1. Introduction

Digital transformation with new technologies and processes impacts almost every part of life and turns workplaces upside down. Organisations need to reconfigure relevant capabilities to stay on track and fulfil mandatory obligations or customer needs. New concepts must be developed to identify, build and extend relevant new competences of employees. For a better understanding of these urgent requirements, let us take the healthcare sector as an example. New, digital processes and business models are promising benefits for cost-containment measures as well as opportunities to improve patient-centric care and offer digital services [

1,

2]. However, the transformational process is lagging behind expectations. The healthcare sector is characterised by an extremely varied stakeholder structure with very different capabilities [

3]. Hospitals may embrace new technological opportunities but investments in cost expensive technological infrastructure could be a barrier [

1,

4]. Patients may benefit from digital services, but there is a significant proportion, mostly older people, who do not have the technological equipment or who lack the competences to use these services [

5,

6]. Medical doctors or other healthcare providers can be the linchpin in supporting patients and guiding them through the digital offering [

7]. However, the openness to integrate new technologies, learning and gaining necessary competences are prerequisites for this [

8,

9].

These examples highlight the need for dynamic capabilities and new routines to cope with rapidly changing environments and challenges. There is a large body of research on dynamic capabilities. However, the focus was mainly on the relationship between dynamic capabilities and organisational performance. Albert-Morant et al. [

10] indicate that recent literature concerns issues like technology or managerial aspects. Only a few researchers are drawing a connection between dynamic capabilities and learning. But even in these works, there are fragmented viewpoints, research focuses on knowledge management, managerial capabilities and organisational learning [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Zollo and Winter [

15] presented in their work a possible solution for the ongoing discussion, pointing out that learning itself could be considered as a dynamic capability to shape operational capabilities [

11]. Learning is investigated as a process of renewal to create (explore) and use (exploit) knowledge [

16].

Assuming learning as a dynamic capability, we aim to investigate learning not as a process, but as the strived outcome including desired individual mindsets and behavioural aspects. Overall, there is a need for more quantitative research, investigating the mechanisms in new digitally transformed environments, and sectors with less focus on performance and competitive advantages, like public administration or the healthcare sector [

17,

18]. With this study, we want to shed light on new concepts of dynamic capabilities in those less competitive sectors, building the ground for quantitative research. We argue that in the context of the contemporary dynamic digital transformation of workplaces, there is a need for a new concept at the employee level – sustained learning. For employees, it is not enough only to be ready to embrace learning and acquire competences from time to time, this should be a continuous, sustained process. We claim this sustained learning as a new micro foundation of organisational dynamic capabilities since this could ensure that digitalisation is a continuous process, and organisational dynamic capabilities are sustained over time. Therefore, this paper aims to define sustained learning, integrating the concept of learning, including knowledge management, building or reconfiguring relevant competences in the digital transformation process and providing measures on the individual level for further empirical testing.

Our research has a theoretical contribution, extending dynamic capabilities to meet mandatory digital offerings in a regulated setting with restricted competition and defining sustained learning as the new dynamic capability for digital transformation in healthcare. We also provide methodological novelty, building the ground for quantitative research with the newly developed construct and measures.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. First, we build the theoretical foundation, introducing the basic elements of dynamic capabilities theory and its current shortcomings in integrating continuous learning processes, resulting in sustained learning capabilities. In the first qualitative part of the study, the new construct is conducted, and items are developed to measure it. As a basis for this, we investigated the similar concepts of learning goal orientation, growth mindset and organisational learning theory concerning their suitability to explain this micro foundation. The definitions of these concepts were evaluated to their extinction to the new construct. Next, we develop the construct definition and an initial question pool described in the methodological section. Then we provide the results of the qualitative interviews to sharpen the definition and items for measuring as well as two quantitative tests: the distinctiveness to the similar constructs and the underlying dimensionality of our new construct. We discuss the potential of the construct to explain sustained learning capabilities and provide measurements to finally present our conclusions and suggestions for future research.

2. Literature Review and Analysis

Taking a deeper insight into digital transformation in the healthcare sector, it is obvious, that it falls short only to focus on technology as humans are also decisive. The provision of healthcare services is based on the interaction between people, technology and databases [

19]. Knowledge and competences of individuals are shaping capabilities, as Goldin and Katz [

20] highlighted in their work, examining the relationship between growth, technology, and education in the case of the U.S. labour market. They argue that human capital is a significant driver for economic development with the need for investments in human capital especially in knowledge of new technologies.

A main challenge is the uncertainty due to the disruptive changes caused by digital transformation. To succeed in this change, organisations need to develop dynamic capabilities. Dynamic capabilities are defined as the firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments [

21].

There are two different schools of thought in dynamic capabilities research, both grounded in evolutionary elements [

22]. Eisenhardt and Martin [

23] argue that dynamic capabilities consist of a specific set of processes, therefore, best practices can be identified on an industry or firm level [

23]. On the contrary, Teece, Pisano and Shuen [

21] focus on the individual firm level with the role of routines, individual characteristics and behaviours to achieve variation and adoption as an outcome in disruptive and rapidly changing environments [

22]. Despite the large body of research examining dynamic capabilities, there are some critiques due to the vagueness of fundamental concepts and the low level of empirical testing [

24]. Agarwal and Selen [

25] note that most studies investigating dynamic capabilities focus on the structures and origins, but quantifiable concepts are needed to understand and influence the effects. This shortcoming is particularly evident in the discussion about the role of learning, in which some see learning as a process that is shaped by dynamic capabilities, while others argue that learning mechanisms control the development of dynamic capabilities [

11].

The necessary development of digital competences, knowledge management and deployment [

26] is a new challenge, leading to a never-ending process of learning. Continuous learning and knowledge improvement are arising as a dynamic capability itself to enable innovation and digital transformation [

27,

28]. We therefore assume learning as an essential dynamic capability of individuals and firms which should be a continuous process, namely it should be sustained over time. Digital competences occur as the first building block to be developed for this desired outcome of sustained learning in this disruptively changed environment. First, we investigated the following existing concepts, and if they are suited to explain sustained learning as a new micro foundation of organisational dynamic capabilities.

