Submitted:

04 September 2024

Posted:

09 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Physical Activity and Implications for General Health

1.2. Health Disparities Faced by Underrepresented Racial Minorities

1.3. Barriers and Facilitators to Physical Activity Among Underrepresented Racial Minorities

1.4. Using the Socio-Ecological Model to Identify Barriers and Facilitators to Physical Activity

1.5. Study Purpose

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

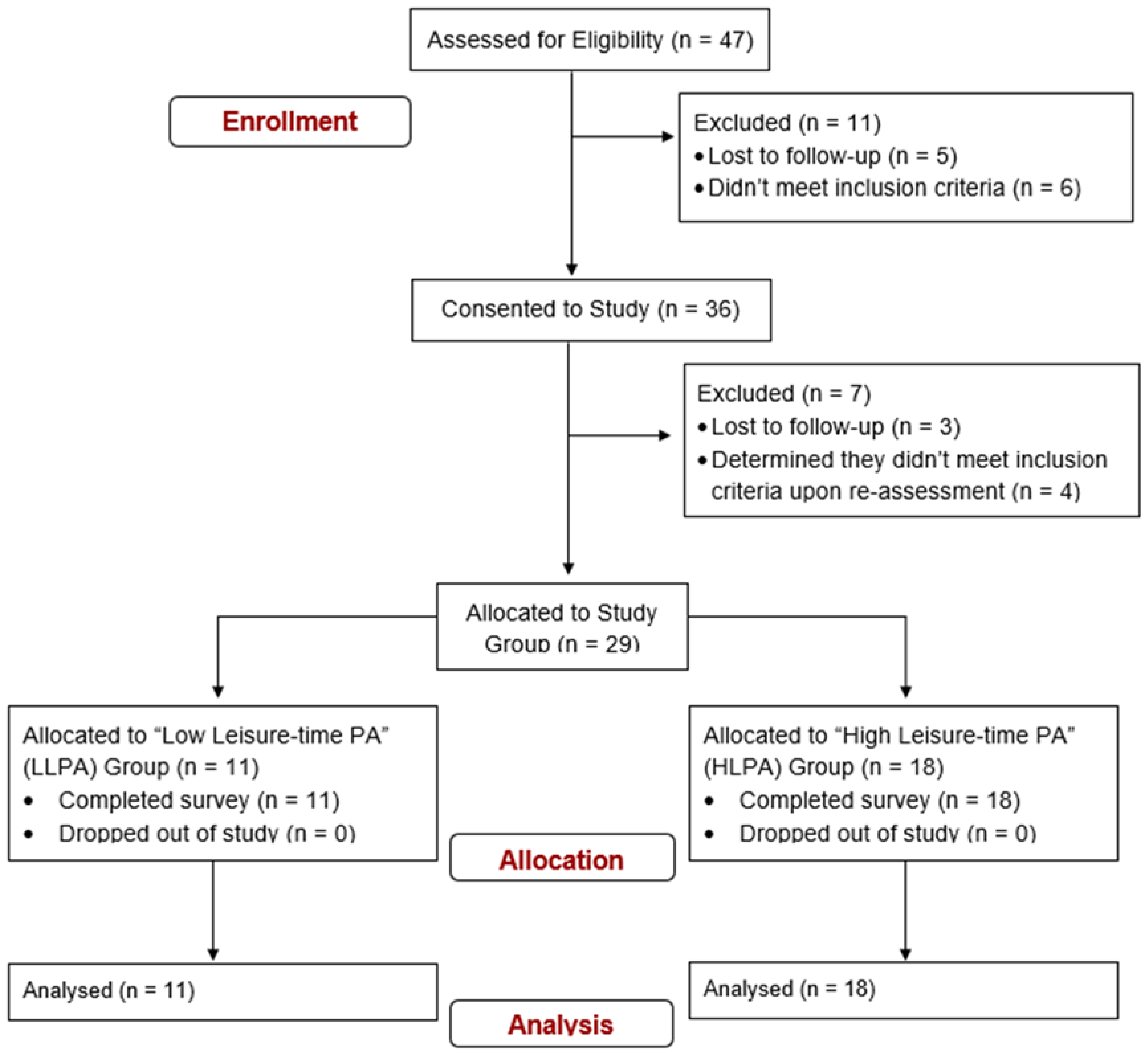

2.2. Participant Recruitment and Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Survey

2.3.1. International Physical Activity Questionnaire

2.3.2. Barrier Analysis Survey

2.3.3. Physical Activity Barrier Questionnaire

2.3.4. Exercise Identity Scale

2.3.5. Physical Activity & Social Support Scale

2.3.6. Self-Report Behavioral Automaticity Index

2.4. Participant Demographics

2.5. Determination of Study Groups

2.6. Data Analysis

2.6.1. Sample Size

2.6.2. Quantitative Data Analysis

2.6.3. Qualitative Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Missing Data Analysis

3.2. Self-Reported Physical Activity

3.3. Quantitative Survey Results

3.4. Qualitative Survey Results

3.4.1. Personal Level Barriers

3.4.2. Personal Level Facilitators

3.4.3. Interpersonal Level Facilitators

3.4.4. Community and Societal Level Barriers

3.4.5. Community and Societal Level Facilitators

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caspersen, C.J.; Powell, K.E.; Christenson, G.M. Physical Activity, Exercise, and Physical Fitness: Definitions and Distinctions for Health-Related Research. Public Health Rep 1985, 100, 126–131.

- World Health Organization WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2020; ISBN 978-92-4-001512-8.

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans; 2nd ed.; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington DC, 2018;

- Warburton, D.E.R.; Bredin, S.S.D. Health Benefits of Physical Activity: A Systematic Review of Current Systematic Reviews. Current Opinion in Cardiology 2017, 32, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M.S.; Patterson, C.A.; Walsh, S.M.; Bernhart, J.A. A Five-Year Evaluation of the Bearfit Worksite Physical Activity Program. Occupational Medicine & Health Affairs 2017. [CrossRef]

- Seo, B.; Nan, H.; Monahan, P.O.; Duszynski, T.J.; Thompson, W.R.; Zollinger, T.W.; Han, J. Association between US Residents’ Health Behavior and Good Health Status at the City Level. Translational Journal of the American College of Sports Medicine 2024, 9, e000258. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Adult Physical Inactivity Outside of Work; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022;

- Elgaddal, N.; Kramarow, E.A.; Reuben, C. Physical Activity Among Adults Aged 18 and Over: United States, 2020; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, 2022;

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC Releases Updated Maps of America’s High Levels of Inactivity; Center for Disease Control, 2022;

- World Health Organization Physical Inactivity Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/3416 (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Glynn, L.; Hayes, P.S.; Casey, M.; Glynn, F.; Alvarez-Iglesias, A.; Newell, J.; ÓLaighin, G.; Heaney, D.; O’Donnell, M.; Murphy, A.W. Effectiveness of a Smartphone Application to Promote Physical Activity in Primary Care: The SMART MOVE Randomised Controlled Trial. British Journal of General Practice 2014. [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.-M.; Shiroma, E.J.; Lobelo, F.; Puska, P.; Blair, S.N.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. Effect of Physical Inactivity on Major Non-Communicable Diseases Worldwide: An Analysis of Burden of Disease and Life Expectancy. The Lancet 2012. [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.E.; Reis, R.S.; Sallis, J.F.; Wells, J.C.; Loos, R.J.F.; Martin, B.W.; Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group Correlates of Physical Activity: Why Are Some People Physically Active and Others Not? Lancet 2012, 380, 258–271. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.html (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Sohn, E.K.; Porch, T.; Hill, S.; Thorpe, R.J. Geography, Race/Ethnicity, and Physical Activity among Men in the United States. American Journal of Men S Health 2017. [CrossRef]

- Healthy People 2030; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Social Determinants of Health Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- World Health Organization A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health. 2010, 76.

