Submitted:

18 January 2025

Posted:

21 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

I want to meaningfully average a pathalogical function (i.e., an everywhere surjective function whose graph has zero Hausdorff measure in its dimension). In case this impossible, we wish to average a nowhere continuous function defined on the rationals. We do this taking satisfying expected values of chosen sequences of bounded functions converging to f which are both equivalent and finite. As of now, I’m unable to solve this due to limited knowledge of advanced math and most people are too busy to help. Therefore, I’m wondering if anyone knows a research paper which solves my doubts. Unlike the previous paper, “Finding a Research Paper Which Meaningfully Averages Pathalogical Functions (V2)" [1] we modified the equations, the theorems, the approach to solving theorems in the blockquote, and the leading question which solves the blockquote. We also deleted unnecessary definitions to make the paper less complicated.

Keywords:

1. Intro

1.1. First Special Case of f

- (1)

- The function f is everywhere surjective [2] (i.e., function defined on a topological space where its’ restriction to any non-empty open subset is surjective).

- (2)

1.1.1. Potential Answer

Consider a Cantor set with Hausdorff dimension 0 [4]. Now consider a countable disjoint union such that each is the image of C by some affine map and every open set contains for some m. Such a countable collection can be obtained by e.g. at letting be contained in the biggest connected component of (with the center of being the middle point of the component).

Note that has Hausdorff dimension 0, so has Hausdorff dimension one [5].

Now, let such that is a bijection for all m (all of them can be constructed from a single bijection , which can be obtained without choice, although it may be ugly to define) and outside let g be defined by , where has a graph with Hausdorff dimension 2 [6] (this doesn’t require choice either).

Then the function g has a graph with Hausdorff dimension 2 and is everywhere surjective, but its graph has Lebesgue measure 0 because it is a graph (so it admits uncountably many disjoint vertical translates).

Note, we can make the construction with union of rather explicit as follows. Split the binary expansion of x as strings of size with a power of two, say becomes . If this sequence eventually contains only strings of the form or , say after , then send it to , where . Otherwise, send it to the explicit continuous function h given by the linked article [6]. This will give you something from

Finally, compose an explicit (reasonable) bijection from to . In your case, the construction can be easily adapted so that the or target space is actually , then compose with .

1.2. Second Special Case of f

1.3. Attempting to Analyze/Average f

- (1)

- The sequence of bounded functions is

- (2)

- The sequence of bounded functions converges to f: i.e.,

- (3)

- The generalized, satisfying extension of is : i.e., there exists a , where is finite

- (4)

-

There exists where the expected value of and are finite and non-equivelant: i.e.,(Whenever (4) is true, (3) is non-unique.)

1.3.1. Example Proving 1.3 (1)-(4) Correct

The integral counts the number of fractions with an even denominator and an odd numerator in set , after canceling all possible factors of 2 in the fraction. Let us consider the first case. We can write , where counts the fractions in that are not counted in , i.e., for which . This is the case when the denominator is odd after the cancellation of the factors of 2, i.e., when the numerator c has a number of factors of 2 greater than or equal to that of , which we will denote by a.k.a the 2-valuation of , [8]. That means, c must be a multiple of . The number of such c with is simply the length of that interval, equal to , divided by . Thus, . This obviously tends to zero, proving

Concerning the second case [7], it is again simpler to consider the complementary set of such that the denominator is odd when all possible factors of 2 are canceled. We can see that for , and these obviously include all those we had for smaller j. The “new" elements in with are those that have the denominator when written in lowest terms. Their number is equal to the number of , , which is given by Euler’s function. Since we also consider negative fractions, we have to multiply this by 2. Including , we have . There is no simple explicit expression for this (cf. oeis:A99957 [9]), but we know that [9]. On the other hand, the total number of all elements of is , since each time we increase j by 1, we have the additional fractions with the new denominator and the numerators are coprime with d, again with the sign + or −. From oeis:A002088 [10] we know that , so , which finally gives as desired.

1.3.2. Blockquote

We want the set of all Borel f, where satisfying expected values of chosen sequences of bounded functions converging to f (§5.1) are equivalent and finite, form:

- (1)

- a prevalent [11] subset of

- (2)

2. Extending the Expected Value w.r.t the Hausdorff Measure

- (1)

- One way is defining a generalized, satisfying extension of the Hausdorff measure on all A with positive & finite measure which takes positive, finite values for all Borel A. This can theoretically be done in the paper “A Multi-Fractal Formalism for New General Fractal Measures"[12] by taking the expected value of f w.r.t the extended Hausdorff measure.

- (2)

- Another way is finding a generalized, satisfying average of all A in the fractal setting. This can be done with the papers “Analogues of the Lebesgue Density Theorem for Fractal Sets of Reals and Integers" [13] and “Ratio Geometry, Rigidity and the Scenery Process for Hyperbolic Cantor Sets" [14] where we take the expected value of f w.r.t the densities in [13,14].

3. Attempt to Define “Unique and Satisfying" in The Blockquote of §1.3

3.1. Leading Question

If we make sure to:

- (A)

- Define C to be chosen center point of (e.g., the origin)

- (B)

- Define E to be the fixed, expected rate of expansion for all chosen sequences of each bounded functions’ graph (e.g., )

- (C)

- Define to be actual rates of expansion for each chosen sequence of each bounded functions’ graph ()

Does there exist a unique choice function which chooses a unique set of equivalent sequences of bounded functions where:

- (1)

- The chosen sequences of bounded functions converge to f (§5.1)

- (2)

- (3)

- The expected values, defined in the papers of §2, for all chosen sequences of bounded functions are equivalent and finite

- (4)

-

For the chosen sequences of bounded functions satisfying (1), (2) and (3), when f is unbounded (i.e, skip (4) when f is bounded):

- The absolute difference between the expected value of (3) and the -th coordinate of C is the less than or equal to that of all sequences of bounded functions satisfying (1), (2), and (3)

- (5)

-

When set is the set of all , where the choice function chooses all sequences of bounded functions satisfying (1), (2), (3) and (4), then Q is

- (a)

- a prevelant [11] subset of

- (b)

- (6)

- Out of all choice functions which satisfy (1), (2), (3), (4) and (5), we choose the one with the simplest form, meaning for each choice function fully expanded, we take the one with the fewest variables/numbers?

