1. Introduction

Within a predominantly English-speaking healthcare system, language barriers have emerged as a critical element of health care disparities in the United States. According to the US Census Bureau, over 67 million people living in the United States speak a language other than English at home [

1] and more than 25 million are described as having limited English proficiency (LEP) [

2]. Hispanic people account for nearly two-thirds (62%) of the LEP population, emphasizing their significant presence within this demographic [

2]. As such, the growing impact of language barriers are disproportionately pronounced in minority populations, exacerbating health disparities that already exist [

3].

Patients themselves identify language limitations as a substantial barrier to accessing essential healthcare services [

3]. Studies across various specialties substantiate this sentiment, consistently showing that the presence of a language barrier between the patient and their medical provider contributes to worse quality of care and outcomes [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Breast cancer patients are particularly vulnerable, with evidence demonstrating that language barriers adversely impact all aspects of breast cancer care, from preventative services to establishing care, shared decision-making, treatment, and life-long follow-up.

LEP patients are less likely to access the preventative care crucial for early detection and treatment of breast cancer. Recent data showed that LEP patients, Spanish-speaking (SS) women in particular, have lower rates of screening mammograms [

10] and are more likely to present with later stage disease [

11]. Language barriers have also been associated with reduced follow-up adherence after mammogram screenings [

12].

Following diagnosis, LEP patients have difficulties with establishing and navigating treatments. Chen et al. found that Mandarin- and Spanish-speaking callers are provided with fewer follow-up steps to initiate cancer care compared to English-speaking callers [

13]. Physicians admit to difficulty in discussing treatment options and prognosis with breast cancer patients with LEP, resulting in less patient-centered treatment discussion [

14]. Additionally, while it is known that implementation of multidisciplinary programs decrease time to treatment and improve adjuvant-therapy compliance in underserved minority communities [

15], it was found that patients who lived in neighborhoods with high Hispanic composition were less likely to receive multidisciplinary cancer consultations [

16].

Barriers to post-therapeutic and restorative procedures also arise due to communication challenges with LEP patients. Studies investigating lower rates of breast reconstruction in minorities have found that Hispanic and Spanish-speaking populations, especially those with low acculturation, report not undergoing reconstruction because they did not receive enough information [

17,

18], and were significantly less likely to have seen a plastic surgeon prior to their initial surgery [

18]. Alternatively, Morrow et al. found that Latina patients were less likely to have reconstruction due to concerns about future cancer detection, complications with the procedure, ability to take time off of work, and difficulty with insurance coverage [

19]. Overall, LEP breast cancer patients experience lower self-efficacy scores, indicating difficulties seeking information, understanding and participating in care, and maintaining a positive attitude throughout their breast cancer journey [

20].

Addressing language barriers is crucial for achieving equitable and quality healthcare. Research to mitigate English-Spanish language barriers has explored patient-physician language concordance, professional medical interpreters, Community Health Workers (Promotoras), and printed educational interventions. Studies on patient-physician language concordance show improvements in patient satisfaction and outcomes compared to translator use [

21,

22], promoting partnership between patients and physicians [

23]. Though not as optimal, research shows that employing professional interpreters, specifically in-person, also yields significant positive outcomes across various aspects of communication, including reduced errors, enhanced comprehension, increased utilization of services, improved clinical outcomes, and greater patient satisfaction [

24]. The use of Promotoras for education, along with translated materials, significantly increases patient recollection and recognition of mammogram results [

25]. Educational interventions when combined with Promotora intervention, improve knowledge, genetic literacy, and self-efficacy for Latinas at high risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer [

26]. While these interventions are proven to be successful, concerns arise about the escalating costs, increased visit times, and disruption to established healthcare workflows [

8].

Medical interpreters are routinely used in breast cancer care, including office appointments, pre-surgery consultations, and subsequent follow-up visits. Yet, given the extensive time demands and involvement of various clinic staff members in activities like collecting patient medical history, engaging in significant one-on-one interactions, and conducting lengthy discussions inherent to breast cancer care, the use of interpreters becomes notably expensive and time-consuming. Consequently, this negatively impacts patient encounters, resulting in extended wait times and expensive visits for LEP patients. Resource-limited hospitals in particular are the most affected due to inadequate funding.

As a safety-net hospital, Valleywise Health Medical Center (VWHMC) is a resource-limited hospital that serves low-income and uninsured populations within the greater Phoenix metropolitan area. Among those, 70% of the patients diagnosed with breast cancer are Hispanic and over 50% are uninsured with low income. Recognizing the unique needs of LEP/Spanish-speaking patients within our community, we have implemented tailored strategies to improve their care while reducing visit times and financial expenses. These include introducing a bilingual questionnaire in English and Spanish that patients complete independently before their provider visit to ensure a thorough medical history is obtained. Additionally, during consultations, patients are presented with bilingual visual aids that detail their surgical options, facilitating comprehensive understanding of each procedure.

