1. Introduction

Other-centred approaches require reflection and change. Current scientific advances and interactions between people in our society and with other cultures in an increasingly globalised world, with different ways of understanding and dealing with illness, generate a necessary rethinking and paradigm shift in the clinical and care relationship. We are moving towards a concept of holistic care that has significantly changed our understanding of life and our ability to influence it.

It is necessary to clarify the concept of the person as a relational being who can take responsibility for caring for and accompanying them in this process. Human beings live in constant interaction and do not exist in isolation, and these interactions arise from a series of needs that manifest themselves throughout life. The ethics of care rejects universal principles to focus on the concrete relationships between people from their most basic beginnings, considering rationality, affect, and emotion [

1].

There is no doubt that vocation is essential for the exercise of a profession. Vocation is not an innate fact that a person must have to exercise a profession; instead, it is a matter of having certain aptitudes to carry out the exercise required of a person practising a profession. With sensitivity to the suffering of the sick, one can be a good health professional or teacher. The same applies to other professions [

2].

It is important to emphasise that, as Nortjé et al. [

3] show, some essential virtues are expected to be developed in a healthcare professional, such as compassion (actively understanding another's perspective in a positive way about their well-being, with a deep understanding of their pain or difficulties), the virtue of discernment (which includes the ability to make decisions free from the undue influence of personal interests or superficial concerns). Another is trust (the assertive virtue, which implies the certainty that another will act with the right intentions and according to appropriate moral standards). For example, trust is an important element in choosing a health professional). All these virtues are essential components in the ethical development of a professional.

Martins et al. [

4] argue that the development of moral competence is as important for nursing and medical students as any other professional competence. According to these authors, the curricula of both professions should include ethics education to develop moral competence and evaluate different approaches and methods of teaching ethics in the curricula. Regarding physiotherapy, Marqués-Sule et al. [

5] argue that ethics education should be included in each year of university studies, even if it is transversal in each subject. Ethics is a fundamental pillar in the clinical training of physiotherapy students.

Sympathy, empathy, altruism, and compassion are not isolated ideas but are intrinsically and intimately related to each other, and the healthcare professional should act with a compassionate attitude, which is fundamental and essential to care and this must also be trained during academic training [

6]. According to Vilca Golac [

7], the vocation of a nursing student is significant in terms of empathy, sensitivity and social commitment. Training empathy skills in the nursing student significantly improves their compassionate capacity [

8]. The ethics of care should be understood as a commitment, duty and responsibility that the professional acquires from others. They need to have empathy and respect to make the patient feel safe and secure throughout the care process [

9]. Regarding the attitudes that a physical therapist should have in order to improve their ethical thinking, Mármol-López et al. [

10] argue that training in ethics for physical therapists should be improved if it focuses on improving the attitudes of the professional since nowadays it focuses more on the bioethical principles of beneficence and non-maleficence and less on the autonomy of the patient.

1.1. Vocation for Care

Anaya-Requejo [

11] shows that, in case of nursing students, there is no significant relationship between socio-demographic variables such as age, gender, marital status or family income and the fact of having a vocation to study nursing. However, Limanta-Barrios [

12] points out that there is a relationship between socio-personal factors and the vocation to study nursing.

According to Arenas-Ramírez et al. [

13], the vocation level of nursing students varies from semester to semester. This has to do with the fact that there is a close relationship between happiness and vocation and that it conditions the professional performance of a future nurse. Van den Boogaard et al. [

14] also agree that at the beginning of nursing education, students feel good about nursing, caring and even being empathic. However, these positive experiences decrease significantly over the months of training. Therefore, it is necessary to develop psychological intervention programmes to strengthen the vocation of nursing students, such as Psychological First Aid (PFA), which has been shown to help improve students' self-efficacy, resilience, and professional competence [

15].

Therefore, the authors argue that vocational levels should continue to be studied to ensure a better quality of life in healthcare. Akhter et al. [

16] agree with this last idea as they insist that teachers or nurse educators have an essential role in promoting vocation in students. It is necessary to rethink nursing education if we want to train professionals who are not only technically focused on curing disease but also have critical and ethical thinking skills [

17].

Regarding students' choice of the physiotherapy discipline, Fuente-Vidal et al. [

18] show in their results that the predominant reason for a student to study physiotherapy is to help and care for others. Male students were more motivated by the fact that physiotherapy is closely related to sport, whereas female students were more motivated by altruism and scientific interest in physiotherapy.

1.2. The Importance of Soft Skills in Training a Care Professional: Empathy and Assertiveness

Jia-Ru et al. [

19] report that the empathy development scores of nursing students worldwide are fairly acceptable but need to be further enhanced because improving and training empathy in future nursing professionals is beneficial for improving the quality of clinical care and the quality of life of patients. As argued by Moudatsou et al. [

20], further empathy training for students is paramount because better empathy development contributes to good professional nurse-patient behaviour, which has a marked positive impact on patients' overall well-being.

Regarding this idea, Lopes and Nihei [

21] show that the level of burnout among nursing students is low. However, the percentages of emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation are high. These results may eventually lead to burnout syndrome. In the context of the recent pandemic, Taylor et al. [

22] suggest that it is important to work on empathy and resilience in nursing students themselves.

Overall, the interventions that improve empathy levels among nursing students and are most effective are immersive simulations and experiences with vulnerable patients [

23]. Simulation is a feasible teaching method for improving communication, empathy and self-efficacy. The pedagogical effectiveness of experiential training among students has been demonstrated at the cognitive, emotional and empathic levels, as immersive simulations help students shape their empathic development [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28].

Communication skills training and education should be well integrated into nursing education and be feasible, acceptable, and effective [

29]. Nursing students improve not only their professional knowledge but also their communication skills during clinical practice [

30]. Therefore, training in humanised care and empathy is necessary to educate future nurses [

31].

Blanton et al. [

32] stress the importance of incorporating the humanities and the arts for empathy training, such as art, literature or film, in the empathy training of future physiotherapists. Strohbehn et al. [

33] suggest visiting art exhibitions as an activity to develop empathic thinking in medical students during their clinical placement: improvement in empathic thinking is shown, although further studies are needed. Ardenghi et al. [

34] note that, in general, extracurricular activities that promote self-awareness, self-reflection and communication can be pedagogical models that enhance empathic thinking in students.

Regarding clinical experience, Taveira-Gomez et al. [

35] report that medical students demonstrated enhanced competence and communication skills after completing a clinical internship. Yu et al. [

36] demonstrate that students who have participated in a clinical internship exhibit greater levels of empathy than those who have not. However, the authors acknowledge that further longitudinal studies are required to substantiate these findings due to the study's cross-sectional nature. As regards medical students, Grau et al. [

37] say that as medical training progresses, empathy levels among students tend to improve.

However, a study conducted in Spain by González-Serna et al. [

38] report that nursing students exhibit a diminished level of empathy when engaged in clinical practice. This study reveals that women demonstrate superior empathy outcomes compared to men and that the older the students, the lower the degree of empathy. These authors concur with Yu et al. [

36] that longitudinal studies are essential.

In their 2021 study, Imperato and Strano-Paul [

39] demonstrate that activities can be scheduled or trained during clinical placements to enhance or cultivate empathy. By convening meetings and reflection rounds where medical students shared their feelings, experiences, and reflections on their clinical placements, these students exhibited enhanced empathic thinking compared to their pre-placement levels.

Accordingly, as mentioned by Percy and Richardson [

40], the fostering of caring with empathy and compassion in nursing represents a pivotal theme that should be integrated into the training of future professionals. Güven et al. [

41] concur that assertiveness and empathy are essential for developing effective nursing professionals, as evidenced by the observation that a heightened proficiency in these two social skills is associated with a greater capacity for altruistic thinking. Enhancing empathic communication will facilitate the development of emotional intelligence in future nurses, consequently resulting in enhanced quality of care [

42,

43]. Communication competencies should be incorporated into the formal undergraduate physiotherapy curriculum, as they are competencies that facilitate the improvement of the care provided by future physiotherapy graduates [

44]. Rodríguez-Nogueira et al. [

45] demonstrate that service learning (SL) is an effective tool for fostering socioemotional growth and significantly reducing levels of personal distress on the Interpersonal Reactive Index Scale (IRI) among physiotherapy students.