- Brownson, R.C.; Baker, E.A.; Housemann, R.A.; Brennan, L.K.; Bacak, S.J. Environmental and Policy Determinants of Physical Activity in the United States. Am J Public Health 2001, 91, 1995–2003. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 Hospitalization and Death by Race/Ethnicity - 2022 Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Braveman, P.A.; Cubbin, C.; Egerter, S.; Williams, D.R.; Pamuk, E. Socioeconomic Disparities in Health in the United States: What the Patterns Tell Us. Am J Public Health 2010, 100, S186–S196. [CrossRef]

- GBD US Health Disparities Collaborators Cause-Specific Mortality by County, Race, and Ethnicity in the USA, 2000–19: A Systematic Analysis of Health Disparities. The Lancet 2023, 402, 1065–1082. [CrossRef]

- Teitler, J.; Wood, B.M.; Zeng, W.; Martinson, M.L.; Plaza, R.; Reichman, N.E. Racial-Ethnic Inequality in Cardiovascular Health in the United States: Does It Mirror Socioeconomic Inequality? Annals of Epidemiology 2021, 62, 84–91. [CrossRef]

- Seyedrezaei, M.; Becerik-Gerber, B.; Awada, M.; Contreras, S.; Boeing, G. Equity in the Built Environment: A Systematic Review. Building and Environment 2023, 245, 110827. [CrossRef]

- Althoff, T.; Sosič, R.; Hicks, J.L.; King, A.C.; Delp, S.L.; Leskovec, J. Large-Scale Physical Activity Data Reveal Worldwide Activity Inequality. Nature 2017, 547, 336–339. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, A.; Aguilar, R.; Merck, A.; Sukumaran, P.; Gamse, C. The State of Latino Housing, Transportation, and Green Space: A Research Review; Robert Woods Johnson Foundation, 2019; p. 39;

- Saelens, B.E.; Sallis, J.F.; Frank, L.D. Environmental Correlates of Walking and Cycling: Findings from the Transportation, Urban Design, and Planning Literatures. ann. behav. med. 2003, 25, 80–91. [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.J.; Nicholson, L.; Chriqui, J.; Turner, L.; Chaloupka, F. The Impact of State Laws and District Policies on Physical Education and Recess Practices in a Nationally-Representative Sample of U.S. Public Elementary Schools. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2012, 166, 311–316. [CrossRef]

- Alamilla, R.A.; Keith, N.R.; Hasson, R.E.; Welk, G.J.; Riebe, D.; Wilcox, S.; Pate, R.R. Future Directions for Transforming Kinesiology Implementation Science into Society. Kinesiology Review 2023, 12, 98–106. [CrossRef]

- Hawes, A.; Smith, G.; McGinty, E.; Bell, C.; Bower, K.; LaVeist, T.; Gaskin, D.; Thorpe, R. Disentangling Race, Poverty, and Place in Disparities in Physical Activity. IJERPH 2019, 16, 1193. [CrossRef]

- Adamovich, T.; Watson, R.; Murdoch, S.; Giovino, L.; Kulkarni, S.; Luchak, M.; Smith-Turchyn, J. Barriers and Facilitators to Physical Activity Participation for Child, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. J Cancer Surviv 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y.; Wang, Q.; Ding, Y.; Zhao, W.; Jia, Z.; Wang, B. Barriers and Facilitators to Physical Activity Participation in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer: A Scoping Review. Support Care Cancer 2022, 30, 4591–4601. [CrossRef]

- Sattar, S.; Haase, K.R.; Bradley, C.; Papadopoulos, E.; Kuster, S.; Santa Mina, D.; Tippe, M.; Kaur, A.; Campbell, D.; Joshua, A.M.; et al. Barriers and Facilitators Related to Undertaking Physical Activities among Men with Prostate Cancer: A Scoping Review. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2021, 24, 1007–1027. [CrossRef]

- O’Neal, L.J.; Scarton, L.; Dhar, B. Group Social Support Facilitates Adoption of Healthier Behaviors among Black Women in a Community-Initiated National Diabetes Prevention Program. Health Promotion Practice 2022, 23, 916–919. [CrossRef]

- Vilafranca Cartagena, M.; Tort-Nasarre, G.; Rubinat Arnaldo, E. Barriers and Facilitators for Physical Activity in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Scoping Review. IJERPH 2021, 18, 5359. [CrossRef]

- Nikolajsen, H.; Sandal, L.F.; Juhl, C.B.; Troelsen, J.; Juul-Kristensen, B. Barriers to, and Facilitators of, Exercising in Fitness Centres among Adults with and without Physical Disabilities: A Scoping Review. IJERPH 2021, 18, 7341. [CrossRef]

- Hesketh, K.R.; Lakshman, R.; van Sluijs, E.M.F. Barriers and Facilitators to Young Children’s Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Qualitative Literature. Obes Rev 2017, 18, 987–1017. [CrossRef]

- Nally, S.; Ridgers, N.D.; Gallagher, A.M.; Murphy, M.H.; Salmon, J.; Carlin, A. “When You Move You Have Fun”: Perceived Barriers, and Facilitators of Physical Activity from a Child’s Perspective. Front Sports Act Living 2022, 4, 789259. [CrossRef]

- Poobalan, A.S.; Aucott, L.; Clarke, A.; Smith, W.C.S. Physical Activity Attitudes, Intentions and Behaviour among 18-25 Year Olds: A Mixed Method Study. BMC Public Health 2012. [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Ng, J.Y.Y.; Ha, A.S. Barriers and Facilitators to Physical Activity for Young Adult Women: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Literature. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2023, 20, 23. [CrossRef]

