Submitted:

02 September 2024

Posted:

04 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.3.1. Phenomenon of Interest

2.3.2. Context

2.3.3. Types of Participants

2.3.4. Types of Studies

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Quality Appraisal

2.7. Data Synthesis

3. Results

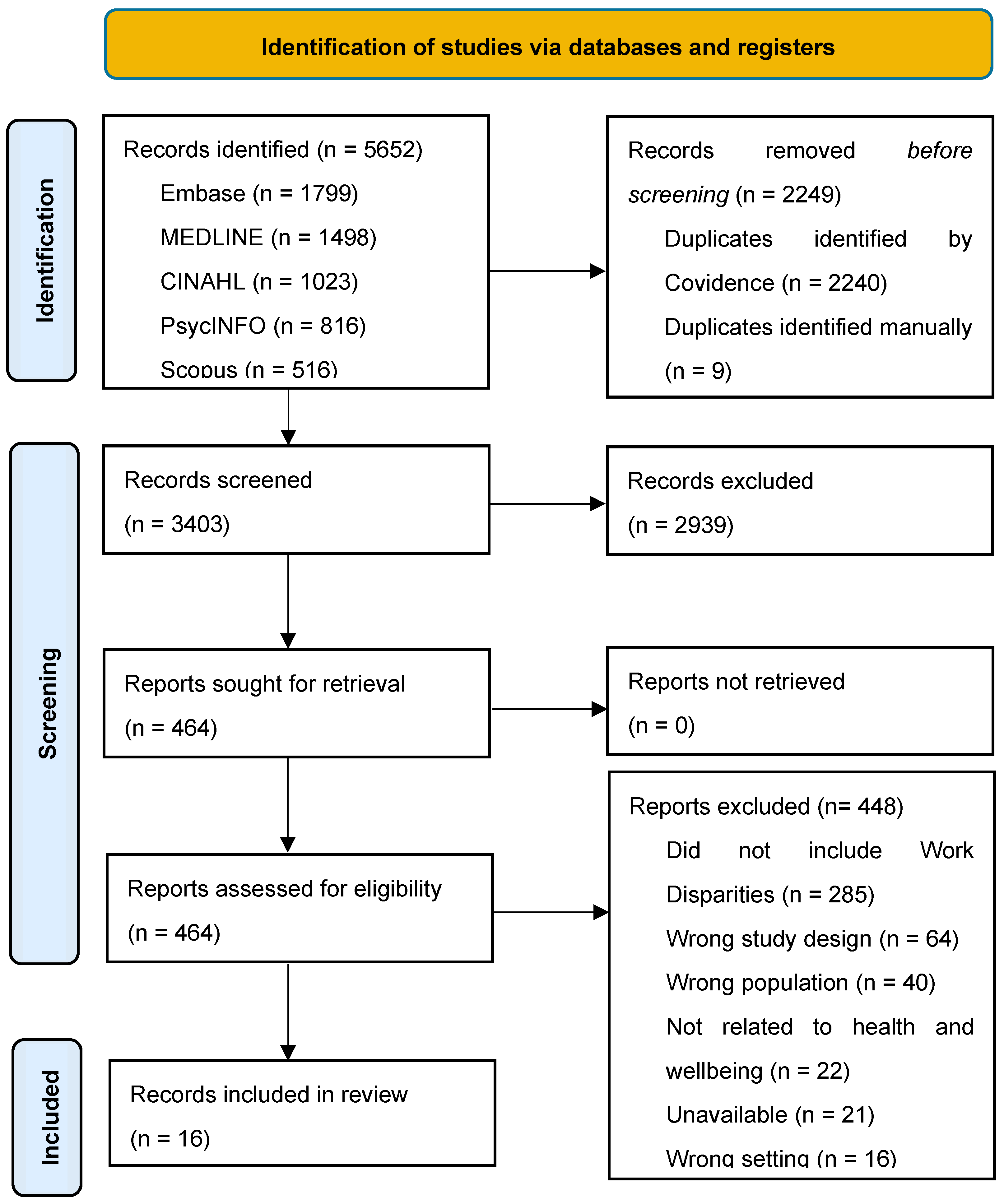

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Eligible Source Characteristics

