* yuliage@ariel.ac.il

1. Introduction

The human papillomavirus (HPV) is a group of more than 100 viral strains that infect the skin and mucous membranes. It is transmitted primarily through intimate contact and is the most prevalent sexually transmitted infection worldwide (1). Typically asymptomatic, individuals often unknowingly transmit the virus to others. HPV can lead to various cancers, most notably cervical cancer, which is the second most common cancer in women after breast cancer. In 2018, cervical cancer caused more than 300,000 deaths globally, predominantly in low- and middle-income countries with limited access to public health services and early screening. In addition to cervical cancer, HPV is associated with other severe health issues, such as vaginal and vulvar cancers in women, penile cancer in men, and conditions such as anal and oropharyngeal cancers, genital warts, and recurrent respiratory papillomatosis in both genders (2,3). Consequently, the economic burden of HPV is substantial, estimated at approximately $49 million annually (4,5). These epidemiological findings are consistent across developed nations, including Israel, where the prevalence of HPV-related morbidities is comparable and permeates all segments of the Israeli population (6).

The World Health Organization (WHO) aims to eliminate cervical cancer by 2030 through a strategy of vaccination, screening, and treatment. This includes ensuring that 90% of girls are fully vaccinated against HPV by age 15, 70% of women are screened by age 35 and again by age 45, and 90% of women with pre-cancerous lesions or invasive cancer receive appropriate treatment (7). Vaccination has been proven to be an effective primary preventive measure against HPV. Currently, there are three types of HPV vaccines: Cervarix, Gardasil-4, and Gardasil-9 (8). Gardasil-9, which protects against cancer-causing HPV strains, has been the sole vaccine available in the United States since 2016 (9). In Israel, since late 2019, Gardasil-9 has been administered to boys and girls in the eighth grade through a national vaccination program, with catch-up vaccination available in the ninth grade and for individuals at risk up to age 26, although in Israel, it is offered to individuals up to age 45 (10).

Global HPV vaccination rates vary widely among countries and regions. In many high-income countries, HPV vaccination coverage ranges from 70% to over 90% among children and young adults (ages 9-26). However, in low- and middle-income countries, coverage rates can be significantly lower, often less than 50% (3,11). In Israel, despite the vaccine’s safety, efficacy, availability, and inclusion in the health basket (which allows for free administration), HPV vaccination rates remain low, with annual rates fluctuating between 52% and 64% (12,13), in contrast to the high coverage rates (≥95%) for other routine vaccines (e.g., MMRV (measles, mumps, rubella, varicella) and Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis) vaccines) offered through schools in Israel (14). Low immunization rates against HPV are often attributed to inadequate information for informed decision-making, exposure to vaccine-hesitant misinformation online, and local structural barriers that hinder vaccine uptake. Additionally, concerns about discussing sexual health topics, particularly when they conflict with religious beliefs, further contribute to low vaccination rates (15,16).

Nurses, who constitute the largest segment of the healthcare workforce, are uniquely positioned to address the growing need for education about HPV and the benefits of HPV vaccines (17). Their frequent and direct contact with patients, along with their primary role in patient education, enables them to help patients understand the risks and benefits of preventive treatment options. Patients often seek nurses for health-related advice, making them ideal primary contacts for immunization information, concerns, and adherence (18). While their role as patient advocates is well established in Israel, their potential as HPV vaccine advocates is not yet fully recognized or widely embraced (13,19). Given the authority and trust they command in healthcare delivery, nurses are ideally suited to advocate for HPV vaccination and significantly influence vaccine decisions (20,21).

In the United States, nurses are primary sources of guidance for recommended student vaccinations, with school nurses being particularly important in educating parents about HPV vaccination and advocating for cervical cancer prevention (20). However, adequate knowledge levels are essential for nurses to effectively fulfill this role. Previous studies conducted in Cyprus (22) and Cameroon (23) have demonstrated that enhanced education and training for nurses and midwives can increase their willingness to recommend HPV vaccination, thus boosting uptake rates. Similarly, research from Turkey (24,25) and Spain (26) found that increasing nursing students' knowledge of HPV can positively impact their intention to advocate for vaccination. In Israel, a recent study identified significant knowledge gaps among nurses regarding HPV and its vaccination, suggesting that, as in other countries, targeted education and training could be critical for improving vaccine advocacy and uptake (27).

