Submitted:

18 September 2024

Posted:

20 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

| CONTENTS | |

| Abstract | |

| 1 | Introduction |

| 2 | Peripheral Processes in Muscle Fatigue |

| 2.1 | Peripheral Muscle Fatigue in Health |

| 2.1.1 | Metabolic Factors in Muscle Fatigue |

| 2.1.2 | Disturbances in Excitation-contraction Coupling |

| 2.1.3 | Muscle Fatigue and Damage |

| 2.1.4 | Recovery from Muscle Fatigue |

| 2.2 | Peripheral Muscle Fatigue in Disease |

| 2.2.1 | Overview |

| 2.2.2 | Old Age |

| 2.2.3 | Myopathies |

| 2.2.4 | Disturbances in Excitation-contraction Coupling |

| 2.2.5 | Neurological Diseases |

| 3 | Central Processes in Muscle Fatigue |

| 3.1 | Central Fatigue |

| 3.1.1 | Muscle Wisdom |

| 3.1.2 | Potential Mechanisms |

| 3.2 | Spinal Muscle Fatigue in Health |

| 3.2.1 | Motor Unit (MU) Properties as a First Line of Defense |

| 3.2.2 | Neuronal Sensors of Muscle Fatigue |

| 3.2.2.1 | Fatigue-related Changes in Firing of Muscle Spindle Afferents |

| 3.2.2.2 | Fatigue-related Changes in Firing of GTO Afferents |

| 3.2.2.3 | Group III/IV Muscle Afferents |

| 3.2.3 | Spinal Fatigue-related Reflexes |

| 3.2.3.1 | Presynaptic Inhibition (PSI) |

| 3.2.3.2 | Monosynaptic Group Ia Afferent Excitation |

| 3.2.3.3 | Heteronymous Group Ib Afferent Inhibition |

| 3.2.3.4 | Recurrent Inhibition |

| 3.2.3.5 | Reciprocal Inhibition |

| 3.3 | Supraspinal Muscle Fatigue |

| 3.3.1 | Fatigue-induced Effects in Supraspinal Structures |

| 3.3.1.1 | Medulla Oblongata |

| 3.3.1.2 | Peri-aqueductal Gray (PAG) |

| 3.3.1.3 | Amygdala |

| 3.3.1.4 | Blood-Pressure and Respiratory Control in Medulla and Amygdala |

| 3.3.1.5 | Hypothalamus |

| 3.3.1.6 | Cerebellum |

| 3.3.1.7 | Cerebral Cortex |

| 3.3.1.8 | Cortico-cerebello-basal ganglia-thalamic System |

| 3.3.2 | A Long Way Down: From Cerebral Cortex to Spinal Cord |

| 3.3.2.1 | Insufficient Drive from Motor Cortex |

| 3.3.2.2 | Substantia Nigra Pars Compacta and Dopamine (DA) |

| 3.3.2.3 | Raphé Nuclei and Serotonin (5-HT) |

| 3.3.2.4 | Locus Coeruleus and Noradrenaline (NA) |

| 3.4 | Central Muscle Fatigue in Disease |

| 3.4.1 | Overview |

| 3.4.2 | Age |

| 3.4.3 | Motoneuron Diseases |

| 3.4.3.1 | Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) |

| 3.4.3.2 | Spinal Muscle Atrophy (SMA) |

| 3.4.3.3 | Post-Polio Syndrome (PPS) |

| 3.4.4 | Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) |

| 3.4.5 | Stroke and spasticity |

| 3.4.6 | Parkinson’s Disease (PD) |

| 3.4.7 | Multiple Sclerosis (MS) |

| 3.4.8 | Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) |

| 3.4.9 | Fibromyalgia and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) |

