1. Introduction

Achieving environmental, economic and social sustainability is by now an established research theme. Since its original definition proposed by the Brundtland Commission in the Report “Our Common Future”, the meaning of Sustainable Development is fulfilment of the needs of the current generation while preserving the capacity of future generations to meet their own needs [

1]. It is also widely accepted that the quality of life does not consist only of the monetary sphere but includes other dimensions, such as environment, health, education, safety, that enable people to lead a dignified life and realize their aspirations [

2]. In urban areas, uneven distribution of resources generate inequalities and poverty which often are most evident in the peripheries, places not necessarily confined to the physical margins of the urban area, but where various unfavourable factors accumulate, contributing to the difficult socio-economic conditions of households: poor presence of institutions, low quality of services, inefficiency of public transportation isolation form the rest of the city, lack of social relationships and participation to public life. However, the centrality of urban areas in modern national economic systems and globally, is evident since people keep moving towards cities, attracted by the wealth creation, cultural and institutional activities. A growing and positive trend in the urban population share is estimated for 2050, when it will reach about 68% of the world's one [

3]. Since the Second Industrial Revolution, began in 1870s, migratory flows, caused by the innovations introduced in farming methods, represented a moment of change for cities. Due to the excess of labour in the agricultural sector, and the rapid industrialisation process fuelled by the technological progress, the phenomenon of urbanism spread quickly and the cities, characterised by greater opportunities for employment and enrichment, became larger and more populated [

4].

Given the importance of cities in the contemporary era, it is necessary to think about their development according to what is shared internationally with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development with “Goal 11: Sustainable cities and communities”, where a vision of inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable cities and human settlements is affirmed, through the fight against poverty and inequalities, with a view characterised by integrated planning with the surrounding territories and equitable access to basic services for the benefit of all residents [

5]. The 15-minute city can be easily framed in an SD context, proposing a human-centred urban development with ecology, proximity, solidarity and participation as fundamental principles [

6]. In this paper, we explore the Proximity to urban services, which is one of the principles of the 15-minute city on which the citizens quality of life depends [

7]. We analyse the municipal territory of Rome, whose neighbourhoods are characterised by a strong diversity in terms of urban characteristics and aesthetics and socioeconomic composition [

8].

The paper is organized as follows: section two describes the evolution of the 15-minute city concept; section three explores the concept of Proximity to urban services; section four describes the study area; section five illustrates the methodology; section six discusses the results and section seven contains some final remarks.

2. 15-Minute City: Concept Evolution

The concept of the 15-minute city began to gain worldwide notoriety in 2020 when the Mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, decided to undertake a true proximity revolution with the collaboration of urban planner Carlos Moreno, creator of the 15-minute city concept. The idea was quite simple in some ways: a model of sustainable urban development that placed the human being at the centre of city planning, embracing the notion of Chrono-Urbanism, which emphasizes the importance of considering the space-time dimension. [

6]. The 15-minute city should enable every resident to meet their essential needs within 15 minutes from their home through active transportation means (walking, cycling) [9, 10]

In recent years, the consequences of the economic and social crisis linked to the COVID-19 pandemic have further fuelled the public debate on sustainable cities and the proximity of services in a context of mobility strongly influenced by remote work. The 15-minute city model quickly became the focal point of new urban policies, bursting onto the political scene through campaigns for municipal elections in several major cities.

The 15-minute city model stands out in clear opposition to Le Corbusier's Athens Charter (1933), which has been the foundation for urban development over the past ninety years. The Athens Charter introduced the principle of "zoning", proposing a very rigid division of urban areas, each with a specific function: working and producing, living, recreation, and so on. In contrast to this idea, the 15-minute city envisions reduced distances for shorter commutes: an inclusive transformation that places people and their needs at the centre [9, 10, 11]. But the roots of the 15-minute city model are well established in the past and there are several precursors who anticipated some of its elements, as E. Howard that gave attention to green urban planning to approach the problem of overcrowding. The idea of the Garden City conceived in 1898, combined the advantages of the city with those of the countryside, envisaging a system of autonomous satellite cities connected to the central one [

12]. In 1929, C. Perry introduced the concept of the Neighbourhood Unit, the element that regulated the spatial organisation of the city, the basic structural unit for urban development: each Neighbourhood Unit was to be equipped with the necessary urban amenities such as schools, retail services, community centres, green areas and public spaces [

13]. In 1961, J. Jacobs published “The Death and Life of Great American Cities”, where the idea of proximity was explained as the vital ingredient of cities to allow people exchanging ideas, goods, beliefs and knowledge, generating diversity [

14]. During the 1980s and the early 1990s, the New Urbanism proposed compact developments featuring mixed uses, integrating various housing types and encouraging sustainable transportation options to achieve human-scale neighbourhoods [

15]. Transit Oriented Development, grown in the 1990s with P. Calthorpe's “The next American metropolis”, proposed reorganising the area around public transport, seeking more pedestrianisation and more sustainable mobility with less private car use [

16]. Another inspiring idea was the “Metapolis” of F. Ascher presented in his work “Métapolis: ou l'avenir dês villes” where he argued that urban areas operate as a connected network, facilitated by transportation and telecommunication systems [

17]. One more precursor is the New Pedestrianism of M. E. Arth (1999), a branch of New Urbanism characterised by a more ecological and pedestrian orientation [

18]. Another notably contribution comes from J. Lerner, urban planner and former Mayor of Curitiba and Governor of Paraná State. In 2003, Lerner published "Urban Acupuncture", emphasizing the importance of public ownership of urban spaces and the value of small projects that can be implemented quickly, thereby creating chain effects and, in 2010, Marco Casagrande undertook a similar work, highlighting the critical role of community involvement in contrast to large-scale urban renewal initiatives [19, 20].

But the concept of the 15-minute city has now transcended mere academic boundaries, becoming a central element of city agendas. In this regard, the work of C40 (a network of the world's cities committed to addressing climate change) is important and has produced the C40 Mayors' Agenda for a Green and Just Recovery, an act that emphasised the need to create the conditions for inclusive and equitable cities with a view to environmentally healthy living and good citizen services [21, 22]. Many cities have now implemented policies aimed at achieving the goals set by the 15-minute city concept even in different forms around the world [

23]. Another important role is covered by UN-Habitat which advocated for proximity as a sustainable development factor in the “New Urban Agenda”, a document subscribed by 193 countries in the frame of the United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development in Quito [24, 25]. Density, diversity, proximity and digitalisation are the pillars on which the functioning of the 15-minute city rests. With these ingredients, neighbourhoods do not provide specific activities, but offer all the services citizens need to lead a dignified life, places where every opportunity can be exploited, offering amenities where there are none, to include every social group, starting with the most marginalised and disadvantaged [6, 26]. In his model, C. Moreno considers that services belong to six “Urban Social Functions” (USF), categories including the necessary amenities to lead a dignified life in an urban context: caring, enjoying, learning, living, working and supplying. The USF services should be accessible within a 15-minute walking or cycling distance from home [

6].

3. Proximity to Urban Amenities, Inequality and Quality of Life

The 15-minute city model advocates for a sustainable urban development based on Proximity to urban services. Proximity is one of the principles governing the functioning and evolution of cities since the organisation of urban space and its components depends on it. In order to increase Proximity, barriers imposed on the movement of people and the exchange of goods, services and information must be overcome: the higher the Proximity level, the more factors of production are available for economic activities and the lower the costs of obtaining goods and services [

27]. With reference to the urban space, the possibility to use a certain service depends on the capacity to reach that service. This can be declined in terms of Proximity, understood both in the sense of distance travelled and time spent doing so, which is one of the mainstays of the 15-minute city, a fundamental aspect to contrast the growing inequalities and to improve the quality of life for everyone [28, 29].

Indeed, the geographical location of services and urban amenities can affect people's quality of life and well-being [30, 31, 32]. Proximity, together with the efficient use of resources, makes it possible to plan cities pursuing the objectives of sustainable urban development and reducing socio-spatial inequalities [

33].

