1. Introduction

Cancer health inequities among African American men and women are well documented (Giaquinto et al., 2022). Strategies to address cancer disparities among this and other racial/ethnic minorities are therefore a top priority in national, regional, and local cancer prevention programs (Adsul et al., 2022; Force, 2019; Rodman, Mishra, & Adsul, 2022). Among these efforts are dissemination and implementation of evidence-based practices within community settings (Allen et al., 2020). Community-based public health programs aimed to reach minoritized populations have incorporated factors for cultural appropriateness however, a gap remains in identifying inequitable communication factors that may further exacerbate optimal dissemination and implementation of evidence-based practices (Lumpkins et al., 2023; Sharpe et al., 2018; Shelton et al., 2017; S. Suther & G.-E. Kiros, 2009). The cancer burden among African Americans (DeSantis et al., 2019; Institute, 2023; Prevention, 2023), and information inequalities necessitates culturally appropriate strategies to mitigate both primary and secondary cancer screening disparities and information gaps to increase equitable outcomes(Cameron, 2013; Halbert, Kessler, & Mitchell, 2005; Pagán et al., 2009; Ricker et al., 2018). In addressing these screening deficiencies, health promotion programs have evolved from individual-level (Institute, 2020) to multi-level interventions aimed to identify impediments or facilitators to equitable cancer outcomes(Gorin et al., 2012).These factors account, in part, for an individual’s perceptions of well-being and ability to respond within a given environment (Disparities, 2017). Integrating evidence based and best clinical practices and tools that address individual-level cancer risk within community settings may help reduce information inequity and other barriers among minoritized populations.

Hereditary cancer risk assessments (HCRA) (Oncology, 2003; Robson et al., 2015; Stadler et al., 2014; van Dijk et al., 2014; Xuan et al., 2013) are part of foundational processes/services and precision medicine tools that detect inheritable genetic variants that increase an individual’s risk for developing certain cancers, and are national clinical evidence-based practice recommendations for those who have been diagnosed with specific cancers(van Dijk et al., 2014). While these clinical tools are evidence-based practices utilized among genetic counselors and other medical personnel, some groups, including under-represented and minoritized populations are not aware of nor receive these services or technologies (Jones et al., 2016; Khoury et al., 2018; Mai et al., 2014; McCarthy et al., 2016; Pagán et al., 2009; Singer, Antonucci, & Van Hoewyk, 2004; S. Suther & G. E. Kiros, 2009). Among African Americans, studies show the uptake of HCRA tools and services is significantly lower due to barriers that include limited awareness, recognition of risk, lack of provider recommendation and inadequate access(Halbert, Kessler, & Mitchell, 2005; Hann et al., 2017; S. Suther & G.-E. Kiros, 2009). African American populations are also less likely to undergo genetic testing once they are diagnosed with cancer as well as preventive testing (prior to diagnosis)(Kurian et al., 2023). In one study, African American women had a lack of support for obtaining counseling and subsequent genetic testing in resource-limited settings(Randall, 2016). This was because, in part, a result of incomplete family health history information, an important factor in risk assessment for genetic counseling and testing recommendation.

Although HCRA technologies and services have positively impacted cancer outcomes, cancer risk assessment has primarily benefited non-racial/ethnic communities(Halbert, Kessler, & Mitchell, 2005; Hann et al., 2017; Hong et al., 2024). Employing public health efforts that reach under-represented populations in community settings where existing public health promotion programming exists increases the likelihood of uptake(Allen et al., 2016). Community and participatory focused strategies have shown effective in addressing multi-level factors that impact cancer outcome across the continuum of cancer care (Gorin et al., 2012; Zapka & Cranos, 2009). These strategies span from addressing individual level cancer risk perceptions to interpersonal and organizational (Guimond et al., 2022) and system barriers. Concomitantly, cancer communication and information strategies as part of public health promotion programming and strategically targeted to minoritized populations, show impactful on health risk perceptions, behavior and cancer outcome(Hall et al., 2015; Viswanath et al., 2012). Perceptions about cancer risk, judgement of risk acceptability, self-efficacy, trust in medical personnel and how communication and information is exchanged within a defined environment is necessary for effectiveness of the target behavior (HCRA uptake). Here too, communication about cancer risk may be impaired without targeted and culturally tailored information(Kreuter et al., 2003) to address attitudes, perceptions and beliefs about cancer, genetics, and HCRA for cancer risk (Chavez-Yenter, Chou, & Kaphingst, 2020; Kaphingst et al., 2019; Lumpkins et al., 2023; Peterson et al., 2018). Engagement with racial/ethnic minority communities to explore attitudes, perceptions, and beliefs about HCRA (Lumpkins et al., 2023; Lumpkins et al., 2020) shows these communities are receptive to different types of cancer prevention information. Further, integrating trusted community members into HCRA information dissemination has promise to help mitigate long-standing mistrust, fear, access and other barriers.

Given the strength of public health efforts and public health communication strategies aimed to help reduce cancer disparities in community settings(Allen et al., 2016; Hall et al., 2015; Holt et al., 2014; Kaphingst et al., 2019), barriers to disseminating evidence-based technologies and practices akin to Family Health Histories and genetic counseling and testing within minoritized populations may be reduced. To identify opportunities for HCRA information dissemination among African Americans, we followed a participatory approach to guide our inquiry. Communication Asset Mapping (CAM), a public health communication strategy, and Communication Infrastructure Theory were used as a framework to engage African American residents in mapping communication assets and subsequently create a pilot Communication Resource Asset Map to assist in disseminating HCRA information within African American faith communities in the Midwest. To the authors’ knowledge, this is one of the first studies to explore CAM through a participatory approach for HCRA information dissemination among an under-represented population.

2. Materials and Methods

Following IRB approval #00147613, through the University of Kansas Medical Center, recruitment began August 2021 and concluded September 2021. Trained Community Advisory Board (CAB) members were the primary mode of recruitment. The research team followed a participatory approach with the CAB and later engaged with African American residents through semi-structured community discussions where asset mapping of communication resources for Hereditary Cancer Risk Assessment (HCRA) was conducted. Community Asset mapping similar to asset mapping, is a public health method recommended for identification of communication assets within specified areas or neighborhoods (Broad et al., 2013; Burns, 2012; Estrada et al., 2018; Luo et al., 2023; Villanueva, 2021). This mapping process helped guide participatory work with CAB members and community participants in identification of communication assets for HCRA information dissemination within 2 African American faith community networks in the Midwest. Communication Infrastructure Theory (CIT) provided an explanatory guide to explore the ecological exchange of transformative(Manojlovich et al., 2015) communication that could occur between Lay Health Advisors and communication assets within African American faith networks about HCRA information. The CIT (Broad et al., 2013; Wilkin, 2013) framework describes the flow of communication and components and includes: 1) a storytelling network component that comprises creators and consumers of communication and information 2) a communication action context that includes communication assets/resources in the surrounding environment that may “facilitate or impede communication between creators and consumers,” (BALL-ROKEACH, KIM, & MATEI, 2001; Broad et al., 2013). CIT increases understanding of resources in the public information environment as “an ecological system wherein creators and consumers of communication at multiple levels, including individuals, social networks, community organizations, and media, are nested within a community where communication is shaped by geography, the built environment, and organizational and political structures and systems,” (Estrada et al., 2018) (p. 774). CIT provides a framework that helps determine what organizations or people within a community help shape information and how information is spread from individuals to groups. In the context of HCRA information dissemination, the story telling network (communication assets/resources within a defined geographic area of African American communities) was explored as a communication network between Lay Health Advisors, community members and trusted organizations (e.g., faith-based organizations). This story telling network was posited as an avenue for HCRA public health information dissemination (Broad et al., 2013; Estrada et al., 2018) and a robust infrastructure for CAM.