| 3.4.10 | COVID-19 Neuromuscular Symptoms |

| 3.4.11 | Yawning-Fatigue Syndrome |

| 3.4.12 | Muscle Fatigue and Pain |

| 4 | Conclusions |

1. Introduction

2. Peripheral Processes in Muscle Fatigue

2.1. Peripheral Muscle Fatigue in Health

2.1.1. Metabolic Factors in Muscle Fatigue

2.1.2. Disturbances in Excitation-Contraction Coupling

2.1.3. Muscle Fatigue and Damage

2.1.4. Recovery from Muscle Fatigue

2.2. Peripheral Muscle Fatigue in Disease

2.2.1. Overview

2.2.2. Old Age

2.2.3. Myopathies

3. Central Processes in Muscle Fatigue

3.1. Central Fatigue

3.1.1. Muscle Wisdom

3.1.2. Potential Mechanisms

3.2. Spinal Muscle Fatigue in Health

3.2.1. Motor Unit (MU) Properties as a First Line of Defense

3.2.2. Neuronal Sensors of Muscle Fatigue

3.2.2.1. Fatigue-Related Changes in Firing of Muscle Spindle Afferents

3.2.2.2. Fatigue-Related Changes in Firing of GTO Afferents

3.2.2.3. Group III/IV Muscle Afferents

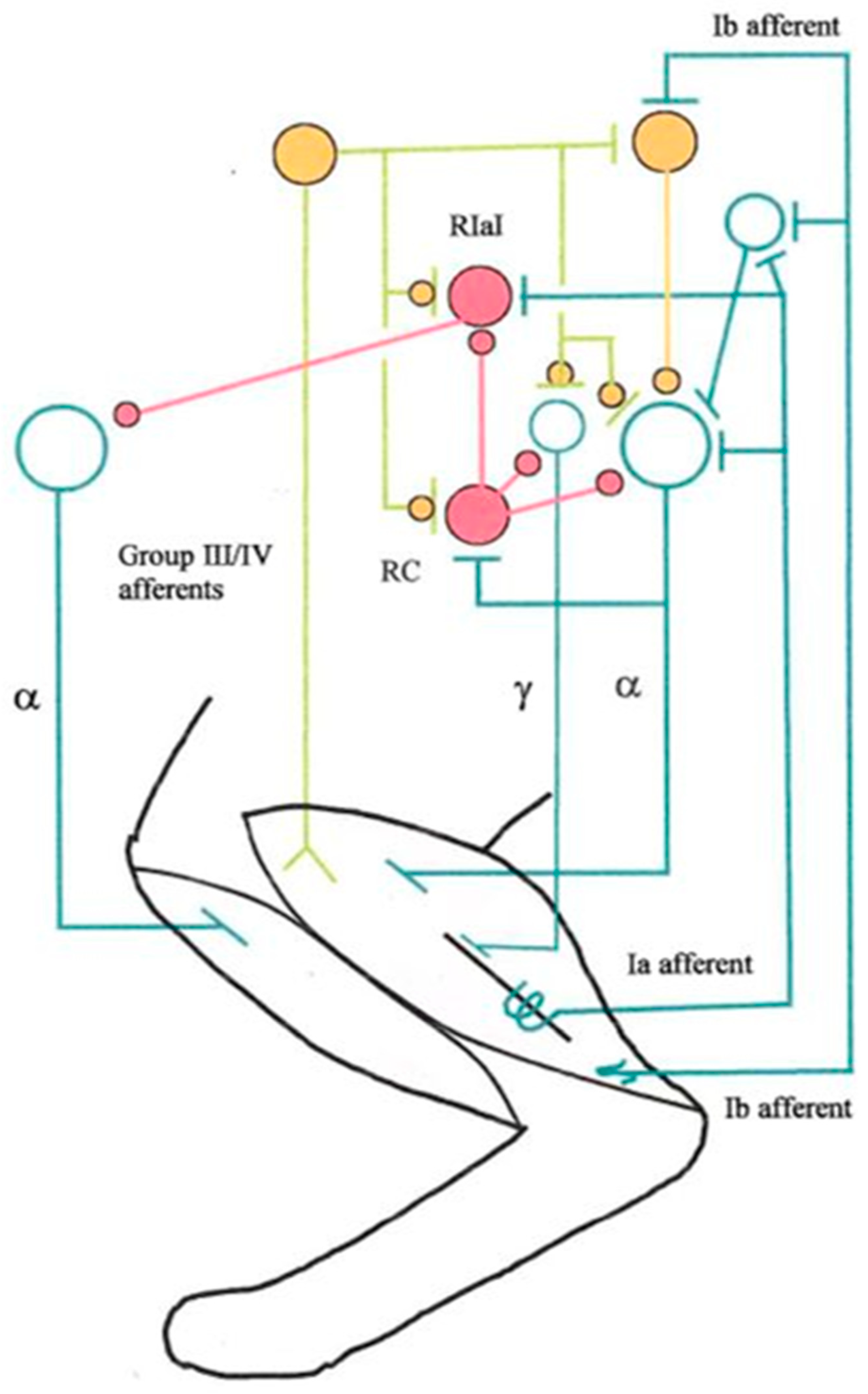

3.2.3. Spinal Fatigue-Related Reflexes

3.2.3.1. Presynaptic Inhibition (PSI)

3.2.3.2. Monosynaptic Group Ia Afferent Excitation

3.2.3.3. Heteronymous Group Ib Afferent Inhibition

3.2.3.4. Recurrent Inhibition

3.2.3.5. Reciprocal Inhibition

3.3. Supraspinal Muscle Fatigue in Health

3.3.1. Fatigue-Induced Effects in Supraspinal Structures

3.3.1.1. Medulla Oblongata

3.3.1.2. Peri-Aqueductal Gray (PAG)

3.3.1.3. Amygdala

3.3.1.4. Blood-Pressure and Respiratory Control in Medulla and Amygdala

3.3.1.5. Hypothalamus

3.3.1.6. Cerebellum

3.3.1.7. Cerebral Cortex

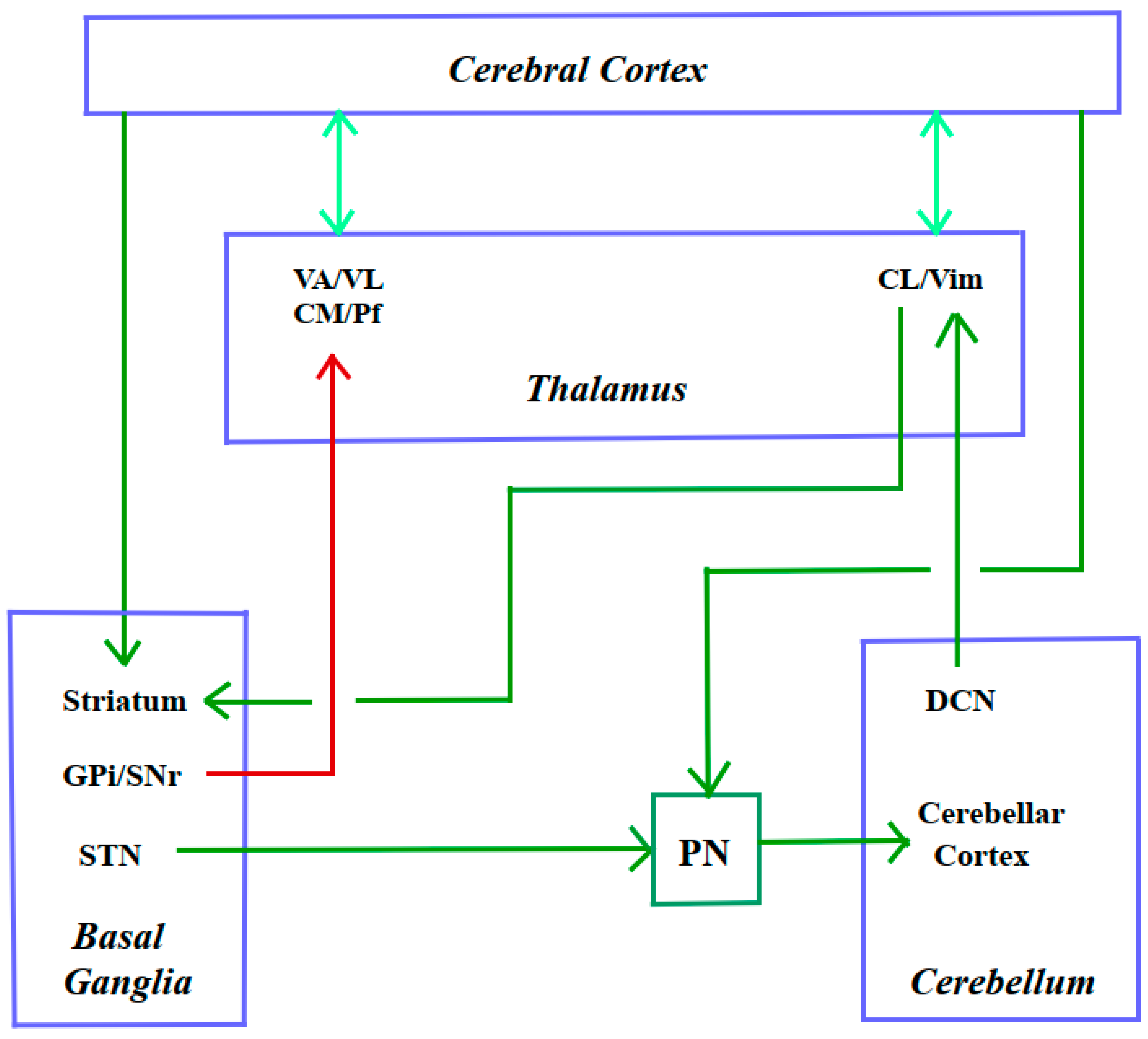

3.3.1.8. Cortico-Cerebello-Basal Ganglia-Thalamic System

3.3.2. A Long Way Down: From Cerebral Cortex to Spinal Cord

3.3.2.1. Insufficient Drive from Motor Cortex

3.3.2.2. Substantia Nigra Pars Compacta and Dopamine (DA)

3.3.2.3. Raphé Nuclei and Serotonin (5-HT)

3.3.2.4. Locus Coeruleus and Noradrenaline (NA)

3.4. Central Muscle Fatigue in Disease

3.4.1. Overview

3.4.2. Age

3.4.3. Motoneuron Diseases

3.4.3.1. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)

3.4.3.2. Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA)

3.4.3.3. Post-Polio Syndrome (PPS)

3.4.4. Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) and Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

3.4.5. Stroke and Spasticity

3.4.6. Parkinson’s Disease (PD)

3.4.7. Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

3.4.8. Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS)

