Introduction

Traditional neuropsychological tests have long been the dominant method for assessing cognitive functions in relation to everyday functioning. However, these tests are significantly limited by their lack of ecological validity. Ecological validity refers to the extent to which an assessment's tasks resemble real-life activities (verisimilitude) and correlate with real-world performance (veridicality; [

1,

2]. The primary issue with traditional measures is that they typically take place in laboratory settings, where the simplicity and static nature of tasks fail to represent the complexities of daily life [

3,

4,

5]. This lack of ecological validity can result in inconsistent findings when evaluating cognitive functions relevant to everyday activities [

6].

1.1. Ecological Validity of Virtual Reality Assessments

Traditional neuropsychological measures often lack ecological validity because they are typically conducted in laboratory settings, where the simple and static nature of tasks does not accurately represent the complexities of everyday life [

3,

5,

7]. This lack of ecological validity is a significant limitation because it impairs the ability to relate task performance scores to real-life functioning, even in neurological intact individuals [

2,

6]. Furthermore, non-ecologically valid measures can yield inconsistent results when assessing cognitive functions relevant to daily activities [

5].

Efforts to replicate everyday tasks in naturalistic settings have attempted to address these limitations, but they face significant challenges, including the inability to standardize for clinical use, the tendency to overlook specific groups (e.g., mental health patients), and limited control over extraneous variables [

5]. These challenges have driven the development of alternative methods for neuropsychological assessment, with immersive virtual reality (IVR) emerging as a highly promising substitute for traditional testing methods [

4,

8,

9].

IVR technologies have been shown to enhance ecological validity by creating more adaptable and realistic environments that better reflect real-world scenarios. For example, VR-based assessments like the Virtual Reality Everyday Assessment Lab (VR-EAL) have demonstrated high ecological validity compared to traditional tests, particularly in assessing executive functions (e.g. mental flexibility, attentional set-shifting, processing speed), within activities of daily living (ADL) [

5,

10]. Systematic reviews have confirmed that VR technology is highly ecologically valid as a neuropsychological tool for various cognitive functions, including attention and memory [

3,

4,

9,

11]. Such assessments have proven valuable in predicting overall performance in everyday life [

3,

5,

12].

Virtual reality assessments also allow clinicians and researchers to extend studies to specific populations and cognitive domains in alternative settings, providing more accurate evaluations of everyday functionality by examining the impact of environmental stimuli (e.g., sensory distractions) on cognitive performance [

13]. While IVR simulations of everyday activities have been extensively studied and shown to possess high ecological validity in terms of verisimilitude [

2,

5,

11], there is a notable lack of literature exploring their veridicality.

IVR technologies as neuropsychological instruments are designed to be user-friendly, requiring no prior experience or specific age group restrictions [

5,

14]. Research indicates that factors such as gaming ability, age, and educational background do not significantly impact performance in VR environments, suggesting broad applicability [

5]. Interestingly, individuals with no prior gaming experience often perform better in VR settings because their interactions closely resemble real-life scenarios [

3,

7,

15]. Moreover, both younger and older adults show greater motivation and engagement with VR-based cognitive tasks compared to traditional paper-and-pencil methods, while both age groups have demonstrated high levels of acceptability, adaptability, and familiarity with VR technologies [

9,

10,

16].

One challenge frequently encountered with IVR technology is VR-induced symptoms and effects (VRISE), commonly known as cybersickness. In the past, VR assessments often led to adverse physical symptoms such as nausea, disorientation, fatigue, and vertigo [

17,

18]. These symptoms could severely undermine the effectiveness of VR neuropsychological assessments [

19,

20,

21]. However, recent advancements in VR technology have significantly mitigated these issues by incorporating systems designed to minimize adverse effects, resulting in participants experiencing little to no VRISE symptoms [

10,

14,

21,

22].

1.2. Trail Making Test in Virtual Reality

The Trail Making Test (TMT) is a widely recognized and extensively utilized tool in neuropsychology for evaluating cognitive functions, particularly attention, processing speed, cognitive flexibility, and task-switching [

23,

24]. The TMT can be employed either as a standalone screening instrument to assess neurological impairments or as part of a broader battery of neuropsychological tests [

24]. Performance on the TMT is a reliable indicator of cognitive dysfunction and is frequently used to assess various cognitive abilities across different populations.

Given the TMT’s significance, there has been increasing interest in developing alternative versions of the test to enhance its usability and application. Numerous studies have consistently demonstrated the TMT’s effectiveness as a neuropsychological assessment tool. However, despite the test's broad applicability, research exploring a virtual reality (VR) adaptation of the TMT has been limited.

In one study, researchers developed an immersive VR version of a TMT alternative, specifically the Color Trail Test, and reported high ecological and convergent validity [

25]. However, this study faced several limitations: it employed complex methodologies and required expensive equipment, making the system inaccessible to many clinicians and difficult for researchers with limited funding to replicate. Moreover, the study appeared to focus more on the technological aspects rather than clinical applications, thus limiting its practical use in everyday clinical settings. Notably, while this was the first known adaptation of a TMT alternative into a VR context, the original Trail Making Test has yet to be fully explored and utilized in VR environments.

The TMT has been employed in various neuropsychological contexts to evaluate cognitive functioning, particularly in populations with attention deficits. Numerous studies on adults with ADHD have utilized both parts of the TMT—Part A and Part B—as supplementary assessment tools [

26,

27,

28,

29]. Part B, which assesses cognitive flexibility and task-switching, has been particularly effective in identifying set-shifting issues among adults with ADHD [

26].

This current study represents the first adaptation of the traditional TMT into a virtual reality format, the TMT-VR, with the goal of confirming its validity and effectiveness as a clinical tool. In a preliminary study, three different interaction modes—eye-tracking, head movement, and controller—were tested to compare performance among 71 neurotypical young adults [

30]. The results indicated that both eye-tracking and head movement were significantly more efficient than the controller in terms of task performance, including accuracy and task completion time. Specifically, eye-tracking was found to be more accurate, while head movement facilitated faster task completion. Despite these differences, no significant overall performance differences were observed between eye-tracking and head movement, suggesting that both modes could be viable alternatives. However, further analysis revealed that eye-tracking demonstrated superior accuracy among non-gamer participants, indicating that it may be more universally applicable and better suited for clinical settings, especially in studies involving individuals with ADHD.

Neuropsychological Assessment in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by persistent patterns of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity that can vary in severity among individuals [

31,

32]. ADHD is among the most prevalent neurodevelopmental disorders, affecting approximately 5% of children and adolescents globally [

33,

34]. Traditionally, ADHD has been perceived as a childhood disorder, with the expectation that symptoms would diminish as individuals age. However, recent longitudinal studies have provided compelling evidence that ADHD often persists into adulthood, challenging this outdated notion [

34,

35].

Meta-analytic research indicates that about 65% of individuals diagnosed with ADHD in childhood continue to exhibit symptoms into adulthood, highlighting the chronic nature of the disorder [

36,

37]. Despite this persistence, the prevalence of ADHD in adults is estimated at around 2.5%, which may be underreported due to the complexities and subtleties of diagnosing ADHD in adult populations, where symptoms may manifest differently than in children [

36,

38].

ADHD can have a profound impact on everyday functioning, affecting multiple cognitive domains essential for daily tasks. Core cognitive deficits in individuals with ADHD include impairments in sustained attention, behavioral inhibition, working memory, and perceptual processing speed [

6,

39]. These deficits can lead to significant difficulties in academic achievement, occupational performance, and social interactions [

40,

41]. For example, sustained attention, crucial for tasks requiring prolonged mental effort, is often compromised in individuals with ADHD, resulting in difficulties completing tasks, following instructions, and maintaining focus in environments such as classrooms or workplaces [

39].

Behavioral inhibition, which involves the ability to control impulses and delay gratification, is another critical cognitive function often impaired in ADHD [

39]. Deficits in this area can lead to impulsive decision-making, challenges in resisting distractions, and difficulties adhering to social norms or expectations [

42]. These behaviors can significantly impact relationships, academic success, and career advancement [

43].

Research has shown that while symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity tend to decrease with age, inattention often persists across the lifespan, continuing to impact daily life and cognitive performance [

35,

44]. Persistent inattention can contribute to ongoing challenges in organization, time management, and completing tasks that require sustained mental effort, making it difficult for adults with ADHD to manage responsibilities such as finances, deadlines, and household organization[

40].

Given the significant and lasting impact of ADHD on cognitive and functional abilities, accurate neuropsychological assessments are crucial for effective diagnosis and treatment planning. Traditional neuropsychological tests have been widely used to evaluate the cognitive deficits associated with ADHD. However, these assessments often lack ecological validity, which refers to the extent to which test results reflect an individual's performance in real-life situations [

1,

11]. This lack of ecological validity is a significant limitation, particularly for adults with ADHD, who may face different cognitive challenges than children[

40].

The need for ecologically valid assessment tools is particularly pressing for adults with ADHD, as their cognitive difficulties are often context-dependent and influenced by the complexities of daily life [

40]. For instance, while children with ADHD may struggle primarily with hyperactivity in structured environments, adults may face greater challenges related to inattention and executive dysfunction in unstructured settings [

45].

In this context, the development of more ecologically valid assessment tools, such as virtual reality-based tests, is of paramount importance. These tools offer a more realistic and interactive testing environment that closely mimics the demands of everyday life, providing more accurate and meaningful insights into the cognitive abilities and challenges of individuals with ADHD [

3,

11]. By capturing the dynamic and multifaceted nature of cognitive functioning in real-world contexts, VR-based assessments can inform more effective treatment strategies and improve the overall quality of life for individuals with ADHD [

4].

1.3. Trail Making Test in ADHD

The TMT is widely used in neuropsychological assessments to measure cognitive functions such as attentional set-shifting, mental flexibility, and processing speed. These functions are often impaired in individuals with ADHD [

32,

46]. The TMT is typically divided into two parts: Part A, which involves connecting numbered circles in sequence, and Part B, which requires alternating between numbers and letters, thereby adding a cognitive load that tests mental flexibility and executive function.

In the context of ADHD, the literature suggests that TMT is an integral part of a broader assessment battery aimed at evaluating cognitive deficits related to attention and executive functions [

46]. However, the existing body of research on the application of TMT in ADHD populations presents some inconsistencies. While many studies report that individuals with ADHD tend to perform worse on both parts of the TMT, particularly Part B, due to its higher demands on cognitive flexibility and task-switching abilities [

32,

46,

47], other research has not found significant differences between ADHD and control groups, highlighting the variability in how ADHD affects cognitive functioning [

48]. These discrepancies may be due to variations in study design, sample characteristics, or the specific cognitive demands of the TMT in different contexts.

Nevertheless, a substantial body of evidence supports that individuals with ADHD, particularly adults, exhibit greater impairments on TMT Part B than on Part A, reflecting their broader challenges in tasks requiring attention, inhibition, executive functioning, and set-shifting [

28,

49]. This pattern is indicative of deficits in mental flexibility, a core cognitive function often disrupted in ADHD [

26,

49].

