1. Background

Interventional bronchoscopy is a promising and expanding branch of medicine. Until recently, the field was largely limited to procedures like bronchoalveolar lavage, sputum collection, foreign body removal, placement of stents and endobronchial ultrasound. However, recently many new procedures are added to the armamentarium such as robot assisted bronchoscopy and deployment of endobronchial valves. Some rather newer procedures like bronchial thermoplasty (BT) are taking a backseat. The most recent addition to these procedures is catheter ablation for lung cancer. In addition, developments have happened in anesthesia too, one of the most noticeable of them is in the field of pharmacology. Sugammadex, a new skeletal muscle relaxant reversal agent has largely eliminated the need for high dose remifentanil based total intravenous anesthesia. Pulmonologists are more recently drawn to a newer benzodiazepine remimazolam, a faster acting version of midazolam (versed) with unique properties suited to certain bronchoscopy procedures such as bronchial lavage and flexible diagnostic bronchoscopy. Another drug gaining popularity during bronchoscopy is dexmedetomidine. Although both were discussed briefly in the previous review, an updated discussion is warranted. Use of laryngeal mask airway has diminished, and many pulmonologists are comfortable with a larger than “standard” endotracheal tube for procedures such as endobronchial ultrasound. In this review, we aim to address contemporary anesthesia management of both mainstream and newer bronchoscopic procedures.

2. Role of Local Anesthetics in Bronchoscopy

With increasing popularity of deep sedation and general anesthesia for the majority of bronchoscopic procedures, the role of local anesthesia as a sole anesthetic has vastly diminished. Even for routine diagnostic bronchoscopy, at Jefferson, we use moderate sedation. However, in certain high-risk patients such as those on high flow nasal cannula or those with very high oxygen requirements, local alone anesthesia alone might be safer. Local anesthesia is, however, used frequently along with sedation.

However, nebulized lidocaine continues to be employed in some countries and certain situations such as diagnostic flexible bronchoscopy to suppress coughing. Recently, more studies have been published on the mode of delivery.

Dhooria et al. (2020) conducted an optimum mode of delivering lidocaine study [

1]. In a total of 1,050 subjects (randomized 1:1:1), they compared nebulized lignocaine (2.5 mL of 4% solution), oropharyngeal spray (10 actuations of 10% lignocaine), or combined nebulization (2.5 mL, 4% lignocaine) and two actuations of 10% lignocaine spray. Their primary end point was comparison of severity of coughing as rated by the patient. Cough severity as rated by the bronchoscopist, and procedural satisfaction were other measures. They concluded that, for diagnostic flexible bronchoscopy, ten actuations of 10% lignocaine oropharyngeal spray provided the best conditions. However, it should be noted that, in addition to the above, all patients also received 5 mL of lignocaine gel (applied to the nasal cavity) and four aliquots of 2 mL of 1% lignocaine solution. The total lidocaine dose on average in each group was about 300 mg. In another study, Islamitabar et al. (2022), compared nebulized lidocaine and intratracheally administered (spray-as-you-go) lidocaine for their ability to reduce pain and cough during bronchoscopy [

2]. They concluded that nebulized lidocaine was more effective in both cough and pain reduction. It should be noted that often sedatives such as fentanyl and midazolam are administered along with local lidocaine during flexible bronchoscopy. In patients undergoing bronchoscopy requiring endobronchial or transbronchial biopsy, Dreher et.al, (2016) found that nebulized lidocaine was both safe and effective. In addition, when compared to lidocaine spray technique, nebulized group required less lidocaine and fentanyl.

Lidocaine is also administered by intravenous route to suppress the cardiovascular response to endotracheal intubation (such as elevated blood pressure and pulse) and other responses such as cough reflexes, occasional dysrhythmias, increased intracranial pressure, and increased intraocular pressure. This is especially true in certain patient populations like atherosclerotic heart disease, potential intracranial lesions, and potential penetrating eye injuries [

3]. It can effectively blunt cough reflexes and dysrhythmias [

4]. In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease undergoing bronchoscopy, intravenous lidocaine infusion resulted in a significant reduction in propofol requirements [

5]. Patients in this study received 2 mg/kg, followed by 4 mg/kg/h of lidocaine in addition to propofol infusion.

A word of caution is warranted here. It is generally accepted that major adverse events related to lidocaine are seen at plasma levels above 5 mcg/mL [

6], and serious toxicity such as seizures and fatal cardiac arrhythmias occur only at 3 to 4 times of such concentrations. Nonetheless, specific groups such as elderly, those with long hospitalizations, congestive heart failure, diminished hepatic clearance of lidocaine predispose to serious adverse reactions [

7,

8,

9] at doses considered as safe in healthy individuals. It is reported that administration of 280-mg dose via intermittent positive pressure breathing and nebulization of a 400-mg dose via ultrasound, resulted in plasma concentrations of lidocaine no more than 1.1 µg/ml [

10]. Contrarily, seizure is reported in a 28-year-old with AIDS, chronic end-stage renal failure, anemia, congestive heart failure (CHF), cardiomyopathy, and increased liver function tests, after administration of a total dose of topical lidocaine 300 mg. Plasma lidocaine concentrations in this patient, soon after seizure and at 4 and 22 hours, were 12.0, 7.6, and 1.4 mg/L, respectively. As a result, it is important to review the patients’ comorbidities with a particular reference to cardiac and liver function.

3. Electromagnetic Bronchoscopy Techniques and Their Anesthetic Implications

3.1. History, Methodology and Indications

While respiratory infections continue to be the commonest indication for flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy, lung nodule/s is the second most common indication [

11]. In both men and women, lung cancer (both small cell and non-small cell) is the second most common cancer [

12]. Low-dose computed tomography (also called a low-dose CT scan, or LDCT) is the only currently recommended tool for lung cancer screening [

13]. The need for screening is dictated by the smoking history and age. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening in those who satisfy all the following criteria, although it states that the net benefit of screening is moderate.

Have a 20 pack-year or more smoking history, and

Smoke now or have quit within the past 15 years, and

Are between 50 and 80 years old.

As a group, they clearly pose a higher anesthesia risk. Beyond that, the low-dose CT scan employed as a screening tool has limitations. The US Preventive Services Task Force finds that LDCT has a sensitivity that ranged from 59% to 100%, specificity of 26.4% to 99.7%, positive predictive value of 3.3% to 43.5%, and negative predictive value of 97.7% to 100%. By definition, a lung nodule is less than three centimeters in size. Only about 5% of small nodules are cancerous and the remainder could be granulomas (benign) tumors or cysts, inflammatory diseases, scar tissue from an old infection or congenital lung abnormalities. The risk of malignancy increases with the size of these modules. Only nodules that are considered as high risk or seen increasing in size in follow-up scans may require biopsy.

A major challenge with any technique of bronchoscopy is to achieve a high diagnostic yield of the lesion in question. Navigational bronchoscopy (NB), the most recent is robot assisted NB, is a novel technique uniquely suited for diagnosing both peripheral and central nodules. Some use electromagnetic field, while others might use shape sensing technology. It has the best combination of higher diagnostic yield and a low complication rate [

14]. It involves obtaining a chest CT before the procedure and creating a three-dimensional (3D) virtual airway map through which the bronchoscopist navigates to locate the lung nodules. This is followed by biopsy and (or) interventions such as a fiducial marker before resection [

14].

Regardless of the technology employed to access the peripheral pulmonary lesions, in addition to many factors such as lesion location, lesion size, presence of a bronchus sign, and registration error, anesthesia strategy is important. Majority of the anesthesia providers work in the bronchoscopy suite on an ad hoc basis and as a result, might lack an understanding of the procedural aspects and consequent anesthesia implications [

15].

The anesthesia provider should do everything to provide the most optimum conditions for the pulmonologist to reach the lesion and get a biopsy. The CT scans, on which the NB relies, are performed in awake patients breathing air. Pulmonary atelectasis creates computed tomography to body divergence, and can obscure the target lesion on intraprocedural cone beam computed tomography images, thereby affecting both the navigational and diagnostic yield of the procedure [

16]. However, in contemporary practice, most places (including at Jefferson) don’t use cone beam. most rely on conventional fluoroscopy, or augmented fluoroscopy. Performing a staging endobronchial ultrasound before NB poses further challenges. Administration of general anesthesia, both intravenous and inhalational, causes lung collapse, which is seen in about 90 % of all patients [

17]. It can also result in false positive radial probe ultrasound images. In patients undergoing bronchoscopy, 89% of patients were found to have atelectasis in one segment while 32% in at least six of the eight evaluated segments [

16,

18]. In this context, the anesthesia goals/requirements for NB include avoidance of excessive chest movement, and avoidance of atelectasis.

