1. Introduction

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) has been included in the fifth text revised edition of the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as a condition that may be the focus of clinical attention (DSM-5-TR) [

1], with NSSI being defined as intentional, self-initiated damage to the surface of the body (e.g., cutting, hitting, skin abrasion) in the absence of suicidal intent. Global estimates of prevalence rates for NSSI range from 4% to 23% for adults, with comparative rates for non-clinical samples of adolescents being somewhat higher at 13.9% to 28.6% [

2,

3]. It is generally acknowledged that NSSI constitutes a serious clinical and public health problem, as NSSI has been found to be associated with a variety of mental health problems – including depression, anxiety, borderline personality disorder, and eating disorders [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8] – and has been found to constitute a risk factor for suicidal behaviour [

9,

10,

11]. As such, research on risk factors for NSSI would appear to be strongly indicated, with available literature suggesting that risk factors for NSSI stem from: exposure to various forms of childhood trauma, comorbidity of NSSI with many other disorders, and the various functions of NSSI [

2].

It is also important to note that estimates of the prevalence and dynamics of NSSI have been found to vary across countries and continents [

3]. However, such variations have been reported almost exclusively in relation to countries located in the Global North; with two recent meta-analyses of NSSI prevalence rates [

3,

12] including only two studies that were conducted in the Global South (one in Brazil and one in Australia) but no studies that were conducted in the African context. As such, there would appear to be a clear need for global estimates of NSSI prevalence rates and dynamics to be expanded to reflect a more truly global perspective, with such expansion appearing to be most strongly indicated in relation to the African context.

1.1. Childhood Adversity as a Risk Factor for NSSI

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) include a range of potentially traumatic experiences, occurring before the age of 18, that have been found to be associated with a cumulative risk for compromised physical, behavioural, mental, and social health [

13,

14]. Although exposure to ACEs has consistently been found to constitute a risk factor for NSSI [

2,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20] available studies have tended to construe ACEs somewhat narrowly, with the assessment of ACEs having largely been restricted to direct acts of child maltreatment occurring in the home (i.e., physical, emotional, sexual abuse, and/or neglect) and to adverse family circumstances (parental divorce or separation, mother treated violently, family member incarcerated, substance abuse in the home, and mental illness or suicide attempts in the home) . As a result, we have little understanding of the association between NSSI and: (a) children’s indirect exposure to ACEs in the home (e.g., witnessing domestic violence) that have been found to be associated with compromised physical and mental health outcomes [

21] or (b) children’s exposure to potentially traumatic extrafamilial ACES (e.g., exposure to community violence or peer victimization) that have been found to be associated with deleterious physical and mental health outcomes [

22].

Although child and adolescent exposure to discrimination (racial, sexual orientation, sexual identity) has seldom been conceptualised as an ACE, available evidence would suggest that discrimination has a stronger effect on mental health and executive functioning outcomes than conventional ACEs [

23,

24], with findings from studies conducted in high-income countries suggesting that discrimination is strongly associated with NSSI [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Further, despite the democratic elections of 1994, racial and other forms of discrimination continue to constitute a major public health concern in South Africa [

29], with there being an associated need to explore the heuristic value of including discrimination as an additional ACE when assessing risk factors for NSSI in both low- to middle-income and high-income countries.

1.2. Mechanisms Underlying the Association Between ACEs and NSSI

There is an emerging body of research which suggests that there are two related, although somewhat distinct, pathways between ACEs and NSSI. First, from a neurobiological perspective, there is substantial support for the view that repeated exposure to ACEs is linked to changes in brain functioning and structure and in stress-response neurobiological systems, with these changes having been found to be associated with enduring effects on an individual’s physical and mental wellbeing as well as with deficits in emotional regulation (ED) and executive functioning [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Taken together, this perspective would predict a direct effect of ACEs on the development of mental disorders (such as NSSI) as well as a direct effect of ACEs on (ED) and impaired executive functioning.

A second and related pathway between ACES and NSSI, is suggested by the psychological theories of Chapman et al. and Nock [

35,

36], that attempt to account for why and how distress and ER associated with ACEs gives rise to NSSI behaviours. According to these theories the primary function of NSSI is to address uncomfortable emotional feelings (including ED) associated with a number of mental disorders, including depression and PTSD [

37], with NSSI having been found to constitute an effective and efficient method of regulating affective and cognitive experiences associated with childhood trauma [

38]. These psychological theories would predict that the association between ACEs and NSSI are likely to be mediated by feelings of distress and/or ED.

Empirical support for both neurobiological and psychological pathways to NSSI has been reported in a number of studies. With respect to the neurobiological model, available studies have consistently reported a direct effect of ACES on NSSI [

2,

14,

15,

17,

18,

19,

39,

40] and a direct effect of ACEs on ED and/or emotional distress associated with PTSD and depression [

2,

41]. Similarly, with respect to the psychological model, studies have found that emotional distress and ED partially mediate the association between ACEs and NSSI [

39,

43].

1.3. Research on Factors Mediating the Association between ACEs and NSSI

We were able to identify seven studies that have examined mediators of the ACEs-NSSI association [

19,

38,

39,

40,

42,

43,

44]; with potential mediators considered in these studies being consistent with predictions suggested by contemporary conceptualizations of NSSI (i.e., ED, depression, and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder). Six studies considered ED as a potential mediator of the ACE-NSSI association, with ED being found to constitute a significant mediator or moderator of NSSI severity in 5 studies [

38,

39,

42,

43,

44] but not in the study conducted by Shenk and associates [

40]. The mediating effects of depression on NSSI severity were examined in five studies, with depression being found to mediate NSSI outcomes in four studies, [

19,

38,

39,

42] but not in one study [

40]. Finally, only one study [

41] assessed the mediating effects of PTSD, with PTSD symptoms emerging as a significant mediator of NSSI severity, but with depression and ED not significantly mediating NSSI severity after controlling for PTSD.