These findings suggest that the TMT, particularly Part B, is a valuable tool for identifying cognitive deficits associated with ADHD, specifically those related to mental flexibility and executive functioning. However, the variability in results across studies underscores the need for further research to clarify the conditions under which the TMT is most effective in differentiating between ADHD and neurotypical individuals. Such research is crucial for refining the use of the TMT in clinical practice, particularly in developing more tailored and accurate assessments for individuals with ADHD.

1.4. Virtual Reality & ADHD in Clinical and Non-Clinical Populations

The overall lack of ecological validity in traditional neuropsychological assessments significantly impacts the accuracy of clinical evaluations for ADHD [

44]. Common neuropsychological tests used to assess inattention and hyperactivity often have limited diagnostic utility and can yield inaccurate results [

44]. As a potential solution, a growing literature suggests that VR technologies could offer more reliable assessments by integrating interactive environments that closely resemble real-life scenarios, thereby enhancing ecological validity [

11,

44].

Individuals with ADHD frequently experience cognitive deficits, including difficulties in maintaining attention during monotonous or repetitive tasks, and challenges in task monitoring, preparatory processing, and response inhibition [

50,

51]. VR technologies are designed to allow sensory information (e.g., visual) to interact directly with the virtual environment while simultaneously monitoring the participant’s movements and positions during assessments [

50]. Furthermore, VR environments can be manipulated to create realistic yet highly interactive settings, in contrast to the monotony often associated with traditional assessment measures [

50].

Although research on VR interventions in ADHD populations remains limited, findings are promising. The integration of VR not only enhances assessment methods for individuals with ADHD but also improves performance in cognitive functions such as sustained vigilance [

50]. However, most studies have focused on children and adolescents, leaving adult ADHD relatively underexplored. This focus on younger populations likely stems from the higher prevalence of ADHD in children and adolescents, but there remains a critical need to investigate ADHD in adults. For example, symptomatic adult ADHD—where symptoms first present during adulthood—is a condition often lacking a clinical diagnosis due to the absence of noticeable symptoms during childhood [

34].

Studies on children and adolescents have provided valuable insights into the effectiveness of VR for ADHD. A meta-analytic study suggested that VR technologies could be used as a treatment method for attention and hyperactivity deficits and improve memory performance and overall cognitive function in children with ADHD [

52]. Interestingly, another study found that VR interventions were as effective in treating ADHD symptoms in children as traditional drug treatments and could potentially serve as a replacement in some cases [

53]. The present study aims to extend this literature by integrating the Trail Making Test (TMT) into a VR setting, with a specific focus on adults with ADHD, a population that has been underexplored.

The development of tools such as the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) has been crucial for assessing ADHD symptoms, including inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, in both clinically diagnosed individuals and undiagnosed adults. While the ASRS cannot independently provide a diagnosis, it is considered a highly accurate measure for identifying prevalent ADHD symptoms in non-clinical populations [

54]. By combining these validated tools with innovative VR technology, this study seeks to advance the assessment and treatment of ADHD across different age groups and diagnostic statuses.

1.5. Usability, User Experience, and Acceptability

The perception of neuropsychological assessment instruments by those being assessed has been extensively studied, with recent research indicating a strong preference for technology-based tools. Instruments that incorporate technology, such as virtual reality (VR), are generally rated highly in terms of usability and acceptability by users [

55,

56,

57,

58]. For instance, one study demonstrated the high technical acceptance of a TV-based platform for cognitive evaluations, highlighting its high usability and acceptability [

55]. Additionally, technology-based neuropsychological tools are promising in terms of resource efficiency, speed, and cost, factors that are often positively perceived by users and contribute to higher ratings [

57]. Furthermore, user experience reports indicate very positive attitudes towards these technologies across various age groups, including older adults [

5].

Although there are relatively few studies focused specifically on validating VR instruments as neuropsychological assessment tools, the available research shows promising results. For example, one study validated VR training software for adults with autism spectrum disorder, reporting high system usability and positive user experiences, suggesting minimal effort was required from users and that the software was easy to handle [

12]. High usability scores indicate that participants were able to inhibit automatic responses and ignore distractions effectively, engaging positively with the software [

12]. Similarly, high acceptability scores suggest that the VR software was well-received as a neuropsychological assessment tool [

12]. However, while these findings offer insights into the overall technical acceptance of VR technology, research in neuropsychology remains limited and further expansion is needed to establish VR as a valid neuropsychological assessment method.

1.6. Present Study

The development of the TMT-VR marks a significant effort to integrate virtual reality technologies into neuropsychological assessments. As the first VR adaptation of the traditional Trail Making Test, the TMT-VR aims to provide a comprehensive tool for evaluating various cognitive functions. This study is designed to validate the TMT-VR by assessing its ecological validity and convergent validity. Additionally, the study will evaluate the usability, user experience, and acceptability of the TMT-VR based on feedback from participants.

The study focuses on a clinical population, particularly young adults with ADHD, with the goal of establishing the TMT-VR as a reliable instrument for neuropsychological assessments in clinical practice. The study will compare performance on both the traditional TMT and the TMT-VR between neurotypical and neurodivergent populations. To assess the ecological validity of the TMT-VR, the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) will be utilized in both diagnosed and undiagnosed participants.

The study hypothesizes that:

H1: The TMT-VR will demonstrate high ecological validity, particularly in terms of veridicality.

H2: TMT-VR scores will show a significant positive correlation with traditional TMT scores, indicating high convergent validity.

H3: The TMT-VR will exhibit high usability, user experience, and acceptability among individuals with ADHD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 53 Greek-speaking young adults participated in the study. Of these, 47.17% were diagnosed with ADHD (N = 25), and 52.83% were neurotypical individuals (N = 28). Participants were recruited through ads, posters, and email invitations distributed via the American College of Greece’s email list. Appointments for participation were scheduled through the Calendly app. The participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 40 years (M = 23.87, SD = 3.82), and their total years of education ranged from 12 to 22 years (M = 15.98, SD = 3.26). To control for potential order effects, participants were counterbalanced: half were administered the TMT-VR first, while the other half began with the traditional paper-and-pencil version of the TMT.

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Hardware

In accordance with hardware recommendations aimed at significantly reducing the likelihood of cybersickness [

59], the VR setup in this study was centered around a high-performance PC, complemented by a Varjo Aero headset, Vive Lighthouse stations, SteamVR, noise-canceling headphones, and Vive controllers. The PC featured an Intel64 Family 6 Model 167 Stepping 1 Genuine Intel processor with a speed of approximately 3504 MHz and 32 GB of RAM, ensuring smooth and responsive VR performance.

The Varjo Aero headset was selected for its superior visual quality, boasting dual mini-LED displays with a resolution of 2880 x 2720 pixels per eye and a 115-degree horizontal field of view. Operating at a refresh rate of 90 Hz and equipped with custom lenses to reduce distortion, the headset delivered a highly immersive and high-fidelity visual experience. Positional tracking was managed by Vive Lighthouse stations, strategically placed diagonally to provide a large tracking area and precise tracking accuracy.

SteamVR served as the main platform for managing the VR experiences, offering robust room-scale tracking capabilities. To enhance auditory immersion, noise-canceling headphones were used, providing high-quality audio with active noise cancellation to minimize external distractions. Interaction within the virtual environment was facilitated by Vive controllers, designed ergonomically with haptic feedback, grip buttons, trackpads or joysticks, and trigger buttons, ensuring a responsive and tactile user experience. The integration of these components resulted in a comprehensive and immersive VR setup, enabling detailed and precise virtual reality experiences for the study.

2.2.2. Demographics

A custom demographics questionnaire was administered that collected information on the participant’s gender, age, years of education, GPA/CI, and whether participants have received an ADHD diagnosis.

2.2.3. Greek Version of the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS)

The Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) is a brief self-report screening tool for ADHD in adults [

54]. It is designed to assess ADHD symptoms (i.e., inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity symptoms in adults. It consists of 18 items rated on a 5-point Likert Scale (1= Never, 5= Very Often). An example question is, “How often do you feel restless or fidgety?” Scores are calculated by summing all responses. The Greek version of the ASRS was used [

60]. The Greek version retains the strong psychometric properties of the original scale, with Cronbach's alpha values typically ranging between 0.88 and 0.89, indicating excellent internal consistency, and it shows robust test-retest reliability around 0.79, suggesting reliable results over time [

54,

60].

2.2.4. Trail Making Test (TMT)

The Greek version of the traditional Trail Making Test was administered [

61], including both its parts; Part A and Part B. The test takes approximately 5-10 minutes. The primary measure is the total completion time for both parts, with a maximum score of 300 seconds, which serves as the cut-off for discontinuing the test [

24].

Part A

This section evaluates visual search and motor speed skills. Participants must draw a line connecting numbers in ascending order from 1 to 25. Performance is assessed based on the total time in seconds required to complete the task.

Part B

This section assesses higher-level cognitive skills such as mental flexibility. Participants must draw a line alternating between numbers and letters in ascending order (e.g., 1 to A, 2 to B, 3 to C, etc.) until completion. Performance is evaluated based on the total time in seconds needed to complete the task.

2.2.5. Cybersickness in Virtual Reality Questionnaire (CSQ-VR)

The CSQ-VR, developed by Dr. Panagiotis Kourtesis [

21], is a brief tool for evaluating VRISE [

21]. It consists of three categories, each with two items (Nausea A, B; Vestibular A, B; Oculomotor A, B), rated on a 7-point Likert Scale (1 = Absent Feeling, 7 = Extreme Feeling). An example question is, “Do you experience disorientation (e.g., spatial confusion or vertigo)?” Participants answer based on their current feelings. Each category is scored by summing Score A and Score B. The total CSQ-VR Score is the sum of all category scores (Nausea Score + Vestibular Score + Oculomotor Score). The CSQ-VR is administered twice during the assessment (before and after the VR session). The internal consistency of the CSQ-VR is particularly strong, with Cronbach’s alpha values exceeding 0.90, demonstrating excellent reliability. Additionally, its test-retest reliability is greater than 0.80, indicating that the CSQ-VR provides stable and reliable results across repeated measures. These metrics demonstrate that the CSQ-VR is a superior tool compared to other cybersickness questionnaires like the SSQ and VRSQ, especially in detecting performance declines due to cybersickness [

20,

21].

