Submitted:

15 September 2024

Posted:

17 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Participant Inclusion Criteria, Identification, and Recruitment:

The ACB Reduction Intervention

Data Collection and Management:

3. Results

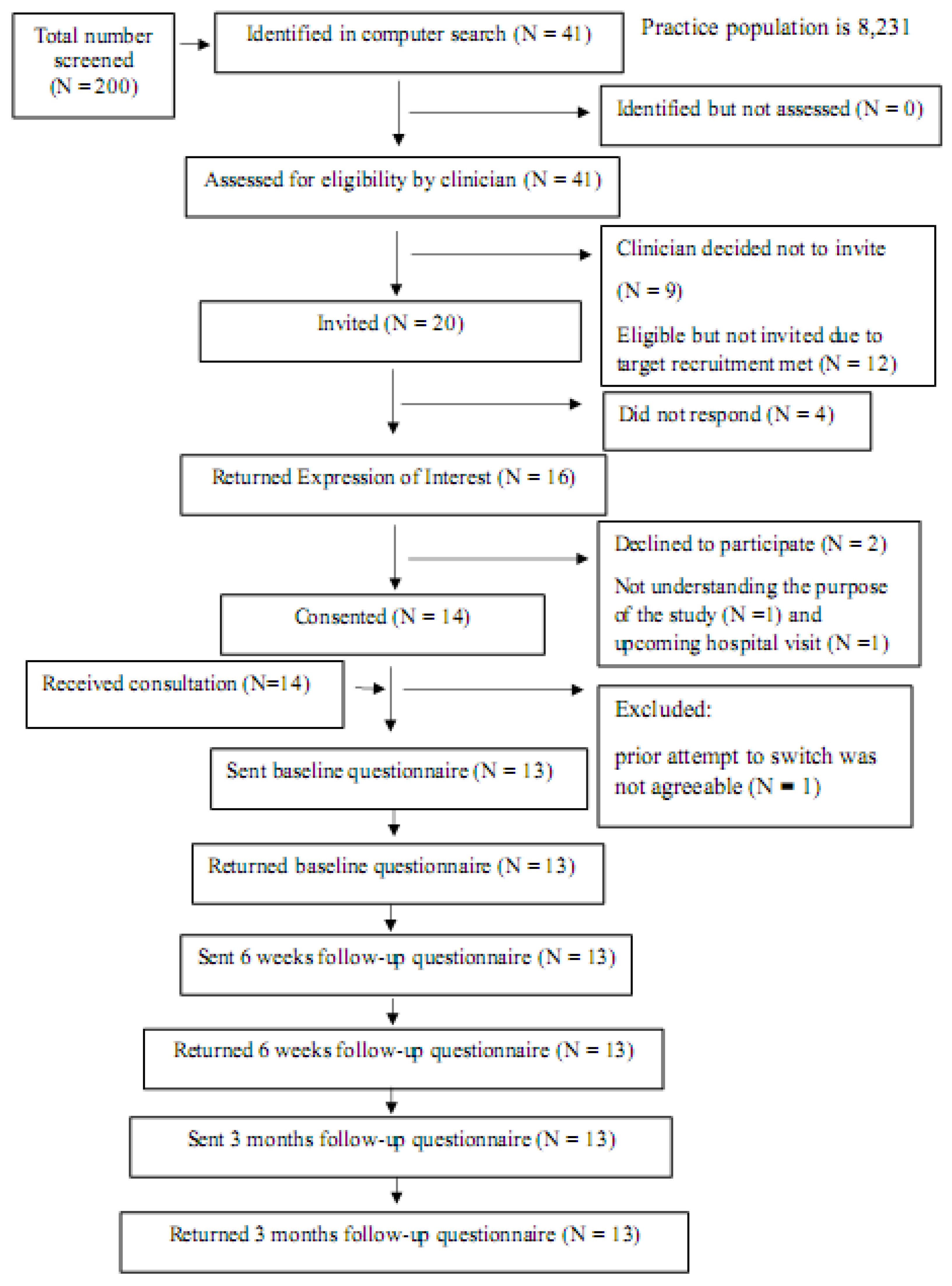

Patient Identification, Recruitment and Retention

Participant Demography, Outcomes and Experiences of Intervention

| Participant ID | Gender |

Age (years) |

ACoB score Baseline |

ACoB score 6 weeks |

ACoB score 12 weeks |

Old treatment | New treatment | Sustainability |

| P1 | Male | 72 | 3 | 0 | 0 | Amitriptyline 25mg tablets one at night | Pregabalin 50mg capsules one three times daily | Patient remained on new medication |