Disparities in available studies may reflect differences in study design. With respect to sampling strategies, study participants were drawn from the general community in five studies [

19,

38,

39,

42,

44], with the mediating effects on NSSI outcome being assessed in a clinical sample of adolescents in one study [

43] and a sample drawn from Child Protection Services referrals in another study [

40]. Further, there was a lack of consistency regarding the role played by key variables in relation to NSSI outcomes. Although ED and depression were generally conceptualized as constituting mediating variables, ED was entered as a moderating variable in one study [

38], with depression being entered in another study as a control variable [

42].

In interpreting available mediational findings it is also important to bear in mind that there were marked differences across studies in the way that NSSI was operationalised, with some studies employing validated research instruments in order to obtain an estimate of NSSI severity (19,38,39,42,43], and two studies [

40,

44] relying exclusively on one or two broad questions to asses for NSSI (e.g., “Have you ever tried to intentionally hurt yourself by damaging the physical integrity of your body”). Clearly such broad questions fail to adequately address the nature and scope of NSSI as defined by the American Psychiatric Association [

1].

At a broader level, available mediation studies have been conducted exclusively in two continents – North America [

38,

40,

43] and Asia [

19,

39,

42,

44] – and have been conducted among participants residing in middle income countries [

19,

39,

44] or in high income-countries [

38,

40,

42,

43]; with none of the identified mediation studies having been conducted in countries located in the Global South. To the extent that estimates of the prevalence and dynamics of NSSI have been found to vary across countries and continents [

3], it is possible that disparities in mediation findings may also reflect geographic and/or income level variations across study samples.

In sum, available mediation studies are characterized by marked heterogeneity in sampling and design, with inter-study variability serving to limit the confidence with which cross-study comparisons can meaningfully be made.

1.4. The Present Study

The broad aim of the present research was to conduct a study on the association between ACEs and NSSI in a non-clinical sample of adolescents living in a in a low-resourced African country, and to assess the extent to which study findings correspond to trends that have emerged in the extant literature. In addition to assessing comparative prevalence rates for ACEs and NSSI, the study was designed to explore potential mediators of the ACEs-NSSI association, with the selection of potential mediators in this study being informed by both conceptual and empirical considerations. As we have indicated above, contemporary conceptualisations of risk factors for NSSI are united in regarding ED as well as general psychological distress (including symptoms of depression and PTSD) as being important mediators of NSSI outcomes [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]; with empirical support for the mediating role of ED, depression, and PTSD being suggested by findings from the limited number of studies that have been conducted on the topic [

19,

38,

39,

40,

42,

43,

44].

As such, in this study it was predicted that the impact of risk factors for NSSI outcomes would be mediated by ED, depressive symptoms, and symptoms of PTSD; with the conceptual model employed in the study being presented in

Figure 1.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The convenience sample used in this study included all 734 students attending a South African secondary school. Six hundred and thirty-six participants (86.6%) completed usable questionnaires, with sample attrition being due to: an absence of written consent/assent (n =57, 7.8%), extensive missing data (n =25, 3.4%), and participant voluntary withdrawal from the research during questionnaire completion (n = 16, 2.2%). An examination of school records indicated that participants did not differ significantly from non-participants in terms of age, ethnicity, and gender. Sample demographics were: female (34.4%), age (12-18 years, Mage = 15.4, SD = 1.5), and ethnicity (96.0% Black African), with participant numbers being more or less equivalent across grade levels.

2.3. Procedure

The study was conducted in an urban co-educational public high school in the Durban Metropolitan region (South Africa). The school selected for the research was chosen not simply for convenience purposes but largely because school staff had identified a specific problem area (learner behavioural and psychological problems) that they felt could, at least to some extent, be addressed by the research. Prior to questionnaire administration, a meeting was held with the school principal and staff to outline the nature and purpose of the research. School staff were enthusiastic about the research and agreed to arrange a special school assembly to inform students regarding what their participation would involve with the voluntary nature of participation being emphasized. Students were then provided with informed consent forms to be completed by caretakers, with those who obtained caretaker consent being invited to complete an assent form. In cases where caretaker consent and child assent were provided, students were invited to complete a research questionnaire. Questionnaires were administered to whole classes of students during Life Orientation classes, with the researchers and Life Orientation teacher being present to assist with any queries participants may have and to monitor participants for possible distress. In cases where distress was noted, participants were provided with an option of discontinuing their participation.

2.2. Measures

ACEs were assessed using a revised version of the ACEs Questionnaire (ACES-R) [

22], that contains 5 items relating to child maltreatment, 5 items relating to adverse family circumstances, and 4 items relating to broader contextual issues (low socioeconomic status, peer victimization, social isolation, and witnessing community violence). Although the ACES-R has not previously been used with South African samples, the scale has been found to be associated with enhanced predictive validity in a large and representative sample of adolescents in the United States [

22]. For purposes of the study, an additional ACE (discrimination) was added to the ACE-R, with

discrimination being operationalised using an item adapted from the Daily Discrimination Scale (DDS) [

45], “Before your 18

th birthday, were you

often or very often called names, insulted, or threatened because of your race, skin colour, sexual orientation, or sexual identity?” (0 = No, 1 = Yes to any form of discrimination). Given that ACE questionnaires are primarily designed to measure the confluence of multiple types of ACEs [

21], ACEs in this study were assessed using a cumulative measure of ACEs (i.e., the total number of ACEs reported by participants), with potential scores ranging from 0-15.