3.4.9. Fibromyalgia and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS)

3.4.10. COVID-19 Neuromuscular Symptoms

3.4.11. Yawning-Fatigue Syndrome

3.4.12. Muscle Fatigue and Pain

4. Concluding Remarks

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interest

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Abbreviations

References

- Abrams RMC, Zhou L, Shin SC (2023) Persistent post-COVID-19 neuromuscular symptoms. Muscle Nerve 68(4):350-355. [CrossRef]

- Adamaszek M, D’Agata F, Ferrucci R, Habas C, Keulen S, Kirkby KC, Leggio M, Mariёn P, Molinari M, Moulton E, Orsi L, Van Overwalle F, Papadelis C, Priori A, Sacchetti L, Schutter DJ, Styliadis C, Verhoeven J (2017) Consensus Paper: Cerebellum and emotion. Cerebellum 16(2):552-576. [CrossRef]

- Allen DG (2004) Skeletal muscle function: role of ionic changes in fatigue, damage and disease. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 31(8):485-493. [CrossRef]

- Allen DG, Lamb GD, Westerblad H (2008) Skeletal muscle fatigue: cellular mechanisms. Physiol Rev 88(1):287-332. [CrossRef]

- Allen DG, Trajanovska S (2012) The multiple roles of phosphate in muscle fatigue. Front Physiol 3:463. [CrossRef]

- Allen GM, Gandevia SC, Neering IR, Hickie I, Jones R, Middleton J (1994) Muscle performance, voluntary activation and perceived effort in normal subjects and patients with prior poliomyelitis. Brain 117:661-670. [CrossRef]

- Allen HN, Bobnar HJ, Kolber BJ (2021) Left and right hemispheric lateralization of the amygdala in pain. Prog Neurobiol 196:101891. [CrossRef]

- Amann M (2012) Significance of group III and IV muscle afferents for the endurance exercising human. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 39(9):831-835. [CrossRef]

- Amann M, Blain GM, Proctor LT, Sebranek JJ, Pegelow DF, Dempsey JA (2010) Group III and IV muscle afferents contribute to ventilatory and cardiovascular response to rhythmic exercise in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 109(4):966-976. [CrossRef]

- Amann M, Sidhu SK, McNeil CJ, Gandevia SC (2022) Critical considerations of the contribution of the corticomotoneuronal pathway to central fatigue. J Physiol (Lond) 600(24):5203-5214. [CrossRef]

- Amann M, Sidhu SK, Weavil JC, Mangum TS, Venturelli M (2015) Autonomic responses to exercise: Group III/IV muscle afferents and fatigue. Auton Neurosci: Basic and Clin 188:19-233. [CrossRef]

- Amann M, Wan H-Y, Thurston TS, Georgescu VP, Weavil JC (2020) On the influence of group III/IV muscle afferent feedback on endurance exercise performance. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 48(4):209-216. [CrossRef]

- Ament W, Verkerke GJ (2009) Exercise and fatigue. Sports Med 39(5):389-422. [CrossRef]

- Andrezik JA, Chan-Palay V, Palay SL (1981) The nucleus paragigantocellularis lateralis in the rat. Demonstration of afferents by the retrograde transport of horseradish peroxidase. Anat Embryol (Berl) 161(4):373-390. [CrossRef]

- Argyelan M, Carbon M, Niethammer M, Ulug AM, Voss HU, Bressman SB, Dhawan V, Eidelberg D (2009) Cerebellothalamocortical connectivity regulates penetrance in dystonia. J Neurosci 29(31):9740-9747. [CrossRef]

- Avela J, Kyröläinen H, Komi PV, Rama D (1999) Reduced reflex sensitivity persists several days after long-lasting stretch-shortening cycle exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985) 86(4):1292-1300. [CrossRef]

- Ball D (2015) Metabolic and endocrine response to exercise: sympathoadrenal integration with skeletal muscle. J Endocrinol 224:R79-R95. [CrossRef]

- Bączyk M, Manuel M, Roselli F, Zytnicki D (2022) Diversity of mammalian motoneurons and motor units. Adv Neurobiol 28:131-150. [CrossRef]

- Bandler R, Shipley MT (1994) Columnar organization in the midbrain periaqueductal gray: modules for emotional expression? Trends Neurosci 7(9):379-389. [CrossRef]

- Bartels B, de Groot JF, Habets LE, Wadman RI, Asselman F, Nieuwenhuis EES, van Eijk RPA, Goedee HS, van der Pol WL (2021) Correlates of fatigability in patients with spinal muscular atrophy. Neurology 96(6):e845-e852. [CrossRef]

- Baudry S, Maerz AH, Gould JR, Enoka RM (2011) Task- and time-dependent modulation of Ia presynaptic inhibition during fatiguing contractions performed by humans. J Neurophysiol106(1):265-273. [CrossRef]

- Bellinger AM, Mongillo M, Marks AR (2008) Stressed out: the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor as a target of stress. J Clin Invest 118(2):445-453. [CrossRef]

- Benarroch EE (2020) Physiology and pathophysiology of the autonomic nervous system. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 26(1):12-24. [CrossRef]

- Benwell NM, Mastaglia FL, Thickbroom GW (2007) Changes in the functional MR signal in motor and non-motor areas during intermittent fatiguing hand exercise. Exp Brain Res 182(1):93-97. [CrossRef]

- Bigland-Ritchie B (1984) Muscle fatigue and the influence of changing neural drive. Clin Chest Med 5:21-34.

- Bigland-Ritchie B, Woods JJ (1984) Changes in muscle contractile properties and neural control during human muscular fatigue. Muscle Nerve 7(9):691-699. [CrossRef]

- Binder MD, Kroin JS, Moore GP, Stauffer EK, Stuart DG (1976) Correlation analysis of muscle spindle responses to single motor unit contractions. J Physiol 257(2):325-336. [CrossRef]

- Binder MD, Kroin JS, Moore GP, Stuart DG (1977) The response of Golgi tendon organs to single motor unit contractions. J Physiol 271(2):337-349. [CrossRef]

- Bostan AC, Strick PL (2018) The basal ganglia and the cerebellum nodes in an integrated network. Nat Rev Neurosci 19:338-350. [CrossRef]

- Brodal A (1981) Neurological anatomy. In relation to clinical medicine, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Brownstein CG, Millet GY, Thomas K (2021) Neuromuscular responses to fatiguing locomotor exercise. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 231(2):e13533. [CrossRef]

- Brunetti O, Della Torre G, Lucchi ML, Chiocchetti R, Bortolami R, Pettorossi VE (2003) Inhibition of muscle spindle afferent activity during masseter muscle fatigue in the rat. Exp Brain Res 152(2):251-262. [CrossRef]

- Burke RE (2009) Motor units. In: Binder MD, Hirokawa N, Windhorst U (eds) Encyclopedia of neuroscience. Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg, pp 2443-2446.