Park P et al., (2021) measured post operative atelectasis with an ultrasound, 30 minutes after the procedure transfer to the post operative care unit. Those administered an inspired oxygen of 0.35, during induction and recovery experienced significantly less atelectasis than those who received 0.6 [

19]. Similarly, Ashraf M et al., studied 60 patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy, who received either 40% oxygen or 90% inspired oxygen, both after endotracheal intubation and for 2 h postoperatively. 60% in the 1st group, and 76.7% in the 2nd had atelectasis as seen on a computed tomography scan [

20]. All their patients had volume-controlled ventilation with zero positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP). However, Jiang et al. (2023), who randomized 120 patients into two groups who received either 30% or 60% FiO

2 (fraction of inspired oxygen) during mechanical ventilation in a 1:1 ratio [

21] did not find any difference in the degree of atelectasis. It should be noted that none of their patients received PEEP either or were administered any recruitment maneuvers.

The mechanism of atelectasis is three-fold and these are discussed in a review [

22]. The first is the reduction of transmural pressure that keeps the alveolus open. Induction of anesthesia results in diaphragm relaxation and its caudal displacement, which removes the differential pressures in the abdomen and chest. The resulting compression atelectasis is most prominent in the dependent lung regions. The second mechanism is gas absorption. It can be caused by airway obstruction and distal air absorption and/or faster absorption of oxygen in those alveoli where perfusion is high in relation to ventilation. If these alveoli are ventilated with a high percentage of oxygen, the effect is greater. The third mechanism is impairment of pulmonary surfactant. If a bronchoscopist performs a lavage before NB, the saline washes away the surfactant. Excessive suctioning of the bronchus is another factor contributing to atelectasis. It is important to keep suctioning and any possible trauma to the minimum. The degree of atelectasis is less in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease.

3.2. Type of Anesthesia

General anesthesia is standard for parents undergoing NB. Both total intravenous anesthesia and inhalational anesthesia are appropriate, and both are shown to cause atelectasis. Unlike endobronchial ultrasound, where the preferred airway is a laryngeal mask airway (LMA), patients undergoing NB typically get an endotracheal tube, usually 1 mm diameter larger than normally used (9.0-9.5 for male and 8.0 to 8.5 for female), if the laryngeal opening allows. An ETT allows application of PEEP to preserve the lung volume and the larger bore allows procedure performance without compromising the airway area significantly. During anesthesia induction, if it can be accomplished safely, one should avoid 100 % oxygen administration to limit rapid development of atelectasis. Edmark et al. looked at atelectasis in patients undergoing induction with 100, 80, and 60% inspired oxygen [

23]. Immediately after the period of apnea, the CT scan showed that the mean atelectasis area in the basal scan was close to 10 cm

2(5.6%) in the 100% group compared to 1.3 cm

2(0.6%) and 0.3 cm

2(0.2%) in the 80 and 60% groups. Considering that there was no difference between 80 and 60% groups, 80% oxygenation seems to be appropriate. For maintenance of anesthesia, one can use air-nitrogen as part of gas mixture which will limit the early formation of atelectasis. Performance of a vital capacity maneuver followed by administration of nitrogen mixture assists in restoring the lung volumes. Ventilation with high concentrations of oxygen leads to quick reappearance of atelectasis and should be avoided.

3.3. Ventilatory Strategy

Ventilatory strategy to prevent atelectasis (VESPA) is employed at Thomas Jefferson hospital, Philadelphia, USA, and the following are its components [

16,

24]: Volume control, tidal volume (TV) of 6–8 cc/kg of ideal body weight (IBW), administering lowest tolerable inspired oxygen to aim for a saturation of about 94%, a PEEP of 8–10 cmH

2O and performance of recruitment maneuver immediately after intubation (10 consecutive breaths at a plateau pressure of 40 cmH

2O, with a PEEP of 20 cmH

2O in pressure control mode).

A second strategy that aims to limit atelectasis and excessive ventilatory chest excursions with an aim to avoid computed tomography-to-body divergence is lung navigation ventilation protocol (LNVP) [

25]. The protocol employs a dual ventilation strategy with pressure-controlled continuous mechanical ventilation and patient specific VT at 10–12 cc/kg of IBW. Like VESPA, it recommended to use minimum tolerable inspired oxygen, with a PEEP of 10–15 cmH

2O (for upper/middle lobe lesions) and 15-20 cmH

2O (for lower lobe). The recommended post-intubation recruitment consists of 4 hand-delivered breaths with 30 cmH

2O over 30 seconds or 40 cmH

2O over 40 seconds [

16]. Any experienced anesthesia provider understands that it is difficult to accurately replicate these recommendations. LNVP is shown to have a better diagnostic yield (92%

vs. 70%), although statistically not significant [

25].

Nevertheless, one should be mindful of barotrauma and hemodynamic instability the recruitment maneuvers can cause. At least in animal models it is shown that a higher margin of safety was obtained when a higher PEEP and lower driving pressure strategy was used for recruiting the lung [

26]. Addition of periodic sighs is also shown to recruit the lungs better [

27]. Hypotension is reported in 79.8% of 94 American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status I–II patients, aged 19 to 75 with scheduled spinal surgery [

28].

Grant et al. (2024) studied contribution of atelectasis to CT-to-body divergence (described as the difference between preprocedural CT scans and intraprocedural lung architecture) [

29]. They correctly recognized that standardized PEEP levels may not be appropriate for all patients due to hemodynamic and ventilatory instability. They evaluated if incremental increases in PEEP resolved atelectasis, as demonstrated by a transition from a non-aerated pattern to an aerated appearance on radial probe endobronchial ultrasound (RP-EBUS) and concluded that RP-EBUS is indeed an effective tool to monitor the resolution of atelectasis within a lung segment with increasing levels of PEEP.

3.4. Patient Positioning

Attention was drawn to the positioning related atelectasis under general anesthesia with mechanical ventilation by Klingstedt et al., (1990) [

30]. After induction in supine position, cross-sectional area for both lungs were reduced in 4/5 patients. Application of PEEP reduced but did not eliminate the atelectatic areas. Lateral positioning was similarly associated with atelectasis mainly in the dependent lung.

Paralysis and positive pressure ventilation is standard for patients undergoing NB under general anesthesia. Maintenance could be with propofol-remifentanil as part of total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) or inhalational anesthesia. At Jefferson, we typically use inhalational anesthesia along with low dose propofol infusion, with rocuronium as muscle relaxant. If the patient is appropriate for reversal and extubation, we administer sugammadex as reversal agent.

3.5. Perioperative Complications

One of the perioperative complications of NB, although infrequent, is pneumothorax is. In their retrospective analysis, Mwesigwa et, al (2024) documented a pneumothorax rate from 3.4% (in the 2022-2023 period) to 9.8% (in the 2020-2021 period). Clearly, in their analysis, the rates came down, as they gained experience. In addition, majority of them were in the upper lobe regions [

14]. In another prospective study, the investigators observed a pneumothorax rate of 4.3%, serious bleeding rate of 1.5%, and respiratory failure rate of 0.4% [

31]. 2.9% (35 of 1215) of patients experienced pneumothorax of sufficient severity (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events scale grade 2 or greater) requiring hospitalization or intervention. Yet, these rates are significantly less than percutaneous techniques (that were about 26%) [

32].

4. Anesthesia and Deployment of Endobronchial Valves

4.1. History, Pathophysiology, and Indications

Among the many factors that contribute to shortness of breath (SOB) and poor exercise tolerance in patients with emphysema, hyperinflation, especially dynamic hyperinflation, plays a central role [

33]. There is a reduction in lung recoil caused by damage to the elastic fibers, while the chest wall compliance is preserved. The end-expiratory lung volume (EELV), functional residual capacity (FRC) and total lung capacity (TLC) increase [

34]. There is also increased air trapping (as a result of small airway closure in the dependent lung areas) and [

35]dynamic hyperinflation that results from mismatch of the expiratory time constant of the lung and time between consecutive breaths. This is especially manifest during exercise because there is less time for expiration and results in more air trapping. Work of breathing increases, that will eventually lead to respiratory failure. Any superadded pulmonary infection will cause acute worsening of symptoms.

Surgical lung volume reduction was described in 1959 by Brantigan et al. and before that by Crenshaw et al. [

36,

37]. Although there was clinical improvement in one fourth of these patients, operative mortality was excessive (18%). Cooper et al. described an improvement in the technique with reduced mortality [

38].

