1. Introduction

Suicide, which involves the intentional act of taking one's own life, is a major public concern across the world. Each year, over 700,000 people die by suicide globally, with more than 77% of these deaths occurring in low- and middle-income countries [

1]. Suicidal mortality is often attributed to many causes and may occur at a result of an exacerbation of major mental health problems; prior to death by suicide, one may have issues of suicidal behavior, which encompass suicidal ideation, threats or plans of suicide, suicide attempts, and completed suicides [

2,

3]. There is a wide array of potential risk factors for suicide, and these include affective disorders, addiction, antisocial behaviors, physical illness, being elderly, and a history of suicide attempts [

4,

5,

6].

Bharat (India) is a nation in which suicidality is a major concern. Bharat has the highest number of deaths by suicide compared to any other nation, and suicide has been shown to be the leading cause of death in those who are aged 15-39 [

7]. It has been demonstrated previously that factors associated with suicide mortality differ greatly from European and American nations, with marriage having previously been shown not to be a protective factor in Bharat, and the female to male ratio being higher in this country [

8]. Other risk factor previously noted in the country include traumatic/difficult family problems, academic stress, exposure to violence, and economic distress [

9].

In 2020, the coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic had begun. The pandemic has resulted in significant morbidity and mortality across the globe. It has been estimated that there have been more than seven million deaths attributed to COVID-19 worldwide [

10]. Along with the direct impacts of the virus, the pandemic has led to a challenging life circumstance for many, with the psychological impact of COVID-19 being adverse. Quarantine restrictions and lockdowns increased the risk of suicide by causing fear and panic, frustration, scarcity of basic supplies, lack of reliable information, perceived stigma, financial distress, and lack of physical exercise [

11]. Strict spatial distancing measures and social isolation tend to elevate anxiety levels, profoundly affecting vulnerable groups such as the elderly, individuals with preexisting medical conditions like respiratory issues, and those with preexisting mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety. These factors can significantly increase the risk of suicidality. Additionally, loneliness associated with lockdowns can lead to depression, which, if untreated, can drive individuals toward suicidal behavior [

12,

13]. As a result of all of this, in terms of mental health impacts, there have been significant rises in depression, with approximately 53 million more cases of depression, and 76 million more cases of anxiety disorders [

14]. In Bharat, similar patterns have been seen, with 23% out of 2640 adult respondents in a survey reporting major anxiety, and 26% reporting major depression [

15].

Despite the COVID-19 have been being declared over, concerns have been expressed regarding the persisting impacts of long COVID. The WHO defines long COVID (also referred to as post-COVID-19 condition) as an illness in individuals with a history of probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, usually three months after the onset of COVID-19, with symptoms lasting at least two months and these symptoms cannot be attributed to another diagnosis [

17]. Some research has shown that psychiatric consequences of COVID-19 are widespread and can persist beyond six months [

18]. Studies in Hong Kong and Colombia found that long COVID can worsen mental health, increasing depression and other psychiatric disorders [

19]. In Haryana, India, long COVID significantly impacted mental health, with participants reporting persistent anxiety, depression, and stress [

20]. A study in Eastern India found that 4% of long COVID patients post-Omicron wave self-reported depression [

21].

Despite the rising evidence of the potential impacts of long COVID, much is not known about this syndrome and its resultant impacts. In particular, the evidence regarding its impacts on suicidal behavior and suicide mortality among survivors of COVID-19 globally, and in Bharat, remains limited. Therefore, our objectives for this study were twofold: to assess the longer-term impacts of the COVID-19 on suicide mortality in Bharat at the state and national level, and to determine if long COVID may be a contributor to changes in suicide mortality rates across the nation.