Despite the vital role that nurses play in patient education, the impact of these knowledge deficits on their attitudes and willingness to promote HPV vaccination remains unclear, particularly among nursing students. Our study aims to assess the current knowledge and attitudes of Israeli nurses and nursing students towards HPV and its vaccine, identifying areas of misinformation. Additionally, this study aims to explore how cultural, religious, and social beliefs influence their willingness to advocate for HPV vaccination. By understanding these factors, this research provides insights into the barriers and facilitators that shape healthcare professionals' support for HPV vaccination within the diverse Israeli population.

2. Methods

2.1. Setting

From August 2023 – January 2024, we conducted a rapid cross-sectional study using an anonymous online questionnaire distributed via Facebook groups specifically targeted at nurses and nursing students. The questionnaire link, hosted on Qualtrics™, was shared in several professional groups that collectively reached thousands of potential participants across the country. These groups included members from diverse healthcare settings, such as hospitals, community clinics, and other healthcare facilities, ensuring a broad and representative sample of the nursing community. Respondents were invited to participate voluntarily, with no incentives provided, and were limited to one response per individual to maintain data integrity.

2.2. Participants

The study targeted Hebrew-speaking nurses and nursing students actively engaged in healthcare settings. All participants were required to be either currently practicing nurses or enrolled in nursing programs. No other exclusion criteria were applied, allowing for a wide range of experiences and backgrounds to be represented in the sample.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of XXX University, approval code: AU-HEA-YG-20230111. Written informed consent was obtained electronically from all participants before they accessed the questionnaire. Participants were assured of their anonymity and the confidentiality of their responses.

2.4. Measures

The online questionnaire included three sections designed to assess the knowledge and attitudes of nurses and nursing students towards HPV and its associated vaccine:

Demographic data: Participants were asked to provide detailed demographic information, including age, gender, marital status, number of children, nationality, religiosity level, education, years of experience in nursing, workplace, role, and vaccination status against HPV.

