1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are among the leading causes of morbidity worldwide [

1], including in Brazil [

2,

3]. Moreover, the number of individuals with ischemic heart diseases is growing exponentially; in Brazil, it has more than doubled in the past 20 years, reaching 4 million in 2019 [

2]. Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is an outpatient model of secondary preventive care to mitigate this burden. CR participation reduces CVD morbidity and mortality by 20% [

4]. Major cardiac practice guidelines [

5] as well as the Brazilian Guidelines for CR [

6] highlight the importance of this intervention in the care of people living with CVDs [

5]. CR is however under-utilized, particularly in lower-resource settings [7-9].

Health system, referring provider, program, and patient level barriers are at play [

10,

11]. Given patient’s CR access is dependent upon provider referral, provider-related factors are key. Indeed, studies evaluating patient-level barriers to CR participation – including in Brazil – have identified provider-related factors, such as physicians not encouraging them [12-15]. A systematic review of physician factors associated with CR referral identified 17 studies – none had been undertaken in low-resource settings such as South America [

16]. Since, there have been some qualitative studies on provider-related barriers to CR referral in low-resource settings [

17,

18], but little that used a validated quantitative measure to our knowledge [

19].

The Provider Attitudes toward Cardiac Rehabilitation and Referral (PACRR) scale was developed to enable reliable and valid assessment of these [

20], given how instrumental referral and encouragement are to patient access to these life-saving programs [

21]. It was developed in a high-resource setting, and has only been administered once in a low-resource setting (Western-Pacific) [

22]. It is likely that some adaptation to the PACRR is needed for low-resource settings given differences in CR context. For instance, availability of programs to which providers can refer is limited [

7]; accordingly, automatic referral processes are not used to our knowledge [

23,

24]. It is also a likely consequence that many physicians are not familiar with CR program locations and benefits [

25]. Moreover, CR programs are more often privately-run [

26], and patients have more barriers to attending (e.g., transportation and program costs) [

27]. So a better understanding of physician attitudes in these contexts is needed to support change. Therefore, the objectives of the present study were to: (1a) translate and culturally adapt a Brazilian-Portuguese version of the PACRR Scale (PACRR-P), (b) establish its’ measurement properties and, (2) characterize the main factors impacting physician CR referral in a low-resource, Latin American context for the first time.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Procedures