Nevertheless, a non-surgical approach, in the form of deploying one-way endobronchial valves is becoming more popular [

39,

40,

41]. In properly selected patients, it aims to replicate the results of lung volume reduction surgery without the associated morbidity and mortality. Emphysema patients with severe hyperinflation with a suitable lobe that can be rendered atelectatic without collateral ventilation are appropriate candidates [

39]. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for endobronchial valves largely evolved from the National Emphysema Treatment Trial (NETT) [

42], the LIBERATE trial, the first multicenter randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of Zephyr Endobronchial Valve (EBV) in the USA in patients with little to no collateral ventilation, paved the way for FDA approval in Jan 2018 [

41,

43,

44,

45,

46]. In addition, both zephyr and spiration are employed for persistent air leaks.

4.2. Anesthesia Aspects

These procedures are performed either under deep sedation or preferably under general endotracheal anesthesia. Regardless of the type of anesthesia, evaluation for the appropriateness of endobronchial valve deployment by using a catheter connected to a Chartis console is required. The console measures the air flow and pressure from the occluded lobe and quantifies the collateral ventilation status [

47,

48,

49,

50].

At Jefferson health, Philadelphia, we perform these procedures under general anesthesia with an endotracheal tube (ETT). Anesthesia induction and maintenance is with intravenously administered drugs, predominantly propofol and remifentanil in the form of TIVA. When performed under GA, Chartis measurements are found to be shorter, with no difference in target lobe volume reduction following EBV treatment [

51].

Direct anesthesia related complications are uncommon. Hypotension is to be expected and phenylephrine infusion (titrated as necessary) is often required.

Both chest pain (non-cardiac origin) and pneumothorax occur frequently. Chest pain occurred more frequently with deep sedation than general anesthesia (40% Vs 18%). In the same study pneumothorax occurred in 24% of patients undersedation vs 33% under general anesthesia [

51]. The incidence is reported as 4.2–34.4% [

46,

52]. A potential drawback of general anesthesia is the increased likelihood of false positive interlobar collateral ventilation due to use of positive pressure. ventilation. Before the deployment of the last two valves, the bronchoscopist usually asks for lower PEEP and low tidal volume (TV reduction of 20-25%).