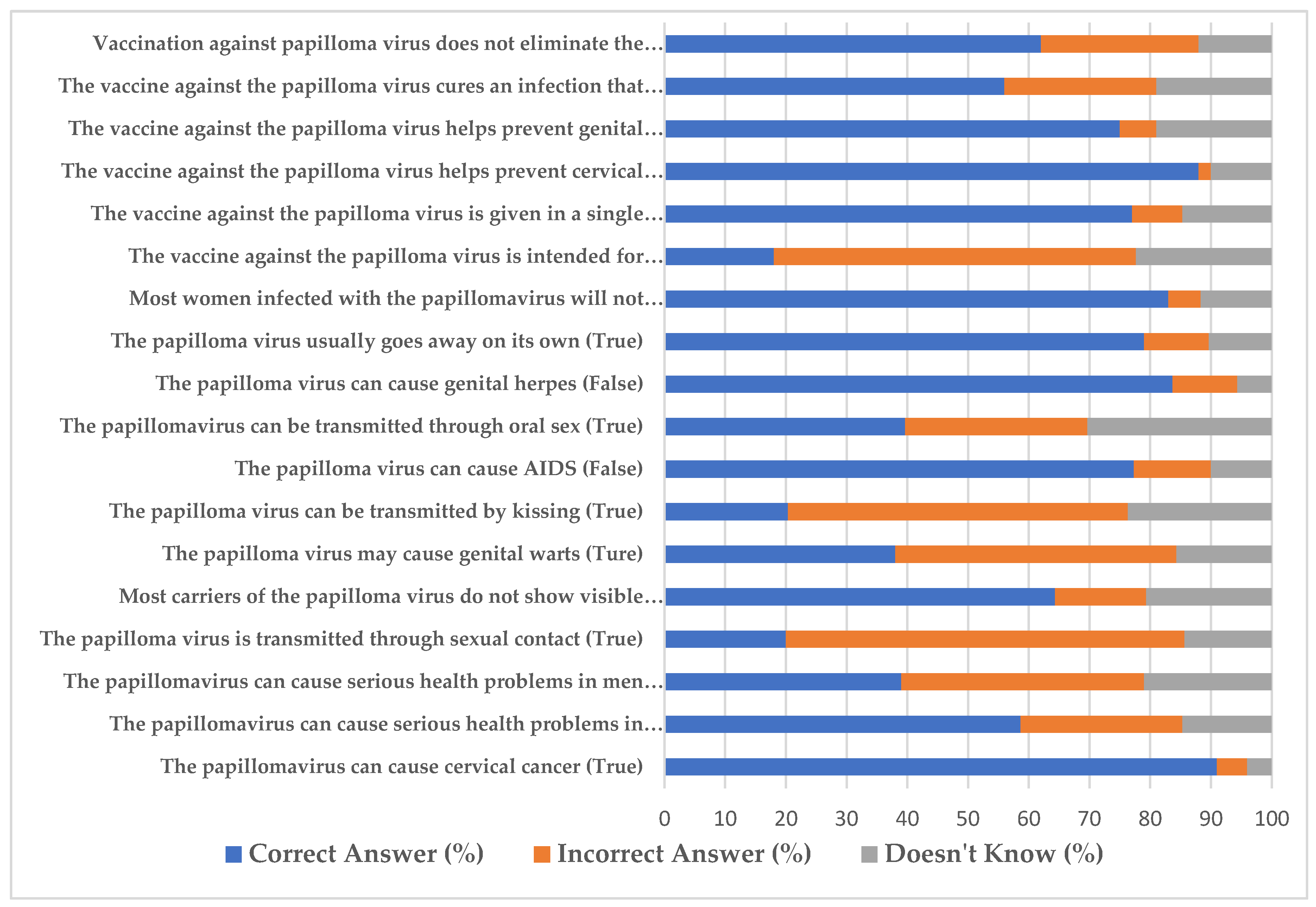

Knowledge assessment: Participants' knowledge about human papillomavirus (HPV) and its associated vaccine was assessed using an 18-item structured knowledge questionnaire that has been validated in previous studies (28,29). This tool was originally developed based on established literature and expert input, with its validity and reliability confirmed through prior research.

The questionnaire comprised a series of true/false statements designed to evaluate participants' understanding of HPV transmission, the efficacy and purpose of the HPV vaccine, and common misconceptions about the virus and its vaccine. The participants were asked to indicate whether they believed each statement to be true or false, with an additional "don't know" option for those who were unsure of the answer.

To assess the overall level of knowledge among participants, the percentage of correct, incorrect, and "don't know" responses was calculated for each item. Higher percentages of correct answers indicated better knowledge, whereas higher percentages of incorrect or "don't know" responses highlighted areas where misinformation or lack of knowledge was prevalent. The questionnaire addressed key topics, including whether HPV can cause serious health problems, the effectiveness of the HPV vaccine in preventing cervical cancer, and common myths such as HPV causing AIDS or genital herpes.

Attitude assessment: Attitude toward HPV vaccination was evaluated using a structured questionnaire specifically designed for this study. The questionnaire was divided into three sections: (1) attitudes toward the HPV vaccine and vaccination, (2) attitudes toward nurses' role in HPV vaccination, and (3) attitudes toward the national vaccination program. Each section consisted of a series of statements to which participants responded via a 5-point Likert scale ranging from "strongly disagree" to "strongly agree."

The first section, attitude towards the HPV vaccine and vaccination, comprised six items assessing participants' beliefs about the importance and necessity of HPV vaccination for both men and women, the prevention of HPV-related diseases, and the justification for vaccination based on HPV's association with cancer.

The second section, attitude towards nurses' role in HPV vaccination, included four items evaluating participants' views on the responsibility of nurses to recommend and advise on HPV vaccination, the importance of addressing negative opinions about the vaccine, and the perceived equivalence of the HPV vaccine with other routine vaccinations.

