1. Introduction

The decline in interest rates for several years is worth mentioning. While some researchers have tried to argue that the drop in real interest rates has happened for many centuries, at least there has been a general agreement on the phenomenon of secular stagnation for several decades now, particularly after the IMF Conference of 2013. In this context, several explanations regarding this persistent decline have been put forward by economists, including factors from the demand side, namely, a demand deficit, an ageing population and unfulfilled investment potential. Similarly, some supply-side explanations have also been presented, including a decline in productivity growth rate. These predominant explanations mainly address those economic variables which seem to be externally managed and thus, not under the mandate of monetary policy. Yet, in an important and recent paper [

1,

2], it was found out that 3-day windows around the meetings of their Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) encompass the long-standing decrease in the 10-year treasuries experienced over the recent decades while changes in yields outside these windows are mainly temporary. The finding brings about a key question: in the global dollarised debt markets, do the interest rate policy actions taken by the central banks other than the federal reserve have an explanatory effect on the variations in yields of long-term government bonds as this is the case with the federal reserve, or is it unique to the US federal reserve? Similarly, the decline of real rates of interest that has been noticed in some other countries, and which is reflected in the changes of yields of long government bonds, the result of monetary policies of the FED which opens debates on international monetary policy and the ‘Global Financial Cycle’? In terms of these findings, while supporting the notion that advanced economies are characterized by significant heterogeneity and there are additional complicating factors, such as the use of so-called unconventional monetary policy tools or interventions in foreign exchange markets, it is reasonable to conclude that the federal reserve plays a greater role than other domestic policies in determining the government bond yields in other countries. This, in turn, is consistent with the earlier findings on the World Asset Market (WAM) as mentioned in the earlier paragraphs [

3,

4,

5].

To sum up, this paper contributes to the existing body of research by using a less rigorous but more illuminating methodology in that it employs 3-day monetary policy decision windows overlapping the 10-year government bond yields of several advance economies which includes the decision time of the domestic and the federal reserve. These frames yield movements captured on account of the actions of both central banks and thus support or contest the hypothesis of the global financial cycle. Besides, the empirical design of this research employs an Ordinary Least Squared (OLS) approach to uncover statistically significant covariance relationships. In particular, this paper aims to combine the theoretical framework concerning the global financial cycle and the concept of secular stagnation, making this work novel among the others.

The study is as follows; similar papers are shown in the following section. The empirical investigation is described in Section III. The result analysis is covered in Section IV, and in Section V, we wrap up the investigation with some conclusions and plans for future research.

2. Related Works

The decrease in real interest rates over the past few decades has been common among many researchers [

8], some of whom ascribed it to too few investments, higher private saving propensities and lower investment tendencies. This interpretation places the phenomenon in the broader picture of the economy, which is dominated by the events of the global financial crisis and the eurozone crisis. On the other hand, some scholars such as [

9] may point out that the stagnation in the long-term real interest rates cannot be understood just within the past few decades, it is a stationary, persistent trend and it originates as far back as the 1300s. This long-drawn decrease, as they put it, represents a global discernment of discount factors over time, which dismantles the conventional explanations of productivity and demography factors. Switching to the focus of financial markets and monetary policy- [

10] demonstrates that prolonged rates estimated by 10-year bond yields in developed countries have declined for two reasons. First is the distinct conventional monetary easing and second is the non-conventional measures by the federal reserve. Conventional monetary easing is associated with increasing the slope of the yield curve in advanced economies leading to a sharper drop in short-term yields as weaning into non-productive measures limited by rate foreigners nominal interest rate spreads. In addition, [

11] indicates that monetary policy changes affect the 10-year forward real rates mainly through short rate movements from FOMC announcement days. [

12] propose a “reaching for yield” mechanism, whereby yield and risk-seeking investors begin to substitute short-term bonds with lengthier duration bonds in an increasing term structure of interest rates environment. This increase in longer-maturity bond demand compels prices to increase and yields to fall constructing a premium effect.

Recent studies such as [

13] have focused on measuring specific monetary policy impacts over short periods, which may surprise many. Some research such as [

14] evaluates the “Fed information effect” and its underlying rationales, the non-neutrality of money, by measuring high-frequency interest rate moves before and after FOMC meetings in characteristics of the information shock. The results show that not only financial variables are affected by announcements about the monetary policy, but also beliefs and expectations concerning the economy of the private sector. They show that by considering how these adjustments are incorporated into private sector expectations, most of the variations of the changes in real interest rates are due to changes in perceived natural interest rates, which views the role of monetary policy in targeting expectations. However, the more recent works take issue with the prevailing view about the “Fed information effect” which sees monetary policy announcements as adding new information to the economy. Investigating high-frequency data around FOMC meetings combined with the availability of news items, these scholars argue for a different view – the EMH, the FOMC responds to news. Their assessment shows that the federal reserve follows public economic news that the market also anticipates, instead of having inside news that moves the market.

Scholars such as [

15] consider this outcome as unexplainable because it is usually believed that the underlying reasons for such long-term trends are not monetary. Such an assertion is consistent with the allegation of “long-run Fed guidance,” whereby federal reserve pronouncements may inform the long-run path of interest rates. Leading up to now in this paper, the evolution of the literature on the conduct of monetary policy and its effect on real rates of interest as one would gauge by yields is all that has been highlighted. Equally important to this investigation is the study of ‘the global financial cycle, which has been developed by [

16]. This research shows that about 20% of the common variation in the prices of risky assets across the globe is attributable to a common global factor. Due to the continued prevalence of the US dollar in international finance, such as about 80% of the syndicated lending of over

$ 5 million done in US dollars, the monetary choices of the federal reserve shape the global financial cycle. This commonly observed event can be attributed to many factors such as the trend towards leverage reduction among financial institutions internationally, the reduction of global credit and gross savings performance over time and increased total risk aversion [

17,

18,

19].

3. Empirical Study

This section aims to examine information on the institutional background of the central banks’ mechanisms for monetary decision-making in each of the countries in the given model. Thereafter, elaborate on both yield data and the data on monetary policy decisions concerning several observations and time intervals.

3.1. Eurozone

The primary body liable for the development and implementation of the supranational currency policy is the Governing Council of the European Central Bank (ECB) which consists of 26 members. Herein, 6 members are from the executive board and governors of the national central banks of the Euro-area are comprised. This institution assembles twice a month to examine the investigation of the macroeconomic and financial environment. However, the meetings held on monetary policy outlook take place after about six weeks. To execute monetary policy, the governing council utilises three principal rates of lending: the principal refinancing operations rate, the deposit facility rate, and the marginal lending rate. We accessed the ECB website for information on monetary policy procedures and implementation dates, covering 299 decision dates from March 1999 to March 2024. To eradicate any potential variations associated with the bond yields of countries, it was decided to base this paper on the example of Germany. Consequently, on-the-run yields of 10-year German bonds were apprehended to ensure adequate baseline measures of bond market responses to ECB policy announcements.