Several studies already exist, focusing on the 15-minute city. An analysis conducted for Naples, considers geomorphological, physical and socioeconomic characteristics, to detect the parts of the urban area that can be defined according to the 15-minute city [

34]. Case-studies in Cagliari, Perugia, Pisa and Trieste assess urban systems' alignment with the 15-minute city concept focusing on reproducible and comparable indicators of density, proximity, diversity and service access [

35]. For an evaluation of the city of Vancouver, a cumulative opportunity measure is used to quantify the availability of grocery stores reachable within a 15-minute walking or cycling distance from residents' homes, accounting for varying travel speeds to assess proximity for different age groups of people [

36]. By dividing the territory of Rome into hexagonal zones with a diameter of 1250 meters, the distance from the centre of each zone to various services, classified into categories and subcategories, was calculated obtaining a service proximity indicator, with scores ranging from 100 to 20 (100 for distances within 500 meters, 80 within 1000 meters, 60 within 2000 meters, 40 within 4000 meters, and 20 beyond); these scores were then weighted and aggregated for each pillar on the basis of on the sustainability and importance of the services, prioritizing essential services [

37]. Another study compares Rome, London and Paris, by calculating pedestrian travel times to access services for all possible routes [

38]. On the city of Barcelona, utilizing cadastral parcels, the network analysis method is used for services and activities, according to the canons indicated by Moreno's model [

39]. The study in the city of Turin proposes a proximity analysis using three-time thresholds (5, 10 and 15 minute), considering the zones of the city and the percentage of the population [

40]. A 15-minute city index is proposed to understand the status of Hong Kong by fitting the proximity measured by the modified two-step floating catchment area method to categories related to the dimensions of living, health, education, public transit and entertainment [

41]. With the aim of being reproducible everywhere using global open data, the NExt ProXimity Index measures proximity on foot in the cities of Bologna and Ferrara representing the values on a local scale with hexagonal grids [

42]. A comparison in terms of 15-minute walking proximity between various European cities of at least 100,000 inhabitants is carried out by considering total destinations and types of opportunities as indicators, highlighting inter- and intra-city inequalities with the computation of pseudo-Gini coefficients [

43].

Since 2021, with the election of Roberto Gualtieri as Major of Rome, the Municipality is planning its urban development from the perspective of Moreno’s 15-minute city, conceiving Rome as a polycentric, accessible and sustainable city, in which citizens find an extensive network of neighbourhood services available at a maximum distance of 15 minutes, on foot and by bicycle [

44].

4. The ”Seven Cities” of Rome

Rome is the most populated Italian city, with more than 2.8 million people, and the country’s largest municipal territory measuring 1,287 km

2 [

45]. The area within the ancient city walls is recognised by UNESCO as Word Heritage site for its outstanding universal value [46, 47, 48]. Rome is nevertheless affected by strong socioeconomic divides and growing inequalities [49, 50] fuelled by an incessant urbanisation process often rooted on speculative practices [51, 52]. Polarizations are clearly visible in terms of health, education, employment and income [49, 53]. A monocentric, over-bounded urban structure is the result of different phases of expansion from the late 19

th Century. Peripheral areas are often spatially isolated, distant from the city’s social, cultural and political life, and characterised by the lack of services, urban amenities, and public spaces.

According to Lelo, Monni and Tomassi [

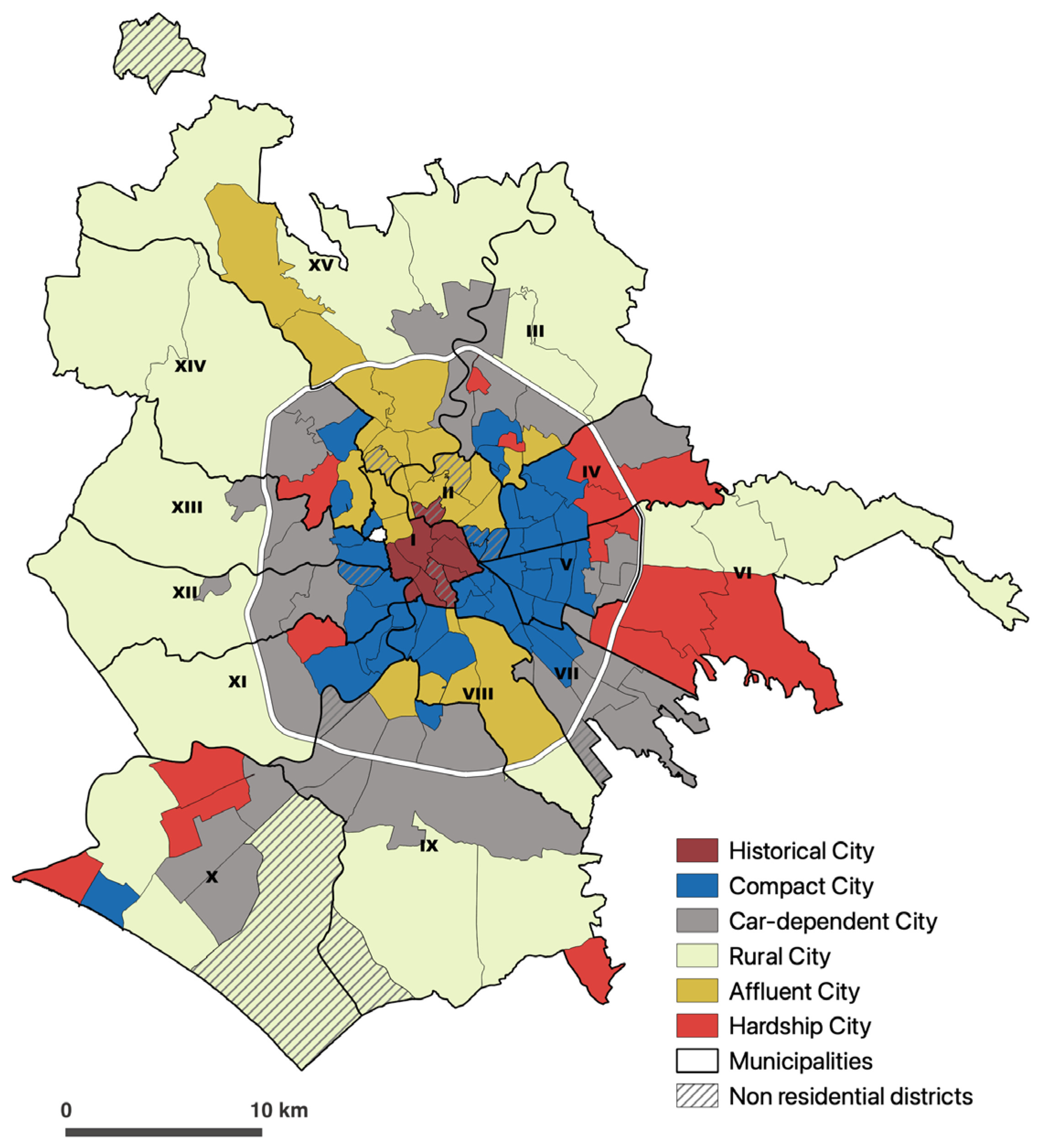

8] it is possible to identify “Seven cities” within Rome. Six of these are clearly distinguishable urban regions in terms of physical and socioeconomic characteristics which we include in our analysis (

Figure 1). Not considered here is the seventh city of 'the invisibles,' which it cannot be measured through reliable statistical sources since it represents temporary indigent populations (homeless, squatters, migrants, and so on.) [

8].

The Historical City is associated, to the point of cliché, with Rome itself. It encompasses the ancient city within the Aurelian walls, an area with less than 100,000 residents that represents only one percent of the municipal territory, visited every year by millions of tourists and pilgrims. Residents are constantly decreasing because a high share of real estate is used for short-term rentals and office spaces [54, 55]. Many of the residents are single and elderly individuals, and there is a comparatively high share of foreigners. The area offers many cultural facilities, public spaces, and effective public transportation.

Contiguous to the Historical City there is an intensive belt of neighbourhoods built during the first half of the 20

th Century known as the “historical” periphery, or

Compact City. With more than one million residents, this is the most densely inhabited part of the city, characterized by a scarce presence of green areas, good provision of public transportation and urban services, and plenty of spaces and opportunities for social interaction [

56].