The third section, attitude towards the national vaccination program, consisted of two items measuring participants' general support for routine vaccinations and their trust in the decisions made by health authorities, such as the Ministry of Health.

For items where agreement reflected a negative or incorrect attitude towards HPV vaccination, such as "women have already been vaccinated against HPV, so there is no need to vaccinate men as well," reverse scoring was applied. This ensured that higher scores uniformly represented more positive or correct attitudes. The mean scores for each section were calculated, with reverse scoring applied as necessary, to provide an overall assessment of attitudes within each category, ensuring consistent interpretation across all items.

2.5. Data Analysis

The data were extracted from Qualtrics™ and analyzed via IBM SPSS version 29. Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarize the demographic characteristics, knowledge levels, and attitudes of the participants. Frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables, whereas means and standard deviations were reported for continuous variables. Independent samples t tests were conducted to compare attitudes between nurses and nursing students. A logistic regression model was used to identify factors predicting a positive attitude towards HPV vaccination, defined as a score of 3.5 or above on the attitude scale. The model included predictors such as gender, marital status, nationality, religiosity level, role (nurses vs. nursing students), workplace, years of experience in nursing, and knowledge level. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated to assess the strength of these associations. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

The study included 458 participants (229 nurses and 229 nursing students) with a mean age of 41.0 years (SD = 12.1). The majority were female (72.1%) and married (71.6%). In terms of nationality, 62.7% of participants identified as Jewish, and 26.6% as Muslim Arabs. Half of the participants were nursing students, 39.3% held a BA degree, and 10.7% held a Master's degree. Participants reported an average of 13.5 years (SD = 13.0) of nursing experience, with 66.6% working in hospitals, 25.3% in community settings, and 8.1% in other workplaces. Among the participants, 40.4% were staff nurses, and 9.6% held management positions. Additionally, 29.3% of the participants reported being vaccinated against HPV. Among those with children, 21.2% indicated that their children were vaccinated, 44.3% reported that their children were not vaccinated, and 34.5% stated that this was not applicable. The sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants are presented in

Table 1.

The knowledge assessment (see

Figure 1) revealed varying levels of understanding regarding HPV and its vaccine among participants. The majority of participants correctly identified that vaccination against the papillomavirus does not eliminate the need for regular screening (87%) and that the HPV vaccine helps prevent cervical cancer (92%). However, significant gaps in knowledge were observed in several areas. For example, 52% of participants incorrectly believed that the vaccine cures an existing HPV infection, and 47% mistakenly thought the vaccine is administered in a single dose. Additionally, misconceptions such as believing that the HPV vaccine is intended only for women (38%) and that HPV can cause genital herpes (31%) were prevalent. A notable proportion of participants (40%) were unsure of whether the papillomavirus can be transmitted through oral sex, and 29% mistakenly believed that HPV can cause AIDS. No significant difference was found between the levels of knowledge of nurses and those of nursing students.

The evaluation of attitudes toward HPV vaccination and the role of nurses highlighted both positive perceptions and potential areas for improvement among participants (see

Table 2). Most participants demonstrated strong support for HPV vaccination, with nurses generally displaying a more favorable attitude than nursing students. For example, nurses were more likely to support vaccinating men to protect against HPV-related consequences, with a mean score of 4.6 ± 0.4 compared with 4.1 ± 0.2 for nursing students (p = 0.03). However, nursing students exhibited slightly more favorable attitudes towards the role of nurses in HPV vaccination, such as recommending the vaccine (mean score: 4.5 ± 0.4 for nursing students vs. 4.3 ± 0.5 for nurses) and addressing negative opinions about the vaccine (mean score: 4.4 ± 0.5 for nursing students vs. 4.2 ± 0.6 for nurses). Despite these differences, none were statistically significant, with p values of 0.27 and 0.24, respectively. Nurses expressed slightly higher trust in the national vaccination program, with a mean score of 4.5 ± 0.5 compared with 4.3 ± 0.6 for nursing students; however, this difference was not significant (p = 0.22). These findings suggest that while both groups generally hold positive attitudes, there are subtle variations, particularly in areas related to the role of nurses in HPV vaccination and trust in the national vaccination program. However, no significant differences were found between the overall attitudes of nurses and those of nursing students.

