1. Introduction

Beliefs that maintain patriarchal principles are fundamental in shaping the lives of men and women on all levels of social interaction [

1]. Such beliefs may differentially affect the behaviors of men and women in their intimate relationships. First, they may affect their willingness to trigger conflict or reluctance to oppose their partner’s position or behavior. Second, such beliefs, coupled with conflict avoidance, may promote or prevent economic violence. This study examined sex differences in beliefs supporting patriarchal principles, conflict avoidance, and economic violence and the associations among these factors. To enable greater understanding of the contribution of support for patriarchal beliefs and issues related to intimate partner relationships, this study focused on the ultra-Orthodox Jewish population in Israel. The ultra-Orthodox Jewish group is a collectivist, traditional, patriarchal, and insular culture that tends to take a conservative and traditional view of gender roles and intimate partner relations [

2].

1.1. Patriarchal Beliefs

Patriarchy characterizes all human societies to some degree and can be defined as a gendered sexual system in which men control women and what is considered masculine is valued more than what is considered feminine [

3]. Research based on feminist approaches has indicated that violence against women is rooted deeply in patriarchal structures of society [

4]. Patriarchy is a multidimensional concept (for further discussion, see Benstead [

5]). Yoon and colleagues [

4] identified three factors representing patriarchal beliefs rooted in micro, meso, and macro levels of social systems and integrated them in their Patriarchal Beliefs Scale (PBS). This approach was adopted in the current research.

The first factor identified by Yoon et al. [

4] is the institutional power of men, referring to beliefs in general male authority and leadership. The underlying assumption of these beliefs is male domination and female subordination, especially at meso and macro levels of social systems and in matters of greater importance and social impact. The second factor is the inherent inferiority of women, referring to beliefs in women’s inferiority, subordinate status, and restriction or exclusion from diverse social roles, mostly at meso and macro levels, like the workplace, education, community involvement, and so on. The underlying assumption of these beliefs is male superiority and female inferiority, which should be reflected in their social status and roles. Last, the third factor is gendered domestic roles, referring to beliefs in gendered roles in the family (micro level), where men are destined to be providers and decision makers and women are destined to be caretakers for children and the household. The underlying assumption of these beliefs is a natural order, an indisputable precondition of women and men for specific familial functions.

1.2. Cultural Context of the Study

Although legally and formally an egalitarian, liberal democracy, Israeli society is also characterized by a great variety of ethnicities, religions, and cultures, some of which have more pronounced patriarchal structures and hold more conservative patriarchal beliefs than others [

6]. Israeli society features Palestinian Israelis (25.7%) and Jewish Israelis (74.3%). The Jewish Israeli group further divides according to religiosity levels, including religious (15.5%), traditional (25%), secular (45.4%), and ultra-Orthodox (14.1%). This study was conducted with the ultra-Orthodox population in Israel—a culturally isolated group that has been described in the literature as a collectivist, patriarchal system created and run by men that is insular and has the tendency to take a conservative and traditional view of gender roles and intimate partner relations [

7]. Ultra-Orthodox women play a significant role as wives and mothers, whereas men are in charge of the public domain and religious practice [

8,

9]. When focusing on the lived reality of this population, the ultra-Orthodox group factually fosters patriarchal beliefs and structures, which are most pronounced on the micro level of family relations [

7]. Because of these unique characteristics, a focus on the ultra-Orthodox group allows a better understanding of the contribution of support for patriarchal beliefs to intimate partner relationships, including conflict avoidance and economic violence.

1.3. Partner Conflict Avoidance

Willingness to engage in or avoidance of conflict in intimate relationships has been studied in recent decades [

10]. A distinction is often made between demand (willingness to engage in conflict through criticism and complaint) and withdrawal (avoidance of conflict through defensiveness and passivity). Such research generated three distinct dyadic patterns [

11]. Two are symmetrical, with both partners displaying the same pattern (i.e., demand–demand or withdrawal–withdrawal) and another is asymmetrical (i.e., demand–withdrawal). The asymmetrical pattern, more than the symmetrical ones, was identified as bearing destructive potential [

12] and hence, has received the most attention. Research has indicated that in this pattern, women tend to demand and men tend to withdraw [

13].

Various perspectives have been proposed to explain sex differences in this context: the individual differences perspective [

14], gender role and socialization differences perspective [

15], power discrepancies perspective [

16], and issues and goals perspective [

17]. The last perspective suggests that it is primarily a partner’s position and goals regarding a specific conflict issue that determine whether they demand or withdraw from the conflict. Put simply, when spouses desire changes in their relationship or partner, they are more likely to criticize and demand. When spouses are satisfied with the status quo, however, they are more likely to avoid the discussion and withdraw [

11]. Accordingly, due to the sex power balance and men’s tendency toward preserving rather than changing this balance, men are stipulated to display a weaker inclination than women to initiate intimate conflicts, whereas women’s tendency to initiate such conflicts is stronger. Moreover, men’s tendency to evade partner conflicts could be rewarding by generating a false belief that the man is not the dominant party in the relationship [

10]. Additionally, subject to the issues and goals perspective [

17] and sex power balance, in the existing social constructs, men arguably have a clear advantage over women outside the family home. This advantage makes the home the women’s last stronghold; hence, they will strive more than men to protect their rights there, even via conflicts if required.

