Introduction

In advanced healthcare systems, where medical infrastructure is well-developed, the prevalence of multiple comorbidities rises alongside aging populations, leading to an increase in long-term medication usage. The issue of polypharmacy, the regular use of five or more medications, has been a concern since 1959 when D.G. Friend first highlighted the risks in the

New England Journal of Medicine [

1]. While the availability of medications for managing chronic and acute conditions has undoubtedly contributed to improved longevity and quality of life, it has also led to a rise in medication-related adverse events, often associated with polypharmacy. Studies show a correlation between the number of medications and adverse outcomes such as mortality, falls, fractures, hospitalizations, as well as functional and cognitive decline [2, 3].

There is extensive research on polypharmacy, often targeting adult or elderly populations across various settings (communnity, nursing homes, hospitals). Interventions to address polypharmacy are typically led by pharmacists, physicians, or multidisciplinary teams conducting comprehensive medication reviews (CMR). Primary outcomes in these studies vary, ranging from reducing potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) to improving quality of life, reducing rehospitalization, or mortality rates.

In 2019, Anderson et al. [

4] conducted a systematic review (SR) of interventions addressing polypharmacy from 2004 to 2017, identifying six high-quality SRs. The review concluded that while polypharmacy interventions improved medication appropriateness, there was limited consistent evidence for significant outcomes in healthcare use or mortality reduction.

A more recent meta-analysis reviewed 14 systematic reviews published between January 2017 and October 2022, encompassing 179 unique studies [

5]. This analysis included a range of intervention types and settings. Despite various recommended interventions, evidence remained limited in terms of reducing PIMs, prescribing omissions (PPOs), or improving medication adherence and appropriateness. The quality of evidence for improving outcomes such as mortality and readmission was low, with most studies showing mixed or negligible effects. Only one systematic review demonstrated a significant reduction in hospitalizations following intensive outpatient intervention [

6], and another found effective fall reduction after discontinuation of PIMs [

7].

Given the lack of research on screening for polypharmacy in emergency department settings and the absence of proven methodologies for its reduction, we conducted this study. We aimed to explore the synergistic collaboration between clinical physicians, pharmacists, and social workers using a Team Resource Management (TRM) approach. The primary objectives were to quantify the optimization ratio of prescriptions for patients with polypharmacy and to determine the probability and improvement ratio of polypharmacy among individuals with specific comorbidities.

Materials Study Design and Methods

This pilot study involved the random collection of medical records from the Internal Medicine Department of Taipei MacKay Emergency Department between August 1, 2023, and October 31, 2023. Attending emergency physicians accessed cloud-based medication history records to assess patients’ past medical history and the number of long-term prescribed medications. For cases involving polypharmacy (defined as the use of five or more medications), pharmacists provided medication education, while social workers contacted patients by phone to encourage follow-up visits to outpatient clinics for deprescribing.

TRM Polypharmacy Interview Guide:

Introduction: Introduce yourself and explain the purpose of the call, which is to provide telephone care for individuals taking multiple (five or more) medications.

Medication Overview: Discuss the current treatment plan, including which medications are being used, the type and quantity of drugs, and who is primarily responsible for medication management.

Risks of Polypharmacy: Explain the risks associated with polypharmacy:

(1) Drug-drug interactions increase the risk of falls.

(2) Polypharmacy can increase the burden on organs.

Health Education: Provide the following information:

(1) The pharmacist consultation hotline is listed on the medicine bag from our hospital. If you have any questions about polypharmacy, please call: 886-2-2543-3535 ext. 2291.

(2) For patients needing deprescribing, a pharmacist consultation at our hospital is available without a registration fee.

(3) Patients with multiple chronic conditions are advised to consult with their doctor during follow-up visits about integrating medications from different departments. Patients should not discontinue or adjust medications on their own.

If patients return to the outpatient clinic, physicians follow up on their medical records and assess the optimized medication quantity, ultimately evaluating the prevalence of polypharmacy and any reduction in the number of medications prescribed.

Statistical Analysis:

Commercial software was used to conduct statistical analyses. Student t-tests were employed to assess the significance of changes, and linear regression was used to determine correlations between the prevalence of comorbidities in the polypharmacy group before and after deprescribing. A p-value of <0.05 (2-tailed) was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS 25 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY).

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of MacKay Memorial Hospital (approval reference no. 24MMHIS048e).

Results

Our research results on polypharmacy and the effects of deprescribing in a group of adult patients admitted to an internal medicine emergency department.

