before social networks became widespread, most discussions online happened through forums (bulletin boards). These were technically different and much less centralized than social networking websites: typically, an online community would have a forum for discussions set up on a separate server. That required some level of technical expertise, while modern social media provide an end-user functionality to create online communities after registration.

In late 2000s there existed numerous online forums dedicated to sharing and gaining access to academic literature, that brought together students and researchers, such as myescience [

29], TechYou [

30] shown on

Figure 1, expaper [

31] and others. These academic forums provided a market to share or sell student or faculty accounts, which could be used to enter VPN and proxy servers located at university libraries, to access subscribed content on websites such as ScienceDirect. Furthermore, there were sections of the forum where scientific literature could be uploaded and requested. These communities were organized in a hierarchical way, and newly registered members could access only a limited number of resources.

Another type of online communities that blossomed in late 2000 were professional forums for researchers, such as MolBiol [

32] or ChemPort [

33] that brought together students and researchers in molecular biology and chemistry fields. These forums had a dedicated ‘Full Text’ section, where forum member could request help in getting access to some paywalled paper [

34], and other forum members who had access e.g., through university subscription could help by sending or uploading PDF of the paper requested.

After social media became widespread, the popularity of forums have declined, however, communities for sharing and exchanging literature started to appear e.g., on Facebook. The #icanhazpdf Twitter tag [

35] became a re-implementation of the request papers functionality previously provided by forums. The actual impact and scope of these new developments remain to be estimated.

4.3. Automatic Paywall Circumvention Tools

By 2011, shadow libraries only provided access to academic books, but not journals. Online research communities enabled members to access research publications by request or through university library accounts; that was essentially manual access: inconvenient, cumbersome and time-consuming, and the number of people who could use it was limited by design.

To address these limitations, in 2009 I proposed creating a decentralized network for sharing access to scientific journals, that could be built upon an existing open source P2P-software such as eMule [

36]. The application would be installed on a student or researcher’s device, and listen for requests from other members connected to the network. If requested journal was accessible through university subscription, the application would automatically provide access to it. However, the idea of ‘Sci-Net’ was never implemented.

Two years later I came up with a different design for an application that could also provide automatic access to paywalled research publications, built upon an anonymization and censorship-circumvention technology. The application is installed on a centralized web server, accepting requests; the requested content is then downloaded through a proxy server, and provided to the user. That approach enables users to browse web pages anonymously (because the IP address is hidden by a web server and a proxy) and access content that was restricted e.g., by government, using a proxy from different country [

37].

Sci-Hub [

38,

39] was an extension of this censorship-circumvention methodology to the domain of scientific journals, where access is restricted by paywall. The website at first simply enabled users to browse paywalled websites such as ScienceDirect through a number of proxies provided by university libraries; accounts to access these proxies were collected on forums. Thus technically, Sci-Hub is very different from Napster, to which it was compared in media and research publications [

18], as well as from search engine [

40], even though it is often being perceived as such, probably due to a similar design.

The first version of Sci-Hub functioned as a browser for academic websites; downloaded PDF documents would be deleted from cache after a few hours. Starting from 2012, Library Genesis project began to accumulate research articles in their repository, in addition to books. They’ve started collaborating with Sci-Hub to save downloaded papers. Later, Sci-Hub began to redirect to Library Genesis for those articles already present in database, to avoid overloading university proxies. From 2014, Sci-Hub implemented its own storage for articles separate from LibGen, while keeping the latter updated with new downloads.

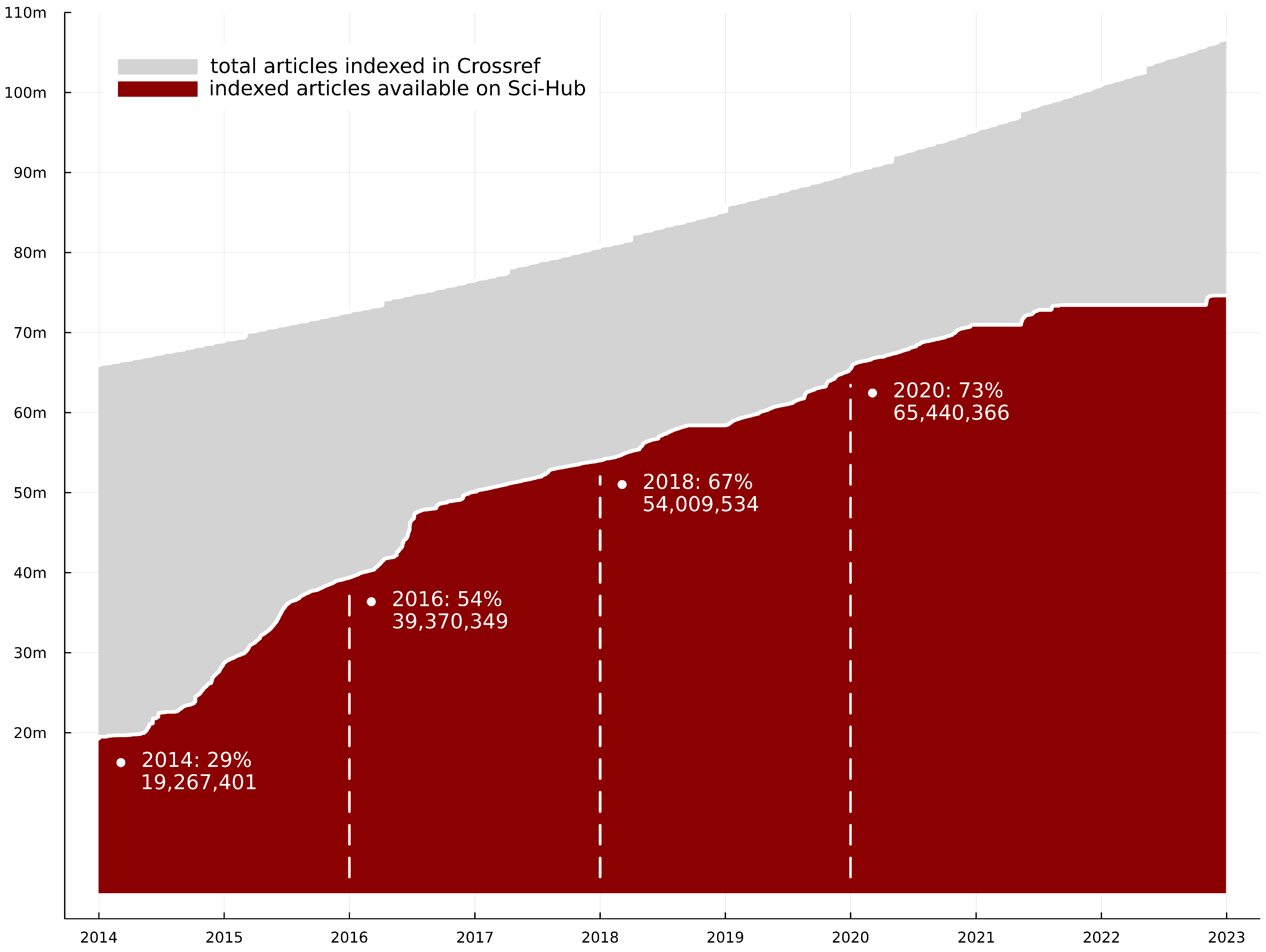

From 2015 onwards, Sci-Hub ceased its browsing functionality completely: instead, the website engine would download requested papers on its own and provide user with PDF. Furthermore, Crossref parser was implemented, so that for most requested academic publishers, Sci-Hub engine would monitor recently published research articles and download them in background. The database has grown to accumulate more than 88 million documents over 10 years.