Communication Asset Mapping (CAM)is akin to the public health method ‘asset mapping’, a theory-based fieldwork and participatory methodology (Estrada et al., 2018) that allows for the mapping of “local geography and has an important role in shaping well-being” (p.775). The present study included community residents and a CAB (N=8) (Faith Works Connecting for a Healthy Community). The CAB engaged with the research study team and 2 Faith-Based Organizations (FBOs) from October 2020 to September 2021 to discuss results from exploratory cancer-related genetic counseling and testing projects that would inform the present project. The research team and IRB-trained CAB members subsequently recruited community resident participants through purposive sampling (Palinkas et al., 2015). Community participants received a secure link via email and consented into the study prior to taking a demographic survey (see table 1). Participants (N=26) self-identified as African American, were affiliated with a predominately African American Faith-Based Organization(FBO), were a resident of Kansas or Missouri and were familiar with the geographic areas within a 2-mile radius of the study FBOs (N=2). After completion of the survey, participants were contacted by research staff or an IRB-trained CAB member with a calendar invitation.

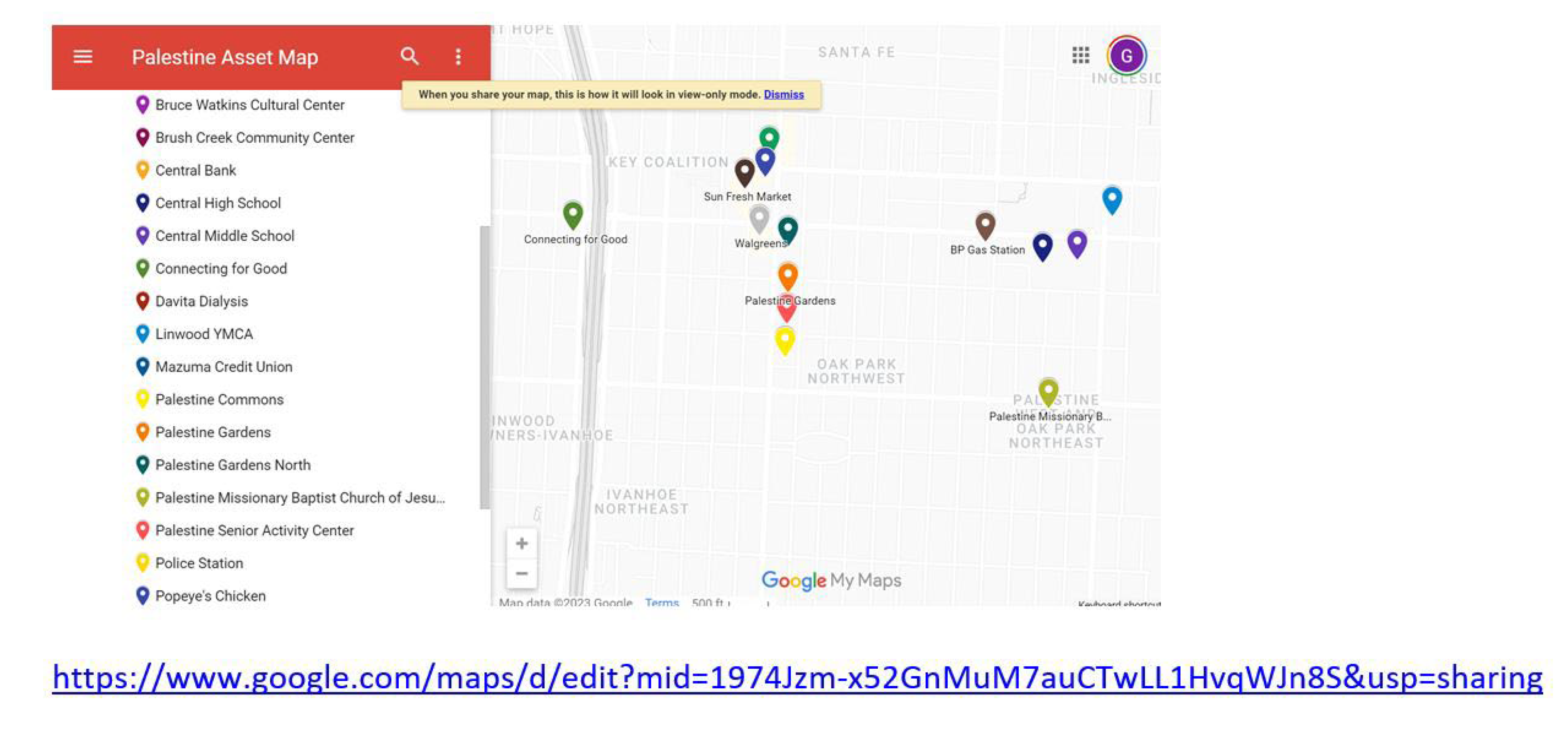

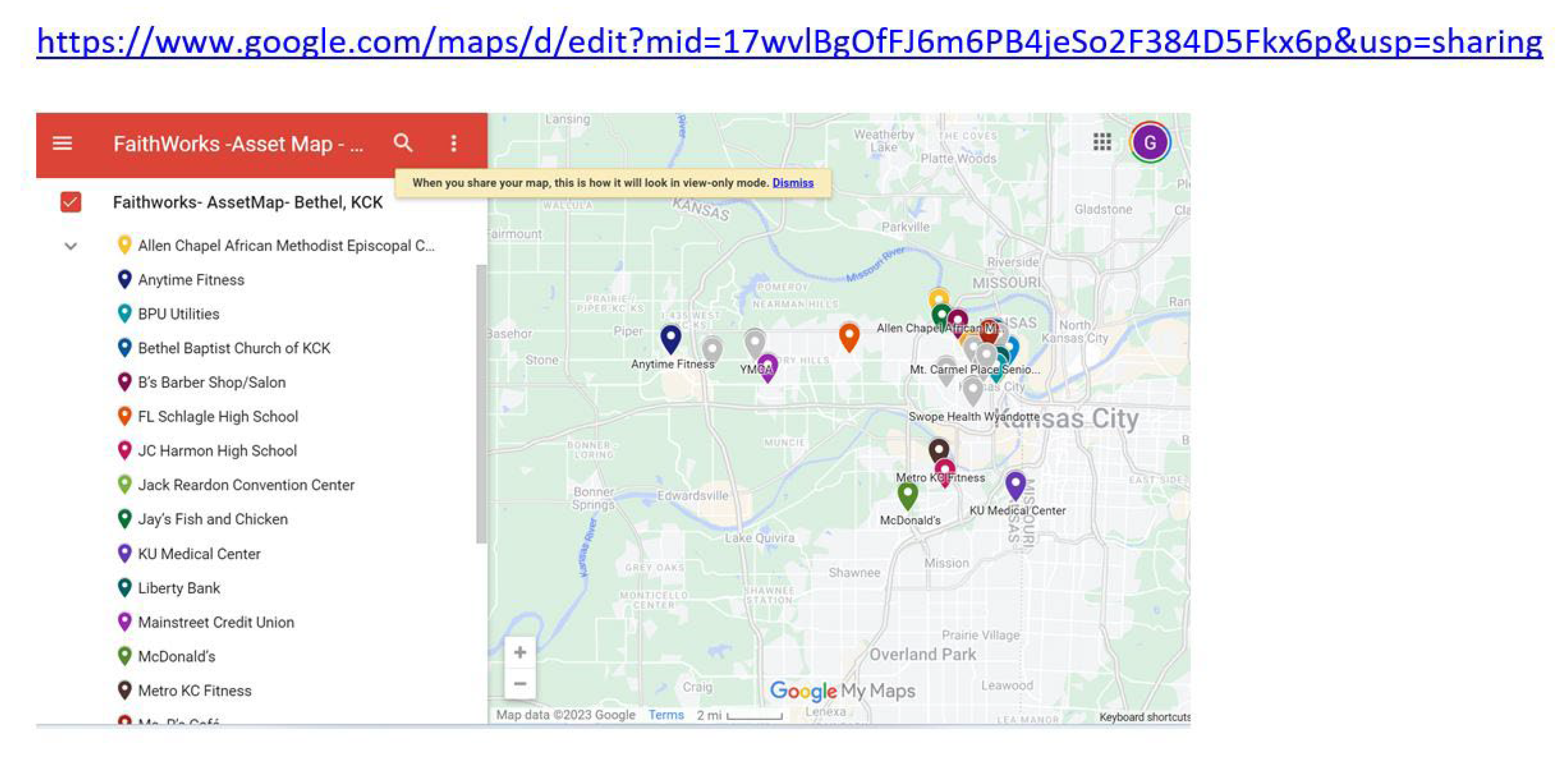

Prior to the group discussions, CAB members met with research staff twice to hold mock sessions to determine and confirm procedures and to resolve any issues encountered with conducting discussion groups via an online platform. Two CAB members who also worked in the Information Technology(IT) industry created scoring sheets (PDFs) where CAB members and research staff could rank communication assets/resources within the defined geographic areas for 2 FBOs. The IT CAB members also created 2 Google maps based on the team’s selection process to identify geographic locations within a 2-mile radius of the FBOs (see appendices). The result from the first Mock session was to have an electronic scoring sheet and also interactive Google Map in preparation for the session with community members. During the second session, the IT CAB members also suggested that a jot form be used for participants to rank pre-identified communication assets/resources for HCRA information dissemination. The rationale for doing this was to have a form that participants could easily fill out to rank not only the asset but also to provide a rationale for why the asset was an important communication asset. The form would also serve as a repository of information for the team. The CAB however experienced several access issues. Members encountered problems with leaving the platform to go to another site to retrieve the jot form and then to get back to the original online platform. Some individuals using their phone had trouble navigating between Zoom and the jot form while others who were in the same home experienced log-on issues. These experiences were valuable to the CAB as it prepared the group for issues that participants could possibly face for the virtual discussion group. The IT CAB members suggested that for the virtual discussion groups, the online platform tools (real-time polling) should be used. IT members also created virtual maps (Google) with interactive components where participants would be able to see a visual of the location when selecting a space on the map. These maps were a part of the packet shared with the 5 facilitators for 5 break out groups.