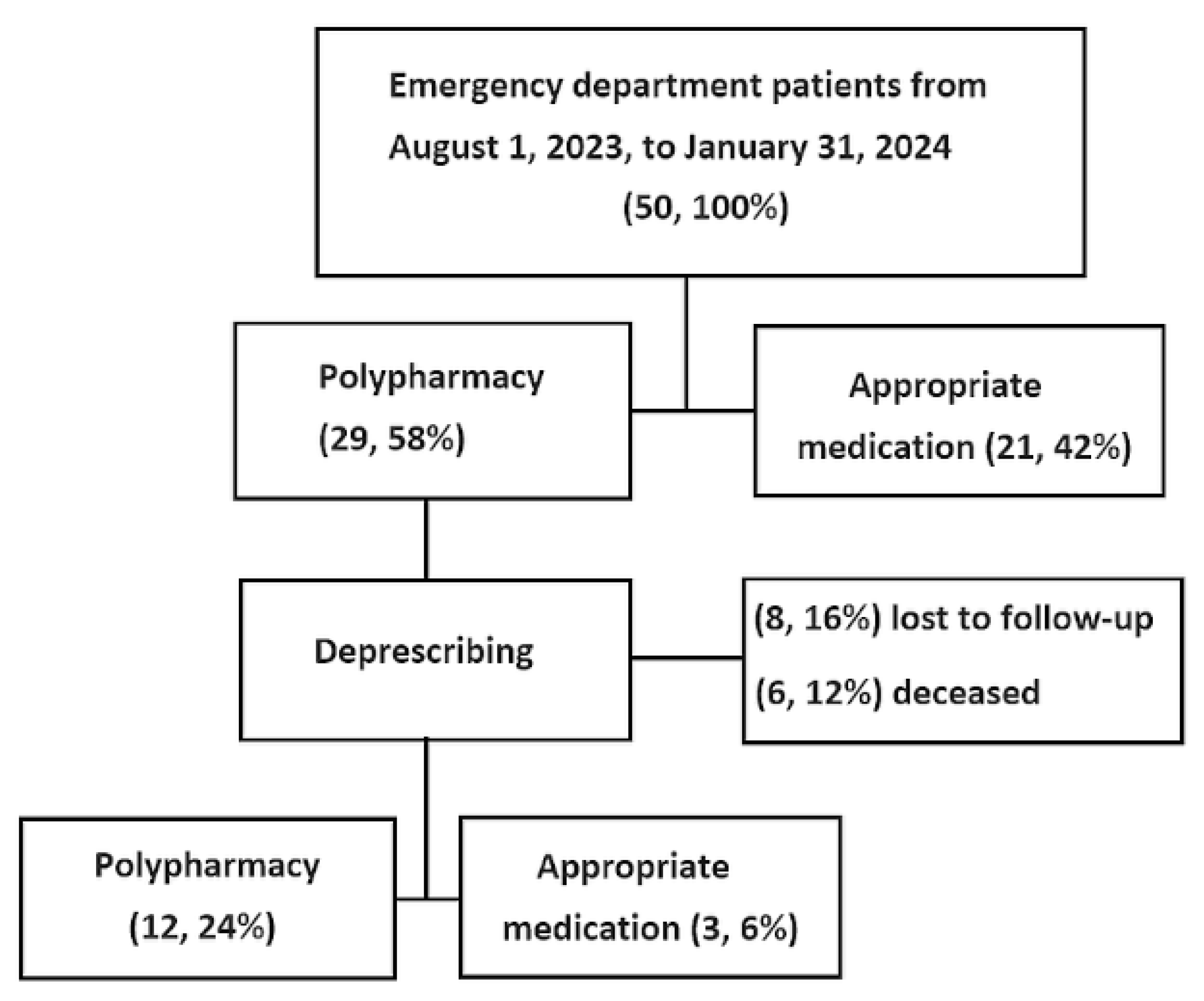

Participants: 50 adults admitted to the emergency department. 21 patients took fewer than 5 medications. 29 patients took more than 5 medications (polypharmacy).

Data Collection: Age, gender, glucose levels, creatinine levels, and number of medications were recorded (in

Table 1).

Deprescribing Follow-Up: 14 patients were excluded due to loss of follow-up (8 patients, 16%) or death (6 patients, 12%) (see

Figure 1).