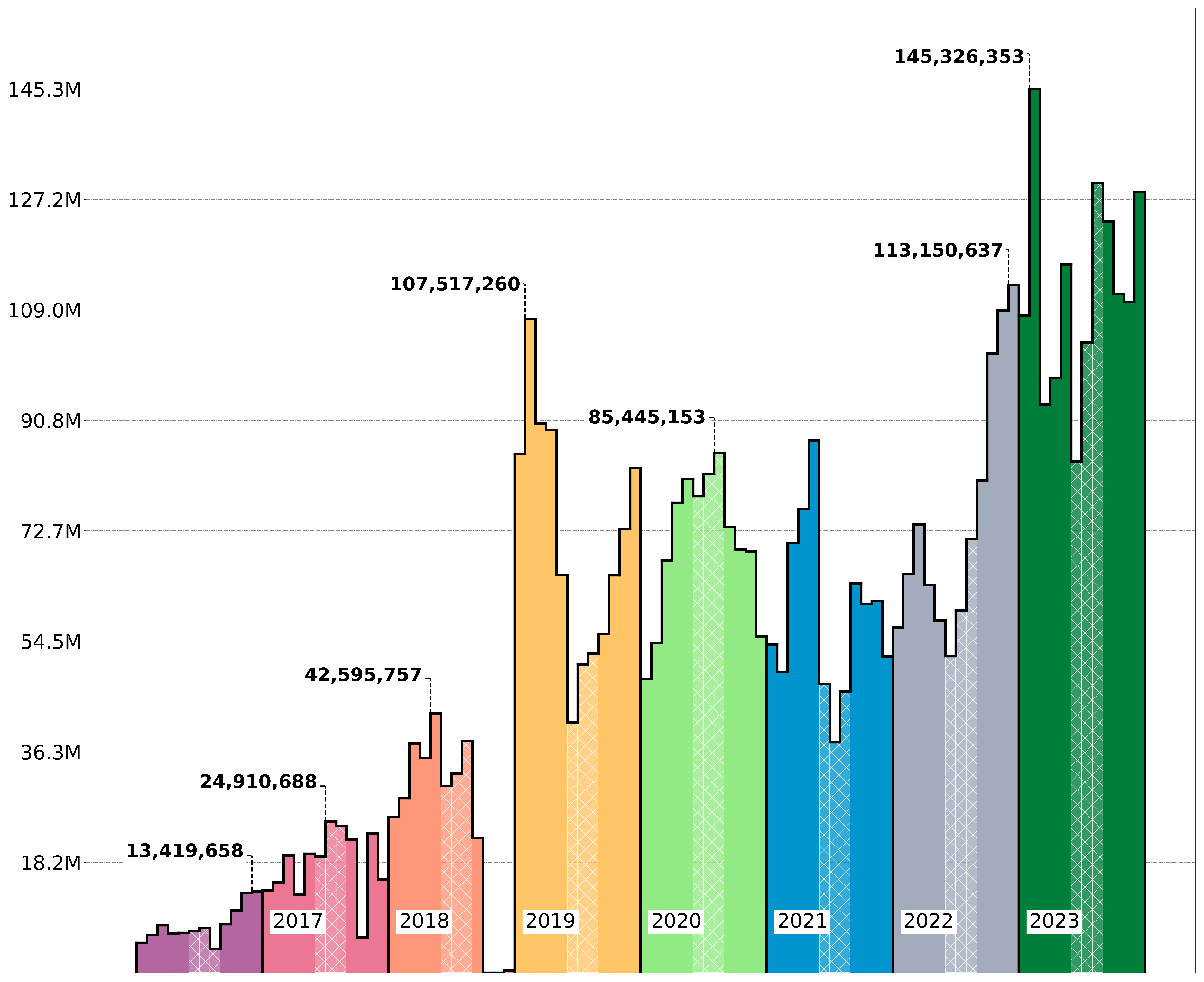

Figure 2 shows the accumulation of documents in Sci-Hub database over time, compared to the number of documents indexed in Crossref at the same moment; only journal articles and conference proceedings are counted, excluding other types of documents indexed in Crossref such as books, book chapters, dissertations and etc., since these documents are not included in Sci-Hub database.

The approach implemented by Sci-Hub was completely novel and enabled direct and immediate access to paywalled research publications without involving manual labor [

41]. To the moment it remains the only successful case of automatic paywall circumvention project, although I’m aware of at least two projects that attempted to implement similar ideas. In particular, it seems that MolBiol forum had a collection of scripts at some point, that would be installed on forum members’ computer and run in the background, checking ‘Full Text’ forum section for new requests. When new request was found and computer had access, i.e was inside the university network, the paper would be automatically downloaded and sent by email. However, all scripts were outdated already by 2011 and I never seen this system in action.

There was also a ‘super-mega-downloader’ website set up by a student from MIPT [

42]. The application would take a DOI and provide PDF downloaded through university proxy server. Here the access was limited to a single Russian university, while Sci-Hub accumulated accounts from more than 400 universities worldwide. That project had an original authorisation system: a visitor had to complete a random sentence, using an indigenous knowledge specific to Russian and post-Soviet culture. From this it can be assumed that the website was never intended for large audience.

