1. Introduction

Urban flooding is a prevalent phenomenon that poses significant challenges to cities around the world. With increased urbanization, the natural landscapes that once absorbed rainfall are often replaced by impermeable surfaces. This transformation disrupts the natural flow of water, leading to inadequate drainage systems that struggle to cope with heavy rainfall and storm surges [

1,

2]. Due to increased urbanization and the effects of climate change future alterations in rainfall patterns, frequency, and intensity are anticipated, which will likely lead to a higher incidence of urban flooding [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

In Bangladesh, the Dhaka Metropolitan area has experienced the severity of urban flooding over the past several years [

9,

10,

11]. Though the city is protected from river flooding by an embankment, it gets affected by pluvial flooding almost every year. During the monsoon season the water level in the river exceeds the water level inside the city area. As a result, the city drainage depends very much on the water levels of the peripheral river systems. The situation worsens when runoff from short duration and high intensity rain combines with high river water level.

Over the past few decades, Dhaka has seen a substantial increase in population, urbanization, and infrastructure development [

12]. While these factors have contributed to economic growth and urban expansion, they have also heightened the city’s vulnerability to flooding events [

13,

14]. Inadequate drainage systems along with improper operation and maintenance has also exacerbated these floods [

15]. Dhaka has faced significant flooding in various years, including 1954, 1955, 1962, 1963, 1971, 1974, 1980, 1987, and 1988, 1998, and more recently in 2004, 2007, 2017, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2024. The recent flood on 12 July, 2024 was caused by just 3-4 hours of torrential rain. These flooding events have led to significant property loss, including damage to utility infrastructure and household assets, along with significant human and economic consequences, highlighting the urgency of effective flood management.

In this context, the application of urban flood forecasting holds significant promise for Dhaka city. By harnessing cutting-edge technologies, urban flood forecasting offers a proactive approach to managing and mitigating flood-related risks [

16,

17]. Accurate and timely flood forecasts can equip city authorities, emergency responders, and the general populace with essential information to prepare for impending floods. This preparedness may help to minimize damage, safeguard lives, indicate waterlogged areas for traffic, and thus bolster overall resilience of the city [

6,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

This study aims to investigate the practical application of urban flood forecasting in Dhaka, focusing on the city's unique geographical features, hydrological dynamics, and technological capabilities. This exploration aims to illuminate the challenges faced by rapidly growing cities in developing countries and support the development of effective flood management and resilience-building strategies. Ultimately, the study goal is to support evidence-based policy decisions by providing maps and informative bulletins. These resources aim to enhance resilience and promote long-term sustainability in Dhaka and provide a framework for similar cities. Distinctively, the current review is solely dedicated to urban flooding to mitigate its challenges due to both rainfall induced and riverine flood. This study demonstrates a cohesive presentation of the flood scenario of Dhaka city where understanding of urban modelling will be achieved, and its output is presented.

2. Study Area

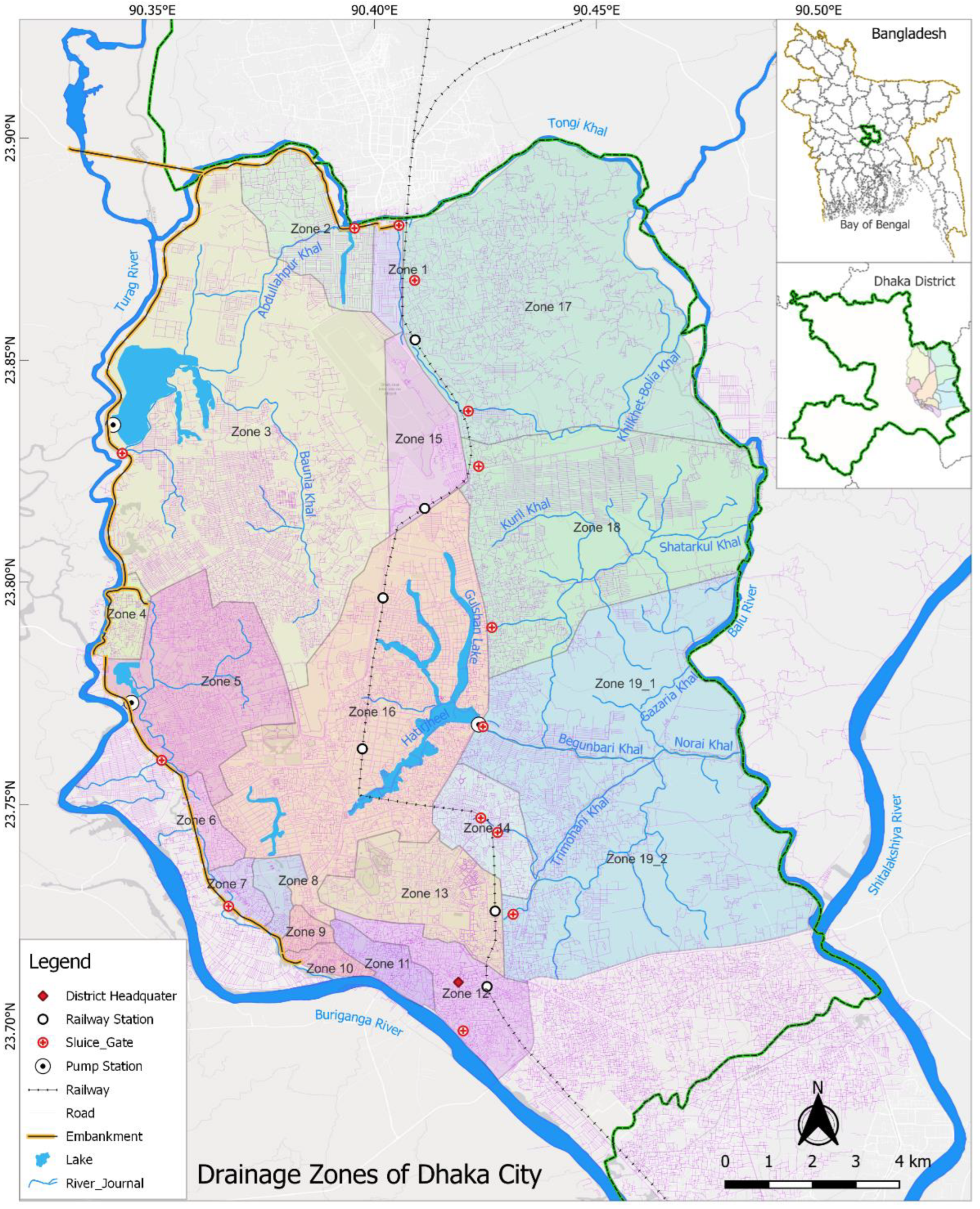

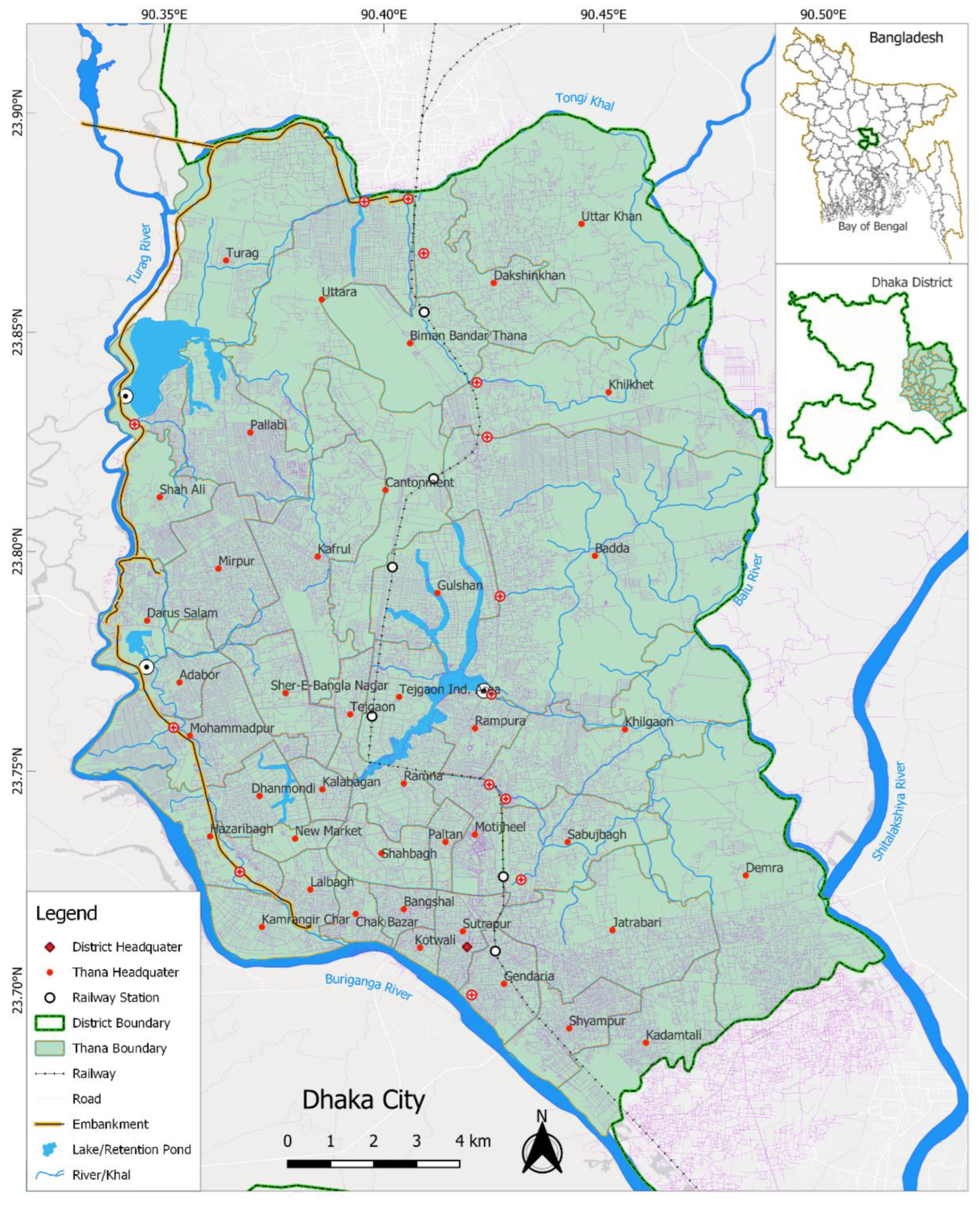

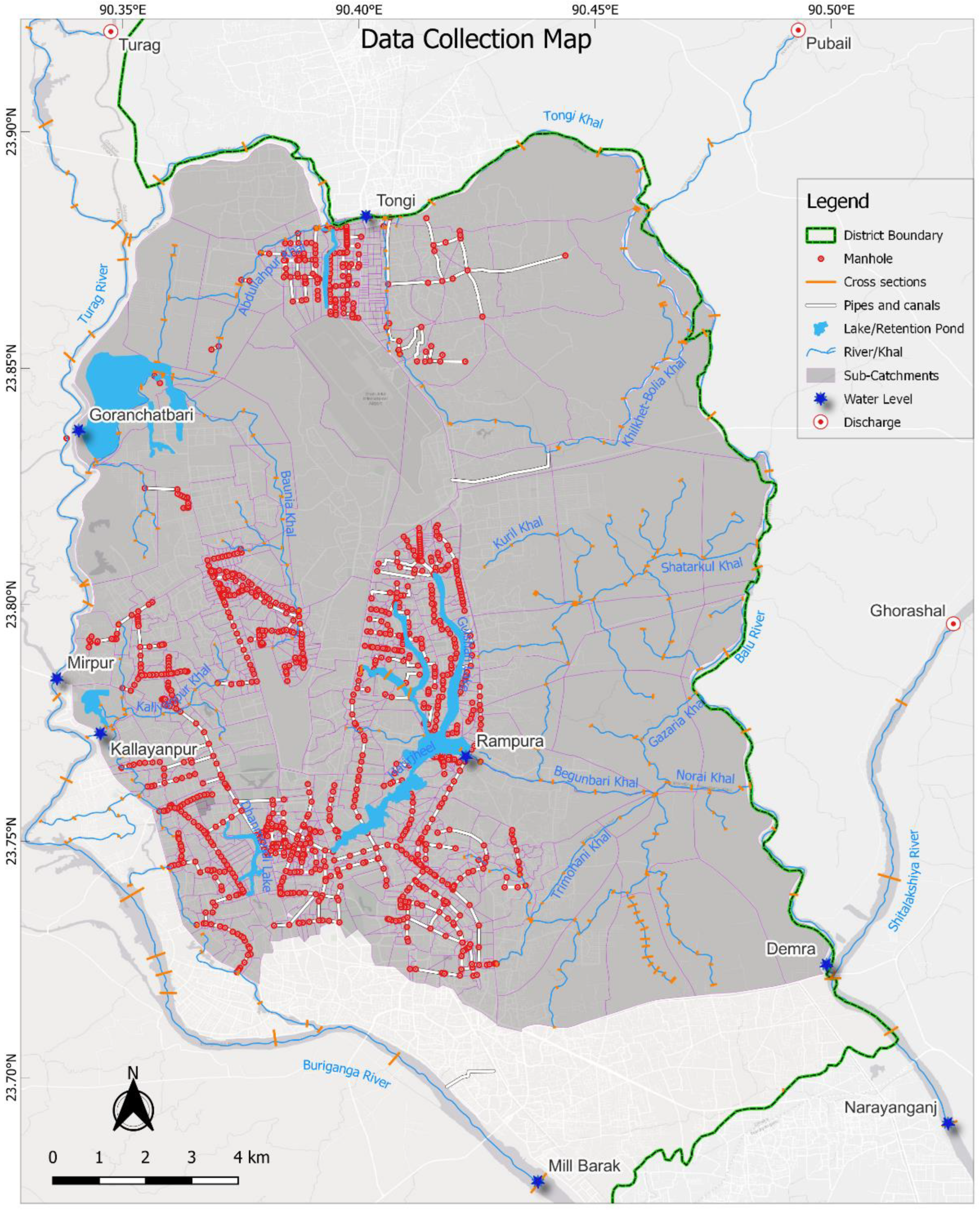

Geographically, the core area of Dhaka metropolitan city lies between 23.69° and 23.89° North latitudes and 90.33° and 90.44° East longitudes [

23], covering approximately 261.67 km² of land [

24] in

Figure 1. The study area presents a challenging landscape featuring complex hydrological conditions, an intricate drainage network, and recurrent urban flooding problems [

6,

11,

14,

25]. The city's location within a deltaic environment makes it particularly vulnerable to both riverine and rainfall-induced flooding [

26]. The hydrological dynamics and flooding challenges in Dhaka are influenced by the following key factors[

13,

27,

28].

River Systems: The city is traversed by numerous rivers, canals, and water bodies, which play a crucial role in its hydrological regime [

29,

30]. The city is surrounded by six interconnected river systems- Buriganga, Dhaleswari in the south, Turag and Tongi Khal in the North, Balu and Shitalakshiya in the east. These waterways exhibit substantial variations in water levels, especially during the monsoon season [

30,

31].