NSSI was assessed using an adapted version of the Self-Harm (SH) subscale of the Risk-Taking and Self-Harm Inventory for Adolescents (RTSHIA) [

46], that has previously been used in studies of South African adolescents [

47]. In Vrouva and colleague’s validation study [

46] the SH subscale was found to have a high level of internal validity (α = .93) and acceptable levels of 3-month test-retest reliability (r = ,87), as well as acceptable levels of convergent, concurrent, and divergent validity (α = .86 in the present study). The SH subscale contains eight statements relating to intentional NSSIs (e.g., cutting, burning, biting, skin abrasion), with each statement beginning with the phrase “have you ever intentionally…”, with frequencies being rated on a 4-point scale ranging from

never to

many times Consistent with recommendations that NSSI behaviours are likely to be most clinically meaningful if they occurred in the past year [

6], each item on the SH subscale was adapted to assess past-year NSSI behaviours. For each item on the SH subscale, participants were asked to indicate the number of days that they had engaged in such behaviour in the past 12-months. Each item on this adapted version of the RTSHIA was scored using a 4-point scale (

never to

many times in the past year), providing a score range of 0-24.

ED was assessed using the 6-item Alteration in Regulation and Affect (ARA) subscale of the self-report version of the Structed Interview for Disorders of Extreme Stress Scale (SIDES-SR) [

48] that has previously been used in research on South African adolescents [

49]. Research on the ARA indicates that the scale has high levels of internal consistency (α = .82), with Cronbach alpha in this study being .80. The ARA provides a symptom severity score for ED ranging from 0-24.

Symptoms of depression were assessed using a nine-item subscale of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) that is used to assess for the severity of depressive symptoms [

50]. The PHQ-9, that has been validated in samples of South African adolescents [

51], has been widely validated, with Cronbach alpha across three trials ranging from .86-.89 [

50], and with alpha in this study being .86. Each of the nine items on the PHQ-9 questionnaire are scored using a 4-point Likert scale that assess how often individuals have been bothered by depressive symptoms in the past two weeks. with response options ranging from 0 (

not at all) to 3 (

nearly every day), providing an estimate of symptom severity ranging from 0-27.

The severity of PTSD symptoms was assessed using the 20-item Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Checklist for DSM-V (PCL-5) [

52], that has previously been used in research on young adults in South Africa [

53]. Blevins and colleagues report high levels of convergent and discriminative validity for the scale as well as strong internal consistency (α = 0.94) [

48]. In this study Cronbach alpha was .92. Items on the PCL-5 are scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely), providing a score range of 0-80., and with a score of 33 or more representing clinically significant levels of PTSD symptoms.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

An institutional ethical clearance certificate was obtained for the research (protocol reference number: HSS/1029/013D). In addition, written gatekeeper permission from the school principal, parental consent, and participant assent were obtained; with continuous assent being employed to ensure that students could discontinue their participation at any time, and with offers of free supportive counselling from the school counselor being made to all participants.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The data analysis involved three stages. Initially data were reviewed, with this review revealing that the proportion of missing values was less than 3% across all study variables, which can be considered negligible as it falls well below the 5% rule of thumb for acceptable levels of missing data [

54]. As such, for each analysis, listwise deletion was used to handle missing values. The data review also revealed that there were no outliers.

Second, prevalence rates were calculated for ACEs and NSSI, with descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations and intercorrelations) being calculated for all key variables. Finally, a multi mediation analysis was conducted using the PROCESS macro for SPSS [

55]. After controlling for the effects of demographic variables (age gender, and ethnicity): (a) the risk factor entered in this analysis was a cumulative measure of ACEs exposure (i.e., the number of different types of ACE reported by each participant); (b) the outcome variable being the severity of NSSI; and (c) the mediating variables being the severity of ED, depressive, and PTSD symptoms; and d) with bootstrapped confidence intervals (CI), based on 5000 bootstrapped samples, being used to determine the significance of indirect effects.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Of the 636 participants included in the study, 211 (33.2%, SE =.02) reported that they had engaged in NSSI behaviours on at least five days in the past year. The three most frequently reported forms of NSSI were: “cut your skin” (23.3%, SE = .04), “banged your head against a hard surface” (19.7%, SE = .04), and “burned yourself with a hot object” (9.1%, SE = .02). Prevalence rates for NSSI were higher among 12-14-year-old participants (42.2%, SE = .04) than among 15-18-year-olds (29.1%, SE = .04; χ21df = 10.66, p = .001), with participant sex and ethnicity being unrelated to NSSI prevalence rates.

Five hundred and ninety-three participants (93.2%) reported lifetime exposure to at least one ACE, with 187 (29.4%) reporting exposure to five or more ACEs. The four types of ACEs that were most strongly associated with NSSI severity were: discrimination (

b = 0.75, SE = 0.2), domestic physical abuse (

b = 0.69, SE = .02), peer victimization (

b = 0.67. SE = .02), and sexual abuse in the home (

b = 0.53, SE = 0,12). Additional descriptive statistics for continuous variables are presented in

Table 1.