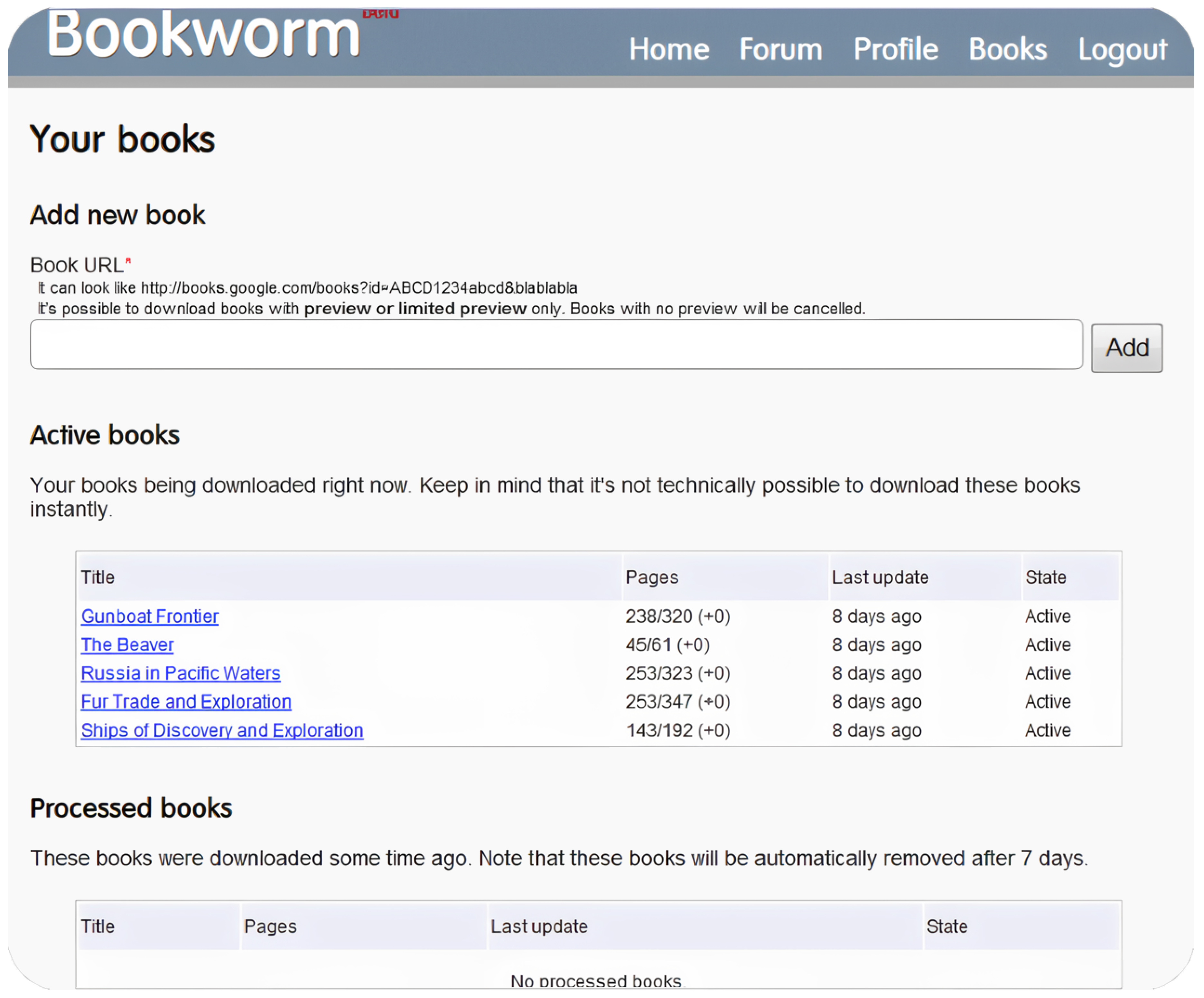

Bookworm service, launched in 2012, enabled users to automatically download entire books from Google Books as a PDF file (

Figure 3). Google provided partial access to their collection of scanned books, allowing users to preview a part of every book, or a few pages only, and in different countries of the world the pages available for preview would be different. Bookworm algorithm used multiple proxy servers located worldwide to collect entire book, and the download process could take more than a week. Unfortunately, the website did not last longer than a year.

4.4. Academic Social Networks

Academic social networking websites, namely Research Gate and Academia.edu, both established in the year 2008, are also mentioned in the literature under black open access label [

43,

44]. In addition to standard social networking functions, these websites provide functionality for registered authors to upload their work and make it available on the profile page. ASNs became about twice as popular among researchers than institutional repositories. However, most uploads were not preprints, but copyright-protected, camera-ready manuscripts formatted by publisher [

45]. Unlike typical shadow libraries though, ASNs do not disregard copyright law openly, and have been removing copyrighted content after lawsuits from academic publishers. A detailed review of ASNs would be out of scope for this paper; interested reader can consult [

43].

5. The Impact of Black Open Access

The number of research papers freely available online in repositories and publisher websites, i.e., through green and gold/diamond OA routes, have been steadily growing since 90s. However, the proportion of open access publications compared to the whole research output remained small: as the study by Laakso et al. has shown, the total share of OA journals in Scopus database in 2009 remained less than 7% [

46]; another study have estimated that only 11.9% of all scholarly articles published in 2008 were archived [

47].

Ten years after BOAI declaration, the access to literature still remained limited: most articles in academic journals were not accessible to general public neither through green/gold or diamond nor black OA venues (the latter provided access only to books). That situation only started to change after the launch of Sci-Hub project, which became the first website to provide direct free access to articles published in paywalled academic journals, to an unlimited number of users.