3. Learning goal Orientation

Learning goal orientation is part of a multidimensional construct, developed by Vandewalle [

29] to distinguish between prove and avoid dimensions for problem-solving tasks with adults as the target population in the field of social sciences. Learning goal orientation is defined as the desire to develop the self by acquiring new skills, mastering new situations, and improving one

’s competence [

29]. The other two dimensions of the overall construct of goal orientation measurement are to prove (performance) goal orientation and avoid (performance) goal orientation. This concept does not capture all the nuances of contemporary learning processes in organisations. It thus differs from sustained learning since it was developed long ago and is mid-specific for the major life domains such as academics, work, and athletics. Learning goal orientation is based on the work of Carol Dweck about problem-solving tasks and mastery patterns as a unidimensional construct using single-item instruments with young children or adolescents as the target population [

29].

4. Growth Mindset

The second concept is the growth mindset which was also integrated into this research. It postulates, that intelligence is malleable and can be changed. Failures are an opportunity to learn and grow with the belief in the importance of effort [

30]. The construct is unidimensional. In her later work, Dweck [

31] gives an overview of the three decades of her research and offers a variety of examples and domains from sports and relationships. However, the growth mindset concept is widely applied in the domain of education within the field of psychology. The distinction between growth or fixed mindsets and sustained learning lies within the assumption, that how much effort is invested depends on the prospect of success. Behavioural psychological experiments according to the learning outcomes of children or students are the focus of growth mindset research, hence it is solely not sufficient as a concept in the contemporary era of digitally transformed workplaces. However, the motivation and self-efficacy of individuals [

32] are decisive for learning outcomes. Therefore, our newly developed sustained learning integrates the aspect of open mindsets, leading to behavioural changes and implementation to adapt to changing environments caused by new workplace environments.

5. Organisational Learning

The third concept is organisational learning, which is researched from various viewpoints and different levels; hence it is also investigated in the context of digital transformation and is, therefore, a relevant basis for the development of the new construct. There is no common definition of organisational learning[

33]. In digital transformation, dynamic capabilities are relevant to the reconfiguration of human resources. Organisational learning is multidisciplinary, including organisational behaviour, cognitive and social sciences, and strategic management [

34]. The definition provided by Crossan et al. [

16], as a dynamic process of learning and renewal in organisations on individual, group, and organisational levels therefore was adopted for this study. Organisational learning is complex, due to the variety of factors which are impacting these institutional learning processes in an organisation. The newly developed concept of sustained learning differs therefore from organisational learning theory, on the individual aspects which are affecting the organisation’s capability to reconfigure and adjust human resources in change processes for digital workplaces. The construct of sustained learning is multidimensional with organisations as targeted populations in the work domain. Organisational artefacts, values and culture are not targeted in our concept.

6. Materials and Methods

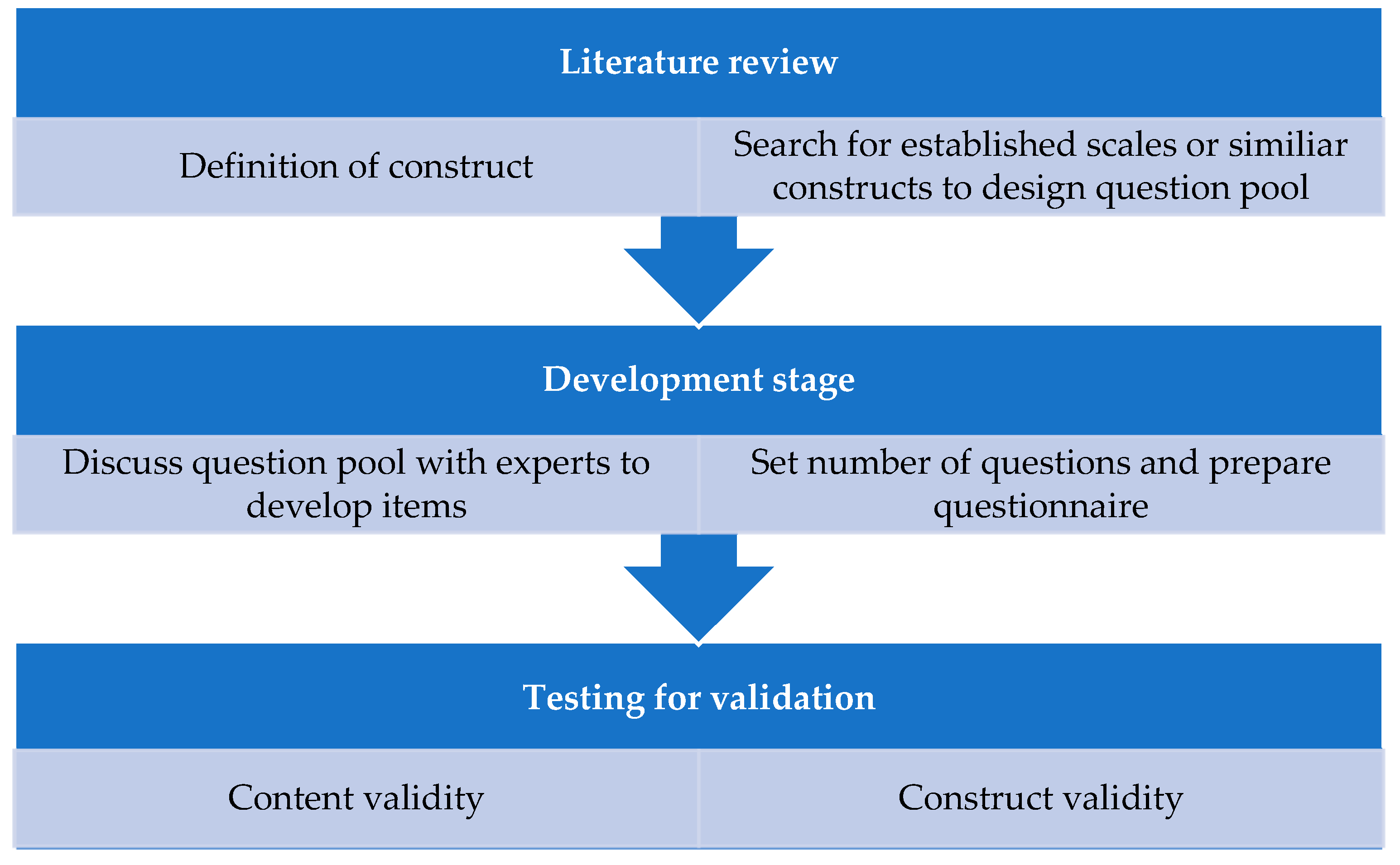

This study longs to provide a definition and create a valid instrument to measure the new construct of sustained learning. To achieve valid content, questions must be developed, that are representative to measure the investigated construct [

35]. A mixed methods approach is applied. In the first step of developing the questions, the construct is determined, and previous literature is reviewed to identify referring scales [

36]. Based on this, questions are developed and discussed with experts in interviews as qualitative research [

37,

38]. For validating the resulting number of questions, a survey was applied to assess the extent, to which these questions match the construct of sustained learning in comparison to similar constructs as the quantitative part [

39].