3.2. Mediation Analysis

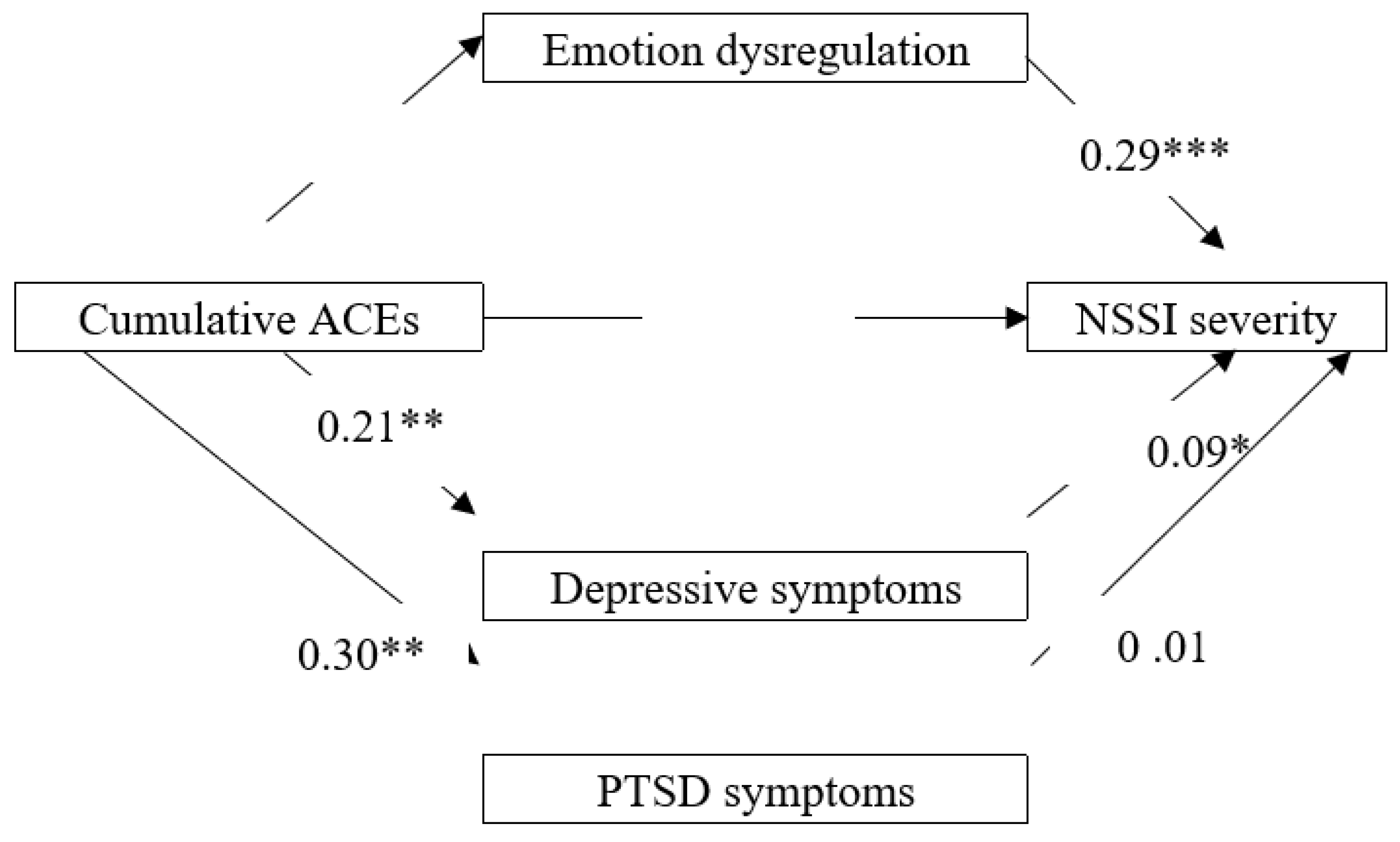

The mediation model was tested and the results are presented in

Figure 2. ACEs were positively and significantly associated with: ED (

b = 0.23, SE = 0.03,

p <.001), depression (

b =0.21, SE = 0.03,

p = <.001), PTSD (

b = 0.30, SE =0.23,

p <.001), and NSSI (

b = 0.28, SE 0.02,

p < .001). In addition, NSSI was positively and significantly associated with ED (

b = 0.29, SE =0.08,

p < .001) and depression, (

b = 0.09, SE = 0.07,

p = .033), but not with PTSD (

b = 0.01, SE = 0.01,

p = .898). The mediation analysis revealed a positive and significant indirect effect of ACEs on NSSI through ED (effect = 0.29, CI: .0149, .0484), but no significant indirect effect for depression (effect = 0.15, CI = -.0649, .0288), or PTSD (effect = -.041, CI = -.0012, .0152). The direct effect of ACEs on NSSI in the presence of all mediators was also found to be significant (

b =.015, SE =.03, p <.001). Taken together, these findings indicate that ED partially mediated the relationship between ACEs and NSSI.

4. Discussion

The primary aim of this research was to explore the mediating role of emotion regulation, depression, and PTSD on the association between ACEs and NSSI in a non-clinical sample of South African adolescents, and to assess the extent to which study findings correspond to findings that have been reported in studies conducted largely in the Global North (mainly in Asia and North America).

