1. Introduction

Plastic surgery is a diverse and evolving speciality, which encompasses reconstructive surgery, aesthetic surgery, burn care, oncoplastic procedures, and management of skin malignancies and congenital abnormalities [

1]. Basic knowledge of the speciality is relevant to all non-plastic doctors, including junior doctors, as they may engage in the care of plastic surgery patients throughout their careers due to the frequent collaboration between plastic surgeons and other medical and surgical specialities to ensure a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach to patient care [

1].

Non-plastic doctors may utilise basic principles inherent to plastic surgery such as burn and wound management, local anaesthesia administration and suturing techniques as these are transferable across various medical and surgical specialities. This is evident from the inclusion of plastic surgery-related competencies within the curricula of non-plastic surgery disciplines, including family medicine [

2], emergency medicine [

3], and general surgery [

4].

Foundation year (FY) doctors, as the most junior doctors in the medical workforce, are often at the forefront of patient care through responsibilities that include patient assessment and management, escalation of cases to senior doctors as required, obtaining consent for procedures, participation in multidisciplinary discussions, and liaising with the appropriate specialities [

5] Plastic surgery knowledge and principles may need to be utilised during these clinical duties.

Despite the significance of plastic surgery in medical practice, even to junior, non-plastic doctors, the formal education regarding plastic surgery is limited within many medical school curricula, in keeping with our local experience, with limited clinical attachments during medical school and work placements during the early stages of doctors’ careers [

6,

7,

8].

An illustration of this educational gap is evidenced by studies showing the lack of familiarity with the scope and services offered by plastic surgeons among medical students [

9], junior doctors [

1,

10], and various medical and surgical specialists [

11,

12] such as primary care physicians [

13]. Junior doctors were found to be aware of only 10% more procedures performed by plastic surgeons, compared to the general public [

1]. Poor understanding of the scope of plastic surgery among non-plastic doctors can result in a delay in proper patient management and impact patient safety [

12].

Literature shows that although most ward-based wound management is provided by FYs, just 32% of questions related to wound types, care and dressings were answered correctly by FYs, whilst none of the FYs felt comfortable with their knowledge of wound types and dressings [

14]. Junior doctors have been shown to lack confidence, exposure and experience in managing plastic surgery-related cases, resulting in a decreased competence in managing routine plastic surgery cases, contributing to the inappropriate initial management of plastic surgery cases and referrals [

15].

Despite the acknowledgement of the critical role that FY doctors play in patient care and the existence of plastic surgery-related knowledge gaps, there is a paucity in research examining their first-hand experiences during clinical practice concerning plastic surgery.

This study aimed to explore the first-hand experiences of FY doctors concerning patient assessment and management, consultations and referrals related to plastic surgery to gain insight into the perceived confidence, knowledge gaps, skills and needs of FY doctors to better understand any disparity present between the actual lived experiences of FYs, and the educational activities and curriculum delivered.

This insight will enable the author to answer the research question, ‘What are the plastic surgery related experiences, needs, confidence and knowledge gaps of foundation year doctors?’ and suggest ways to align the curriculum with the current needs of FY doctors to improve knowledge gaps.

Improvement in the knowledge gaps is desired to improve the quality of patient care and safety through improved clinical practice [

16] and referral patterns [

17].

2. Materials and Methods

Context and Setting

FY doctors are the most junior doctors in the healthcare system being studied. They are new medical graduates who enter the Foundation program, a 2-year-long postgraduate training programme as their first work placement. Upon its’ completion, they become warranted to practise independently and continue specialising in a chosen speciality.

Each doctor has eight, three-month-long rotations in addition to formal teaching. Mandatory rotations include general medicine, general surgery and Accident & Emergency (A&E). The other five rotations include a mix of medical and surgical subspecialties, such as Plastic Surgery.

The work of an FY doctor includes participation in firm-based ward rounds, inpatient documentation, formulation of discharge letters, execution of simple practical procedures, initial patient assessment and management, escalation of cases to senior doctors, and consultations with relevant specialities. They are often the first point of contact for inpatients during on-call hours.

Study Design

This study used a qualitative research design, employing an inductive approach for the study to be flexible as it progresses and adjust according to new findings elicited through the data collection [

18]. This was done to gain an in-depth and rich understanding of the complex day to day work experiences of FY doctors.

Phenomenology was used to understand the lived experiences of FY doctors, through the descriptions provided by the FYs themselves, recognising the subjective nature of individual experiences and perceptions [

18].

Participants and Procedure

The study population is FY doctors in the second year of the foundation program. This minimum amount of experience was necessary due to the nature of the question of the study which explores the work life of FY doctors.

A purposive sampling strategy was used to recruit volunteers through an email sent to eligible participants by the class representative. A group of heterogeneous participants was selected from the volunteers according to their future speciality interests and previous exposure to a plastic surgery rotation. Eight interviews were conducted until saturation of meaning was achieved.

A 60 to 75 minute semi-structured individual interview as detailed in

Appendix A was done, using open-ended questions was carried out in person by the researcher. The interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Written and verbal information was provided to all participants, and written consent was obtained. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Warwick and the Malta National People Management Division Office.

Analysis

Reflexive thematic analysis was carried out by the researcher (NG) using the six steps as described by Braun & Clarke [

19]. Data familiarisation was done through the conduction of the interviews, listening to the interview audio, transcription of the interviews and rereading of the transcript. A predominantly inductive approach was used to produce codes reflective of the data collected [

20]. Relationships between the codes were used to identify themes, which were defined and named and with a report produced to reveal novel information about the experiences of FY doctors. Analysis was carried out using NVivo 14.

3. Results

Eight doctors with the characteristics depicted in

Table 1 participated in this study.