On the day of the community group discussions, the research team and CAB met 30 minutes prior to the event and pre-assigned participants to a virtual break out discussion group. At the start of the workshop, participants were let into the main room and given a welcome by the CAB chair and Principal Investigator and read a script about their participation.. After the introduction and instructions, the participants were then sent to their pre-assigned break out room. Facilitators were asked to record their session for data collection and to participate in a debriefing session after the closing segment of the workshop. Participants were thanked for their time and given instructions for receiving incentives ($50 electronic Wal-Mart gift cards). They were also informed that the team would follow up with them to administer a post survey and share results within the next six months.

The Principal Investigator and 2 IRB-trained CAB members first met for qualitative coding training. CAB members went through 2, 2-hour qualitative coding trainings and commenced to individually code facilitator workshop transcripts after training was completed. Coders met three times to perform constant comparison coding of 5 community group discussions (Strauss, 1990). Once individual coding was completed, coders noted emerging themes from the group discussions.

3. Results

Participants were primarily female (n=19) (90%), highly educated (postbaccalaureate/graduate degrees), 60 years of age and more than half the sample (57%) had a household income of

$50to

$100,000 a year. The majority of the sample had a primary care provider (PCP) and saw the provider once a year (52%) or several times a year (43%) but had not talked with their PCP about HCRA (86%). In the post survey, the number of participants who had talked to the PCP about HCRA had risen slightly (9%) from 3 to 5 participants (see

Table 1).

Themes that emerged from the community group discussions included (see

Table 2): (1) Optimal locations (e.g. community centers) within identified networks (specified neighborhood networks) should have representatives who are trusted ambassadors to assist with HCRA information dissemination; (2) Trusted community member voices should fully represent the trusted network; and (3) Well-known and frequented geographic locations should be a true representation of participants’ neighborhoods for creating a robust health information network concerning HCRA.

The first theme captured what participants perceived as important people and locations that should be included as communication assets/community resources for HCRA information dissemination. The pre-identified locations were natural extensions of places within residents’ network that would have an individual (communication asset) that would serve as a trusted health ambassador for HCRA information dissemination. It was important that these communication assets were relatable (age), accessible (time) and were respected (notoriety) within the defined geographic area.

