Submitted:

09 September 2024

Posted:

10 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

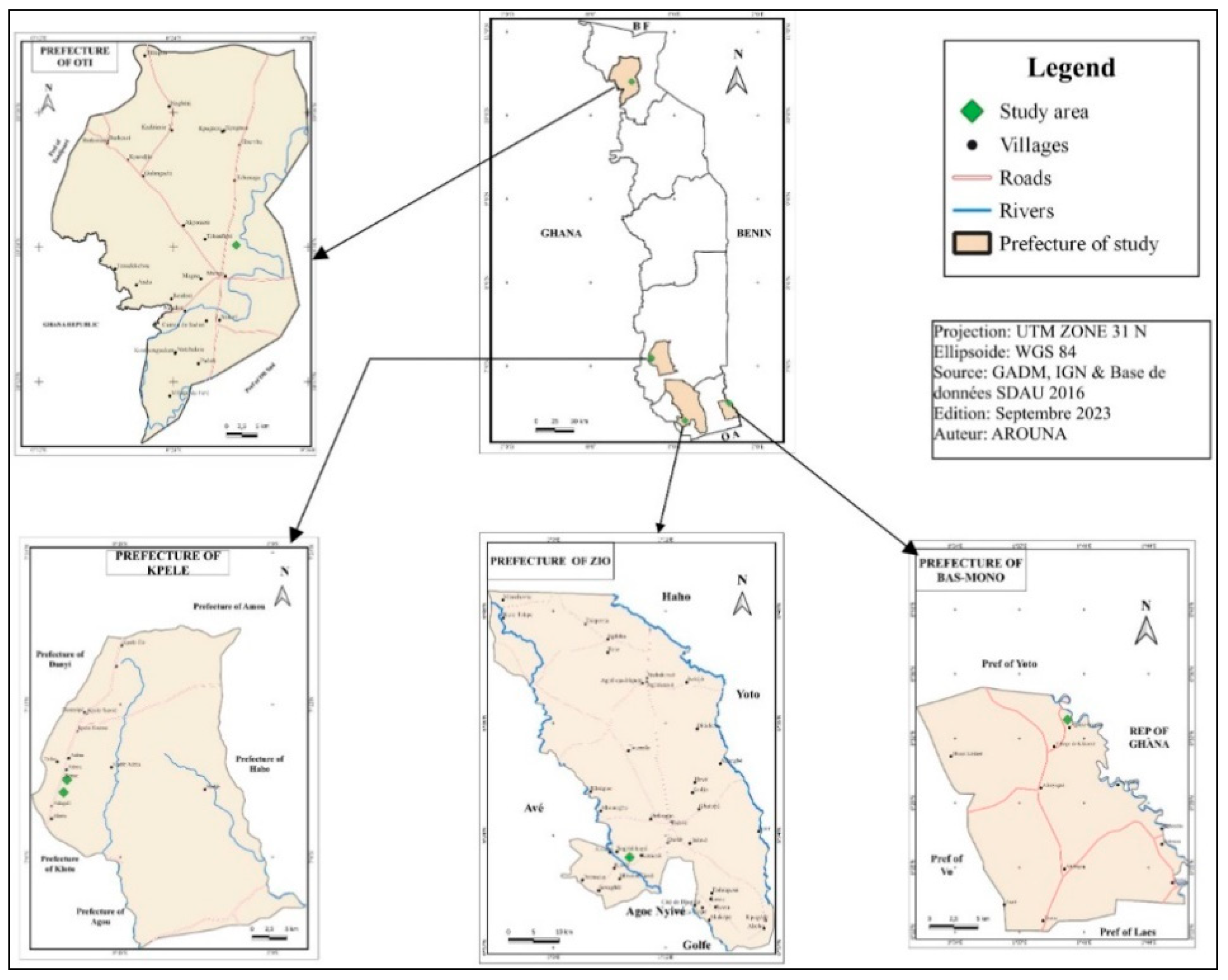

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Questionnaire, Sampling, and Data Collection

2.2.1. Questionnaire

- ▪ Rice farmers’ socioeconomic characteristics (e.g. gender, age, marital status, education level, irrigated rice production experience, type of land tenancy, membership in farmers’ cooperative, sources of income, accessing to agricultural credit, marketing information, etc.);

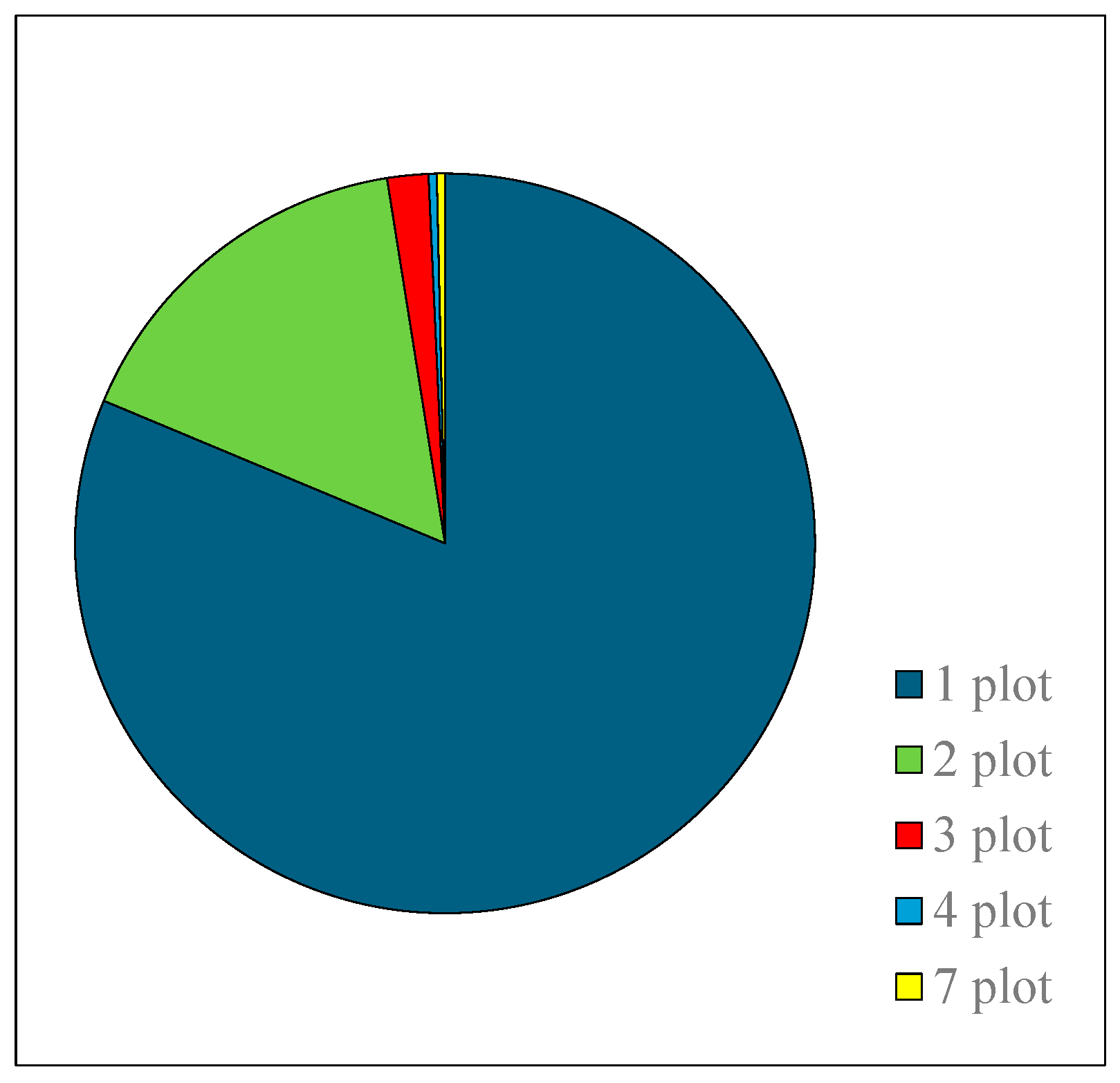

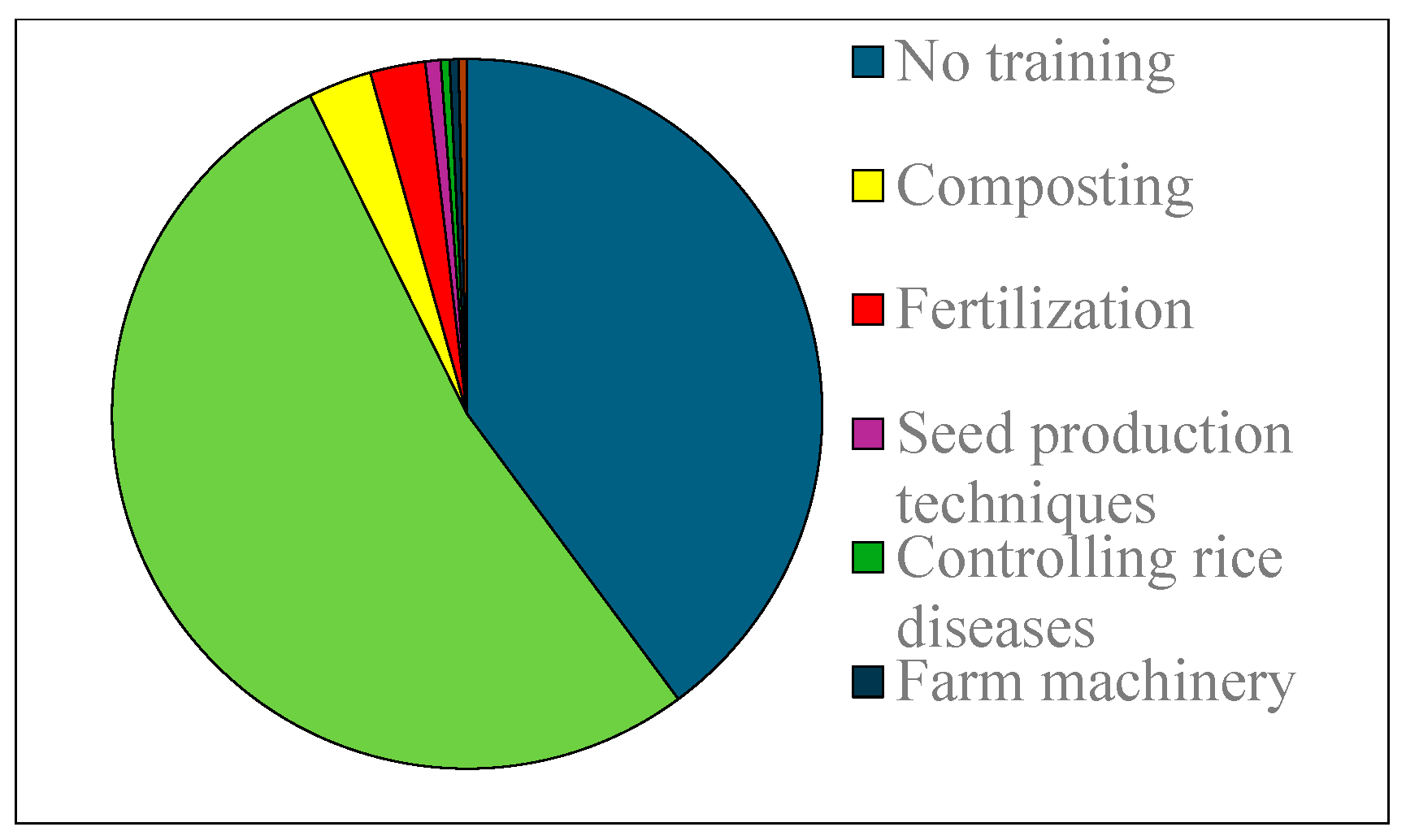

- ▪ Agronomic management practices (e.g. plots number, method of plot clearance, ploughing method, mudding method, rice seeds access, rice planting methods, weed and pest control, amount and timing of fertilization, cropping systems practice, rice production knowledge, training in rice production, labor source, agricultural extension access, etc.);

- ▪ Irrigation water management practices (e.g. training in irrigation, training on water-saving, water availability, equitable water distribution, conflicts on irrigation water, water-saving practices, water delivery method, water level above the soil, water level below the soil surface before the next irrigation, irrigation frequency, amount of irrigation water used per each application, irrigation schedule regularly respected, water available for the entire production season, drainage, etc.);

- ▪ Famers’ perception on water and agronomic practices (e.g. water productivity, knowledge of water-use-efficiency, knowledge of water-saving methods, knowledge of irrigation period and water amount applied, water shortage on the irrigation scheme, water wastage factors, effect of water deficit on rice yields, effect of excess water on rice yields, effect of excess water on fertilizer use-efficiency, drainage water using in case of water shortage, soil salinity problem, water management improving, inappropriate pesticides and fertilizers use effect on rice yield and water quality, mulches and compost use advantage, access of advisory service, etc.).

