1. Introduction

Water scarcity has become a critical global issue due to significant climate shifts and societal developments in recent decades [

1]. It poses a severe threat to human sustainability, ecosystem balance, and socio-economic progress [

2,

3]. As the world’s population continues to grow, the demand for water rises sharply, highlighting a stark disparity between regions with plentiful water supplies and those grappling with severe shortages and pollution [

4]. This imbalance often leads to conflicts over water distribution, underscoring the need for improved water management and infrastructure planning across continents, especially in arid regions where economic dependence on water is high [

5,

6,

7]. The looming threat of climate change is expected to worsen freshwater limitations, further emphasizing that addressing this issue remains paramount for the 21st century’s economy and global public health [

8,

9].

Decisions about water use and distribution have been occurring for millennia, starting with the development of irrigation systems to facilitate agricultural expansion and progressing into the sophisticated automated monitoring and operational frameworks present today [

10]. Water management is an increasingly significant issue globally. There exists a wide array of organizational models, with varying distributions of responsibilities among stakeholders dependent on regulatory frameworks. In the realm of water distribution and sanitation alone, there are diverse national, regional, or local organizational arrangements that may be entirely private, have mixed ownership, or are fully public in nature, each carrying different levels of responsibility [

11]. These different organizational structures and decision-making processes have a direct impact on water availability, accessibility, and quality [

12]. In order to achieve the proficient management of water resources, a variety of strategies and instruments have been deployed to assess the mechanisms that dictate the dynamics of water resources in any given area. Nevertheless, numerous physiological, socio-economic, and institutional interconnections exist within the worldwide water system [

13].

Water management poses a crucial challenge to the sustainability of human beings. Issues concerning the quantity and quality of water, as well as access to it, present significant challenges for both society and ecosystems [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Addressing these challenges requires us to consider the system’s dynamics. This encompasses the general sociopolitical processes, operational decision-making, and management that affect the dynamics of the water cycle. Currently, water management primarily focuses on surface waters, land, and climate governance [

19]. However, numerous studies [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27] suggest that the interaction between agents and their engagement with nature is crucial for effective water management. Water scarcity is not solely a result of natural occurrences such as reduced rainfall or decreased water flow in rivers due to climate change and melting glaciers; it is also influenced by various social aspects connected to land use and the distribution of water resources [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Many places around the world experience an imbalance in power dynamics when it comes to the availability, usage, and management of water [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40].

The relationship between water management and power is less about new technologies or frameworks and more about relations between different actors and whether and to what extent those relations can be transformed. This paper explores Pierre Bourdieu’s work on power in relation to water management, drawing upon the central concepts of field, capital, habitus, and doxa from his theory.

Different studies have addressed Bourdieu’s theory to study the problems of water management: The authors of [

41] discussed the management of water resources in local communities from a social capital perspective. A comparative case study was conducted in two regions in Kepulauan Riau, Senggarang, and Mantang to explore the role of social capital in governing water resources. The findings contribute to understanding the importance of social capital for local water resource management. In [

42], a case study applying Bourdieu’s field theory to understanding social interactions and interests among agents was conducted. Effective water management requires not only technical solutions but also a deep understanding of the cultural and social factors that shape human interactions with water resources. In the paper “Pour une sociologie de la perception” [

43], the relationship between Quattrocento painters and their patrons is described as being influenced by economic, social, and cultural factors. Patrons dictate criteria regarding materials and techniques when commissioning a piece, thus shaping both the content and aesthetic value of the artwork based on their perceptions. The Quattrocento merchant seeks rich colors and exquisite technique as indicators of value when buying a painting. Aesthetic pleasure is found in recognizing oneself, feeling at home, and understanding the world through artistic contemplation. Happiness results from the successful comprehension of the artwork, creating an immediate agreement with the world. The government, like a patron, needs to balance these expectations by ensuring that water policies are both practical and responsive to users’ needs. Water management as a social field involves recognizing and addressing the needs and expectations of agents, ensuring practical solutions that are responsive to users’ requirements. This recognition fosters a sense of well-being and trust in the system, similar to how artistic contemplation results in agreement with the artwork on a preconscious level. The objective of the water management social field should be to ensure that the resource is accessible to all agents and guarantee its long-term sustainability.

The study revealed diverse stakeholder perspectives and strategies that create barriers to stable relationships. It suggests that governance should consider sociological perspectives alongside technological solutions for the effective management of water quality issues.

2. Water Management Approaches

A global shift is happening in water management, moving away from traditional command-and-control methods to social–ecological systems (SESs) approaches, such as integrated water resources management (IWRM), the water–energy–food nexus, nature-based solutions, and socio-hydrology; these new approaches aim to make decisions that benefit both people and ecosystems by integrating various issues, sectors, and disciplines [

44]. In recognizing the importance of these approaches, our first step will be to conduct a literature review for each of them. This review not only highlights the theoretical foundations and fundamental principles of these methodologies but also explores their practical applications, relevant case studies, and lessons learned across different geographical and socio-economic contexts.

2.1. Integrated Water Resources Management

Integrated water resources management (IWRM) is recognized as a process that promotes the co-ordinated development and management of water, land, and related resources in order to maximize economic and social welfare in an equitable manner without compromising the sustainability of vital ecosystems [

45]. IWRM embodies a holistic approach to water management and is based on four main principles: recognizing freshwater as a finite and essential resource; promoting participatory management by linking all stakeholders; highlighting the essential role of women in water management; and valuing water as both an economic and social good [

45]. IWRM is a flexible and goal-directed process that can be adapted to various objectives, such as enhancing agricultural development and improving human welfare. It highlights the importance of creating an enabling environment through suitable policies and institutional frameworks, promoting integration to ensure effective co-ordination and co-operation among diverse users. This approach aims to balance social, economic, and environmental needs while ensuring water sustainability without harming ecosystems [

46].

IWRM is widely applied in contemporary water management, as supported by the summaries of studies across different countries and contexts. Cameroon exemplifies the potential of IWRM in achieving sustainable water resource management despite challenges such as rapid population growth and urbanization. The country suggests reforms for better implementation, including public participation and acknowledging water as both an economic and social asset [

47]. In Nigeria, there is growing support for the feasibility of IWRM despite obstacles such as inadequate water governance. Its recommendations suggest an iterative and adaptable approach to IWRM implementation aimed at addressing specific water issues [

48]. Research in Uganda’s Lake Albert basin shows that IWRM practices result in significantly improved water resources governance compared to areas without such practices, highlighting the importance of good governance in effective water management [

49]. A systematic review in East, West, and Southern Africa identifies themes, such as donor influence and water scarcity, that affect the implementation of IWRM strategies, raising questions about the success of IWRM across the African continent [

50]. A case study in India illustrates the effectiveness of ‘Local IWRM’ planning in managing water and land resources, emphasizing the importance of participatory planning and the potential for implementation at the district level [

51]. The development and application of an IWRM indicators framework in Morocco’s R’Dom sub-basin as part of the Meknes Region demonstrates stakeholders’ efforts towards implementing IWRM while also highlighting areas that require significant improvement [

52]. Colombia’s policy on water resource management aims for sustainability through integrated management but faces challenges in understanding the balance between water supply and demand, highlighting the need for improved co-ordination and governance [

53].

Despite its widespread adoption as a leading approach in the water sector, IWRM is often criticized for its practical and theoretical limitations due to real-world complexities such as political negotiation and power dynamics. These factors hinder the achievement of integrative goals despite aiming for a holistic and participatory approach. While it emphasizes communicative rationality and stakeholder participation, it may not effectively address inherent power imbalances in real-world situations [

54,

55].

2.2. Water–Energy–Food Nexus

The ‘water–energy–food nexus’ approach gained prominence following the Bonn Conference in 2011. The water–energy–food nexus approach highlights the interconnectedness and interdependence of water, energy, and food security. It aims to improve efficiency in resource use across these sectors by addressing external factors and promoting sustainable management practices. This comprehensive approach suggests considering the productivity of water, energy, and land as a system rather than individually, identifying opportunities to enhance efficiency through innovation, recycling, and waste reduction. By prioritizing overall system effectiveness over individual sector productivity, the nexus approach promotes a shift towards sustainability with fewer trade-offs while yielding benefits that outweigh integration costs. Its goal is to encourage economic development through incentives, enhance governance for cross-sectoral management, and leverage productive ecosystems—contributing to a green economy that enhances human well-being and social equality and reduces environmental risks and ecological scarcities [

56]. The water–energy–food nexus approach offers a significant advantage compared to the IWRM framework, as it gives equal weight to all components, which is in contrast to the exclusive emphasis placed on water in IWRM [

57].