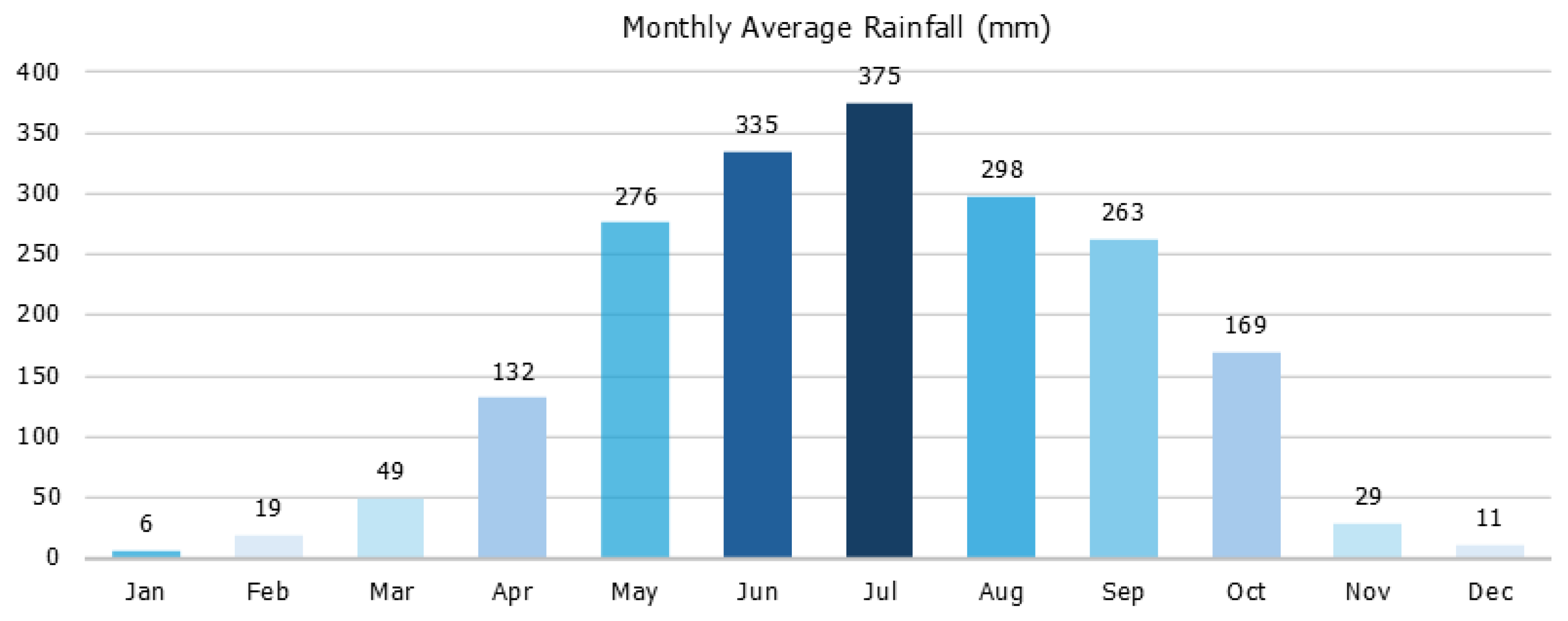

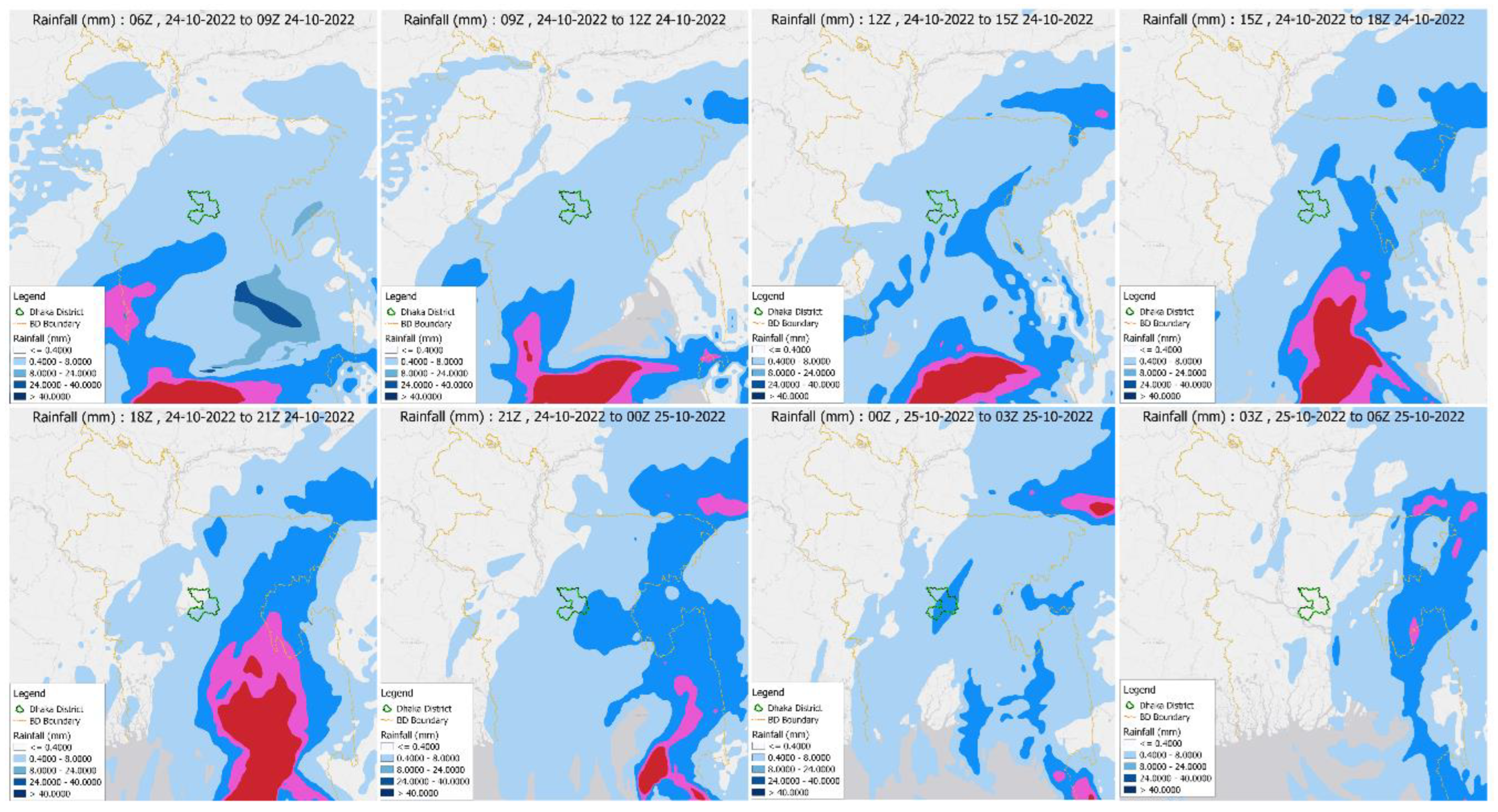

Monsoon Rainfall: Dhaka experiences a monsoon climate with heavy and concentrated rainfall during the wet season. This seasonal high concentrated rainfall (

Figure 2) significantly contributes to the city's flooding, as inadequate drainage systems struggle to cope with the rapid influx of rainwater [

32,

33].

Drainage Network: The drainage network in Dhaka city is a complex cobweb of canals, stormwater drains, and sewers designed to manage surface water runoff. This drainage system is divided into 20 zones (

Figure 7). However, several challenges hinder its effectiveness: (1) Inadequate Infrastructure: The rapid urbanization of Dhaka has outpaced the development of its drainage infrastructure. Many areas lack proper stormwater management systems, leading to waterlogging and urban flooding. (2) Encroachment and Land Use: Encroachment upon natural drainage paths and changes in land use, including the widespread concretization of surfaces, have disrupted the city's natural drainage patterns. (3) Siltation: Siltation in canals and water bodies reduces their capacity to carry water, contributing to localized flooding during heavy rainfall.

3. Necessity of Urban Flood Forecasting for Dhaka City

Every time major floods occur in the country; Dhaka City also faces acute drainage problems. In spite of huge investment over the years, particularly after the 1988 flood when almost the whole city of Dhaka went under water, the 1998 floods appeared most devastating. About Dhaka city, the drainage situation aggravates due to silted-up, blocked drainage channels. The recurring flooding problem in Dhaka city manifests in various ways: (1) Waterlogging: Prolonged waterlogging, especially in low-lying areas, disrupts daily life, affects transportation, and poses health risks to residents. (2) Infrastructure Damage: Flooding causes damage to roads, bridges, buildings, and utility infrastructure, leading to significant economic losses. (3) Human Displacement: Residents of flood-prone areas are often relocated during floods, with adverse social and economic consequences. (4) Health Risks: Stagnant floodwater can lead to the spread of waterborne diseases, posing health hazards to the population. The causes, impacts of urban flooding and necessity of this research is discussed in this section.

3.1. Causes of Flood

The Causes of floods and drainage problems can differ across various zones based on topography, proximity to rivers and land development.

River Flood: Dhaka is surrounded by rivers like the Shitalakshiya, Buriganga, Turag, Tongi and Balu which can cause floods in the city. Since the western part of the city is protected by flood embankment, greater risk of river flooding remains in the eastern part of the city[

32,

33].

Rainfall: Due to inadequate drainage system and clogged catch basins, manhole overflow, water logging occurs all around the city. If channels were rehabilitated, heavy runoff will easily flow outside the city. The eastern part is heavily affected by both pluvial and fluvial floods. There are few pumping stations in Dhaka but sometimes some of the pumps remain out of order, aggravating floods.

Climate Change and Rapid Urbanization: Dhaka City is becoming increasingly susceptible to urban flooding due to the evolving impacts of climate change, which are establishing through alterations in rainfall intensity, frequency, increased frequency of extreme weather events and distribution patterns [

32,

33,

34]. Such changes are leading to more erratic and concentrated rainfall events, causing flash floods and widespread waterlogging, as the existing drainage systems struggle to accommodate sudden surges in runoff [

32,

35]. Climate models indicate that the probability of extreme precipitation during the monsoon season is rising, resulting in severe flood risks for densely populated urban areas [

36]. Additionally, there has been an observable increase in the frequency and severity of extreme weather events, such as prolonged monsoon periods and cyclonic storms, which compound flood risks by exceeding both natural and artificial drainage networks [

10,

11]. Urban floods can occur when a pluvial flooding impacts a built environment where the natural landscape has been altered by the urban developments [

1]. When high-intensity precipitation events occur in an urban environment, flood levels may rapidly arise as the sewer system struggles to remove the rapid increase of runoff from continuous downpour. Due to increased and unplanned urbanization and climate change, the threat of urban flooding is evermore significant. The rapid urbanization of Dhaka has also contributed to the development of the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect, which exacerbates localized convective rainfall, leading to severe urban flooding in specific areas[

27]. While Dhaka is not directly exposed to sea-level rise, the surrounding rivers are influenced by the backwater effects from the Bay of Bengal, elevating water levels during the monsoon and further reducing drainage capacity, particularly in low-lying areas [

36]. Moreover, unplanned urban growth and encroachment on natural water bodies have further reduced the city’s ability to manage stormwater, intensifying the impact of climate-induced extreme weather events [

11,

28].

Topography: Dhaka's low-lying topography makes it particularly vulnerable to inundation, especially when combined with heavy rainfall and high tides from nearby rivers.

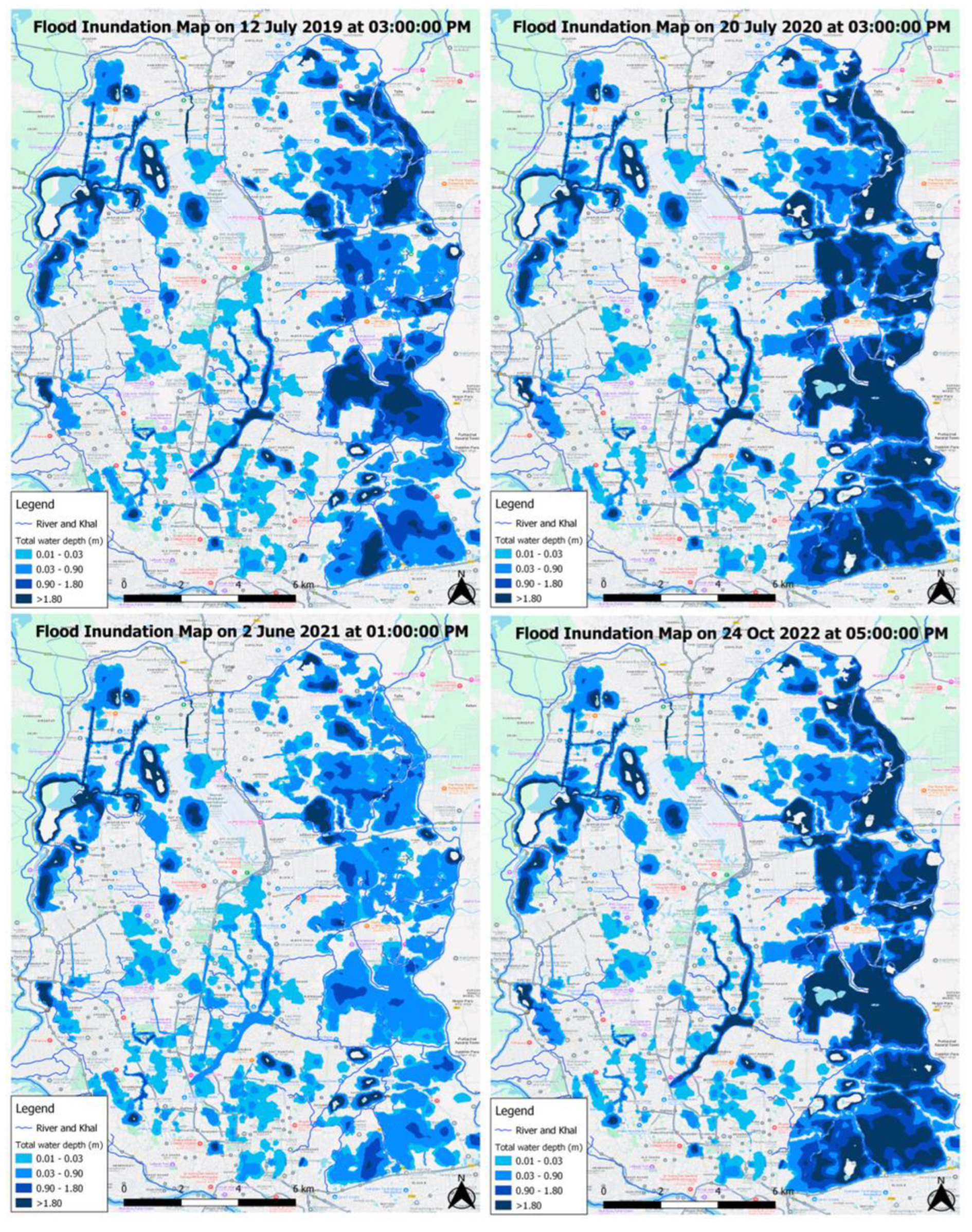

3.2. Impact of Recent Floods in Dhaka City

Urban flooding can lead to fatalities in various ways. Aside from death, there are additional safety and health concerns. There are substantial economic costs associated with urban flooding catastrophes. Understanding these multifaceted consequences is crucial for developing effective flood management strategies. Several significant flooding events have affected Dhaka in recent years. Flood occurred on 12th July 2019 inundated major roads of the city. Heavy monsoon rains wreaked havoc in Dhaka on July 20, 2020. Because of the serious water-logging problem, activities in the country’s business area got severely affected, with many office goers, traders and workers falling behind their daily schedules. Pre monsoon showers inundated the roads of Dhaka city on June1. 2021.85mm rainfall between 6-9 am kept the city in knee deep water. Several rickshaw pullers were electrocuted while trying to move their rickshaw. Many parts of the city got inundated during the heavy rainfall on 24 October 2022 due to the effect of Sitrang. The most recent flood occurred on 12 July 2024 when 130 mm rainfall was recorded within just six hours. These flooding incidents often lead to a significant number of vehicle-related deaths, indicating that many victims may have been unaware of the imminent danger. Many injuries occur due to downed power cables, open manholes, falling trees, and encounters with stray animals (snakes, rodents, etc.) Another significant health concern associated with flooding is water contamination, as drinking water gets mixed with floodwater, causing excessive shortage of safe drinking water. During urban flooding events, the destruction of infrastructure, such as power failures, interrupted transportation services, and structural damages to the buildings and vehicles, further complicates the situation. Interruption in trades and business creates severe economic loss. Therefore, earlier warning alerts would be beneficial as to allow more time for preparedness and response.