Figure 1.

Steps to conduct a new construct, authors own illustration based on Straub [

35]

.

Figure 1.

Steps to conduct a new construct, authors own illustration based on Straub [

35]

.

According to this, a literature review was conducted in 02/2024 to develop the concept and define the construct. Structuring the gathered data, similar constructs and measures which could be adopted were identified. A search in the database Scopus with the search terms “sustain*” AND “learning” within article title, abstract and keywords between 2004 and 2024 and English language leads to 48.093 documents. The subject was limited to social sciences and business, management & accounting. After limiting to open access publishing only, 9.066 documents remained. Due to this high number, the search was limited to the article keywords “learning”, “sustainable development”, “education”, “innovation” and “knowledge” limiting the results to 3.160 documents.

These documents were searched for quantitative articles using the keywords

“quantitative

”,

“questionnaire

”,

“survey

” and

“item

”, resulting in 744 papers. The abstracts of this residual database were searched for matching constructs, 704 articles were sorted out, and 40 were selected for a deeper investigation of the full paper. This literature review was the foundation for developing the initial broad question pool since adopting existing measures is recommended to address issues of clarity and content validity in operationalising the new construct [

40].

A group of experts was established to discuss the definition and the initial pool of questions [

35]. Experts from different countries were asked to participate, chosen due to their professional experience, expertise or specific knowledge who are themselves part of the field of activity [

38]. The experts were selected based on the author

s’ network and a search for suitable expertise in the research portal of the state of Rhineland-Palatinate “Sciport”, which offers web access to scientists, research activities and publications. This purposive sampling is commonly used for expert interviews [

37]. The expert group covers different viewpoints and expertise, as displayed in

Table 2. The questions were enhanced in comprehensibility and ranked to choose the most suitable questions to measure the construct. Qualitative interviews were conducted in-person or online using MS Teams in 03/2024 to refine and validate the definition, subdimensions and quality of the questions. The interviews and documents were provided in English and German language. For the German translation of documents, the tool DeepL was used. The quality of translation was also discussed with German participants. The question pool was rated by these experts based on a 7-point Likert scale to choose the final question setting. Therefore, the mean was calculated and ranked.

Validity is of high importance to prove that the instrument is measuring what it is about to measure [

35]. Since content validity is widely applied to prove that the items are suitable to measure the defined construct [

41], this was evaluated by calculating the Content Validity Index (CVI) for each item [

42]. As quality criteria, the Mean value for every item was calculated to only keep the questions which are best suited to measure the construct [

43]. Based on this, only items were kept which were judged as appropriate to measure the defined construct, and Hinkin Tracey Correspondence Index (HTC) was calculated in addition to ensure content validity [

44].

The narrowed question pool was tested in a quantitative survey set up on Prolific in the next step. The extent, to which the questions are measuring the defined construct compared to provided definitions of similar constructs was rated [

39]. Prolific is a marketplace for online survey research. This tool has already been applied in other research in the field of digital transformation in healthcare [

7].

7. Results

The developed concept is grounded on existing research and further expanded in the context under consideration. We assume that individuals play a key role in achieving digital progress through new learning processes in an agile working culture [

8]. According to the research of C. Dweck [

31], a growth mindset leads to developing the full potential of people and pushes organisations into a transformative change. As a result, we initially defined sustained learning as a new pattern of behaviour with a basic attitude towards learning that enables organisations to continuously develop or reconfigure competences (knowledge and skills). Sustained learning is supported by behaviours that include the ability to explore, recognise and solve problems, as well as the willingness to acquire relevant competences autonomously and improve them continuously. Therefore, three dimensions resulted: Mindset, Behaviour and Improvement. This initial definition, the dimensions and the developed question pool based on the literature review are provided in

Appendix A. Grounded on this concept, sustained learning as a dynamic capability is the desired outcome to support digital transformation in healthcare or other similar sectors where the offered services are highly demanded or not interchangeable. The constant progress and improvement of employees’ learning produce unimaged outcomes and conditions for success [

30]. It enables companies to digitally transform, based on the capability to identify or reconfigure capabilities and adapt innovations [

45]. For validation, expert interviews (

Table 1) were conducted to discuss construct and item clarity and evaluate congruence [

44].

As recommended by Lunn, a minimum of 3 experts are needed. The total number of interviews was determined by the principle of “theoretical saturation” [

46]. The experts were first asked to evaluate the definition and the dimensions. It was discussed, if the definition is understandable in the context and the derived dimensions are comprehensible based on this provided definition. With the results, improvements and adjustments were made and again discussed in the next interview.

After 4 interviews there were only minimal findings, after 9 interviews no further improvements were made, so satisfaction was reached. The developed question pool based on the literature review was also discussed. As a qualitative aspect, the experts were asked to evaluate, if the questions matched the dimensions and were comprehensible. To measure content validity, the experts ranked all 19 questions on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (the question is extremely poorly suited to measure the construct) to 7 (the question is extremely well suited to measure the construct). 4 represents the median (the question is acceptable to measure the construct). For all items, the Mean value, and Content Validity Index (CVI) [

42] were calculated and displayed in

Table 2. CVI is widely applied to measure content validity, where experts judge the relevance of items and agree on their suitability [

42].

Table 2.

Results of expert question ratings.

Table 2.

