Submitted:

10 September 2024

Posted:

10 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Collection

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Overall Survival and Analysis of Influencing Factors

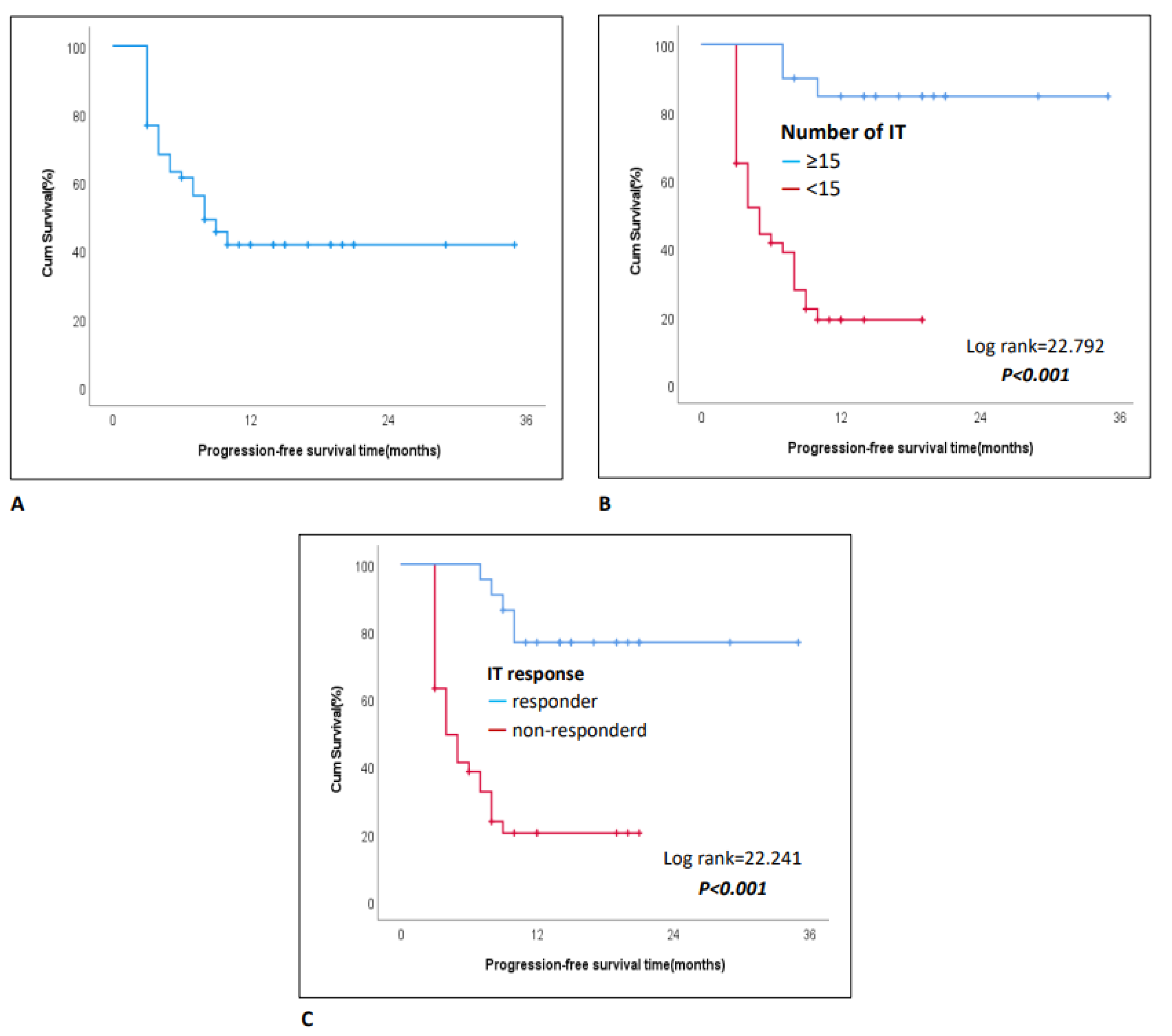

3.3. Progression-Free Survival and Analysis of Influencing Factors

3.4. Treatment Response and Associated Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int Globocan 2022 version 1.1 - 08.02. 2024.