4.3. Mechanism and management of pneumothorax

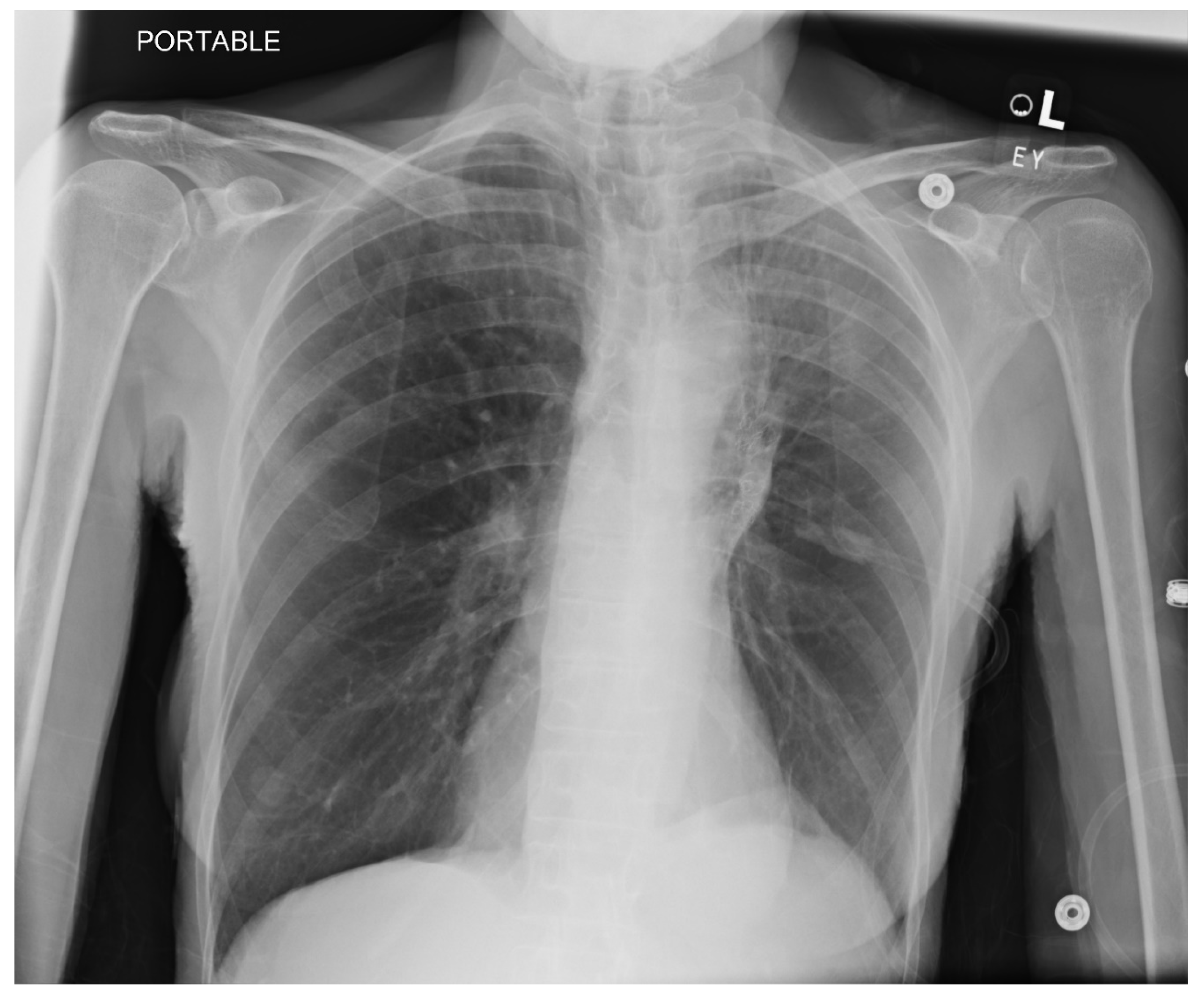

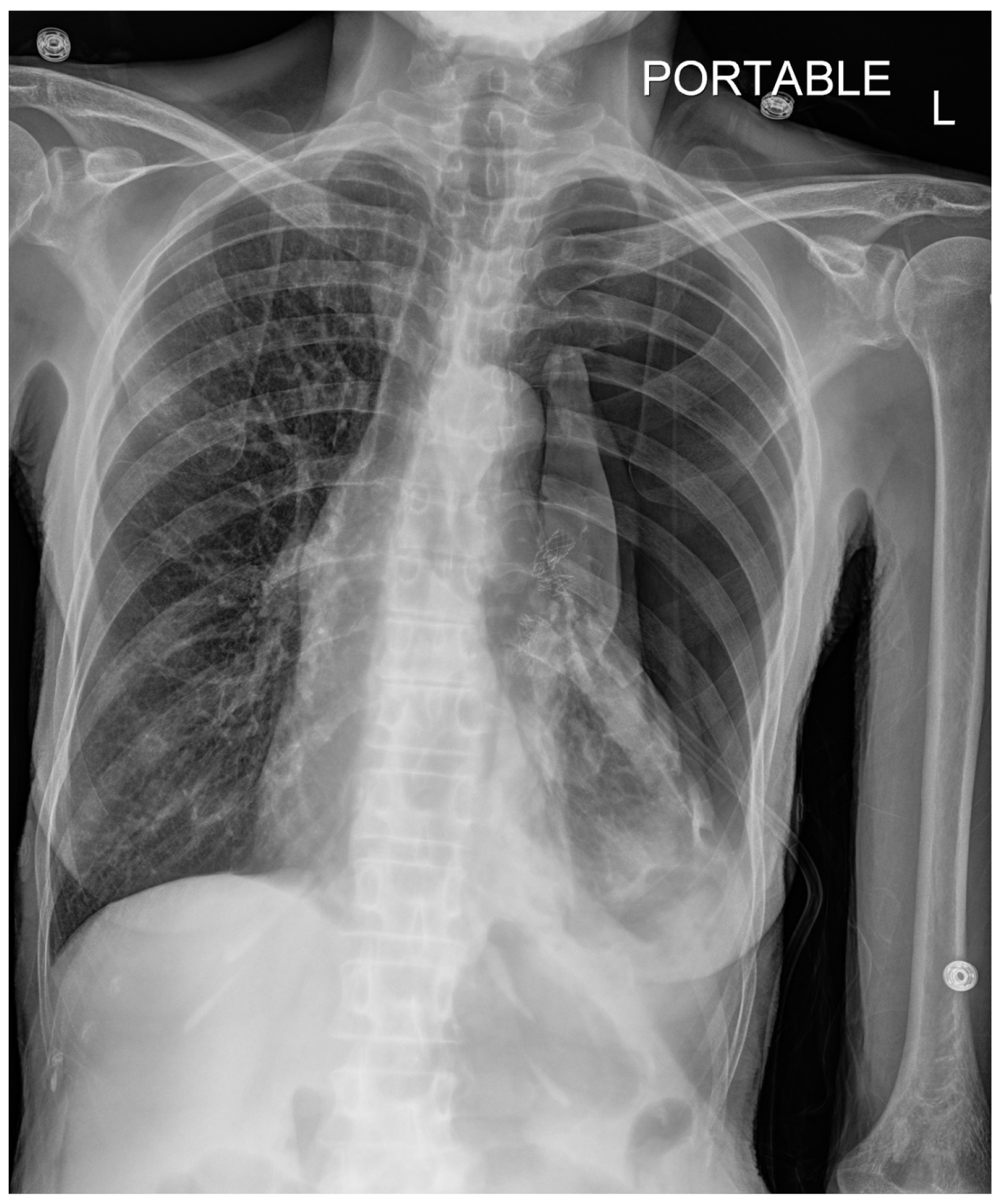

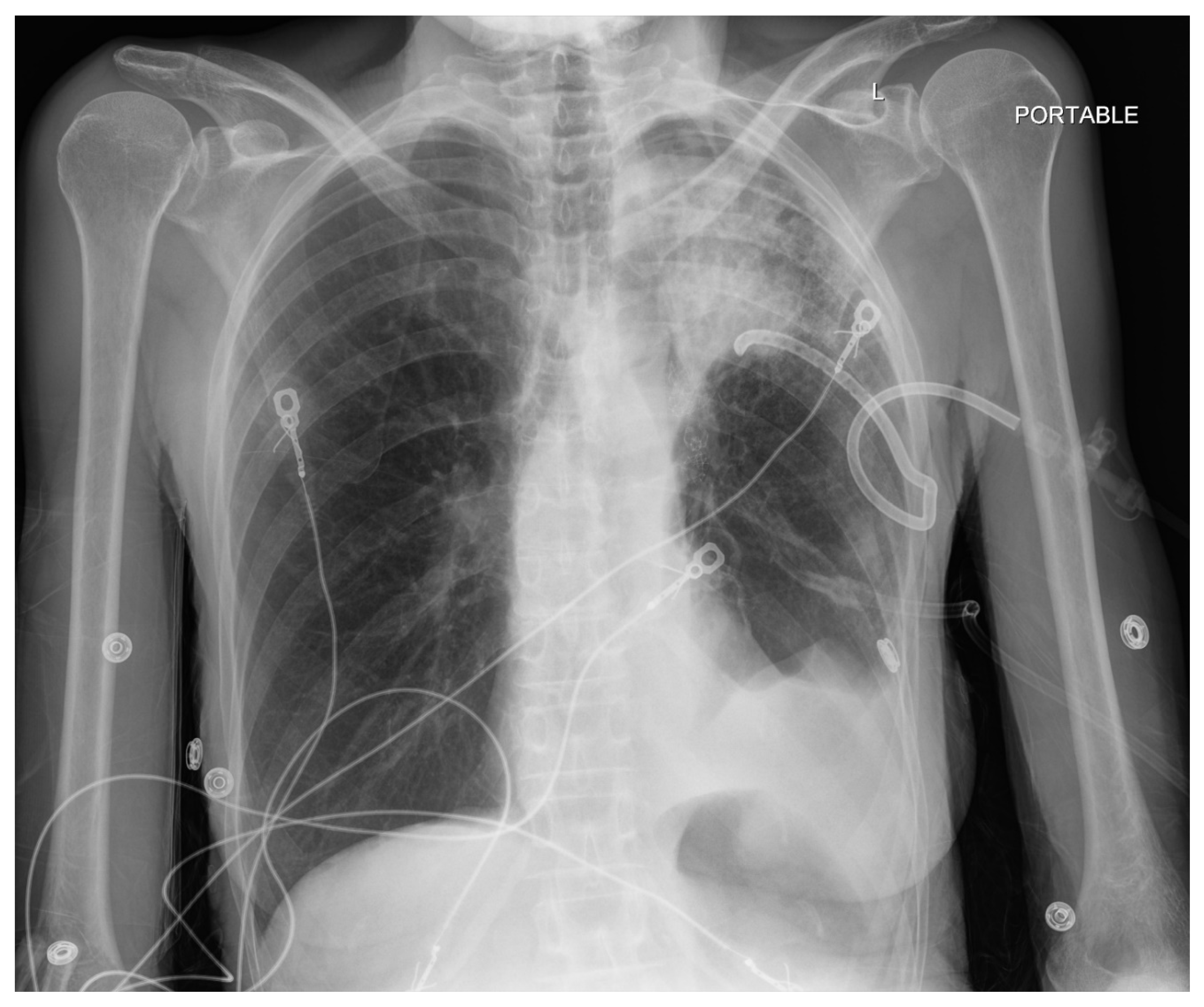

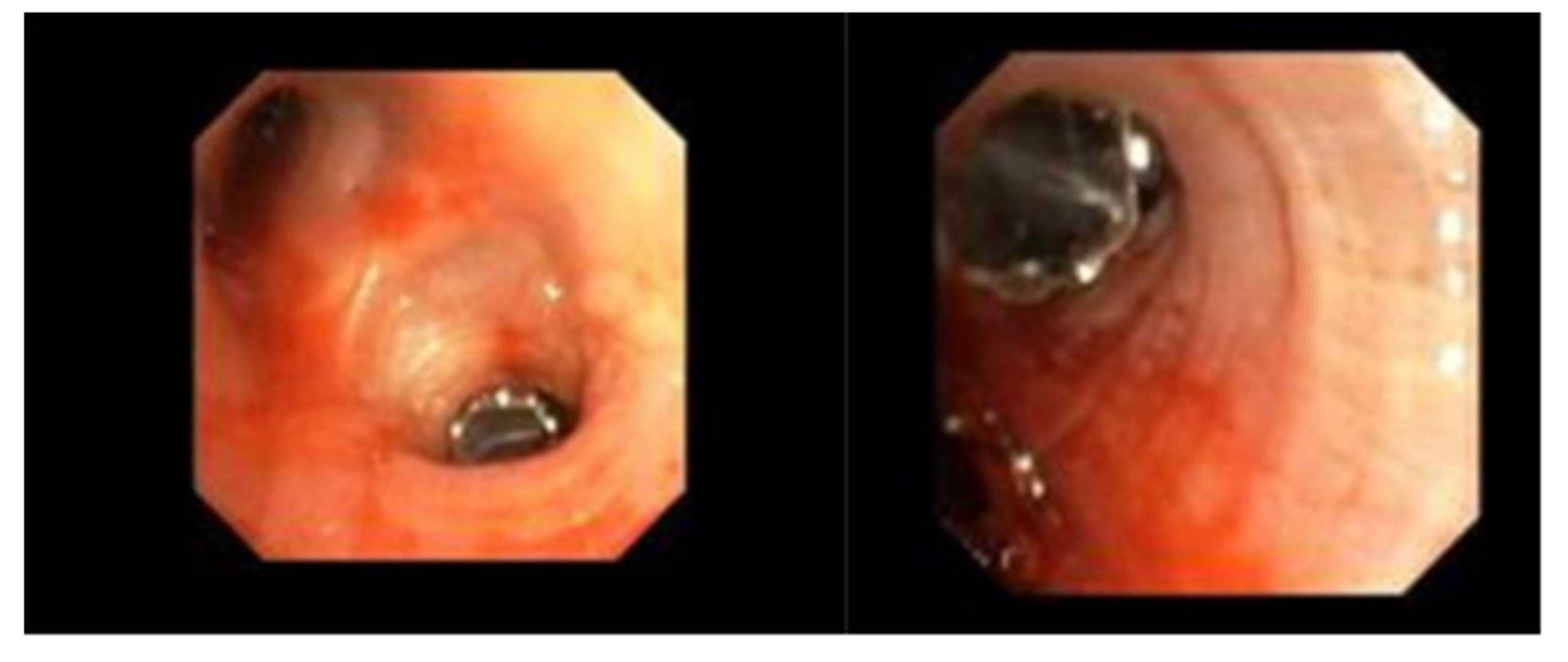

Pneumothorax (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) developing after the placement of endobronchial valve (

Figure 5) is usually managed by pulmonologists; however, anesthesia providers should be aware. Dijk et al. published their revised expert statement that addresses the issue of pneumothorax extensively [

53]. The development of pneumothorax is related to compensatory expansion of the untreated ipsilateral lobe. Such an expansion might result in the rupture of blebs, bullae, and fragile lung tissue [

54]. The bronchopleural fistula that develops leads to air leak, which can get worse and become clinically significant very quickly. Pneumothorax can also develop in the vacuum created by therapeutic lung collapse (pneumothorax ex vacuo). The air enters the potential space from the ambient tissues and blood [

55]. As there is no bronchoalveolar fistula in this situation, a chest drain is not necessary, and the pneumothorax will spontaneously resolve over time.