- Crombie, I.K.; Irvine, L.; Williams, B.; McGinnis, A.R.; Slane, P.W.; Alder, E.M.; McMurdo, M.E.T. Why Older People Do Not Participate in Leisure Time Physical Activity: A Survey of Activity Levels, Beliefs and Deterrents. Age Ageing 2004, 33, 287–292. [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.R.; Tong, A.; Howard, K.; Sherrington, C.; Ferreira, P.H.; Pinto, R.Z.; Ferreira, M.L. Older People’s Perspectives on Participation in Physical Activity: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Literature. Br J Sports Med 2015, 49, 1268–1276. [CrossRef]

- Wingood, M.; Peters, D.M.; Gell, N.M.; Brach, J.S.; Bean, J.F. Physical Activity and Physical Activity Participation Barriers among Adults 50 Years and Older during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2022, 101, 809–815. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans Midcourse Report: Implementation Strategies for Older Adults; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington DC, 2023;

- Larsen, B.A.; Noble, M.; Murray, K.; Marcus, B.H. Physical Activity in Latino Men and Women Facilitators, Barriers, and Interventions. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine 2015, 9, 4–30. [CrossRef]

- Larsen, B.A.; Pekmezi, D.; Marquez, B.; Benitez, T.J.; Marcus, B.H. Physical Activity in Latinas: Social and Environmental Influences. Womens Health (Lond Engl) 2013, 9, 10.2217/whe.13.9. [CrossRef]

- Amesty, S. Barriers to Physical Activity in the Hispanic Community. Journal of Public Health Policy 2003. [CrossRef]

- Payán, D.D.; Sloane, D.C.; Illum, J.; Lewis, L.B. Intrapersonal and Environmental Barriers to Physical Activity among Blacks and Latinos. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 2019, 51, 478–485. [CrossRef]

- Marquez, D.X.; Aguiñaga, S.; Campa, J.; Pinsker, E.C.; Bustamante, E.E.; Hernandez, R. A Qualitative Exploration of Factors Associated with Walking and Physical Activity in Community-Dwelling Older Latino Adults. J Appl Gerontol 2016, 35, 664–677. [CrossRef]

- Williams, W.M.; Yore, M.M.; Whitt-Glover, M.C. Estimating Physical Activity Trends among Blacks in the United States through Examination of Four National Surveys. AIMSPH 2018, 5, 144–157. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.; Wojcik, J.R.; Winett, R.A.; Williams, D.M. Social-Cognitive Determinants of Physical Activity: The Influence of Social Support, Self-Efficacy, Outcome Expectations, and Self-Regulation among Participants in a Church-Based Health Promotion Study. Health Psychol 2006, 25, 510–520. [CrossRef]

- Gothe, N.P.; Kendall, B.J. Barriers, Motivations, and Preferences for Physical Activity among Female African American Older Adults. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine 2016, 2, 2333721416677399. [CrossRef]

- Mama, S.K.; McCurdy, S.A.; Evans, A.E.; Thompson, D.; Diamond, P.M.; Lee, R.E. Using Community Insight to Understand Physical Activity Adoption in Overweight and Obese African American and Hispanic Women: A Qualitative Study. Health Education & Behavior 2015, 42, 321–328. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.K.; Afezolli, D.; Seo, J.; Syeda, H.; Zheng, S.; Folta, S.C. Perceptions of Physical Activity in African American Older Adults on Hemodialysis: Themes from Key Informant Interviews. Archives of Rehabilitation Research and Clinical Translation 2020, 2. [CrossRef]

- Keith, N.R.; Xu, H.; De Groot, M.; Hemmerlein, K.; Clark, D.O. Identifying Contextual and Emotional Factors to Explore Weight Disparities between Obese Black and White Women: Supplementary Issue: Health Disparities in Women. Clin Med�Insights�Womens�Health 2016, 9s1, CMWH.S34687. [CrossRef]

- Ala, A.; Wilder, J.; Jonassaint, N.L.; Coffin, C.S.; Brady, C.; Reynolds, A.; Schilsky, M.L. COVID-19 and the Uncovering of Health Care Disparities in the United States, United Kingdom and Canada: Call to Action. Hepatol Commun 2021, 5, 1791–1800. [CrossRef]

- Hasson, R.; Sallis, J.F.; Coleman, N.; Kaushal, N.; Nocera, V.G.; Keith, N. COVID-19: Implications for Physical Activity, Health Disparities, and Health Equity. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine 2022, 16, 420–433. [CrossRef]

- Grant, C.; Osanloo, A. Understanding, Selecting, and Integrating a Theoretical Framework in Dissertation Research: Creating the Blueprint for Your “House.” Administrative Issues Journal: Connecting Education, Practice, and Research 2014, 4, 12–26.

- Sallis, J.F.; Owen, N. Ecological Models of Health Behavior. In Health behavior: Theory, research, and practice, 5th ed; Jossey-Bass/Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, US, 2015; pp. 43–64 ISBN 978-1-118-62898-0.

- Rhodes, R.E.; Kaushal, N.; Quinlan, A. Is Physical Activity a Part of Who I Am? A Review and Meta-Analysis of Identity, Schema and Physical Activity. Health Psychol Rev 2016, 10, 204–225. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, B.; Abraham, C.; Lally, P.; de Bruijn, G.-J. Towards Parsimony in Habit Measurement: Testing the Convergent and Predictive Validity of an Automaticity Subscale of the Self-Report Habit Index. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2012, 9, 102. [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Hamilton, K.; Phipps, D.J.; Protogerou, C.; Zhang, C.-Q.; Girelli, L.; Mallia, L.; Lucidi, F. Effects of Habit and Intention on Behavior: Meta-Analysis and Test of Key Moderators. Motivation Science 2023, 9, 73–94. [CrossRef]

- de Labra, C.; Guimaraes-Pinheiro, C.; Maseda, A.; Lorenzo, T.; Millán-Calenti, J.C. Effects of Physical Exercise Interventions in Frail Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. BMC Geriatr 2015, 15, 154. [CrossRef]

- Golaszewski, N.M.; Bartholomew, J.B. The Development of the Physical Activity and Social Support Scale. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 2019, 41, 215–229. [CrossRef]

- Burner, E.; Lam, C.N.; Deross, R.; Kagawa-Singer, M.; Menchine, M.; Arora, S. Using Mobile Health to Improve Social Support for Low-Income Latino Patients with Diabetes: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of the Feasibility Trial of TExT-MED + FANS. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2018, 20, 39–48. [CrossRef]

- Page-Reeves, J.; Murray-Krezan, C.; Regino, L.; Perez, J.; Bleecker, M.; Perez, D.; Wagner, B.; Tigert, S.; Bearer, E.L.; Willging, C.E. A Randomized Control Trial to Test a Peer Support Group Approach for Reducing Social Isolation and Depression among Female Mexican Immigrants. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 119. [CrossRef]

- Dolash, K.; Meizi He; Zenong Yin; Sosa, E.T. Factors That Influence Park Use and Physical Activity in Predominantly Hispanic and Low-Income Neighborhoods. Journal of Physical Activity & Health 2015, 12, 462–469. [CrossRef]

- Webber, B.J.; Whitfield, G.P.; Moore, L.V.; Stowe, E.; Omura, J.D.; Pejavara, A.; Galuska, D.A.; Fulton, J.E. Physical Activity–Friendly Policies and Community Design Features in the US, 2014 and 2021. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2023, 20, 220397. [CrossRef]

- Obradovich, N.; Fowler, J.H. Climate Change May Alter Human Physical Activity Patterns. Nat Hum Behav 2017, 1, 0097. [CrossRef]

- Smart Growth America; National Complete Streets Coalition What Are Complete Streets? Available online: https://smartgrowthamerica.org/what-are-complete-streets/ (accessed on 7 November 2022).