The water–energy–food nexus approach has gained global traction as an innovative framework for addressing the interconnected challenges of managing water, energy, and food security in a sustainable and integrated manner. It has been implemented in numerous regions around the world. In the Great Plains of the United States, frequent drought events have led to the development of an integrated WEF nexus modeling and optimization approach for effectively managing agricultural droughts [

58]. This study established a comprehensive agricultural drought management system that integrates real-time monitoring with irrigation management; the water–food–energy relationship showed that significant investments in water and energy are required to limit the negative effects of drought. In Iran’s Shazand watershed, researchers used a linear optimization model to apply the WEF nexus approach. Their aim was to maximize the water–energy–food nexus index. This approach allowed them to assess the connections among water, energy, and food sectors, revealing potential for increased resource use efficiency and sustainable intensification of agricultural practices [

59]. The development of an optimization module for a nationwide WEF nexus simulation model in Korea highlights the approach’s usefulness in helping stakeholders make informed decisions for sustainable resource management. The model offers valuable insights into minimizing negative impacts and maximizing user reliability across water, energy, and food sectors by optimizing resource allocation under plausible drought scenarios [

60]. In Latin America, especially in Colombia, a suggested framework for water management at the WEF nexus has been developed. The research examines how factors related to the WEF nexus impact water management in terms of its quality and availability by analyzing a mixed land-use watershed in the Andean region. This effort seeks to apply an urban WEF nexus framework at the watershed level, demonstrating its capacity to be utilized in varied geographical and socio-economic settings [

61].

The potential of the water–energy–food nexus approach has been widely discussed in the literature, with one notable concern being that studies have primarily focused on macro-scale global resource security, overlooking impacts on local livelihoods and the environment [

57]. Furthermore, there has been a lack of participatory stakeholder involvement in designing and carrying out nexus research [

62].

2.3. Nature-Based Solutions

The term ‘nature-based solutions’ (NBSs) first appeared in the early 2000s in the context of addressing agricultural problems. Since then, NBSs have been discussed in relation to land use management, planning, and water resource management, such as using wetlands for wastewater treatment and leveraging ecosystem services from wetlands as a nature-based approach to watershed management. NBSs are systems that utilize and reinforce physical, chemical, and microbiological treatment processes. These processes underpin the scientific and engineering principles for water/wastewater treatment and hydraulic infrastructure. NBSs can be cost-effective, energy-efficient, and environmentally friendly while also providing valuable benefits to society. These include promoting biodiversity, mitigating climate change impacts, restoring ecosystems, and enhancing amenities and resilience [

63]. Urban flooding has become a significant issue in most Chinese cities due to rapid urbanization and extreme weather events. The Chinese “Sponge City Program” (SCP), initiated in 2013 and adopted by 30 pilot cities, aims to manage urban flood risks, purify stormwater, and provide water storage opportunities for future use; they propose a holistic approach that combines ‘Blue–Green’ practices with traditional engineering to create integrated systems of Blue–Green–Grey infrastructure, which could enhance SCP practices by addressing a range of social and environmental challenges, including human health, pollution, flood risk, and biodiversity [

64].

An integrated approach driven by the Water Framework Directive (WFD) in Europe emphasizes understanding and managing catchments as systems. The authors of [

65] evaluated the role of NBSs in catchment management, using a case study of a privately funded wetland that improved effluent quality at a water recycling center and generated significant economic benefits through carbon sequestration and habitat provision. The findings confirm that when operated alongside traditional infrastructure, NBSs can enhance water management practices and attract private sector investment for environmental protection.

NBSs have been used for water management issues in agriculture, providing additional benefits such as biodiversity and climate adaptation. Treatment wetlands can remove excess nutrients from manure, and reed beds can treat sludge before land application, potentially creating valuable soil conditioners. Buffer strips and ponds effectively control diffuse pollution but require public investment or payments to farmers. Ponds designed for irrigation and biodiversity support may entail extra costs, requiring compensation. In-stream retention measures and ecosystem restoration projects, such as Lake Karla in Greece, also highlight the need for public support [

66].

NBSs are also increasingly used for sustainable urban water management. NBS implementation in Singapore and Lisbon shows that it can be effective across different contexts by addressing common drivers such as water supply, flood control, and demand for green spaces. Despite contextual differences, both cities shared goals such as improving water quality and quality of life. NBSs provided integrated benefits and improved city livability, addressing challenges from urban expansion, increased water use, and climate change impacts. The study highlights commonalities in NBS governance and implementation, suggesting that NBSs represent a versatile tool for enhancing urban resilience.

NBSs face several limitations, including the need for co-ordinated decision-making across multiple jurisdictions and sectors, which can lead to conflicts and inaction due to a lack of policy coherence. Trade-offs, such as compromising agricultural productivity for environmental benefits, further complicate implementation. Additionally, unsupportive or conflicting incentives and regulations, as well as entrenched institutional norms and path dependency, hinder the adoption of NBSs. Overcoming these challenges requires strong institutions, effective planning structures, and increased awareness of the benefits provided by NBSs [

67]. Financial barriers are also significant, with insufficient long-term funding and complex application processes deterring stakeholders. Furthermore, entrenched sociocultural norms favor traditional ‘grey’ infrastructure due to a prevailing ‘paradigm of growth’, where stakeholders prioritize investments that promise quantifiable economic benefits and expect to see economic growth. This perception undervalues the diverse benefits of NBSs and leads to reluctance to adopt these alternatives. There is a critical need for policies that promote improved participatory processes around NBSs to raise awareness, distribute benefits equitably, pre-empt conflicts, and foster stewardship [

68].

2.4. Socio-Hydrology

Socio-hydrology is a scientific discipline focused on understanding and interpreting the interactions and feedback between human and water systems. It aims to analyze the dynamics of socio-hydrologic processes, explain their impact on human well-being, and explore future scenarios. This field integrates the study of multiscale water system structures, human outcomes related to water, and societal goals for water use and sustainability. By formalizing these interactions, socio-hydrology seeks to address water sustainability challenges in the Anthropocene [

69]. The current popular approach in socio-hydrology is developing coupled human–water models. Mostert [

70] proposed an alternative: qualitative case study research involving systematic reviews of human activities, key actors, and influencing factors. It presented a case study of the Dommel Basin in Belgium and the Netherlands, comparing it with a coupled model of the Kissimmee Basin in Florida. Both show a shift from water resource development to protection. The Dommel study highlighted the importance of institutional and financial arrangements, community values, and broader developments, which are missing from the Kissimmee model. Case studies offer a more complete understanding of management levers, while coupled models generate quantitative scenarios. Scholars in socio-hydrology aim to capture the full range of human behavior in interaction with natural systems, but methodological implementations often reduce these dimensions to fit quantitative models, posing epistemological challenges. Human behavior is influenced by perceptions, preferences, and socio-political contexts, making it difficult to find a single truth [

71].

2.5. Hydro-Social Territories

Hydro-social territories are spaces where society, technology, and nature intersect, shaped by human imagination and social practices. They encompass interactions between water flows, hydraulic infrastructure, and governance structures, highlighting inclusion, exclusion, and the distribution of resources. These territories reflect the complex interplay of biophysical, technological, social, and political elements in water management [

72]. Hommes et al. [

73] examined the Foucauldian ‘arts of government’ used to manage water transfers from rural to urban areas in Lima, San Luis Potosí, and Bucaramanga and analyzed conventional water transfers and payment for ecosystem services schemes, revealing how urban imaginaries of rural areas influence governance. The study showed how these dynamics create specific rural–urban subjectivities and explores their acceptance, negotiation, or contestation. This analysis enhances understanding of rural–urban hydro-social territories and the role of technology in shaping rural identities. Hydrosocial territories face several limitations in their conceptual and practical applications. One major limitation is the dynamic and reciprocal shaping of the categories of ‘state’ and ‘local community’ through hydraulic and conservation projects, which complicates the representation and understanding of these actors. Negotiation and contestation processes alter the identities and perceptions of the actors involved, making it difficult to maintain consistent categories. Additionally, while powerful actors often dominate local communities, there is also potential for grassroots discourses to democratize water governance, which can lead to reconfigurations of actors, decision-making processes, and spatial scales [

74].

