Submitted:

03 September 2024

Posted:

05 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Brief Introduction

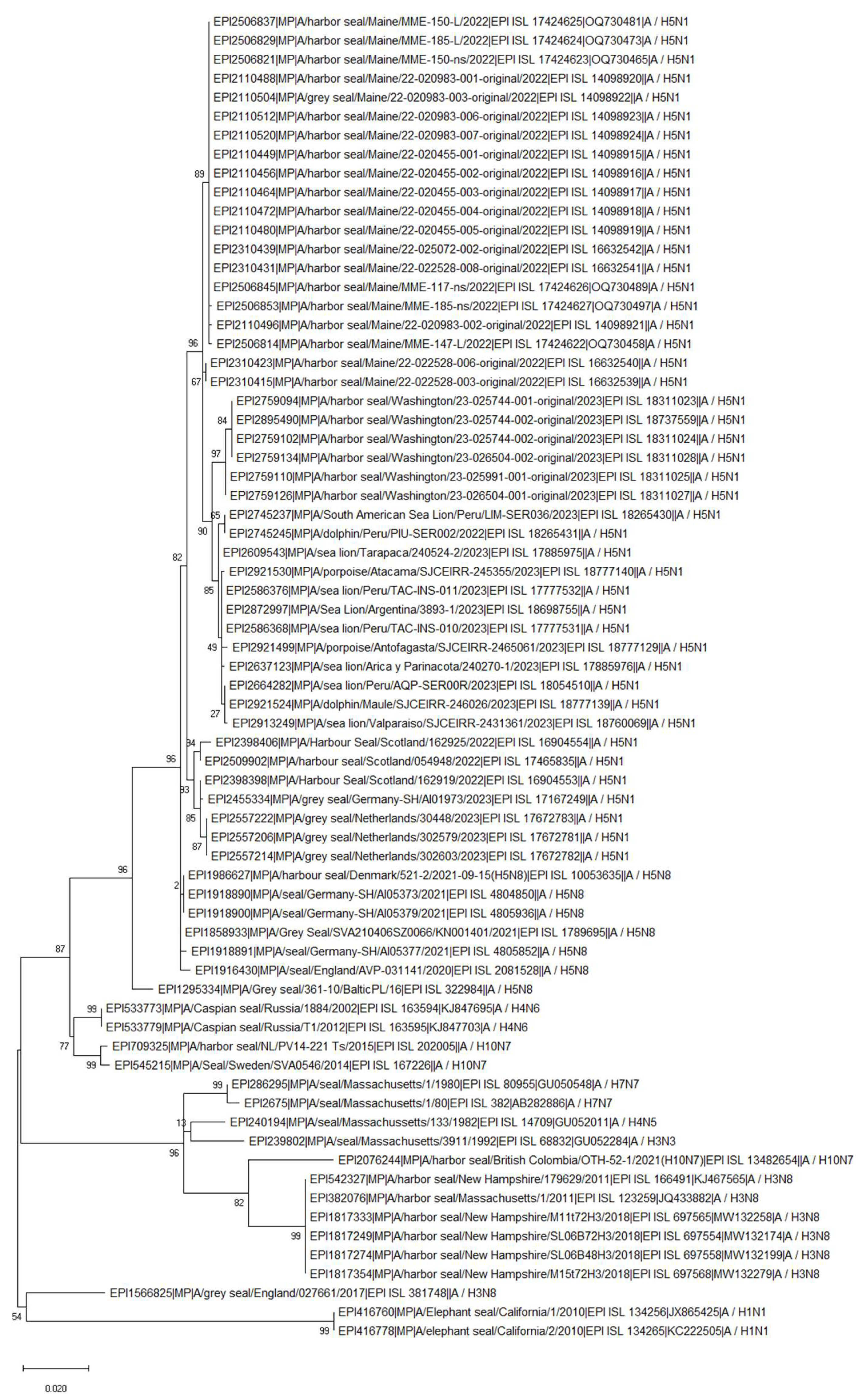

The first Reported Cases of Avian Influenza Viruses (AIV) in Seals Were of Low Pathogenic Subtype (LPAIV)