3.1.1. Explaining Motivation Behind 3.1

- (1)

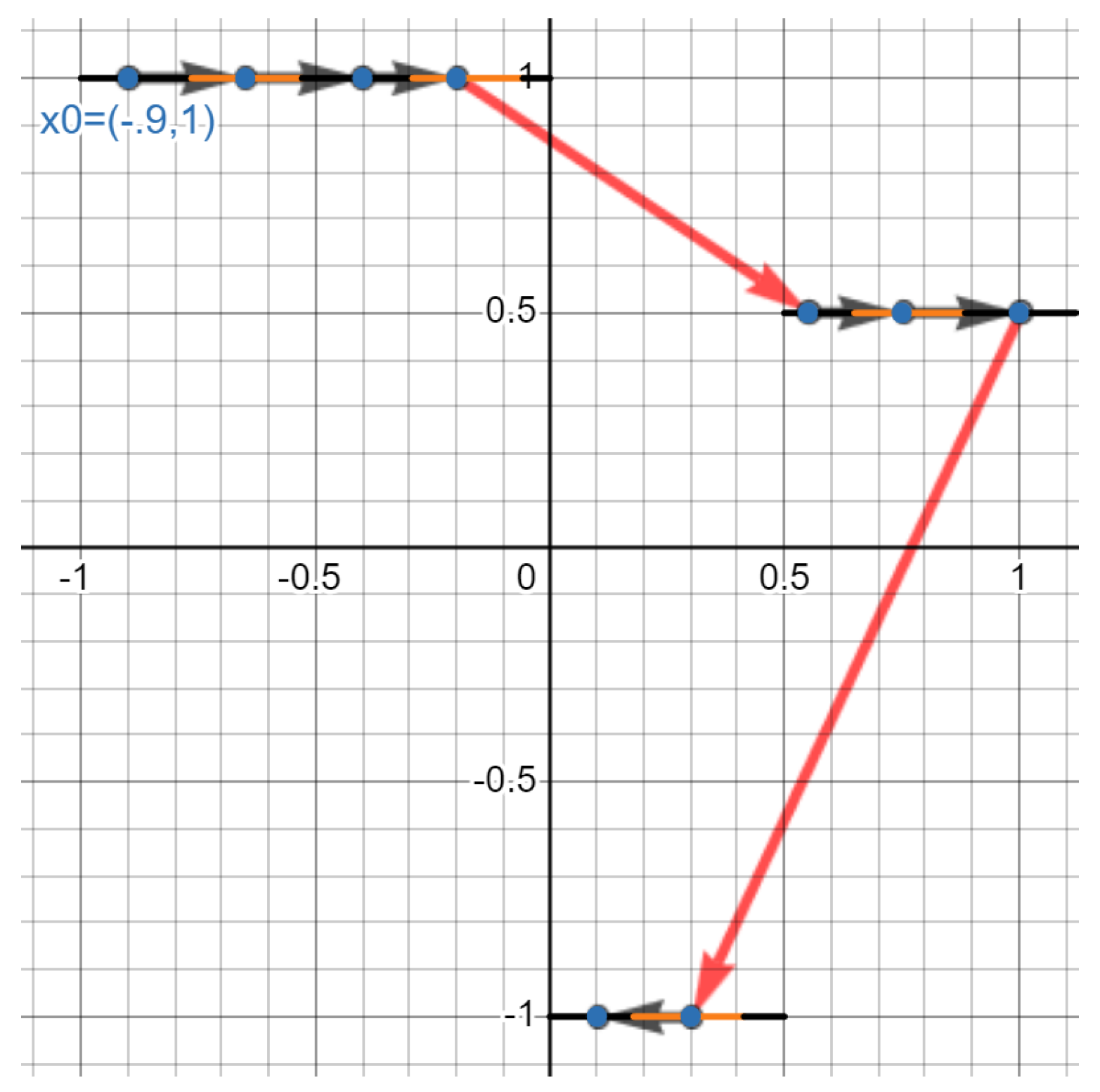

- When defining “the measure" (§5.3.1,§5.3.2) of a function, we want a bounded sequence of functions with a “high" entropic density (i.e., we aren’t sure if this is infact what the “measure" measures.) For example, when and f is everywhere surjective [2], the “measure" chooses bounded sequence of functions whose lines of symmetry intersect at one point rather than non-symmetrical functions §5.3.1-§6, §8.

- (2)

- (3)

- Using an unbounded function in §1.1 (i.e., an everywhere surjective f whose graph has zero Hausdorff measure in its dimension) depending on the sequence of bounded functionschosen which converge tof: can be any real number (when it exists). To fix this, take all , where the has smallest absolute difference from the -th coordinate of a reference point (i.e., the center point ). The problem is there exists f, where the expected value of sequences of bounded functions with non-equivalent expected values to that of the chosen sequence have the same minimum absolute difference from -th coordinate of C.

- (4)

- Thus, we take the sequence of functions whose actual rate of expansion from C (5.4) “diverges" [15, p.275-322] at the smallest rate from the expected, fixed rate of expansion E from C (i.e., the “rate of divergence of , using the absolute value , is less than or equal to that of all the non-equivalent sequences of bounded functions which satisfy §3.1 criteria (1), (2), and (3)).

- (5)

4. Question Regarding My Work

Is there a research paper which already solves the ideas I’m working on? (Non-published papers, such as mine [16], don’t count.)

5. Clarifying §3

Is there a simpler version of the definitions below?

5.1. Defining Sequences of Bounded Functions Converging to f

For any there exists a sequence s.t. and (see [19] for info).