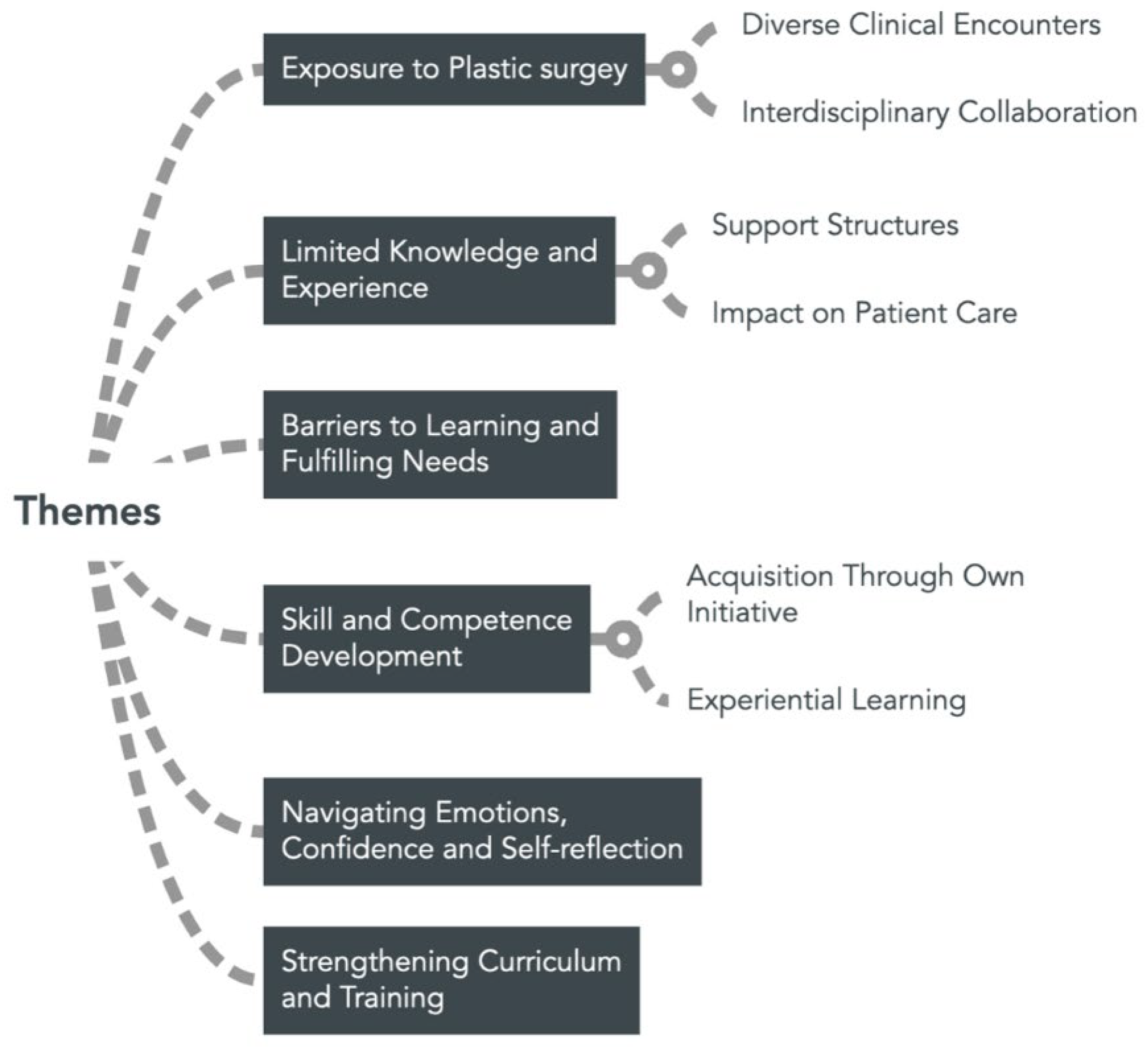

The identified themes are depicted in

Figure 1.

