1. Introduction

Canada is currently experiencing significant demographic shifts driven by both negative and positive forces. On the negative side, the country faces a sharp decline in birth rates now down to 1.33 children per woman in 2022 [

1,

2]. This falls well below the population replenishment rate [

2], which is a trend observed in many other industrialized nations [

3]. This demographic decline poses long-term risks, including potential labor shortages and increased economic strain on social support systems [

4]. Conversely, Canada has seen a substantial surge in immigration, which has counterbalanced the adverse effects of the declining birth rate on the total population [

5]. This influx has introduced its own challenges, however, such as overcrowded schools [

6], strained healthcare facilities, and escalating issues related to affordable housing and homelessness [

7]. Despite these stressors, the unprecedented increased immigration rate has offset the negative trends, leading to a steep rise in the overall growth rate of the population [

8]. All of these trends contributing to a rapid growth rate have notably reduced Canada’s quality of life (having dropped in global rankings from 5th to 30th) [

9,

10]. The Century Initiative, a non-profit with many members in leadership positions in the federal government, wants to continue the rise in population and has set a goal for Canada of achieving a population of 100 million by 2100 [

11].

Another recent development significantly affecting Canada's population dynamics is the legalization and normalization of euthanasia through the Canadian Government’s program of medical assistance in dying (MAiD) [

12]. This policy shift has led to a notable increase in the national death rate, with MAiD now ranking as the fifth leading cause of death in the country [

13,

14]. Initially, MAiD was primarily utilized for terminally ill patients experiencing intolerable suffering [

15], but ongoing proposals suggest expanding eligibility to individuals with severe mental health challenges [

16]. For example, Bill C-14 - states: “It should be noted that people with a

mental illness or physical disability would not be excluded from the regime but would only be able to access medical assistance in dying if they met all of the eligibility criteria.” (emphasis added) [

16].

If these proposals are enacted, the potential impact on Canada’s population could be profound. A knowledge gap exists to determine to what degree the expansion of MAiD to include mental health conditions may exacerbate the existing challenges associated with an aging population and declining birth rates. In addition, the literature is not clear if this may potentially reduce the overall population and complicate efforts to meet national population targets set by the Century Initiative. Lastly, the degree to Canada’s reliance on immigration is needed to achieve demographic goals has yet to be quantified.

To fill these knowledge gaps, this study conducts a comprehensive evaluation of the prevalence of mental illness in Canada. It includes a sensitivity analysis to assess variations in mental illness rates across different age groups and types of mental health conditions and their effects on the Canadian population if MAiD is expanded to mental health. By examining these factors and the results, the analysis estimates the extent mental health issues can have on MAiD and determines how many additional immigrants might be needed to address this shortfall to reach population goals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Defining Mental Illness/Mental Health Disorders

Mental health disorders or mental illnesses are marked by changes in cognition, emotions, or behavior that lead to considerable distress and disruptions in daily functioning [

17]. Mental illness involves a prolonged decline in an individual's ability to function effectively, often resulting from high levels of distress, alterations in thinking, mood, or behavior, experiences of isolation, loneliness, and sadness, and a sense of disconnection from others and activities [

18]. Some examples include major depression, bipolar disorder, and eating disorders [

17]. Mental illness, however, differs from the temporary distress experienced because of typical reactions to challenging situations, such as job loss, romantic break up, or the death of a loved one [

18].

2.2. Reviewing Mental Illness/Mental Health Disorders in Canada

In 2019, approximately one billion individuals (or about 12% of the total global population [

19]), including 14% of adolescents globally, were affected by mental disorders [

20]. Globally, mental disorders are the primary contributor to disability, accounting for one-sixth of all years lived with disability [

20]. In Canada, more than 6.7 million people suffer from mental disorders [

21], which is a higher rate than globally (6.7m/41.7m [

22]) at 16% of Canadians. By the age of 40, half of Canadians will have experienced a mental illness [

21]. Mental disorders are a major cause of disability in the country, with nearly 500,000 employed Canadians missing work each week due to these conditions [

21]. 2011 estimates suggest the prevalence of mental illness is projected to rise by 31% over the next three decades, surpassing 8.9 million cases [

23]. This estimate included approximately 1.2 million children and adolescents aged 9 to 19 [

23]. About 20% of young people in Canada experience a mental illness or disorder [

24]. Individuals aged 15 to 24, especially women, are more susceptible to mental illness, mood or anxiety and substance use disorders compared to other age groups [

25,

26]. In Ontario, 39% of high school students report experiencing a moderate-to-severe level of psychological distress, characterized by symptoms of anxiety and depression, while an additional 17% experience a severe level of psychological distress [

27]. During the year 2016-17, of the Canadians using health services for mental illness, 57% were female while 43% were male [

28]. Furthermore, the cost of disability leave related to mental illness is approximately twice as high as that associated with physical illnesses [

21]. As of 2011, the economic impact of mental illness in Canada was estimated at approximately

$50 billion [

23]. The projections indicated that the total cumulative cost over the next 30 years will exceed

$2.5 trillion [

23].

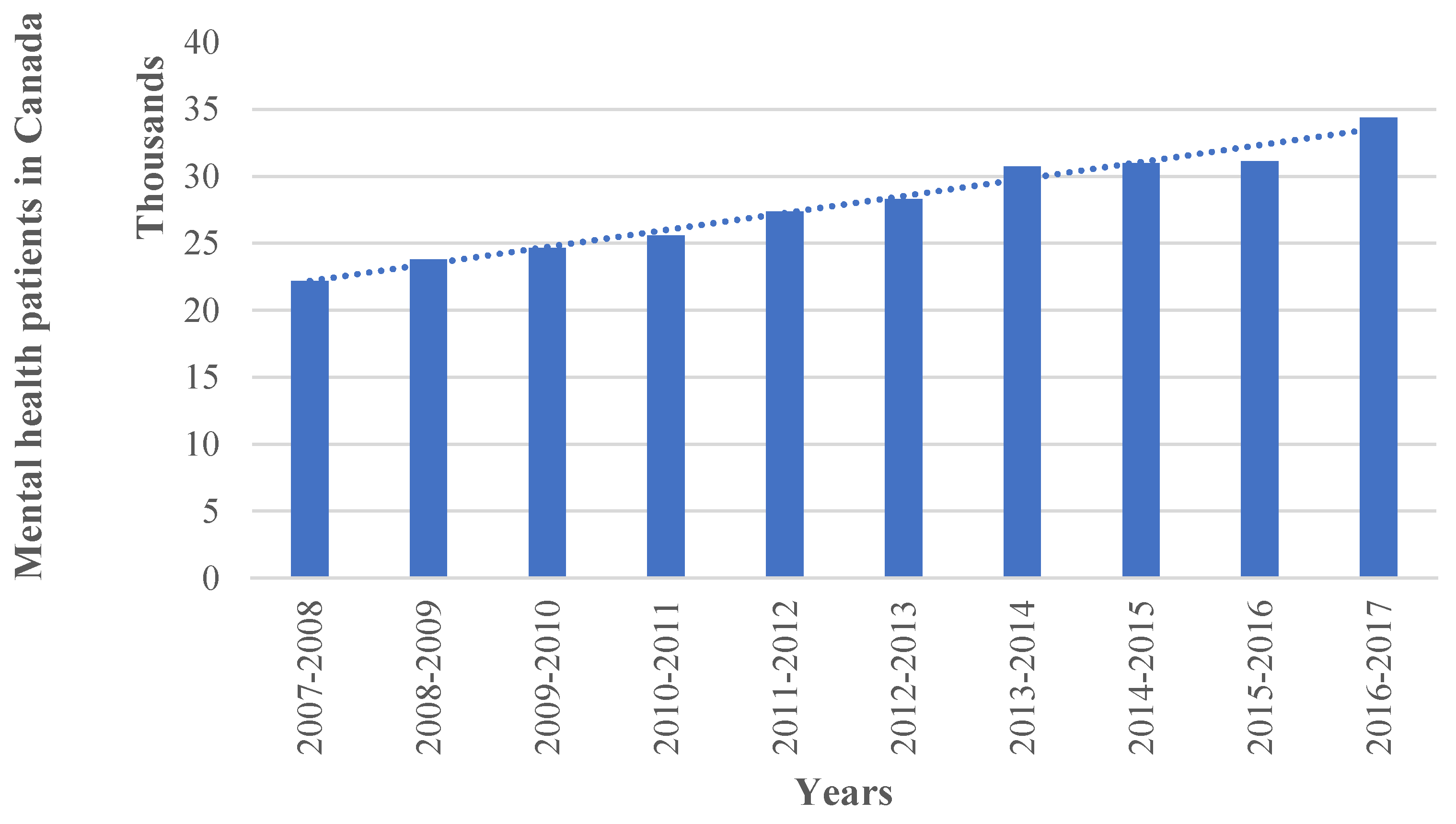

Between 2007 and 2017, the number of new mental health patients saw a notable increase, growing from 22,182 in 2007-2008 to 34,380 in 2016-2017 [

21]. This rise represents an overall increase of 55% over the decade. Each year, the number of patients generally increased, though the rate of growth varied. The most substantial annual growth occurred between 2015 and 2016, with a 10.5% rise. As can be seen in

Figure 1, the data highlights a clear upward trend in mental health needs over the period with a year-on-year increase of 1,268 patients in Canada and can be expressed as:

Where N

Mentalrepresents the number of mental illness patients identified in Canada, and y

2008 denotes the number of years, with year 1 being counted from 2008.