Participant (Group 3): “You have the children there but you have their parents, their grandparents or someone picking them up and the information could be there. So, when we’re thinking about prevention, it’s never too early to provide education, it’s never too early to start talking about prevention [15:00] because if we think across the large or the wider spectrum, we always talk about how we want to teach the younger, our children prevention in terms of don’t use drugs, don’t drink alcohol and they start at around seven or eight. If we’re saying which would be a good place if we want to talk about prevention, we have to start early and so the Boys and Girls Club have all of those people coming in and out of there at any given time.

Participant (Group 5): When you look at, I think it’s Number 3 (communication asset ranking), which churches worship could be valuable to us, it’s a time sensitive situation. As we all know, October is Breast Cancer Month and if we could get something done to those churches doing Breast Cancer Month, I think that will be very impact (full). At Church X, we actually have a breast cancer ministry. Well, it’s not breast. It’s a cancer ministry and so they deal with not only breast cancer. They deal with any cancer the third Sunday is the emphasis Sunday for that event. If you could work around being time sensitive with it, the churches would be a great avenue to really plug into.

Participants also expressed that there were missing community members from the workshop and that this would impact the overall process for completing an inclusive communication asset mapping strategy. Representation from organizations that focused on youth, specific media outlets in the area that had an emphasis on health and families were some of the communication assets/resources identified.

Participant (Group 5): “I was going to say there are two dermatologists that are doctors that may be interested, Dr. XX . He’s in Kansas City, Missouri and then Dr. XX. She is in Kansas. I think she’s in [crosstalk]”.

Participant (Group 2): “There’s something else I thought about and I don’t know how you would feel about this but what about the black newspaper?”

Participant (Group 3): “And the other thing is that again with the different generations because there are multigenerational people coming in and out of there (location) and so we have to look at and think about those people and the people that are coming in and out and we look at their view of their family. Many of them have experienced some type of illness, major illness, traumatic illness within their families and so a lot of them have more information than we know.”

CAB and research staff attempted to include an exhaustive list of communication assets within the poll during the community workshop however community participants expressed there were missing locations that should have been added as assets to rank based on the ranking system given (ABCD or asset-based community development)(Burns, 2012).

Participant (Group 1) : “I was going to say the new Martin Luther King Park that they just opened. I’ve seen a lot of people out there on Sunday mornings when I’m going to church. I see a lot of people out there.”

Participant (Group 1): “Perhaps when they have the Juneteenth celebration there could be a table at the 18th and Vine area, the Juneteenth celebration.”

Participant (Group 2): “Don’t leave out the schools because the schools have parent groups that are still trying to be active and be pertinent and present things for families and [crosstalk] families of school children could be going through some of these issues and so the information could be right there at the school.”

Participant (Group 3): “I think that Brush Creek Community Center is a good location and I think it’s a good place to disseminate information.

Participant (Group 4) : “Then there are also community services that are in each one of the communities and here the post office, Central Bank, Mazuma Credit Union were listed and again a great place for flyers, for brochures, a high-volume location or lots of people go to this location and it’s necessary to receive other important information.”

4. Discussion

Conducting community group discussions with a dedicated CAB and residents demonstrated as a feasible and robust participatory approach to conduct qualitative inquiry (Burns, 2012)concerning communication asset mapping for HCRA information dissemination. Here, a seemingly little known and difficult subject to discuss, HCRA, was approachable because of the participation and leadership of trusted community leaders and HCRA experts (Bellhouse et al., 2018; Ramanadhan et al., 2018) from a familiar community network. To conduct virtual community group discussions, it was important to have a diverse and dedicated group (CAB and research team) to recruit, prepare for and conduct group discussions. The diversity of community lived experience and research expertise led to rich discussions in CAB meetings and brainstorming to address the challenges encountered. As with any Community-engaged research project, it is important to maintain research ethics and include stakeholders in all phases of the research process (Israel et al., 1998; Israel, 2003).

The group modified an “in-person” process for community engagement (Villanueva, 2021) and adopted it for on-line group discussions. Although this public health communication strategy (CAM) was feasible to adopt, there were key considerations to note during the process. Through the adoption of this type of strategy and the way it was employed through a virtual platform, it was important to include an assessment of digital literacy and also knowledge of asset mapping prior to the meeting. Findings from this exploratory study provide detailed methodological guidance for conducting CAM in medically underserved and minoritized communities. In this study, we focused on exploring the use of the Communication Asset Mapping (CAM) approach to develop a dissemination platform to improve awareness, knowledge and prospects of HCRA program implementation within African American populations. The creation of a foundation for an information-rich infrastructure may provide a robust environment for HCRA information dissemination and subsequent program implementation.

Using the CAM strategy, researchers were able to collectively rank and map communication assets within 2 geographically defined Faith Based Organizations (FBO) networks in the Midwest. The resulting pilot Communication Resource Asset Map is reasoned to be instrumental in identifying and assisting trusted Lay Health Advisors with disseminating HCRA information within these communities and also building information infrastructure within their own community organizations.

The focus on CAM for improving HCRA information dissemination among minoritized populations holds promise to address cancer disparities and cancer health outcomes. In the present project, the engagement of community members throughout the processes in CAM helped identify community asset-oriented communication resources within specific geographic locations where HCRA information dissemination would address a deficit of awareness about HCRA. The asset mapping process also allowed the research team to collaboratively identify geographic areas with trusted community members/leaders that would most likely optimize opportunities for Lay Health Advisors to bolster HCRA information and education within medically underserved communities. Because FBOs have served as viable places where cancer evidence-based(Hou & Cao, 2018) (Haynes et al., 2014)interventions and health communication programs are effective among African Americans(Holt et al., 2014; Resnicow et al., 2004), it is plausible that these organizations are also poised as acceptable and feasible community settings where HCRA information can be disseminated and implemented widely. This study explored, based on previous research among African American faith community members’ positive perceptions toward HCRA tools and technology(Lumpkins et al., 2020), the role that Communication Asset Mapping (CAM) may have in guiding HCRA information dissemination and future implementation of HCRA tools and technologies among African American populations in the Midwest.

Although HCRA tools (e.g. family health histories, genetic counseling and testing) have been clinically available for the last 30 years, a significant portion of the general population is still unaware that these tools and technologies exist(Roberts et al., 2022). As an example, in a recent national survey about genetic counseling and testing, oncologists reported that they were less likely to refer African American women than European American women(Ademuyiwa et al., 2021).Our exploratory studies show that African American faith and other minoritized communities are receptive to this type of information(Lumpkins et al., 2023; Lumpkins et al., 2020) and to provider recommendation for these technologies. Clinical efforts in tandem with ongoing community-based efforts provide multiple avenues communities may benefit from cancer prevention tools to reduce cancer disparities. Communication asset mapping (CAM) within communities could inform clearly defined dissemination strategies within the clinical setting as well. This strategy, as part of culturally tailored dissemination and implementation (D & I) strategies and the D & I continuum, has potential to also bolster implementation of clinical decision aids, integration of genetic literacy tools among patients and shape lay navigation communication to clinical settings. While clinical environments and settings are different in size and operation when compared to community-based settings, there are considerations that require assessment and evaluation in both settings (e.g., credibility, trust, timing, reach, effectiveness). The CAM approach is a context specific dissemination and implementation strategy that considers cultural contexts and also aims to increase information equity within a uniquely defined information infrastructure or communication action context. This research gives insight on where community awareness efforts can be targeted and optimized for at-risk individuals which could provide the motivation to undergo HCRA.