Pneumothorax can develop in the immediate postoperative period, in the post anesthesia care unit or within the first 3 days [

46,

56]. Valipou et al. published their management algorithm for pneumothorax [

57]. Nearly 80% of them happen in the first 48 h, 10% in about 3-5 days, and 10% after day 6 [

58,

59]. Both anesthesia providers and bronchoscopists should be particularly vigilant about the development of tension pneumothorax. Certain post procedural protocols- (cough suppression, strict bed rest, not letting to elevate the arm above shoulders) are employed at Jefferson to minimize the pneumothorax risk. Most pneumothoraces ‘s are treated conservatively with serial imaging. some may require chest tubes and rarely valve removal.

4.4. COPD Exacerbation

COPD exacerbation was reported in three of the twenty endobronchial valve insertions performed at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Woodville, South Australia, in 2018. Ten patients were performed with monitored anesthesia care, while the remaining 10 received general anesthesia with an endotracheal tube [

60]. All patients had their Chartis measurement and EBV implantation performed in one sitting. Chartis measurements took slightly longer time in patients receiving monitored anesthesia care. The authors preferred total intravenous anesthesia which has benefit of preserving hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction.

In a retrospective chart review of 202 procedures, of which 198 were performed under general anesthesia with ETT and the remaining with a laryngeal mask airway, hypotension was the most commonly observed intraprocedural adverse event [

61]. While one patient sustained severe hypotension, the remainder were considered significant or moderate. Noradrenaline, phenylephrine, and/or ephedrine were administered in most of the procedures. This was followed by desaturation. There were no deaths or unplanned ICU admission. None of the patients required cardiopulmonary resuscitation or reintubation [

61]. Other complications mentioned in the literature are acute bronchitis, pneumonia and/or lung infections developing in the first 3 months of the procedure. They are unlikely to concern the anesthesia provider [

62,

63].

5. Bronchial Thermoplasty

5.1. Preoperative Concerns and Indications

In the past few decades, radiofrequency (RF) ablation has been used as a therapeutic tool in many settings. The technique uses RF energy to produce heat and destroy the target tissue. The technology has been in use for treating cardiac arrhythmias for a long time and more recently for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. BT uses RF ablation to impact airway remodeling, including a reduction of excessive airway smooth muscle within the airway wall [

64]. It is employed in the treatment of severe asthma and involves RF energy delivery to the larger airways in more than one sitting. It is presumed to reduce the airway smooth muscle which is responsible for bronchospasm. The treatment has led to improvement in asthma control and quality of life [

65].

RF ablation should be offered only to patients with documented asthma. Some of the warnings and precautions include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bronchiectasis, recurrent respiratory infections or any other uncontrolled significant respiratory disease [

66]. RF thermal energy is typically delivered to the airway wall, as part of a series of 3 separate bronchoscopy sessions at least 3 weeks apart. FDA approved this treatment modality on April 27th, 2010, to those with severe persistent asthma, aged ≥18 years and whose asthma is not well controlled with inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting β

2-agonists. Post FDA approval trial results are now available. Chupp et al. published their 5-year experience in 2021. The study involved 284 patients that were enrolled at 27 centers [

67]. Their results indicated that treated patients experienced decreases in severe exacerbations, hospitalizations, ED visits, and corticosteroid exposure. They concluded that BT improves asthma control in different asthma phenotypes. Wijsman et al., found downregulation of gene expression of airway epithelium related to airway inflammation gene set in those treated with BT [

68].

5.2. Anesthesia Considerations

It is recommended that to undergo BT, the patient should be symptomatic (stable asthma) for 48 h, without active respiratory tract infection and no acute exacerbation of asthma for 2 weeks before BT [

69,

70]. BT can be performed under topical anesthesia with sedation or general anesthesia. A relatively large cohort of 13 severe asthma patients underwent successful RF ablation under moderate target-controlled infusion (TCI) propofol/remifentanil sedation [

71]. Both patients and bronchoscopists reported high satisfaction.

However, many bronchoscopists prefer general anesthesia. Case reports, case series and a prospective cohort trial detailing the anesthesia experience and recommendations have become available [

70,

71,

72,

73]. Anesthesia providers expect these patients to have poorly controlled asthma with abnormal pulmonary function tests. In preparation for the procedure, pulmonologists routinely administer steroids. The recommended dose is 50 mg/day of prednisolone or equivalent for 5 days, starting treatment 3 days prior to the procedure [

64]. These patients typically present to the hospital on the day of the procedure.

Both deep sedation without a definitive airway and general anesthesia with an ETT of an LMA have been used. Our experience is limited to general anesthesia with an ETT and a TIVA technique. An anticholinergic such as glycopyrrolate may be administered before induction, for its antisialogogue properties. However, it can interfere with clearing of secretions post bronchoscopy and may produce tachyarrhythmias. Administration of nebulized salbutamol and ipratropium is beneficial.

Induction is generally done with fentanyl and propofol. However, remifentanil or alfentanil are good options too. Rocuronium is an appropriate muscle relaxant, regardless of the airway planned (ETT or an LMA). A potential downside of an ETT is airway irritation and worsening of bronchospasm. Nevertheless, the procedure itself caused tracheobronchial irritation. Maintenance of anesthesia is generally with propofol and remifentanil. Any coughing during the procedure needs to be abolished and to this end it is important to monitor the neuromuscular junction. Intermittent positive pressure ventilation (IPPV) is instituted via a swivel connector to secure an airtight seal while a flexible bronchoscope is inserted. The connector also provides 360 degrees of rotation. The RF energy is delivered via a catheter introduced through the flexible bronchoscope to the desired bronchial location, in a distal to proximal direction. These procedures can take about 45-60 minutes. Muscle relaxant reversal is achieved with sugammadex.

5.3. Perioperative Complications

Bronchospasm can occur during bronchoscopy and can be managed by delivering salbutamol through the working channel of flexible video bronchoscope. Coughing and wheezing is common after the procedure and salbutamol-steroid nebulization may be sufficient.

Some of the reported complications are hypoxemia, bronchospasm, laryngospasm, atelectasis due to fibrin plugs, exacerbation of asthma, lower respiratory tract infection, and bronchial artery pseudoaneurysms [

73,

74]. Bronchial artery pseudoaneurysm caused mediastinal hematoma and hemothorax in a 66-year-old woman several days after an uneventful bronchial thermoplasty of the right lower lobe. This patient presented in respiratory distress with diffuse expiratory wheezing, tachycardia, inspiratory crackles of the right lung, and diminished breath sounds at the right base. Right upper lobe pulmonary embolism, right lower lobe consolidation, and pleural effusion with posterior mediastinal involvement were revealed in a chest CT scan. The patient was managed with IPPV in the ICU and continuing deterioration needed placement of a chest tube (in the setting of an enlarging right pleural effusion and acutely worsening anemia), that was followed by a dramatic improvement in hemodynamics. Finally, embolization of the right bronchial artery was required.

6. Newer Sedatives in Bronchoscopy

Although the popularity of conscious sedation has fallen significantly in US practice, it remains a viable and often only option in many parts of the world. In the USA, use of conscious sedation is institutional and case/procedure dependent. In our hospital certain procedures such as bronchoalveolar lavage, insertion of PleurX catheter are routinely performed under conscious sedation. Although midazolam (a benzodiazepine) and fentanyl remain the main components of conscious sedation, two new drugs, remimazolam and dexmedetomidine are gaining traction among bronchoscopists.

6.1. Remimazolam

This unique benzodiazepine was first synthesized by Glaxo Wellcome in 1990s. Since then, it has changed many hands and currently marketed by Eagle Pharmaceuticals, Inc in the USA. Described as a drug looking for an indication, there is no dearth of information on its potential role and utility including for flexible bronchoscopy [

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80].

In terms of its actions, remimazolam is no different than its parent compound midazolam. It is a short acting benzodiazepine with a rapid onset of effect and relatively short duration. The added benefit of remimazolam is its rapid offset of clinical effect, especially when used for short procedures such as bronchoalveolar lavage because of its unique elimination. It undergoes organ independent metabolism to inactive compounds, and as a result, safe in patients with liver and kidney dysfunction. Additionally, its effects are easily reversible with flumazenil. Studies have reported utility of remimazolam both during rigid and flexible bronchoscopy.