2. Methods

For this work, we intended to analyse and compare trends in suicide across Bharat both before and after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. We did this by first evaluating total numbers of suicide and suicide rates (per 100,000 individuals) annually with national level data. More precisely, this entailed analysing trends in each of these parameters between the years of 2012 to 2022. These trends were visually depicted in figures. To analyse trends in further detail, we also evaluated annual increases/decreases between the years 2018 to 2019 with the average annual change from the years 2019 to 2022. Absolute increases/decreases, and percent changes across these time periods were evaluated.

After providing a comparison of national level trends, trends at the state and union territory (UT) levels were next analysed. With the exception of Jammu and Kashmir, Ladakh, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Daman and Diu, all states and UTs were included for our analyses. These states and UTs were excluded from this study due to issues with inconsistencies in the reporting of data across years for these regions. Once again, data on total number of suicides and suicide rates (per 100,000) individuals from 2018 to 2022 were provided and shown in tabular format. Annual absolute increases/decreases, and percent change were calculated for state/UT, and comparisons were made for 2018 to 2019 and the average annual change from 2019 to 2022. The most notable increases and decreases were thereafter described.

Data for suicide mortality across Bharat was retrieved from the annual reports known as the Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India (ADSI) by the National Crime Records Bureau of the Ministry of Home from each of the years between (and including) 2018 to 2022 [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. These reports contain publicly available data that is published annually by the Government of Bharat and contain detailed data on factors relating to suicide mortality, but also on mortality relating to accidental causes [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

Next, to assess for the role of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the potential role of long COVID, we aimed to analyse the relationship between COVID-19 incidence and mortality to suicide mortality. To do this, we conducted bivariable linear regression analysis between COVID-19 cases per 100 individuals and annual change in suicide rate from 2019 to 2022 at the state/UT level, and again between COVID-19 deaths per 10,000 individuals and annual change in suicide rates from 2019 to 2022 at the state/UT level. Thereafter, multivariable linear regression was conducted with annual change in suicide rates from 2019 to 2022 to the two aforementioned COVID-19 variables. COVID-19 data was acquired from publicly available datasets by the Government of Bharat [

27]. Statistical analysis was completed using SPSS [

28].

As this study did not involve human participants, and instead involved analysing data from publicly available sources, ethics board approval was not required.

