1. Introduction

Vibrio vulnificus is an emerging zoonotic pathogen that inhabits marine and brackish water ecosystems in temperate, tropical, and subtropical zone [

1,

2]. This species is considered a biomarker of climate change because rising water temperatures are causing its poleward expansion and proliferation in coastal waters [

3]. Additionally, the increase in water temperature causes an upregulation of virulence factors involved in immune system resistance, which in turn increases the virulence of outbreaks [

4].

As a human pathogen,

V. vulnificus causes sporadic severe infections (human Vv-vibriosis) in wounds exposed to seawater or after contact with diseased fish, as well as gastroenteritis following the consumption of raw seafood [

1,

5]. Both types of Vv-vibriosis can lead to sepsis and death, especially in at-risk patients [

1,

5]. As an animal pathogen, it causes outbreaks of hemorrhagic septicemia (fish vibriosis) that are particularly severe in farmed European eel (

Anguilla anguilla (Linnaeus, 1758)), its most susceptible host [

6]. Notably, fish Vv-vibriosis can be transmitted via water and ingestion, although water is the primary transmission route [

7,

8].

The species is divided into five phylogenetic lineages plus a pathovariety, named piscis [

9]. It is believed that strains from all five lineages can cause human Vv-vibriosis, but only those from the pathovar piscis can cause fish Vv-vibriosis due to the acquisition of a transferable virulence plasmid (pVir) [

10]. Recently, it has been reported that pVir, initially present in some clones of lineage 2, has already been transferred to four of the five lineages of the species, a process linked to fish farms as these artificial environments can favor genetic exchange between bacteria [

11]. Therefore, aquaculture industry is a determining factor in the recent evolution and epidemic spread of this species [

11]. Additionally, recent evidence shows that pVir has been transferred to other fish pathogens such as V. harveyi, a marine pathogen with a broad host spectrum [

11].

From a One Health perspective, controlling Vv-vibriosis outbreaks on farms would be essential not only for animal but also for human health, as it would reduce the risk of Vv-transmission to humans. Vv-vibriosis can be treated and cured with antibiotics [

12,

13,

14]. Although the antibiotics used in human (HAa) and fish therapy differ, the use of antibiotics in aquaculture can promote the emergence of resistance to HAa through cross-resistance, particularly among antibiotics of the same family (e.g., oxytetracycline and tetracycline) [

15]. Therefore, the use of antibiotics on farms should be minimized in favor of other therapeutic methods.

This study addresses this issue and suggests that one way to control infectious outbreaks at farms is to reduce the microbial load in the water, especially pathogens, in aquaculture facilities. There are already developed methods for reducing microbial load, including physical (filtration, UV radiation, ozonization) and chemical (H

2O

2, peracetic acid, and chlorinated disinfectants) approaches [

16], but many generate toxic residues.

Considering all the above, this study selected and tested electrolyzed water (EW) as an alternative method to control the pathogen

V. vulnificus. EW has proven to be a highly effective bactericide in the food and healthcare industries [

17,

18,

19,

20] and offers the advantage of not generating toxic residues, making it environmentally friendly. In addition, another advantage is that it has a low generation cost [

21].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Cultures

Representative strains of the five phylogenetic lineages of

V. vulnificus [

9], were utilized in this study (

Table 1). The strains were routinely cultured on plates of TSA-1 (trypticase soy agar plus 5 g/L NaCl) or in tubes of LB-1 (Luria Bertani broth plus 5 g/L NaCl) at 28°C for 24 hours and were maintained in frozen stocks at -80°C in LB-1-glycerol (ratio 1:5).

2.2. Electrolyzed Water (EW) Preparation and Characterizacion

EW was generated using a LAMI-50 generator (Aquactiva Solutions S.L.), equipped with a membrane electrolysis cell. A solution of saturated NaCl and deionized water was utilized, eliminating the need for inlet water treatment. EW was characterized for pH, oxidation-reduction potential (ORP), and conductivity using the SG68 pH/Ion/DO Multimeter (Mettler Toledo). Free available chlorine (FAC) was measured with a Handled Colorimeter Chlorine UHR (Hanna Instruments). The physic-chemical parameters of EW tested in this work are shown in

Table 2. Due to the instability of EW, all experiments were conducted immediately after its generation.

