Introduction

The interconnection between Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs) and wage dynamics constitutes a critical area of inquiry within the realm of economic studies (Yasin et al, 2022; Hou et al, 2021; Nguyen, 2019; Bacovic, 2021). This research embarks on a diachronic exploration, delving into the evolving relationship between FDIs and the wages of salaried employees in the Netherlands. As a nation renowned for its open and dynamic economy (Zhihai, 2010; Doelman et al, 2012; Walker et al, 2021), the Netherlands offers a compelling context for investigating the impact of international capital flows on labor market outcomes.

Over the years, the Dutch economy has thrived on its proclivity towards international trade and investment (McNeely, 2021; de Jong & Vijge, 2021). The influx of FDIs, driven by globalization and economic integration, has been a defining feature of the economic landscape (Zhuo & Qamruzzaman, 2022; Daytich & Uchtum, 2016; Bojnec & Fertő, 2018; Muhammad & Khan, 2021). Understanding how these investments influence wage trends holds significant implications for policymakers, economists, and practitioners alike. Moreover, within the crucible of globalization, comprehending the gender-specific dimensions of this impact is imperative, as it relates to broader discussions on income equality and economic inclusivity.

The Netherlands, renowned for its advocacy towards economic openness and resilience, perennially holds a preeminent standing as a magnet for FDIs inflows in the European context (Pegkas, 2015; Rodriguez-Pose & Garcilazo, 2015; Long et al, 2016). The complex interactions between these investments and how salaried workers are paid create a practical environment full of details and nuances. A diachronic modus operandi engenders a holistic evaluation of how, policy vicissitudes, and economic oscillations have collectively conduced to modify the FDIs-wage interconnection in the Dutch domain.

This research is based on the idea that a clear understanding of how FDIs affects wages over time is essential for making wise policies and effective economic plans. Additionally, recognizing these dynamics provides a basis for evaluating the broader impact on how income is distributed, the stability of the job market, and the overall economic well-being in our globalized world.

This analysis aims also to delve into the intricate relationship between FDIs and wage dynamics among salaried workers in the Netherlands. Through a rigorous examination of statistical indicators, this study endeavors to unravel the nuanced patterns and causal propensities governing the impact of FDI on wage trends. The empirical model, meticulously constructed, demonstrates a substantial explanatory power, shedding light on the extent to which FDIs influences wages within the Dutch labor market.

By adopting a diachronic perspective, we aim to provide a nuanced perspective on how FDIs have shaped the compensation structures of the salaried labor force over time. The analytical framework, rooted in data sourced from authoritative institutions such as the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and the World Bank, is supporting the robustness of our findings.

The symbiotic dynamics between FDIs and labor market phenomena have engendered sustained academic and policy deliberation. Of particular interest is the discernment of FDI's influence on the remuneration trajectories of salaried personnel, being a cornerstone in comprehending the broader ramifications of international capital infusion.

In the next sections, we explain the theories that support this research, review important academic works, describe the methods we use to analyze our data, and outline the structure of the rest of our study. Through this historical exploration, we aim to contribute to the existing body of knowledge, helping to clarify the complex relationship between FDIs and wage trends in the Dutch job market.

This analysis differentiates between male and female workers, recognizing the potential for distinct patterns within gender-specific cohorts. This delineation allows for a nuanced understanding of how FDIs exerts differential influence on wage outcomes for male and female salaried workers, providing valuable insights into potential gender disparities within the labor market.

Through this multifaceted examination, this study aspires to contribute to the broader corpus of knowledge surrounding the impacts of FDIs on wage dynamics, offering valuable implications for policymakers and practitioners navigating the complex terrain of economic policy formulation within the Dutch context.

Literature Review Related to the Current Situation of FDIs Evolution in Netherlands

Situated at the heart of Europe, the Netherlands serves as a vital gateway to the main European markets and its central location provides businesses with easy access to a large consumer base and enables efficient distribution across the continent. The country, renowned for its high quality of life and thriving business environment (Fischer et al, 2017; Hecke et al, 2018; Tay et al, 2015), stands as a premier destination for both personal and professional pursuits.

Positioned as the sixth-largest economic force within the Eurozone and a pivotal global exporter, the country's economic prowess is evident. Its strong inclination towards trade exposes it to the ebbs and flows of the global economic environment (Cauwenberge et al, 2019; Van Dam, 2016). While recent years saw robust growth, owing to Europe's recovery, the Dutch economy confronted headwinds. Factors including global trade uncertainties, the Brexit process, and the profound impact of the COVID-19 pandemic led to some contraction (Antonides & van Leeuwen, 2021; De Haas et al, 2020; Mogi & Spijker, 2022).

We need to take into consideration the constant action of Dutch government to pursue an expand fiscal policy, aiming to stimulate economic growth and development (Cimadomo, 2016, Schakel et al, 2016). Notably, this approach did not compromise the overall health of Dutch public finances, which consistently demonstrated budget surpluses. However, this trend experienced a reversal due to the fiscal interventions implemented in response to the economic downturn triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic. The repercussions of heightened inflation, influenced by the conflict in Ukraine (Mbah & Wasum, 2022), further influenced this shift in fiscal dynamics. This confluence of factors illustrates the intricate balance governments must navigate in maintaining fiscal stability amidst unforeseen economic challenges.

As per data provided by the Netherlands Foreign Investment Agency (NFIA), the influx of companies investing in the country has rebounded to levels akin to those observed in 2019. Specifically, a total of 423 new projects have been officially recorded, collectively representing an estimated investment value of approximately EUR 2.3 billion over the initial three-year period. Projections indicate that these initiatives are poised to generate nearly 13,400 direct employment opportunities. Notably, about 65% of the direct investment is channeled into Special Purpose Entities (SPEs) and holdings, signifying a strategic focus on specialized investment structures within the Netherlands (Lloyds Bank, 2023).

The Dutch investment policy is characterized by several key features that make it attractive to foreign investors. First and foremost, it exhibits a strong international orientation, welcoming and encouraging foreign investment (Fishman et al, 2015; Van Buren et al, 2016). Dutch companies, many of which are inherently multinational in nature (Marinova el al, 2016), often find themselves listed on foreign stock markets, underscoring the country's global economic integration.

The Netherlands is sustaining a competitive fiscal climate, which is an appealing factor for businesses looking to invest and dditionally, the country offers advanced infrastructure (Rădulescu et al, 2020) and holds a strategically advantageous location within Europe, serving as a gateway for trade and commerce.

In response to evolving security and technology concerns, the Netherlands implemented a new Foreign Direct Investments screening mechanism in 2022. This mechanism targets investments in undertakings engaged in vital processes or sensitive technology, including dual-use items and military goods. This demonstrates the country's commitment to protecting its critical infrastructure and technologies. Despite these challenges, the Netherlands continues to perform well on various global rankings. It ranks 4th out of 82 economies in the Business Environment ranking published by The Economist and 6th out of 63 in the Global Competitiveness Ranking. The financial sector in the Netherlands is highly developed (Muns, 2015), offering a range of sophisticated services and products and this facilitates efficient capital allocation and supports economic activities.The Netherlands possesses modern and well-connected communication and transport infrastructures (Milakis et al, 2017) increasing connectivity within the country and beyond, enhancing logistical efficiency and enabling smooth trade operations.

The Dutch labor force is known for its high level of education, productivity, and linguistic proficiency and this skilled and multilingual workforce is well-suited for export-oriented industries, contributing to the country's competitive edge in international trade (Marino & Keizer, 2023; Sippola et al, 2023).

The Netherlands' export portfolio is diversified, encompassing a wide range of goods and services. This diversity helps mitigate risks associated with dependence on specific industries. Moreover, the country maintains surplus external accounts, indicating a favorable balance of trade. This is attributed to export-friendly structures and well-developed infrastructure that support efficient export processes (Van Den Berg, 2022; Taherdangkoo et al, 2017).

These key assets collectively contribute to the Netherlands' economic strength and resilience, positioning it as an attractive destination for business, trade, and investment on the global stage.

