1. Introduction

The rapid increase in motorization in Togo has sparked a surge in car ownership resulting in the consequential rise in the generation of end-of-life tyres. This article underscores the critical necessity of comprehending the tyre use management chain to devise efficient waste management strategies in response to escalating motorization rates. The vehicles fleet in West-Africa is made of mainly used vehicles from European and American countries [

1] which leads to the distinctive feature of Togo’s tyre management chain, which lies in the significant contribution of imported used tyres. These tyres are often imported based on their affordability and play a pivotal role in the country’s transportation landscape. However, the widespread use exacerbates the challenges associated with tyre disposal due to their shorter lifespan and increased likelihood of premature wear and tear.

A comprehensive knowledge into the Togolese tyre management chain enables the identification of specific points where tyre waste is generated. By focusing and integrating these tyre waste generation points, collection and recycling efforts can be strategically targeted to maximize efficiency and effectiveness.

Understanding the tyre management chain in Togo provides insights into market dynamics, including demand for recycled materials, economic factors and regulatory considerations. This information is essential for assessing the economic viability of recycling options and identifying potential markets for recycled tyre products. A tyre management chain encompasses the entire process of tyre production, from raw material extraction to end-of-life disposal. Initially, natural rubber is harvested from rubber trees, while synthetic rubber is produced through chemical processes. These raw materials are then processed and combined with other components such as steel, fabric, and various chemicals to form the basic structure of a tyre [

2] The manufacturing stage involves multiple steps, including mixing, calendaring, extruding, building and curing. During mixing, raw materials are blended to form a homogeneous rubber compound. Calendaring and extruding shape the rubber into sheets and treads, respectively. In the building phase, these components are assembled into a tyre structure, which is then vulcanized or cured to enhance durability and elasticity [

2]. Once manufactured, tyres are distributed through various channels to reach consumers. This stage includes warehousing, transportation, and retail. After consumer use, worn tyres are either retreaded, recycled, or disposed of. Retreading extends the life of a tyre by replacing its tread, while recycling involves breaking down tyres into raw materials for other uses. Disposal is often noted as a last resort and includes incineration or landfilling. Disposal has huge environmental implications [

3].

In West Africa, End of Life-tyres (EoL-tyres) are often disposed of in open dumps or are openly burned [

4]. Dumping of EoL-tyres poses a serious threat as EoL-tyres pose a significant problem in terms of mosquito breeding due to their ability to accumulate water and create ideal artificial habitats for mosquito larvae [

5]. This issue is exacerbated by several factors inherent to the structure and properties of EoL-tyres. EoL-tyres are not biodegradable and are expected to leach toxic chemicals when not being treated correctly [

6]. Open burning of EoL-tyres is highly toxic and has serious impact on the ambient air quality [

4] and the health of the population.

The waste management infrastructure in many African countries is not well developed and needs improvement. Effective data collection on EoL-tyres necessitates a well-established waste management system that includes collection, transportation, and disposal or recycling of tyres. However, many African countries struggle with basic waste management challenges, such as inadequate facilities and logistical issues. As a result, the systematic collection and reporting of data on EoL-tyres are often not prioritized [

7].

A tyre recycling plant is planned in Tsévié, north of Lomé. The planned tyre recycling plant will buy the EoL-tyres as feedstock to recycle the rubber and metals and produce tyre derived fuels out of the rest. By buying the EoL-tyres for the plant, the EoL-tyres generated in Togo are being given a value above their current status as waste or free burning material. This will help the used tyre dealers with generating an additional income stream and avoid open dumping and burning of EoL-tyres. For the planning of the tyre recycling plant, the pressing research questions are the estimation of EoL-tyre generation in Togo, the logistics of tyres in Togo (who deals with them and where do EoL-tyres end up?) as well as the costs of EoL-tyres.

2. Materials and Methods

The understanding of the tyre management chain in Togo is starting with the estimation of the number of tyres imported into Togo. The previous steps of the tyre management chain, which are raw material extraction and tyre production, are not existent in Togo. The only country producing tyres in the African continent is South Africa [

8].

The number of tyres which end up as End-of-Life (EoL) tyres in Togo annually is not easily available and needs to be estimated. There is no publicly available data on waste tyres generated each year. To be able to calculate the potential annual numbers of EoL-tyres, data from port authorities and Togolese customs were enquired and collected based on the number of imports of new and used tyres as well as vehicles. Unfortunately, this information has not been released. Data on vehicle registration numbers has also been demanded from the respective authorities, but also the requests have not been fulfilled yet.

An estimation on the vehicle numbers in Togo has been carried out to estimate the minimum number of tyres currently being in use in Togo. The estimation of the data on EoL-tyre generation in Togo was carried out based on the estimations carried out in Ghana [

9]. These estimates have been modified and matched to local country conditions of Togo. The choice of estimating the EoL-tyre generation based on Ghana’s data, is due to the geographical proximity of both countries as they share a border and similar road infrastructure. The data used for estimations, were also the only reliable data which has been found for the estimations on EoL-tyre generation in Sub-Sahara Africa. [

9]’s estimations on the generation of EoL-tyres in Ghana is derived from the Ghanaian Ministry of Transport and is based on the annual numbers of vehicles in use in Ghana until 2015, derived from the International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers and the annual numbers of newly registered vehicles in Ghana until 2016. These numbers were extrapolated with medium annual growth rates until 2019 and resulted in an estimated amount of 1.092.000 vehicles in use in Ghana. These were sub-categorized into passenger vehicles (715.000 vehicles) and commercial vehicles (377.000 vehicles). The population of the neighboring countries Ghana and Togo were extracted from [

10]., for the year 2019 and are displayed at

Table 1.