| P2 | Male | 75 | 3 | 0 | 0 | Hydroxyzine hydrochloride 10mg tablets one at night | Fexofenadine 180mg tablets one at night and added an emollient-Zerobase to see if helps itch | Patient remained on new medication |

| P3 | Male | 73 | 3 | 0 | 0 | Tolterodine 2mg capsules one daily | Mirabegron 25mg tablets one daily | No improvement on 25mg dose so increased to 50mg and then remained on new medication |

| P4 | Female | 69 | 3 | 0 | 0 | Solifenacin 5mg tablets one daily | Mirabegron tablets 50mg one daily | Patient remained on new medication |

| P5 | Male | 77 | 3 | 0 | 0 | Chlorphenamine 4mg tablets | Fexofenadine 180mg tablets one daily | Patient remained on new medication |

| Participant ID | Gender |

Age (years) |

ACoB score Baseline |

ACoB score 6 weeks |

ACoB score 12 weeks |

Old treatment | New treatment | Sustainability |

| P7 | Male | 67 | 6 | 1 | 1 | Cetirizine 10mg tablets Amitriptyline 10mg tablets |

Fexofenadine 180mg tablets one daily Pregabalin capsules 75mg one twice daily |

Patient remained on new medication but with pregabalin increased to 150mg twice daily |

| P8 | Female | 70 | 4 | 1 | 1 | Amitriptyline 10mg tablets three at night Co-codamol 30/500 tablets |

Reduce dosage to 20mg over the next 2 weeks with a view to stopping altogether Naproxen 500mg tablets one twice daily |

The patient has stopped completely with no adverse effects The patient was managing with naproxen but due to struggling to sleep at night started taking occasional co-codamol |

| Participant ID | Gender |

Age (years) |

ACoB score Baseline |

ACoB score 6 weeks |

ACoB score 12 weeks |

Old treatment | New treatment | Sustainability |

| P9 | Male | 68 | 6 | 3 | 3 | Chlorphenamine 4mg tablets one three times daily Cetirizine 10mg tablets once daily Amitriptyline 10mg one at night |

All previous medications stopped. Replaced by fexofenadine 180mg tablets once daily | The patient was still not sleeping well. -chlorphenamine 4mg tablets once at night added back Otherwise, patient remained on new medication with no adverse effects |

| Participant ID | Gender |

Age (years) |

ACoB score Baseline |

ACoB score 6 weeks |

ACoB score 12 weeks |

Old treatment | New treatment | Sustainability |

| P10 | Male | 76 | 6 | 1 | 4 | Solifenacin 5mg tablets Nefopam 30mg tablets Co-codamol 30/500mg tablets |

Mirabegron 50mg one daily Reduce dose of nefopam if able and replace with increasing dose of co-codamol, to a regular four times daily as opposed to when required |

Mirabegron did not help urinary urgency at all. Stopped and reverted back to solifenacin but higher dose Patient stopped taking nefopam completely after increase in dosage of co-codamol |

| P11 | Female | 66 | 6 | 0 | 0 | Hyoscine butylbromide 10mg tablets Hydroxyzine 10mg tablets |

Mebeverine 135mg tablets one three times daily Peppermint oil capsules 0.2ml one three times daily Fexofenadine 180mg tablets one daily |

Patient remained on new medication |

| Participant ID | Gender |

Age (years) |

ACoB score Baseline |

ACoB score 6 weeks |

ACoB score 12 weeks |

Old treatment | New treatment | Sustainability |

| P12 | Male | 71 | 3 | 3 | 3 | Amitriptyline 50mg tablets | Amitriptyline 30mg tablets Mirtazapine 15mg tablets |

Currently taking 35mg amitriptyline as at lower dose sleep was disturbed Patient remained on new medication |

| P13 | Female | 75 | 6 | 0 | 0 | Solifenacin 5mg tablets Dicycloverine 10mg tablets |