- Byrne C, Twist C, Eston R (2004) Neuromuscular function after exercise-induced muscle damage: theoretical and applied implications. Sports Med 34(1):49-69. [CrossRef]

- Cairns SP (2006) Lactic acid and exercise performance: culprit or friend? Sports Med 36(4):279-291. [CrossRef]

- Caligiori D, Pezzulo G, Baldassare G, Bostan AC, Strick PL, Doya K, Helmich RC, Dirkx M, Houk J, Jörntell H, Lago-Rodriguez A, Galea JM, Miall RC, Popa R, Kishore A, Verschure PFMJ, Zucca R, Herreros I (2017) Consensus paper: towards a systems-level view of cerebellar function: the interplay between cerebellum, basal ganglia, and cortex. Cerebellum 16(1): 203–229. [CrossRef]

- Cantor F (2010) Central and peripheral fatigue: exemplified by multiple sclerosis and myasthenia gravis. PM R 2(5):399-405. [CrossRef]

- Carroll TJ, Taylor JL, Gandevia SC (2017) Recovery of central and peripheral neuromuscular fatigue after exercise. J Appl Physiol 122:1068-1076. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri A, Behan PO (2000) Fatigue and basal ganglia. J Neurol Sci 179:34–42. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri A, Behan PO (2004) Fatigue in neurological disorders. Lancet 363(9413):978-988. [CrossRef]

- Cheng AJ, Jude B, Lanner JT (2020) Intramuscular mechanisms of overtraining. Redox Biol 35:101480. [CrossRef]

- Cheng AJ, Place N, Westerblad H (2018) Molecular basis for exercise-induced fatigue: the importance of strictly controlled cellular Ca2+ handling. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018 Feb 1;8(2):a029710. [CrossRef]

- Cheng AJ,Yamada T, Rassier DE, Andersson DC, Westerblad H, Lanner JT (2016) Reactive oxygen/nitrogen species and contractile function in skeletal muscle during fatigue and recovery. J Physiol 594(18):5149-5160. [CrossRef]

- Chiang C, Aston-Jones G (1993) Response of locus coeruleus neurons to foot shock stimulation is mediated by neurons in the rostral ventral medulla. Neuroscience 53(3):705-715. [CrossRef]

- Christakos CN, Windhorst U (1986) Spindle gain increase during muscle unit fatigue. Brain Res 365(2):388-392. [CrossRef]

- Clarkson PM, Hubal MJ (2002) Exercise-induced muscle damage in humans. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 81(11 Suppl):S52-69. [CrossRef]

- Clarkson PM, Newham DJ (1995) Associations between muscle soreness, damage, and fatigue. Adv Exp Med Biol 384:457-469. [CrossRef]

- Coletti C, Acosta GF, Keslacy S, Coletti D (2022) Exercise-mediated reinnervation of skeletal muscle in elderly people: An update. Eur J Transl Myol 32(1):10416. [CrossRef]

- Constantin-Teodosiu D, Constantin D (2021) Molecular mechanisms of muscle fatigue. Int J Mol Sci 22(21):11587. [CrossRef]

- Costa Silva C, Carneiro Bichara CN, Carneiro FRO, da Cunha Menezes Palacios VR, Van den Berg AVS, Quaresma JAS, Falcão LFM (2022) Muscle dysfunction in the long coronavirus disease 2019 syndrome: Pathogenesis and clinical approach. Rev Med Virol 32(6):e2355. [CrossRef]

- Cotel F, Exley R, Cragg SJ, Perrier J-F (2013) Serotonin spillover onto the axon initial segment of motoneurons induces central fatigue by inhibiting action potential initiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110(12):4774-4779. [CrossRef]

- Crisafulli O, Berardinelli A, D'Antona G (2024) Fatigue in spinal muscular atrophy: a fundamental open issue. Acta Myol 43(1):1-7. [CrossRef]

- Crook H, Raza S, Nowell J, Young M, Edison P (2021) Long covid-mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ 2021 374:n1648. [CrossRef]

- Cuadra C, De Boef A, Luong S, Wolf SL, Nichols TR, Lyle MA (2024) Reduced inhibition from quadriceps onto soleus after acute quadriceps fatigue suggests Golgi tendon organ contribution to heteronymous inhibition. Eur J Neurosci 60(3):4317-4331. [CrossRef]

- Debold EP (2015) Potential molecular mechanisms underlying muscle fatigue mediated by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Front Physiol 6:239. [CrossRef]

- Debold EP, Fitts RH, Sundberg CW, Nosek TM (2016) Muscle fatigue from the perspective of a single crossbridge. Med Sci Sports Exerc 48:2270-2280. [CrossRef]

- Decherchi P, Dousset E (2003) Le rôle joué par les fibres afférentes métabosensibles dans les mécanismes adaptifs neuromusculaires. Can J Neurol Sci 30:91-97. [CrossRef]

- Dettmers C, Lemon RN, Stephan KM, Fink GR, Frackowiak RS (1996) Cerebral activation during the exertion of sustained static force in man. Neuroreport 7(13):2103-2110 . [CrossRef]

- Dibaj P, Brockmann K, Gärtner J (2020) Dopamine-mediated yawning-fatigue syndrome with specific recurrent initiation and responsiveness to opioids. JAMA Neurol 77(2):254. [CrossRef]

- Dibaj P, Seeger D, Gärtner J, Petzke F (2021) Follow-up of a case of dopamine-mediated yawning-fatigue-syndrome responsive to opioids, successful desensitization via graded activity treatment. Neurol Int 13(1):79-84. [CrossRef]

- Dibaj P, Windhorst U (2024) Motor-control notions in health and disease (what controls motor control?). Preprints 2024, 2024031799. [CrossRef]

- Enoka RM, Duchateau J (2008) Muscle fatigue: what, why and how it influences muscle function. J Physiol 586(1):11-23. [CrossRef]

- Esposito F, Ce E, Rampichini S, Monti E, Limonta E, Fossati B, Meola G (2017) Electromechanical delays during a fatiguing exercise and recovery in patients with myotonic dystrophy type 1. Eur J Appl Physiol 117:551-566. [CrossRef]

- Finsterer J, Mahjoub SZ (2014) Fatigue in healthy and diseased individuals. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 31(5):562-755. [CrossRef]

- Fitts RH (1994) Cellular mechanisms of muscle fatigue. Physiol Rev 74:49-94. [CrossRef]

- Fitts RH (2008) The cross-bridge cycle and skeletal muscle fatigue. J Appl Physiol 104:551-558. [CrossRef]

- Foley TE, Fleshner M (2008) Neuroplasticity of dopamine circuits after exercise: implications for central fatigue. Neuromolecular Med 10(2):67-80. [CrossRef]

- Fornal CA, Martin-Cora FJ, Jacobs BL (2006) "Fatigue" of medullary but not mesencephalic raphe serotonergic neurons during locomotion in cats. Brain Res 1072(1):55-61. [CrossRef]

- Gandevia SC (2001) Spinal and supraspinal factors in human muscle fatigue. Physiol Rev 81:1725-1789. [CrossRef]

- Garland SJ, McComas AJ (1990) Reflex inhibition of human soleus muscle during fatigue. J Physiol 429:17-27. [CrossRef]

- Granger MW, Buschang PH, Throckmorton GS, Iannaccone ST (1999) Masticatory muscle function in patients with spinal muscular atrophy. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 115(6):697-702. [CrossRef]

- Garssen MPJ, Schillings ML, van Doorn PA, van Engelen BGM, Zwarts MJ (2007) Contribution of central and peripheral factors to residual fatigue in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Muscle Nerve 36(1):93-99. [CrossRef]