3.2. United Kingdom

In the UK, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) is the committee within the Bank of England (BoE) with the authority to initiate and conduct monetary policy. It contains 9 members; the first consists of the governor and three deputy governors responsible for monetary policy, financial stability and markets and banking, the second one is the chief economist, and the last four members are external members; all appointed by the chancellor. The primary policy interest rate which is largely the overall or key policy interest rate set is called the ‘bank rate’ which in this case is the interest rate that the BoE pays to commercial banks that keep reserves with the BoE. The dates of relevant monetary policy actions have been retrieved from the voting history of the BoE, which is contained online from June 1997 to March 2024, hence 295 data points. For this study, we enquired about yield on UK government bonds, also referred to as wares, from 1979 to 2024 and drew most of the data from the BoE database. The yield data also considers estimates of zero coupon continuously compounded yields that are more sophisticated and analyzed in previous research.

3.3. Japan

The main body that conducts monetary policy in Japan is its policy board within the Bank of Japan (BoJ). There are nine members in the policy board namely, the governor, two deputy governors, and six members appointed by the cabinet. The most common channel of monetary policy of the BoJ is the policy-rate balance which refers to an interest paid on the policy-rate balances held by financial institutions with the BoJ. There are 515 items included in the data set compiled on the BoJ’s monetary policy decision dates and these decision dates extend from December 1981 to March 2024. The government bonds’ interest rates were collected from the database of the Japanese Ministry of Finance using the most recently issued securities.

3.4. Canada

In Canada, the governing council of the Bank of Canada is responsible for most, if not all, of the decision-making regarding the implementation of monetary policy as well as the prospects of this country’s stable financial system in the future. The governors’ council members include the governor, senior deputy governor and four deputy governors. The council primarily focuses on one tool is the policy interest rates for the conduct of monetary policy pegged on 8 such dates in one year on pre-specified announcement dates. The consensus-building method has been adopted in the decision-making process. A sample of 175 monetary policy decision dates was covered within the period between January 1999 to April 2024. For this analysis, yield data was sourced from the Bank of Canada in which historical zero-coupon yield curve data was derived.

3.5. Switzerland

The highest management structure and executive body of the Swiss National Bank (SNB) is the governing board which makes all the management decisions. The governing board consists of three members who serve a six-year term and are appointed by the member of the federal council on the advice of the bank council. It is the board's responsibility to develop the monetary policy of the national bank of Switzerland, giving the go-ahead for the changes in the policy rate. The objectives of this policy are on the one side to reduce the difference between the interest charged on the short-term Swiss franc money market and the policy rate. The dates, for data for monetary policy decisions, are from January 2000 to March 2024 and cover 109 meetings altogether. Data on the yield known as spot interest rates is determined via the extended Nelson-Siegel procedure using the zero-coupon bonds as instructed by the SNB.

3.6. Australia

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) formulates their monetary policy via its main decision-making unit, the Reserve Bank Board. There are nine members on this board including the governor, deputy governor, treasury secretary, and the six government-appointed members. The board usually meets eight times a year to consider issues pertaining to monetary policy and its formulation. The RBA’s principal instrument of day-to-day monetary policy is the ‘cash rate target’, the policy rate that governs short-term money market activity and determines a band of corresponding rates throughout the economy. For our analysis, we obtained through the RBA the dates of the meetings where decisions on monetary policy were made between August 1992 and March 2024. Further, we sourced the yield data for the Australian government bonds covering the period from January 1995 to May 2024 from the RBA. The RBA computes and interpolates yields.

4. Result Analysis

On the sample comprising advanced economies, it was found that heterogeneous effects accrue to both the nation’s monetary policy and that of the U.S. Also, non-conventional types of monetary policy interventions, such as quantitative easing programs, yield different results in different countries. Therefore, this paper will analyze the yield fluctuations occurring around monetary policy announcement dates within each country.