The “new” peripheries developed during the second half of the 20

th Century beyond the Compact City, along the city’s ring road (Grande Raccordo Anulare – GRA) and highways are labelled as the

Car-dependent City, due to the need to use private transportation for most of the trips [

57]. These areas count about 610,000 residents and the population is progressively increasing. Residents are younger than the roman average, with a good employment rate and a smaller share of foreigners. The presence of big malls and shopping centres, and a low level of accessibility to public transportation are specific characteristics of these areas.

Beyond the peripheries it extends Rome’s historical agricultural region (Agro romano), labelled as the Rural City. In these areas, urban sprawl is taking place, causing a rapid increase of the residents by 80% since 2002. These fast-growing recent peripheries surrounded by agricultural land and large parks, suffer the almost completely lack of transportation services and urban amenities [58, 59]. The 180,000 residents living in these areas are typically younger, and families are typically larger than the roman average.

The linearity of this scheme: Historical City – Compact City – Car-dependent City – Rural City, appears in many cases overwhelmed by other, distinctive urban features, determined by the location choices of opposite social groups. Rich neighbourhoods can be found in different semi-central areas located northwest and south of the historic centre. With about 440,000 residents, the Rich City is characterised by the presence of highly qualified professionals, lower unemployment rates, higher housing quality, but public services are often limited, especially in neighbourhoods distant from the city centre. Oddly, poor neighbourhoods host as well about 440,000 residents. The Hardship City is located mostly in the outskirts, characterised by both informal areas (borgate) and large complexes of public housing [60, 61, 62]. Poverty, low education levels, unemployment, health problems are very frequent in these areas. Family size is on average larger than elsewhere, shares of young people and foreigners are higher, and the average living space is smaller.

At the administrative level Rome is organised into 15 Districts (

Municipi). For statistical purposes the municipal territory is subdivided into 155 urban areas (

Zone Urbanistiche - ZUs) that are the reference for urban planning and management activities

1.

Figure 1 illustrates the above-described socio-spatial characteristics of Rome through a thematic classification of the ZUs in six “cities”. We continue our analysis by defining and applying a Proximity model for Rome at the ZU level and, further on, by discussing the results for the different urban contexts (cities).

5. Methodology

Inspired by the 15-minute city model we select and analyse different urban services categorized according to the scheme of the “Urban Social Functions” (USF) introduced by C. Moreno. These categories are: Caring & Security “C&S”; Culture & Free time “C&F”; Education & Learning “E&L”; Mobility services “MS” and Other proximity services “OPS” [7, 63]. The data are obtained mainly from official administrative sources, only for a few private services on-line open sources were used. The services were first geolocalised and subsequently they were assigned to the pertinent urban area (ZU) to create a dataset that will serve as a basis for the proximity analysis.

Table 1 illustrates the type and category of the selected urban services, their average numerosity per ZU and the average number of services per 10,000 inhabitants in 2022, per ZU.

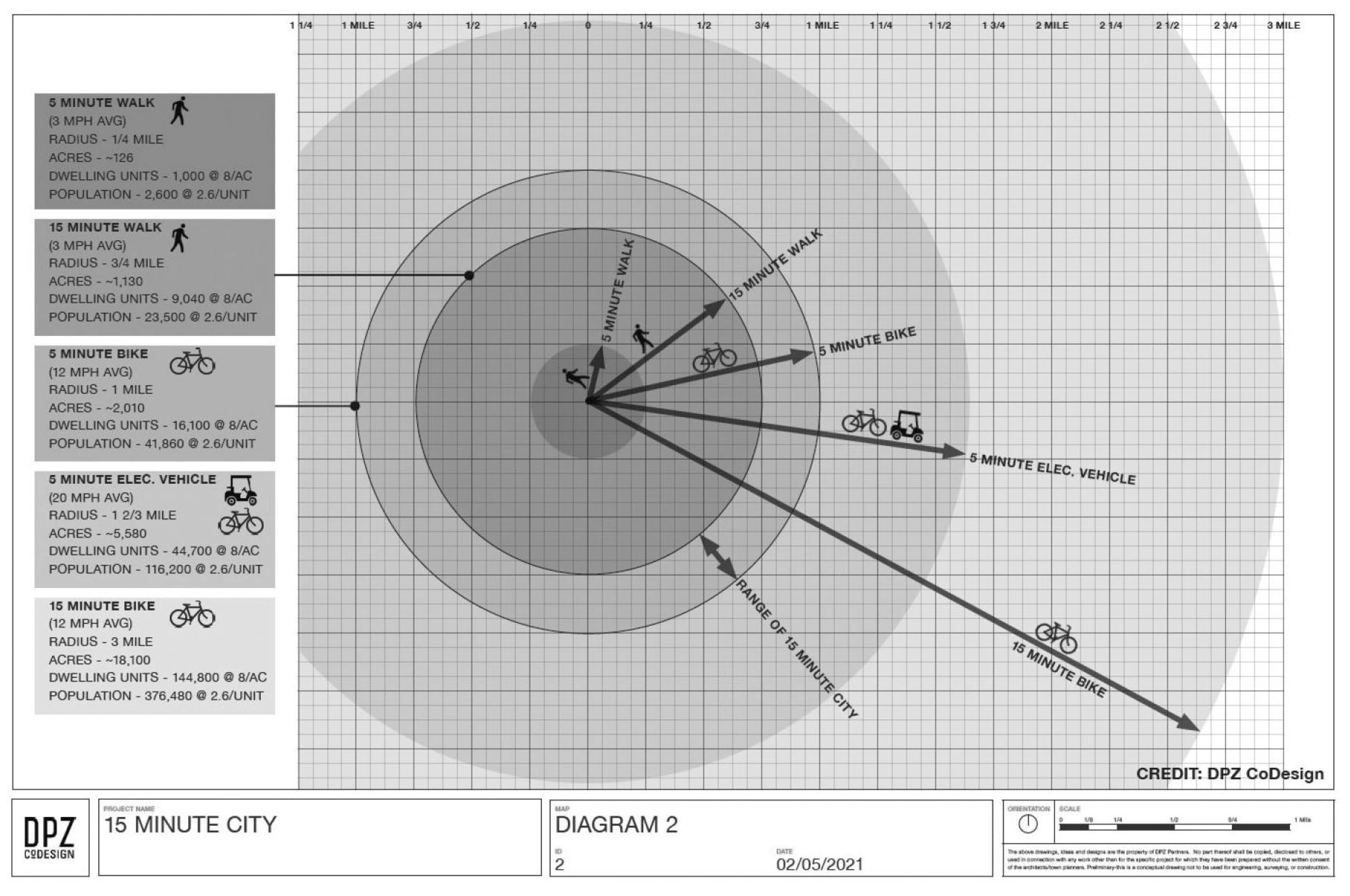

In a recent paper, Duany and Steuteville analyse the distances that can be covered in 15-minute walk and 15-minute cycling inside the city. They argue that a 15-minute walk, corresponding to three-quarters of a mile or about 1.2 km, is the maximum distance that most people are willing to walk. A coverage area corresponding to a 15-minute walk should include a full mix of urban services, such as grocery stores, pharmacies, general merchandise, public schools, and local public transportation facilities. A 15-minute cycling, corresponding to a coverage area of three-mile radius or about 3.8 km, should give access to major cultural, medical, and higher education facilities, regional parks and regional public transportation (

Figure 2) [

72].

What do we mean with “Proximity” to urban services? We consider as minimum spatial unit for Proximity analysis the 155 urban areas of Rome (ZU). In our approach the concept of Proximity to urban services, measured at ZU level, it has been declined in terms of a ratio between the total coverage of 15-minute walking or cycling calculated from each service geographic location and the area of the spatial unit. This approach accounts for overlapping coverage areas; thus, we consider an Intensity Index as a proxy for Proximity.

Selected urban services are organised in separate layers and grouped in the above-described USF categories. For each layer, from every geolocalised service, a 15-minute coverage area in hectares is calculated separately for the walking and cycling distances (“buffer” function). We applied the following criteria:

Distance covered in 15-minute walk at 1.34 m/s = 1207 m ≈ 1200 m

Distance covered in 15-minute cycling at 5.36 m/s = 4828 m ≈ 4830 m

For each urban service we calculate a “Service Intensity Index”

SI at the ZU level as follows:

Where is the portion of coverage area for 15-minute walk (or 15-minute cycling) intersecting each ZU, is the number of services within the ZU, and is the area of each ZU.