- (1)

- (2)

- for

- (1)

- (2)

- for

5.2. Expected Value of Bounded Sequence of Functions

5.2.1. Example

- (1)

- (2)

- for

5.3. Defining the “Measure"

5.3.1. Preliminaries

- (1)

- For every , “over-cover" with minimal, pairwise disjoint sets of equal measure. (We denote the equal measures , where the former sentence is defined : i.e., enumerates all collections of these sets covering . In case this step is unclear, see §8.1.)

- (2)

- For every , r and , take a sample point from each set in . The set of these points is “the sample" which we define : i.e., enumerates all possible samples of . (If this is unclear, see §8.2.)

- (3)

-

For every , r, and ,

- (a)

- Take a “pathway” of line segments: we start with a line segment from arbitrary point of to the sample point with the smallest -dimensional Euclidean distance to (i.e., when more than one sample point has the smallest -dimensional Euclidean distance to , take either of those points). Next, repeat this process until the “pathway” intersects with every sample point once. (In case this is unclear, see §8.3.1.)

- (b)

- Take the set of the length of all segments in (a), except for lengths that are outliers (i.e., for any constant , the outliers are more than C times the interquartile range of the length of all line segments as ). Define this . (If this is unclear, see 8.3.2.)

- (c)

- Multiply remaining lengths in the pathway by a constant so they add up to one (i.e., a probability distribution). This will be denoted . (In case this is unclear, see §8.3.3)

- (d)

- (e)

-

Maximize the entropy w.r.t all "pathways". This we will denote:(In case this is unclear, see §8.3.5.)

- (4)

- Therefore, the maximum entropy, using (1) and (2) is:

5.3.2. What Am I Measuring?

- (a)

- (b)

- (a)

- or are equal to zero, one or

- (b)