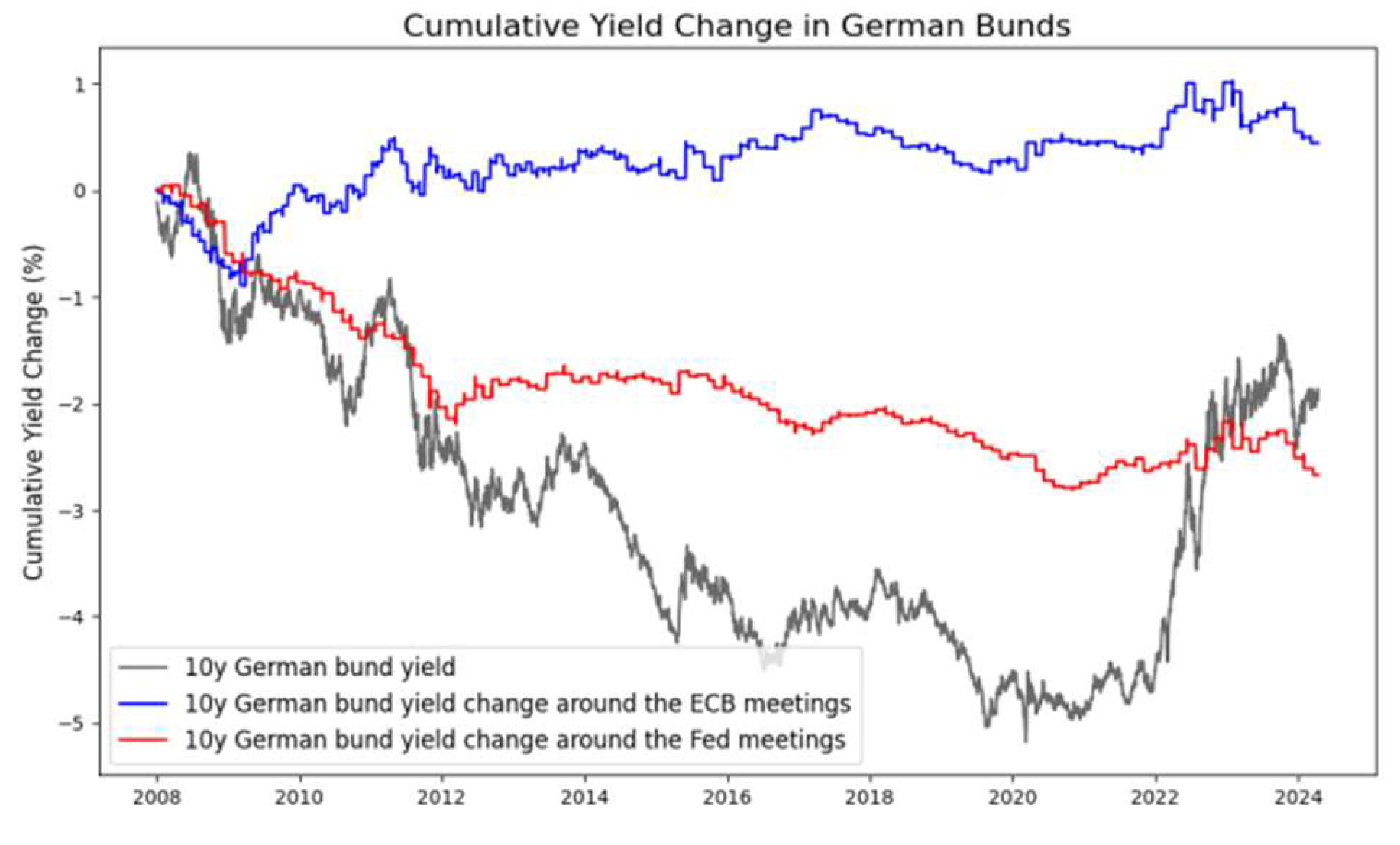

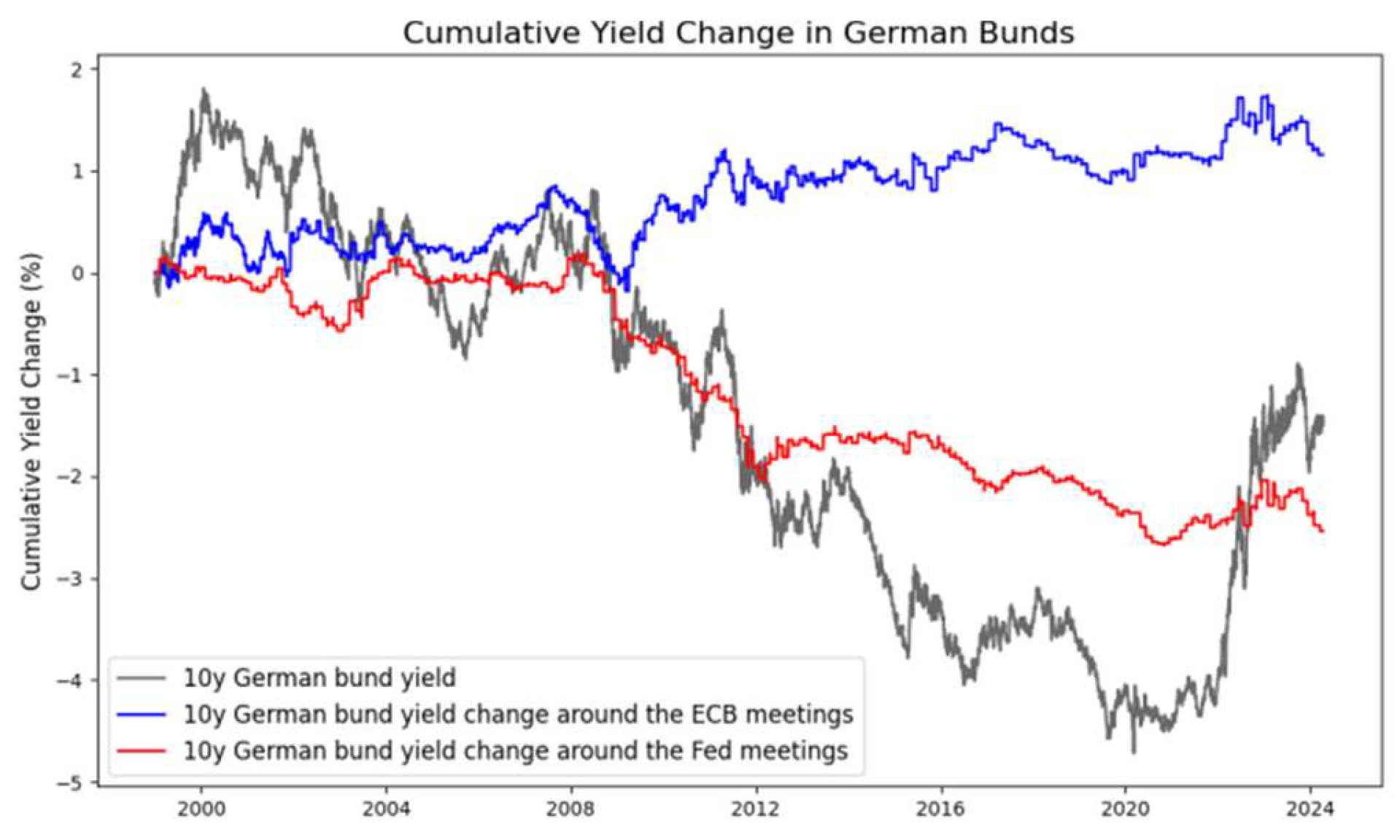

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 show how the cumulative change in the yield of 10-year German bunds is changing. In

Figure 1, it is suggested that the interest rate adjustments undertaken by the European Central Bank are logically inconsequential to the German bunds. Yield change and ECB’s within-window yield change even went on inverse movement from the year 2009 to the year 2012. This brings about the question of whether the skew seen in the more aggressive monetary policy tool of the ECB, namely the securities market programme between the years 2010 and 2012, did indeed mitigate the negative outlook of the ECB levellers against bunds. On the other hand, it seems that the actions taken by the federal reserve, particularly in the period under review, i.e. between the years 2008 and 2012, had effects on German bund yield.