As for the ideas of Cortina [

2] and Nishanthi and Vimal [

46], it can be argued that a professional should be characterised by altruism and follow a moral code. Consequently, these authors advocate that bioethics should be studied in the curricula, as bioethics and professionalism are intrinsically linked. Aguilar-Rodríguez et al. [

47] reinforce the idea that ethical training is of great importance for future physiotherapists, as it will enable them to identify situations in clinical practice where bioethical principles may be violated in patient care during their clinical training.

Assertiveness is also a crucial social skill for both nursing and physiotherapy. Like empathy, it enables professionals to provide superior quality care by equipping them with the ability to overcome interpersonal challenges and conflicts [

48]. Luna et al. [

49] demonstrate that nursing students with low assertiveness levels may exhibit heightened anxiety and depression. An increase in self-esteem accompanies an increase in assertiveness [

50].

The training of assertiveness among professionals will result in a working environment with improved communication, job satisfaction and quality of care for patients. The effectiveness of assertiveness training has been demonstrated [

51].

Ibrahim [

52] found that fourth-year nursing students exhibited higher levels of assertiveness than second-year students. This author posits that the factors influencing assertiveness development are family income and the psychological empowerment of students. The above author further asserts that specific training in assertiveness is necessary to enhance students' development. In a study conducted by Hernández-Xumet et al. [

53], assertiveness scores were acceptable in students in their final year of physiotherapy at a Spanish university. Furthermore, an inverse relationship between assertiveness and personal distress in terms of empathy was observed. This inverse relationship was maintained before and after the students' clinical training.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Objectives

The objective of this study is to assess the state of vocational care and the empathic and assertive levels of nursing and physiotherapy students at the University of La Laguna, study the differences and similarities between the two students' scores, and investigate the relationship between vocation for care and other soft skills such as empathy and assertiveness.

2.2. Research Design and Participants

An observational, descriptive, and cross-sectional study design was proposed following the STROBE guidelines.

2.3. Research Design

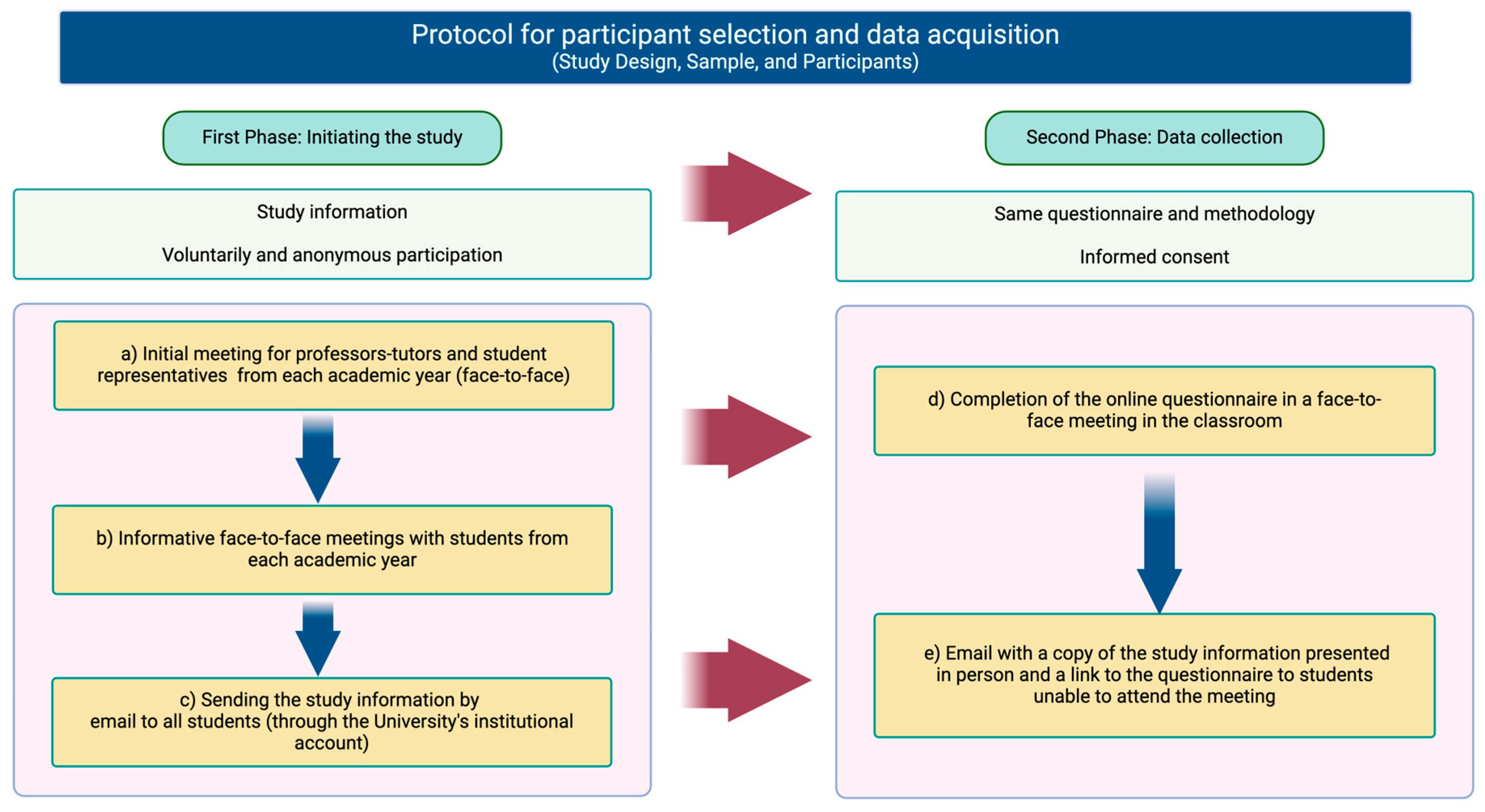

The research team contacted professors and student representatives from the degree course to ensure maximum participation from physiotherapy students. Students from each academic year were convened for a face-to-face meeting where the purpose of the research was explained, as well as the steps to follow to participate in the study; the aim in this first phase of the study was to provide information about the study.

In addition, all the students were invited via email to complete the questionnaire in a face-to-face meeting prior to the information day of the study. Subsequently, all students unable to attend the meetings (information or questionnaire) were sent an email with a copy of the study information presented in person and a link to the questionnaire that they could fill in voluntarily and anonymously, and informed consent was also obtained from the participants. The students were free to ask any questions before completing the questionnaire. The questionnaire was available for four weeks in November and December 2022. The questionnaire format was the same for all study participants; they always had to use the institutional account to access the questionnaire. For the data collection and information protocol, see

Figure 1.

2.4. Participants and Place of Study

The sample consisted of undergraduate nursing and physiotherapy students of the University of La Laguna. A total of 226 students, aged over 18, were recruited from September to December 2022. There were 93 nursing students and 133 physiotherapy students. All enrolled participants were informed of the study's purpose and procedures and provided their written informed consent. The inclusion criteria were: (a) university nursing and physiotherapy students, and (b) students who consented to participate in the study with full knowledge of its purpose and content. Students had to meet the criteria of 1 and 2 above to be included in the study.

The exclusion criteria were: (a) external university students on a national or international exchange programme that is, Erasmus, Sicue or similar; the Erasmus Programme is a student exchange programme between European universities; the Sicue Programme is an exchange programme similar to Erasmus but between universities in Spain. In these programmes, students spend 6–12 months at the university.

2.5. Outcome Measures

2.5.1. Instrument for Measuring Empathy: Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI)

The IRI provides separate assessments of cognitive and emotional processes. This index was initially developed by Davis [

54,

55]. It allows empathy to be viewed as a set of four factors rather than as a unidimensional concept. It is an easy-to-use scale consisting of 28 items divided into four subscales measuring four dimensions of the overall concept of empathy: Perspective Taking (PT), Fantasy (FS), Empathic Concern (EC) and Personal Distress (PD), each with seven items.

The PT and FS subscales assess cognitive processes. The PT score indicates the person's spontaneous attempts to take another person's perspective in real-life situations.