3.1. Theme 1: Exposure To Plastic Surgery

3.1.1. Subtheme: Diverse Clinical Encounters

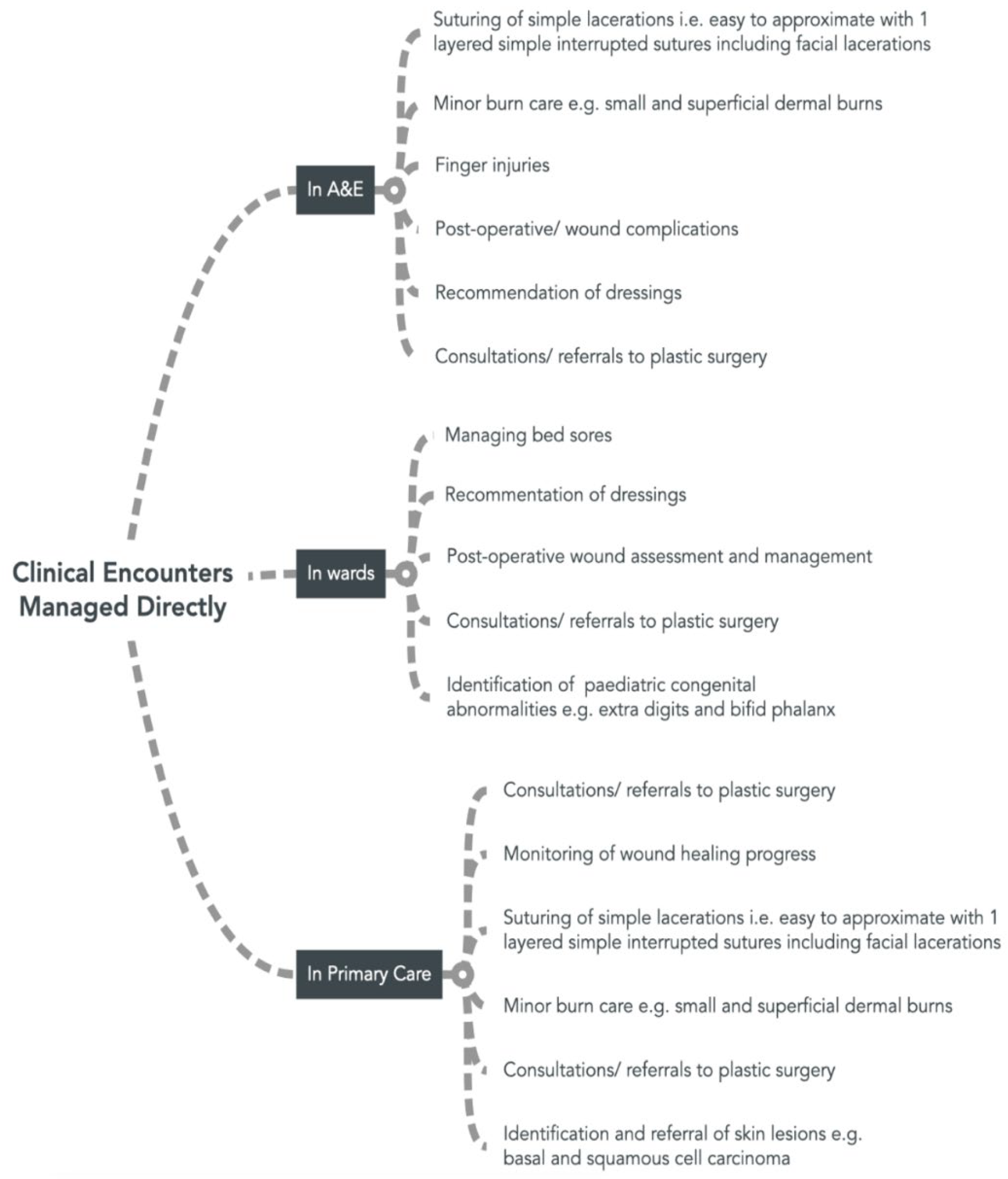

Participants reported encountering plastic surgery, and its’ principles in A&E, primary care and ward settings. The common cases managed directly and independently by FYs are outlined in

Figure 2.

Participants reported encountering more complex cases during their rotations, including severe burn cases and lacerations with tissue loss or requiring multi-layered closure. However, these were typically managed by senior doctors and therefore involvement of FYs was limited to logistical and administrative support such as patient documentation and consulting with on-call plastic surgeons rather than direct patient management.

Doctor 7, who worked in plastic surgery, highlighted his role in assisting in theatre and participating at the ‘Dressing Clinic’, a service offered by the plastic surgery department where patients with minor acute trauma and post-op cases are reviewed.

3.1.2. Subtheme: Interdisciplinary Collaboration

Close liaison with plastic surgery whilst working in multiple different specialities was a prominent theme.

Doctor 2 recounted her experience in orthopaedics, where she was caring for a patient with an open fracture:

He was having the vacuum-assisted closure done and needed to have a skin graft…we used to see the wound.. sometimes by myself… seeing that it’s not infected and is improving ... they [plastic surgeons] used to come and see the wound themselves to see when we should organise the graft. We used to liaise with them a lot… to organise the graft … for pre-op care, when to stop the anticoagulation, what blood tests to take, whether they needed anything in particular to prepare the [operation] area.

Doctor 5 recalled collaborating with plastic surgeons whilst working in vascular surgery and ear, nose and throat (ENT) , due to ‘cross-specialty’ cases. In vascular, his role involved referring patients with skin loss to plastic surgery. In ENT, his role was ‘more direct’ as FYs were in charge of the ENT casualty clinic. He recalled the involvement of plastics in cases with facial trauma with skin loss, and joint cases due to pathologies which involve both ENT and plastics.

Doctor 6 recalled ’a multidisciplinary approach’ during her breast surgery rotation when patients would opt to have an implant done by plastic surgeons during mastectomy procedures.

3.2. Theme 2: Limited Knowledge and Experience

This study identified a dominant theme of FYs executing their clinical responsibilities whilst perceiving their knowledge and experience as limited, saying ’we lack the basic skills that we need as a doctor’ (D1). Participants expressed feelings of ill-preparedness, evident in statements such as the following by doctor 2:

I feel like I have merely no knowledge; I can’t say I’m really confident in managing burns, for example, because I’m not. I started my A&E rotation and I didn’t know how to suture, I didn’t know how to hold an instrument, anything like that.

Uncertainty around clinical management was expressed, with a participant saying ‘The nurses will come up to you and ask you what you are going to do, and in reality, I wouldn’t know’ (D1). Another observed similar sentiments among his peers, remarking, ‘None of [my friends] have this in-depth knowledge with plastics’ (D3).

Participants recounted performing tasks e.g., suturing, during FY for the first time, illustrating a lack of familiarity and prior experiences. Others noted encountering new challenges despite having some prior experience, such as managing cosmetically sensitive lacerations in the face and children, and different finger injuries. Moreover, participants reflected on encountering unfamiliar procedures including skin grafts and post-mastectomy breast reconstructions.

Wound care was described as a weak point with one participant claiming ‘even basic wounds are a problem sometimes’ (D6). Dressing choice was cited as being ‘very confusing’ (D5), with participants claiming they were not aware of the different types of dressings and indications for their use.

Some expressed uncertainty about the services offered by plastic surgery, while others confessed that even when recognising a particular condition falling under the remit of plastic surgery, they would not know why, or what plastic surgery could potentially offer the patient.

3.2.2. Subtheme: Support Structures

Trainees often recognised their own limitations, prompting them to seek support from a professional with more experience.

Support from the FY’s direct senior e.g., more senior trainees, was the most common first choice of help for advice on patient management, decisions to refer patients to plastic surgery, help with practical procedures, suturing techniques, needle and suture material choice. Nurses were recognised as a significant support structure with difficulties concerning dressing choice and wound care.

3.2.3. Subtheme: Impact on Patient Care

FYs expressed concerns about safe patient care due to their lack of baseline skills and knowledge and incremental learning process, saying this made them ‘more prone to make mistakes, unfortunately, because it’s trial and error thing’ (D1).

Consequently, they often opted for immediate referring of ‘cosmetically relevant’ (D5) cases and other plastic surgery cases to plastic surgery as illustrated by a participant saying; ‘If I see it, I will need to refer it. That’s beyond my knowledge, I’m not experimenting’ (D3). A trainee raised the concern that inappropriate referrals could ‘overload the system’ (D6).