2.3. Assessing Medically Assistance in Dying (MAiD) in Canada

Currently, in Canada individuals seeking MAiD must make the request voluntarily. Applicants must be at least 18 years old and have the capacity to make informed healthcare decisions [

29]. They should have provided informed consent and be eligible for publicly funded health care services within the country [

29]. The individual must be diagnosed with a “grievous and irremediable medical condition” involving a serious and incurable illness, disease, or disability, accompanied by an advanced and irreversible decline in the individual's capabilities [

29]. Furthermore, the person must be enduring physical or psychological suffering that is intolerable to them and that cannot be relieved under conditions that they consider acceptable [

29]. Advocates of expanding MAiD to mental illness argue that mental illness is just as valid as physical illness and suffering [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. For example, Stoll et al. concluded: “However, the possibility that some individuals with severe and persistent mental illness (SPMI) may perceive burdensomeness does not mean that they should be routinely excluded from MAiD. For SPMI patients with intact decision-making capacity who feel their life is not worth living, perceived burdensomeness as a component of this intolerable suffering is not a sufficient reason to deny access to MAiD.” [

34]. In February, 2024, legislation was enacted to prolong the temporary exclusion of eligibility for MAiD for individuals suffering exclusively from a mental illness until March, 2027 [

15].

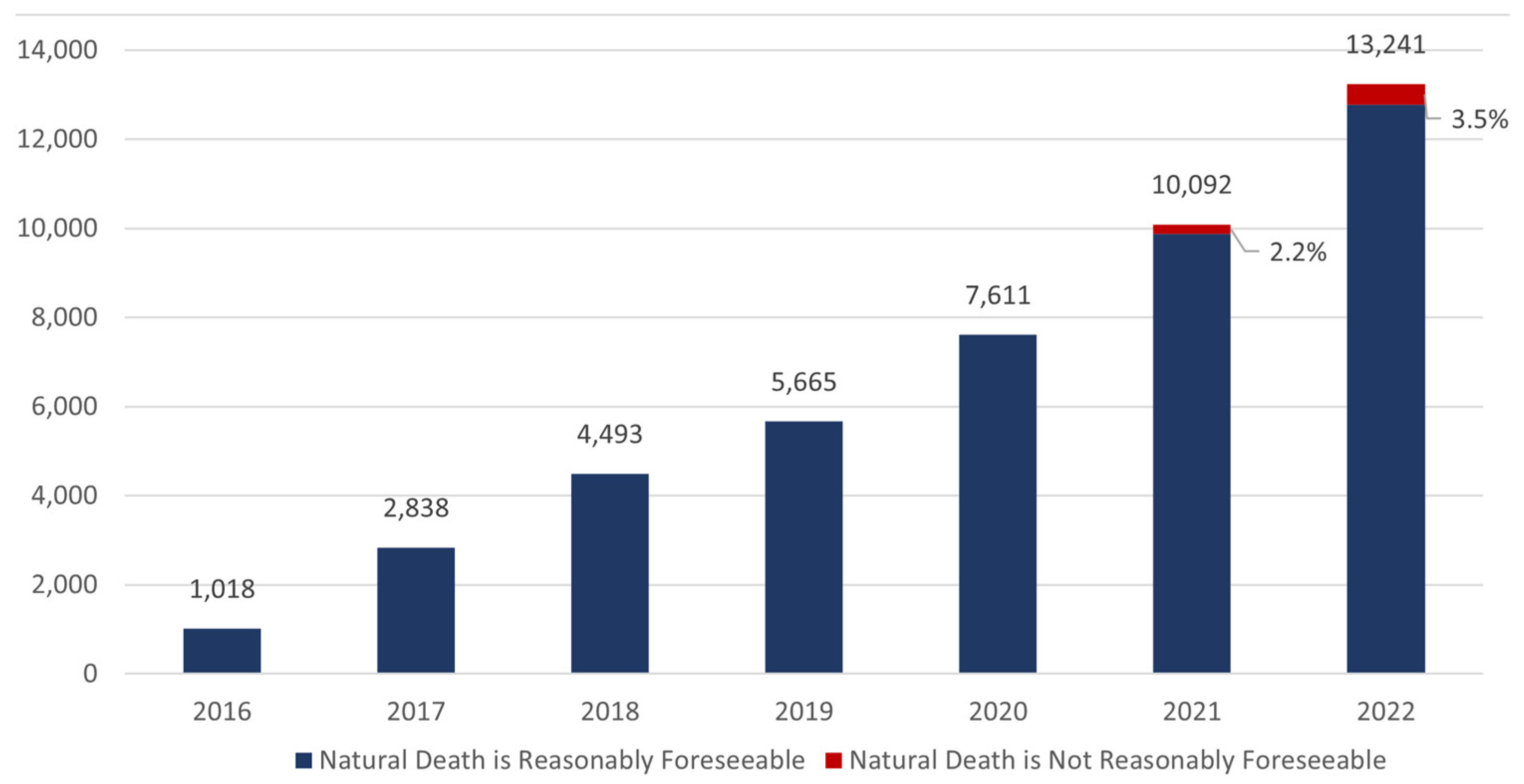

As of 2022, Canada has had six and a half years of providing access to MAiD. During that year, there were 13,241 instances of MAiD accounting for 4.1% of all deaths in Canada, bringing the cumulative total of medically assisted deaths in Canada since the program's inception in 2016 to 44,958 [

29]. The number of MAiD provisions in 2022 represented a 31.2% increase compared to 2021, which was slightly lower than the 32.6% increase observed between 2020 and 2021 [

29]. Over the past six years, the annual growth rate of MAiD provisions has remained consistently high, averaging 31.1% from 2019 to 2022 [

29] as shown in

Figure 2. In addition, there is a growing trend of MAiD being used for patients that are unlikely to die a natural death in the near future (red in

Figure 2).

In 2022, a marginally higher percentage of males (51.4%) compared to females (48.6%) received MAiD. The average age of individuals receiving MAiD in 2022 was 77.0 years. Notably, the average age for females in 2022 was 77.9 years, while for males it was 76.1 years.

Canada's MAiD program is the fastest-growing assisted-dying initiative globally [

36]. Health Canada significantly underestimated the pace at which MAiD would reach what is considered a "steady state" and how swiftly the program would hit the 4% threshold of total deaths [

37]. This threshold was achieved in 2022, eleven years earlier than Health Canada's forecast [

36]. Contrary to treating MAiD as a last resort, assessors and providers approach it with a proactive stance [

36]. The rate of denied MAiD requests has decreased significantly, currently standing at 3.5% [

29,

36]. Bureaucratic inefficiencies in the Canadian health care system that plague other services and routinely result in waiting times measured in weeks [

38] have been overcome for this service and it is now possible for MAiD requests to be assessed and fulfilled within a single day [

36]. It is interesting to note that the wait times for other Canadian medical services even result in the death of patients. For example, over 17,000 patients died while waiting for surgery or diagnostic scans in 2022-2023 [

39]. Thus currently, more patients die while waiting for Canadian medical services than those who request death from the Canadian medical services. It is highly, likely this will not be the case in the future if the current trends continue.