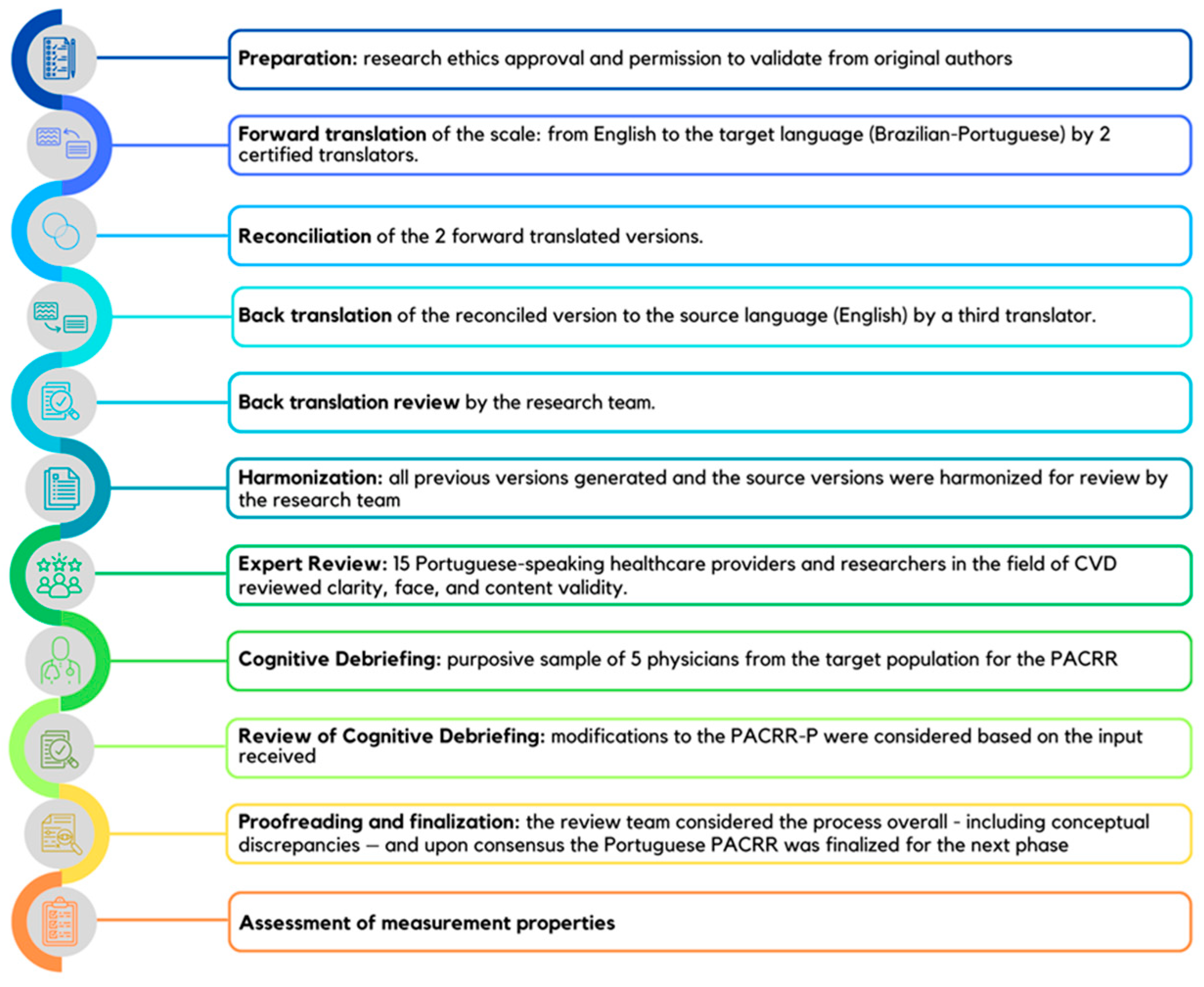

This was a multi-method study with 2 phases: (1) translation and cultural adaptation following best practices [

28], followed by (2) a cross-sectional survey of physicians to assess measurement properties and establish top factors impacting referral (

Figure 1). For the latter, reliability (internal), as well as several forms of validity were assessed: face, content, cross-cultural, convergent and criterion. Data was collected from November 2022 to March 2023.

2.2. Materials

The PACRR scale was develop by Ghisi & Grace (2019) to assess attitudes, beliefs and other factors that impact providers’ CR referral practices [

20]. It was developed following an extensive literature review and input from health care professionals with expertise in CR. The PACRR comprises 19 items scored on a Likert-type scale, with response options ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Five items are reverse scored to mitigate acquiescence bias. Higher scores reflect more positive attitudes toward CR and referral. A final open-ended item asks providers to list the most important factors that influence their decision to refer a patient to CR. The PACRR comprises four subscales, namely: referral norms, preference to manage patients independently of CR, perceptions of program quality, and referral processes. Internal reliability and validity of the scale were established [

19]. It has been administered in a low-resource setting [

20]. Although many providers globally train and/or are fluent in English, a Simplified Chinese translation has been validated [

29].

2.3. Translation and Cultural Adaptation

The Professional Society for Health Economic and Outcomes Research (ISPOR)’s 10 steps were followed, as per Fig 1 [

28]. With regard to the first step (preparation), study approval was secured from the Sao Paulo State University’s Research Ethics Board (CAAE:60124622.5.0000.5402). Also, permission to validate a Portuguese version of the PACRR was obtained, and authors of the original PACRR developmental study were invited to be part of this project. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants for inclusion in the study.