The FS subscale measures the tendency to identify with film and literary characters, i.e. the person's imaginative ability to place themselves in fictional situations.

The EC and PD subscales measure people's emotional reactions to others' negative experiences. The EC measures feelings of sympathy, concern, and care in the face of others' discomfort. The second (PD) measures feelings of anxiety and discomfort when perceiving the negative experiences of others.

The 28 items consist of a Likert-type response scale with five options according to the degree to which the statement describes the respondent (0 = does not describe me well; 1 = describes me a little; 2 = describes me well; 3 = describes me fairly well; and 4 = describes me very well) [

54,

55,

56,

57].

The IRI-Spanish version is one of the most widely used self-reporting measures to assess students' empathy[

56,

57].

2.5.2. Instrument for Measuring Assertiveness. Rathus Scale

The Rathus Assertiveness Scale (RAS) was designed to measure a person’s level of assertiveness. It is also an instrument for measuring behavioural change in assertion training. The RAS was developed in 1973 by Spencer Rathus [

58]. The RAS consists of 30 items (including 16 inverted items) with a 7 point Likert scale scored from −3 (very uncharacteristic of me) to 3 (very characteristic of me).

Leon-Madrigal and Vargas Halabí [

59] validated this RAS scale in Spanish and subsequently revised it [

60].

2.5.3. Instrument to Measure the Vocation for Health Care

The instrument "Vocation of Service for Human Care" was validated and created by Antonio-González [

61] to have a valid and specific instrument to determine the vocational level of nursing students. This questionnaire "will identify students who have a low service vocation for human care and, therefore, to carry out interventions to increase the service vocation for human care and, therefore, to reduce dropout" [

62]. The instrument considers patterns of knowledge, confidence in the vocation for care, and values and satisfaction with the chosen career. It consists of 23 items constructed on a Likert scale. Each item is answered with 1= never, 2= rarely, 3= sometimes, 4= almost always and 5= always [

61,

62].

The definition of the primary variable of this questionnaire, the vocation of service for human care, is the inclination or sense of inspiration that the student has to offer or dedicate care to the individual, family or community. This instrument consists of three dimensions: one called "inclination towards health care", a second called "self-efficacy in health care", and a third called "axiological component". The first dimension can be defined as the ease with which the student can provide care to healthy and sick people in community and clinical settings (items 3, 5, 7, 10, 12, 16 and 19). The second is defined as the student's confidence in providing care to healthy and sick people (items 1, 2, 4, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17 and 20). Moreover, finally, the axiological component is the set of ethical and moral values that the student has in their personal, professional and social life (items 6, 8, 14, 21, 22 and 23) [

61].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data management and analysis were performed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM, 2019) and Jamovi version 2.3.17 (Project, 2023). Descriptive analyses were performed, and mixed ANOVAs were conducted with the intragroup factor (pre/post) and the intergroup factor gender (male/female) to test whether gender or clinical practice affected empathy or assertiveness. The relationship between empathy and assertiveness scales was analysed using Pearson correlation analysis. A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

The University Research Ethics Committee (CEIBA-ULL) approved the study with code CEIBA2022-3133.

All students were recruited voluntarily and were free to withdraw from the study at any time. No participants were coerced or pressured to complete the survey, and they provided their consent for participation in the study.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis of Sample

A total of 226 students participated in the study, and 226 questionnaires were received (all questionnaires completed by students were valid; there were no partially completed questionnaires or missing data). The sample represented 35.31% of the total population of nursing and physiotherapy students at the university (226/640 students).

All participants were between 18 and 58 years old (M = 23.59; SD = 8.51).

The gender distribution of the sample was 71 men (31.40%) and 155 women (68.60%). The academic year distribution of students was 63 first year, 63 second year, 53 third year and 47 fourth year. The distribution of nursing and physiotherapy students was 133 physiotherapy students and 93 nursing students.

Regarding the employment status of the students, 22.60% (51/226) were working, and 19.00% (43/226) of the students had work experience in health sciences.

3.1.1. Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI—Spanish Version)

University nursing and physiotherapy students obtained an overall empathy score on the IRI subscales of perspective-taking (PT) (M = 27.71; SD = 4.12; Crombach's α = 0.70), empathic concern (EC) (M = 27.92; SD = 3.81; Crombach's α = 0.82), fantasy (FS) (M = 23.60; SD = 5.84; Crombach's α = 0.79), and personal distress (PD) (M = 15.76; SD = 4.40; Crombach's α = 0.69). The results from each subscale in nursing and physiotherapy students, by gender and academic year, are shown in

Table 1.

3.1.2. The Rathus Assertiveness Scale (RAS-Spanish Version)

Nursing and physiotherapy students obtained a global RAS score of −2.16 (SD = 25.09; Crombach's α = 0.86). 10.20% of students (23/226) got a “very assertive” score, 75.20% (170/226) obtained “acceptable assertiveness”, and 14.60% (33/226) were “slightly assertive.” RAS scores on the different assertiveness results grouped by academic year or gender are shown in

Table 2.

3.1.3. The “Vocation of Service for Human Care” Questionnaire

Nursing and physiotherapy students received a global vocation score of 79.37 points for "good vocation"; between 50 and 75 is a regular vocation, and above 75 is considered good (SD = 11.84; Crombach's α = 0.88). 37.60% (85/226) obtained “regular vocation”, and 62.40% (141/226) were “good vocation” (No student scored “low vocation” or "very low vocation"). Vocation scores on the different subscales by academic year or gender are shown in

Table 3.