Despite the low threshold to refer, participants recalled encountering delays in a patient being referred to plastic surgery and thus promptly receiving the care required, as they were initially mistakenly referred to another speciality, such as orthopaedics or dermatology, due to a lack of knowledge regarding services offered by plastic surgery.

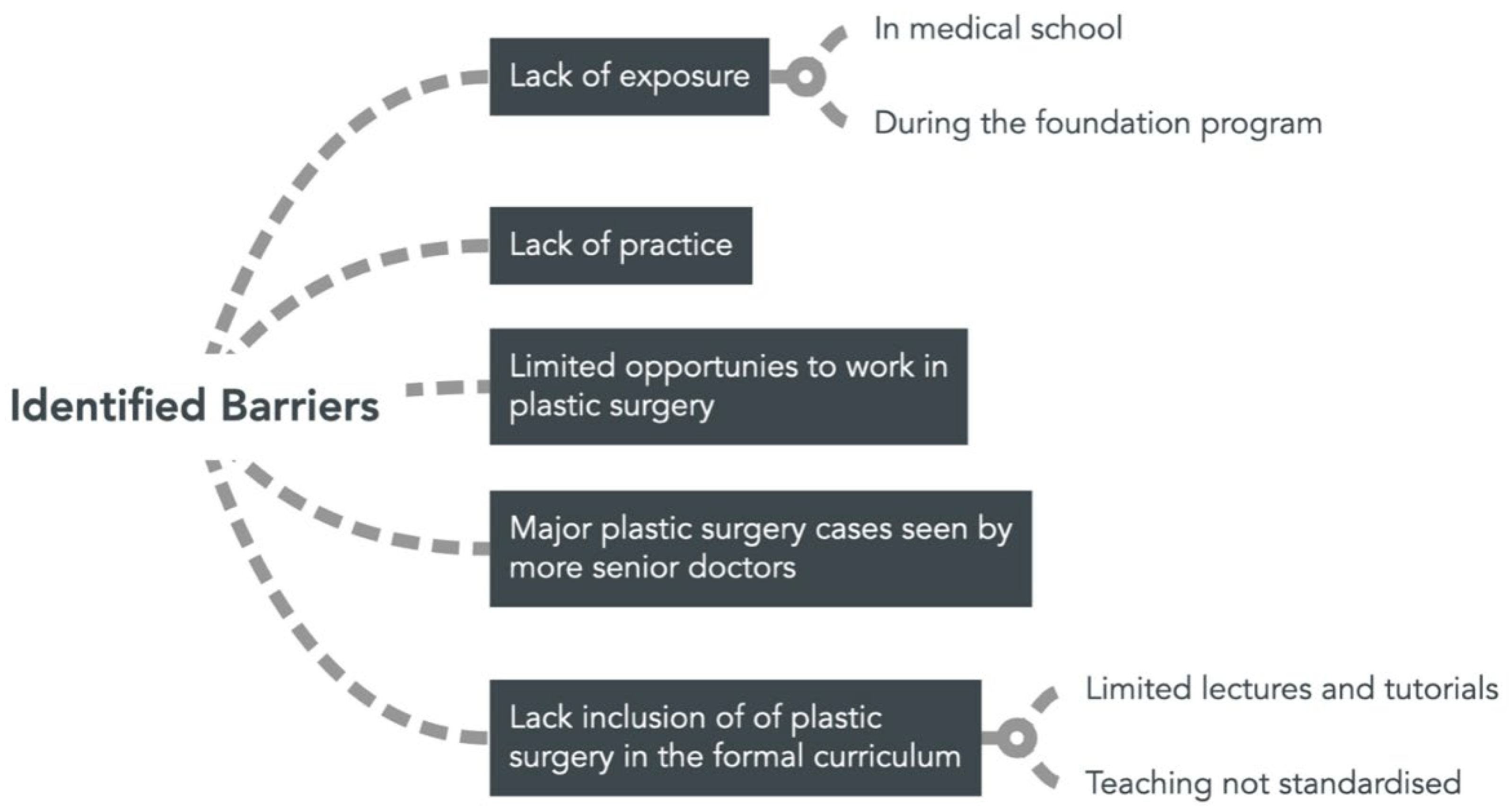

3.3. Theme 3: Barriers to Learning and Fulfilling Needs

Multiple barriers to learning and fulfilling needs were identified, summarised in

Figure 3.

A lack of exposure to plastic surgery was identified as one of the main barriers to learning with one participant claiming ‘I’m not that skilled because I didn’t have enough exposure’ (D3). This was felt to start from medical school, due to limited rotations, lectures and tutorials, with a participant claiming plastic surgery ‘is not given enough importance in medical school’ (D6).

Limited opportunities to work in plastic surgery as an FY, with only two FYs working in plastic surgery every three months, contributed to the lack of exposure. Not working in plastic surgery was described as ‘a major setback in teaching of plastics’ (D5).

Participants felt that more serious major cases were often ‘fast-tracked’, saying ‘in A&E, if there was a major case which required plastics, the seniors would immediately take over’ (D1) thus giving them less chance to expose and familiarise themselves with plastic surgery.

Limited exposure led to insufficient practice, with participants reporting becoming deskilled and forgetting theoretical knowledge after exams and courses, stating ‘you don’t get to practice what you learn’ (D5).

A lack inclusion of of plastic surgery in the formal curriculum was identified as a major barrier to learning, with doctor 2 claiming:

We are not given any training… I don’t think [our needs] are addressed enough because … we don’t have any training organised apart from the lectures and the lectures didn’t cover plastics, we never had anything about basic wound care or about basic plastics management.

Trainees do not feel that the formal curriculum at present is ‘adequate’ (D5) because ‘the basic stuff is not given much importance’ (D1) and ‘there are still gaps in the knowledge’ (D6). FYs do not feel the curriculum supports their day-to-day needs, as evidenced by a trainee claiming ‘There are things which you deal with day to day and you get asked questions daily from other specialities such as TVU or nurses … unless you’ve done your research or asked around before, then you wouldn’t know’ (D5).