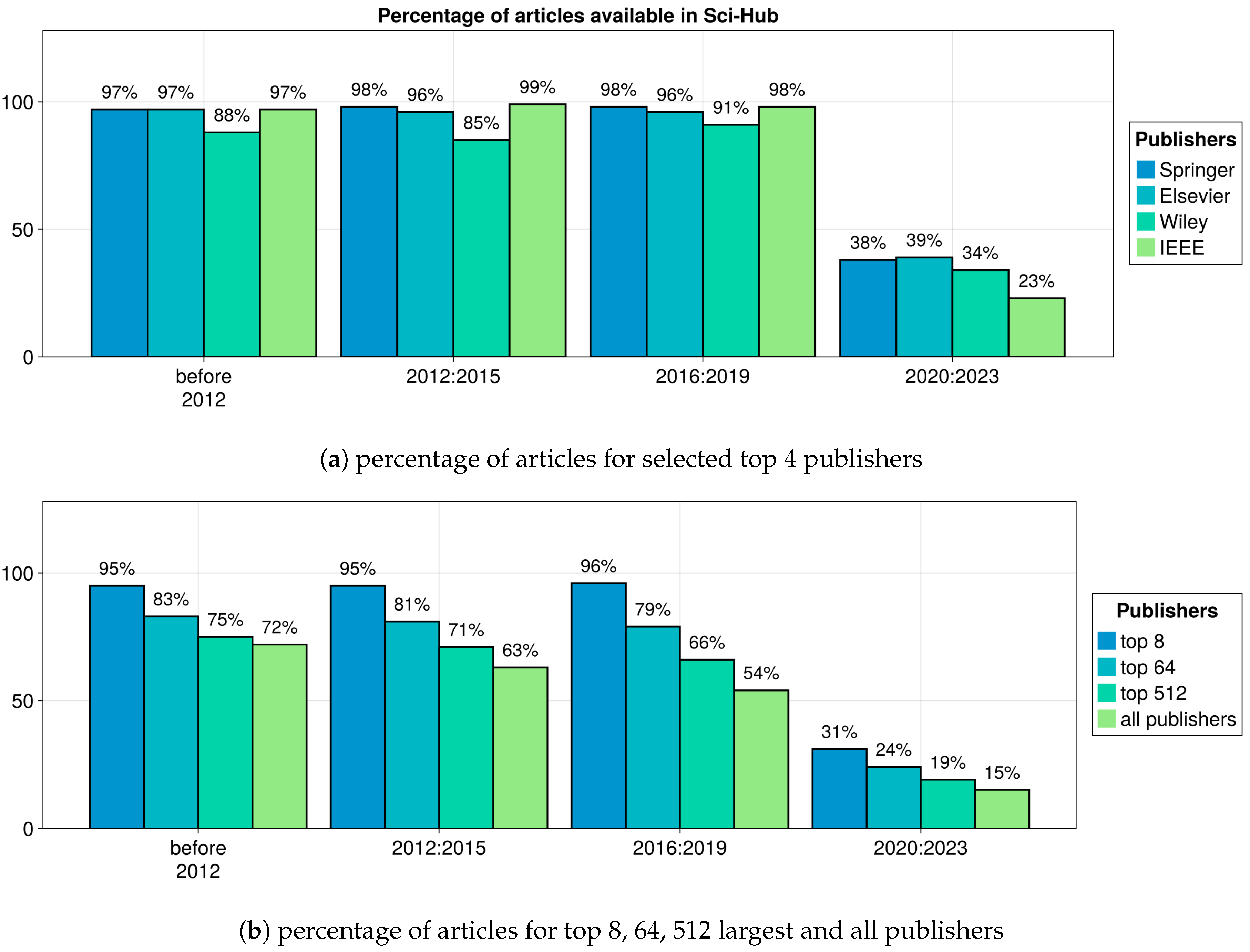

By 2018 Sci-Hub was estimated to provide access to more than 90% of paywalled scientific journals [

48,

49], but these estimations were indirect.

Figure 4 gives a more precise estimate, based on percentage of Crossref-indexed documents that are available in Sci-Hub database, according to the year of publication. For publishers with the largest number of articles, the percentage of documents currently available in Sci-Hub database is over 95% for publication years up to 2020; for recent years, the availability is lower since Sci-Hub was not updated regularly in the past few years.

The first users of Sci-Hub were members of Russian molecular biology and chemistry forums: before the website was launched, these forums already had well-developed and active ’Full Text’ sections for requesting access to paywalled papers; these sections brought together many potential users for Sci-Hub who did not have access through university subscriptions. From that starting point, Sci-Hub has quickly grown in popularity and was estimated to have around 200,000 daily users on average in 2016 [

50].

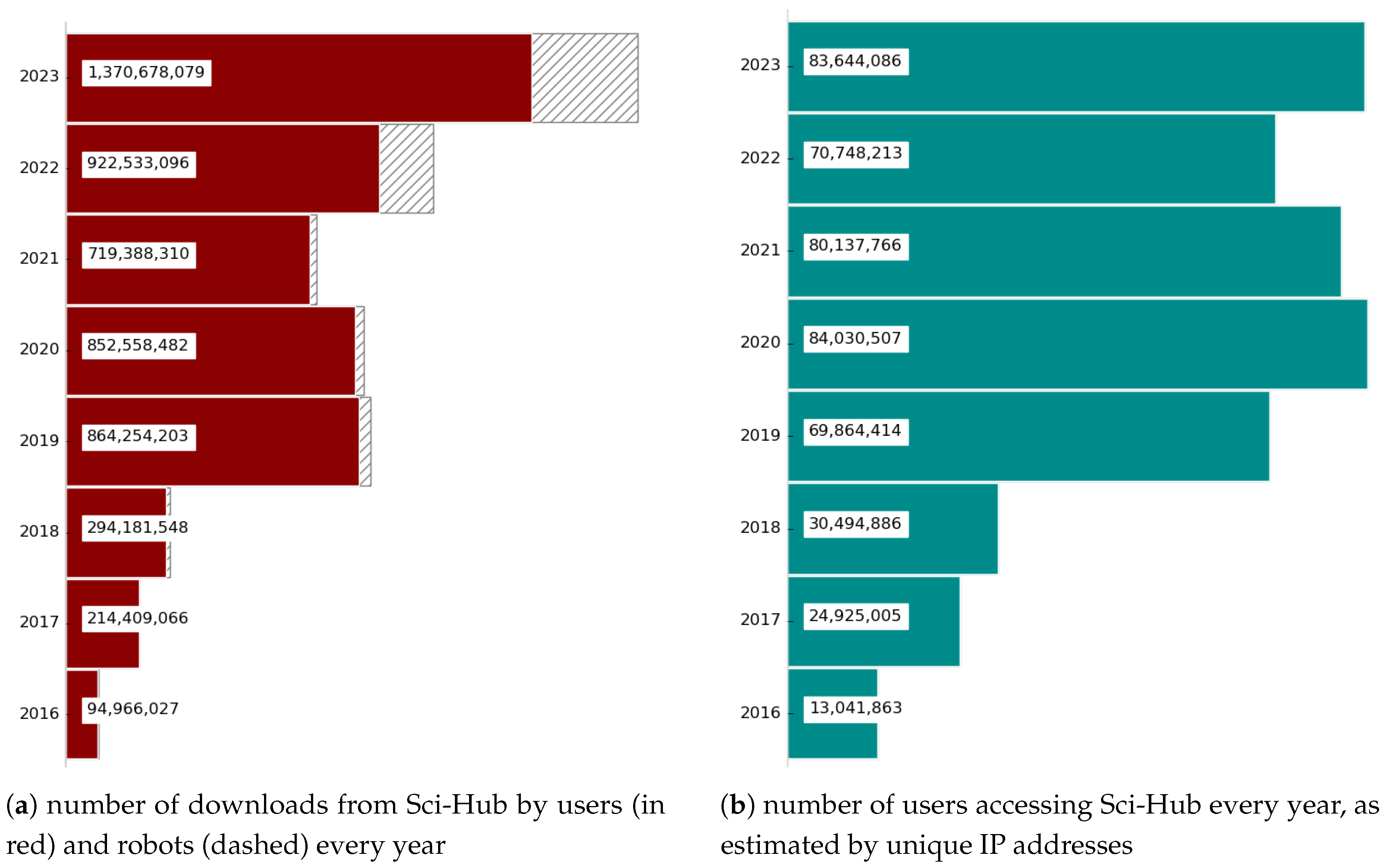

Up to 2016 there were no serious obstacles that could prevent the growing usage of Sci-Hub. Starting from 2016, the website attracted media attention as an illegal web service, and faced multiple lawsuits in different countries; Sci-Hub domains got seized and access to the website was blocked in some countries and universities [

51,

52]. One could assume that after that pressure the usage of Sci-Hub would diminish; contrary to this hypothesis though, the number of users since 2016 has been steadily growing, reaching one billion article downloads in 2023 (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

Some of these downloads can be attributed to robots, especially given the fact that number of AI agents accessing information on websites has increased dramatically in the past two years. For these figures, I’ve used a cutoff threshold of 100,000 downloads per month from a single IP address for robot identification. That method is not perfect, but it removes some obvious cases; a more sophisticated analysis of Sci-Hub download logs is the task of the future, but these preliminary results show that the impact of back open access on research and educational practice is huge. Furthermore, the statistics displayed here does not include downloads from Sci-Hub third-party mirrors, that are numerous and often used in place of the original website; the downloads from Library Genesis and its mirrors are also not counted. Taking this into consideration, the actual impact is probably much higher.