Mirabegron 50mg tablets Peppermint capsules /mebeverine 135mg tablets |

The patient remained on the new medication |

| P14 | Male | 79 | 3 | 0 | 0 | Solifenacin 5mg tablets two times daily | Mirabegron 50mg tablets | The patient remained on new medication |

| Items | Baseline (median; IQR) |

6 weeks follow up (median; IQR) |

12 weeks follow up (median; IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Problems in mobility | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 2.75) | 1.50 (1, 3.25) |

| Problems in self-care | 1 (1, 1) | 1 (1, 1) | 1 (1, 1.5) |

| Problems in usually activities | 2 (2, 2.50) | 1 (1, 2.75) | 1 (1, 3.25) |

| Pain/Discomfort | 2 (1.50, 3.50) | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 3.25) |

| Anxiety/Depression | 1 (1, 2) | 2 (1, 2) | 1 (1, 2) |

| Themes | Subthemes/exemplar quotes |

|---|---|

| Remembering the purpose of the study | Patients remembered the purpose of the study, i.e., was involved in medication changes in people aged 65 year and over to new medication to reduce side effects and improve quality of life. It was about trying to find out whether the medication that was routinely given to elderly people was still doing the best job. [P8, female,70y] Well, it was about my medication and I got my medication changed, that’s what it was about. [P4, female, 70y] |

| Process of the study |

What went well: Many patients suggested the process of study went well. They were happy about the medication changes and satisfied with the pharmacist consultation. They kept in touch with the pharmacist when they needed further help or had problems about medication usage. Well, it’s fine, I’m on new medication and it seems to be working out fine. The pharmacy has been in touch with me a couple of times and all’s well. [P4, female, 69y] Maybe … yes, just consultation or just touching base with the pharmacist, the pharmacist was good, and she did keep in touch but probably it would’ve been better to keep in touch just a little bit more, I think. But equally well I could have contacted her, she was available to be contacted so it wasn’t really a problem. [P8, female, 70y] The pharmacist noted that patients were happy with the information pack that explained them clearly and also additional telephone call from the pharmacist. The ones we picked were very positive about it, they were very interested. They appreciated the pack that you sent out with all that information which explained everything to them very clearly, although I had gone over very quickly the basics on the telephone. The fact that it was anonymous was good, they liked that idea. [Primary care pharmacist] The pharmacist was happy to conduct the research in her role. Patients felt positive about pharmacists’ involvement in this type of study. GP also valued the pharmacist’s opinion as he was not required to provide further input towards the plan and no patients complaint about the changes or anything else. It was very good, I enjoyed doing it. The patients were very positive,…[Primary care pharmacist] Pharmacist team manage this, and I was not involved as they found no issues requiring GP input [GP] |

|

What did not go so well: A few patients were excluded from the study because they were waiting for hospital admissions for procedures and pharmacist felt that timing was not right to make any changes due to their upcoming appointments. One or two of them I think we decided weren’t eligible because of the other drugs they were on, or they were awaiting a procedure at the hospital, and we didn’t want to change anything before they went on for that. That was quite a valid criticism. It’s just circumstances really. [Primary care pharmacist] The pharmacist suggested the monitoring paperwork was burdensome due to time consuming process and did not really fit to routine practice. She felt that six weeks is too long to monitor patients following medication changes. I think part of your paperwork it said three months review, six weeks review; those didn’t really fit what I was doing. Six weeks was too long to leave them, I was phoning them maybe two weeks, three weeks, or they were phoning me and saying it wasn’t going well. A shorter timeline for the initial review would be better. [Primary care pharmacist] | |

|

Difficulties in taking part in the study: One patient thought the questionnaires were quite repetitive due to similar questions asked in each follow-up time. It could be that he misunderstood the quality-of-life monitoring in the long period. However, Others suggested no difficulties in taking part in the study at all. Actually, found the questionnaires that you sent were quite repetitive. You were asking the same information. That’s really about all, you know, I can say. I filled in several questionnaires, and I seemed to be answering the same questions. [P2, Male, 75y] Not physically or anything. No, I was … as far as I can remember there were no difficulties in it at all. [P7, male, 67y] | |