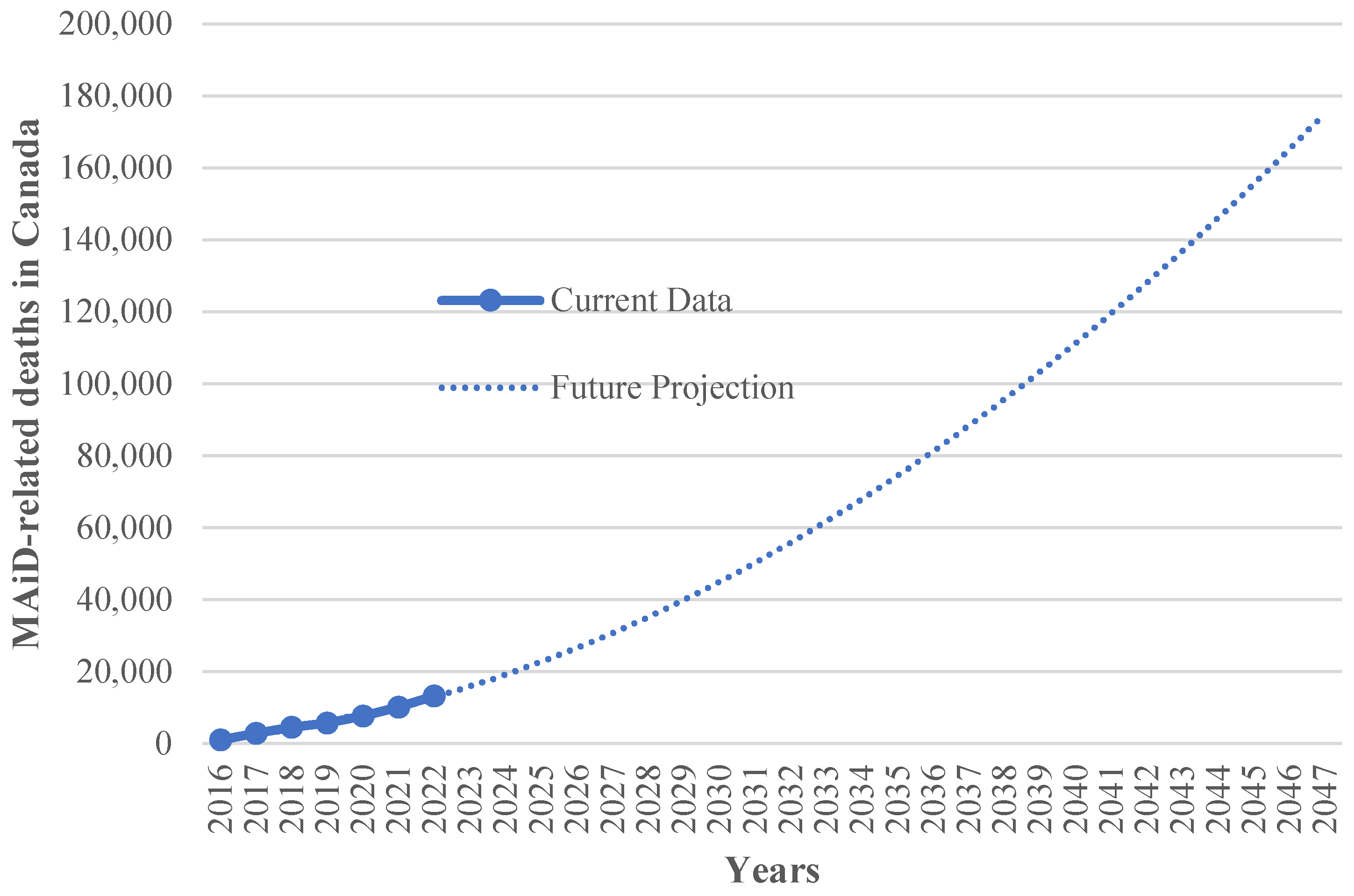

The historical growth of MAiD as well as the projections into the future are shown in

Figure 3. The equations derived from

Figure 3 provide future projections of MAiD-related deaths, M, based on current rates. The equation is developed by analyzing the patterns in the existing data, projecting it in the future and then using a trendline that best fits the data.

where t

2016 denotes the number of years since the initiation of MAiD access in Canada, with year 1 starting in 2016. The quadratic term allows the model to account for accelerating growth trends in MAiD cases, which a linear model would not capture effectively. This polynomial function provides a highly accurate fit to the historical data [

29], as indicated by the high R2 value of 0.9941, demonstrating its capability to predict future MAiD cases with precision. It should be noted that these MAiD cases involve patients with physical illnesses rather than those suffering from mental health issues.

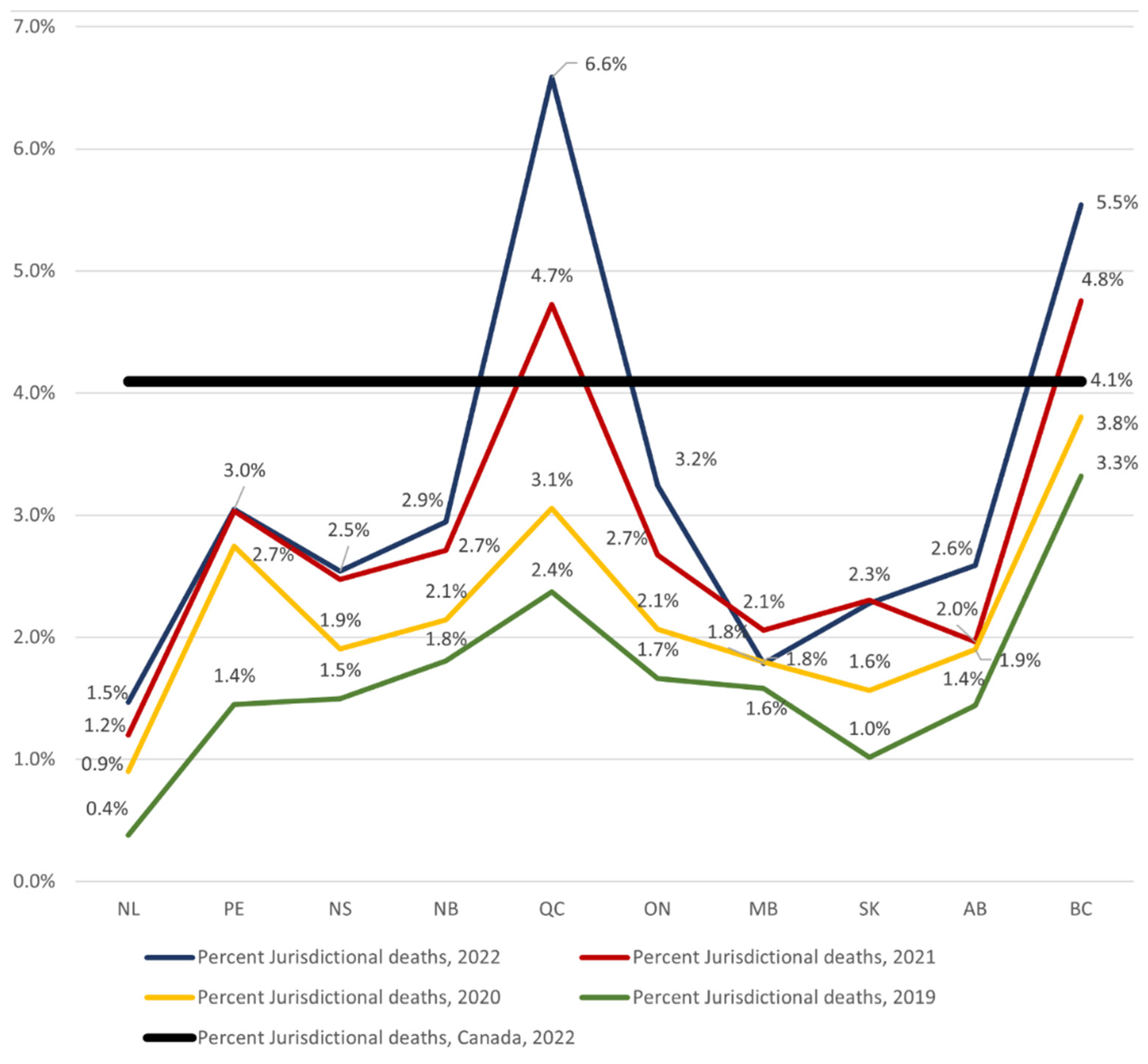

The distribution of MAiD across Canadian provinces is shown in

Figure 4. As can be seen by

Figure 4, Quebec (QC) and Ontario (ON) experienced substantial growth, with Quebec rising from 494 cases in 2016 to 4,801 in 2022, and Ontario from 191 cases to 3,934. Over the entire period, Quebec had the highest total of MAiD cases at 14,578, followed by Ontario at 13,732, and British Columbia at 9,219.

In 2022, the distribution of MAiD across various medical conditions in Canada revealed that cancer was the predominant condition, accounting for 63.0% of MAiD cases [

40]. Cardiovascular conditions were the second most common, representing 18.8% of cases, respiratory conditions made up 13.2%, neurological disorders were 12.6% of MAiD cases, and multiple comorbidities were present in 10.1% of cases [

40]. Organ failure contributed to 8.2% of MAiD instances and other conditions collectively accounted for 14.9% of the cases, reflecting a diverse range of underlying health issues among those who opted for MAiD [

40].