The focus of the project was to identify targets of change within an engagement communication action context for HCRA information dissemination. Here, the goal was to leverage existing African American FBO partnerships, previously collected psycho-social data concerning HCRA risk assessment and known barriers and facilitators among African Americans concerning cancer risk and prevention(Corbie-Smith, Thomas, & St George, 2002; Corbie-Smith et al., 1999) to inform our participatory research process. In addition, the Communication Information Theory (CIT) provided a framework to identify specific people (communication assets) within a defined geographic area and network as integral to HCRA information dissemination with these networks. Findings from the community group discussions show that trusted messengers within faith community networks (clinicians, teachers and parents) with lived experience and Lay Health Advisors were important representatives that could act as credible communicators and disseminators of HCRA information. While community members were not queried about specific HCRA messaging and message content, it is worth noting that these message elements are critical to how disseminators would shape this type of information to impact scale up of specific types of HCRA information and also awareness and knowledge outcomes. Depending on what and how risk messages (type of HCRA, dosage and framing of risk probabilities as a loss or win) are incorporated into HCRA information, may pose as barriers or facilitators to the adoption of CAM as a dissemination strategy. Community-engaged approaches that facilitate co-creation and development of messaging strategies increase relevance, acceptability and yielding as community voices are embedded into the process. The distinction here is the role of CAM itself in improving dissemination and subsequently adoption of the strategy within a specific information environment or setting. The role of CAM and leveraging communication assets is critical to promote Evidence-Based Practices (EBPs) within African American faith networks. Findings from this study further support the role of CAM in informing implementation strategies for public health.

The reception for the community group discussions was overall positive however there were some limitations that weakened results from the community-engaged process to explore Communication Asset Mapping HCRA information dissemination. While the FBOs were located in a bi-state area, individual participants from those organizations were familiar with activities only within their state of residency (Kansas or Missouri); thus, limiting their ability to rank communication assets within the entire area. This sample was also highly educated and motivated which could have lessened our scope for assets that may have been more beneficial for those with fewer financial or educational resources. Participants also had varying levels of computer literacy skills but were willing to hop online because of someone they knew. Dissimilar skills among participants extended time in group discussions and also comprehension at the conclusion of the workshop and in the post-survey. Two mock workshop meetings were held in preparation prior to community group discussions however there were technical issues that neither the IT CAB members nor research staff had anticipated. Participants who logged onto the online platform under alternate names or aliases had to be assigned to break out rooms during the session and this technical issue delayed the discussions for 2 groups. CAB members who oversaw technology worked to resolve issues and these participants eventually made it to their assigned break out room. Despite technological issues, the CAB chair was central to the design and study tools developed and essential to facilitating the process to ensure that everything would go as planned. The chair’s work to build the study CAB was critical to the community group discussions and helped maintain a consistency in meetings and participation among CAB members. In addition to identifying study CAB members for the project, the chair helped replace CAB members who had competing obligations and gathered and disseminated pertinent information to the CAB. The chair also played a critical role in recruitment of residents to the community group discussions as this individual knew people from the African American faith communities and had insight that would be central to the research project. Although there were other members that were noted as being absent from the group discussions, the CAB chair led efforts to recruit many of the key community members who were essential for identifying communication assets.

5. Conclusions

This study adds to the Dissemination & Implementation (D &I) Science literature, by explicating the methodology around CAM as a strategy for HCRA information dissemination within African American communities. Through additional inquiry, CAM may also be applicable in implementation of EPBs within clinical settings for minoritized individuals. The process of identifying communication assets and leveraging the networks within neighborhoods and communities in which these populations live and discuss cancer and other health prevention information may inform how, when, where and what type of HCRA is culturally appropriate to adopt or adapt and eventually implement or de-implement. In furthering our position for the centrality of health communication and information in the dissemination and implementation process of HCRA evidence-based programs/practice, one example may be found in Albright and colleagues’ (Albright et al., 2022) efforts. Albright et al. pose the critical role of communication to facilitate implementation of evidence-based care (psychotherapy) in community mental health settings. Implications included delineating and identifying components and methods for effective communication where communication is included in the “exploration and preparation phases of implementation” of an EBP (p. 324). The authors also state that out of the 73 identified implementation strategies that “the field of implementation science has largely left unexcavated the details of how communication may be utilized to facilitate implementation, thus leaving it (communication) hiding in plain sight” (p. 325). Expanding how to communicate information around health, specifically precision medicine, is warranted given cancer communication disparities and the absence of precision medicine information for minoritized populations. More research is needed to explore and test the effectiveness of communication strategies, including CAM, designed to bolster dissemination and subsequently adoption and implementation of EBPs. Dissemination research, which is an overlapping but understudied field (Baumann et al., 2022)compared to health communication research, is an important focus for the field of D & I Science. Findings from this study have important theoretical implications for the role of communication in disseminating EBPs and may draw from the beginnings of Implementation Science and the pioneering work of Everett Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations(Rogers, 2004).

Finally, the inclusion of a focus on D & I research, it’s synergy with health communication approaches, have promise to inform strategies to increase awareness of precision medicine, and improve the adoption and implementation of evidence-based practices that improve cancer health outcomes. Study participants and CAB members reiterated several times the importance of trusted messengers in specific places within the community that were capable ambassadors of disseminating HCRA information and carrying other pertinent information through trusted networks. Empirical testing of risk-framed HCRA messages on multiple levels (individual, interpersonal, organizational, community) and what specific components would impact behavior is warranted for future public health communication studies. Here too, different types of communication strategies to disseminate evidence-based HCRA practice is warranted for future studies. These areas of research also have practical and research implications for D & I of similar precision medicine programs and practice in other minoritized communities and settings and for reduction of health inequities and cancer mortality for all.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Faith-Based Organization pastors and lay leaders at Palestine Missionary Baptist Church (Missouri) and Bethel Church (Kansas) who participated in the study. We also thank the Masonic Cancer Alliance, Center for Genetic Shared Health Equity (CGSHE) at the University of Kansas and also the CAB members who contributed to this project. This work was supported by an internal faculty research grant at the University of Kansas Medical Center located in Kansas City, Kansas.

Conflicts of Interest

None Declared.