FYs perceive access to teaching as not standardised and unpredictable, with one stating ‘we’re always banking on someone else telling you about [referral pathways]’ (D6) while another agreed, saying ‘it’s up to the consultant or the firm to teach you, there isn’t anything set in stone’ (D2).

3.4. Theme 4: Skill and Competence Development

3.4.1. Subtheme: Acquisition through Own Initiative

Participants expressed a desire to develop clinical competence and said that ensuring access to teaching to gain this knowledge and competence was often left up to their own initiative. One participant said ‘to be competent in my work, I had to do extra reading. If I just followed medical school, it wouldn’t have been enough’ (D2). Other participants agreed, saying they chose to attend optional courses, such as the ‘Basic Surgical Skills’ and workshops organised by student organisations to develop their suturing skills, burn and wound care knowledge.

A need for own initiative during working hours was echoed by participants stressing that learning was dependant on the FY’s desire to learn and the willingness of seniors to teach ‘If you want to learn something, you need to go ahead and learn it yourself… it’s just self-teaching, you need to go ask a senior, sit down with them, shadow and ask and just learn’ (D7).

Doctor 2 reported that FYs often had to go beyond their clinical responsibilities to gain access to informal teaching:

Our work is more consults and discharge letters, and then you have to do things out of your own interest above that to learn. You have to stay after hours to try and scrub.. to go to outpatients and these things … to learn you have to do it out of your own interest.

3.4.2. Subtheme: Experiential Learning

Experiential learning, rather than formal education, was found to be the primary source of FY knowledge acquisition, with one participant strongly stating ‘I feel like experience has taught me, not the curriculum’ (D6).

Participants emphasised their knowledge, competence and skills were improved through practical experience and exposure gained on the job, noting significant improvements since the beginning of the FY programme and stating ‘you learn as you work’ and ‘every time you do it, it becomes easier’ (D8). This progress was attributed to managing post-operative care, obtaining surgical consent from patients, repeatedly performing tasks like administering local anaesthesia and suturing, encountering various wounds and dressings and engaging in consultations with plastic surgery.

Additionally, Doctor 7 emphasised the invaluable learning gained during his plastic surgery rotation, particularly in acquiring specialised plastic surgery knowledge and developing skills in case prioritisation. He foresees utilising this in his future career, stating:

The most informative and beneficial thing that I had [from working in plastics] was knowledge on dressings, seeing different types of wounds, and knowing how to make decisions based on my knowledge from plastic surgery. Like what is serious, what is not that serious, what needs urgent action, what doesn’t.

He also highlighted significant improvements in local anaesthesia administration, choice of dressings and suturing, expressing ‘In plastics, I was doing it much, much more often … the skill, the handling, the method that I use, I felt much more comfortable doing than before’ (D7).

Personal experiences were cited as a source of learning. One participant recalled observing the burn treatment her mother received at a health centre and its follow-up, saying ‘I think [learning] was more from that rather than from actually someone teaching us how to deal with a burn’ (D2).

3.5. Theme 5: Navigating Emotions, Confidence and Self-Reflection

Participants expressed feeling ‘lost’ (D8) and a lack of confidence and uncertainties in describing burns, suturing, post-operative management and recommending dressings. This was frequently attributed to minimal exposure and training to plastic surgery with participants stating ‘I’m not at all [confident] because as I said, I never had training, I never worked in the speciality’ (D1).

Participants reported this lack of confidence impacting their emotional state, with some admitting to feelings of panic. One participant shared ‘I think because of the lack of interaction … you don’t get to practice what you learn. So when you actually get that type of case, it’s a bit of a panic situation’ (D5).

Others reported experiencing anxiety, worry and rumination over patient interactions, by reflecting and evaluating the adequacy of their performance and subsequent clinical progression of the patient. This was driven by their desire to provide optimal service to the patients, especially in children and cosmetically sensitive areas such as the face. One participant recalled her experience with a child, thinking ‘It’s in their face, if you make a mistake, it can leave them with the defect for a long time’ (D2).

3.6. Theme 6: Strengthening Curriculum and Training

A call for change was expressed. Doctor 1 stated:

[Our needs] are not well addressed, for sure. I mean, in two years, the things I learned were mainly through experience while working … and through courses, which I did out of my own initiative, not because they were offered by the foundation school. I don’t think enough is being done to be fair … there needs to be some change.