3. Results

3.1. National Suicide Trends

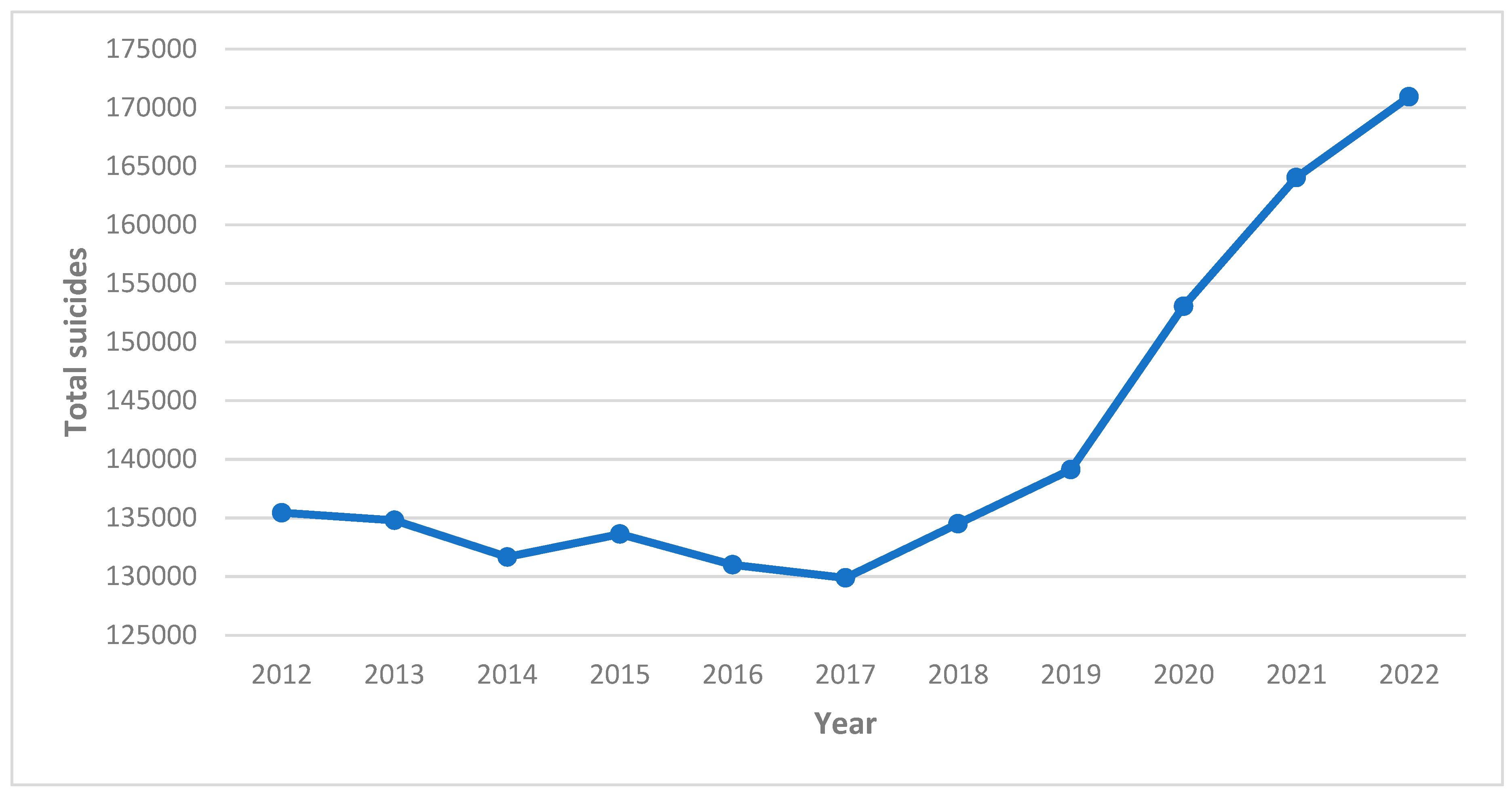

Long-term trends demonstrate that there has been a net decrease in total suicides between 2012 and 2017, from 135,445 annual deaths to 129,887. From 2017 onwards, the total number of suicides has increased as a national level, with the highest number of deaths occurring in 2022, at 170,924. However, the annual increase in total suicide deaths have risen since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Between 2018 and 2019, there was an annual increase of 4607 deaths (percent increase of 3.42%). In comparison, the average annual increase in deaths since 2020 was 10,600.33 (percent increase of 7.62%). A depiction of long-term annual suicide deaths is shown in

Figure 1.