While the Netherlands presents numerous advantages for foreign investments, it also grapples with certain weaknesses that may deter potential investors. The country contends with relatively elevated labor costs (Van Alden & Loots, 2022), which can impact the cost-effectiveness of doing business and this may be a consideration for companies seeking to optimize operational expenses.

The Dutch domestic market is relatively small in comparison to larger economies (Hooren, 2018) and the size constraint may limit the growth potential for businesses targeting primarily local consumers.

The Dutch economy is closely intertwined with the broader global economic climate, with a particular reliance on the stability and performance of the European Union (EU) and the fluctuations or uncertainties in these economic conditions can potentially impact business operations.

The Dutch banking sector's dependency on wholesale financing and real estate may pose challenges, and this reliance can expose the financial sector to risks associated with market fluctuations, particularly in real estate (Kunt et al, 2021).

Despite these weaknesses, it's important to note that the Netherlands has implemented various policies and initiatives to address these concerns. Moreover, the country's strengths in areas such as stable political and macroeconomic environments, developed infrastructure, and a skilled workforce continue to make it an attractive destination for FDIs. Companies evaluating investment opportunities in the Netherlands should carefully consider these factors in their decision-making process.

The Dutch government has established various forms of financial support to incentivize economic growth, innovation, and sustainability (Brandsen & Pape, 2015; Safarov, 2019). These measures encompass grants, tax incentives, guarantees, credits, participations, and subordinated loans, all geared towards stimulating innovation, sustainable foreign investment, and entrepreneurship.

One noteworthy initiative is the WBSO, or the Research and Development Act. Administered by the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy, this program provides an R&D tax credit to entrepreneurs. Its primary objective is to encourage companies to allocate resources towards research and development efforts, effectively reducing the associated costs (Lloyds Bank, 2023).

Furthermore, the Energy Investment Allowance (EIA) enables companies to deduct 45% of the investment expenditure related to energy-saving equipment from their taxable profits. This deduction is in addition to the customary depreciation allowances, providing an additional financial incentive for energy-efficient investments.

In line with environmental sustainability goals, the Environmental Investment Deduction (MIA) allows companies to deduct a portion of their investment costs (up to 36%) for environmentally-friendly initiatives. This deduction complements the regular investment tax deductions, further encouraging businesses to invest in sustainable practices (Ibidem). These incentives serve as valuable tools for businesses looking to contribute to the country's economic and environmental objectives while simultaneously benefiting from financial advantages.

Notable programs like the WBSO R&D tax credit provide companies with a tangible incentive to invest in research and development, thus lowering the associated costs. Additionally, initiatives such as the Energy Investment Allowance (EIA) and the Environmental Investment Deduction (MIA) further encourage businesses to adopt energy-efficient and environmentally-friendly practices, contributing to both economic and environmental objectives.

By offering these diverse forms of financial support, the Dutch management style demonstrates its commitment to creating an environment conducive to business growth, innovation, and sustainable practices. These measures not only benefit companies operating within the Netherlands but also contribute to the broader goals of economic prosperity and environmental stewardship. They stand as powerful tools in attracting and nurturing businesses that align with the country's vision for a thriving and sustainable future.