1.4. Economic Violence

Economic violence was added in May 2011 as a fourth form of violence against women—after physical, sexual, and psychological violence—in Article 3 of the Council of Europe’s [

18] Istanbul Convention. Nevertheless, the concept of economic violence is yet developing. A recent meta-analysis [

19] has shown that economic abuse was not always clearly defined and its measurement varied substantially across 46 studies. However, some characteristics of economic violence have been rather consistently represented in many studies.

One guiding theoretical framework is the Scale of Economic Abuse [

20]. According to this framework, economic abuse features two distinct dimensions: economic control and economic exploitation. Economic control occurs when the husband achieves control over the family’s finances—for example, by taking over his wife’s bank account, limiting her access to money or other means of payment, or demanding a full report of her spending. It also includes tactics that interfere with the wife’s ability to acquire resources or use her existing resources. Economic exploitation occurs when the husband coerces his wife into financial obligations, such as by acquiring debt or spending money her name or leaving her responsible for bills vital to run the household or take care of the children. It also includes tactics of monitoring the wife’s usage of resources, dictating how she uses them, or depleting her of resources altogether.

Another conceptual framework [

21], based on the experiences of victims of economic abuse, suggests three distinct abusive tactics often utilized by men against their wives, adding employment sabotage as the third tactic of economic violence. Employment sabotage occurs when the perpetrator inhibits his wife from acquiring training or education, seeking employment, or succeeding in her job. This enhanced conceptual framework was empirically tested and led to the development of the shortened, three-factor version of the Scale of Economic Abuse utilized in the current study [

21].

Economic partner violence harms women financially and disrupts their efforts to be economically independent [

22]. Various aggressive behaviors are intended to “control a woman’s ability to acquire, use and maintain economic resources, thus threatening her economic security and potential for self-sufficiency” [

20] (p. 564). Economic exploitation, economic control, and employment sabotage have been identified as the most noticeable tactics of economic violence [

19,

21]. This research assessed economic violence according to these tactics.

1.5. Summary and Research Hypotheses

The study tested the following hypotheses: (1) Beliefs supporting patriarchal principles will be upheld by men more than by women. The smallest differences between men and women will be found on the micro level of the practiced role division at home, because major perceived differences between partners in the domestic context may interfere with the functioning of the couple and family. (2) Based on findings of previous studies on partner conflict avoidance [

10], conflict avoidance will be higher among men than among women. (3) Stronger beliefs supporting patriarchal principles will be associated with increased economic violence against women. Further, conflict avoidance by one partner may be considered by the other partner as permission to use power and establish control. Hence, conflict avoidance by one partner will predict the other partner’s use of violence, including economic violence.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Procedure and Research Ethics

The data were collected by ultra-Orthodox undergraduate students who were trained for this purpose by the study’s principal investigators. The students sampled adult acquaintances and invited them to participate in the study. They explained the study’s aim and emphasized its purpose and importance. Individuals who expressed their willingness to participate in the study were asked to complete questionnaires (either printed or electronic, based on the participant’s preference) privately and anonymously, such that no one would know that they had participated in the study or how they responded. Participants were also informed of their right to decline to participate in the study, their option to not answer all the questions, and their ability to stop at any stage. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the authors’ affiliated institution.

2.2. Measurements

Questionnaires included items measuring beliefs in patriarchal ideologies, conflict avoidance, economic violence victimization, and sociodemographics.

2.2.1. Beliefs in Patriarchal Ideologies

Measurement of beliefs in patriarchal ideologies was based on a shortened version of the PBS [

4]. The original instrument includes 35 items that measure the respondent’s degree of agreement with patriarchal ideologies situated at three levels of social systems: micro level (family, domestic roles; e.g., “Cleaning is mostly a woman’s job”); meso level (school, local community; e.g., “Women should be paid less than a man for doing the same job”); and macro level (state politics, major companies; e.g., “I am more comfortable with men running big corporations than women”). Responses were given on a 5-point Likert scale: 1 =

strongly disagree, 2 =

slightly disagree, 3 =

agree to some extent, 4 =

agree, and 5 =

strongly agree. Because the current study focused on additional topics, a shortened version of the PBS was used that included 22 items to increase participants’ likeliness to respond. Reliabilities of the shortened PBS instrument, as indicated by internal consistency, were high for patriarchal ideologies situated at the micro (α = .90), meso (α = .71), and macro (α = .93) levels.

Three summary measures of chronicity were computed, indicating the average of the items measuring patriarchal ideologies situated at the micro, meso, and macro levels.

2.2.2. Partner Micro-Level Beliefs Supporting Patriarchal Ideologies

The questionnaire also included items referring to the participants’ partner’s micro-level beliefs in patriarchal ideologies. The 10 items that measured participants’ micro-level self-evaluation of patriarchal ideologies were used for this measure, modified such that they referred to the respondents’ partner. The chronicity of the partner beliefs summary measure was computed, indicating the average of the 10 items measuring partners’ patriarchal ideologies at the micro level.