In a prospective randomized controlled trial, Pan et al. (2022) compared remimazolam-flumazenil (Group R) and propofol (Group P) for rigid bronchoscopy [

81]. A total of 34 patients were enrolled in this study. They found that Group R recovered from anesthesia much faster than Group P (140 ± 52 Vs 374 ± 195 s). It should be noted that, as of now, there is no agent that can reverse the effects of propofol. Patients in both groups were paralyzed with rocuronium. Re-sedation after flumazenil reversal is a possibility and needs to be watched for [

82].

In a prospective, double-blind, randomized, multicenter, parallel group trial, that was performed at 30 US sites, remimazolam was administered under the supervision of a pulmonologist for flexible bronchoscopy with a success rate of 80.6%, while the success rates were 4.8% in the placebo arm, and 32.9% in the midazolam arm [

83]. In this study, the efficacy and safety of remimazolam for sedation during flexible bronchoscopy were compared with placebo and open-label midazolam. In an another a single-center, randomized controlled study, 51 patients were assigned to the midazolam group and 49 to the remimazolam group [

84]. These patients underwent flexible bronchoscopy, and local anesthesia was also used to suppress coughing. While the physician satisfaction and willingness to repeat the procedure were similar in both groups, remimazolam group exhibited shorter time to reach peak sedation and from the end of the procedure to full alertness. Similar results are reported in meta-analysis [

85,

86].

6.2. Dexmedetomidine

Dexmedetomidine is a selective α-2 adrenoceptor agonist that displays sedative, analgesic, anxiolytic, sympatholytic, and opioid-sparing properties [

87]. Anesthesia providers have used it for decades as a sedative and adjuvant with other anesthetics and analgesics. It is shown to have opioid sparing properties. Uniquely it allows transition from awake to sleepy to awake states and this property is useful in procedures such as awake craniotomy [

88,

89]. It produces minimal respiratory depression, and this quality is useful in providing safe conscious sedation for flexible bronchoscopy. Slow onset of clinical effect, along with bradycardia and hypotension are some of the common drawbacks.

Wu et al. (2020) performed a retrospective chart review of all patients undergoing flexible bronchoscopy with moderate sedation [

90]. Compared to those who received midazolam-propofol-fentanyl, patients sedated with dexmedetomidine-propofol-fentanyl showed higher safety with fewer procedural disruptions caused by cough or body movement. Dexmedetomidine was administered as a bolus of 0.7 μg/kg dexmedetomidine for 10 min, followed by a maintenance dose of 0.07 μg/kg/h. However, all patients were also administered 2 mL of 2% lidocaine and suctioned as needed to limit coughing. If cough persisted or sedation was associated with body movements, 25–50 μg fentanyl was administered.

In a randomized controlled trial, Pertzov et al. (2022), monitored for the number of desaturation events (primary outcome) and transcutaneous Pco2 level, hemodynamic adverse events and physician and patient satisfaction (secondary events) [

91]. After receiving a loading dose of fentanyl 1 mcg/kg and midazolam 1 mg, patients in the dexmedetomidine group were given a loading dose of 1 mcg/kg over 15 min followed by a continuous intravenous infusion at a rate of 0.5 mcg/kg/h, while the propofol group received 0.5–1 mg/kg for induction over 1 min followed by a maintenance infusion in a dose of 100–200 mcg/kg/min. They did not find any differences in oxygen saturation and transcutaneous CO2 levels between the two groups. However, dexmedetomidine group required a significantly higher number of rescue boluses, due to inadequate sedation and was associated with a higher rate of adverse events.

When used as a sedative along with local anesthesia, dexmedetomidine provided better patient cooperation and comfort [

92]. In a meta-analysis, Guo et al. (2023) found that dexmedetomidine reduces the incidence of hypoxemia and tachycardia during bronchoscopy but is more likely to provoke bradycardia [

93].

Dexmedetomidine is also used as a nebulizer. In this form, it increases patient comfort, reduces cough, improves tolerance, and associated with shorter recovery time compared to intravenous route [

94]. In addition, it can relieve bronchospasm. In a double-blind randomized controlled trial, (nebulized dexmedetomidine vs nebulized saline) involving 100 patients, nebulized dexmedetomidine group had limited efficacy in terms of reducing coughing compared to nebulized saline [

95]. The procedures were mainly bronchoalveolar lavage and diagnostic bronchoscopy. In yest another study, Grover et al. (2024) demonstrated that nebulized dexmedetomidine has insignificant topical action in reduction of cough episodes, when compared to normal saline in diagnostic flexible bronchoscopy [

96].

A summary of the anesthetic management procedures discussed here can be found in

Table 1.

7. Conclusions

We have attempted to provide a concise description of both anesthesia and procedural aspects of some of the newer bronchoscopic procedures. Interventional pulmonology is more and more recognized as a distinct specialty and additional therapeutic procedures such as LASER cautery, argon plasma coagulation, photodynamic therapy are increasingly performed, in addition to rigid bronchoscopy. As an indispensable team member, anesthesia provider plays a crucial role. In some institutions, medical thoracoscopy is performed with general anesthesia along with single lung ventilation; but usually it is done under moderate sedation.

Anesthesia requirements of electromagnetic navigational bronchoscopy are unique and aim to limit the development of atelectasis to preserve lung volumes. Deployment of endobronchial valves is associated with a high incidence of pneumothorax, and this is inevitable. Bronchial thermoplasty might be getting less popular than it was. Among the newer sedatives, remimazolam is showing some promise, while dexmedetomidine is unlikely to change the landscape of bronchoscopy conscious sedation.

References

- Dhooria S, Chaudhary S, Ram B, Sehgal IS, Muthu V, Prasad KT, et al. A Randomized Trial of Nebulized Lignocaine, Lignocaine Spray, or Their Combination for Topical Anesthesia During Diagnostic Flexible Bronchoscopy. Chest. 2020, 157, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islamitabar S, Gholizadeh M, Rakhshani MH, Kazemzadeh A, Tadayonfar M. Comparison of Nebulized Lidocaine and Intratracheally Injected (Spray-as-you-go) Lidocaine in Pain and Cough Reduction during Bronchoscopy. Tanaffos. 2022, 21, 348–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lev R, Rosen P. Prophylactic lidocaine use preintubation: A review. J Emerg Med. 1994, 12, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yukioka H, Yoshimoto N, Nishimura K, Fujimori M. Intravenous lidocaine as a suppressant of coughing during tracheal intubation. Anesth Analg. 1985, 64, 1189–92. [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, He T, Liu MX, Han SQ, Wu ZA, Hao W, et al. The effect of intravenous lidocaine on propofol dosage in painless bronchoscopy of patients with COPD. Front Surg. 2022, 9, 872916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FASHP BDH PharmD, DABAT, FAACT. ALiEM. 2013 [cited 2024 Aug 26]. Safe dosing of nebulized lidocaine. Available from: https://www.aliem.com/safe-dosing-of-nebulized-lidocaine/.

- Pfeifer HJ, Greenblatt DJ, Koch-Weser J. Clinical use and toxicity of intravenous lidocaine: A report from the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program. Am Heart J. 1976, 92, 168–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown DL, Skiendzielewski JJ. Lidocaine toxicity. Annals of emergency medicine. 1980, 9, 627–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welter KJ, Gordon S, Snyder P, Martin B. A case report of an 18-year-old receiving nebulized lidocaine for treatment of COVID-19 cough. Heart Lung. 2023, 57, 140–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinn WM, Zavala DC, Ambre J. Plasma Levels of Lidocaine Following Nebulized Aerosol Administration. Chest. 1977, 71, 346–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qanash S, Hakami OA, Al-Husayni F, Gari AG. Flexible Fiberoptic Bronchoscopy: Indications, Diagnostic Yield and Complications. Cureus 12, e11122.

- Lung Cancer Statistics | How Common is Lung Cancer? [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 26]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/lung-cancer/about/key-statistics.html.

- CDC. Lung Cancer. 2024 [cited 2024 Aug 26]. Screening for Lung Cancer. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/lung-cancer/screening/index.html.

- Mwesigwa NW, Tentzeris V, Gooseman M, Qadri S, Maxine R, Cowen M. Electromagnetic Navigational Bronchoscopy Learning Curve Regarding Pneumothorax Rate and Diagnostic Yield. Cureus 16, e58289.