LPAIV: H7N7 (1979), H4N5 (1982), H3N3 (1992), H4N6 (1992, 2002, 2012)

LPAIV: H3N8 (2011, 2017-2019)

LPAIV: H10N7 (2014-2015 and 2021)

Pandemic H1N1 (2010, 2019)

The first reported Cases of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Viruses (HPAIV) in Seals

HPAIV: H5N8 Clade 2.3.4.4b (2016/2017, 2021, 2022)

HPAIV: H5N1 Clade 2.3.4.4b (2022-Current)

Summary

Supplementary Materials

References

- EFSA. Avian influenza overview April – June 2023. EFSA journal . [CrossRef]

- Briggs K, Kapczynski DR. Comparative analysis of PB2 residue 627E/K/V in H5 subtypes of avian influenza viruses isolated from birds and mammals. Front Vet Sci 2023, 10, 1250952. [CrossRef]

- National Oceanic and AtmosNOAA 2024. Available at https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/.

- Haug, T., M.O. Hammill and D. Ólafsdóttir (Eds.). 2007. Grey seals in the North Atlantic and the Baltic. NAMMCO Scientific Publications. 6:7–12.

- Stewart BS, Yochem PK, Le Boeuf BJ, Huber HR, DeLong RL, Jameson RJ, et al. Population recovery and status of the northern elephant seal, Mirounga angustirostris. In: Le Boeuf BJ, Laws RM, editors. Elephant Seals: Population Ecology, Behavior, and Physiology. University of California Press; 1994. p. 29–48.

- Nature Scotland 2024. Available at hps://www.nature.scot/.

- Wood SA, Murray KT, Josephson E., Gilbert J. Rates of increase in gray seal (Halichoerus grypus atlantica) pupping at recolonized sites in the United States, 1988–2019. Journal of Mammalogy, Volume 101, Issue 1, 21 February 2020, Pages 121–128 . [CrossRef]

- Townsend, CH. The Northern Elephant Seal. New York Zoological Society. 1912. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry MS, Condit R, Hatfield B, Allen SG, Berger R, Laake J, et al. Abundance, distribution, and growth of the northern elephant seal, Mirounga angustirostris, in the United States in 2010. Aquatic Mammals. 2014; 40(1):20–31. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.E.; et al. (2014). "Finescale ecological niche modeling provides evidence that lactating grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) prefer access to fresh water in order to drink" (PDF). Marine Mammal Science. 30 (4): 1456–1472. [CrossRef]

- Boyd, I. L.; Walker, T. R.; Poncet, J. (1996). Walton, David W. H.; Vaughan, Alan P. M.; Hulbe, Christina L. (eds.). "Status of Southern Elephant seals at South Georgia". Antarctic Science. 8 (3): 237–244.

- NEWS. Available at htps://www.telegraph.co.uk/global-health/science-and-disease/bird-flu-kills-17000-elephant-seal-pups-in-argentina/. 1700.

- Lang G, Gagnon A, Geraci JR. Isolation of an influenza A virus from seals. Arch Virol. 1981;68(3-4):189-95. [CrossRef]

- Webster RG, Hinshaw VS, Bean WJ, Van Wyke KL, Geraci JR, St Aubin DJ, Petursson G. Characterization of an influenza A virus from seals. Virology. 1981 Sep;113(2):712-24. [CrossRef]

- Geraci JR, St Aubin DJ, Barker IK, Webster RG, Hinshaw VS, Bean WJ, Ruhnke HL, Prescott JH, Early G, Baker AS, Madoff S, Schooley RT. Mass mortality of harbor seals: pneumonia associated with influenza A virus. Science. 1982 Feb 26;215(4536):1129-31. [CrossRef]