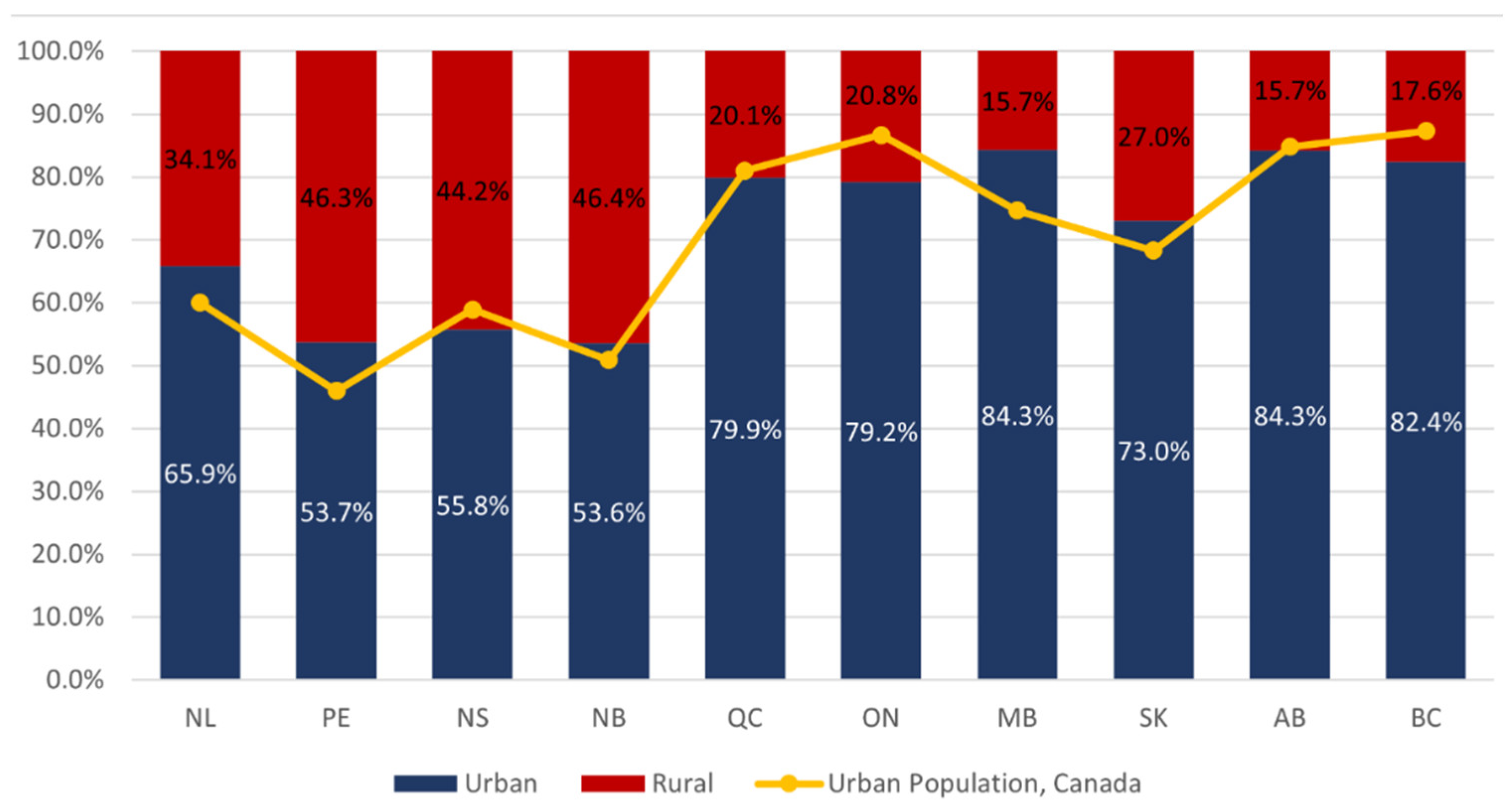

Figure 5 demonstrates the percentage of urban and rural population opting for MAiD in Canada. It is clear that MAiD is primarily an urban issue in every province.

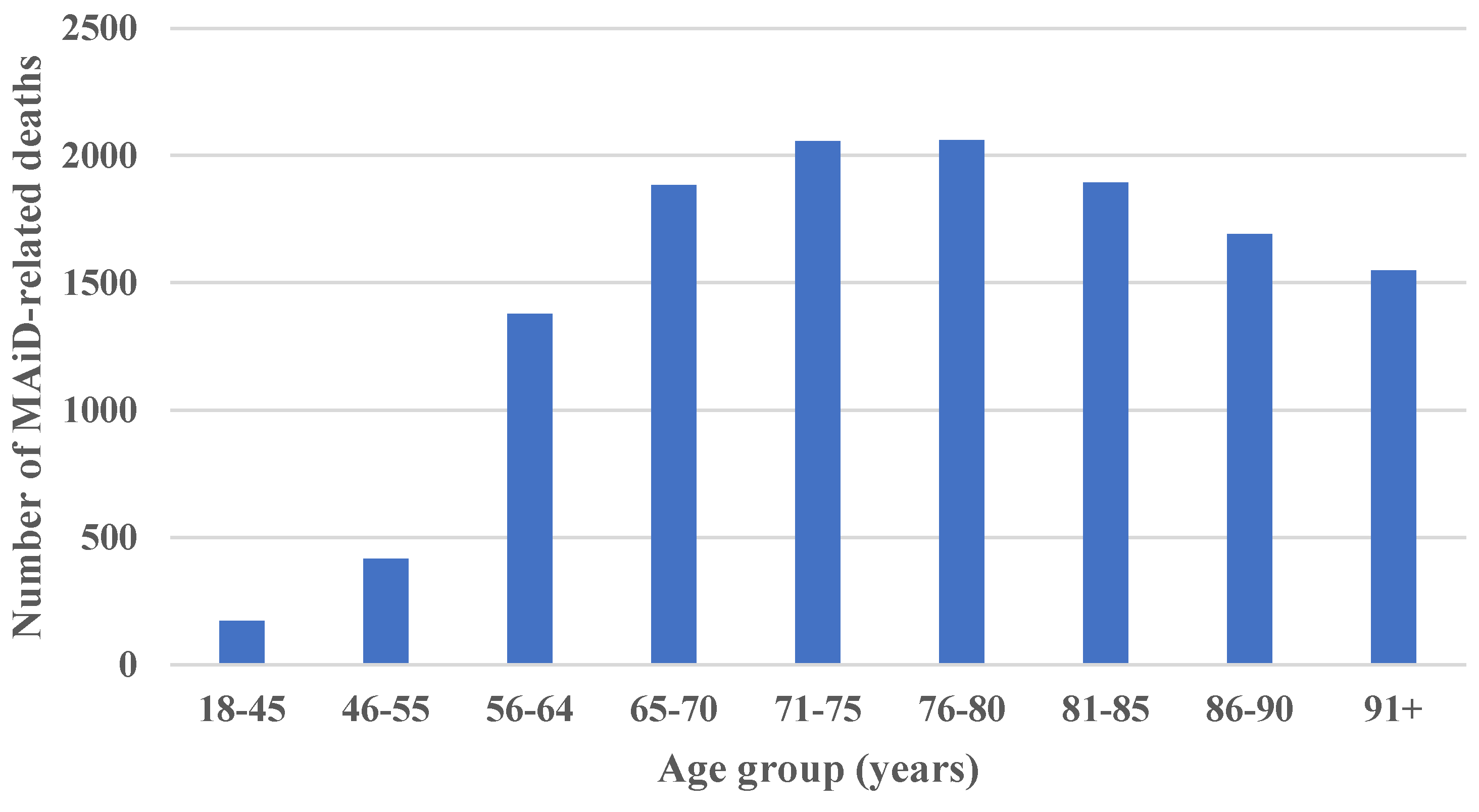

The distribution of MAiD deaths across different age groups in Canada is shown in

Figure 6 [

29]. This age-related trend highlights a growing prevalence of MAiD in older age groups, with the highest incidence observed in the late sixties, seventies and early eighties. It should be noted that if MAiD is expanded to mental illness the age-related trend would be expected to shift aggressively to the left to younger age groups more evenly distributed with the current total Canadian population.