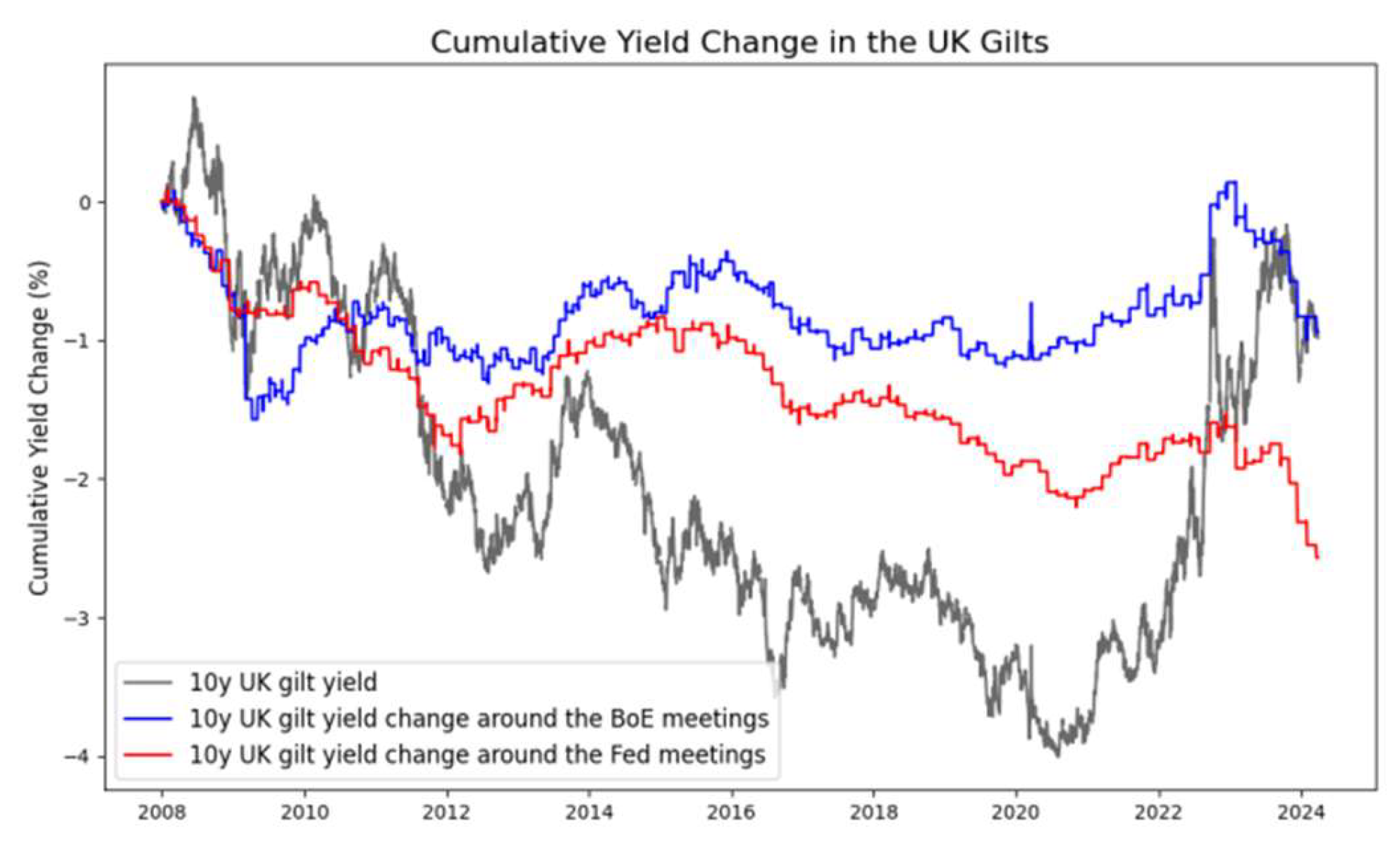

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 suggest that, although the BoE experienced a reduction in its authority over long-term real rates following the 2008 financial crisis, the United Kingdom when compared to other countries in the sample, retains relatively greater monetary authority over its yields.