- Lung and Bronchus Cancer—Cancer Stat Facts. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Singh, H.; Kanapuru, B.; Smith, C.; Fashoyin-Aje, L.A.; Myers, A.; Kim, G.; Pazdur, R. FDA Analysis of Enrollment of Older Adults in Clinical Trials for Cancer Drug Registration: A 10-Year Experience by the US Food and Drug Administration. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 10009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias R, Odejide O. Immunotherapy in Older Adults: A Checkpoint to Palliation? Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book. 2019, 39, e110–20. [Google Scholar]

- Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Squamous-Cell Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Non-squamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rittmeyer, A.; Barlesi, F.; Waterkamp, D.; Park, K.; Ciardiello, F.; von Pawel, J.; Gadgeel, S.M.; Hida, T.; Kowalski, D.M.; Dols, M.C.; et al. Atezolizumab versus Docetaxel in Patients with Previously Treated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (OAK): A Phase 3, Open-Label, Multicentre Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 1540–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ageing. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/ageing#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Ferrara, R.; Mezquita, L.; Auclin, E.; Chaput, N.; Besse, B. Immunosenescence and Immunecheckpoint Inhibitors in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients: Does Age Really Matter? Cancer Treat. Rev. 2017, 60, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghaei, H.; Gettinger, S.; Vokes, E.E.; Chow, L.Q.M.; Burgio, M.A.; de Castro Carpeno, J.; Pluzanski, A.; Arrietac, O.; Frontera, O.A.; Chiari, R.; et al. Five-Year Outcomes from the Randomized, Phase Iii Trials Checkmate 017 and 057: Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Previously Treated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbst, R.S.; Garon, E.B.; Kim, D.W.; Cho, B.C.; Gervais, R.; Perez-Gracia, J.L.; Han, J.Y.; Majem, M.; Forster, M.D.; Monnet, I.; et al. Five Year Survival Update From KEYNOTE-010: Pembrolizumab Versus Docetaxel for Previously Treated, Programmed Death-Ligand 1–Positive Advanced NSCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021, 16, 1718–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crinò, L.; Bidoli, P.; Delmonte, A.; Grossi, F.; De Marinis, F.; Ardizzoni, A.; Vitiello, F.; Garassino, M.; Parra, H.S.; Cortesi, E.; et al. Italian Nivolumab Expanded Access Programme: Efficacy and Safety Data in Squamous Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2017, 12, 1336–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli G, De Toma A, Pagani F, et al. Efficacy and safety of immunotherapy in elderly patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2019, 137, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinier, O.; Besse, B.; Barlesi, F.; Audigier-Valette, C.; Friard, S.; Monnet, I.; Jeannin, G.; Mazières, J.; Cadranel, J.; Hureaux, J.; et al. CLINIVO: Real-World Evidence of Long-Term Survival with Nivolumab in a Nationwide Cohort of Patients with Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. ESMO Open 2022, 7, 100353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juergens RA, Mariano C, Jolivet J, et al. Real-world benefit of nivolumab in a Canadian non-small-cell lung cancer cohort. Curr. Oncol. 2018, 25, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juergens R, Chu Q, Rothenstein J, et al. P2.07-029 CheckMate 169: Safety/Efficacy of Nivolumab in Canadian Pretreated Advanced NSCLC (including Elderly and PS 2) Patients. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2017, 12, 2426–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al: Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2018, 360, k793.