3.3. Work Disparities

3.3. Health and Well-Being

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Work Disparity Conceptual Framework Terminology

| Term | Definition | |

| 1. Variable of work disparity | Any defined factor, construct, or characteristic of inequality, or factor of unfairness/difference. Four categories were identified based on a sample of the literature on work disparities experienced in LTC for nurses: job security, work compensation, work opportunities, and/or workplace treatment. | |

| 1a. Measure of disparity | Values that quantitatively/qualitatively measure, examine, and/or explore variables of work disparity. | |

| 1b. Categories | Examples* | |

| 1b(i). Job Security | Hiring /dismissal practices, Intent to leave, Retention, Recruitment | |

| 1b(ii). Work Compensation | Wages, Benefits, Paid-vacation days, Health insurance | |

| 1b(iii). Work Opportunities | Ability to be promoted in an organization, Development opportunities, Exposure to challenging/meaningful work, Amount of work provided | |

| 1b(iv). Workplace Treatment | Discrimination, Expectations/demands of performance (e.g., emotional labor, cognitive labor demands), Recognition of contributions, Work satisfaction | |

| 2. Comparator Group | A group of individuals (workers) composed of members of the workforce. | |

| 2a. Group identity | The identity associated with each individual comparator group (e.g., gender, race, socioeconomic status, residency status, educational status, profession, indigenous status, work setting, age, sexuality, disability, height, identities 2SLGBTQAI plus, weight, ethnicity, and religion). | |

| 2b. Group identity Comparison Variable | The group identity that differentiates one comparator group from the other for a specific work disparity (e.g., if a work disparity is identified between old and young workers, the group identity comparison variable would be ‘age’). The group identity comparison variable must be related to the demographic variables and must not be subjective in nature (e.g., job satisfaction cannot be a group identity comparison variable because it is a subjective measure). | |

| Note. Reprinted with permission from IOS Press | ||

References

- Bourgeault, I.L.; Maier, C.B.; Dieleman, M.; Ball, J.; MacKenzie, A.; Nancarrow, S.; Nigenda, G.; Sidat, M. The COVID-19 Pandemic Presents an Opportunity to Develop More Sustainable Health Workforces. Hum. Resour. Health 2020, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Ontario A Better Place to Live, a Better Place to Work: Ontario’s Long-Term Care Staffing Plan (2021-2025); 2020.

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing Fact Sheet: Nursing Shortage; 2024.

- Ontario Long Term Care Association [OLTCA] The Data: Long-Term Care in Ontario. Available online: https://www.oltca.com/about-long-term-care/the-data/ (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- United Nations Global Issues: Ageing. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/ageing (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- HRSA Health Workforce Nurse Workforce Projections, 2020-2035; 2022.

- Bae, S.-H.; Brewer, C. Mandatory Overtime Regulations and Nurse Overtime. Policy Polit. Nurs. Pract. 2010, 11, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, L.M.; Bates, T.; Spetz, J. The Association of Race, Ethnicity, and Wages Among Registered Nurses in Long-Term Care. Med. Care 2021, 59, S479–S485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holroyd-Leduc, J.M.; Laupacis, A. Continuing Care and COVID-19: A Canadian Tragedy That Must Not Be Allowed to Happen Again. CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J. J. Assoc. Medicale Can. 2020, 192, E632–E633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Donoso, L.M.; Moreno-Jiménez, J.; Amutio, A.; Gallego-Alberto, L.; Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Garrosa, E. Stressors, Job Resources, Fear of Contagion, and Secondary Traumatic Stress Among Nursing Home Workers in Face of the COVID-19: The Case of Spain. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2021, 40, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostaszkiewicz, J.; O’Connell, B.; Dunning, T. “We Just Do the Dirty Work”: Dealing with Incontinence, Courtesy Stigma and the Low Occupational Status of Carework in Long-Term Aged Care Facilities. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 2528–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Tian, W.; Liu, W.; Yang, Y. The Influence of Professional Identity on Work Engagement among Nurses Working in Nursing Homes in China. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 3022–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E.M.; Aiken, L.H.; McHugh, M.D. Registered Nurse Burnout, Job Dissatisfaction, and Missed Care in Nursing Homes. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 2065–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boamah, S.A.; Kalu, M.E.; Havaei, F.; McMillan, K.; Belita, E. Predictors of Nursing Faculty Job and Career Satisfaction, Turnover Intentions, and Professional Outlook: A National Survey. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, L.; Masood, M.; Neufeld, K.; Connelly, D.M.; Stanley, M.; Guitar, N.A.; Garnett, A.; Nikkhou, A. A Conceptual Framework for Defining Work Disparities: A Case of Nurses in Long Term Care. (under review WORK 2024).