- Hinshaw VS, Webster RG, Easterday BC, Bean WJ Jr. Replication of avian influenza A viruses in mammals. Infect Immun. 1981 Nov;34(2):354-61. [CrossRef]

- Murphy BR, Harper J, Sly DL, London WT, Miller NT, Webster RG. Evaluation of the A/Seal/Mass/1/80 virus in squirrel monkeys. Infect Immun. 1983 Oct; 42(1): 424–426. [CrossRef]

- Li SQ, Orlich M, Rott R. Generation of seal influenza virus variants pathogenic for chickens, because of hemagglutinin cleavage site changes. J Virol. 1990 Jul;64(7):3297-303. [CrossRef]

- Hinshaw VS, Bean WJ, Webster RG, Rehg JE, Fiorelli P, Early G, Geraci JR, St Aubin DJ. Are seals frequently infected with avian influenza viruses? J Virol. 1984 Sep;51(3):863-5. [CrossRef]

- Austin FJ, Webster RG. Evidence of ortho- and paramyxoviruses in fauna from Antarctica. J Wildl Dis. 1993 Oct;29(4):568-71. [CrossRef]

- Naeve C. W., Webster R. G. Sequence of the hemagglutinin gene from influenza virus A/Seal/Mass/1 /80. 1983Virology 129:298–308.

- Donis R. O., Bean W. J., Kawaoka Y., Webster R. G. Distinct lineages of influenza virus H4 hemagglutinin genes in different regions of the world. 1989; Virology 169:408–417. 1989.

- Callan RJ, Early G, Kida H, Hinshaw VS. The appearance of H3 influenza viruses in seals. J Gen Virol. 1995 Jan;76 ( Pt 1):199-203. [CrossRef]

- Matrosovich M, Tuzikov A, Bovin N, Gambaryan A, Klimov A, Castrucci MR, Donatelli I, Kawaoka Y. Early alterations of the receptor-binding properties of H1, H2, and H3 avian influenza virus hemagglutinins after their introduction into mammals. J Virol. 2000 Sep;74(18):8502-12. [CrossRef]

- Ramis AJ, van Riel D, van de Bildt MW, Osterhaus A, Kuiken T. Influenza A and B virus attachment to respiratory tract in marine mammals. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012 May;18(5):817-20. [CrossRef]

- Gulyaeva M, Sobolev I, Sharshov K, Kurskaya O, Alekseev A, Shestopalova L, Kovner A, Bi Y, Shi W, Shchelkanov M, Shestopalov A. Characterization of Avian-like Influenza A (H4N6) Virus Isolated from Caspian Seal in 2012. Virol Sin. 2018 Oct;33(5):449-452. [CrossRef]

- Ohishi K, Ninomiya A, Kida H, Park C-H, Maruyama T, Arai T, Katsumata E, Tobayama T, Boltunov AN, Khuraskin LS, Miyazaki N. Serological evidence of transmission of human influenza A and B viruses to Caspian seals (Phoca caspica). Microbiol Immunol 2002;46(9):639-44. [CrossRef]

- Bogomolni AL, Gast RJ, Ellis JC, Dennett M, Pugliares KR, Lentell BJ, Moore MJ. Victims or vectors: a survey of marine vertebrate zoonoses from coastal waters of the Northwest Atlantic. Dis Aquat Organ 2008. 81:13–38.

