Submitted:

17 September 2024

Posted:

17 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Hip Protector Trial

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Findings

| Group A (n = 8) | Group B (n = 7) | p | |

| Age, mean (± SD) | 81.4 (± 10.9) | 77.0 (± 9.1) | 0.256 |

| Gender (Male), n (%) | 8 (100%) | 7 (100%) | 1.000 |

| Ethnicity (Chinese), n (%) | 8 (100%) | 5 (71.4%) | 0.398 |

| Ethnicity (Malay), n (%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (28.6%) | 0.571 |

| Have ≥2 chronic health conditions, n (%) | 8 (100%) | 7 (100%) | 1.000 |

| AMT, mean (± SD) | 3.9 (± 3.0) | 8.6 (± 2.0) | .0001 |

| TUG, mean (± SD) | 26.0s (± 16.2s) | 14.9s (± 21.3s) | 0.341 |

| MBI, mean (± SD) | 80.9 (± 19.2) | 72.7 (± 15.3) | 0.383 |

| History of falls in the past 6 months, n (%) | 3 (37.55%) | 0 (0%) | 0.040 |

| Independent walking, n (%) | 7 (87.5%) | 3 (42.9%) | 0.264 |

| Wheelchair-bound, n (%) | 1 (12.5%) | 4 (57.1%) | 0.398 |

3.1.1. Wear Time Trends

3.2. Qualitative Findings

3.2.1. Learnability

- Facilitators Affecting Users’ Learnability.

- Barriers Affecting Users’ Learnability.

3.2.2. Efficiency

- Facilitators Affecting Efficiency of the Use of Hip Protector.

- Barriers Affecting the Efficiency of the Use of Hip Protector.

3.2.3. Satisfaction

- Facilitators Affecting Care Staff’s Satisfaction.

- Barriers Affecting Care Staff’s Satisfaction.