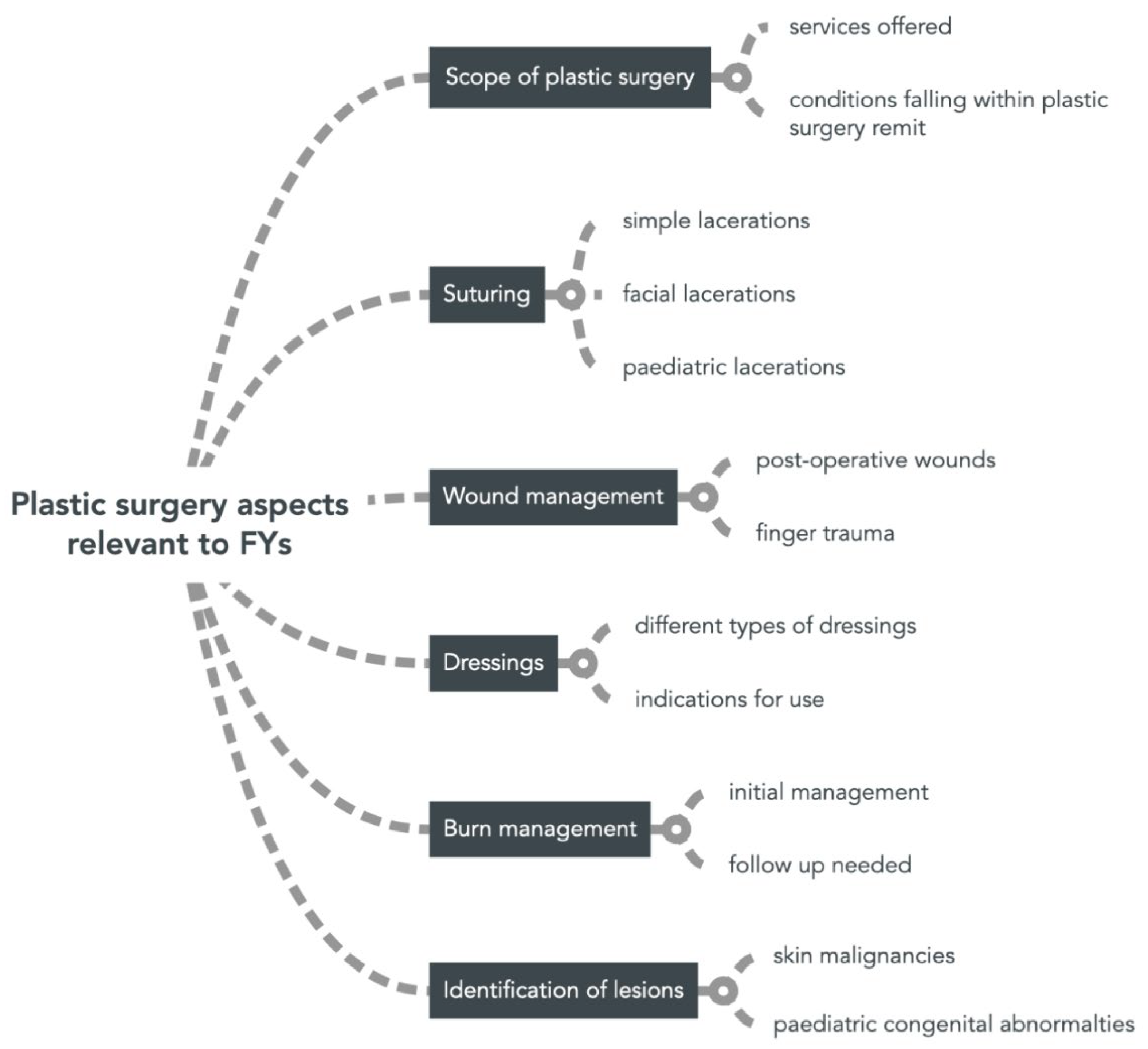

FYs mainly expressed a desire for ‘more basic knowledge’ (D1), and more teaching opportunities on suturing, dressings, wound management, burn care, abnormal skin lesions. Participants stressed that these are ‘basic skills … that any doctor should have’ (D1) and that these would be beneficial both in FY and future practice.

More information about the scope and services offered by plastic surgery was also widely requested, with a participant saying ‘when you refer, you should know what you’re asking for’ (D5) and claimed this will help them to better relay and understand information resulting from consultations.

Many also expressed the desire for more opportunities to be exposed to plastic surgery in the form of a rotation, saying ‘If I had to choose, I would expose myself to a lot more’ (D5).

In discussing potential improvements, FYs suggested the implementation of more practical, in-person workshops and interactive small-group tutorials, the introduction of new guidelines and orientation to existing ones, and the integration of plastic surgery subjects into the weekly FY lectures. This is to improve their competence in practical skills and theoretical knowledge of soft tissue trauma management, wound and burn care, finger trauma, dressing choice, skin malignancies, paediatric congenital abnormalities and the scope of plastic surgery.

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings and Implications

To effectively address trainees’ needs, educators must grasp the realities of their day-to-day experiences. This study highlighted that plastic surgery, contrary to common misconceptions, extends beyond cosmetic surgery [

12] and is not a niche speciality dealt with only by plastic surgeons, but rather, it represents a set of principles and diverse services, which feature in the work life of junior doctors.

FY doctors play four roles; an independent practitioner, support to more senior medical staff, an intermediary between their current speciality and plastic surgery, and a learner through the former three roles. These roles are in keeping with those described in the literature [

5]. This study contributes novel insights into how plastic surgery integrates into these roles. Tasks within these roles fall well within the Foundation Professional Capabilities (FPC), which are the building blocks of the ‘Higher Level Outcomes’ of the Foundation Programme curriculum [

8].

Alignment between roles, tasks and FPCs is depicted in further detail in

Table 2.

It is therefore concerning that the participants are carrying out clinical responsibilities which fall within the FPC, whilst feeling ill-prepared and perceiving their knowledge and experience as limited. However, this strong sense of lack of preparedness is not surprising, with other studies also reporting FYs feeling ill-prepared and lacking confidence in clinical knowledge, diagnostic skills, procedural skills and decision making during the foundation programme [

21,

22,

23]. A lack of preparedness was also reported specifically in ’small’ surgical subspecialties similar to plastic surgery, such as ENT [

24].

A negative impact on the emotions of FYs as a result of their limited knowledge and ill-preparedness, such as worry and resultant rumination was reported, in keeping with current literature [

25]. Negative emotions experienced by doctors can affect both clinician well-being and have an impact on patient care [

26,

27].

The educational methods used by the Foundation programme are a blend of experiential learning, self-development and direct learning [

8]. This study highlighted that experiential learning and self-development were the two more prominent methods applied in plastic surgery education. FYs demonstrated experiencing Kolb’s experiential learning cycle, whereby they experienced patient encounters and informal teaching by seniors and reflected on this to conceptualise ideas to implement during their next patient encounter [

28]. Experiential learning helps to acquire new medical knowledge, consolidate previous knowledge, and enhance interpersonal skills [

29]

. Leaning on the job has been shown to increase preparedness for practice [

30]. Self-development was experienced through ‘non-core’ learning activities such as external courses and independent reading. This reveals FYs as being ‘adult learners’, following the principles of andragogy, and being responsible for their own learning according to their identified needs and goals [

31].