- Chriqui, J.F.; Leider, J.; Thrun, E.; Nicholson, L.M.; Slater, S. Communities on the Move: Pedestrian-Oriented Zoning as a Facilitator of Adult Active Travel to Work in the United States. Front Public Health 2016, 4, 71. [CrossRef]

- Seo, B.; Nan, H.; Monahan, P.O.; Duszynski, T.J.; Thompson, W.R.; Zollinger, T.W.; Han, J. Association between Built Environment Policy and Good Health Status. Translational Journal of the American College of Sports Medicine 2024, 9, e000255. [CrossRef]

- Arena, R.; Pronk, N.P.; Woodard, C. The Influence of Social Vulnerability and Culture on Physical Inactivity in the United States – Identifying Hot Spots in Need of Attention. The American Journal of Medicine 2023, 0. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research; Fifth edition.; Pearson: Boston, 2015; ISBN 978-0-13-354958-4.

- Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C. Sage Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research; The Sage handbook of; Sage: Los Angeles, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4129-7266-6.

- Levitt, H.M.; Bamberg, M.; Creswell, J.W.; Frost, D.M.; Josselson, R.; Suárez-Orozco, C. Journal Article Reporting Standards for Qualitative Primary, Qualitative Meta-Analytic, and Mixed Methods Research in Psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board Task Force Report. American Psychologist 2018, 73, 26–46. [CrossRef]

- Hagströmer, M.; Oja, P.; Sjöström, M. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): A Study of Concurrent and Construct Validity. Public Health Nutr 2005, 9, 755–762. [CrossRef]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjostrom, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-Country Reliability and Validity. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [CrossRef]

- Davis, T.P. Barrier Analysis Facilitator’s Guide: A Tool for Improving Behavior Change Communication in Child Survival and Community Development Programs; Food for the Hungry: Washington DC, 2004;

- Kittle, B. A Practical Guide to Conducting a Barrier Analysis; Helen Keller International: New York, NY, 2017; Vol. 2;

- Egleston, B.L.; Miller, S.M.; Meropol, N.J. The Impact of Misclassification Due to Survey Response Fatigue on Estimation and Identifiability of Treatment Effects. Stat Med 2011, 30, 3560–3572. [CrossRef]

- Krosnick, J.A.; Alwin, D.F. An Evaluation of a Cognitive Theory of Response-Order Effects in Survey Measurement. Public Opinion Quarterly 1987, 51, 201–219. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.; Karim, N.A.; Oon, N.L.; Ngah, W.Z.W. Perceived Physical Activity Barriers Related to Body Weight Status and Sociodemographic Factors among Malaysian Men in Klang Valley. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 275. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.; Cychosz, C.M. Development of an Exercise Identity Scale. Percept Mot Skills 1994, 78, 747–751. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.M.; Muon, S. Psychometric Properties of the Exercise Identity Scale in a University Sample. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 2008, 6, 115–131. [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, N.; Rhodes, R.E.; Meldrum, J.T.; Spence, J.C. The Role of Habit in Different Phases of Exercise. British J Health Psychol 2017, 22, 429–448. [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behavior Research Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A Power Primer. Psychological Bulletin 1992, 112, 155–159. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.J. An Effect Size Primer: A Guide for Clinicians and Researchers. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 2009, 40, 532–538. [CrossRef]

- Schafer, J.L.; Graham, J.W. Missing Data: Our View of the State of the Art. Psychological Methods 2002, 7, 147–177. [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, J.C.; Gluud, C.; Wetterslev, J.; Winkel, P. When and How Should Multiple Imputation Be Used for Handling Missing Data in Randomised Clinical Trials – A Practical Guide with Flowcharts. BMC Med Res Methodol 2017, 17, 162. [CrossRef]

- Manly, C.A.; Wells, R.S. Reporting the Use of Multiple Imputation for Missing Data in Higher Education Research. Res High Educ 2015, 56, 397–409. [CrossRef]

- Kiger, M.E.; Varpio, L. Thematic Analysis of Qualitative Data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Medical Teacher 2020, 42, 846–854. [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.; McGannon, K.R. Developing Rigor in Qualitative Research: Problems and Opportunities within Sport and Exercise Psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 2018, 11, 101–121. [CrossRef]

- McGannon, K.R.; Smith, B.; Kendellen, K.; Gonsalves, C.A. Qualitative Research in Six Sport and Exercise Psychology Journals between 2010 and 2017: An Updated and Expanded Review of Trends and Interpretations. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 2021, 19, 359–379. [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-Item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [CrossRef]

- Wanner, M.; Probst-Hensch, N.; Kriemler, S.; Meier, F.; Autenrieth, C.; Martin, B.W. Validation of the Long International Physical Activity Questionnaire: Influence of Age and Language Region. Prev Med Rep 2016, 3, 250–256. [CrossRef]

- Quinn, T.D.; Barone Gibbs, B. Context Matters: The Importance of Physical Activity Domains for Public Health. Journal for the Measurement of Physical Behaviour 2023, 6, 245–249. [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, G.P.; Ussery, E.N.; Saint-Maurice, P.F.; Carlson, S.A. Trends in Aerobic Physical Activity Participation across Multiple Domains among US Adults, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007/2008 to 2017/2018. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 2021, 18, S64–S73. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Matthews, C.E.; Signorello, L.B.; Schlundt, D.G.; Blot, W.J.; Buchowski, M.S. Sedentary and Physically Active Behavior Patterns among Low-Income African-American and White Adults Living in the Southeastern United States. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59975. [CrossRef]

- Marquez, D.X.; Neighbors, C.J.; Bustamante, E.E. Leisure Time and Occupational Physical Activity among Racial or Ethnic Minorities. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 2009, 42, 1086–1093. [CrossRef]

- Holtermann, A.; Krause, N.; Van Der Beek, A.J.; Straker, L. The Physical Activity Paradox: Six Reasons Why Occupational Physical Activity (OPA) Does Not Confer the Cardiovascular Health Benefits That Leisure Time Physical Activity Does. Br J Sports Med 2018, 52, 149–150. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Loerbroks, A.; Angerer, P. Physical Activity and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: What Does the New Epidemiological Evidence Show? Current Opinion in Cardiology 2013, 28, 575–583. [CrossRef]