Forward translation of the scale from English to the target language (Portuguese) was performed by two certified translators fluent in both languages independently. Translators were first provided a clear explanation of the basic concepts related to the scale, with the intention that the translations would capture the conceptual meaning of the questions rather than being a literal translation. In order to resolve discrepancies between the forward translations, they were then reconciled into a single forward translation, which was then back-translated to the source language (English) by a third certified translator. This back-translated version was then reviewed by the research team. As an additional quality control step to ensure that all discrepancies were considered, all previously-generated and the source versions were harmonized for review by the research team.

Next, a review committee comprised of 15 Portuguese-speaking healthcare providers and researchers in the field of CVD (4 cardiologists, 1 general practitioner, 1 nurse, and 9 physical therapists) was asked to provide input on the translation. This included rate the clarity of each item (Likert-type scale ranging from 1=very unclear to 5=very clear). They were also asked to comment in an open-ended manner on face as well as content validity (including any items that should be added or deleted) and the cross-cultural relevance of the items. Modifications were considered based on the initial input, and the experts was asked to review the revised survey similarly, including rating of clarity; this was to continue until ratings were satisfactory and no further modifications to the scale were needed.

Then, cognitive debriefing of the scale was performed with a purposive sample (i.e., working in the public and/or private sector; generalists, specialists, and subspecialists; junior and senior) of physicians from the target population for the PACRR (i.e., treats patients indicated for CR and that are eligible to refer patients to CR). In line with best practices recommended by ISPOR [

28], 5 participants were sought. They were provided the scale and asked to rate clarity of each item as above and to provide open-ended input on face, content, as well as cross-cultural validity online. Modifications to the PACRR-P were considered based on the input received.

Finally, the review team considered the process overall, including conceptual discrepancies. Upon consensus, the Portuguese version of the PACRR was ready for assessment of measurement properties.

2.4. Assessment of Measurement Properties - Participants

The only healthcare professional type that can refer patients to CR in Brazil are physicians, and hence a convenience sample of such physicians was sought. Portuguese-speaking physicians who treat patients indicated for CR (e.g., cardiologists, general practitioners) working in Brazil were eligible to participate. Respondents who answered less than 80% of the PACRR items were excluded.

2.5. Assessment of Measurement Properties - Procedure

Physicians were recruited through social media accounts from the UNESP’s School of Technology and Sciences Research Lab and by direct emails to eligible physicians at universities located in the state of São Paulo, Brazil (where the density of CR is highest, such that there are programs to which physicians can refer their patients) [

7]. Recruitment occurred between October 2022 and February 2023. To optimize the survey response rate, we incorporated components of Dillman’s Tailored Design Method [

30]. Informed consent was obtained online prior to initiating the survey. The online questionnaire was administered using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap).

2.6. Assessment of Measurement Properties – Measures

Participant’s sociodemographic and occupational characteristics were assessed via self-report. Respondents were also asked about referral practices to investigate criterion validity. Items queried whether they generally refer to CR (yes/no). They were also asked to estimate the percentage of indicated patients they refer to CR per month.

To assess convergent validity, the Recommending Cardiac Rehabilitation Scale (ReCaRe) was also administered [

31]. It is comprised of 17 items assessing health professionals’ attitudes, values, and beliefs regarding CR referral. While not synonymous with PACRR given some differences in focus (e.g., perceived severity and susceptibility subscale differs from PACRR), we are not aware of any other validated scales in this area [

20]. Items are rated on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree. Scores range from 17-85; higher scores denote items have greater influence on decision-making when recommending CR.

2.7. Assessment of Measurement Properties - Data Analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 28 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the assessment of measurement properties. The level of significance for all tests was set at 0.05.

A mean total PACRR score was computed. Subscale scores were also computed based on the original version [

20]. Internal consistency was determined by calculating Cronbach's

α; a

value >0.70 was considered acceptable [

32,

33]. Finally, to assess convergent validity – given that the data for both PACRR and RECARE are normally distributed – , differences in PACRR item scores by CR referral practices as well as subscale scores by ReCaRe total scores were tested using Student's independent samples

t-tests and Pearson’s correlations, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Translation and Cultural Adaptation