Method of Research

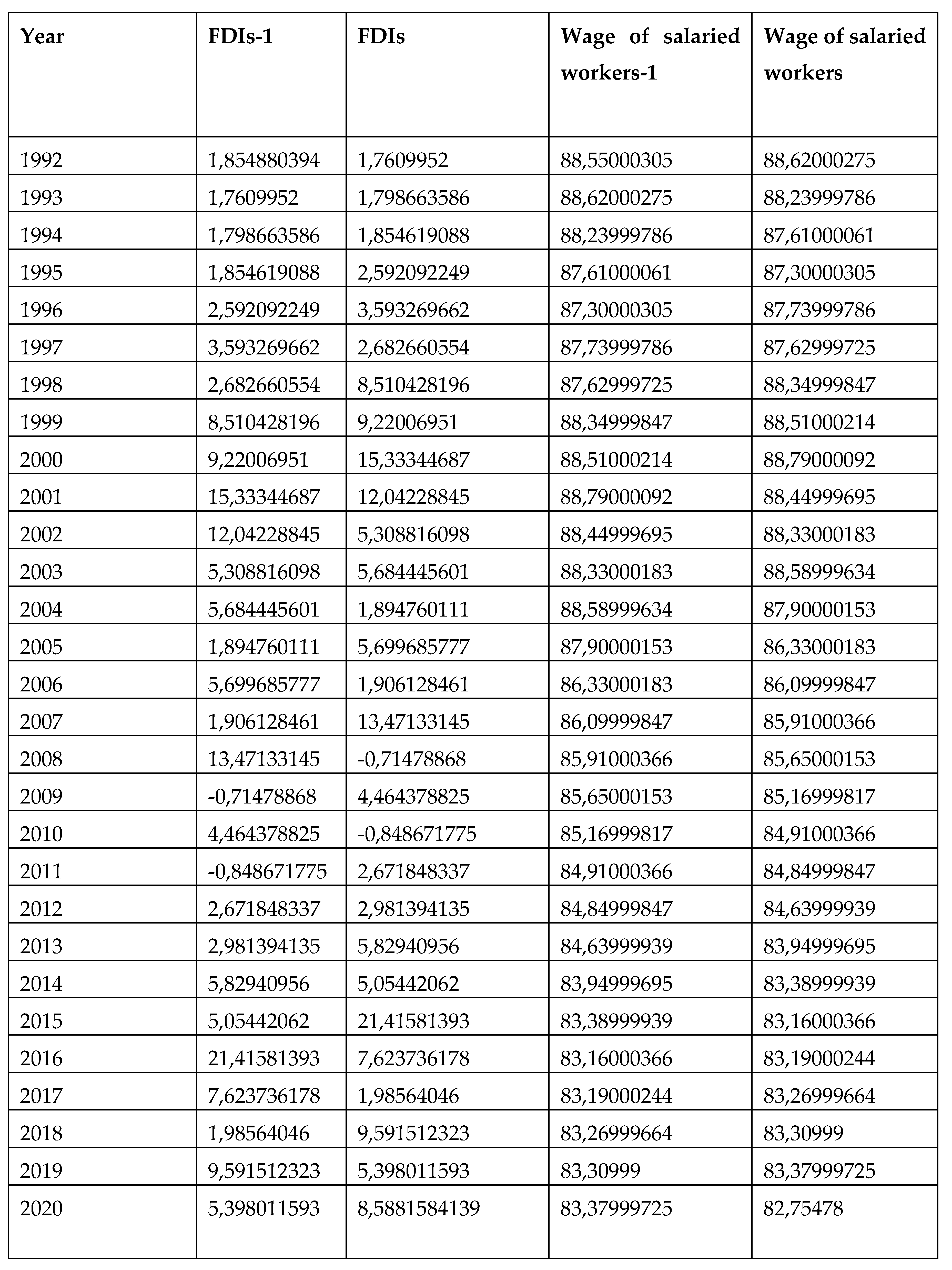

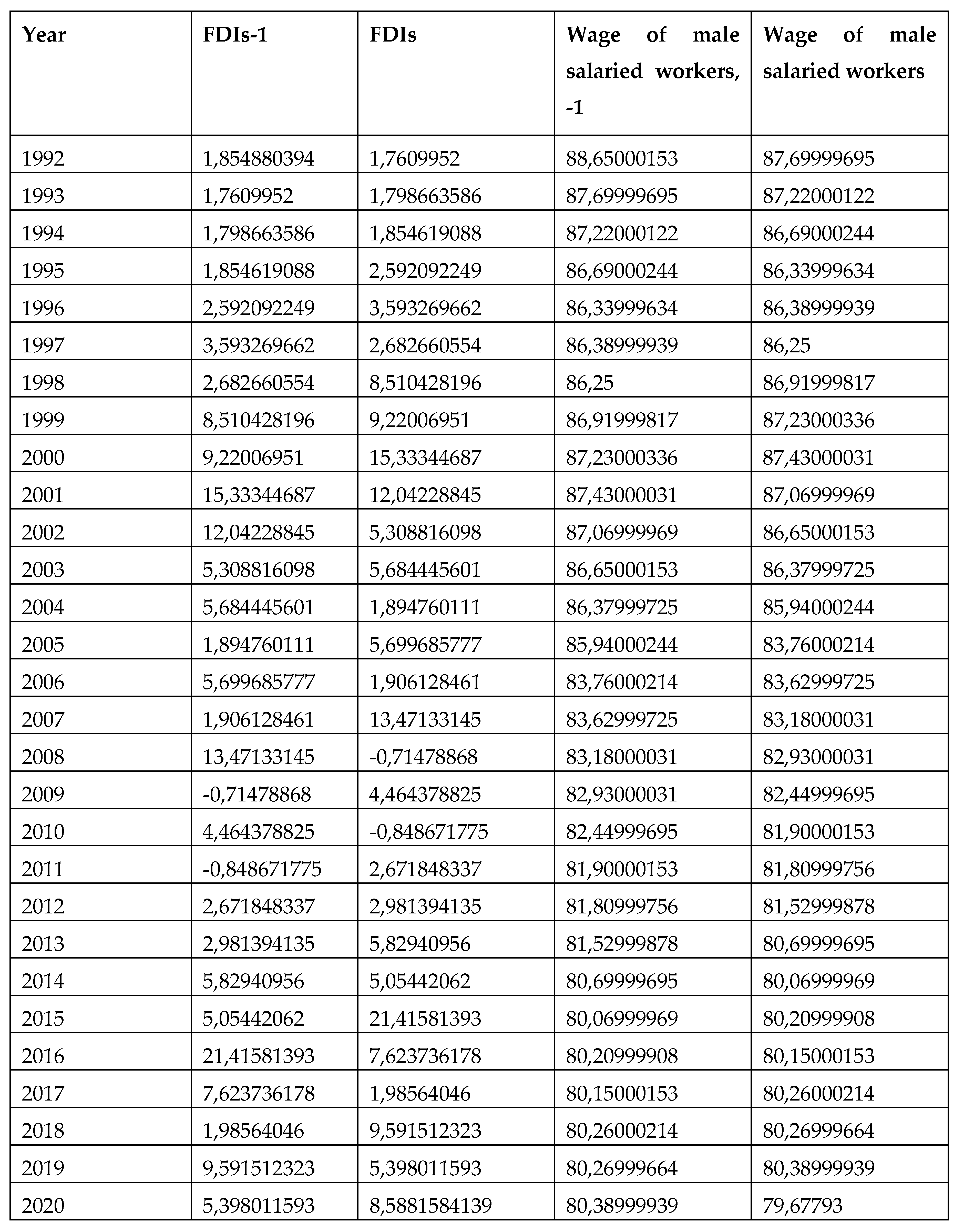

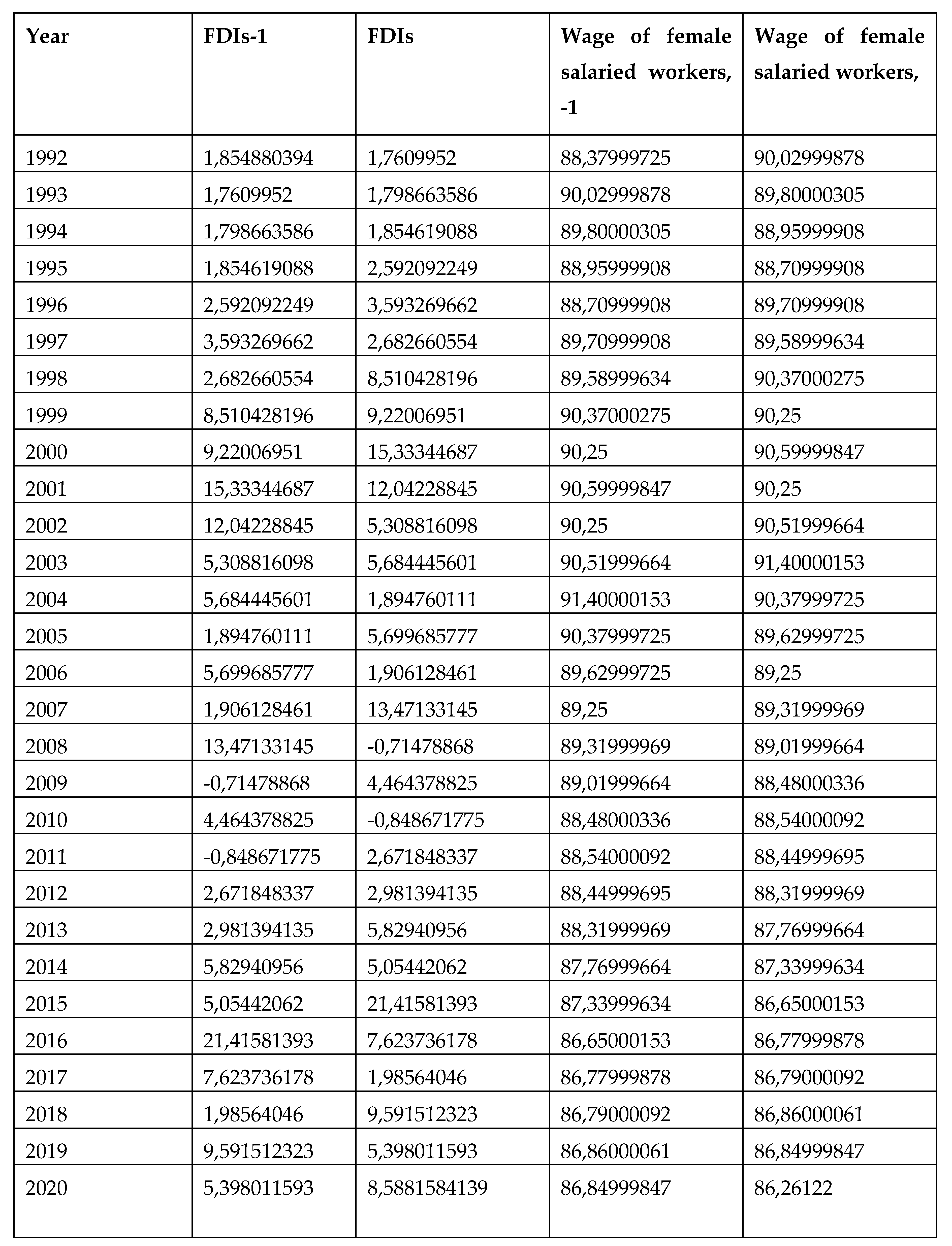

The forthcoming analysis will scrutinize the potential correlations between the operational efficacy of FDIs and the trajectory of wage developments among salaried employees in the Netherlands. It is important to note that all statistical data employed in our analyses have been meticulously sourced from authoritative international databases, such as: UNCTAD and the World Bank. Based on these sets of data, our research hypothesis are:

Hypothesis 1: There is a significant linear relationship between the levels of FDIs and wage outcomes in the Netherlands, indicating that increases in FDIs are linked to wage dynamics for salaried workers.

Hypothesis 2: FDIs influence wage growth among male and female salaried workers in the Netherlands to the same extent.

Hypothesis 3: Wage changes in the Netherlands are not significantly correlated with fluctuations in FDIs.

It will be investigated the influence of FDIs on the wages of salaried workers and for a more accurate analysis, we will study the dependence of wages of salaried workers at time n on time n-1 and on FDIs levels at time n and n-1.

A set of statistical indicators will be employed to assess the validity of the selected model. Specifically, the coefficient of determination, denoted as R-squared, will be examined. R-squared elucidates the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that can be accounted for by the variations in the independent variables within the model. It is important to take into consideration that any unexplained variance is attributable to factors not encompassed by the model and collectively contributes to the remaining portion, which amounts to 100% of the total variance.

The empirical correlation coefficient, denoted as Multiple R, serves as an indicator of potential linear interdependence between the variables under consideration. In assessing this coefficient, it is imperative to compare its value with the critical correlation coefficient for the given sample size. In our specific case, covering the period from 1992 to 2020, our dataset comprises 28 observations. It is established that if Multiple R surpasses the threshold of 0.381, it signifies a discernible linear relationship between the variables in question. This critical threshold has been determined based on the sample size and is fundamental for interpreting the significance of the correlation.