2.3. Bacterial survival in EW

The bactericidal effect of EW on

V. vulnificus was evaluated in microcosms under different conditions of salinity (3% and 1.5%), pH (5, 6.5 and 7.5) and FAC (5, 25 and 125 ppm) (

Table 2) at 0-, 5-, 10- and 15-min post-inoculation. The salinity and pH values were selected based on the average values in seawater, estuaries and fish farms while the FAC values and action time were selected from the results obtained by other researchers [

22]. To this end, overnight LB-1 cultures of

V. vulnificus were diluted 1:100 in fresh LB-1 and, then were inoculated (1:10 ratio) into freshly prepared EW (final volume, 100 mL) and PBS (positive control) to achieve a bacterial population size of 10

6 CFU/ml, the 50% lethal dose of this pathogen for bath-infected fish [

7,

11,

23] . Survivors were then estimated by drop-counting on TSA-1 plates (limit detection 100 UFC/ml) [

24]. The bactericidal effect of EW was only considered if survival percentage in the control after 15 min incubation was 100%. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

An analysis of variance of aligned rank transformed (ART ANOVA) was employed to test for significant differences in bacterial counts using R (version 4.3.2). When ART ANOVA indicated significance (p < 0.05), post hoc analyses were performed with p-values adjusted by Tukey’s method. Homoscedasticity and normality were tested prior to analysis. Significant heterogeneity and non-normal distribution were observed in some data groups, justifying the use of non-parametric tests. Effect sizes for different factors were analyzed using partial eta squared (η2).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Influence of Salinity, pH and FAC on the Bactericidal Activity of EW

Bacterial survival experiments with EW containing 5 ppm FAC (EW-5) showed that, at this chlorine concentration, EW was not bactericidal at any tested salinity and pH, with bacterial survival being 100% at all times tested (data not shown). In contrast, EW-125 was highly bactericidal regardless of salinity and pH, causing a population reduction of more than 4 log units in less than one minute (data not shown). Both concentrations of FAC were discarded for further experiments, the former as ineffective and the latter because of its potential toxic effect on fish according to Kasai et al. [

25]. This does not exclude the value of EW-125 as a powerful disinfectant for potential use in non-animal aquaatic facilities, equipment, food products or even fish farm effluent water [

26].