- Cicenia J, Avasarala SK, Gildea TR. Navigational bronchoscopy: a guide through history, current use, and developing technology. J Thorac Dis. 2020, 12, 3263–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan A, Bashour SI, Casal RF. Preventing atelectasis during bronchoscopy under general anesthesia. J Thorac Dis. 2023, 15, 3443–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedenstierna G, Rothen HU. Atelectasis formation during anesthesia: causes and measures to prevent it. J Clin Monit Comput. 2000, 16, 329–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar AES, Sabath BF, Eapen GA, Song J, Marcoux M, Sarkiss M, et al. Incidence and Location of Atelectasis Developed During Bronchoscopy Under General Anesthesia: The I-LOCATE Trial. Chest. 2020, 158, 2658–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park M, Jung K, Sim WS, Kim DK, Chung IS, Choi JW, et al. Perioperative high inspired oxygen fraction induces atelectasis in patients undergoing abdominal surgery: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Anesth. 2021, 72, 110285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandr AM, Atallah HA, Sadik SA, Mohamemd MS. The effect of inspired oxygen concentration on postoperative pulmonary atelectasis in obese patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized-controlled double-blind study. Res Opin Anesth Intensive Care. 2019, 6, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang Z, Liu S, Wang L, Li W, Li C, Lang F, et al. Effects of 30% vs. 60% inspired oxygen fraction during mechanical ventilation on postoperative atelectasis: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2023, 23, 265. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan M, Kavanagh BP, Warltier DC. Pulmonary Atelectasis: A Pathogenic Perioperative Entity. Anesthesiology. 2005, 102, 838–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmark L, Kostova-Aherdan K, Enlund M, Hedenstierna G. Optimal oxygen concentration during induction of general anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2003, 98, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahuddin M, Sarkiss M, Sagar AES, Vlahos I, Chang CH, Shah A, et al. Ventilatory Strategy to Prevent Atelectasis During Bronchoscopy Under General Anesthesia: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial (Ventilatory Strategy to Prevent Atelectasis -VESPA- Trial). Chest. 2022, 162, 1393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhadra K, Setser RM, Condra W, Pritchett MA. Lung Navigation Ventilation Protocol to Optimize Biopsy of Peripheral Lung Lesions. J Bronchol Interv Pulmonol. 2022, 29, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Fernández J, Canfrán S, de Segura IAG, Suarez-Sipmann F, Aguado D, Hedenstierna G. Pressure safety range of barotrauma with lung recruitment manoeuvres: a randomised experimental study in a healthy animal model. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2013, 30, 567–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li C, Ren Q, Li X, Han H, Peng M, Xie K, et al. Effect of sigh in lateral position on postoperative atelectasis in adults assessed by lung ultrasound: a randomized, controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2022, 22, 215. [Google Scholar]

- Min JY, Chang HJ, Kim SJ, Cha SH, Jeon JP, Kim CJ, et al. Prediction of hypotension during the alveolar recruitment maneuver in spine surgery: a prospective observational study. Eur J Med Res. 2023, 28, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senyei GD, Sagar AES, Tran B, Shah A, Miller R, Patel N, et al. Incremental Application of Positive End-Expiratory Pressure for the Evaluation of Atelectasis During RP-EBUS and Bronchoscopy (I-APPEAR). J Bronchol Interv Pulmonol. 2024, 31, e0969. [Google Scholar]

- Klingstedt C, Hedenstierna G, Lundquist H, Strandberg A, Tokics L, Brismar B. The influence of body position and differential ventilation on lung dimensions and atelectasis formation in anaesthetized man. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1990, 34, 315–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folch EE, Pritchett MA, Nead MA, Bowling MR, Murgu SD, Krimsky WS, et al. Electromagnetic Navigation Bronchoscopy for Peripheral Pulmonary Lesions: One-Year Results of the Prospective, Multicenter NAVIGATE Study. J Thorac Oncol Off Publ Int Assoc Study Lung Cancer. 2019, 14, 445–58. [Google Scholar]

- Huo YR, Chan MV, Habib AR, Lui I, Ridley L. Pneumothorax rates in CT-Guided lung biopsies: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors. Br J Radiol. 2020, 93, 20190866. [Google Scholar]

- Jantz, MA. Help Me, I Need Air: Patient Satisfaction after Endobronchial Valve Placement for Emphysema. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021, 18, 30–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, GJ. Pulmonary hyperinflation a clinical overview. Eur Respir J. 1996, 9, 2640–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi A, Aisanov Z, Avdeev S, Di Maria G, Donner CF, Izquierdo JL, et al. Mechanisms, assessment and therapeutic implications of lung hyperinflation in COPD. Respir Med. 2015, 109, 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crenshaw GL, Rowles DF. Surgical management of pulmonary emphysema. J Thorac Surg. 1952, 24, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brantigan OC, Mueller E, Kress MB. A surgical approach to pulmonary emphysema. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1959, 80 Part 2, 194–206. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JD, Trulock EP, Triantafillou AN, Patterson GA, Pohl MS, Deloney PA, et al. Bilateral pneumectomy (volume reduction) for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995, 109, 106–16, discussion 116-119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klooster K, Slebos DJ. Endobronchial Valves for the Treatment of Advanced Emphysema. Chest. 2021, 159, 1833–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman JE, Vanfleteren LEGW, Rikxoort EM van, Klooster K, Slebos DJ. Endobronchial valves for severe emphysema. Eur Respir Rev [Internet]. 2019 Jun 30 [cited 2024 Aug 28];28(152). Available from: https://err.ersjournals.com/content/28/152/180121.

- Endobronchial Valve Therapy in Patients with Homogeneous Emphysema. Results from the IMPACT Study | American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 28]. Available from: https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.201607-1383OC.

- Criner GJ, Cordova F, Sternberg AL, Martinez FJ. The National Emphysema Treatment Trial (NETT). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011, 184, 763–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premarket Approval (PMA) [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 28]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpma/pma.cfm?id=P180002.

- Klooster K, ten Hacken NHT, Hartman JE, Kerstjens HAM, van Rikxoort EM, Slebos DJ. Endobronchial Valves for Emphysema without Interlobar Collateral Ventilation. N Engl J Med. 2015, 373, 2325–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp SV, Slebos DJ, Kirk A, Kornaszewska M, Carron K, Ek L, et al. A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial of Zephyr Endobronchial Valve Treatment in Heterogeneous Emphysema (TRANSFORM). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017, 196, 1535–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criner GJ, Sue R, Wright S, Dransfield M, Rivas-Perez H, Wiese T, et al. A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial of Zephyr Endobronchial Valve Treatment in Heterogeneous Emphysema (LIBERATE). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018, 198, 1151–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster TD, Klooster K, McNamara H, Shargill NS, Radhakrishnan S, Olivera R, et al. An adjusted and time-saving method to measure collateral ventilation with Chartis. ERJ Open Res [Internet]. 2021 Jul 1 [cited 2024 Aug 28];7(3). Available from: https://openres.ersjournals.com/content/7/3/00191-2021.

- Herth FJF, Eberhardt R, Gompelmann D, Ficker JH, Wagner M, Ek L, et al. Radiological and clinical outcomes of using ChartisTM to plan endobronchial valve treatment. Eur Respir J. 2013, 41, 302–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herth FJF, Slebos DJ, Criner GJ, Valipour A, Sciurba F, Shah PL. Endoscopic Lung Volume Reduction: An Expert Panel Recommendation—Update 2019. Respir Int Rev Thorac Dis. 2019, 97, 548–57. [Google Scholar]

- Omballi M, Noori Z, Alanis RV, Lukken Imel R, Kheir F. Chartis-guided Endobronchial Valves Placement for Persistent Air Leak. J Bronchol Interv Pulmonol. 2023, 30, 398–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welling JBA, Klooster K, Hartman JE, Kerstjens HAM, Franz I, Struys MMRF, et al. Collateral Ventilation Measurement Using Chartis: Procedural Sedation vs General Anesthesia. Chest. 2019, 156, 984–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster TD, Klooster K, Ten Hacken NHT, van Dijk M, Slebos DJ. Endobronchial valve therapy for severe emphysema: an overview of valve-related complications and its management. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2020, 14, 1235–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk M, Sue R, Criner GJ, Gompelmann D, Herth FJF, Hogarth DK, et al. Expert Statement: Pneumothorax Associated with One-Way Valve Therapy for Emphysema: 2020 Update. Respiration. 2021, 100, 969–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen KR, Cerfolio RJ. Decision making in the management of secondary spontaneous pneumothorax in patients with severe emphysema. Thorac Surg Clin. 2009, 19, 233–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodring JH, Baker MD, Stark P. Pneumothorax ex vacuo. Chest. 1996, 110, 1102–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gompelmann D, Lim H ju, Eberhardt R, Gerovasili V, Herth FJ, Heussel CP, et al. Predictors of pneumothorax following endoscopic valve therapy in patients with severe emphysema. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016, 11, 1767–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valipour A, Slebos DJ, de Oliveira HG, Eberhardt R, Freitag L, Criner GJ, et al. Expert statement: pneumothorax associated with endoscopic valve therapy for emphysema--potential mechanisms, treatment algorithm, and case examples. Respir Int Rev Thorac Dis. 2014, 87, 513–21. [Google Scholar]