3. Bourdieu’s Framework

Pierre Bourdieu has been one of the most influential sociologists in history, and his theories continue to be extensively used across a wide range of fields to comprehend social dynamics and power relations. His ideas revolve around understanding the dynamics within social fields through the interplay of capital, field, and habitus. By combining anthropology, sociology, and philosophy, his approach focuses on how different forms of capital—economic, social, cultural, and symbolic—affect social interactions and power structures within distinct social spaces [

75]. Power is both the main interest of practice and the engine of field dynamics in Bourdieu’s theory. Bourdieu aligns all practices through the logic of domination [

76]. Bourdieu defines the field as an arena where conflict arises among actors seeking access to specific resources that define it; this structure is determined by the relationships between the involved actors [

77]. Each field is organized around specific problems and interests, motivating participants to invest in it. The ‘field’ encompasses two aspects: the social position of the actors, influenced by the number of different types of capital, as well as the symbolic positions or attitudes that these individuals adopt. Various forms of capital differ in value and distribution within fields, establishing a hierarchical structure with unequal relations among actors who may not have direct interaction. Dominant figures in the field can enforce both formal and informal rules, primary objectives, and entry criteria that reflect not only a power relationship but also an element of domination [

78]. Field theory is pertinent for understanding dominant figures but may be less applicable to those subordinate and peripheral actors who are not as significantly impacted by the influences and dynamics of the field.

Pierre Bourdieu’s sociological theory emphasizes the central role of capital concepts in understanding social dynamics and power distribution within different social fields. He classifies capital into four main forms: economic, social, cultural, and symbolic. Economic capital encompasses the financial and material resources owned by an individual or group, such as money, properties, and other assets that can be readily converted into cash. This type of capital can be quickly and directly changed into money and may also be formalized through property rights [

79]. Social capital refers to the resources that stem from belonging to a network or group of more or less institutionalized relationships characterized by mutual acquaintance and recognition. Members of this network have access to various benefits through their social connections. Social capital comprises social obligations (‘connections’), which, under specific conditions, can be converted into economic capital and could even be formalized as a title of nobility [

80]. Cultural capital can exist in three forms: embodied, as long-lasting dispositions of the mind and body; objectified, as cultural goods such as books, works of art, or scientific instruments; and institutionalized, in the form of educational qualifications. It is not transferred instantaneously but requires a process of acquisition that involves accumulating knowledge and skills over time [

80]. According to Pierre Bourdieu [

81], symbolic capital is a form of capital related to perception and recognition within a specific social field. It includes resources such as prestige, honor, and attention that an individual or group possesses due to their cultural, social, or economic capital. Such forms of capital influence how individuals are perceived and treated by others in society and can be utilized to gain additional advantages or maintain one’s social position. In each field, agents use these forms of capital to maintain or improve their position within the hierarchy. The relationship between the types of capital and the field is dynamic; agents can transform one type of capital into another depending on the conditions of the field and their abilities to maneuver within it. For example, a person can use their social capital (connections) to gain access to opportunities that increase their economic capital (wealth) or cultural capital (educational credentials).

Another important concept is habitus. Pierre Bourdieu defines it as the internalized and enduring dispositions that shape individuals’ perceptions, thoughts, and actions. These dispositions result from the inculcation of social and cultural structures and often operate unconsciously, guiding individuals in their everyday interactions across various fields [

82]. Thus, habitus not only reflects the social conditions of its production but also actively influences how individuals engage with and respond to those conditions. This interplay between structure and agency is central to understanding the reproduction and transformation of social structures within Bourdieu’s theory.

Bourdieu’s work emphasizes understanding how social positions, dispositions, and choices are relationally defined by individuals’ practices within a system. He argues that direct comparisons of isolated traits can misrepresent structural differences or similarities, so comparisons should be made across entire systems. The idea of ‘distinction’ refers to the relational properties that exist through connections to other properties rather than innate qualities [

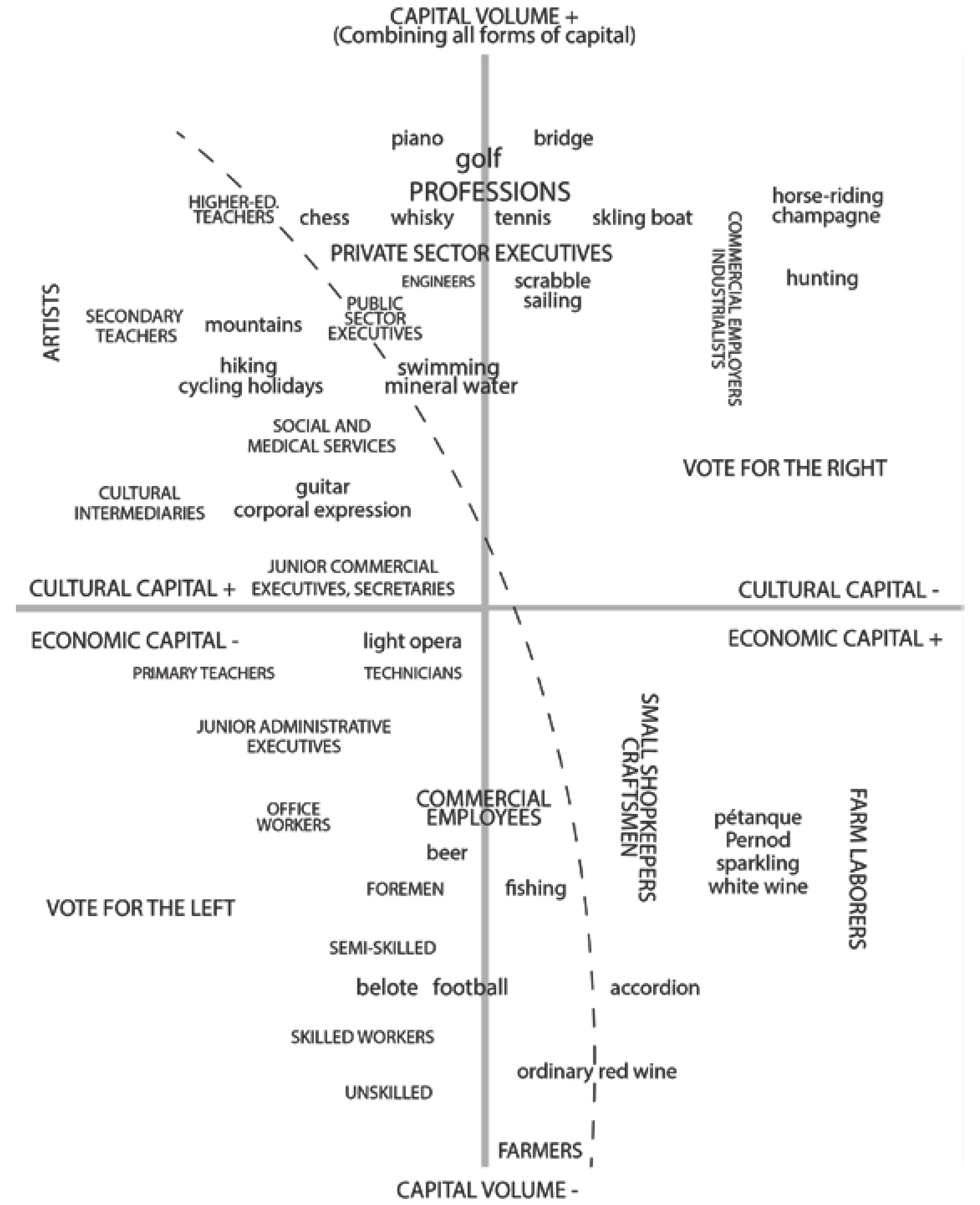

82]. This highlights the concept of social space, where positions are defined by their relations to others, reflecting proximity, distance, and hierarchy. The social space is organized so that agents or groups are distributed according to their positions in the statistical distributions of economic and cultural capital. Agents have more in common when they are closer in these dimensions. The distances on paper reflect social distances. In the main dimension, those with significant capital, such as entrepreneurs and professors, oppose those without, such as unskilled workers. The structure of capital, meaning the relative weight of economic and cultural capital, also creates opposition, such as between professors and entrepreneurs. These capital differences lead to variations in dispositions and positions, translating into different practices and goods, which form a coherent system of habitus according to the social class position (

Figure 1). Elaborating on the social space, which is an abstract reality that structures the practices and representations of social agents, enables the construction of theoretical classes based on the primary factors shaping social practices. This classification not only describes empirical realities but, akin to an effective taxonomic system, also forecasts other properties, clustering similar agents and distinguishing them from others.