- Anthony SJ, St Leger JA, Pugliares K, Ip HS, Chan JM, Carpenter ZW, Navarrete-Macias I, Sanchez-Leon M, Saliki JT, Pedersen J, Karesh W, Daszak P, Rabadan R, Rowles T, Lipkin WI. Emergence of fatal avian influenza in New England harbor seals. mBio. 2012 Jul 31;3(4):e00166-12. [CrossRef]

- Yang H, Nguyen HT, Carney PJ, Guo Z, Chang JC, Jones J, Davis CT, Villanueva JM, Gubareva LV, Stevens J. Structural and functional analysis of surface proteins from an A(H3N8) influenza virus isolated from New England harbor seals. J Virol. 2015 Mar;89(5):2801-12. [CrossRef]

- Karlsson EA, Ip HS, Hall JS, Yoon SW, Johnson J, Beck MA, Webby RJ, Schultz-Cherry S. Respiratory transmission of an avian H3N8 influenza virus isolated from a harbour seal. Nat Commun. 2014 Sep 3;5:4791. [CrossRef]

- Hussein IT, Krammer F, Ma E, Estrin M, Viswanathan K, Stebbins NW, Quinlan DS, Sasisekharan R, Runstadler. New England harbor seal H3N8 influenza virus retains avian-like receptor specificity. J. Sci Rep. 2016 Feb 18;6:21428. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh D, Bianco C, Núñez A, Collins R, Thorpe D, Reid SM, Brookes SM, Essen S, McGinn N, Seekings J, Cooper J, Brown IH, Lewis NS. Detection of H3N8 influenza A virus with multiple mammalian-adaptive mutations in a rescued Grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) pup. Virus Evol. 2020 Mar 18;6(1):veaa016. [CrossRef]

- Bao P, Liu Y, Zhang X, Fan H, Zhao J, Mu M, Li H, Wang Y, Ge H, Li S, Yang X, Cui Q, Chen R, Gao L, Sun Z, Gao L, Qiu S, Liu X, Horby PW, Li X, Fang L, Liu W. Human infection with a reassortment avian influenza A H3N8 virus: an epidemiological investigation study. Nat Commun. 2022 Nov 10;13(1):6817. [CrossRef]

- Tan X, Yan XT, Liu Y, Wu Y,Liu JY, Mu M,Zhao J, Wang XY 1, Li JQ, Wen L, Guo P, Zhou ZG, Li XB, Bao PT. A case of human infection by H3N8 influenza virus. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022 Dec;11(1):2214-2217. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Wang M, Zhang H, Zhao C, Zhang Y, Shen J, Sun X, Xu H, Xie Y, Gao X, Cui P, Chu D, Li Y, Liu W, Peng P, Deng G, Guo J, Li X. Prevalence, evolution, replication and transmission of H3N8 avian influenza viruses isolated from migratory birds in eastern China from 2017 to 2021. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2023 Dec;12(1):2184178. [CrossRef]

- Zohari S, Neimanis A, Härkönen T, Moraeus C, Valarcher JF. Avian influenza A(H10N7) virus involvement in mass mortality of harbour seals (Phoca vitulina) in Sweden, March through October 2014. Euro Surveill. 2014 Nov 20;19(46):20967. 20 October. [CrossRef]

- Bodewes R, Bestebroer TM, van der Vries E, Verhagen JH, Herfst S, Koopmans MP, Fouchier RA, Pfankuche VM, Wohlsein P, Siebert U, Baumgärtner W, Osterhaus AD. Avian Influenza A(H10N7) virus-associated mass deaths among harbor seals. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Apr;21(4):720-2. [CrossRef]

- Krog JS, Hansen MS, Holm E, Hjulsager CK, Chriél M, Pedersen K, O. Andresen L, Abildstrøm M, Jensen TH, Larsen LE. Influenza A(H10N7) Virus in Dead Harbor Seals, Denmark. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Apr; 21(4): 684–687. [CrossRef]

- Bodewes R, Zohari S, Krog JS, Hall MD, Harder TC, Bestebroer TM, van de Bildt MWG, Spronken MI, Larsen LE, Siebert U, Wohlsein P, Puff C, Seehusen F, Baumgärtner W, Härkönen T, Smits SL, Herfst S, Osterhaus ADME, Fouchier RAM, Koopmans MP, Kuiken T. Spatiotemporal Analysis of the Genetic Diversity of Seal Influenza A(H10N7) Virus, Northwestern Europe. J Virol. 2016 Apr 14;90(9):4269-4277. [CrossRef]