2.4. Population Growth Trends and the Role of MAiD

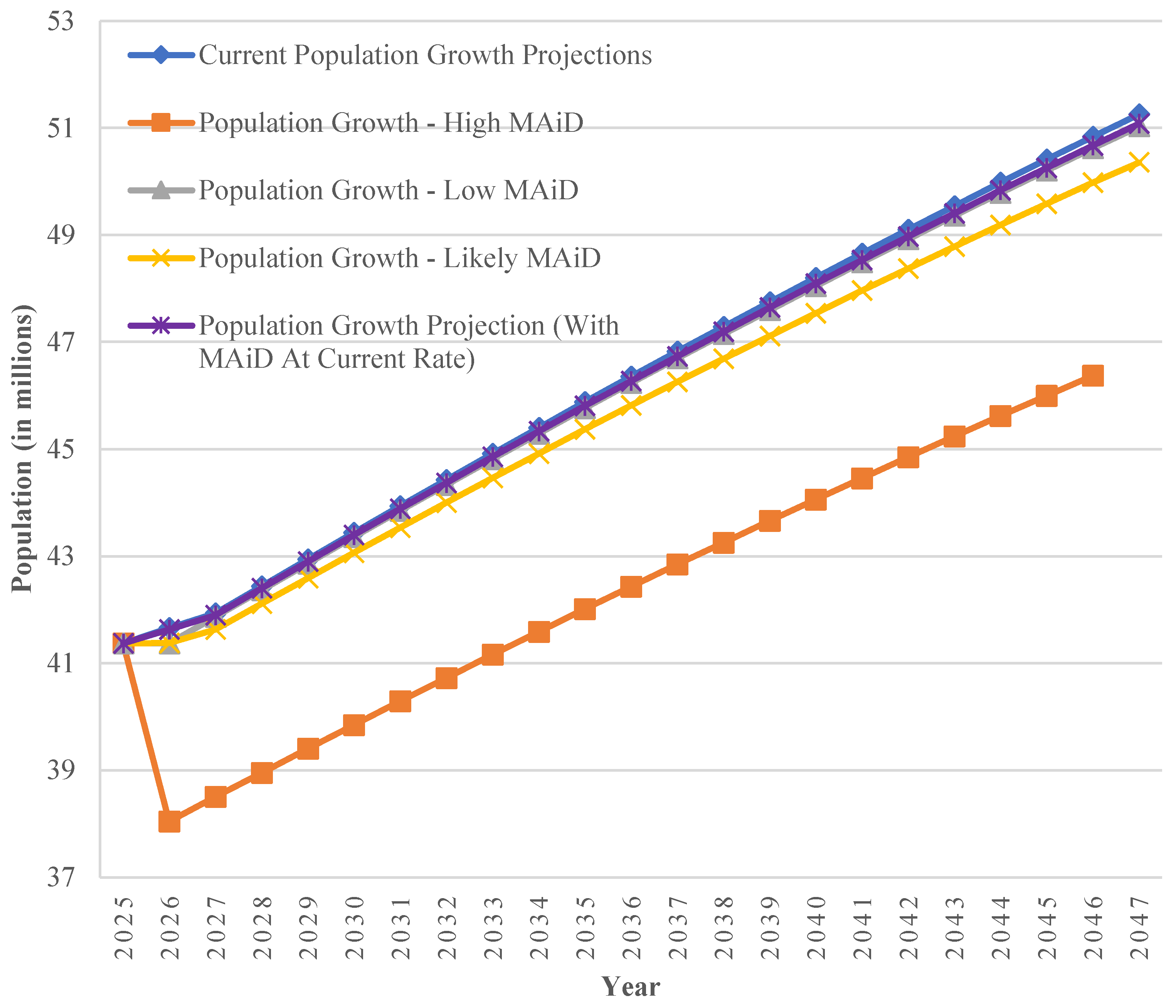

Population growth projections in Canada indicate a gradual increase over time, but the presence of MAiD has a noticeable impact on these projections. Without accounting for MAiD, the population is expected to grow from 40,097,800 to 51,257,400 by the end of the projection period i.e., year 2047, with an average growth rate of approximately 0.83% recorded for the same year [

41]. The population, P, of Canada can be calculated using the following equation derived by studying the data patterns and then fitting a trendline that most accurately represents these patterns.:

where t2023 denotes the number of years with year 1 starting in 2023.

The impact of MAiD based on the projection as per current rates (

Figure 3) is then factored into the population projections to generate updated figures and assess its effect on population growth in Canada. The equation governing the population growth rate in Canada after incorporation of MAiD provides the total people in Canada, P

MAiD, is given by:

where t2023 denotes the number of years since the beginning, with the first year being 2023. Ideally, subtracting equation 2 from equation 3 should yield the same result as equation 4. The revised population projections, however, incorporating MAiD are derived from Canadian government population goal ‘P’ (rather than those predicted by equation 3) and subtracting the projections from equation 2. Consequently, the revised population figures that include MAiD are then ascertained, and the equation is developed by examining the data patterns and then applying a trendline that best matches these patterns to come up with equation 4.

2.5. Mental Disorders and MAiD Practices – Low, High and Likely Scenarios

To evaluate the impact of MAiD in Canada, three distinct scenarios were developed: low, likely and high. The low scenario is based on a conservative approach, considering the proportion of individuals newly diagnosed with the aforementioned mental health conditions (

Figure 1) and equation 1 who are subject to MAiD. The likely scenario integrates a middle-ground approach, encompassing both individuals with drug dependencies, and all attempted suicides. The high scenario assumes full eligibility for MAiD for individuals with mental health conditions such as major depressive episodes, bipolar disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, alcohol use disorder, cannabis use disorder, and other substance use disorders, without any restrictions. These scenarios were constructed to provide a range of projections, capturing the potential variability in MAiD cases based on different eligibility criteria and treatment considerations. This methodology allows for a comprehensive analysis of how varying levels of eligibility and treatment impacts could influence the overall MAiD statistics in Canada.

Total population in Canada is currently 39,818,445 people [

42]. In any given year, 1 in 5 Canadians experiences a mental illness [

23]. By the time Canadians reach 40 years of age, 1 in 2 have – or have had – a mental illness [

23]. In 2022, over 5 million people in Canada were diagnosed with a mood, anxiety, or substance use disorder [

43]. Given that Canada's total population in 2022 was 39.28 million [

44], this represents approximately 12.7% of the population that would be available to MAiD if it was legally extended to mental disease. In the following equations, P is the total of number of people or population of Canada. P

MAiD,low, P

MAiD,likely and P

MAiD,high are the population projections of Canada in low, likely and high scenarios.

For the low scenario, to make the estimate the number people in Canada after selecting MAiD (

conservative, the projections were adjusted based on the proportion of individuals with mental health issues including major depressive episodes, bipolar disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, alcohol use disorder, cannabis use disorder, and other substance use disorders (72.4% so F

Mental-severe=0.724) [

26], but only applied to the newly identified mentally-ill patients (

Figure 1).

For the likely scenario, data on attempted suicides and the number of people with other drug use disorder (3.6%) was used (F

ODUD=0.036) [

26]. For this scenario, of the 12.7% of the population suffering from mental health issues (F

Pop=0.127), only 3.6% were considered who will opt for MAiD, i.e., individuals suffering from other drug use disorders. In addition, research indicates that approximately 3.1% of Canadians have attempted suicide (S

a=0.031) at some point in their lifetime [

45,

46] while the average life expectancy (E) of an average Canadian is 81.6 years (E=81.6y) [

47]. Dividing S

a by E provides the suicide attempts per year. The following formula is then used to adjust the estimates for Canadians dying from MAiD,

, resulting in the following likely estimates:

For the high scenario, of the 12.7% (F

pop) of the total population that experience mental disorders from the total Canadian population, the prevalence of various mental health conditions such as major depressive episodes, bipolar disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, alcohol use disorder, cannabis use disorder, and other substance use disorders was aggregated to estimate the fraction of the population affected (F

Mental-severe=0.724)[

26]. This fraction was then used to revise the population projections assuming that all individuals with these conditions would receive MAiD to determine

.

Using these statistics is plausible because it incorporates relevant data on suicide attempts, and drugs usage which helps account for the context of mental health issues in the population. By applying this factor, the estimates are adjusted to reflect a more cautious view, acknowledging the significant overlap between depression, suicide attempts, and the potential impact of MAiD.

2.6. The Role of Immigrants in Population Growth of Canada:

Recent demographic projections for Canada highlight that immigration will continue to be the primary driver of population growth in the coming years, maintaining a trend that started in the 1990s [

48]. The base-case scenario suggests that the Canadian population will reach approximately 48 million by 2041, with approximately 15 million individuals being immigrant [

49]. This group is expected to make up 31.8% of the total population, a significant increase from the 7.5 million or 21.9% recorded in 2016 [

49]. By 2041, it is projected that 25% of Canadians will have been born in Asia or Africa [

48]. This implies that, given the current immigration rates, about 7.6 million immigrants will be added over the next 25 years. The overall impact of immigration on the population appears to be about 1.17 times greater, possibly due to factors such as the birth of children. Recent years have seen elevated immigration levels, reaching 493,236 in 2021-2022 and 468,817 in 2022-2023 [

50]. In 2022/23, nearly 98% of Canada's population growth was attributable to international migration [

51].

For this analysis immigration levels are set to align with both current population projections and the Century Initiative scenarios, which include high, likely, and low cases as discussed in the article. The following equations are used to determine the additional number of immigrants needed, I, to offset MAiD-related deaths in Canada:

Current Population Projection:

Where P is the population projection by the Canadian Government, P

CENTURY is the population targets for Canada set by the Century Initiative by year 2100. I

CP,low, I

CP,likely, I

CP,high, I

CI,low, I

CI,likely, and I

CI,high are the required additional immigrants required to meet current and Century Initiative population projections under low, likely and high MAiD scenarios.

3. Results

The projections for MAiD in Canada highlight a substantial and escalating impact on the population over the coming decades. The numbers are projected to increase significantly each year, reaching 175,143 by 2047 for non-mental illness related MAiD. This sharp upward trend underscores the growing prevalence and potential societal implications of MAiD. Specifically, the annual figures rise to a potentially alarming 55,836 by 2032, continuing to escalate towards 103,297 by 2039. By 2046, the projected number of MAiD cases reaches 165,135. This growth not only signifies a profound shift in end-of-life care but also poses critical challenges for healthcare resources, ethical considerations, and demographic dynamics in Canada.

When factoring in physical medically-related MAiD at current rates, the projected population growth is slightly reduced, with the population anticipated to reach 51 million, and an average growth rate of about 0.81% as compared to growth rate of 0.83% without MAiD for year 2047. This reflects a marginal decrease in growth rates due to the contribution of physical medically-related MAiD, illustrating how such end-of-life options can subtly influence demographic trends. It should be pointed out, however, these values only consider current trends continuing and thus may be overly conservative underestimates. This is because health care costs are dominated by the last year of life in Canada. For example, the average health care cost in the last year of life was

$53,661 in Ontario [

52]. As MAiD is completely normalized the elderly may experience social pressure to request MAiD to conserve economic resources for their families and society as a whole. This social pressure would be expected to substantially increase MAiD requests, particularly if coupled to reductions in pain medication use in palliative care.