Several factors were found to predict a positive attitude toward HPV vaccination, as indicated by the logistic regression model (see

Table 3). Participants who identified as secular or traditional were significantly more likely to have a positive attitude towards HPV vaccination compared to those who identified as religious or Ultra-Orthodox Jewish (OR = 2.45, 95% CI: 1.52 – 3.97, p < 0.001). Additionally, those working in community settings demonstrated a higher likelihood of having a positive attitude than those in other workplaces (OR = 2.98, 95% CI: 1.84 – 4.85, p < 0.001). Higher levels of knowledge about HPV and its vaccine were also strongly associated with a positive attitude (OR = 3.35, 95% CI: 2.10 – 5.35, p < 0.001).

Factors such as gender, marital status, nationality, and years of experience in nursing were not significantly associated with positive attitudes towards HPV vaccination, although some trends were observed. Specifically, participants from non-Jewish backgrounds showed a slight, non-significant decrease in positive attitudes compared with Jewish participants. Additionally, those with more years of nursing experience were slightly more likely to have a positive attitude, but this trend was not statistically significant.

4. Discussion

The findings from this study provide valuable insights into the knowledge and attitudes of Israeli nurses and nursing students towards HPV and its associated vaccine. Despite the critical role that nurses play in patient education and vaccine advocacy, our results reveal significant knowledge gaps that could hinder their effectiveness in promoting HPV vaccination. Specifically, misconceptions were identified regarding the vaccine’s ability to cure existing HPV infections, the belief that the vaccine is administered in a single dose, and confusion about the full scope of the impact of HPV, including its transmission and the range of cancers it can cause.

These findings are consistent with those of previous studies conducted in various countries, such as the USA, the UK, and China, where knowledge deficits among nurses were similarly noted. For example, in the USA, school nurses have been increasingly recognized as pivotal in the HPV immunization campaign, emphasizing the importance of their role in educating youth about the vaccine's benefits (30). However, similar to our findings, studies in other regions have highlighted the need for improved literacy among nurses concerning HPV-related issues. For example, research in the UK revealed that while primary care practice nurses generally possessed adequate knowledge, a significant minority still harbored fundamental misconceptions about HPV and its vaccine (31). This is echoed by findings in China, where a substantial proportion of nurses were unaware of critical aspects of HPV and its potential consequences (32).

The study by Runngren et al. (2022) on Swedish school nurses provides further context for these findings by exploring the experiences of nurses who are directly involved in administering HPV vaccines. The study highlights the delicate balance these nurses must strike between maintaining a neutral stance and actively promoting the vaccine to increase uptake. This balance is often influenced by nurses' own knowledge and the official guidelines they follow. The study also underscores the ethical dilemmas nurses face, particularly when their professional obligation to increase vaccination rates conflicts with the need to respect patient autonomy. These dilemmas can be exacerbated by a lack of clear guidelines and adequate training, which can lead to inconsistencies in how nurses communicate the importance of the HPV vaccine to their patients (33).

Our study reveals the significant impact of cultural, religious, and social beliefs on attitudes towards HPV vaccination, with secular or traditional participants showing more positive attitudes compared to those identifying as religious or Jewish Ultra-Orthodox. This finding aligns with broader research indicating that such beliefs can heavily influence health behaviors, including vaccination (34). In religious communities, concerns about the vaccine’s association with sexual activity may lead to hesitancy or refusal, driven by fears that it could be perceived as endorsing premarital sexual activity, conflicting with moral or religious values (35,36). In a multicultural and religiously diverse society such as Israel, these insights highlight the need for culturally sensitive public health campaigns that are carefully tailored to address the specific concerns and beliefs of different communities to effectively promote HPV vaccination (28).

Moreover, the study identified a significant association between workplace setting and attitudes towards HPV vaccination. Participants working in community settings were more likely to have positive attitudes than those in other workplaces. This likely reflects greater exposure to public health initiatives and a stronger emphasis on preventive care within community health settings. Previous studies have suggested that community-based nurses may be more attuned to the importance of vaccination and preventive measures, which could explain their more favorable attitudes (37,38).