With respect to prevalence rates, the present findings suggest that both ACEs and NSSI are highly prevalent among South African adolescents. Of the 636 participants in this study, 593 (93.2%) reported exposure to at least one ACE, with 187 (29.4%) reporting exposure to five or more ACEs. Although these prevalence rates are similar to rates reported in previous studies of low- to middle-income countries [

59,

60] they are markedly higher than comparative rates reported for high-income countries [

61,

62]. Regarding the prevalence of NSSI, one in three participants (33.2%) reported that they engaged in NSSI on at least five occasions in the past year. These prevalence rates are notably higher than the 12-month global prevalence rate of 23% for repetitive NSSIs reported for non-clinical samples of adolescents [

3] and fractionally higher than comparative 12-month prevalence rates of 15.5% to 31.3% reported for low- to middle-income countries [

63]. Taken together, these high prevalence rates for both ACEs and NSSI suggest that adolescents living in Africa (and in other low-to middle income countries) face a comparatively higher risk of exposure to both ACEs and NSSI; with there being an associated need for primary, secondary, and tertiary intervention programmes designed to effectively address both the prevalence and consequences of both ACEs and NSSI in low-resourced countries.

Study findings indicate that the association between ACEs and NSSI is partially mediated by ED, with higher levels of ED being associated with increased NSSI severity. These findings are consistent with neurobiological theories which posit that ACEs will be associated with the severity of both ED and NSSI [

32], and consistent with psychological theories that predict that the association between ACEs and NSSI will be mediated by emotion regulation [

36]. As such, study findings suggest that both theoretical perspectives may need to be considered when considering pathways to NSSI.

The finding that ED partially mediated the ACEs-NSSI association is congruent with findings from previous studies, conducted in both middle- and high-income countries, that have identified ED as one of the strongest mediators of the ACE-NSSI association [

38,

39,

42,

43,

44]. As such, comprehensive NSSI interventions, designed to address both the direct effects of ACES and the indirect effects of ED on NSSI outcomes, would appear to be indicated. In this regard, multi-phase interventions, such as trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy [

56] – that focus initially on safety and addressing ED before going on to address traumatic events – have been found to be more effective than single-phase interventions (that focus exclusively on addressing traumatic events), with this enhanced efficacy having been found to be most marked among children and youth [

57].

The fact that there was a significant direct association between ACEs and NSSI in the presence of selected mediators suggests that there may be additional mediators that could usefully be explored in future studies, with available studies suggesting a number of additional variables that could usefully be considered, including: female gender [

18], LGBTQI+ status [

28], dissociation [

34], and self-compassion [

19]. Further, research on potentially traumatic life events that are prolonged and/or repetitive in nature have identified a trio of disorders of self-organization (DOS) that are associated with chronic exposure to ACES, with DOSs comprising: (a) severe and prolonged problems with affect regulation, (b) persistent beliefs about the self as being diminished or worthless, and (c) difficulties in sustaining relationships or feeling close to others [

53]. While the present study provides support for the mediating effects of affect dysregulation, further research could usefully explore the mediating effects of all three DOSs.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Study Findings

To a large extent, findings relating to the prevalence and dynamics of ACES and NSSI were consistent with findings reported in the extant literature. For example: (a) high prevalence rates for ACEs and NSSI observed in this study are consistent with the view that adolescents living in low-resourced countries face a higher risk of exposure to both ACEs and NSSI [

58,

63], and (b) the finding that ED most strongly mediated the ACE-NSSI association is consistent with findings from previous studies conducted in both medium- and high-income countries [

19,

38,

39,

42,

43,

44] that have identified ED as a significant mediator of NSSI risk. However, the fact that depression and PTSD were not found to mediate NSSI severity after controlling for ED was not anticipated, with this finding appearing to be worthy of further study.

5.2. Implications for Theory and Prevention

Study findings would appear to have implications for both theory and intervention. With regard to theory, study findings are consistent with Kira’s development-based trauma framework [

23,

24], in terms of which trauma severity is evaluated in terms of three trauma types: Type I (single traumatic exposure); Type II (a sequence of events that occurred and then stopped); and Type III (continuous traumatic exposure that can continue throughout life); with there being compelling evidence that Type III traumas have the most severe traumagenic potential [

23]. As such it is hardly surprising that in this study

discrimination (a Type III trauma) was more strongly associated with NSSI severity than predominantly Type I and II traumas that are assessed in standard ACE measures. It is similarly not surprising that ED, a condition that has been found to be strongly associated with chronic/continuous types of traumatic exposure [

58], emerged as a significant mediator of NSSI severity in this study. The fact that Type III traumas have been found to be highly prevalent in low resourced countries such as South Africa [

64], with a history of discrimination having been found to be associated with NSSI in studies conducted in low-, middle-, and high-income countries [

65,

66,

67], suggesting that discrimination is an ACE that may have global relevance.

The fact that both ACEs and NSSI were found to be highly prevalent in this sample suggests the need for primary prevention efforts designed to reduce levels of ACEs exposure (e.g., cash and kind transfers or home visitation programs) and/or to foster resilience among children; with available evidence suggesting that efforts to bolster children’s resilience need to be targeted at individual factors such as self-esteem and self-compassion [

19,

68] as well as at efforts to increase social capital at a domestic, peer, and community level [

69,

70,

71]. With respect to secondary and tertiary prevention, there are a variety of interventions that have been specifically designed to address the direct and/or indirect effects of cumulative exposure to ACEs, with such interventions including emotion regulation therapy [

72] and trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy [

56]. Similarly, there are a number of psychotherapeutic interventions that have been found to be effective in treating NSSI among adolescents; with the most effective interventions, in terms of reducing NSSI behaviors, being interventions that use strategies from (or adapted from) Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Dialectical Behavior Therapy and/or Psychoeducation [

73].