- Gottschalk, M, Kümpfel T, Flachenecker P, Uhr M, Trenkwalder C, Holsboer F, Weber F (2005) Fatigue and regulation of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 62(2):277–280. [CrossRef]

- Green HJ (1997) Mechanisms of muscle fatigue in intense exercise. J Sports Sci 15(3):247-562. [CrossRef]

- Gregory JE, Morgan DL, Proske U (2003) Tendon organs as monitors of muscle damage from eccentric contractions. Exp Brain Res 151:346-355. [CrossRef]

- Grosprêtre S, Gueugneau N, Martin A, Lepers R (2018) Presynaptic inhibition mechanisms may subserve the spinal excitability modulation induced by neuromuscular electrical stimulation. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 40:95-101. [CrossRef]

- Gruet M, Temesi J, Rupp T, Lev P, Millet GY. Verges S (2013) Stimulation of the motor cortex and corticospinal tract to assess human muscle fatigue. Neuroscience 12:231:384-399. [CrossRef]

- Hall MM, Rajasekaran S, Thomsen TW, Peterson AR (2016) Lactate: Friend or Foe. PM R 8(3 Suppl):S8-S15. [CrossRef]

- Hayward L, Breitbach D, Rymer WZ (1988) Increased inhibitory effects on close synergists during muscle fatigue in the decerebrate cat. Brain Res 440(1):199-203. [CrossRef]

- Hayward L, Wesselmann U, Rymer WZ (1991) Effects of muscle fatigue on mechanically sensitive afferents of slow conduction velocity in the cat triceps surae. J Neurophysiol 65:360-370. [CrossRef]

- Heesen, C, Nawrath L, Reich C, Bauer N, Schulz K, Gold SM (2006) Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: an example of cytokine mediated sickness behaviour? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 77(1):34–39. [CrossRef]

- Helbostad JL, Sturnieks DL, Menant J, Delbaere K, Lord SR, Pijnappels M (2010) Consequences of lower extremity and trunk muscle fatigue on balance and functional tasks in older people: a systematic literature review. BMC Geriatr 17:10:56. [CrossRef]

- Henderson TT, Taylor JL, Thorstensen JR, Tucker MG, Kavanagh JJ (2022) Enhanced availability of serotonin limits muscle activation during high-intensity, but not low-intensity, fatiguing contractions. J Neurophysiol 128(4):751-762. [CrossRef]

- Hilty L, Lutz K, Maurer K, Rodenkirch T, Spengler CM, Boutellier U, Jäncke L, Amann M (2011) Spinal opioid receptor-sensitive muscle afferents contribute to the fatigue-induced increase in intracortical inhibition in healthy humans. Exp Physiol 96(5):505-517. [CrossRef]

- Hou LJ, Song Z, Pan ZJ, Cheng JL, Yu Y, Wang J (2016) Decreased activation of subcortical brain areas in the motor fatigue state: An fMRI study. Front Psychol 7:1154. [CrossRef]

- Hsiao Y, Elliot TR, Jaramillo J, Douglas ME, Powers MB, Warren AM (2024) The fatigue and altered cognition scale among SARS-CoV-2 survivors: psychometric properties and item correlations with depression and anxiety symptoms. J Clin Med 13(8):2186. [CrossRef]

- Hunter SK, Pereira HM, Keenan KG (2016) The aging neuromuscular system and motor performance. J Appl Physiol (1985) 121(4):982-995. [CrossRef]

- Hureau TJ, Romer LM, Amann M (2018) The 'sensory tolerance limit': A hypothetical construct determining exercise performance? Eur J Sport Sci 18(1):13-24. [CrossRef]

- Hutton RS, Nelson DL (1986) Stretch sensitivity of Golgi tendon organs in fatigued gastrocnemius muscle. Med Sci Sports Exerc 18(1):69-74.

- Jankowska E (1992) Interneuronal relay in spinal pathways from proprioceptors. Prog Neurobiol 38:335-378. [CrossRef]

- Jankowska E, Edgley SE (2010) Functional subdivision of feline spinal interneurons in reflex pathways from group Ib and II muscle afferents; an update. Eur J Neurosci 32: 881-893. [CrossRef]

- Jiang Z, Wang X-F, Yue GH (2016) Strengthened corticosubcortical functional connectivity during muscle fatigue. Neural Plast 2016:1726848. [CrossRef]

- Jones DA (1993) How far can experiments in the laboratory explain the fatigue of athletes in the field? In: Sargeant AJ, Kernell D (eds) Neuromuscular fatigue. Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, Amsterdam, pp 100-108.

- Kalezic I, Bugaychenko LA, Kostyukov AI, PilyavskiiAI, Ljubisavljevid M, Windhorst U, Johansson H (2004) Fatigue-related depression of the feline monosynaptic gastrocnemius-soleus reflex. J Physiol 556(Pt 1):283-296. [CrossRef]

- Kalezic I, Steffens H (2013) Changes in tetrodotoxin-resistant C-fibre activity during fatiguing isometric contractions in the rat.PLoS One 8(9):e73980. [CrossRef]

- Katz R, Meunier S, Pierrot-Deseilligny E (1988) Changes in presynaptic inhibition of Ia fibres in man while standing. Brain 111:417-437. [CrossRef]

- Katz R, Pierrot-Deseilligny E (1999) Recurrent inhibition in humans. Prog Neurobiol 57:325-355. [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh JJ, Taylor JL (2022) Voluntary activation of muscle in humans: does serotonergic neuromodulation matter? J Physiol 600(16):3657-3670. [CrossRef]

- Keller J, Zackowski K, Kim S, Chidobem I, Smith M, Farhardi F, Bhargava P (2021) Exercise leads to metabolic changes associated with imprived strength and fatigue in people with MS. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 8(6):1308-1317. [CrossRef]

- Kent JA,, Ørtenblad N, Hogan MC, Poole DC, Musch TI (2016) No muscle is an island: Integrative perspectives on muscle fatigue. Med Sci Sports Exerc 48(11):2281-2293. [CrossRef]

- Kent-Braun JA, Fitts RH, Christie A (2012) Skeletal muscle fatigue. Compr Physiol 2:997-1044. [CrossRef]

- Kent-Braun JA, Miller RG (2000) Central fatigue during isometric exercise in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 23:909-914. [CrossRef]

- Kent-Braun JA, Sharma KR, Weiner MW, Massie B, Miller RG (1993) Central basis of fatigue in chronic fatigue syndrome. Neurology 43(1):125-131. [CrossRef]

- Kernell D, Monster AW (1982) Motoneurone properties and motor fatigue. An intracellular study of gastrocnemius motoneurones of the cat. Exp Brain Res 46:197-204. [CrossRef]

- Klass M, Duchateau J, Rabec S, Meeusen R, Roelands B (2016) Noradrenaline reuptake inhibition impairs cortical output and limits endurance time. Med Sci Sports Exerc 48(6):1014-1023. [CrossRef]

- Klass M, Roelands B, Lévénez M, Fontenelle V, Pattyn N, Meeusen R, Duchateau J (2012) Effects of noradrenaline and dopamine on supraspinal fatigue in well-trained men. Med Sci Sports Exerc 44(12):2299-2308. [CrossRef]