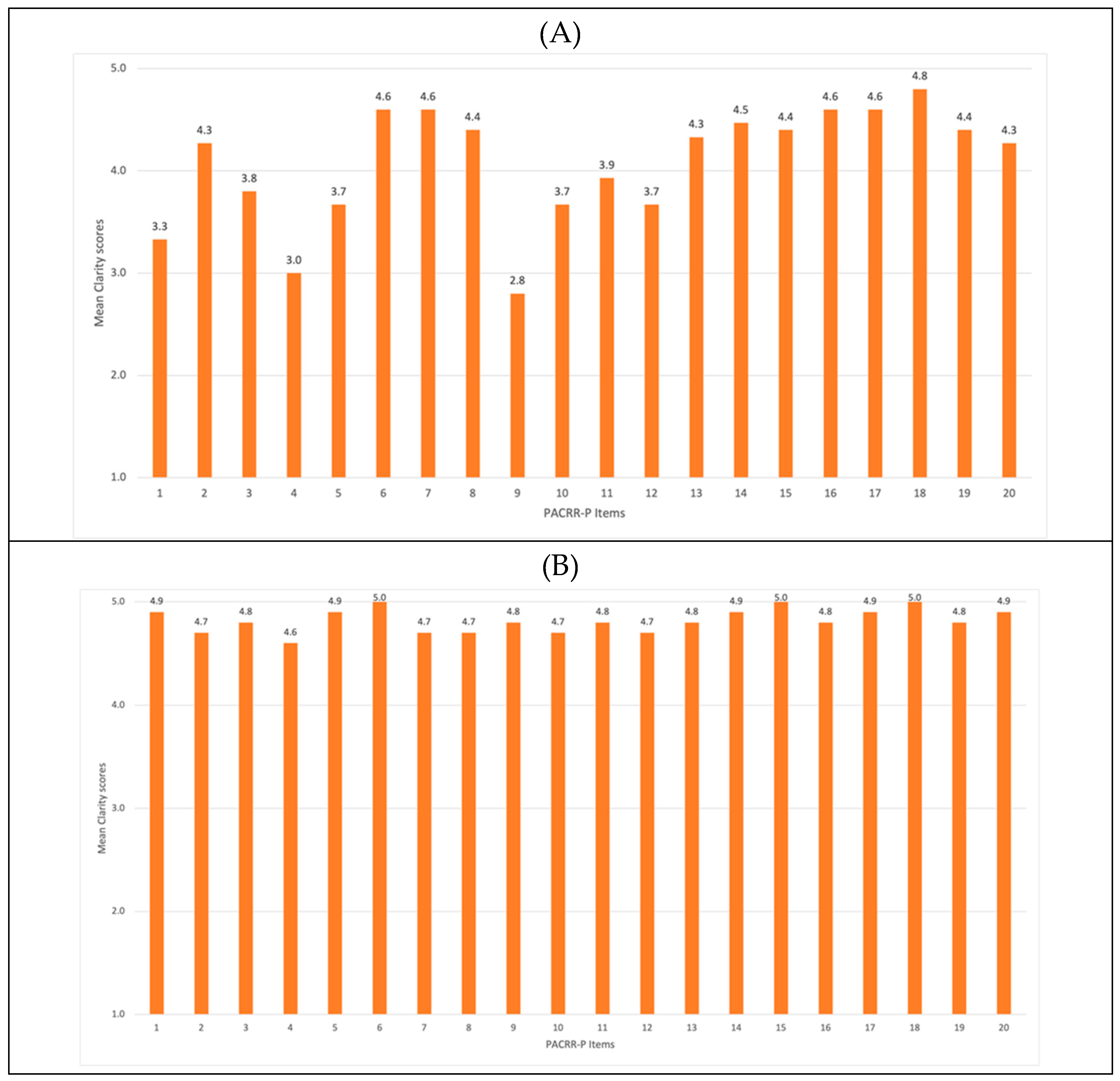

Following translations, reconciliation, and harmonization of PACRR to Portuguese as per Fig 1, the review committee deemed all 19 items in the original PACRR version applicable to the Brazilian context and had none to add. Clarity ratings of each item in round 1 are shown in

Figure 2-A and in round 2 in

Figure 2-B. As displayed, clarity ratings ranged from 2.8-4.8/5 (mean 4.1±0.6). Based on the qualitative input as well, minor wording changes were made to increase clarity of items 1-16 and 19. For the second round of ratings from the review committee, clarity ratings ranged from 4.7-5.0/5 (mean 4.8±0.1); the scale was deemed ready for the next stage of testing.