When dividing the number of passenger vehicles through the population numbers in Ghana (see equation 1) for the baseline year 2019 of the study, an average of 0,0227 passenger vehicles per person were registered in Ghana and an average of 0,0120 commercial vehicles were registered per person in Ghana in 2019.

Adapting the vehicle per capita numbers to the neighboring country Togo as of equation 2, a very rough estimation of potential vehicle numbers in Togo in the baseline year of 2019 can be estimated.

Additional assumptions for the estimation of EoL-tyre generation in Togo:

Each passenger vehicle uses 4 tyres

Each commercial vehicle uses 6 tyres

Average weight of used passenger car tyre: 7kg

Average weight of used commercial vehicle tyre: 40 kg

The average lifetime of tyres has been researched through a set of interviews in Lomé, Togo in February 2024. The interview questions were “how often do you need to replace your tyres?” and “do you buy new or used tyres?”. The interview was split into the vehicle types and the indicated number of vehicle users were interviewed as in

Table 2. In total 199 interviews were carried out.

For commercial vehicles only buses and trucks are considered in this case. Smaller commercial vehicles such as tricycles (abobayas) and auto-rikshaws were not able to be estimated in numbers so far. As no information is available regarding the exact numbers of buses and trucks registered in Togo so far, for estimation purposes of the tyre replacement frequency, the ratio will be considered to be 50/50.

The estimation of the annually generated amounts of EoL-tyres has been carried out with equation 3 (adapted from [

9]).

In order to evaluate the used tyres management chain and EoL-tyres management chain two methodological approaches were adopted, 1.) the empire-industive method based on direct observation and 2.) the hypothetico-deductive method based on the interviews (nearly 200 used-tyre dealers).

The questions in the interviews with the tyre dealers focused on a) understanding the demographics of tyre dealers/tyre mechanics in Togo, b) the logistics of tyres in Togo and the organization as well as c) the costs of tyres in Togo (see

Table 3).

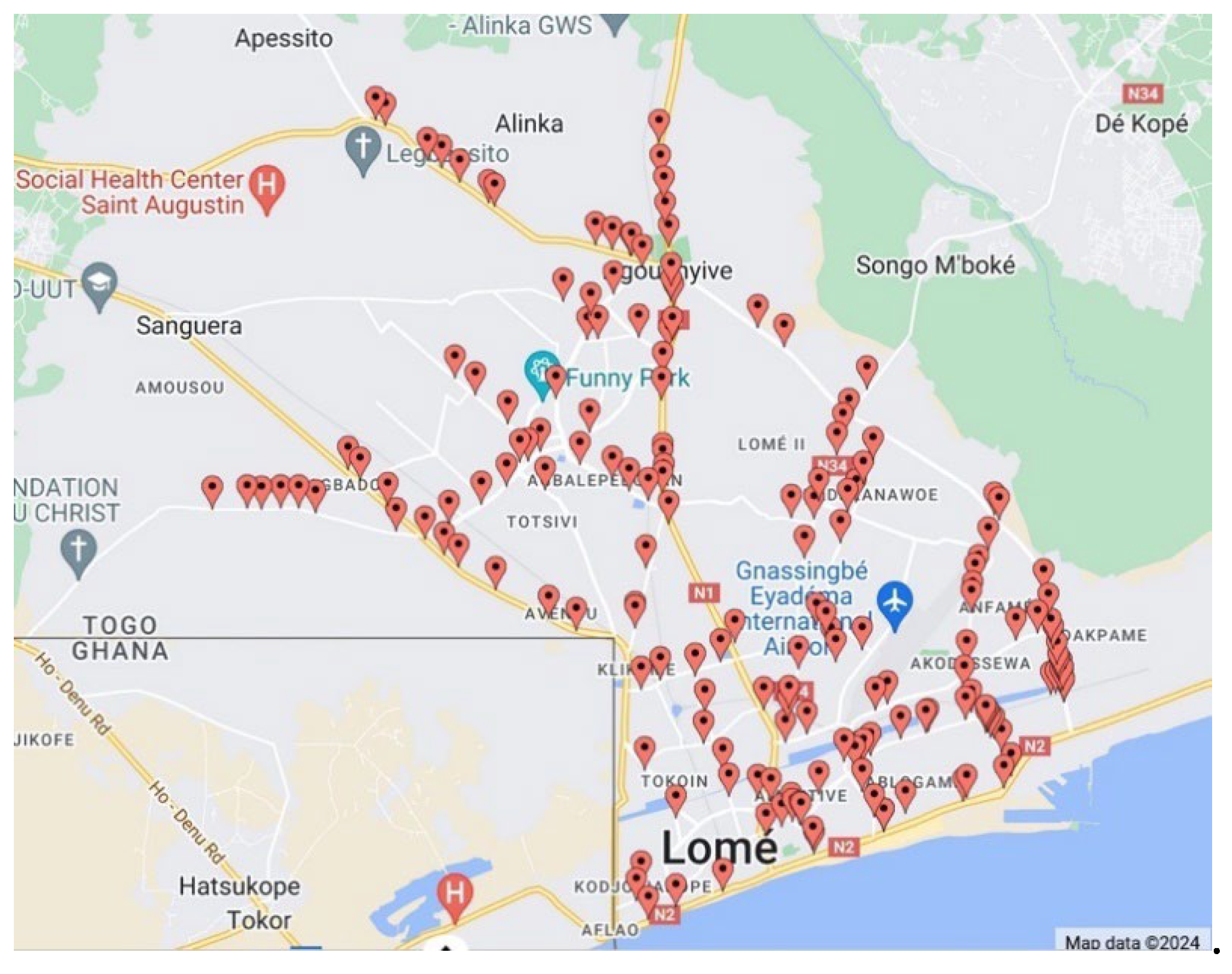

The interviews with the tyre dealers were carried out in February 2024 in Lomé, Togo and surroundings. In order to estimate how many people are doing business with tyres, it has been tried to gather an overview on all tyre dealers in the greater Lomé region.