- Knorr S, Rice CL, Garland SJ (2012) Perspective on neuromuscular factors in poststroke fatigue. Disabil Rehabil 34(26):2291-2299. [CrossRef]

- Koehler W, Hamm TM, Enoka RM, Stuart DG, Windhorst U (1984) Contractions of single motor units are reflected in membrane potential changes of homonymous alpha-motoneurons. Brain Res 296(2):379-834. [CrossRef]

- Kostyukov AI, Bugaychenko LA, Kalezic I, Pilyavskii AI, Windhorst U, Djupsjöbacka M (2005) Effects in feline gastrocnemius-soleus motoneurones induced by muscle fatigue. Exp Brain Res 163(3):284-294. [CrossRef]

- Kostyukov AI, Kalezic I, Serenko SG, Ljubisavljevic M, Windhorst U, Johansson H (2002) Spreading of fatigue-related effects from active to inactive parts in the medial gastrocnemius muscle of the cat. Eur J Appl Physiol 86:295-307. [CrossRef]

- Koutsikou S, Apps R, Lumb BM (2017) Top-down control of spinal sensorimotor circuits essential for survival. J Physiol (Lond) 595(13):4151-4158. [CrossRef]

- Kuchinad RA, Ivanova TD, Garland SJ (2004) Modulation of motor unit discharge rate and H-reflex amplitude during submaximal fatigue of the human soleus muscle. Exp Brain Res 158(3):345-355. [CrossRef]

- Kuner R, Kuner T (2021) Cellular circuits in the brain and their modulation in acute and chronic pain. Physiol Rev 101(1):213-258. [CrossRef]

- Lännergren J, Westerblad H, Allen DG (1993) Mechanisms of fatigue as studied in single muscle fibres. In: Sargeant AJ, Kernell D (eds) Neuromuscular fatigue. Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, Amsterdam, pp 3-11.

- Lalley PM (2009 Respiration – neural control. In: Binder MD, Hirokawa N, Windhorst U (eds) Encyclopedia of neuroscience. Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg, pp 3433-3441.

- Lamotte G, Shouman K, Benarroch EE (2021) Stress and central autonomic network. Auton Neurosci 235:102870. [CrossRef]

- Laurin J, Pertici V, Doucet E, Marqueste T, Decherchi P (2015) Group III and IV muscle afferents: role on central motor drive and clinical implications. Neuroscience 290:543-551. [CrossRef]

- Lenman AJ, Tulley FM, Vrbova G, Dimitrijevic MR, Towle J (1989) Muscle fatigue in some neurological disorders. Muscle Nerve 12(11):938-942. [CrossRef]

- Lin K, Chen Y, Luh J, Wang C, Chang Y (2012) H-reflex, muscle voluntary activation level, and fatigue index of flexor carpi radialis in individuals with incomplete cervical cord injury. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair 26(1):68–75. [CrossRef]

- Lindinger MI, Cairns SP (2021) Regulation of muscle potassium: exercise performance, fatigue and health implications. Eur J Appl Physiol 121(3):721-748. [CrossRef]

- Liu JZ, Shan ZY, Zhang LD, Sahgal V, Brown RW, Yue GH (2003) Human brain activation during sustained and intermittent submaximal fatigue muscle contractions: an FMRI study. J Neurophysiol 90(1):300-312. [CrossRef]

- Lou JS, Benice T, Kearns G, Sexton G, Nutt J (2003) Levodopa normalizes exercise related cortico-motoneuron excitability abnormalities in Parkinson’s disease. Clin Neurophysiol 114(5):930–937. [CrossRef]

- Macefield G, Hagbarth KE, Gorman R, Gandevia SC, Burke D (1991) Decline in spindle support to alpha-motoneurones during sustained voluntary contractions. J Physiol (Lond) 440:497-512. [CrossRef]

- Maisky VA, Pilyavskii AI , Kalezic I, Ljubisavljevid M, Kostyukov AI, Windhorst U, Johansson H (2002) NADPH-diaphorase activity and c-fos expression in medullary neurons after fatiguing stimulation of hindlimb muscles in the rat. Auton Neurosci 101(1-2):1-12. [CrossRef]

- Malekzadeh A, Bader I, van Dieteren J, Heijboer AC, Beckerman H, Twisk JWR, de Groot V, Teunissen CE (2020) Diurnal cortisol secretion is not related to multiple sclerosis-related fatigue. Front Neurol 10:1363. [CrossRef]

- Martin A, Freyssenet D (2021) Phenotypic features of cancer cachexia-related loss of skeletal muscle mass and function: lessons from human and animal studies.J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 12(2):252-273. [CrossRef]

- Mastaglia FL (2012) The relationship between muscle pain and fatigue. Neuromuscul Disord 22 Suppl 3:S178-180. [CrossRef]

- Maznychenko AV, Pilyavskii AI, Kostyukov AI, Lyskov E, Vlasenko OV, Maisky VA (2007) Coupling of c-fos expression in the spinal cord and amygdala induced by dorsal neck muscles fatigue. Histochem Cell Biol 28(1):85-90. [CrossRef]

- McCloskey DI, Prochazka A (1994) The role of sensory information in the guidance of voluntary movement. Somatosens Mot Res 11:21-37. [CrossRef]

- McCrimmon DR, Alheid GF (2009) Respiratory reflexes. In: Binder MD, Hirokawa N, Windhorst U (eds) Encyclopedia of neuroscience. Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg, pp 3474-3480. [CrossRef]

- McKenna MJ, Bangsbo J, Renaud JM (2008) Muscle K+, Na+, and Cl- disturbances and Na+- K+ pump inactivation; implications for fatigue. J Appl Physiol 104:288-295. [CrossRef]

- Meacci E, Pierucci F, Garcia-Gil M (2022) Skeletal muscle and COVID-19: The potential involvement of bioactive sphingolipids. Biomedicines 10(5):1068. [CrossRef]

- Meeusen R, Roelands B (2018) Fatigue: Is it all neurochemistry? Eur J Sport Sci 18(1):37-46. [CrossRef]

- Mense S (1993) Nociception from skeletal muscle in relation to clinical muscle pain. Pain 54(3):241-289. [CrossRef]

- Miller RG, Green AT, Moussavi RS, Carson PJ, Weiner MW (1990) Excessive muscular fatigue in patients with spastic paraparesis. Neurology 40(8):1271-1274. [CrossRef]

- Mills EP, Keay KA, Henderson LA (2021) Brainstem pain-modulation circuitry and its plasticity in neuropathic pain: Insights from human brain imaging investigations. Front Pain Res (Lausanne) 2:705345. [CrossRef]

- Montes J, McDermott MP, Martens WB, Dunaway S, Glanzman AM, Riley S, Quigley J, Montgomery MJ, Sproule D, Tawil R, Chung WK, Darras BT, De Vivo DC, Kaufmann P, Finkel RS; Muscle study group and the pediatric neuromuscular clinical research network (2010) Six-Minute Walk Test demonstrates motor fatigue in spinal muscular atrophy. Neurology 74(10):833-838. [CrossRef]

- Mossberg K, Masel B, Gilkison C, Urban R (2008) Aerobic capacity and growth hormone deficiency after traumatic brain injury. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:2581–2587. [CrossRef]