The aim of this study was to assess the overall benefit of these implemented interventions and to quantify the cost-effectiveness with regard to translation costs, clinic flow, and surgery readiness in a resource limited hospital and underserved Hispanic population.

2. Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted as part of a randomized controlled trial aimed at assessing the effectiveness of two quality improvement interventions (questionnaire and informational handout), and their impact on optimizing patient visits and cost reduction for Spanish-speaking patients evaluated at the VWHMC’s Breast Clinic.

2.1. Questionnaire:

The patient questionnaire is a physical handout that was designed to gather comprehensive medical history information for new patients. It included demographic data, past medical history, breast symptoms, medications, family history, and social history. The questionnaire was available in Spanish and English and comprised structured sections to ensure systematic data collection.

The study’s sample population consisted of Spanish- and English-speaking women aged 30 to 65 years old who presented to the clinic for their initial visit from May 2023 to July 2023. Patients with both benign and malignant diagnoses were included. Patients were randomized into two groups: the experimental group, which utilized the questionnaire, or the control group, which did not use the questionnaire. For patients belonging to the experimental group, questionnaires were provided upon check-in and patients were instructed to complete the questionnaire while waiting for the appointment. Completion of the questionnaire implied consent.

Patients in the experimental group were expected to complete the questionnaire prior to the start of their visit. During the visit, the provider reviewed the questionnaire with the patient in person, addressing any unanswered questions or areas requiring clarification. Conversely, for patients in the control group, medical history was obtained during the visit in a conventional manner, and the provider followed the same structure and order of questions addressed in the questionnaire. For Spanish-speaking patients, medical interpreters were present throughout the entire encounter, regardless of which group they were in.

Each encounter was timed from start to finish, and encounter times between experimental and control group visits were compared. Encounter times were further delineated for SS patients with and without questionnaire use. A cost analysis was also conducted to identify interpreter costs. Cost per minute was used to calculate interpreter cost for the total encounter and was used to compare encounter expenses for Spanish-speaking patients with and without the questionnaire.

2.2. Educational Handout:

To facilitate in-clinic counseling and discussion regarding breast cancer surgical and conservative treatment options, we collaborated with our translator colleagues to develop a bilingual educational handout (as seen in

Appendix A). The handout featured simplified illustrations that depicted the various cosmetic appearances of treatment options such as lumpectomy and mastectomy, with and without reconstructive options.

English and Spanish speaking women with a breast cancer diagnosis who presented to the clinic for their initial visit from May 2023 to July 2023 were included in this study. Patients were randomly assigned to either the experimental group, in which the educational handout was used, or to a standard encounter, in which counseling was conducted through standard verbal communication. A five-question survey was administered to both groups at their postoperative visit to identify patient understanding and overall satisfaction with their operative treatment. The survey can be found in

Appendix B and contains Likert scale-style answer choices.

During data analysis, the survey results were distilled into two groups: one included all responses indicating either disappointment or mild agreement with the discussion or overall outcomes, while the second study consisted of the highest Likert scores, demonstrating full agreement with the discussion and satisfaction with the procedure and post-operative recovery.

A retrospective chart review was performed for patients who completed the survey to further assess their understanding objectively. The number of additional phone appointments documented for each patient between the initial clinic visit and their surgery was recorded for both groups: those who received the handout and those who did not. Descriptive statistics were utilized to analyze the relationship between the two groups and the number of additional conversations needed for patients to feel comfortable proceeding with their surgery.

3. Results

A total of 41 female patients were included in the study, with an age range of 30-64 years. Among them, 29 patients (70.7%) had a cancer diagnosis, while 10 patients (24.4%) had a benign diagnosis. Additionally, 27 patients (65.8%) were Spanish-speaking, and 15 patients were uninsured. Demographic information for our questionnaire and handout groups is summarized in

Table 1 and

Table 2, respectively.