Appendix A

Figure 1.

Communication Resource Asset Map (Missouri Faith Based Organization).

Figure 1.

Communication Resource Asset Map (Missouri Faith Based Organization).

Figure 2.

Communication Resource Asset Map (Kansas Faith Based Organization).

Figure 2.

Communication Resource Asset Map (Kansas Faith Based Organization).

References

- Ademuyiwa, F. O., Salyer, P., Tao, Y., Luo, J., Hensing, W. L., Afolalu, A., Peterson, L. L., Weilbaecher, K., Housten, A. J., Baumann, A. A., Desai, M., Jones, S., Linnenbringer, E., Plichta, J., & Bierut, L. (2021). Genetic Counseling and Testing in African American Patients With Breast Cancer: A Nationwide Survey of US Breast Oncologists. J Clin Oncol, 39(36), 4020-4028. [CrossRef]

- Adsul, P., Chambers, D., Brandt, H. M., Fernandez, M. E., Ramanadhan, S., Torres, E., Leeman, J., Baquero, B., Fleischer, L., Escoffery, C., Emmons, K., Soler, M., Oh, A., Korn, A. R., Wheeler, S., & Shelton, R. C. (2022). Grounding implementation science in health equity for cancer prevention and control. Implement Sci Commun, 3(1), 56. [CrossRef]

- Albright, K., Navarro, E. I., Jarad, I., Boyd, M. R., Powell, B. J., & Lewis, C. C. (2022). Communication strategies to facilitate the implementation of new clinical practices: a qualitative study of community mental health therapists. Transl Behav Med, 12(2), 324-334. [CrossRef]

- Allen, C. G., Duquette, D., Guan, Y., & McBride, C. M. (2020). Applying theory to characterize impediments to dissemination of community-facing family health history tools: a review of the literature. J Community Genet, 11(2), 147-159. [CrossRef]

- Allen, C. G. Allen, C. G., McBride, C. M., Balcazar, H. G., & Kaphingst, K. A. (2016). Community Health Workers: An Untapped Resource to Promote Genomic Literacy. Journal of Health Communication, 21(sup2), 25-29. [CrossRef]

- BALL-ROKEACH, S. J., KIM, Y.-C., & MATEI, S. (2001). Storytelling Neighborhood:Paths to Belonging in Diverse Urban Environments. Communication Research, 28(4), 392-428. [CrossRef]

- Baumann, A. A., Hooley, C., Kryzer, E., Morshed, A. B., Gutner, C. A., Malone, S., Walsh-Bailey, C., Pilar, M., Sandler, B., Tabak, R. G., & Mazzucca, S. (2022). A scoping review of frameworks in empirical studies and a review of dissemination frameworks. Implementation Science, 17(1), 53. [CrossRef]

- Bellhouse, S., McWilliams, L., Firth, J., Yorke, J., & French, D. P. (2018). Are community-based health worker interventions an effective approach for early diagnosis of cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychooncology, 27(4), 1089-1099. [CrossRef]

- Broad, G. M., Ball-Rokeach, S. J., Ognyanova, K., Stokes, B., Picasso, T., & Villanueva, G. (2013). Understanding Communication Ecologies to Bridge Communication Research and Community Action. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 41(4), 325-345. [CrossRef]

- Burns, J., Paul, D. (2012). A Community Research Lab Toolkit. Healthy City. Retrieved September from www.healthycity.org/toolbox.

- Cameron, K. A. (2013). Advancing Equity in Clinical Preventive Services: The Role of Health Communication. Journal of Communication, 63(1), 31-50. [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Yenter, D., Chou, W. S., & Kaphingst, K. A. (2020). State of recent literature on communication about cancer genetic testing among Latinx populations. J Genet Couns. [CrossRef]

- Corbie-Smith, G., Thomas, S. B., & St George, D. M. (2002). Distrust, race, and research. Arch Intern Med, 162(21), 2458-2463. [CrossRef]

- Corbie-Smith, G., Thomas, S. B., Williams, M. V., & Moody-Ayers, S. (1999). Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J Gen Intern Med, 14(9), 537-546. [CrossRef]

- DeSantis, C. E., Miller, K. D., Goding Sauer, A., Jemal, A., & Siegel, R. L. (2019). Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin, 69(3), 211-233. [CrossRef]

- Disparities, N. I. o. M. H. a. H. (2017). NIMHD Research Framework. National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Retrieved August 31 from.

- Estrada, E., Ramirez, A. S., Gamboa, S., & Amezola de herrera, P. (2018). Development of a Participatory Health Communication Intervention: An Ecological Approach to Reducing Rural Information Inequality and Health Disparities. Journal of Health Communication, 23(8), 773-782. [CrossRef]

- Force, U. P. S. T. (2019). Risk Assessment, Genetic Counseling, and Genetic Testing for BRCA-Related Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA, 322(7), 652-665. [CrossRef]

- Giaquinto, A. N., Miller, K. D., Tossas, K. Y., Winn, R. A., Jemal, A., & Siegel, R. L. (2022). Cancer statistics for African American/Black People 2022. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 72(3), 202-229. [CrossRef]

- Gorin, S. S., Badr, H., Krebs, P., & Das, I. P. (2012). Multilevel Interventions and Racial/Ethnic Health Disparities. JNCI Monographs, 2012(44), 100-111. [CrossRef]

- Guimond, E. Guimond, E., Getachew, B., Nolan, T. S., Miles Sheffield-Abdullah, K., Conklin, J. L., & Hirschey, R. (2022). Communication Between Black Patients With Cancer and Their Oncology Clinicians: Exploring Factors That Influence Outcome Disparities. Oncol Nurs Forum, 49(6), 509-524. [CrossRef]

- Halbert, C. H., Kessler, L. J., & Mitchell, E. (2005). Genetic testing for inherited breast cancer risk in African Americans. Cancer Invest, 23(4), 285-295. [CrossRef]

- Hall, I. J., Johnson-Turbes, A., Berkowitz, Z., & Zavahir, Y. (2015). The African American Women and Mass Media (AAMM) campaign in Georgia: quantifying community response to a CDC pilot campaign. Cancer Causes Control, 26(5), 787-794. [CrossRef]

- Hann, K. E. J., Freeman, M., Fraser, L., Waller, J., Sanderson, S. C., Rahman, B., Side, L., Gessler, S., Lanceley, A., & for the, P. s. t. (2017). Awareness, knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes towards genetic testing for cancer risk among ethnic minority groups: a systematic review. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 503. [CrossRef]

- Haynes, V. Haynes, V., Escoffery, C., Wilkerson, C., Bell, R., & Flowers, L. (2014). Adaptation of a cervical cancer education program for African Americans in the faith-based community, Atlanta, Georgia, 2012. Prev Chronic Dis, 11, E67. [CrossRef]