For this, Lomé was traveled through by motorcycle on all paved roads, omitting sand/dust roads and all bigger (40+ tyres) tyre dealerships were mapped. Sand/dust roads were omitted as tyre dealership are more likely to be located at the bigger, paved roads as higher traffic can be expected there.

The focus on medium to big tyre dealerships, which most often also offer pressured air, was because smaller tyre dealerships often change their locations and are harder to follow-up. The tyre dealerships were approached by the interviewer with a questionnaire and asked the questions in either French or the local language Ewé.

Questions were asked open-ended in order to not give any suggestions or answer ideas to the interviewees. Answers including multiple answers, for example when it comes to the question regarding the treatment of the EoL-tyres, were also allowed.

3. Results

3.1. End-of-life tyre generation

The estimation of the annual generation of EoL-tyres in Togo is based [

9] and is adapted and modified to fit the country Togo. Further the modified model has been also tested for other countries and can be easily applied.

Based on equation 2, the number of vehicles in Togo for the year 2019 has been estimated (

Table 4).

The tyre durability in Togo is strongly dependent on the vehicle type and the use of the vehicle.

Commercially used vehicles, irrespective of their vehicle type had a very short turnover of tyres. The shortest replacement frequency was given for buses, where the bus drivers reported a change of tyres every 2.4 months. Buses, as well as trucks, according to the interview results, are utilizing new tyres for replacement, but due to their heavy loads and mileage they don’t last for a long time (see

Table 5).

For passenger vehicles used as taxis, the average tyre lifespan was 3 months. Taxi drivers frequently change their EoL-tyres with other used tyres according to this study.

Official vehicles and private motorcycles are the vehicles with the least frequent tyre changes (31,5 months and 28,1 months respectively). Both of these vehicle users buy new tyres for their vehicles.

For the estimation of EoL-tyre generation, it is important to note that taxis account for 75% - 80 % of motorized transport in Sub-Saharan Africa [

11]. For passenger vehicles this means that approx. 75% of the overall numbers of vehicles have a tyre replacement frequency of 3,4 months, while all other passenger vehicles have a joint tyre replacement frequency of 19,4 months. The average tyre replacement frequency is at this rate at 7,4 months (0,62 years) for passenger vehicles. This is in accordance with data generated by [

9].

The estimation of EoL-tyres from passenger vehicles and commercial vehicles (trucks and buses) used in Togo has been carried out according to equation 3.

Table 6 shows the estimation of generated EoL-tyres in 2019 for Togo.

A total of 78,040.52 t/a of EoL-tyres has been estimated to have been generated in Togo in 2019. Ghana’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2019 was at

$68.34B [

12], with a GDP per capita at

$2,168 and is thus higher than Togo’s GDP in 2019 at

$6.99B (

$848 per capita) [

12]. The higher GDP per capita in Ghana might lead to higher private vehicle ownership per capita in Ghana compared to Togo. The correlation between income growth and private vehicle ownership is well documented by many authors [e.g. 13-15] and thus the per capita private vehicle ownership in Togo might be well overestimated in this article and might actually be up to 2/3 smaller. This has, of course, also impacts on the amounts of annually generated EoL-tyres in the country.

To take the size of the country’s economy into account, equation 3 has been adapted and modified through an addition of the GDP value, which is displayed in equation 4.

By correcting the total of generated EoL-tyres numbers by taking the per capita GDP into account, the total numbers of generated EoL-tyres in Togo are estimated to be at a total of 30,525.11 t/a of EoL-tyres in 2019 (see

Table 6).

3.2. Tyre dealerships

Through the empire-industive method of direct observation, 188 tyre dealerships with a stock of 40+ tyres were mapped in the greater Lomé region (see

Figure 1).

Attempts were made to interview every dealership with the hypothetico-deductive method, but some were closed already and many of the tyre dealers were reluctant to give out information due to fear of taxation or any unfortunate repercussions on their businesses, so the interaction was sometimes difficult and challenging. This behavior has also been observed by [

16]. Additionally, at some sites, the mechanics were busy and not available to exchange information, or their boss was away, and they could not bear the responsibility to exchange any information.

When it comes to the demographics of the tyre management chain in Togo, questions were asked on who is involved with the tyre dealerships to be able to understand the potential sellers of the EoL-tyres as materials for the recycling plant.

Tyre dealerships in Togo include the immediate tyre fitting as well as repair and the fill up with compressed air. Tyre dealerships were 100% in male hands in Togo, with ages of the dealers/mechanics ranging from 15-54 years. The average age of a tyre dealer/mechanic was 28 years.