Three scenarios were used to project MAiD occurrences including mental disorder cases in Canada: Low, Likely and High. Each scenario assumes different levels of MAiD adoption, impacting the projected numbers. The projections as a function of time are shown in

Figure 7.

In the low MAiD scenario, the number of MAiD cases is projected to grow from 45,786 to 227,024 in 2047. This highlights a more conservative, but still notable rise in MAiD cases. The likely MAiD scenario provides a middle-ground estimate, with MAiD cases projected to rise from 214,499 to 896,312 cases in 2047. Both the low and likely estimates indicate a substantial rise in MAiD cases in Canada, surpassing the number of deaths from malignant neoplasms, the leading cause of death in the country in 2022, which was 82,412 [

53].

Under the high MAiD scenario, the number of MAiD cases is expected to rise significantly, reaching approximately 4.90 million in 2047. As a percentage of the total current population, this translates to approximately 12.3 %, indicating that nearly 1 in 8 Canadian could potentially be affected by MAiD.

These projections suggest that if MAiD adoption were to follow the high scenario, a substantial portion of the population could be subject to MAiD, raising ethical and societal concerns such as challenges related to national population objectives [

54,

55,

56,

57]. Such a significant proportion could potentially disrupt the demographic balance and healthcare system, particularly if mental health conditions contribute to a higher rate of MAiD. In scenarios where mental illness plays a role, the implications are even more profound. If mental illness were to become a more significant factor in MAiD decisions, it could exacerbate the rate at which individuals seek MAiD, further impacting population growth and raising concerns about the adequacy of mental health support services.

With the rapid rise in MAiD rates, immigration levels will need to be significantly increased.

Table 1 outlines the annual additional immigration requirements necessary to achieve the population targets based on current projections and the Century Initiative, considering the three scenarios examined in this study.

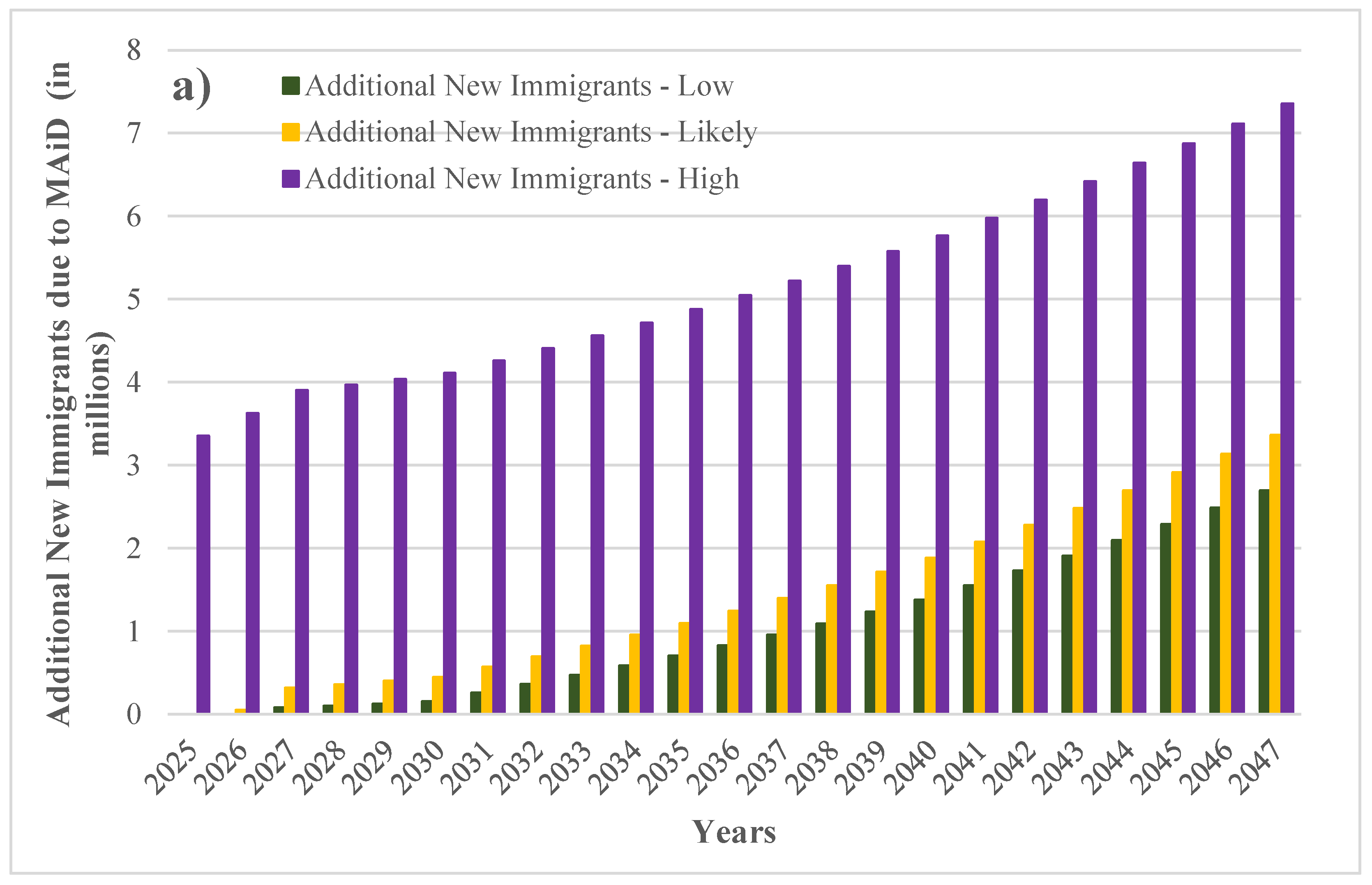

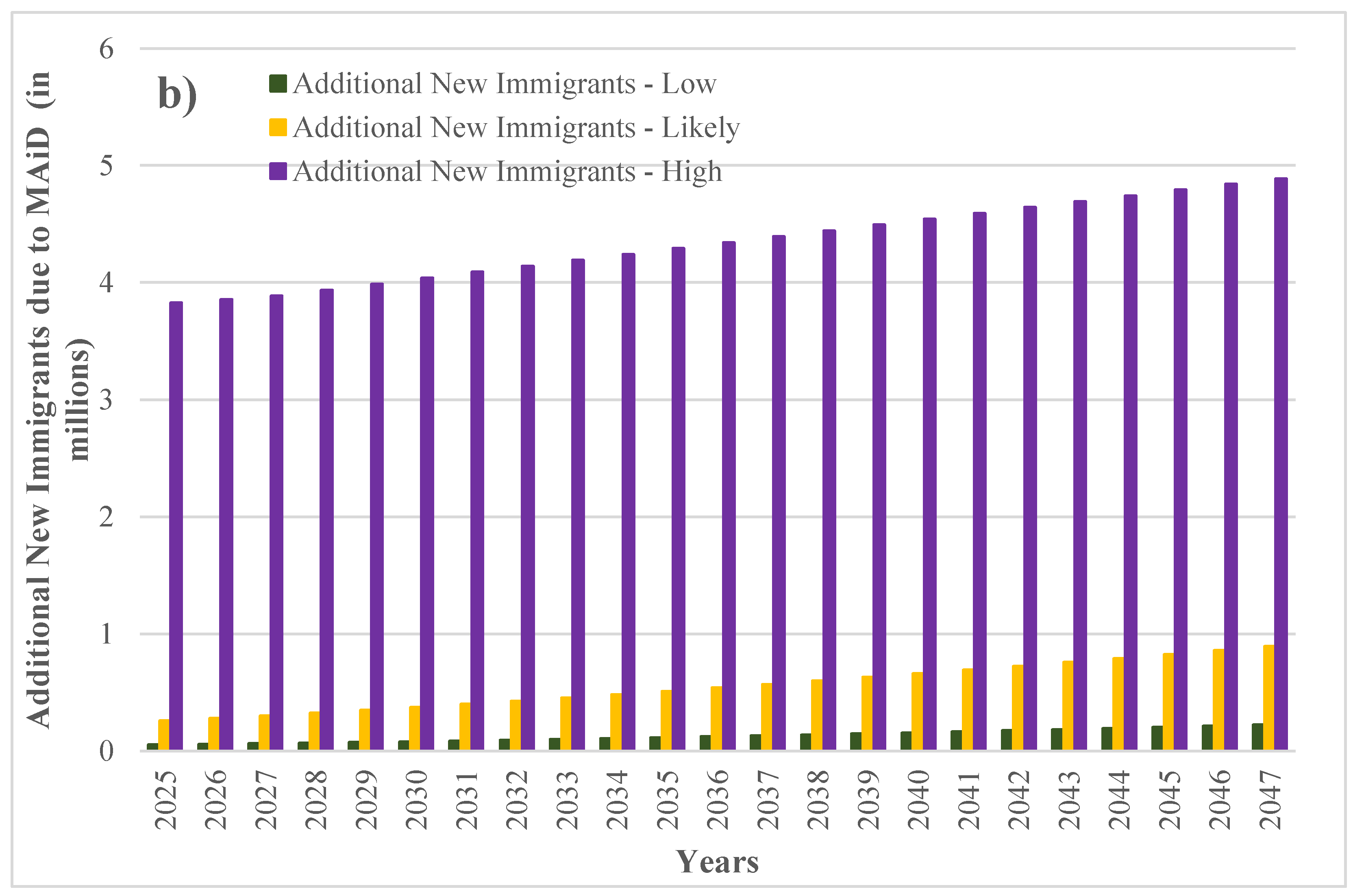

To manage the demographic challenges posed by MAiD and ensure population stability in Canada from 2025 to 2047, immigration levels will need to be adjusted according to varying scenarios. Under the Century Initiative model, the high scenario projects a requirement for new immigrants ranging from approximately 3.4 million in 2025 to about 7.4 million by 2047. In the low scenario, the need starts at around 0.08 million in 2027 and rises to about 2.7 million by 2047, showing a significant but less steep increase. The likely scenario indicates a more moderate need, beginning at roughly 0.2 million in 2027 and reaching 2.9 million by 2047.