Despite this, FYs still felt that their needs were not being met, with many reporting difficulties in delivering optimal care using patient assessment, management and practical skills utilising basic plastic surgery principles. This study corroborates existing literature documenting deficiencies in surgical skill teaching and competencies among junior doctors [

32], while contributing novel insights in the specific plastic surgery aspects and skills relevant to FYs and their educational needs, summarised in

Figure 4.

FYs expressed a desire for integration of plastic surgery into the ‘core’ learning delivered as a part of the FY programme’s direct teaching. Although they remarked that didactic formal lectures are beneficial to provide an element of structure and overview to the topic, they expressed a preference for small group sessions, simulations and practical hands-on sessions. These have been shown to support the development of discussion, critical thinking and collaborative skills, increase engagement and interest rates, and provide opportunities for closer monitoring of learning and targeted instruction [

33]

4.2. Limitations and Potential Bias

Selection bias was present as recruitment was limited to those who volunteered and were available to participate. This study focused on experiences and perceptions from the point of view of an FY, and may not represent or be representative of the sentiment of the larger FY cohort or senior doctors.

4.3. Further Research

Future research should further explore the effect on plastic surgery patient care as a result of FY preparedness and competence. Studies focused on optimising educational strategies e.g., innovative teaching methods, and curriculum integration to address FYs specific needs in plastic surgery are recommended.

5. Conclusions

This study contributes novel findings of first-hand experiences of FY doctors concerning plastic surgery. It reveals how plastic surgery features diversely in the work life of junior FY doctors. These clinical scenarios are navigated with a background of lack of knowledge and confidence, which influences patient care and FY wellbeing. The acquisition of knowledge and confidence primarily occurs through experiential learning and individual initiative. FY doctors expressed a need for enhanced formal training and curriculum modifications to optimise patient care in their current and future roles. We propose the integration of plastic surgery into the core curriculum through lectures, practical small-group sessions, and opportunities to work in plastic surgery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.G; methodology, N.G.; software, N.G.; validation, N.G; formal analysis, N.G.; investigation, N.G.; resources, N.G; data curation, N.G; writing—original draft preparation, N.G.; writing—review and editing, N.G.; visualization, N.G; project administration, N.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Malta National People Management Division Office (no protocol number assigned, date of approval 22/06/2023) and Ethics Committee of University of Warwick (no protocol number assigned, date of approval 27/07/2023)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Full interview data is unavailable due to ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Interview guide

Question 1: Can you recall any plastic surgery related encounters you had during your work as foundation doctor?

Possible prompts/ follow up question:

- -

This may include patient contact in wards, at GP/A&E Services, consultations with plastic surgeons, carrying plastic surgery procedures

- -

How did you manage these encounters?

Question 2: How did you feel during these plastic surgery related encounters?

ossible prompts/ follow up question:

- -

What were the key aspects and challenges of these scenarios?

- -

How did these encounters impact your learning, and knowledge about plastic surgery

- -

In the ideal scenario, would you have preferred that something was done differently? e.g more support

Question 3: In your experience, what are the common knowledge gaps or areas of difficulty related to plastic surgery encounters?

Possible prompts/ follow up question:

- -

Can you mention any specific situations where you felt need for additional knowledge or support to manage these scenarios?

Question 4: How confident do you feel in your ability to manage plastic surgery scenarios?

Possible prompts/ follow up question:

- -

Are there specific areas where you feel more confident or less confident and why?

- -

Do you feel that this is a need that is specific to you as an individual, or is this common among your peers?

Question 5: How do you envision using plastic surgery in your future career?

Possible prompts/ follow up question:

- -

E.g consulting, carrying out procedures yourself, management of patients

- -

Do you feel well prepared to carry this out? Why?

Question 6: Have you participated in any specific educational activities related to plastic surgery?

Possible prompts/ follow up question:

- -

This may be during FY training/ outside of hospital, courses, rotations etc

- -

Can you describe them?

- -

How do you perceive the effectiveness of these activities in improving your plastic surgery knowledge and skills?

Question 7: Based on your experiences and needs related to plastic surgery, how well do you think the current foundation year curriculum address these areas?

Possible prompts/ follow up question:

- -

Are there any areas you feel that the curriculum should be covering, but is not, or vice versa?

- -

How do you perceive the alignment between you experiences and the curriculum?

Question 8: From your perspective, what changes or improvements do you think should be made to the current FY curriculum to better address the plastic surgery related needs of FY’s?

Possible prompts/ follow up question:

- -

Are there any specific resources or activates you believe would be valuable in enhancing FY plastic surgery training?

- -

How do you envision the ideal integration of plastic surgery education in the FY curriculum?

References

- Helmy, Y.; Alfeky, H. Plastic surgery interaction with other specialties: Scope of specialty in different minds. Plast. Surg. Mod. Tech. 2017, 3(4). [CrossRef]

- Edward, Z.; Mario, S.; Gunther, A. Specialist Training Programme in Family Medicine – Malta; Malta College of Family Doctors: Malta, 2017. Available online: https://deputyprimeminister.gov.mt/en/regcounc/msac/Documents/MCFD%20STP-Family%20Medicine%203rdEd%20-%202017%20(updated).pdf (accessed on 14 January 2013).

- Association of Emergency Physicians of Malta. Training in the Speciality of Emergency Medicine; Available online: https://deputyprimeminister.gov.mt/en/regcounc/msac/Documents/TRAINING%20IN%20THE%20SPECIALTY%20Of%20EMERGENCY%20MEDICINE%20for%20SAC%20Nov%202015.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- The ASM Curriculum Committee. Association of Surgeons of Malta Charter on Training in General Surgery; Available online: http://fpmalta.com/uploads/2012/Careers/14.generalsurgery_trainingprog%20(1).pdf (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Vance, G.; Jandial, S.; Scott, J.; Burford B. What are junior doctors for? The work of foundation doctors in the UK: A mixed methods study. BMJ Open 2019, 9(4). [CrossRef]

- Wade, R.G.; Clarke, E.L.; Figus A. Plastic surgery in the undergraduate curriculum: A nationwide survey of students, senior lecturers, and consultant plastic surgeons in the UK. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2013, 66(6), 878–880. [CrossRef]

- Rees-Lee, J.E.; Lee, S. Reaching our successors: The trend for early specialization and the potential effect on recruitment to our specialty. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2008, 61(10), 1135–1138. [CrossRef]

- UK Foundation Programme. UK Foundation Programme Curriculum 2021; Available online: https://foundationprogramme.nhs.uk/curriculum/ (accessed on 13 January 2023).