- Helissey C, Vicier C, Champiat S: The development of immunotherapy in older adults: New treatments, new toxicities? J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2016, 7, 325–333. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felip E, Ardizzoni A, Ciuleanu T, et al. CheckMate 171: A phase 2 trial of nivolumab in patients with previously treated advanced squamous non-small cell lung cancer, including ECOG PS 2 and elderly populations. Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 127, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spigel DR, McCleod M, Jotte RM, et al. Safety, Efficacy, and Patient-Reported Health-Related Quality of Life and Symptom Burden with Nivolumab in Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Including Patients Aged 70 Years or Older or with Poor Performance Status (CheckMate 153). J. Thorac. Oncol. 2019, 14, 1628–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang DY, Salem JE, Cohen JV, et al. Fatal Toxic Effects Associated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 1721–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient characteristics (N=60) | Category | Statistics |

|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | median (IQR, range) | 67(66-71, 65-88) |

| Sex, n(%) | Female | 13(21.7) |

| Male | 47(78.3) | |

| Comorbidity, n(%) | No | 18(30) |

| Yes | 42(70) | |

| Histology, n (%) | Adeno ca | 27(45) |

| Squamous ca | 22(36.7) | |

| Mixed | 11(18.3) | |

| Stage at Diagnosis, n (%) | Locally | 21(35) |

| Metastatic | 39(65) | |

| Number of Metastatic Sites, n (%) | Sinle | 42(70) |

| Multiorgan | 18(30) | |

| Immunotherapy (IT), n(%) | 2.line | 44(73.3) |

| 3-4.line | 16(26.7) | |

| Number of IT Cycles, n (%) | <15 | 40(66.7) |

| ≥15 | 20(33.3) | |

| Toxicity, n(%) | No | 33(55) |

| Yes | 27(45) | |

| Treatment Delay, n(%) | No | 36(60) |

| Yes | 24(40) | |

| Response to Pre-IT CT/RT, n(%) | Respondera | 22(36.7) |

| Non-responderb | 38(63.3) | |

| IT Response | Respondera | 22(36.7) |

| Non-responderb | 38(63.3) | |

| Post-IT progression, n(%) | No | 26(43.3) |

| Yes | 34(56.7) | |

| Follow-up Duration (months) | median (IQR, range) | 23(19-36, 6-82) |

| Progression-Free Survival (months) | median (IQR, range) | 8(3-14, 3-35) |

| Univariablea | Multivariableb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | Category | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P |

| Age (year) | <70 | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥70 | 1.16(0.56-2.41) | 0.690 | 1.03(0.37-2.82) | 0.958 | |

| Sex | Female | Reference | Reference | ||

| Male | 0.99(0.42-2.29) | 0.974 | 1.34(0.39-4.57) | 0.643 | |

| Comorbidity | No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.73(0.33-1.63) | 0.447 | 1.09(0.35-3.41) | 0.881 | |

| Histology | Adenoca | Reference | Reference | ||

| Other | 1.91(0.92-3.97) | 0.084 | 5.31(1.74-16.18) | 0.003 | |

| Stage at Diagnosis | Locally | Reference | Reference | ||

| Metastatic | 1.60(0.76-3.35) | 0.216 | 13.43(3.69-48.96) | <0.001 | |

| Number of Metastatic Sites | Single | Reference | Reference | ||

| Multiorgan | 2.10(1.03-4.31) | 0.042 | 2.21(0.66-7.38) | 0.198 | |

| Immunotherapy (IT) | 2. line | Reference | Reference | ||

| 3-4.line | 1.26(0.46-3.42) | 0.650 | 1.26(0.46-3.42) | 0.870 | |

| Number of IT Cycles | <15 | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥15 | 0.07(0.02-0.29) | <0.001 | 0.09(0.01-0.74) | 0.024 | |

| Toxicity | No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.02(0.50-2.08) | 0.947 | 1.83(0.61-5.52) | 0.285 | |

| IT delay | No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.69(0.33-1.45) | 0.326 | 0.88(0.34-2.24) | 0.781 | |

| Response to Pre-IT CT/RT | Responderc | Reference | Reference | ||

| Non-responderd | 2.43(1.05-5.62) | 0.039 | 4.50(1.16-17.55) | 0.030 | |

| IT response | Responderc | Reference | Reference | ||

| Non-responderd | 3.65(1.50-8.89) | 0.004 | 6.89(1.30-36.56) | 0.023 |

| Univariablea | Multivariableb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | Category | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P |