2.2.3. Couple Micro-Level Climate

Based on the two micro-level beliefs in patriarchal ideologies (based on self-evaluation and partner evaluation), a couple climate variable was computed, indicating the average of respondents’ self- and partner evaluations of micro-level beliefs in patriarchal ideologies (α = .94).

2.2.4. Conflict Avoidance

A short conflict avoidance measure consisted of four items. Participants were asked to report the frequency with which they took the following actions when they disagreed with their partner: (a) “You refrained from expressing your opinion so as not to start a fight with your partner”; (b) “You agreed with your partner’s position, even if you thought it was wrong to please him/her”; (c) “You accommodated your partner’s demands so as to not make him/her angry”; and (d) “You did what your partner wanted although it was against your best judgement.” Response options were on a 5-point Likert scale: 1 = never happens, 2 = rarely happens, 3 = does not happen a lot but also not too rarely, 4 = often happens, and 5 = happens all the time. Following the collection of data, reliability (internal consistency) was tested for the four items together and found to be high (α = .92). A summary measure was computed, indicating the average of the four items measuring conflict avoidance.

2.2.5. Economic Violence Victimization

Economic violence was measured utilizing the 12 items of the Revised Economic Violence Scale [

21]. The instrument was adjusted for the Hebrew-speaking population, rephrased to accommodate both men and women. Two items were added to the original instrument, with the aim of including essential issues excluded from the original scale (“Your partner made you go to work” and “Your partner neglects household economic obligations”). Hence, the instrument used in this study consisted of 14 items representing various types of economic violence partner victimization. Each item inquired about the frequency of a specified matter that happened in the past year (e.g., “Your partner demanded to see what you spent money on” or “Your partner withheld information concerning your funds”). Responses were on 5-point Likert scale: 1 =

never happened, 2 =

rarely happens, 3 =

does not happen a lot but also not too little, 4 =

often happens, and 5 =

happens all the time. Reliability for the 14 items was high (α = .82).

The second stem tested the factorial construct of the measurement (principal component analysis for extraction and varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization; eigenvalues greater than 1 were deemed significant). First, the analysis was performed separately for men and women, then for both sexes together. The analyses were consistent, yielding four factors: (a) monitoring and control (e.g., “Your partner demanded to know on what you spent money”), (b) nondisclosure (e.g., “Your partner made financial decisions without consulting you first”), (c) work-related interference and abuse (e.g., “Your partner withheld you from going to work”), and (d) exploitation and humiliation (e.g., “Your partner wasted the money you needed for paying the household bills”). Reliabilities were high for monitoring and control (α = .80); nondisclosure (α = .78), and work-related interference and abuse (α = .79) and fair for exploitation and humiliation (α = .65). Based on the measurement analyses, five summary measures were computed, indicating the average of the items that loaded on each factor. The fifth variable was based on the average value of all 14 items (α = .82).

2.2.6. Demographics

Participants were asked to identify their sex (male or female), age in years, family status (bachelor, married or living with a partner, divorced, or widowed), number of children, education level (master’s degree or higher, bachelor’s degree, 14 years of schooling, high school, or elementary school), economic status (higher than average, average, or lower than average), the extent to which their household income is sufficient for current expenses (insufficient, partly sufficient, sufficient, and very sufficient), and degree of household economic stress (high, medium, or low). Because data were collected from the ultra-Orthodox Jewish population in Israel (by students who are members of this group), there was no need to collect data on participants’ nationality or religiosity.

2.3. Analytic Procedure

The first step of the analysis examined the inference and descriptive statistics to identify gender differences in research variables. The second step examined the research model, using path analysis to assess correlations between research variables for men and for women. Analyses was conducted using SPSS and AMOS (version 27) statistical software.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

This sample included 321 participants, 60.0% of whom identified as female, with an average age of 34.36 years (SD = 10.15). Participants reported that they were married for 11.87 years on average (SD = 10.32) and had about three kids on average (SD = 2.8). Most women (88.3%) and men (91.7%) had higher education degrees. More than half of the women and men reported that they worked full time (57.8% and 58.4%, respectively) or part time (26.7% and 12.3%, respectively). About half of the participants reported an average economic status (57.4%), that their household income was sufficient for current expenses (49.5%), and that they experienced medium (43.0%) or high (49.4%) economic stress.

3.2. Sex Differences in Beliefs in Patriarchal Ideologies

Sex differences in beliefs in patriarchal ideologies were tested using a repeated-measures procedure. The mean of beliefs in patriarchal ideologies served as the dependent variable. The ecological level at which beliefs were situated (micro, meso, or macro) served as a within-subject variable, and respondents’ sex (male or female) served as a between-subject variable. The main effect of the ecological level of beliefs in patriarchal ideologies, F(2, 316) = 330.02, p < .001, η2 = .68, and the respondents’ sex, F(1, 317) = 12.21, p < .001, η2 = .04, were significant. The interaction between the ecological level and respondents’ sex was also significant, F(2, 316) = 3.78, p < .024, η2 = .02. These findings demonstrate a significant difference between men and women in beliefs in patriarchal ideologies.