Based on the cognitive debriefing of the scale performed with 5 physicians, clarity of items ranged from 4.6 to 5.0 /5 (mean 4.8±0.1). None of the respondents selected the “not applicable” option for any item. Therefore, no further changes were made.

3.2. Assessment of Measurement Properties of the PACRR-P

Other than the social media posting, the email invitation to complete the online survey was sent to 590 physicians (330 of them cardiologists). Ultimately 44 (7.5%) completed the PACRR-P. Their characteristics are shown in

Table 1; responses were from the two Brazilian regions with the most CR programs available in the country [

7].

Table 2 displays the PACRR-P scores by item and subscale. It also displays the proportion of respondents that rated each item inapplicable, which ranged from 0-14% (mean=5.0%). This further supports content validity of the PACRR-P. The Cronbach’s alpha for the overall scale was 0.71, supporting the internal consistency of the scale.

Half of physicians reported generally referring their patients to CR (

Table 2), generally referring 27.8±30.5% of their patients. In regards to criterion validity, referral was significantly associated with PACRR-P items 3, 7, 8 and 10 (p<.05; trend for items 6, 9, 15;

Table 2). Finally, the “perception of program quality” PACRR-P subscale was significantly correlated with total ReCaRe scores (r=0.31, p<.05), supporting convergent validity.

3.3. Brazilian Physician’s Attitudes toward Cardiac Rehabilitation and Referral

Items with the highest scores (i.e., the most important factors) were: not being familiar with CR sites outside their geographic area, not having a standard referral form for CR, not having an allied health professional fill out referral forms on their behalf, lack of standard institutional processes to support referral (e.g., automatic referral) and non-referral being normative. Items with the lowest scores (i.e., the least important factors) were related to being skeptical about the benefits of CR and having had a bad experience with a CR program.

In regard to the open-ended responses to question 20 about “the most important factors that affect your referral of patients to CR”, 34 valid responses were coded. Most respondents reported not knowing about CR programs in their area or outside their geographic area, which aligns with high rated PACRR-P items, supporting the content and face validity of the scale.

Other main factors reported to affect CR referral were cost, access and availability of CR programs, followed by perceptions of patient motivation. Based on this, several changes were made to finalize the PACRR-P. Specifically, item 17 was revised to also include cost concerns, item 15 was revised to reflect amotivation in any patients (not only females), and item 19 which was considered least applicable was revised to “Patients have too many barriers to attend CR, so there is no point in referring them” (Appendix A).

4. Discussion

Despite well-established benefits, physician referral to CR is low in Brazil [

6]. With the use of PACRR-P, factors that impede referral could be understood, and corresponding strategies to mitigate them can be developed and implemented, so that ultimately more patients can access CR. Following best practices, this study has rigorously translated and cross-culturally adapted a Portuguese version of the PACRR scale. Through this process, all 19 items of the scale were retained, with revisions made to 18 items to improve clarity or ensure all major factors were assessed. Face, content, and cross-cultural validity were supported. Measurement properties were tested; internal consistency as well as convergent and criterion validity were also confirmed.

With regard to the latter point, criterion validity of the PACRR was not as robust as was evidenced in three North American cohorts [

20]. This could be due to the smaller sample size in this study, but also is likely related to the low-resource context. With a dearth of programs to which physicians can refer, attitudes and perceptions as well as referral processes are less relevant to CR referral practices. While some revisions were made to PACRR (including to the English version; see:

https://sgrace.info.yorku.ca/cr-barriers-scale/pacrr/ for PACRR-R) to ensure applicability to low-resource settings, application of the PACRR in a given region should likely be reserved until structural issues such as program availability are addressed (i.e., applicable for use in settings with a higher density of CR than Brazil) [

34].