The significance of the Adjusted R-Square, also known as the corrected multiple determination coefficient, lies in its role as a model improvement when new variables are introduced.

If the Adjusted R-Square increases upon the inclusion of a variable, it indicates that the variable contributes positively to the model's explanatory power and is likely to be retained. Conversely, if the Adjusted R-Square decreases upon the inclusion of a variable, it suggests that the variable does not significantly enhance the model's explanatory capacity and may be considered for exclusion.

In our analysis, it is important to consider the selected confidence level, represented by α. The significance of P-values cannot be overstated, as they indicate the likelihood of encountering a test statistic as unusual as the one derived from the sample data, assuming the null hypothesis is true. If the P-value is lower than the 1-α threshold, it confirms the substantial impact of the variable on the underlying process.

The confidence intervals, delineated as [Lower α%, Upper β%], encapsulate the range of plausible values for the coefficients. If the interval includes zero, it implies that the null hypothesis pertaining to the respective coefficient cannot be convincingly disproven. In such instances, it is advisable to remove of the variable from the model, as its contribution may not be statistically discernible. This rigorous evaluation process ensures that the model retains only the most pertinent and influential variables for accurate predictive power.

As a consequence, our investigation will scrutinize the interdependencies involving wages of salaried workers under three distinct scenarios.

In our regression analysis, let it be known that α, β, γ, and δ are real-valued parameters. Our objective is to identify the regression model that yields the highest value of Adjusted R-Square. To this end, we will focus on the variables Wn and Wn-1, denoting the mean wages of salaried workers in the respective years n and n-1. Likewise, FDIsn and FDIn-1 represent the mean Foreign Direct Investments in the years n and n-1, respectively.

Furthermore, WMn and WMn-1 mirror the same significance as Wn and Wn-1, but with regard to male workers, while WFn and WFn-1 hold the same connotation, but in the context of female workers. This notation framework provides a clear delineation of the variables under consideration, enabling a precise and comprehensive evaluation of the regression models.

Model 1, as expressed in Equation (1) delves into the influence of both current and preceding FDIs levels, along with the effect of prior wage levels. This model offers insights into how preceding conditions of FDIs and wages shape present wage outcomes.

Model 2, represented by Equation (2), focuses in on the interplay between past FDIs levels and earlier wage outcomes, without considering FDIs in the current year. This configuration specifically isolates the impact of historical FDIs on wage outcomes from previous years.

Lastly, Model 3, outlined in Equation (3), investigates the influence of present FDIs levels and lagged wage levels on current wage outcomes, excluding consideration of lagged FDIs. This configuration elucidates the effect of ongoing FDIs on the most recent wage trends. These three distinct models enable a comprehensive exploration of the multifaceted relationships between FDIs and wage dynamics.

The methodological approach described here is well-aligned with our overarching research goals, which center on delving into the nuanced interplay between FDIs and wage trends, with a specific emphasis on gender-related dimensions in the Netherlands. This strategy enables us to systematically investigate whether the influence of FDIs on wages exhibits uniformity across genders or if discernible patterns emerge. Through this analytical lens, we aim to identify potential disparities and fluctuations in wage levels between male and female workers, thereby offering valuable insights into any differential effects that FDIs may exert on gender-specific wage outcomes.

Evaluating FDIs Effects: The Case Study of the Netherlands' Wages Evolution Landscape

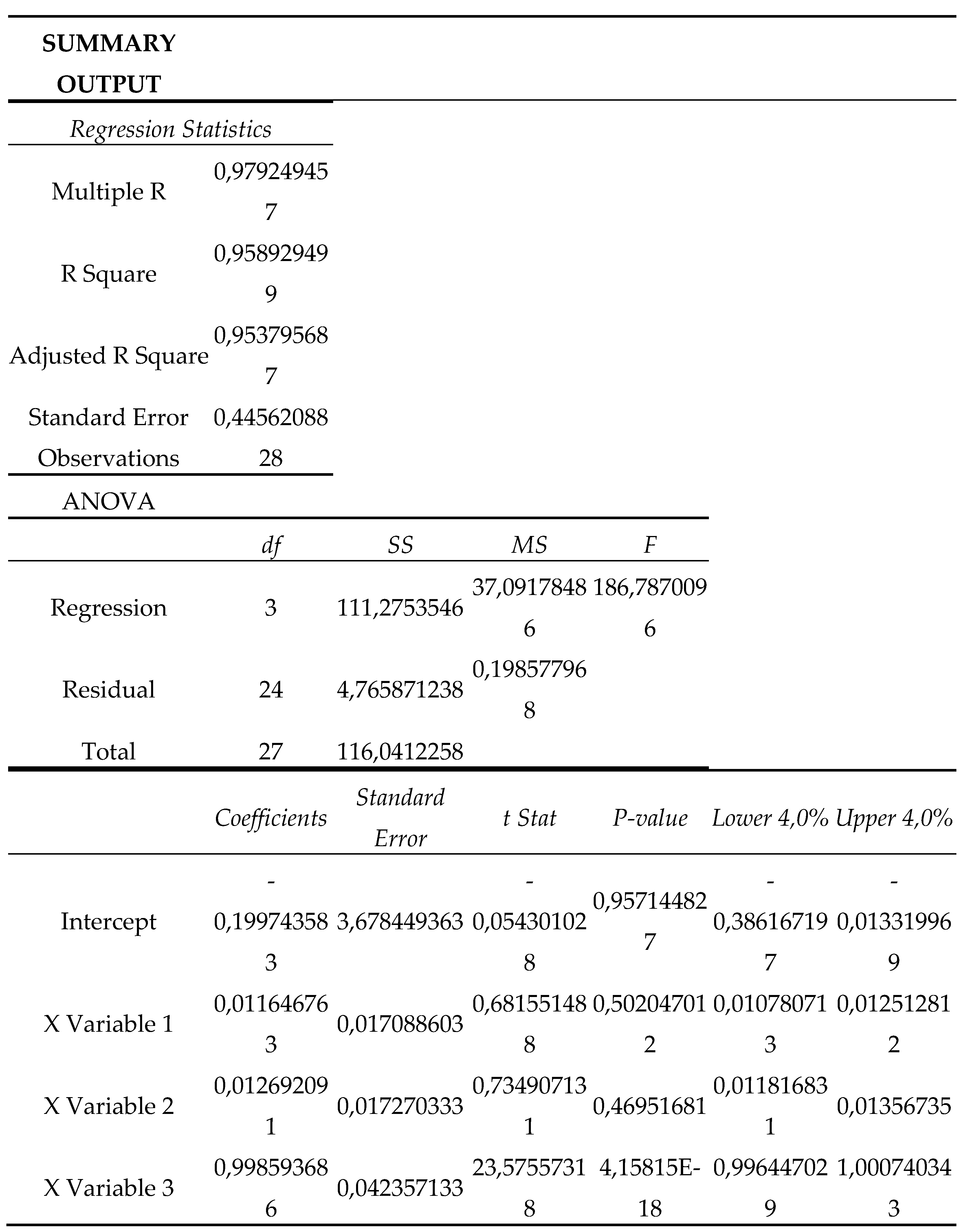

The analysis for Netherlands shows that the best model is:

Wn=0,011646763FDIn-1+0,012692091FDIn+0,998593686Wn-1-0,199743583+ε

The model demonstrates a commendable level of explanation, accounting for approximately 95.89% of the variance observed in the dependent variable, and substantial percentage signifies a robust relationship between the variables within the model.

The value of Multiple R reinforces the notion of a discernible linear dependence between the variables. This observation substantiates the validity of our modeling approach and underscores the presence of a significant correlation among the key factors under examination.

A pivotal aspect of our analysis lies in the evaluation of P-values. The notable maximum P-value, surpassing 4%, attests to the rejection of the null hypothesis with a level of confidence that exceeds conventional thresholds. This observation implies a high degree of statistical significance in the relationship between FDI levels and wages of salaried workers in the Netherlands.