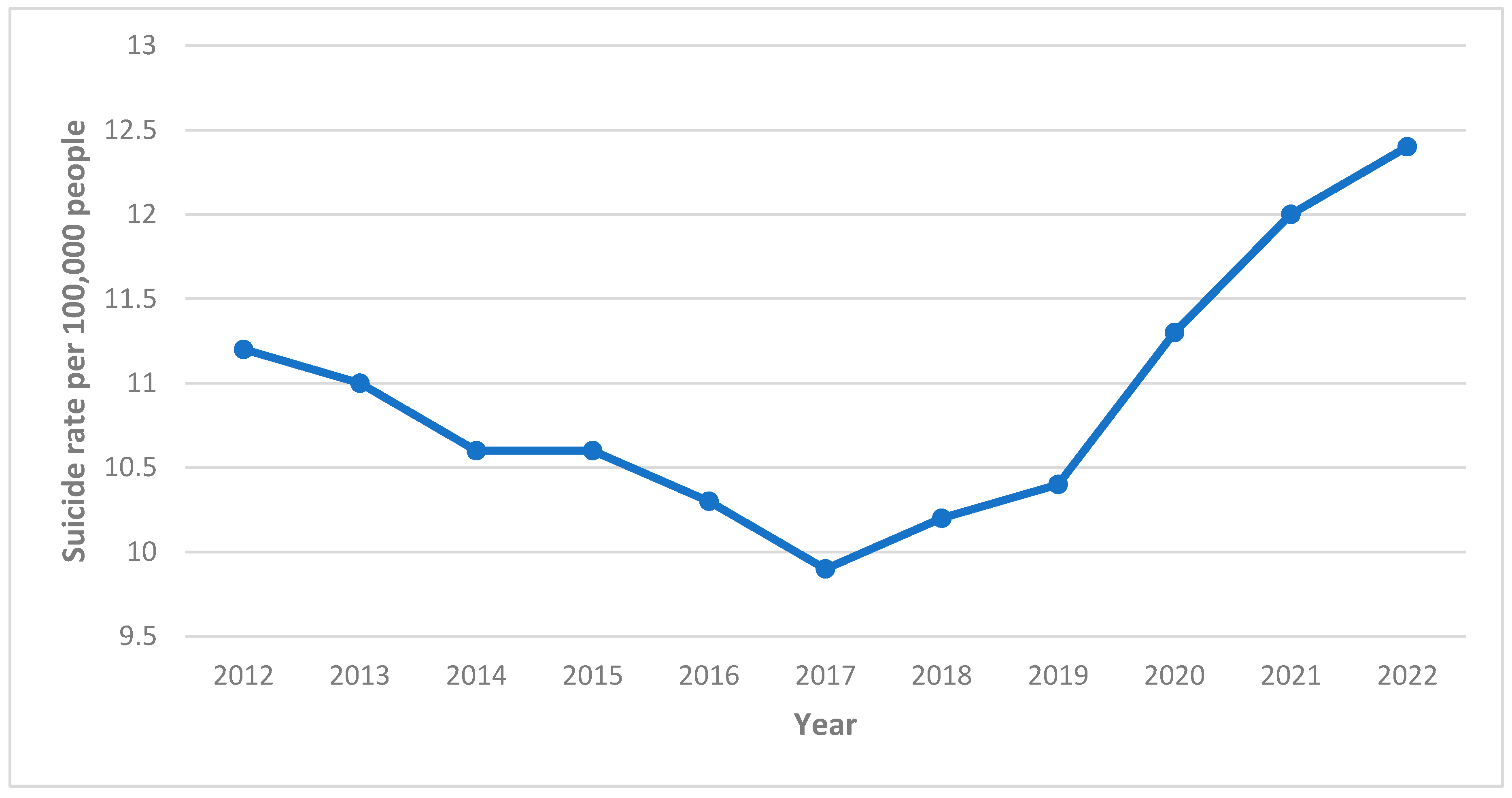

Similar trends have been shown for suicide rates at a national level. There were continual declines in suicide rate across Bharat from 2012 to 2017, decreasing from 11.2 suicides per 100,000 people to 9.9. However, after 2017, there were annual rises in the suicide rate across the country. Furthermore, the rise in suicide rates have accelerated since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Between 2018 and 2019, the suicide rates rose by 0.2 per 100,000 people (percent increase of 1.96), whereas the average annual increase between 2019 and 2022 was 0.7 per 100,000 people (percent increase of 6.41%). Long-term annual trends in suicide rates at the national level are shown in

Figure 2.

3.2. State Level Trends—Total Suicides

Trends across states and UTs in Bharat of total number of suicides are shown in

Table 1. Across the 33 states and UTs that were analysed, the majority had an overall increase in total suicides prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Between 2018 to 2019, 20 states and UTs had an increase in suicide rates, compared to 13 that had an overall decrease. The largest decreases in this period were in West Bengal (decrease by 590; 4.45% decrease), Tamil Nadu (decrease by 403; 2.90% decrease), Karnataka (decrease by 273; 2.36%), Telangana (decease by 170; 2.17% decrease), and Himachal Pradesh (decrease by 156; 21.08% decrease). In contrast, the largest increases occurred in Andhra Pradesh (increase by 1146; 21.55% increase), Maharashtra (increase by 944; 5.25% increase), Madhya Pradesh (increase by 682; 5.79% increase), Punjab (increase by 643; 37.51% increase), and Uttar Pradesh (increase by 615; 12.68% increase).