3.1. Questionnaire:

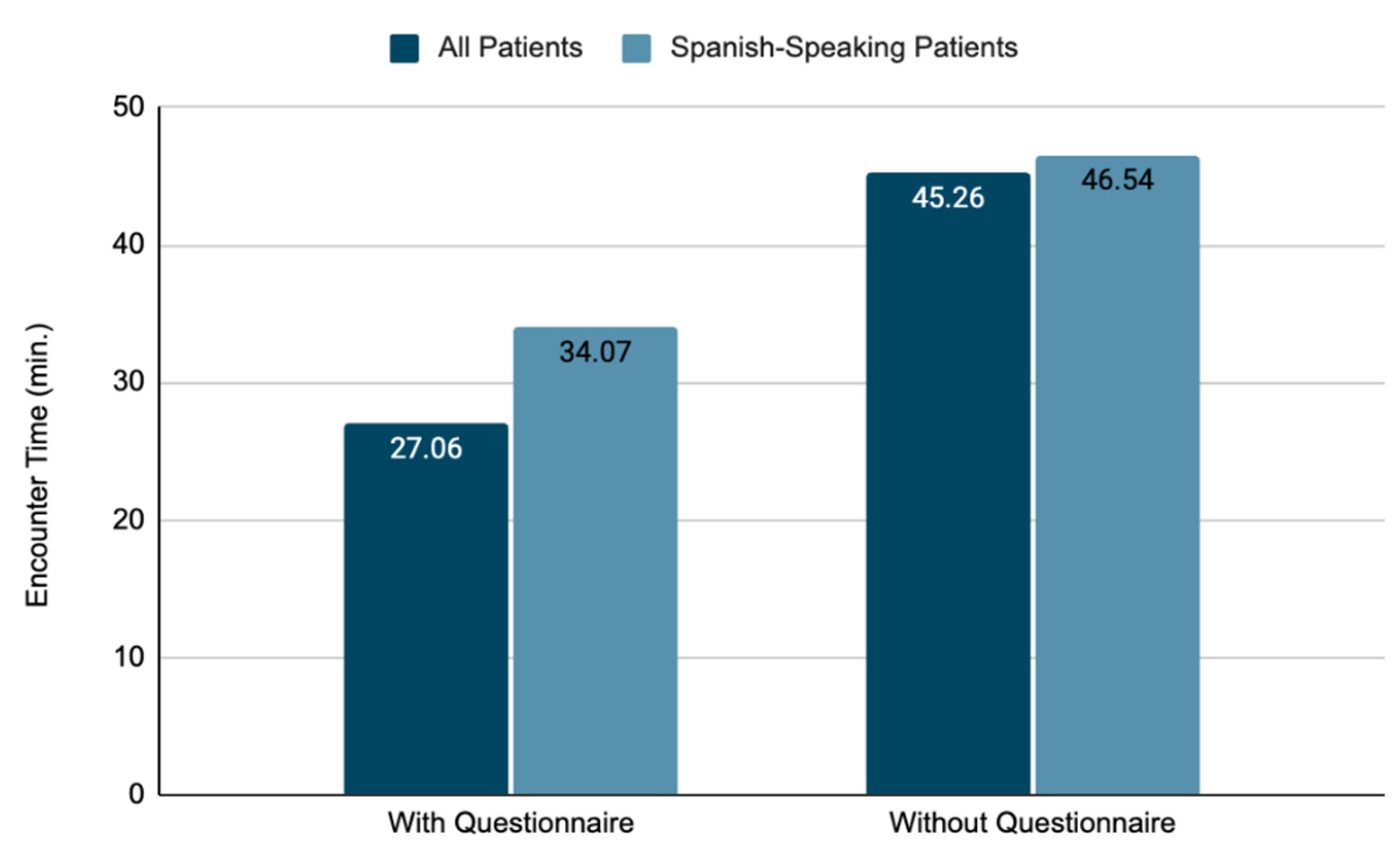

A total of 24 patients participated in the questionnaire study. Of these, 14 completed the questionnaire, while 10 did not. Overall, when the questionnaire was provided, the average total encounter time was 27.06 minutes, compared to 45.26 minutes for those who completed the visit in a standard manner (

Figure 1). Among the SS patients who completed the questionnaire, the average total encounter time was 34.07 minutes, contrasting with 46.54 minutes for those counseled without the questionnaire (

Figure 1).