To further examine sex differences in beliefs in patriarchal ideologies at each ecological level,

t-tests were employed. The results are presented in

Table 1. Overall, beliefs in patriarchal ideologies were low. The lowest level of beliefs in patriarchal ideologies were obtained with respect to the meso level. On the macro and meso levels, men had significantly stronger beliefs in patriarchal ideologies than women. No significant sex differences occurred on the micro level.

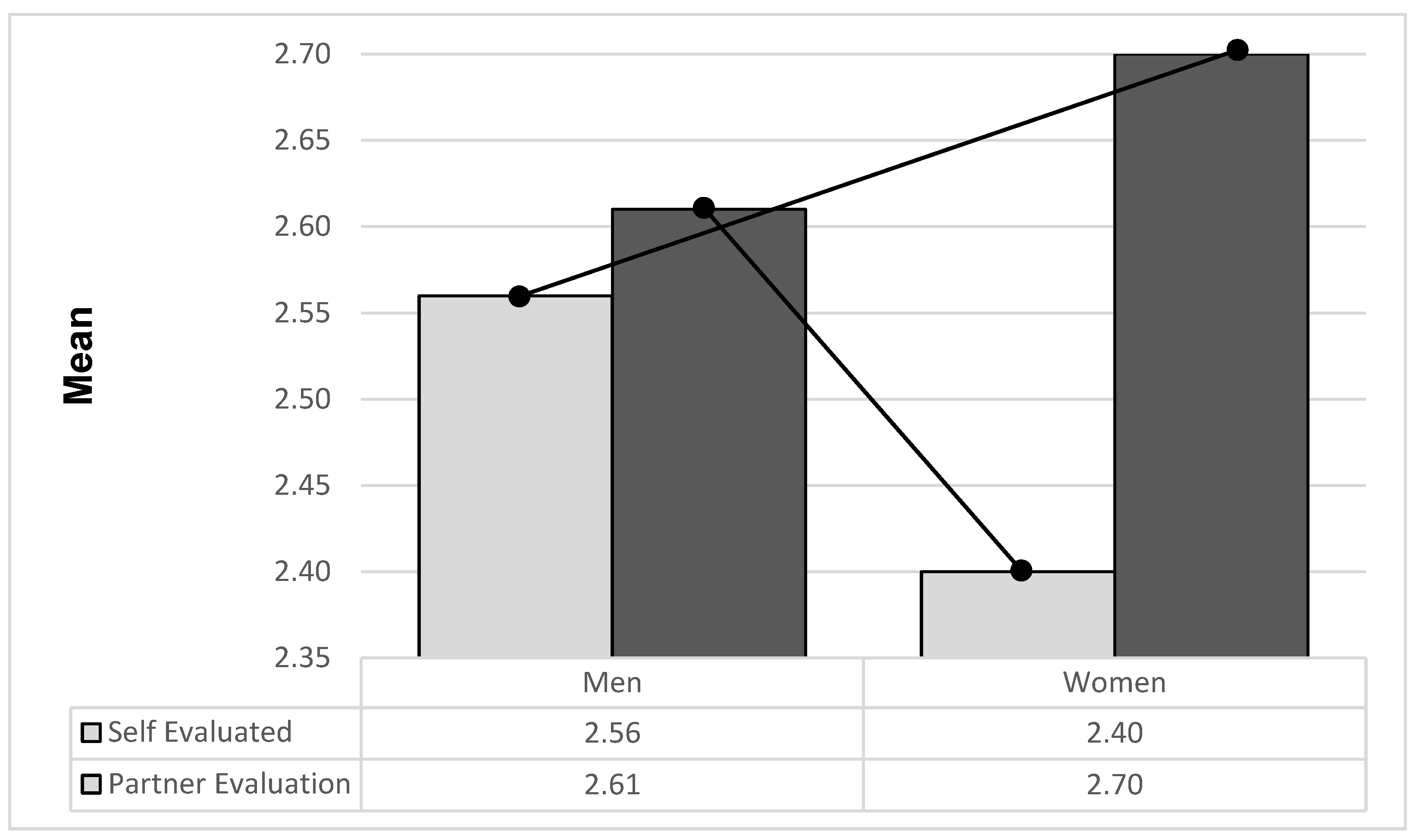

3.2.1. Sex Differences in Micro-Level Patriarchal Ideologies and Couple Climate in Support of Patriarchal Ideologies

The respondents also provided their estimation of their partner’s support of patriarchal ideologies at the micro level (sex roles). A repeated-measures procedure was used to compare men’s and women’s self-evaluation and partner evaluation of beliefs in patriarchal ideologies. The findings indicate a significant interaction effect between the respondent’s sex (between-subject variable: male or female) and the object of evaluation (within-subject variable: self or partner) on the micro-level beliefs supporting patriarchal ideologies,

F(1, 313) = 9.69,

p < .002, η

2 = .03. These results are presented in

Figure 1. All participants, but particularly women, estimated their partner’s micro-level beliefs supporting patriarchal ideologies as higher than their own. Mean comparisons among men’s self-reports of beliefs in patriarchal ideologies and women’ estimation regarding their male partners, and vice versa, revealed similar disparities. Paired sample

t-tests showed that the mean difference between self-evaluation and partner evaluation was significant only for women,

t(190) = 5.77,

p < .001.