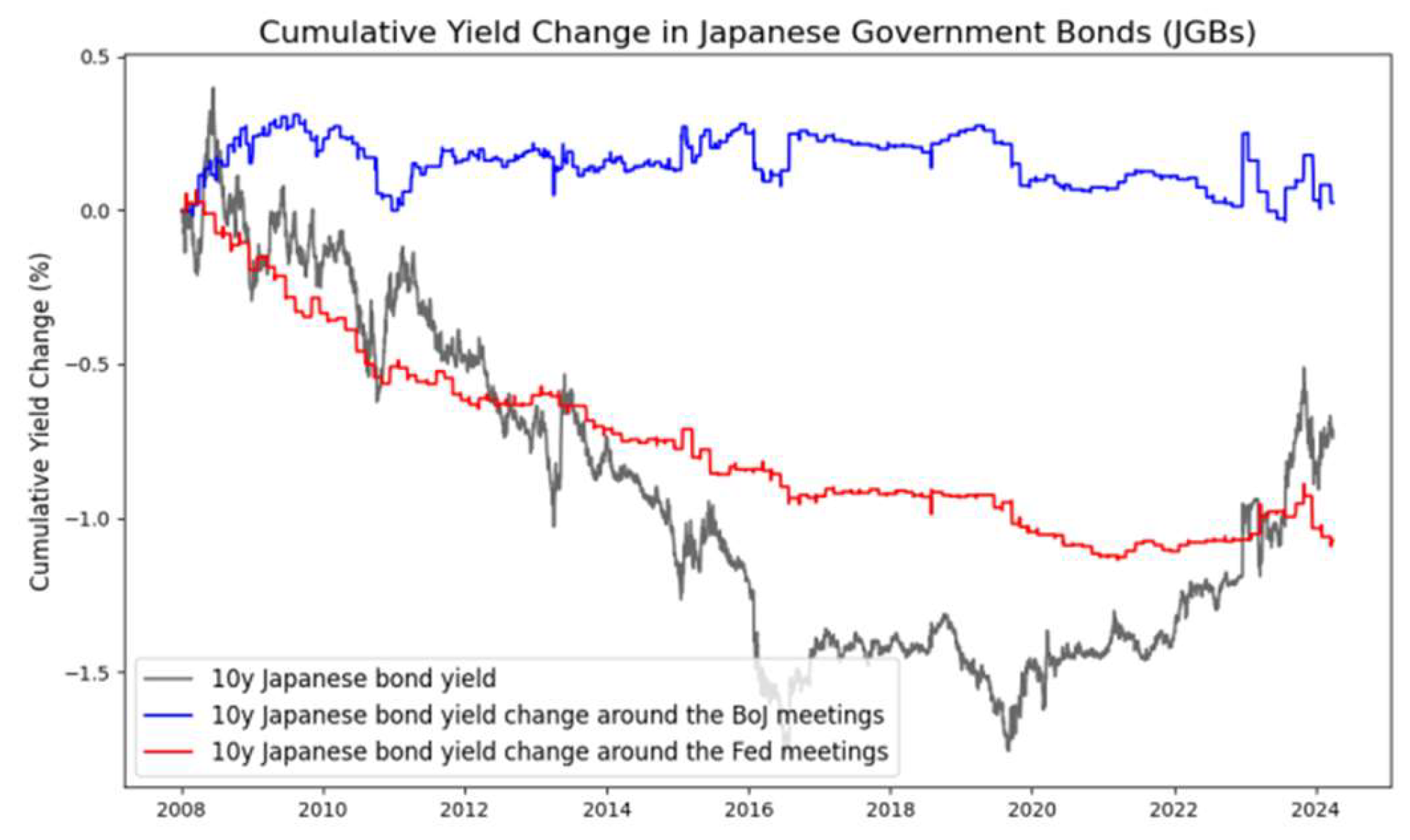

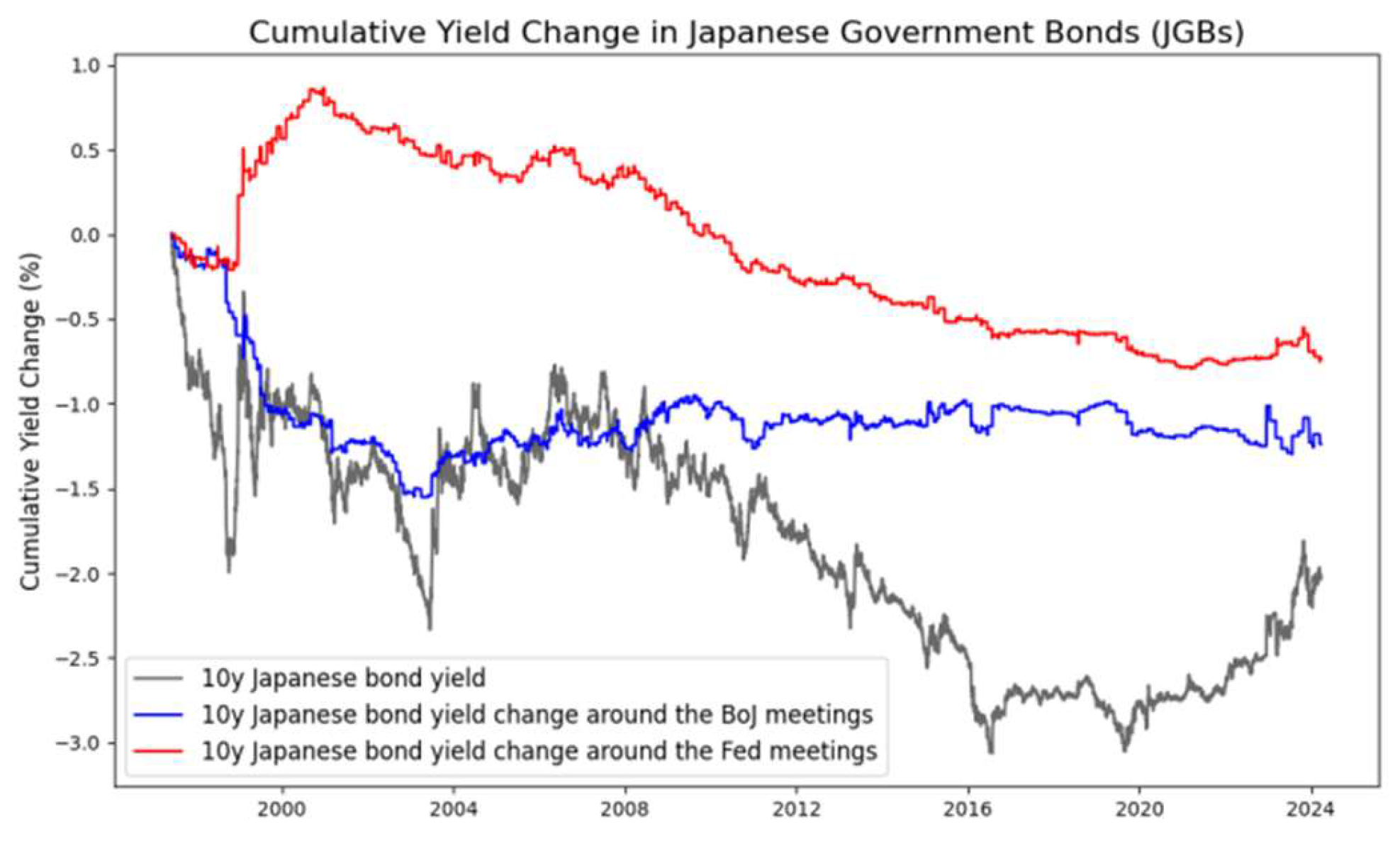

The BoJ maintained monetary authority over long-term bond yields as shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. Until approximately 2006-2008, the evidence indicates that following the financial crisis, yield movements increasingly occurred around Fed meetings.