2.2.2. Sampling, Data Collection and Analysis

2.3. Conceptual Framework of the Study

3. Results

3.1. Respondents' Socio-Economic Characteristics

3.2. Agronomic Practices in Irrigation Schemes

3.2.1. Training Attended in Rice Production

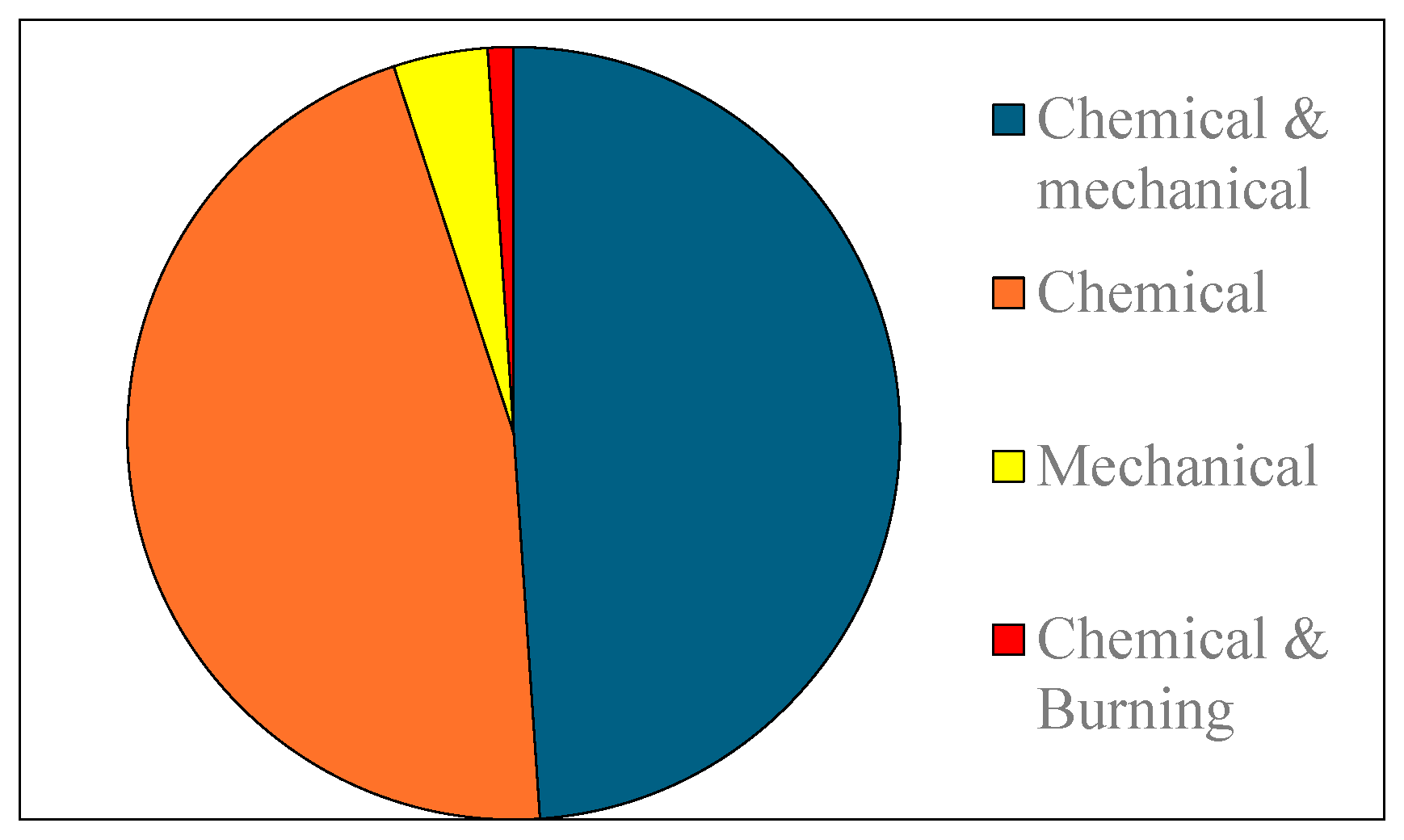

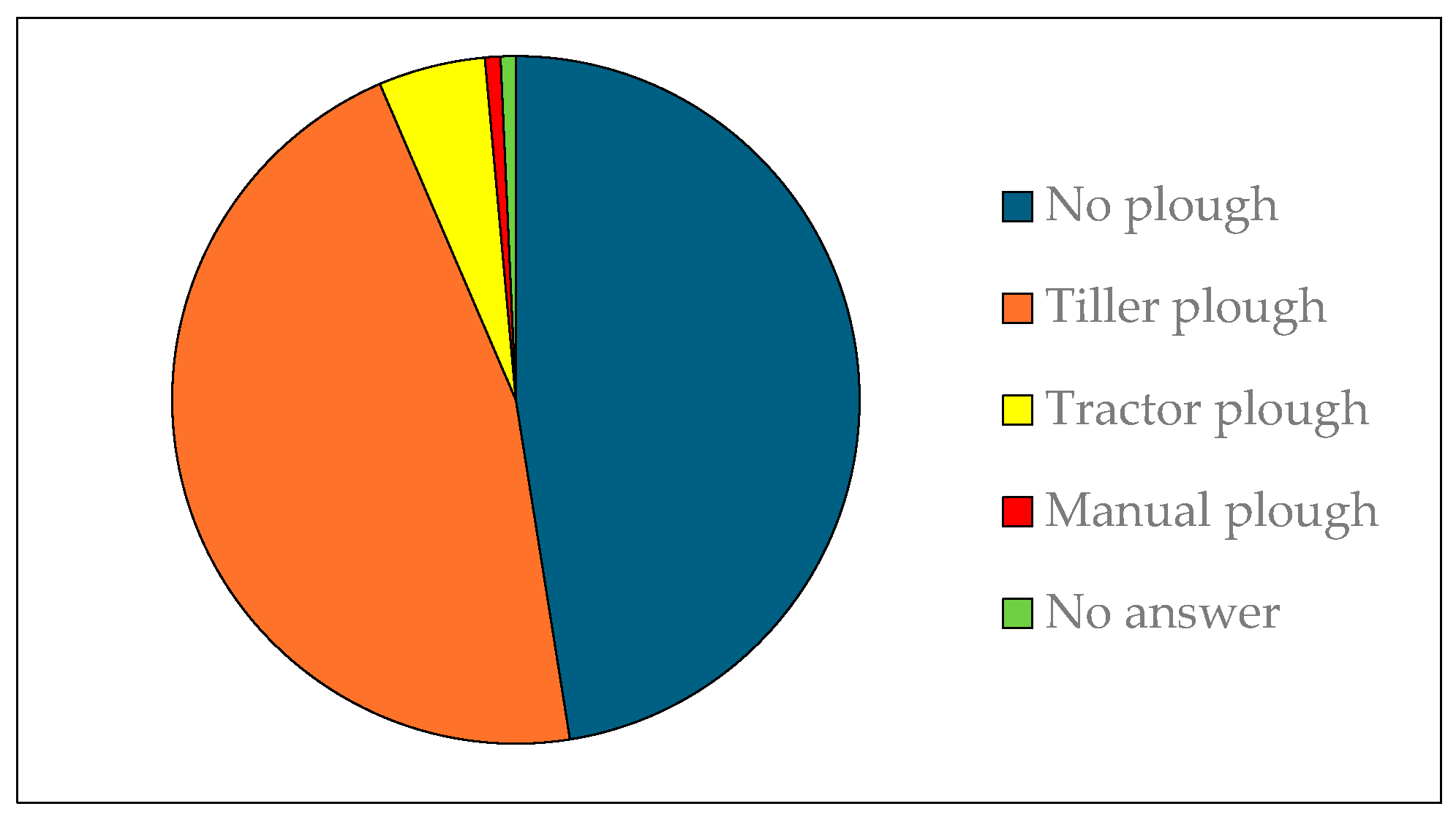

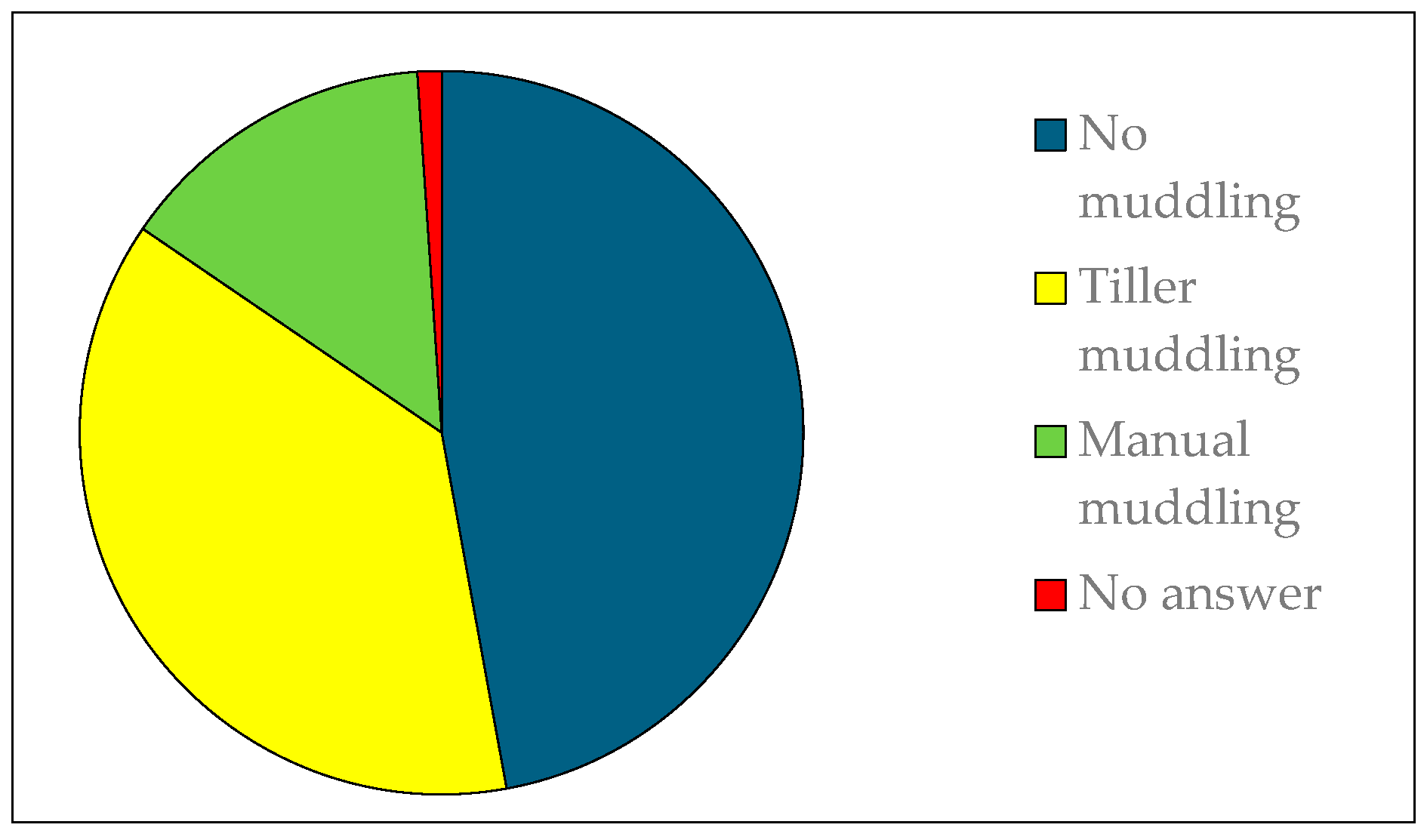

3.2.3. Soil Preparation

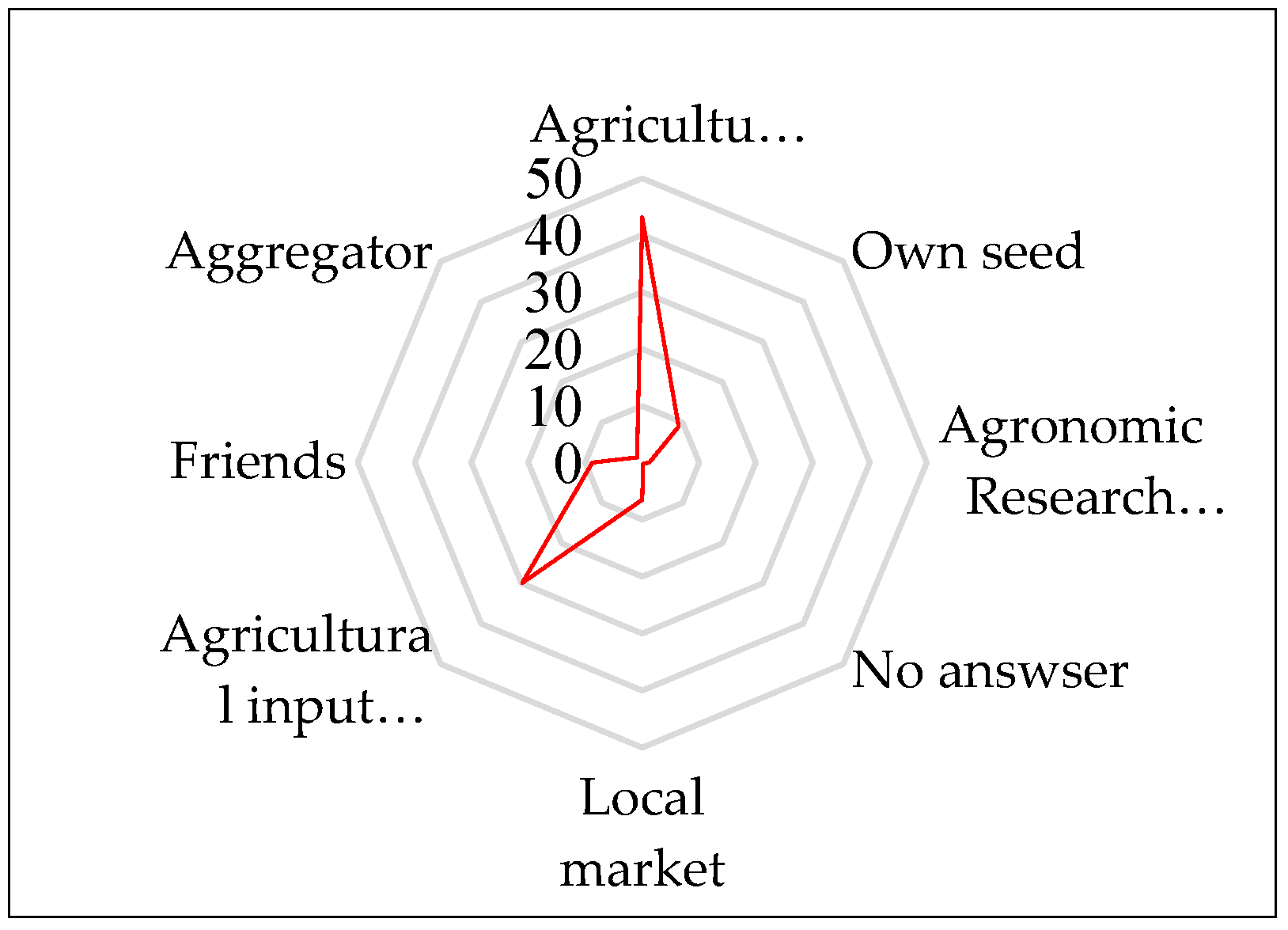

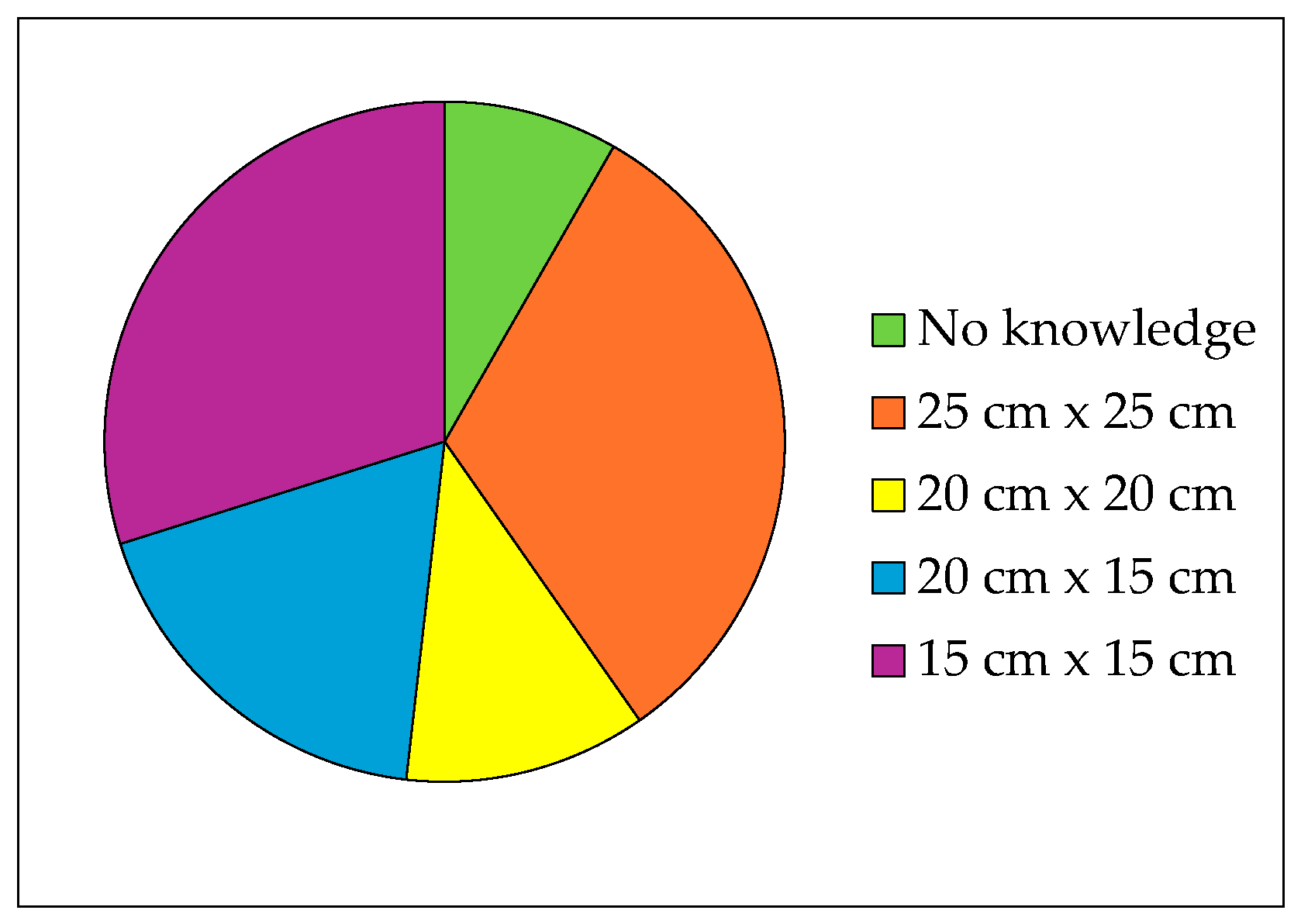

3.2.4. Setting Up the Growing Operation

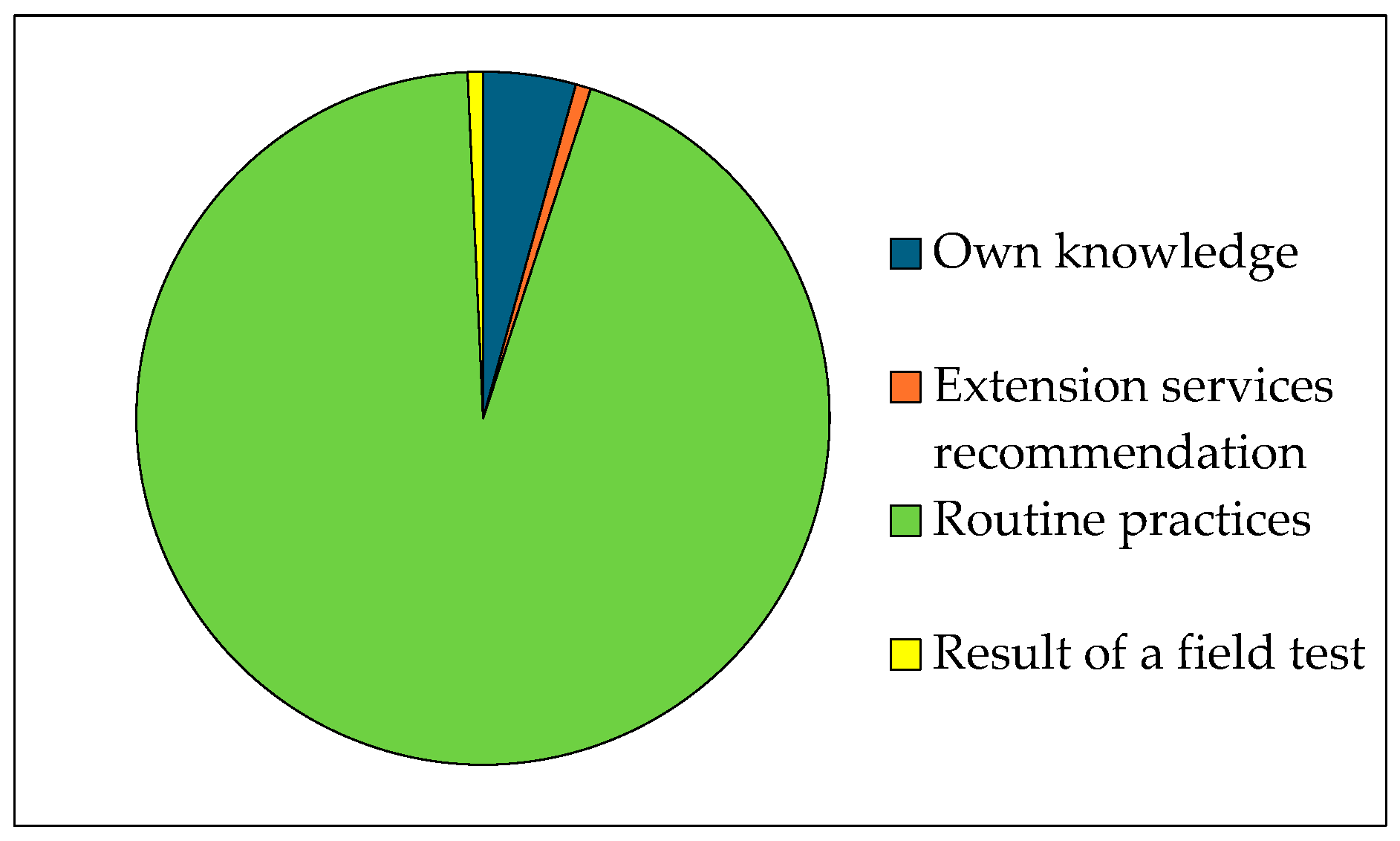

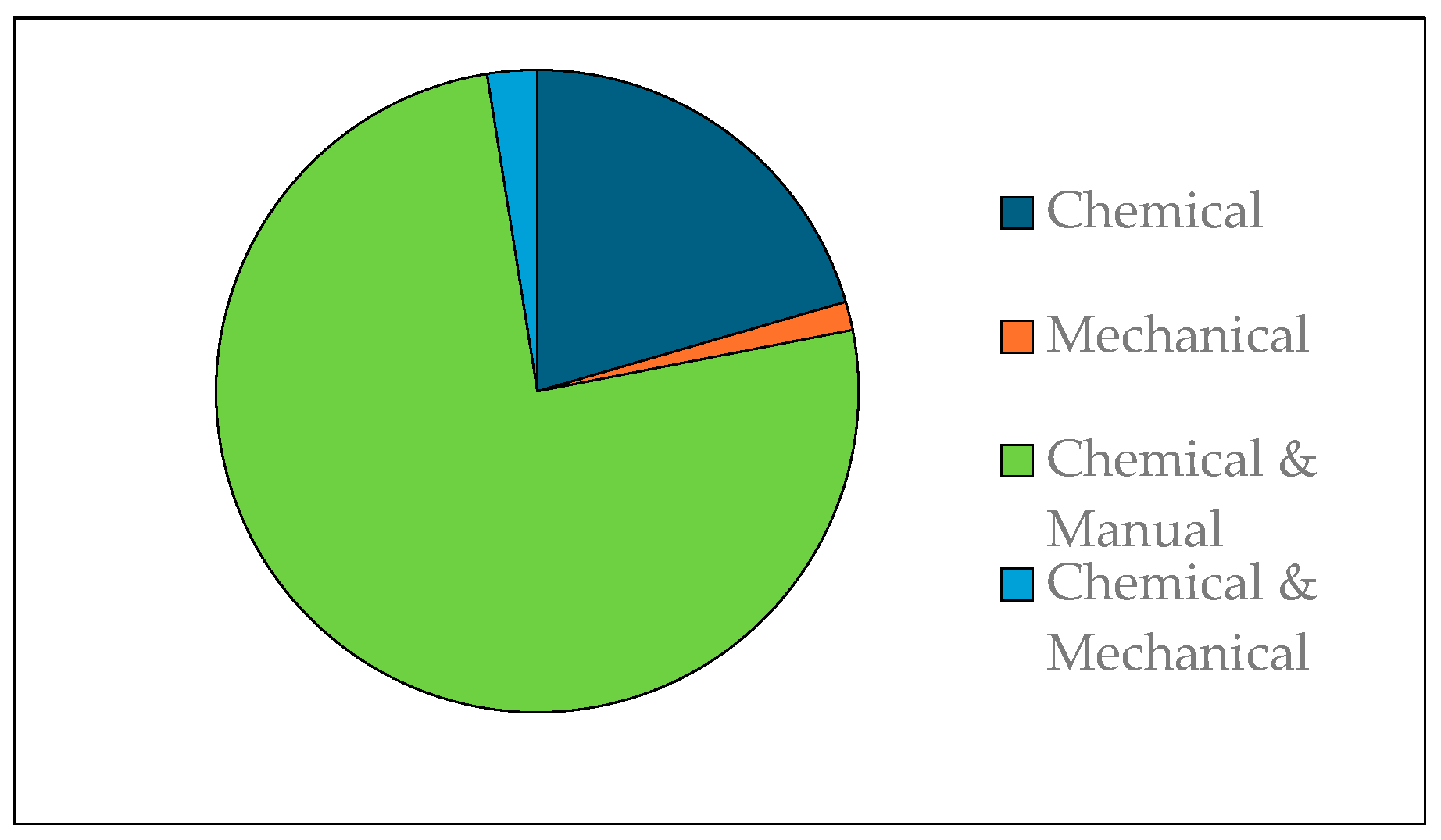

3.2.5. Fertilization and Weed Control

| Application period of Urea fertilizer | Amount applied (kg/ha) | Percentage of farmers (%) |