Overall, the highest number of suicides in 2022 occurred in Maharashtra (22,746 deaths), followed by Tamil Nadu (19,834), and Madhya Pradesh (15,386). After the start of the pandemic, there was an increase in total suicides across 28 states and UTs, with a decrease in five (Haryana, Manipur, Tripura, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and Puducherry). Haryana had the largest decrease, with an annual decline of suicide deaths of 136 per year (3.25% annual decrease). Overall, there was also a higher increase in total suicides annually from 2019 to 2022 compared to 2018 to 2019. States with the highest annual increases, despite an annual decrease from 2018 to 2019, were Tamil Nadu (2113.67 annual increase; 15.66% increase) Karnataka (772.67 annual increase; 6.85% increase), Telangana (768.33 annual increase; 10.01% increase), and Odisha (519.33 annual increase; 11.33% increase). Other states with the highest increase in total annual suicides after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic were Maharashtra (1276.67 annual increase; 6.75% increase), Madhya Pradesh (976.33 annual increase; 7.84% increase), Andhra Pradesh (814.33 annual increase; 12.60%), and Kerala (535.33 annual increase; 6.26% increase).

3.3. State Level Trends—Suicide Rates

Trends in suicide rates (per 100,000 people) across the states and UTs are shown in

Table 2 Across, the 33 states and UTs, suicide rates increased in 20 states and decreased in 13 from 2018 to 2019. The largest decreases in suicide rates occurred in Meghalaya (decrease by 9.9; 61.88% decrease), Lakshadweep (decrease by 4.3; 100% decrease), followed by Chandigarh (decreased by 2.6; 18.98% decrease), and Himachal Pradesh (decrease by 2.2; 21.57% decrease). In contrast, the largest increases in suicide rates occurred in Andaman and Nicobar Islands (increase by 4.5; 10.98% increase), Mizoram (increase by 3.4; 136.00% increase), Sikkim (increase by 2.9; 9.60% increase), and Andhra Pradesh (increase by 2.2; 21.57% increase). The change in suicide rate across states and UTs from 2018 to 2019 was a decrease of 0.05.

In terms of after the occurrence of the COVID-19, in 2022 the highest suicide rates per 100,000 people were in Sikkim (43.1), Andaman and Nicobar Islands (42.8), Puducherry (29.7), Kerala (28.5), and Chhattisgarh (28.2). After the start of the pandemic, there was an average annual rise in suicide rates across 27 states/UTs and a decrease in seven states/UTs (Haryana, Manipur, Tripura, West Bengal, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Chandigarh, and Puducherry). The largest decreases were in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, (decrease by 0.9; 1.98% decrease) and Haryana (decrease by 0.6; 4.37% decrease). While there was a decrease in the suicide rate from 2018 to 2019, the average annual change in suicide rates across states and UTs from 2019 to 2022 was an increase of 0.65. States/UTs with the highest annual increases since the start of the COVID-19, despite a decrease from 2018 to 2019, were Tamil Nadu (increase by 2.7; 15.17% increase), Telangana (increase by 1.9; 9.22% increase), Delhi (increase by 1.2; 9.19% increase), Karnataka (increase by 1.0; 6.04% increase), and Assam (increase by 0.8; 12.08% increase). Other states with the highest annual increase in suicide rates were Sikkim (increase by 3.3; 10.07% increase), Mizoram (increase by 2.2; 36.72% increase), Andhra Pradesh (increase by 1.5; 11.83% increase), Kerala (increase by 1.4; 5.76% increase), and Odisha (increase by 0.9; 8.89% increase).