- van den Brand JM, Wohlsein P, Herfst S, Bodewes R, Pfankuche VM, van de Bildt MW, Seehusen F, Puff C, Richard M, Siebert U, Lehnert K, Bestebroer T, Lexmond P, Fouchier RA, Prenger-Berninghoff E, Herbst W, Koopmans M, Osterhaus AD, Kuiken T, Baumgärtner W. Influenza A (H10N7) Virus Causes Respiratory Tract Disease in Harbor Seals and Ferrets. PLoS One. 2016 Jul 22;11(7):e0159625. [CrossRef]

- Dittrich A, Scheibner D, Salaheldin AH, Veits J, Gischke M, Mettenleiter TC, Abdelwhab EM. Impact of Mutations in the Hemagglutinin of H10N7 Viruses Isolated from Seals on Virus Replication in Avian and Human Cells. Viruses. 2018 Feb; 10(2): 83. [CrossRef]

- Herfst S, Zhang J, Richard M, McBride R, Lexmond P, Bestebroer TM, Spronken MIJ, de Meulder D, van den Brand JM, Rosu ME, Martin SR, Gamblin SJ, Xiong X, Peng W, Bodewes R, van der Vries E, Osterhaus ADME, Paulson JC, Skehel JJ, Fouchier RAM. Hemagglutinin Traits Determine Transmission of Avian A/H10N7 Influenza Virus between Mammals. Cell Host Microbe. 2020 Oct 7;28(4):602-613.e7. [CrossRef]

- Guan M, Hall JS, Zhang X, Dusek RJ, Olivier AK, Liu L, Li L, Krauss S, Danner A, Li T, Rutvisuttinunt W, Lin X, Hallgrimsson GT, Ragnarsdottir SB, Vignisson SR, TeSlaa J, Nashold SW, Jarman R, Wan X-F. Aerosol Transmission of Gull-Origin Iceland Subtype H10N7 Influenza A Virus in Ferrets. J Virol. 2019 Jul 1; 93(13): e00282-19. [CrossRef]

- Berhane Y, Joseph T, Lung O, Embury-Hyatt C, Xu W, Cottrell P, Raverty S. Isolation and Characterization of Novel Reassortant Influenza A(H10N7) Virus in a Harbor Seal, British Columbia, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022 Jul; 28(7): 1480–1484. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein T, Mena I, Anthony SJ, Medina R, Robinson PW, Greig DJ, Costa DP, Lipkin WI, Garcia-Sastre A, Boyce WM. Pandemic H1N1 influenza isolated from free-ranging Northern Elephant Seals in 2010 off the central California coast. PLoS One. 2013 ;8(5):e62259. 15 May. [CrossRef]

- Plancarte M, Kovalenko GG, Baldassano J, Ramírez AL, Carrillo S, Duignan PG, Goodfellow I, Bortz E, Dutta J, van Bakel H, Coffey LL. Human influenza A virus H1N1 in marine mammals in California, 2019. PLoS One 2023 Mar 30;18(3):e0283049. [CrossRef]

- Shin DL, Siebert U, Lakemeyer J, Grilo M, Pawliczka I, Wu NH, Valentin-Weigand P, Haas L, Herrler G. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N8) Virus in Gray Seals, Baltic Sea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019 Dec;25(12):2295-2298. [CrossRef]

- Floyd T, Banyard AC, Lean FZX, Byrne AMP, Fullick E, Whittard E, Mollett BC, Bexton S, Swinson V, Macrelli M, Lewis NS, Reid SM, Núñez A, Duff JP, Hansen R, Brown IH. Encephalitis and Death in Wild Mammals at a Rehabilitation Center after Infection with Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N8) Virus, United Kingdom. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021 Nov;27(11):2856-2863. [CrossRef]