|---|---|---|

| One week after planting | 0 | 69,4 |

| 50 | 14,0 | |

| 100 | 14,7 | |

| 200 | 1,4 | |

| 400 | 0,4 | |

| Seven weeks after planting | 0 | 27,0 |

| 25 | 0,4 | |

| 50 | 1,8 | |

| 100 | 16,5 | |

| 150 | 11,5 | |

| 200 | 39,6 | |

| 300 | 1,4 | |

| 400 | 1,1 | |

| 500 | 0,7 | |

| Ten weeks after planting | 0 | 71,9 |

| 25 | 0,7 | |

| 50 | 15,5 | |

| 100 | 6,1 | |

| 150 | 1,4 | |

| 200 | 0,7 | |

| 300 | 0,4 | |

| 500 | 1,8 |

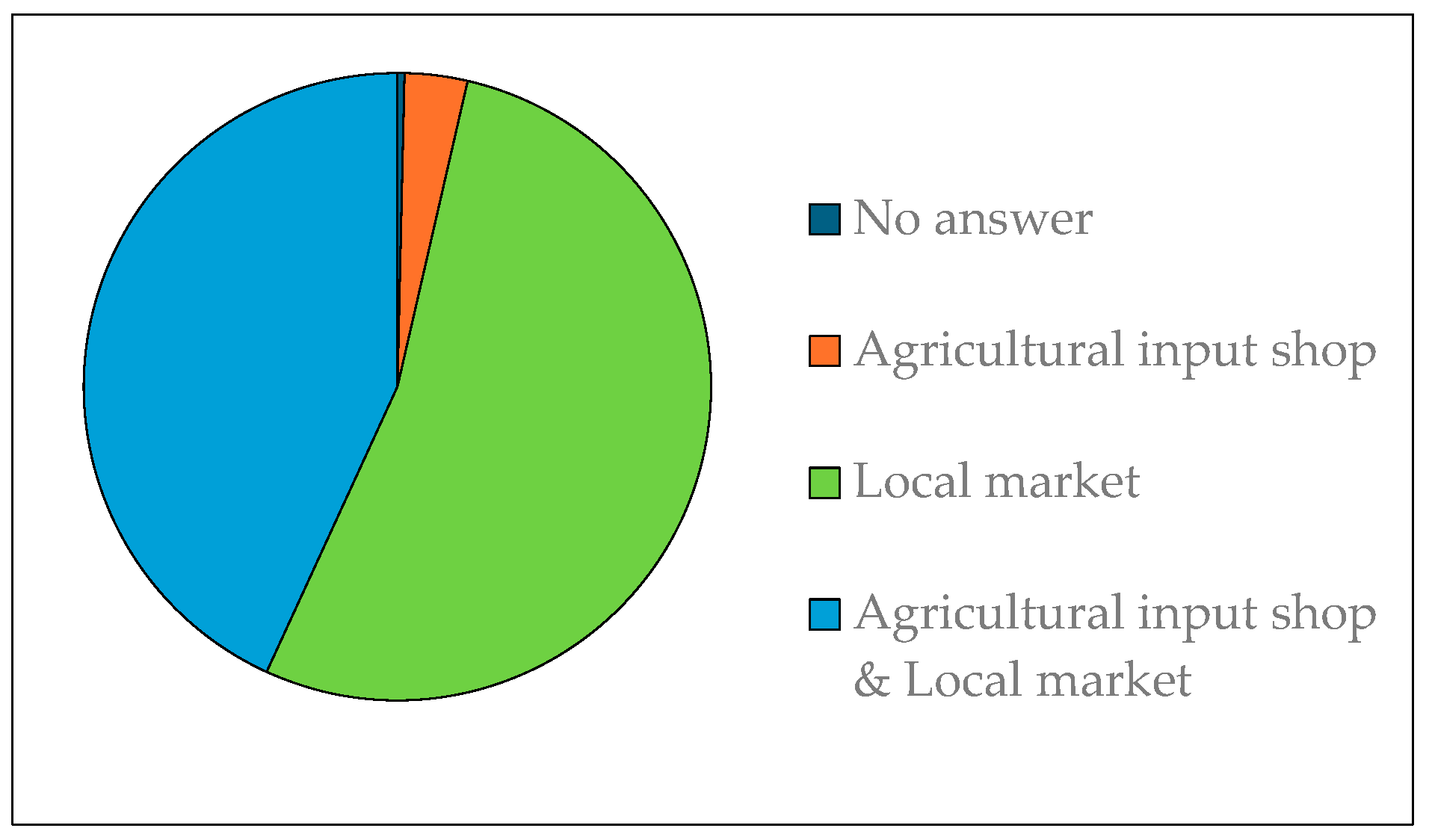

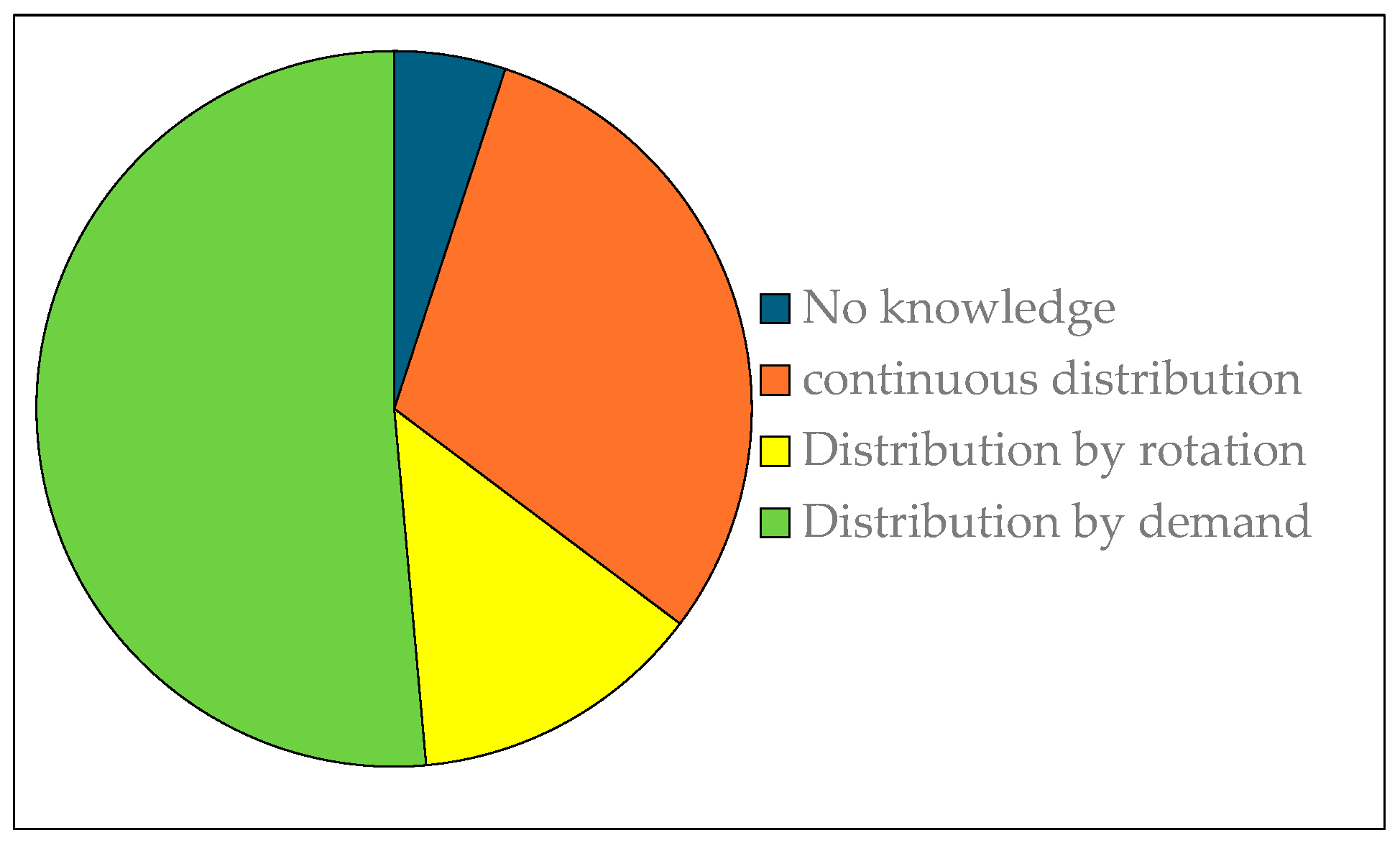

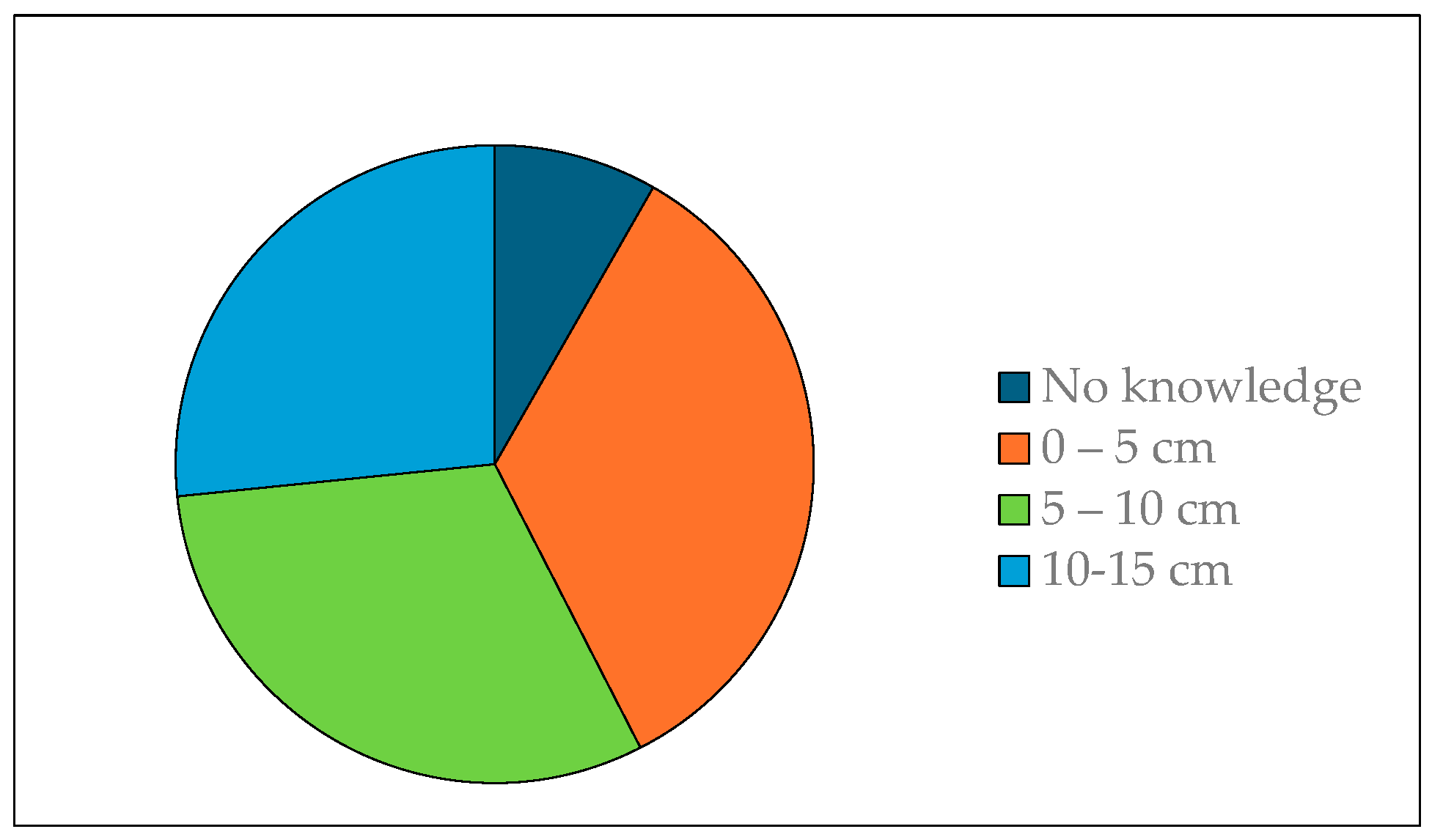

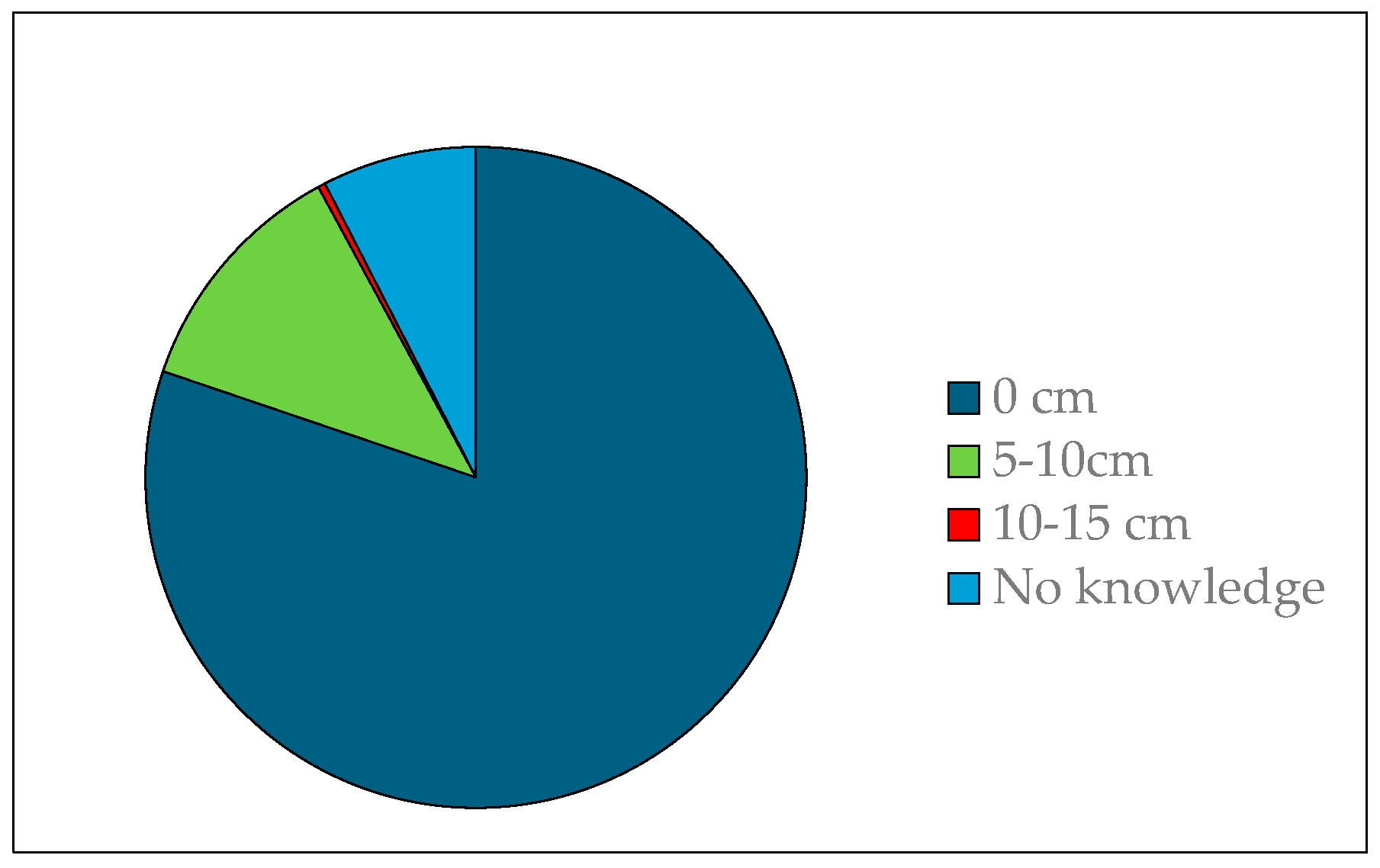

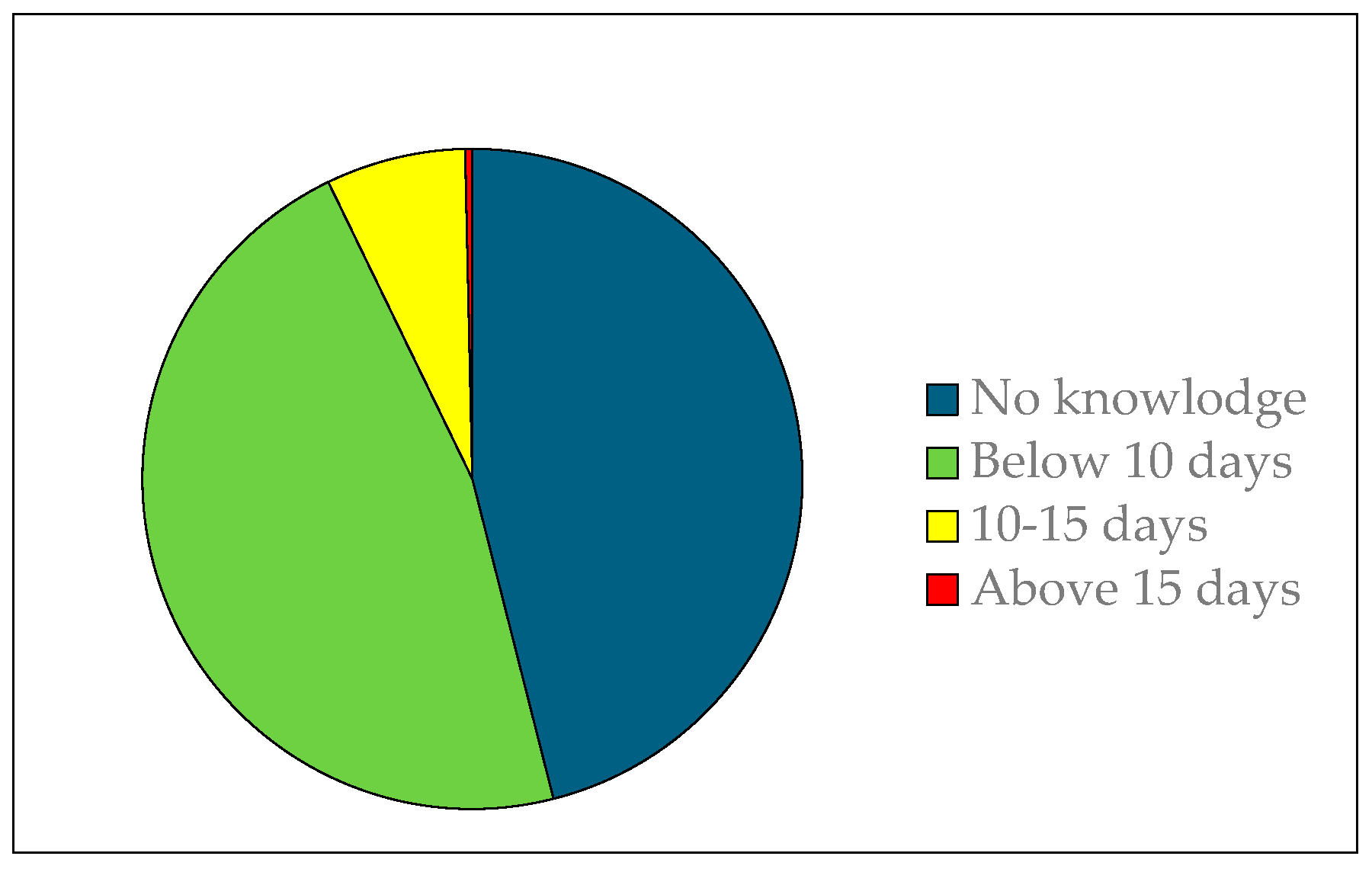

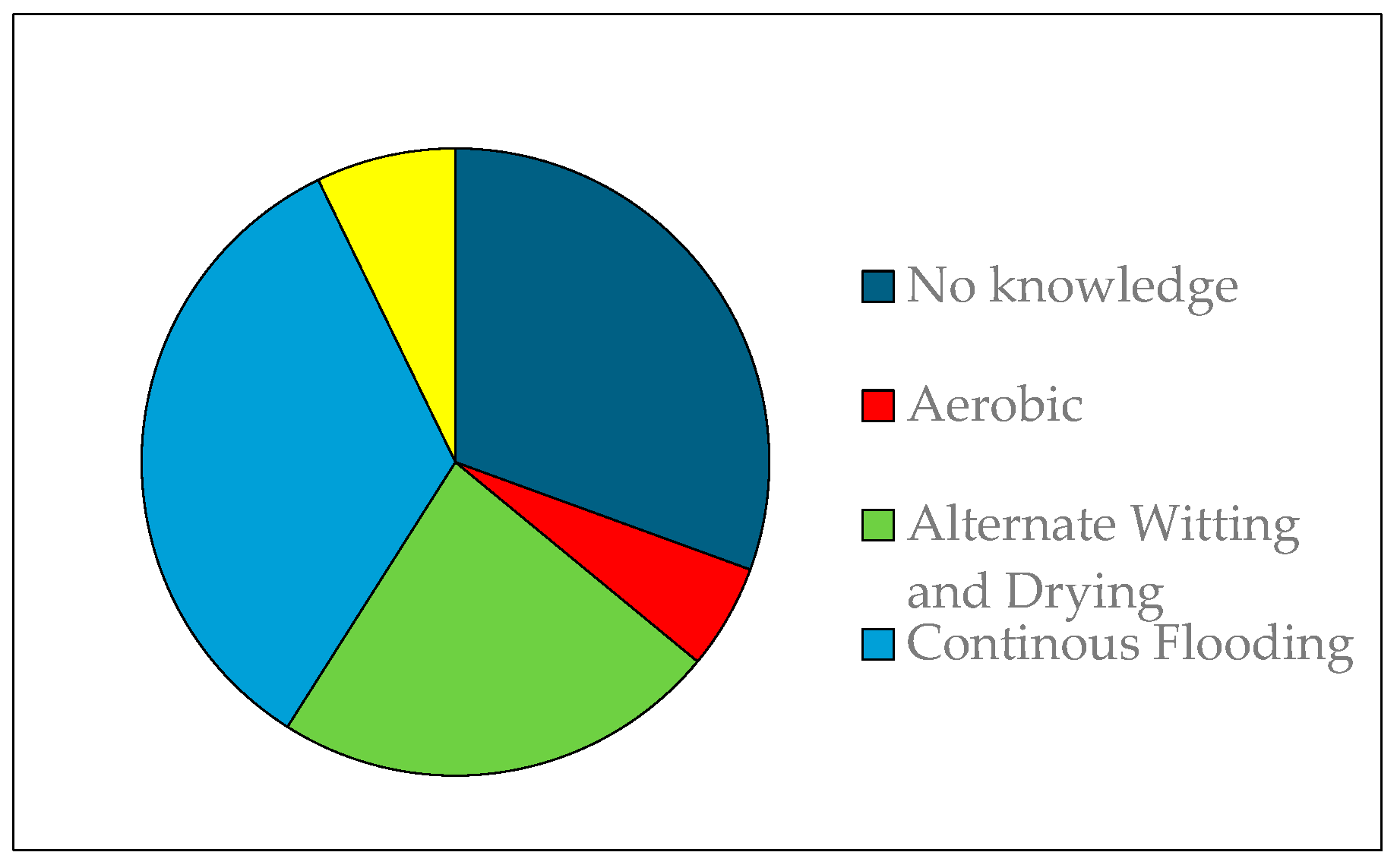

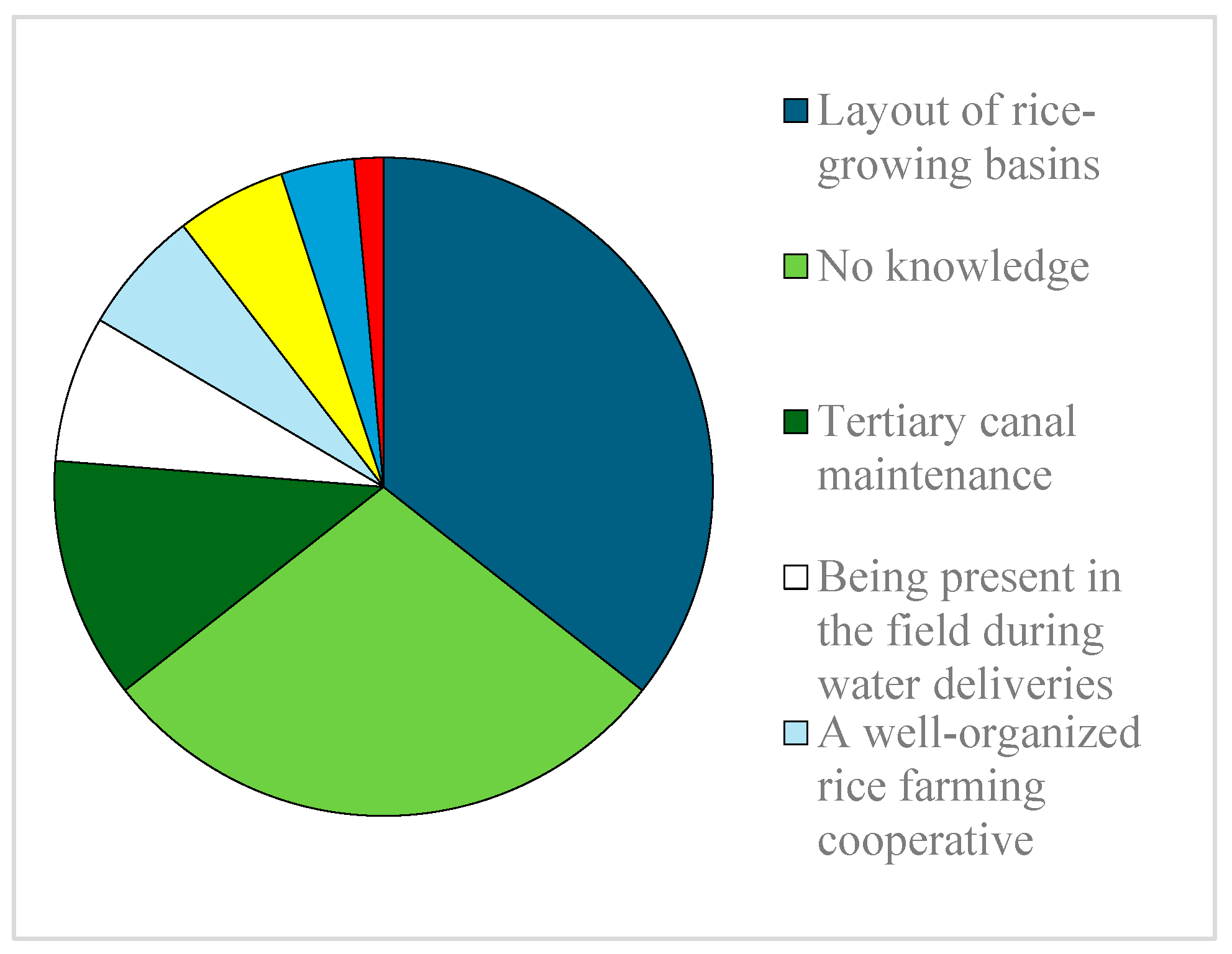

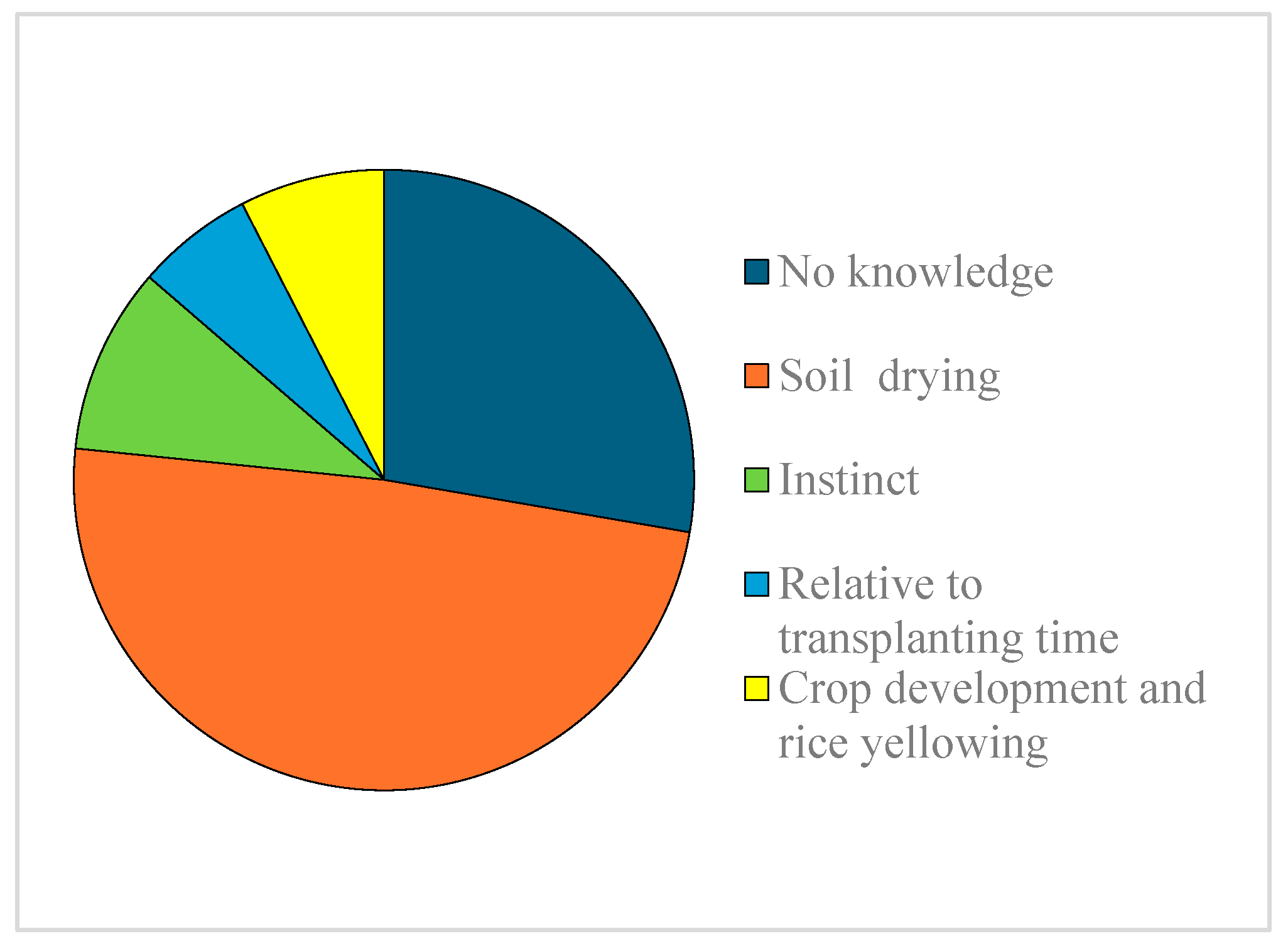

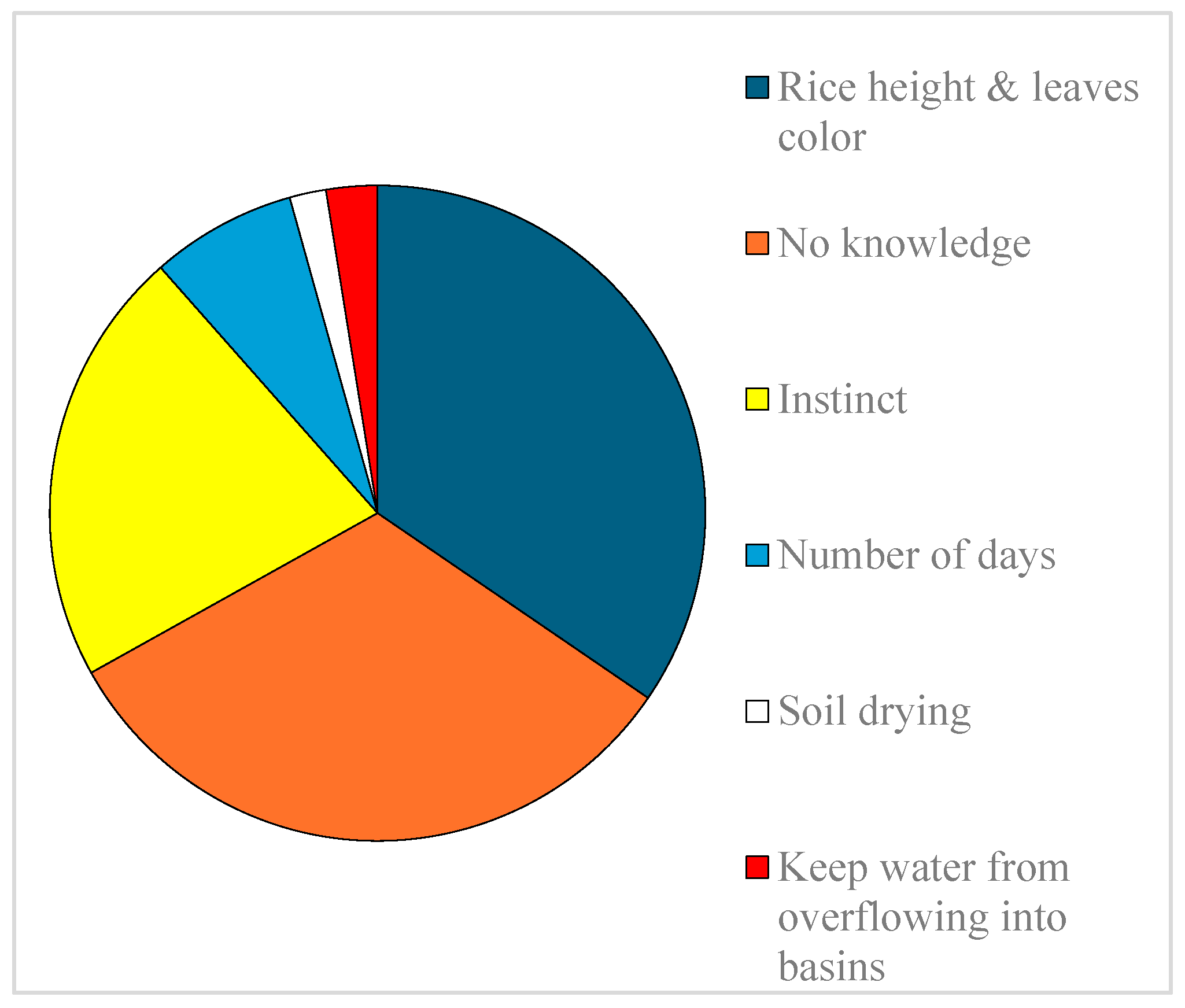

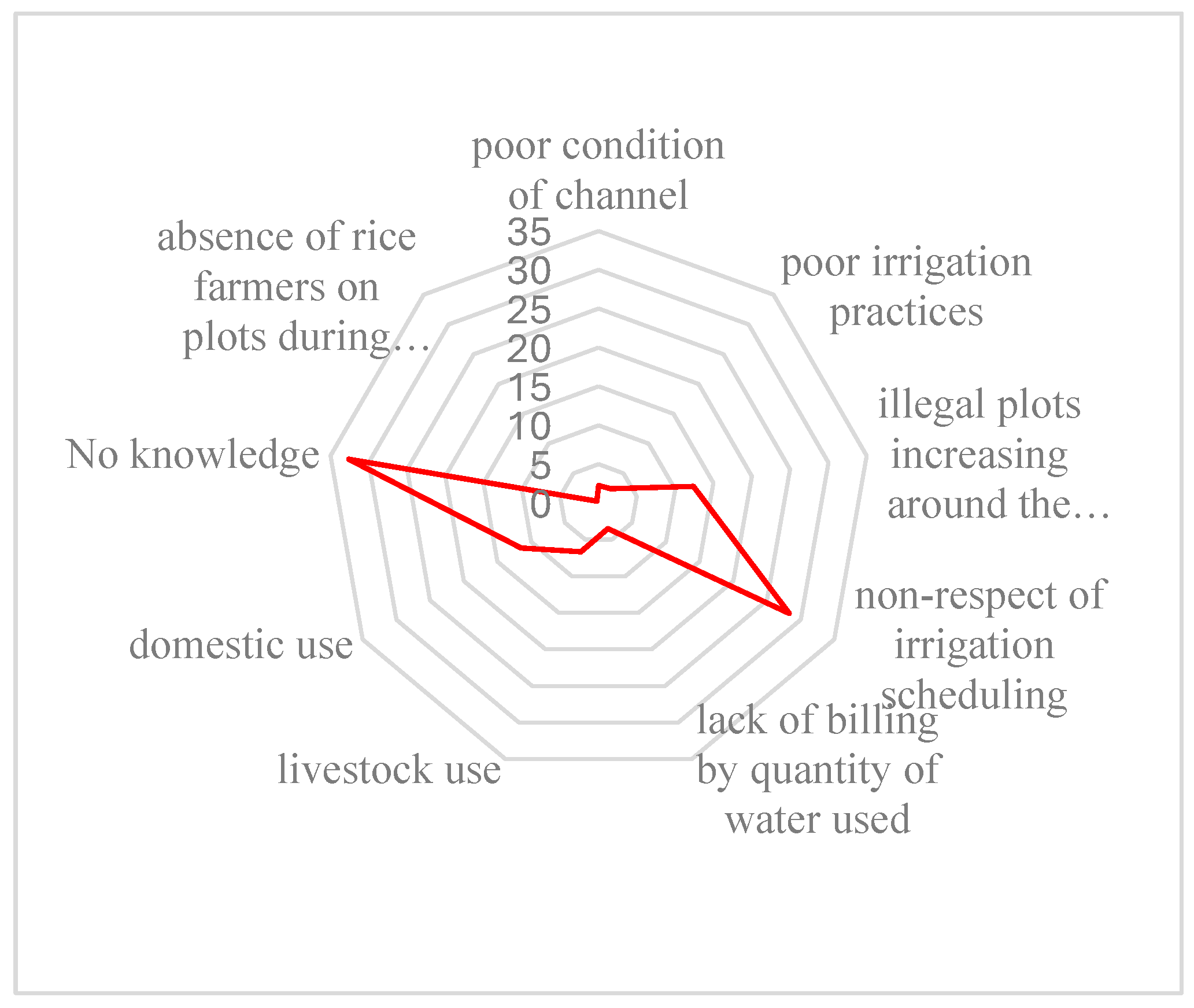

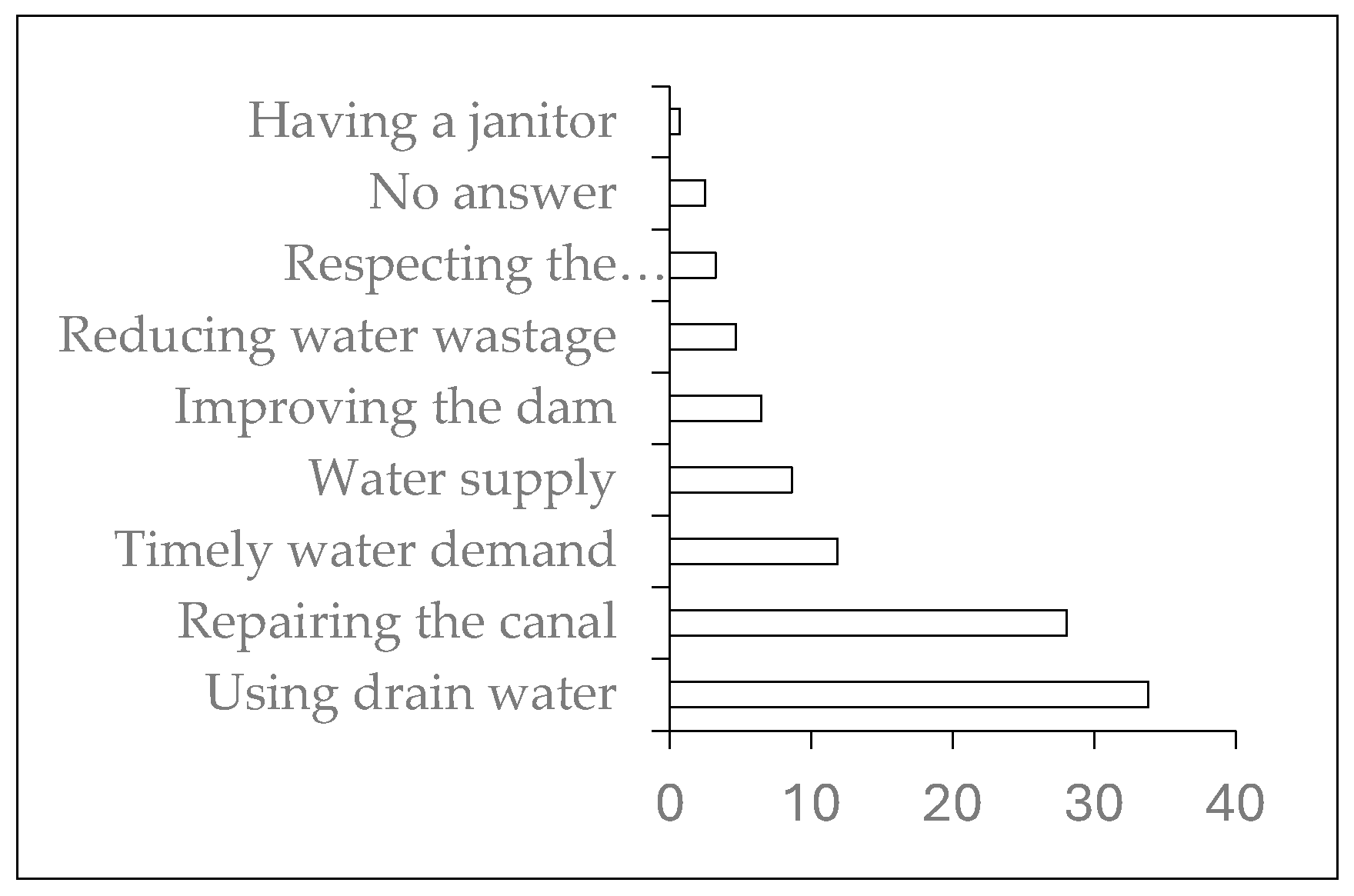

3.3. Irrigation Practices

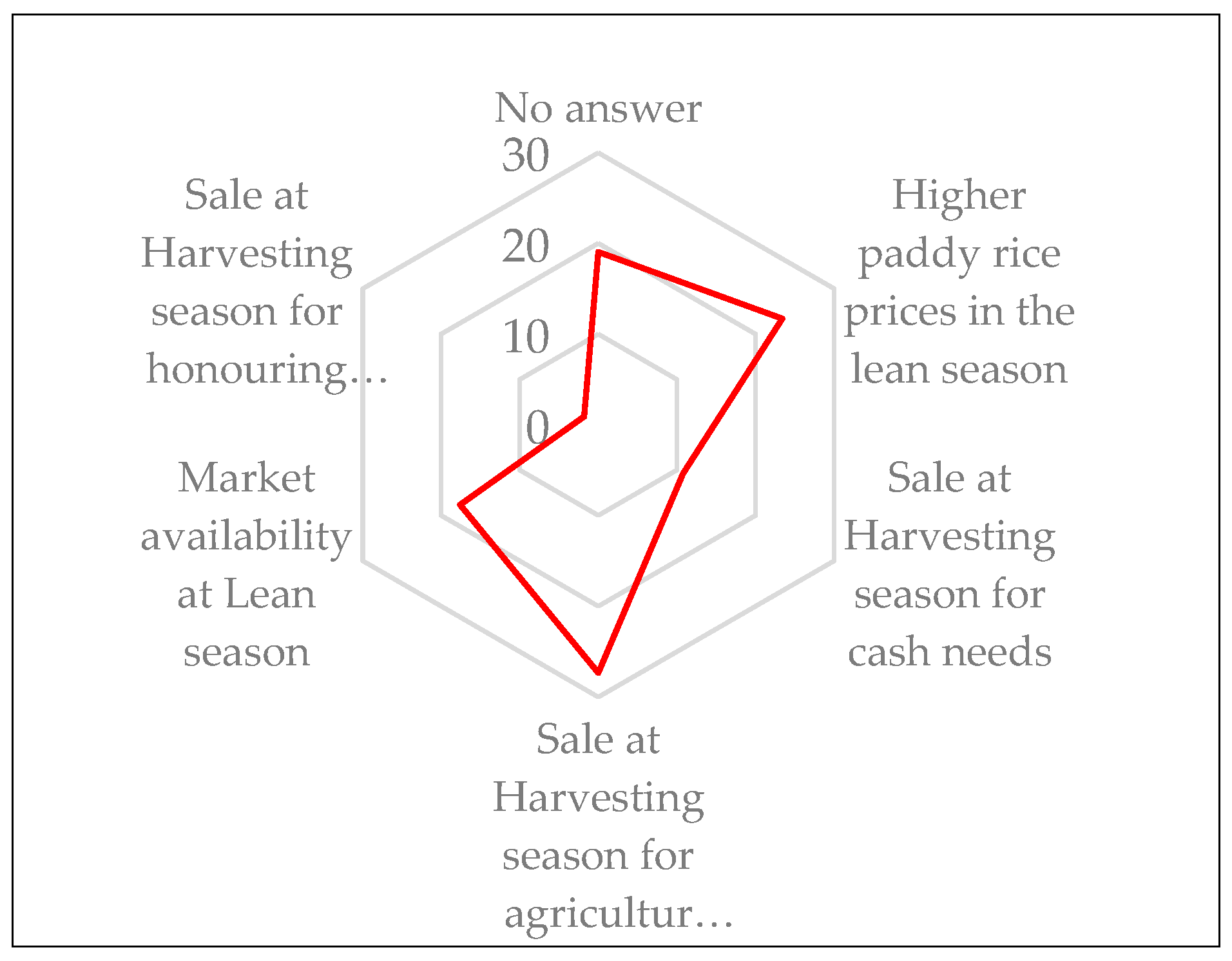

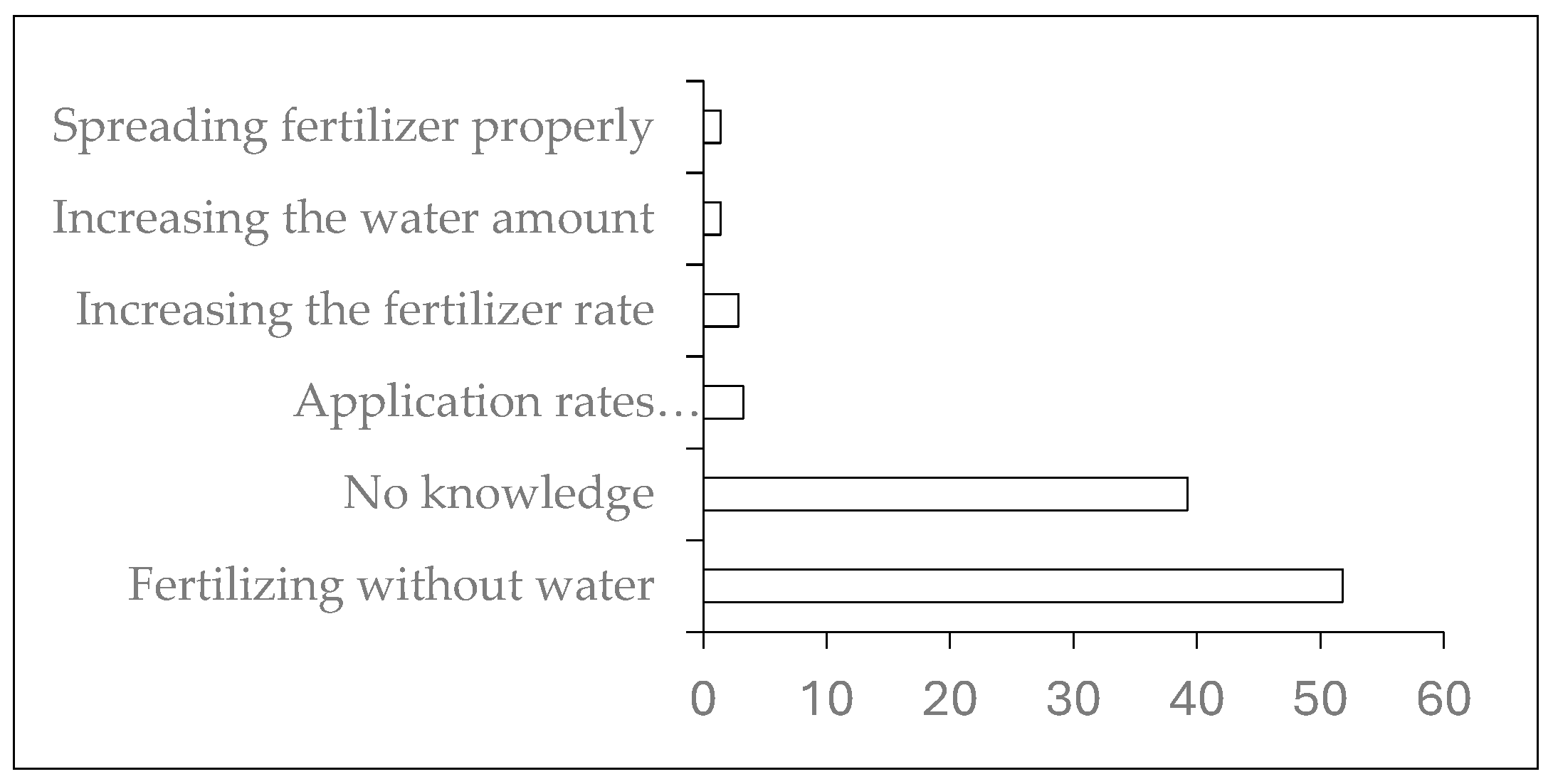

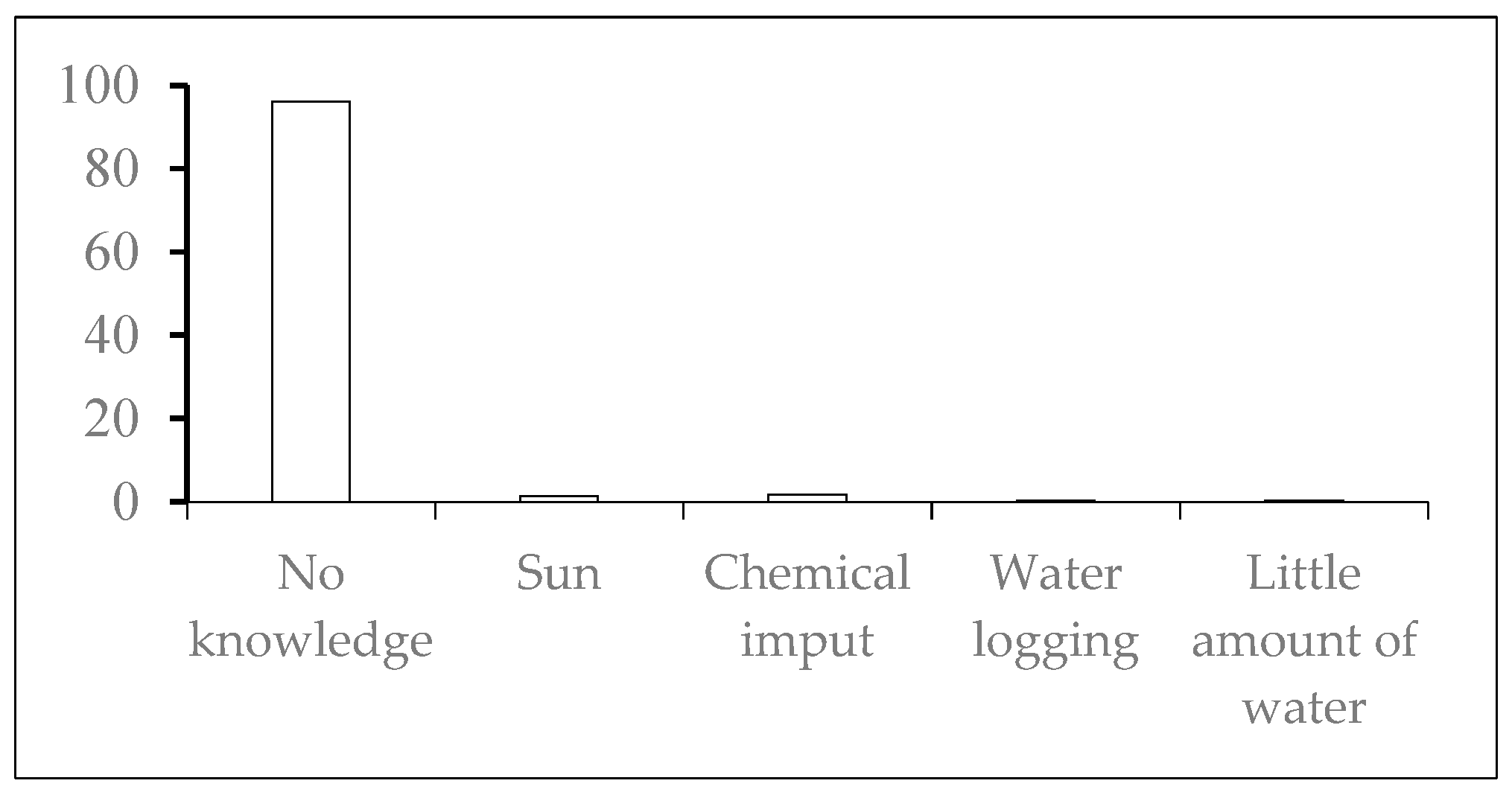

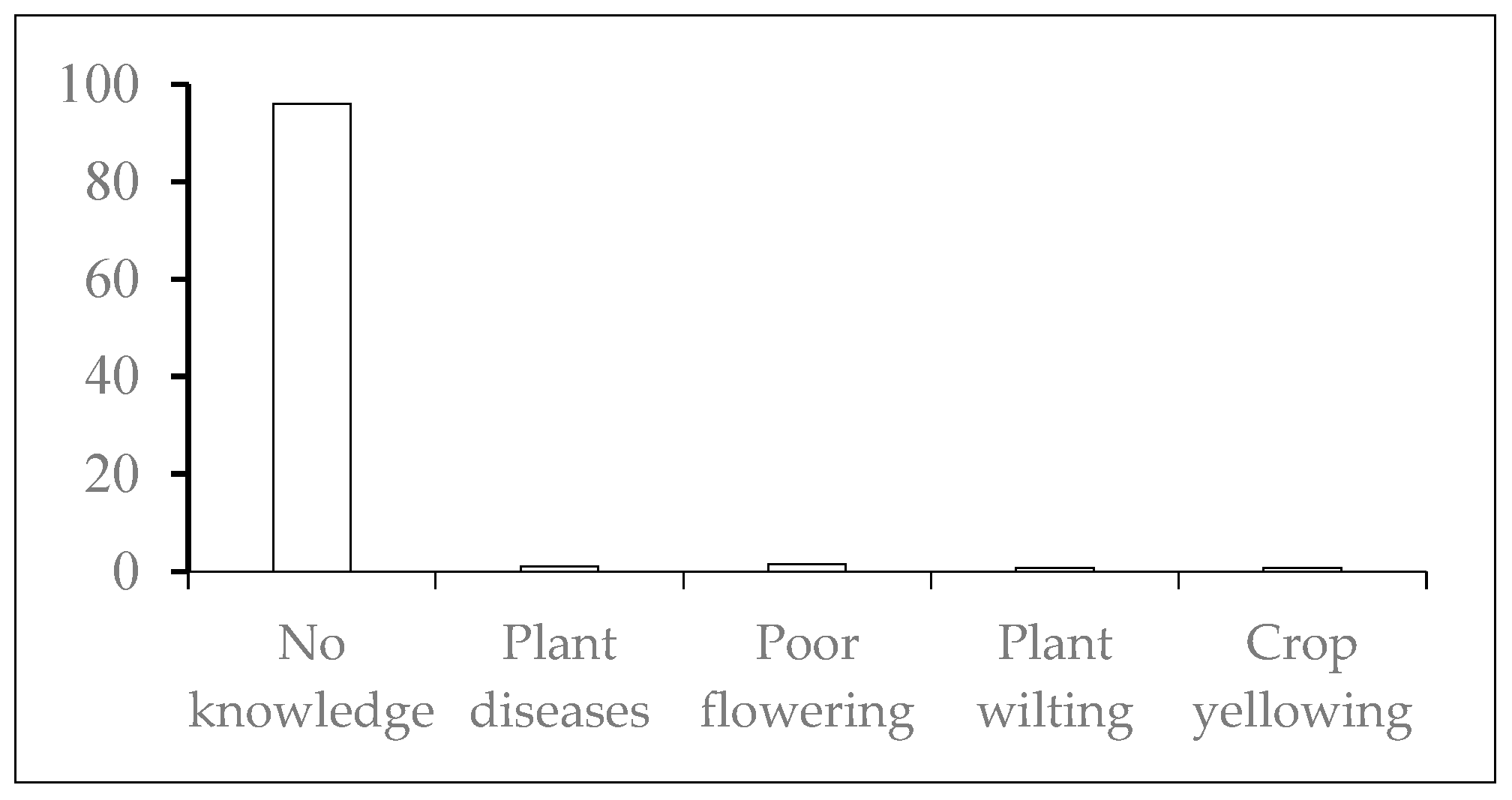

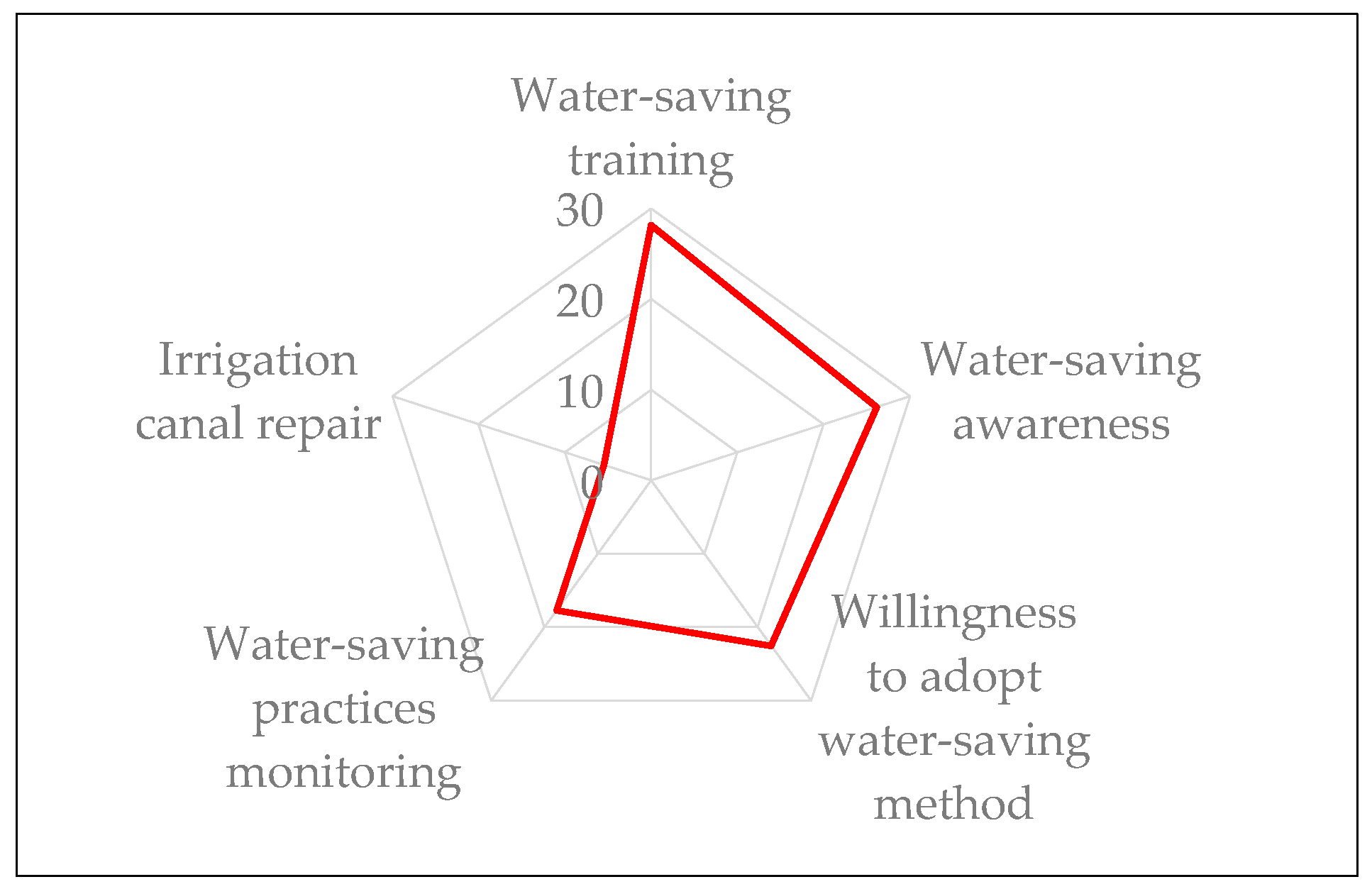

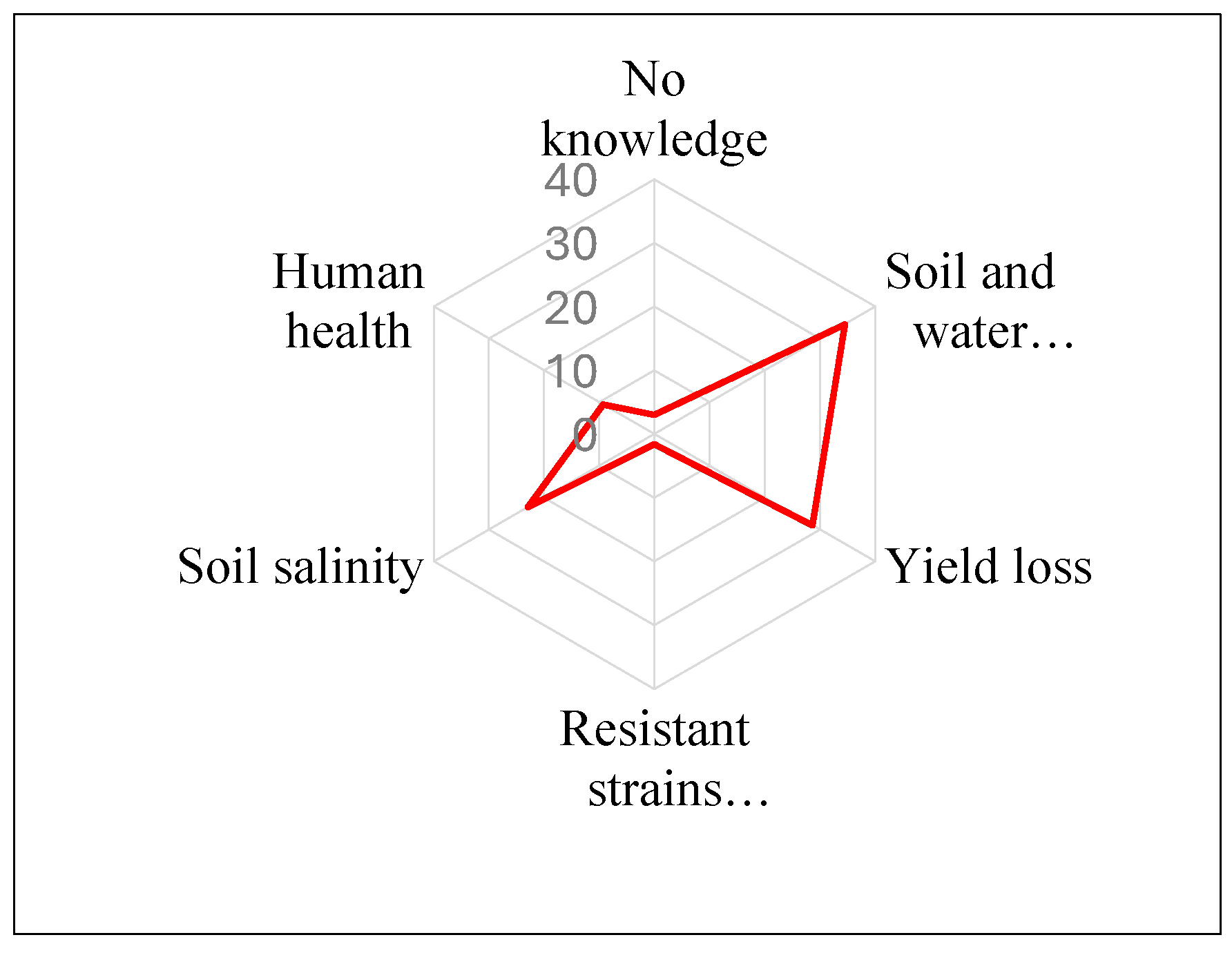

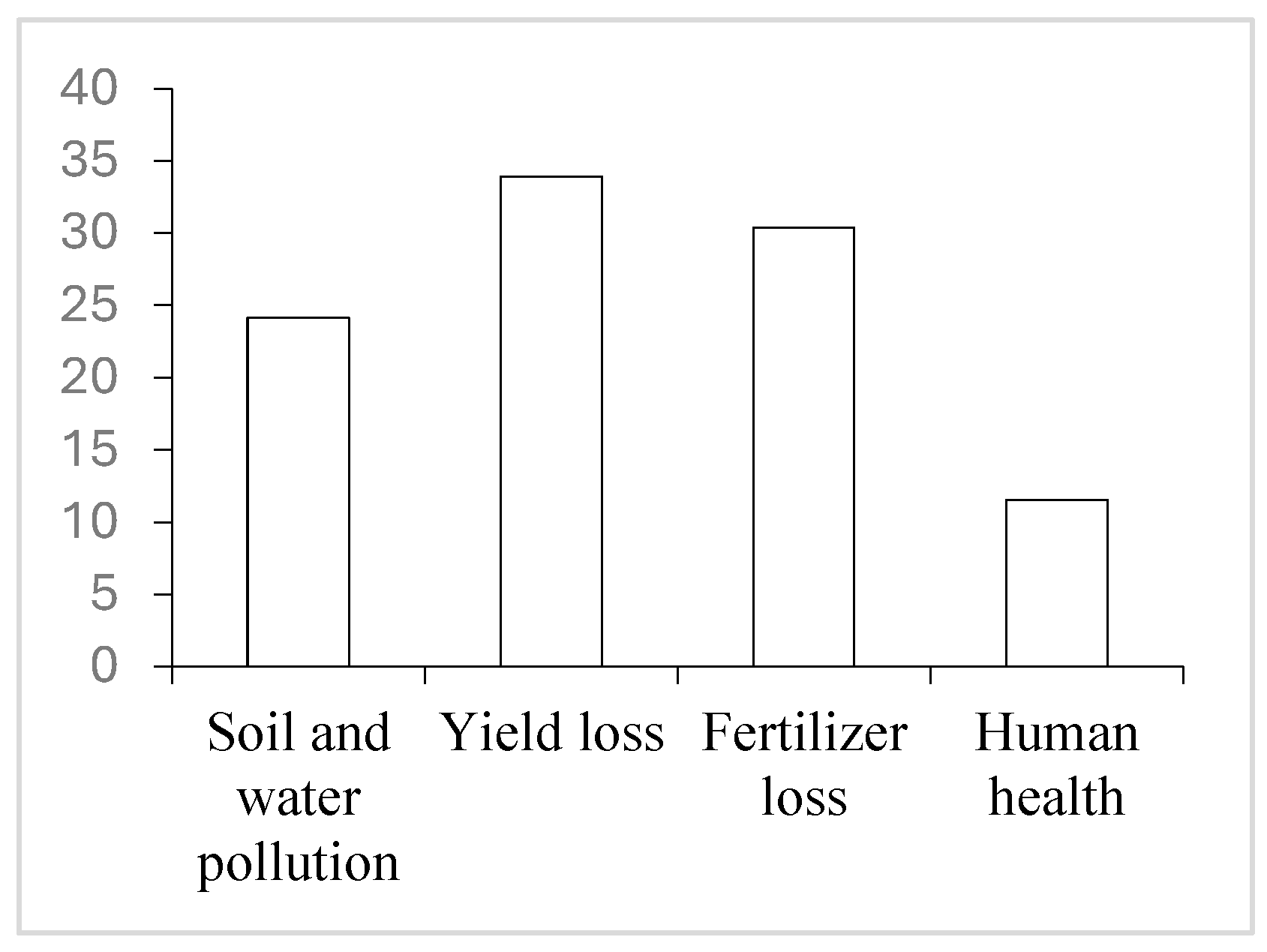

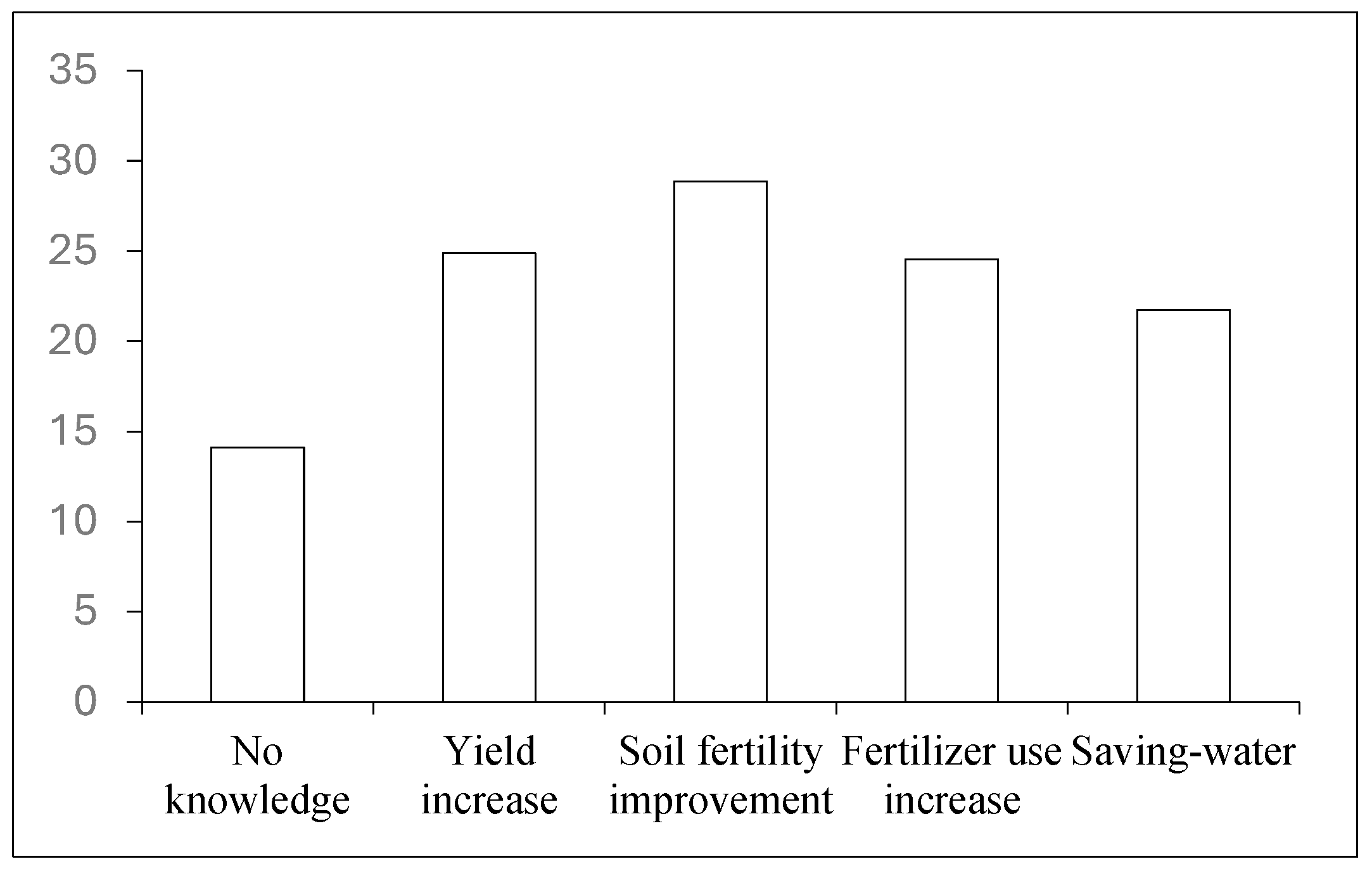

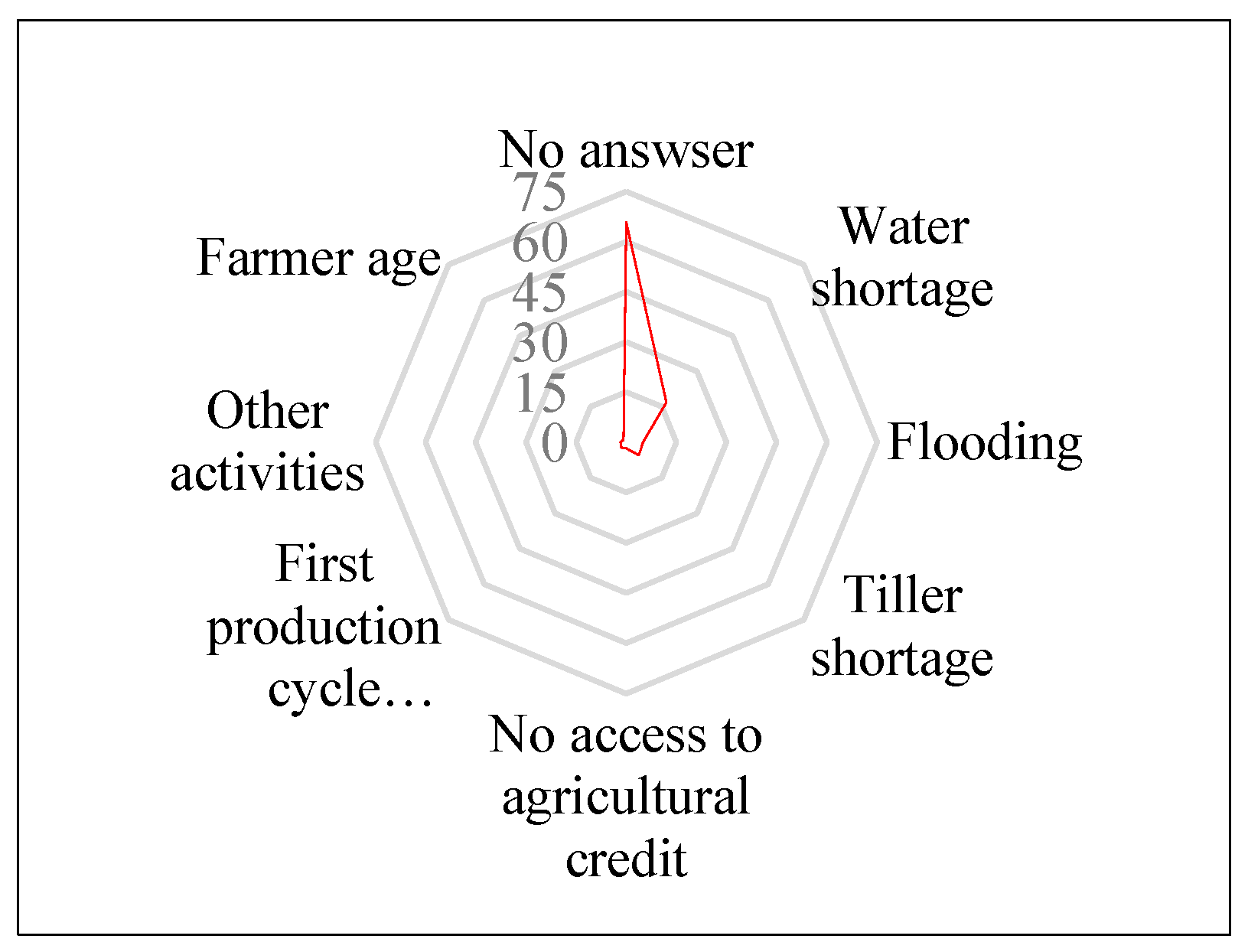

3.4. Famers’ Perception on Water and Agronomic Management

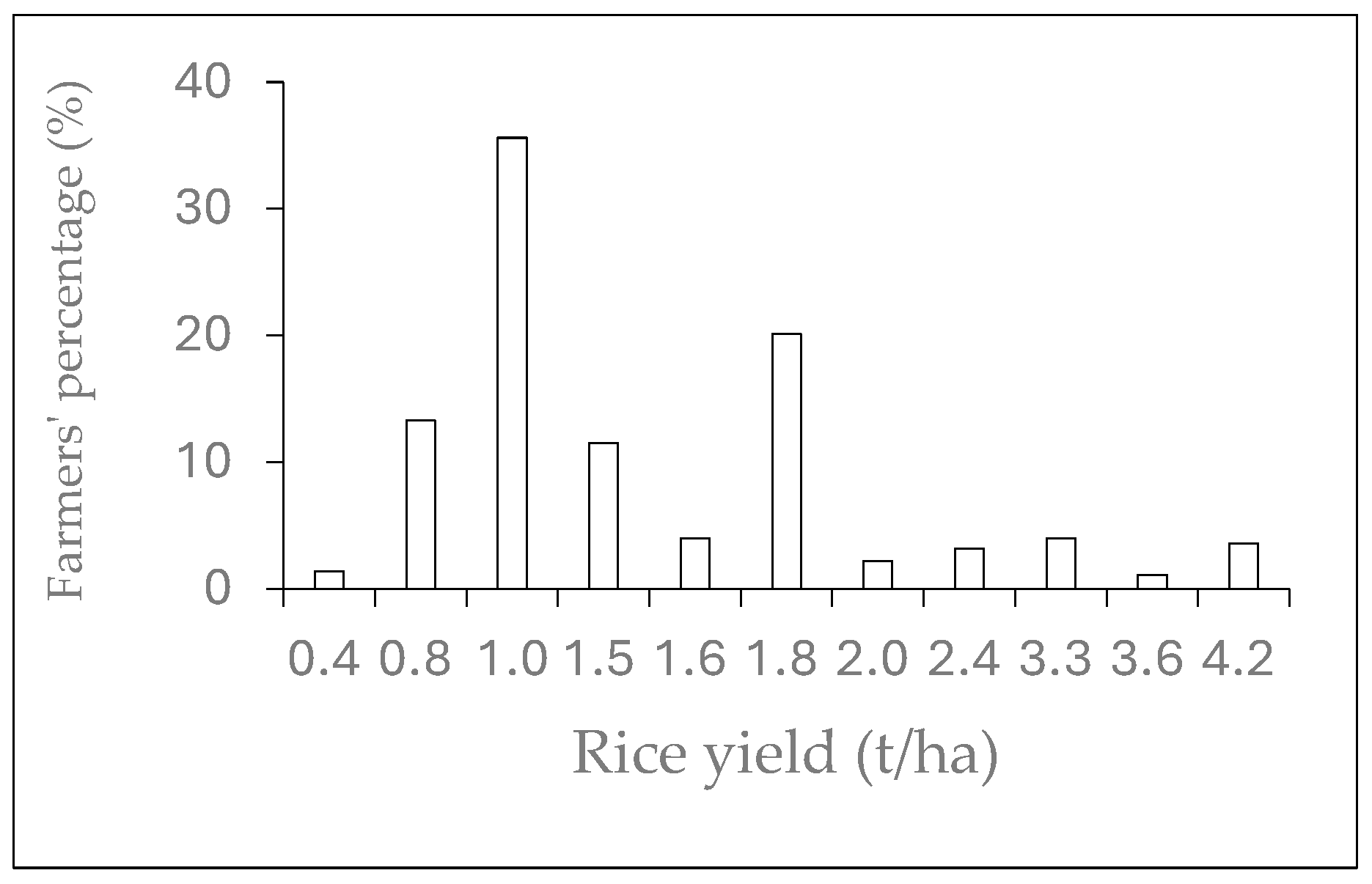

3.5. Impact of Socio-Economic Characteristics, Farming Practices and Irrigation Water Management on Paddy Rice Yields

4. Discussion

4.1. Socio-Demographic Features

4.2. Agronomic and Irrigation Practices

4.3. Grain Yields of Paddy Rice in Irrigated Fields