In summary, the study area of Dhaka city presents a hydrologically complex environment characterized by intricate drainage challenges and persistent urban flooding issues. Understanding these dynamics and developing an effective urban flood forecasting system is essential for enhancing the city's resilience to future flooding events.

4. Approach, Methodology and Data Collection

4.1. Selection of Modelling Approach and Methodology

Urban flooding is a global issue affecting many cities due to rapid urbanization, inadequate drainage systems, and the impacts of climate change. Similar to Dhaka, other highly urbanized cities like Bangkok, Manila, and Jakarta face severe flooding due to monsoon rains, overburdened drainage systems, rapid urban expansion, and encroachments on floodplains [

37,

38]. Bangkok, with its low-lying topography and extensive canal system [

39], faces annual monsoon flooding like Dhaka. Both cities have implemented flood control systems, though Dhaka’s flood management strategies lag behind in terms of infrastructure maintenance and technological advancement [

40]. In contrast, Manila, another flood-prone city, has developed a hybrid flood mitigation strategy that combines structural measures (e.g., levees, floodways) with non-structural approaches, such as improved early warning systems and community-based flood preparedness [

41]. Dhaka, while making strides in flood forecasting, still lacks the comprehensive, city-wide flood defense systems that Manila has begun to implement. Furthermore, cities like Rotterdam and New York, which face different climate and geographic conditions, have taken proactive steps toward building climate resilience through innovative drainage solutions, such as green infrastructure and urban water plazas [

42]. While these cities show the significance of integrating flood management into urban planning, Dhaka's unique challenges—rapid urban growth, low-lying terrain, and high population density—require tailored approaches to flood mitigation that reflect local conditions. By comparing Dhaka’s flood dynamics with other urbanized cities, the broader significance of the current research becomes clearer. It highlights the need for integrated flood management strategies, such as those applied globally, to address the growing challenges posed by urbanization and climate change in developing regions like Dhaka.

There are more than a dozen software platforms available globally for urban flood modeling, each designed with specific strengths and applications. Among these, MIKE+ is selected for this study due to its robust capabilities in addressing the multifaceted nature of urban flood dynamics. Urban flooding in Dhaka is influenced by a complex interplay of rainfall-runoff interactions, riverine overflow from peripheral rivers, overland flow, and subsurface drainage systems. Effective modeling of these processes requires a tool that not only integrates surface and subsurface hydrology but also supports real-time data assimilation for flood forecasting. MIKE+ offers a distinct advantage over other software packages by providing advanced modules for simulating the interactions between these diverse components, making it well-suited for accurately capturing Dhaka’s unique flood characteristics. A detailed comparison of MIKE+ with other commonly used software is provided below to highlight its strengths in managing the complex flood scenarios prevalent in dense urban settings.

Integrated 1D/2D Modeling: MIKE+ excels in simulating interactions among surface runoff, river flow and subsurface drainage systems, which is critical in a city like Dhaka where the performance of stormwater networks significantly impacts surface flooding. HEC-RAS are strong for riverine flooding but lack comprehensive stormwater and sewer network modeling. MIKE+ allows seamless coupling of 1D/2D flows, making it more suitable for urban environments where both surface and drainage systems need to be modeled together.

Advanced Urban Features: Compared to SWMM, XP-SWMM, and SOBEK, MIKE+ provides a more robust platform for simulating complex stormwater drainage networks, River and 2D overland flow simultaneously. Dhaka’s urban landscape, with its varying topography and high-density infrastructure, demands detailed 2D surface modeling that MIKE+ handles more accurately using coupling option than SWMM, which is more limited in its 2D capabilities and there is no weir like couple structure.

Real-Time Flood Forecasting: MIKE+ supports real-time data integration, offers different types of data processing inbuilt tools and flood forecasting, making it invaluable for operational flood early warning systems. This is particularly important for Dhaka’s need for timely and accurate flood advisories. Other tools, like MIKE URBAN and SOBEK 1DFLOW, do not offer the same level of real-time functionality combined with urban system modeling.

Flexibility in Complex Urban Environments: MIKE+ provides flexibility in handling the wide range of urban drainage challenges found in Dhaka, including stormwater drainage, combined sewer systems, and overland flooding. While tools like InfoWorks ICM and TUFLOW also offer advanced features, MIKE+ offers an easier-to-use interface for integrated urban systems modeling, making it ideal for a large-scale urban area like Dhaka.

MIKE+ is selected for Dhaka’s urban flood modeling due to its superior integration of 1D/2D systems, advanced real-time forecasting capabilities, and flexibility in simulating complex urban drainage and surface water interactions. These features make it better suited than HEC-RAS, SWMM, XP-SWMM, MIKE URBAN, and SOBEK for addressing the specific flood management needs of Dhaka.

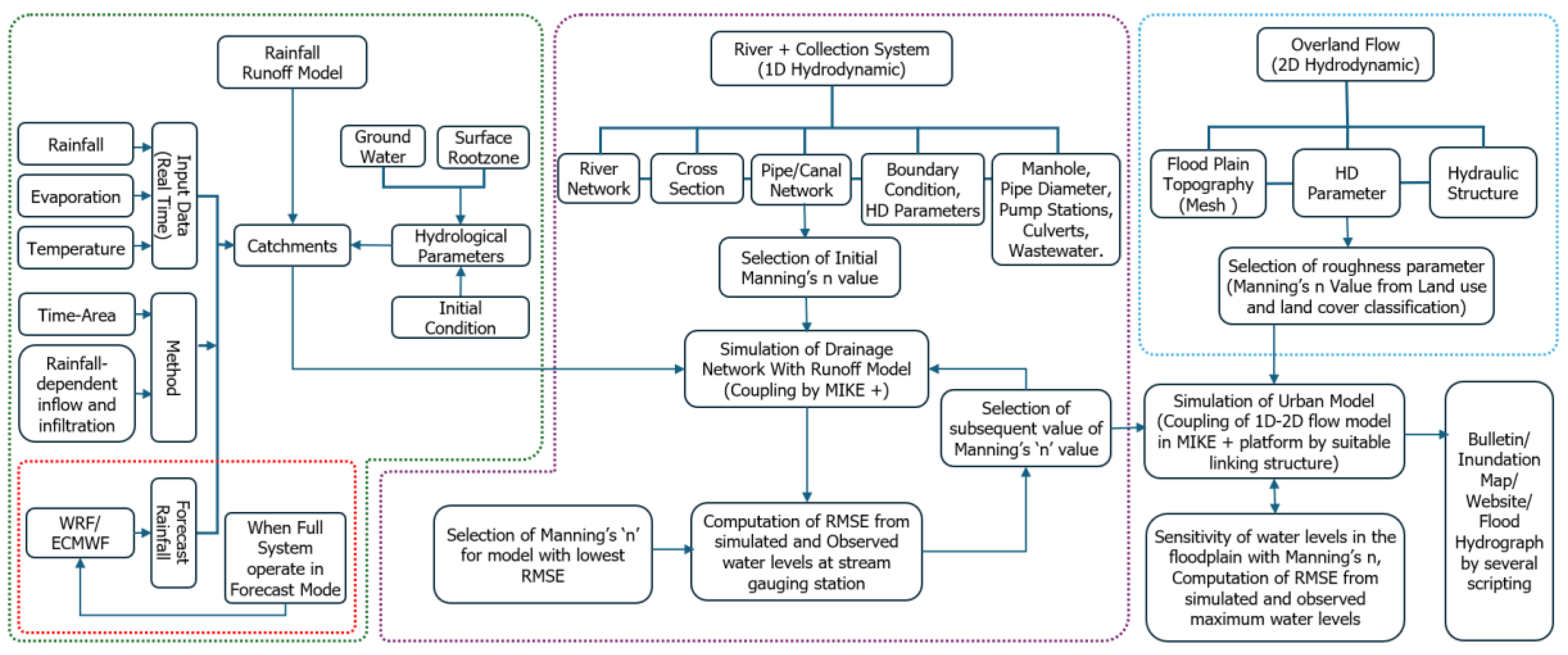

The approach adopted in the current research for developing the urban flood forecasting system for Dhaka city using MIKE+ software is conceptually shown in

Figure 3. The main steps of the proposed methodology include: (1) Data collection; (2) Development of Rainfall-Runoff Model; (3) Development of a 1D river+collection model coupled with Rainfall-Runoff model and its calibration; (4) Development of a 2D overland flow model, including assessment of 2D area’s roughness derived from land use and land cover classification via image processing; (5) Coupling of the 1D–2D models and sensitivity analysis of various modeling parameters and (6) Simulation the first four steps with forecasted rainfall for generating next 24 hours flood scenario in the Dhaka city.

4.2. Data Source:

Meteorological data including rainfall (3 hourly), evaporation (monthly historical), temperature (monthly historical) from Bangladesh Meteorology Department (BMD,

https://live6.bmd.gov.bd ), and hydrological data such as water level and discharge from Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB,

http://hims.bwdb.gov.bd/hydrology ) have been collected. Additionally, topographical information including land levels and cross-sections of drainage khals, sewerage network details, and information on drainage structures such as regulators and pumps, have been obtained from Dhaka Water Supply and Sewerage Authority (DWASA,

https://dwasa.org.bd ). Infrastructure data including roadways, railway levels, and flood protection embankments have also been surveyed by Institute of Water Modelling (IWM,

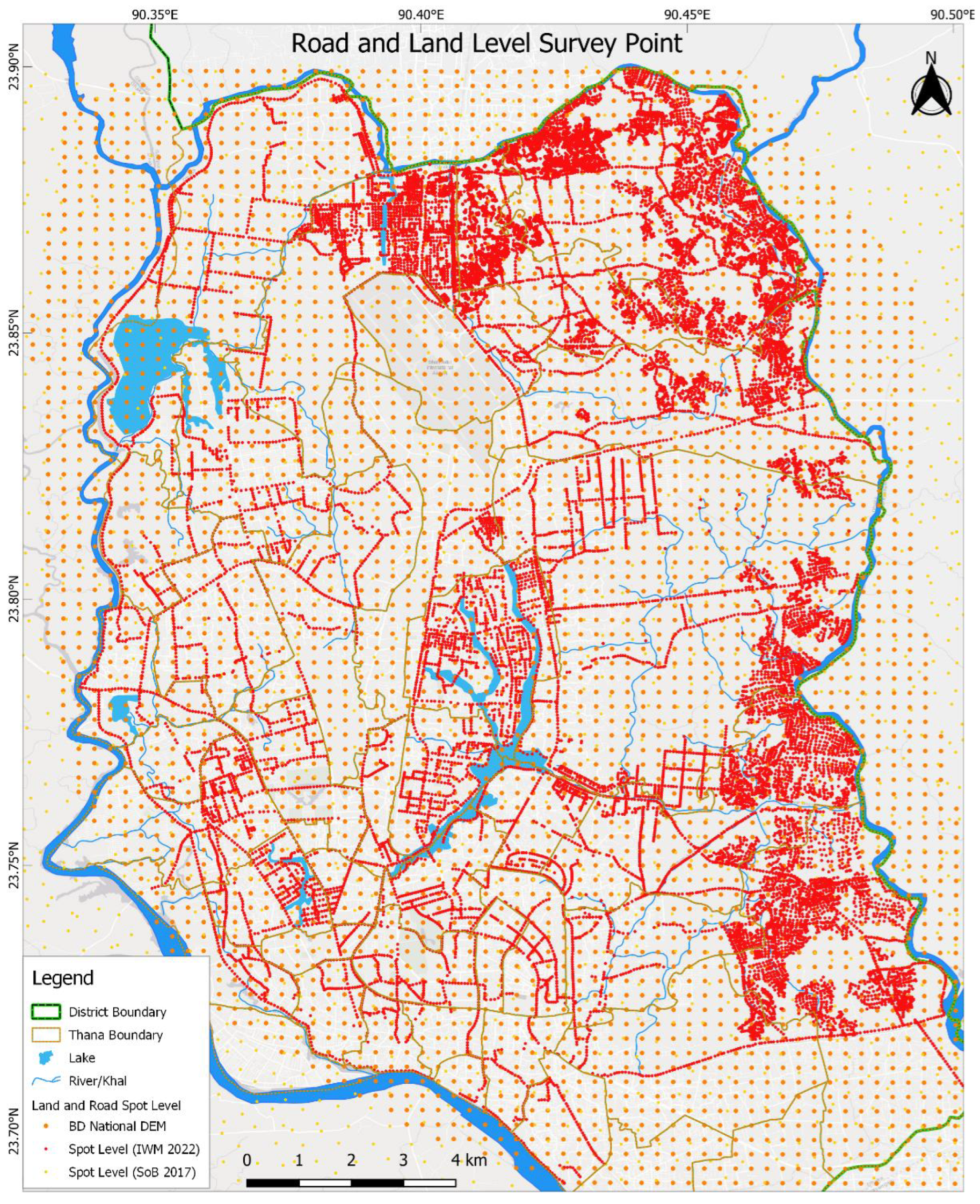

https://iwmbd.org ). All Collected data were meticulously checked using the standard procedure to ensure accuracy. Several field visits were conducted to oversee the quality control of survey procedures and verify the model. Under this study spot-level (

Figure 4) data is collected for correcting the existing DEM data of Dhaka city.