- Cillekens, B.; Huysmans, M.A.; Holtermann, A.; van Mechelen, W.; Straker, L.; Krause, N.; van der Beek, A.J.; Coenen, P. Physical Activity at Work May Not Be Health Enhancing. A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis on the Association between Occupational Physical Activity and Cardiovascular Disease Mortality. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health 2022, 48, 86–98. [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, J.Y.; Van Dyke, M.E.; Quinn, T.D.; Whitfield, G.P. Association between Leisure-Time Physical Activity and Occupation Activity Level, National Health Interview Survey—United States, 2020. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 2024, 21, 375–383. [CrossRef]

- Quinn, T.D.; Lane, A.; Pettee Gabriel, K.; Sternfeld, B.; Jacobs, D.R.; Smith, P.; Barone Gibbs, B. Thirteen-Year Associations of Occupational and Leisure-Time Physical Activity with Cardiorespiratory Fitness in CARDIA. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2023, 55, 2025–2034. [CrossRef]

- Quinn, T.D.; Lane, A.; Pettee Gabriel, K.; Sternfeld, B.; Jacobs, D.R.; Smith, P.; Barone Gibbs, B. Associations between Occupational Physical Activity and Left Ventricular Structure and Function over 25 Years in CARDIA. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 2024, 31, 425–433. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Labor Force Characteristics by Race and Ethnicity, 2022; United States Department of Labor: Washington DC, 2023;

- Abildso, C.G.; Daily, S.M.; Meyer, M.R.U.; Perry, C.K.; Eyler, A. Prevalence of Meeting Aerobic, Muscle-Strengthening, and Combined Physical Activity Guidelines during Leisure Time among Adults, by Rural-Urban Classification and Region — United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023, 72, 5. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, C.J.; Baldwin, A.S.; Bryan, A.D.; Conner, M.; Rhodes, R.E.; Williams, D.M. Affective Determinants of Physical Activity: A Conceptual Framework and Narrative Review. Front Psychol 2020, 11, 568331. [CrossRef]

- Ekkekakis, P. The Measurement of Affect, Mood, and Emotion: A Guide for Health-Behavioral Research; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK ; New York, 2013; ISBN 978-1-107-01100-7.

- Ekkekakis, P.; Brand, R. Affective Responses to and Automatic Affective Valuations of Physical Activity: Fifty Years of Progress on the Seminal Question in Exercise Psychology. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 2019, 42, 130–137. [CrossRef]

- Feil, K.; Allion, S.; Weyland, S.; Jekauc, D. A Systematic Review Examining the Relationship between Habit and Physical Activity Behavior in Longitudinal Studies. Front Psychol 2021, 12, 626750. [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, N.; Rhodes, R.E.; Spence, J.C.; Meldrum, J.T. Increasing Physical Activity through Principles of Habit Formation in New Gym Members: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Behav Med 2017, 51, 578–586. [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, N.; Rhodes, R.E. Exercise Habit Formation in New Gym Members: A Longitudinal Study. J Behav Med 2015, 38, 652–663. [CrossRef]

- Sebastião, E.; Chodzko-Zajko, W.; Schwingel, A. An In-Depth Examination of Perceptions of Physical Activity in Regularly Active and Insufficiently Active Older African American Women: A Participatory Approach. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0142703. [CrossRef]

- Cairney, J.; Dudley, D.; Kwan, M.; Bulten, R.; Kriellaars, D. Physical Literacy, Physical Activity and Health: Toward an Evidence-Informed Conceptual Model. Sports Med 2019, 49, 371–383. [CrossRef]

- Taber, D.R.; Chriqui, J.F.; Perna, F.M.; Powell, L.M.; Slater, S.J.; Chaloupka, F.J. Association between State Physical Education (PE) Requirements and PE Participation, Physical Activity, and Body Mass Index Change. Prev Med 2013, 57, 629–633. [CrossRef]

- Healy, S.; Patterson, F.; Biddle, S.; Dumuid, D.; Glorieux, I.; Olds, T.; Woods, C.; Bauman, A.E.; Gába, A.; Herring, M.P.; et al. It’s about Time to Exercise: Development of the Exercise Participation Explained in Relation to Time (EXPERT) Model. Br J Sports Med 2024, bjsports-2024-108500. [CrossRef]

- Han, W.-J. How Our Longitudinal Employment Patterns Might Shape Our Health as We Approach Middle Adulthood—US NLSY79 Cohort. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0300245. [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Luszczynska, A. Implementation Intention and Action Planning Interventions in Health Contexts: State of the Research and Proposals for the Way Forward. Appl Psychol Health Well Being 2014, 6, 1–47. [CrossRef]

- Rebar, A.L.; Williams, R.; Short, C.E.; Plotnikoff, R.; Duncan, M.J.; Mummery, K.; Alley, S.; Schoeppe, S.; To, Q.; Vandelanotte, C. The Impact of Action Plans on Habit and Intention Strength for Physical Activity in a Web-Based Intervention: Is It the Thought That Counts? Psychology & Health 2023, 0, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.N.; Hamer, M.; Gill, J.M.R.; Murphy, M.; Sanders, J.P.; Doherty, A.; Stamatakis, E. Brief Bouts of Device-Measured Intermittent Lifestyle Physical Activity and Its Association with Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events and Mortality in People Who Do Not Exercise: A Prospective Cohort Study. The Lancet Public Health 2023, 8, e800–e810. [CrossRef]

- Deslippe, A.L.; Soanes, A.; Bouchaud, C.C.; Beckenstein, H.; Slim, M.; Plourde, H.; Cohen, T.R. Barriers and Facilitators to Diet, Physical Activity and Lifestyle Behavior Intervention Adherence: A Qualitative Systematic Review of the Literature. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2023, 20, 14. [CrossRef]

- Koh, Y.S.; Asharani, P.V.; Devi, F.; Roystonn, K.; Wang, P.; Vaingankar, J.A.; Abdin, E.; Sum, C.F.; Lee, E.S.; Müller-Riemenschneider, F.; et al. A Cross-Sectional Study on the Perceived Barriers to Physical Activity and Their Associations with Domain-Specific Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1051. [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center Public’s Positive Economic Ratings Slip; Inflation Still Widely Viewed as Major Problem; Pew Research Center, 2024; pp. 1–30;

- Marcus, B.H.; Dunsiger, S.; Pekmezi, D.; Benitez, T.; Larsen, B.; Meyer, D. Physical Activity Outcomes from a Randomized Trial of a Theory- and Technology-Enhanced Intervention for Latinas: The Seamos Activas II Study. J Behav Med 2022, 45, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Marquez, D.X.; Wilbur, J.; Hughes, S.L.; Berbaum, M.L.; Wilson, R.S.; Buchner, D.M.; McAuley, E. B.A.I.L.A. - A Latin Dance Randomized Controlled Trial for Older Spanish-Speaking Latinos: Rationale, Design, and Methods. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2014, 38, 397–408. [CrossRef]