- Nardone R, Buffone E, Florio I, Tezzon F (2005) Changes in motor cortex excitability during muscle fatigue in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 76:429–31. [CrossRef]

- Nardone A, Schieppati M (2004) Group II spindle fibres and afferent control of stance. Clues from diabetic neuropathy. Clin Neurophysiol 115:779-789. [CrossRef]

- Noonan TJ, Garrett WE (1999) Muscle strain injury: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 7(4):262-269. [CrossRef]

- Olave MJ, Puri N, Kerr R, Maxwell DJ (2002) Myelinated and unmyelinated primary afferent axons form contacts with cholinergic interneurons in the spinal dorsal horn. Exp Brain Res 45(4):448-456. [CrossRef]

- Ortelli P, Ferrazzoli D, Sebastianelli L, Engl M, Romanello R, Nardone R, Bonini I, Koch G, Saltuari L, Quartarone A, Oliviero A, Kofler M, Versace V (2021) Neuropsychological and neurophysiological correlates of fatigue in post-acute patients with neurological manifestations of COVID-19: Insights into a challenging symptom. J Neurol Sci 420:117271. [CrossRef]

- Ørtenblad N, Westerblad H, Nielsen J (2013) Muscle glycogen stores and fatigue. J Physiol (Lond) 591:4405-4413. [CrossRef]

- Papa EV, Garg H, Dibble LE (2015) Acute effects of muscle fatigue on anticipatory and reactive postural control in older individuals: a systematic review of the evidence. J Geriatr Phys Ther 38(1):40-48. [CrossRef]

- Pearson AM, Young RB (1993) Diseases and disorders of muscle. Adv Food Nutr Res 37:339-423. [CrossRef]

- Penner I, Paul F (2017) Fatigue as a symptom or comorbidity of neurological diseases. Nat Rev Neurol 13(11):662-675. [CrossRef]

- Pescaru CC, Mariţescu A, Costin EO, Trăilă D, Marc MS, Truşculescu AA, Pescaru A, Oancea CI (2022) The effects of COVID-19 on skeletal muscles, muscle fatigue and rehabilitation programs outcomes. Medicina (Kaunas) 58(9):1199. [CrossRef]

- Pilyavskii AI. Maisky VA, Kalezic I, Ljubisavljevic M, Kostyukov AI, Windhorst U, Johansson H (2001) C-fos expression and NADPH–d reactivity in spinal neurons after fatiguing stimulation of hindlimb muscles in the rat. Brain Research 293: 91-102. [CrossRef]

- Ponchel A, Bombois S, Bordet R, Hénon H (2015) Factors associated with poststroke fatigue: a systematic review. Stroke Res Treat 2015:347920. [CrossRef]

- Powers SK, Deminice R, Ozdemir M, Yoshihara T, Bomkamp MP, Hyatt H (2020) Exercise-induced oxidative stress: Friend or foe? J Sport Health Sci 9(5):415-425. [CrossRef]

- Powers SK, Jackson MJ (2008) Exercise-induced oxidative stress: cellular mechanisms and impact on muscle force production. Physiol Rev 88:1243-1276. [CrossRef]

- Powers SK, Lynch GS, Murphy KT, Reid MB, Zijdewind I (2016) Disease-induced skeletal muscle atrophy and fatigue. Med Sci Sports Exerc 48(11):2307-2319. [CrossRef]

- Proske U (2019) Exercise, fatigue and proprioception: a retrospective. Exp Brain Res 237(10):2447-2459. [CrossRef]

- Quevedo JN (2009) Presynaptic inhibition. In: Binder MD, Hirokawa N, Windhorst U (eds) Encyclopedia of neuroscience. Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg, pp 3266-3270.

- Ramazzini B (1713) De morbis artificum diatriba. In: Diseases of workers. New York Academy of Medicine, History of Medicine Series (1964) Hafner, N.Y.

- Ranieri F, Di Lazzaro V (2012) The role of motor neuron drive in muscle fatigue. Neuromuscul Disord 22 Suppl 3:S157-161. [CrossRef]

- Rayhan RU, Baraniuk JN (2021) Submaximal exercise provokes increased activation of the anterior default mode network during the resting state as a biomarker of postexertional malaise in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Front Neurosci 15:748426. [CrossRef]

- Renaud J-M, Ørtenblad N, McKenna MJ, Overgaard K (2023) Exercise and fatigue: integrating the role of K+, Na+ and Cl- in the regulation of sarcolemmal excitability of skeletal muscle. Eur J Appl Physiol 123(11):2345-2378. [CrossRef]

- Richter DM, Smith JC (2014) Respiratory rhythm generation in vivo. Physiology (Bethesda) 29(1):58-71. [CrossRef]

- Roelcke U, Kappos L, Lechner-Scott J, Brunnschweiler H, Huber S, Ammann W, Plohmann A, Dellas S, Maguire RP, Missimer J, Radü EW, Steck A, Leenders KL (1997) Reduced glucose metabolism in the frontal cortex and basal ganglia of multiple sclerosis patients with fatigue: a 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography study. Neurology 48(6):1566-1571. [CrossRef]

- Rosa EF, Alves GA, Luz J, Silva SMA, Suchecki D, Pesquero JB, Aboulafia J, Nouailhetas VLA (2014) Activation of HPA axis and remodeling of body chemical composition in response to an intense and exhaustive exercise in C57BL/6 mice. Physiol Res 63(5):605-613. [CrossRef]

- Rossi A, Mazzocchio R, Decchi B (2003) Effect of chemically activated fine muscle afferents on spinal recurrent inhibition in humans. Clin Neurophysiol 114(2):279-287. [CrossRef]

- Rotto DM, Kaufmann MP (1988) Effect of metabolic products of muscular contraction on discharge of group III and IV afferents. J Appl Physiol 64:2306-2313. [CrossRef]

- Rudomin P (2009) In search of lost presynaptic inhibition. Exp Brain Res 196:139-151. [CrossRef]

- Rudomin P, Schmidt RF (1999) Presynaptic inhibition in the vertebrate spinal cord revisited. Exp Brain Res 129:1-37. [CrossRef]

- Sato T, Tsuboi T, Miyazaki M, Sakamoto K (1999) Post-tetanic potentiation of reciprocal Ia inhibition in human lower limb. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 9(1):59-66. [CrossRef]

- Schillings ML, Kalkman JS, van der Werf SP, van Engelen BGM, Bleijenberg G, Zwarts MJ (2004) Diminished central activation during maximal voluntary contraction in chronic fatigue syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol 115(11):2518-2524. [CrossRef]

- Schirinzi E, Ricci G, Torri F, Mancuso M, Siciliano G (2023) Biomolecules of muscle fatigue in metabolic myopathies: Biomolecules 14(1):50. [CrossRef]

- Schomburg ED (1990) Spinal sensorimotor systems and their supraspinal control. Neurosci Res 7: 265-340. [CrossRef]

- Schwestka R, Windhorst U, Schaumberg R (1981) Patterns of parallel signal transmission between multiple alpha efferents and multiple Ia afferents in the cat semitendinosus muscle. Exp Brain Res 43(1):34-46. [CrossRef]