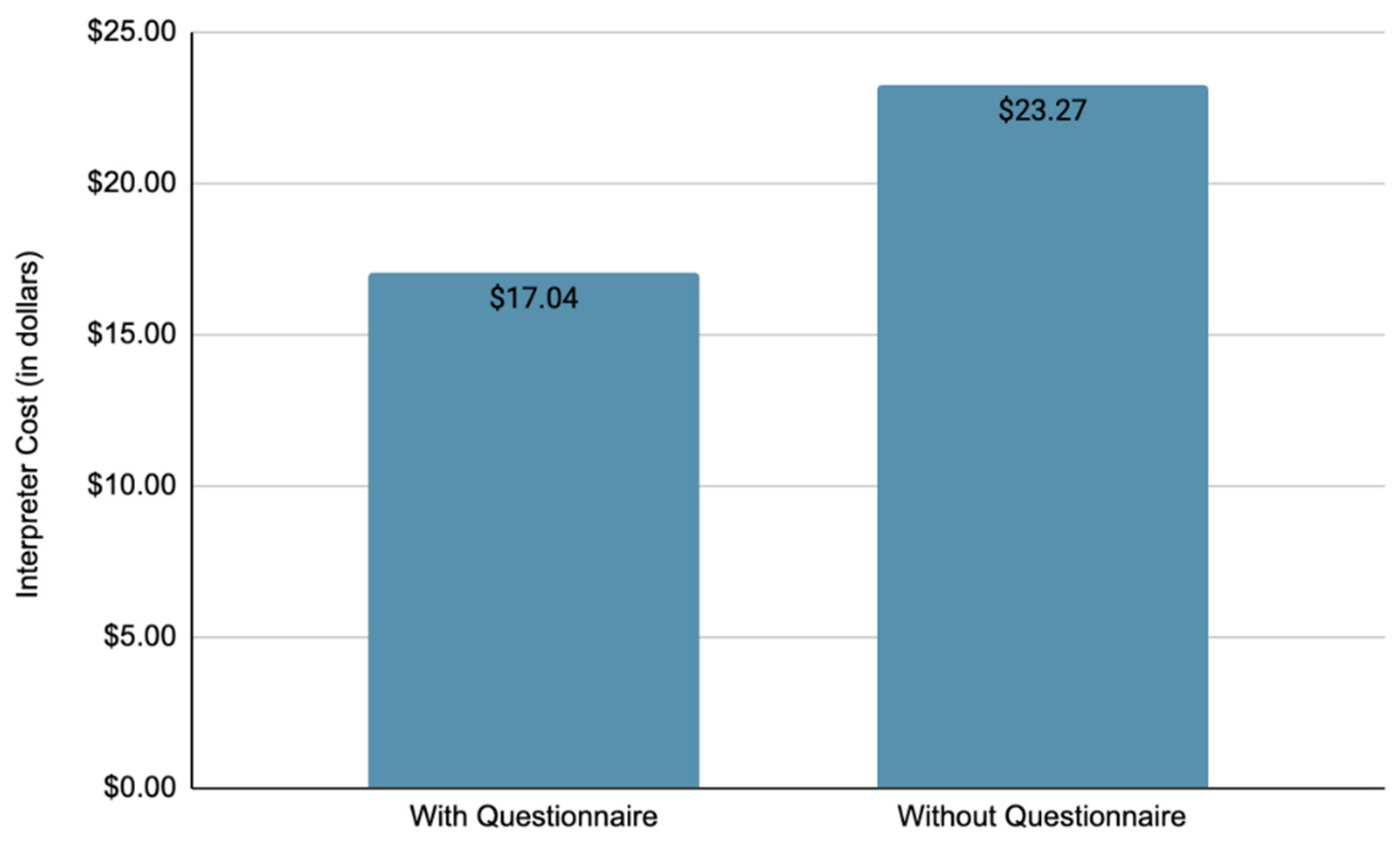

Medical interpreters were utilized for patient encounters with all Spanish-speaking patients. The average cost of an interpreter for a patient-encounter that utilized a questionnaire was

$17.04, in contrast to

$23.27 when a questionnaire was not used (

Figure 2).