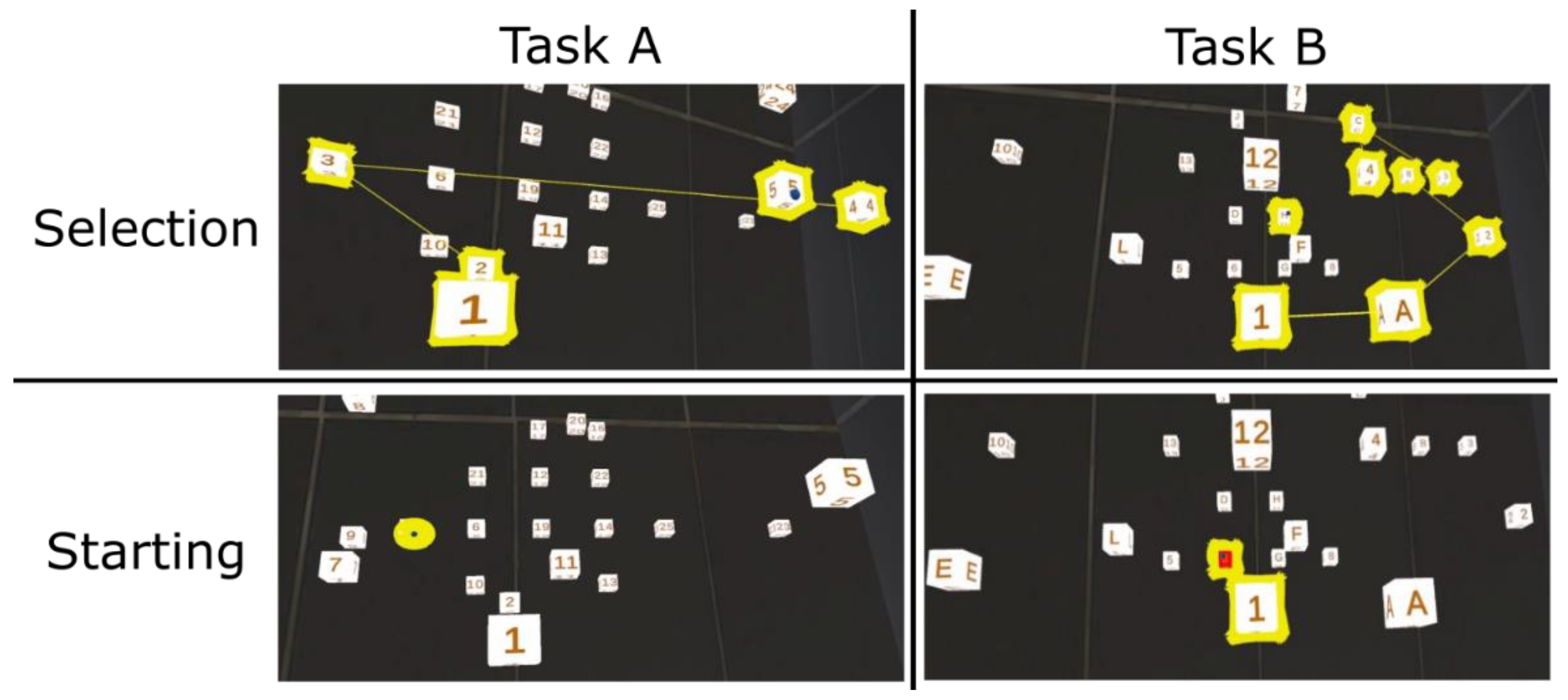

2.2.6. Trail Making Test VR (TMT-VR)

The Trail Making Test in Virtual Reality (TMT-VR) represents a significant advancement over the traditional paper-and-pencil version of the Trail Making Test [

30]. This VR adaptation is designed to leverage the immersive qualities of virtual reality to create a more naturalistic and engaging environment for cognitive assessment, specifically targeting young adults with ADHD. In the TMT-VR, participants are fully immersed in a 360-degree virtual environment where numbered cubes are distributed across a three-dimensional space, including the Z-axis, introducing a depth component that mirrors real-world spatial challenges (see

Figure 1).

A key feature of the TMT-VR is its naturalistic approach to target selection. Unlike the traditional TMT, which is limited to a flat, two-dimensional paper format, the TMT-VR allows participants to select targets using an intuitive, real-world interaction method—eye-tracking. This setup closely simulates how individuals naturally interact with their surroundings, providing a more accurate assessment of cognitive functions like visual scanning, spatial awareness, and motor coordination.

The administration of the TMT-VR is fully automated, including comprehensive tutorials that guide participants through the tasks. This automation ensures that all participants receive consistent instructions, eliminating the variability that can occur with human administrators. The scoring process is also automated, with precise timing of task completion automatically recorded, thereby eliminating the need for manual start and stop actions and providing a more accurate measure of cognitive processing speed.

Another innovative feature of the TMT-VR is the randomization of target placement within the virtual environment. Each time a participant undertakes the TMT-VR, the cubes are positioned in new, randomized locations, requiring participants to adopt a different spatial strategy each time. This randomization is essential for ensuring that the test maintains perfect test-retest reliability, as it prevents participants from simply memorizing target locations from previous attempts, which is particularly valuable for longitudinal studies or repeated assessments.

Participants interact with the virtual environment using eye-tracking technology, where the direction of the participant’s gaze is used to select objects. The task requires participants to select numbered cubes in ascending order. Each cube must be fixated upon for 1.5 seconds to confirm selection, ensuring deliberate and accurate interactions. This process minimizes errors due to inadvertent movements, which are common in both traditional and virtual environments.

Visual and auditory feedback are provided to guide participants throughout the tasks. Correct selections are highlighted in yellow, while incorrect ones are marked in red and accompanied by auditory cues. This immediate feedback allows participants to quickly correct mistakes, reducing frustration and helping maintain engagement. Previously selected cubes remain highlighted, assisting participants in tracking their progress and avoiding the re-selection of cubes.

The TMT-VR comprises two tasks that correspond to the traditional TMT-A and TMT-B:

TMT-VR Task A: Participants connect 25 numbered cubes in ascending numerical order (1, 2, 3,...25). This task measures visual scanning, attention, and processing speed, similar to the traditional TMT-A but within a more immersive environment.

TMT-VR Task B: Participants connect 25 cubes that alternate between numbers and letters in ascending order (1, A, 2, B, 3, C,...13). This task assesses more complex cognitive functions, including task-switching ability and cognitive flexibility, reflecting the traditional TMT-B but with the added benefits of the VR setting.

Performance on both tasks is depicted in terms of accuracy, mistakes, and completion time. Accuracy is measured as the average distance from the center of the target cube during selection, providing a precise metric of participant performance. Additionally, the number of mistakes—instances where participants selected the incorrect target—is recorded, offering further insight into cognitive control and task accuracy. Task completion times are automatically recorded, ensuring objective and consistent measurements of cognitive performance.

In summary, the TMT-VR offers a fully immersive, naturalistic, and randomized testing environment that enhances the traditional TMT [

30]. Its automated administration, precise scoring, and intuitive interaction method make it a powerful tool for cognitive assessment, offering greater ecological validity and reliability than traditional methods. The TMT-VR is particularly well-suited for diverse populations, including those with limited experience with technology, ensuring consistent and accurate cognitive evaluations across repeated assessments. A video presentation of each task of TMT-VR can be accessed using the following links: TMT-VR Task A and TMT-VR Task B (accessed on 1/9/2024).

2.2.1. System Usability Scale (SUS)

The System Usability Scale (SUS) is a tool for assessing system usability [

62]. It consists of 10 items on a 5-point Likert scale from “Strongly Agree” to “Strongly Disagree.” Responses are aggregated to create a total score that reflects the system’s usability, requiring specific calculations to convert raw scores into a usability score out of 100. An example question is, “I thought this virtual reality system was easy to use.” The questionnaire includes five reverse-scored items. SUS demonstrates excellent psychometric properties, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.85 to 0.92, indicating high internal consistency, and test-retest reliability of 0.84, showing good stability over time [

12,

62].

2.2.2. Short Version of the User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ-S)

The short version of the User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ-S) evaluates users' subjective opinions about their experience with a technological product [

63]. It comprises 26 items rated on a 7-point Likert Scale, with pairs of terms having opposite meanings (e.g., annoying vs. innovative, unpredictable). Responses range from -3 (completely disagree with the negative term) to +3 (completely agree with the positive term). The total score, representing the overall user experience, is calculated by summing all responses. It shows strong psychometric properties, with Cronbach’s alpha values between 0.70 and 0.90 and test-retest reliability scores greater than 0.80, demonstrating both internal consistency and reliability [

12,

63].

2.2.3. Service User Technology Acceptability Questionnaire (SUTAQ)

An adapted version of the Service User Technology Acceptability Questionnaire (SUTAQ) was employed to assess the acceptability of the TMT-VR among the target population [

64]. This version of the SUTAQ, tailored for public assessments, consists of 10 items on a 6-point Likert Scale (6 = Strongly Agree, 1 = Strongly Disagree). An example question is, “I am satisfied with the neuropsychological assessment of cognitive functions in virtual reality.” The SUTAQ demonstrates good psychometric properties, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.75 to 0.85, and test-retest reliability greater than 0.70, ensuring both consistency and reliability in its measurements [

12,

64].

2.3. Procedure

The study received approval from the Ad-hoc Ethics Committee of the Psychology Department. Two groups (healthy young adults/young adults with ADHD) were assessed, and participants from each group were exposed to all conditions. The experiment took place in the Psychology Network Lab of the American College of Greece, with all sections conducted in Greek.

At the start of the experiment, participants were seated in front of a computer or laptop screen and asked to follow written instructions. After completing the informed consent form, participants were given the Greek version of the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale to fill out. Once they finished the questionnaire, they were instructed to notify the experimenter and wait for further instructions.

The administration of the tests was counterbalanced for both groups. Half of the participants of each group completed the paper-and-pencil TMT first, while the other half started with the TMT-VR. Counterbalancing was achieved through participant codes that were assigned by the experimenter (odd-numbered participants began with the TMT-VR, even-numbered participants with the traditional TMT). Before each TMT-VR assessment, participants completed the Cybersickness in Virtual Reality Questionnaire.

When the paper-and-pencil TMT was administered first, the experimenter provided the participant with a pencil and gave verbal instructions. The participant was then asked to complete Part A and Part B of the TMT, with each part timed separately using a timer on the experimenter’s mobile phone. The times were recorded in the Qualtrics form by the experimenter. After finishing the paper-and-pencil test, the participant moved to the designated VR area.

In the VR area, the experimenter helped the participant put on the VR headset and headphones. Participants were informed that the experimenter would assist with adjusting the VR headset and guide them to press a button to start the calibration. During the calibration phase, participants focused on a dot on the screen and followed it with their gaze. After calibration, participants had a trial phase that lasted approximately 10-15 minutes in order to ensure familiarity and accuracy with the software and device. During that phase participants listened to instructions for TMT-VR Part A through the headphones, had a short trial before each task, and then proceeded with the actual task. The same procedure was followed for TMT-VR Part B. Throughout the VR tasks, participants were advised they could move their heads to adjust the screen if necessary. After the trial phase, participants were exposed to the actual assessment which only lasted approximately 5-7 minutes and contained the TMT-VR A and TMT-VR B parts without the instructions.

After completing the TMT-VR, participants filled out the Cybersickness in Virtual Reality Questionnaire again. This process was followed for all participants, regardless of the order in which the tests were administered.

After completing the tests and the CSQ-VR, participants were instructed to return to the same screen they used earlier to continue the study. They were then presented with the System Usability Scale, followed by the Short Version of the User Experience Questionnaire, and finally the Service User Technology Acceptability Questionnaire (SUTAQ), in that order. At the end, participants were given a debriefing statement.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software [

65] within the RStudio environment [

66]. The dataset was first examined for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and variables that were not normally distributed were transformed where necessary using the bestNormalize package [

67]. Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations (SD), and ranges, were calculated for all demographic variables, task performance metrics, and user feedback scores. All data visualizations were created using the ggplot2 package [

68], which provided detailed graphical representations of the key findings, including group differences and correlations.