- Leong, F.T.L.; Eggerth, D.E.; Chang, C.-H. (Daisy); Flynn, M.A.; Ford, J.K.; Martinez, R.O. Introduction. In Occupational health disparities: Improving the well-being of ethnic and racial minority workers; APA/MSU series on multicultural psychology; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, US, 2017; pp. 3–21; ISBN 978-1-4338-2692-4.

- Ndugga, N.; Pillai, D.; Artiga, S. Disparities in Health and Health Care: 5 Key Questions and Answers. KFF 2024.

- Antao, L.; Shaw, L.; Ollson, K.; Reen, K.; To, F.; Bossers, A.; Cooper, L. Chronic Pain in Episodic Illness and Its Influence on Work Occupations: A Scoping Review. Work Read. Mass 2013, 44, 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Constitution. Available online: https://www.who.int/about/governance/constitution (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- World Federation of Occupational Therapists (WFOT) About Occupational Therapy. Available online: https://wfot.org/about/about-occupational-therapy (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Le, A. Occupational Health Disparities. Available online: https://synergist.aiha.org/202305-occupational-health-disparities (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence Title Page. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. ; Editors JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Available online: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Canadian Institute for Health Information ICD-9/CCP and ICD-9-CM. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/en/icd-9ccp-and-icd-9-cm (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Mental Health Commission of Canada National Standard. Available online: https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/national-standard/ (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Ontario Health at Home Long-Term Care. Available online: https://ontariohealthathome.ca/long-term-care/ (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Hawker, S.; Payne, S.; Kerr, C.; Hardey, M.; Powell, J. Appraising the Evidence: Reviewing Disparate Data Systematically. Qual. Health Res. 2002, 12, 1284–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, L.; Rudman, D.L. Using Occupational Science to Study Occupational Transitions in the Realm of Work: From Micro to Macro Levels. Work Read. Mass 2009, 32, 361–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, L.; Jacobs, K.; Rudman, D.; Magalhaes, L.; Huot, S.; Prodinger, B.; Mandich, A.; Hocking, C.; Akande, V.; Backman, C.; et al. Directions for Advancing the Study of Work Transitions in the 21st Century. Work Read. Mass 2012, 41, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, L.; Thoren, C.; Joudrey, K. Retrospective Review of Work Transition Narratives: Advancing Occupational Perspectives and Strategies. Work Read. Mass 2023, 76, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, D.M.; Guitar, N.A.; Atkinson, A.N.; Janssen, S.M.; Snobelen, N. Learnings from Nursing Bridging Education Programs: A Scoping Review. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2023, 73, 103833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, S. Reforming Long-Term Care Requires a Diversity and Equity Approach. Available online: https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/may-2021/reforming-long-term-care-requires-a-diversity-and-equity-approach/ (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Galik, E. Learning to Be an Ally: Promoting Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Long-Term Care. Caring Ages 2022, 23, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, D.M.; Snobelen, N.; Garnett, A.; Guitar, N.; Flores-Sandoval, C.; Sinha, S.; Calver, J.; Pearson, D.; Smith-Carrier, T. Report on Fraying Resilience among the Ontario Registered Practical Nurse Workforce in Long-Term Care Homes during COVID-19. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 4359–4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, R.G.; Bartlett, R. Healthcare Worker Resilience during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Integrative Review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 2329–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.L.; Brown, J.A.; Rees, C.S.; Leslie, G.D. Nurse Resilience: A Concept Analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 29, 553–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, P.; Crawford, T.N.; Hulse, B.; Polivka, B.J. Resilience, Moral Distress, and Workplace Engagement in Emergency Department Nurses. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2021, 43, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.-C.; Huang, Y.-C.; Carter, P.; Zuniga, J. Resilience among Nurses in Long Term Care and Rehabilitation Settings. Appl. Nurs. Res. ANR 2021, 62, 151518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Ren, L.-N.; Liu, Y.; Liu, C.-J.; Su, X.-G.; Feng, B.-E. Resilience Training for Nurses: A Meta-Analysis. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. JHPN Off. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurses Assoc. 2021, 23, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaszak-Holl, J.; Castle, N.G.; Lin, M.K.; Shrivastwa, N.; Spreitzer, G. The Role of Organizational Culture in Retaining Nursing Workforce. The Gerontologist 2015, 55, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baughman, R.A.; Stanley, B.; Smith, K.E. Second Job Holding Among Direct Care Workers and Nurses: Implications for COVID-19 Transmission in Long-Term Care. Med. Care Res. Rev. MCRR 2022, 79, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratt, C.; Gautun, H. Should I Stay or Should I Go? Nurses’ Wishes to Leave Nursing Homes and Home Nursing. J. Nurs. Manag. 2018, 26, 1074–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castle, N.G.; Degenholtz, H.; Rosen, J. Determinants of Staff Job Satisfaction of Caregivers in Two Nursing Homes in Pennsylvania. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2006, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dill, J.; Duffy, M. Structural Racism And Black Women’s Employment In The US Health Care Sector. Health Aff. Proj. Hope 2022, 41, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duijs, S.E.; Abma, T.; Plak, O.; Jhingoeri, U.; Abena-Jaspers, Y.; Senoussi, N.; Mazurel, C.; Bourik, Z.; Verdonk, P. Squeezed out: Experienced Precariousness of Self-Employed Care Workers in Residential Long-Term Care, from an Intersectional Perspective. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, 1799–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elwér, S.; Aléx, L.; Hammarström, A. Gender (in)Equality among Employees in Elder Care: Implications for Health. Int. J. Equity Health 2012, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson, H.; Arnetz, J.E. Nursing Staff Competence, Work Strain, Stress and Satisfaction in Elderly Care: A Comparison of Home-Based Care and Nursing Homes. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 468–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiyak, H.A.; Namazi, K.H.; Kahana, E.F. Job Commitment and Turnover among Women Working in Facilities Serving Older Persons. Res. Aging 1997, 19, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krsnik, S.; Erjavec, K. Influence of Sociodemographic, Organizational, and Social Factors on Turnover Consideration Among Eldercare Workers: A Quantitative Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 6612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, D.; Cho, E.; Kim, G.S.; Lee, K.H.; Yoon, J.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Choi, M.H. Factors Associated with Retention Intention of Registered Nurses in Korean Nursing Homes. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2022, 69, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnfeld, M.; Wendsche, J.; Ihle, A.; Müller, S.R.; Kliegel, M. Uncovering the Care Setting-Turnover Intention Relationship of Geriatric Nurses. Eur. J. Ageing 2016, 13, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Hoeve, Y.; Drent, G.; Kastermans, M. Factors Related to Motivation, Organisational Climate and Work Engagement within the Practice Environment of Nurse Practitioners in the Netherlands. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 33, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Punnett, L.; Mawn, B.; Gore, R. Working Conditions and Mental Health of Nursing Staff in Nursing Homes. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2016, 37, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (Year) | Country* | Type of Study | Aim | Study Sample | No. of WDs | Use of WD Terms† | Quality Appraisal Score‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bae & Brewer (2010) [7] | USA | National Survey | To describe (a) the nature and occurrence of nurse mandatory and voluntary overtime as well as nurse paid on-call hours and (b) the associations with mandatory overtime regulations | N = 6,158 RNs | 6 | No | 30 (G) |

| Banaszak-Holl et al. (2015) [42] | USA | Cross-sectional Survey | To examine how organizational culture in nursing homes affects staff turnover. | N = 419 NH administrators | 1 | No | 31 (G) |