| Patient-related outcomes |

General satisfaction and well being In general, patients were satisfied with the pharmacist consultation and were happy with medication changes that reduced their side effects of the medication. Well, it’s fine, I’m on new medication and it seems to be working out fine. The pharmacy has been in touch with me a couple of times and all’s well. [P4, female, 69y] When we first changed from my medication in the beginning, it was fine in that it helped me to sleep better, which was one of my big problems. After a while, the benefits seemed to wear off a bit and then my medication as changed again, which now suits me much better in all directions. It helps me to sleep better and it … yeah, yeah, the side effects, the constipation side effects if you like have gone. So that’s fine. [P8, female, 70y] |

|

Symptom control and side effects: Overall symptoms could be controlled better after medication changes. Patients were happy with a new medication or the alternatives that had fewer side effects. Well, yes, I kind of did wonder how’s this going to work? But you know this; I was happy to change to something else because I knew I wasn’t feeling great with the Buscopan. I know it does help for bloating and that, but I know when the lady said, “Take peppermint oil, I’ll try you with that”, I know peppermint is good for the stomach anyway. No, I was – the way I was feeling, Toney, I just wanted to try a change and see if it made a difference. [P11, female, 66y] Well, I’m not getting the same bloating the same. I do have IBS so I’ll always have that problem, but no, my tummy feels more comfortable from day to day. I’m quite happy to stick with that just now, yes. [P11, female, 66y] Yeah, for me it worked fine because my medication as changed. Now, I’m on something that suits me better with less sort of side effects… No, just … nothing worse, just better, just the symptoms were slightly better. [P8, female, 70y] | |

| Suggestions for improving in the future study | Patients valued regular review of medications and believed that it is quite important and needed. Just a review, a regular review of the medication that you’re on and what it’s still doing rather than just assuming that everything is fine, and it continues to be fine. [P8, female, 70y] The pharmacists suggested that the recruitment process could be improved in the definitive study. I suppose that cut out a certain amount of the population which is a shame in a way because some of the other people we might have been able to help more, but it would’ve meant going through their family, and I felt because it was a pilot, that perhaps that was a step too far on this occasion. Perhaps when you’re doing the full study you could consider people like that, but we would need to involve families and that just makes it more complicated. [Primary care pharmacist]Pharmacist also suggested paperwork needed to be improved to fit routine practice in the future direction. In addition, the initial monitoring period may need to be shortened to 2 weeks for close follow-up. The information pack was felt to be appropriate for use in the definitive trial. I think part of your paperwork it said three months review, six weeks review; those didn’t really fit what I was doing. Six weeks was too long to leave them, I was phoning them maybe two weeks, three weeks, or they were phoning me and saying it wasn’t going well. A shorter timeline for the initial review would be better. [Primary care pharmacist] Well, I think your paperwork could be slightly better, I found it a bit confusing you know, where to put things. I mean other than that, not really, no because I think your explanation package was very good, the education stuff that you sent me, the examples of what to change, you could have more of that, you could expand that list I think, to help people. [Primary care pharmacist] The pharmacists also suggested that well qualified and experienced pharmacists may be best suited for conducting the definitive trial or when its rolled out into practice to avoid confusions and complications related to authorisations and mistakes. The trust of GPs for experienced pharmacists is quite important as study did not need input form GPs. I think that to some extent depends on how experienced the pharmacist is and where their place in the team is. If you were a newly qualified pharmacist, you’d just arrived, you didn’t know anybody, you didn’t know the doctors, I think it would be more difficult. I would imagine if you’re going to roll this out, say somebody is going to do research like this, you would want to go for pharmacists who are well established and almost certainly have to be prescribers so that they can just get going, otherwise you’ve got that interface between the pharmacist, the patient and the doctor or the nurse and that just complicates the whole picture quite honestly. [Primary care pharmacist] |

| Willing to take part in a future trial | All patients, a primary care pharmacist and a GP expressed their interests to take part in future definitive trial. |

| Experiences in a training session for a pharmacist | The pharmacist expressed the important and value of the training session and its contents were quite important and extremely useful for her. In particular, it provided specific example of an alternative which made the decision-making process easier. Extremely useful. I think I would’ve struggled with the time constraints that I had to actually achieve as much as we did. It was very useful to have specific examples of what one drug could be changed to and the reason for that, it just made it easier for me just to go ahead and do things as opposed to having to think about it. If I had to work it all out for myself, it would’ve taken me longer and again, we’re back to time. [Primary care pharmacist Yes, yes, because the training gave you specific examples of what you could do, so we tended to search on the drugs that we knew we had a very simple, straightforward alternative to. That made the process, the decision-making process easier, I think. [Primary care pharmacist] |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization, 2021-last update, Ageing and health. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health [12/August, 2021].