- or are equal to zero, one or

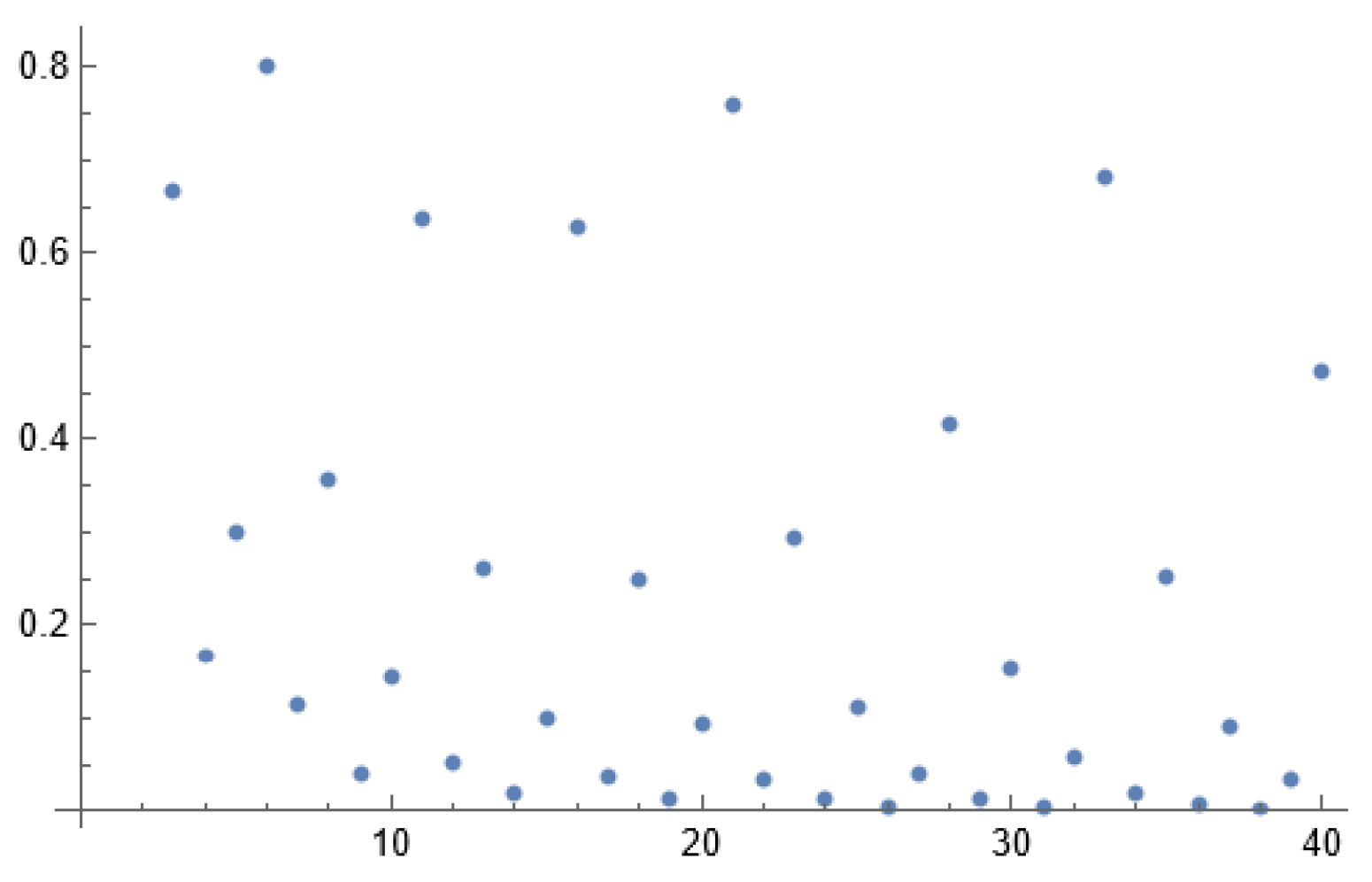

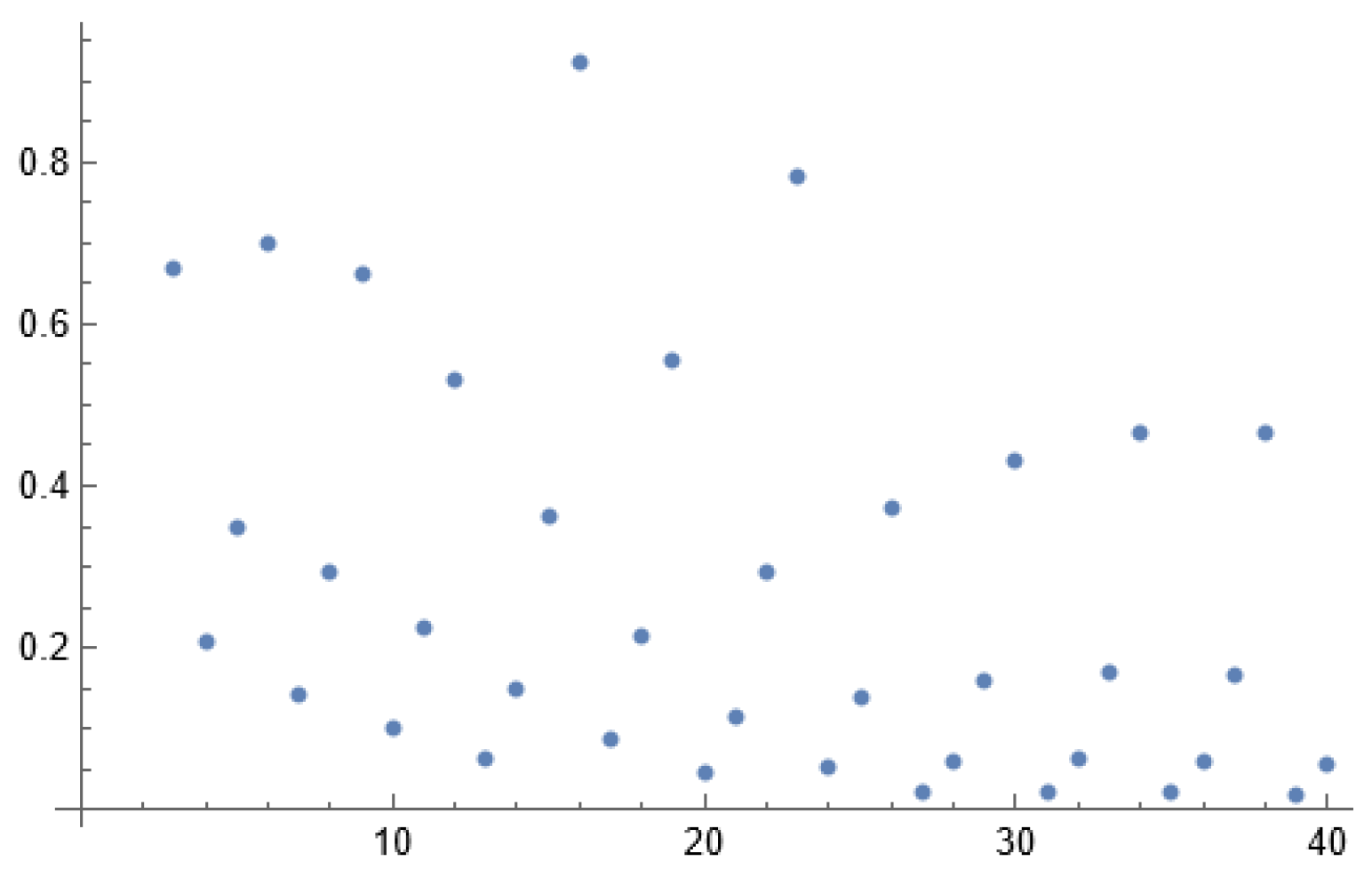

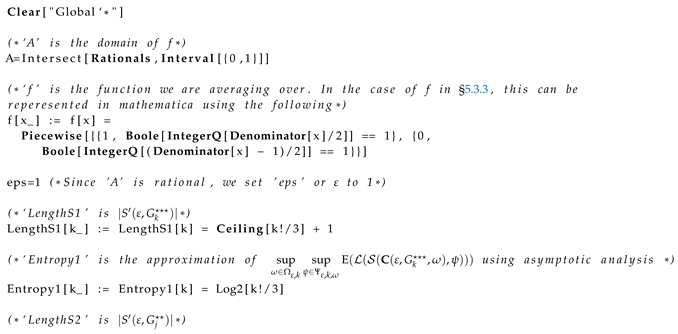

5.3.3. Example of The “Measure" of Increasing at Rate Super-Linear to That of

- (1)

- For every , group into elements with an even numerator when simplified: i.e.,which we call , and group into elements with an odd denominator when simplified: i.e.,which we call

- (2)

- Arrange the points in from least to greatest and take the 2-d Euclidean distance between each pair of consecutive points in . In this case, since all points lie on , take the absolute difference between the x-coordinates of then call this . (Note, this is similar to 5.3.1 step 3a).

- (3)

- Repeat step (2) for , then call this . (Note, all point of lie on .)

- (4)

- Remove any outliers from (i.e., d is the 2-d Euclidean distance between points and ). Note, in this case, and should be outliers (i.e., for any , the lengths of are more than C times the interquartile range of the lengths of ) leaving us with .

- (5)

- Multiply the remaining lengths in the pathway by a constant so they add up to one. (See P[r] of code 1 for an example)

- (6)

- Take the entropy of the probability distribution. (See entropy[r] of code 1 for an example.)