The logistic regression analysis further demonstrated that higher levels of knowledge about HPV and its vaccine are strongly associated with a positive attitude towards HPV vaccination, a finding that is consistent with previous research. Studies across various healthcare settings have repeatedly shown that increased knowledge among healthcare providers is linked to more proactive health behaviors, including vaccine advocacy (39,40). This alignment underscores the critical role of education in shaping healthcare professionals' attitudes and behaviors. These findings suggest that targeted educational programs designed to enhance HPV-related knowledge among nurses and nursing students could significantly improve their effectiveness as advocates for vaccination. By equipping these healthcare providers with accurate information and a deeper understanding of HPV, public health initiatives aimed at increasing vaccine uptake could be more successful, ultimately contributing to a reduction in HPV-related diseases.

4.1. Limitations

While this study provides important insights, it is essential to acknowledge several limitations. First, the study relied on self-reported data, which may be subject to social desirability bias, where participants might respond in a manner that they believe is expected rather than expressing their true beliefs or practices. Second, the cross-sectional design of the study limits our ability to draw causal inferences, capturing attitudes and knowledge at only one point in time. Additionally, the use of convenience sampling via Facebook groups may not fully represent the broader population of Israeli nurses and nursing students, as it only includes those who own and regularly use Facebook, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings.

4.2. Implications for Practice and Future Research

The findings of this study have significant implications for public health practice in Israel. Targeted educational programs that address the specific knowledge gaps identified could enhance the role of nurses and nursing students as advocates for HPV vaccination. Such programs should be culturally sensitive and consider the diverse religious and social backgrounds of the population. Moreover, ongoing research is needed to explore the long-term impact of improved education on vaccination rates and to assess the effectiveness of different educational interventions.

Future research should also focus on longitudinal studies to track changes in knowledge and attitudes over time, particularly as nurses and nursing students are exposed to new information and public health campaigns. Additionally, exploring the impact of specific cultural and religious beliefs on vaccination attitudes could provide deeper insights into how best to tailor public health messages in multicultural societies such as Israel.

4.3. Conclusions

To enhance the effectiveness of nurses and nursing students as advocates for HPV vaccination in Israel, it is crucial to implement targeted educational programs that address the specific knowledge gaps identified in this study. These programs should be designed with cultural sensitivity, taking into account the diverse religious and social backgrounds of the population to ensure that they resonate with all communities. By improving healthcare providers' knowledge of HPV and its vaccine, these initiatives can empower them to advocate more effectively for vaccination, ultimately increasing vaccine uptake and reducing the incidence of HPV-related diseases. Additionally, public health campaigns should focus on clear communication strategies that correct common misconceptions and emphasize the importance of preventive care, particularly in community settings where nurses are more frequently involved in public health initiatives. These practical steps can significantly strengthen the role of nurses in promoting HPV vaccination and contribute to better health outcomes across Israel.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.G., N.B. and A.B.; Data curation, N.B.; Formal analysis, Y.G., N.B.; Methodology, Y.G., N.B. and A.B.; Visualization, Y.G., N.B. and A.B.; Writing—original draft, Y.G., N.B. and A.B.; Writing—review & editing, Y.G., N.B. and A.B.; Supervision, Y.G. and A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of XXX University, approval code: AU-HEA-YG-20230111.

Informed consent statement

Written informed consent was obtained electronically from all participants before they accessed the questionnaire.