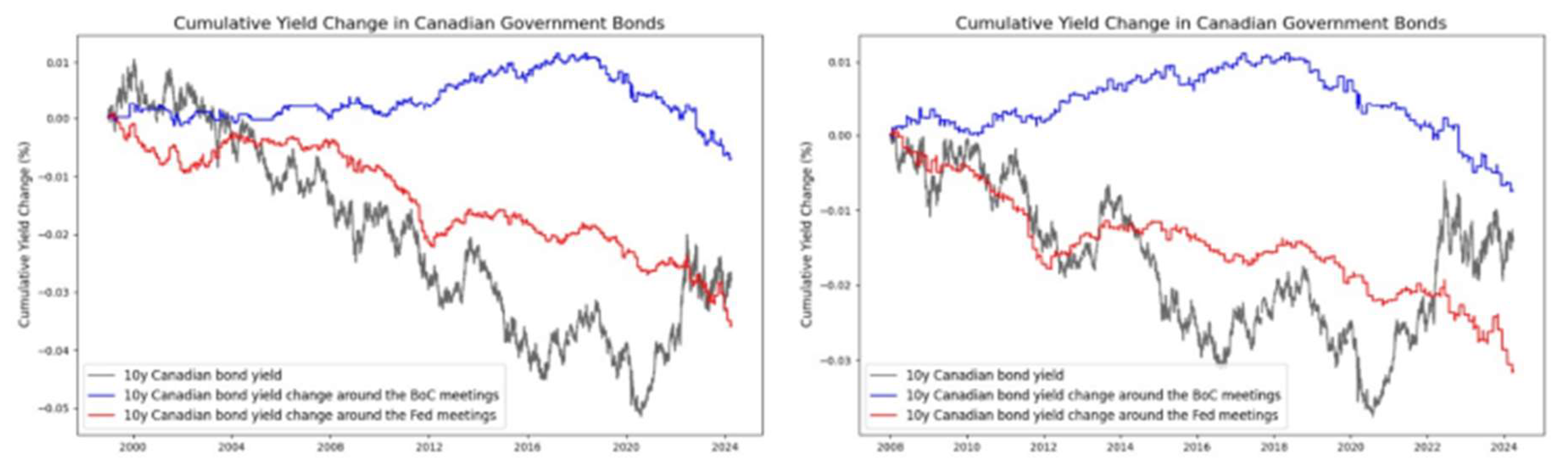

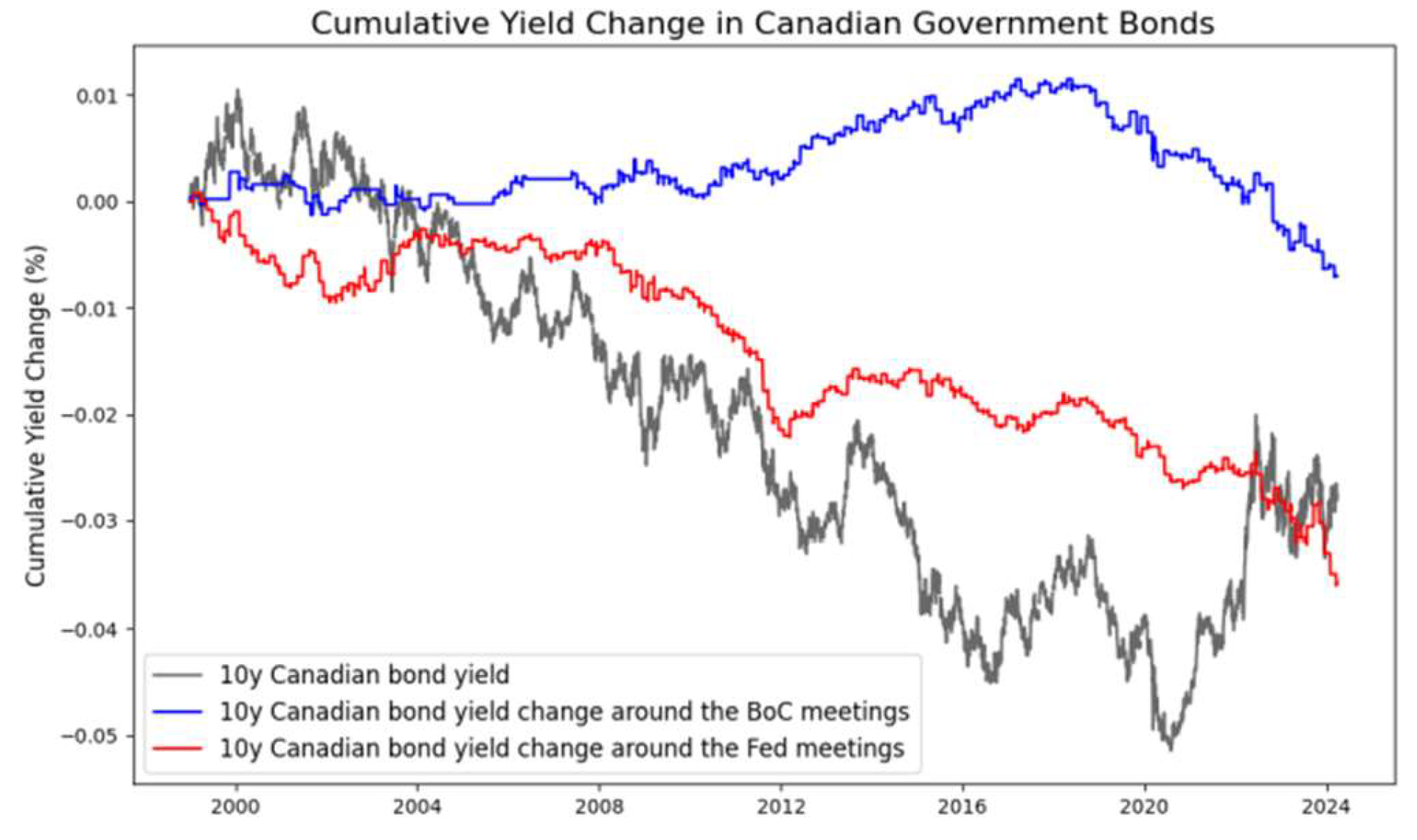

Fortunately, this is quite well-known among everyone. The movements of Canadian yield movements share more the Fed than the BoC as shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

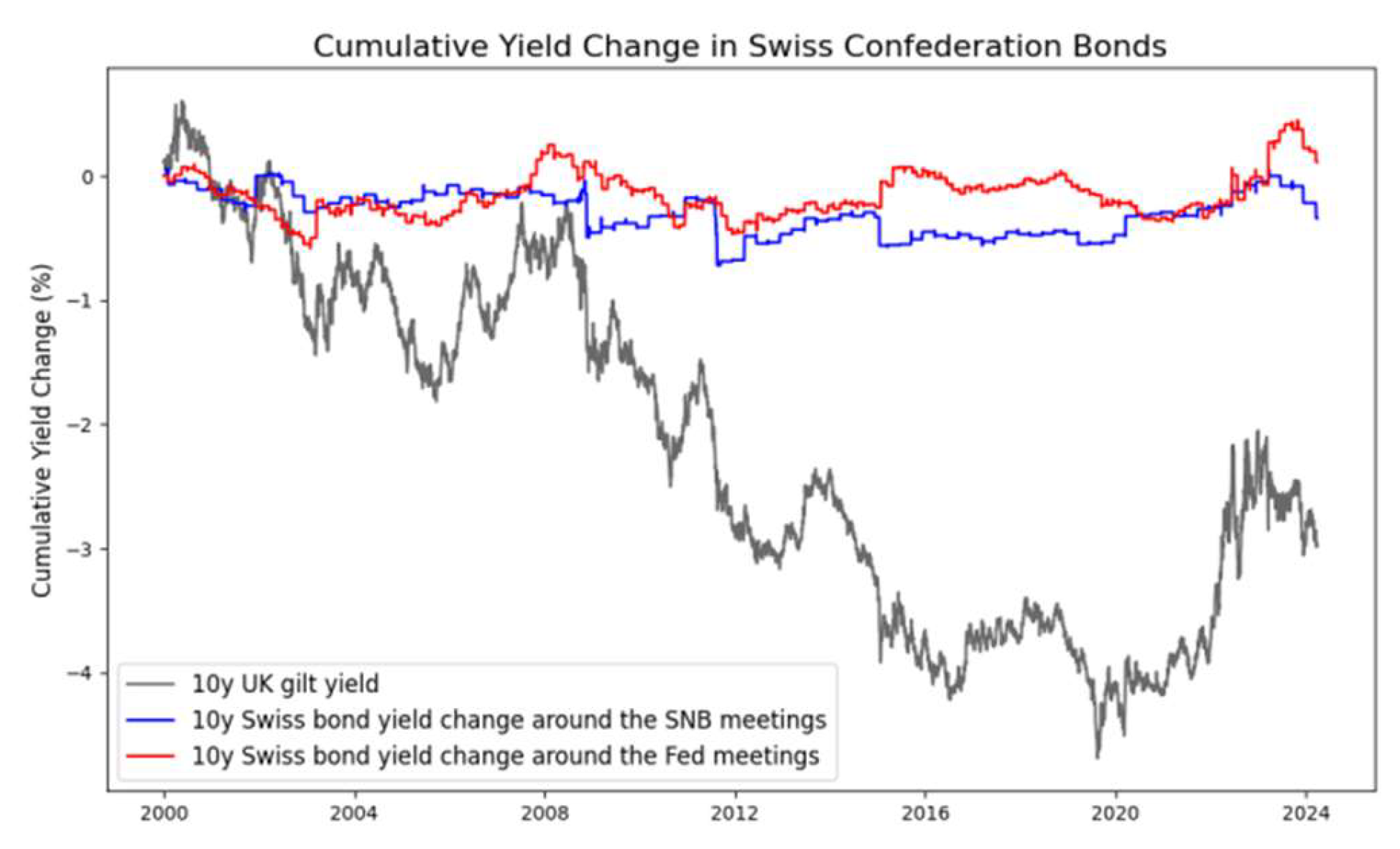

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 indicate that the short-term three-day lines drawn around monetary policy board meetings of the FOMC and those of the SNB inadequately relate to the fall in long-term yields. In addition, no such hierarchies of breaks can be attributed to the global financial crisis. Given how these focus on attitudes differ from findings in other countries within the sample, more work has to be done. There exist some key macro-financial disparities between Switzerland and the countries’ rest of the sample. First, as both in this analysis and the relevant literature, the SNB is known to conduct significant foreign exchange market operations for reasons of inflation targeting or to protect the position of the Swiss Franc as a haven currency. Furthermore, it has been shown that the geographical distance instead influences the real interest rates of Switzerland through the state premium, which itself depends on the valuation channel.