3.2. Educational Handout

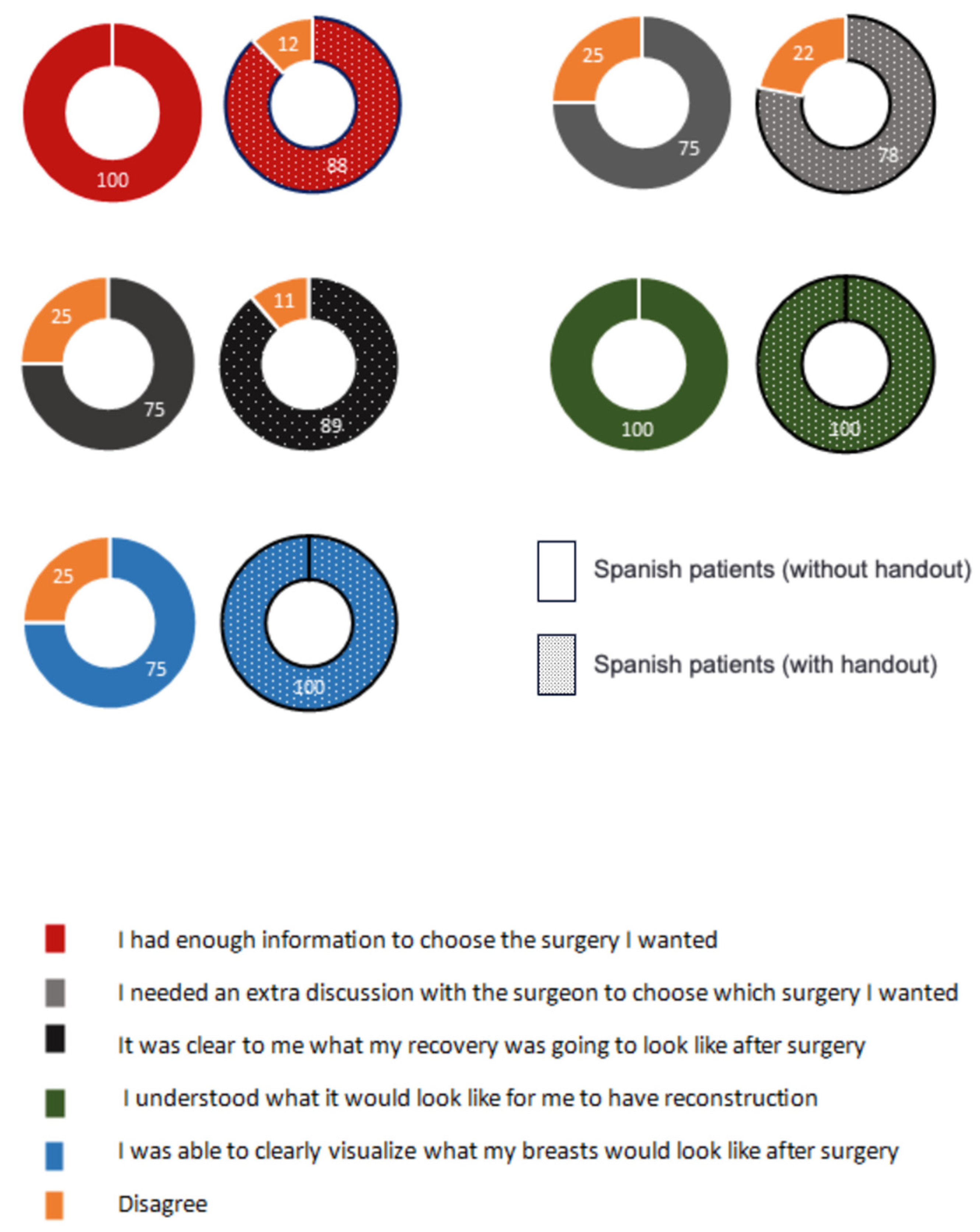

A total of 17 patients diagnosed with breast cancer were enrolled in the educational handout study. Among those, 13 patients received the educational handout during their initial encounters (9 of them were Spanish-speaking). All patients were then surveyed during their first postoperative visits. All patients who received the educational handout expressed more satisfaction and understanding of the proposed treatment plans compared to those who did not receive the handout at their initial encounter.

Figure 3 illustrates patient answers regarding their comprehension and satisfaction with the treatment options explained during their clinic evaluations, comparing SS patients who were counseled with the use of an educational handout and those who received counseling without it. The solid pie charts represent the group that did not use an educational handout, while the shaded pie charts correspond to the group that utilized the handout. Spanish patients without handout, n=4. Spanish patients with handout, n=9. The percentage of responses that were in agreement with the survey statements are presented.