4.2.1. Data Collection for Rainfall Runoff Model

Real time and Forecast Weather Data: Several organizations produce weather forecasts for Dhaka City using simulations of numerical weather models. The Bangladesh Meteorological Department (BMD) simulates the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) (

https://live6.bmd.gov.bd/?/nwp-products-3km/&/wrf-model ) model to produce numerical weather predictions with a horizontal resolution of 3 km and a temporal resolution of 3 hours [

43]. In contrast, other models provide forecasts at much coarser resolutions. BMD's weather forecast is generated for three days, though the accuracy decreases with increasing lead time. A 24-hour BMD forecast is typically used in our study model to predict the flood situation for the subsequent 24 hours. An example of a one-day forecast is illustrated in

Figure 5 and 3 hourly real-time rainfall and temperature data is collected from BMD for model development.

4.2.2. Data Collection for 1D Hydrodynamic Model

Water Level and Discharge Data: Boundary condition time series for the peripheral rivers were obtained from multiple sources to accurately represent the hydrodynamic conditions of the river model of the study. Three upstream inflow (discharge) datasets and two downstream water level time series were collected from the Flood Forecasting and Warning Centre (FFWC). Additionally, intermediate water levels along the peripheral rivers, as well as water level measurements on both the city side and river side of the major pump stations, were collected for model verification from different sources. A detailed summary of these data sources and their use in the model is explained in

Table 1.

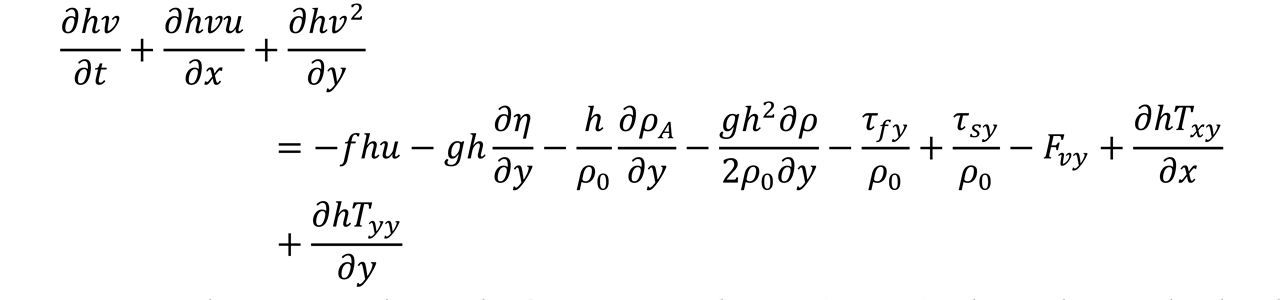

Cross-Section Data: In the MIKE+ river and collection system, the computational domain is represented as a series of cross-sections perpendicular to the flow direction[

44,

45]. To develop a 1D hydrodynamic model for Dhaka City, cross-sectional surveys of rivers and canals in the region have been conducted. Depending on field conditions, these surveys were carried out using either leveling instruments combined with sounding, echo sounders, or a combination of both. A total of 174 cross-sections from 11 different rivers and canals in and around Dhaka City were collected through field surveys, while an additional 169 cross-sections were obtained from the IWM database and other sources, as detailed in

Table 2 and

Figure 6.

Canal Network: A total of 120.25 km canal network including dimension has been collected from the DWASA and incorporated into the model.

Figure 6 and

Figure 12 are showing the canal distribution in the model.

Pipe Network and Manholes: 160.1 kilometer pipe network and 1161 nos manhole data are collected from Dhaka WASA and Dhaka Noth (

https://dncc.gov.bd ) and South City Corporation (

https://dscc.gov.bd ). The Efficiency of pipe networks based on the field observations is adjusted in the models. All manholes with different diameters are connected to the 2D domain that are shown in

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 12.

Figure 7.

Drainage zones, sluice gate, embankment and road network.

Figure 7.

Drainage zones, sluice gate, embankment and road network.

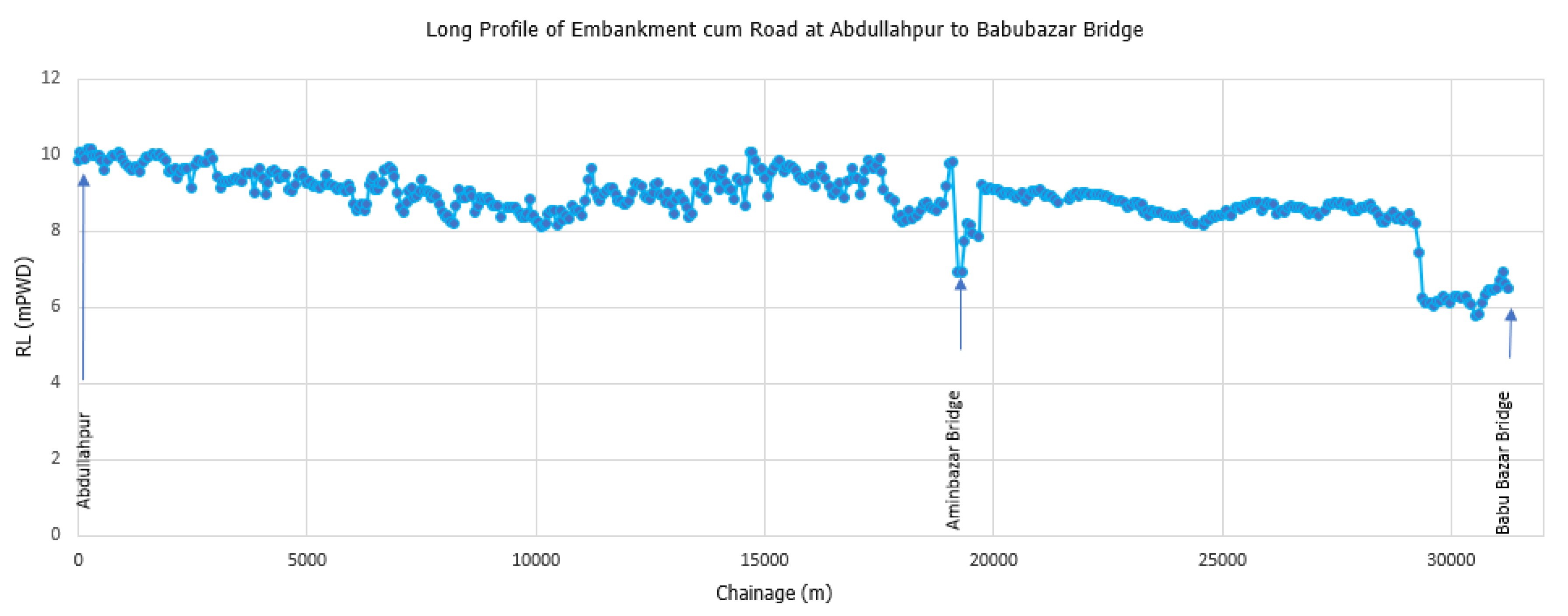

Hydraulic Structure: Khals inside Dhaka city is controlled by the different types of hydraulic structures, embankment crest level (

Figure 8), and pump stations. Various types of information about existing structures like invert level, gate height etc., have been collected from the field. The structural information incorporated into the model is shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 12.

Rule Curve of Pump Operation: There are four major pump stations in Dhaka city. All these pump stations have their own command area and specific rule curves. These rule curves are collected from the associate authority and incorporated into the model. The main purpose of these pump stations is to drain out the domestic water and runoff from the countryside to rivers.

Figure 6 shows the pump locations, command area and the connection with peripheral rivers.

4.2.3. Data Collection for 2D Overland Flow Model

Topography Data: The topography for the 2D overland flow model was developed using multiple data sources to ensure accuracy and detail. A 5m by 5m high-resolution Digital Elevation Model (DEM) was constructed by integrating the Bangladesh national DEM from the Institute of Water Modelling (IWM, iwmbd.org), recent spot level survey data obtained from the Survey of Bangladesh (SoB, sob.gov.bd), and road spot level data specifically collected for this research project in 2022. All datasets were thoroughly evaluated through field verification to ensure consistency and reliability.

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of spot level data points used in the model, demonstrating how these various sources were merged to generate a refined DEM that accurately represents the topographical features of the study area.

Water Retention Pond: All pump stations have their own retention pond. These retention ponds carry stormwater runoff and domestic water of residential areas and support wastewater treatment and prevent flooding. These retention ponds are included in the 2D domain by interpolation of survey spot level inside the retention ponding area. Retention ponds are connected to the pump stations and corresponding drainage canals and internal khals using standard links in the model. All retention ponds are shown in

Figure 6.

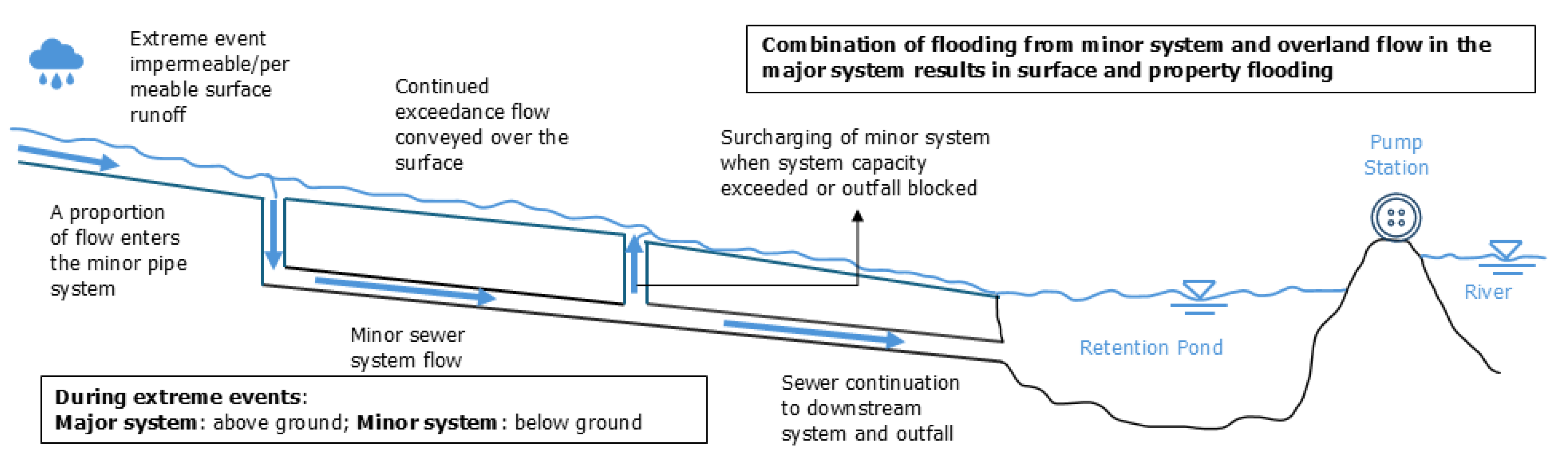

5. Model Development

The study relies on a combined approach of numerical modeling and GIS. The urban model of Dhaka City is a 1D-2D coupled model comprising three components: Rainfall -Runoff, 1D Hydrodynamic, and 2D Overland flow model. The three models have been integrated together and developed a 1D-2D coupled model of the study area. The models have been developed using MIKE+ software of the Danish Hydraulic Institute (DHI), Denmark [

46]. Rainfall-Runoff module simulates the local runoff generated by the rainfall, 1D Hydrodynamic module simulates the river and collection system (pipes and drainage network) and the 2D overland flow module simulates the flood propagation, inundation depth and flow velocity. The interaction among all the components is modeled in a MIKE+ platform which allows quick integration and detailed representation of free-surface flows over the streets.

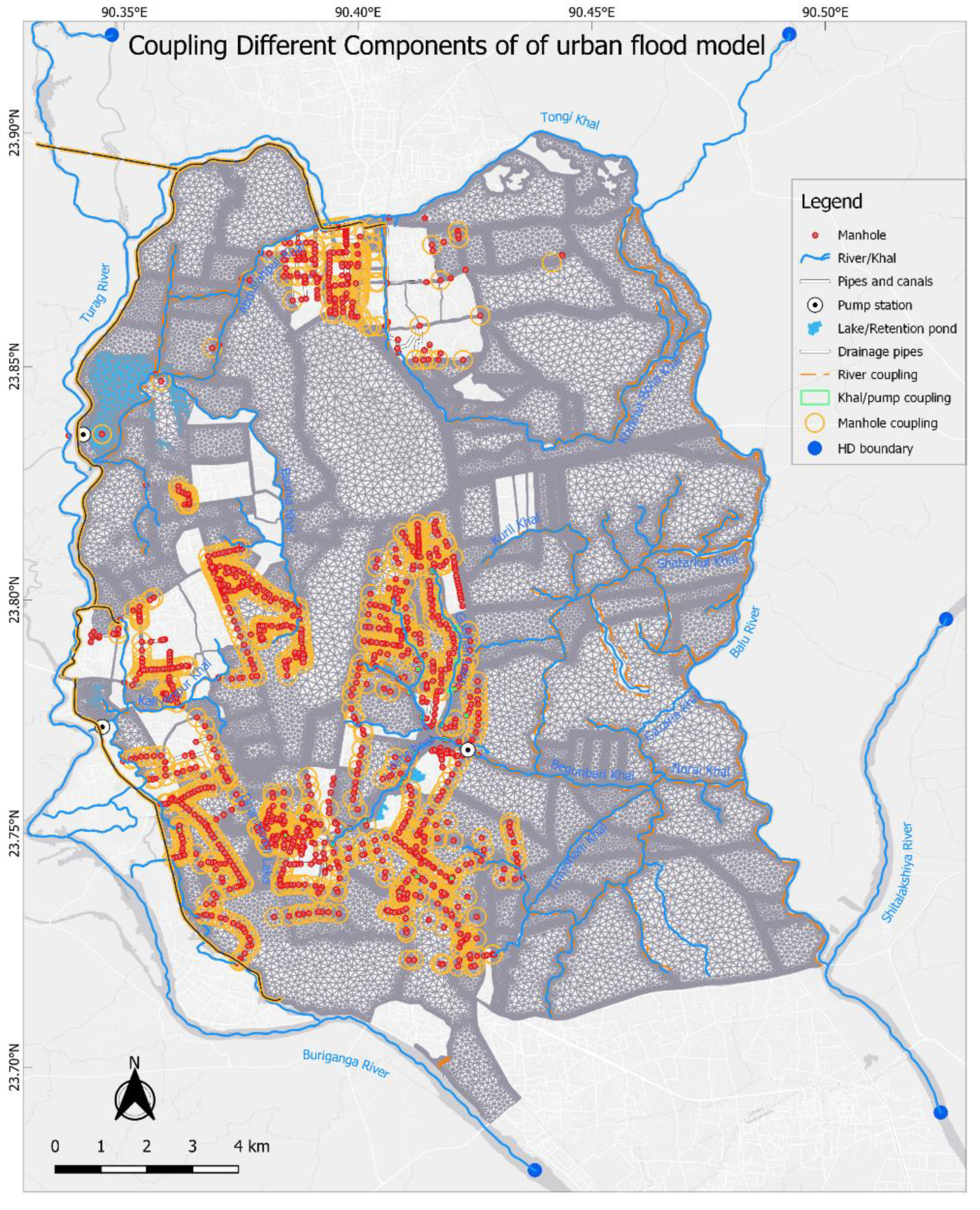

The total area of Dhaka city is around 261.67 sq. km. Drainage khal, manhole, drainage pipe, river, flood embankment, roads, hydraulic control structure etc., are the main features which have been included in the urban flood model. Considering all features, model domain, and complex water collection system of Dhaka city, the model has been developed step by step taking one drainage zone of Dhaka city at a time. Dhaka drainage system is divided into 20 drainage zones (

Figure 7) all of which have been added to the model.