4.3.1. Socio-Economic Characteristics Impact on Paddy Rice Yields

4.3.2. Farming Practices and Irrigation Management Effects on Paddy Rice Yields

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sarwar, N.; Ahmad, S.; Khan, M.A.; Hasanuzzaman, M. World Rice Production: An Overview. Modern Techniques of Rice Crop Production 2022, 3-12.

- Kumar, A.; Sengar, R.; Pathak, R.K.; Singh, A.K. Integrated approaches to develop drought-tolerant rice: Demand of era for global food security. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 2023, 42, 96-120. [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, A.; Rehman, A.U.; Rehman, A.; Ahmad, S.; Siddique, K.H.; Farooq, M. Increasing sustainability for rice production systems. Journal of Cereal Science 2022, 103, 103400. [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, A.; Seshadri, G.; Ramasamy, S.; Muthurajan, R.; Karuppasamy, K.S. Identification of Newer Stable Genetic Sources for High Grain Number per Panicle and Understanding the Gene Action for Important Panicle Traits in Rice. Plants 2023, 12, 250. [CrossRef]

- Ijachi, C.; Sennuga, S.O.; Bankole, O.-L.; Okpala, E.F.; Preyor, T.J. Assessment of climate variability an d effective coping strategies used by rice farmers in Abuja, Nigeria. International Journal of Agriculture and Food Science 2023, 5, 137-143. [CrossRef]

- Simkhada, K.; Thapa, R. Rice blast, a major threat to the rice production and its various management techniques. Turkish Journal of Agriculture-Food Science and Technology 2022, 10, 147-157. [CrossRef]