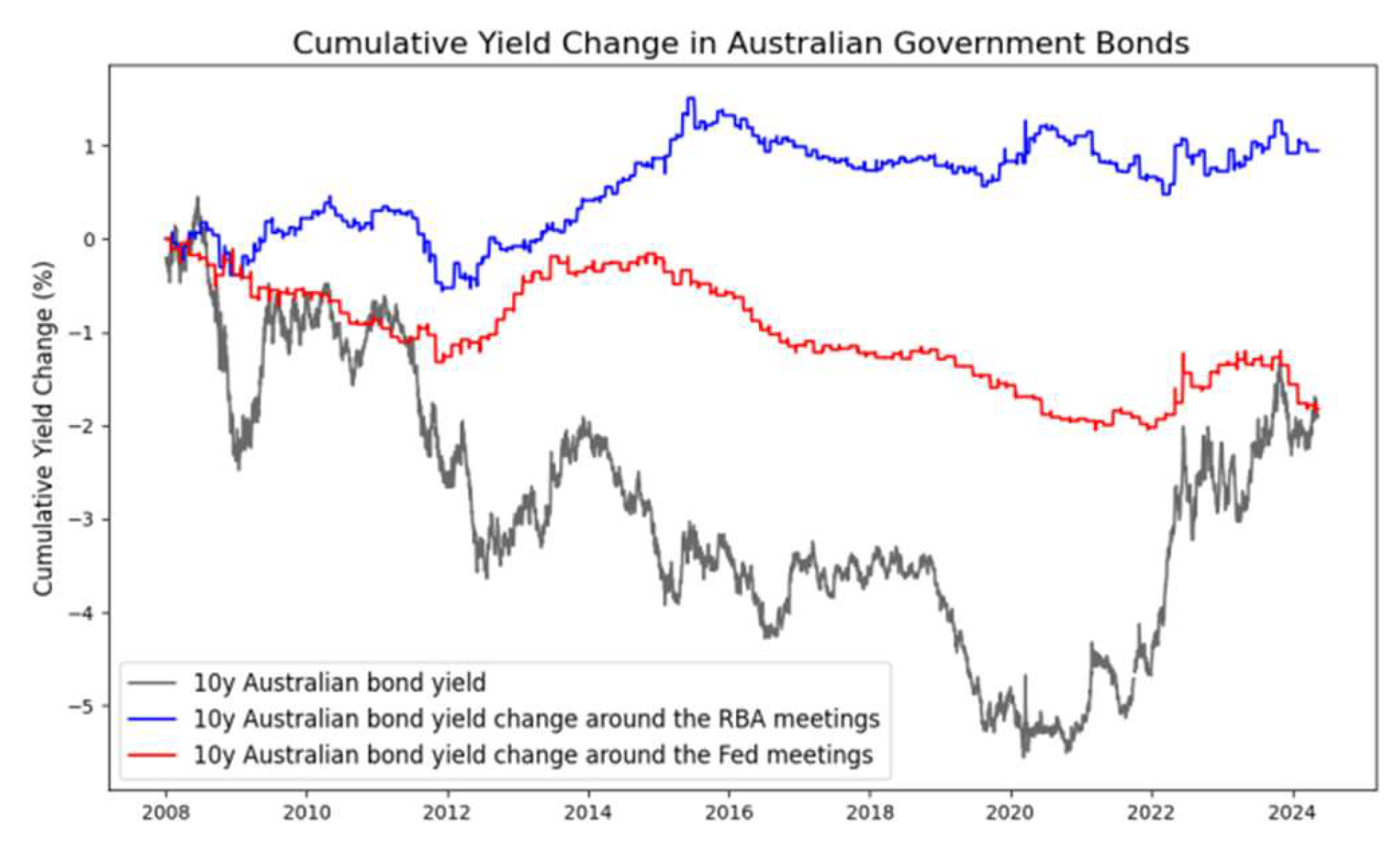

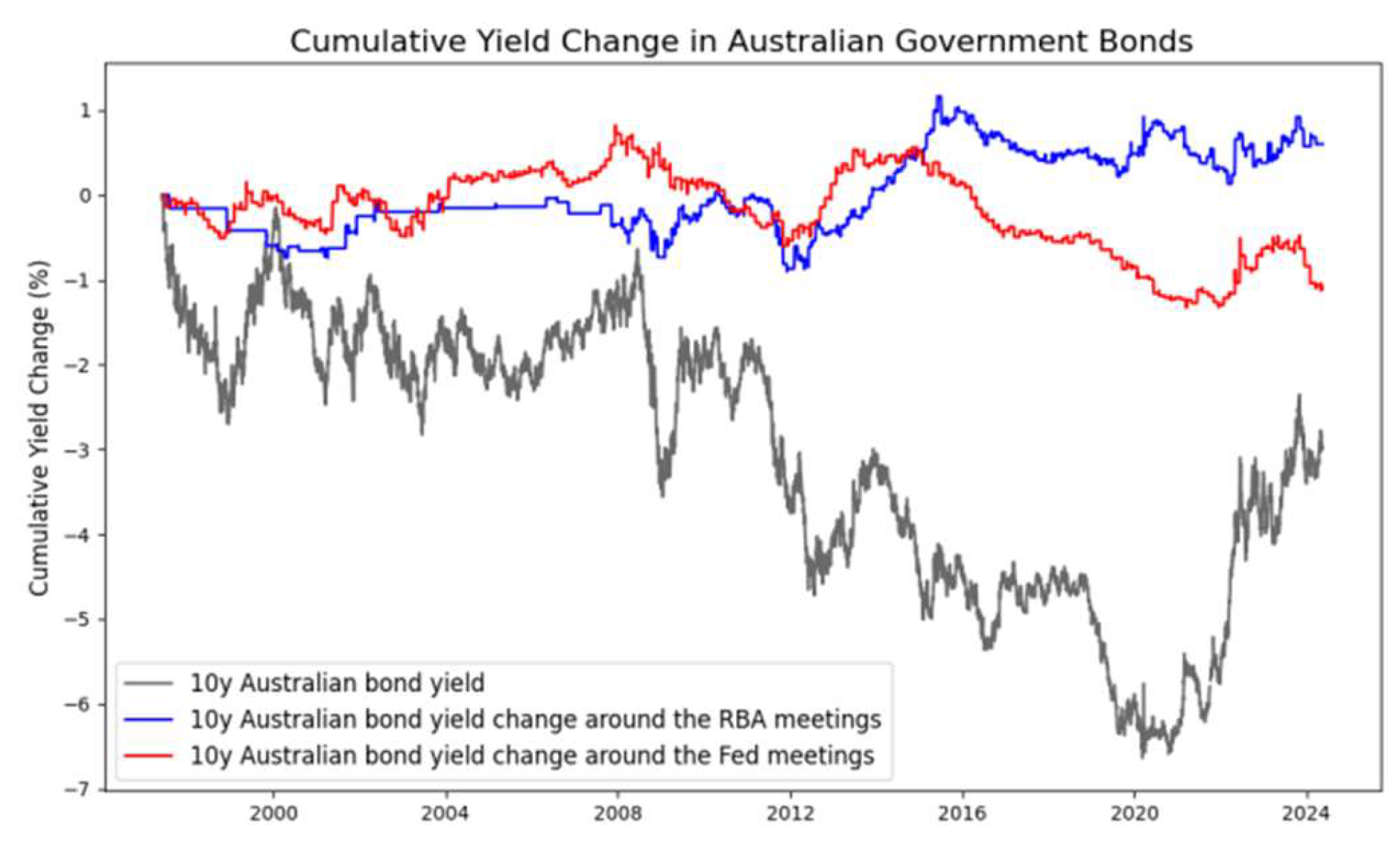

This Australian Government Bond yield is a bit complicated as shown in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12.