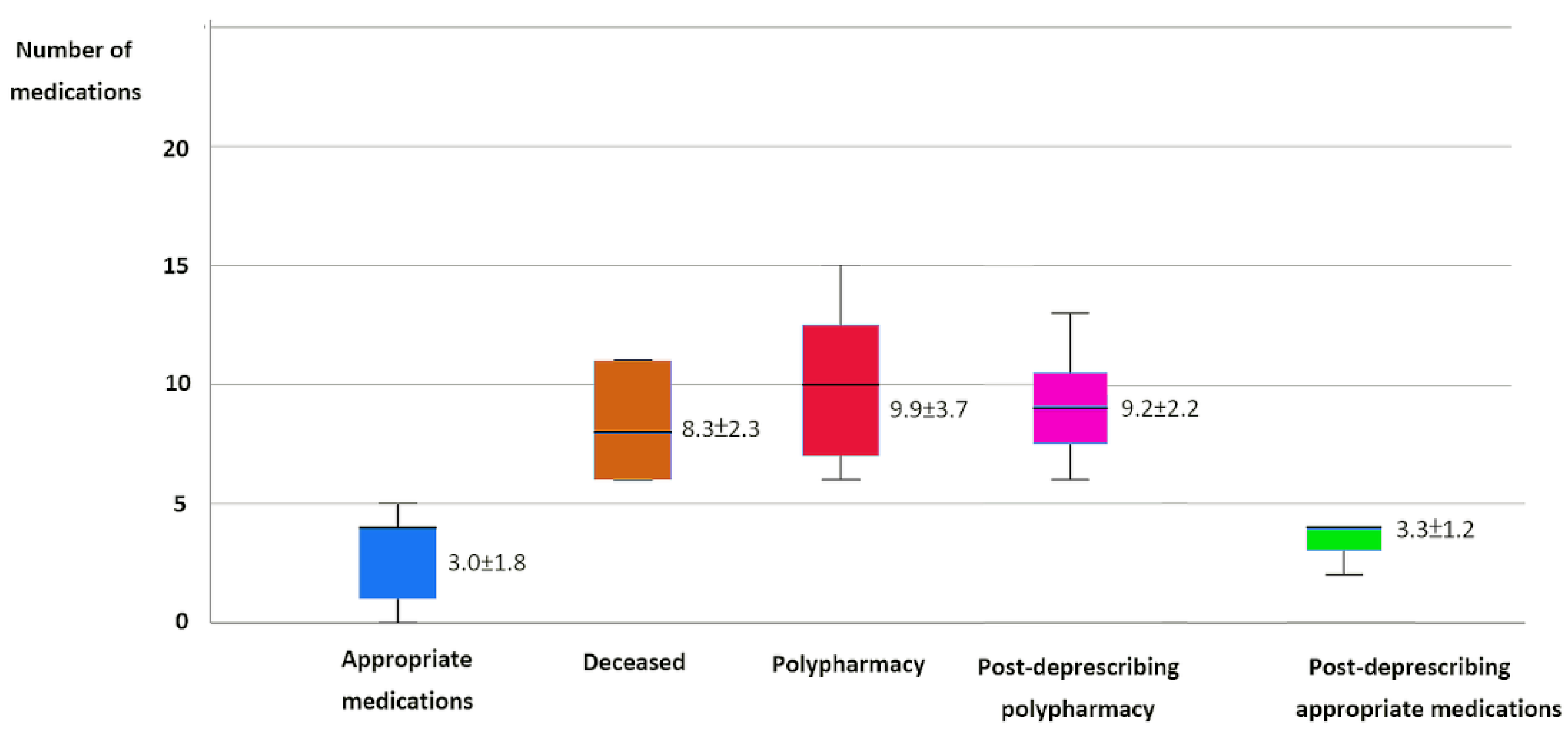

Medication Details: The mean number of appropriate medications was 3.0±1.8. For polypharmacy patients, the mean number of medications was 9.9±3.7 (

Figure 2).

Post-Deprescribing Results: 12 patients continued with polypharmacy after deprescribing (33.3%), with an average of 9.2±2.2 medications. For 3 patients, the mean appropriate medication number was 3.3±1.2 (