| Baughman et al. (2022) [43] | USA | National Survey | To estimate the rate at which direct care workers and nurses hold multiple jobs, the factors associated with multiple job holding, and the mix of employment across settings for those who do hold a second job. | N = 38,933 Direct care workers/Nurses | 5 | No | 33 (G) |

| Blanco-Donoso et al. (2021) [10] | SPA | Cross-sectional Survey | To analyze the psychological consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on nursing home workers, as well as the influence of certain related stressors and job resources. | N = 228 NH workers | 2 | No | 33 (G) |

| Bratt & Gautun (2018) [44] | UK | Cross-sectional Survey | To investigate the prevalence of nurses’ wishes to leave work in elderly care services and aims to explain differences between younger and older nurses. | N = 4,945 Nurses | 2 | No | 35 (G) |

| Castle et al. (2006) [45] | USA | Cross-sectional Survey | To examine job satisfaction scores of these caregivers and what characteristics of these caregivers are associated with job satisfaction. | N = 574 NH caregivers | 6 | No | 33 (G) |

| Dill & Duffy (2022) [46] | USA | National Survey | To describe how structural racism and sexism shape the employment trajectories of Black women in the US health care system | N = 125,800 Healthcare workers | 2 | No | 32 (G) |

| Duijis et al. (2023) [47] | NET | Qualitative Analysis | To understand self-employed long-term-care workers' experiences of precariousness, and to unravel how their experiences are shaped at the intersection of gender, class, race, migration and age. | N = 23 Self-employed nurses and NAs in LTC | 2 | Yes; 'Inequalities' | 36 (G) |

| Elwér et al. (2012) [48] | SWE | Qualitative Analysis | To analyze what gender (in)equality means for the employees at a woman-dominated workplace and to discuss possible implications for health experiences | N = 45 NH workers | 4 | Yes; 'Inequalities' | 34 (G) |

| Hasson & Arnetz (2008) [49] | SWE | Cross-sectional Survey | To compare older people care nursing staff’s perceptions of their competence, work strain and work satisfaction in nursing homes and home-based care; and to examine determinants of work satisfaction in both care settings | N = 863 Nursing staff | 2 | No | 32 (G) |

| Kiyak et al. (1997) [50] | USA | Modelling predictive study | To integrate previous approaches to studying turnover in organizations serving elderly persons | N = 308 NH/community agency employees | 3 | No | 26 (F) |

| Krsnik & Erjavec (2023) [51] | SLO | Cross-sectional Survey | To use multivariate analysis to identify the factors at the macro-, meso-, and micro-level that influence LTC workers’ turnover in Slovenia, a typical Central and Eastern European country. | N = 452 LTC workers | 3 | No | 25 (F) |

| Min et al. (2022) [52] | KOR | Mixed-Methods | To identify the factors associated with retention intention among Registered Nurses in South Korean nursing homes | N = 155 RNs | 4 | No | 34 (G) |

| Rahnfeld et al. (2016) [53] | GER | Cross-sectional Survey | To examine mediators in the relationship between care setting and turnover intentions | N = 278 RNs and NAs | 1 | No | 29 (G) |

| TenHoeve et al. (2024) [54] | NET | Cross-sectional Survey | To explore motivation, organisational climate, work engagement and related factors within the practice environment of nurse practitioners | N = 586 NPs | 4 | No | 33 (G) |

| Zhang et al. (2016) [55] | USA | Cross-sectional Survey | To evaluate the association between working conditions and mental health among different nursing groups, and examine the potential moderating effect of job group on this association | N = 1,129 Nursing staff | 3 | Yes; 'Disparity of working conditions' | 32 (G) |

| Comparator Group Subdivision | ||||||

| S-INTRA | S-INTER | M-INTRA | M-INTER | Total | ||

| Variable of Work Disparity Categorization | Job Security | 0 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 8 |

| Work Compensation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 8 | |

| Work Opportunities | 6 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 19 | |

| Workplace Treatment | 0 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 18 | |

| Total | 7 | 14 | 21 | 11 | 53 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).