4. Engineering Method

Engineering is often viewed with condescension, even among those who recognize the cultural importance of science and technology. This perspective reduces engineering to merely applied science, ignoring the distinct theoretical and epistemological frameworks that differentiate it from the physical sciences. While science seeks universal truths about the natural world, engineering operates within a context-specific, socially driven framework. As a result, engineering’s practice is more shaped by the social, political, and economic forces within which it operates than by the pure scientific knowledge it employs [

83]. Engineering is often treated in academic programs as a black box, a step in the technological innovation process, or a matter of technical problem-solving. However, Science and Technology Studies scholarship has generated a richer understanding of technological innovation as a complex social process. In order to fully appreciate engineering, it is important to understand how engineers enable this process of selective knowledge exploitation, which exemplifies a distinctive form of rationality compared to science [

84]. Engineering problems and solutions are inherently context-dependent. Engineers generate the knowledge needed to solve the problems they define by selectively appropriating scientific or other knowledge and transforming it into engineering knowledge. Engineering reasoning is highly complex, as it is inseparable from the particularities of intentionality, contingency, voluntariness, and value-laden contexts. This reasoning cannot be uncovered by applying a generic solution methodology; rather, it is through the explicit valuation and the specific process of defining engineering problems and developing solutions that the unique reasoning and method of engineering are manifested [

83,

84].

In the last century, engineers have commonly assumed that ‘design’, or more precisely, the ability to design, is the fundamental element linking engineering and technological development. Design is a human capacity that can manifest in physical objects, though it is distinct from the objects themselves. It involves adapting means to achieve some predetermined end. The ability to design demonstrates technological aptitude and successful creations by engineers. This necessitates combining numerous elements into a carefully crafted whole to accomplish a preconceived goal. At its core, design entails a structure or pattern and a particular arrangement of details or component parts [

85]. In other words, design shapes the way in which engineers reason about problems. This mode of thinking is fundamentally at odds with the notions of universality and context-free engineering concepts, which philosophers have promoted as the only valid approaches derived from validations through mathematics and modern physics. Additionally, design is inextricably linked to historical, sociocultural, and personal factors [

86].

The objectives of any engineering research project must be grounded in the generation of new knowledge. As previously established, this new knowledge takes the form of ‘know-how’, or more precisely, ‘know how to do something’. In this proposal, the novelty is inherently tied to a reconceived approach to water management. As will be evident in this paper, previously overlooked elements are incorporated, and engineering-driven technological tools are leveraged. The main aim is to enhance water management, with the new knowledge translating into a more effective and innovative way of addressing this task.

In the framework design, we use a process planning heuristic: “the use of heuristics to find the best solution in a poorly understood situation with available resources”[

87]. This introduces the concept of the state of the art, which refers to a set of heuristics. A heuristic is any approach that provides guidance in solving a problem and can be based on different states of the art. We use various heuristics as a basis to link the social and cultural elements in water management, resulting in a unified model that addresses population phenomena based on individual and institutional behaviors within a social field. The central idea is to incorporate the complexity of human behavior in the water management planning process. The engineering method is based on decision-making that guides the process toward a desired final state, using heuristics that engineers select according to their current knowledge and the context in which they operate. This process is dynamic and adaptive, recognizing that both the problem and available resources may change over time. Heuristics, as key elements of the method, not only direct the course of action but also reflect the limitations and possibilities of knowledge at any given moment. As the engineer progresses from an initial state to a final state, continuous evaluations are made to ensure that the chosen direction remains the most appropriate given the changing circumstances and new societal goals that may emerge. The notion of a ‘best’ engineering solution is inherently subjective, as it is shaped by the individual engineer’s knowledge, experience, and understanding of the current state of the art. This subjectivity is further compounded by the inherent uncertainty and incomplete information that characterize engineering problems. Consequently, the engineering methodology is closely tied to the subjective determination of the ‘best’ solution, which is influenced by personal and contextual considerations [

88].

We propose an approach to water management as a social field, positioning social dynamics, capital structure, and power distribution as the central consideration in the planning process. However, simply stating the habitus and capital as the core elements is insufficient. Rather, the framework must be able to meaningfully connect these with the relevant aspects of water management and provide a means to support planning efforts. Guided by the design principles of engineering, we put forward a framework that integrates the complete cycle of technological development. This framework is intended to facilitate water management by incorporating new elements employing a participatory approach to generate scenarios. Given the complexity of a social field, uncertainty is inherent in the conceptualization of these systems. There is a significant lack of information about the various elements present in the field, making it impossible to achieve complete knowledge. In order to address this challenge, a framework based on agent modeling can help improve the legitimacy of water management planning proposals. A key aspect of this approach is to avoid oversimplifications that overlook essential elements and instead strive to incorporate the inherent complexity of the field. The goal is to optimize water availability by considering fundamental societal well-being factors that have traditionally been neglected due to their complexity. This can be achieved through water management based on participatory modeling [

89,

90].

5. Water Management as a Social Field

By applying Bourdieu’s concept of the social field to water management, we seek to understand how diverse agents interact within a structured space defined by their access and control over various forms of capital. This social field is a dynamic arena where agents, including government, private companies, academic institutions, non-governmental organizations, and the population, navigate their positions based on their capital accumulation. The social field of water management is characterized by the distribution of different forms of capital among its agents.

Economic capital shapes water management practices and policies, as individuals, communities, and institutions can mobilize financial resources and assets to influence these domains. This form of capital impacts not only the infrastructure and technologies that are developed and deployed but also the power dynamics within water governance. Economic capital significantly shapes investment in water infrastructure, including dams, reservoirs, pipelines, and treatment plants. Wealthier communities or regions are more likely to access advanced water technologies and infrastructure, securing a more reliable and higher-quality water supply, which also heavily influences access to water resources, especially in areas with constrained or privatized water supplies. Affluent individuals and corporations can leverage their financial resources to acquire water rights, invest in private water infrastructure, or engage in legal battles to secure water access, frequently to the detriment of less affluent communities. This can result in policies and practices that prioritize the interests of the wealthy, potentially neglecting the needs and rights of economically disadvantaged populations. In summary, the perspective of Bourdieu’s theory suggests that economic capital is a significant force in shaping the distribution of water resources. Acknowledging the influence of economic capital is crucial to address the inequalities it may perpetuate and to formulate more equitable and sustainable strategies for water management.

Cultural capital in the water management social field could seem like scientific knowledge, referring to the understanding of hydrological systems, water management technologies, cultural knowledge, and the local customs, traditions, and practices related to water use and conservation, which can vary widely between local communities around the world. Perceptions encompass the beliefs and values associated with water, such as its perceived importance, respect for water bodies, and awareness of conservation needs. Education is the level of formal and informal education related to water management that individuals and institutions possess. Cultural capital is crucial for understanding the social dynamics of water management; it shapes how management strategies are adopted and the effectiveness of interventions. Recognizing and utilizing this cultural capital is vital for developing more inclusive and sustainable water policies that resonate with the target communities.