Results of expert question ratings.

| Question |

Expert Rating |

Calculated Values |

| |

Dimension |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

Mean* |

CVI |

| 1 |

Mindset |

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

5,00 |

0,67 |

| 2 |

Mindset |

|

|

1 |

|

1 |

7 |

|

5,56 |

0,89 |

| 3 |

Mindset |

|

1 |

|

|

1 |

3 |

4 |

5,89 |

0,89 |

| 4 |

Mindset |

|

|

|

|

2 |

3 |

4 |

6,22 |

1,00 |

| 5 |

Mindset |

|

|

|

1 |

|

1 |

7 |

6,56 |

0,89 |

| 6 |

Mindset |

|

2 |

1 |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

5,00 |

0,67 |

| 7 |

Behaviour |

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

6 |

|

5,56 |

0,89 |

| 8 |

Behaviour |

|

2 |

|

1 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

5,00 |

0,67 |

| 9 |

Behaviour |

|

|

|

1 |

|

4 |

4 |

6,22 |

0,89 |

| 10 |

Behaviour |

|

|

2 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

4,89 |

0,67 |

| 11 |

Behaviour |

|

|

1 |

|

2 |

4 |

2 |

5,67 |

0,89 |

| 12 |

Behaviour |

|

|

|

|

2 |

4 |

3 |

6,11 |

1,00 |

| 13 |

Behaviour |

|

|

1 |

|

1 |

4 |

3 |

5,89 |

0,89 |

| 14 |

Behaviour |

1 |

2 |

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4,78 |

0,67 |

| 15 |

Improvement |

|

|

|

3 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

5,44 |

0,67 |

| 16 |

Improvement |

|

|

1 |

|

|

5 |

3 |

6,00 |

0,89 |

| 17 |

Improvement |

|

1 |

|

|

2 |

3 |

3 |

5,67 |

0,89 |

| 18 |

Improvement |

|

|

|

|

2 |

5 |

2 |

6,00 |

1,00 |

| 19 |

Improvement |

|

|

1 |

|

|

7 |

1 |

5,78 |

0,89 |

All questions with a mean rating of 5.75 or lower were sorted out as quality criteria to achieve a rounded rating of 6 or 7 as very good and extremely well suited to measure the construct [

43]. The critical value of CVI depends on the number of experts. According to Almanasreh, Moles, and Chen (2019), content validity is given, when the proportion of experts with a number 5-10 experts in total, which are rating the item as relevant, meets the threshold of 0.78. CVI is usually applied for a 4-point Likert scale, where values of 3 and 4 are considered relevant. So, for this study all values above the median, therefore 5 to 7 on the 7-Point Likert scale were included. According to that, the initial pool was narrowed down to 3 items for each dimension. As a result of the expert interviews, sustained learning is finally defined as an attitude of individuals that combines new patterns of behaviour with a continuous willingness to question routines or habits and learn new things. Sustained learning includes the motivation to explore new things, to recognize and solve problems, as well as the willingness to autonomously acquire relevant knowledge and competences. This individual attitude and behavioural pattern enable organisations to continuously develop or reconfigure resources in digital transformation. The initial three dimensions were critically discussed but decided to keep them refined as the individual attitude with an open mindset, the behavioural pattern of questioning habits and routines and the continuous improvement of competences as the outcome. These descriptions and finalised questions are provided in

Appendix B.

For these selected 9 questions, the Hinkin Tracey Correspondence Index (HTC) as an additional consensus index was calculated (

Table 3). This index was developed by Colquitt et al. [

39], analysing 112 scales published in high-ranked journals. In this calculation, the average score is divided by the number of options in the scale as universally applicable evaluation criteria [

44]. A perfect match is represented by value 1, very strong ≥ 0.91, strong 0.87 to 0.90, moderate 0.84 to 0.86, weak 0.60 to 0.83 and lack of content validity ≤ 0.59. According to this, the resulting HTC value of 0.87 represents a high match, therefore the items correspond to the construct definition. Content validity is a necessary precondition for establishing construct validity [

48].

In the next step, additional quantitative research was applied to test the distinctiveness of the newly developed construct. The shortened number of questions resulting from the expert discussion was rated compared to similar constructs. Therefore, a questionnaire was provided in Prolific (Appendix C) according to the recommendations by Colquitt [

39]. The survey intended to evaluate to what extent the questions are adequate to measure the new sustained learning construct and provide evidence of its distinction from similar constructs [

39]. 212 participants joined the online distributed survey, of which 11 did not finish the questionnaire. So, in total 201 respondents rated the questions for each provided construct. The results of this survey are displayed in

Table 4.

The items measuring sustained learning were rated as well suited to measure the construct (value 5 and above), except question number 9. The questions in the third dimension (improvement) were all rated as slightly more suitable for measuring the construct of learning goal orientation. With these results in mind, a survey consisting of the 9 questions measuring the 3 newly defined dimensions of the construct sustained learning, was placed in prolific for a first test and better understanding of the underlying dimensionality. Part- or full-time employed persons in Germany were asked to participate. 205 responses were received. The socio-demographics of the participants are provided in Appendix D.