3.2. Inferential Analysis

3.2.1. Empathy

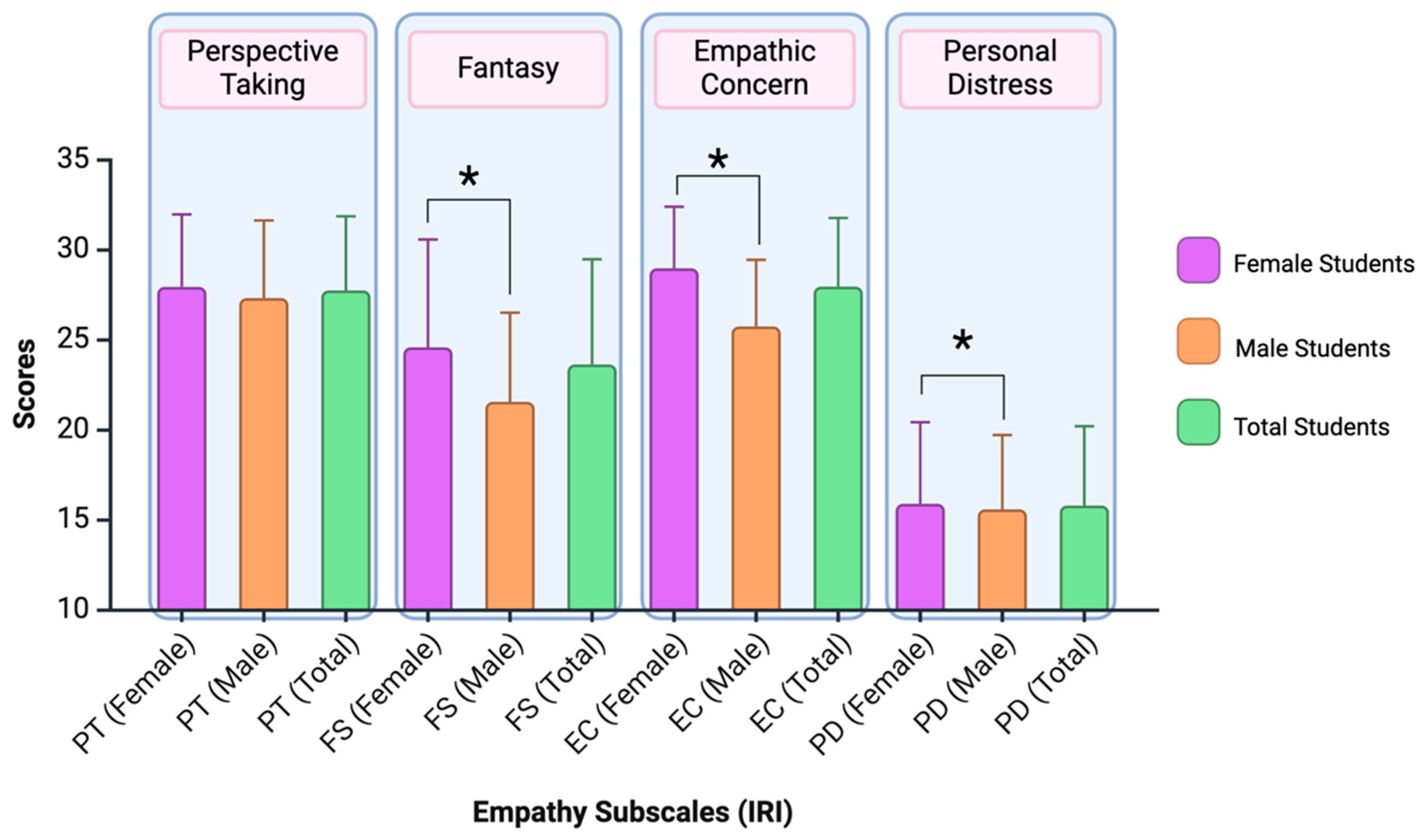

Significant differences were found in the multivariate analysis in relation to gender (F4, 219=7.192; p<0.001; η2=0.116) and the specific career of the students (F4, 219=3.087; p=0.017; η2=0.053). No statistical significance was found for the interaction between gender and the student's career (F4, 219=0.864; p=0.486).

Empathy subscales were analyzed while considering interactions, and significant differences were found in three empathy subscales concerning the gender variable (fantasy, empathic concern and personal distress; see

Figure 2.). Females scored higher than males in the fantasy subscale (F

3, 222=11.931; p=0.001;

η2=0.051). Females scored higher on the empathic concern subscale (F

3, 222=25.070; p<0.001;

η2=0.101). Females also scored higher on the personal distress subscale(F

3, 222=3.943; p=0.048;

η2=0.017).

Significant differences were found in the empathy subscale PD concerning the specific career of the students (see

Figure 3). Physiotherapy students scored higher than nursing students in the personal distress subscale (F

3, 222=9.402; p=0.002;

η2=0.041).

Significant differences were also found in the FS and PD empathy subscales concerning questions about working while studying (F4, 219=2.527; p=0.042; η2=0.044). Students concurrently studying with a job had lower scores on the FS (F3, 222=3.913; p=0.049; η2=0.017) and PD (F3, 222=6.768; p=0.010; η2=0.030) empathy subscales.

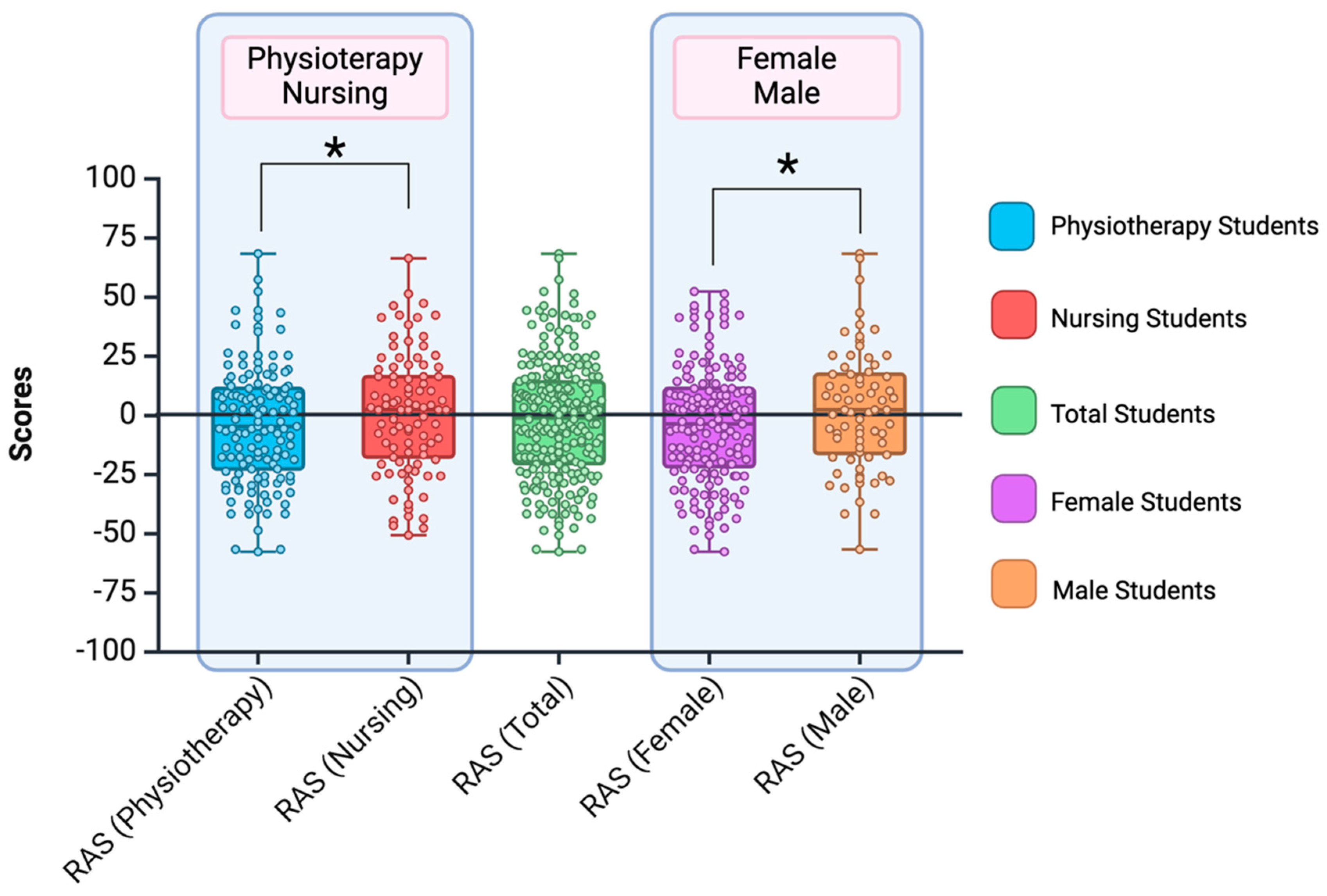

3.2.2. Assertiveness

Significant differences were found in the multivariate analysis, the gender (F

3, 222=6.356; p=0.012;

η2=0.028) and the specific career of the students (F

3, 222=5.481; p=0.020;

η2=0.024). Males scored higher than females in assertiveness. Nursing students score higher in assertiveness than physiotherapy students (See

Figure 4). No statistical significance was found for the interaction between gender and the student's career (F

3, 222=1.487; p=0.224).

Significant differences were also found in assertiveness regarding questions about working while studying (F4, 219=7.721; p=0.006; η2=0.034). Students concurrently studying with a job had lower scores on assertiveness.