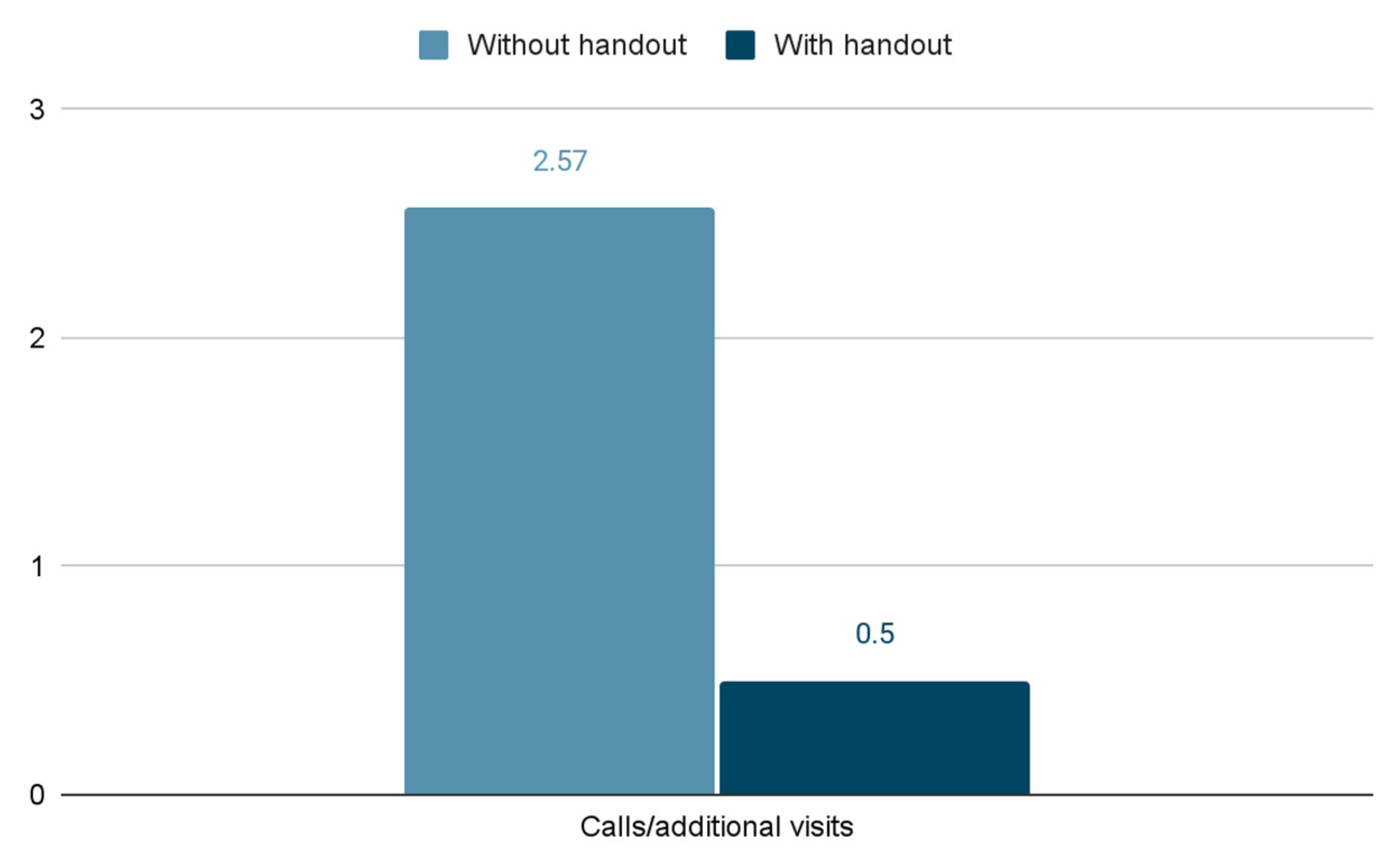

In addition, patients who received the educational handout were less likely to make additional calls to the clinic or to seek further discussions with their provider prior to their scheduled surgery. On average, patients who did not receive an educational handout during their initial consultation required 2.57 additional calls or visits before their surgery. In contrast, patients who were counseled on the various treatment plans with the use of a handout needed only 0.5 additional calls or visits to the clinic (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

Language barriers present significant challenges in healthcare delivery, particularly for patients, who frequently face disparities regarding access to and quality of care. In the United States, over 25 million people have LEP, with Hispanic individuals comprising a substantial portion of this demographic. These barriers contribute to disparities in healthcare access, quality of care, and patient outcomes, as evidenced by lower rates of preventative screenings, delays in establishing care, and challenges in treatment decision making for LEP breast cancer patients.

Our study aimed to assess the impact of implemented bilingual questionnaires and educational handouts to facilitate communication and overall understanding during patient encounters. The bilingual questionnaire aimed to streamline data collection, ensuring comprehensive medical histories were accurately obtained before the start of the patient visit. This approach not only optimized clinic flow but also allowed providers to address specific patient concerns more efficiently. The study showed that both Spanish and English-speaking patients benefit from the implemented questionnaire, suggesting how addressing low literacy should have an equal role than language barrier while lowering healthcare disparities. In a similar manner, the educational handout further enhanced patient understanding of surgical treatment options and postoperative care through clear visual aids that were optimized for bilingual populations.

The findings demonstrate that implementing these interventions led to notable improvements in clinic efficiency and patient satisfaction for LEP patients. Patients who completed the questionnaire before the visit experienced significantly shorter encounter times compared to those who did not, highlighting the effectiveness of pre-visit data collection in streamlining clinic workflows particularly for multilingual populations. Additionally, cost-effectiveness and sustainability were considered, and the study demonstrated that the average cost of interpreter services per patient encounter was lower when the questionnaire was used, suggesting potential cost savings despite initial implementation expenses. This is particularly important in resource-limited settings such as community hospitals where maximizing operational efficiency and minimizing unnecessary expenditures are essential for sustaining high-quality care for underserved populations. Moreover, the use of the visual educational handout contributed to enhanced patient comprehension and satisfaction regarding treatment options. Spanish-speaking patients who received the handout reported higher levels of understanding and were less likely to require additional clinic visits or phone consultations after their initial consultation, indicating improved patient-centered decision-making and reduced anxiety about their care.