Social capital in water management, as viewed through Bourdieu’s theory, is a vital resource that enhances the capacity of individuals and communities to manage water resources effectively. It facilitates co-operation, information exchange, access to resources, and conflict resolution, all of which are essential for sustainable water management. Communities often rely on social capital to effectively manage their water resources. Strong social connections enable collective action, allowing residents to address water scarcity, maintain local infrastructure, and advocate for improved water services. Such collective efforts are particularly vital in rural or marginalized areas lacking formal institutional support. Effective water management is based on trust and mutual support within a network. In the context of water, trust among community members, between communities and authorities, or across different agents is crucial for successfully implementing water management strategies. This trust enables co-operation, minimizes conflicts over water use, and encourages compliance with agreed water management practices. Social capital can help resolve conflicts over water resources. In areas with water scarcity or competition, strong social ties can enable constructive dialogue and negotiation to find mutually agreeable solutions. Social capital can also reduce the risk of conflicts escalating and support long-term peace efforts in water-stressed regions.

Lastly, symbolic capital is a form of power that legitimizes certain actors, practices, and narratives within the field. It plays a crucial role in shaping how water resources are governed, how policies are formulated, and how different agents can assert their interests and values in the management of water. Recognizing the role of symbolic capital is essential for understanding the dynamics of power and influence in water management and for developing more inclusive and equitable approaches to governance.

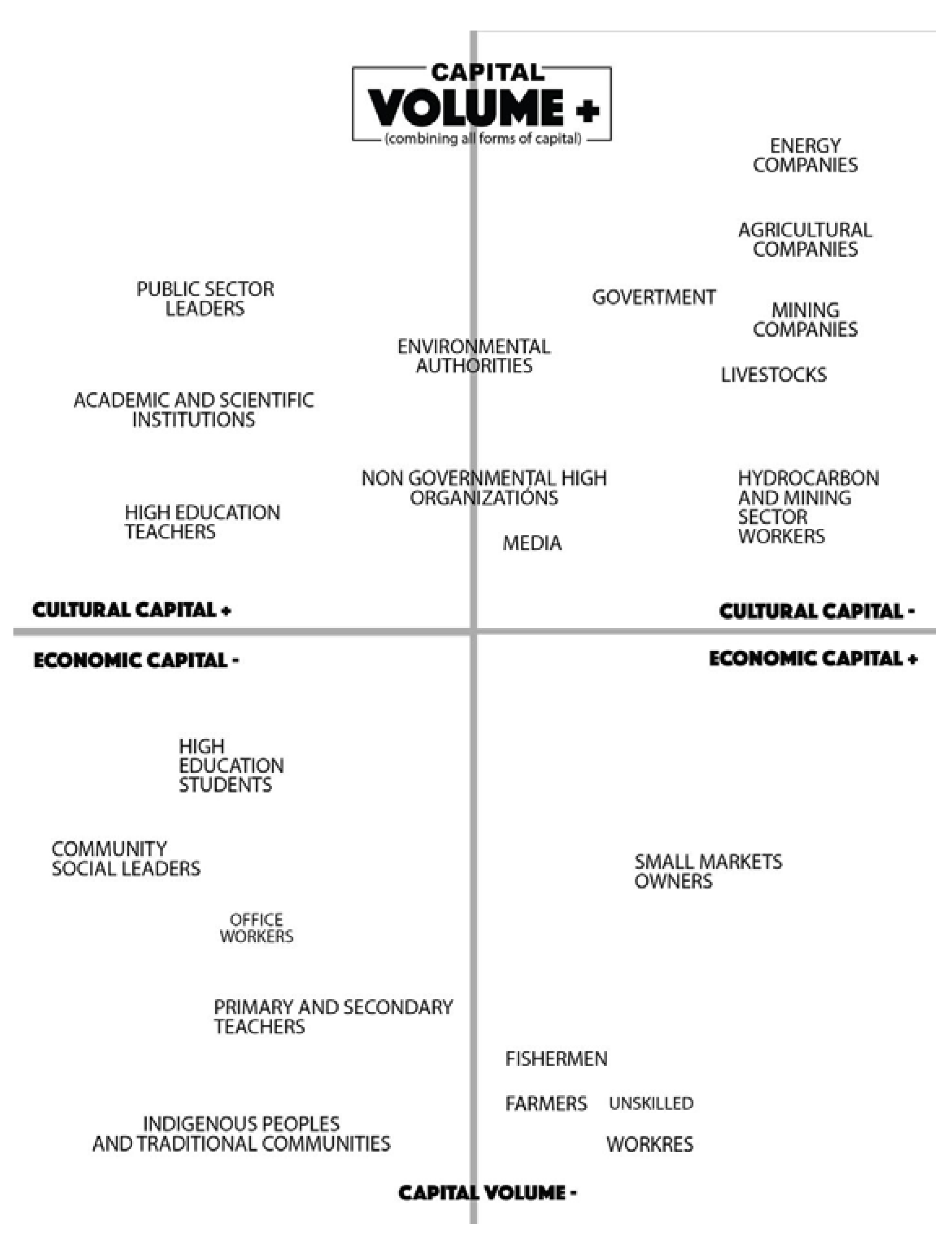

For this study, the social field of water management in Colombia was spatialized, mapping how various agents, from governmental institutions to local communities, interact and position themselves within this field based on their access to and control over different forms of capital. However, it is crucial to emphasize that this process of spatialization should be conducted for each specific area of study, as social, economic, and cultural dynamics vary significantly depending on the context. It is recommended that this spatialization be carried out at the most local level possible, considering the region’s habitus, as this ensures a more precise and relevant understanding of the interactions and power relations that influence water management. The study of the social aspects of water management in Colombia combined information from secondary sources and firsthand insights gathered from workshops and interviews with various stakeholders. This approach involved analyzing existing data and supplementing them with direct perspectives from key actors in water management. Integrating these diverse sources allowed for thorough mapping of the interactions and power dynamics within the social field, ensuring that the analysis accurately captures the complexities and nuances of water management in the Colombian context.

Figure 2 shows the agents of social positions involved in the social field of water management in Colombia.

Bourdieu’s theory offers a valuable framework for analyzing the social dynamics of water management, including how power and resources are distributed among different actors. Applying this approach to specific contexts, such as Colombia, can provide insights to inform more equitable and effective policies and strategies. However, it is crucial to adapt this methodology to other geographical and social settings to ensure the proposed solutions are relevant and sustainable for each situation.

6. Agent-Based Modeling of Social Fields

Agent-based modeling (ABM) is well suited for simulating complex social systems, as it can capture emergent phenomena from the interactions among individual agents. Unlike traditional top-down approaches, ABM allows for a bottom-up perspective where the global behavior of a system arises from the local interactions of its components. This is crucial for accurately representing inherently complex social systems characterized by nonlinear interactions, adaptation, and self-organization. The flexibility of ABM in modeling individual behavior, social interactions, and environmental influences makes it an ideal tool for exploring the dynamics of social fields and understanding the mechanisms that drive social change. Through ABM, researchers can simulate and analyze how individual actions aggregate to influence overall system dynamics, providing valuable insights that are difficult to achieve with more traditional modeling techniques [

91]. The reviewed literature highlights how ABM has bridged theoretical frameworks with practical scenarios, ranging from opinion dynamics to environmental management, disaster risk reduction, and economic decision-making [

92,

93,

94,

95,

96,

97,

98,

99,

100]. These studies collectively demonstrate the capacity of ABM to simulate intricate interactions within systems, providing a valuable tool for both predictive analysis and policy development. By connecting these findings to the broader discourse on social field modeling, this study establishes a foundation for integrating ABM with Bourdieu’s theoretical constructs, ultimately enhancing our understanding of social dynamics in water management. ABM has become increasingly important in water management research; the models have been integrated with traditional water distribution models to simulate the interactions between various agents, such as governing bodies, operational managers, and water consumers, under different stress scenarios such as climate change or infrastructure failures [

101,

102,

103]. This approach has proven effective in exploring the long-term impacts on system sustainability and resilience [

104]. Additionally, agent-based models have been used to understand public perceptions and behaviors regarding water reuse, revealing how factors such as market conditions, quality assessments, and environmental awareness shape decision-making within a community context [

105]. These models enable the more comprehensive analysis of water systems by incorporating the dynamic and often nonlinear interactions between social, economic, and environmental components, thereby offering valuable insights for policy development and system optimization. ABM has also been used to explore how Bourdieu’s concepts of social and cultural capital influence social dynamics in educational and institutional settings, simulating how individuals and groups interact within specific social fields. Henrickson (2002) [

106] analyzed how cultural and social capital affects college choice processes, demonstrating that these forms of capital can significantly impact outcomes in ways consistent with Bourdieu’s theory, gaining deeper insights into the mechanisms driving the reproduction or transformation of social inequalities.