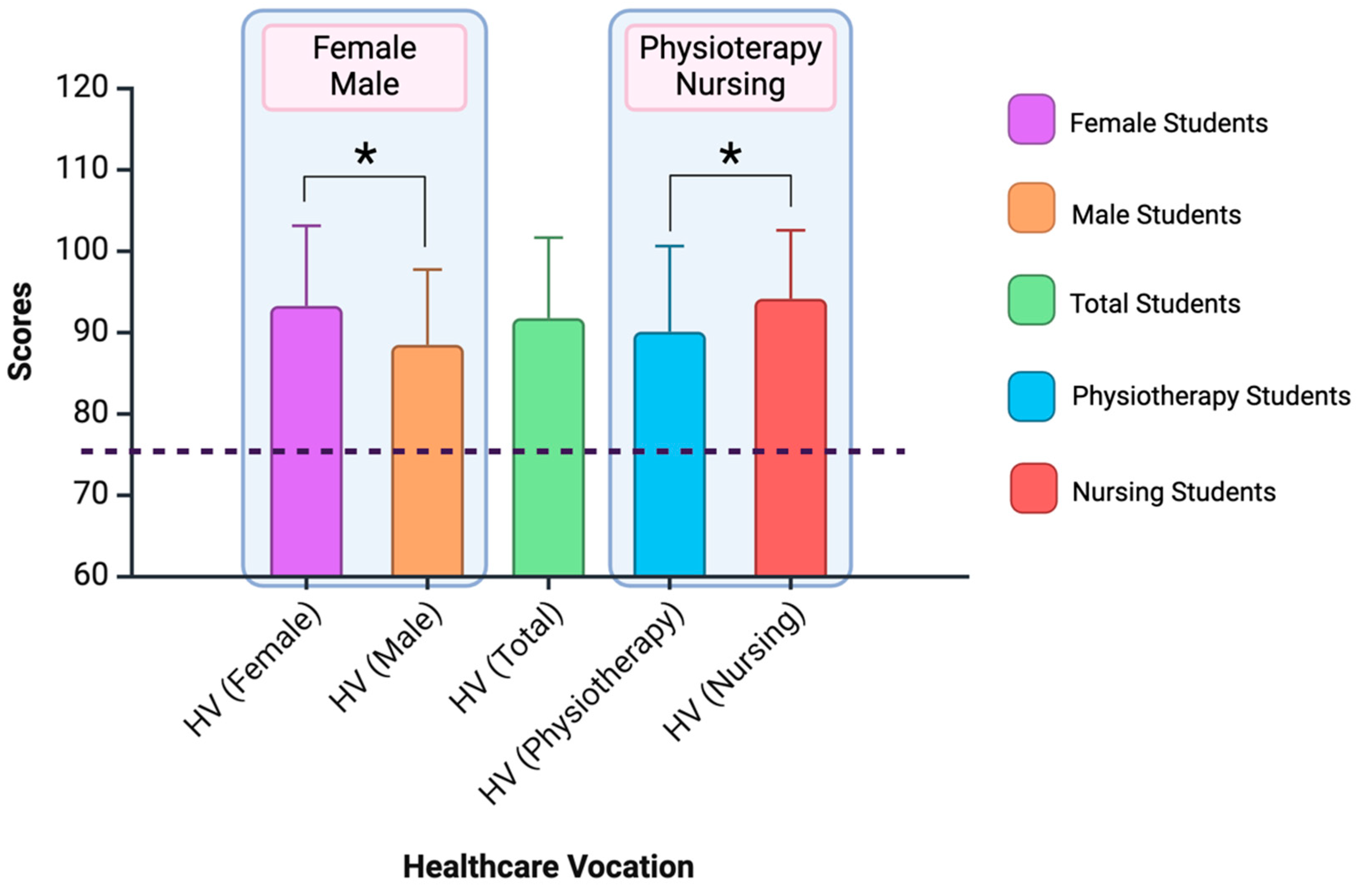

3.2.3. Vocation of Service for Human Care

Significant differences were found in the multivariate analysis, the gender (F

3, 220=7.203; p<0.001;

η2=0.089) and the specific career of the students (F

3, 220=3.477; p=0.017;

η2=0.045). No statistical significance was found for the interaction between gender and the student's career (F

3, 220=0.980; p=0.403). See

Figure 5.

The overall vocation score, as well as the three dimensions of the scale, were analysed while considering interactions, and significant differences were found concerning the gender variable (overall result and dimension 1). Females scored higher than males in vocation (F3, 222=13.114; p=0.001; η2=0.151). Females scored higher on dimension 1 (F3, 222=10.231; p=0.002; η2=0.044). Differences in vocation were also found between nursing students and physiotherapy students (overall result and dimensions 1 and 2). Nursing students scored higher than physiotherapy students in vocation (F3, 222=9.134; p=0.024; η2=0.076). Nursing students scored higher than physiotherapy students in dimension 1 (F3, 222=8.558; p=0.004; η2=0.037) and dimension 2 (F3, 222=6.043; p=0.015; η2=0.027).

No significant differences were found in vocation concerning questions about working while studying (F4, 222=0.146; p=0.703).

3.2.4. Correlation Analysis

The perspective-taking and fantasy empathy subscales showed a significant positive correlation with another empathy subscale empathic concern. The perspective taking subscale had a positive correlation with empathic concern (r[226] = 0.306; p < 0.001). The fantasy subscale also had a positive correlation with empathic concern (r[226] = 0.442; p < 0.001).

The perspective-taking subscale showed a significant positive correlation with vocation (overall - r[226] = 0.252; p < 0.001), and vocation-dimension 1 (r[226] = 0.289; p < 0.001)

The personal distress empathy subscale showed a significant negative correlation with RAS-assertiveness (r[226] = −0.317; p < 0.001). The PD subscale also showed a significant negative correlation with vocation-dimension 2 (r[226] = −0.260; p < 0.001).

The empathic concern empathy subscale showed a significant correlation with vocation (overall - r[226] = 0.351; p < 0.001), with vocation-dimension 1 (r[226] = 0.461; p < 0.001), and with vocation-dimension 3 (r[226] = 0.346; p < 0.001).

The results of the correlational analysis are shown in

Table 4.

4. Discussion

The training of health professionals requires individuals with a vocation for service and a positive attitude who respond efficiently, empathetically, assertively and humanistically to the demands of caring for life and restoring a person's health [

63,

64,

65]. Consequently, selecting a career in nursing or physiotherapy necessitates the possession of personal attributes that extend beyond the purely scientific and technical. These are highly humanistic professions in which professionals are dedicated to their social function. They are essential in health services, and the objectives focus on the prevention, promotion and rehabilitation of health [

64,

65].

The present study highlights that nursing and physiotherapy students exhibit acceptable levels of empathy, assertiveness and vocational level for care. It is evident that, although the scale for measuring the "Vocation of Service for Human Care" was designed for nursing, physiotherapy students demonstrated comparable results of an acceptable level on this scale to nursing students. According to the findings of Antonio-González et al. [

61,

62], results exceeding the score of 76 points are indicative of a positive vocation. Among the results of the physiotherapy students, 92% achieved scores above this threshold, with none obtaining scores considered low or very low (below 50 points). Consequently, educators need to emphasise the importance of critical and ethical thinking in nursing and physiotherapy education.

Furthermore, physiotherapy students pursue these studies to provide assistance and care to others [

17,

18]. We concur with the author Anaya-Requejo [

11] in that our findings revealed no correlation between sociodemographic variables and the decision to pursue a career in nursing. The student population across both degree programmes is sociodemographically diverse. However, as evidenced by the findings of Arenas-Ramírez et al. [

13], it is important to monitor the levels of vocation displayed by students as they progress through their training, as these can fluctuate.

Regarding gender, females had higher scores in FS and EC than males, and males had higher scores in PD. This phenomenon is inferentially related to two of the three dimensions of the vocation of care: the inclination towards health care (dimension 1) and the axiological component (dimension 3).

A comparison of the scores of nursing and physiotherapy students revealed that nursing students tended to perform better than physiotherapy students on the EC empathy subscale and the vocation scale. However, physiotherapy students scored higher than nursing students on the PD subscale.

It is important to note that students who have a job in health science areas while studying for their degree in nursing or physiotherapy tended to obtain lower scores in the subscales of empathy (EC and FS) and vocation. However, they tended to obtain better scores in assertiveness (RAS) and higher scores in personal distress (PD). This phenomenon has also been demonstrated in the study conducted by Hernández-Xumet et al. [

66], in which students with previous experience in other health sciences exhibited higher scores in RAS and PD. In the present study, those with a job or professional experience in other areas or professions of health sciences exhibited the same phenomenon, with a significant proximity to dimension 2 of vocation for care (service self-efficacy).

The results of the present study demonstrate a correlation between the IRI subscales (PT, EC) and the three dimensions of vocation for care. Regarding the IRI FS subscale, a correlation was observed between EC and PD. The EC subscale correlated with dimensions 1 and 3 of vocation for care, while EC demonstrated an inverse correlation with RAS. A similar inverse correlation was observed with the PD subscale, which exhibited an inverse correlation between PD and the three dimensions of the vocation for care.

Individuals with high perspective-taking (PT) levels are more likely to volunteer in a hospital or clinic. This is due to their enhanced capacity to comprehend the needs of patients and how they can assist them. Furthermore, such an individual is more likely to exhibit a robust ethical and moral compass, as they are better able to comprehend the needs of others and the impact of their actions on them.