For each urban service, when we can assume sufficient to good proximity level for a ZU, since the total coverage area may be equal to or greater than the area of the spatial unit; when we can assume an insufficient proximity level since within the spatial unit there are areas uncovered by the service.

Further on, we measure a “Combined Intensity Index” (

CI) for each “Urban Social Function” (USF) for the 15-minute walk and the 15-minute cycling respectively, by computing the arithmetic mean of the normalised Intensity indexes of the urban services included in each USF (see

Table 1).

Where is the normalized Service Intensity Index and n is the number of services within the USF. For each USF CI values range between 0 (null proximity) and 1 (maximum proximity level). We compute 15-minute CI for the 15-minute walk and the 15-minute cycling respectively for Caring & Security, Culture & Free Time, Education & Learning, Mobility Services and Other Proximity Services.

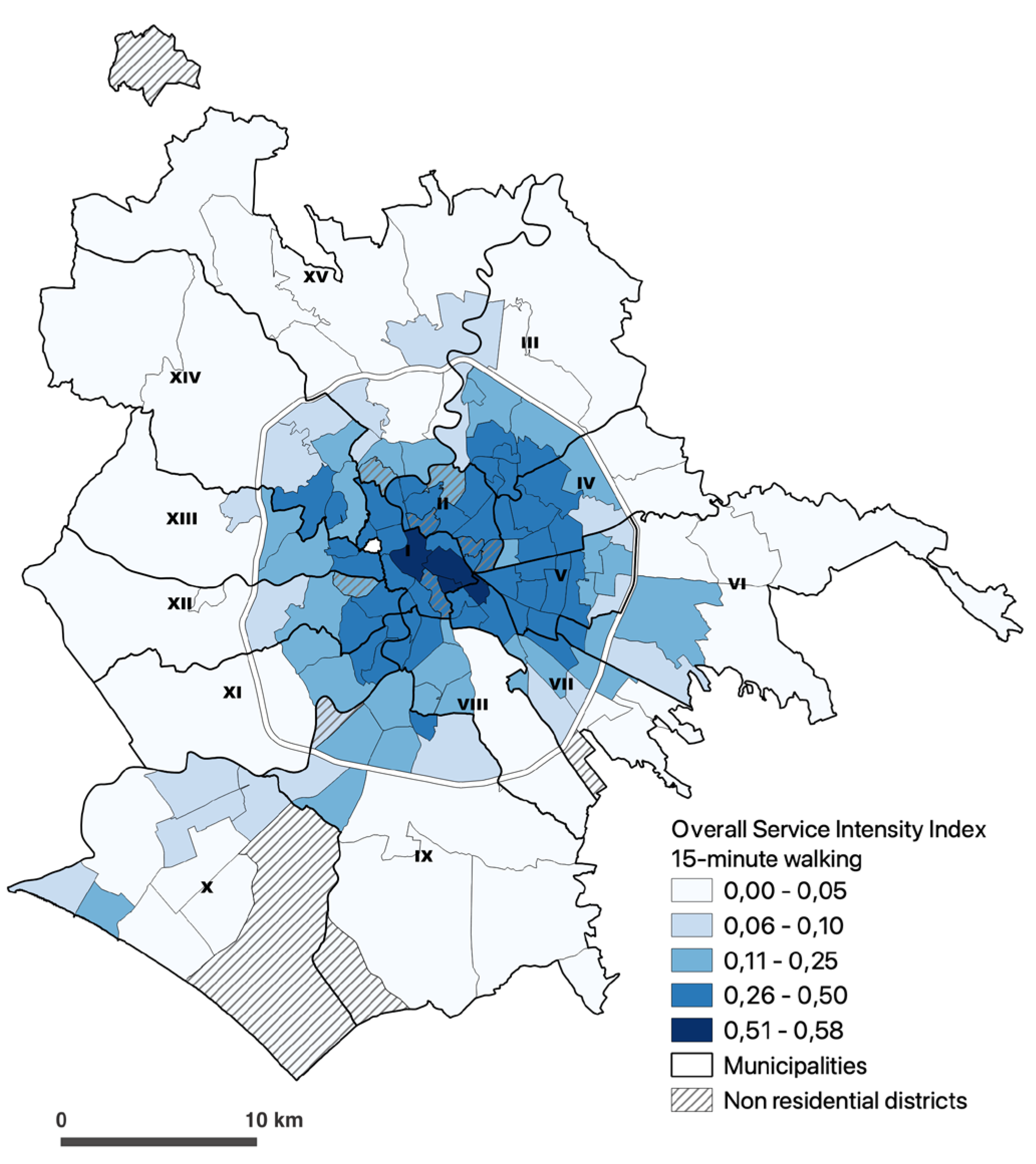

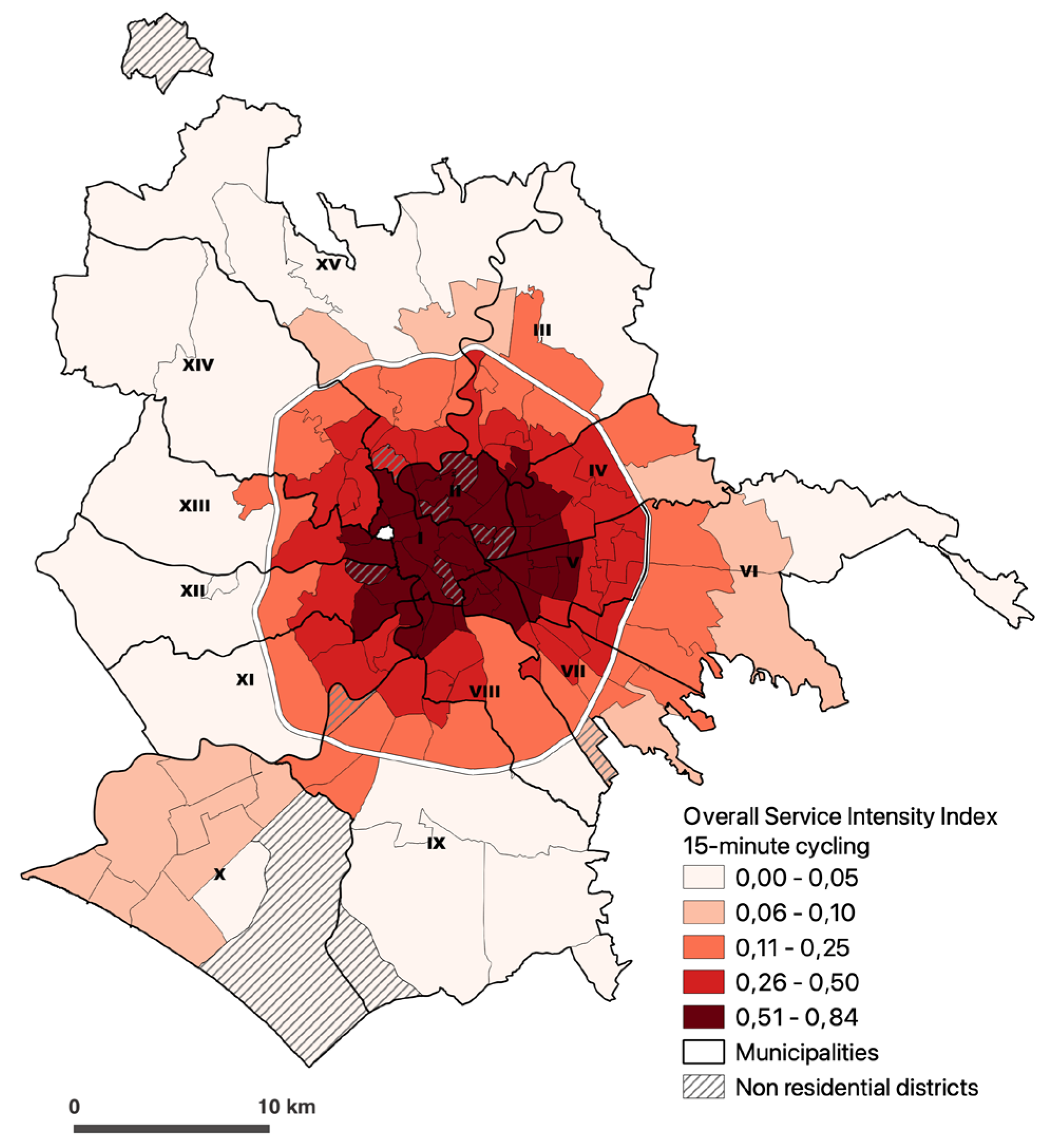

In addition, we decided to produce two “Overall Service Intensity Index” (OI) maps that consider all the services available within the 15-minute walk and the 15-minute cycling. The mapping outputs visually capture the overall Proximity to services in the urban areas (ZU) and their spatial distribution.