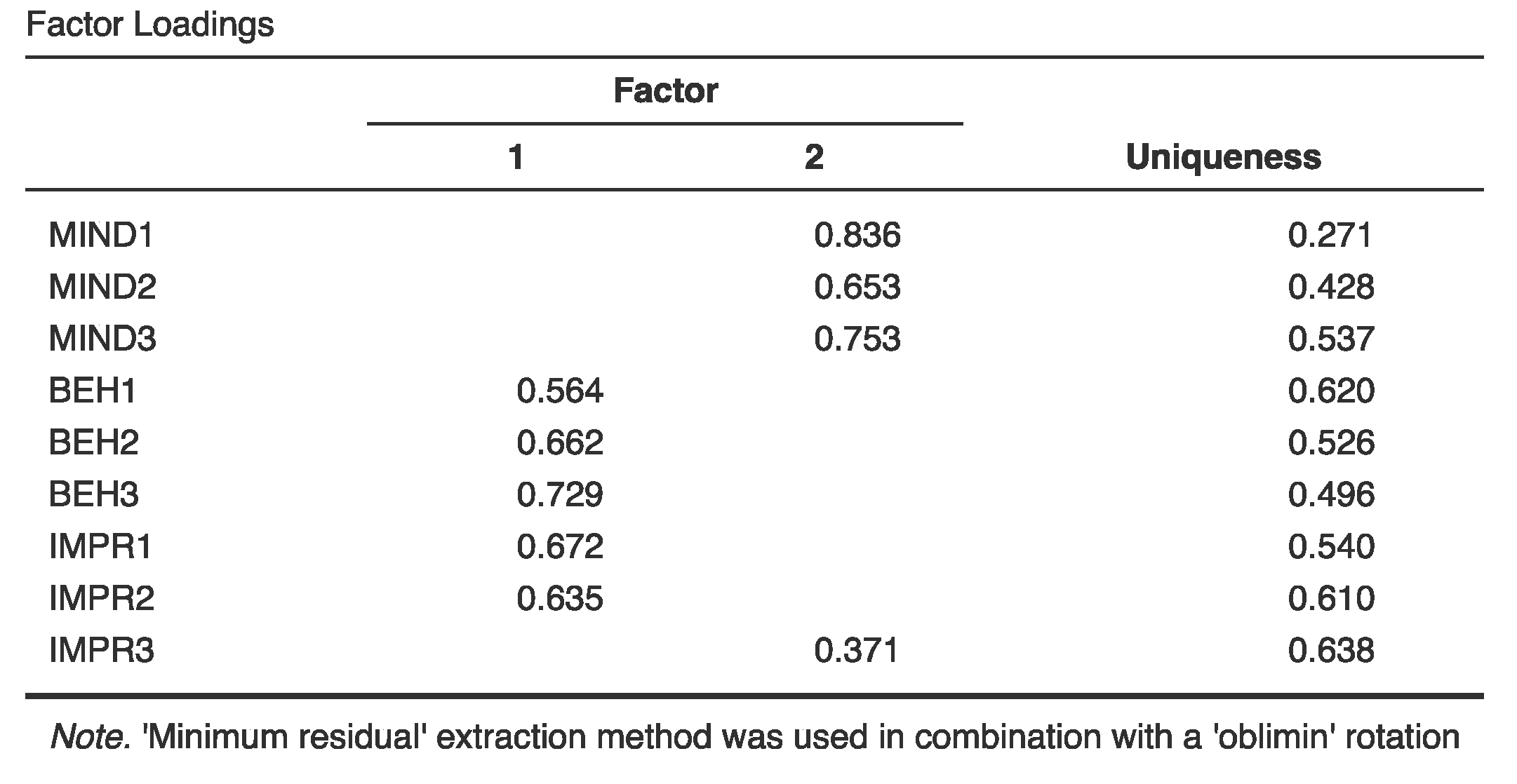

For evaluation, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted using the software Jamovi. The EFA resulted in two main factors (

Figure 2). The items measuring the third dimension “improvement” are closely related to the items measuring the dimension of behavioural patterns.

The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was measured to assess the model fi

t’s quality. The resulting value of 0.0630 points to a good model fit between the hypothesised and observed data [

49].

In addition, chi-square (x2), p-value (p) and chi-square divided by the degrees of freedom (df) were assessed as measures of model fit (

Table 6). According to the rules of thumb provided as a reference by Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger, and Müller (2003), all fit measures show good model fit.

To assess the reliability, Cronbach´s alpha was calculated for each dimension and the whole scale. The Cronbach´s alpha reliability coefficient for the overall sustained learning construct was 0.859, for the dimensions Mindset 0.797, and Behaviour 0.712, therefore reliability is given. Only the third dimension Continuous Improvement does not meet the threshold.

Based on these results, we conclude Sustained learning is a 2-dimensional construct. The respective survey items to measure the construct subdimensions are highlighted in

Table 7.

8. Discussion

Within this paper, the authors strived to develop a new construct of sustained learning and provide suitable measures for its subdimensions. The expert discussions in the qualitative part enabled the development of the concept and a question pool. It provided insights in the basic elements of sustained learning as dynamic capability and underpins the relevance of this research, supported by other authors, highlighting the fundamental importance of knowledge and learning [

11,

17].

The theoretical foundation of a large body of the latest research on the topic of digital transformation is grounded on the theory of dynamic capabilities, explaining the firm’s ability to react in uncertain and dynamic environments by sensing, seizing and configuring internal and external resources [

21]. Learning is frequently mentioned as a relevant factor and possible opportunities to sustain learning are investigated[

51,

52], but there is still poor knowledge about competence generation and the relationship between learning and dynamic capabilities, as Zollo et al.[

15] highlight in their work. Based on existing literature, we created the initial definition of sustained learning. We first revealed three dimensions of the construct, according to the basic mindset to be open to something new, the behavioural aspect to act and reflect and the implementation of continuous improvement and learning loops. This is in line with the work of Augier et al. [

13], which points out the relevance of integrating behavioural aspects in elaborating concepts of technological evolution and innovation, with the role of learning routines.

Testing the distinctiveness to similar constructs, the questions measuring the first two dimensions exposed a clear differentiation from established constructs. Only the third dimension, measuring continuous improvement, indicates a different result. These questions seem more related to learning goal orientation. The discussed meaning of this subdimension was to measure the outcome as continuous improvement of competences. Vandewalle, (1997) developed an instrument to measure goal orientation in work domains. His learning goal orientation subdimension was based on the Work and Family Orientation (WoFo) Questionnaire. The learning goal orientation focuses on the strived achievement of goals in sports or careers. The subdimension of continuous improvement in our construct represents the implementation of new behavioural patterns resulting from an open mindset, leading to the fact, that the items measuring these dimensions are closely related to the concept of learning goal orientation. The items measuring the subdimension continuous improvement have already received mixed reviews in the discussions from the experts. Some believed dimensions 2 and 3 belong together and argued, that a behaviour change requires some kind of implementation as a result. As there were also opposing views, the initial decision was made to keep the three dimensions separate and to test the underlying dimensionality in a questionnaire.