- Holt, C. L. Holt, C. L., Tagai, E. K., Scheirer, M. A., Santos, S. L. Z., Bowie, J., Haider, M., Slade, J. L., Wang, M. Q., & Whitehead, T. (2014). Translating evidence-based interventions for implementation: Experiences from Project HEAL in African American churches. Implementation Science, 9(1), 66. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y. R., Yadav, S., Wang, R., Vadaparampil, S., Bian, J., George, T. J., & Braithwaite, D. (2024). Genetic Testing for Cancer Risk and Perceived Importance of Genetic Information Among US Population by Race and Ethnicity: a Cross-sectional Study. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities, 11(1), 382-394. [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.-I., & Cao, X. (2018). A Systematic Review of Promising Strategies of Faith-Based Cancer Education and Lifestyle Interventions Among Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups. Journal of Cancer Education, 33(6), 1161-1175. [CrossRef]

- Institute, N. C. (2020). Transforming Research into Clinical and Community Practice. National Cancer Institute. Retrieved August 21 from.

- Institute, N. C. (2023). Cancer Stat Facts: Cancer Disparities. National Insitutes of Health - National Cancer Institute. Retrieved August 31 from https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/disparities.html.

- Israel, B. A., Schulz, A. J., Parker, E. A., & Becker, A. B. (1998). Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health, 19, 173-202. [CrossRef]

- Israel, B. A., Schulz, A.J., Parker, E.A., et al. . (2003). Critical issues in developing and following community-based participatory principles. Community Based Participatory Research for Health . (Minkler M., Wallerstein N., eds.) San Fran: CA: Jossey-Bass.

- .

- Jones, T., Lockhart, J. S., Mendelsohn-Victor, K. E., Duquette, D., Northouse, L. L., Duffy, S. A., Donley, R., Merajver, S. D., Milliron, K. J., Roberts, J. S., & Katapodi, M. C. (2016). Use of Cancer Genetics Services in African-American Young Breast Cancer Survivors. Am J Prev Med, 51(4), 427-436. [CrossRef]

- Kaphingst, K. A., Peterson, E., Zhao, J., Gaysynsky, A., Elrick, A., Hong, S. J., Krakow, M., Pokharel, M., Ratcliff, C. L., Klein, W. M. P., Khoury, M. J., & Chou, W. S. (2019). Cancer communication research in the era of genomics and precision medicine: a scoping review. Genet Med, 21(8), 1691-1698. [CrossRef]

- Khoury, M. J., Bowen, M. S., Clyne, M., Dotson, W. D., Gwinn, M. L., Green, R. F., Kolor, K., Rodriguez, J. L., Wulf, A., & Yu, W. (2018). From public health genomics to precision public health: a 20-year journey. Genet Med, 20(6), 574-582. [CrossRef]

- Kreuter, M. W., Lukwago, S. N., Bucholtz, R. D., Clark, E. M., & Sanders-Thompson, V. (2003). Achieving cultural appropriateness in health promotion programs: targeted and tailored approaches. Health Educ Behav, 30(2), 133-146. [CrossRef]

- Kurian, A. W., Abrahamse, P., Furgal, A., Ward, K. C., Hamilton, A. S., Hodan, R., Tocco, R., Liu, L., Berek, J. S., Hoang, L., Yussuf, A., Susswein, L., Esplin, E. D., Slavin, T. P., Gomez, S. L., Hofer, T. P., & Katz, S. J. (2023). Germline Genetic Testing After Cancer Diagnosis. JAMA, 330(1), 43-51. [CrossRef]

- Lumpkins, C. Y., Nelson, R., Twizele, Z., Ramírez, M., Kimminau, K. S., Philp, A., Mustafa, R. A., & Godwin, A. K. (2023). Communicating risk and the landscape of cancer prevention - an exploratory study that examines perceptions of cancer-related genetic counseling and testing among African Americans and Latinos in the Midwest. J Community Genet, 14(2), 121-133. [CrossRef]

- Lumpkins, C. Y., Philp, A., Nelson, K. L., Miller, L. M., & Greiner, K. A. (2020). A road map for the future: An exploration of attitudes, perceptions, and beliefs among African Americans to tailor health promotion of cancer-related genetic counseling and testing. J Genet Couns, 29(4), 518-529. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y., Ruggiano, N., Bolt, D., Witt, J.-P., Anderson, M., Gray, J., & Jiang, Z. (2023). Community Asset Mapping in Public Health: A Review of Applications and Approaches. Social Work in Public Health, 38(3), 171-181. [CrossRef]

- Mai, P. L., Vadaparampil, S. T., Breen, N., McNeel, T. S., Wideroff, L., & Graubard, B. I. (2014). Awareness of cancer susceptibility genetic testing: the 2000, 2005, and 2010 National Health Interview Surveys. Am J Prev Med, 46(5), 440-448. [CrossRef]

- Manojlovich, M., Squires, J. E., Davies, B., & Graham, I. D. (2015). Hiding in plain sight: communication theory in implementation science. Implementation Science, 10(1), 58. [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, A. M., Bristol, M., Domchek, S. M., Groeneveld, P. W., Kim, Y., Motanya, U. N., Shea, J. A., & Armstrong, K. (2016). Health Care Segregation, Physician Recommendation, and Racial Disparities in BRCA1/2 Testing Among Women With Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol, 34(22), 2610-2618. [CrossRef]

- Oncology, A. S. o. C. (2003). American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update: genetic testing for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol, 21(12), 2397-2406. [CrossRef]

- Pagán, J. A., Su, D., Li, L., Armstrong, K., & Asch, D. A. (2009). Racial and ethnic disparities in awareness of genetic testing for cancer risk. Am J Prev Med, 37(6), 524-530. [CrossRef]

- Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm Policy Ment Health, 42(5), 533-544. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, E. B., Chou, W. S., Gaysynsky, A., Krakow, M., Elrick, A., Khoury, M. J., & Kaphingst, K. A. (2018). Communication of cancer-related genetic and genomic information: A landscape analysis of reviews. Transl Behav Med, 8(1), 59-70. [CrossRef]

- Prevention, C. f. D. C. (2023). African American People and Cancer. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Retrieved August 31 from.

- Ramanadhan, S., Davis, M. M., Armstrong, R., Baquero, B., Ko, L. K., Leng, J. C., Salloum, R. G., Vaughn, N. A., & Brownson, R. C. (2018). Participatory implementation science to increase the impact of evidence-based cancer prevention and control. Cancer Causes & Control, 29(3), 363-369. [CrossRef]

- Randall, T. C., Armstrong, K. . (2016). Health Care Disparities in Hereditary Ovarian Cancer: Are We Reaching the Underserved Population?. . Current Treatment Options in Oncology, 17(39 ), 1-8.