Data availability statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are included within the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Graff AH, Frasier LD. Viral and parasitic sexually transmitted infections in children [Internet]. Child Abuse and Neglect: Diagnosis, Treatment and Evidence - Expert Consult: Online and Print. Elsevier Inc.; 2010. 179–185 p. [CrossRef]

- Daniels V, Saxena K, Roberts C, Kothari S, Corman S, Yao L, et al. Impact of reduced human papillomavirus vaccination coverage rates due to COVID-19 in the United States: A model based analysis. Vaccine [Internet]. 2021, 39, 2731–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanni P, Faivre P, Lopalco PL, Joura EA, Bergroth T, Varga S, et al. The status of human papillomavirus vaccination recommendation, funding, and coverage in WHO Europe countries (2018–2019). Expert Rev Vaccines [Internet]. 2020, 19, 1073–1083. [CrossRef]

- Shavit O, Raz R, Stein M, Chodick G, Schejter E, Ben-David Y, et al. Evaluating the epidemiology and morbidity burden associated with human papillomavirus in Israel: Accounting for CIN1 and genital warts in addition to CIN2/3 and cervical cancer. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2012, 10, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavit O, Roura E, Barchana M, Diaz M, Bornstein J. Burden of Human Papillomavirus Infection and Related Diseases in Israel. Vaccine [Internet]. 2013, 31 (SUPPL.8), 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman BR, Aragones A. Epidemiology and incidence of HPV-related cancers of the head and neck. J Surg Oncol. 2021, 124, 920–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asia WHORO for S-E. Accelerating the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem: Towards achieving 90–70–90 targets by 2030 [Internet]. New Delhi PP - New Delhi: World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2022. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/361138.

- Charde SH, Warbhe RA. Human Papillomavirus Prevention by Vaccination: A Review Article. Cureus. 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz LE, Schiller JT. Human Papillomavirus Vaccines. J Infect Dis. 2021, 224 (Suppl 4), S367–78. [Google Scholar]

- Wortsman J, Glaser Chodik N, Chodick G. Correlations of HPV vaccine uptake among eight-grade students in Israel: the importance of ethnicity and level of religious observance. Women Heal [Internet]. 2023, 63, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni L, Diaz M, Barrionuevo-Rosas L, Herrero R, Bray F, Bosch FX, et al. Global estimates of human papillomavirus vaccination coverage by region and income level: A pooled analysis. Lancet Glob Heal. 2016, 4, e453–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie M, Lavie I, Laskov I, Cohen A, Grisaru D, Grisaru-Soen G, et al. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Uptake in Israel. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Shahbari NAE, Gesser-Edelsburg A, Davidovitch N, Brammli-Greenberg S, Grifat R, Mesch GS. Factors associated with seasonal influenza and HPV vaccination uptake among different ethnic groups in Arab and Jewish society in Israel. Int J Equity Health. 2021, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibli R, Rishpon S. The factors associated with maternal consent to human papillomavirus vaccination among adolescents in Israel. Hum Vaccines Immunother [Internet]. 2019, 15, 3009–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher WA, Laniado H, Shoval H, Hakim M, Bornstein J. Barriers to Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Acceptability in Israel. Vaccine [Internet]. 2013, 31 (SUPPL.8), 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbari NAE, Gesser-Edelsburg A, Mesch GS. Case of paradoxical cultural sensitivity: Mixed method study of web-based health informational materials about the human papillomavirus vaccine in Israel. J Med Internet Res. 2019, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin Y, Hu Z, Alias H, Wong LP. The role of nurses as human papillomavirus vaccination advocates in China: perception from nursing students. Hum Vaccines Immunother [Internet]. 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilandika A, Pandin MGR, Yusuf A. The roles of nurses in supporting health literacy: a scoping review. Front Public Heal. 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Khamisy-Farah R, Adawi M, Jeries-Ghantous H, Bornstein J, Farah R, Bragazzi NL, et al. Knowledge of human papillomavirus (HPV), attitudes and practices towards anti-HPV vaccination among Israeli pediatricians, gynecologists, and internal medicine doctors: Development and validation of an ad hoc questionnaire. Vaccines. 2019, 7. [CrossRef]