Next, sex differences in reports of couple climate were examined. The

t-test results are presented at the bottom of

Table 1. The analysis revealed sex differences were not significant.

3.2.2. Correlations between Couple Climate and Beliefs in Support of Patriarchal Ideologies

Table 2 summarizes the correlations between couple climate and subscales of beliefs in support of patriarchal ideologies. Correlations were strong and significant. The couple climate variable was used in further analysis.

3.3. Conflict Avoidance

Sex differences were tested at the average level based on conflict avoidance. Paired-sample t-tests showed significant sex differences in the average level of conflict avoidance, t(216.17) = 5.8, p < .001, demonstrating significantly higher conflict avoidance among men (M = 2.42, SD = 0.96) than among women (M = 1.82, SD = 0.78).

3.4. Economic Violence Victimization

Sex differences in economic violence victimization were tested based on the four victimization variables (monitoring and control, nondisclosure, work-related interference and abuse, and exploitation and humiliation) using independent-sample

t-tests (

Table 3). The findings reveal nonsignificant sex differences in economic violence victimization.

3.5. Correlations between Subscales of Economic Violence Victimization

The correlations between subscales of economic violence victimization and economic violence were tested further. The analyses yielded positive and significant correlations (see

Table 4).

3.6. Associations between Study Variables

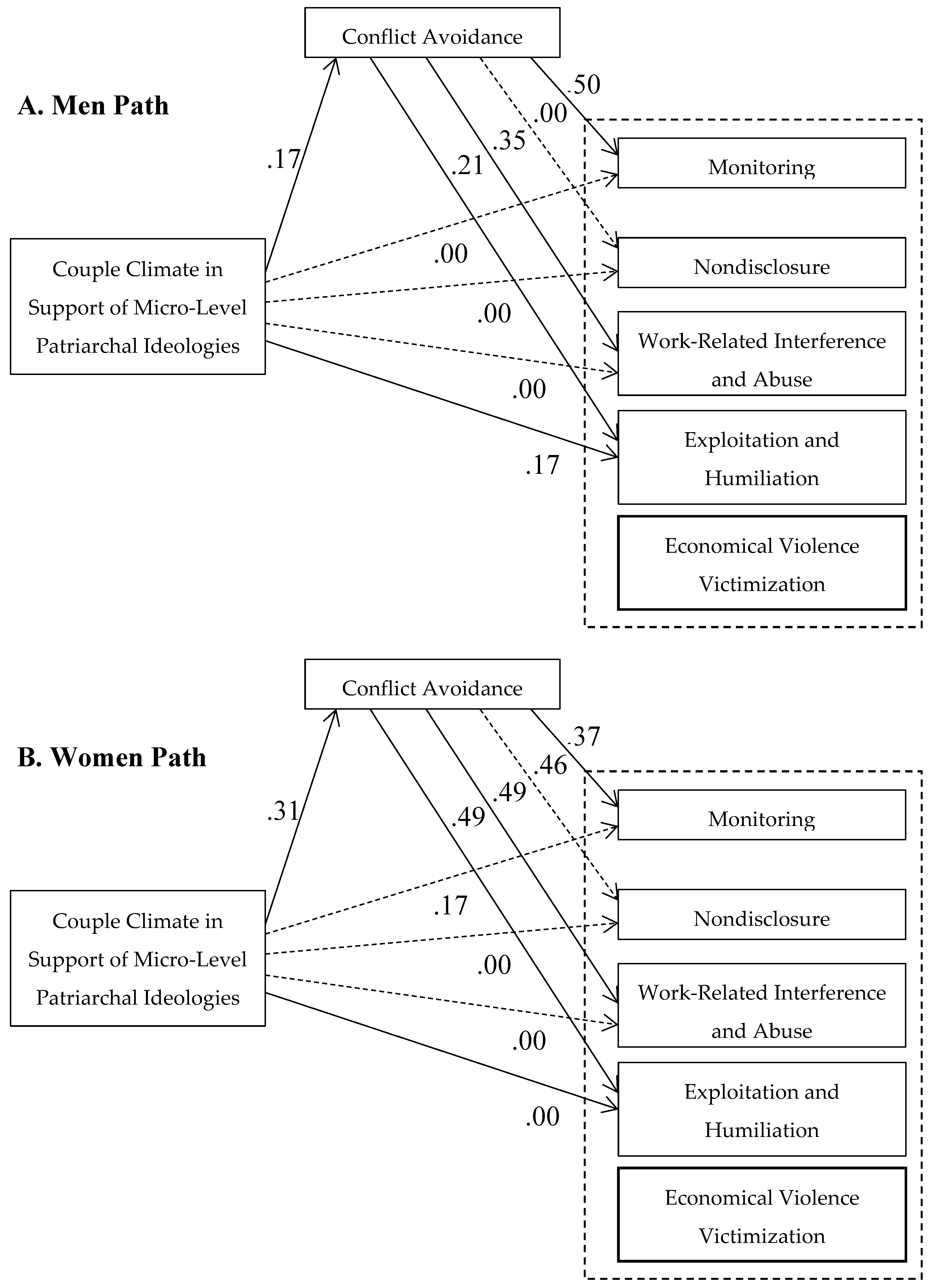

The final study model tested the associations between the study variables using path analysis. The model included three factors: (a) the microlevel couple climate in support of patriarchal ideologies, (b) conflict avoidance, and (c) the four economic violence victimization subscales. To further explicate the study model, multigroup analysis was employed to test whether the hypothesized patterns of interrelationships remained consistent or differed across subsamples by sex.