It has been argued that some part of Sci-Hub usage can be attributed to convenience, not need, since the number of Sci-Hub users was estimated to be larger around US universities, where access is already provided through library subscriptions: while Sci-Hub’s convenient interface enables user to access PDF of the required paper immediately, subscriptions access from off campus is much more cumbersome, as it requires user to pass through a sophisticated authentication system [

53]. However, increased usage in university cities could also be attributed to the alumni who lose access to university libraries after graduation, while moving on to work in research-intensive industries: in particular, it was found that most downloaded journals are in chemistry and engineering — areas where many graduates go into industry [

54].

Apart from download statistics, the impact of Sci-Hub can be indirectly estimated by a number of dissertations [

55,

56,

57,

58] and research papers [

59,

60] that mention it in the Acknowledgments section for providing necessary literature (using Google Scholar, I have manually calculated the number of master and doctoral theses that mention Sci-Hub to be over 200 in 2021).

Not only research was transformed: black open access also had impact on medical practice [

61,

62]. Two noticeable publications by authors from Cuba [

63] and Peru [

64] presented Sci-Hub usage as an ethical dilemma, where the choice has to be done between helping patients — or submitting to the current legal consensus that does not permit pirate access to literature:

In the case of Cuba, dentists’ access to the best scientific evidence is limited because textbooks are obsolete and there is no institutional access to articles of high scientific quality due to lack of funding to pay subscriptions.

Indeed, the impact of black open access is much more pronounced in poorer countries, even though Sci-Hub is being used worldwide. Ethics of Sci-Hub is an interesting and intricate matter; a number of authors have argued that the project unethical [

65,

66]. A detailed analysis of these arguments would be out of scope for this paper; the author of the present article holds to the opinion that Sci-Hub project aligns well with fundamental ethical values of science (Mertonian norms), while subscription journals are breaking this tradition [

67].

Taking all this into consideration it is not surprising that in numerous publications, black open access is perceived as a competitor or an adversary to classic approaches: green and gold/diamond; some authors have even argued that black OA can negatively impact other types of open access in the long term [

16,

40]. That perception is not completely unjustified, given that Sci-Hub has technically achieved the goal that open access movement initially aimed for (e.g., to make every published research paper available online free of charge). However, a more careful analysis would reveal that black open access in fact operates within a completely different domain than classic OA. The domain includes those research articles that have been published in subscription journals, and do not have preprint version deposited in repository. These articles are out of reach for classic approaches, that are concerned only with publishing new papers in open access, leaving the vast array of the already published knowledge to remain closed for good.

The primary impact of black OA was in opening this previously ignored domain of published knowledge; at the same time, it does not provide any solution for publishing new research articles in open access. Therefore, black and green, gold and diamond OA are indeed complimentary to each other, rather than competitive.

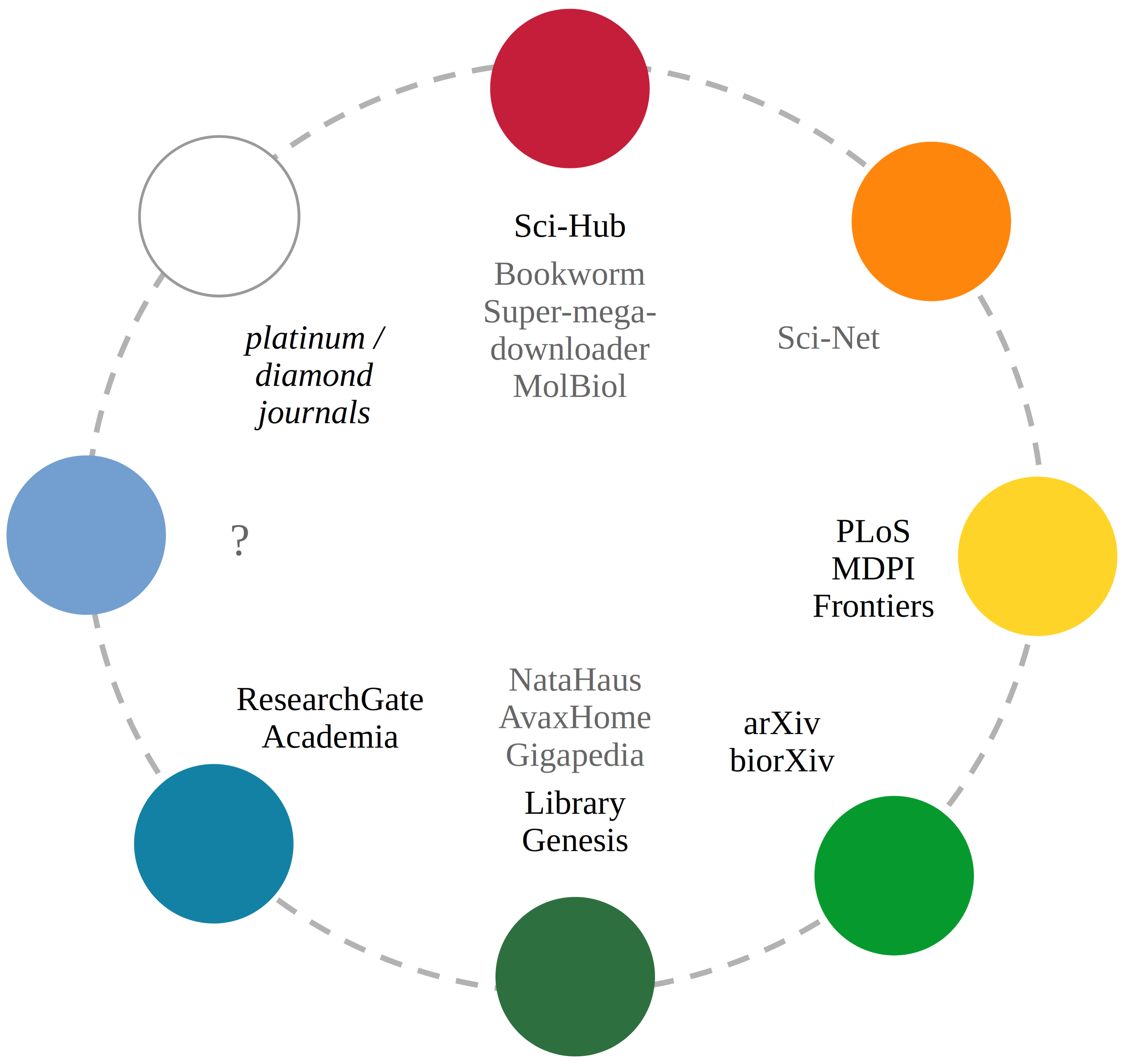

6. Bright Colors for Black OA

As was discussed in previous sections, the domain of black OA is not monolithic, but encompasses projects that are substantially different from each other both in organization and technical implementation. In particular, shadow libraries involve a community of contributors uploading new documents to the library, while automatic paywall circumvention tools such as Sci-Hub operate autonomously without human participation. To capture this diversity, more categories than just black are needed. I propose using the following color codes for different types of projects in that domain: red, green, blue and orange. These categories are meant to reflect the following substantial features of every open access project:

actors of change, who are supposed to be actively involved in the transformation;

technology and economical basis.

For example, gold and diamond pathways assume journal publishers to play a pivotal role in transition towards open access, while green approach assigns primary responsibility to researchers themselves, who are expected to self-archive their works; at the same time, gold and diamond OA differ substantially in economical basis: the former charges author publication fee, while the latter is supported from other sources, e.g., university funding.

From that perspective, shadow libraries should be considered a type of green OA: similarly to preprint archives, these libraries are essentially repositories that accumulate content uploaded by users — the only difference being that, while classic green approach to open access appeals to authors, shadow library websites are mostly maintained by readers, but in both cases community remains the main actor of change.

The quote from S. Hanrad, who is recognized as one of the founders of green OA, illustrates this spirit of a collective transformative action [

7]:

If every esoteric author in the world this very day established a globally accessible local ftp archive for every piece of esoteric writing from this day forward, the long-heralded transition … would follow suit almost immediately.

14 years after Hanrad’s ‘Subversive Proposal’ A. Swartz would publish his even more radical ‘Guerilla Open Access Manifesto’ urging everyone: scientists, librarians and ordinary men who have been ‘locked out’ of knowledge — to take part in breaking the barriers [

68]:

… trading passwords with colleagues, filling download requests for friends … We need to download scientific journals and upload them to file sharing networks. We need to fight for Guerilla Open Access. With enough of us, around the world, we’ll not just send a strong message opposing the privatization of knowledge — we’ll make it a thing of the past.

The community of participants here is not restricted to authors of research works only, but unbounded, including every person in the process. To differentiate ‘guerilla’ approach from classic green self-archiving, I propose using a ‘forest green’ color tone (#2e6f40).

Community action is an essential element of academic social networks, as well as their predecessors, online forums, and it is not unexpected that some authors recognize ASNs a variant of green OA [

69]. However, these websites are substantially different both from shadow libraries and preprint archives: they are not repositories of information, but communication tools. To account for similarities but at the same time emphasize the differences, I propose using a qīng blue color for this open access category. Blue is a color used by major social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook, while the word qīng in Mandarin Chinese is used to denote both green and blue color tone, and sometimes can be translated as black [

70].

Unlike preprint repositories, communication tools are not restricted to academic works published in traditional format, such as journal article or book: they can serve a more general purpose, and eventually transform scientific communication completely, in the same way as social media made classic newspapers obsolete [

71]. If some projects in future propose using new media e.g., blogs for communicating new discoveries instead of traditional journals, that will be a type of blue open access without green undertones.

Automatic paywall circumvention tools are technologically very different from other projects reviewed here, and form a different category, of which Sci-Hub is the only representative that has survived and developed enough to make noticeable impact. The project runs as an autonomous robot with minimal human participation and does not involve community, essentially making technology the central actor of change. That reminds of early discussions, when technologies were thought to play the most important role in transforming scholarly communications. The first sentence in BOAI declaration reads [

3]:

An old tradition and a new technology have converged to make possible an unprecedented public good

From this point of view, Sci-Hub can be thought of as a ‘pure implementation’ of Open Access ideal and a demonstration of a superior transformative power of technology. I propose using cardinal red color (#C41E3A) to identify automated pathway towards open access pioneered by Sci-Hub project. Red color is one of two main colors used on Sci-Hub website. Furthermore, in the past cardinal color represented the power of Pope [

72], reflecting a cult that was formed around Sci-Hub project.

However, automatic software for paywall circumvention can also be designed in a decentralized way, involving community of researchers. Even though this approach have not been implemented yet, it can be potentially done in future. For such decentralized approach, I propose using an orange color.

One category that has not been considered yet is hybrid OA. Many toll-access journals today operate in hybrid mode, allowing some articles to be published open access given that APC was provided. This is clearly a subset of gold open access, since publisher of a journal remains an actor of change.

That leaves us with following open access categories: red, green, blue, yellow (gold) and transparent (diamond), as well as orange, that have not been yet implemented (

Figure 7). These categories represent approaches towards open science that are substantially different in organization, technological implementation and economical basis.

In addition to substantial, the following legal categories can be identified: black or pirate, bronze, gratis and libre OA. These categories form a separate axis of rights and permissions, that ranges from prohibited (black) towards unidentified (bronze) to permitted, either for reading (gratis) or both for reading and re-use (libre).

Unlike categories of color, black open access does not reveal any substantial characteristics of many different projects it encompasses, but merely shows that these projects are prohibited under the current law. That is, if Sci-Hub started to accept unpublished works from authors, it would become a different project — but if copyright law allowed unrestricted distribution of research works, Sci-Hub would still remain Sci-Hub, even though the black open access would cease to exist. Legal categories are similar to skin color because they are external: it is easy to see how the same project can be either black or bronze depending on current conventions and laws.

In current literature on the topic of open access, legal and substantial categories are often mixed together. For example, in the study by Piwowar et. al. [

15] works are separated to green, gold, hybrid and bronze OA types. Even though such classification can be convenient for analysis, it is fundamentally wrong, as it results from application of different criteria inconsistently; that is, some approaches are described according to their essential features (green and gold OA), while others according to an external perspective of being legal or not (black and bronze OA) — and it is important to avoid such mistakes in future discussions.

7. The Impact of Color on Practice

I have argued above that theoretical discussion of OA in literature would benefit from having more categories to illuminate the rich diversity of ‘black open access’ landscape in order to understand it better. This renewed understanding should bring positive changes in practical attitudes towards projects in this domain.

Using the term ‘black’ to describe some phenomena, and especially to emphasize its illegal standing, creates a negative sentiment towards it, strong enough to block further attempts at rational discussion of the matter; it serves to neglect the phenomenon rather than understand it. Having more colors could be helpful in eliminating implicit bias that is currently present.