- Maher, R.L., Hanlon, J.T. and Hajjar, E.R., 2014. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety, 2014, 13(1), pp. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Katzenschlager, R., Sampaio, C., Costa, J. and Lees, A. Anticholinergics for symptomatic management of Parkinson´s disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2022, (3), pp. 1-19. [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.L., Gnjidic, D., Nahas, R., Bell, J.S. and Hilmer, S.N. Anticholinergic burden: Considerations for older adults. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research, 2017 47(1), pp. 67-77. [CrossRef]

- Vardanyan, R.S. and Hruby, V.J. Anticholinergic drugs. In: R.S. VARDANYAN and V.J. HRUBY, eds, Synthesis of essential drugs, 2006. Elsevier, pp. 195-208.

- Rudolph, J.L., Salow, M.J., Anglini, M.C. and Mcglinchey, R.E. The anticholinergic risk scale and anticholinergic adverse effects in older persons. Arch Intern Med, 2008, 168(5), pp. 508-513. [CrossRef]

- Ancelin, M.L., Artero, S., Portet, F., Dupuy, A., Touchon, J. and Ritchie, K. Non-degenerative mild cognitive impairment in elderly people and use of anticholinergic drugs: longitudinal cohort study. British Medical Journal, 2006, 332, pp. 455-459. [CrossRef]

- Ehrt, U., Broich, K. and Larsen, J.P. Use of drugs with anticholinergic effect and impact on cognition in Parkinson’s disease: A cohort study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 2010, 81, pp. 160-165.

- Kersten, H. and Wyller, T.B. Anticholinergic drug burden in older people’s brain - how well is it measured? Basic & clinical pharmacology & toxicology, 2014, 114(2), pp. 151-9.

- Ablett, A.D., Wood, A.D., BarrA, R., Guillot, J., Black, A.J., Macdonald, H.M., Reid, D.M. and Myint, P.K. A high anticholinergic burden is associated with a history of falls in the previous year in middle-aged women: findings from the Aberdeen prospective osteoporosis screening study. Annals of Epidemiology, 2018, 28, pp. 557-562. [CrossRef]

- Nakham, A., Myint, P.K., Bond, C.M., Newlands, R., Loke, Y.K. and Cruickshank, M. Interventions to reduce anticholinergic burden in adults aged 65 and older: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 2020, 21(2), pp. 170-180. [CrossRef]

- Krishnaswami, A., Steinman A. M., Goyal, P., Zullo, R.A., Anderson, S.T., Birtcher, K.K., Goodlin, J.S., Maurer, S.M., Alexander, P.K., Rich, W.M. and Tjia, J. Deprescribing in older adults with cardiovascular disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2019, 73(20), pp. 2584-2595.

- Michael, S. and Reeve, E. Deprescribing. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/deprescribing#:~:text=Common%20goals%20for%20deprescribing%20include,to%20improving%20quality%20of%20life. edn. UpToDate, 2022.

- Olasehinde-Williams, O., July, 2020-last update, Deprescribing guide, 2020. Available: https://southendccg.nhs.uk/your-health-services/healthcare-professionals/medicines-management/medicines-management-resources/2308-deprescribing-guide/file [April/03, 2020].

- Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I. and Petticrew, M., 2019-last update, Developing and evaluating complex interventions: Following considerable development in the field since 2006, MRC and NIHR have jointly commissioned an update of this guidance to be published in 2019. Available: https://mrc.ukri.org/documents/pdf/complex-interventions-guidance/ [05/01, 2021].