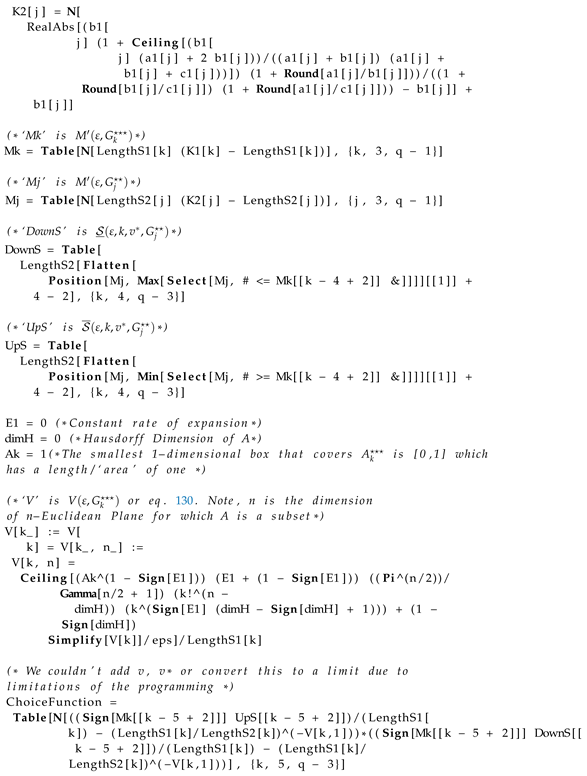

| Code 1: Illustration of step (1)-(6) |

|

| Code 2: Output of Table[{r,entropy[r]},{r,3,8}] |

|

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

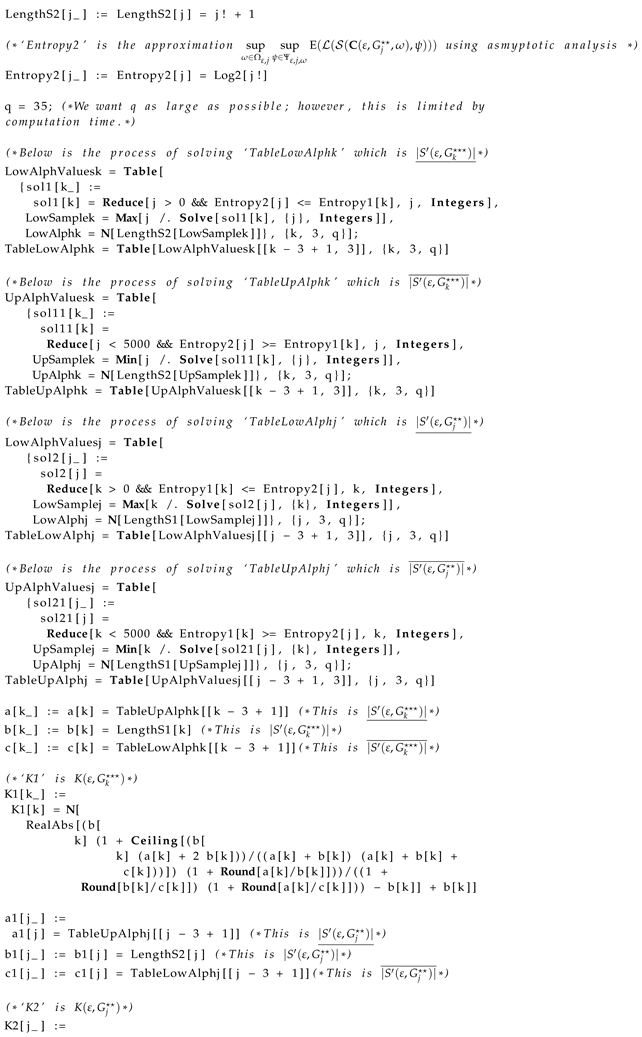

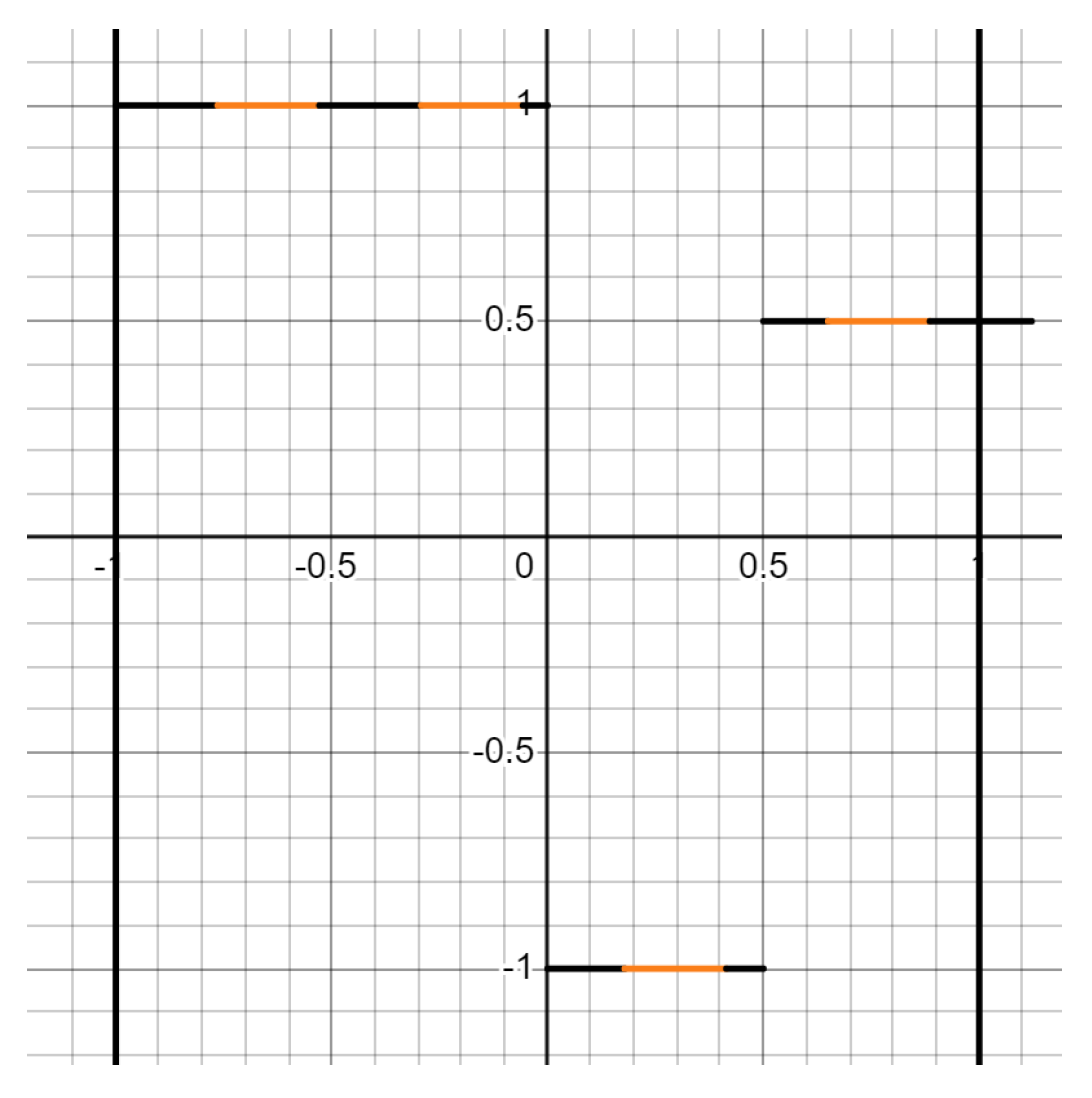

| Code 3: Illustration of step (1)-(6) on |

|

- (1)

- For every , we find a , where , but the absolute value of is minimized. In other words, for every , we want where:

| Code 4: Limitof eq. 59 |

|

- (1)