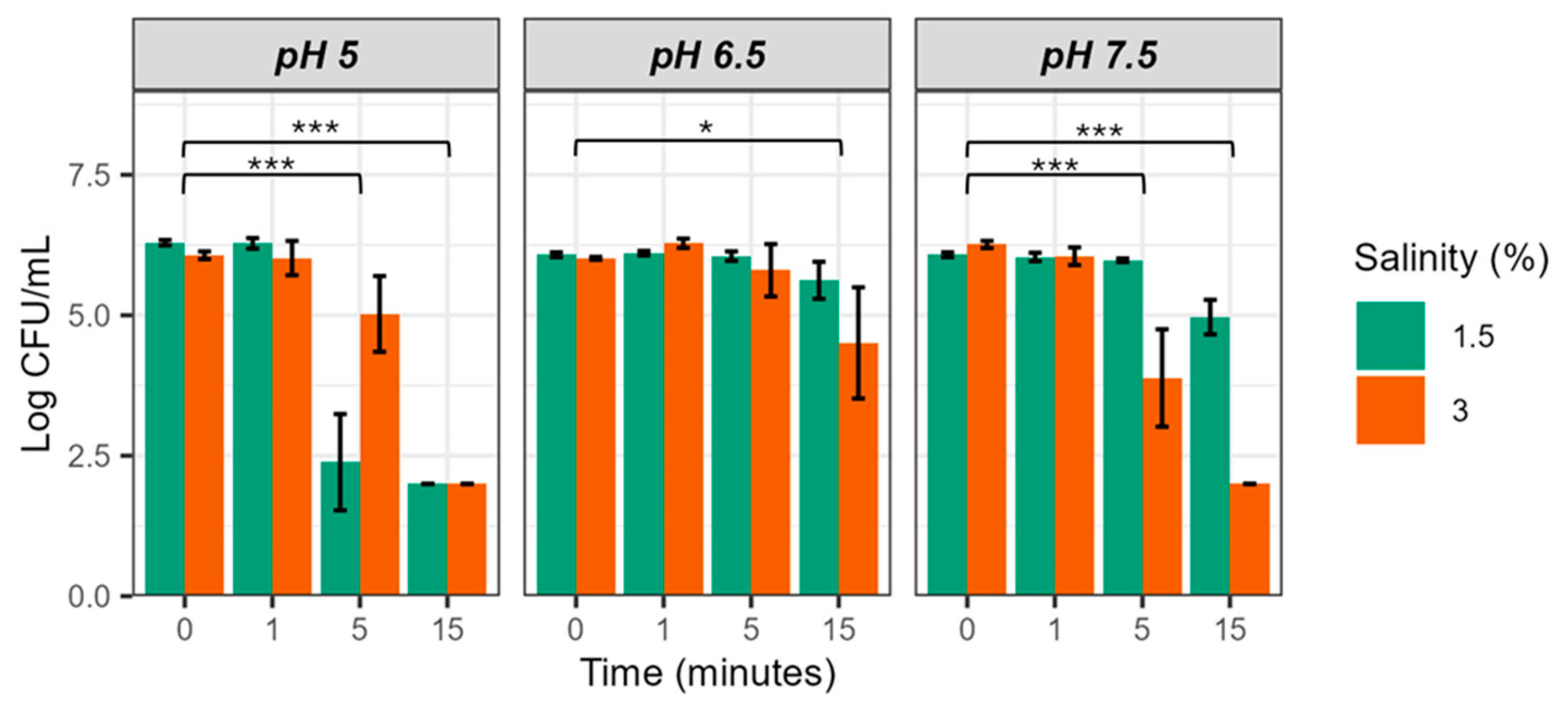

Figure 1 shows the survival of strain CECT 4999 in EW-25 at 1.5 and 3% salt at the different pH values tested. Bacterial populations decreased significantly with incubation time in all conditions, although with differences depending on pH and salinity. Thus, at pH 5 and 7.5 the bactericidal effect at 5 and 15 min was greater than at pH 6.5, regardless of water salinity, apparently being faster and more intense in water of 1.5% salinity at pH 5 (conditions used in some aquaculture facilities) and in water of 3% salinity at pH 7.5 (conditions close to seawater) (

Figure 1). In fact, no colony was recovered from EW-25 at the two salinities and pH 5 as well as at 3% salinity and pH 7.5 at 15 min of incubation. These results show that EW-25 reduces bacterial population in more than 4 log units (

Figure 1).

ART ANOVA analysis confirmed all the above observations, revealing that both pH and water salinity have a significant effect on bacterial survival, but salinity interactions do not (

Table 3). Furthermore, time and its interaction with pH also have a significant effect. It should be noted that post hoc analysis of the data also revealed significant differences as a function of incubation time, except for the samples corresponding to times 0 and 1 min, suggesting that more than one minute of exposure is necessary for EW-25 to produce the bactericidal effect (

Figure 1).

The partial eta squared value was then determined to ascertain the magnitude of the effect of each factor on the variance of the data. The time factor explained the greatest variance (80.79%), followed by pH (21.36%) and salinity (14.51%). Based on these results, we conclude that EW-25 can be bactericidal at any water pH and salinity as long as the time of action is adjusted to achieve the desired effect.