Evaluating the exploratory factor analysis according to the responses to this questionnaire (

Appendix B), the arguments of experts against the third dimension were confirmed, resulting in only 2 subdimensions. As already displayed, the dynamic capabilities of organisations include routines, enabling organisations to act in a planned manner to unexpected changes [

27]. Changes are often forced by environmental conditions, as Winter [

53] argues, that dynamic capabilities can be distinguished from regular capabilities by the reaction to the change. Reacting and ad-hoc problem-solving can be categorised as regular capability. This may lead to a learning process through adjustment but is no dynamic capability, which is characterized by routines, clear patterns of behaviour and evolutionary development [

53]. Based on that, the elaborated 2 dimensions of the construct, mindset and behaviour, match best the intention to measure sustained learning as a dynamic capability and is supported by previous literature [

15,

22,

27,

54]. We decided to exclude the critically discussed third dimension, which occurs to better suit measuring learning orientation. Since the construct is meant to measure sustained learning as a capability, this exclusion can be argued referring to Dougherty [

55], stating that a “capability” refers to the potential to do things, whether they are done or not.

The results suggest that the developed items are valid, and the model evaluation provided a good fit. Our study supports the arguments of other researchers, postulating a connection between dynamic capabilities and learning [

11,

15], linking both streams to the new concept of sustained learning.

9. Conclusions

Digital transformation is not just a trend, it has arrived in almost every aspect of life with a massive impact on workplaces. As we are at the advent of Industry 5.0 with generative AI and robot collaboration, it is inevitable to integrate human capital into this ever-changing process. Research on dynamic capabilities is one of the most prolific streams [

10]. It is widely applied in the context of digital transformation with the basic elements to sense, seize and reconfigure resources to build dynamic capabilities and adapt to transformed workplaces based on routines and behavioural patterns [

21]. Another prominent research stream in the digital transformation investigates knowledge management, competences and learning [

56,

57,

58,

59].

The present study was undertaken to develop a new concept linking the research streams of dynamic capabilities with learning and provide measures to assess sustained learning as a strived outcome in less competitive sectors like healthcare or public administration. We defined the concept of sustained learning, identified and validated 2 subdimensions and tested them compared to similar constructs.

Our research has a theoretical contribution by extending dynamic capabilities theory in providing the new construct of sustained learning as the desired outcome to succeed in digital transformation in healthcare.

The conceived measurement on the individual level makes it easier for organisations to measure this concept and apply it to their employees. Therefore, the managerial implication of our research is to enable organisations to gain new insights into the sources of their dynamic capabilities.

It also provides a methodological novelty by developing a new scale to measure sustained learning as a ground for quantitative testing. The initial results are very promising but need to be validated by further examination. We will address two issues for future research.

First, the dimensions of sustained learning should be refined with additional qualitative exploration of the third dimension of continuous improvement. Interviews or a case study can be conducted for deeper insights. Second, there is the need for quantitative research to test the impacting factors on sustained learning as a dynamic capability in digital transformation. A model could be developed and tested including the improved questionnaire.

This study has of course its limitations since it was only tested with a limited number of participants for a first validation. The developed new concept with its subdimensions should be tested in the addressed sectors with less need for competitive advantage or performance as a strived outcome.

Author Contributions

S.S.: Conceptualization, investigation, methodology, data collection and analysis, validation, and writing—original draft preparation. I.L.: writing—review and editing, supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Internal and External consolidation of the University of Latvia” No. 5.2.1.1.i.0/2/24/I/CFLA/007, grant number Nr. 71-20/386.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were not required for this study because it was non-interventional with no risks. The participants were fully informed about our research aims and the use of the data with guaranteed anonymity.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Initial Definition of Sustained learning: a new pattern of behaviour with a basic attitude towards learning that enables organisations to continuously develop or reconfigure competences (knowledge and skills). Sustained learning is supported by behaviours that include the ability to explore, recognise and solve problems, as well as the willingness to acquire relevant competences continuously and autonomously.

Based on this definition developed from literature review, the dimensions of the construct sustained learning were determined as:

Open mindset to explore new things.

Question habits and routines.

Continuous improvement of own competences.

Table A1.

Initial Question Pool.

Table A1.

Initial Question Pool.

| Item |

Question |

Source |

| Mindset |

I would never stop learning as there is a risk of not keeping up to date and missing out on opportunities. |

[60] |

| Mindset |

New experiences with digital technologies or tools are learning opportunities for me. |

[61] |

| Mindset |

I regularly join or listen to conversations and discussions about new technologies. |

[62] |

| Mindset |

I can derive new ideas from things I have learned. |

[63] |

| Mindset |

If there are new technologies or tools, which make things easier for me, I want to know more about it. |

New |

| Mindset |

I incorporate feedback to make changes in my behaviour |

[64] |

| Behaviour |

I am interested in new topics, try to interact, and informed myself about occurring new technologies. |

[63,65,66] |

| Behaviour |

I value original ideas and constant innovation. |

[67] |

| Behaviour |

I am watching explanation videos (e.g., on youtube or other platforms) and / or read additional instructions to improve my knowledge. |

[65] |

| Behaviour |

I am not afraid to critically reflect my underlying assumptions. |

[62,67] |

| Behaviour |

If I learn something new about digital technologies, I think about how I could transfer this into my daily routines. |

[65] |

| Behaviour |

If I learn something new about digital technologies, I rethink how I did things before and try to make it better based on my new knowledge. |

[65] |

| Behaviour |

I continuously judge my decisions and activities towards using digital technologies. |

[62] |

| Behaviour |

One of my basic values is to include learning as a key to improvement. |

[67] |

| Improvement |

I try to integrate digital technologies, even if I need to think about doing things in a different way I did before. |

[61,65] |

| Improvement |

I view the ability to learn as the key to improvement. |

[60] |

| Improvement |

I long for learning to improve myself. |

[60] |

| Improvement |

I perceive learning as investment, not an expense. |

[60] |

| Improvement |

I can transfer the knowledge I already have to adapt other similar technology |

[66] |

Refined Definition after Expert-Interviews of Sustained Learning: An attitude of individuals that combines new patterns of behaviour with a continuous willingness to question routines or habits and learn new things. Sustained learning includes the motivation to explore new things, to recognize and solve problems, as well as the willingness to autonomously acquire relevant knowledge and competences. This individual attitude and behavioural pattern enable organisations to continuously develop or reconfigure resources in digital transformation.

After discussion, the 3 dimensions were revised in terms of content and kept for testing:

Individual attitude: Open mindset to explore new things - Accept.