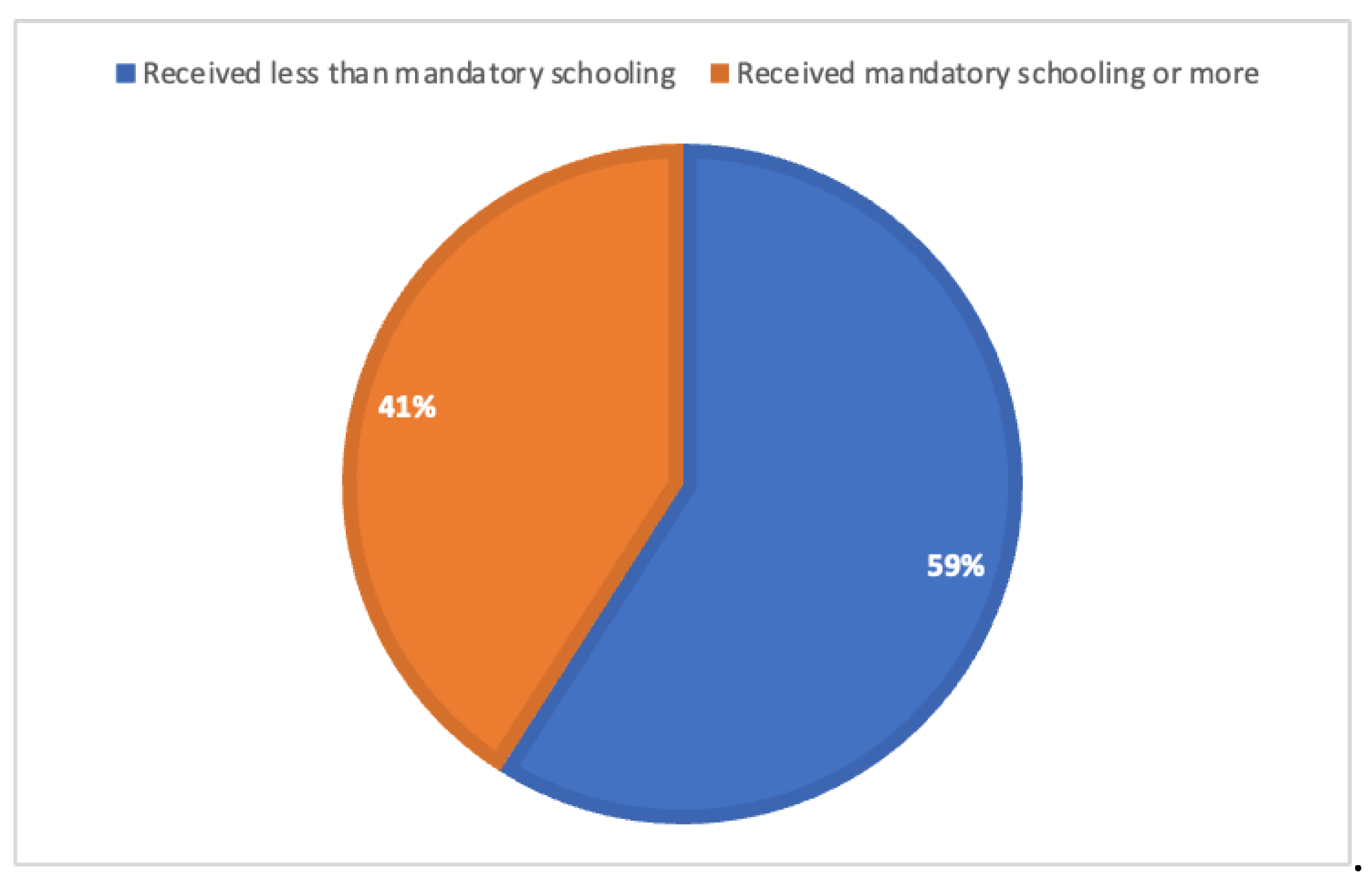

The average tyre dealer does not have a good education level. In total 105 people answered the question about their education levels, out of these nearly 60 % have received less than the mandatory 6 years of schooling in Togo [

17] (see

Figure 2).