ABM could be integrated with hydrological simulations to enhance water management strategies. These integrated models provide a more comprehensive understanding of how social factors, such as public awareness and expert influence, interact with hydrological processes such as groundwater flow and contaminant transport [

107,

108,

109]. This approach enables the development of more robust and adaptive water management strategies that account for both environmental and social complexities, leading to more sustainable and equitable outcomes. Integrating agent-based models with hydrological simulations provides a powerful approach to understanding the complex dynamics of water management. This integrated modeling framework offers insights into the intricate relationships between human behavior, water resource utilization, and environmental consequences.

In summary, an agent-based model based on Bourdieu’s theory can effectively integrate social dynamics, capital structures, and power distributions as central elements in water management research. This model leverages engineering heuristics to navigate the complex and context-dependent nature of social fields, ensuring that the generated solutions are tailored to the specific sociocultural and economic contexts. By incorporating Bourdieu’s concepts of habitus and capital, the methodology can address the intricacies of human behavior, social interactions, and power relations in water management. This approach aligns with the engineering emphasis on practical problem-solving and adaptive design while also enriching the planning process by considering the broader social implications and the dynamic nature of the social field. Overall, this method, which is rooted in the subjective determination of the ‘best’ solution, offers a robust tool for creating innovative and context-sensitive water management strategies that are better suited to the challenges of contemporary society.

7. Conclusions

This study examined how Pierre Bourdieu’s sociological theory on social fields, capital, and habitus can be applied to understand the dynamics of power and resource distribution among different actors in Colombia’s water management sector. By visualizing the social field, the analysis revealed how various agents, from government institutions to local communities, navigate their positions based on their access to economic, cultural, social, and symbolic forms of capital. Spatializing the analysis is essential to capture the unique socio-economic and cultural dynamics at play in a given area.

Integrating agent-based modeling into this approach further improves our ability to simulate and understand these complex social systems. This modeling technique enables a detailed exploration of how individual behaviors and interactions shape the broader dynamics of the social field. When combined with Bourdieu’s theoretical framework, agent-based modeling provides a powerful tool for developing more equitable and effective water management strategies tailored to the specific needs and conditions of each community.

Our analysis indicates that integrating Bourdieu’s sociological theory with engineering methods, emphasizing context-specific problem-solving and adaptive design, provides a robust approach to addressing contemporary water management challenges. By accounting for the complexities of human behavior, social interactions, and power dynamics in the planning process, this interdisciplinary model generates solutions that are technically sound and socially relevant, leading to more sustainable outcomes. This approach enables the development of innovative water management strategies tailored to the diverse and evolving needs of today’s society.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.D.L.-V. and M.G.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.D.L.-V. and M.G.-M.; writing—review and editing, M.G.-M.; visualization, M.A.D.L.-V.; supervision, M.G.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and the APC were funded by SERUANS ENVIRONMENT S.A.S. and Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author due to the fact that no new data were created given that this is review research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tao, Y.; Tao, Q.; Qiu, J.; Pueppke, S.G.; Gao, G.; Ou, W. Integrating Water Quantity- and Quality-Related Ecosystem Services into Water Scarcity Assessment: A Multi-Scenario Analysis in the Taihu Basin of China. Applied Geography 2023, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yang, X.; Wang, K.; Di, C.; Xiang, W.; Zhang, J. Exploring China’s Water Scarcity Incorporating Surface Water Quality and Multiple Existing Solutions. Environ Res 2024, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; Chen, A.; Zhao, D.; Mao, G.; Zhao, X.; Huang, H.; Liu, J. Impact of International Trade on Water Scarcity: An Assessment by Improving the Falkenmark Indicator. J Clean Prod 2023, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolahi, M.; Davary, K.; Omranian Khorasani, H. Integrated Approach to Water Resource Management in Mashhad Plain, Iran: Actor Analysis, Cognitive Mapping, and Roadmap Development. Sci Rep 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vichete, W.D.; Méllo Júnior, A.V.; Soares, G.A. dos S. A Water Allocation Model for Multiple Uses Based on a Proposed Hydro-Economic Method. Water (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echogdali, F.Z.; Boutaleb, S.; Abioui, M.; Aadraoui, M.; Bendarma, A.; Kpan, R.B.; Ikirri, M.; El Mekkaoui, M.; Essoussi, S.; El Ayady, H.; et al. Spatial Mapping of Groundwater Potentiality Applying Geometric Average and Fractal Models: A Sustainable Approach. Water (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Liu, Z. Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity of Urban and Rural Water Scarcity and Its Influencing Factors across the World. Ecol Indic 2023, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Addous, M.; Bdour, M.; Alnaief, M.; Rabaiah, S.; Schweimanns, N. Water Resources in Jordan: A Review of Current Challenges and Future Opportunities. Water (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Tabiee, M.; Karami, S.; Karimi, V.; Karamidehkordi, E. Climate Change and Water Scarcity Impacts on Sustainability in Semi-Arid Areas: Lessons from the South of Iran. Groundw Sustain Dev 2024, 24, 101075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardropper, C.; Brookfield, A. Decision-Support Systems for Water Management. J Hydrol (Amst) 2022, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudoin, L.; Arenas, D. From Raindrops to a Common Stream: Using the Social-Ecological Systems Framework for Research on Sustainable Water Management. Organ Environ 2020, 33, 126–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaro, L.L.B.; Abram, S.; Giatti, L.L.; Sinisgalli, P.; Jacobi, P.R. Assessing Water Scarcity Narratives in Brazil – Challenges for Urban Governance. Environ Dev 2023, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.J.; Kumar, P.; Chien, H.; Saito, O. Socio-Hydrological Approach for Water Resource Management and Human Well-Being in Pinglin District, Taiwan. Water (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Vega, R.K.; Algaba, E.; Sánchez-Soriano, J. Design of Water Quality Policies Based on Proportionality in Multi-Issue Problems with Crossed Claims. Eur J Oper Res 2023, 311, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, Y.; Zhou, F.; Zhao, J.; Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Ciais, P.; Chang, J.; Chen, L. Additional Surface-Water Deficit to Meet Global Universal Water Accessibility by 2030. J Clean Prod 2021, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Tu, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Gu, Y.; Yu, G. A Water Pricing Model for Urban Areas Based on Water Accessibility. J Environ Manage 2023, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandala, E.R.; McCarthy, M.I.; Brune, N. Water Security in Native American Communities of Nevada. Environ Sci Policy 2022, 136, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, E. Tropical Forests and Water Security in South America: Deforestation Trends, Drivers, and Solutions for Water Suppliers and Regulators. Imperiled: The Encyclopedia of Conservation: Volume 1-3 2022, 1–3, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenmark, M.; Wang-Erlandsson, L. A Water-Function-Based Framework for Understanding and Governing Water Resilience in the Anthropocene. One Earth 2021, 4, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, C.L.; Cortado, A.P.; Ünver, O. Stakeholder Engagement and Perceptions on Water Governance and Water Management in Azerbaijan. Water (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganoulis, J. Citation: Ganoulis, J. The Dialectics of Nature-Human Conflicts for Sustainable Water Security. The Dialectics of Nature-Human Conflicts for Sustainable Water Security. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chunga, B.A.; Graves, A.; Knox, J.W. Evaluating Barriers to Effective Rural Stakeholder Engagement in Catchment Management in Malawi. Environ Sci Policy 2023, 147, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, B.; Cushing, D.; Satherley, S.; Ozgun, K. Green Infrastructure in Water Management: Stakeholder Perceptions from South East Queensland, Australia. Cities 2023, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Yoon, J.H.; Yang, J.E.; Namkoong, S.; Kim, H. Stakeholder Analysis for Effective Implementation of Water Management System: Case of Groundwater Charge in South Korea. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, D.; Borg, M.; Hallett, S.H.; Sakrabani, R.S.; Thompson, A.; Papadimitriou, L.; Knox, J.W. Multi-Stakeholder Analysis to Improve Agricultural Water Management Policy and Practice in Malta. Agric Water Manag 2020, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, N.; Pushpalatha, R.; Manivasagam, V.S.; Arlikatti, S.; Cibin, R. Global Sustainable Water Management: A Systematic Qualitative Review. Water Resources Management 2023, 37, 5255–5272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delozier, J.L.; Burbach, M.E. Boundary Spanning: Its Role in Trust Development between Stakeholders in Integrated Water Resource Management. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poupeau, F.; O’Neill, B.F.; Muñoz, J.C.; Coeurdray, M.; Benites-Gambirazio, E. The Field of Water Policy: Power and Scarcity in the American Southwest; Taylor and Francis Inc., 2019; ISBN 9780429201394.