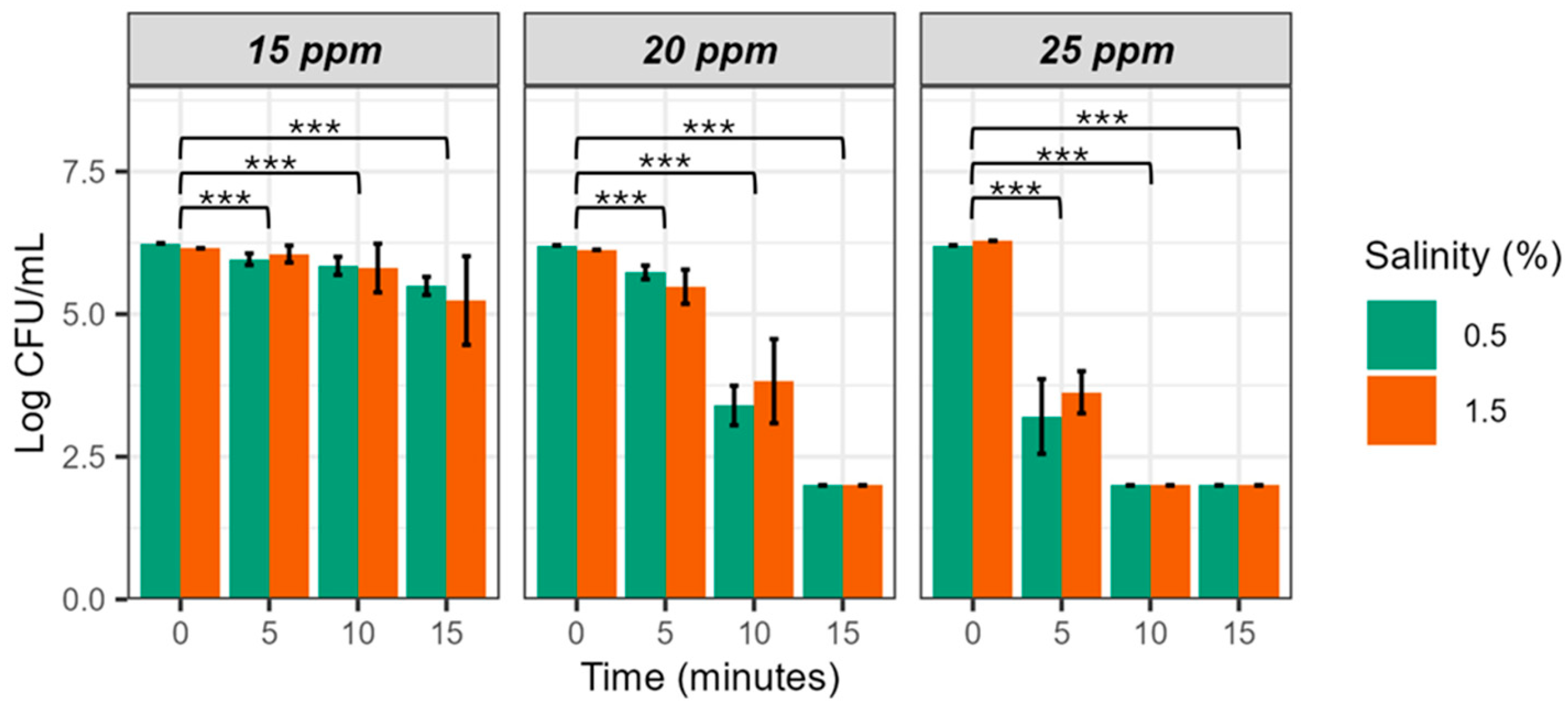

Figure 2 shows bacterial survival in EW adjusted to pH 5 at different FAC concentrations (EW-15, -20 and 25). As we expected, the bactericidal effect was more rapid and intense at the highest concentration (5 min, 2.5 log unit reduction), intermediate at the middle concentration (10 min, 2 log unit reduction) and low at the lowest concentration (15 min, 1 log unit reduction).

ART ANOVA statistical analysis revealed significant differences for the three factors and the three 2-to-2 interactions (

Table 4), and post-hoc analysis, significant differences as a function of time. Finally, partial eta squared analysis showed that exposure time explaining the greatest variation (85.41%), followed by FAC (74.12%) and salinity (10.44%).

Of the three FAC concentrations tested, we discarded the lowest because of its poor efficacy and the highest because of its toxicity to animals [

25]. Consequently, we selected EW-20 for the rest of the experiments. It has been suggested that similar concentrations may be non-toxic for different species of aquatic animals when used int he facilities [

26].