5.3. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

To our knowledge, this is the first study of factors mediating the association between ACES and NSSI to be conducted on the African continent, with study findings suggesting that both ACEs and NSSI are highly prevalent in low-resourced settings, and that ED is an important mediator of the ACE-NSSI association. Limitations of the study include the fact that data were obtained using a cross-sectional design that precludes strong causal inferences, and using a questionnaire that relied on retrospective recall in relation to key constructs that may have been associated with recall bias. As such, future research on the association between ACEs and NSSI needs to ideally rely on prospective methods of data collection that are designed to address these limitations. In addition, the use of self-report measures of participants wellbeing falls short of the gold standard for assessing psychological wellbeing (i.e., a comprehensive clinical assessment). As such, future studies on the association between ACEs and NSSI would benefit from a reliance on a more comprehensive assessment of key constructs. Finally, male and Black African participants were over-represented in the study sample, which could potentially limit the generalizability of study findings. As such, further research, based on more demographically representative samples, is indicated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, SC and SV; Formal analysis, SC; Investigation, SV; Methodology, SC and SV; Writing – original draft, SC; Writing – review & editing, SC and SV.

Funding

The authors declare that no funding was received for this research

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Humanities and Social Science Research Ethics Committee at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (HSS/1029/013D). Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the principal of the study school.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants obtained caregiver consent to participate and provided written informed assent.

Data Availability Statement

School authorities did not pride consent for us to share the data with any third parties.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Text Revised ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cipriano, A.; Cella, S.; Cotrufo, P. Non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Song, X.; Huang, L.; Hou, D.; Huang, X. Global prevalence and characteristics of non-suicidal self-injury between 2010 and 2021 among a non-clinical sample of adolescents: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 912441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratz, K.L.; Tull, M.T. Exploring the relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder and deliberate self-harm: The moderating roles of borderline and avoidant personality disorders. Psychiat. Res. 2012, 119, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaess, M.; Parzer, P.; Mattern, M.; Plener, P.L.; Bifulco, A.; Resch, F.; Brunner, R. Adverse childhood experiences and their impact on frequency, severity, and the individual function of nonsuicidal self-injury in youth. Psychiat. Res. 2013, 206, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiekens, G.; Hasking, P.; Claes, L.; Mortier, P.; Auerbach, R.P.; Boyes, M.; Cuijpers, P.; Demyttenaere, K.; Green, J.G.; Kessler, R.C.; Nock, M.K.; Bruffaerts, R. The DSM-5 nonsuicidal self-injury disorder among incoming college students: Prevalence and associations with 12-month mental disorders and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Depress. Anxiety 2018, 35, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, F.; Webb, R.T.; Wittkowski, A. Risk factors for self-harm repetition in adolescents: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Review. 2021, 88, 102048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, M.N.; Dimitropoulos, G.; Ramirez, A.; McPherson, C.; Anderson, A.; Munir, A.; Patten, S.B.; McGirr, A.; Devoe, D.J. Non-suicidal self-injury, suicidal thoughts and behaviors in individuals with an eating disorder relative to healthy and psychiatric controls: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 56, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Bandeira, B.E.; dos Santos Júnior, A.; Dalgalarrondo, P.; de Azevedo, R.C.S.; Celeri, E.H.V.R. Nonsuicidal self-injury in undergraduate students: A cross-sectional study and association with suicidal behaviour. Psychiat. Res. 2022, 318, 114917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griep, S.K.; MacKinnon, D.F. Does nonsuicidal self-injury predict later suicidal attempts? A review of studies. Arch. Suicide. Res. 2022, 26, 428–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Z.; Xiong, F.; Li, W. A meta-analysis of co-occurrence of non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempt: Implications for clinical intervention and future diagnosis. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 976217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moloney, F.; Amini, J.; Sinyor, M.; Schaffer, A.; Lanctôt, K.L.; Mitchell, R.H.B. Sex differences in the global prevalence of nonsuicidal self-Injury in adolescents: A meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2415436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, Z.I.; Koyanagi, A.; Stewart-Brown, S.; Perry, B.D.; Marmot, M.; Koushede, V. Cumulative risk of compromised physical, mental and social health in adulthood due to family conflict and financial strain during childhood: A retrospective analysis based on survey data representative of 19 European countries. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e004144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahali, K.; Durcan, G.; Topal, M.; Önal, B.; Bilgiç, A.; Tanıdır, C.; Aytemiz, T.; Yazgan,Y.; Parental attachment and childhood trauma in adolescents engaged in non-suicidal self-injury. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2024, 18, 173-180. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.Y.; Liu, J.; Zeng, Y.Y.; Conrad, R.; Tang, Y.L. Factors associated with non-suicidal self-injury in Chinese adolescents: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 747031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laporte, N.; Ozolins, A.; Westling, S.; Westrin, A.; Wallinius, M. Adverse childhood experiences as a risk factor for non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts in forensic psychiatric patients. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, G.; Canepa, G.; Adavastro, G.; Nebbi, J.; Belvederi Murri, M.; Erbuto, D.; Pocai, B.; Fiorillo, A.; Pompili, M.; Flouri, E.; Amore, M. The relationship between childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 24, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Li, X.; Ng, C.H.; Xu, D.; Hu, S.; Yuan, T.F. Risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in adolescents: A meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 46, 101350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, S.; Luo, J.; Li, X.; You, J. The effects of childhood abuse, depression, and self-compassion on adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: A moderated mediation model. Child Abuse Neg. 2023, 136, 105993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Hu, C.; Wang, L. Maladaptive perfectionism and adolescent NSSI: A moderated mediation model of psychological distress and mindfulness. J. Clin. Psych 2022, 78, 1137–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarse, E.M.; Neff, M.R.; Yoder, R.; Hulvershorn, L.; Chambers, J.E.; Andrew Chambers, R. The adverse childhood experiences questionnaire: Two decades of research on childhood trauma as a primary cause of adult mental illness, addiction, and medical diseases. Cogent Med. 2019, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelhor, D.; Shattuck, A.; Turner, H.; Hamby, S.A. Revised inventory of adverse childhood experiences. Child Abuse Neg. 2015, 48, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kira, I.A. The Development-Based Taxonomy of stressors and traumas: An initial empirical validation. Psychology 2021, 12, 1575–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kira, I.A.; Lewandowski, L.; Templin, T.; Ramaswamy, V.; Ozkan, B.; Mohanesh, J. Measuring cumulative trauma dose, types, and profiles using a Development-Based Taxonomy of Traumas. Traumatology 2008, 14, 62–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batejan, K.L.; Jarvi, S.M.; Swenson, L.P. Sexual orientation and non-suicidal self-injury: A meta-analytic review. Arch. Suicide Res. 2015, 19, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán, C.A.; Stokes, L.R.; Szoko, N.; Abebe, K.Z.; Culyba, A.J. Exploration of experiences and perpetration of identity-based bullying among adolescents by race/ethnicity and other marginalized identities. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2116364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackman, K.; Honig, J.; Bockting, W. Nonsuicidal self-injury among lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender populations: An integrative review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 3438–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.T.; Sheehan, A.E.; Walsh, R F.L.; Sanzari, C.M.; Cheek, S.M.; Hernandez, E.M. Prevalence and correlates of non-suicidal self-injury among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 74, 101783. [CrossRef]