2.4.1. Usability, User Experience, and Acceptability

Frequencies were calculated to analyze responses on the usability (SUS), user experience (UEQ-S), and acceptability (SUTAQ) scales. Pearson’s correlations were conducted to explore relationships between performance on TMT-VR tasks (task time, accuracy) and self-reported scores on these scales. The results were visualized using scatterplots and correlation matrices created with ggplot2 [

68] and corrplot [

69].

2.4.2. Independent Samples t-Tests

Independent samples t-tests were conducted to compare performance metrics (task time, accuracy, and mistakes) between individuals diagnosed with ADHD and neurotypical individuals. Separate t-tests were performed for both TMT-VR tasks (A and B) as well as the traditional paper-and-pencil TMT. The t-tests also compared ASRS scores between the two groups to evaluate group differences.

2.4.3. Repeated Measures ANOVA

A repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to assess potential differences in task time, accuracy, and mistakes between the TMT-VR and traditional TMT tasks. Group (ADHD vs. neurotypical) was included as a between-subjects factor. For significant effects, post-hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted using the Bonferroni correction to account for multiple comparisons. The ANOVA was conducted using the afex package [

70], and effect sizes were reported as partial eta-squared (η²p). Significance was determined at p < .05.

2.4.4. Correlation Analyses

Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated to explore relationships between demographic variables (e.g., age, education) and performance metrics (e.g., task time, accuracy) across both TMT-VR and paper-and-pencil versions. Additionally, correlations were analyzed between performance outcomes and self-reported scores from the ASRS and user feedback scores (SUS, UEQ-S, SUTAQ). Correlation matrices were visualized using the corrplot package [

69] to provide a clear summary of these relationships.

2.4.5. Linear Regression Analysis

To further examine the ecological validity of the TMT-VR, linear regression analyses were performed to assess the predictive power of TMT-VR performance (accuracy and task time) on ASRS scores. The models included accuracy and task time from both TMT-VR A and TMT-VR B as predictors, and a hierarchical approach was used to determine the best predictors of ASRS scores. The percentage of variance explained by the model (R²) and standardized beta coefficients (β) were reported for each predictor, with significance set at p < .05. The regression analysis was performed using the lm function in base R.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

The sample consisted of 53 Greek-speaking young adults, with 47.17% (N = 25) diagnosed with ADHD and 52.83% (N = 28) classified as neurotypical. Participants' ages ranged from 18 to 40 years (M = 23.87, SD = 3.82), with total years of education ranging from 12 to 22 (M = 15.98, SD = 3.26). Slightly higher educational attainment was observed among ADHD participants (M = 16.72, SD = 2.49) compared to neurotypical participants (M = 15.32, SD = 3.74).

Table 1 portrays the descriptive statistics of the participants.

3.2. Usability, User Experience, and Acceptability

Usability, user experience, and acceptability ratings for the TMT-VR were notably high. For usability, 64.15% of participants responded the highest quartile, with an additional 33.96% in the third quartile, indicating widespread positive ratings. For user experience, 56.60% of responses were in the highest quartile, while 41.50% were in the third quartile. Acceptability ratings followed a similar pattern, with 66.03% of participants reporting scores in the highest quartile and 28.30% in the third quartile.

Significant negative correlations were found between task time on the TMT-VR and usability (SUS) scores, with TMT-VR A, r(51) = -.312, p = .023, and TMT-VR B, r(51) =- .291, p = .034, indicating that participants who completed the tasks more quickly rated the system higher in terms of usability. Similar negative correlations were found between user experience (UEX-S) scores and task time, further suggesting that efficient task performance was linked to better overall user experience.

A significant negative correlation between acceptability (SUTAQ) scores and TMT-VR A task time, r(51) = -.291, p = .035, revealed that participants who completed the task more quickly also rated the software higher in terms of acceptability, reflecting a more favorable perception of the technology among those who performed well.

3.3. Performance on TMT-VR and TMT

For TMT-VR A, accuracy scores ranged from 0.152 to 0.318 (M = 0.185, SD = 0.057), task times ranged from 38.17 to 142.44 seconds (M = 83.84, SD = 26.80), and the number of mistakes ranged from 0 to 14 (M = 1.15, SD = 2.37). For TMT-VR B, accuracy scores ranged from 0.151 to 0.313 (M = 0.185, SD = 0.056), task times varied from 43.68 to 171.15 seconds (M = 98.61, SD = 28.20), and the number of mistakes ranged from 0 to 14 (M = 1.59, SD = 2.47).

Self-reported scores on the System Usability Scale (SUS) ranged from 29 to 49 (M = 41.21, SD = 5.10). User experience scores, measured using the UEQ-S, ranged from 101 to 174 (M = 143.55, SD = 19.50), and acceptability (measured via SUTAQ) ranged from 20 to 60 (M = 49.11, SD = 8.55). ADHD symptomatology was assessed via the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS), with scores ranging from 33 to 74 (M = 57.53, SD = 9.55). Importantly, reported cybersickness symptoms were either absent or mild for all participants, suggesting that cybersickness did not interfere with task performance.