Figure 2 presents the study model and results. The model’s fit indexes were good, χ

2(7) = 10.75,

p = .15, NFI = .97, IFI = .99, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .04.

The path between couple climate in support of micro-level patriarchal ideologies and conflict avoidance was positive and significant for both men and women, although stronger for women. The higher the couple’s beliefs in support in patriarchal ideologies, the stronger the tendency to avoid conflict. Almost all paths between conflict avoidance and the different subscales of economic violence victimization were significant and positive for both men and women, except for the path between avoidance and nondisclosure for men.

The model findings further indicate sex differences in the paths between couple climate in support of micro-level patriarchal ideologies and the types of economic violence victimization. For women, couple climate had a significant positive effect on monitoring: The higher the couple’s beliefs in support in patriarchal ideologies, the higher the monitoring victimization. For men, couple climate had significant positive effect on exploitation and humiliation. The higher the couple’s beliefs in support of patriarchal ideologies, the higher the exploitation and humiliation victimization.

4. Discussion

Beliefs that maintain patriarchal principles may affect the behaviors of individuals in their intimate relationships in terms of willingness to avoid conflict that eventually likely affects the chances of intimate partner economic violence. Nonetheless, research has yet to fully explore these associations. To fill in this gap, this study examined sex differences in beliefs supporting patriarchal principles, conflict avoidance, and economic violence and the associations among these factors in a sample of ultra-Orthodox Jewish adults. The ultra-Orthodox culture has been portrayed in the literature as a patriarchal system in which women play traditional female roles and men are in charge of the public domain and religious practice [

23]. Results based on scientific exploration of this patriarchal culture can further our understanding of the contribution of beliefs that support patriarchal ideologies to partner conflict avoidance and economic violence, a relatively new phenomenon in research, and guide interventions to address this worrisome social problem.

4.1. Beliefs in Support of Patriarchal Ideologies

Overall, participants reported modest levels of beliefs in patriarchal ideologies at the micro, meso, and macro levels, demonstrating that individuals in the current sample tended to reject and renounce patriarchal ideologies. The findings further suggest that the extent to which individuals renounce patriarchal ideologies is related to sex: Comparison of beliefs in patriarchal ideologies by sex demonstrated that men, significantly more than women, expressed greater tolerance and support of patriarchal principles. It is likely that men expressed greater endorsement of patriarchal ideologies because they offer men more power and privilege in our society than women [

24]. Renouncing patriarchal ideologies may be interpreted by men as a threat to their privilege and dominance.

The findings further suggest that for both men and women, beliefs in patriarchal ideologies were highest at the macro and micro levels and lowest at the meso level. Macro-level patriarchal beliefs reflect societal attitudes regarding the institutional power of men and beliefs in male authority and leadership that go beyond domestic, interpersonal, or work situations [

25]. Meso-level patriarchal beliefs regard how such beliefs in male authority and leadership should be applied at the social level (e.g., workplace). The participants in the current study tended to agree with sex differences in authority and power, but at the same time, they were reluctant to apply these differences. In the domestic arena, sex differences were supported through a more traditional division of labor. It seems that division of traditional domestic roles are perceived as a contract or understanding between spouses that is unrelated to sex differences in authority or power. The findings may also suggest a significant gap between the participants’ rhetoric and practice: Although participants tended to spurn patriarchal ideologies at the meso level, they also tended to support and perhaps implement these patriarchal practices at the micro level in their domestic and interpersonal relationships.

4.2. Conflict Avoidance

Advocates of male control theory [

26] have argued that in patriarchal social structures, men tend to use aggression and control in intimate relationships to a much greater extent than women. Yet the current findings suggest a different pattern: Men, significantly more than women, tended to avoid conflict with their female intimate partner. These findings echo prior research indicating a stronger escalatory tendency in intimate partner conflicts among women than among men [

10]. A possible explanation for the current finding is that there are sex differences in conflict avoidance. In adherence with the authority and power imbalance by which men enjoy greater control and influence women [

27], it can be assumed that men perceive conflict avoidance as fortitude and strength whereas women perceive it as a weakness. It may be that the privilege of power and authority experienced by men in their intimate partner relationships encourages their responsibility to maintain their relationships and avoid conflict, if needed. Put differently, when men avoid conflict with their intimate female partner, they display themselves as sensitive to their partner’s needs and desires. It is important to mention that although home and intimate partner relationships are important for men and women alike, men have more opportunities to fully implement their power in the workplace and public sphere and are less restricted to the domestic arena. As opposed to men, conflict avoidance for women may be perceived as a concession that likely predicts further concessions and undermines their status in their major stronghold—their home. Thus, women invest much of their efforts to safeguard their domestic status and power in their intimate relationships and accordingly, they do not tend to concede or compromise regarding conflict with their intimate male partner. As a result, sex differences in conflict avoidance create and preserve a false consciousness of sex equity: Men feel very egalitarian for avoiding conflict with their female intimate partner, and women feel very egalitarian for subordinating or forcing their desires on their male intimate partner.