5.1. Conceptual Background of Urban Flood Model:

MIKE+ (it is a new generation urban flood modelling tool developed by DHI) is a flexible system for modelling and design of water distribution networks, collection systems for wastewater and storm water and river networks with interaction of 2D overland flow (

Figure 9). Within the "Rivers, collection system and overland flows" working mode in MIKE+, the following features (those are needed to capture the dynamics of urban flood) are activated:

5.2. Rainfall Runoff Model

The RR module simulates hydrological processes on catchments. Hydrological models have two distinct classes of models.

5.2.1. Surface Runoff Model

MIKE+ includes a series of surface runoff models and one continuous hydro logical model. The surface runoff models available are:

These models are designed primarily for calculating surface runoff, producing hydrographs that reflect the immediate response to rainfall events, where flow begins with precipitation and ends shortly after rainfall stops. They are particularly suited for urban areas dominated by impervious surfaces and are effective for single-event analyses, such as assessing runoff from a specific design rainfall. However, these models are less applicable for rural catchments or long-term, multi-event simulations due to their inability to simulate continuous hydrological processes.

5.2.2. Continuous Hydrological Model

This model handles the full precipitation volume balance using complex methodologies, generating runoff that includes both overland and subsurface components. Consequently, the resulting hydrographs are nearly continuous over longer time scales. A key feature of continuous hydrological models is their "hydrological memory," which allows them to simulate the catchment's response to rainfall based on preceding events. This makes them suitable for long-term analyses and rural catchments. However, these models are less effective at simulating the rapid runoff response typically observed in heavily urbanized areas.

In this study, the Rainfall Dependent Infiltration (RDI) model is used as the continuous hydrological model and Time-Area Method (A) is used for the surface runoff model. Surface runoff models can be utilized independently or combined with RDI. When used together, runoff is calculated separately for each model and then summed to provide the total runoff. MIKE+ also allows combining different models for various catchments within a single runoff simulation, offering flexibility in hydrological modeling.

5.2.3. Time-Area Method (A) for Surface Runoff Model

In the Time-Area surface runoff method, runoff is influenced by initial loss, the contributing area, and continuous hydrological losses, which include evapotranspiration. Water balance is maintained by adjusting the reduction factor and initial loss values. The shape and timing of the runoff hydrograph are defined by the concentration time and the time-area (T-A) curve, which together represent the catchment's reaction speed and overall shape. Based on the catchment’s characteristics (e.g., percentage of impervious area) and hydrological parameters (initial loss and reduction factor), the model accurately simulates surface runoff.

A time-area curve represents the flow time from each sub-area of the catchment to the outlet. For irregularly shaped catchments, user-defined T-A curves can be applied to describe the basin more accurately. This allows for flexibility in modeling runoff behavior under varying catchment shapes and hydrological conditions. An example of the concept of the Time-Area model for simulating catchment runoff is illustrated in

Figure 10.

5.3. Conceptual Background of MIKE 1D Collection System

The MIKE 1D Hydrodynamic Pipe Flow Model solves the complete St. Venant (dynamic flow) equations throughout the drainage network (looped and dendritic), which allows for modelling of backwater effects, flow reversal, surcharging in manholes, free-surface and pressure flow, tidal outfalls and storage basins.

The MIKE 1D hydrodynamic engine is designed to handle any type of pipe network system with alternating free surface and pressurized flows as well as open channel network and pipes of any shape.

Virtually any construction can be described including pumps, weirs, orifices, inverted siphons, etc. The computational scheme uses an implicit, finite-difference numerical solution of the St. Venant flow equations. The numerical algorithm uses a self-adapting time-step, which provides efficient and accurate solutions in multiple connected branched and looped pipe networks. This computational scheme is applicable to unsteady flow conditions that occur in pipes ranging from small-profile collectors for detailed urban drainage, to low-lying, often pressurized, sewer mains affected by varying outlet water levels. Both sub-critical and supercritical flows are treated by means of the same computational scheme that adapts to the local flow conditions. In addition, flow phenomena, such as backwater effects and surcharges, are precisely simulated.

Figure 11 illustrates how the 1D CS (collection system: pipe, canal, manhole, and other structure) network operates.

5.4. Conceptual Background of 2D Overland Flow

MIKE+ 2D overland module uses DHI's 2D engine MIKE 21 FM. This engine solves the two-dimensional St. Venant (dynamic flow) equations, using a cell-centered finite volume method. The time integration is performed using an explicit scheme and the numerical solution uses a self-adapting time step for optimizing stability and simulation times. The spatial discretization can either be done through a rectangular grid or a flexible mesh. The 2D overland module can be used to simulate free-surface flows to describe detailed flows in channels or describe surface floods from e.g., surcharging collection system networks or rivers.

MIKE 21 Flow Model is a modeling system for 2-D free-surface flows. The two-dimensional model performs simulation on a two-dimensional grid. The two-dimensional grid can be a normal rectangular grid or a mesh. The modeling system is based on the numerical solution of the two/three-dimensional incompressible Reynolds averaged Navier-Stokes equations subject to the assumptions of Boussinesqand of hydrostatic pressure. Thus, the model consists of continuity, momentum, temperature, salinity and density equations and it is closed by a turbulent closure scheme.

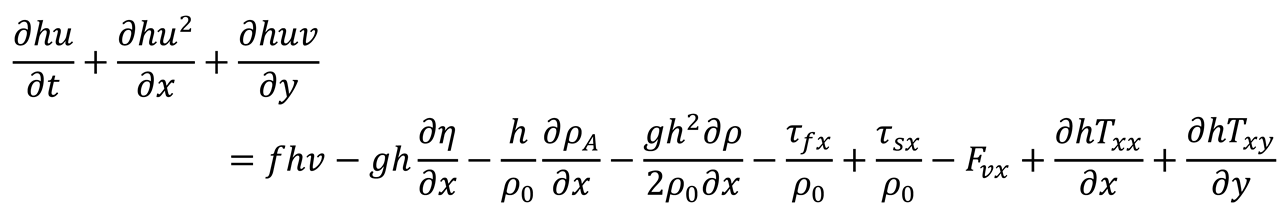

The two-dimensional shallow water equations in conservative form can expressed as

Here, t is the time; x and y are the Cartesian coordinates; ℎ = η + d is the total water depth, where η is the surface elevation and d is the still water depth; u and v are the depth averaged velocity components in the x and y direction; f = 2Ωsinϕ is the Coriolis parameter (Ω is the angular rate of revolution and ϕ the geographic latitude); g is the gravitational acceleration; pA is the atmospheric pressure at the free surface; ρ is the density of water; ρ0 is the reference density of water. (τfx, τfy) are the x- and y- components of the stresses due to bottom friction, surface friction and flow resistance. and (τsx, τsy) are the x- and y-components of the surface stresses due to the wind. Fv = (Fvx, Fvy) is the drag force due to vegetation. The lateral stresses, Txx, Txy and Tyy, include viscous friction, turbulent friction, and differential advection. They are estimated using an eddy viscosity formulation based on the depth averaged velocities.

5.5. Conceptual Background of 1D/2D Overland Flow

In the coupled 1D/2D MIKE FLOOD model, the main river stretch is simulated using a 1D approach, while the floodplain is represented with a 2D modeling approach. MIKE FLOOD plays a tight coupling technique, where the 1D and 2D domains are integrated on a time-step basis to ensure consistent interaction between the two domains. The connection between the 1D river model and the 2D floodplain model is established using lateral structures, allowing for an accurate representation of flow exchanges between these domains [

49]. The main river stretch is modeled using the 1D Saint-Venant (shallow water) equations, which consist of the continuity and momentum equations, as presented in Equations (4) and (5).

Here, A, Q, S0, and Sf represent the cross-sectional area (m2), water flow rate (m3/s), riverbed slope, and energy slope, respectively. Additionally, flow in the floodplain is computed using the 2D continuity and momentum equations, as provided in Equations (1)–(3).

5.6. Model Setup

MIKE+ consists of three main modules: (a) rivers, collection systems, and overland flows; (b) SWMM5 for collection systems and overland flows; and (c) Water Distribution. In this study, the first module has been utilized which can simulate surface runoff, river, canal and drainage systems along with overland flows to represent the complete flood dynamics. Under this module, there are four features:

Catchment: A hydrological model for simulating surface runoff within the catchment using various methods of MIKE+.

Collection system network: A 1D hydrodynamic model capable of simulating pressure flow and backwater effects in drainage systems with various structures, incorporating both stormwater and domestic water inputs.

River Network: A pure 1D hydrodynamic model that operates simultaneously with the collection system and catchment runoff, enabling interaction between these systems.

Overland Flows: A 2D hydrodynamic model for floodplains and urban areas that simulates surface flooding and dynamically interacts with the river network and collection system using different linking structures.

The processing of the data for simulation in the MIKE+ hydrodynamic model (rivers, collections system, and overland flows) involves, preparation of the river network, cross- section, collection network, catchment runoff model, boundary condition data, mesh generation (for overland flows) and coupling between 1D and 2D by different links and structures are described step by step below.

5.6.1. Surface Runoff Model

Surface Runoff Model has been developed using MIKE+ RR module. Basic steps are adopted in developing surface runoff model:

Delineation of sub-catchments

Choosing runoff model and parameters

Connection with canal and river.

886 sub-catchments have been included in the surface runoff model (

Figure 6).

5.6.2. River Network

The River Network file allows to 1) define the river network and reference cross-sections and hydraulic control structures to the network [

50]; and 2) graphically obtain an overview of the model information in the current simulation [

51].

Figure 12 shows the detailed river network.

Figure 12.

1D hydrodynamic network coupled with 2D hydrodynamic model: lateral, standard, and manhole couplings with the floodplain.

Figure 12.

1D hydrodynamic network coupled with 2D hydrodynamic model: lateral, standard, and manhole couplings with the floodplain.

5.6.3. Cross-Section

The Cross-Section file contains streambed and canal cross-sections at specified locations along a river network and canal. The geometry of cross sections is obtained from a field-surveyed or Digital Elevation Model and it provides detailed spatial representation that is essential for accurate hydraulic modeling [

52].

Figure 6 is showing the detailed cross-section distribution in the 1D network system.

5.6.4. Collection System

The Collection (Pipe and canal) Network file allows the modeler to define the collection network and reference cross-sections or shapes of the canal and control structures to the collection network. Detailed collection network along with structure and river network for this study model is shown in

Figure 12. Zone wise total length of the collection system and structure are available in the

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 those are used in this network model.

5.6.5. Mesh Generation

The MIKE 21 FM (another module of MIKE Zero platform) model features an integrated mesh generator that constructs meshes using both triangular and quadrilateral elements, facilitating flexible spatial resolution to accurately represent complex geometries, including retention pond, bathymetric features of river, road and open area that are room for storing rainwater. Flexible mesh is used in this study. High-resolution meshes are applied in critical areas with steep gradients, road and flood vulnerable areas, while coarser meshes are used in less sensitive regions to optimize computational resources that is illustrated in

Figure 12. Each element represents one calculation node. The quality of the mesh, particularly in terms of element shape and smooth size transitions, is vital for ensuring model stability and accuracy [

53]. After finalizing the mesh, developed dem data (section 4.2.3) is used to prepare the topographic surface of the 2D model.

5.6.6. Develop 1D/2D Linked Urban Flood Forecasting Model

Through MIKE+, the benefits of 2D and 1D modelling has been utilized in an integrated model where complex networks and channels represented in 1D are coupled to an overland surface representation in 2D. Models of collection systems and river networks have also been coupled to models of the overland surface as shown in

Figure 6 and

Figure 12.

After defining the couplings, an integrated model is done taking stormwater pipes, open channels and the overland surface in account. Following 1D model components are linked to the 2D surface:

Manhole

Basin Outlet

Pump

Weir

Natural channel

River bank

River end

5.6.7. Hydrological Boundary:

Rainfall: Observed rainfall data in a 3-hour interval measured by BMD is used in the model as the hindcast period in the model.

Temperature: Historical monthly average temperature data is used in the model. This data is calculated from BMD observed data.

Forecast rainfall: BMD predicted 3 km by 3 km meter forecast data has been processed as catchment average time series in 3 hours interval for each basin by external python script.

5.6.8. Wastewater Boundary Conditions

Domestic and sewage water volumes are estimated based on the population within each catchment and the per capita water usage. These calculated wastewater volumes are subsequently incorporated into the nearest pipe network or canal, representing domestic water use in the model [

54].

5.6.9. Peripheral River Boundary

There are five open boundaries in the 1D model: three inflow boundaries from upstream and two water level boundaries are located downstream of the model. These five boundaries are collected from the Bangladesh Super Model (this model is run every day as a flood forecasting model at FFWC) [

55].

5.7. Initial Condition

The initial water level in the model has been taken from the peripheral river gauge and the pump station gauge water level is used for the countryside of the model. Drainage efficiency is also incorporated into the model based on field survey data. When running the model in forecast mode, the simulated results from the previous day are utilized as the initial conditions.