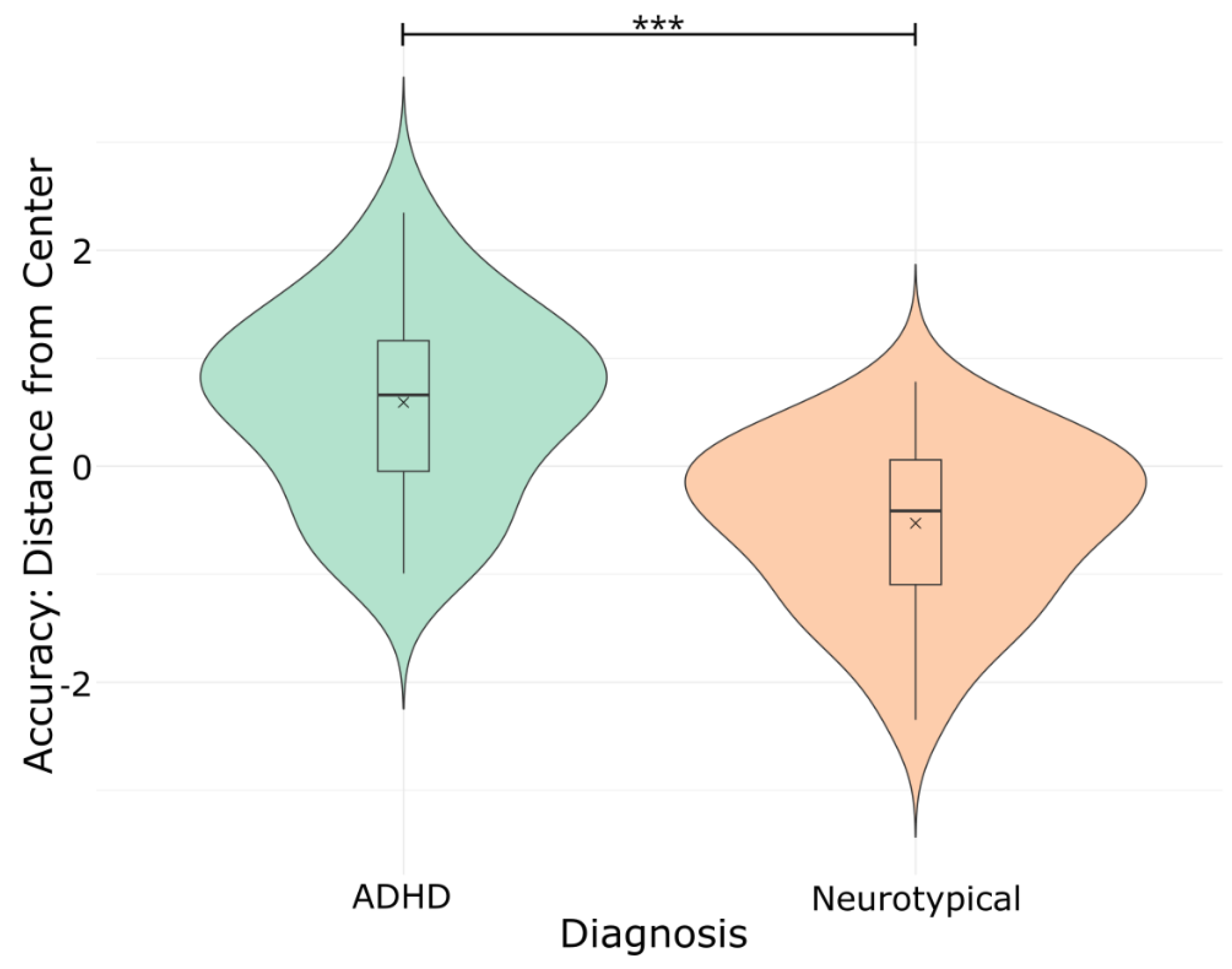

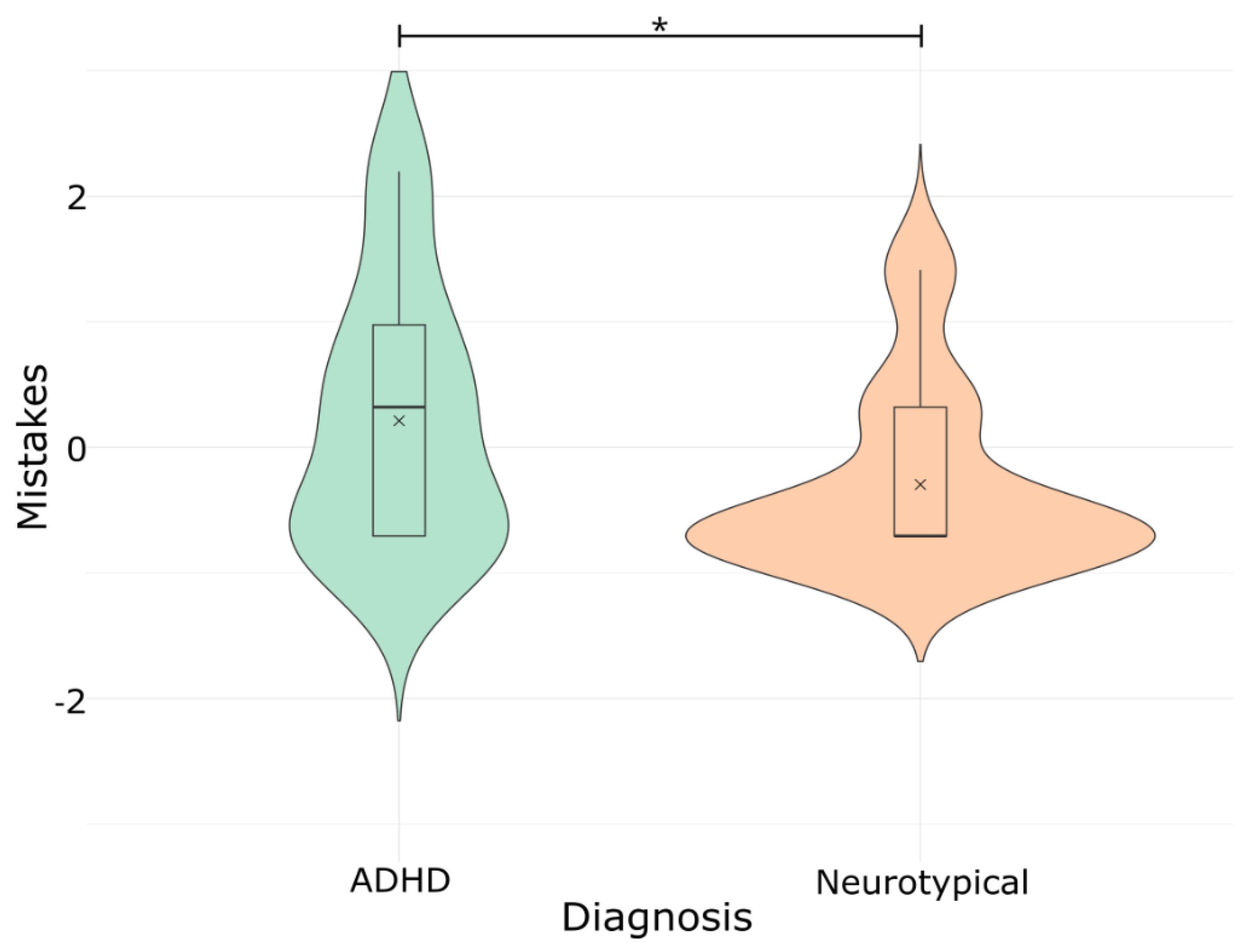

3.3.1. Group Comparisons: ADHD vs. Neurotypical

In

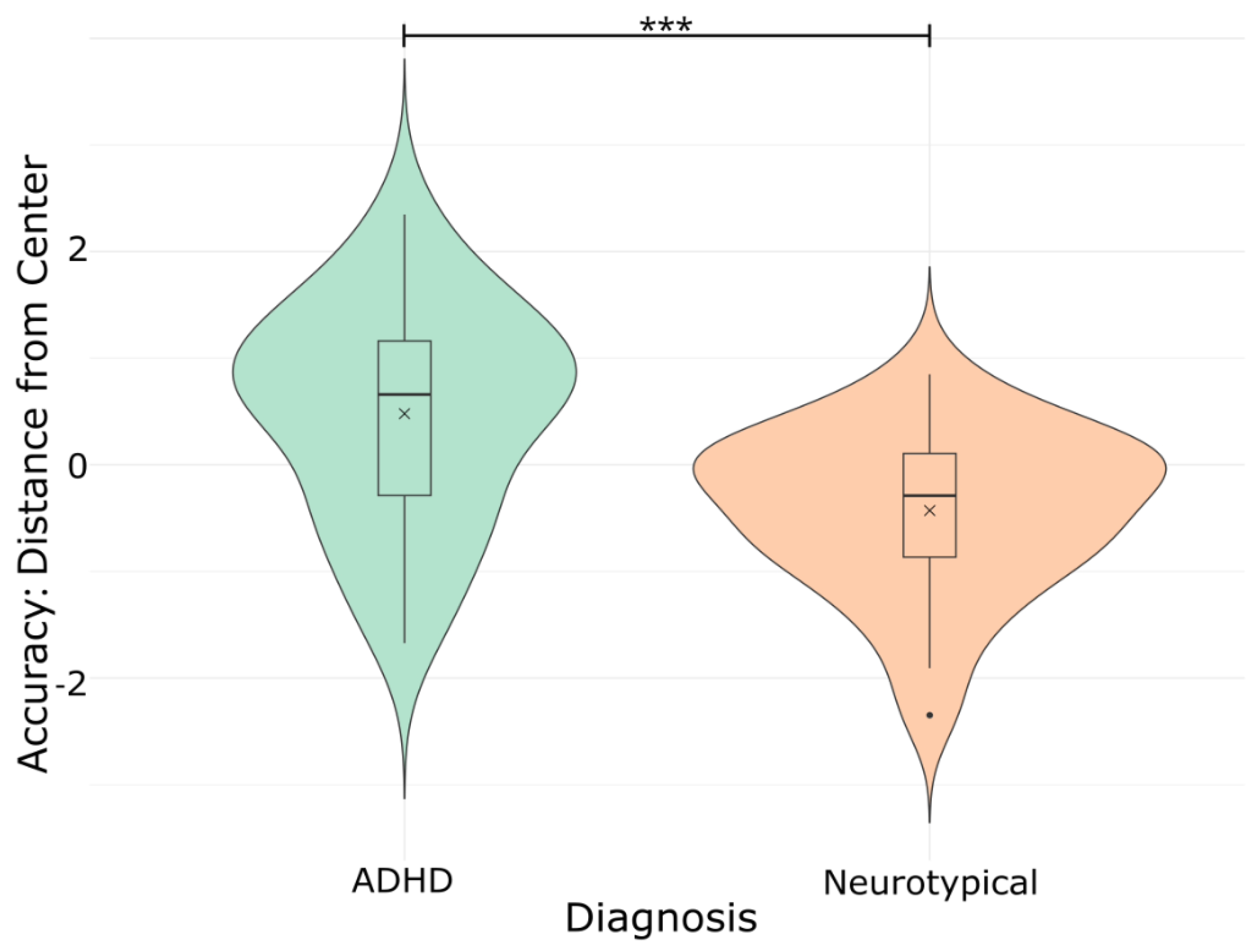

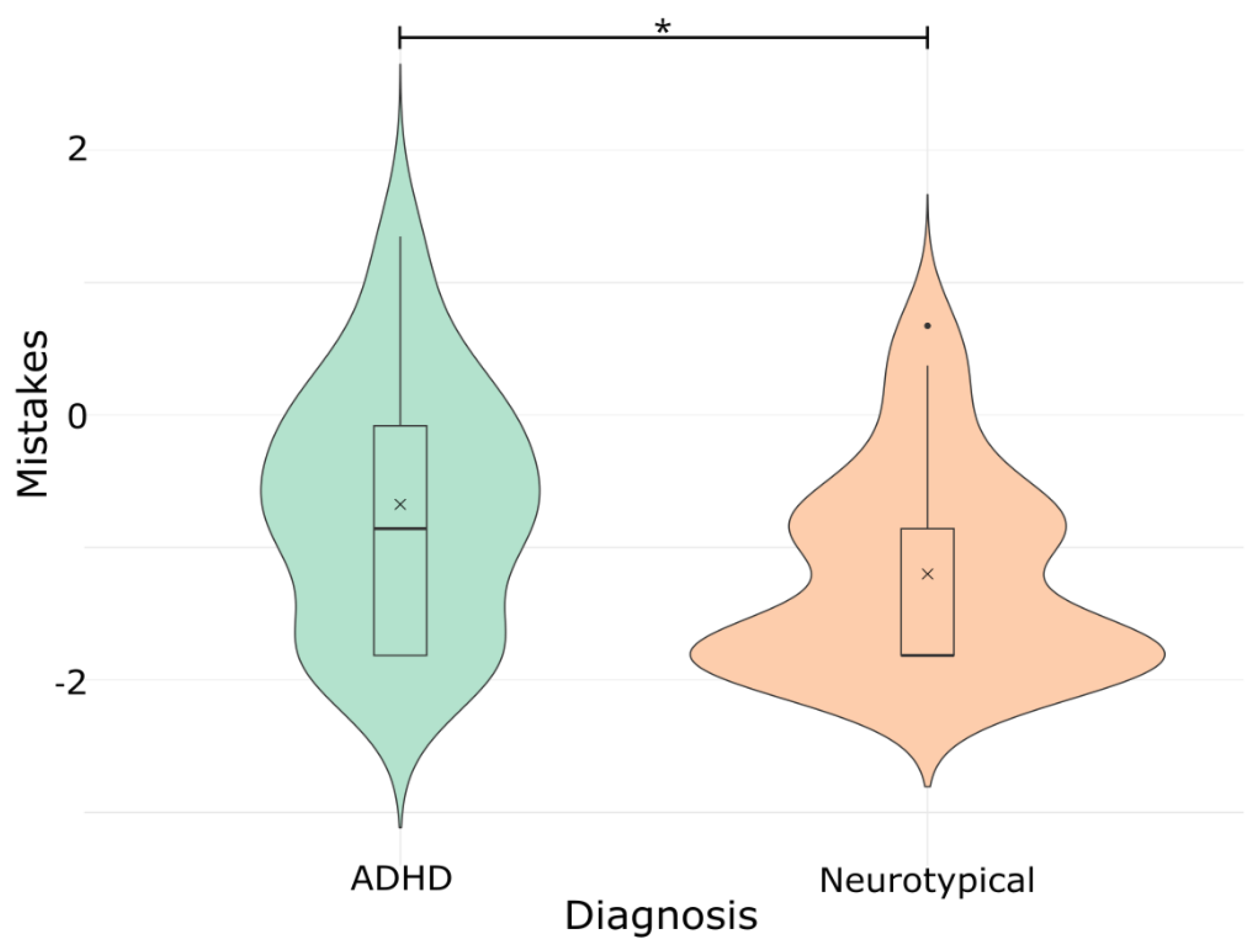

Table 2, the performance metrics are presented for the two diagnostic groups (i.e., ADHD vs. Neurotypical). Independent samples t-tests were conducted to compare performance between ADHD and neurotypical participants across TMT and TMT-VR tasks. No significant differences were observed between the groups in terms of task time on either the paper-and-pencil TMT or TMT-VR (p > .05). However, significant differences were found in accuracy, the number of mistakes, and cognitive control in both TMT-VR A and TMT-VR B (See

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

For TMT-VR A, ADHD participants demonstrated significantly lower accuracy than neurotypical individuals (see

Figure 2), t(51) = 4.26, p < .001, and made significantly more mistakes (see

Figure 3), t(51) = 2.19, p = .017. Similarly, in TMT-VR B, ADHD participants performed with lower accuracy (see

Figure 4), t(51) = 4.22, p < .001, and made more mistakes (see

Figure 5), t(51) = 1.99, p = .026. In contrast, no significant group differences were found in terms of mistakes on the paper-and-pencil TMT (p > .05), highlighting the stronger ecological validity and discriminatory power of the TMT-VR for distinguishing attentional deficits.

To further examine attentional challenges, ASRS scores were compared between the groups. As expected, ADHD participants scored significantly higher on the ASRS, t(51) = 3.53, p < .001, reflecting greater attentional difficulties and everyday impairments in the ADHD group.