- Ladha, J.K.; Radanielson, A.M.; Rutkoski, J.E.; Buresh, R.J.; Dobermann, A.; Angeles, O.; Pabuayon, I.L.B.; Santos-Medellín, C.; Fritsche-Neto, R.; Chivenge, P. Steady agronomic and genetic interventions are essential for sustaining productivity in intensive rice cropping. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e2110807118. [CrossRef]

- Shekhawat, K.; Rathore, S.S.; Chauhan, B.S. Weed management in dry direct-seeded rice: A review on challenges and opportunities for sustainable rice production. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1264. [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Munda, S.; Singh, S.; Kumar, V.; Jangde, H.K.; Mahapatra, A.; Chauhan, B.S. Crop establishment and weed control options for sustaining dry direct seeded rice production in eastern India. Agronomy 2021, 11, 389. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, P.; Asch, F. Rice production and food security in Asian Mega deltas—A review on characteristics, vulnerabilities and agricultural adaptation options to cope with climate change. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science 2020, 206, 491-503. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Chhokar, R.; Meena, R.; Kharub, A.; Gill, S.; Tripathi, S.; Gupta, O.; Mangrauthia, S.; Sundaram, R.; Sawant, C. Challenges and opportunities in productivity and sustainability of rice cultivation system: a critical review in Indian perspective. Cereal Research Communications 2021, 1-29. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Saito, K.; Bado, V.B.; Wopereis, M.C. Thirty years of agronomy research for development in irrigated rice-based cropping systems in the West African Sahel: Achievements and perspectives. Field Crops Research 2021, 266, 108149. [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Cao, W.; Liang, F.; Wen, Y.; Wang, F.; Dong, Z.; Song, H. Water