- Semmler JG (2014) Motor unit activity after eccentric exercise and muscle damage in humans. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 210(4):754-767. [CrossRef]

- Sepulcre J, Masdeu JC, Goñi J, Arrondo G, Vélez de Mendizábal N, Bejarano B, Villoslada P (2009) Fatigue in multiple sclerosis is associated with the disruption of frontal and parietal pathways. Mult Scler 15(3):337-344. [CrossRef]

- Shepherd GMG, Yamawaki N (2021) Untangling the cortico-thalamo-cortical loop: cellular pieces of a knotty circuit puzzle. Nat Rev Neurosci 22(7):389-406. [CrossRef]

- Sidhu SK, Weavil JC, Thurston TS, Rosenberger D, Jessop JE, Wang E, Richardson RS, McNeil CJ, Amann M (2018) Fatigue-related group III/IV muscle afferent feedback facilitates intracortical inhibition during locomotor exercise. J Physiol 596(19):4789-4801. [CrossRef]

- Storti SF, Formaggio E, Motetto D, Bertoldo A, Pizzini FB, Beltramello A, Fiaschi A, Toffolo GM, Manganoptti P (2014) Effect of voluntary repetitive long-lasting muscle contraction activity on the BOLD signal as assessed by optimal hemodynamic response function. MAGMA 27(2):171-184. [CrossRef]

- Sved AF, Ito S, Madden CJ (2000) Baroreflex dependent and independent roles of the caudal ventrolateral medulla in cardiovascular regulation. Brain Res Bull 51(2):129-133. [CrossRef]

- Takayanagi Y, Onaka T (2021) Roles of oxytocin in stress responses, allostasis and resilience. Int J Mol Sci ;23(1):150. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka M, Watanace Y (2012) Supraspinal regulation of physical fatigue. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 36(1):727-734. [CrossRef]

- Tanino Y, Daikuya S, Nishimori T, Takasaki K, Kanei K, Suzuki T (2004) H-reflex and reciprocal Ia inhibition after fatiguing isometric voluntary contraction in soleus muscle. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol 44(8):473-476.

- Taylor JL, Amann M, Duchateau J, Meeusen R, Rice CL (2016) Neural contributions to muscle fatigue: from the brain to the muscle and back again. Med Sci Sports Exerc 48:2294-2306. [CrossRef]

- Tsukioka K, Yamanaka K, Waki H (2022) Implication of the central nucleus of the amygdala in cardiovascular regulation and limiting maximum exercise performance during high-intensity exercise in rats. Neuroscience 496:52-63. [CrossRef]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Pieribone VA, Aston-Jones G (1989) Diverse afferents converge on the nucleus paragigantocellularis in the rat ventrolateral medulla: retrograde and anterograde tracing studies. J Comp Neurol 290(4):561-584. [CrossRef]

- Van Duinen H, Renken R, Maurits N, Zijdewind I (2007) Effects of motor fatigue on human brain activity, an fMRI study. Neuroimage 35(4):1438-1449. [CrossRef]

- Vlasenko OV, Maĭs'kyĭ VO, Maznychenko AV, Piliavs'kyĭ OI, Moroz VM (1994) [Investigation of c-fos expression and NADPH-diaphorase activity in the spine cord and brain in the development of the neck muscle weakness in rats]. Fiziol Zh (1994) 2006;52(6):3-14 [Article in Ukrainian].

- Vucic S, Cheah BC, Kiernan MC (2011) Maladaptation of cortical circuits underlies fatigue and weakness in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 12:414–20. [CrossRef]

- Wang M, Tutt JO, Dorricott NO, Parker KL, Russo AF, Sowers LP (2022) Involvement of the cerebellum in migraine. Front Syst Neurosci 16: 984406. [CrossRef]

- Weavil JC, Amann M (2018) Corticospinal excitability during fatiguing whole body exercise. Prog Brain Res 219-246. [CrossRef]

- Wichmann T, DeLong MR (2016) Deep brain stimulation for movement disorders of basal ganglia origin: restoring function or functionality? Neurotherapeutics 13(2):264-283. [CrossRef]

- Williams CA, Fowler WL (1997) Substance P released in the rostral brainstem of cats interacts with NK-1 receptors during muscle pressor response. Neuropeptides 31(6):589-600. [CrossRef]

- Williams CA, Gopalan R, Nichols PL, Brien PL (1995) Fatiguing isometric contraction of hind-limb muscles results in the release of immunoreactive neurokinins from sites in the rostral medulla in the anesthetized cat. Neuropeptides 28(4):209-218. [CrossRef]

- Williams CA, Holtsclaw LI, ChivertonJA (1992) Release of immunoreactive enkephalinergic substances in the periaqueductal grey of the cat during fatiguing isometric contractions. Neurosci Lett 139(1):19-23. [CrossRef]

- Williams CA, Roberts JR, Freels DB (1990) Changes in blood pressure during isometric contractions to fatigue in the cat after brain stem lesions: effects of clonidine. Cardiovasc Res . 1990 24(10):821-833. [CrossRef]

- Williams JH, Klug GA (1995) Calcium exchange hypothesis of skeletal muscle fatigue: a brief review. Muscle Nerve 18(4):421-344. [CrossRef]

- Windhorst U (2003) Short-term effects of group III-IV muscle afferent nerve fibers on bias and gain of spinal neurons. In: Johansson H, Windhorst U, Djupsjöbacka M, Passatore M (eds) Neuromuscular mechanisms behind work -related chronic muscle pain syndromes, Gävle University Press, Gävle Sweden.

- Windhorst U (2007) Muscle proprioceptive feedback and spinal networks. Brain Res Bull 73:155-202. [CrossRef]

- Windhorst U (2021) Spinal cord circuits: models and reality. Neurophysiology 53(3-6):142-222. [CrossRef]

- Windhorst U, Dibaj P (2023) Plastic spinal motor circuits in health and disease. J Integr Neurosci 22(6):167. [CrossRef]

- Windhorst U, Meyer-Lohmann J, Kirmayer D, Zochodne D (1997) Renshaw cell responses to intra-arterial injection of muscle metabolites into cat calf muscles. Neurosci Res 27(3):235-247. [CrossRef]

- Yamada T, Ashida Y, Tamai K, Kimura I, Yamauchi N, Naito A, Tokuda N, Westerblad H, Andersson DC, Himori K (2022) Improved skeletal muscle fatigue resistance in experimental autoimmune myositis mice following high-intensity interval training. Arthritis Res Ther 24:156. [CrossRef]

- Zabihhosseinian M, Yielder P, Berkers V, Ambalavanar U, Holmes M, Murphy B (2020) Neck muscle fatigue impacts plasticity and sensorimotor integration in cerebellum and motor cortex in response to novel motor skill acquisition. J Neurophysiol 124(3):844-855. [CrossRef]

- Zgaljardic DJ, Durham WJ, Mossberg KA, Foreman J, Joshipura K, Masel BE, Urban R, Sheffield-Moore M (2014) Neuropsychological and physiological correlates of fatigue following traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 28(4):389–397. [CrossRef]

- Zwarts MJ, Bleijenberg G, van Engelen BGM (2008) Clinical neurophysiology of fatigue. Clin Neurophysiol 119(1):2-10. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).