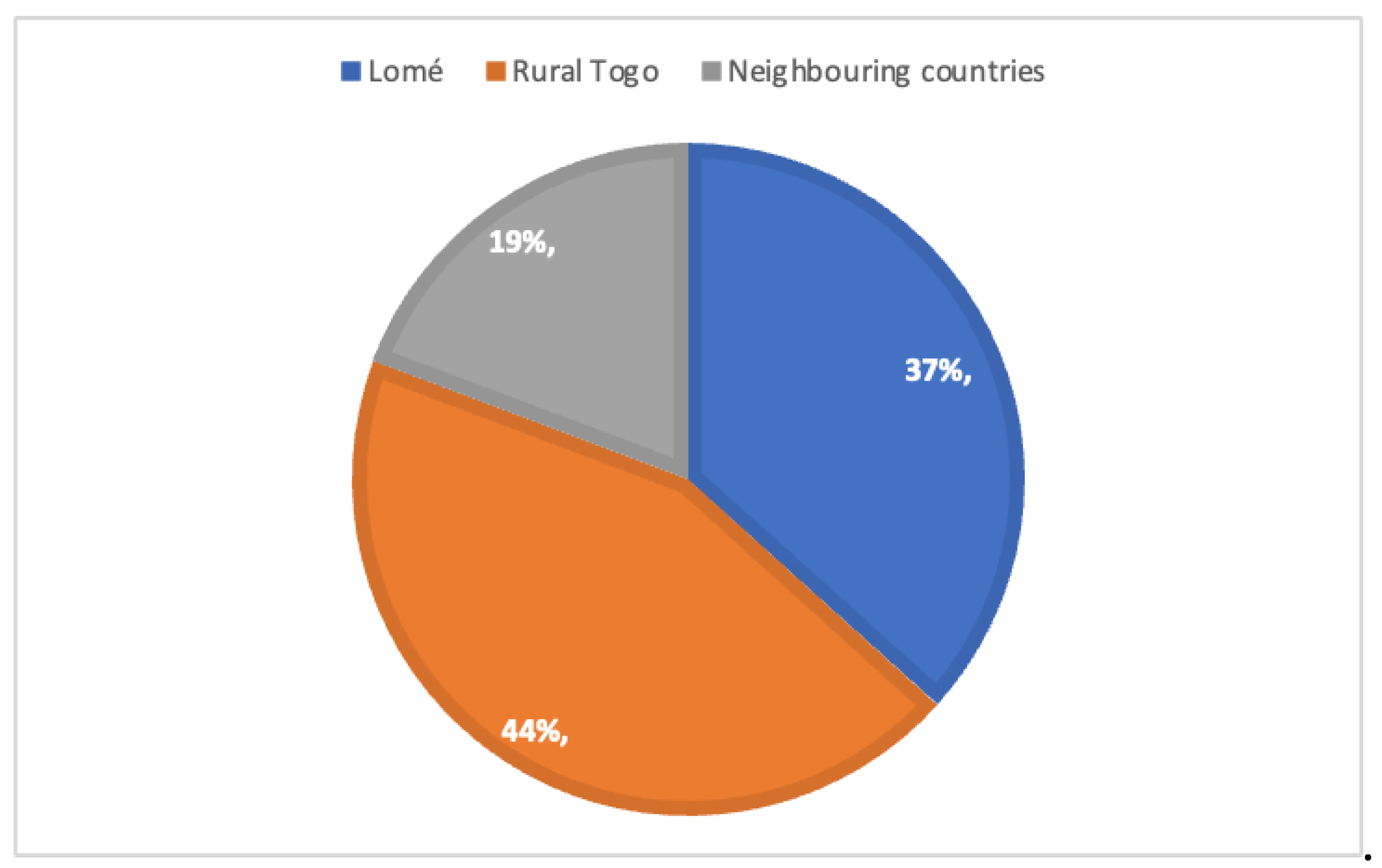

Further, nearly half of all tyre mechanics/dealers in Lomé are from rural Togo and have moved into Lomé (see

Figure 3). 20% of all active mechanics are from neighboring West-African countries such as Benin, Nigeria, and Ghana.

The logistics of the tyre dealers showed that all tyre dealers, who gave answers to the question on where they purchased their tyres (either new or used), obtained their tyres mainly from the port. It is possible to buy tyres there in bulk and in smaller margins. Due to the close proximity of the port to Lomé, no middlemen are necessary for the distribution between the tyre dealers/mechanics and the port.

The tyre dealers/mechanics not only sell tyres, but also change and replace or repair the tyres for the customers. In this way, the tyre dealers are the people receiving the EoL-tyres directly from their customers.