- Buja, A.; Rabensteiner, A.; Sperotto, M.; Grotto, G.; Bertoncello, C.; Cocchio, S.; Baldovin, T.; Contu, P.; Lorini, C.; Baldo, V. Health Literacy and Physical Activity: A Systematic Review. J Phys Act Health 2020, 17, 1259–1274. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.; Mendonça, G.; Benedetti, T.R.B.; Borges, L.J.; Streit, I.A.; Christofoletti, M.; Silva-Júnior, F.L.E.; Papini, C.B.; Binotto, M.A. Barriers and Facilitators of Domain-Specific Physical Activity: A Systematic Review of Reviews. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1964. [CrossRef]

- Heredia, N.I.; Walker, T.J.; Lee, M.; Reininger, B.M. The Longitudinal Relationship between Social Support and Physical Activity in Hispanics. AM J HEALTH PROMOT 2019, 33, 921–924. [CrossRef]

- Camhi, S.M.; Debordes-Jackson, G.; Andrews, J.; Wright, J.; Lindsay, A.C.; Troped, P.J.; Hayman, L.L. Socioecological Factors Associated with an Urban Exercise Prescription Program for Under-Resourced Women: A Mixed Methods Community-Engaged Research Project. IJERPH 2021, 18, 8726. [CrossRef]

- Travert, A.-S.; Sidney Annerstedt, K.; Daivadanam, M. Built Environment and Health Behaviors: Deconstructing the Black Box of Interactions—A Review of Reviews. IJERPH 2019, 16, 1454. [CrossRef]

- Serrano, N.; Leider, J.; Chriqui, J.F. Pedestrian-Oriented Zoning Moderates the Relationship between Racialized Economic Segregation and Active Travel to Work, United States. Preventive Medicine 2023, 177, 107788. [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Saelens, B.E. Assessment of Physical Activity by Self-Report: Status, Limitations, and Future Directions. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 2000, 71, 1–14. [CrossRef]

| Variable | LLPA | HLPA | p - value | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (n) | ||||

| Male | 1.00 | 3.00 | -- | -- |

| Female | 10.00 | 15.00 | -- | -- |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | ||||

| Black | 63.63 | 33.33 | -- | -- |

| Hispanic/Latino | 5.55 | 33.33 | -- | -- |

| Asian | 27.27 | 27.28 | -- | -- |

| Middle Eastern | 0.00 | 5.66 | -- | -- |

| Education (% w/ Bachelors or More) | 54.45 | 72.22 | -- | -- |

| Employed Full Time (%) | 54.45 | 77.78 | -- | -- |

| Personal Income (% > $50,000/yr.) | 9.10 | 33.33 | -- | -- |

| Did Not Answer (%) | 18.18 | 16.67 | -- | -- |

| Age (yrs.) | 39.09 (18.21) | 38.44 (14.15) | 0.92 | -0.04 |

| Body Mass (kg) | 80.95 (16.13) | 73.23 (13.60) | 0.18 | -0.53 |

| Height (cm) | 165.45 (8.45) | 164.11 (7.94) | 0.67 | -0.16 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.75 (6.24) | 27.32 (5.54) | 0.29 | -0.42 |

| Years in Community | 7.75 (8.81) | 10.18 (11.76) | 0.58 | 0.22 |

| Total Leisure-time PA (min/week) | 44.55 (48.40) | 448.89 (227.43) | 0.001* | 2.21 |

| Variable | LLPA | HLPA | p-value | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupational PA | ||||

| MVPA | 169.55 (372.90) | 468.89 (903.25) | 0.31 | 0.40 |

| Walking PA | 95.45 (94.70) | 262.28 (379.35) | 0.17 | 0.54 |

| Total PA | 265.00 (412.98) | 731.17 (1062.74) | 0.18 | 0.53 |

| Transportational PA | ||||

| MVPA | 0.00 (0.00) | 10.00 (30.87) | 0.30 | 0.41 |

| Walking PA | 140.91 (178.81) | 178.56 (147.37) | 0.54 | 0.24 |

| Total PA | 140.91 (178.81) | 188.56 (164.30) | 0.47 | 0.28 |

| Household MVPA | 284.55 (327.63) | 273.78 (208.65) | 0.91 | -0.04 |

| Leisure-time PA | ||||

| Exercise MVPA | 40.00 (48.11) | 238.89 (182.78) | 0.00* | 1.34 |

| Walking PA | 4.55 (12.14) | 210.00 (143.69) | <.001* | 1.80 |

| Total PA | 44.55 (48.40) | 448.89 (227.43) | 0.001* | 2.21 |

| Summed Domain Totals | ||||

| Total MVPA | 494.09 (398.60) | 991.56 (883.55) | 0.09 | 0.67 |

| Total Walking PA | 240.91 (196.45) | 650.83 (491.01) | 0.01* | 1.01 |

| Total PA | 735.00 (521.94) | 1642.39 (1073.98) | 0.02* | 1.00 |

| Composite Score | Group | Mean (SD) | dƒ | MS | F-statistic | p-value | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA Barrier Questionnaire (α = 0.92) | |||||||

| Personal | LLPA | 36.64 (12.53) | 10.00 | 556.14 | 5.72 | 0.02* | -0.92 |

| HLPA | 27.61 (7.88) | ||||||

| Social Environment | LLPA | 11.18 (3.57) | 10.00 | 34.18 | 2.758 | 0.11 | -0.64 |

| HLPA | 8.94 (3.49) | ||||||

| Physical Environment | LLPA | 12.91 (5.52) | 10.00 | 27.87 | 1.26 | 0.27 | -0.43 |

| HLPA | 10.89 (4.14) | ||||||

| Exercise Identity Scale (α = 0.89) | LLPA | 27.45 (7.90) | 10.00 | 141.07 | 2.79 | 0.11 | 0.64 |

| HLPA | 32.00 (6.61) | ||||||

| Self-Reported Behavioral Automaticity Scale (α = 0.97) | LLPA | 10.18 (5.06) | 10.00 | 72.68 | 3.19 | 0.09 | 0.68 |

| HLPA | 13.44 (4.60) | ||||||

| PA Social Support Scale (α = 0.84) | |||||||

| Emotional Support | LLPA | 15.73 (4.58) | 10.00 | 14.15 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.28 |

| HLPA | 17.17 (5.48) | ||||||

| Validation Support | LLPA | 11.09 (5.80) | 10.00 | 1.96 | 0.70 | 0.79 | -0.10 |

| HLPA | 10.56 (4.96) | ||||||

| Informational Support | LLPA | 13.18 (4.19) | 10.00 | 34.95 | 1.15 | 0.29 | 0.41 |

| HLPA | 15.44 (6.16) | ||||||

| Companionship Support | LLPA | 11.82 (3.71) | 10.00 | 6.62 | 0.22 | 0.64 | -0.18 |