Behavioural pattern: Questioning habits and routines – Act and Reflect.

Outcome: Continuous improvement of competences – Implementation and learning loops.

Table B1.

Refined Question Pool after Expert Interviews.

Table B1.

Refined Question Pool after Expert Interviews.

| Item |

Question |

| Mindset |

If there are conversations and discussions about new technologies in my environment, I am interested in them. |

| Mindset |

If someone tells me about new ideas to use technology, I am open to them |

| Mindset |

If there are new technologies or tools that make my work easier, I want to know more about it. |

| Behaviour |

I watch explanation videos (e.g., on youtube or other platforms) and/or read additional instructions to improve my knowledge. |

| Behaviour |

When I learn something new about digital technologies, I rethink my previous actions and try to develop them further with the new knowledge. |

| Behaviour |

If situations are changing, I adapt my decisions and activities regarding the use of digital technologies. |

| Improvement |

I acquire new knowledge and skills independently. |

| Improvement |

I am willing to invest time and money to integrate new technologies or processes in my daily live. |

| Improvement |

The knowledge I already have helps me to use other technologies |

References

- Kraus, S.; Schiavone, F.; Pluzhnikova, A.; Invernizzi, A. C. Digital Transformation in Healthcare: Analyzing the Current State-of-Research. J Bus Res, 2021, 123, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurenza, E.; Quintano, M.; Schiavone, F.; Vrontis, D. The Effect of Digital Technologies Adoption in Healthcare Industry: A Case Based Analysis. Business Process Management Journal, 2018, 24, 1124–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorella, G. L.; Fogliatto, F. S.; Mac Cawley Vergara, A.; Vassolo, R.; Sawhney, R. Healthcare 4.0: Trends, Challenges and Research Directions. Production Planning and Control, 2020, 31, 1245–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupeika-Apoga, R.; Petrovska, K. Barriers to Sustainable Digital Transformation in Micro-, Small-, and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Sustainability, 2022, 14, 13558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Onofrio, S. Der Digitale Wandel Im Gesundheitswesen. HMD Praxis der Wirtschaftsinformatik, 2022, 59, 1448–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G. L.; Peter, Z.; Rutter, K.-A.; Somauroo, A. Promoting an Overdue Digital Transformation in Healthcare. Ariel 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Iyanna, S.; Kaur, P.; Ractham, P.; Talwar, S.; Najmul Islam, A. K. M. Digital Transformation of Healthcare Sector. What Is Impeding Adoption and Continued Usage of Technology-Driven Innovations by End-Users? J Bus Res, 2022, 153, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivaldi, S.; Scaratti, G.; Fregnan, E. Dwelling within the Fourth Industrial Revolution: Organizational Learning for New Competences, Processes and Work Cultures. Journal of Workplace Learning, 2022, 34, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melhem, S., J. A. H. A Global Study on Digital Capabilities; 2021.

- Albort-Morant, G.; Leal-Rodríguez, A. L.; Fernández-Rodríguez, V.; Ariza-Montes, A. Assessing the Origins, Evolution and Prospects of the Literature on Dynamic Capabilities: A Bibliometric Analysis. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 2018, 24, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterby-Smith, M.; Prieto, I. M. Dynamic Capabilities and Knowledge Management: An Integrative Role for Learning? British Journal of Management, 2008, 19, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Araque, B.; Moreno-Garcia, J.; Hernández-Perlines, F. Editorial: Training, Performance, and Dynamic Capabilities: New Insights from Absorptive, Innovative, Adaptative, and Learning Capacities. Front Psychol, 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augier, M.; Teece, D. J. Understanding Complex Organization: The Role of Know-How, Internal Structure, and Human Behavior in the Evolution of Capabilities. Industrial and Corporate Change, 2006, 15, 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, J. T. The Management of Resources and the Resource of Management. J Bus Res, 1995, 33, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollo, M.; Winter, S. G. Deliberate Learning and the Evolution of Dynamic Capabilities. Organization science, 2002, 13, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossan, M. M.; Lane, H. W.; White, R. E. An Organizational Learning Framework: From Intuition to Institution. Academy of management review, 1999, 24, 522–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, R.; Ferreira, J. J.; Simões, J. Understanding Healthcare Sector Organizations from a Dynamic Capabilities Perspective. European Journal of Innovation Management, 2023, 26, 588–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pablo, A. L.; Reay, T.; Dewald, J. R.; Casebeer, A. L. Identifying, Enabling and Managing Dynamic Capabilities in the Public Sector*. Journal of Management Studies, 2007, 44, 687–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belliger, A.; Krieger, D. J. The Digital Transformation of Healthcare. Knowledge management in digital change: New findings and practical cases, 2018; 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin, C.; Katz, L. F. The Race between Education and Technology; harvard university press, 2009.

- Teece, D. J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strategic Management Journal, 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, F.; Bach, N. Evolutionary and Ecological Conceptualization of Dynamic Capabilities: Identifying Elements of the Teece and Eisenhardt Schools. Journal of Management & Organization, 2015, 21, 701–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K. M.; Martin, J. A. Dynamic Capabilities: What Are They? Strategic management journal, 2000, 21, (10–11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, I. Dynamic Capabilities: A Review of Past Research and an Agenda for the Future. J Manage, 2010, 36, 256–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Selen, W. The Incremental and Cumulative Effects of Dynamic Capability Building on Service Innovation in Collaborative Service Organizations. Journal of Management & Organization, 2013, 19, 521–543. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, K. S. R.; Wäger, M. Building Dynamic Capabilities for Digital Transformation: An Ongoing Process of Strategic Renewal. Long Range Plann, 2019, 52, 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellström, D.; Holtström, J.; Berg, E.; Josefsson, C. Dynamic Capabilities for Digital Transformation. Journal of Strategy and Management, 2022, 15, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, T.; Schallmo, D.; Kraus, S. Strategies for Digital Entrepreneurship Success: The Role of Digital Implementation and Dynamic Capabilities. European Journal of Innovation Management, 2024, 27, 198–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandewalle, D. Development and Validation of a Work Domain Goal Orientation Instrument. Educ Psychol Meas, 1997, 57, 995–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S.; Yeager, D. S. Mindsets: A View From Two Eras. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2019, 14, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. Mindset-Updated Edition: Changing the Way You Think to Fulfil Your Potential; Hachette UK, 2017.