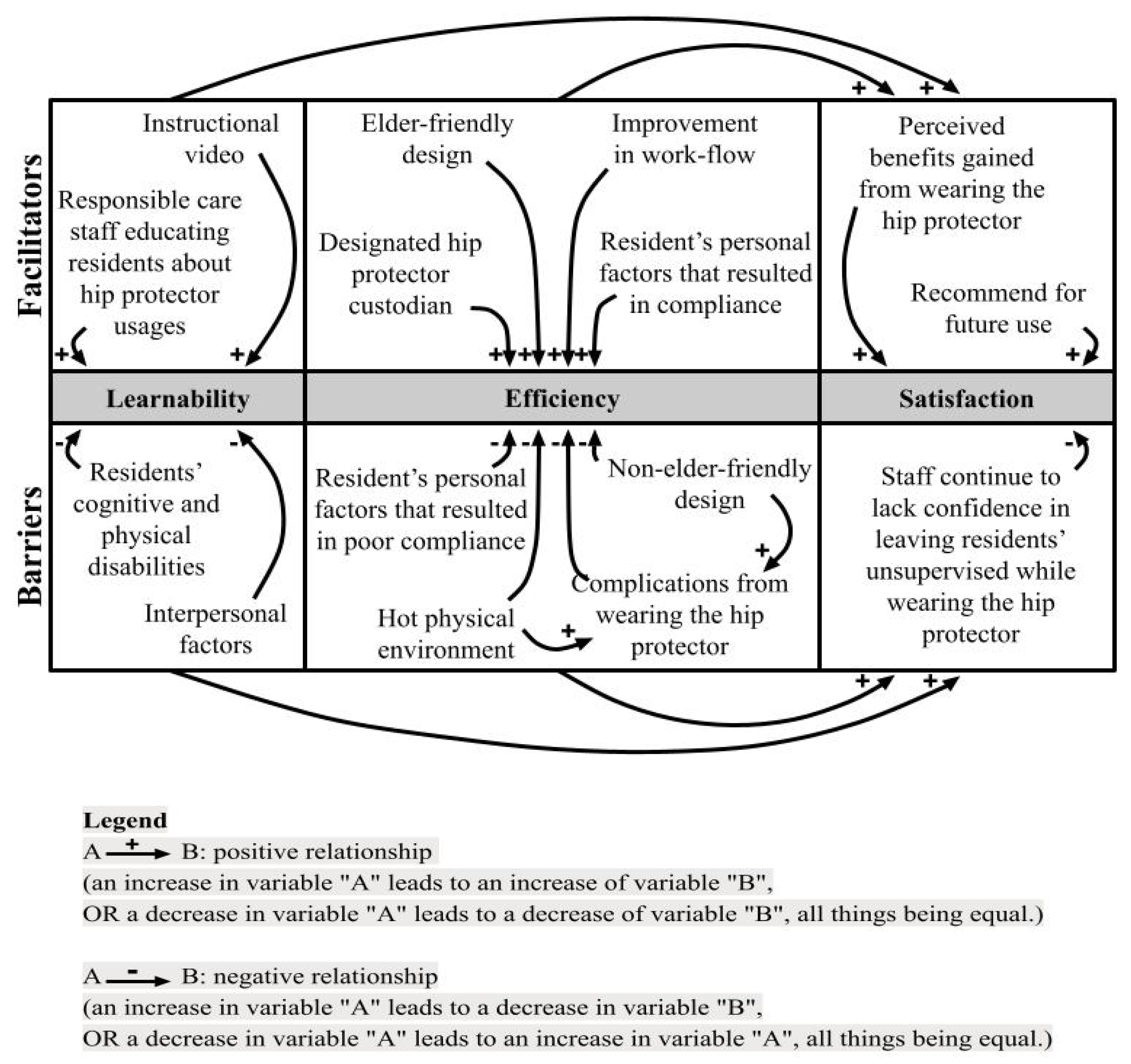

3.2.4. Relationship Between Themes

3.2.5. Relationship Between Quantitative and Qualitative Data

3. Discussion

3.1. Learnability

3.2. Efficiency

3.2. Satisfaction

3.2. Limitations of the study

3.2. Implications for Practice and Future Recommendations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ang, Y.H.; Au, S.Y.; Yap, L.K.; Ee, C.H. Functional decline of the elderly in a nursing home. Singapore Medical Journal 2006, 47, 219–24. Available online: http://www.smj.org.sg/sites/default/files/4703/4703a6.pdf. [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron ID Murray, G.R.; Gillespie, L.D.; Robertson, M.C.; Hill, K.D.; Cumming, R.G.; Kerse, N. Interventions for preventing falls in older people in nursing care facilities and hospitals. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, 1, CD005465–CD005465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen. STM32-based Anti-fall Smart Vest System for the Elderly. 2017 IEEE 3rd Information Technology and Mechatronics Engineering Conference (ITOEC) IEEE; 2022; 6. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Fetters, M.D.; Ivankova, N.V. Designing a mixed methods study in primary care. Annals of Family Medicine 2004, 2, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerdoux, E.; Dressaire, D.; Martin, S.; Adam, S.; Brouillet, D. Habit and Recollection in Healthy Aging, Mild Cognitive Impairment, and Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuropsychology 2012, 26, 517–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Promotion Board. Falls Prevention Among Older Adults Living in The Community. Health Promotion Board. 2015. Available online: https://www.hpb.gov.sg/docs/default-source/pdf/cpg_falls_preventionb274.pdf.