| HLPA | 10.83 (6.32) | ||||||

| Instrumental Support | LLPA | 7.18 (6.82) | 10.00 | 231.12 | 3.79 | 0.06 | 0.75 |

| HLPA | 13.00 (8.33) | ||||||

| Group | SEM Domain | Themes & Subthemes | Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| LLPA | Personal | Lack of Time | "Online classes [take up too much time]" |

| "Work schedule [takes up too much time]" | |||

| "[Physical activity] takes time away from work, causing me to give up sleep, take an unpaid lunch break, and/or work longer hours" | |||

| "Balancing full time work and part time school [makes it hard to be active]" | |||

| Physical Capacity | "[I have] low energy, lack of high workload," | ||

| Lack of Motivation | "Lack of motivation to be physically active [makes it difficult to be active]." | ||

| "Takes a lot of time to see the results. [I] need to be motivated internally to go out and be active." | |||

| Physical Sensations Associated w/ PA | "Body pains after the exercise [make it difficult to be active]" | ||

| "Weightlifting and other vigorous activity creates soreness." | |||

| "Sweating [makes activity difficult]" | |||

| "Taking extra showers that can sometimes lead to dryer skin" | |||

| Self-Doubt | "[I discourage] myself [from being active]" | ||

| Cost Assoc. w/ PA | *Prevalent Sub-Theme in Community domain themes | ||

| Stress | "[I] worry about day to day stuff [like] bills" | ||

| Risk of Injury | "Injuries can occur when active if not careful." | ||

| Interpersonal | Missing Out on Social Events | "[Physical activity] can become one of the reasons to skip some social events." | |

| Community | Inclement Weather | "Not having any reason to go outside of my home. Bad weather like snowing/raining/strong winds." | |

| "Some days, the weather doesn't allow for me to get outside and enjoy walking or driving to the local YMCA for group exercise." | |||

| Group | SEM Domain | Themes & Subthemes | Quotes |

| LLPA | Community | Lack of PA Facilities, Public Transit in Community | "[Not having] easy access to public transport [makes it harder to be active]." |

| HLPA |

Personal |

Lack of Time | "School… discourages me from being active as [physical activity] takes up too much time in my schedule." |

| "Family obligations, work obligations, and lack of time [make it hard to be active]" | |||

| "When I miss a day. When I don't get enough sleep. When I go out of town." | |||

| "Finding time. I have two jobs that take up every single day all day." | |||

| "Making time to do it and giving up other things that may be important [is a drawback of being active]" | |||

| Lack of Time | "Work schedules and requirements that limit your time or drain you physically [discourage me from being active]" | ||

| Lack of Motivation | "[Physical activity is] not easy, because it’s hard to get motivated" | ||

| "I don’t have the energy or the motivation [to be active]" | |||

| "Lack of motivation, lack of energy and lack of knowledge [makes it hard to be active]" | |||

| Pregnancy | "Being pregnant [makes it hard to be active], as time goes on once baby is here will be finding daycare" | ||

| "My mother [doesn’t support me being active] due to being almost 7 months [pregnant]" | |||

| Risk of Injury | "Possible risk for injury if you don't know what you're doing or don't have the correct form or stretch routine [is a drawback of being active]" | ||

| "Aches and injuries [are drawbacks to being active]" | |||

| "If you do not have proper training, you can do an exercise or lift a weight incorrectly causing harm to your body." | |||

| Physical Sensations Associated with PA | "{Being active] gets tiring and sometimes overwhelming" | ||

| "Feeling lethargic, reduced mental clarity, and sore all the time [is a drawback of being active]" | |||

| Cost Assoc. w/ PA | "Programs that are expensive and not local [discourage me from being active]" | ||

| "Expensive gym memberships [discourage me from being active]" | |||

| "It's expensive [to be active]" | |||

| Lack of Knowledge About PA | "[My] lack of knowledge on what [to] do in gym [discourages me from being active]" | ||

| Interpersonal | Lack of Social Support | "Being active alone [discourages me from being active]" | |

| Group | SEM Domain | Themes & Subthemes | Quotes |

| HLPA | Community | Lack of PA Facilities, Public Transit in Community | "{Not having] a convenient gym [makes it hard to be active]" |

| "Distance and transportation [to facilities discourage me from being active]" | |||

| Societal | Social Norms Around Pregnancy | "Pregnant women shouldn’t be active" | |

| Cultural Norms Around Autonomy and/or Independence | "A cultural belief that is often shared by people in my religion is that parents are always in control of their children, no matter what their age is. They can somewhat discourage me being active if they say that we have to do something on the day that I would like to be active." |

| Group | SEM Domain | Themes & Subthemes | Quotes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLPA | Personal | Knowledge of PA Benefits | "The activities that is done to stay fit and it is very important in one’s health" | |

| "It keeps the body functions in better condition." | ||||

| "It improves both mental and physical health including decreasing anxiety and depression, reducing conditions heart conditions, improve blood sugar levels, and improve cognitive and mental function." | ||||

| "Physical activity leads to good cardiac [health] and joint mobility." | ||||

| "It is like the elixir " | ||||

| Obtaining Health Benefits Sub-Themes: Physical Health, Mental Health, Emotional Health |

"[Being active] helps one stay fit" "Being physically active helps me stay mentally fit as well. Helps me feel good about myself. If I workout in the morning, I tend to make better eating decisions as I am aware of all the hard work I have done in the morning." |

|||

| Group | SEM Domain | Themes & Subthemes | Quotes | |

| Personal | Obtaining Health Benefits Sub-Themes: Physical Health, Mental Health, Emotional Health |

"I sleep better and keep a healthy weight" | ||

| "Better bone and muscle health. You don’t seem to age." | ||||

| "Mental health benefits, more energy, increased confidence [are benefits of being active]" | ||||

| "It helps with sleep, mood, concentration, and balancing mental health struggles" | ||||

| Beliefs About the Body's Value | "The fact that my body is my home, my safe space and I want to take care of it [encourages me to be active]." | |||

| Goal Setting | "Hav[ing] a goal [helps me be more active]" | |||

| Interpersonal | Social Accountability | "I [am encouraged to be active because I] have a service dog who needs to go on walks at least 2x/day" | ||

| "[Having a] group of people committed to exercising [encourages me to be active]" | ||||

| Social Support | "Having a gym buddy [helps me stay active]." | |||

| "My community consists of active older adults who are generally very physically active." | ||||

| "My husband, my mother [support me to be active]" | ||||

| "My parents (specifically my dad) and some of my friends who are also physically active [support me]" | ||||

| LLPA | Fostering Social Relationships | "Being active allows for social interactions with people in and around the gyms, pool, pickleball court." | ||

| Community PA Facility Availability | "[Having the] gym being open 24 hours [help me be active]." | |||