- Postel A, King J, Kaiser FK, Kennedy J, Lombardo MS, Reineking W, de le Roi M, Harder T, Pohlmann A, Gerlach T, Rimmelzwaan G, Rohner S, Striewe LC, Gross S, Schick LA, Klink JC, Kramer K, Osterhaus ADME, Beer M, Baumgärtner W, Siebert U, Becher P. Infections with highly pathogenic avian influenza A virus (HPAIV) H5N8 in harbor seals at the German North Sea coast, 2021. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022 Dec;11(1):725-729. [CrossRef]

- Bennison A, Byrne AMP, Reid SM, Lynton-Jenkins JG, Mollett B, De Sliva D, Peers-Dent J, Finlayson K, Hall R, Blockley F, Blyth M, Falchieri M, Fowler Z, Fitzcharles EM, Brown IH, James J, Banyard AC. Detection and spread of high pathogenicity avian influenza virus H5N1 in the Antarctic Region. bioRxiv 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gamarra-Toledo V, Plaza PI, Gutiérrez R, Inga-Diaz G, Saravia-Guevara P, Pereyra-Meza O, Coronado-Flores E, Calderón-Cerrón A, Quiroz-Jiménez G, Martinez P, Huamán-Mendoza D, Nieto-Navarrete JC, Ventura S, Lambertucci SA. Mass Mortality of Sea Lions Caused by Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus Emerg Infect Dis 2023 Dec;29(12):2553-2556. [CrossRef]

- Leguia M, Garcia-Glaessner A, Muñoz-Saavedra B, Juarez D, Barrera P, Calvo-Mac C, Jara J, Silva W, Ploog K, Amaro L, Colchao-Claux P, Johnson CK, Uhart MM, Nelson MI, Lescano J. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) in marine mammals and seabirds in Peru. Nat Commun. 2023; 14: 5489. Published online 2023 Sep 7. [CrossRef]

- World Animal Health Information System (WOAH-WAHIS) report, 23. Available at https://www.woah. 20 March.

- Pardo-Roa C, Nelson MI, Ariyama N, Aguayo C, Almonacid LI, Munoz G, Navarro C, Avila C, Ulloa M, Reyes R, Luppichini EF, Mathieu C, Vergara R, González A, González CG, Araya H, Fernández J, Fasce R, Johow M, Medina RA, Neira V. Cross-species transmission and PB2 mammalian adaptations of highly pathogenic avian influenza A/H5N1 viruses in Chile. bioRxiv. Preprint. 2023 Jun 30. [CrossRef]

- Puryear W, Sawatzki K, Hill N, Foss A, Stone JJ, Doughty L, Walk D, Gilbert K, Murray M, Cox E, Patel P, Mertz Z, Ellis S, Taylor J, Fauquier D, Smith A, DiGiovanni Jr RA, van de Guchte A, Gonzalez-Reiche AS, Khalil Z, van Bakel H, Torchetti MK, Lantz K, Lenoch JB, Runstadler J. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus Outbreak in New England Seals, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023 Apr;29(4):786-791. [CrossRef]

- Puryear W, Keogh M, Hill N, Moxley J, Josephson E, Davis KR, Bandoro C, Lidgard D, Bogomolni A, Levin M, Lang S, Hammill M, Bowen D, Johnston DW, Romano T, Waring G, Runstadler J. Prevalence of influenza A virus in live-captured North Atlantic gray seals: a possible wild reservoir. Emerg Microbes Infect 2016 Aug 3;5(8):e81. [CrossRef]

- Gass Jr JD, Hunter K Kellogg HK, Hill NJ, Puryear WB, Nutter FB, Runstadler JA. Epidemiology and Ecology of Influenza A Viruses among Wildlife in the Arctic. Viruses 2022 Jul 13;14(7):1531. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).