The most strongly-endorsed attitudes impeding referral were being familiar with the location of CR sites, having a standard CR referral form and lack of automatic referral processes.

Total PACRR-P scores were lower than the mean in the original English validation (3.7±0.4) [

20], indicative of less positive attitudes toward CR and referral in the current low-resource sample. Otherwise, results from this study are generally consistent with other qualitative and quantitative studies assessing factors affecting physician CR referral, in low and high-resource settings alike. In our review of physician factors affecting referral [

16], geographic issues, perceptions of patient motivation, patient clinical status and insurance coverage / cost were paramount. All of these were raised herein. In the only other administration of the PACRR in a low-resource setting (Philippines) [

22], again the main factors were concordant with the current findings, namely: costs, geographic issues / program accessibility, quality of the CR program, patient preferences / motivation, as well as financial incentives for the referral, lack of standard referral forms, and preference to manage secondary prevention of patient independent of CR. As described above, indeed some revisions were made to the PACRR to render it more applicable to low-resource contexts through this study.

With regard to implications, the PACRR-P can be administered to understand low CR referral rates and create strategies to mitigate them. Clinical associations, policy-makers, and institutions could administer this tool to their cardiac physicians and work with them to overcome referral barriers. There is great need to augment funded CR capacity, so that physicians have a place to refer their patients (and it can become normative), close to their home [

7,

35]. With more programs, automatic referral could be instituted where referral processes are identified by physicians as barriers. And acute cardiac care providers need to be educated on the benefits of CR, which patients should be referred (including education about valid and invalid clinical exclusions) [

36] and how to refer them, where programs are located and how to encourage patients to attend. Such a course is freely available online in Portuguese (

https://globalcardiacrehab.com/CR-Utilization), among other languages. It has been shown to increase CR knowledge, referral self-efficacy, and patient encouragement among providers [

37,

38]. This could be broadly disseminated to non-referring physicians in an effort to increase CR utilization.

Caution is warranted when interpreting these results. Generalizability is limited due to small sample size. This is due to the poor response rate to online surveys, particularly by physicians [

39]. This also raises the possibility of selection bias. To optimize the survey response rate, we incorporated components of Dillman’s Tailored Design Method [

30], including multiple contacts, personalized mailings and a short questionnaire. In a review of physician response to surveys [

40], the demographic characteristics of late respondents (considered a proxy for non-respondents) were similar to the characteristics of respondents to the first mailing. Moreover, physicians as a group are more homogeneous than the general population with regard to knowledge, training, attitudes and behavior, suggesting that non-response bias may not be as crucial in physician surveys as with the general population [

39].

Generalizability to other countries where Portuguese is a common language is also unknown, particularly to jurisdictions with different healthcare systems, and high-resource settings. This concern is tempered however by the fact that the original scale was applicable to another health system and was validated in a high-income country, and only minor wording changes were made in the translation and adaptation process.

Relatedly, future studies should focus on confirming the measurement properties of the finalized scale and evaluating others (i.e., test-retest reliability, construct validity, responsiveness, interpretability, and hypothesis-testing) [

41]. Criterion validity was assessed herein through physician report of referral, but should be tested against verified referral. Assessment of factor structure is now warranted given some changes were made to items, and the low-resource context. Personal communication (May 17, 2022) from the authors of the Chinese version (PACRR-C) stated they removed item 4 (reimbursement for referral) as it was not applicable in the local context; all other items were retained, with many wording revisions to optimize cultural validity as with the Portuguese translation. Their factor analysis and structural equation model supported the four-factor structure of the PACRR in this low-resource setting. In addition, ways to overcome identified factors hampering provider referral such as those identified above should be tested in terms of how they impact referring physician attitudes.