- Hewitt, J.; Goodall, S.; Clemson, L.; Henwood, T.; Refshauge, K. Progressive resistance and balance training for falls prevention in long-term residential aged care: a cluster randomized trial of the Sunbeam Program. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2018, 19, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornboek, K. Current practice in measuring usability: Challenges to usability studies and research. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 2006, 64, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubacher, M.; Wettstein, A. Acceptance of hip protectors for hip fracture prevention in nursing homes. Osteoporosis International 2001, 12, 794–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korall, A.M.; Feldman, F.; Scott, V.J.; Wasdell, M.; Gillan, R.; Ross, D.; Thompson-Franson, T.; Leung, P.; Lin, L. Facilitators of and barriers to hip protector acceptance and adherence in long-term care facilities: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2015, 16, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lally, P.; van Jaarsveld, C.H.M.; Potts, H.W.W.; Wardle, J. How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. In European Journal of Social Psychology 2010, 40, 998–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, W.E.; Nedorost, S.T. Fabric preferences of atopic dermatitis patients. Dermatitis 2009, 20, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J. R. Usability: Lessons Learned... and Yet to Be Learned. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction 2014, 30, 663–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, G.; Warnke, A.; Bender, R.; Mühlhauser, I. Effect on hip fractures of increased use of hip protectors in nursing homes: Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2003, 326, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero-Odasso, M.; Van Der Velde, N.; Martin, F.C.; Petrovic, M.; Tan, M.P.; Ryg, J. ... & Masud, T. World guidelines for falls prevention and management for older adults: a global initiative. Age and Ageing 2022, 51, afac205. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.L. The Focus Group Guidebook. Sage Publications: California, USA, 1998; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.; Fellows, C.; Guevara, H. Emergent methods to focus group research; Handbook for Emergent Methods; Hesse-Biber, S.N., Leavy, P., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, USA, 2008; pp. 189–206. [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth, B.; van der Kaaij, M.; Nelissen, R.; van Wijnen, J.-K.; Drost, K.; Blauw, G.J. Prevention of hip fractures in older adults residing in long-term care facilities with a hip airbag: A retrospective pilot study. BMC Geriatrics 2022, 22, 1–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Halloran, P.D.; WCran, G.; RO Beringer, T.; Kernohan, G.; Orr, J.; Dunlop, L.; JMurray, L. Factors affecting adherence to use of hip protectors amongst residents of nursing homes—A correlation study. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2007, 44, 672–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.J.; Gillespie, W.J.; Gillespie, L.D. Effectiveness of hip protectors for preventing hip fractures in elderly people: Systematic review. BMJ 2006, 332, 571–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepera, G.; Krinta, K.; Mpea, C.; Antoniou, V.; Peristeropoulos, A.; Dimitriadis, Z. Randomized controlled trial of group exercise intervention for fall risk factors reduction in nursing home residents. Canadian Journal on Aging 2023, 42, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Post, E.; Komisar, V.; Sims-Gould, J.; Korall, A.; Feldman, F.; Robinovitch, S. Development of a stick-on hip protector: A multiple methods study to improve hip protector design for older adults in the acute care environment. Journal of Rehabilitation and Assistive Technologies Engineering 2019, 6, 2055668319877314–2055668319877314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, C.S.; Lin, T.S.; Wu, S.C.; Yang JC, S.; Hsu, S.Y.; Cho, T.Y.; Hsieh, C.H. Geriatric hospitalizations in fall-related injuries. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine 2014, 22, 63–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Guo, A.; Xu, Z.; Wang, T.; Wu, R.; Yang, W. Age-related functional brain connectivity during audio–visual hand-held tool recognition. Brain and Behavior 2020, 10, e01759-n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romli, M.H.; Tan, M.P.; Mackenzie, L.; Lovarini, M.; Suttanon, P.; Clemson, L. Falls amongst older people in Southeast Asia: A scoping review. Public Health 2017, 145, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubenstein, L.Z.; Josephson, K.R. The epidemiology of falls and syncope. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 2002, 18, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawka, A.M.; Boulos, P.; Beattie, K.; Thabane, L.; Papaioannou, A.; Gafni, A. ,... & Adachi, J. D. Do hip protectors decrease the risk of hip fracture in institutional and community-dwelling elderly? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Osteoporosis International 2005, 16, 1461–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santesso, N.; Carrasco-Labra, A.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Santesso, N. Hip protectors for preventing hip fractures in older people. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, 2014, CD001255–CD001255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singapore Institute of Technology (SIT). Bespoke hip protector enhances safety of fall-prone seniors. SIT’s Digital Newsroom. 2022. Available online: https://www.singaporetech.edu.sg/news/bespoke-hip-protector-enhances-safety-fall-prone-seniors.

- Son, G.-R.; Therrien, B.; Whall, A. Implicit Memory and Familiarity Among Elders with Dementia. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 2002, 34, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.A.; Ryan, G.; Kresnow, M. Fatalities and Injuries from Falls Among Older Adults — United States, 1993–2003 and 2001–2005. MMWR: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2006, 55, 1221–1224. [Google Scholar]

- Takatou, K.; Shinomiya, N. Cloud-based fall Detection System with Passive RFID Sensor Tags and Supervised Learning. 2021 IEEE 10th Global Conference on Consumer Electronics (GCCE) 2021, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrovolas, S.; Koyanagi, A.; Lara, E.; Ivan Santini, Z.; Haro, J.M. Mild cognitive impairment is associated with falls among older adults: Findings from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). Experimental Gerontology 2016, 75, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Schoor, N.M.; Deville, W.L.; Bouter, L.M.; Lips PT, A.M.; Lips, P. Acceptance and compliance with external hip protectors: A systematic review of the literature. Osteoporosis International 2002, 13, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization [WHO]. WHO global report on falls prevention in older age. 2008. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO%20global%20report%20on%20falls%20prevention%20in%20older%20age.

- Yap, P.; Au, S.; Ang, Y.H.; Kwan, K.Y.; Ng, S.C.; Ee, C. Who are the residents of a Nursing Home in Singapore? Singapore Medical Journal 2003, 44, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yong, E.L.; Ganesan, G.; Kramer, M.S.; Logan, S.; Lau, T.C.; Cauley, J.A.; Tan, K.B. Hip fractures in Singapore: ethnic differences and temporal trends in the new millennium. Osteoporosis International 2019, 30, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).