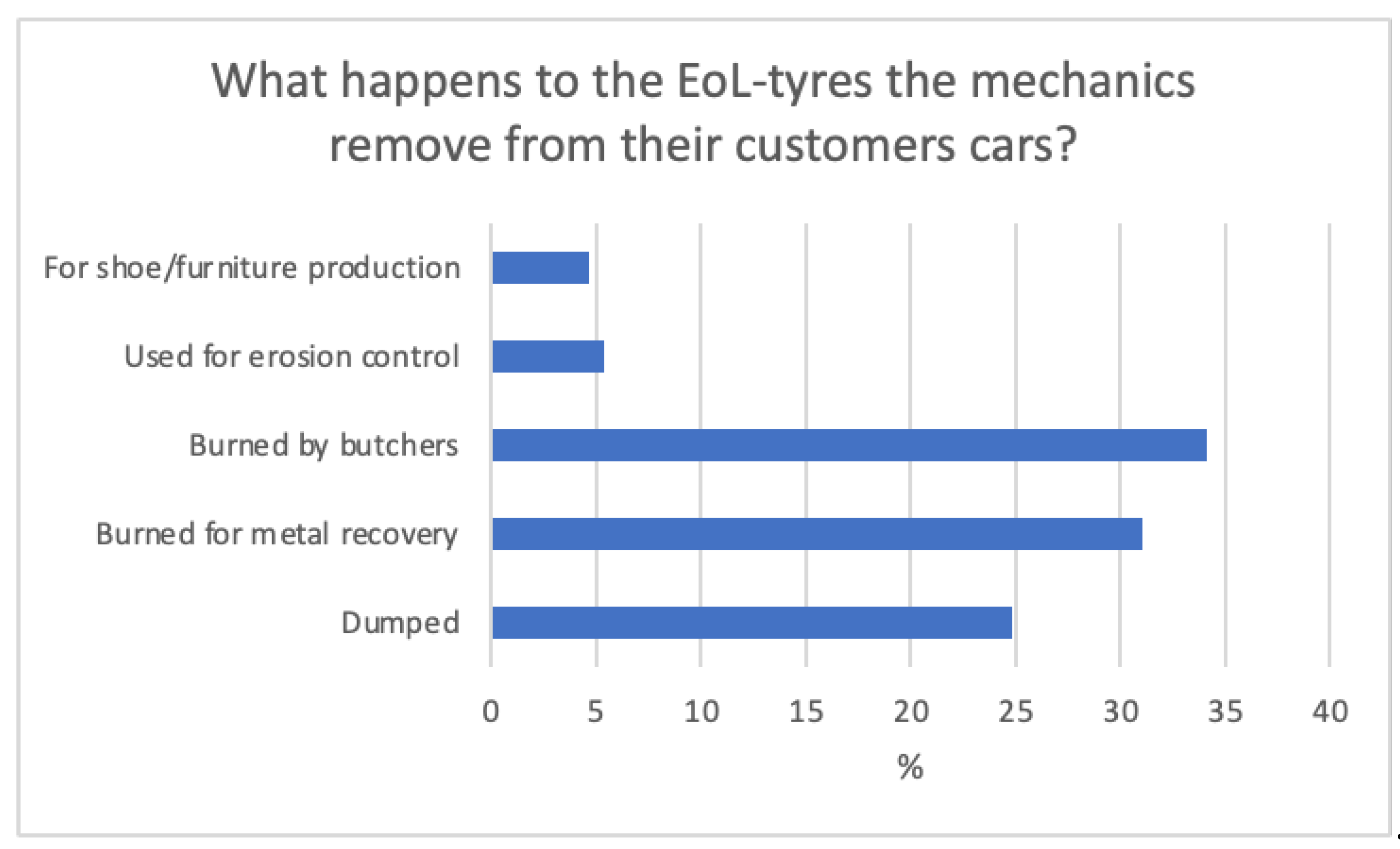

In regard to the treatment of the EoL-tyres, answers were divided into five main categories as highlighted in

Figure 4.

Most of the answers highlighted the fact that EoL-tyres were simply dumped in a convenient location, often directly next to the tyre dealership (see

Figure 5) or that they were either burned for the recovery of iron or by butchers.

A secondary use of EoL-tyres, such as erosion control, to protect trees or to delineate football fields was less common and that EoL-tyres were collected by recyclers to up-cycle the EoL-tyres into shoes or furniture was the least frequent answer.

The tyre dealers/mechanics are well organized and have founded two professional associations namely Syvemoto and AVT. 52% of the tyre dealers/mechanics work together in these associations all together.

3.3. Financial aspects

The question on the buying price of the tyres from the port of Lomé were not answered by any of the tyre dealer/mechanic in this interview round.

The selling price of a tyre also differs extremely, depending on the type of tyre dealership. In real shops with a stock of several hundred tyres, a tyre for a passenger vehicle costs between 15.000 – 25.000 XOF (approx. 23 – 38€). In smaller shops the prices for a tyre are between 4.000-15.000 XOF (approx. 6-23 €), averaging at approx. 9.000 XOF (ca. 13,70 €).

EoL-tyres did hardly yield any revenue. Most tyre dealers gave the tyres away for free or for a nominal price such as 50-300 XOF (0,08 € - 0,46 €).