Despite the positive outcomes observed, this study has limitations. The sample size was relatively small, limiting generalizability to broader patient populations. Future research should aim to replicate these findings in larger cohorts and across diverse healthcare settings to validate the effectiveness of bilingual interventions in improving health outcomes for LEP patients.

Addressing language barriers through targeted interventions such as bilingual questionnaires and educational handouts is essential for promoting equitable healthcare access and enhancing patient outcomes among LEP populations. The findings of this study demonstrate the potential of these interventions to improve clinic efficiency, patient satisfaction, and cost-effectiveness in delivering breast cancer care. By continuing to innovate and refine these approaches, healthcare providers can better meet the needs of diverse patient populations and reduce disparities in healthcare delivery.

5. Conclusions

Language barriers impact health disparities and quality of care among LEP patients. This study demonstrated how the simple implementation of a translated questionnaire can reduce interpretation cost, encounter time, and improve clinic flow. Furthermore, utilizing a bilingual surgical educational handout enhances patient understanding, surgery readiness and reduces unnecessary additional visits.

Authors Contribution

Conceptualization, Danielle Tanner, Charden Wood and Daniela Cocco; Data curation, Maya Block, Brianna Werner, Charden Wood and Tess Montminy; Investigation, Maya Block, Agnes Premkumar and Brianna Werner; Methodology, Agnes Premkumar; Resources, Danielle Tanner and Tess Montminy; Supervision, Daniela Cocco; Validation, Daniela Cocco; Writing – original draft, Maya Block and Agnes Premkumar; Writing – review & editing, Brianna Werner and Danielle Tanner.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Surgical Handout: bilingual illustration of surgical options for breast cancer treatment.

Appendix B

Post-operative Survey: bilingual five-question survey regarding overall satisfaction with the treatment (Likert scale-style answer choices).

References

- Sandy Dietrich; Erik Hernandez Nearly 68 Million People Spoke a Language Other Than English at Home in 2019. U. S. Census Bur. 2022.

- Sweta Haldar; Drishti Pillai; Samantha Artiga Overview of Health Coverage and Care for Individuals with Limited English Proficiency (LEP). KFF Indep. Source Health Policy Res. Poll. News 2023.

- Reddy, S.; Saxon, M.; Patel, N.; Speer, M.; Ziegler, T.; Patel, N.; Ziegler, M.; Esquivel, S.; Mata, A.D.; Devineni, A.; et al. Discordance in Perceptions of Barriers to Breast Cancer Treatment Between Hispanic Women and Their Providers. J. Patient-Centered Res. Rev. 2020, 7, 337–342.

- Timmins, C.L. The Impact of Language Barriers on the Health Care of Latinos in the United States: A Review of the Literature and Guidelines for Practice. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2002, 47, 80–96. [CrossRef]

- Dagher, O.; Passos-Castilho, A.M.; Sareen, V.; Labbé, A.-C.; Barkati, S.; Luong, M.-L.; Rousseau, C.; Benedetti, A.; Azoulay, L.; Greenaway, C. Impact of Language Barriers on Outcomes and Experience of COVID-19 Patients Hospitalized in Quebec, Canada, During the First Wave of the Pandemic. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2024, 26, 3–14. [CrossRef]

- Joo, H.; Fernández, A.; Wick, E.C.; Moreno Lepe, G.; Manuel, S.P. Association of Language Barriers With Perioperative and Surgical Outcomes: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2322743. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M.; Maina, R.G.; Amoyaw, J.; Li, Y.; Kamrul, R.; Michaels, C.R.; Maroof, R. Impacts of English Language Proficiency on Healthcare Access, Use, and Outcomes among Immigrants: A Qualitative Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 741. [CrossRef]

- Al Shamsi, H.; Almutairi, A.G.; Al Mashrafi, S.; Al Kalbani, T. Implications of Language Barriers for Healthcare: A Systematic Review. Oman Med. J. 2020, 35, e122. [CrossRef]

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Crotty, K. Low Health Literacy and Health Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97–107. [CrossRef]

- Cataneo, J.L.; Meidl, H.; Ore, A.S.; Raicu, A.; Schwarzova, K.; Cruz, C.G. The Impact of Limited Language Proficiency in Screening for Breast Cancer. Clin. Breast Cancer 2023, 23, 181–188. [CrossRef]

- Balazy, K.E.; Benitez, C.M.; Gutkin, P.M.; Jacobson, C.E.; von Eyben, R.; Horst, K.C. Association between Primary Language, a Lack of Mammographic Screening, and Later Stage Breast Cancer Presentation. Cancer 2019, 125, 2057–2065. [CrossRef]