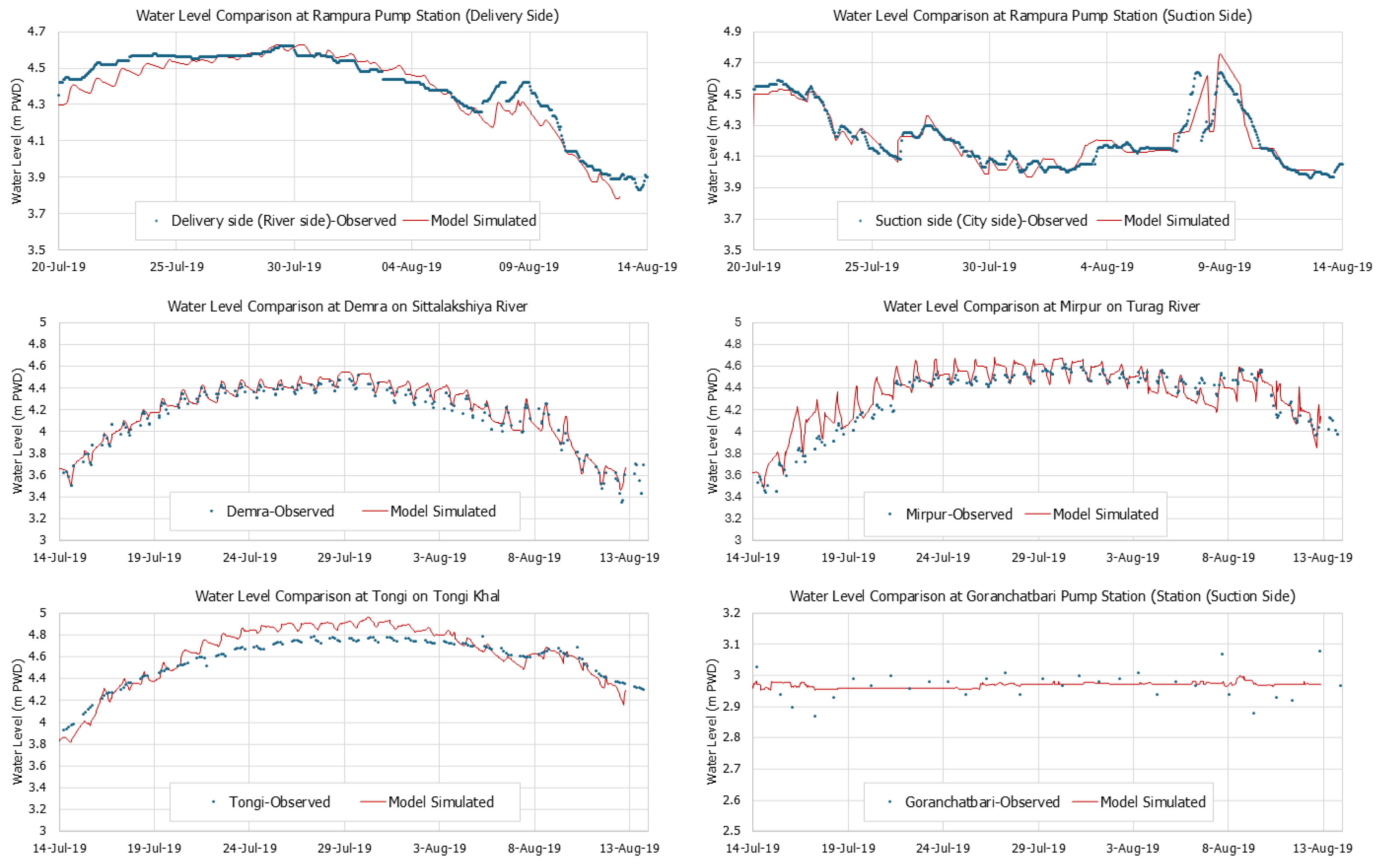

5.8. Calibration and Validation

The Dhaka urban flood model was simulated for the monsoon seasons spanning from 2019 to 2022. Calibration was performed using observed data from the 2019 monsoon period, while the 2022 monsoon season was utilized for model validation. Water level measurements from a major pump station within Dhaka city, recorded at both the delivery side (river side) and suction side (city side), served as primary calibration and validation points (

Figure 13). Additionally, observed water levels from peripheral river stations were incorporated to enhance model accuracy. To further evaluate model performance under diverse flood conditions, the model was tested using two significant flood events from 2020 and 2021. Flood levels from these events were cross-validated using flood marks collected through field consultations with local residents, shop owners along main roads, and corroborated with reports from local newspapers. All model simulations and subsequent analyses were conducted at a 30-minute temporal resolution, providing detailed insights into urban flood propagation dynamics and the interactions between surface runoff and drainage systems.

5.8.1. Challenges in Model Calibration

Dhaka city’s landuse is highly heterogeneous, with significant variations in permeability between different zones. The eastern part is relatively more pervious due to limited urbanization, whereas the central and western part is predominantly impervious owing to extensive urban development. To account for these spatial differences, distinct runoff models were applied to various sub-catchments based on drainage patterns and landuse characteristics. In some catchments, a hybrid runoff modeling approach combining the RDI (Rainfall-Dependent Inflow) and Time-Area method was employed, as illustrated in

Figure 14. A major challenge in calibrating the urban flood model is the limited availability of in-situ discharge data, with only a few water level monitoring stations scattered within the study area (

Figure 13). In the absence of sufficient discharge data, water level serves as the primary calibration variable, representing the integrated response of all model components at selected locations (

Figure 13). Although calibrating solely with water levels and flood marks can introduce uncertainties, this study addresses this challenge by simulating multiple historical rainfall events and validating the results through comparison with community-reported flood observations and available water level data. This iterative approach helps to mitigate some of the inherent uncertainties associated with modeling in ungauged urban areas and improves the reliability of flood predictions under different rainfall scenarios.

5.8.2. Model Sensitivity and Calibration

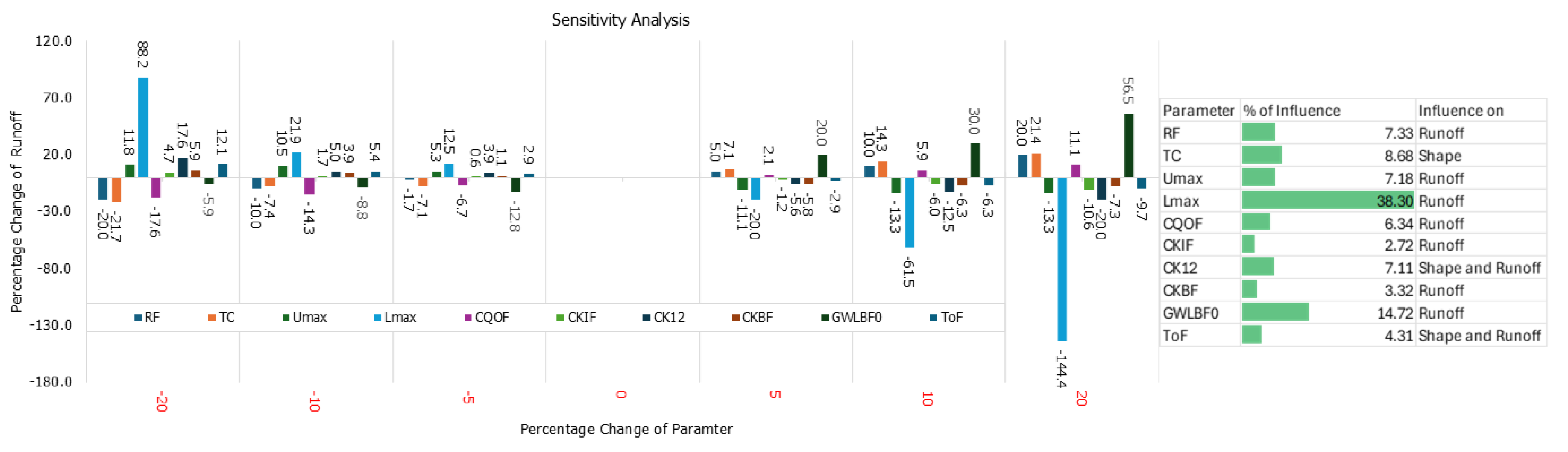

The urban flood model involves a complex set of parameters, many of which are associated with significant uncertainty, making comprehensive calibration challenging. To address this, an iterative calibration approach was employed, starting with a broad range of parameter values. A series of model runs were conducted systematically, varying each parameter incrementally and detrimentally to assess its impact on model outputs. The percentage change in outputs relative to the baseline helped identify the most sensitive parameters for further analysis. Simultaneously, Manning’s roughness coefficients (M values) for the drainage network, canals (khals), and rivers were fine-tuned to capture local hydraulic characteristics accurately. This parameter screening and refinement process continued iteratively, narrowing down the parameter ranges until a satisfactory match was achieved at the calibration points.

Figure 15 illustrates the sensitivity analysis results for selected parameters;

Table S1 (in Supplementary Material) lists the calibrated parameters along with their optimized values and

Table 3 and

Figure 16 show the model calibration statistics and graphical water level comparison for 2019. This approach ensures that the model is well-tuned, despite the inherent complexities and uncertainties associated with urban flood modeling.

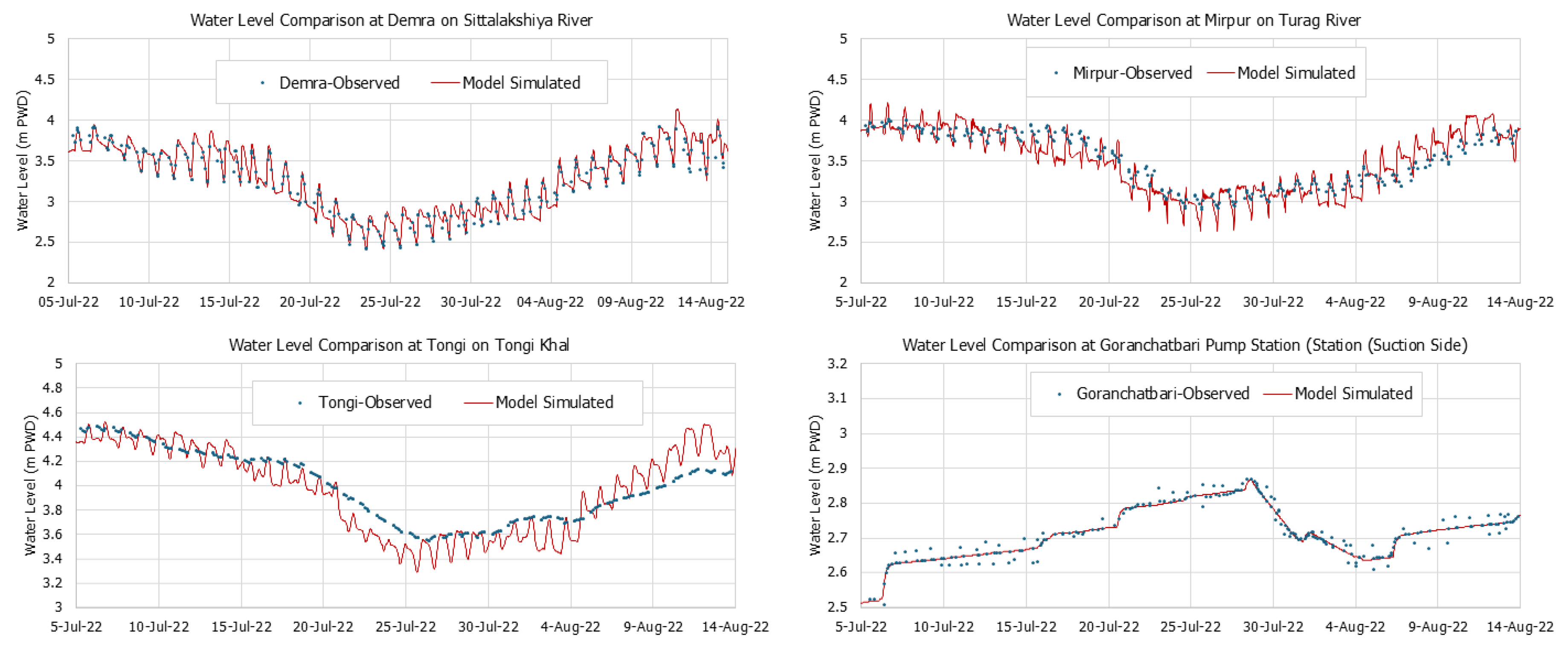

5.8.3. Model Verification

The reliability and efficacy of urban flood models used for real-time forecasting based on weather forecast data can be tested by comparing the similarity in observed and simulated water level.

Figure 17 shows the water level comparison at few stations inside model domain and peripheral rivers of Dhaka city and

Table 4 the model performance statistics at these points. This model is also simulated for 2020 and 2021 flood events and model results have been matched with flood marks by the local people and local news information.

Table 5 shows model verification by inundation information with local people and local newspapers.

Figure 18 shows major urban flood event inundation maps.

In summary, the developed model demonstrates strong performance during both the calibration and validation phases as indicated by an Index of Agreement (IA) greater than 0.75, Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) exceeding 0.65, and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) below 0.1. Additionally, the model’s results show good alignment with field observations and reports from local communities and newspapers.

6. Forecast Products

The primary objective of this study is to develop flood inundation maps for the entire Dhaka City and generate area-specific and road-specific advisory bulletins to highlight waterlogging-prone areas during heavy rainfall events. The urban flood forecasting model was configured to simulate several flood events using a combination of observed rainfall data for the hindcast period (3 days prior to the forecast) and Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model-predicted rainfall data for the subsequent 24 hours. An automated system, developed using Python scripts, facilitates real-time data acquisition and processing from the Bangladesh Meteorological Department (BMD) website and server. This automation enables seamless data integration and model execution whenever a potential flood event is anticipated.