3.4. Associations with COVID-19 Case Load and Deaths

For bivariable regression conducted between COVID-19 cases per 100 people and average annual change in suicide rates by state/UT from 2019 to 2022, there a statistical correlation (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.581; p<0.001; 95% CI: 0.297, 0.771). For bivariable regression, there was no statistical correlation between COVID-19 deaths per 10,000 people and average annual change in suicide rates (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.101; p = .577; 95% CI: -0.251, 0.429). Multi-linear regression was next conducted, and it was shown that the annual suicide rate changes were not associated with COVID-19 deaths per 10,000 people (standardized beta coefficient = 0.077; t = 0.523; p = 0.605) but was associated with COVID cases per 100 people (standardized beta coefficient = 0.578; t = 3.904; p<0.001).

4. Discussion

In this study, it has been demonstrated that there has been a major rise in suicide mortality across Bharat since the emergence of COVID-19. While the rise in total suicide deaths and suicide rates was occurring prior to the start of the pandemic, our analysis has demonstrated that these rises have accelerated since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. These trends regarding disease control differ from those for major conditions in Bharat, such as HIV and tuberculosis [X.Y]. Overall, these findings demonstrate that there is a clear need for more research to be conducted in order to understand the many factors that have contributed to these rises in suicide mortality. Of note, in a number of states, the rate of suicide has instead decreased since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and Haryana, both was notable decrease in suicide rates between the years 2019 and 2022. More research should be conducted in these contexts to aim to understand the factors that led to these decreases. Such findings may offer utility in efforts to reduce suicide rates throughout Bharat.

The trends of rising suicide in Bharat also demonstrate also point out a larger need to focus on upstream factors that contribute to poor mental health outcomes and mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety in Bharat. During the pandemic, aside from those pertaining to suicide, it has been shown that mental health outcomes have worsened across Bharat [

15]. There is hence a need for more research to determine how mental health morbidities can be improved across the country. Connected to this point, these findings indicate a clear need for more allocation of funding towards mental health care as part of government initiatives. Access to more psychiatrists in the nation is clearly needed, as the country currently only has approximately 0.30 psychiatrists per 100,000 population [z]. Increased funding for mental health supports should also involve a focus to improve access to counselling, while also working to improve traditional approaches and fostering protective factors. For example, it has been shown traditional healers have a valuable role in providing mental health support in certain regions, and there may be notable benefits in improving integration of such healers into health and medical systems [zz].

An additional crucial finding from our analyses has been that pertaining to the link between COVID-19 caseload in certain geographic regions with changes in suicide rates after the emergence of COVID-19. Importantly, it was found that COVID-19 deaths in the population was not associated with these rises in suicide rates – this may indicate that it is specifically those who survive from COVID-19 are at a higher risk of suicide. These findings may demonstrate a possible role of Long COVID leading to higher suicide rates in the country. While there are potentially confounding factors to this, these findings regarding long COVID may have important implications in explaining the extent of the long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. There is a need for further research on the biological basis for Long COVID causing all forms of mental health impacts, but especially suicide. Further research should also work towards focusing on providing tools for diagnosing Long COVID, providing a prognosis, and determining factors that increase risk of occurrence of this condition. Furthermore, there is a clear need to better understand the condition so that treatment regimens can be developed.

There are a number of limitations to this study that need to be considered. First of all, this was a study at the level of the nation and state; while these findings may provide important insights regarding trends on a large-scale, they do not provide thorough insights regarding the realities in local settings. Furthermore, it does not provide explanation regarding the geographic and health factors across these regions that may provide explanations regarding the differences in rates. An additional limitation is that, while this study does provide important insights regarding the potential role of long COVID in exacerbating suicide risk, the study does not provide answers as to the ways or reasons in which these occur; of note, there also may be an array of other confounding factors, such as impacts of quarantining measures, and loss of social connection during the pandemic, that may have had a role on suicide rates but were not able to be considered in our analysis. Regardless of these limitations, our study has provided important insights regarding the mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, and in potentially demonstrating the role that long COVID may have had in the rising rates of suicide across Bharat.