In the next section we present the results of our analysis for the municipal territory of Rome. To this regard, we would like to point out that this analysis is to be considered neither exhaustive nor complete since it adopts a number of highly simplifying assumptions. When defining the distance that can be covered in 15 minutes, the average adult is considered, excluding individuals in different conditions. We consider the urban space isotropic, not accounting for its different characteristics: road gradients, physical and architectural barriers, presence or absence of sidewalks and cycle paths, paving quality, lighting and other factors that may influence both walkability and cyclability. Furthermore, the individual preferences of citizens and their economic condition are not accounted for. Nevertheless, this analysis can be considered a first attempt to understand the nature of proximity in Rome, with the criteria of the 15-minute city.

6. Results and Discussion

While analysing the Service Intensity Index (SI), computed as the ratio between the total 15-minute walking or 15-minute cycling coverage area of a service in each spatial unit and the area of the spatial unit (ZU), we observe that the number of ZU with SI indicator considered insufficient (

) for 15-minute walking proximity is dramatically high for hospitals, high-level education services, cultural facilities in general, and services offered by local authorities. Such a result is expected, since these services are typically concentrated in a few places, and not evenly distributed towards the neighbourhoods. Proximity is low also for Co-working spaces and local markets, for public rail transportation, for nursing homes and clinics, while Education & Learning facilities for the age group 0-14 and Pharmacies show much higher 15-minute walking proximity. The SI indicator improves significantly for the 15-minute cycling proximity, maintaining nevertheless similar differences amongst the services (

Table 2).

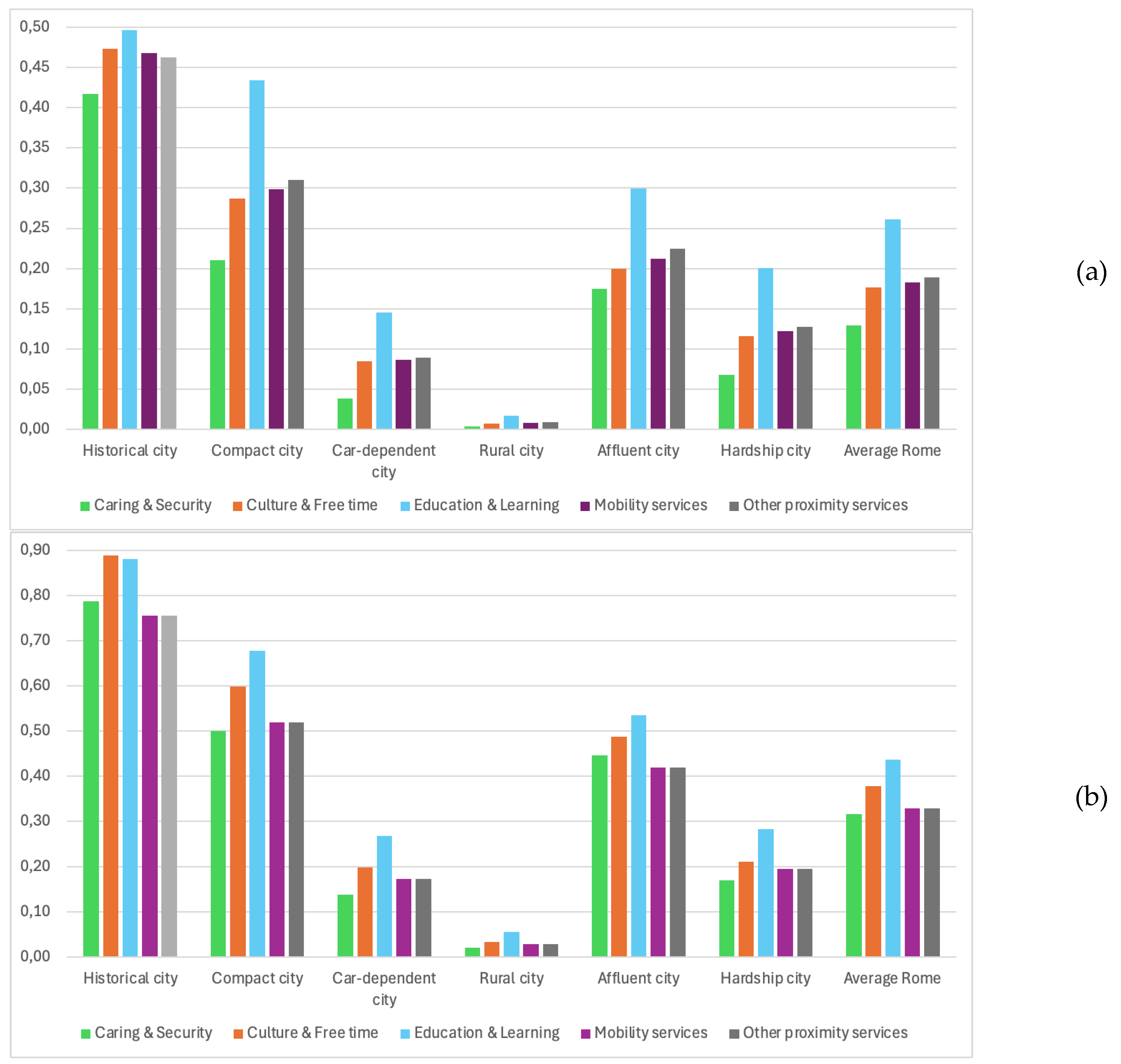

While analysing the Combined Intensity Index (CI), computed as the arithmetic mean of the normalised Service Intensity Indexes of single urban services included in each Urban Social Function (USF), we observe that proximity levels result in average rather low both for the 15-minute walking and the 15-minute cycling coverages, although singular ZUs may reach very high proximity levels, in particular for Education & Learning and the Mobility services (

Table 3). It is also important to notice that the minimum value of CI index is in all cases 0, meaning that there exist ZUs with no proximity to all services in all the USFs. Another consideration to be made concerns the number of ZUs positioned above the municipal average, which is rather restricted both for the 15-minute walking and the 15-minute cycling coverages; only for Education & Learning 15-minute walking proximity the number ZUs above the average reach the 57% of the total (88 out of 155), in all the other cases values are between 40% and 50%, with the exception of Caring & Security15-minute walking, with only 37% of ZUs having a proximity level above the average (

Table 3).