The regression equation quantifies the impact of FDIs on wages, indicating that a one percent increase in FDIs in the current year is associated with a minimum but discernible 0.01% increase in the wages of salaried workers in the Netherlands. While this effect may appear modest at first glance, it underscores the nuanced nature of economic relationships, where even marginal changes can bear tangible consequences.

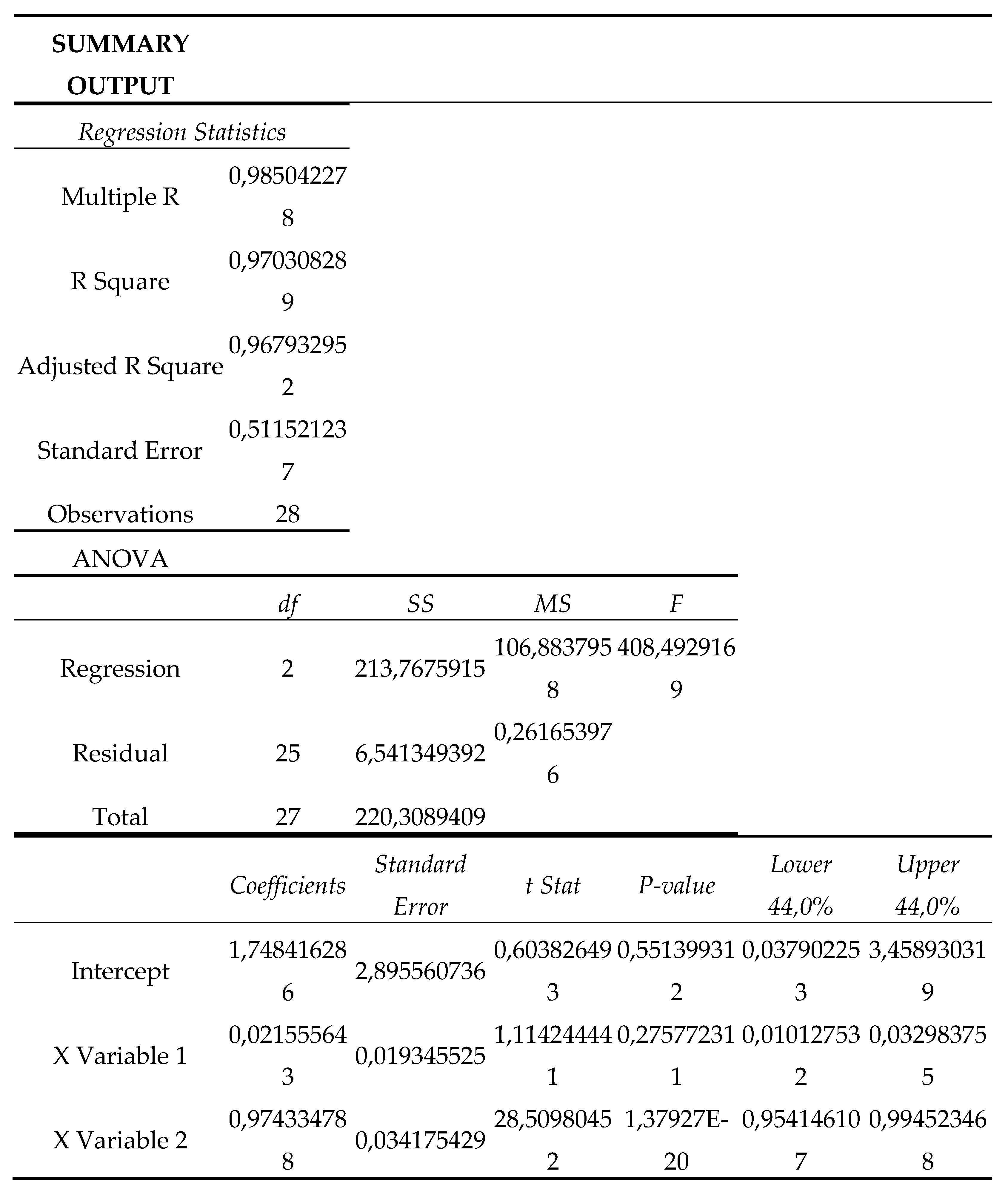

Considering now the corresponding data of wages of male salaried workers we obtain:

WMn=0,021555643FDIn-1+0,974334788WMn-1+1,748416286+ε

The model's explanatory power, accounting for approximately 97.03% of the variance, signifies an impressive level of precision in capturing the nuanced dynamics at play. This high degree of explanation underscores the relevance and reliability of the model in elucidating the economic interactions between FDIs and wage outcomes.

The observed linear dependence, as indicated by the value of Multiple R, affirms the presence of a significant correlation between FDIs and wages, and this suggests that fluctuations in FDIs levels are closely associated with corresponding shifts in wage levels among male salaried workers.

The rejection of the null hypothesis with a probability exceeding 44% based on the maximum P-value may initially appear counterintuitive. However, it is essential to recognize that in statistical hypothesis testing, higher P-values can indicate the strength of evidence against the null hypothesis. In this context, the relatively high P-value indicates a strong rejection of the null hypothesis, and this suggests a high level of confidence in the validity of the relationship between FDIs and male salaried workers' wages.

The regression equation's prediction, stating that a one percent increase in FDIs in the previous year corresponds to a 0.02% increase in the wages of Dutch male salaried workers, underscores the impact that FDIs can have on this specific demographic group. While this effect may seem modest, it highlights the potential significance of FDIs in influencing the economic well-being of male salaried workers in the Netherlands.