management impact on denitrifier community and denitrification activity in a paddy soil at different growth stages of rice. Agricultural Water Management 2020, 241, 106354. [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Wang, C.; Adalibieke, W.; Jian, Y.; Bo, Y.; Cui, X.; Zhou, F. Declines in nutrient losses from China’s rice paddies jointly driven by fertilizer application and extreme rainfall. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2023, 353, 108537. [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Khanam, M.; Rahman, M.M. Environment-friendly nitrogen management practices in wetland paddy cultivation. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2023, 7, 1020570. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ouyang, W.; Wang, Y.; Lian, Z.; Pan, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.; Niu, S. Paddy water managements for diffuse nitrogen and phosphorus pollution control in China: A comprehensive review and emerging prospects. Agricultural Water Management 2023, 277, 108102. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, Y.; Song, L.; Li, H.; Meng, C.; Wu, J. Linking rice agriculture to nutrient chemical composition, concentration and mass flux in catchment streams in subtropical central China. Agriculture, ecosystems & environment 2014, 184, 9-20. [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Jian, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhao, X.; Ma, Y.; Niu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Xu, C. Nationwide estimates of nitrogen and phosphorus losses via runoff from rice paddies using data-constrained model simulations. Journal of cleaner production 2021, 279, 123642. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Sun, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, X.; Lærke, P.E.; Wu, Q.; Chi, D. Zeolite reduces N leaching and runoff loss while increasing rice yields under alternate wetting and drying irrigation regime. Agricultural Water Management 2023, 277, 108130. [CrossRef]

- Carrijo, D.R.; Lundy, M.E.; Linquist, B.A. Rice yields and water use under alternate wetting and drying irrigation: A meta-analysis. Field Crops Research 2017, 203, 173-180. [CrossRef]

- Djaman, K.; Mel, V.C.; Diop, L.; Sow, A.; El-Namaky, R.; Manneh, B.; Saito, K.; Futakuchi, K.; Irmak, S. Effects of alternate wetting and drying irrigation regime and nitrogen fertilizer on yield and nitrogen use efficiency of irrigated rice in the Sahel. Water 2018, 10, 711. [CrossRef]

- Leon, A.; Kohyama, K. Estimating nitrogen and phosphorus losses from lowland paddy rice fields during cropping seasons and its application for life cycle assessment. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 164, 963-979. [CrossRef]

- Achichi, C.; Sennuga, S.O.; Osho-Lagunju, B.; Alabuja, F. Effect of Farmers' Socioeconomic Characteristics on Access to Agricultural Information in Gwagwalada Area Council, Abuja. Discoveries in Agriculture and Food Sciences 2023, 10, 28-47. [CrossRef]

- Ismael, F.; Mbanze, A.A.; Ndayiragije, A.; Fangueiro, D. Understanding the dynamic of rice farming systems in southern mozambique to improve production and benefits to smallholders. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1018. [CrossRef]

- MERF. Stratégie et Plan d’Action National pour la Biodiversité du Togo (SPANB 2011-2020); Ministère de l'environnement et des ressources forestières: 2014; p. 174.