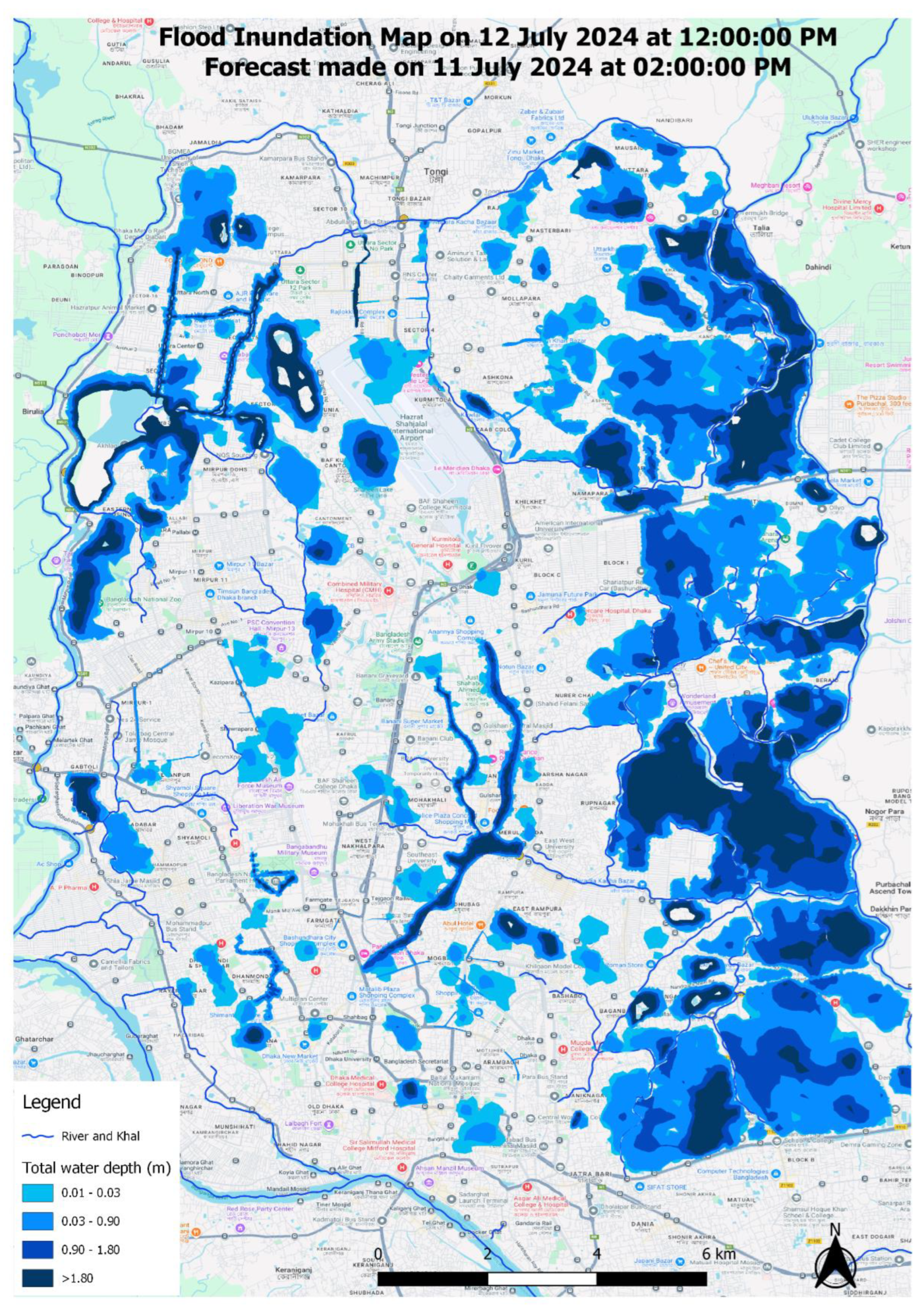

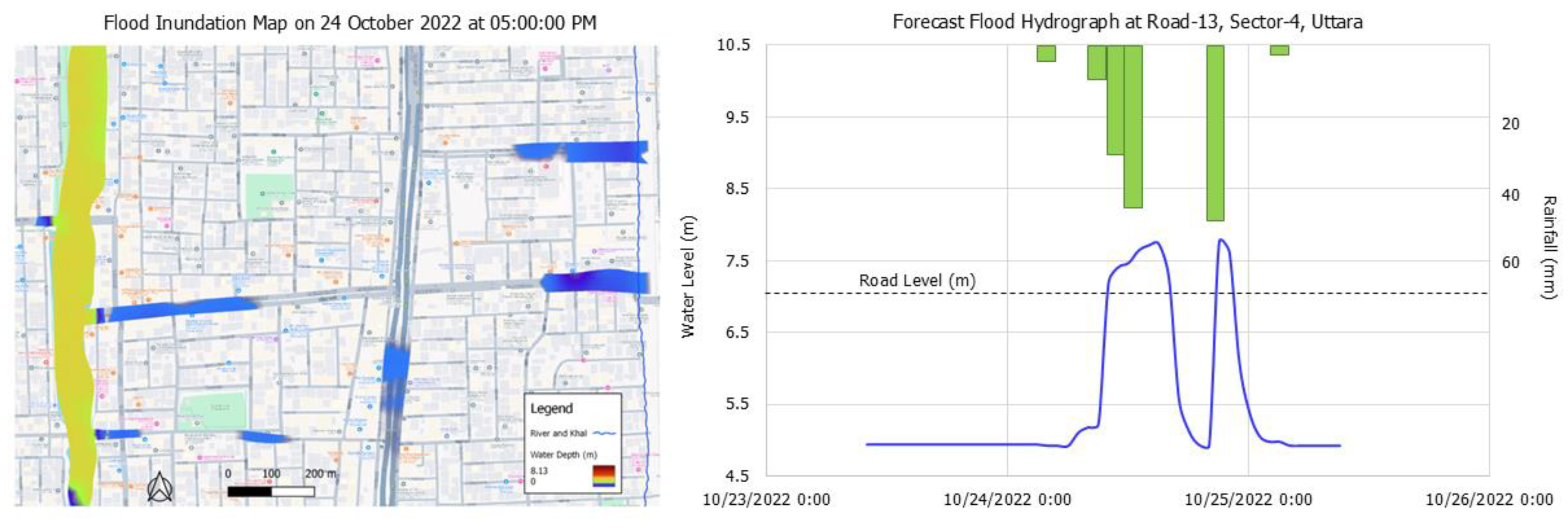

The model was tested using two significant torrential rainfall events: on October 24, 2022 (146 mm) and July 12, 2024 (130 mm), both successfully simulated a day in advance using WRF forecasted rainfall data.

Figure 19 illustrates a typical inundation map generated on July 11, 2024, to predict flood conditions, and

Table 6 presents the corresponding flood bulletins, validated against field observations after the events.

Figure 20 further depicts area-specific and road-specific bulletins, providing detailed flood information for major roads on 24 October 2022, thereby enhancing the utility of the forecasting system for targeted flood risk communication and emergency response planning.

7. Discussion

This study was conducted using a limited dataset, comprising topographic information, observed water levels, and river and canal cross-sections. The 2D floodplain model was updated using the most recent survey data, with a particular focus on accurately capturing road crest levels to enhance the precision of the flood simulation. However, the model's accuracy is highly dependent on the quality of the terrain data, and certain areas were not fully represented due to the inherent limitations of the available topographic information. In addition, Dhaka currently has only one rainfall gauge station, which was used for model development and for the hindcast period during forecast runs. Despite this constraint, the model demonstrated a strong correlation between observed and simulated water levels, both within the model domain and along the peripheral rivers.

For the forecast period, the model utilized 3 km by 3 km resolution weather data, which is suitable for capturing large-scale storm systems and prolonged rainfall events, such as those associated with depressions in the Bay of Bengal. These types of widespread rainfall patterns are typical for Dhaka, and the model performed well in simulating such events. For example, during Cyclone Sitrang (October 24, 2022), the city experienced heavy rainfall across its entire area, and the model successfully replicated the observed flood extent. However, the current spatial resolution and limited rainfall gauge coverage are insufficient to capture localized convective storms that can cause intense, short-duration flooding. Using higher-resolution weather forecast data (e.g., 1 km or finer) would enable the model to better represent spatial variability in rainfall, which is crucial for a complex urban environment like Dhaka, where microclimatic variations and the Urban Heat Island effect can significantly influence localized precipitation patterns [

56,

57].

The model includes 886 hydrological sub-catchments, each delineated to represent local drainage systems. This setup allows the model to integrate high-resolution data and capture spatial variations effectively. Therefore, if finer resolution weather data becomes available in the future, the model is expected to perform well for localized flood events as well. To improve the accuracy of the model for smaller-scale events, it is essential to increase the density of rainfall gauge stations across the city to provide better spatial coverage.

Another critical challenge in Dhaka is the frequent blockage of the drainage and pipe network, which can exacerbate flooding, particularly during intense rainfall events. Implementing a regular or real-time monitoring system, such as camera-based surveillance or sensor networks, would allow for the early detection of blockages and enable timely interventions. Incorporating dynamic drainage conditions into the model would further improve its predictive accuracy, providing a more comprehensive tool for flood forecasting and urban flood risk management in Dhaka.

The urban flood forecasting system developed in this study for Dhaka can be adapted for other cities in Bangladesh that face frequent flooding. For example, Chattogram, as a coastal city, experiences urban flooding exacerbated by tidal surges and high rainfall during the monsoon season [

58]. Adapting the model for Chattogram would involve incorporating tidal interactions and storm surge data alongside rainfall inputs.

Similarly, Khulna and Sylhet, which also experience frequent urban flooding, could benefit from similar flood forecasting models tailored to their respective flood mechanisms. While in Sylhet, flash flooding from upstream rivers and heavy local rainfall would require different modeling approaches [

59]. By applying the model to these cities, it can serve as a blueprint for a national flood forecasting and early warning system, contributing to the broader goal of disaster risk reduction across Bangladesh.

8. Conclusions

8.1. Summary of Findings

This study developed an urban flood forecasting system for Dhaka City using the MIKE+ hydrodynamic model, which integrates real-time hydrological and meteorological data to predict flood inundation, depths and durations. The model was calibrated and validated using historical flood events from 2019 to 2022, achieving strong performance metrics, including a Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) greater than 0.65, a Coefficient of Determination (R²) above 0.80, and a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of less than 0.1 meters. These results demonstrate the model's ability to accurately simulate widespread rainfall events, such as those caused by depressions and monsoons, which are common in Dhaka.

The study also highlighted the challenges of limited rainfall gauge data, relying on the integration of Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model data to capture broader weather patterns. Despite this limitation, the model successfully forecasted significant rainfall events, such as the torrential rainfall on October 24, 2022, and July 12, 2024 those are also verified with field survey data after the events.

Additionally, the model's utility extends beyond flood prediction, as it provides valuable outputs such as area-specific and road-specific advisory bulletins, aiding real-time decision-making, enhancing emergency response and minimizing the traffic congestion. The findings underscore the importance of improving data infrastructure, particularly by increasing the number of rainfall gauges across the city, high resolution weather forecast data and detailed topography, to enhance model accuracy for localized convective storms. Overall, the study demonstrates the model’s potential to contribute to proactive urban flood management and disaster preparedness in Dhaka and similar rapidly urbanizing cities.

8.2. Practical Implications of the Model

The findings of this research present several practical implications for water resource engineers, policymakers, and city authorities, particularly in the context of urban flood management in rapidly growing cities like Dhaka.

For water resources engineers, the flood forecasting model developed in this study provides a reliable tool for real-time flood prediction. Engineers can use this model to simulate various flood scenarios. By integrating high-resolution weather forecast data with advanced hydrodynamic modeling, engineers can enhance flood preparedness and mitigate the impacts of extreme weather events. Engineers can assess the performance of existing drainage infrastructure. The model also supports the evaluation of potential interventions, such as improved stormwater management practices and flood control structures, helping engineers design more effective solutions to prevent urban flooding. Engineers can collaborate with city authorities and disaster management agencies by using forecast data to ensure integration of engineering solutions with emergency response strategies. By trend analysis and historical inundation record, engineers and urban planners can develop long term urban planning and infrastructure development.

For policymakers, the research provides valuable insights into the growing vulnerability of urban areas to flooding due to climate change and urbanization. The model can serve as a critical tool in city planning, enabling policymakers to make informed decisions on urban development and land use planning. For instance, the flood hazard maps produced by the model can provide indication of flood-prone areas. This can help in implying restrictions on construction in high-risk zones. Furthermore, policymakers can also leverage the model to prioritize investments in flood infrastructure and identify the most affected areas, ensuring resources are allocated to the regions with the highest flood risks.

For city authorities and disaster management agencies, the flood forecasting system can be integrated into early warning systems to improve flood response and minimize the loss of life and property during flood events. The model’s ability to predict flood inundation areas and depths can support more efficient evacuation planning and resource allocation during emergencies. City authorities can use the output from the model to manage traffic more efficiently. Additionally, the forecasting system could be used to develop public awareness campaigns, enabling residents to take proactive measures before floods occur. The model also offers authorities a way to monitor and assess the effectiveness of existing flood control measures, ensuring ongoing improvements in flood management strategies.

This research provides a practical framework for engineers to improve flood infrastructure and early warning systems, help policymakers to shape urban planning and development, and support city authorities to enhance flood response and preparedness. This multi-level applicability makes the research a valuable resource for improving urban flood resilience in Bangladesh and beyond.

8.3. Future Outlook

Despite the insights gained from this study, several gaps remain that warrant further exploration. Few key recommendations from this study to further advance flood prediction accuracy are:

Higher resolution forecast data can be used to explore the model’s ability of detecting local convective rainfall events.

Refined DEM can be used to examine the accuracy of the model.

Acknowledging the need for a comprehensive approach, the study recommends the development of a hybrid model that integrates time-series data for machine learning-based algorithms with the expertise of numerical modeling.

To develop a more realistic representation of blockage dynamics, a systematic approach integrating real-time monitoring data (e.g., using cameras or sensors to detect blockages) into the model, coupled with a rule-based dynamic adjustment of network capacities could be considered to improve the model’s ability to capture real-world drainage conditions under varying blockage scenarios.

Though the design of flood forecasting and warning system (FFWS) is technical, its implementation depends on non-technical aspects as well. These include resource collection, evacuation planning, transportation facilities, warning dissemination, communication systems, electrical infrastructure, shelters, food and clothing supplies, medical resources, etc. Therefore, it is essential to integrate both technical and non-technical aspects seamlessly to reduce the casualties of floods.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K.M., M.S.H. and N.S.; Data curation, M.S.H. and T.K.M.; Formal analysis, M.S.H., N.S., L.C.M. And S.I.; methodology, M.S.H., N.S., T.K.M. and M.S.H.; project administration, T.K.M. and M.S.H.; software, N.S., S.I, M.S.H. and L.C.M; validation, N.S., T.K.M. and M.S.H.; visualization, N.S., T.K.M. and M.S.H.; data analysis, N.S., S.I and L.C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.H., N.S and T.K.M; writing—review and editing, M.S.H., T.K.M., N.S., S.M.A., A.S.K., M.S.H, S.U.R. and M.A.B.; supervision, T.K.M., S.M.A., M.A.B., A.S.K. and S.U.R.; funding acquisition, T.K.M., S.M.A. and M.A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Embassy of Denmark in Bangladesh under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), Denmark (Project no. 286717, Grant no. 286987).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere gratitude to the Royal Danish Embassy for their financial support, which made this research possible. We also extend our thanks to (Danish Hydraulic Institute, Denmark) DHI for providing technical support in developing this study model. We are grateful to the Flood Forecasting and Warning Centre (FFWC) and the Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB) for their invaluable technical assistance. Additionally, we acknowledge the Institute of Water Modelling (IWM) giving us the opportunity to use the software and data for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Galloway, G.E.; Reilly, A.; Ryoo, S.; Riley, A.; Haslam, M.; Brody, S.; Highfield, W.; Gunn, J.; Rainey, J.; Parker, S. The growing threat of urban flooding: A national challenge. College Park and Galveston: University of Maryland and Texas A&M University 2018.

- Rainey, J.L.; Brody, S.D.; Galloway, G.E.; Highfield, W.E. Assessment of the growing threat of urban flooding: A case study of a national survey. Urban Water Journal 2021, 18, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenberth, K.E. The Impact of Climate Change and Variability on Heavy Precipitation, Floods, and Droughts. In Encyclopedia of Hydrological Sciences; 2005.