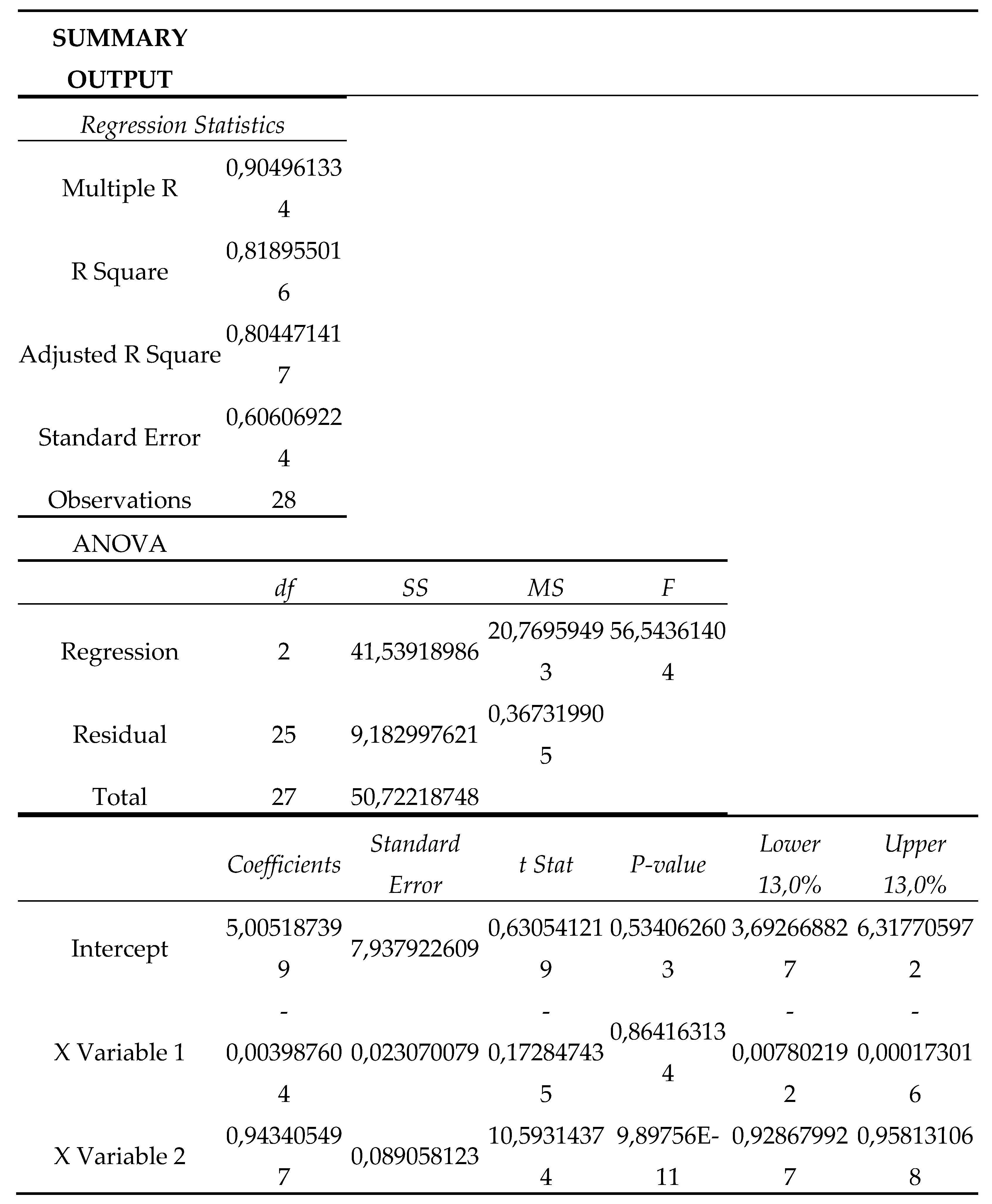

Considering the corresponding data for the wages of female salaried workers we obtain:

WFn=-0,003987604FDIn+0,943405497WFn-1+5,005187399+ε

The model's explanatory power, accounting for approximately 81.90% of the variance, signifies a degree of precision in capturing the underlying dynamics. The observed linear dependence, as indicated by the value of Multiple R, affirms the presence of a significant correlation between FDIs and wages. This implies that changes in FDIs levels are closely associated with corresponding shifts in wage levels among female salaried workers. The relatively high P-value, exceeding 13%, in rejecting the null hypothesis may initially appear counterintuitive. However, it is important to recognize that in statistical hypothesis testing, higher P-values can indicate the strength of evidence against the null hypothesis. In this context, the relatively high P-value indicates a rejection of the null hypothesis, further reinforcing the statistical robustness of our findings. This suggests a high level of confidence in the validity of the relationship between FDIs and female salaried workers' wages.

The regression equation's prediction, stating that a one percent increase in FDIs in the current year corresponds to a 0.003% decrease in the wages of female salaried workers in the Netherlands, highlights an intriguing result. While this effect size may seem small, it underscores the potential significance of FDIs in influencing the economic well-being of female salaried workers in the Netherlands. The negative sign indicates that, in this specific context, an increase in FDIs is associated with a slight decrease in wages for female salaried workers.

In sum, this analysis advances our understanding of the intricate interplay between FDIs and wages, specifically among female salaried workers in the Netherlands.

Discussions, Recommendations, Limitations and Future Research

The influence of FDIs on wage dynamics is a complex interplay of various factors, and this complexity is further compounded when considering gender disparities in wage outcomes.

The regression analysis reveals noteworthy insights into the differential impact of FDIs on wage dynamics among male and female salaried workers in the Netherlands. For Dutch male workers, a one percent increase in FDIs in the previous year corresponds to a 0.02% increase in wages. While seemingly modest, this effect size underscores the potential significance of FDIs in bolstering the economic well-being of male salaried workers in the Netherlands.

Conversely, for female salaried workers, a one percent increase in FDIs in the current year corresponds to a 0.003% decrease in wages. This result is particularly intriguing, as it highlights a distinct pattern. Despite the small effect size, it underscores the potential significance of FDIs in shaping the economic outcomes of female salaried workers in the Netherlands. The negative sign suggests that, in this specific context, an increase in FDIs is associated with a slight decrease in wages for female salaried workers. This nuanced finding warrants further investigation to understand the underlying mechanisms at play.

The findings gleaned from the analysis of statistical indicators offer valuable insights into the relationship between FDIs and wages of salaried workers in the Netherlands. The substantial explanatory power of the model, accounting for approximately 95.89% of the variance, suggests that a significant proportion of wage variation can be attributed to FDIs and related factors. This high level of explanation underscores the relevance and reliability of the model in capturing the underlying dynamics.

The value of Multiple R further supports the notion of a discernible linear dependence between FDIs and wages. This indicates that changes in FDIs levels are indeed associated with corresponding shifts in wage outcomes among salaried workers. This observation reaffirms the presence of a meaningful relationship between these variables, underscoring the potential impact that foreign investments may exert on the wages of the workforce.

The examination of P-values yields an important insight into the statistical significance of our findings. The fact that the maximum P-value exceeds 4% and leads to the rejection of the null hypothesis is a noteworthy observation. This implies a high level of confidence in the validity of our results, providing a robust foundation for asserting the relationship between FDIs and wages. This statistical significance further bolsters the credibility of our analysis.

The regression equation, a key outcome of our study, quantifies the effect of FDIs on wages. And the observed relationship indicates that a one percent increase in FDIs in the current year corresponds to a marginal 0.01% increase in the wages of salaried workers in the Netherlands. Even small changes in FDIs levels can lead to discernible shifts in wage outcomes, emphasizing the potential impact of foreign investments on the economic well-being of salaried workers.

The robust statistical support for the relationships identified in this analysis lays a strong foundation for informed policy considerations and further research in this domain. It also underscores the importance of continued examination of the complex interplay between FDIs and wages in the broader economic context.

The findings from the analysis of statistical indicators provide valuable insights into the distinct dynamics between FDIs and wage outcomes for male and female salaried workers in the Netherlands.

Hypothesis 1 states that here is a significant linear relationship between the levels of FDIs and wage outcomes in the Netherlands, indicating that increases in FDIs are linked to wage dynamics for salaried workers.

For male workers, the model demonstrates a high explanatory power, suggesting that a substantial portion of wage variation can be attributed to FDIs levels and related factors. The observed linear dependence between variables affirms the presence of a significant correlation, indicating that changes in FDIs levels are closely associated with corresponding shifts in wage levels among male salaried workers. The rejection of the null hypothesis with a high level of confidence further substantiates the statistical robustness of these findings. The regression equation's prediction highlights a positive association, indicating that an increase in FDIs in the previous year corresponds to an increase in wages for Dutch male salaried workers.

Conversely, for female workers, the model also demonstrates a noteworthy explanatory power, though it is slightly lower compared to the male cohort. This suggests that FDIs is a determinant of wage outcomes for female salaried workers, albeit to a slightly lesser extent. The observed linear dependence indicates a meaningful correlation between FDIs and wages among female salaried workers. The rejection of the null hypothesis, though at a slightly lower confidence level, still supports the validity of the relationship. Interestingly, the regression equation for female workers highlights a negative association, implying that an increase in FDIs in the current year corresponds to a decrease in wages. These findings validate Hypothesis, demonstrating a significant linear relationship between FDIs and wage outcomes in the Netherlands.

Hypothesis 2 posits that FDIs influence wage growth among male and female salaried workers in the Netherlands to the same extent. However, the empirical findings from the regression analysis indicate a more nuanced outcome, leading to a partial validation of this hypothesis, primarily for male workers. Hypothesis 2 is validated for male salaried workers, as FDIs significantly influence their wage growth in a positive manner. The hypothesis is only partially validated for female salaried workers, where the effect of FDIs on wages is negative rather than positive. This disparity underscores the need for extra investigation into the gender-specific mechanisms through which FDIs impact wage outcomes in the Netherlands, revealing a more complex relationship than initially hypothesized.

Hypothesis 3 suggests that wage changes in the Netherlands are significantly correlated with fluctuations in FDIs, but is not validated based on the regression analysis findings. The wage changes in the Netherlands are not significantly correlated with fluctuations in FDIs, as evidenced by the differing effects on male and female workers. This lack of a consistent relationship suggests that other factors, beyond FDIs, may play a more substantial role in determining wage dynamics in the Dutch labor market.

These distinct findings underscore the importance of considering gender-specific dynamics in the relationship between FDIs and wages. It is evident that FDIs impacts male and female salaried workers differently, potentially due to variations in labor market structures, industry concentrations, or other contextual factors. These results hold significant policy implications, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions to ensure equitable wage outcomes for both genders in the context of FDIs-driven economic environments. This study contributes to the broader field of research on the socio-economic impacts of FDIs, shedding light on the nuanced interactions between international capital flows and labor market outcomes within specific demographic groups.