5. Conclusions

In our study, we have demonstrated that, with the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been major rises in suicide deaths and suicide at both a state and national level in Bharat. A particularly worrying aspects of these trends has been that this rise in suicide mortality has occurred at a rate that is faster than that prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study has also demonstrated that, as COVID-19 caseload has been associated with these changes in suicide mortality rates, there is potential for long COVID to have had an important role in contributing to overall suicidality across Bharat. These findings indicate an urgent need for improved mental health care and access across the country, whether this be with psychiatrists, counsellors or traditional healers. As well, there is a clear need for more research on the causes, risks, outcomes, and treatments of long COVID.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, KV, MAP; methodology, KV; analysis, KV, data curation, KV writing—original draft preparation, KV, MAP, writing—review and editing, KV, MAP. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Suicide [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024 Jun 7]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide.

- Chan YY, Lim KH, Teh CH, Kee CC, Ghazali SM, Lim KK, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with suicidal ideation among adolescents in Malaysia. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2016, 30, 20160053. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27508957/ (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- Nandini, N.; Chaube, N.; Dahiya, M.S. Psychological review of suicide stories of celebrities: The distress behind contentment. IJHW. 2018, 9, 280–285. Available online: https://scholars.okstate.edu/en/publications/psychological-review-of-suicide-stories-of-celebrities-the-distre (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- Suokas, J. , Suominen, K., Isometsä, E., Ostamo, A., & Lönnqvist, J. Long-term risk factors for suicide mortality after attempted suicide-Findings of a 14-year follow-up study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2001, 104, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beautrais, A. L. Risk factors for suicide and attempted suicide among young people. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 2000, 34, 420–436. [Google Scholar]

- Conwell, Y. , Duberstein, P. R., & Caine, E. D. Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biological psychiatry 2002, 52, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vijayakumar, L. , Chandra, P. S., Kumar, M. S., Pathare, S., Banerjee, D., Goswami, T., & Dandona, R. The national suicide prevention strategy in India: context and considerations for urgent action. The Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 160–168. [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnan, R.; Andrade, C. Suicide: An Indian perspective. Indian J Psychiatry. 2012, 54, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Senapati, R. E. , Jena, S., Parida, J., Panda, A., Patra, P. K., Pati, S.,... & Acharya, S. K. The patterns, trends and major risk factors of suicide among Indian adolescents–a scoping review. BMC psychiatry 2024, 24, 35. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Number of COVID-19 deaths reported to WHO (cumulative total). WHO. [Internet]. Available from: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/deaths?n=o.

- Salvatore, M.; Basu, D.; Ray, D.; Kleinsasser, M.; Purkayastha, S.; Bhattacharyya, R.; Mukherjee, B. Comprehensive public health evaluation of lockdown as a non-pharmaceutical intervention on COVID-19 spread in India: national trends masking state-level variations. BMJ open. 2020, 10, e041778. Available online: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/10/12/e041778.abstract 12 (accessed on 7 June 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The lancet. 2020, 395, 912–920. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-

6736(20)30460-8/fulltext?cid=in%3Adisplay%3Alfhtn0&dclid=CNKCgb7nle0CFVUkjwodG0YCkg. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamun MA, Griffiths MD. PTSD-related suicide six years after the Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh. Psychiatry research. 2019. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31685284/.

- COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021, 398, 1700–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mani, V.E.; Kumar, R.; Srivastava, A.K.; Sarkar, Z.; Babu, G.N.; Tandon, R.; Paliwal, V.K.; Jha, S. The Psychosocial Impact of COVID-19 on an Adult Indian Population. Cureus. 2023, 15, e38504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National comprehensive guidelines for management of post Covid sequelae [internet]. [cited 2024 ]. Government of India. Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/NationalComprehensiveGuidelinesforManagementofPostCovidSequelae.pdf.