5. Conclusions

Through this study, a Portuguese version of the PACRR applicable for use in low-resource settings was developed, and while more research is needed, measurement properties were preliminarily supported as favorable. The main barriers to physician CR referral identified -- familiarity with the location of CR sites, standardizing CR referral forms and implementing automatic referral processes – are likely surmountable with provider education, CR program acceptance of discharge summaries or coordination of referral paperwork, and referral process improvements.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file: The Portuguese Version of the Provider Attitudes Toward Cardiac Rehabilitation & Referral Scale - Revised Atitudes Médicas em Relação à Reabilitação Cardíaca e Encaminhamento para os Programas (PACRR-P-R).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: MMAC, SG, GLMG; Data curation: MMAC, LCMV, CT, MJLL, MRAC; Formal analysis: MMAC, SG, GLMG; Methodology: MMAC, SG, GLMG; Investigation: MMAC, LCMV; Project Administration: MMAC, GLMG; Resources: MMAC; Writing Original Draft: MMAC, SG, GLMG; Review Writing: MMAC, LCMV, CT, MJLL, MRAC.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sao Paulo State University (protocol code CAAE:60124622.5.0000.5402, date of approval: October 7, 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request. Please contact the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990-2019: Update From the GBD 2019 Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2982–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, G.M.M.D.; Brant, L.C.C.; Polanczyk, C.A.; et al. Estatística Cardiovascular Statistics Brazil 2021. Braz. Arch. Cardiol. 2022, 118, 115–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.G.; Gotto, J.R.F.; Spaziani, A.O.; et al. [Diseases of the circulatory system in Brazil according to Datasus data: a study from 2013 to 2018]. Braz. J. Health Rev. 2020, 3, 832–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibben, G.; Faulkner, J.; Oldridge, N.; et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 11, CD001800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knuuti, J.; Wijns, W.; Saraste, A.; et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 407–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, T.; Milani, M.; Ferraz, A.S.; et al. Brazilian Cardiovascular Rehabilitation Guideline - 2020. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2020, 114, 943–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britto, R.R.; Supervia, M.; Turk-Adawi, K.; et al. Cardiac rehabilitation availability and delivery in Brazil: a comparison to other upper middle-income countries. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2020, 24, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, R.; Milani, M.; Abreu, A. What is the Current Scenario of Cardiac Rehabilitation in Brazil and Portugal? Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2022, 118, 858–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, S.L.; Kotseva, K.; Whooley, M.A. Cardiac Rehabilitation: Under-Utilized Globally. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2021, 23, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, J.; Sindone, A.P.; Thompson, D.R.; Hancock, K.; Chang, E.; Davidson, P. Barriers to participation in and adherence to cardiac rehabilitation programs: a critical literature review. Prog. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2002, 17, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, C.; Ghisi, G.L.M.; Davis, E.; Grace, S.L. Cardiac Rehabilitation Barriers Scale (CRBS). In International Handbook of Behavioral Health Assessment; Springer: United States, 2023; Available online: https://link.springer.com/referencework/10.1007/978-3-030-89738-3 (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Ghisi, G.L.; Santos, R.Z.; Schveitzer, V.; et al. Development and validation of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the Cardiac Rehabilitation Barriers Scale. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2012, 98, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghisi, G.L.; dos Santos, R.Z.; Aranha, E.E.; et al. Perceptions of barriers to cardiac rehabilitation use in Brazil. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2013, 9, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, G.L.B.; Cruz, M.M.A.D.; Ricci-Vitor, A.L.; Silva, P.F.D.; Grace, S.L.; Vanderlei, L.C.M. Publicly versus privately funded cardiac rehabilitation: access and adherence barriers. A cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2022, 140, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sérvio, T.C.; Britto, R.R.; de Melo Ghisi, G.L.; et al. Barriers to cardiac rehabilitation delivery in a low-resource setting from the perspective of healthcare administrators, rehabilitation providers, and cardiac patients. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghisi, G.L.; Polyzotis, P.; Oh, P.; Pakosh, M.; Grace, S.L. Physician factors affecting cardiac rehabilitation referral and patient enrollment: a systematic review. Clin. Cardiol. 2013, 36, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Grace, S.L.; Ding, B.; Liang, L.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y. Cardiac Rehabilitation Perceptions Among Healthcare Providers in China: A Mixed-Methods Study. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2021, 27, 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanbari-Firoozabadi, M.; Mirzaei, M.; Nasiriani, K.; et al. Cardiac Specialists' Perspectives on Barriers to Cardiac Rehabilitation Referral and Participation in a Low-Resource Setting. Rehabil. Process Outcome 2020, 9, 1179572720936648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisi, G.L.M.; Contractor, A.; Abhyankar, M.; Syed, A.; Grace, S.L. Cardiac rehabilitation knowledge, awareness, and practice among cardiologists in India. Indian Heart J. 2018, 70, 753–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisi, G.L.M.; Grace, S.L. Validation of the Physician Attitudes toward Cardiac Rehabilitation and Referral (PACRR) Scale. Heart Lung Circ. 2019, 28, 1218–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace, S.L.; Gravely-Witte, S.; Brual, J.; et al. Contribution of patient and physician factors to cardiac rehabilitation enrollment: A prospective multilevel study. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prev. Rehabil. 2008, 15, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenza, L.R.; Gacrama, E.N.; Tan, K.; Quito, B.J.; Ebba, E. Physician factors affecting cardiac rehabilitation referral among cardiac specialists: The Philippine Heart Center CRAVE study. J. Clin. Prev. Cardiol. 2016, 5, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravely-Witte, S.; Leung, Y.W.; Nariani, R.; et al. Effects of cardiac rehabilitation referral strategies on referral and enrollment rates. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2010, 7, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supervia, M.; Turk-Adawi, K.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; et al. Nature of cardiac rehabilitation around the globe. EClinicalMedicine 2019, 13, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.S.; Dalal, H.M.; McDonagh, S.T.J. The role of cardiac rehabilitation in improving cardiovascular outcomes. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2022, 19, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesah, E.; Turk-Adawi, K.; Supervia, M.; et al. Cardiac rehabilitation delivery in low/middle-income countries. Heart 2019, 105, 1806–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.; Fredericks, S.; Jones, I.; et al. Global perspectives on heart disease rehabilitation and secondary prevention: A scientific statement from the Association of Cardiovascular Nursing and Allied Professions (ACNAP), European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC), and International Council of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (ICCPR). Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 2515–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, D.; Grove, A.; Martin, M.; et al. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: Report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value Health 2005, 8, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PACRR Chinese (PACRR-C) 2022. Available online: https://sgrace.info.yorku.ca/cr-barriers-scale/pacrr/ (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 3rd ed.; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 263–287. [Google Scholar]