Furthermore, proposed color scheme enables to see the differences between projects within black open access domain, where Sci-Hub became a major and important technological breakthrough. For many years, Sci-Hub has been declined its novelty and presented as mere piracy — and piracy is not new; Sci-Hub was described in literature as the largest or the most popular shadow library, not as the first website ever to provide access to articles in paywalled academic journals. However, careful analysis of the history of black open access shows that, even though copyright infringement existed for many years, access to academic journals through pirate channels was complicated and limited; shadow libraries did not provide any coverage of scholarly journals for many years until Sci-Hub was invented.

That is especially important given that novelty is a principal value in research, and can have a significant effect on sentiment towards the project (for example, the recent study [

73] has demonstrated that malicious reviewer will primarily criticize the work for the lack of new contribution).

8. Declaration on the Open Access to Knowledge

The current framework for the open access movement is provided by three declarations that were signed in Berlin, Budapest and Bethesda in years 2001-2003. These documents were pivotal to the development of open access, and described general approaches towards OA (gold, green and diamond) that were practiced in research community by 2001. However, open access landscape have evolved dramatically since then and became much more diverse. There is an urgent need for a new or updated declaration on open access to knowledge.

The new declaration should recognize recent technological advances, instead of neglecting and marginalizing them. The ethical and legal challenges associated with these new platforms have to be openly discussed, and solutions developed. The discussion should be limited to Europe and United States, but include representatives from different countries of the world, including South America, Africa, India, China and former USSR.

9. Conclusions

This article presented a critical analysis of the existing open access models, with an especial emphasis on black open access, that up to this point remained poorly understood and largely neglected in the literature. The article provided an in-depth exploration of black open access domain and its historical development. As a result of the analysis, two independent dimensions of open access have been identified: one substantial and the other legal. The legal dimension currently includes black, bronze, gratis and libre OA; the substantial dimension is much more diverse, and the following types of open access can be identified: red, green, blue, yellow, orange and transparent OA. The most influential projects within black open access domain, Sci-Hub and Library Genesis, represent two substantially different approaches: red and green OA. Academic Social Networks, such as Research Gate or Academia, form a distinct category of blue open access.

Despite the rich tapestry of open access projects that have emerged in the past 20 years, the current discussion of open access in the literature is still operating within the framework set up by the BOAI declaration that was signed in 2001. There is an urgent need for a new and updated declaration, that would account for a rich diversity of approaches towards open science developed after 2001.

Conflicts of Interest

The author of the present article Alexandra Elbakyan is a creator of Sci-Hub website.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BOAI |

Budapest Open Access Initiative |

| ASN |

Academic Social Networks |

| APC |

Article Processing Charges |

| OA |

Open Access |

| RGB |

Red Green Blue |

| LibGen |

Library Genesis |

| DOI |

Digital Object Identifier |

| PDF |

Portable Document Format |

References

- Young, P. The Serials Crisis and Open Access: A White Paper for the Virginia Tech Commission on Research. Technical report, Virginia Tech, 2009. http://hdl.handle.net/10919/11317.

- Roberts, P. The crisis in scholarly publishing: Exploring electronic solutions. Access: Contemporary Issues in Education 1998, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Budapest Open Access Initiative. https://www.budapestopenaccessinitiative.org/, 2001.

- Bodó, B. Pirates in the library–an inquiry into the guerilla open access movement. 8th Annual Workshop of the International Society for the History and Theory of Intellectual Property, CREATe, University of Glasgow, UK, 2016.

- arXiv.org website. https://arxiv.org/, 2024.

- Taubes, G. Publication by Electronic Mail Takes Physics by Storm. Science 1993, 259, 1246–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harnad, S., A Subversive Proposal. In Scholarly Journals at the Crossroads: A Subversive Proposal for Electronic Publishing; Okerson, A.; O’Donnell, J., Eds.; Association of Research Libraries, 1995.

- Crawford, W. Free electronic refereed journals: Getting past the arc of enthusiasm. Learned Publishing 2002, 15, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosmire, M.; Young, E.A. Free Scholarly Electronic Journals: An Annotated Webliography. Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, K.M. Open access: Implications for scholarly publishing and medical libraries. Journal of the Medical Library Association 2006, 94, 253–262. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, D. BioMed Central boosted by editorial board. Nature 2000, 405, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normand, S. Is Diamond Open Access the Future of Open Access? The iJournal: Student Journal of the Faculty of Information 2018, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Simard, M.A.; Butler, L.A.; Alperin, J.P.; Haustein, S. We need to rethink the way we identify diamond open access journals in quantitative science studies. Quantitative Science Studies 2024, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suber, P. Gratis and libre open access. SPARC Open Access Newsletter 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Piwowar, H.; Priem, J.; Larivière, V.; Alperin, J.P.; Matthias, L.; Norlander, B.; Farley, A.; West, J.; Haustein, S. The state of OA: A large-scale analysis of the prevalence and impact of Open Access articles. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T. We’ve failed: Pirate black open access is trumping green and gold and we must change our approach. Learned Publishing 30, 325–329. [CrossRef]

- Elroukh, S.M. Shadow Libraries: A Bibliometric Analysis of Black Open Access Phenomenon (2011: 2023). International Journal of Computer Science and Network Security 2024, 24, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk, B.C. Gold, green, and black open access. Learned Publishing 2017, 30, 173–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L. Shadow Libraries. e-flux Journal 2012. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/37/61228/shadow-libraries/. [Google Scholar]

- Karaganis, J., Ed. Shadow Libraries: Access to Knowledge in Global Higher Education; The MIT Press.

- Kjellström, Z. Black Open Access in Sweden: A study on the perceptions on and usage of illicit repositories of academic documents. Master’s thesis, Lund University, 2019. https://lup.lub.lu.se/student-papers/search/publication/8978272.

- AvaxHome: eBooks & eLearning. https://web.archive.org/web/20140810181338/http://avaxhm.com/ebooks, 2014.

- NataHaus website index page as of 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120215041729/http://www.infanata.com/category/science/, 2012.

- Ebooksclub website as of 2006. https://web.archive.org/web/20060708235832/https://ebooksclub.org/, 2006.

- Cabanac, G. Bibliogifts in LibGen? A study of a text-sharing platform driven by biblioleaks and crowdsourcing. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 2016, 67, 874–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infanata.com library archives at Book Tracker. https://booktracker.org/viewforum.php?f=1001.

- KOLXO3 library archives at the Internet Archive. https://archive.org/search?query=subject:KOLXO3.

- Banks, M. What Sci-Hub Is and Why It Matters. 2016, 47, 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Myescience forum: Index page available from Internet Archive. https://web.archive.org/web/20111207072956/http://www.myescience.org/, 2011.

- TechYou forum’s archived index page. https://web.archive.org/web/20080914111322/http://bbs.techyou.org/, 2008.

- expaper.cn online literature-exchange forum. http://www.expaper.cn. Accessed: 2024-11-15.