- Agarwal, J.P.; Mendenhall, S.D.; Moran, L.A.; Hopkins, P.N. Medical student perceptions of the scope of plastic and reconstructive surgery. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2013, 70(3), 343–349. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A.D.; Dos Passos, G.; Hudson, D.A. The scope of plastic surgery. S. Afr. J. Surg. 2013, 51(3), 106. [CrossRef]

- Panse, N.; Panse, S,; Kularni, P.; Dhongde, R.; Sahasrabudhe, P. Awareness and perception of plastic surgery among healthcare professionals in Pune, India: Do they really know what we do? Plast. Surg. Int. 2012, 2012, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Mrad, M. A.; Al Qurashi, A. A.; Mortada, H.; Shah Mardan, Q. N. M.; Abuthiyab, N.; Al Zaid, N.; Al Bakri, H.; Mullah, A. Do our colleagues accurately know what we do? Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2022, 10(2). [CrossRef]

- Tanna, N.; Patel, N. J.; Azhar, H.; Granzow, J. W. Professional perceptions of plastic and reconstructive surgery: What primary care physicians think. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010, 126(2), 643–650. [CrossRef]

- Catton, H.; Geoghegan, L.; Goss, A. J.; Zarb Adami, R.; Rodrigues, J. N. Foundation doctor knowledge of wounds and dressings is improved by a simple intervention: An audit cycle-based Quality Improvement Study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2020, 51, 24–27. [CrossRef]

- Gorman, M.; Lochrin, C.; Khan, M. A. A.; Urso-Baiarda, F. Waiting times and decision-making behind acute plastic surgery referrals in the UK. J. Hosp. Adm.2012, 2(1), 68. [CrossRef]

- Leung, B. C.; De Leo, A.; Khundkar, R.; Leung, N.; Reed, A.; Cogswell, L. Improving confidence and practical skills in plastic surgery for medical students and junior doctors: A one-day session. Surg. Sci. 2016, 7(9), 433–442. [CrossRef]

- Jabaiti, S.; Hamdan-Mansour, A. M.; Isleem, U. N.; Altarawneh, S.; Araggad, L.; Al Ibraheem, G. A.; Alryalat, S. A.; Thiabatbtoush, S. Impact of plastic surgery medical training on medical students’ knowledge, attitudes, preferences, and perceived benefits: Comparative study. J. Public Health Res. 2021, 10(3). [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, R.; Biklen, S.K. Qualitative Research for Education: An Introduction to Theory and Methods, 5th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2007.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 57–71. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; SAGE: London, UK, 2013.

- Kellett, J. et al. The preparedness of newly qualified doctors – Views of foundation doctors and supervisors. Med. Teach. 2015, 37(10), 949–954. [CrossRef]

- Monrouxe, L. V.; Bullock, A.; Gormley, G.; Kaufhold, K.; Kelly, N.; Roberts, C. E.; Mattick, K.; Rees, C. New graduate doctors’ preparedness for practice: A multistakeholder, multicentre narrative study. BMJ Open 2018, 8(8). [CrossRef]

- Morrow, G.; Johnson, N.; Burford, B.; Rothwell, C.; Spencer, J.; Peile, E.; Davies, C.; Allen, M.; Baldauf, B.; Morrison, J.; Illing, J. Preparedness for practice: The perceptions of medical graduates and clinical teams. Med. Teach.2012, 34(2), 123–135. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, G.R.; Bacila, I.A.; Swamy, M. Does current provision of undergraduate education prepare UK medical students in ENT? A systematic literature review. BMJ Open 2016, 6(4). [CrossRef]

- Lundin, R. M.; Bashir, K.; Bullock, A.; Kostov, C. E.; Mattick, K. L.; Rees, C. E.; Monrouxe, L. V. “I’d been like freaking out the whole night”: Exploring emotion regulation based on junior doctors’ narratives. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2017, 23(1), 7–28. [CrossRef]

- Resnick, M.L. The effect of affect: Decision making in the emotional context of health care. In Proceedings of the 2012 Symposium on Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care; Human Factors and Ergonomics Society: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Salyers, M. P.; Bonfils, K. A.; Luther, L.; Firmin, R. L.; White, D. A.; Adams, E. L.; and Rollins, A. L. The relationship between professional burnout and quality and safety in healthcare: A meta-analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2016, 32(4), 475–482. [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984.

- Yardley, S.; Teunissen, P.W.; Dornan, T. Experiential learning: Amee guide no. 63. Med. Teach. 2012, 34(2). [CrossRef]

- Illing, J. C.; Morrow, G. M.; Rothwell, C. R. (née Kergon); Burford, B. C.; Baldauf, B. K.; Davies, C. L.; Peile, E. B.; Spencer, J. A.; Johnson, N.; Allen, M.; Morrison, J. Perceptions of UK medical graduates’ preparedness for practice: A multi-centre qualitative study reflecting the importance of learning on the job. BMC Med. Educ. 2013, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Knowles, M.S. The Modern Practice of Adult Education: From Pedagogy to Andragogy, Revised and Updated; Cambridge Adult Education: New York, NY, USA, 1980.

- Glossop, S. C.; Bhachoo, H.; Murray, T. M.; Cherif, R. A.; Helo, J. Y.; Morgan, E.; and Poacher, A. T. Undergraduate teaching of surgical skills in the UK: Systematic review. BJS Open 2023, 7(5). [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, S.; Brown, G. Effective Small Group Learning: Amee guide no. 48. Med. Teach. 2010, 32(9), 715–726. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).