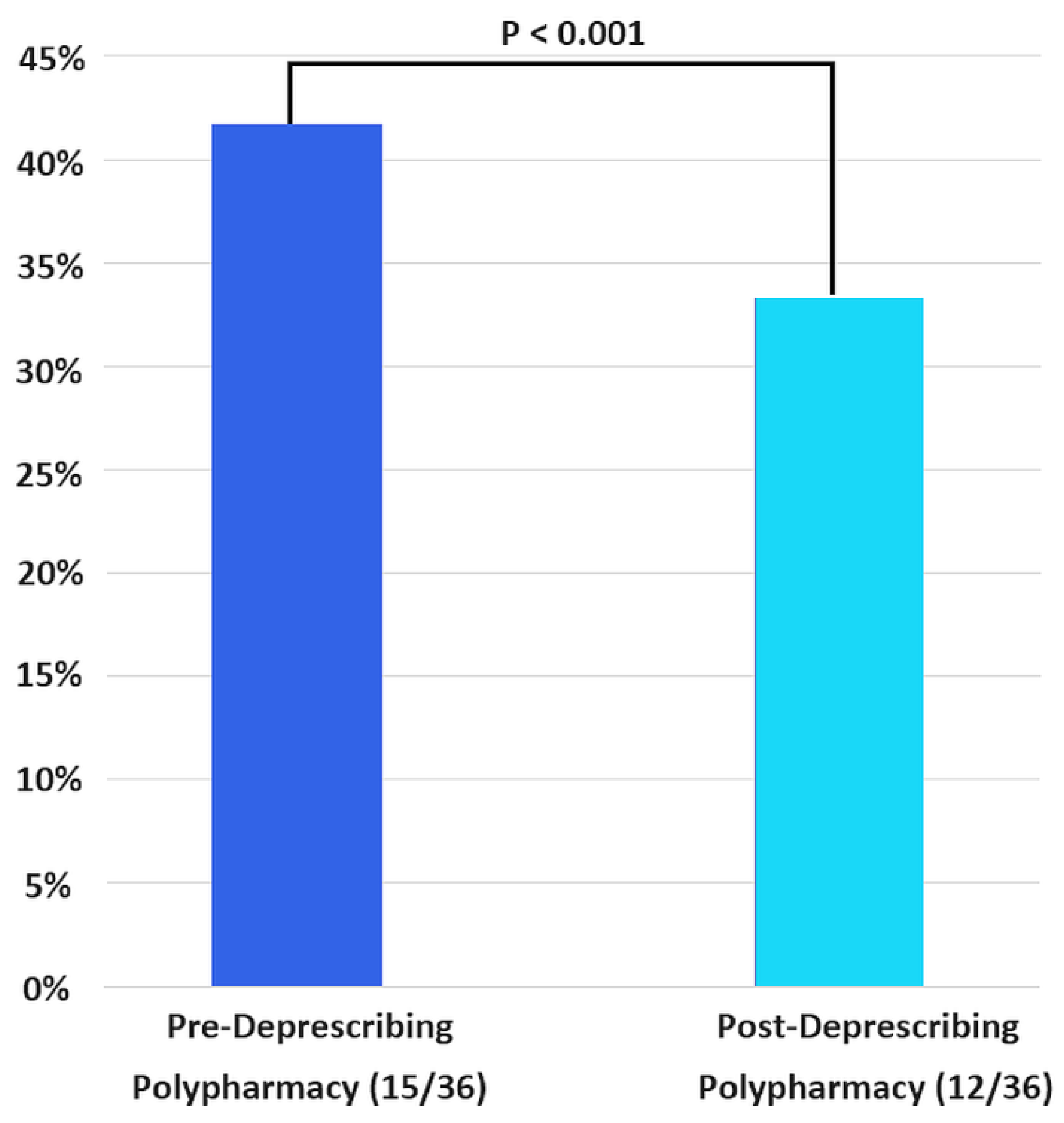

Table 2). The prevalence of polypharmacy significantly decreased after deprescribing, from 41.7% (15/36) to 33.3% (12/36), with a

p-value of <0.001 (

Figure 3).