| Age (year) | <70 | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥70 | 0.69(0.33-1.44) | 0.325 | 0.77(0.33-1.79) | 0.544 | |

| Sex | Female | Reference | Reference | ||

| Male | 1.16(0.50-2.66) | 0.732 | 0.62(0.21-1.80) | 0.377 | |

| Comorbidity | No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.59(0.29-1.19) | 0.141 | 0.60(0.27-1.36) | 0.219 | |

| Histology | Adenoca | Reference | Reference | ||

| Other | 1.33(0.66-2.65) | 0.426 | 1.76(0.75-4.14) | 0.194 | |

| Stage at Diagnosis | Locally | Reference | Reference | ||

| Metastatic | 0.72(0.37-1.42) | 0.340 | 0.68(0.26-1.77) | 0.427 | |

| Number of Metastatic Sites | Single | Reference | Reference | ||

| Multiorgan | 1.47(0.72-2.97) | 0.288 | 1.85(0.63-5.43) | 0.261 | |

| Immunotherapy (IT) | 2. line | Reference | Reference | ||

| 3-4. line | 1.12(0.47-2.68) | 0.792 | 1.39(0.31-6.23) | 0.666 | |

| Number of IT Cycles | <15 | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥15 | 0.10(0.03-0.34) | <0.001 | 0.13(0.03-0.54) | 0.005 | |

| Toxicity | No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.91(0.46-1.80) | 0.785 | 1.07(0.45-2.59) | 0.874 | |

| IT delay | No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.76(0.37-1.53) | 0.439 | 0.87(0.40-1.93) | 0.739 | |

| Response to Pre-IT CT/RT | Responderc | Reference | Reference | ||

| Non-responderd | 1.46(0.71-3.01) | 0.300 | 0.65(0.20-2.09) | 0.470 | |

| IT response | Responderc | Reference | Reference | ||

| Non-responderd | 6.85(2.59-18.08) | <0.001 | 7.76(2.11-28.61) | 0.002 | |

| All | Responder | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | Category | n | n(%) | OR (95% CI) | P |

| Age (year) | <70 | 39 | 12(30.8) | Reference | |

| ≥70 | 21 | 10(47.6) | 2.05(0.69-6.11) | 0.196a | |

| Sex | Female | 13 | 6(46.2) | Reference | |

| Male | 47 | 16(34) | 0.60(0.17-2.09) | 0.520b | |

| Comorbidity | No | 18 | 5(27.8) | Reference | |

| Yes | 42 | 17(40.5) | 1.77(0.53-5.88) | 0.350a | |

| Histology | Adenoca | 27 | 8(29.6) | Reference | |

| Other | 33 | 14(42.4) | 1.75(0.60-5.14) | 0.306a | |

| Stage at Diagnosis | Locally | 21 | 7(33.3) | Reference | |

| Metastatic | 39 | 15(38.5) | 1.25(0.41-3.81) | 0.694a | |

| Number of Metastatic Sites | Single | 42 | 14(33.3) | Reference | |

| Multiorgan | 18 | 8(44.4) | 1.60(0.52-4.95) | 0.413a | |

| Number of IT Cycles | <15 | 40 | 6(15) | Reference | |

| ≥15 | 20 | 16(80) | 22.67(5.60-91.71) | <0.001a | |

| Toxicity | No | 33 | 13(39.4) | Reference | |

| Yes | 27 | 9(33.3) | 0.77(0.27-2.23) | 0.628a | |

| IT delay | No | 36 | 11(30.6) | Reference | |

| Yes | 24 | 11(45.8) | 1.92(0.66-5.61) | 0.229a | |

| Response to Pre-IT CT/RT | Responder | 22 | 10(45.5) | Reference | |

| Non-responder | 38 | 12(31.6) | 0.55(0.19-1.64) | 0.282a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).