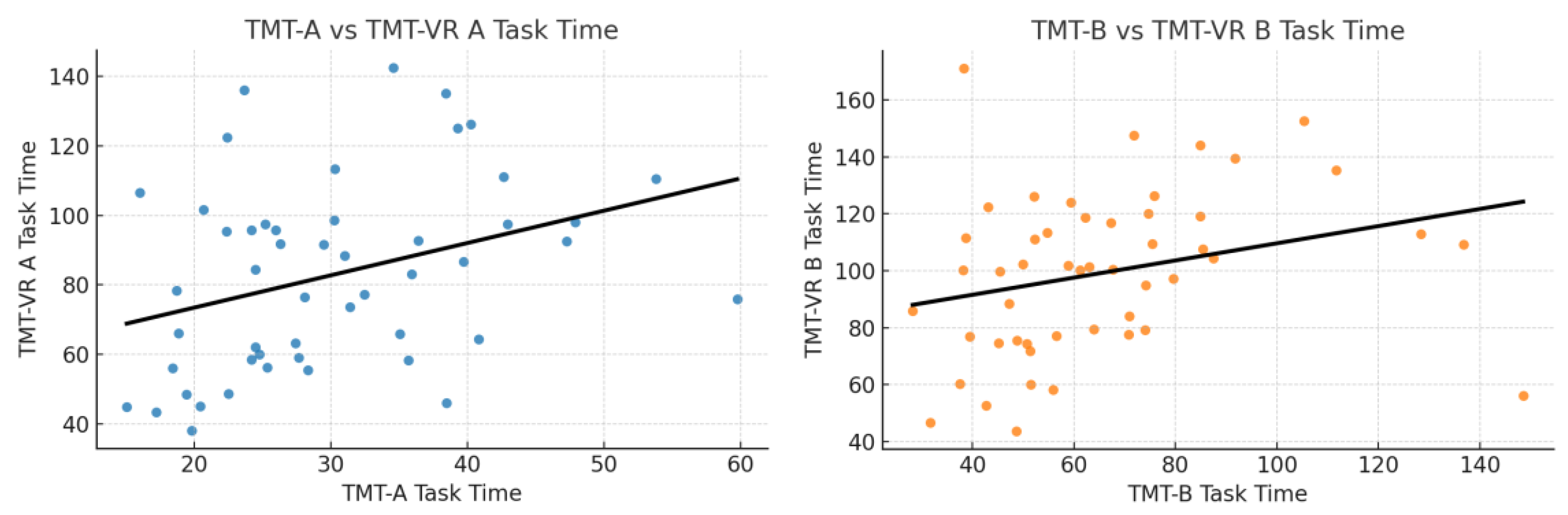

3.4. Convergent Validity

Pearson’s correlations were performed to evaluate convergent validity by comparing performance on the TMT and TMT-VR. A significant positive correlation was found between task times for TMT-A and TMT-VR A, r(51) = .360, p = .004, as well as between TMT-B and TMT-VR B, r(51) = .281, p = .021. These findings suggest strong convergent validity (see

Figure 6), with performance on the VR adaptation aligning with performance on the traditional paper-and-pencil test. Additional significant correlations were observed between TMT A and TMT B (r(51) = .587, p < .001) and between TMT-VR A and TMT-VR B (r(51) = .391, p = .003), further confirming consistency across traditional and VR-based cognitive tasks.

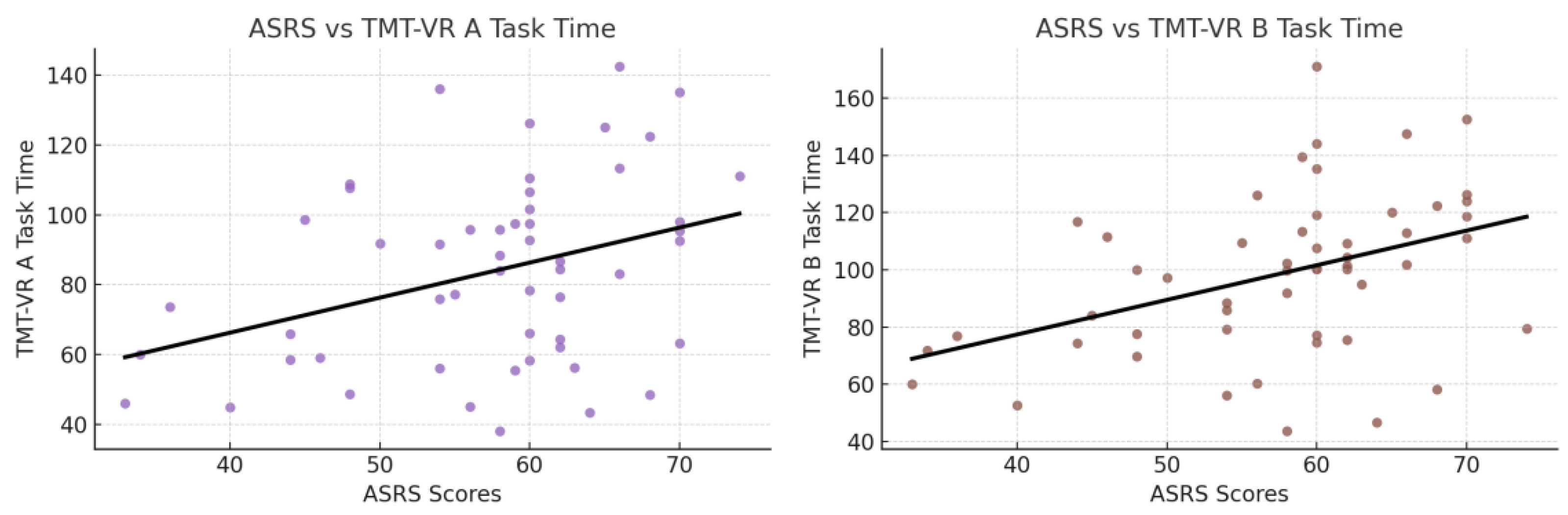

3.5. Ecological Validity

Ecological validity was assessed through correlations between TMT-VR performance and ASRS scores. Significant positive correlations were observed between ASRS scores and TMT-VR A task time, r(51) = .358, p = .004, as well as between ASRS scores and TMT-VR B task time, r(51) = .411, p = .001. This indicates that participants with higher ASRS scores—indicative of more severe attentional deficits—took longer to complete the TMT-VR tasks, suggesting that TMT-VR performance accurately reflects everyday attentional challenges (see

Figure 7).

Significant positive correlations were found between ASRS scores and TMT-VR accuracy and mistakes, further supporting the ecological validity of the TMT-VR. Specifically, ASRS scores were significantly positively correlated with TMT-VR A accuracy r(51) = 0.331, p = 0.008, and TMT-VR B accuracy r(51) = 0.325, p = 0.009. Additionally, a positive correlation was found between ASRS scores and TMT-VR A mistakes r(51) = 0.248, p = 0.036, highlighting the ability of the TMT-VR to capture attentional difficulties. This association with real-world impairments, as measured by the ASRS, further supports the ecological validity of the TMT-VR.

Interestingly, traditional TMT task performance showed a significant negative correlation with years of education, with TMT-A task time r(51) = −0.263, p = 0.029, and TMT-B task time r(51) = −0.278, p = 0.022, decreasing as years of education increased. In contrast, no significant correlation was found between education and TMT-VR performance p > 0.05, suggesting that educational background influenced performance on the traditional TMT but not the TMT-VR. This further supports the ecological validity of the TMT-VR, as it appears to offer a more realistic measure of cognitive functioning unaffected by educational disparities.

3.5.1. Regression Analyses for Predicting ASRS Scores

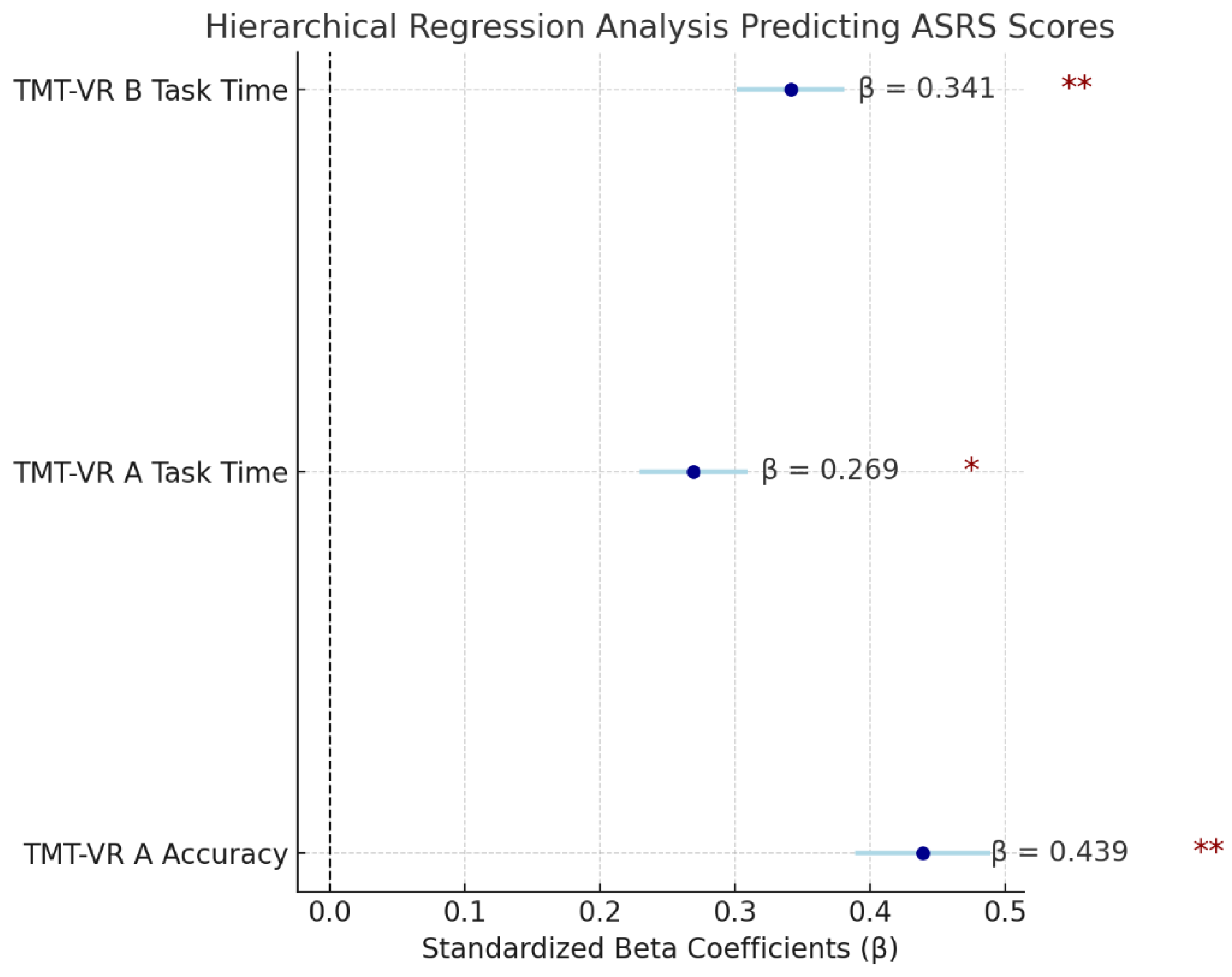

A hierarchical linear regression was performed to explore the ability of TMT-VR task performance (task time, accuracy, and mistakes) to predict attentional challenges, as measured by ASRS scores. The model accounted for 38.1% of the variance in ASRS scores, F(3, 49) = 10.10, p < .001, indicating that TMT-VR performance metrics are robust predictors of everyday attentional difficulties.