- Taquet M, Geddes JR, Husain M, Luciano S, Harrison PJ. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2021, 8, 416–427. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpsy/article/PIIS2215-03662100084-5/fulltext. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins V, Sohaei D, Diamandis EP, Prassas I. COVID-19: from an acute to chronic disease? Potential long-term health consequences. Critical reviews in clinical laboratory sciences. 2021, 58, 297–310. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10408363.2020.1860895 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anaya, J.M.; Rojas, M.; Salinas, M.L.; Rodríguez, Y.; Roa, G.; Lozano, M.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, M.; Montoya, N.; Zapata, E.; Monsalve, D.M.; Acosta-Ampudia, Y. Post-COVID syndrome. A case series and comprehensive review. Autoimmunity reviews. 2021, 20, 102947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhry, D.; Khandelwal, S.; Bahadur, C.; Daniels, B.; Bhattacharyya, M.; Gangakhedkar, R.; Desai, S.; Das, J.; Gupta, U.; Singh, V.; Garg, S. Prevalence of long COVID symptoms in Haryana, India: a cross-sectional follow-up study. The Lancet Regional Health-Southeast Asia. 2024, 25. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lansea/article/PIIS2772-3682(24)00045-3/fulltext.

- Arjun, M.C.; Singh, A.K.; Roy, P.; Ravichandran, M.; Mandal, S.; Pal, D.; Das, K.; Gajjala, A.; Venkateshan, M.; Mishra, B.; Patro, B.K. Long COVID following Omicron wave in Eastern India—A retrospective cohort study. Journal of medical virology. 2023, 95, e28214. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/jmv.28214 (accessed on 7 June 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). Accidental Deaths & Suicides in India (ADSI) – 2018. Government of India. Accessed on 11 Sept 2024. Available from: https://www.data.gov.in/catalog/accidental-deaths-suicides-india-adsi-2018?page=3.

- National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). Accidental Deaths & Suicides in India (ADSI) – 2019. Government of India. Accessed on 11 Sept 2024. Available from: https://www.data.gov.in/catalog/accidental-deaths-suicides-india-adsi-2019.

- National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). Accidental Deaths & Suicides in India (ADSI) – 2020. Government of India. Accessed on 11 Sept 2024. Available from: https://www.data.gov.in/catalog/accidental-deaths-suicides-india-adsi-2020.

- National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). Accidental Deaths & Suicides in India (ADSI) – 2021. Government of India. Accessed on 11 Sept 2024. Available from: https://www.data.gov.in/catalog/accidental-deaths-suicides-india-adsi-2021.

- National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). Accidental Deaths & Suicides in India (ADSI) – 2022. Government of India. Accessed on 11 Sept 2024. Available from: https://www.data.gov.in/catalog/accidental-deaths-suicides-india-adsi-2022.

- MOHFW. COVID-19 Dashboard. Government of India. COVID-19. Accessed on 11 Sept 2024. Retrieved from: https://covid19dashboard.mohfw.gov.in/.

- IBM Corp; ‘IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version XX (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y, USA.

- Varshney, K.; Patel, H.; Kamal, S. Trends in Tuberculosis Mortality Across India: Improvements Despite the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cureus. 2023, 15, e38313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Varshney, K.; Mustafa, A.D. Trends in HIV incidence and mortality across Bharat (India) after the emergence of COVID-19. International Journal of STD & AIDS 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, K. , Kumar, C. N., & Chandra, P. S. Number of psychiatrists in India: Baby steps forward, but a long way to go. Indian journal of psychiatry 2019, 61, 104–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Longkumer, N. (2020). Traditional healing practices and perspectives of mental health in Nagaland. https://repository.tribal.gov.in/handle/123456789/74195.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).