In adherence with these results, the current findings further indicate that beliefs that maintain patriarchal principles sustain conflict avoidance for both sexes, although to a greater extent among women. Stronger beliefs in patriarchal principles predicted greater conflict avoidance among both men and women—although again, support of patriarchal ideologies empower men and inhibit women [

28]. Thus, empowered men (who support patriarchal ideologies) do not need exert strength and demonstrate their dominance in their intimate relationships to establish their status and therefore, they likely avoid conflict. On the other hand, men who feel weakened (who do not support patriarchal ideologies) need to enhance their domestic status through strength exertion. Weakened women (who also support patriarchal ideologies) do not recognize their right to exert their strength and thus, avoid conflict. On the other hand, empowered women (who do not support patriarchal ideologies), like empowered men (who support patriarchal ideologies), do not need to exert strength. Therefore, sex empowerment through men’s support or women’s rejection of patriarchal ideologies reinforces intimate partner conflict avoidance.

4.3. Economic Violence Victimization

As opposed to prior research [

29], the current findings did not indicate significant sex differences in economic violence victimization. These findings, however, do not suggest that economic violence victimization is not rooted in sex issues. There may be different explanations for the nonsignificant sex differences in economic violence victimization obtained in the current research. First, economic violence likely disrupts the everyday life of both the perpetrator and victim, causing economic damage. Second, in egalitarian and Western societies, intimate partner violence, including economic violence, is viewed with contempt and may result in legal restrictions that reduce the perpetrators’ freedom and social status. Third and perhaps the strongest factor that moderates men’s and women’s likelihood of perpetrating economic violence against their intimate partner is the positive association between willingness to escalate conflict and perpetration of economic violence. As mentioned, men tend to avoid conflict significantly more than women. Conflict avoidance moderate men’s tendency to perpetrate violence of any kind, including economic violence. Women tend not to avoid conflict and as a result, become more vulnerable to their intimate partner’s economic violence.

4.4. Study Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Although informative, the current results should be considered with some limitations in mind. First, the study was based on a nonrepresentative sample of ultra-Orthodox Jewish adults; thus, the study sample does not represent the entire adult population. While focusing on the ultra-Orthodox conservative and traditional culture provided a unique opportunity to understand the contribution of patriarchal ideologies to intimate partner relationships, the findings do not provide evidence regarding these associations among more egalitarian and liberal cultures. Additional research is encouraged to further explore the associations among beliefs that support patriarchal principles, intimate partner conflict, and economic violence using representative samples to generalize findings to the entire population of adults and design effective prevention and intervention strategies to address intimate partner violence. Exploring these associations among diverse cultures could uncover ethnocultural disparities in the association among the study variables and determine whether they manifest differently in more egalitarian and liberal cultures as opposed to more traditional and patriarchal cultures. This kind of knowledge is sorely needed to adapt existing interventions to specific cultures to increase their effectiveness.

Second, the data for the study were collected at one point. These data demonstrate associations between variables, rather than their causal relationships. To establish causal arguments based on large population-based samples, longitudinal data are required. Future studies could employ longitudinal research arrays to explore causal arguments stemming from the relevant models and theories.

4.5. Clinical Implications

The findings have important implications for practice. Social workers, therapists and other professionals working with couples surrounding intimate relationships violence should consider that both men and women may exhibit violence in their intimate relationships, not only women. In contrary to the common stereotype that women are more prone than men to exhibit intimate partner violence, the findings suggest that both partners are vulnerable to economic violence [

10]. Thus, interventions should target economic violence regardless of the victims’ gender. Further, to increase the effectiveness of interventions, professionals are encouraged to consider conflict avoidance in intimate relationship as an important predictor of violence victimization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ruth Berkowitz, David Mehlhausen-Hassoen and Zeev Winstok.; methodology Zeev Winstok.; software, Ruth Berkowitz.; validation, Ruth Berkowitz, David Mehlhausen-Hassoen and Zeev Winstok.; formal analysis, Zeev Winstok.; investigation, Ruth Berkowitz.; resources, Ruth Berkowitz.; data curation Ruth Berkowitz.; writing—original draft preparation, Ruth Berkowitz.; writing—review and editing, Ruth Berkowitz, David Mehlhausen-Hassoen and Zeev Winstok.; visualization, Ruth Berkowitz, Zeev Winstok.; supervision, Zeev Winstok.; project administration, Ruth Berkowitz.; funding acquisition, None. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Social Welfare and Health Sciences at the University of Haifa, Israel (protocol code 2605; 31 December 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data is available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sugarman, D.B.; Frankel, S.L. Patriarchal ideology and wife-assault: A meta-analytic review. J. Fam. Viol. 1996, 11, 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itzhaky, H.; Kissil, K. “It’s a horrible sin. If they find out, I will not be able to stay”: Orthodox Jewish gay men’s experiences living in secrecy. J. Homosex. 2015, 62, 621–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosselin, D.K. Heavy Hands: An Introduction to the Crimes of Intimate and Family Violence, 5th ed. Pearson Education, Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2014.