- Rhew, E.; Piro, J. S.; Goolkasian, P.; Cosentino, P. The Effects of a Growth Mindset on Self-Efficacy and Motivation. Cogent Education, 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossan, M. M.; Lane, H. W.; White, R. E.; Djurfeldt, L. ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING: DIMENSIONS FOR A THEORY. The International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 1995, 3, 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterby-Smith, M.; Crossan, M.; Nicolini, D. Organizational Learning: Debates Past, Present And Future. Journal of Management Studies, 2000, 37, 783–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, D. W. Validating Instruments in MIS Research. MIS quarterly, 1989; 147–169. [Google Scholar]

- Tsang, S.; Royse, C.; Terkawi, A. Guidelines for Developing, Translating, and Validating a Questionnaire in Perioperative and Pain Medicine. Saudi J Anaesth, 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mergel, I.; Edelmann, N.; Haug, N. Defining Digital Transformation: Results from Expert Interviews. Gov Inf Q, 2019, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuser, M.; Nagel, U. Expertlnneninterviews—Vielfach Erprobt, Wenig Bedacht: Ein Beitrag Zur Qualitativen Methodendiskussion; Springer, 1991.

- Colquitt, J. A.; Sabey, T. B.; Rodell, J. B.; Hill, E. T. Content Validation Guidelines: Evaluation Criteria for Definitional Correspondence and Definitional Distinctiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 2019, 104, 1243–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, V. A.; Reynolds, W. W.; Ittenbach, R. F.; Luce, M. F.; Beauchamp, T. L.; Nelson, R. M. Challenges in Measuring a New Construct: Perception of Voluntariness for Research and Treatment Decision Making. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 2009, 4, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sireci, S. G.; Faulkner-Bond, M. Validity Evidence Based on Test Content. Psicothema, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D. F.; Beck, C. T.; Owen, S. V. Is the CVI an Acceptable Indicator of Content Validity? Appraisal and Recommendations. Res Nurs Health, 2007, 30, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paisant, A.; Skehan, S.; Colombié, M.; David, A.; Aubé, C. Development and Validation of Core Entrustable Professional Activities for Abdominal Radiology. Insights Imaging, 2023, 14, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, K.; Storey, V. C. Empirical Test Guidelines for Content Validity: Wash, Rinse, and Repeat until Clean. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 2020, 47, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J. Explicating Dynamic Capabilities: The Nature and Microfoundations of (Sustainable) Enterprise Performance. Strategic Management Journal, 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K. M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Academy of Management Review, 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almanasreh, E.; Moles, R.; Chen, T. F. Evaluation of Methods Used for Estimating Content Validity. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 2019, 15, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkin, T. R.; Tracey, J. B. An Analysis of Variance Approach to Content Validation. Organ Res Methods, 1999, 2, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P. M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling, 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the Fit of Structural Equation Models: Tests of Significance and Descriptive Goodness-of-Fit Measures. Methods of psychological research online, 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hail, M.; Zguir, M. F.; Koç, M. Exploring Digital Learning Opportunities and Challenges in Higher Education Institutes: Stakeholder Analysis on the Use of Social Media for Effective Sustainability of Learning–Teaching–Assessment in a University Setting in Qatar. Sustainability, 2024, 16, 6413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, K. Future of Undergraduate Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Impact of Perceived Flexibility and Attitudes on Self-Regulated Online Learning. Sustainability, 2024, 16, 6444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S. G. Understanding Dynamic Capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 2003, 24, 991–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, F. Dynamic Capabilities: A Retrospective, State-of-the-Art, and Future Research Agenda. Journal of Management & Organization. [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, D.; Barnard, H.; Dunne, D. Exploring the Everyday Dynamics of Dynamic Capabilities; 3rd Annual MIT/UCI Knowledge and Organizations Conference, Laguna Beach, CA, 2004.

- Dörner, O.; Rundel, S. Organizational Learning and Digital Transformation: A Theoretical Framework. In Digital Transformation of Learning Organizations; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colli, M.; Stingl, V.; Waehrens, B. V. Making or Breaking the Business Case of Digital Transformation Initiatives: The Key Role of Learnings. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 2022, 33, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, N. Digital Transformation and Organizational Learning: Situated Perspectives on Becoming Digital in Architectural Design Practice. Front Built Environ, 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.; Bose, I. Strategic Learning for Digital Market Pioneering: Examining the Transformation of Wishberry’s Crowdfunding Model. Technol Forecast Soc Change, 2019, 146, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, U.; Braathen, P.; Hannola, L. When and How the Implementation of Green Human Resource Management and Data-driven Culture to Improve the Firm Sustainable Environmental Development? Sustainable Development, 2023, 31, 2726–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Hong, A.; Song, H.-D. The Relationships of Family, Perceived Digital Competence and Attitude, and Learning Agility in Sustainable Student Engagement in Higher Education. Sustainability, 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Zhao, G.; Su, K. The Fit between Environmental Management Systems and Organisational Learning Orientation. Int J Prod Res, 2014, 52, 2901–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Song, H.-D.; Hong, A. Exploring Factors, and Indicators for Measuring Students’ Sustainable Engagement in e-Learning. Sustainability, 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjin A Tsoi, S. L. N. M.; de Boer, A.; Croiset, G.; Koster, A. S.; van der Burgt, S.; Kusurkar, R. A. How Basic Psychological Needs and Motivation Affect Vitality and Lifelong Learning Adaptability of Pharmacists: A Structural Equation Model. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 2018, 23, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbes, D.; Gedera, D.; Hartnett, M.; Datt, A.; Brown, C. Sustainable Strategies for Teaching and Learning Online. Sustainability, 2023, 15, 13118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamitri, I.; Kitsios, F.; Talias, M. A. Development and Validation of a Knowledge Management Questionnaire for Hospitals and Other Healthcare Organizations. Sustainability, 2020, 12, 2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, W. E.; Sinkula, J. M. The Synergistic Effect of Market Orientation and Learning Orientation on Organizational Performance. J Acad Mark Sci, 1999, 27, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).