Individuals with high levels of empathic concern (EC) are more likely to pursue careers in nursing or medicine. This is due to their strong compassion for the suffering of others and their desire to help them feel better. They are also more likely to act compassionately and altruistically, as they feel a strong connection with others and want to help them feel better.

4.1. Inferential Study

As demonstrated above, female students exhibited higher levels of empathy. This is in line with the findings of Moreno Segura et al. [

67], which posit that physiotherapists demonstrate acceptable ethical and moral sensitivity. The authors note that women scored higher on empathy tests than men. Understanding the characteristics of physiotherapists is crucial for developing ethical training programmes that enhance clinical care. As Marqués-Sule et al. [

68] point out, future physiotherapists attach great importance to ethics training and its impact on their professional training. Ethical awareness is interrelated with safety in clinical practice and ethics is fundamental to any healthcare professional [

2].

The same is valid for nursing, as described by Deng et al. [

69], in that female nursing students have higher levels of emotional intelligence than male students. These researchers suggest that nursing educators should address gender differences in empathy, emotional intelligence, and problem-solving skills. Women with higher scores may exhibit greater confidence in their ability to provide care, enhanced capacity to empathise with and understand the needs of others, and the ability to deliver more personalised care. It would be beneficial to implement strategies that cultivate soft skills and foster an inclusive learning environment in nursing and physiotherapy faculties that values diversity and students' unique skills and talents, aiming to optimise those differences that enhance future work readiness. González Serna et al. [

38] observed that female nursing students showed superior empathy scores to their male counterparts. Similarly, Hernandez-Xumet et al. [

66] reported a comparable phenomenon among physiotherapy students.

The data indicate that females outperformed males in general and specific dimensions related to health vocation (possibly related to the choice of health professions). This could suggest a greater interest or inclination towards health careers among female students in this cohort.

Regarding empathy (FS), female physiotherapy students had significantly higher scores than their male counterparts in the capacity to identify with fictional characters and comprehend their emotional states. This could indicate a greater capacity for empathy and emotional connection with imaginary situations. The same phenomenon occurs with the empathic concern (EC) dimension; females demonstrated more significant empathic concern and compassion towards others than males. This suggests that females in this group of students have a stronger inclination towards understanding and responding emotionally to the needs and discomforts of others.

4.2. Correlational Study

In the correlational study, the four IRI subscales measure four dimensions of the global concept of empathy. The PT and FS subscales cover more cognitive aspects related to the spontaneous attempts of the subject to adopt the perspective of the other and to understand the point of view of the other person. They evaluate the tendency to identify with others and the imaginative capacity to put themselves in fictitious situations. The other two subscales, EC and PD, measure people's emotional reactions to negative experiences. The first (EC) measures the feelings “oriented towards the other person”; the second (PD) evaluates the feelings of anxiety and discomfort that the subject manifests when observing the negative experiences of others (these are self-oriented feelings). Therefore, these two subscales refer to different feelings. The present study found an inverse correlation between the empathy subscale PD and assertiveness-RAS, which suggests that the students' assertiveness improves with a lower score in PD. This phenomenon coincides with the results of Hernández-Xumet et al. [

66], where such inverse correlations have also been observed.

Delgado et al. [

70] observed a correlation between burnout and specific empathy subscales among healthcare professionals in a recent study. Their findings indicate that inferring mental states was positively associated with perspective-taking and empathic concern but not with personal distress. Furthermore, emotional exhaustion was found to be associated with higher levels of personal distress and higher levels of mental state inferences. The findings suggest that depersonalisation is associated with elevated levels of personal distress and diminished levels of empathic concern. The present study reveals a correlation between low assertiveness scores, personal distress (PD), and low vocation for care scores. This is consistent with another recently published study in which physiotherapy students who scored low in assertiveness scored higher in personal distress (PD) [

66]. As mentioned above, nursing students with lower levels of assertiveness are more likely to suffer from anxiety and depression [

49].

It is paramount to be attentive to our students' personal and emotional burnout. This is because, as Carvalho et al. [

71] argue, emotional intelligence is interrelated with the well-being of medical, nursing and physiotherapy students. If students in these professions have good well-being, they can provide better care to their future patients, thus preventing burnout syndrome. As posited by Lee et al. [

72], the development of empathic abilities in student nurses is contingent upon acquiring self-awareness. The satisfaction of student nurses in their clinical practice may be correlated with the development of self-awareness and empathic abilities. Hernández-Xumet et al. [

53] observed, in their longitudinal study with fourth-year physiotherapy students, that levels of empathy and assertiveness were acceptable before and after clinical practice, but there was a decline.

Individuals with elevated levels of assertiveness are more likely to communicate effectively with patients, their families, and other healthcare professionals. Furthermore, they are more likely to advocate for patients' rights. Consequently, it can be inferred that they are more likely to act ethically and professionally and to speak out against unethical practices or malpractice in the healthcare setting.

4.3. Future Lines of Research

In light of the findings, the scope of research should extend beyond descriptive observational studies to encompass interventions aimed at enhancing or elucidating the development of a caring vocation among students. This is in line with the observations by Arda Sürücü et al. [

73], who posit that nursing students' negative perceptions of cancer diminish as their empathic abilities improve. It is recommended that undergraduate training should not only include clinical training but also empathic training.

Longitudinal studies help observe and monitor whether empathic development, for example, declines during students' training. Yucel [

74] observed a decline in empathy among fourth-year students in a longitudinal study with physiotherapy students. This decline was associated with clinical practice and academic courses. The author found that first-year students exhibited higher levels of empathy. Longitudinal studies involving educational interventions are highly beneficial. Consequently, Yang et al. [

75] propose that longitudinal studies should be conducted to examine empathic development in nursing students. Educational interventions designed to foster empathy have been demonstrated to be effective at the experimental level and should be further integrated into undergraduate education.

As argued by Unal et al. [

76], simulation is an effective educational intervention tool that helps nursing students develop physical and patient skills as well as empathic skills. In particular, Ward et al. [

77] highlight the usefulness of virtual simulation as a valuable tool for the empathic development of physiotherapy students, as demonstrated in a longitudinal study.

Sung and Kweon [

78] report, in a quasi-experimental pilot study among nursing students, that those who participated in activities to improve empathic communication had superior self-esteem, empathic ability, interpersonal relationships, and communicative competence scores than those who did not participate in the educational intervention. In light of the aforementioned findings, there is a clear need for ongoing and repetitive educational initiatives that can assist nursing students in enhancing their empathy-based interpersonal relationships and communicative competence within the nursing curriculum.

The advent of digital technologies has the potential to influence empathy, particularly in the context of communication. Further study is required to gain a deeper understanding of the empathic development of student nurses, particularly in the digital age. The issue of digital empathy is emerging, and therefore, nursing students need to receive training in digital empathic and communicative skills [

72]. Simulation has been identified as an effective tool for the enhancement of empathic development in nursing students [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

79].

The results demonstrate a clear correlation between a vocation for care and soft skills development, underscoring the necessity for training in these competencies, particularly empathy. As mentioned above, the absence of sensitivity and empathy precludes the formation of a vocation [

2]. It is therefore imperative that health science teachers monitor and evaluate the development of soft skills, such as empathy and assertiveness, and vocation among their students in order to ensure the delivery of better patient care [

13,

14,

16,

51,

80,

81].

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study include the fact that two different student populations, physiotherapy and nursing, were studied in a similar academic and clinical training context. In addition, more scientific work needs to be done on the simultaneous study of soft skills such as empathy and assertiveness in the professional profiles of future nursing and physiotherapy professionals.

Limitations include the observational and descriptive nature of the study. In addition, as described above, the Vocational Level Rating Scale is designed for nursing. Although it can be applied to physiotherapy and other health professions and provides interesting results, there are still no more specific scales for professions other than for nursing.

Therefore, further studies, not only observational studies, and the development of scales for assessing the professional vocation of physiotherapy in Spanish are needed.

5. Conclusions

Nursing and physiotherapy students have highly acceptable scores in terms of empathy, assertiveness, and vocation for care. Females have higher scores than males in both degrees. Higher scores for caring are observed among nursing students, but physiotherapy students also have more than acceptable scores.