| "This summer I have a student rec membership, so I have access on the days I'm at campus." | ||||

| "Inexpensive gyms within short walking distance of my job. Gym showers… The proximity of the canal." | ||||

| "Regular cricket games in softball field. Having some table tennis tournaments." | ||||

| Community | PA Community Events or Programs Sub-Theme: Cost of PA |

"Regular cricket games in softball field. Having some table tennis tournaments." | ||

| "More sports tournaments/events. Having sport groups like TT group etc. Starting some learning sessions" | ||||

| "Free community offered classes, and physical events (yoga, dance, walking/running,). A community gym offered at a free and or very reduced rate." | ||||

| "Silver Sneakers and YMCA Fitness Centers [help me be active]" | ||||

| Supportive Environments for PA | "Gym, less busy roads for walks, closer outlets [would help me be active]" | |||

| "Free access to gym/ recreational activities and resources for beginners [would help me be active]" | ||||

| "Having access to [a] swimming pool, gymnasium, walking parks, bicycle paths" | ||||

| Group | SEM Domain | Themes & Subthemes | Quotes | |

| LLPA | Community | Age Appropriate PA Opportunities | "More resources for my age group [would help me be active]" | |

| Societal | Policies that Support and/ or Subsize PA (work, school, etc.) | "[Having access to] work sponsored programs. Canal sponsored programs [would help me be active]." | ||

| HLPA | Personal | Having a Goal and Routine | "I now have a routine. I do it in the morning before the day begins. I feel better when I exercise and sluggish when I don't." | |

| Enjoyment of PA | "[Physical activity is] something that genuinely makes me happy allowing me to enjoy it." | |||

| "Remembering the benefits of being physically active [helps me be active]" | ||||

| Knowledge of PA Benefits | "Sitting is the new smoking. In other words, you need to keep moving to stay healthy." | |||

| "I know that, for starters, physical activity doesn't just play a role in physical health. It also plays a part in a person's mental health." | ||||

| "Physical activity is good for strengthening your heart and body." | ||||

| "[I am] fairly knowledgeable [about the benefits of physical activity]. The more active you are, the better health you'll have" | ||||

| "If you don't use it, you will lose it. Staying active activates the happy hormone and relieves stress; it produces clarity of the mind, walking outside provides access to attaining vitamin D naturally and walking in nature produces some peace and grounding. Weightlifting helps combat bone loss and osteoporosis. Physical activity is providing a holistic measure for producing good health, mind, body, and spirit; good health is wealth." | ||||

| Resiliency | "I really do not care about what others think of me, but most people who knows me knows that I have always been pretty active: family, friends, colleagues." | |||

| Obtaining Health Benefits Sub-Themes: Physical Health, Mental Health, Emotional Health Positive Emotional Health |

"I notice the difference in my sleep, endurance, attitude, have more energy, helps with weight loss, healthy bones, mental stamina, bowel movements." “Emotional and physical wellbeing [is improved with activity]" "Clear mind, good attitude, and decrease in depression [are benefits of being active]" "Better mental health, better mood, more energy and increases productivity." "Improved sleep, mood, blood pressure and other health vitals. Decrease in obesity [are benefits]." "[Having lower] blood glucose level and [better] cardiovascular health" |

|||

| "Overall health would improve and physical appearance as well" | ||||

| Group | SEM Domain | Themes & Subthemes | Quotes | |

| HLPA | Personal | Fitness Technology | "My Apple Watch keeps me accountable." | |

| "Apple Fitness [encourages me to be active]" | ||||

| Having Resources Available to be Active | Having access to YouTube exercise videos, having a 10/month membership at planet fitness; I enjoy being active." | |||

| Interpersonal | Social Accountability | "Community or accountability partner [help me stay active]." | ||

| "Being fit impresses people that you have self-respect" | ||||

| Social Support | "I do ‘walking Wednesdays’ with colleagues." | |||

| "Pretty much everyone around me encourages me to be active." | ||||

| "I don't think I have ever run into someone that has discouraged me from being active." | ||||

| "My fiancé, kids, and best friend [support me to be active]" | ||||

| "Coworkers, roommates, parents, spouse [support me to be active]" | ||||

| "[Being active is a] way to make new friends." | ||||

| Community | Community PA Facility Availability Sub-Theme: Cost of PA |

"Having a gym at the property [makes it easier to be active]" | ||

| "I work at a gym, and I have a gym in my apartment complex." | ||||

| "Having an opportunity/space at work to work out for 30-60 minutes [would make it easier to be active]." | ||||

| "Exploring somewhere new and having a reason to leave the house" | ||||

| "More places to play tennis or pickleball [would help me be more active]" | ||||

| "Free gym memberships with a trainer [would help me be more active]" | ||||

| "Free access to gym/recreational activities and resources for beginners [would help me be more active]" | ||||

| "Free gym membership at work/on campus for staff [would help me be more active]" | ||||

| "[Having] a gym with a daycare nearby [would help me be more active]" | ||||

| PA Events or Programs | "One thing that [my employer] does is send out emails stating that there are activities taking place and other things like that. All these activities can help a person be more active." | |||

| "[My workplace wellness] program [encourage me to be active]" | ||||

| "Health and wellness promotion at [my job encourages me to be active]" | ||||

| "More diverse classes that are affordable [and] closer to home [would help me be more active]" | ||||

| "Being a [wellness program] ambassador [encourages me to be active]" | ||||

| Group | SEM Domain | Themes & Subthemes | Quotes | |

| HLPA | Community | Supportive Built Environments | "Where I work is conducive for walking and I do ‘walking Wednesdays’ with colleagues." | |

| "I am fortunate to have sidewalks, and an inexpensive health club 5 minutes away." | ||||

| "[Having facilities] close to my house, better sidewalks [would help me be more active]" | ||||

|

Societal |

Policies that Support and/or Subsize PA (i.e., work, school, etc.) | "More work from home ability [would help me be more active]" | ||

| "Decrease in insurance costs [encourage me to be active]" | ||||

| "I have Medicaid and they recently gave me a 6 month gym membership and a fitness tracker, so that’s a bit of encouragement" | ||||

| "Something with employment, money back for being active [would encourage me to be active]" | ||||

| Religious Beliefs Around the Body, Health |

"In my religion, physical and mental health is emphasized and is stated that they are both incredibly important to a person. All of these things help me be more active." | |||

| "Take care of your body, your body is your temple" | ||||

| "Body positivity movement and the Bible says our bodies are temples for the Holy Spirit and that we should take care of them. 1 Corinthians 6:19-20 Also, the Daniel fast from the book of Daniel encourages healthy eating." | ||||

| Knowledge of Racially Prevalent Health Conditions | "History of African Americans with high blood pressure and diabetes [encourages me to be active]" | |||

| "I don’t want to end up with high blood pressure or diabetes" | ||||

| Cultural PA Norms | "Grew up with hard work and physical labor being a part of my life" | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).