- Khan, H.F.; Arshad, S.A. Beyond Water Scarcity: Water (in)Security and Social Justice in Karachi. J Hydrol Reg Stud 2022, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro-Monzonís, M.; Solera, A.; Ferrer, J.; Estrela, T.; Paredes-Arquiola, J. A Review of Water Scarcity and Drought Indexes in Water Resources Planning and Management. J Hydrol (Amst) 2015, 527, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturla, G.; Ciulla, L.; Rocchi, B. Natural and Social Scarcity in Water Footprint: A Multiregional Input–Output Analysis for Italy. Ecol Indic 2023, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhim, T.; Richter, A.; Zhu, X. The Resilience of Social Norms of Cooperation under Resource Scarcity and Inequality — An Agent-Based Model on Sharing Water over Two Harvesting Seasons. Ecological Complexity 2019, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, I.; Kallis, G.; Aguilar, R.; Ruiz, V. Water Scarcity, Social Power and the Production of an Elite Suburb. The Political Ecology of Water in Matadepera, Catalonia. Ecological Economics 2011, 70, 1297–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlsson, L. Water Conflicts and Social Resource Scarcity. Phys. Chem. Earth (B) 2000, 25, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bréthaut, C.; Gallagher, L.; Dalton, J.; Allouche, J. Power Dynamics and Integration in the Water-Energy-Food Nexus: Learning Lessons for Transdisciplinary Research in Cambodia. Environ Sci Policy 2019, 94, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, J.; de Man, R. Powering Hydrodiplomacy: How a Broader Power Palette Can Deepen Our Understanding of Water Conflict Dynamics. Environ Sci Policy 2020, 114, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlwain, L.; Holzer, J.M.; Baird, J.; Baldwin, C.L. Power Research in Adaptive Water Governance and beyond: A Review. Ecology and Society 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, F. da S.; Soares, J.A.; Ribeiro, V.S. Conflicts over Water in Brazil. Sociedade & Natureza 2021, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helga, G.; Joost, D.; Paul, B.J.; Marijke, D. Power Relations in the Co-Creation of Water Policy in Bolivia: Beyond the Tyranny of Participation. Water Policy 2022, 24, 569–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlwain, L.; Baird, J.; Baldwin, C.; Pickering, G.; Manathunga, C. Structural Power Dynamics in Polycentric Water Governance Networks. Soc Nat Resour 2024, 37, 402–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudiatmaja, W.E. ; Yudithia; Samnuzulsari, T. In ; Suyito; Edison Social Capital of Local Communities in the Water Resources Management: An Insight from Kepulauan Riau. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; Institute of Physics Publishing, March 18 2020; Vol. 771. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, H.H.; Basu, M.; Sianipar, C.P.M.; Onitsuka, K.; Hoshino, S. Capital and Symbolic Power in Water Quality Governance: Stakeholder Dynamics in Managing Nonpoint Sources Pollution. J Environ Manage 2021, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P.; Delsaut, Y. Pour Une Sociologie de La Perception. Actes Rech Sci Soc 1981, 40, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gain, A.K.; Hossain, S.; Benson, D.; Di Baldassarre, G.; Giupponi, C.; Huq, N. Social-Ecological System Approaches for Water Resources Management. International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology 2021, 28, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Water Partnership. Integrated Water Resources Management; TAC BACKGROUND PAPERS 4, Ed.; Global Water Partnership: SE-10525 Stockholm, Sweden, 2000; ISBN 9163092298. [Google Scholar]

- Cardwell, H.E.; Cole, R.A.; Cartwright, L.A.; Martin, L.A. Integrated Water Resources Management: Definitions and Conceptual Musings. J Contemp Water Res Educ 2006, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ako, A.A.; Eyong, G.E.T.; Nkeng, G.E. Water Resources Management and Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) in Cameroon. Water Resources Management 2010, 24, 871–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngene, B.U.; Nwafor, C.O.; Bamigboye, G.O.; Ogbiye, A.S.; Ogundare, J.O.; Akpan, V.E. Assessment of Water Resources Development and Exploitation in Nigeria: A Review of Integrated Water Resources Management Approach. Heliyon 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katusiime, J.; Schütt, B. Integrated Water Resources Management Approaches to Improve Water Resources Governance. Water (Switzerland) 2020, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirwai, T.L.; Kanda, E.K.; Senzanje, A.; Busari, T.I. Water Resource Management: Iwrm Strategies for Improved Water Management. A Systematic Review of Case Studies of East, West and Southern Africa. PLoS One 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, V.C.; Garg, A.; Patil, J.P.; Thomas, T. Formulation of Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) Plan at District Level: A Case Study from Bundelkhand Region of India. Water Policy 2020, 22, 52–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Daoud, M.; El Mahrad, B.; Elhassnaoui, I.; Moumen, A.; Sayad, A.; ELbouhadioui, M.; Moroșanu, G.A.; Mezouary, L. El; Essahlaoui, A.; Eljaafari, S. Integrated Water Resources Management: An Indicator Framework for Water Management System Assessment in the R’Dom Sub-Basin, Morocco. Environmental Challenges 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luque-Villa, M.A.; González-Méndez, M. WATER MANAGEMENT IN COLOMBIA FROM THE SOCIO-ECOLOGICAL SYSTEMS FRAMEWORK. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment 2022, 259, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, V.S.; Mcdonald, G.T.; Mollinga, P.P. M: Review of Integrated Water Resources Management, 2009.

- Metz, F.; Glaus, A. Integrated Water Resources Management and Policy Integration: Lessons from 169 Years of Flood Policies in Switzerland. Water (Switzerland) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, H. Understanding the Nexus. T: Background Paper for the Bonn2011 Conference, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, G.B.; Jewitt, G.P.W. The Development of the Water-Energy-Food Nexus as a Framework for Achieving Resource Security: A Review. Front Environ Sci 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Campana, P.E.; Yao, T.; Zhang, Y.; Lundblad, A.; Melton, F.; Yan, J. The Water-Food-Energy Nexus Optimization Approach to Combat Agricultural Drought: A Case Study in the United States. Appl Energy 2018, 227, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, S.H.; Sharifi Moghadam, E.; Delavar, M.; Zarghami, M. Application of Water-Energy-Food Nexus Approach for Designating Optimal Agricultural Management Pattern at a Watershed Scale. Agric Water Manag 2020, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicaksono, A.; Jeong, G.; Kang, D. Water-Energy-Food Nexus Simulation: An Optimization Approach for Resource Security. Water (Switzerland) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, C.; Gitau, M.; Lara-Borrero, J.; Paredes-Cuervo, D. Framework for Water Management in the Food- Energy-water (FEW) Nexus in Mixed Land-use Watersheds in Colombia. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2020, 12, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwanto, A.; Sušnik, J.; Suryadi, F.X.; de Fraiture, C. Water-Energy-Food Nexus: Critical Review, Practical Applications, and Prospects for Future Research. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2021, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hogain, S.; McCarton, L. A Technology Portfolio of Nature Based Solutions: Innovations in Water Management; Springer, 2018; ISBN 9783319732817.

- Qi, Y.; Chan, F.K.S.; Thorne, C.; O’donnell, E.; Quagliolo, C.; Comino, E.; Pezzoli, A.; Li, L.; Griffiths, J.; Sang, Y.; et al. Addressing Challenges of Urban Water Management in Chinese Sponge Cities via Nature-Based Solutions. Water (Switzerland) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souliotis, I.; Voulvoulis, N. Operationalising Nature-Based Solutions for the Design of Water Management Interventions. Nature-Based Solutions 2022, 2, 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistocchi, A. 2022.