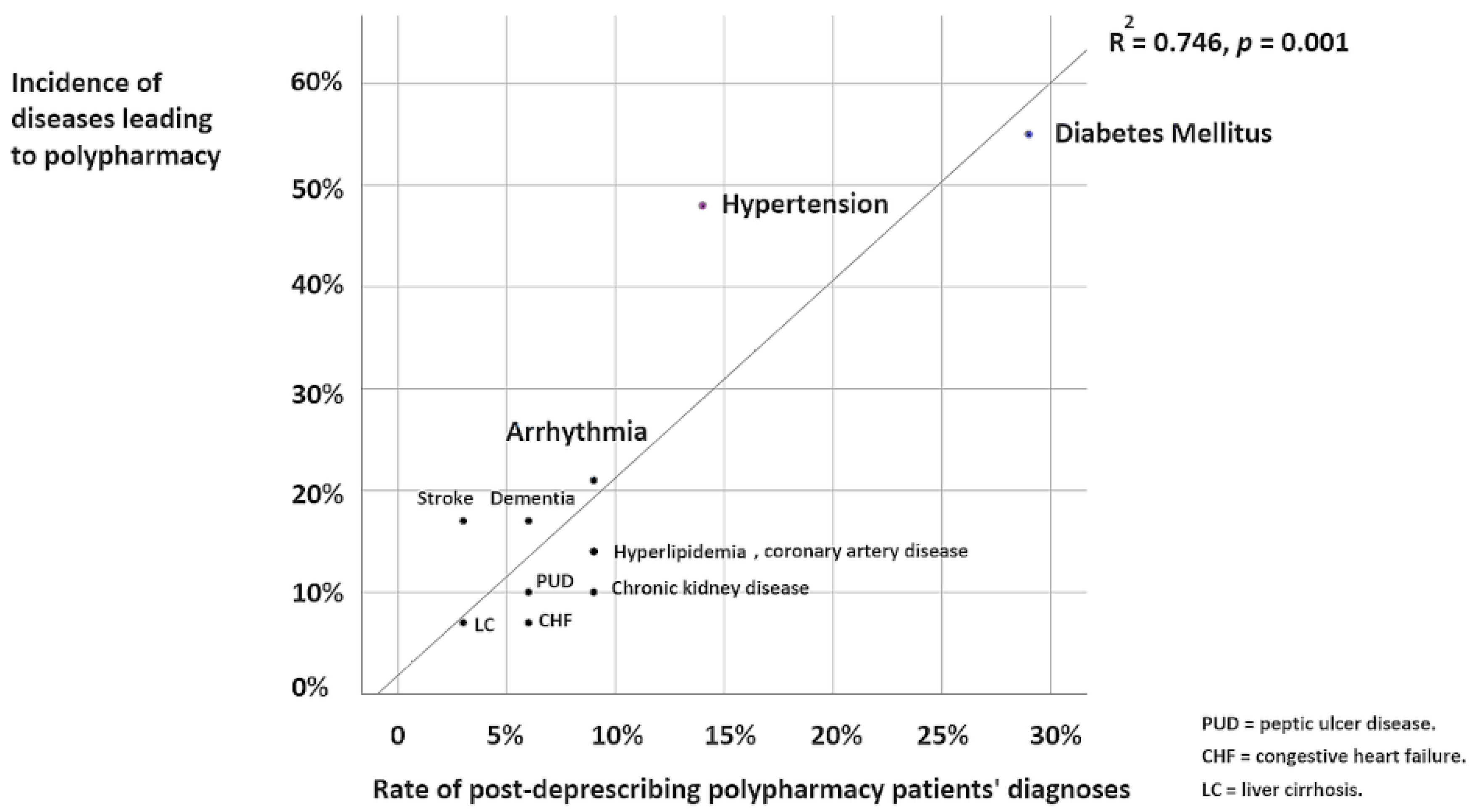

Disease Correlations: Common diseases leading to polypharmacy were

diabetes and hypertension. These conditions also had higher incident rates post-deprescribing. Other conditions (arrhythmia, stroke, dementia, etc.) had lower incidence rates. There was a strong positive correlation (R² = 0.746,

p = 0.001) between pre- and post-deprescribing polypharmacy incidents across diseases (

Figure 4).

Discussion

Polypharmacy Occurs Worldwide

Polypharmacy, the use of multiple medications, varies significantly across regions. In the U.S., polypharmacy rates among adults aged 65 and older are estimated to be as high as 65% [

8]. In Europe, the prevalence in older adults ranges from 26% to 40% [

9]. Other countries report similar or even higher rates, with estimates of 36% in Australia [

10], 42% in South Korea [

11], and 49% in India [

12].

Polypharmacy presents a major public health challenge for the elderly and is expected to become even more burdensome as more individuals develop long-term conditions. It is associated with increased risks of mortality, falls, fractures, hospitalizations, and functional and cognitive decline [

2]. There is an urgent need for effective polypharmacy management to reduce prescription risks and healthcare costs.

Comprehensive Medication Review (CMR) to Stop Potentially Inappropriate Medications

In the United States, Medication Therapy Management (MTM), and its counterpart medication use review (MUR) in the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth nations, are services typically provided by pharmacists or medical professionals. These services aim to enhance patient outcomes by increasing awareness of health conditions and the medications used to manage them. A core requirement of MTM is for pharmacists to perform a Comprehensive Medication Review (CMR) at least once a year.

The purpose of CMR is to “improve patients’ knowledge of their prescriptions, over-the-counter (OTC) medications, herbal therapies, and dietary supplements, identify and address problems or concerns that patients may have, and empower patients to self-manage their medications and health conditions” [

16]. This review can be conducted through telehealth or face-to-face interactions, after which the patient is given an action plan aimed at optimizing their therapy. The plan may include medication adherence reminders, recommendations to stop inappropriate prescriptions, or dosage adjustments advised to their physician.

A recent meta-analysis revealed that CMR for hospitalized elderly polypharmacy patients likely reduces hospital readmissions and may decrease emergency department revisits. However, the analysis found no significant benefit in terms of increased survival rates or improved quality of life [

17].

Additionally, a study on a

pharmacist-physician collaborative MTM program involving 178 polypharmacy elderly outpatients demonstrated significant cost savings. The program led to a reduction in hospitalizations, emergency department visits, monthly medication costs per patient, and total healthcare costs. These findings suggest that collaborative MTM programs can effectively reduce healthcare utilization and expenses among elderly patients with polypharmacy [

18].

The Increasing Severity of Polypharmacy Among the Elderly

In our study, the prevalence of polypharmacy was

58% before deprescribing, with patients taking up to an average of 9.9 medications—nearly reaching

hyper-polypharmacy levels (more than 10 medications) [

11]. This issue is not confined to our emergency room; it is a widespread global concern, particularly affecting the elderly [

19]. Several factors, including demographics, lifestyle, nutrition, and healthcare utilization, contribute to polypharmacy and the elevated risk of medication-related problems.