One of the pivotal factors contributing to the divergence in wage impacts is occupational segregation and gender-based differences in industry and occupation choices can significantly shape how FDIs influence wage trends. If certain sectors receiving high levels of FDIs traditionally favor male employment, this may lead to divergent wage outcomes between genders. The composition of industries influenced by FDIs plays a crucial role and sectors with intensive FDIs involvement may offer distinct wage dynamics, which in turn can lead to varying impacts on male and female workers. For example, industries with advanced technology and specialized skills requirements may demonstrate different wage patterns for male and female employees.

Differences in labor force participation rates among males and females may constitute another key factor and if more males are employed in sectors heavily influenced by FDIs, they may experience more pronounced wage effects compared to their female counterparts.

Improving the impact of FDIs on Dutch salaries requires a multifaceted approach that addresses various economic, social, and policy factors.

Enhancing educational and vocational training programs to equip the workforce with the specialized skills demanded by FDIs-intensive industries may encourage continuous learning and upskilling to ensure that employees remain competitive in a rapidly evolving global economy.

Implementing policies that reduce gender-based wage disparities and foster a more inclusive work environment, could encourage the recruitment and advancement of women in sectors influenced by FDIs.

Create an enabling environment for SMEs to thrive, as they are often more embedded in local economies and have the potential to generate more inclusive growth and encourage knowledge-sharing and technology transfer between foreign investors and local businesses should stimulate innovation and productivity gains.

Sustaining robust labor market regulations that strike a balance between protecting workers' rights will provide flexibility for businesses to operate efficiently and will offer incentives for businesses to invest in R&D activities, which can lead to higher value-added production and potentially higher wages.

Collaborate with the private sector to jointly develop and finance projects that can stimulate economic growth and job creation and prioritize environmentally sustainable projects that not only benefit the environment but also create jobs and contribute to economic growth.

Regularly assess the impact of FDIs on wages and adjust policies accordingly to ensure that they are achieving the desired outcomes can be achieved by adopting a holistic approach that combines these strategies. Based on the above assumptions, Netherlands can enhance the positive impact of FDIs on salaries, fostering sustainable economic growth and prosperity for its citizens.

While the analysis provides valuable insights into the relationship between FDIs and wages, it is essential to recognize the inherent limitations in the model's explanatory power, assumptions, and the scope of the study period. These factors should be taken into consideration when interpreting and applying the findings.

Firstly, although the model explains a substantial percentage (95.89%) of the variance, it's crucial to recognize that there may be other unaccounted factors influencing wage dynamics. The model's ability to capture all relevant variables is inherently constrained, and there may be unobserved or omitted variables that contribute to wage fluctuations.

Secondly, the observed linear dependence between variables, as indicated by the Multiple R value, may not fully encapsulate the complexity of real-world economic relationships. Non-linear interactions or higher-order effects might be at play, which the current model does not account for; therefore, the model's linear assumption might not capture all nuances in the data.

Additionally, the regression equation's prediction that a one percent increase in FDI leads to a 0.01% increase in wages, while statistically significant, suggests a relatively small effect size. This implies that the influence of FDIs on wages might be subtle in comparison to other factors that affect wage levels. Therefore, the practical significance of this relationship may be limited.

For future research specifically focused on the Netherlands, the following suggestions can be considered as investigating how FDIs impacts wage trends in different regions within the Netherlands. Analyze if there are significant variations in the effects of FDIs on wages between urban and rural areas or between provinces and explore how FDIs affects wages in key industries that are prominent in the Dutch economy can provide sector-specific insights that are relevant to the Netherlands' economic landscape.

The future intention is to examine whether FDIs contributes to wage inequality within the Dutch labor market and also investigate if foreign capital has varying effects on wages across different income brackets or skill levels. Evaluating potential policy measures that the Dutch government could implement to enhance the positive impacts of FDIs on wages while mitigating any potential negative consequences.

Very important is to analyze if FDIs inflows contribute to skill development and human capital accumulation among the Dutch workforce, potentially leading to higher wages in the long run.

Assessing the sustainability aspects of FDIs in the Netherlands, considering factors like environmental impact, social responsibility, and the implications for sustainable wage growth could explore the types of FDIs that are most beneficial for the Dutch economy in terms of job creation and wage enhancement.

In sum, this comprehensive analysis significantly advances our understanding of the intricate dynamics between FDIs and wage trends within the Netherlands. These findings hold crucial implications for policymakers and practitioners, offering valuable insights into how FDIs can impact wage outcomes for salaried workers. Moreover, this study contributes to the broader field of research on the socio-economic impacts of FDIs, emphasizing the importance of considering gender-specific effects in shaping effective policy frameworks.

Conclusion

Understanding the intricate web of factors contributing to differential wage impacts of FDIs on male and female salaried workers in the Netherlands requires a nuanced and multifaceted analysis.

In summary, the provided text articulates a rigorous and systematic approach to examining the intricate relationships between FDIs and wage trends among salaried workers in the Netherlands. The research methodology outlined encompasses a diachronic perspective, allowing for a comprehensive analysis of historical trends and their impact on contemporary wage dynamics.

Overall, the provided texts demonstrate a methodical approach to studying the impact of FDIs on wage trends in the Netherlands and the analytical framework outlined ensures a comprehensive evaluation, facilitating meaningful insights for policymakers, economists, and practitioners in navigating the dynamics of international capital flows and labor market outcomes.

The analysis of statistical indicators offers vital insights into the nexus between Foreign Direct Investments and the wages of salaried workers in the Netherlands. The model's high explanatory power and the observed linear dependence between variables emphasize the relevance of this relationship within the Dutch economic landscape.

The robust rejection of the null hypothesis bolsters the statistical validity of our findings, reinforcing the assertion of a meaningful association between FDIs levels and wage outcomes specifically within the context of the Netherlands.

The regression equation's prediction underscores the potential impact of FDIs on the economic well-being of salaried workers in the Netherlands, offering valuable implications for economic policies tailored to the Dutch market.

The empirical model, exhibiting a substantial explanatory power, underscores the precision with which it captures the variance in wage outcomes attributed to FDI levels and related factors. This high degree of explanation attests to the relevance and reliability of the model in elucidating the underlying economic dynamics

As we reflect on the findings, it becomes evident that the influence of FDIs extends beyond economic metrics; it encompasses livelihoods, opportunities, and societal structures. The intricate dialectics between international capital flows and wage dynamics evoke deep reflections on the nature of economic interconnectedness in a globalized world.

In this context, one is compelled to consider the ethical dimensions of economic policies and investment strategies. How do we ensure that the benefits of FDIs are equitably distributed, fostering inclusive growth? How do we mitigate potential disparities in wages, especially with respect to gender-related aspects? These questions delve into the heart of not only economic theory but also our collective moral compass.

Moreover, this study underscores the impermanence of economic phenomena. The trajectories of FDIs and wage trends are not static; they evolve over time, shaped by a multitude of factors including geopolitical shifts, technological advancements, and social paradigms. This cyclical nature invites us to contemplate the broader rhythms of human progress and the adaptability required to navigate an ever-changing economic landscape.