-

For every , we find a , where , but the absolute value of is minimized. In other words,for every , we want where:

| Code 5: Limitof eq. 69 |

|

5.3.4. Example of The “Measure" from Increasing at a Rate Sub-Linear to That of

5.3.5. Example of The “Measure" from Increasing at a Rate Linear to That of

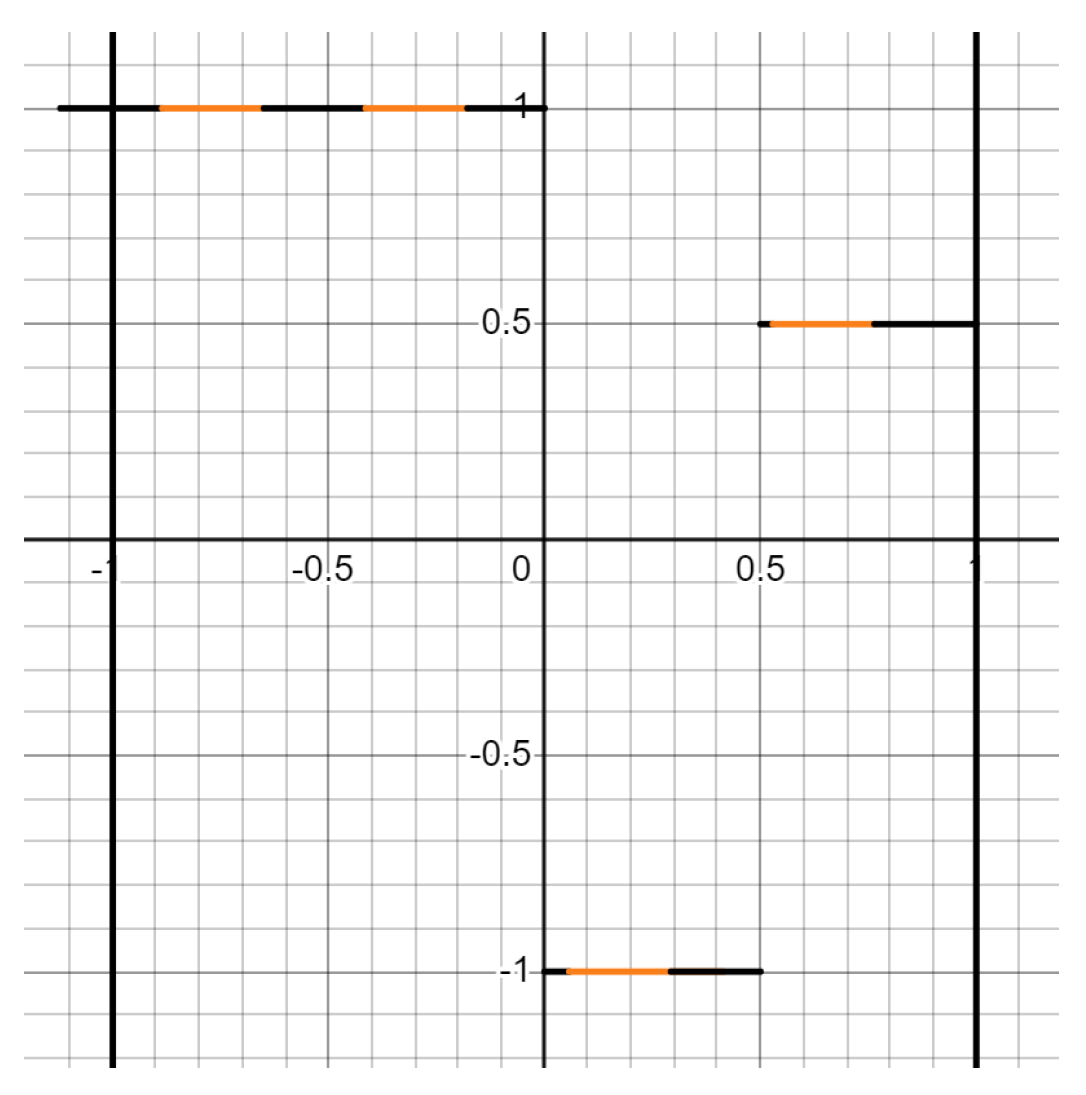

| Code 6: Illustration of step (1)-(6) on |

|

| Code 7: Output of Code 6 |

|

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

- (1)