- Karliner, L.S.; Ma, L.; Hofmann, M.; Kerlikowske, K. Language Barriers, Location of Care, and Delays in Follow-up of Abnormal Mammograms. Med. Care 2012, 50, 171–178. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.W.; Banerjee, M.; He, X.; Miranda, L.; Watanabe, M.; Veenstra, C.M.; Haymart, M.R. Hidden Disparities: How Language Influences Patients’ Access to Cancer Care. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. JNCCN 2023, 21, 951-959.e1. [CrossRef]

- Karliner, L.S.; Hwang, E.S.; Nickleach, D.; Kaplan, C.P. Language Barriers and Patient-Centered Breast Cancer Care. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 84, 223–228. [CrossRef]

- Castaldi, M.; Safadjou, S.; Elrafei, T.; McNelis, J. A Multidisciplinary Patient Navigation Program Improves Compliance With Adjuvant Breast Cancer Therapy in a Public Hospital. Am. J. Med. Qual. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Qual. 2017, 32, 406–413. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.I.; Doose, M.; Zeruto, C.; Chollette, V.; Gasca, N.; Verhoeven, D.; Weaver, S.J. Multilevel Factors Associated with Inequities in Multidisciplinary Cancer Consultation. Health Serv. Res. 2022, 57 Suppl 2, 222–234. [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, S.; Colvill, K.; Lopez, M.; Phillips, L.G. Implications of Demographics and Socioeconomic Factors in Breast Cancer Reconstruction. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2019, 83, 388–391. [CrossRef]

- Alderman, A.K.; Hawley, S.T.; Janz, N.K.; Mujahid, M.S.; Morrow, M.; Hamilton, A.S.; Graff, J.J.; Katz, S.J. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Use of Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruction: Results from a Population- Based Study. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 5325–5330. [CrossRef]

- Morrow, M.; Li, Y.; Alderman, A.K.; Jagsi, R.; Hamilton, A.S.; Graff, J.J.; Hawley, S.T.; Katz, S.J. Access to Breast Reconstruction after Mastectomy and Patient Perspectives on Reconstruction Decision Making. JAMA Surg. 2014, 149, 1015–1021. [CrossRef]

- Gunn, C.M.; Paasche-Orlow, M.K.; Bak, S.; Wang, N.; Pamphile, J.; Nelson, K.; Morton, S.; Battaglia, T.A. Health Literacy, Language, and Cancer-Related Needs in the First 6 Months After a Breast Cancer Diagnosis. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020, 16, e741–e750. [CrossRef]

- Seible, D.M.; Kundu, S.; Azuara, A.; Cherry, D.R.; Arias, S.; Nalawade, V.V.; Cruz, J.; Arreola, R.; Martinez, M.E.; Nodora, J.N.; et al. The Influence of Patient-Provider Language Concordance in Cancer Care: Results of the Hispanic Outcomes by Language Approach (HOLA) Randomized Trial. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2021, 111, 856–864. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, L.; Izquierdo, K.; Canfield, D.; Matsoukas, K.; Gany, F. A Systematic Review of the Impact of Patient-Physician Non-English Language Concordance on Quality of Care and Outcomes. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 1591–1606. [CrossRef]

- Bregio, C.; Finik, J.; Baird, M.; Ortega, P.; Roter, D.; Karliner, L.; Diamond, L.C. Exploring the Impact of Language Concordance on Cancer Communication. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2022, 18, e1885–e1898. [CrossRef]

- Karliner, L.S.; Jacobs, E.A.; Chen, A.H.; Mutha, S. Do Professional Interpreters Improve Clinical Care for Patients with Limited English Proficiency? A Systematic Review of the Literature. Health Serv. Res. 2007, 42, 727–754. [CrossRef]

- Ridgeway, J.L.; Jenkins, S.M.; Borah, B.J.; Suman, V.J.; Patel, B.K.; Ghosh, K.; Rhodes, D.J.; Norman, A.; Ramos, E.P.; Jewett, M.; et al. Evaluating Educational Interventions to Increase Breast Density Awareness among Latinas: A Randomized Trial in a Federally Qualified Health Center. Cancer 2022, 128, 1038–1047. [CrossRef]

- Vadaparampil, S.T.; Moreno Botero, L.; Fuzzell, L.; Garcia, J.; Jandorf, L.; Hurtado-de-Mendoza, A.; Campos-Galvan, C.; Peshkin, B.N.; Schwartz, M.D.; Lopez, K.; et al. Development and Pilot Testing of a Training for Bilingual Community Education Professionals about Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer among Latinas: ÁRBOLES Familiares. Transl. Behav. Med. 2022, 12, ibab093. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).