- Skowasch D, Fertl A, Schwick B, Schäfer H, Hellmann A, Herth FJF, et al. A Long-Term Follow-Up Investigation of Endobronchial Valves in Emphysema (the LIVE Study): Study Protocol and Six-Month Interim Analysis Results of a Prospective Five-Year Observational Study. Respir Int Rev Thorac Dis. 2016, 92, 118–26. [Google Scholar]

- Slebos DJ, Shah PL, Herth FJF, Valipour A. Endobronchial Valves for Endoscopic Lung Volume Reduction: Best Practice Recommendations from Expert Panel on Endoscopic Lung Volume Reduction. Respiration. 2017, 93, 138–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiruvenkatarajan V, Maycock T, Grosser D, Currie J. Anaesthetic management for endobronchial valve insertion: lessons learned from a single centre retrospective series and a literature review. BMC Anesthesiol. 2018, 18, 206. [Google Scholar]

- Roodenburg SA, Barends CRM, Krenz G, Zeedijk EJ, Slebos DJ. Safety and Considerations of the Anaesthetic Management during Bronchoscopic Lung Volume Reduction Treatments. Respiration. 2023, 102, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciurba FC, Ernst A, Herth FJF, Strange C, Criner GJ, Marquette CH, et al. A randomized study of endobronchial valves for advanced emphysema. N Engl J Med. 2010, 363, 1233–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herth FJF, Noppen M, Valipour A, Leroy S, Vergnon JM, Ficker JH, et al. Efficacy predictors of lung volume reduction with Zephyr valves in a European cohort. Eur Respir J. 2012, 39, 1334–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonta PI, Chanez P, Annema JT, Shah PL, Niven R. Bronchial Thermoplasty in Severe Asthma: Best Practice Recommendations from an Expert Panel. Respir Int Rev Thorac Dis. 2018, 95, 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Asthma control during the year after bronchial thermoplasty—PubMed [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 29]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17392302/.

- Dombret MC, Alagha K, Boulet LP, Brillet PY, Joos G, Laviolette M, et al. Bronchial thermoplasty: a new therapeutic option for the treatment of severe, uncontrolled asthma in adults. Eur Respir Rev. 2014, 23, 510–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chupp G, Kline JN, Khatri SB, McEvoy C, Silvestri GA, Shifren A, et al. Bronchial Thermoplasty in Patients With Severe Asthma at 5 Years: The Post-FDA Approval Clinical Trial Evaluating Bronchial Thermoplasty in Severe Persistent Asthma Study. Chest. 2022, 161, 614–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijsman PC, Goorsenberg AWM, Ravi A, d’Hooghe JNS, Dierdorp BS, Dekker T, et al. Airway Inflammation Before and After Bronchial Thermoplasty in Severe Asthma. J Asthma Allergy. 2022, 15, 1783–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-García J, Cheng G, Castro M. Bronchial thermoplasty: an update for the interventional pulmonologist. AME Medical Journal. 2018, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Dattatri R, Garg R, Madan K, Hadda V, Mohan A. Anesthetic considerations for bronchial thermoplasty in patients of severe asthma: A case series. Lung India Off Organ Indian Chest Soc. 2020, 37, 536–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- d’Hooghe JNS, Eberl S, Annema JT, Bonta PI. Propofol and Remifentanil Sedation for Bronchial Thermoplasty: A Prospective Cohort Trial. Respir Int Rev Thorac Dis. 2017, 93, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal S, Hoda W, Mittal S, Madan K, Hadda V, Mohan A, et al. Anesthesia and anesthesiologist concerns for bronchial thermoplasty. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019, 13, 78–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aizawa M, Ishihara S, Yokoyama T, Katayama K. Feasibility and safety of general anesthesia for bronchial thermoplasty: a description of early 10 treatments. J Anesth. 2018, 32, 443–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen DV, Murin S. Bronchial Artery Pseudoaneurysm With Major Hemorrhage After Bronchial Thermoplasty. Chest. 2016, 149, e95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudra BG, Singh PM. Remimazolam: The future of its sedative potential. Saudi J Anaesth. 2014, 8, 388–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brohan M, Brohan J, Goudra B. Remimazolam and Its Place in the Current Landscape of Procedural Sedation and General Anesthesia. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessai S, Ninave S, Bele A. The Rise of Remimazolam: A Review of Pharmacology, Clinical Efficacy, and Safety Profiles. Cureus 16, e57260.

- Hu Q, Liu X, Wen C, Li D, Lei X. Remimazolam: An Updated Review of a New Sedative and Anaesthetic. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2022, 16, 3957–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpatrick, GJ. Remimazolam: Non-Clinical and Clinical Profile of a New Sedative/Anesthetic Agent. Front Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 690875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sneyd JR, Gambus PL, Rigby-Jones AE. Current status of perioperative hypnotics, role of benzodiazepines, and the case for remimazolam: a narrative review. Br J Anaesth. 2021, 127, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan Y, Chen M, Gu F, Chen J, Zhang W, Huang Z, et al. Comparison of Remimazolam-Flumazenil versus Propofol for Rigid Bronchoscopy: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Med. 2022, 12, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto T, Kurabe M, Kamiya Y. Re-sleeping after reversal of remimazolam by flumazenil. J Anesth. 2021, 35, 322–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastis NJ, Yarmus LB, Schippers F, Ostroff R, Chen A, Akulian J, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Remimazolam Compared With Placebo and Midazolam for Moderate Sedation During Bronchoscopy. Chest. 2019, 155, 137–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim SH, Cho JY, Kim M, Chung JM, Yang J, Seong C, et al. Safety and efficacy of remimazolam compared with midazolam during bronchoscopy: a single-center, randomized controlled study. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 20498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Zhao C, Tang YX, Liu JT. Efficacy and safety of remimazolam in bronchoscopic sedation: A meta-analysis. World J Clin Cases. 2024, 12, 1120–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou YY, Yang ST, Duan KM, Bai ZH, Feng YF, Guo QL, et al. Efficacy and safety of remimazolam besylate in bronchoscopy for adults: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, positive-controlled clinical study. Front Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1005367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Dexmedetomidine: present and future directions. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2019, 72, 323–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mm G, S D, Md C, C C, Cd M, Gm H, et al. Anesthetic approach to high-risk patients and prolonged awake craniotomy using dexmedetomidine and scalp block. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol [Internet]. 2014 Jul [cited 2024 Sep 3];26(3). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24064713/.

- Raimann F, Adam E, Strouhal U, Zacharowski K, Seifert V, Forster MT. Dexmedetomidine as adjunct in awake craniotomy—improvement or not? Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2020, 52, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu SH, Lu DV, Hsu CD, Lu IC. The Effectiveness of Low-dose Dexmedetomidine Infusion in Sedative Flexible Bronchoscopy: A Retrospective Analysis. Medicina (Mex). 2020, 56, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertzov B, Krasulya B, Azem K, Shostak Y, Izhakian S, Rosengarten D, et al. Dexmedetomidine versus propofol sedation in flexible bronchoscopy: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pulm Med. 2022, 22, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Lekatsas G, Lambiri I, Prinianakis G, Michelakis S, Tzanakis N, Pitsidianakis G, et al. The use of dexmedetomidine as a sedative during flexible bronchoscopy. Eur Respir J [Internet]. 2016 Sep 1 [cited 2024 Sep 3];48(suppl 60). Available from: https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/48/suppl_60/PA764.

- Guo Q, An Q, Zhao L, Wu M, Wang Y, Guo Z. Safety and Efficacy of Dexmedetomidine for Bronchoscopy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2023, 12, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antony T, Acharya VK, Acharya PR. Effectiveness of nebulized dexmedetomidine as a premedication in flexible bronchoscopy in Indian patients -a prospective, randomized, double-blinded study. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2023, 33 101111.

- Lalwani LK, Singh PK, Chaudhry D. Nebulized Dexmedetomidine Prior to Flexible Bronchoscopy in Reducing Procedural Cough Episodes: A Randomized, Clinical Trial. Eur Respir J [Internet]. 2023 Sep 9 [cited 2024 Sep 3];62(suppl 67). Available from: https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/62/suppl_67/PA5221.

- Grover J, Garg M, Singh PK, Verma S, Chaudhry D, Saxena P, et al. Nebulized dexmedetomidine prior to flexible bronchoscopy in reducing procedural cough episodes a randomized double blind clinical trial. (NCT: CTRI/2022/07/044389, NICOBAR group of investigators). Indian J Tuberc [Internet]. 2024 Apr 3 [cited 2024 Sep 3]; Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0019570724000647.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).