- For every , we find a , where , but the absolute value of is minimized. In other words, for every , we want where:

| Code 8: Code for j in eq. 97 |

|

| Code 9: Output for code 8 |

|

- (1)

- For every , we find a , where , but the absolute value of is minimized. In other words, for every , we want where:

| Code 10: Code for r in eq. 104 |

|

| Code 11: Output for code 10 |

|

- (1)

- or are equal to zero, one or

- (2)

- or are equal to zero, one or

5.4. Defining the Actual Rate of Expansion of Sequence of Bounded Sets

5.4.1. Definition of Actual Rate of Expansion of Sequence of Bounded Sets

5.4.2. Example

5.5. Reminder

6. My Attempt at Answering the Blockquote of §1.3.2

6.1. Choice Function

- (1)

- is the sequence of bounded functions which satisfies (1), (2), (3), (4) and (5) of the leading question in 3.1

- (2)

- is all sequences of bounded functions satisfying (1) of the leading question where the expected values, defined in the papers of 2, is finite.

- (3)

- is an element but not an element in the set of sequences of bounded functions to that of which have equal expected values: i.e., . We represent this criteria as:

6.2. Approach

6.3. Potential Answer

6.3.1. Preliminaries (Definition of T in Case of §3.1.1 (5))

- (1)

- If , then

- (2)

- If , then

- (3)

- If , then

6.3.2. Question

6.4. Explaining the Choice Function and Evidence the Choice Function Is Credible

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

-

When c does exist, suppose:

- (a)

- When , then:

- (b)

- When , then:

Hence, for each sub-criteria under crit. (3), if we subtract one of their limits by their limit value, then eq. 131 and eq. is zero. (We do this using the “c"-term in eq. 131 and 132). However, when the exponents of the “c"-terms aren’t equal to , the limits of eq. 131 and 132 aren’t equal to zero. We want this, infact, whenever we swap with . Moreover, we define function (i.e., eq. 130), where: - (3)

- (i)

- (ii)

- When , then is zero which makes eq. 131 and 132 equal zero.

- (iii)

-

Here are some examples of the numerator of (eq. 130):

- A.

- When , , and , the numerator of is

- B.

- When , , and , the numerator of is

- C.

- When , , and , the numerator of is ceiling of constant times the volume of an n-dimensional ball with finite radius: i.e.,

- D.

- When , , and , the numerator of is ceiling of the volume of the n-dimensional ball: i.e.,

6.4.1. Evidence With Programming

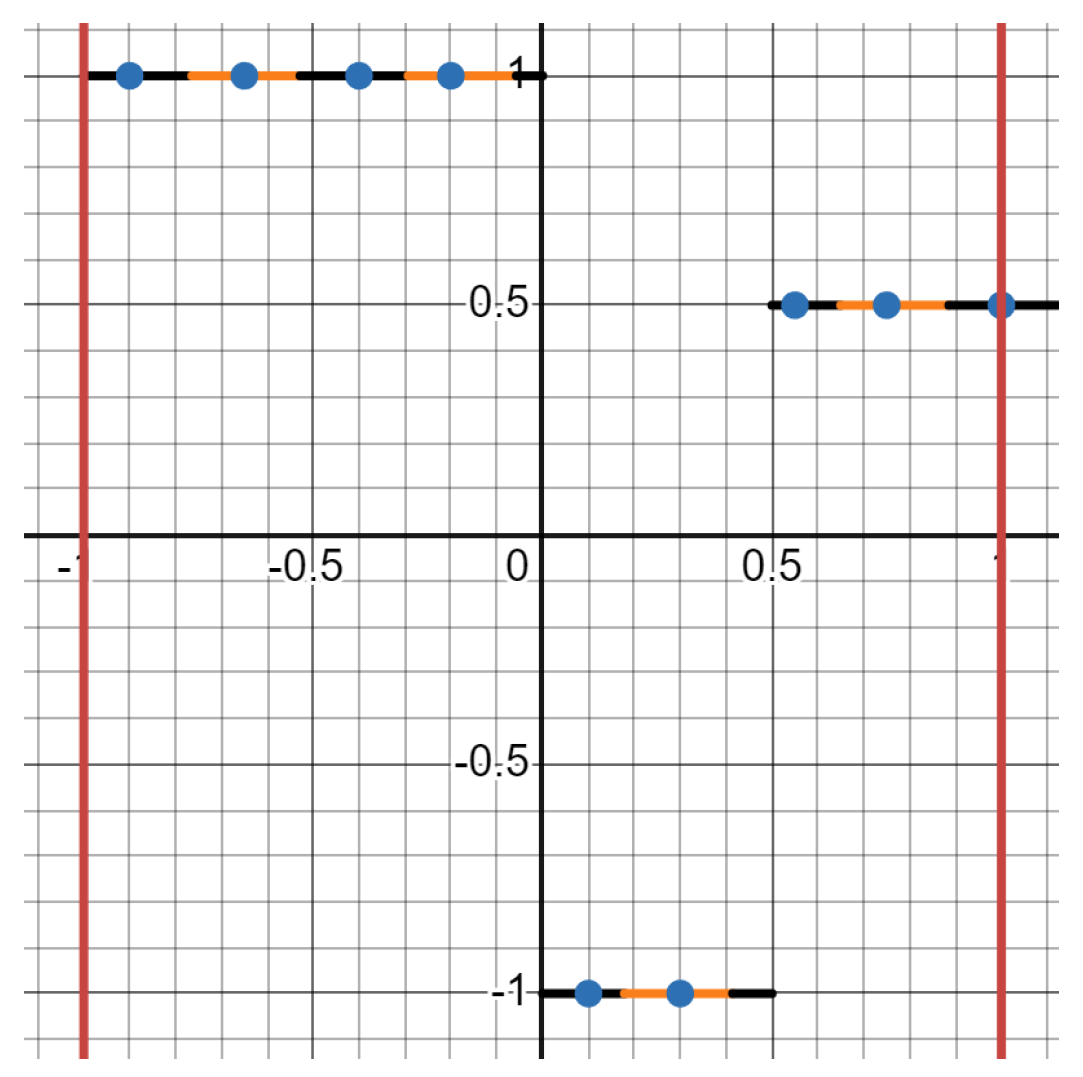

| Code 12: Code for eq. 131 and 132 to eq. 141 and eq. 142 |

|

7. Questions

- (1)

- Does 6 answer the in 3.1

- (2)

- Using thm. 6, when f is defined in 1.1, does have a finite value?