Figure 8.

Average additional annual immigrants required to offset MAiD related deaths a) to meet the Century Initiative targets (in millions) for high, likely and low scenarios, and b) to meet the current population projections (in millions) for high, low and likely scenarios.

Figure 8.

Average additional annual immigrants required to offset MAiD related deaths a) to meet the Century Initiative targets (in millions) for high, likely and low scenarios, and b) to meet the current population projections (in millions) for high, low and likely scenarios.

For current population estimates, the high scenario forecasts an immigration requirement starting at about 3.9 million in 2025 and increasing to around 4.9 million by 2047. The low scenario suggests a starting point of approximately 0.05 million in 2025, with a gradual increase to about 0.227 million by 2047. The likely scenario falls in between, with an initial requirement of about 0.25 million in 2025 and a rise to approximately 0.89 million by 2047.

These projections highlight the need for a substantial increase in immigration to offset the demographic effects of MAiD, with varying degrees of necessity depending on the scenarios. The Century Initiative generally requires higher immigration numbers compared to current government population estimates, reflecting a more ambitious approach to managing future population dynamics towards a large population.

4. Discussion

Overall, immigrants tend to arrive in Canada in better health compared to the Canadian-born population, a trend known as the "healthy immigrant effect" (HIE) [

58,

59,

60,

61]. While immigrants generally start with better health, the HIE tends to wane with time, with their health status eventually aligning more closely with that of the host population [

59]. For instance, among recent immigrants, 15% experienced a noticeable decline in health within the first four years of arrival in Canada [

62]. Stress from the acculturation process is one potential cause of this decline [

63]. Research has highlighted three key factors that impact the mental health of immigrants and refugees: acculturation-related stress, economic uncertainty, and ethnic discrimination [

64]. The declining health of newcomers is likely aggravated by the recent rapid population stresses of overcrowded schools, hospitals, and lack of affordable housing that impacts long-time and short-time Canadians alike [

6,

7]. It is likely that the current Canadian society is not entirely what immigrants signed up for, and as a whole, likely to have increased mental health issues of new arrivals [

65]. Thus, the results provided here are likely to be underestimates on the number of MAiD cases as the proportion of immigrants will need to be higher and acculturation creates higher percentage of mental disease.

This study has other limitations as well. Since the study projected the number of MAiD cases in Canada based on historical data, it may not fully account for changes in mental health care and evolving legal frameworks. As societal attitudes, medical practices, and legal regulations regarding MAiD, particularly for individuals with mental health disorders, continue to evolve, these shifts could significantly alter future trends. The study’s reliance on past data may not capture such emerging factors which could impact both the prevalence of MAiD and its effects on population growth. Additionally, the study did not consider regional variations in the application and acceptance of MAiD, which can vary across different provinces and territories as seen in

Figure 4 . The impact of these regional differences on overall trends might not be fully represented. Moreover, the study's projections are constrained by the quality and completeness of historical records, which may include inconsistencies, underreporting, or variations in data collection practices over time. These data limitations can affect the accuracy of the projections and the ability to make precise forecasts about MAiD rates and their impact on population growth.

Future work should focus on incorporating more dynamic variables, including recent changes in legislation and advancements in mental health care, to provide a more comprehensive forecast. Additionally, improving data collection methods and incorporating a range of predictive models could enhance the accuracy of projections and provide a more nuanced understanding of future trends. Research should also examine regional disparities and their effects on MAiD trends.

Future research should also investigate the ethical implications of MAiD, particularly considering concerns about the "slippery slope" effect [

36,

54,

66]. For instance, in the Netherlands, by the 1990s, more than 50% of euthanasia cases were reported as

non-voluntary [

67,

68]. While this is not the case now in Canada, public opinion may change as it can be quite dynamic. For example, public opinion on MAiD has shown notable fluctuations; for example, a live audience in New York City initially supported the legalization of assisted suicide by 65%, with 10% opposed and 25% undecided [

54]. Following a debate, support increased slightly to 67%, while opposition grew to 22% [

54]. Furthermore, unofficial online polling shifted dramatically from 5% opposition before the debate to 51% opposition as of March 21, 2016 [

54]. These shifts in public opinion underscore the importance of considering the broader societal implications of MAiD when evaluating its implementation in Canada. Would public opinion of MAiD differ in Canada under equivalent intellectual or ethical scrutiny? Would the sheer volume of MAiD predicted in this study, if found to be accurate alter the social acceptability within Canada? Similarly, would high MAiD related death rates influence immigration rates? What will the economic implications be if MAiD becomes the dominant cause of death in Canada? These questions provide rich areas of future research.

5. Conclusions

Projections for medical assisted in dying in Canada indicate a significant and escalating impact on the population over the coming decades. The number of MAiD cases is expected to rise sharply, reaching 175,143 by 2047. This trend underscores a profound shift in end-of-life care and presents substantial challenges for healthcare resources, ethics, and demographic dynamics. Incorporating physical-disease related MAiD into population projections shows a slight reduction in population growth. By 2047, the population is anticipated to reach 51 million, with a growth rate of 0.81%, compared to 0.83% without MAiD. This indicates a marginal impact on demographic trends due to MAiD if current physical illness-related MAiD dynamics do not change.

If MAiD is expanded to mental disorders and mental health patients and understanding that more than half of the Canadian population is likely to have faced such illnesses, these numbers could change substantially. For example, under the high MAiD scenario, cases could rise to approximately 4.9 million MAiD deaths per year by 2047. This would impact about 12.3% of the population, signaling a potentially drastic shift in population growth. The low MAiD scenario projects an increase from 45,786 to 227,024 cases reflecting a more conservative, but still significant rise in MAiD related population reductions. The likely scenario offers a middle-ground estimate, with cases growing from 214,499 to approximately 896,312 in 2047. Thus, if MAiD is expanded to mental illness the increasing role of immigration will be vital in maintaining population (and to a greater extent growth) and balancing demographic shifts. To address the loss of lives resulting from the expansion of MAiD in Canada, substantial additional immigration is required, with the high scenario necessitating an average of 4.34 million new immigrants annually. Even under the more moderate likely scenario, the need remains significant of more than half a million additional immigrants per year (or about the population of London ON, Canada’s tenth largest city). When aiming for the Century Initiative targets, the requirement increases further, highlighting the pressing need for robust immigration strategies if MAiD expands. Overall these results emphasize the importance of integrating immigration policies with MAiD policies to ensure demographic stability and achieve long-term population objectives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.P.; methodology, U.J. and J.M.P.; validation U.J. and J.M.P.; formal analysis, U.J. and J.M.P.; investigation, U.J. and J.M.P.; resources, J.M.P.; data curation, U.J. and J.M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, U.J. and J.M.P.; writing—review and editing, U.J. and J.M.P.; visualization, U.J. and J.M.P.; supervision, J.M.P.; project administration, J.M.P.; funding acquisition, J.M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Marchildon, G.P.; Allin, S.; Merkur, S. Health Systems in Transition - Canada Health System Review 2020 2020.

- Izri, T. Canada’s Fertility Rate Has Hit Its Lowest Level in Recorded History - National | Globalnews.Ca Available online: https://globalnews.ca/news/10262331/canadas-fertility-rate-record-low/ (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Skakkebæk, N.E.; Lindahl-Jacobsen, R.; Levine, H.; Andersson, A.-M.; Jørgensen, N.; Main, K.M.; Lidegaard, Ø.; Priskorn, L.; Holmboe, S.A.; Bräuner, E.V.; et al. Environmental Factors in Declining Human Fertility. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2022, 18, 139–157. [CrossRef]

- Maestas, N.; Mullen, K.J.; Powell, D. The Effect of Population Aging on Economic Growth, the Labor Force, and Productivity. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 2023, 15, 306–332. [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada, S.C. Population Growth: Migratory Increase Overtakes Natural Increase Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-630-x/11-630-x2014001-eng.htm (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Silberman, A. N.B. Immigration Surge Causing School Staffing, Budget Pressures, Deputy Ministers Say. CBC News 2024.

- Bochove, D.; Patino, M.; Lin, J.C.; Dion, M.; Seal, T.; Orland, K. Housing Crisis, Packed Hospitals and Drug Overdoses: What Happened to Canada? Bloomberg.com 2024.