A longitudinal study conducted across European countries such as the Netherlands, Greece, Croatia, Spain, and the United Kingdom revealed that

45.2% of older community-dwelling adults experienced polypharmacy, and

41.8% were at high risk for medication-related issues [

20]. In the Asia-Pacific region, recent studies found that the highest prevalence of polypharmacy among the elderly was in

Hong Kong (46.4%), followed by

Taiwan (38.8%) and

South Korea (32.0%) [

21]. Similarly, another study highlighted that

45% of Australians over the age of 70 experienced polypharmacy, with

8% suffering from hyper-polypharmacy (the use of 10 or more unique medications) [

22].

Concerningly, polypharmacy rates among adults have been steadily rising. In the United States, the prevalence of polypharmacy in adults over 65 increased from

23.5% in 1998 to 44.1% in 2017. This upward trend is also evident in patients with chronic diseases, such as heart disease (rising from

40.6% to 61.7%) and diabetes (increasing from

36.3% to 57.7%) [

23]. The growing use of antidepressant medications may also be contributing to this trend [

24].

Deprescribing Successfully Saves Medical Expenses and Improves Health

The effectiveness of deprescribing interventions in our study aligns with international findings on polypharmacy reduction. In Japan, for example, the 2016 medication fee amendment introduced an incentive system that awarded

250 medication points (approximately 22.5 US

$) to hospitals and clinics that successfully reduced the number of medications by at least two in patients taking six or more drugs [

25]. This policy resulted in a

19.3% reduction in polypharmacy in the

75–89 years age group and a

16.5% reduction in the

90 years and above age group over four years [

26].

In the United States, a study conducted in October 2007 at a long-term care facility affiliated with a hospital reviewed the medication lists of all nursing home residents. Geriatric medicine fellows, along with a faculty geriatrician, used the

2003 Beers Criteria and the

Epocrates online drug-drug interaction program to assess and recommend changes to the residents’ medication regimens. This intervention reduced the average number of medications per resident from

16.6 to 15.5 [

27].

Similarly, a study in Spain showed that pharmacist-led interventions in primary care significantly improved polypharmacy management among community-dwelling elderly individuals over a 12-month period. The intervention resulted in an annual drug expenditure reduction of

233.75 €/patient, compared to

169.40 €/patient in the control group, yielding a savings of

64.30 € per patient per year [

28].

These international findings highlight the success of structured deprescribing efforts in reducing polypharmacy and associated costs. Our study supports these outcomes, demonstrating that team-based resource management can effectively reduce the medication burden and potentially lower healthcare expenses in various settings.

Still, Some Comorbidities Make Polypharmacy Inevitable

Our study highlights several factors that contribute to the persistence of polypharmacy, even with deprescribing efforts. Chronic conditions such as

diabetes mellitus (DM),

hypertension (HTN), and

arrhythmias often require complex medication regimens based on clinical guidelines, making polypharmacy sometimes unavoidable [

29]. For instance, a study in the USA found that

depression had the strongest association with medication-related problems (MRPs). Other conditions like

diabetes,

congestive heart failure,

end-stage renal disease,

respiratory conditions, and

hypertension were also significantly linked to MRPs. Additionally, with each chronic medication added, the odds of developing an MRP increased by

10% [

30].

In Beijing, a multicenter cross-sectional study revealed that

inappropriate prescribing was commonly associated with

coronary heart disease and

hyper-polypharmacy (use of ≥10 drugs). The cardiology department had the highest proportion of patients with potentially inappropriate medications, largely due to the use of vasodilators like isosorbide mononitrate, as more than half of the patients had coronary heart disease [

31].

For example, the

American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidelines for managing type 2 diabetes may involve using multiple classes of antidiabetic medications to achieve target glycemic control. Patients may need up to four different types of glucose-lowering agents, including

metformin,

SGLT2 inhibitors,

GLP-1 receptor agonists,

DPP-4 inhibitors, and

insulin [

32].

Similarly, patients with

resistant hypertension often experience “inevitable polypharmacy” as per the

American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines. These patients may require four or more antihypertensive medications to control their blood pressure. A typical regimen for resistant hypertension includes a

diuretic,

calcium channel blocker,

ACE inhibitor or ARB, and sometimes a

mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist like spironolactone [

33,

34].

Deprescribing efforts also face several barriers beyond chronic conditions. Dee Magin et al. categorized these barriers into three levels:

Patient level: Patients’ preferences, attitudes, and knowledge often influence their willingness to reduce medications, with some patients reluctant to decrease medications despite medical recommendations.

Healthcare provider level: Physicians and pharmacists’ beliefs, knowledge gaps, and time constraints can hinder proper medication management, particularly when there’s unfamiliarity with drug side effects or insufficient time for comprehensive assessments.