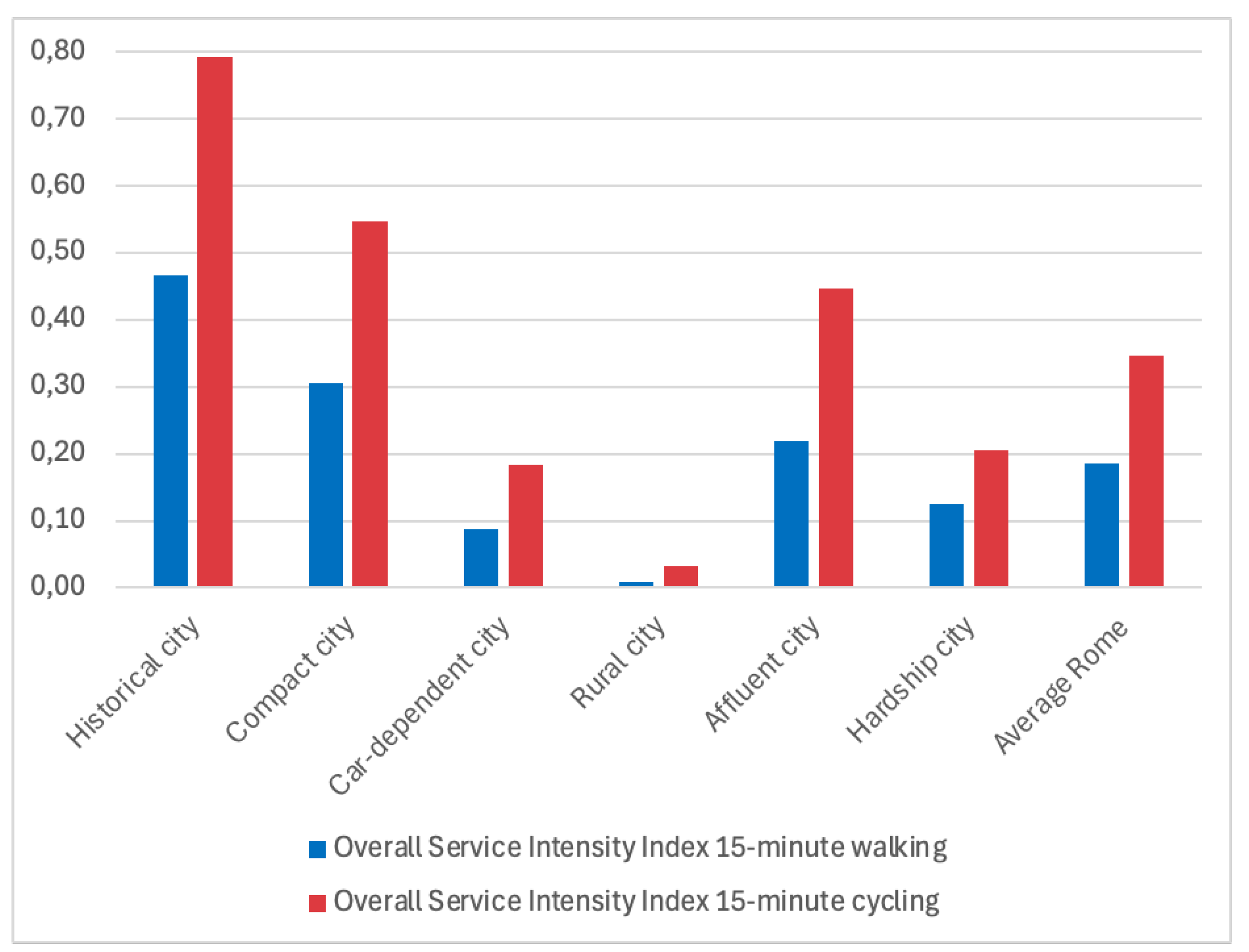

To better understand the dynamics of Proximity to urban services we analyse the CI values in the different “cities” of Rome introduced in

Section 4. First, it is obviously expected that Cycling proximity doubles compared to Walking proximity, uniformly across all the six “cities” and for all services (

Figure 3,

Table 4). The patterns for the six “cities” are similar for each service, with Education & Learning more evenly distributed across neighbourhoods and Caring & Security less so, while Culture & Free time, Mobility services, and Other proximity services show intermediate values (

Figure 3).

What changes from walking to cycling mainly depends on the territorial density of the services, as some are more spatially dispersed than others and therefore already offer better coverage when walking. For example, places of worship, kindergartens, and primary schools are better distributed even in some peripheral areas. While differentiating between the "cities," we can observe that the Car-dependent City and the Rural City have very low proximity levels for almost all services, as they are also the farthest from the centre. It is interesting to note that the Hardship City shows worse proximity levels if compared to the Rich City, also in this case, at least in part, due to the greater distance from the centre (

Table 4).

By mapping the Overall Service Intensity Index (OI) that consider all the services available within the 15-minute walk and the 15-minute cycling, we visually capture the overall Proximity to services in the urban areas (ZUs) and their spatial distribution (

Figure 4,

Figure 5). As already discussed, Rome is characterised by strong differences amongst different urban contexts, determined by demographic, social and economic divides, exacerbated by the distance from the city centre, where most of the opportunities and services are concentrated.

The urban areas with higher levels of both Walking and Cycling Proximity, are characterized by ageing population, small household sizes, robust cultural and public services, and the presence of public spaces and small-scale retail shops. Within these areas, municipal services and facilities are typically within the walking or cycling distance, fostering vibrant street life and frequent social interactions that enable residents to embrace their preferred lifestyles. These areas attract wealthier and more educated residents who can afford higher costs of housing, so that they enjoy public services, cultural amenities, shops and infrastructure. There is greater social capital, better access to networks and opportunities, and a higher standard of living.

Conversely, many peripheral areas of Rome, especially those beyond the ring road, exhibit lower levels of both Walking and Cycling Proximity. Despite having on average, younger population and larger households, they encounter limited access to cultural and educational opportunities, placing these areas at risk of exclusion from both education and the labour market. Notably high schools, universities and healthcare facilities are often far from these peripheral neighbourhoods, contributing to a lower quality of life, so that residents often perceive themselves as economically disadvantaged, socially marginalized, politically sidelined, and overlooked by central institutions. Moreover, their interactions with others are restricted, as they tend to rely on their own vehicles rather than walking or cycling, seldom frequent public squares or spaces due to their scarcity, and opt for large malls over small-scale retail shops for their shopping needs, further limiting social exchanges [73, 74, 75].

7. Conclusions

Cities have always been places of opportunity, thanks to the externalities generated by their nature as vast markets and incubators of ideas, as well as by the concentration of public investment and consumption. However, it is evident that opportunities are not distributed evenly, as cities are not isotropic spaces, and it does not always make sense to measure their performance with aggregated values at the municipal level. The conditions of marginalization that afflict many neighbourhoods in our cities, as well as the socio-economic inequalities that arise from them, depend on multiple factors of historical, physical, social, and economic nature.

The global success of the 15-minute city model has led to “proximity” becoming a buzzword for many city administrations, generating a renewed interest in the concept and the related urban practices [76, 77]. In recent years there have been numerous examples of urban policies embracing the proximity idea, such as the “open streets” strategy in Milan, the “ciudad a escala humana” in Buenos Aires, the “complete neighbourhoods” concept in Portland, the Barcelona’s “superilles”, or the “20-minute neighbourhood” in Melbourne [78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83].

In our attempt to analyse Proximity to urban services in the perspective of the 15-minute city in Rome, we rely on geospatial techniques to assess the distribution of Urban Social Functions (USF) at the sub-municipal level, using as a minimum spatial unit the urban areas (ZU). The results clearly indicate the strong imbalances, both in terms of spatial coverage and in terms of thoroughness of USFs. Given the extent and complexity of the municipality of Rome, we further extended our ZU-level analysis to the “seven cities” interpretation, to obtain a more effective comparison of the services distribution dynamics with the socioeconomic characteristics of the different urban contexts [

7]. It turns out that only the Historic and the Compact city have good proximity levels to USFs, which makes them easy to frame in terms of a 15-minute city model; the remaining cities still have serious deficiencies in services provision (

Figure 6). Service distribution clearly reflects the monocentric urban structure of Rome but looking exclusively at the physical aspects it might be misleading. As we have already discussed, Rome is characterized in the last decades by a process of expulsion of the residents from the densely urbanised central areas towards far-away, low-density peripheries. These complex socio-spatial dynamics have produced highly differentiated neighbourhoods in terms of economic performance, human development and quality of life, made evident in recent years by the results of the political elections, where rising levels of discontent enhance electoral support for right-wing or populist parties [

84]. Our analysis provides new evidence of the fact that the disadvantaged areas of the city suffer the most from the lack of proximity to services.

To what extent Rome can be considered a 15-minute city? Our results highlight the presence of strong inequalities and suggest to the policy makers the urgent need to address the relocation of services, the mobility infrastructures, the difficult social and economic conditions, in order to reduce the gaps and ensure a more balanced and equitable distribution of opportunities across the city. In this context role of policymakers is not an easy one. An important role in this process is related to the governance of the city, particularly in terms of decentralizing powers from the City Hall to the 15 municipalities into which the city is administratively divided. The current decentralization regulation of Rome dates back to 1999, and a revision process is currently underway. The conclusion of this process is particularly significant for achieving the polycentrism that is a central element of the proximity revolution embodied by the 15-minute city.