- Resnicow, K., Kramish Campbell, M., Carr, C., McCarty, F., Wang, T., Periasamy, S., Rahotep, S., Doyle, C., Williams, A., & Stables, G. (2004). Body and soul: a dietary intervention conducted through African-American churches. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 27(2), 97-105. [CrossRef]

- Ricker, C. N., Koff, R. B., Qu, C., Culver, J., Sturgeon, D., Kingham, K. E., Lowstuter, K., Chun, N. M., Rowe-Teeter, C., Lebensohn, A., Levonian, P., Partynski, K., Lara-Otero, K., Hong, C., Petrovchich, I. M., Mills, M. A., Hartman, A. R., Allen, B., Ladabaum, U., . . . Idos, G. E. (2018). Patient communication of cancer genetic test results in a diverse population. Transl Behav Med, 8(1), 85-94. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M. C., Foss, K. S., Henderson, G. E., Powell, S. N., Saylor, K. W., Weck, K. E., & Milko, L. V. (2022). Public Interest in Population Genetic Screening for Cancer Risk. Front Genet, 13, 886640. [CrossRef]

- Robson, M. E., Bradbury, A. R., Arun, B., Domchek, S. M., Ford, J. M., Hampel, H. L., Lipkin, S. M., Syngal, S., Wollins, D. S., & Lindor, N. M. (2015). American Society of Clinical Oncology Policy Statement Update: Genetic and Genomic Testing for Cancer Susceptibility. J Clin Oncol, 33(31), 3660-3667. [CrossRef]

- Rodman, J., Mishra, S. I., & Adsul, P. (2022). Improving Comprehensive Cancer Control State Plans for Colorectal Cancer Screening in the Four Corners Region of the United States. Health Promot Pract, 15248399211073803. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. M. (2004). A Prospective and Retrospective Look at the Diffusion Model. Journal of Health Communication, 9(sup1), 13-19. [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, P. A., Wilcox, S., Kinnard, D., & Condrasky, M. D. (2018). Community Health Advisors' Participation in a Dissemination and Implementation Study of an Evidence-Based Physical Activity and Healthy Eating Program in a Faith-Based Setting. J Community Health, 43(4), 694-704. [CrossRef]

- Shelton, R. C., Charles, T.-A., Dunston, S. K., Jandorf, L., & Erwin, D. O. (2017). Advancing understanding of the sustainability of lay health advisor (LHA) programs for African-American women in community settings. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 7(3), 415-426. [CrossRef]

- Singer, E., Antonucci, T., & Van Hoewyk, J. (2004). Racial and ethnic variations in knowledge and attitudes about genetic testing. Genet Test, 8(1), 31-43. [CrossRef]

- Stadler, Z. K., Schrader, K. A., Vijai, J., Robson, M. E., & Offit, K. (2014). Cancer genomics and inherited risk. J Clin Oncol, 32(7), 687-698. [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. . (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. . Newbury Park: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Suther, S., & Kiros, G.-E. (2009). Barriers to the use of genetic testing: A study of racial and ethnic disparities. Genetics in Medicine, 11(9), 655-662. [CrossRef]

- Suther, S., & Kiros, G. E. (2009). Barriers to the use of genetic testing: a study of racial and ethnic disparities. Genet Med, 11(9), 655-662. [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, E. L., Auger, H., Jaszczyszyn, Y., & Thermes, C. (2014). Ten years of next-generation sequencing technology. Trends Genet, 30(9), 418-426. [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, G. (2021). Designing a Chinatown anti-displacement map and walking tour with communication asset mapping. Journal of Urban Design, 26(1), 14-37. [CrossRef]

- Viswanath, K., Nagler, R. H., Bigman-Galimore, C. A., McCauley, M. P., Jung, M., & Ramanadhan, S. (2012). The Communications Revolution and Health Inequalities in the 21st Century: Implications for Cancer Control. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 21(10), 1701-1708. [CrossRef]

- Wilkin, H. A. (2013). Exploring the Potential of Communication Infrastructure Theory for Informing Efforts to Reduce Health Disparities [https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12006]. Journal of Communication, 63(1), 181-200. [CrossRef]

- Xuan, J., Yu, Y., Qing, T., Guo, L., & Shi, L. (2013). Next-generation sequencing in the clinic: promises and challenges. Cancer Lett, 340(2), 284-295. [CrossRef]

- Zapka, J., & Cranos, C. (2009). Behavioral Theory in the Context of Applied Cancer Screening Research. Health Education & Behavior, 36(5_suppl), 161S-166S. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Socio-Demographic Information (N=21).

Table 1.

Socio-Demographic Information (N=21).

Age

Gender

Men (n=2)

Women (n=19)

Income

*Residency

Kansas (n=4)

Missouri (n=17)

Education

Medical Provider

Frequency of visits to the PCP

Talked to a PCP about HCRA Prior to Community Group Discussion(n=3)

Talked to a PCP about HCRA Post Community Group Discussion(n=2)

|

Age Mean (x̅)

60

10%

90%

57% ($50-100K);

19%

81%

Post Baccalaureate/Graduate Education (57%)

100%

52% Primary Care Provider (PCP) once a year

86% had not talked with their PCP about HCRA; 14% of the sample had talked with a PCP

9% increase

|

|

Table 2.

Themes and Sample Quotes from CAM Community Group Discussions.

Table 2.

Themes and Sample Quotes from CAM Community Group Discussions.

| Theme |

Sample Quotes |

|

Participant (Group 3): “If we’re saying which would be a good place if we want to talk about prevention, we have to start early and so the Boys and Girls Club have all of those people coming in and out of there at any given time.

Participant (Group 5): When you look at, I think it’s Number 3 (communication asset ranking), which churches worship could be valuable to us, it’s a time sensitive situation. As we all know, October is Breast Cancer Month and if we could get something done to those churches doing Breast Cancer Month, I think that will be very impact (full).”

|

- 2.

Trusted community member voices should fully represent the trusted network |

Participant (Group 2): “There’s something else I thought about and I don’t know how you would feel about this but what about the black newspaper?”

Participant (Group 3): “And the other thing is that again with the different generations because there are multigenerational people coming in and out of there (location) and so we have to look at and think about those people and the people that are coming in and out and we look at their view of their family.

|

- 3.

Well-known and frequented geographic locations should be a true representation of participants’ neighborhoods for creating a robust health information network concerning HCRA |

Participant (Group 1) : “I was going to say the new Martin Luther King Park that they just opened. I’ve seen a lot of people out there on Sunday mornings when I’m going to church. I see a lot of people out there.”

Participant (Group 4) : “Then there are also community services that are in each one of the communities and here the post office, Central Bank, Mazuma Credit Union were listed and again a great place for flyers, for brochures, a high-volume location or lots of people go to this location and it’s necessary to receive other important information.”

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).