System level: Structural factors within the healthcare system, such as limited interdisciplinary teamwork, resource shortages, and reimbursement models that do not prioritize medication management, also pose challenges to effective deprescribing [

35].

Conclusion

Polypharmacy is a significant global medication issue, with affected patients being, on average, 12.5 years older than those on appropriate medication regimens. On average, patients with polypharmacy take 6.9 more medications than those with appropriate medication use. After deprescribing interventions, this gap is reduced to 5.9 medications compared to appropriate medication patients.

Deprescribing plays a crucial role in transitioning polypharmacy toward appropriate medication management, particularly in the elderly. Our team’s resource management model reduced polypharmacy by 8.4% in the emergency department. This approach not only alleviates the medication burden on patients’ organs but also offers potential savings in healthcare costs. However, certain chronic conditions such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and arrhythmia continue to pose challenges, often leading to unavoidable polypharmacy.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. Firstly, while our analysis focused on reducing polypharmacy rates, we did not assess the potential cost savings associated with deprescribing. Including such an analysis could have added valuable insights to our findings. Secondly, compared to studies that assess national policies on polypharmacy reduction, our sample size was relatively small. However, this study serves as a preliminary investigation conducted within a single medical center. The success of our team-based management approach suggests that it could be scaled for broader implementation in other hospital settings.

Finally, we did not evaluate the effect of reduced polypharmacy on patient health outcomes or healthcare utilization, such as improved medication adherence or fewer emergency room visits due to chronic condition exacerbations. Future research should explore these critical outcomes to better understand the full spectrum of benefits from deprescribing initiatives.

Abbreviations

comprehensive medication review (CMR)

potentially inappropriate medication (PIM)

potential prescribing omissions (PPOs)

medication therapy management (MTM)

medication use review (MUR)

over-the-counter (OTC)

diabetes mellitus (DM)

medication-related problems (MRPs)

American Diabetes Association (ADA),

American Heart Association (AHA)

References

- Friend, D.G. Polypharmacy—Multiple-Ingredient and Shotgun Prescriptions. N. Engl. J. Med. 1959, 260, 1015–1018. [CrossRef]

- Khezrian, M.; McNeil, C.J.; Murray, A.D.; Myint, P.K. An Overview of Prevalence, Determinants, and Health Outcomes of Polypharmacy. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2020, 11, 2042098620933741. [CrossRef]

- Fried, T.R.; O’Leary, J.; Towle, V.; Goldstein, M.K.; Trentalange, M.; Martin, D.K. Health Outcomes Associated with Polypharmacy in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2014, 62, 2261–2272. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.J.; Schnipper, J.L.; Nuckols, T.K.; Shane, R.; Sarkisian, C.; Le, M.M.; et al. A Systematic Overview of Systematic Reviews Evaluating Interventions Addressing Polypharmacy. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2019, 76, 1777–1787. [CrossRef]

- Keller, M.S.; Qureshi, N.; Mays, A.M.; Sarkisian, C.A.; Pevnick, J.M. Cumulative Update of a Systematic Overview Evaluating Interventions Addressing Polypharmacy. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2350963. [CrossRef]

- Mizokami, F.; Mizuno, T.; Kanamori, K.; Oyama, S.; Nagamatsu, T.; Lee, J.K.; et al. Clinical Medication Review Type III of Polypharmacy Reduced Unplanned Hospitalizations in Older Adults: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2019, 19, 1275–1281. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Negm, A.; Peters, R.; Wong, E.K.C.; Holbrook, A. Deprescribing Fall-Risk Increasing Drugs (FRIDs) for the Prevention of Falls and Fall-Related Complications: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e035978. [CrossRef]

- Young, E.H.; Pan, S.; Yap, A.G.; Reveles, K.R.; Bhakta, K. Polypharmacy Prevalence in Older Adults Seen in United States Physician Offices from 2009 to 2016. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255642. [CrossRef]

- Midao, L.; Giardini, A.; Menditto, E.; Kardas, P.; Costa, E. Polypharmacy Prevalence among Older Adults Based on the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2018, 78, 213–220. [CrossRef]

- Page, A.T.; Falster, M.O.; Litchfield, M.; Pearson, S.A.; Etherton-Beer, C. Polypharmacy among Older Australians, 2006–2017: A Population-Based Study. Med. J. Aust. 2019, 211, 71–75. [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.J.; Chae, J.; Yoon, S.H.; Kim, D.S. Aging and the Prevalence of Polypharmacy and Hyper-Polypharmacy among Older Adults in South Korea: A National Retrospective Study during 2010–2019. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 866318. [CrossRef]

- Bhagavathula, A.S.; Vidyasagar, K.; Chhabra, M.; Rashid, M.; Sharma, R.; Bandari, D.K.; et al. Prevalence of Polypharmacy, Hyperpolypharmacy, and Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults in India: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 798418. [CrossRef]