Our work intends to proceed from here, with the not-so-hidden ambition of being useful to those responsible for defining policies in Rome, by bringing this issue to the attention of policymakers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C., K.L., S.M., F.T.; investigation, F.C., K.L., S.M., F.T.; writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, F.C., K.L., S.M., F.T.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 |

Some ZUs are scarcely inhabited and characterised by the presence of parks, services or archaeological sites. These are referred to as “non-residential”. |

References

- United Nations. (1987). Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf.

- United Nations. (1990). Human development report 1990. United Nations Development Programme (New York). Oxford University Press. https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/hdr1990encompletenostats.pdf.

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme. (2022). World Cities Report. Envisaging the future of cities. UN-Habitat. https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2022/06/wcr_2022.pdf.

- De Simone, E. (2018). Storia economica: Dalla rivoluzione industriale alla rivoluzione informatica (5th updated ed.). Franco Angeli.

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf.

- Moreno, C., Allam, Z., Chabaud, D., Gall, C., & Pratlong, F. (2021). Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-Pandemic Cities. Smart Cities, 4(1), 93–111. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C., Gall, C., Chabaud, D., Garnier, M., Illian, M., & Pratlong, F. (2023). The 15-minute City model: An innovative approach to measuring the quality of life in urban settings 30-minute territory model in low-density areas. WHITE PAPER N° 3 (Doctoral dissertation, IAE Paris-Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne).

- Lelo, K. , Monni, S. & Tomassi, F. (2021). Le Sette Rome. La capitale delle disuguaglianze raccontata in 29 mappe. Donzelli Editore.

- Moreno, C. (2019a). Meeting With Carlos Moreno: Human Smart Cities. Last access: 21/04/2024. https://www.moreno-web.net/meeting-with-carlos-moreno-human-smart-cities/.

- Moreno, C. Dalla “Città dei 15 minuti” a “Roma a portata di mano” in Roma Capitale. (2024). Roma a portata di mano. La città dei 15 minuti. https://www.comune.roma.it/web-resources/cms/documents/EBOOK.pdf.

- Moreno, C. (2015). Urban spaces, territories and digital technology: towards the emergence of city worlds (EN, FR, ESP). Last access: 22/04/2024. https://www.moreno-web.net/urban-spaces-territories-and-digital-technology-towards-the-emergence-of-city-worlds/.

- Khavarian-Garmsir, A. R., Sharifi, A., Hajian Hossein Abadi, M., & Moradi, Z. (2023). From Garden City to 15-Minute City: A Historical Perspective and Critical Assessment. Land, 12(2), 512. [CrossRef]

- Perry, C. A. (1929). The Neighborhood Unit, a Scheme of Arrangement for the Family-life Community: Published as Monograph 1 in Vol. 7 of Regional Plan of N.Y. Regional Survey of N.Y. and Its Environs, 1929. https://books.google.it/books?id=JhptGwAACAAJ.

- Jacobs, J. (1961). The death and life of great American cities. Vintage Books. A division of Random House, inc. New York. https://www.petkovstudio.com/bg/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/The-Death-and-Life-of-Great-American-Cities_Jane-Jacobs-Complete-book.pdf.

- Garde, A. (2020). New Urbanism: Past, Present, and Future. Urban Planning, 5(4), 453–463. [CrossRef]

- Pozoukidou, G., & Chatziyiannaki, Z. (2021). 15-Minute City: Decomposing the New Urban Planning Eutopia. Sustainability, 13(2), 928. [CrossRef]

- Ascher, F. (1995). Métapolis: Ou l’avenir des villes. Editions Odile Jacob. https://books.google.it/books?id=6b3-aOVl0bkC.

- M. E. Arth. (n.d.). Anatomy of a Pedestrian Village. Last access: 29/04/2024. https://www.michaelearth.com/what-is-new-pedestrianism.html.

- Lerner, J. (2003). Acupuntura Urbana, Editora Record.

- Casagrande, M. (2010) Urban Acopunture. Adam Parsons, University of Portsmouth.

- Chartier, H. (2024). La città dei 15 minuti: un modello di pianificazione urbana in Roma Capitale. (2024). Roma a portata di mano la città dei 15 minuti. https://www.comune.roma.it/web-resources/cms/documents/EBOOK.pdf.

- C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group. (C40). (2020). C40 Mayors’ Agenda for a Green and Just Recovery. https://www.c40knowledgehub.org/s/article/C40-Mayors-Agenda-for-a-Green-and-Just-Recovery?language=en_US.

- C40. (2023). 15-minute city initiatives explorer. Last access: 20/04/2024. https://www.c40knowledgehub.org/s/article/15-minute-city-initiatives-explorer?language=en_US.

- Petrella, L. (2024). UN-Habitat e la città dei 15 minuti in Roma Capitale. (2024). Roma a portata di mano. La città dei 15 minuti. https://www.comune.roma.it/web-resources/cms/documents/EBOOK.pdf.

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme. (2017). New Urban Agenda. https://habitat3.org/wp-content/uploads/NUA-English.pdf.

- EIT Urban Mobility. (2022). Urban Mobility Next 9. ±15-Minute City: Human-centred planning in action. Mobility for more liveable urban spaces. https://www.eiturbanmobility.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/EIT-UrbanMobilityNext9_15-min-City_144dpi.pdf.

- Camagni, R. (1998). Principi di economia urbana e territoriale (2nd printing). Carocci Editore.

- Noworól, A., Kopyciński, P., Hałat, P., Salamon, J., & Hołuj, A. (2022). The 15-Minute City—The Geographical Proximity of Services in Krakow. Sustainability, 14(12), 7103. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C. (2019b). The 15 minutes-city: for a new chrono-urbanism! – Pr Carlos Moreno. Last access: 24/04/2024. https://www.moreno-web.net/the-15-minutes-city-for-a-new-chrono-urbanism-pr-carlos-moreno/.

- Bourdic, L., Salat, S., & Nowacki, C. (2012). Assessing cities: A new system of cross-scale spatial indicators. Building Research & Information, 40(5), 592–605. [CrossRef]

- Witten, K., Exeter, D., & Field, A. (2003). The quality of urban environments: Mapping variation in access to community resources. Urban studies, 40(1), 161-177. [CrossRef]

- Brambilla, M., Michelangeli, A., & Peluso, E. (2013). Equity in the City: On Measuring Urban (Ine)quality of Life. Urban Studies, 50(16), 3205–3224. [CrossRef]

- Guida, C., & Carpentieri, G. (2021). Quality of life in the urban environment and primary health services for the elderly during the Covid-19 pandemic: An application to the city of Milan (Italy). Cities, 110, 103038. [CrossRef]

- Gaglione, F., Gargiulo, C., Zucaro, F., & Cottrill, C. (2022). Urban proximity in a 15-minute city: A measure in the city of Naples, Italy. Transportation Research Procedia, 60, 378–385. [CrossRef]

- Murgante, B., Patimisco, L., & Annunziata, A. (2024). Developing a 15-minute city: A comparative study of four Italian Cities-Cagliari, Perugia, Pisa, and Trieste. Cities, 146, 104765. [CrossRef]

- Hosford, K., Beairsto, J., & Winters, M. (2022). Is the 15-minute city within reach? Evaluating walking and cycling proximity to grocery stores in Vancouver. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 14, 100602. [CrossRef]

- Modica, A. (2022). Roma in 15 minuti: cultura, ambiente e digital divide in Roma Capitale. (2024). Roma a portata di mano. La città dei 15 minuti. https://www.comune.roma.it/web-resources/cms/documents/EBOOK.pdf.