- Adonis, C.K. Exploring the salience of intergenerational trauma among children and grandchildren of victims of Apartheid-era gross human rights violations. Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology 2016, 16(1-2) 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Anda, R.F.; Felitti, V.J.; Bremner, J.D.; Walker, J.D.; Whitfield, C.; Perry, B.D.; Dube, S.R.; Giles, W.H. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 256, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, E.P.; Brawner, T.W.; Perry, B.D. Timing of early-life stress and the development of brain-related capacities. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2019, 3, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakama, N.; Usui, N.; Doi, M.; Shimada, S. Early life stress impairs brain and mental development during childhood increasing the risk of developing psychiatric disorders. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2023, 126, 10783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, B.D. The neurodevelopmental impact of violence in childhood. In Textbook of Child and Adolescent Forensic Psychiatry; Schetky, D., Jones, E.P., Eds.; American Psychiatric Press, Washington, DC, 2001; pp. 221-238.

- van der Kolk, B. The Body Keeps the Score. New York: Viking, 2014.

- Chapman, A.L.; Gratz, K.L.; Brown, M.Z. Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: The experiential avoidance model. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M.K. Why do people hurt themselves? New insights into the nature and functions of self-injury. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 18, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.J.; Jomar, K.; Dhingra, K.; Forrester, R.; Shahmalak, U.; Dickson, J.M. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of different functions of non-suicidal self-injury. J. Affect. Disorders 2018, 227, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X; Zhang, L. Childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents: Testing a moderated mediating model. J. Interpers. Violence 2024, 39, 925-948. [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Huang, J.; Shang, Y.; Huang, T.; Jiang, W.; Yuan, Y. Child maltreatment exposure and adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: The mediating roles of difficulty in emotion regulation and depressive symptoms. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2023, 17, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenk, C.E.; Noll, J.G.; Cassarly, J.A. A multiple mediational test of the relationship between childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010, 39, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragan, M. Adverse experiences, emotional regulation difficulties and psychopathology in a sample of young women: Model of associations and results of cluster and discriminant function analysis. Eur. J. Trauma Dissociation 2020, 4, 100091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peh, C.X.; Shahwan, S.; Fauziana, R.; Mahesh, M.V.; Sambasivam, R.; Zhang, Y.; Ong, S.H.; Chong, S.A.; Subramaniam, M. Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking child maltreatment exposure and self-harm behaviors in adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2017, 67, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titelius, E.N.; Cook, E.; Spas, J.; Orchowski, L.; Kivisto, K.; O'Brien, K.H.M.; Frazier, E.; Wolff, J.C.; Dickstein, D.P.; Kim, K.L.; Seymour, K. Emotion dysregulation mediates the relationship between child maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury. J. Aggress. Maltreat.Trauma 2018, 27, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiguna, T.; Minayati, K.; Kaligis, F.; Ismail, R.I.; Wijaya, E.; Murtani, B.J.; Pradana, K. The effect of cyberbullying, abuse, and screen time on non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents during the pandemic: A perspective from the mediating role of stress. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 743329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Yu, Y.; Jackson, J.S.; Anderson, N. B. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socioeconomic status, stress, and discrimination. J. Health Psycho. 1997, 2, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrouva, I.; Fonagy, P.; Fearon, P.R.; Roussow, T. The risk-taking and self-harm inventory for adolescents: Development and psychometric evaluation. Psychol. Assess. 2010, 22, 852–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduaran, C.; Agberotimi, S.F. Moderating effect of personality traits on the relationship between risk-taking behaviour and self-injury among first-year university students. Adv. Ment. Health 2021, 19, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelcovitz, D.; van der Kolk, B.; Roth, S.; Mandel, F.; Kaplan, S.; Resick, P. Development of a criteria set and a structured interview for disorders of extreme stress (SIDES). J. Trauma. Stress 1997, 10, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penning, S.L. Traumatic Re-enactment of Childhood and Adolescent Trauma: A Complex Developmental Trauma Perspective in a Non-Clinical Sample of South African School-Going Adolescents. Doctoral Dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, 2015. http://hdl.handle.net/10413/14619.