- Seddon, N.; Chausson, A.; Berry, P.; Girardin, C.A.J.; Smith, A.; Turner, B. Understanding the Value and Limits of Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change and Other Global Challenges. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2020, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryfisch, S.; Seeger, I.; McDonald, H.; Lago, M.; Blicharska, M. Opportunities and Limitations for Nature-Based Solutions in EU Policies – Assessed with a Focus on Ponds and Pondscapes. Land use policy 2023, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivapalan, M.; Konar, M.; Srinivasan, V.; Chhatre, A.; Wutich, A.; Scott, C.A.; Wescoat, J.L.; Rodríguez-Iturbe, I. Socio-hydrology: Use-inspired Water Sustainability Science for the Anthropocene. Earths Future 2014, 2, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostert, E. An Alternative Approach for Socio-Hydrology: Case Study Research. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 2018, 22, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesselink, A.; Kooy, M.; Warner, J. Socio-Hydrology and Hydrosocial Analysis: Toward Dialogues across Disciplines. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water.

- Boelens, R.; Hoogesteger, J.; Swyngedouw, E.; Vos, J.; Wester, P. Hydrosocial Territories: A Political Ecology Perspective. Water Int 2016, 41, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hommes, L.; Boelens, R.; Bleeker, S.; Duarte-Abadía, B.; Stoltenborg, D.; Vos, J. Water Governmentalities: The Shaping of Hydrosocial Territories, Water Transfers and Rural–Urban Subjects in Latin America. Environ Plan E Nat Space 2020, 3, 399–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaminio, S.; Rouillé-Kielo, G.; Le Visage, S. Waterscapes and Hydrosocial Territories: Thinking Space in Political Ecologies of Water. Progress in Environmental Geography 2022, 1, 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirone, M. Field, Capital, and Habitus: The Impact of Pierre Bourdieu on Bibliometrics. Quantitative Science Studies 2023, 4, 186–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedland, R. The Endless Fields of Pierre Bourdieu. Organization 2009, 16, 887–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Practical Reason On the Theory of Action; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, 1998; ISBN 9780804733632. [Google Scholar]

- Ancelovici, M. Bourdieu in Movement: Toward a Field Theory of Contentious Politics. Soc Mov Stud 2021, 20, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Poder, Derecho y Clases Sociales; 2nd, *!!! REPLACE !!!* (Eds.) ; Editorial Desclée de Brouwer. S.A: Bilbao, España, 2001; ISBN 8433014951.

- Bourdieu, P. The Forms of Capital. The Sociology of Economic Life 2018, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The Rules of Art : Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, 1996; ISBN 9780804725682. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Distinction A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste; Harvard University Press, 1984; ISBN 9780674212770.

- Goldman, S.L. Philosophy, Engineering, and Western Culture. Broad and Narrow Interpretations of Philosophy of Technology 1990, 125–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, S.L. Why We Need a Philosophy of Engineering: A Work in Progress. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 2004, 29, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layton, E.T. Science and Engineering Design. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1984, 424, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poel, I.; Goldberg, D. Philosophy and Engineering : An Emerging Agenda. In Philosophy and Engineering: An Emerging Agenda; Poel, I., Goldber, D., Eds.; Springer Dordrecht, 2010; p. 361 ISBN 978-94-007-3103-5.

- Koen, B.V. The Engineering Method and Its Implications for Scientific, Philosophical, and Universal Methods. Monist 2009, 92, 357–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koen, B.V. Discussion of the Method: Conducting the Engineer’s Approach to Problem Solving Available online:. Available online: https://books.google.hu/books/about/Discussion_of_the_Method.html?id=xLfTi2dpYTcC&redir_esc=y (accessed on 31 August 2024).

- Voinov, A.; Bousquet, F. Modelling with Stakeholders. Environmental Modelling and Software 2010, 25, 1268–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voinov, A.; Kolagani, N.; McCall, M.K.; Glynn, P.D.; Kragt, M.E.; Ostermann, F.O.; Pierce, S.A.; Ramu, P. Modelling with Stakeholders - Next Generation. Environmental Modelling and Software 2016, 77, 196–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remondino, M. Analysis of Agent Based Paradigms for Complex Social Systems Simulation, Universita di Torino, 2004.

- Nugent, A.; Gomes, S.N.; Wolfram, M.-T. Bridging the Gap between Agent Based Models and Continuous Opinion Dynamics. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammer-Kerwick, M.; Yundt-Pacheco, M.; Vashisht, N.; Takasaki, K.; Busch-Armendariz, N. A Framework to Develop Interventions to Address Labor Exploitation and Trafficking: Integration of Behavioral and Decision Science within a Case Study of Day Laborers. Societies 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Koliou, M. Assessing the Impact of Seismic Scenarios and Retrofits on Community Resilience Using Agent-Based Models. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2024, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flache, A. Between Monoculture and Cultural Polarization: Agent-Based Models of the Interplay of Social Influence and Cultural Diversity. J Archaeol Method Theory 2018, 25, 996–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzati, M.; Landoni, M. A Systematic Review of Agent-Based Modelling in the Circular Economy: Insights towards a General Model. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 2024, 69, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, M. A Moderate Role for Cognitive Models in Agent-Based Modeling of Cultural Change. Complex Adaptive Systems Modeling 2013, 1, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeton, A.; Xie, H.; Gwynne, S.; Hunt, A.; Thompson, P.; Köster, G. Agent-Based Models of Social Behaviour and Communication in Evacuations: A Systematic Review. Saf Sci 2024, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baier, K.; Mataré, V.; Liebenberg, M.; Lakemeyer, G. Towards Integrated Intentional Agent Simulation and Semantic Geodata Management in Complex Urban Systems Modeling. Comput Environ Urban Syst 2015, 51, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, A.J.; De Visscher, L.; Baetens, J.M.; De Baets, B. Quo Vadis, Agent-Based Modelling Tools? Environmental Modelling and Software 2022, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harik, G.; Alameddine, I.; Zurayk, R.; El-Fadel, M. An Integrated Socio-Economic Agent-Based Modeling Framework towards Assessing Farmers’ Decision Making under Water Scarcity and Varying Utility Functions. J Environ Manage 2023, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Hu, T.; Zeng, X.; Yang, P.; Wang, X. Exploring the Effects of Physical and Social Networks on Urban Water System’s Supply-Demand Dynamics through a Hybrid Agent-Based Modeling Framework. J Hydrol (Amst) 2023, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canales, M.; Castilla-Rho, J.; Rojas, R.; Vicuña, S.; Ball, J. Agent-Based Models of Groundwater Systems: A Review of an Emerging Approach to Simulate the Interactions between Groundwater and Society. Environmental Modelling and Software 2024, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormsbee, L.; Byrne, D.; Magliocca, N. The Need for Integrating Governance, Operations, and Social Dynamics into Water Supply/Distribution Modelling. In Proceedings of the The 3rd International Joint Conference on Water Distribution Systems Analysis & Computing and Control for the Water Industry (WDSA/CCWI 2024); MDPI: Basel Switzerland, August 29 2024; p. 12.

- Fu, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, M.; Hou, C. Modeling and Dynamic Simulation of the Public’s Intention to Reuse Recycled Water Based on Eye Movement Data. Water (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrickson, L. Old Wine in a New Wineskin: College Choice, College Access Using Agent-Based Modeling. Soc Sci Comput Rev 2002, 20, 400–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaxa-Rozen, M.; Kwakkel, J.H.; Bloemendal, M. A Coupled Simulation Architecture for Agent-Based/Geohydrological Modelling with NetLogo and MODFLOW. Environmental Modelling and Software 2019, 115, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakarji, J.; O’Malley, D.; Vesselinov, V. V. Agent-Based Socio-Hydrological Hybrid Modeling for Water Resource Management. Water Resources Management 2017, 31, 3881–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, J.; Gómez, J.A.; Ledezma, A. Testing the Feasibility of an Agent-Based Model for Hydrologic Flow Simulation. Information (Switzerland) 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).