- Barbieri, L., D’Autilia, R., Marrone, P., & Montella, I. (2023). Graph Representation of the 15-Minute City: A Comparison between Rome, London, and Paris. Sustainability, 15(4), 3772. [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Ortiz, C., Marquet, O., Mojica, L., & Vich, G. (2022). Barcelona under the 15-Minute City Lens: Mapping the Proximity and Proximity Potential Based on Pedestrian Travel Times. Smart Cities, 5(1), 146–161. [CrossRef]

- Staricco, L. (2022). 15-, 10- or 5-minute city? A focus on proximity to services in Turin, Italy. Journal of Urban Mobility, 2, 100030. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D., Kwan, M.-P., & Wang, J. (2024). Developing the 15-Minute City: A comprehensive assessment of the status in Hong Kong. Travel Behaviour and Society, 34, 100666. [CrossRef]

- Olivari, B., Cipriano, P., Napolitano, M., & Giovannini, L. (2023). Are Italian cities already 15-minute? Presenting the Next Proximity Index: A novel and scalable way to measure it, based on open data. Journal of Urban Mobility, 4, 100057. [CrossRef]

- Vale, D., & Lopes, A. S. (2023). Proximity inequality across Europe: A comparison of 15-minute pedestrian proximity in cities with 100,000 or more inhabitants. npj Urban Sustainability, 3(1), 55. [CrossRef]

- Gualtieri, R. (2024). Prefazione in Roma Capitale. (2024). Prefazione in Roma Capitale. (2024). Roma a portata di mano la città dei 15 minuti. https://www.comune.roma.it/web-resources/cms/documents/EBOOK.pdf.

- Comune di Roma. (2023a). Annuario Statistico 2023. https://www.comune.roma.it/web-resources/cms/documents/Annuario_2023_.pdf.

- Lelo, K., & Travaglini, C. M. (2006). Dalla «Nuova Pianta» del Nolli al Catasto urbano Pio-Gregoriano: L’immagine di Roma all’epoca del Grand Tour. Città e Storia, 2, 431-456.

- Tocci, W. (2020). Roma come se: Alla ricerca del futuro per la capitale. Donzelli Editore.

- Bertelli, P. (1991). Note sull’industria a Roma, dalla fine del regime pontificio alla Seconda guerra mondiale. Storia urbana, (1991/57).

- Lelo, K., Monni, S., Tomassi, F. (2019) “Socio-Spatial inequalities and Urban Transformation. The Case of Rome Districts”, in Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 68.

- De Muro, P., Monni, S., & Tridico, P. (2011). Knowledge-Based Economy and Social Exclusion: Shadow and Light in the Roman Socio-Economic Model: Knowledge-based economy and social exclusion in Rome. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 35(6), 1212–1238. [CrossRef]

- Bartolini, F. (2002). Condizioni di vita e identità sociali: Nascita di una metropoli. In Roma capitale (pp. 3-36). Laterza.

- Cellamare, C. (2013). Processi di auto-costruzione della città. Self-making processes in the city. UrbanisticaTre, 2(I Quaderni), 7-33.

- Lelo, K., Monni, S., & Tomassi, F. (2019). Le mappe della disuguaglianza una geografia sociale metropolitana. Donzelli Editore.

- Bei, G. and Celata F. (2023) “Challenges and effects of short-term rentals regulation: A counterfactual assessment of European cities”, Annals of Tourism Research, 101.

- Brollo, B. and Celata F. (2023) “Temporary populations and sociospatial polarisation in the short-term city”, Urban Studies, 60 (10): 1815–32.

- Dantzig, G.B. and Saaty T.L. (1973) Compact City: A Plan for a Liveable Urban Environment, San Francisco, Freeman.

- Cellamare, C. (2014) “Ways of Living in the Market City. Bufalotta and the Porta di Roma Shopping Center”, in Thomassen B. and Clough Marinaro I. (eds.), Global Rome: Changing Faces of the Eternal City, Bloomington, Indiana University Press.

- Egidi G., Halbac-Cotoara-Zamfir R., Cividino S., Quaranta G., Salvati L., Colantoni A. (2020) “Rural in Town: Traditional Agriculture, Population Trends, and Long-Term Urban Expansion in Metropolitan Rome”, Land, (9) 53.

- Lelo, K. (2016) “Agro romano: un territorio in trasformazione”, Roma moderna e contemporanea, 1-2: 9-48.

- Cellamare, C. (2014) “The Self-Made City”, in Thomassen B. and Clough Marinaro I. (eds.), Global Rome: Changing Faces of the Eternal City, Bloomington, Indiana University Press.

- Coppola A. (2018) “A Very Old Neo-Liberalism: The Changing Politics and Policy of Urban Informality in the Roman Borgate”, in Caldwell L. and Camilletti F. (eds.), Rome: Modernity, Postmodernity and Beyond, Cambridge.

- Puccini, E. and Tomassi F. (2019) “La condizione abitativa delle case popolari a Roma”, in Adorni D. and Tabor D. (eds.), Inchieste sulla casa in Italia. La condizione abitativa nelle città italiane nel secondo dopoguerra, Rome, Viella.

- Moreno, C. (2024) “La città dei 15 minuti. Per una cultura urbana democratica”. Add editore.

- Protezione Civile. (2023). Piano di Protezione Civile di Roma Capitale. Informazioni di carattere generale. https://www.comune.roma.it/web-resources/cms/documents/PPC2024_1_InformazioneGenerale_Allegati.pdf.

- Regione Lazio. (2015). Open data. [dataset]. http://dati.lazio.it/catalog/it/dataset.

- Roma Mobilità. (2024). Dataset geografici. [dataset]. https://romamobilita.it/it/tecnologie/dataset-geografici.

- Open Street Map. (2016b). Mappa fermate autobus in Italia. [dataset]. https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=5/42.088/12.564.

- Open Street Map. (2016a). Mappa delle banche in Italia. [dataset]. https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=5/42.088/12.564.

- Mappa sportelli prelievo automatico denaro (ATM) in Italia.

- Roma Capitale. (2022). Elenco coworking. [dataset]. https://www.comune.roma.it/web-resources/cms/documents/elenco-coworking-roma.pdf.

- Roma Capitale. (2023c). Mercati rionali. [dataset]. https://www.comune.roma.it/web/it/scheda-servizi.page?contentId=INF690431&stem=commercio_su_aree_pubbliche.

- Duany, A. & Steuteville, R. (2021). Defining the 15-minute city. Last access: 06/05/2024. https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2021/02/08/defining-15-minute-city.

- Lelo, K. , Monni, S. & Tomassi, F. (2019). Le mappe della disuguaglianza. Una geografia sociale metropolitana. Donzelli, pp. 41-51.

- Lelo, K. , Monni, S. & Tomassi, F. (2019). Le mappe della disuguaglianza. Una geografia sociale metropolitana. Donzelli, pp. 14-21.

- Lelo, K. , Monni, S. & Tomassi, F. (2019). Le mappe della disuguaglianza. Una geografia sociale metropolitana. Donzelli, pp. 34-39.

- Chiaradia, F., Lelo, K. & Monni, S. (2023). La “città dei 15 minuti” tra realtà e leggende. Economia e Politica. https://www.economiaepolitica.it/indagini/la-citta-dei-15-minuti-tra-realta-e-leggende.

- Moreno, C. (2024). The 15-Minute city: a solution to saving our time and our planet. John Wiley & Sons.

- Driving Urban Transitions. (2024). Mapping of 15-minute City Practices. Overview on strategies, policies and implementation in Europe and beyond. https://dutpartnership.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/DUT_15-minute-City-Mapping_04-2024.

- Open Streets. https://www.comune.milano.it/documents/20126/7117896/Open+streets.pdf/d9be0547-1eb0-5abf-410b-a8ca97945136?t=1589195741171.

- Buenos Aires Ciudad. (n.d.). Nuestro compromiso de hacer de Buenos Aires una ciudad a escala humana. Last access: 04/04/2024. https://buenosaires.gob.ar/noticias/nuestro-compromiso-de-hacer-de-buenos-aires-una-ciudad-escala-humana.

- C40. (2022). The 15-minute city: International experiences. Last access: 18/04/2024. https://www.c40knowledgehub.org/s/article/The-15-minute-city-International-experiences?language=en_US.

- Ajuntament de Barcelona (n.d.). Superilles. Last access: 04/04/2024. https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/superilles/en/.

- Victoria State Government. Plan Melbourne. Last access: 04/04/2024. https://www.planning.vic.gov.au/guides-and-resources/strategies-and-initiatives/plan-melbourne.

- Tomassi, F. (2024). “The revenge of districts that don’t matter: inequality and elections in Rome from 2000 to 2023”, Contemporary Italian Politics, published on-line. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).