- Musumba, M.; Grabowski, P.; Palm, C.; Snapp, S. Guide for the Sustainable Intensification Assessment Framework. 2007, 46.

- Chinasho, A.; Bedadi, B.; Lemma, T.; Tana, T.; Hordofa, T.; Elias, B. Farmers’ perceptions about irrigation roles in climate change adaptation and determinants of the choices to WUE-improving practices in southern Ethiopia. Air, Soil and Water Research 2022, 15, 11786221221092454. [CrossRef]

- Assefa, E.; Ayalew, Z.; Mohammed, H. Impact of small-scale irrigation schemes on farmers livelihood, the case of Mekdela Woreda, North-East Ethiopia. Cogent Economics & Finance 2022, 10, 2041259. [CrossRef]

- Kadipo Kaloi, F.; Isaboke, H.N.; Onyari, C.N.; Njeru, L.K. Determinants influencing the adoption of rice intensification system among smallholders in mwea irrigation scheme, Kenya. Advances in Agriculture 2021, 2021, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Sharifzadeh, M.S.; Abdollahzadeh, G. The impact of different education strategies on rice farmers’ knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) about pesticide use. Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences 2021, 20, 312-323. [CrossRef]

- Oo, S.P.; Usami, K. Farmers’ perception of good agricultural practices in rice production in Myanmar: A case study of Myaungmya District, Ayeyarwady Region. Agriculture 2020, 10, 249. [CrossRef]

- Arouna, A.; Gbenou, A.A.; M’boumba, E.B.; Badabake, S.M. Effects of Sowing Methods on Paddy Rice Yields and Milled Rice Quality in Rainfed Lowland Rice in Wet Savannah, Togo. American Journal of Agricultural Science, Engineering, and Technology 2023, 7, 7-15. [CrossRef]

- Ojo, T.O.; Baiyegunhi, L.J.; Adetoro, A.A.; Ogundeji, A.A. Adoption of soil and water conservation technology and its effect on the productivity of smallholder rice farmers in Southwest Nigeria. Heliyon 2021, 7. [CrossRef]

- Faysse, N.; Aguilhon, L.; Phiboon, K.; Purotaganon, M. Mainly farming… but what's next? The future of irrigated farms in Thailand. Journal of Rural Studies 2020, 73, 68-76.

- Rozaki, Z.; Triyono; Indardi; Salassa, D.I.; Nugroho, R.B. Farmers’ responses to organic rice farming in Indonesia: Findings from central Java and south Sulawesi. Open Agriculture 2020, 5, 703-710. [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, H.; Karmiyati, D.; Setyobudi, R.H.; Fauzi, A.; Pakarti, T.A.; Susanti, M.S.; Khan, W.A.; Neimane, L.; Mel, M. Local rice farmers’ attitude and behavior towards agricultural programs and policies. Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Research 2022, 35, 663-677. [CrossRef]

- Haneishi, Y. Rice in Uganda: Production Structure and Contribution to Household Income Generation and Stability. Graduate School of Horticulture, Chiba University 2014.

- Zhou, Q.; Deng, X.; Wu, F.; Li, Z.; Song, W. Participatory irrigation management and irrigation water use efficiency in maize production: evidence from Zhangye City, Northwestern China. Water 2017, 9, 822. [CrossRef]

- Angella, N.; Dick, S.; Fred, B. Willingness to pay for irrigation water and its determinants among rice farmers at Doho Rice Irrigation Scheme (DRIS) in Uganda. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics 2014, 6, 345-355.

- Moon, N.N.; Hossain, M.E.; Khan, M.A.; Rahman, M.A.; Saha, S.M. Land tenure system and its effect on productivity, profitability and efficiency of boro rice production in northern part of Bangladesh. Turkish Journal of Agriculture-Food Science and Technology 2020, 8, 2433-2440. [CrossRef]

- Djanggola, A.R.; Basir, M.; Anam, H.; Ichwan, M. Rainfed and Irrigated Rice Farmers Profiles: A Case Study from Banggai, Indonesia. Age 2021, 25, 2.

- Koirala, K.H.; Mishra, A.; Mohanty, S. Impact of land ownership on productivity and efficiency of rice farmers: The case of the Philippines. Land use policy 2016, 50, 371-378. [CrossRef]

- Rodenburg, J.; Johnson, J.-M.; Dieng, I.; Senthilkumar, K.; Vandamme, E.; Akakpo, C.; Allarangaye, M.D.; Baggie, I.; Bakare, S.O.; Bam, R.K. Status quo of chemical weed control in rice in sub-Saharan Africa. Food Security 2019, 11, 69-92. [CrossRef]

- Obiri, B.; Obeng, E.; Oduro, K.; Apetorgbor, M.; Peprah, T.; Duah-Gyamfi, A.; Mensah, J. Farmers’ perceptions of herbicide usage in forest landscape restoration programs in Ghana. Scientific African 2021, 11, e00672. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, M.A.; Collavo, A.; Ovejero, R.; Shivrain, V.; Walsh, M.J. The challenge of herbicide resistance around the world: a current summary. Pest management science 2018, 74, 2246-2259. [CrossRef]

- Bouwman, T.; Andersson, J.; Giller, K. Herbicide induced hunger? Conservation Agriculture, ganyu labour and rural poverty in Central Malawi. The Journal of Development Studies 2021, 57, 244-263. [CrossRef]

- Ofosu, R.; Agyemang, E.D.; Márton, A.; Pásztor, G.; Taller, J.; Kazinczi, G. Herbicide resistance: managing weeds in a changing world. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1595. [CrossRef]

- Tyohemba, R.L.; Pillay, L.; Humphries, M.S. Bioaccumulation of current-use herbicides in fish from a global biodiversity hotspot: Lake St Lucia, South Africa. Chemosphere 2021, 284, 131407. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ruiz-Menjivar, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Swisher, M.E. Technical training and rice farmers’ adoption of low-carbon management practices: The case of soil testing and formulated fertilization technologies in Hubei, China. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 226, 454-462. [CrossRef]

- Wossen, T.; Abdoulaye, T.; Alene, A.; Haile, M.G.; Feleke, S.; Olanrewaju, A.; Manyong, V. Impacts of extension access and cooperative membership on technology adoption and household welfare. Journal of rural studies 2017, 54, 223-233. [CrossRef]

- Massey, J.H.; Walker, T.W.; Anders, M.M.; Smith, M.C.; Avila, L.A. Farmer adaptation of intermittent flooding using multiple-inlet rice irrigation in Mississippi. Agricultural Water Management 2014, 146, 297-304. [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, D.; Owusu-Sekyere, E.; Owusu, V.; Jordaan, H. Impact of agricultural extension service on adoption of chemical fertilizer: Implications for rice productivity and development in Ghana. NJAS: wageningen journal of life sciences 2016, 79, 41-49. [CrossRef]

- Nonvide, G.M.A. A re-examination of the impact of irrigation on rice production in Benin: An application of the endogenous switching model. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences 2019, 40, 657-662. [CrossRef]

- Maligalig, R.; Demont, M.; Umberger, W.J.; Peralta, A. Off-farm employment increases women's empowerment: Evidence from rice farms in the Philippines. Journal of Rural Studies 2019, 71, 62-72. [CrossRef]

- Onyenekwe, S.; Okorji, E. Effects of off-farm work on the technical efficiency of rice farmers in Enugu state, Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural Economics and Development 2015, 4, 044-050.

- Nehring, R. The Impacts of Off-Farm Income on Farm Efficiency, Scale, and Profitability Rice Farms. 2015.

- Ahmed, M.H.; Melesse, K.A. Impact of off-farm activities on technical efficiency: evidence from maize producers of eastern Ethiopia. Agricultural and Food Economics 2018, 6, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Anang, B.T. Effect of non-farm work on agricultural productivity: Empirical evidence from northern Ghana; 9292562622; WIDER working paper: 2017. [CrossRef]

- Anang, B.T.; Nkrumah-Ennin, K.; Nyaaba, J.A. Does off-farm work improve farm income? Empirical evidence from Tolon district in northern Ghana. Advances in Agriculture 2020, 2020, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Njeru, T.N.; Mano, Y.; Otsuka, K. Role of access to credit in rice production in sub-Saharan Africa: The case of Mwea irrigation scheme in Kenya. Journal of African Economies 2016, 25, 300-321. [CrossRef]

- Nonvide, G.M.A. Effect of adoption of irrigation on rice yield in the municipality of Malanville, Benin. African Development Review 2017, 29, 109-120. [CrossRef]

- Jimi, N.A.; Nikolov, P.V.; Malek, M.A.; Kumbhakar, S. The effects of access to credit on productivity: separating technological changes from changes in technical efficiency. Journal of Productivity Analysis 2019, 52, 37-55. [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Magezi, E.F. The impact of microcredit on agricultural technology adoption and productivity: Evidence from randomized control trial in Tanzania. World Development 2020, 133, 104997. [CrossRef]

- Agbodji, A.E.; Johnson, A.A. Agricultural credit and its impact on the productivity of certain cereals in Togo. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 2021, 57, 3320-3336. [CrossRef]

- Anang, B.T.; Bäckman, S.; Sipiläinen, T. Agricultural microcredit and technical efficiency: The case of smallholder rice farmers in Northern Ghana. Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Tropics and Subtropics (JARTS) 2016, 117, 189-202.

- Adedoyin, A.O.; Shamsudin, M.N.; Radam, A.; AbdLatif, I. Effect of improved high yielding rice variety on farmers productivity in Mada, Malaysia. Int J Agric Sic Vet Med 2016, 4, 39-52.

- Huang, M.; Zhou, X.; Cao, F.; Xia, B.; Zou, Y. No-tillage effect on rice yield in China: A meta-analysis. Field Crops Research 2015, 183, 126-137. [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Zhang, H.; He, M.; Yuan, J.; Xu, L.; Tian, G. No-tillage effects on grain yield, N use efficiency, and nutrient runoff losses in paddy fields. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2016, 23, 21451-21459. [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.K.; Islam, M.M.; Salahin, N.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Effect of tillage practices on soil properties and crop productivity in wheat-mungbean-rice cropping system under subtropical climatic conditions. The scientific world journal 2014, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Cheboi, P.K.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Onyando, J.; Kiptum, C.K.; Heinz, V. Effect of ploughing techniques on water use and yield of rice in maugo small-holder irrigation scheme, Kenya. AgriEngineering 2021, 3. [CrossRef]

- Zingore, S.; Wairegi, L.; Ndiaye, M.K. Guide pour la gestion des systèmes de culture de riz. Consortium Africain pour la Santé des Sols, Nairobi 2014.

- Cheboi, P.K. Water retention and yield of rice crop under different land preparation techniques in Maugo smallholder irrigation scheme, Homa Bay county, Kenya. University of Eldoret, 2021.

- Kalita, J.; Ahmed, P.; Baruah, N. Puddling and its effect on soil physical properties and growth of rice and post rice crops: A review. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2020, 9, 503-510.

- Wang, J.; Chen, K.Z.; Das Gupta, S.; Huang, Z. Is small still beautiful? A comparative study of rice farm size and productivity in China and India. China Agricultural Economic Review 2015, 7, 484-509. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Xiong, D.; Wang, F. Comparing the grain yields of direct-seeded and transplanted rice: A meta-analysis. Agronomy 2019, 9, 767. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Singh, A. Direct seeded rice: Prospects, problems/constraints and researchable issues in India. Current agriculture research Journal 2017, 5, 13. [CrossRef]

- Walia, U.; Walia, S.; Sidhu, A.; Nayyar, S. Productivity of direct seeded rice in relation to different dates of sowing and varieties in Central Punjab. Journal of Crop and Weed 2014, 10, 126-129.

- Liu, H.; Hussain, S.; Zheng, M.; Peng, S.; Huang, J.; Cui, K.; Nie, L. Dry direct-seeded rice as an alternative to transplanted-flooded rice in Central China. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2015, 35, 285-294. [CrossRef]

- Bahua, M.I.; Gubali, H. Direct seed planting system and giving liquid organic fertilizer as a new method to increase rice yield and growth (Oryza sativa L.). AGRIVITA Journal of Agricultural Science 2020, 42, 68-77. [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Chen, Q.; Peng, S.; Wang, W.; Nie, L. Lower global warming potential and higher yield of wet direct-seeded rice in Central China. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2016, 36, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Alipour Abookheili, F.; Mobasser, H.R. Effect of planting density on growth characteristics and grain yield increase in successive cultivations of two rice cultivars. Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment 2021, 4, e20213. [CrossRef]

- Abduh, A.M.; Hanudin, E.; Purwanto, B.H.; Utami, S.N.H. Effect of Plant Spacing and Organic Fertilizer Doses on Methane Emission in Organic Rice Fields. Environment & Natural Resources Journal 2020, 18. [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, P.; SENTHIVEL, T.; NANDHAKUMAR, M. Influence of plant spacing and weed management practices on the growth and yield of paddy (oryza sativa l.). Journal of advanced studies in agricultural, biological and environmental sciences 2020, 7.

- Chadhar, A.R.; Nadeem, M.A.; Ali, H.H.; Safdar, M.E.; Raza, A.; Adnan, M.; Hussain, M.; Ali, L.; Kashif, M.S.; Javaid, M.M. Quantifying the impact of plant spacing and critical weed competition period on fine rice production under the system of rice intensification. 2020.

- Afifah, A.; Jahan, M.S.; Khairi, M.; Nozulaidi, M. Effect of various water regimes on rice production in lowland irrigation. Australian Journal of Crop Science 2015, 9, 153-159.

- Sosiawan, H.; Annisa, W. Yield Response and Water Productivity for Rice Growth With Several Irrigations Treatment in West Java. Sriwijaya Journal of Environment 2019, 4, 109-116. [CrossRef]

- Chandra, M.S.; Kumar, K.A.; Madhavi, M.; Chary, D.S. Effect of alternate wetting and drying (AWD) irrigation method on yield and economic potential of different rice (Oryza sativa L.) varieties in puddled soil. IJCS 2019, 7, 968-973.

- Mote, K.; Praveen Rao, V.; Ramulu, V.; Avil Kumar, K.; Uma Devi, M. Standardization of alternate wetting and drying (AWD) method of water management in lowland rice (Oryza sativa L.) for upscaling in command outlets. Irrigation and drainage 2018, 67, 166-178. [CrossRef]

- Ishfaq, M.; Farooq, M.; Zulfiqar, U.; Hussain, S.; Akbar, N.; Nawaz, A.; Anjum, S.A. Alternate wetting and drying: A water-saving and ecofriendly rice production system. Agricultural Water Management 2020, 241, 106363. [CrossRef]

- Sriphirom, P.; Chidthaisong, A.; Towprayoon, S. Effect of alternate wetting and drying water management on rice cultivation with low emissions and low water used during wet and dry season. Journal of cleaner production 2019, 223, 980-988. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.A.; Rajitha, G. Alternate wetting and drying (AWD) irrigation-a smart water saving technology for rice: a review. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences 2019, 8, 2561-2571. [CrossRef]

| Region | Rice irrigation schemes | Sample of rice farmers |

|---|---|---|

| Coastal region | Kovie | 76 |

| Agome- Glouzou | 92 | |

| Forest region | Kpele Beme | 44 |

| Kpele Tutu | 36 | |

| Savannah region | Koumbeloti | 30 |

| Total | 278 |

| Profile of producers | Women | Men | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 90 | 188 | 278 | |

| Age | No knowledge | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| 18 – 27 years | 4 | 15 | 19 | |

| 28 – 37 years | 11 | 46 | 57 | |

| 38-47 years | 33 | 55 | 88 | |

| 48 – 57 years | 27 | 47 | 74 | |

| 58 – 67 years | 14 | 20 | 34 | |

| above 68 years | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Marital status | No answer | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Divorced | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Married | 70 | 169 | 239 | |

| Single | 4 | 12 | 16 | |

| Widower/widow | 15 | 6 | 21 | |

| Educations background | None | 32 | 22 | 54 |

| Primary | 39 | 65 | 104 | |

| JHS | 14 | 70 | 84 | |

| SHS | 3 | 23 | 26 | |

| University | 2 | 8 | 10 | |

| Experience | Below 5 years | 35 | 76 | 111 |

| 6 – 10 years | 16 | 48 | 64 | |

| 11 – 15 years | 21 | 27 | 48 | |

| above 15 years | 18 | 37 | 56 | |

| Type of tenancy | No answer | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Clan-based | 12 | 20 | 32 | |

| Own | 5 | 22 | 27 | |

| Public | 25 | 64 | 89 | |

| Rented | 48 | 81 | 129 | |

| Member’s of farmers cooperative | No answer | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| No member | 10 | 33 | 43 | |

| Member | 80 | 149 | 229 | |

| Source income | Agriculture | 56 | 116 | 172 |

| Agriculture & Trade | 25 | 15 | 40 | |

| Agriculture & Handicrafts | 3 | 33 | 35 | |

| Agriculture & Livestock | 6 | 24 | 30 | |

| Agricultural credit access | Agricultural credit access | 40 | 60 | 100 |

| No Agricultural credit access | 50 | 128 | 178 | |

| Application period of N15P15K15 fertilizer | Amount applied (kg/ha) | Percentage of farmers (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Basal | 0 | 96,4 |

| 150 | 1,8 | |

| 200 | 1,1 | |

| 250 | 0,4 | |

| Two weeks after planting | 0 | 38,8 |

| 50 | 1,4 | |

| 100 | 6,5 | |

| 150 | 11,2 | |

| 200 | 24,1 | |

| 250 | 0,4 | |

| 300 | 10,1 | |

| 400 | 6,1 | |

| 500 | 1,1 | |

| 600 | 0,4 | |

| Seven weeks after planting | 0 | 96,8 |

| 25 | 0,4 | |

| 50 | 1,1 | |

| 100 | 1,1 | |

| 200 | 0,7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).