- Stewart, C., Gallacher, K., Nakham, A., Cruickshank, M., Newlands, R., Bond, C., Myint, P.K., Bhattacharya, D. and Mair, F.S. Barriers and facilitators to reducing anticholinergic burden: a qualitative systematic review. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 2021, 43, pp. 1451-1460. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, Y., Wood, C., Stewart, C., Nakham, A., Newlands, R., Gallacher, K.I., Quinn, T.J., Ellis, G., Lowrie, R., Myint, P.K., Bond, C. and Mair, F.M. Understanding Stakeholder Views Regarding the Design of an Intervention Trial to Reduce Anticholinergic Burden: A Qualitative Study. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 2021, 12, pp. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Boustani, M., Campbell, N., Munger, S., Maidment, I. and Fox, C. Impact of anticholinergics on the aging brain: A review and practical application. Aging Health, 2008, 4(3), pp. 311-320. [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, H., Bond, C.M., Elliott, A.M. Pharmacist led management of chronic pain in primary care: results from a randomised controlled exploratory trial. BMJ Open, 2013, 3:e002361. [CrossRef]

- Wickware, C. When will England get a ’Pharmacy First’ service? The Pharmaceutical Journal, 2023, 310(7969). [CrossRef]

- Okeowo, D.A., Zaidi, S.T.R., Fylan, B. and Alldred, D.P. Barriers and facilitators of implementing proactive deprescribing within primary care: a systematic review. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice, 2023, 31(2), pp.126-152. [CrossRef]

- Kua, C., Mak, V.S.L. and Lee, S.W.H. Health Outcomes of Deprescribing Interventions among older residents in nursing homes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 2019, 20(3), pp. 362-372. [CrossRef]

- Thillainadesan, J., Gnjidic, D., Green, S. and Hilmer, S.N. Impact of deprescribing interventions in older hospitalised patients on prescribing and clinical outcomes: a systematic review of randomised trials. Drugs Aging, 2018, 35(4), pp. 303-319.

- Ulley, J., Harrop, D., Ali, Ali, Alton, S. and Davis, S.F. Deprescribing interventions and their impact on medication adherence in community-dwelling older adults with polypharmacy: a systematic review. BMC Geriatrics, 2019, 19(15), pp. 1-13. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | N* |

|---|---|

| • Males • Females |

8 5 |

| Age in years • 65-69 • 70-74 • 75-79 |

3 5 5 |

| Number of medications (mean ±SD) | 7.62 (±3.18) |

| Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden score • 3 • 4 • 6 |

7 1 5 |

| The median time (IQR) for the initial consultation with the primary care pharmacist | 15 minutes (12.5- 20 minutes). |

| Items | Baseline (median; IQR) | 6 weeks follow up (median; IQR) | 12 weeks follow up (median; IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| The pharmacist appeared well informed | 5 (4, 5) | - | - |

| The pharmacist listened to what I had to say | 5 (4, 5) | - | - |

| The pharmacist answered all my concerns | 5 (4, 5) | - | - |

| I would rather have seen a doctor | 3 (2 ,3) | - | - |

| I would rather have seen a nurse | 3 (2,3) | - | - |

| Happy with my consultation with the pharmacist | 5 (4, 5) | - | - |

| Good idea to change medication to reduce chance of unwanted side effects | 5 (4.50, 5) | - | - |

| The study purpose was clear. | 5 (4, 5) | - | - |

| Given enough information to decide whether to participate. | 5 (4, 5) | - | - |

| The new approach to your medication | |||

| Happy to discuss medicines with the pharmacist. | - | 5 (4, 5) | 5 (4, 5) |

| The symptoms of illness are controlled | - | 3 (2, 4) | 4 (4, 5) |

| No concerns related to new approach for reviewing medicines | - | 4 (4,5) | 4 (4,5) |

| Happy with the changes made to my medicines | - | 4 (3, 4.50) | 3 (3, 5) |

| Unhappy with the changes made to medicines | - | 3 (2, 3) | 3 (3,3) |

| Currently on a new medication | - | 4 (3, 5) | 4 (3, 4) |

| Changed back to my old medicines | - | 3 (2, 3) | 2 (2, 3) |

| About the study processes | |||

| The questionnaires were clear | - | - | 5 (4, 5) |

| The questionnaires were easy to complete | - | - | 5 (4, 5) |

| Happy to complete the questionnaires | - | - | 5 (4, 5) |

| Study participation did not take up too much time | - | - | 5 (4, 5) |

| Study participation did not give any stress | - | - | 5 (4, 5) |

| Consider participating in a future study examining similar issues | - | - | 5 (4, 5) |

| Recommend a friend to take part in this kind of study | - | - | 5 (3, 5) |

| Interested in being part of a patient advisory group for future studies | - | - | 3 (2, 5) |

| Further study should be encouraged in this area | - | - | 5 (4, 5) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).