There is a relationship between vocation for care and empathy. A relationship between previous work experience and lower scores in empathy and caring and between lower scores in empathy and higher scores in assertiveness and caring was found too.

Future research should consider longitudinal studies with educational interventions such as simulation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, Juan-Elicio Hernández-Xumet and Cristo-Manuel Marrero-González; methodology, Juan-Elicio Hernández-Xumet, Alfonso-Miguel García-Hernández, Jerónimo-Pedro Fernández-González and Cristo-Manuel Marrero-González; software, Juan-Elicio Hernández-Xumet and Cristo-Manuel Marrero-González; validation, Juan-Elicio Hernández-Xumet and Cristo-Manuel Marrero-González; formal analysis, Juan-Elicio Hernández-Xumet; investigation, Juan-Elicio Hernández-Xumet, Alfonso-Miguel García-Hernández, Jerónimo-Pedro Fernández-González and Cristo-Manuel Marrero-González; resources, Juan-Elicio Hernández-Xumet; data curation, Juan-Elicio Hernández-Xumet; writing—original draft preparation, Juan-Elicio Hernández-Xumet, Alfonso-Miguel García-Hernández, Jerónimo-Pedro Fernández-González and Cristo-Manuel Marrero-González; writing—review and editing, Juan-Elicio Hernández-Xumet, Alfonso-Miguel García-Hernández, Jerónimo-Pedro Fernández-González and Cristo-Manuel Marrero-González; visualisation, Juan-Elicio Hernández-Xumet and Cristo-Manuel Marrero-González; supervision, Juan-Elicio Hernández-Xumet; project administration, Juan-Elicio Hernández-Xumet and Cristo-Manuel Marrero-González. All authors have read and approved the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Universidad de La Laguna Research Ethics Committee (CEIBA- ULL), with code CEIBA 2022-3133. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Informed consent was obtained from the students to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Public Involvement Statement

Please describe how the public (patients, consumers, carers) were involved in the research. Consider reporting against the GRIPP2 (Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public) checklist. If the public were not involved in any aspect of the research add: “No public involvement in any aspect of this research”.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks to Dr. Stephany Hess Medler, Professor at the Universidad de La Laguna (Departamento de Psicología Clínica, Psicobiología y Metodología) for her help with the statistical analysis. The authoring team would also like to thank the participants in the present study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gafo, J. Bioética Teológica: Edición a Cargo de Julio l. Martinez; 2008.

- Cortina, A. ¿Para qué sirve realmente la ética?; 2013.

- Nico Nortjé, J.-C. D. J., Willem A. Hoffmann. African Perspectives on Ethics for Healthcare Professionals; Springer Cham, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Martins, V. S. M.; Santos, C. M. N. C.; Bataglia, P. U. R.; Duarte, I. M. R. F. The Teaching of Ethics and the Moral Competence of Medical and Nursing Students. Health Care Anal 2021, 29, 113-126. [CrossRef]

- Marques-Sulé, E.; Arnal-Gómez, A.; Cortés-Amador, S.; de la Torre, M. I.; Hernández, D.; Aguilar-Rodríguez, M. Attitudes towards learning professional ethics in undergraduate physiotherapy students: A STROBE compliant cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today 2021, 98, 104771. [CrossRef]

- Arman, M. Empathy, sympathy, and altruism-An evident triad based on compassion. A theoretical model for caring. Scand J Caring Sci 2023, (00), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Vilca Golac, K. L. Significado de vocación profesional en los estudiantes de enfermería de la Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza-Amazonas, Chachapoyas – 2018. Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza de Amazonas, Perú, 2019. https://repositorio.untrm.edu.pe/handle/20.500.14077/1998.

- Öztürk, A.; Kaçan, H. Compassionate communication levels of nursing students: Predictive role of empathic skills and nursing communication course. Perspect Psychiatr Care 2022, 58, 248-255. [CrossRef]

- Alvarado García, A. La ética del cuidado. Aquichan 2004, 4, 30-39.

- Mármol-López, M. I.; Marques-Sule, E.; Naamanka, K.; Arnal-Gómez, A.; Cortés-Amador, S.; Durante, Á.; Tejada-Garrido, C. I.; Navas-Echazarreta, N.; Juárez-Vela, R.; Gea, V. Physiotherapists' ethical behavior in professional practice: a qualitative study. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1158434. [CrossRef]

- Anaya Requejo, M. M. Factores sociopersonales y vocación por la profesión de enfermería en los estudiantes de la UNC filial Jaén, 2021. Universidad Nacional de Cajamarca, Perú, 2021. https://repositorio.unc.edu.pe/handle/20.500.14074/5110.

- Limanta Barrios, J. A. Factores socio-personales que influyen en la vocación profesional de los estudiantes de la Escuela Profesional de Enfermería de la UNJBG, Tacna - 2019. Universidad Nacional Jorge Basadre Grohmann, Perú, 2020. http://redi.unjbg.edu.pe/handle/UNJBG/3987.

- Arenas-Ramírez, A.; Jiménez-Cervantes, K.; Almonte-Maceda, M.; Ramirez-Giron, N. Vocación para el cuidado humano en estudiantes de enfermería en una universidad de México. Index de Enfermería 2022, 31, 227-231.

- van den Boogaard, T. C.; Roodbol, P. F.; Poslawsky, I. E.; Ten Hoeve, Y. The orientation and attitudes of intermediate vocational trained nursing students (MBO-V) towards their future profession: A pre-post survey. Nurse Educ Pract 2019, 37, 124-131. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cao, M.; Ma, D.; Zhang, G.; Shi, Y.; Chen, B. Exploring effect of psychological first aid education on vocational nursing students: A quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ Today 2022, 119, 105576. [CrossRef]

- Akhter, Z.; Malik, G.; Plummer, V. Nurse educator knowledge, attitude and skills towards using high-fidelity simulation: A study in the vocational education sector. Nurse Educ Pract 2021, 53, 103048. [CrossRef]

- de Góes, F. o. S.; Côrrea, A. K.; de Camargo, R. A.; Hara, C. Y. Learning needs of Nursing students in technical vocational education. Rev Bras Enferm 2015, 68, 15-20, 20-15. [CrossRef]

- Fuente-Vidal, A.; March-Amengual, J. M.; Bezerra de Souza, D. L.; Busquets-Alibés, E.; Sole, S.; Cañete, S.; Jerez-Roig, J. Factors influencing student choice of a degree in physiotherapy: a population-based study in Catalonia (Spain). PeerJ 2021, 9, e10991. [CrossRef]

- Jia-Ru, J.; Yan-Xue, Z.; Wen-Nv, H. Empathy ability of nursing students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022, 101, e30017. [CrossRef]

- Moudatsou, M.; Stavropoulou, A.; Philalithis, A.; Koukouli, S. The Role of Empathy in Health and Social Care Professionals. Healthcare (Basel) 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A. R.; Nihei, O. K. Burnout among nursing students: predictors and association with empathy and self-efficacy. Rev Bras Enferm 2020, 73, e20180280. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.; Thomas-Gregory, A.; Hofmeyer, A. Teaching empathy and resilience to undergraduate nursing students: A call to action in the context of Covid-19. Nurse Educ Today 2020, 94, 104524. [CrossRef]

- Levett-Jones, T.; Cant, R.; Lapkin, S. A systematic review of the effectiveness of empathy education for undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ Today 2019, 75, 80-94. [CrossRef]

- Bas-Sarmiento, P.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, M.; Díaz-Rodríguez, M.; Team, i. Teaching empathy to nursing students: A randomised controlled trial. Nurse Educ Today 2019, 80, 40-51. [CrossRef]

- Buchman, S.; Henderson, D. Interprofessional empathy and communication competency development in healthcare professions’ curriculum through immersive virtual reality experiences. Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice 2019, 15, 127-130. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, X.; Gu, L.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, R.; Cai, Q.; Lu, Y.; Wang, H.; Meng, Q.; Wei, H. Effects of Simulation-Based Deliberate Practice on Nursing Students' Communication, Empathy, and Self-Efficacy. J Nurs Educ 2019, 58, 681-689. [CrossRef]