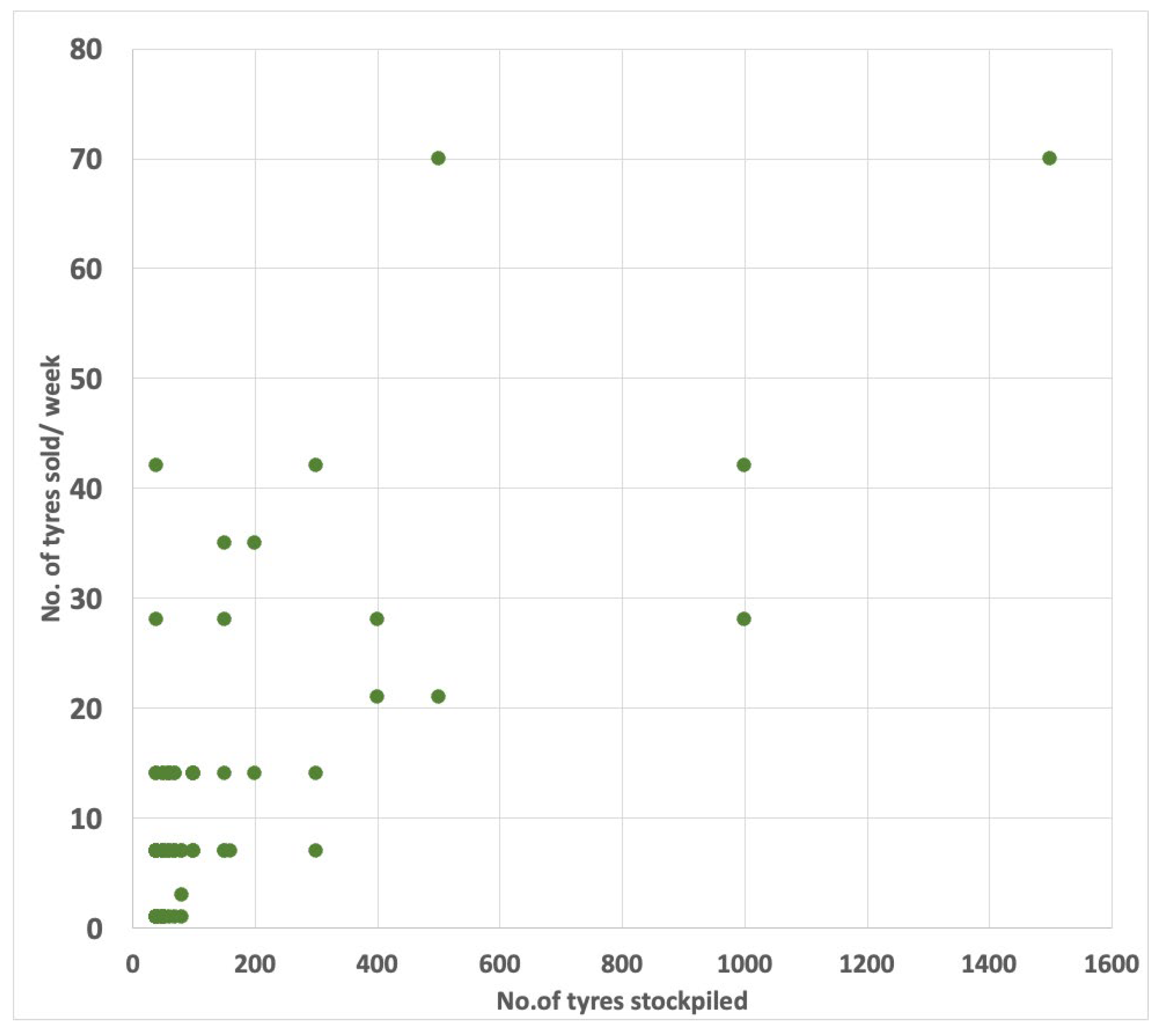

Selling tyres is not a profession which guarantees a continuous stream of income to the dealers. One hundred of the interviewed tyre dealers gave information on how many tyres they sell in a day.

As can be observed in

Figure 6, most tyre dealers sell less than 20 tyres in a week. One third of all tyre dealers who offered an answer on this question, answered that they “rarely” sell a tyre. This information has been added as “1 tyre per week“ into

Figure 6. The bigger tyre dealers with an estimated stockpile of 400 tyres and more show more success and sell more tyres weekly than the smaller tyre dealers.

4. Discussion

This research has been carried out in the frame of the “Waste-to-Energy as a sustainable solution for West Africa” project, in which one part is the development of a tyre recycling plant in Togo.

The understanding on the tyre management chain plays a pivotal role in the decision-making for the plant.

The availability and accessibility of EoL-tyres within Togo must be assessed as the collection phase is critical and determines the supply of raw materials to the planed recycling plant. The estimated data of 30,525.11 t/a of EoL-tyres generation for Togo for 2019 gives the first indignation for the plant size to be built.

The tyre recycling plant is planned to be in Davié, north of Lomé, and is under construction as of June 2024. It is planned with an hourly capacity of 8 t, being able to process all of Togo’s generated EoL-tyres, when working in two shifts, in approximately 272 days. The average working days (Monday-Friday) without taking holidays etc. into account, sum up to approx. 260 days, which means the plant will be able to process nearly all of Togo’s annually generated EoL-tyres.

It is assumed that the collection of EoL-tyres needs to be widened to the neighboring countries, as collection rates of 100% will hardly be achieved throughout the country due to its high variations in urban and rural areas.

The estimated numbers also explicitly exclude smaller commercial vehicles, such as tricycles (so called Abobayas) or auto-rikshaws and motorcycles. The weight of these EoL-tyres has also not been estimated yet.

The generation of EoL-tyres on buses and trucks can be explicitly more as especially trucks often have so many more tyres than the 6 tyres used in this study (see

Figure 7). Togo is also a transit country for countries further north, who are doing their business at the port of Lomé. This allows for a lot of truck traffic from especially Burkina Faso and Niger to travel through Togo and generate EoL-tyres along the way. The EoL-tyre generation amounts are thus only an estimation and could be estimated most likely with a range between 30,525.11 t/a – 78,040.62 t/a.

For the use of EoL-tyres in a tyre recycling facility, not only the annually generated EoL-tyres play a role, but also the EoL-tyres that have been produced in the past. These tyres were either burned in some capacity or dumped. The estimation of the numbers of dumped EoL-tyres in Togo is not possible.

Data on EoL-tyre generation is not only lacking for Togo but for most West-African countries.

[

6] observed that most research literature on waste tyres and waste tyre rubbers was written in China, USA, and India and hardly any research on EoL-tyres and EoL-tyre production has been published from West-Africa or Africa in general with some exemptions from notably northern Africa and South Africa. A report from World Business Council for Sustainable Development [

18] reported on EoL-tyre recovery rates worldwide and only included Morocco and South Africa for the African continent. A few publications on selected countries are available, which gives detailed estimations on the number of EoL-tyre generation in Ghana [

9]. Similarly, [

19] roughly estimated the generation of EoL-tyres in Botswana, without diving deep into details. The scarcity of data on EoL-tyres in African countries, excluding few North African countries and South Africa can be attributed to a multitude of factors. These include the lack of comprehensive waste management systems, insufficient regulatory frameworks, economic constraints, and limited research initiatives focused on EoL-tyre management.

The regulatory framework concerning EoL-tyres is often either absent or poorly enforced in these regions. In contrast, North African countries and South Africa have implemented more stringent environmental regulations and policies that mandate the tracking and management of EoL-tyres. For instance, South Africa’s Waste Tyre Regulations under the National Environmental Management such as Waste Act, enforce detailed reporting requirements on the production and disposal of tyres [

20]. The absence of such regulations in other African countries leads to minimal emphasis on the need for data collection and reporting.