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marlow, M.; Skeen, S.; Grieve, C.M.; Carvajal-Velez, L.; Åhs, J.W.; Kohrt, B.A.; Requejo, J.; Stewart, J.; Henry, J.; Goldstone, D.; Kara, T.; Tomlinson, M. Detecting depression and anxiety among adolescents in South Africa: Validity of the isiXhosa Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7. J. Adolesc. Health 2023, 72, S52–S60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blevins, C.A.; Weathers, F.W.; Davis, M.T.; Witte, T.K.; Domino, J.L. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. J. Trauma. Stress 2015, 28, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, T.B.; Padmanabhanunni, A. Anxiety in brief: assessment of the five-item Trait Scale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory in South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakobsen, J.C.; Gluud, C.; Wetterslev, J.; Winkel, P. When and how should multiple imputation be used for handling missing data in randomised clinical trials - a practical guide with flowcharts. BMC Med, Res, Methodol. 2017, 17, 162. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modelling. 2012. http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

- Thornback, K.; Muller, R.T. Relationships among emotion regulation and symptoms during trauma-focused CBT for school-aged children. Child Abuse Negl. 2015, 50, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, R.J.; Taylor, E.P.; Cadavid, M.S. Phase-based psychological interventions for complex post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2023, 14, 100628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloitre, M.; Shevlin, M.; Brewin, C.R.; Bisson, J.I.; Roberts, N.P.; Maercker, A.; Karatzias, T.; Hyland, P. The International Trauma Questionnaire: Development of a self-report measure of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2018, 138, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, A.A.; Deb, S.; Malik, M.H.; Khan, W.; Haroon, A.P.; Ahsan, A.; Jahan, F.; Sumaiya, B.; Bhat, S Y.; Dhamodharan, M.; Qasim, M. Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) among young adults of Kashmir. Child Abuse Negl. 2022,134, 105876. Child Abuse Negl. [CrossRef]

- Manyema, M.; Richter, L.M. Adverse childhood experiences: prevalence and associated factors among South African young adults. Heliyon 2019, 5, e03003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broekhof, R.; Nordahl, H.M.; Bjørnelv, S.; Selvik, S.G. Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences and their co-occurrence in a large population of adolescents: A Young HUNT 3 study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 2359–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giano, Z.; Wheeler, D.L.; Hubach, R.D. The frequencies and disparities of adverse childhood experiences in the U.S. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Patton, G.; Reavley, N.; Sreenivasan, S.A.; Berk, M. Youth self-harm in low- and middle-income countries: Systematic review of the risk and protective factors. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2017, 63, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminer, D.; Eagle, G.; Crawford-Browne, S. Continuous traumatic stress as a mental and physical health challenge: Case studies from South Africa. J. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 1038–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, C.; Affuso, G.; Amodeo, A.L.; Dragone, M.; Bacchini, D. Bullying victimization: Investigating the unique contribution of homophobic bias on adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and the buffering role of school support. School Ment. Health 2021, 13, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muehlenkamp, J.J.; Hilt, L.M.; Ehlinger, P.P.; McMillan, T. Nonsuicidal self-injury in sexual minority college students: A test of theoretical integration. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2015, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X. Perceived discrimination, loneliness, and non-suicidal self-injury in Chinese migrant children: The moderating roles of parent-child cohesion and gender. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 2021, 38, 825–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Agudo, F.; Burcher, G.C.; Ezpeleta, L.; Kramer, T. Non-suicidal self-injury in community adolescents: A systematic review of prospective predictors, mediators and moderators. J. Adolesc. 2018, 65, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoffersen, M.N.; Møhl, B.; DePanfilis, D.; Vammen, K.S. Non-suicidal self-injury—does social support make a difference? An epidemiological investigation of a Danish national sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2015, 44, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, S.; Wang, L.; Sun, J.; Xu, M.; Zhang, L.; Yi, Z.; Ji, J.; Zhang, X. Risk factors and protective factors for nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescents: A hospital- and school-based case-control study. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 1321–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.Y.; Luo, Y.H.; Shi, L.J.; Gong, J. Exploring psychological and psychosocial correlates of non-suicidal self-injury and suicide in college students using network analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 336, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renna, M.E.; Fresco, D.M.; Mennin, D.S. (2020). Emotion Regulation Therapy and its potential role in the treatment of chronic stress-related pathology across disorders. Chronic Stress 2020, 4, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Calvo, N.; García-González, S.; Perez-Galbarro, C.; Regales-Peco, C.; Lugo-Marin, J.; Ramos-Quiroga, J-A.; Ferrer, M. Psychotherapeutic interventions specifically developed for NSSI in adolescence: A systematic review. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022, 58, 86-98. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).