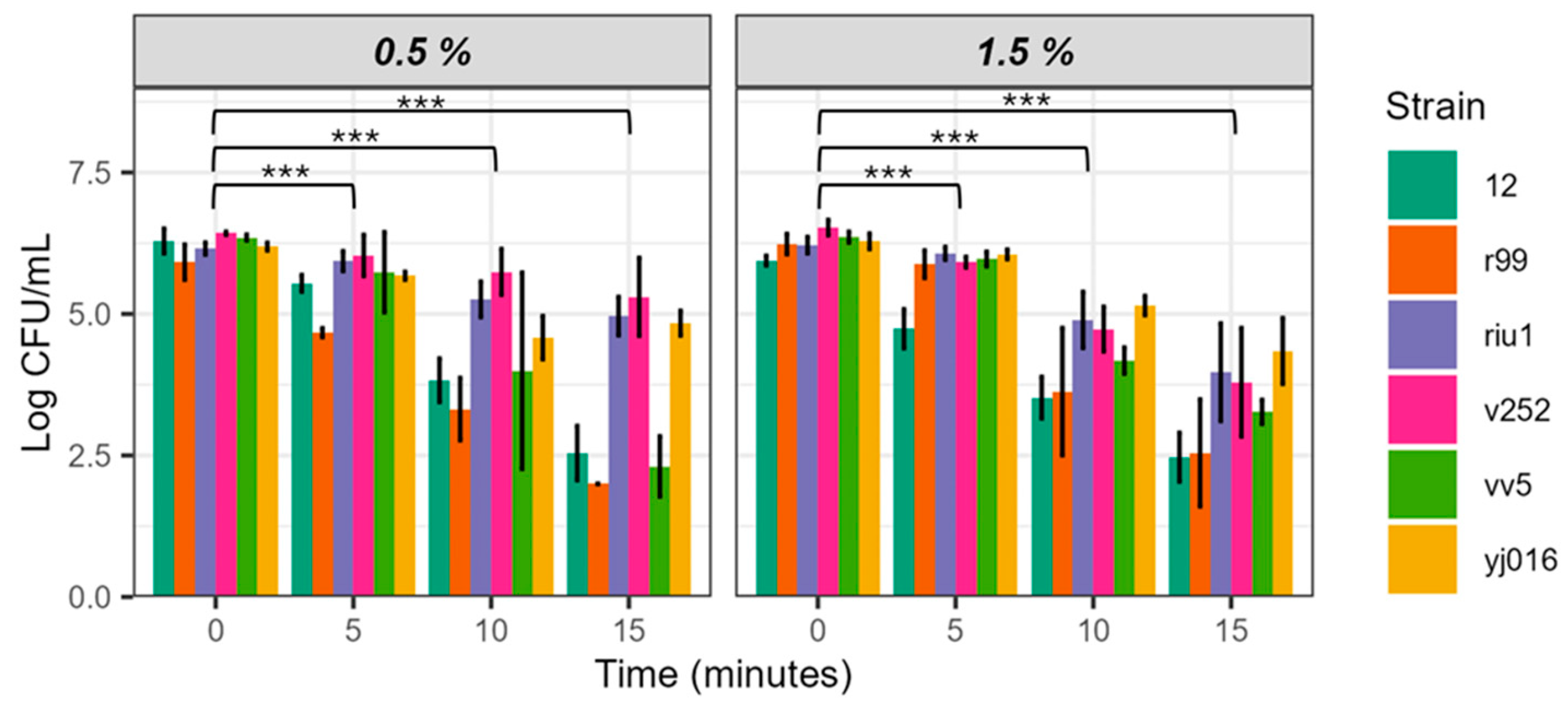

3.2. Evaluation of the Bactericidal Effect on Different Strains of V. vulnificus

V. vulnificus is a genetically variable species, so we decided to evaluate the bactericidal power of EW-20 against strains representative of the five phylogenetic lineages described in the species by adjusting salinity to 0.5 and 1.5, and pH to 5 (

Figure 3). For these experiments we selected parameters closely adjusted to the pH and salinity values used in fish farms in our geographical area.

The populations of the 5 strains decreased over time at the two salinities tested, but apparently with differences among them and between salinities (

Figure 3). Thus, strains V12 (L3) and CECT 4999 (L2) were the most sensitive to both salinities while strains Riu1 (L4), V252 (L5) and YJ016 (L1) resisted the treatment better and strain VV5 gave different survival values according to salinity.

ART ANOVA analysis showed that water salinity did not significantly influence EW-20 efficacy, but sampling time did (

Table 5). It also showed that the differences between strains were significant, confirming that intraspecific genetic differences affect the resistance of the isolate to the bactericidal action of EW-20, although, for the moment, we do not know what the genetic basis is. Finally, the time parameter, again, explains the greatest variance in the data (83.13%), followed by the strain factor (48.65%) and salinity (2.35%). In any case, the reduction obtained in the population sizes of the five strains was significant, ranging from 1 to 2.5 log units at 15 min of incubation (

Figure 3).