Crucially, demographic variables (age, years of education), as well as traditional TMT performance metrics, were not significant contributors to the final model. Only TMT-VR metrics were included, underscoring the superior predictive power of the VR version over the traditional task. The exclusion of demographic factors highlights the ability of TMT-VR to provide an accurate reflection of attentional challenges across diverse populations, independent of age or educational background.

Among the significant predictors, TMT-VR A accuracy emerged as the strongest predictor of ASRS scores (β = .439, p < .001), followed by TMT-VR A task time (β = .269, p = .012) and TMT-VR B task time (β = .341, p = .003). These results suggest that higher accuracy and faster task completion in the TMT-VR are associated with lower ASRS scores, indicating fewer attentional challenges. Accuracy in TMT-VR A being the most significant predictor reflects the importance of precise cognitive control in real-world attentional functioning.

In summary, the fact that neither demographic variables nor traditional TMT scores were significant predictors further reinforces the ecological validity of the TMT-VR, which seems to better capture attentional deficits in a manner reflective of everyday functioning, unlike the traditional, lab-based assessments.

Figure 8.

Standardized Beta Coefficients of the Predictors in the Best Model of ASRS.

Figure 8.

Standardized Beta Coefficients of the Predictors in the Best Model of ASRS.

4. Discussion

The present study represents the first exploration of the validity of the TMT-VR, an innovative adaptation of the traditional TMT, within a clinical population of individuals diagnosed with ADHD. Beyond examining the TMT-VR’s psychometric properties, the study also delved into participants' perceptions regarding the usability, acceptability, and overall user experience of the software. The findings were highly encouraging, as the TMT-VR demonstrated strong ecological and convergent validity, providing a robust measure of cognitive functioning that is relevant to real-world contexts. This enhanced ecological validity is particularly important given the limitations of traditional neuropsychological assessments, which often fail to replicate the complexities of everyday life. In terms of usability and acceptability, the TMT-VR received favorable ratings from participants, with nearly all responses clustering in the upper quartiles of the evaluation scales, indicating that users found the system intuitive, easy to navigate, and acceptable for use in clinical assessments. Notably, none of the participants reported experiencing VRISE symptoms such as nausea, fatigue, or disorientation, further demonstrating that the TMT-VR is both a feasible and comfortable tool for clinical and research use.

The psychometric instruments used in this study, such as the ASRS, were found to be reliable and valid measures of cognitive functioning. The ASRS, a widely used tool for assessing ADHD symptoms, was shown to be a strong predictor of attentional difficulties, which aligns with previous research findings [

32]. The traditional TMT has also been validated as an effective measure of cognitive performance across both clinical and non-clinical populations [

32], providing a robust benchmark for evaluating the TMT-VR. Interestingly, no significant differences were found in task completion times between neurotypical participants and those with ADHD on the TMT-VR. This suggests that, in an immersive virtual reality environment, individuals with ADHD may perform similarly to their neurotypical counterparts, potentially due to the increased engagement and real-life simulation that the VR environment provides. This result may indicate that the TMT-VR reduces cognitive load or increases participant motivation, offering a more representative measure of real-world performance, especially in tasks that require sustained attention and cognitive flexibility. Furthermore, the lack of significant differences in task completion times between neurotypical and neurodivergent participants on the TMT-VR could be related to the characteristics of the virtual reality environment. The immersive nature of VR environments might limit external distractions that are commonly present in non-virtual or real-world settings. Individuals with ADHD often struggle with attention and increased cognitive load due to external distractors, which in this case could be minimized, due to the controlled VR environment.

Despite the lack of significant differences in task time, the study revealed clear group differences in terms of accuracy and the number of mistakes made in the TMT-VR, with neurotypical participants outperforming those with ADHD in both metrics. This finding affirms the TMT-VR’s discriminatory power, as it was able to effectively distinguish between the two groups based on cognitive performance. The observed differences in accuracy and mistakes may reflect the attentional and executive functioning deficits that characterize ADHD, deficits that traditional assessments may not fully capture. Interestingly, these differences were not observed in the traditional TMT, further underscoring the superiority of the TMT-VR in terms of ecological validity. The immersive and interactive nature of the TMT-VR likely contributes to its enhanced sensitivity in detecting cognitive impairments, particularly in domains such as attention, task-switching, and cognitive flexibility. By providing a dynamic and engaging environment that more closely mimics real-world conditions, the TMT-VR offers a more accurate assessment of cognitive functioning, making it a valuable tool for clinicians seeking to diagnose and treat ADHD and similar conditions.

4.1. Usability, User Experience, Acceptability

In line with previous findings on the usability, user experience, and acceptability of virtual reality-based neuropsychological measures, such as the VRESS [

12], this study revealed that the TMT-VR received similarly high scores in these areas from young adult participants. The importance of evaluating participants’ perceptions of technological properties in VR assessments is often overlooked in neuropsychological research [

57,

58]. However, by including these factors, this study provides a more comprehensive understanding of how users interact with and perceive the system, offering valuable insights into its potential for both research and clinical applications. Understanding these dimensions is critical, as technological properties such as usability can directly impact user engagement and task performance [

56].

System usability, as measured by the SUS, focuses on key aspects such as effectiveness, efficiency, and comfort during use [

62]. The participants gave high usability ratings, suggesting that the TMT-VR is both intuitive and highly functional. Design features, such as the eye-tracking interaction mode, allowed participants to navigate the tasks without using their hands or other body parts, simplifying the process and reducing cognitive and physical effort. Research indicates that minimizing physical and cognitive demands in VR can enhance user experience, especially in populations that may face additional cognitive challenges [

10]. These findings suggest that the TMT-VR is effective and easy to use, requiring little improvement in terms of interface or design, making it suitable for diverse settings, including clinical environments [

5].

Similarly, the UEQ-S assessed various aspects of participants' interaction with the TMT-VR, including its immersive quality, ease of use, and enjoyment. Participants rated their experience in the highest quartiles. Positive user experiences are essential in VR-based assessments, as high immersion and engagement can improve task performance [

9]. Immersive environments can also improve motivation and reduce fatigue during cognitive tasks, which is particularly important when assessing individuals with attentional disorders like ADHD [

50]. The high ratings on these dimensions suggest that the TMT-VR effectively engages users, supporting its use as an ecologically valid neuropsychological tool.

Finally, the acceptability of the TMT-VR, as measured by the SUTAQ scale, was also rated highly, suggesting that participants view the system as a suitable and reliable instrument for neuropsychological evaluation. Even though the study sample consisted of non-clinical participants, their positive feedback indicates that the TMT-VR could be well-received in clinical settings as well. Previous studies have shown that the acceptance of VR-based tools in clinical populations can be influenced by usability and engagement factors [

3,

11]. The TMT-VR’s combination of ease of use, immersive engagement, and minimal adverse effects (such as VRISE) makes it a promising tool for broader clinical applications, particularly in populations with cognitive or attentional deficits. Furthermore, its ability to provide real-world, interactive environments addresses the limitations of traditional paper-and-pencil assessments [

5,

11,

56].

4.1.1. Virtual Reality in Neurodivergent Individuals

Existing literature on the clinical application of virtual reality (VR) tools has increasingly confirmed their efficiency and potential in neurodivergent populations. Although research in this area remains somewhat limited, interest is growing rapidly, driven by the promising outcomes of preliminary studies. For example, research on the use of VR for social skills training in individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) has shown very positive results. One study found that participants rated the technological properties of the VR tool very highly, particularly in terms of usability, acceptability, and user experience [

21]. These findings suggest that VR can provide an engaging and effective platform for both assessment and intervention, opening up new possibilities for innovative methods to support neurodivergent individuals, especially in clinical settings. The findings of this study are consistent with the growing body of evidence supporting the use of VR-based tools for assessing cognitive performance in individuals with ADHD, as well as enhancing executive functioning and reducing ADHD symptoms [

51]. The TMT-VR demonstrated strong validity and was well-received by participants, reflecting its potential as an effective tool for evaluating cognitive functions such as attention, memory, and executive function in a controlled, yet immersive environment. Previous studies have emphasized the importance of integrating eye-tracking and body movement into these assessments, as they can provide deeper insights into cognitive and behavioral functions in neurodivergent populations [

71].

In line with previous research, the current study employed eye-tracking as the primary interaction mode for the TMT-VR, based on evidence supporting its effectiveness in measuring attention and executive function deficits. Research has shown that eye movement can serve as a reliable predictor of cognitive performance, offering a non-invasive and intuitive way to assess attention, task-switching, and other executive functions [

71]. The decision to use eye-tracking in the TMT-VR was informed by these findings, particularly studies suggesting that eye-tracking is an optimal interaction mode for assessing both clinical and non-clinical populations [

30]. By capturing subtle variations in gaze and visual attention, eye-tracking enhances the ecological validity of VR-based assessments, making them more reflective of real-world cognitive challenges. This method also aligns with broader trends in neuropsychological research that emphasize the need for more immersive, interactive, and contextually relevant tools for assessing cognitive performance in neurodivergent individuals [

5,

11].

4.2. Convergent Validity

The TMT-VR inherently includes several advantages over the traditional paper-and-pencil version, including the elimination of human error during test administration and result calculation, standardization of test conditions, and millisecond accuracy in recording task performance. It also captures detailed performance indices, such as median and standard deviation of task completion times which are critical in understanding attention lapses and variations in cognitive performance, particularly in clinical populations such as those with ADHD [

72]. The ability of the TMT-VR to capture these fine-grained metrics provides a deeper and more precise assessment of cognitive functions compared to traditional methods.

As anticipated, both TMT-VR tasks demonstrated significant correlations with their paper-and-pencil counterparts, indicating satisfactory levels of convergent validity and confirming the TMT-VR's reliability in measuring the same cognitive constructs. This supports its use as an alternative to traditional methods [

73]. While test format differences can affect convergence [

73], prior research research has shown that VR-based neuropsychological tools often align well with traditional assessments [

5,

8,

12,

74].

These findings suggest that the TMT-VR is a reliable, valid, and precise tool for cognitive assessment, consistent with previous validations of alternative TMT forms, such as computerized versions and the Color Trail Test [

25,

75].

]. Unlike studies that require expensive equipment [

25], the TMT-VR developed in this study is practical and accessible, utilizing affordable VR technology for broader clinical use. As the first immersive VR variant of the TMT, it offers a dynamic, ecologically valid alternative for cognitive assessment that can be readily adopted in research and clinical settings [

24].

4.3. Ecological Validity

Immersive VR technologies are increasingly recognized for their capacity to create engaging, realistic environments that enhance the ecological validity of cognitive assessments [

4,

9,

21,

25,

56]. Unlike traditional paper-and-pencil tests, which are often limited by their artificial and controlled settings, VR assessments can simulate complex, real-life scenarios, allowing for a more accurate evaluation of cognitive functions, such as attention, memory, and executive function [

76,

77]. Previous studies, such as those using tools like the Nesplora Aquarium and VR-EAL, have demonstrated strong psychometric properties and superior ecological validity compared to traditional methods [

4,

78]. These findings suggest that VR-based assessments are particularly valuable for measuring real-world performance in clinical populations, including individuals with ADHD [

50,

52].