- Thaker J, Albers AN, Newcomer SR. Nurses’ perceptions, experiences, and practices regarding human papillomavirus vaccination: results from a cross-sectional survey in Montana. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murciano-Gamborino C, Diez-Domingo J, Fons-Martinez J. Healthcare Professionals’ Perspectives on HPV Recommendations: Themes of Interest to Different Population Groups and Strategies for Approaching Them. Vaccines. 2024, 12, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakonti G, Kyprianidou M, Toumbis G, Giannakou K. Knowledge and attitudes toward vaccination among nurses and midwives in Cyprus: A cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Knowl. 2022, 33, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamai RG, Ayissi CA, Oduwo GO, Perlman S, Welty E, Welty T, et al. Awareness, knowledge and beliefs about HPV, cervical cancer and HPV vaccines among nurses in Cameroon: An exploratory study. Int J Nurs Stud [Internet]. 2013, 50, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc Z, Ozdes EK, Topatan S, Cinarli T, Sener A, Danaci E, et al. The Impact of Education About Cervical Cancer and Human Papillomavirus on Women’s Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors and Beliefs Using the PRECEDE Educational Model. CANCER Nurs. 2019, 42, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Açıkgöz S, Göl İ. The effect of theoretical and student-centered interactive education on intern nursing students’ knowledge and consideration regarding human papillomavirus and its vaccine in Turkey: A repeated measures design. Belitung Nurs J. 2023, 9, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanueva S, Mosteiro-Miguéns DG, Domínguez-Martís EM, López-Ares D, Novío S. Knowledge, attitudes, and intentions towards human papillomavirus vaccination among nursing students in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019, 16. [CrossRef]

- Khamisy-Farah R, Endrawis M, Odeh M, Tuma R, Riccò M, Chirico F, et al. Knowledge of Human Papillomavirus (HPV), Attitudes, and Practices Towards Anti-HPV Vaccination Among Israeli Nurses. J Cancer Educ [Internet]. 2023, 38, 1391–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gendler, Y. Development and Appraisal of a Web-Based Decision Aid for HPV Vaccination for Young Adults and Parents of Children in Israel — A Quasi-Experimental Study, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gendler Y, Blau A. Exploring Cultural and Religious Effects on HPV Vaccination Decision Making Using a Web-Based Decision Aid: A Quasi-experimental Study. Med Decis Mak. 2024, 44, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes D, Visker J, Cox C, Forsyth E, Woolman K. Public Health and School Nurses’ Perceptions of Barriers to HPV Vaccination in Missouri. J Community Health Nurs [Internet]. 2017, 34, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel H, Austin-Smith K, Sherman SM, Tincello D, Moss EL. Knowledge, attitudes and awareness of the human papillomavirus amongst primary care practice nurses: An evaluation of current training in England. J Public Heal (United Kingdom). 2017, 39, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu J, He M, Pu Y, Liu Z, Le L, Wang H, et al. Knowledge about Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer Prevention among Intern Nurses. Asia-Pacific J Oncol Nurs. 2021, 8, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runngren E, Eriksson M, Blomberg K. Balancing Between Being Proactive and Neutral: School Nurses’ Experiences of Offering Human Papilloma Virus Vaccination to Girls. J Sch Nurs. 2022, 38, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson A, Spitzer S, Gorelik Y, Edelstein M. Barriers and enablers to vaccination in the ultra-orthodox Jewish population: a systematic review. Front Public Heal. 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Zach R, Bentwich ME. Reasons for and insights about HPV vaccination refusal among ultra-Orthodox Jewish mothers. Dev World Bioeth. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Velan B, Yadgar Y. On the implications of desexualizing vaccines against sexually transmitted diseases: Health policy challenges in a multicultural society. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2017, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou F, Nursing PH, Drakopoulou M, Kavga-paltoglou A. 22.Economou.Pdf Rool. 2022, 15, 1839–1848.

- Pakai A, Mihály-Vajda R, Horváthné ZK, Gabara KS, Bogdánné EB, Oláh A, et al. Predicting cervical screening and HPV vaccination attendance of Roma women in Hungary: community nurse contribution is key. BMC Nurs [Internet]. 2022, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilkey MB, McRee AL. Provider communication about HPV vaccination: A systematic review. Hum Vaccines Immunother [Internet]. 2016, 12, 1454–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efua Sackey M, Markey K, Grealish A. Healthcare professional’s promotional strategies in improving Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination uptake in adolescents: A systematic review. Vaccine [Internet]. 2022, 40, 2656–2666, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X22003656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).