- Mikeal, R.L.; Brown, T.R.; Lazarus, H.L.; Vinson, M.C. Quality of Pharmaceutical Care in Hospitals. Am. J. Hosp. Pharm. 1975, 32, 567–574. [CrossRef]

- Hepler, C.D.; Strand, L.M. Opportunities and Responsibilities in Pharmaceutical Care. Am. J. Hosp. Pharm. 1990, 47, 533–543. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.R.; Clancy, C.M. Medication Therapy Management Programs: Forming a New Cornerstone for Quality and Safety in Medicare. Am. J. Med. Qual. 2006, 21, 276–279. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Fact Sheet Summary of 2019 MTM Programs. 2019. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/CY2019-MTM-Fact-Sheet.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Bülow, C.; Clausen, S.S.; Lundh, A.; Christensen, M. Medication Review in Hospitalised Patients to Reduce Morbidity and Mortality. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 1, CD011384. [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.W.; Lin, C.H.; Chang, C.K.; Chou, C.Y.; Yu, I.W.; Lin, C.C.; et al. Economic Outcomes of Pharmacist-Physician Medication Therapy Management for Polypharmacy Elderly: A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled Trial. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2018, 117, 235–243. [CrossRef]

- Hung, A.; Kim, Y.H.; Pavon, J.M. Deprescribing in Older Adults with Polypharmacy. BMJ 2024, 385, e76845. [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; et al. Factors Associated with Polypharmacy and the High Risk of Medication-Related Problems among Older Community-Dwelling Adults in European Countries: A Longitudinal Study. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 841. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; et al. Trends of Polypharmacy among Older People in Asia, Australia, and the United Kingdom: A Multinational Population-Based Study. Age Ageing 2023, 52, afad014. [CrossRef]

- Wylie, C.E.; et al. A National Study on Prescribed Medicine Use in Australia on a Typical Day. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2020, 29, 1046–1053. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; et al. Prevalence and Trends of Polypharmacy in US Adults, 1999–2018. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2023, 8, 25. [CrossRef]

- Charlesworth, C.J.; et al. Polypharmacy among Adults Aged 65 Years and Older in the United States: 1988–2010. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2015, 70, 989–995. [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.; Takahashi, K.; Saito, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Otsuka, T.; Nakamura, M.; Hayashi, T. Effectiveness of Polypharmacy Reduction Policy in Japan: Nationwide Retrospective Observational Study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2022, 44, 1–9.

- Ishida, T.; Suzuki, A.; Nakata, Y. Nationwide Long-Term Evaluation of Polypharmacy Reduction Policies Focusing on Older Adults in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14684. [CrossRef]

- Kojima, G.; Bell, S.P.; Tamura, B.K.; Inouye, S.K. Reducing Cost by Reducing Polypharmacy: The Polypharmacy Outcomes Project. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2012, 13, 818.e11–818.e15. [CrossRef]

- Campins, L.; Serra-Prat, M.; Gallo, P.; García, M.L.; Espinosa, L.; Blanco, A.; Costa, A.; Sartini, M.; Cabanas, M. Reduction of Pharmaceutical Expenditure by a Drug Appropriateness Intervention in Polymedicated Elderly Subjects in Catalonia (Spain). Gac. Sanit. 2019, 33, 106–111. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, P.; Woolford, S.J.; Patel, H.P. Multi-Morbidity and Polypharmacy in Older People: Challenges and Opportunities for Clinical Practice. Geriatrics 2020, 5, 85. [CrossRef]

- Almodóvar, A.S.; Nahata, M.C. Associations between Chronic Disease, Polypharmacy, and Medication-Related Problems Among Medicare Beneficiaries. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2019, 25, 573–577. [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Lu, Q.; Shi, S.; Zou, J.; Song, Y.; Ma, W.; Zhang, F.; Fan, X.; Yu, L.; Tang, Z.; et al. A Combination of Beers and STOPP Criteria Better Detects Potentially Inappropriate Medications Use Among Older Hospitalized Patients with Chronic Diseases and Polypharmacy: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 44. [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. Erratum. 9. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47(Suppl. 1), S158–S178. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M.; Shin, J. Role of Home Blood Pressure Monitoring in Resistant Hypertension. Clin. Hypertens. 2023, 29, 2. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, F.; Teixeira, M.; Alves, A.J.; Sherwood, A.; Blumenthal, J.A. Lifestyle Medicine as a Treatment for Resistant Hypertension. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2023, 25, 313–328. [CrossRef]

- Mangin, D.; Dalleur, O.; Jansen, J.; Le Couteur, D.; Hilmer, S.N. Theoretical Underpinnings of a Model to Reduce Polypharmacy and Its Negative Health Effects: Introducing the Team Approach to Polypharmacy Evaluation and Reduction (TAPER). J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2024, 72, 89–96. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).