- Ski, C.F.; Jones, M.; Astley, C.; et al. Development, piloting, and validation of the Recommending Cardiac Rehabilitation (ReCaRe) instrument. Heart Lung 2019, 48, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 100–120. [Google Scholar]

- Taber, K.S. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk-Adawi, K.; Supervia, M.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; et al. Cardiac rehabilitation availability and density around the globe. EClinicalMedicine 2019, 13, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, A.S.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; Thomas, R.J.; et al. Advocacy for outpatient cardiac rehabilitation globally. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago de Araújo Pio, C.; Beckie, T.M.; Varnfield, M.; et al. Promoting patient utilization of outpatient cardiac rehabilitation: A joint international council and Canadian association of cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation position statement. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2020, 40, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago de Araújo Pio, C.; Gagliardi, A.; Suskin, N.; Ahmad, F.; Grace, S.L. Implementing recommendations for inpatient healthcare provider encouragement of cardiac rehabilitation participation: Development and evaluation of an online course. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heald, F.A.; de Araújo Pio, C.S.; Liu, X.; Theurel, F.R.; Pavy, B.; Grace, S.L. Evaluation of an online course in 5 languages for inpatient cardiac care providers on promoting cardiac rehabilitation: Reach, effects, and satisfaction. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2022, 42, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T.S.; Cadoret, C.A.; Brown, M.L.; et al. Surveying physicians: Do components of the "Total Design Approach" to optimizing survey response rates apply to physicians? Med. Care 2002, 40, 596–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellerman, S.E.; Herold, J. Physician response to surveys: A review of the literature. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2001, 20, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Terwee, C.B.; Patrick, D.L.; et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2010, 63, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).