- Immigration, R. and C.C. #ImmigrationMatters: Canada’s Immigration Track Record Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/campaigns/immigration-matters/track-record.html (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Quality of Life Index by Country 2024 Mid-Year Available online: https://www.numbeo.com/quality-of-life/rankings_by_country.jsp (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Heaven, P. Canada’s Standard of Living Faces Worst Decline in 40 Years | Financial Post Available online: https://financialpost.com/news/canada-standard-of-living-faces-worst-decline-40-years (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Century Initiative Available online: https://www.centuryinitiative.ca/ (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Government of Canada, D. of J. Canada’s Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) Law Available online: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/cj-jp/ad-am/bk-di.html (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Euthanasia Fifth-Leading Cause of Death in Canada. National Review 2024.

- Euthanasia Was Canada’s 5th Leading Cause of Death in 2022: Report Available online: https://torontosun.com/news/national/euthanasia-was-canadas-5th-leading-cause-of-death-in-2022-report (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Medical Assistance in Dying: Legislation in Canada Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-services-benefits/medical-assistance-dying/legislation-canada.html (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Government of Canada, D. of J. Legislative Background: Medical Assistance in Dying Available online: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/other-autre/ad-am/p2.html#p2_4 (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- Canada, P.H.A. of Mental Illness Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/chronic-diseases/mental-illness.html (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Canada, P.H.A. of About Mental Illness Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/about-mental-illness.html (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Worldometer World Population Clock: 8.2 Billion People (LIVE, 2024) - Worldometer Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/ (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- WHO WHO Highlights Urgent Need to Transform Mental Health and Mental Health Care Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/17-06-2022-who-highlights-urgent-need-to-transform-mental-health-and-mental-health-care (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- CAMH The Crisis Is Real Available online: https://www.camh.ca/en/driving-change/the-crisis-is-real (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Government of Canada, S.C. Canada’s Population Clock (Real-Time Model) Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/71-607-x/71-607-x2018005-eng.htm (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Smetanin, P.; Stiff, D.; Briante, C.; Adair, C.E.; Ahmad, S.; Khan, M. The Life and Economic Impact of Major Mental Illnesses in Canada: 2011 to 2041 12/11.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information Children and Youth Mental Health in Canada 2022.

- Pearson, C.; Janz, T.; Ali, J. Health at a Glance: Mental and Substance Use Disorders in Canada 2013.

- Government of Canada, S.C. Mental Disorders and Access to Mental Health Care Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2023001/article/00011-eng.htm (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Boak, A.; Hamilton, H.A.; Adalf, E.M.; Henderson, J.L.; Mann, R.E. The Mental Health and Well-Being of Ontario Students, 1991-2017. Detailed Findings from the Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey (OSDUHS) (CAMH Research Document Series No. 47.), Toronto, ON 2018.

- Canada, P.H.A. of Mental Illness in Canada - Infographic Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/mental-illness-canada-infographic.html (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Fourth Annual Report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada 2022 Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/health-system-services/annual-report-medical-assistance-dying-2022.html (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Martin, C. Opinion | Medical Assistance in Dying Should Not Exclude Mental Illness. The New York Times 2023.

- Dying With Dignity Canada Allow MAID for Mental Illness Available online: https://www.dyingwithdignity.ca/advocacy/allow-maid-for-mental-disorders/ (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- Dembo, J.; Schuklenk, U.; Reggler, J. “For Their Own Good”: A Response to Popular Arguments Against Permitting Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) Where Mental Illness Is the Sole Underlying Condition. Can J Psychiatry 2018, 63, 451–456. [CrossRef]

- Bahji, A.; Delva, N. Making a Case for the Inclusion of Refractory and Severe Mental Illness as a Sole Criterion for Canadians Requesting Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD): A Review. Journal of Medical Ethics 2022, 48, 929–934. [CrossRef]

- Stoll, J.; Ryan, C.J.; Trachsel, M. Perceived Burdensomeness and the Wish for Hastened Death in Persons With Severe and Persistent Mental Illness. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Kamm, F.M. Boston Review. June 1 1997,.

- Raikin, A. From Exceptional to Routine. Cardus 2024.

- Government of Canada Regulations for the Monitoring of Medical Assistance in Dying, Canada Gazette, Part II 152, No. 16 2018.

- Moir, M.; Barua, B. Waiting Your Turn: Wait Times for Health Care in Canada, 2022 Report. 2022.

- Lucyk, D. Waitlist Deaths at Five-Year High Available online: https://secondstreet.org/2023/12/06/waitlist-deaths-at-five-year-high/ (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Dufour, L.; Metay, A.; Talbot, G.; Dupraz, C. Assessing Light Competition for Cereal Production in Temperate Agroforestry Systems Using Experimentation and Crop Modelling. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science 2013, 199, 217–227. [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada, S.C. Projected Population, by Projection Scenario, Age and Gender, as of July 1 Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710005701 (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- Worldometer Canada Population (2024) - Worldometer Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/canada-population/#google_vignette (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Government of Canada, S.C. The Daily — Study: Mental Disorders and Access to Mental Health Care Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/230922/dq230922b-eng.htm (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Government of Canada, S.C. Population Estimates, Quarterly Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000901 (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Canadian Association For Suicide Prevention Research and Statistics Available online: https://suicideprevention.ca/research-and-statistics/ (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Canada, P.H.A. of Suicide in Canada: Key Statistics (Infographic) Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/suicide-canada-key-statistics-infographic.html (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- WHO Canada Available online: https://data.who.int/countries/124 (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Government of Canada, S.C. The Daily — Canada in 2041: A Larger, More Diverse Population with Greater Differences between Regions Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220908/dq220908a-eng.htm (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Immigration, R. and C.C. Context Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/campaigns/canada-future-immigration-system/context.html (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Statista Immigrants in Canada 2023 Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/443063/number-of-immigrants-in-canada/ (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Growing to 100 Million Available online: https://www.centuryinitiative.ca/scorecard/growing-to-100-million (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Tanuseputro, P.; Wodchis, W.P.; Fowler, R.; Walker, P.; Bai, Y.Q.; Bronskill, S.E.; Manuel, D. The Health Care Cost of Dying: A Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study of the Last Year of Life in Ontario, Canada. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0121759. [CrossRef]

- Government Of Canada, S.C. Top 10 Leading Causes of Death (2019 to 2022) Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/231127/t001b-eng.htm (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Sulmasy, D.P.; Travaline, J.M.; Mitchell, L.A.; Ely, E.W. Non-Faith-Based Arguments against Physician-Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia. Linacre Q 2016, 83, 246–257. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.A. Ethical Issue of Physician-Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia. J Hosp Palliat Care 2023, 26, 95–100. [CrossRef]

- BBC BBC - Ethics - Euthanasia: Anti-Euthanasia Arguments Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/ethics/euthanasia/against/against_1.shtml (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- Finnis, J. A Philosophical Case against Euthanasia. In Euthanasia Examined: Ethical, Clinical and Legal Perspectives; Keown, J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1995; pp. 23–35 ISBN 978-0-521-58613-9.

- Government of Canada, S.C. The Mental Health of Immigrants and Refugees: Canadian Evidence from a Nationally Linked Database Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-003-x/2020008/article/00001-eng.htm (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- Ng, E.; Wilkins, R.; Gendron, F.; Berthelot, J.-M. Dynamics of Immigrants’ Health in Canada: Evidence from the National Population Health Survey Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-618-m/82-618-m2005002-eng.htm (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- Ng, E.; Pottie, K.; Spitzer, D. Official Language Proficiency and Self-Reported Health among Immigrants to Canada. Health Rep 2011, 22, 15–23.

- Vang, Z.; Sigouin, J.; Flenon, A.; Gagnon, A. The Healthy Immigrant Effect in Canada: A Systematic Review. Population Change and Lifecourse Strategic Knowledge Cluster Discussion Paper Series/ Un Réseau stratégique de connaissances Changements de population et parcours de vie Document de travail 2015, 3.

- Fuller-Thomson, E.; Noack, A.M.; George, U. Health Decline Among Recent Immigrants to Canada: Findings From a Nationally-Representative Longitudinal Survey. Can J Public Health 2011, 102, 273–280. [CrossRef]

- Ramesar, V. They Came to Canada for Their Dreams. Instead They Found a Mental Health Nightmare. CBC News 2023.

- George, U.; Thomson, M.S.; Chaze, F.; Guruge, S. Immigrant Mental Health, A Public Health Issue: Looking Back and Moving Forward. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015, 12, 13624–13648. [CrossRef]

- Fung, K.; Guzder, J. Canadian Immigrant Mental Health. In Mental Health, Mental Illness and Migration; Moussaoui, D., Bhugra, D., Tribe, R., Ventriglio, A., Eds.; Mental Health and Illness Worldwide; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2021; pp. 187–207 ISBN 978-981-10-2364-4.

- Mildred, J. The Economist. August 29 2018,.

- Remmelink Remmelink Report Available online: http://www.euthanasia.com/hollchart.html (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- van der Maas, P.J.; van Delden, J.J.M.; Pijnenborg, L.; Looman, C.W.N. Euthanasia and Other Medical Decisions Concerning the End of Life. The Lancet 1991, 338, 669–674. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).