This study builds on these findings by examining both verisimilitude and veridicality—two key aspects of ecological validity. While previous research has often focused on verisimilitude, or how closely a VR task resembles real-world activities, our study also assessed veridicality, which examines the ability of an instrument's scores to predict everyday performance [

2]. In this context, the TMT-VR’s scores were compared to those of the ASRS, a well-validated measure of attentional and everyday cognitive functioning, revealing a significant correlation between the two.

By demonstrating strong verisimilitude and veridicality, the TMT-VR not only effectively simulates real-world conditions but also accurately predicts everyday cognitive performance in individuals with ADHD. These findings highlight the TMT-VR's potential as a more ecologically valid tool compared to traditional neuropsychological assessments, providing deeper insights into cognitive functioning within naturalistic settings.

4.4. Limitations and Future Studies

While the current study offers valuable insights into the validity of the TMT-VR as a neuropsychological assessment tool, certain areas warrant further exploration. Although the sample size was relatively modest, the findings provide a strong foundation for future research. Expanding the sample to include a larger, more diverse population would help to solidify the generalizability of the results. Additionally, as the study primarily involved young adults, it would be beneficial to investigate how the TMT-VR performs across different age groups. This would help determine whether the tool is equally effective in assessing cognitive functions throughout various stages of life, from adolescence to older adulthood.

As this study focused on individuals with ADHD, future research could broaden its scope by exploring the TMT-VR’s applicability in other clinical populations. For example, assessing individuals with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), dementia, or traumatic brain injury would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the TMT-VR’s utility as a clinical assessment tool. Validating the TMT-VR in these contexts could highlight its potential as a versatile and reliable instrument for measuring cognitive impairments across a range of conditions. Furthermore, investigating the tool’s long-term reliability, including test-retest consistency, would be a valuable next step to ensure its robustness for repeated clinical use.

Looking ahead, future studies might also explore additional interaction modes, such as hand tracking or gesture control, to further enhance the flexibility and adaptability of the TMT-VR. These advancements could make the tool more inclusive and applicable to populations with different physical and cognitive abilities, further expanding its clinical utility. By continuing to refine and validate the TMT-VR in diverse populations and settings, future research can ensure that this innovative tool reaches its full potential in neuropsychological assessment.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study provide significant insights into the validity and potential of the TMT-VR as an innovative tool for neuropsychological assessments, particularly in clinical populations such as individuals with ADHD. Both the ecological and convergent validity of the TMT-VR were found to be strong, demonstrating the instrument’s capability to serve as an effective clinical assessment tool. The TMT-VR’s ability to capture real-world cognitive challenges, especially attentional deficits and executive dysfunctions, highlights its superiority over traditional paper-and-pencil assessments, which often lack ecological validity.

Furthermore, the high ratings of usability, user experience, and acceptability indicate that participants found the TMT-VR to be an intuitive, engaging, and well-received platform. These positive attitudes suggest that the TMT-VR has strong potential for integration into neuropsychological practice, where user engagement is critical for accurate assessments. The immersive and interactive nature of the TMT-VR not only enhances the assessment experience but also provides clinicians with a more ecologically valid tool to evaluate cognitive functions in real-world contexts.

Overall, the promising findings from this study lay the groundwork for future research into the application of virtual reality technologies in both research and clinical settings. As VR continues to evolve, its role in neuropsychological assessments is likely to expand, offering more accurate, immersive, and engaging methods for evaluating cognitive functions in diverse populations. Future research should further investigate the utilization of VR technologies, ensuring that tools like the TMT-VR become widely accepted and implemented in clinical practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.G. and P.K.; methodology, K.G. and P.K.; software, P.K.; validation, K.G., E.G., R.K., I.B., C.N., and P.K.; formal analysis, K.G. and P.K.; investigation, K.G., E.G., and R.K.; resources, I.B., C.N., and P.K.; data curation, K.G., E.G., and R.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.G., E.G., R.K., and P.K.; writing—review and editing, K.G., E.G., R.K., I.B., C.N., and P.K.; visualization, P.K.; supervision, P.K.; project administration, I.B., C.N., and P.K.; funding acquisition, I.B., C.N., and P.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ad-hoc Ethics Committee of the Psychology Department of the American College of Greece (KG/0224, 28/02/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical approval requirements.

Acknowledgments

The study received financial support by the ACG 150 Annual Fund. Dr. Panagiotis Kourtesis designed and developed the TMT-VR.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chaytor, N.; Schmitter-Edgecombe, M. The Ecological Validity of Neuropsychological Tests: A Review of the Literature on Everyday Cognitive Skills. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2003, 13, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spooner, D.M.; Pachana, N.A. Ecological Validity in Neuropsychological Assessment: A Case for Greater Consideration in Research with Neurologically Intact Populations. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2006, 21, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourtesis, P.; Korre, D.; Collina, S.; Doumas, L.; MacPherson, S. Guidelines for the Development of Immersive Virtual Reality Software for Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuropsychology: The Development of Virtual Reality Everyday Assessment Lab (VR-EAL), a Neuropsychological Test Battery in Immersive Virtual Reality. Front. Comput. Sci. 2020, 1, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtesis, P.; Collina, S.; Doumas, L.A.A.; MacPherson, S.E. Validation of the Virtual Reality Everyday Assessment Lab (VR-EAL): An Immersive Virtual Reality Neuropsychological Battery with Enhanced Ecological Validity. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2021, 27, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtesis, P.; MacPherson, S.E. How Immersive Virtual Reality Methods May Meet the Criteria of the National Academy of Neuropsychology and American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology: A Software Review of the Virtual Reality Everyday Assessment Lab (VR-EAL). Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2021, 4, 100151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaytor, N.; Schmitter-Edgecombe, M.; Burr, R. Improving the Ecological Validity of Executive Functioning Assessment. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2006, 21, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtesis, P.; F, A.; Vizcay, S.; Marchal, M.; Pacchierotti, C. Electrotactile Feedback Applications for Hand and Arm Interactions: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Future Directions. IEEE Trans. Haptics 2022, 15, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davison, S.M.C.; Deeprose, C.; Terbeck, S. A Comparison of Immersive Virtual Reality with Traditional Neuropsychological Measures in the Assessment of Executive Functions. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2018, 30, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skurla, M.D.; Rahman, A.T.; Salcone, S.; Mathias, L.; Shah, B.; Forester, B.P.; Vahia, I.V. Virtual Reality and Mental Health in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2022, 34, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.; Han, J.; Choi, H.; Prié, Y.; Vigier, T.; Bulteau, S.; Kwon, G.H. Examining the Academic Trends in Neuropsychological Tests for Executive Functions Using Virtual Reality: Systematic Literature Review. JMIR Serious Games 2021, 9, e30249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, T. Virtual Reality for Enhanced Ecological Validity and Experimental Control in the Clinical, Affective, and Social Neurosciences. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourtesis, P.; Kouklari, E.-C.; Roussos, P.; Mantas, V.; Papanikolaou, K.; Skaloumbakas, C.; Pehlivanidis, A. Virtual Reality Training of Social Skills in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Examination of Acceptability, Usability, User Experience, Social Skills, and Executive Functions. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsey, C.M.; Schmitter-Edgecombe, M. Applications of Technology in Neuropsychological Assessment. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2013, 27, 1328–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huygelier, H.; Schraepen, B.; van Ee, R.; Vanden Abeele, V.; Gillebert, C.R. Acceptance of Immersive Head-Mounted Virtual Reality in Older Adults. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaidi, F.; Duthie, C.; Carr, E.; Hassan, S. Conceptual Framework for the Usability Evaluation of Gamified Virtual Reality Environment for Non-Gamers; 2018; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Doré, B.; Gaudreault, A.; Everard, G.; Ayena, J.; Abboud, A.; Robitaille, N.; Batcho, C.S. Acceptability, Feasibility, and Effectiveness of Immersive Virtual Technologies to Promote Exercise in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sensors 2023, 23, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohil, C.J.; Alicea, B.; Biocca, F.A. Virtual Reality in Neuroscience Research and Therapy. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 12, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmisano, S.; Mursic, R.; Kim, J. Vection and Cybersickness Generated by Head-and-Display Motion in the Oculus Rift. Displays 2017, 46, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtesis, P.; Amir, R.; Linnell, J.; Argelaguet, F.; MacPherson, S.E. Cybersickness, Cognition, & Motor Skills: The Effects of Music, Gender, and Gaming Experience. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2023, 29, 2326–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtesis, P.; Papadopoulou, A.; Roussos, P. Cybersickness in Virtual Reality: The Role of Individual Differences, Its Effects on Cognitive Functions and Motor Skills, and Intensity Differences during and after Immersion. Virtual Worlds 2024, 3, 62–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtesis, P.; Linnell, J.; Amir, R.; Argelaguet, F.; MacPherson, S.E. Cybersickness in Virtual Reality Questionnaire (CSQ-VR): A Validation and Comparison against SSQ and VRSQ. Virtual Worlds 2023, 2, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtesis, P.; Collina, S.; Doumas, L.; MacPherson, S. Validation of the Virtual Reality Neuroscience Questionnaire: Maximum Duration of Immersive Virtual Reality Sessions Without the Presence of Pertinent Adverse Symptomatology. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashendorf, L.; Jefferson, A.L.; O’Connor, M.K.; Chaisson, C.; Green, R.C.; Stern, R.A. Trail Making Test Errors in Normal Aging, Mild Cognitive Impairment, and Dementia. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2008, 23, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowie, C.R.; Harvey, P.D. Administration and Interpretation of the Trail Making Test. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 2277–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotnik, M.; Doniger, G.M.; Bahat, Y.; Gottleib, A.; Gal, O.B.; Arad, E.; Kribus-Shmiel, L.; Kimel-Naor, S.; Zeilig, G.; Schnaider-Beeri, M.; et al. Immersive Trail Making: Construct Validity of an Ecological Neuropsychological Test. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Virtual Rehabilitation (ICVR); June 19 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Marije Boonstra, A.; Oosterlaan, J.; Sergeant, J.A.; Buitelaar, J.K. Executive Functioning in Adult ADHD: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychol. Med. 2005, 35, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, S.M.H.; Butzbach, M.; Fuermaier, A.B.M.; Weisbrod, M.; Aschenbrenner, S.; Tucha, L.; Tucha, O. Basic and Complex Cognitive Functions in Adult ADHD. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0256228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatar, Z.B.; Cansız, A. Executive Function Deficits Contribute to Poor Theory of Mind Abilities in Adults with ADHD. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2022, 29, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yurtbaşı, P.; Aldemir, S.; Teksin Bakır, M.G.; Aktaş, Ş.; Ayvaz, F.B.; Piştav Satılmış, Ş.; Münir, K. Comparison of Neurological and Cognitive Deficits in Children With ADHD and Anxiety Disorders. J. Atten. Disord. 2018, 22, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giatzoglou, E.; Vorias, P.; Kemm, R.; Karayianni, I.; Nega, C.; Kourtesis, P. The Trail-Making-Test in Virtual Reality (TMT-VR): The Effects of Interaction Modes and Gaming Skills on Cognitive Performance of Young Adults. Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-