- (3)

- Using thm. 6, when f is defined in 1.2, does have a finite value?

- (4)

- If there’s no time to check questions 1, 2 and 3, see 4.

8. Appendix of §5.3.1

8.1. Example of §5.3.1, Step 1

- (1)

- (2)

- When defining :

- (3)

8.2. Example of §5.3.1, Step 2

8.3. Example of §5.3.1, Step 3

- (1)

- (2)

- When defining :

- (3)

- (4)

- (5)

- (6)

- , using eq. 150, is:

8.3.1. Step 3a

- (1)

- is the next point in the “pathway" since it’s a point in with the smallest 2-d Euclidean distance to instead of .

- (2)

- is the third point since it’s a point in with the smallest 2-d Euclidean distance to instead of and .

- (3)

- is the fourth point since it’s a point in with the smallest 2-d Euclidean distance to instead of , , and .

- (4)

- we continue this process, where the “pathway" of is:

8.3.2. Step 3b

8.3.3. Step 3c

8.3.4. Step 3d

8.3.5. Step 3e

References

- Krishnan, B. Finding a Published Paper Which Meaningfully Averages The Most Pathalogical Functions (V2), 2024. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/384467315_Finding_a_Published_Research_Paper_Which_Meaningfully_Averages_The_Most_Pathalogical_Functions_v2. [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, C.; Rainaldi, C. Everywhere surjections and related topics: Examples and counterexamples. Le Matematiche 2018, 73, 71–88. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325625887_Everywhere_surjections_and_related_topics_Examples_and_counterexamples.

- (https://mathoverflow.net/users/87856/arbuja), A. Is there an explicit, everywhere surjective f:R→R whose graph has zero Hausdorff measure in its dimension? MathOverflow, [https://mathoverflow.net/q/476471]. https://mathoverflow.net/q/476471.

- (https://math.stackexchange.com/users/413/jdh), J. Uncountable sets of Hausdorff dimension zero. Mathematics Stack Exchange, [https://math.stackexchange.com/q/73551]. https://math.stackexchange.com/q/73551.

- (https://mathoverflow.net/users/11009/pablo shmerkin), P.S. Hausdorff dimension of R x X. MathOverflow, [https://mathoverflow.net/q/189274]. https://mathoverflow.net/q/189274.

- Xie, T.; Zhou, S. On a class of fractal functions with graph Hausdorff dimension 2. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2007, 32, 1625–1630. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960077906000129. [CrossRef]

- MFH. Prove the following limits of a sequence of sets? Mathchmaticians, 2023. https://matchmaticians.com/questions/hinaeh.

- OEIS Foundation Inc.. A011371. The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences, 1999. https://oeis.org/A011371.

- OEIS Foundation Inc.. A099957. The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences, 2005. https://oeis.org/A099957.

- OEIS Foundation Inc.. A002088. The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences, 1991. https://oeis.org/A002088.

- Ott, W.; Yorke, J.A. Prevelance. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 2005, 42, 263–290. Available online: https://www.ams.org/journals/bull/2005-42-03/S0273-0979-05-01060-8/S0273-0979-05-01060-8.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Achour, R.; Li, Z.; Selmi, B.; Wang, T. A multifractal formalism for new general fractal measures. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2024, 181, 114655. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0960077924002066.

- Bedford, T.; Fisher, A.M. Analogues of the Lebesgue density theorem for fractal sets of reals and integers. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society 1992, 3, 95–124. Available online: https://www.ime.usp.br/~afisher/ps/Analogues.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Bedford, T.; Fisher, A.M. Ratio geometry, rigidity and the scenery process for hyperbolic Cantor sets. Ergodic Theory and Dynamical Systems 1997, 17, 531–564. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/math/9405217. [CrossRef]

- Sipser, M. Introduction to the Theory of Computation, 3 ed.; Cengage Learning, 2012; pp. 275–322.

- Krishnan, B. Bharath Krishnan’s ResearchGate Profile. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Bharath-Krishnan-4.

- Barański, K.; Gutman, Y.; Śpiewak, A. Prediction of dynamical systems from time-delayed measurements with self-intersections. Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées 2024, 186, 103–149. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0021782424000345. [CrossRef]

- Caetano, A.M.; Chandler-Wilde, S.N.; Gibbs, A.; Hewett, D.P.; Moiola, A. A Hausdorff-measure boundary element method for acoustic scattering by fractal screens. Numerische Mathematik 2024, 156, 463–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (https://math.stackexchange.com/users/5887/sbf), S. Convergence of functions with different domain. Mathematics Stack Exchange, [https://math.stackexchange.com/q/1063261]. https://math.stackexchange.com/q/1063261.

- M., G. Entropy and Information Theory, 2 ed.; Springer New York: New York [America];, 2011; pp. 61–95. https://ee.stanford.edu/~gray/it.pdf. [CrossRef]

- ydd. Finding the asymptotic rate of growth of a table of value? Mathematica Stack Exchange, [https://mathematica.stackexchange.com/a/307050/34171]. https://mathematica.stackexchange.com/a/307050/34171.

- ydd. How to find a closed form for this pattern (if it exists)? Mathematica Stack Exchange, [https://mathematica.stackexchange.com/a/306951/34171]. https://mathematica.stackexchange.com/a/306951/34171.

- John, R. Outlier. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Outlier.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).