5. Conclusions

This study has shown how the monetary policy of the U.S. federal reserve affects the long-run government bond yield in various advanced economies. The analysis contends that even though there is some influence of domestic monetary policies on yield curves, the policies of the U.S. federal reserve dominate, largely because of the dollar's status as a reserve currency and the globalization of financial markets. The findings align with the secular stagnation theory, which attributes the persistent decline in real interest rates to structural factors like ageing populations, reduced investment potential, and slower productivity growth. On the policy level, these results indicate that smaller advanced economies should factor in the U.S. monetary policy while setting their economic policies since their policies may have limited effectiveness in cushioning external shocks emanating from the federal reserve. There is a possibility, and indeed a necessity, to study in the future how the global financial cycle is experienced in emerging markets, the effects of using central bank policies differently in different sectors from the generic approach used in the literature, or how such unconventional measures as quantitative easing work. For instance, the changing nature of bond yield sensitivities across the various economic cycles could be examined along with the attitudinal responses of the private sector to policy announcements. There also remain arguably equally important topics which require attention in further investigation of the interrelations of global economics and markets.

Funding

No funds: grants, or other support was received.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing for financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data Availability

Data will be made on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Code will be made on reasonable request.

References

- Kumar, S. Dodda, N. Kamuni, and R. K. Arora, “Unveiling the Impact of Macroeconomic Policies: A Double Machine Learning Approach to Analyzing Interest Rate Effects on Financial Markets,” Mar. 2024, Accessed: May 05, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.07225v1.

- J. B. Taylor, “Discretion versus policy rules in practice,” Carnegie-Rochester Confer. Ser. Public Policy, vol. 39, no. C, pp. 195–214, Dec. 1993. [CrossRef]

- M. Kanojia, P. Kamani, G. S. Kashyap, S. Naz, S. Wazir, and A. Chauhan, “Alternative Agriculture Land-Use Transformation Pathways by Partial-Equilibrium Agricultural Sector Model: A Mathematical Approach,” Aug. 2023, Accessed: Sep. 16, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.11632v1.

- G. S. Kashyap et al., “Detection of a facemask in real-time using deep learning methods: Prevention of Covid 19,” Jan. 2024, Accessed: Feb. 04, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.15675v1.

- F. Alharbi and G. S. Kashyap, “Empowering Network Security through Advanced Analysis of Malware Samples: Leveraging System Metrics and Network Log Data for Informed Decision-Making,” Int. J. Networked Distrib. Comput., pp. 1–15, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. S. Kashyap, K. Malik, S. Wazir, and R. Khan, “Using Machine Learning to Quantify the Multimedia Risk Due to Fuzzing,” Multimed. Tools Appl., vol. 81, no. 25, pp. 36685–36698, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Wazir, G. S. Kashyap, K. Malik, and A. E. I. Brownlee, “Predicting the Infection Level of COVID-19 Virus Using Normal Distribution-Based Approximation Model and PSO,” Springer, Cham, 2023, pp. 75–91. [CrossRef]

- R. Arora, S. Gera, and M. Saxena, “Mitigating security risks on privacy of sensitive data used in cloud-based ERP applications,” in Proceedings of the 2021 8th International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development, INDIACom 2021, 2021, pp. 458–463. [CrossRef]

- Arpita Soni, “Advancing Household Robotics: Deep Interactive Reinforcement Learning for Efficient Training and Enhanced Performance,” J. Electr. Syst., vol. 20, no. 3s, pp. 1349–1355, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Kanaparthi, “Examining Natural Language Processing Techniques in the Education and Healthcare Fields,” Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol., vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 8–18, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. Kanaparthi, “Evaluating Financial Risk in the Transition from EONIA to ESTER: A TimeGAN Approach with Enhanced VaR Estimations,” Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Kanaparthi, “Transformational application of Artificial Intelligence and Machine learning in Financial Technologies and Financial services: A bibliometric review,” Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. K. Kanaparthi, “Navigating Uncertainty: Enhancing Markowitz Asset Allocation Strategies through Out-of-Sample Analysis,” Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. Kanaparthi, “Robustness Evaluation of LSTM-based Deep Learning Models for Bitcoin Price Prediction in the Presence of Random Disturbances,” Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Habib, G. S. Kashyap, N. Tabassum, and T. Nafis, “Stock Price Prediction Using Artificial Intelligence Based on LSTM– Deep Learning Model,” in Artificial Intelligence & Blockchain in Cyber Physical Systems: Technologies & Applications, CRC Press, 2023, pp. 93–99. [CrossRef]

- V. K. Kanaparthi, “Examining the Plausible Applications of Artificial Intelligence & Machine Learning in Accounts Payable Improvement,” FinTech, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 461–474, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. S. Kashyap, A. Siddiqui, R. Siddiqui, K. Malik, S. Wazir, and A. E. I. Brownlee, “Prediction of Suicidal Risk Using Machine Learning Models,” Dec. 25, 2021. Accessed: Feb. 04, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=4709789.

- N. Marwah, V. K. Singh, G. S. Kashyap, and S. Wazir, “An analysis of the robustness of UAV agriculture field coverage using multi-agent reinforcement learning,” Int. J. Inf. Technol., vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 2317–2327, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. S. Kashyap et al., “Revolutionizing Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review of Artificial Intelligence Techniques in Farming,” Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Wazir, G. S. Kashyap, and P. Saxena, “MLOps: A Review,” Aug. 2023, Accessed: Sep. 16, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.10908v1.

- S. Naz and G. S. Kashyap, “Enhancing the predictive capability of a mathematical model for pseudomonas aeruginosa through artificial neural networks,” Int. J. Inf. Technol. 2024, pp. 1–10, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Kaur, G. S. Kashyap, A. Kumar, M. T. Nafis, S. Kumar, and V. Shokeen, “From Text to Transformation: A Comprehensive Review of Large Language Models’ Versatility,” Feb. 2024, Accessed: Mar. 21, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.16142v1.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).