- Eekhout, J.P.C.; Hunink, J.E.; Terink, W.; de Vente, J. Why increased extreme precipitation under climate change negatively affects water security. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 22, 5935–5946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabari, H. Climate change impact on flood and extreme precipitation increases with water availability. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 13768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, P.; Arnbjerg-Nielsen, K.; Olsson, J.; Nguyen, V.T.V. Climate change impact assessment on urban rainfall extremes and urban drainage: Methods and shortcomings. Atmospheric Research 2012, 103, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pregnolato, M.; Ford, A.; Robson, C.; Glenis, V.; Barr, S.; Dawson, R. Assessing urban strategies for reducing the impacts of extreme weather on infrastructure networks. Royal Society Open Science 2016, 3, 160023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, E.A.; Keys, P.W.; Booth, D.B.; Hartley, D.; Burkey, J.; Steinemann, A.C.; Lettenmaier, D.P. Precipitation extremes and the impacts of climate change on stormwater infrastructure in Washington State. Climatic Change 2010, 102, 319–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.A.; Easson, G. Potential Impacts of the Growth of a Megacity in Southeast Asia: A Case Study on the City of Dhaka, Bangladesh. In Handbook of Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation; Springer: 2022; pp. 2731–2758.

- Dasgupta, S.; Zaman, A.; Roy, S.; Huq, M.; Jahan, S.; Nishat, A. Urban Flooding of Greater Dhaka in a Changing Climate: Building local resilience to disaster risk; World Bank Publications: 2015.

- Ahmed, S.; Meenar, M.; Alam, A. Designing a Blue-Green Infrastructure (BGI) network: Toward water-sensitive urban growth planning in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Land 2019, 8, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleda, S.; Mowla, Q.A.; Murayama, Y. Dhaka metropolitan area. Urban Development in Asia and Africa: Geospatial Analysis of Metropolises 2017, 195-215.

- Gain, A.K.; Mojtahed, V.; Biscaro, C.; Balbi, S.; Giupponi, C. An integrated approach of flood risk assessment in the eastern part of Dhaka City. Natural Hazards 2015, 79, 1499–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqua, A. Development of integrated landscape framework at land-water interface for water sensitive urban design in the eastern fringe of Dhaka metropolitan area. 2021.

- Mark, O.; Apirumanekul, C.; Kamal Mir, M.; Praydal, G. Modelling of Urban Flooding in Dhaka City. In Urban Drainage Modeling; Proceedings; 2012; pp. 333–343.

- Bakhtiari, V.; Piadeh, F.; Chen, A.S.; Behzadian, K. Stakeholder analysis in the application of cutting-edge digital visualisation technologies for urban flood risk management: A critical review. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 121426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohani, F.H.; Alkhodre, A.B.; Sen, A.A.A.; Ramazan, M.S.; Alzahrani, B.; Siddiqui, M.S. Flood Prediction using Hydrologic and ML-based Modeling: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science & Applications 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallegatte, S.; Ranger, N.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bachu, M.; Priya, S.; Dhore, K.; Rafique, F.; Mathur, P.; Naville, N.; Henriet, F.; et al. Flood Risks, Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation Benefits in Mumbai. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koetse, M.J.; Rietveld, P. The impact of climate change and weather on transport: An overview of empirical findings. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2009, 14, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Coll, M.; Ballester-Merelo, F.; Martinez-Peiró, M.; De la Hoz-Franco, E. Real-time early warning system design for pluvial flash floods—A review. Sensors 2018, 18, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouramdane, A.-A. Enhancing disaster management in smart cities through MCDM-AHP analysis amid 21st century challenges. Information System and Smart City 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceenepalli, P.; Chandrasekhar, C. IoT-Enabled Flood Wall: Advancing Real-Time Flash Flood Monitoring and Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Self Sustainable Artificial Intelligence Systems (ICSSAS); 2023; pp. 1369–1376. [Google Scholar]

- Taubenböck, H.; Esch, T.; Felbier, A.; Wiesner, M.; Roth, A.; Dech, S. Monitoring urbanization in mega cities from space. Remote sensing of Environment 2012, 117, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.H.; Sato, M.; Habbiba, U.; Yousuf, T.B. Assessment of urban disaster resilience in Dhaka North City Corporation (DNCC), Bangladesh. Procedia engineering 2018, 212, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, A.; Majed, N. The effects of unplanned land use and heavy seasonal rainfall on the storm-water drainage in Dhaka metropolitan city of Bangladesh. Urban Water Journal 2023, 20, 707–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S. Households' flood vulnerability assessment in context of climate change. University of Twente, 2011.

- Tawhid, K.G. Causes and effects of water logging in Dhaka City, Bangladesh. TRITA-LWR master thesis, Department of Land and Water Resource Engineering, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm.

- Dewan, A.M.; Islam, M.M.; Kumamoto, T.; Nishigaki, M. Evaluating flood hazard for land-use planning in greater Dhaka of Bangladesh using remote sensing and GIS techniques. Water resources management 2007, 21, 1601–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, K.N.; Chisty, H.U.; Abedin, D.A.; Saha, A. Water in Cities: CAN WE END THE WAR?: Experiences from the Detailed Area Plan of Dhaka. In Handbook of Waterfront Cities and Urbanism; Routledge: 2022; pp. 222–238.

- Alam, S.; Jahan, S.; Noor, F. The surface water system, flood and water resources management of Bangladesh. Bangladesh Geosciences and Resources Potential 2022, 467–546. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, J.L. Climate change, disaster risk, and the urban poor: cities building resilience for a changing world; World Bank Publications: 2012.

- Shahid, S.; Wang, X.-J.; Harun, S.B.; Shamsudin, S.B.; Ismail, T.; Minhans, A. Climate variability and changes in the major cities of Bangladesh: observations, possible impacts and adaptation. Regional Environmental Change 2016, 16, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Rabbani, M.G. Vulnerabilities and responses to climate change for Dhaka. In Adapting Cities to Climate Change; Routledge: 2012; pp. 112–129.

- Rahman, A.A.; Alam, M.; Alam, S.S.; Uzzaman, M.R.; Rashid, M.; Rabbani, G. Risks, vulnerability and adaptation in Bangladesh. Human Development Report 2007, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, F.; Moors, E.; Khan, M.S.A.; Warner, J.; Van Scheltinga, C.T. Tipping points in adaptation to urban flooding under climate change and urban growth: The case of the Dhaka megacity. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, R.; Salehin, M. Flood risks and reduction approaches in Bangladesh. Disaster risk reduction approaches in Bangladesh 2013, 65–90. [Google Scholar]

- De Risi, R.; De Paola, F.; Turpie, J.; Kroeger, T. Life Cycle Cost and Return on Investment as complementary decision variables for urban flood risk management in developing countries. International journal of disaster risk reduction 2018, 28, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.; Spurway, K.; Zwi, A.; Huq, N.; Mamun, R.; Islam, R.; Nowrin, I.; Ether, S.; Bonnitcha, J.; Dahal, N. What is the impact of urbanisation on risk of, and vulnerability to, natural disasters? What are the effective approaches for reducing exposure of urban population to disaster risks, EPPI-Centre. Social Science Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education, University College London, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rau, J.L.; Nutalaya, P. Geomorphology and land subsidence in Bangkok, Thailand. In Applied geomorphology; Routledge: 2020; pp. 181–201.

- Tingsanchali, T.; Promping, T. Comprehensive Assessment of Flood Hazard, Vulnerability, and Flood Risk at the Household Level in a Municipality Area: A Case Study of Nan Province, Thailand. Water 2022, 14, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, R.K. Urbanization and related environmental issues of Metro Manila. Journal of Advanced College of Engineering and Management 2017, 3, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, J.; Botzen, W.; Bowman, M.; Dircke, P.; Ward, P. Climate Adaptation and Flood Risk in Coastal Cities (Earthscan Climate). Water Resources Research 54.

- Akhter, S.; Syed, I.M.; Alam, M.S.; Mallik, M.; Hassan, S.Q.; Huque, S.M. Simulation of High Impact Monsoon Rainfall and its Thermodynamic Features over Bangladesh Using WRF Model.

- Mishra, R. Dam Breach Parameters and its Effects on Propagation of Flood Wave at the Downstream of Sarabgarh Irrigation Project. 2018.

- Timbadiya, P.; Patel, P.; Porey, P. One-dimensional hydrodynamic modelling of flooding and stage hydrographs in the lower Tapi River in India. Current science 2014, 708–716, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24099969. [Google Scholar]

- moni Boruah, M.T. Development of 1d and 2d Hydrodynamic Flood Model Using Mike Software by Dhi”. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Balmforth, D. Designing for exceedance in urban drainage: good practice; London: CIRIA: 2006.

- DHI, D.W.E. MIKE 21 & MIKE 3 Flow Model FM. 2023.

- Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Shao, W.; Yan, D.; Mei, C. Urban flood modelling in Qiqihar city based on MIKE flood. Proceedings of the International Association of Hydrological Sciences 2020, 383, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, P.; Moffat, A.; Nalluri, C.; Narayanan, R. Hydraulic structures; CRC Press: 2017.

- Liu, J.; Cai, J.; Yang, D.; Wang, X. A numerical visualization technique based on the hydraulic analogy. Journal of Visualization 2019, 22, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Huang, J.; Toorman, E.; Yang, G. Reconstruction of river topography for 3d hydrodynamic modelling using surveyed cross-sections: An improved algorithm. Water 2020, 12, 3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MIKE. MIKE 21 & MIKE 3 Flow Model FM.

- Metcalf; Eddy; Abu-Orf, M.; Bowden, G.; Burton, F.L.; Pfrang, W.; Stensel, H.D.; Tchobanoglous, G.; Tsuchihashi, R.; AECOM. Wastewater engineering: treatment and resource recovery; McGraw Hill Education: 2014.

- Sultana, T.; Magumdar, T.K. Consultancy Services for Expansion flood forecasting model (whole country) Improve inundation model in coastal and hotspot areas (depth and area of inundation); Institute of Water Modelling (IWM): Dhaka, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, G.Y.; Zou, Z.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Guo, Q.; Yan, C.; Tan, S. Experimental studies on the effects of green space and evapotranspiration on urban heat island in a subtropical megacity in China. Habitat international 2017, 68, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohinton, E.; Erik, J. Influence of urban morphology and sea breeze on hot humid microclimate: the case of Colombo, Sri Lanka. Climate Research 2006, 30, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, A.; Tanim, A.H. Estimating urban flood hazard zones using SWMM in Chittagong City. Technical Journal River Research Institute 2016, 13, 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Shuvo, S.D.; Rashid, T.; Panda, S.K.; Das, S.; Quadir, D.A. Forecasting of pre-monsoon flash flood events in the northeastern Bangladesh using coupled hydrometeorological NWP modelling system. Meteorology and Atmospheric Physics 2021, 133, 1603–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Map of the study area.

Figure 1.

Map of the study area.

Figure 2.

Monthly average rainfall in Dhaka City.

Figure 2.

Monthly average rainfall in Dhaka City.

Figure 3.

Methodology for development of Urban Flood Forecasting System (RMSE = root mean square error, WRF= Weather Forecasting and Research and ECMWF = European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts).

Figure 3.

Methodology for development of Urban Flood Forecasting System (RMSE = root mean square error, WRF= Weather Forecasting and Research and ECMWF = European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts).

Figure 4.

Spot level and road level survey for updating existing DEM data for floodplain model.

Figure 4.

Spot level and road level survey for updating existing DEM data for floodplain model.

Figure 5.

Rainfall forecast for 24 hours on 23 October 2022 by BMD.

Figure 5.

Rainfall forecast for 24 hours on 23 October 2022 by BMD.

Figure 6.

Model components: pipe network, manholes, river network, cross-section, retention ponds, catchment distribution and model boundaries.

Figure 6.

Model components: pipe network, manholes, river network, cross-section, retention ponds, catchment distribution and model boundaries.

Figure 8.

Crest level of Dhaka Integrated Flood Control Embankment.

Figure 8.

Crest level of Dhaka Integrated Flood Control Embankment.

Figure 9.

Conceptual representation of urban flood [

47].

Figure 9.

Conceptual representation of urban flood [

47].

Figure 10.

Concept of Time Area Model to compute surface runoff.

Figure 10.

Concept of Time Area Model to compute surface runoff.

Figure 11.

A) The computational grid, B) The computational grid in network, C) Structure location, D) Loss, flow in and out and E) Water flowing through the node in 1D pipe network [

48].

Figure 11.

A) The computational grid, B) The computational grid in network, C) Structure location, D) Loss, flow in and out and E) Water flowing through the node in 1D pipe network [

48].

Figure 13.

Sub-catchment and pipe network distribution and calibration station in the model.

Figure 13.

Sub-catchment and pipe network distribution and calibration station in the model.

Figure 14.

Hydrological method used in different sub-catchments in the model.

Figure 14.

Hydrological method used in different sub-catchments in the model.

Figure 15.

Most sensitive parameter list and their influence on the runoff and shape of hydrograph. (RF = Reduction Factor [0], TC = Time of Concentration [minute], Umax = Maximum water content in surface storage [millimeter], Lmax = Maximum water content in root zone storage [millimeter], CQOF = Overland flow runoff coefficient [0], CKIF = Time constant for routing interflow [hour], CK1,2 = Time constants for routing overland flow [hour], CKBF = Time constant for routing baseflow [hour], GWLBF0 = Maximum GW-depth causing baseflow [meter] and TOF = Root zone threshold value for overland flow[()]). *[0] is dimensionless parameter.

Figure 15.

Most sensitive parameter list and their influence on the runoff and shape of hydrograph. (RF = Reduction Factor [0], TC = Time of Concentration [minute], Umax = Maximum water content in surface storage [millimeter], Lmax = Maximum water content in root zone storage [millimeter], CQOF = Overland flow runoff coefficient [0], CKIF = Time constant for routing interflow [hour], CK1,2 = Time constants for routing overland flow [hour], CKBF = Time constant for routing baseflow [hour], GWLBF0 = Maximum GW-depth causing baseflow [meter] and TOF = Root zone threshold value for overland flow[()]). *[0] is dimensionless parameter.

Figure 16.

MIKE+ urban flood model calibration at different points within model domain are shown in

Figure 13. The blue line represents the observed water level, and the black represents the model simulation water level.

Figure 16.

MIKE+ urban flood model calibration at different points within model domain are shown in

Figure 13. The blue line represents the observed water level, and the black represents the model simulation water level.

Figure 17.

MIKE+ urban flood model validation at different points within model domain are shown in Error! Reference source not found.. The blue line represents the observed water level, and the black represents the model simulation water level.

Figure 17.

MIKE+ urban flood model validation at different points within model domain are shown in Error! Reference source not found.. The blue line represents the observed water level, and the black represents the model simulation water level.

Figure 18.

Major flood event from 2019 to 2022.

Figure 18.

Major flood event from 2019 to 2022.

Figure 19.

Flood inundation map on 12 July 2024, forecast made on 11 Julyt July 2024.

Figure 19.