In conclusion, this diachronic exploration serves as a testimony to the enduring relevance of economic research in understanding the intricate relation between global capital and individual prosperity. It beckons us to view economic phenomena not merely as statistical abstractions, but as lived experiences with profound implications for human evolution. As we move forward, may we approach the nexus of FDIs and wage trends with a discerning eye and a commitment to the holistic well-being of all stakeholders in the economic tapestry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Emanuel Stefan Marinescu; Software, Ioan Gina; Investigation, Angelica Nicoleta Neculaesei Onea; Writing – review & editing, Sergiu Ionel Pirju; Supervision, Rodica Pripoaie; Project administration, Sirbu Carmen.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Sources: UNCTAD and World Bank

References

- Antonides, G. & Van Leeuwen, E. Covid-19 crisis in the Netherlands: “Only together we can control Corona”. Mind & Society 2021, 20, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojnec,S. & Fertő,I. Globalization and Outward Foreign Direct Investment, Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 2018, 54, 88–99. [CrossRef]

- Bacovic, M. , Jacimovic, D. Bozovic, M.L. & Ivanovic, M. The Balkan Paradox: Are Wages and Labour Productivity Significant Determinants of FDI Inflows?, Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 2021, 23, 144–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandsen, T. & Pape, U. The Netherlands: The Paradox of Government–Nonprofit Partnerships. Voluntas 2015, 26, 2267–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimadomo, J. Real-time data and fiscal policy analysis: A survey of the literature. Journal of Economic Surveys 2016, 30, 302–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haas, M. , Faber, R. Hamersma, M. How COVID-19 and the Dutch ‘intelligent lockdown’ change activities, work and travel behaviour: Evidence from longitudinal data in the Netherlands, Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives 2020, 6, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doytch, N. & Uctum,M. Globalization and the environmental impact of sectoral FDI, Economic Systems 2016, 40, 582–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doeleman,H.J., Steven, H. & Ahaus,K. The moderating role of leadership in the relationship between management control and business excellence, Total Quality Management& Business Excellence 2012, 23–26, 591-611. [CrossRef]

- De Jong, E. Vijge,M.J. From Millennium to Sustainable Development Goals: Evolving discourses and their reflection in policy coherence for development, Earth System Governance 2021, 7. [CrossRef]

- Fishman, E.; Paul Schepers, and Carlijn Barbara Maria Kamphuis. Dutch Cycling: Quantifying the Health and Related Economic Benefits. American Journal of Public Health 2015, 105, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.J.; Inoue, K.; Matsuda, A. Cross-cultural comparison of breast cancer patients’ Quality of Life in the Netherlands and Japan. Breast Cancer Res Treat 166, 459–471. [CrossRef]

- Hooren, F. Intersecting Social Divisions and the Politics of Differentiation: Understanding Exclusionary Domestic Work Policy in the Netherlands, Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 2018, 25, 92–117. [CrossRef]

- Hou,L. , Li, Q., Wang,Y., Yang,X. Wages, labor quality, and FDI inflows: A new non-linear approach. Economic Modelling 2021, 102, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunt, A.; Pedraza, A.; Ruiz-Ortega,C. Banking sector performance during the COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Banking & Finance 2021, 133, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long,T. ; Blok,V. & Coninx,I. Barriers to the adoption and diffusion of technological innovations for climate-smart agriculture in Europe: Evidence from the Netherlands, France, Switzerland and Italy. Journal of Cleaner Production 2016, 112, 9–21. [CrossRef]

- Marinova,J. ; Plantenga,J. & Remery,C. Gender diversity and firm performance: Evidence from Dutch and Danish boardrooms, The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2016, 27, 1777–1790. [CrossRef]

- Marino, S. , & Keizer, A. Labour market regulation and the demand for migrant labour: A comparison of the adult social care sector in England and the Netherlands. European Journal of Industrial Relations 2023, 29, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbah, R. E. , & Wasum, D. F. Russian-Ukraine 2022 War: A Review of the Economic Impact of Russian-Ukraine Crisis on the USA, UK, Canada, and Europe. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal 2022, 9, 144–153. [Google Scholar]

- Mogi, R. & Spijker, J. The influence of social and economic ties to the spread of COVID-19 in Europe. Journal of Population Research 2022, 39, s12546–s021. [Google Scholar]

- McNeely, J.A. Nature and COVID-19: The pandemic, the environment, and the way ahead. Ambio 2021, 50, 767–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milakis, D. Snelder, M., Arem, B. & Homem de Almeida Correia, G. Development and transport implications of automated vehicles in the Netherlands: Scenarios for 2030 and 2050. European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research 2017, 17 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, B. & Khan, M.K. Foreign direct investment inflow, economic growth, energy consumption, globalization, and carbon dioxide emission around the world. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2021, 28, 55643–55654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muns, S. A Financial Market Model for the Netherlands: A Methodological Refinement. Netspar Discussion Paper 2015, 9, 2015–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen,D. Inward foreign direct investment and local wages: The case of Vietnam’s wholesale and retail industry, Journal of Asian Economics 2019, 65, 101–134. [CrossRef]

- Pegkas, P. The impact of FDI on economic growth in Eurozone countries. The Journal of Economic Asymmetries 2015, 12, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rădulescu, M.A.; Leendertse, W. & Arts, J. Conditions for Co-Creation in Infrastructure Projects: Experiences from the Overdiepse Polder Project (The Netherlands). Sustainability 2020, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose,A: & Garcilazo,E. Quality of Government and the Returns of Investment: Examining the Impact of Cohesion Expenditure in European Regions, Regional Studies 2015, 49, 1274–1290. [CrossRef]

- Safarov,I. Institutional Dimensions of Open Government Data Implementation: Evidence from the Netherlands, Sweden, and the UK, Public Performance & Management Review 2019, 42, 305–328. [CrossRef]

- Sippola, M. , Jonker-Hoffrén, P., & Ojala, S. The varying national agenda in variable hours contract regulation: Implications for the labour market regimes in the Netherlands and Finland. European Journal of Industrial Relations 2023, 0, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdangkoo, M. , Ghasemi, K. & Beikpour, M. The role of sustainability environment in export marketing strategy and performance: A literature review. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2017, 19, 1601–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, L. , Kuykendall, L., Diener, E. (2015) Satisfaction and Happiness – The Bright Side of Quality of Life. In: Glatzer, W., Camfield, L., Møller, V., Rojas, M. (eds) Global Handbook of Quality of Life. International Handbooks of Quality-of-Life. Springer, Dordrecht. [CrossRef]

- Schakel, H. C.; Jeurissen, P. & Glied, S. The influence of fiscal rules on healthcare policy in the United States and the Netherlands. International Journal of Health Planning Management 2017, 32, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, M. Z. , Esquivias, M., & Arifin, N. Foreign direct investment and wage spillovers in the Indonesian manufacturing industry. Buletin Ekonomi Moneter Dan Perbankan 2022, 25, 125–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dam, P. Moralizing Postcolonial Consumer Society: Fair Trade in the Netherlands, 1964–1997. International Review of Social History 2016, 61, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Andel, W. & Loots, E. Measures for the betterment of the labor market position of non-standard working regimes in the cultural and creative sector in the Netherlands, International Journal of Cultural Policy 2022, 28, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, M. , "Free lunch or vital support? Export promotion in The Netherlands", Applied Economic Analysis 2022, 30, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Buren, N.; Demmers, M.; Van der Heijden, R.; Witlox, F. Towards a Circular Economy: The Role of Dutch Logistics Industries and Governments. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hecke, N. , Claes, C., Vanderplasschen, W. Conceptualisation and Measurement of Quality of Life Based on Schalock and Verdugo’s Model: A Cross-Disciplinary Review of the Literature. Social Indicators Research 2018, 137, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cauwenberge, A.; Vancauteren, M.; Braekers, R. ; Vandemaele,S. International trade, foreign direct investments, and firms’ systemic risk : Evidence from the Netherlands, Economic Modelling 2019, 81, 361–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhihai, Z. Developing a model of quality management methods and evaluating their effects on business performance, Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 2000, 11, 129–137. [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, J & Qamruzzaman, M. Do financial development, FDI, and globalization intensify environmental degradation through the channel of energy consumption: Evidence from belt and road countries, Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29, 2753–2772. [CrossRef]

- Web sources Global Competitiveness Ranking. https://worldcompetitiveness.imd.org/countryprofile/NL/wcy (24.09/2023).

- Lloyds Bank https://www.lloydsbanktrade.com/en/market-potential/netherlands/investment?vider_sticky=oui (21.09.2023).

- Netherlands Residence by Investment Program https://www.orangevisas.nl/?gclid=Cj0KCQjwpc-oBhCGARIsAH6ote--541YEFLMWCkQfjLwdItKPPp4SD8hasD56lvL_XYPYkKTqumSuk0aAj7JEALw_wcB (22.09.2023).

- Netherlands Foreign Investment Agency (NFIA) https://investinholland.com/ (22.09.2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).