Economic constraints further exacerbate the issue. Many African countries face significant financial limitations that hinder their ability to invest in advanced waste management technologies and data collection systems. The high cost associated with establishing and maintaining comprehensive EoL-tyre management programs, including data collection, often competes with other economic priorities [

21].

Additionally, there is a noticeable lack of research and academic interest in EoL-tyre management in these regions. The focus of environmental research in many African countries tends to be on more immediate environmental concerns, such as water and air pollution, deforestation, and climate change. Consequently, EoL-tyre management does not receive the same level of attention or funding resulting in limited scholarly output and data availability

In contrast, North African countries and South Africa have more developed economies and stronger institutional frameworks that support environmental research and data collection efforts. These countries also receive more international aid and cooperation for environmental projects, which often include components on waste management and EoL-tyres [

23].

The lack of data on EoL-tyres in many African countries, as well as in Togo, is a result of inadequate waste management infrastructure, weak regulatory frameworks, economic constraints, and limited research focus. Addressing these issues will require concerted efforts to improve waste management systems, enforce regulatory measures, secure financial investments, stimulate academic and policy-oriented research on EoL-tyre management [

6].

By investigating the number of EoL-tyres in West-Africa, a data and knowledge gap can be closed, and the size of the EoL-tyres waste management problem can be estimated.

The current treatment of EoL-tyres in Lomé poses a serious threat to the Togolese populations and environmental health.

According to the results of this study, nearly 25% of all EoL-tyres are simply dumped by the tyre dealers. Approximately 65% of the generated EoL-tyres are being burned for either metal recovery (31%) or by butchers (34%).

Dumping of EoL-tyres poses a serious threat as EoL-tyres pose a significant problem in terms of mosquito breeding due to their ability to accumulate water and create ideal artificial habitats for mosquito larvae [

5]. This issue is exacerbated by several factors inherent to the structure and properties of EoL-tyres. EoL-tyres are not biodegradable and are expected to leach toxic chemicals when not being treated correctly [

6]. Landfilling EoL-tyres, a step above simply dumping them randomly, is also not a preferred option as EoL-tyres occupy a large space, leaving less area for other wastes resulting in higher need of landfilling [

24].

The design of EoL-tyres allows them to retain rainwater, which can remain stagnant for extended periods. This stagnant water provides a perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes, particularly species such as

Aedes aegypti and

Aedes albopictus, which are vectors for diseases like dengue, Zika virus, and chikungunya [

5]. The impermeable nature of the rubber material prevents the water from evaporating quickly, thus extending the duration in which the water remains suitable for mosquito larvae to develop. Additionally, the dark color of the tyres retains heat, which can accelerate the growth and development of mosquito larvae. The warmth creates a micro-environment that can support higher survival rates of mosquito larvae, leading to increased mosquito populations in areas where scrap tires are prevalent [

25].

According to the CDC-US Center for disease control and prevention [

26], Togo is only in sporadic risk of Dengue fever, especially in the southern parts. Further north, bordering to Burkina-Faso, the risk of Dengue fever is becoming continuous.

According to the interview results most of the EoL-tyres will be burnt in Togo. Burning tyres for metal recovery or other purposes has direct impact on the ambient air quality. Studies [

4] on the total suspended particulates (TSP) generated by burning tyres, highlight the toxicity of burning tyres in the open environment, as a TSP of up to 1670 µg/m

3 has been observed for car tyres. The maximum safe amount of TSP in the ambient air is 250 µg/m

3 [

27] Excess TSP in the air can lead to respiratory and cardiovascular problems in humans [

28].

Other pollutants emitted during burning of EoL-tyres are carbon monoxide, sulphur oxides, nitrogen oxides, volatile organic compounds, cyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, dioxins, furans, hydrogen chloride, benzene, polychlorinated biphenyls, arsenic, cadmium, nickel, zinc, mercury, chromium, and vanadium [

29].

[

4] state that “the continuous exposure to gaseous and particular emissions from open burning of scrap tyres could pose major threats to human health and environment”. Tyres used as fuel by butchers has only been described by few articles [16, 30, 31] and seems to be a local West African specialty. [

31] focus on the occupational exposure of butchers to emissions from burning tyres, whereas [

16] was focusing on the awareness and perceptions of Ghanaian citizens on the health implications of tyre grilled meats for human consumption. [

30] carried out some sort of meat analysis for heavy metals on the meat grilled on tyre fuels. Results showed that consumers of these kind of meats ingested high levels of Fe (iron) and Cr (cromium) which are not safe for human consumption.

The high number of answers (34%) in this study’s interviews referring to the EoL-tyres being used by butchers, implies that the practice of using EoL-tyres for meat grilled is also common in Togo. This has been supported by informal local information.

The results show that EoL-tyres need to be given a value in Togo in order to discourage these harmful practices and generate another stream of income from EoL-tyres.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, Narra, M.-M.; methodology, Narra, M.-M..; software, Gbiete, D..; validation, Narra, M.-M.., Gbiete, D.. and Narra, S..; formal analysis, Narra, M.-M..; investigation, Narra, M.-M. and Gbiete, D..; data curation, Narra, M.-M..; writing—original draft preparation, Narra, M.-M..; writing—review and editing, Narra, M.-M..; visualization, Narra, M.-M..; supervision, Nelles, M. and Agboka, K..; project administration, Narra, M.-M..; funding acquisition, Narra, S.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.