- molbiol.ru online forum for researchers. http://molbiol.ru/forums. Accessed: 2024-11-15.

- chemport.ru online forum for researchers. http://www.chemport.ru/forum/.

- “Full Text” section at molbiol.ru online forum. http://molbiol.ru/forums/index.php?showforum=2. Accessed: 2024-11-15.

- Gardner, C.C.; Gardner, G.J. Bypassing Interlibrary Loan Via Twitter: An Exploration of #icanhazpdf Requests. ACRL 17th National Conference, "Creating Sustainable Community", 2015, pp. 95–101.

- eMule project website. https://booktracker.org/viewforum.php?f=1001.

- Elibol, E. The Internet vs. the Nation-State: Prevention and Prosecution Challenges on the Internet in Republic of TürkiyI. PhD thesis, 2014. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/gpis_etds/48.

- Sci-Hub: Index page. https://sci-hub.se/, 2024.

- Sci-Hub: Early version of the website. https://web.archive.org/web/20130206053457/http://www.sci-hub.org/, 2013.

- Novo, L.A.; Onishi, V.C. Could Sci-Hub become a quicksand for authors? 2017, 33, 324–325. [Google Scholar]

- Elbakyan, A. New web service for downloading research articles. https://web.archive.org/web/20111021213227/http://molbiol.ru/forums/index.php?showtopic=483925, 2011.

- Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology. “super-mega-downloader”: Authorization page from Internet Archive. https://web.archive.org/web/20130706174612/http://science4you.lib.mipt.ru/, 2013.

- Jordan, K. From Social Networks to Publishing Platforms: A Review of the History and Scholarship of Academic Social Network Sites. Frontiers in Digital Humanities 2019, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmack, P.; Kearney, M.; McCann, A. Communication Scholarship and the Quest for Open Access. Journal of the Association for Communication Administration 2023, 40, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jamali, H.R. Copyright compliance and infringement in ResearchGate full-text journal articles. Scientometrics 2017, 112, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laakso, M.; Welling, P.; Bukvova, H.; Nyman, L.; Björk, B.C.; Hedlund, T. The Development of Open Access Journal Publishing from 1993 to 2009. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e20961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björk, B.C.; Welling, P.; Laakso, M.; Majlender, P.; Hedlund, T.; Guðnason, G. Open Access to the Scientific Journal Literature: Situation 2009. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e11273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmelstein, D.S.; Romero, A.R.; Levernier, J.G.; Munro, T.A.; McLaughlin, S.R.; Greshake Tzovaras, B.; Greene, C.S. Sci-Hub provides access to nearly all scholarly literature. eLife 2018, 7, e32822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.K.; Piryani, R.; Srichandan, S.S. The case of significant variations in gold–green and black open access: Evidence from Indian research output. Scientometrics 2020, 124, 515–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, J. Who’s downloading pirated papers? Everyone. 2016, 352, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Ordoñez, D.; Simón, V.I. Criminalizing Information Providers: The cases of Sharina, Gómez, Elbakyan and Swartz. 2017, 46, 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, L. Is Sci-Hub Safe? Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/01/17/universities-ignore-growing-concern-over-sci-hub-cyber-risk, 2020.

- LaDue, J. Exploring the convenience versus necessity debate regarding Sci-Hub use in the United States. PhD thesis, 2018.

- Greshake, B. Looking into Pandora’s Box: The content of Sci-Hub and its usage. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hierro Fabregat, A. Monotonicity preserving shock capturing techniques for finite elements. PhD thesis. https://hdl.handle.net/10803/398577.

- de Sousa, P.R. Resilient arthropods: Buthus scorpions as a model to undestand the role of past and future climatic changes on Iberian Biodiversity. PhD thesis, 2017.

- Duteil, M. Collective Behaviour: From Cells to Humans. PhD thesis, 2018.

- Matthis, C. Neurobehavioural patterns of alcohol abuse in adolescence. PhD thesis, 2019.

- Dagg, J.L. Motives and merits of counterfactual histories of science. 2019, 73, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, J.; Szmuda, T.; Kozłowski, D. Does the choice of drug in pharmacologic cardioversion correlate with the guidelines? Systematic review. 2021, 30, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudry, C.; Alvarez-Muñoz, P.; Arencibia-Jorge, R.; Ayena, D.; Brouwer, N.J.; Chaudhuri, Z.; Chawner, B.; Epee, E.; Erraïs, K.; Fotouhi, A.; Gharaibeh, A.M.; Hassanein, D.H.; Herwig-Carl, M.C.; Howard, K.; Kaimbo Wa Kaimbo, D.; Laughrea, P.A.; Lopez, F.A.; Machin-Mastromatteo, J.D.; Malerbi, F.K.; Ndiaye, P.A.; Noor, N.A.; Pacheco-Mendoza, J.; Papastefanou, V.P.; Shah, M.; Shields, C.L.; Wang, Y.X.; Yartsev, V.; Mouriaux, F. Worldwide inequality in access to full text scientific articles: The example of ophthalmology. 2019, 7, e7850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Till, B.M.; Rudolfson, N.; Saluja, S.; Gnanaraj, J.; Samad, L.; Ljungman, D.; Shrime, M. Who is pirating medical literature? A bibliometric review of 28 million Sci-Hub downloads. 2019, 7, e30–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales-Reyes, I. Sci-Hub and evidence-based dentistry: An ethical dilemma in Cuba. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendezú-Quispe, G.; Nieto-Gutiérrez, W.; Pacheco-Mendoza, J.; Taype-Rondan, A. Sci-Hub and medical practice: An ethical dilemma in Peru. 2016, 4, e608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweet, C. An Introduction to Sci-Hub and Its Ethical Dilemmas. 2018, 45, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Asim, Z.; Sorooshian, S. Unethical research trend: Shadow libraries. 2018, 136, 96–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R.K. A Note on Science and Democracy. 1942, 1, 115. [Google Scholar]

- Swartz, A. Guerilla Open Access Manifesto. http://archive.org/details/GuerillaOpenAccessManifesto, 2008.

- Gray, R. Sorry, we’re open: Golden Open Access and inequality in the natural science. [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Wong, J. The Confounding Mandarin Colour Term ‘Qīng’: Green, Blue, Black or All of the Above and More? In Studies in Ethnopragmatics, Cultural Semantics, and Intercultural Communication: Minimal English (and Beyond); Sadow, L.; Peeters, B.; Mullan, K., Eds.; Springer; pp. 95–116. [CrossRef]

- Lievrouw, L.A. Social Media and the Production of Knowledge: A Return to Little Science? 2010, 24, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, C.M. The Cardinal’s Wardrobe. In A Companion to the Early Modern Cardinal; Mary Hollingsworth, M.P.; Witte, A., Eds.; Brill, 2019; pp. 535–556. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhu, K.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, J. AgentReview: Exploring Peer Review Dynamics with LLM Agents, 2024, [2406.12708]. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).