- Yoon, E.; Adams, K.; Hogge, I.; Bruner, J.P.; Surya, S.; Bryant, F.B. Development and validation of the Patriarchal Beliefs Scale. J. Couns. Psychol. 2015, 62, 264–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benstead, L.J. Conceptualizing and measuring patriarchy: The importance of feminist theory. Mediterr. Polit. 2021, 26, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogiel-Bijaoui, S. Navigating gender inequality in Israel: The challenges of feminism. In Handbook of Israel: Major Debates; Ben-Rafael, E., Schoeps, J.H., Sternberg, Y., Glöckner, O., Eds.; De Gruyter, Berlin, Germany, 2016, pp. 423–436.

- Lavie, N.; Kaplan, A.; Tal, N. The Y Generation myth: Young Israelis’ perceptions of gender and family life. J. Youth Stud. 2022, 25, 380–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boteach, S. Judaism for Everyone. Basic Books, New York, NY, USA, 2002.

- Hess, E. The centrality of guilt: Working with ultra-Orthodox Jewish patients in Israel. Am. J. Psychoanal. 2014, 74, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winstok, Z.; Smadar-Dror, R.; Weinberg, M. Gender differences in intimate-conflict initiation and escalation tendencies. Aggress. Behav. 2018, 44, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrodt, P.; Witt, P.L.; Shimkowski, J.R. A meta-analytical review of the demand/withdraw pattern of interaction and its associations with individual, relational, and communicative outcomes. Commun. Monogr. 2014, 81, 28–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heavey, C.L.; Layne, C.; Christensen, A. Gender and conflict structure in marital interaction: A replication and extension. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1993, 61, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A.; Shenk, J.L. Communication, conflict, and psychological distance in nondistressed, clinic, and divorcing couples. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1991, 59, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caughlin, J.P.; Huston, T.L. Demand/withdraw patterns in marital relationships: An individual differences perspective. In Applied Interpersonal Communication Matters: Family, Health, and Community Relations; Dailey, R.M., Le Poire, B.A., Eds.; Peter Lang, Lausanne, Switzerland, 2006, pp. 11–38.

- Napier, A.Y. The rejection-intrusion pattern: A central family dynamic. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 1978, 4, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A.; Heavey, C.L. Gender and social structure in the demand/withdraw pattern of marital conflict. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caughlin, J.P.; Scott, A.M. Toward a communication theory of the demand/withdraw pattern of interaction in interpersonal relationships. In New Directions in Interpersonal Communication Research; Smith, S.W., Wilson, S.R., Eds.; Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010, pp. 180–200.

- Council of Europe. Council of Europe convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/4ddb74f72.html (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Postmus, J.L.; Hoge, G.L.; Breckenridge, J.; Sharp-Jeffs, N.; Chung, D. Economic abuse as an invisible form of domestic violence: A multicountry review. Trauma Viol. Abuse 2020, 21, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, A.E.; Sullivan, C.M.; Bybee, D.; Greeson, M.R. Development of the Scale of Economic Abuse. Viol. Against Women 2008, 14, 563–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postmus, J.L.; Plummer, S.B.; Stylianou, A.M. Measuring economic abuse in the lives of survivors: Revising the Scale of Economic Abuse. Viol. Against Women 2016, 22, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, T.L.; Sanders, C.K.; Campbell, C.L.; Schnabel, M. Development and preliminary psychometric evaluation of the Domestic Violence-Related Financial Issues Scale (DV-FI). J. Interpers. Viol. 2009, 24, 569–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringel, S. Identity and gender roles of Orthodox Jewish women: Implications for social work practice. Smith Coll. Stud. Social Work 2007, 77, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelaurain, S.; Fonte, D.; Giger, J.C.; Guignard, S.; Lo Monaco, G. Legitimizing intimate partner violence: The role of romantic love and the mediating effect of patriarchal ideologies. J. Interpers. Viol. 2021, 36, 6351–6368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, E.; Cabirou, L.; Bhang, C.; Galvin, S. Acculturation and patriarchal beliefs among Asian American young adults: A preliminary investigation. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 2019, 10, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobash, R.E.; Dobash, R. Violence Against Wives: A Case Against the Patriarchy. Free Press, New York, NY, USA, 1979.

- Sagrestano, L.M.; Heavey, C.L.; Christensen, A. Perceived power and physical violence in marital conflict. J. Soc. Issues 1999, 55, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.E.A. Walker, L.E.A. The Battered Woman Syndrome, 4th ed. Springer, New York, NY, USA, 2017.

- Outlaw, M. No one type of intimate partner abuse: Exploring physical and non-physical abuse among intimate partners. J. Fam. Viol. 2009, 24, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).