In summary, we have demonstrated the efficacy of EW against

V. vulnificus at FAC concentrations of 20 ppm, and salinity and pH compatible with those used in fish farms where fish species susceptible to Vv-vibriosis are raised (around pH 5.5 and 0.5% salinity). There are other studies evaluating the efficacy of EW against different pathogens [

22,

27]. However, we cannot compare our results with those obtained in these studies because they used FAC concentrations and pH incompatible with animal life and initial bacterial concentrations far away from those found in aquaculture facilities (around 10

3-8 CFU/ml). Finally, although the concentration of FAC that we selected is not toxic for multiple marine animals, we recommend to confirm its non-toxicity for the target species before using EW treatment in aquaculture facilities.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that EW is an effective disinfectant against the zoonotic pathogen V. vulnificus, regardless of lineage and strain: it reduces significantly V. vulnificus populations at FAC concentrations of 20 and 25 ppm and at water parameters compatible with the water of eel and tilapia farms, its main hosts (pH 5.5, salinity 0.5%). This treatment constitutes an environmentally friendly alternative to antibiotics therapy, as it would keep V. vulnificus populations under control in fish farms, reducing the probability of Vv-vibriosis outbreaks and, therefore, the use of antibiotics. Finally, from a “One Health” perspective, controlling Vv-vibriosis outbreaks in fish farms is essential not only for animal health, but also for human health, as it reduces the risk of transmission of V. vulnificus to humans, which is especially relevant as this pathogen is clearly expanding due to global warming.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and experimental design, J-V. R. L., BF and CA; supervision of experiments, J-V. R. L., BF and CA; execution of the experiments, P. I.-P. and A. B.; writing of the original draft, P. I.-P. and A. B..; writing-revising and editing, J-V. R. L., BF and CA; funding, J-V. R. L., BF, and CA. All authors have read and accepted the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by grants THINKINAZUL/2021/027 and 028 from MCIN (Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación de España) with funds from European Union Next Generation EU (PRTR-C17.I1) and GV (Generalitat Valenciana); PID2020-120619RB-I00 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and CIAICO/2021/293 by “Conselleria de Innovacion, Universidades, Ciencia y Sociedad Digital” (GV, Spain). P. Ibáñez got funds from grant MRR-GVA Programa Investigo 2022.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data can be found in the following link.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Oliver, J.D. The Biology of Vibrio vulnificus. Microbiol Spectr 2015, 3, 3–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Cabanyero, C.; Amaro, C. Phylogeny and Life Cycle of the Zoonotic Pathogen Vibrio vulnificus. Environmental Microbiology 2020, 22, 4133–4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker-Austin, C.; Trinanes, J.; Gonzalez-Escalona, N.; Martinez-Urtaza, J. Non-Cholera Vibrios: The Microbial Barometer of Climate Change. Trends in Microbiology 2017, 25, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Cabanyero, C.; Sanjuán, E.; Fouz, B.; Pajuelo, D.; Vallejos-Vidal, E.; Reyes-López, F.E.; Amaro, C. The Effect of the Environmental Temperature on the Adaptation to Host in the Zoonotic Pathogen Vibrio vulnificus. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Austin, C.; Oliver, J.D. Vibrio vulnificus : New Insights into a Deadly Opportunistic Pathogen. Environmental Microbiology 2018, 20, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, C.; Sanjuán, E.; Fouz, B.; Pajuelo, D.; Lee, C.-T.; Hor, L.-I.; Barrera, R. The Fish Pathogen Vibrio vulnificus Biotype 2: Epidemiology, Phylogeny, and Virulence Factors Involved in Warm-Water Vibriosis. Microbiol Spectr 2015, 3, 3–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, C.; Biosca, E.G.; Fouz, B.; Alcaide, E.; Esteve, C. Evidence That Water Transmits Vibrio vulnificus Biotype 2 Infections to Eels. Appl Environ Microbiol 1995, 61, 1133–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marco-Noales, E.; Milán, M.; Fouz, B.; Sanjuán, E.; Amaro, C. Transmission to Eels, Portals of Entry, and Putative Reservoirs of Vibrio vulnificus Serovar E (Biotype 2). Appl Environ Microbiol 2001, 67, 4717–4725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roig, F.J.; González-Candelas, F.; Sanjuán, E.; Fouz, B.; Feil, E.J.; Llorens, C.; Baker-Austin, C.; Oliver, J.D.; Danin-Poleg, Y.; Gibas, C.J.; et al. Phylogeny of Vibrio vulnificus from the Analysis of the Core-Genome: Implications for Intra-Species Taxonomy. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-T.; Amaro, C.; Wu, K.-M.; Valiente, E.; Chang, Y.-F.; Tsai, S.-F.; Chang, C.-H.; Hor, L.-I. A Common Virulence Plasmid in Biotype 2 Vibrio vulnificus and Its Dissemination Aided by a Conjugal Plasmid. J Bacteriol 2008, 190, 1638–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Salido, H.; Fouz, B.; Sanjuán, E.; Carda, M.; Delannoy, C.M.J.; García-González, N.; González-Candelas, F.; Amaro, C. The Widespread Presence of a Family of Fish Virulence Plasmids in Vibrio vulnificus Stresses Its Relevance as a Zoonotic Pathogen Linked to Fish Farms. Emerging Microbes & Infections 2021, 10, 2128–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Austin, C.; McArthur, J.V.; Lindell, A.H.; Wright, M.S.; Tuckfield, R.C.; Gooch, J.; Warner, L.; Oliver, J.; Stepanauskas, R. Multi-Site Analysis Reveals Widespread Antibiotic Resistance in the Marine Pathogen Vibrio vulnificus. Microb Ecol 2009, 57, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmahdi, S.; DaSilva, L.V.; Parveen, S. Antibiotic Resistance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus in Various Countries: A Review. Food Microbiology 2016, 57, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, S.-P.; Letchumanan, V.; Deng, C.-Y.; Ab Mutalib, N.-S.; Khan, T.M.; Chuah, L.-H.; Chan, K.-G.; Goh, B.-H.; Pusparajah, P.; Lee, L.-H. Vibrio vulnificus: An Environmental and Clinical Burden. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.K.; Bhunia, A.K. Animal-Use Antibiotics Induce Cross-Resistance in Bacterial Pathogens to Human Therapeutic Antibiotics. Curr Microbiol 2019, 76, 1112–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cui, Z.; Cui, H.; Bai, Y.; Yin, Z.; Qu, K. A Review of Influencing Factors on a Recirculating Aquaculture System: Environmental Conditions, Feeding Strategies, and Disinfection Methods. J World Aquaculture Soc 2023, 54, 566–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Hung, Y.-C.; Brackett, R.E. Efficacy of Electrolyzed Oxidizing (EO) and Chemically Modified Water on Different Types of Foodborne Pathogens. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2000, 61, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E. -J.; Alexander, E.; Taylor, G.A.; Costa, R.; Kang, D. -H. Effect of Electrolyzed Water for Reduction of Foodborne Pathogens on Lettuce and Spinach. Journal of Food Science 2008, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Daliri, E.B.-M.; Oh, D.-H. New Clinical Applications of Electrolyzed Water: A Review. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.-K.; Wang, C.-K. Electrolyzed Water and Its Pharmacological Activities: A Mini-Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, C.F.; Ming, L.C.; Wong, L.C. Dermatologic Reactions to Disinfectant Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Clinics in Dermatology 2021, 39, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkitanarayanan, K.S.; Ezeike, G.O.; Hung, Y.-C.; Doyle, M.P. Efficacy of Electrolyzed Oxidizing Water for Inactivating Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella enteritidis, and Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol 1999, 65, 4276–4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaro, C.; Biosca, E.G. Vibrio vulnificus Biotype 2, Pathogenic for Eels, Is Also an Opportunistic Pathogen for Humans. Appl Environ Microbiol 1996, 62, 1454–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoben, H.J.; Somasegaran, P. Comparison of the Pour, Spread, and Drop Plate Methods for Enumeration of Rhizobium spp. in Inoculants Made from Presterilized Peat. Appl Environ Microbiol 1982, 44, 1246–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasai, H.; Kawana, K.; Labaiden, M.; Namba, K.; Yoshimizu, M. Elimination of Escherichia coli from Oysters Using Electrolyzed Seawater. Aquaculture 2011, 319, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayose, M.; Yoshida, K.; Achiwa, N.; Eguchi, M. Safety of Electrolyzed Seawater for Use in Aquaculture. Aquaculture 2007, 264, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Song, X.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, J.; Wang, X.; Malakar, P.K.; Liu, H.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, Y. Removal of Foodborne Pathogen Biofilms by Acidic Electrolyzed Water. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).