- Engbers, R. A. Students' perceptions of interventions designed to foster empathy: An integrative review. Nurse Educ Today 2020, 86, 104325. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, K. E.; Roberto, A.; Salmon, S.; Smalley, V. Nursing Student Interprofessional Simulation Increases Empathy and Improves Attitudes on Poverty. J Community Health Nurs 2020, 37, 19-25. [CrossRef]

- Cannity, K. M.; Banerjee, S. C.; Hichenberg, S.; Leon-Nastasi, A. D.; Howell, F.; Coyle, N.; Zaider, T.; Parker, P. A. Acceptability and efficacy of a communication skills training for nursing students: Building empathy and discussing complex situations. Nurse Educ Pract 2021, 50, 102928. [CrossRef]

- Huisman-de Waal, G.; Feo, R.; Vermeulen, H.; Heinen, M. Students' perspectives on basic nursing care education. J Clin Nurs 2018, 27 (11-12), 2450-2459. [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz Doğdu, A.; Aktaş, K.; Dursun Ergezen, F.; Bozkurt, S. A.; Ergezen, Y.; Kol, E. The empathy level and caring behaviors perceptions of nursing students: A cross-sectional and correlational study. Perspect Psychiatr Care 2022, 58, 2653-2663. [CrossRef]

- Blanton, S.; Greenfield, B. H.; Jensen, G. M.; Swisher, L. L.; Kirsch, N. R.; Davis, C.; Purtilo, R. Can Reading Tolstoy Make Us Better Physical Therapists? The Role of the Health Humanities in Physical Therapy. Phys Ther 2020, 100, 885-889. [CrossRef]

- Strohbehn, G. W.; Hoffman, S. J. K.; Tokaz, M.; Houchens, N.; Slavin, R.; Winter, S.; Quinn, M.; Ratz, D.; Saint, S.; Chopra, V.; Howell, J. D. Visual arts in the clinical clerkship: a pilot cluster-randomized, controlled trial. BMC Med Educ 2020, 20, 481. [CrossRef]

- Ardenghi, S.; Russo, S.; Bani, M.; Rampoldi, G.; Strepparava, M. G. Supporting students with empathy: the association between empathy and coping strategies in pre-clinical medical students. Current Psychology 2023, 23, 131. [CrossRef]

- Taveira-Gomes, I.; Mota-Cardoso, R.; Figueiredo-Braga, M. Communication skills in medical students - An exploratory study before and after clerkships. Porto Biomed J 2016, 1, 173-180. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, M.; Lim, K.; Chang, K.; Lee, M. Relationships Between Perspective-Taking, Empathic Concern, and Self-rating of Empathy as a Physician Among Medical Students. Acad Psychiatry 2020, 44, 316-319. [CrossRef]

- Grau, A.; Toran, P.; Zamora, A.; Quesada, M.; Carrion, C.; Vilert, E.; Castro, A.; Cerezo, C.; Vargas, S.; Gali, B.; Cordon, F. Evaluación de la empatía en estudiantes de Medicina. Educación Médica 2017, 18, 114-120. [CrossRef]

- González-Serna, J. M. G.; Serrano, R. R.; Martín, M. S. M.; Fernández, J. M. A. Descenso de empatía en estudiantes de enfermería y análisis de posibles factores implicados. Psicología Educativa 2014, 20, 53-60. [CrossRef]

- Imperato, A.; Strano-Paul, L. Impact of Reflection on Empathy and Emotional Intelligence in Third-Year Medical Students. Acad Psychiatry 2021, 45, 350-353. [CrossRef]

- Percy, M.; Richardson, C. Introducing nursing practice to student nurses: How can we promote care compassion and empathy. Nurse Educ Pract 2018, 29, 200-205. [CrossRef]

- Ş. Dılek Güven, A. Ü. The relationship between levels of altruism, empathy and assertiveness in nursing students. In Innowacje w Pielęgniarstwie i Naukach o Zdrowiu, Innowacje w Pielęgniarstwie i Naukach o Zdrowiu: 2019; Vol. 4, pp 71-90.

- Martín Fernández, M. T. Empatía en los profesionales de la salud: formas de enseñarla. Trabajo fin de grado, Universitat de les Illes Balears, 2022. https://dspace.uib.es/xmlui/handle/11201/157559?show=full.

- Giménez-Espert, M. D. C.; Maldonado, S.; Prado-Gascó, V. Influence of Emotional Skills on Attitudes towards Communication: Nursing Students vs. Nurses. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20. [CrossRef]

- Santos, L. A.; Meneses, R. F.; Couto, G. Competências de Comunicação na Formação Pré-Graduada de Estudantes de Fisioterapia: Análise Comparativa Documental. E- Revista de Estudos Interculturais 2022, (10). (acccessed 2023/07/13). [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Nogueira, Ó.; Moreno-Poyato, A. R.; Álvarez-Álvarez, M. J.; Pinto-Carral, A. Significant socio-emotional learning and improvement of empathy in physiotherapy students through service learning methodology: A mixed methods research. Nurse Educ Today 2020, 90, 104437. [CrossRef]

- Nishanthi, A.; Vimal, M. Professionalism and bioethics. C hrismed Journal of Health and Research: 2021; Vol. 8, p 6.

- Aguilar-Rodríguez, M.; Kulju, K.; Hernández-Guillén, D.; Mármol-López, M. I.; Querol-Giner, F.; Marques-Sule, E. Physiotherapy Students' Experiences about Ethical Situations Encountered in Clinical Practices. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [CrossRef]

- Cañón-Montañez, W.; Rodríguez-Acelas, A. L. Asertividad: una habilidad social necesaria en los profesionales de enfermeríay fisioterapia. Texto & Contexto - Enfermagem 2011, 20.

- Luna, D.; González-Velázquez, M. S.; Acevedo-Peña, M.; Figuerola-Escoto, R. P.; Lezana-Fernández, M. Á.; Meneses-González, F. Relación entre empatía, asertividad, ansiedad y depresión en estudiantes mexicanos de enfermería. Index de Enfermería 2022, 31, 129-133.

- Valdivia, J. B.; Zúñiga, B. R.; Orta, M. A. P.; González, S. F. RELACIÓN ENTRE AUTOESTIMA Y ASERTIVIDAD EN ESTUDIANTES UNIVERSITARIOS. Tlatemoani 2020, (34).

- Yoshinaga, N.; Nakamura, Y.; Tanoue, H.; MacLiam, F.; Aoishi, K.; Shiraishi, Y. Is modified brief assertiveness training for nurses effective? A single-group study with long-term follow-up. J Nurs Manag 2018, 26, 59-65. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S. A. Factors affecting assertiveness among student nurses. Nurse Educ Today 2011, 31, 356-360. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Xumet, J.-E.; García-Hernández, A. M.; Fernández-González, J. P.; Marrero-González, C.-M. Exploring levels of empathy and assertiveness in final year physiotherapy students during clinical placements. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 13349. [CrossRef]

- Davis, M. H. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Catalog od Selected Documents in Psychology: 1980; Vol. 10, p 85.

- Davis, M. H. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1983, 44, 113-126. [CrossRef]

- Escrivá, V. M.; Navarro, M. D. F.; García, P. S. La medida de la empatía: Análisis del Interpersonal Reactivity Index. [Measuring empathy: The Interpersonal Reactivity Index.]. Psicothema 2004, 16, 255-260.

- Arenas Estevez, L. F.; Rangel Quiñonez, H. S.; Cortés Aguilar, A.; Palacio Garcia, L. A. Validación en español del Índice de Reactividad Interpersonal –IRI- en estudiantes universitarios colombianos. Psychology, Society & Education 2021, 13, 121-135. (acccessed 2023/05/03). [CrossRef]

- Rathus, S. A. A 30-item schedule for assessing assertive behavior. Behavior Therapy 1973, 4, 398-406. [CrossRef]

- León Madrigal, M.; Vargas Halabí, T. Validación y estandarización de la Escala de Asertividad de Rathus (R.A.S.) en una muestra de adultos costarricenses. Revista Costarricense de Psicología 2009, 28 (41-42), 187-205. (acccessed 2023/5/3).Redalyc.

- León Madrigal, M. Revisión de la escala de asertividad de Rathus adaptada por León y Vargas (2009). Revista Reflexiones 2014, 93, 15. (acccessed 2023/05/03). [CrossRef]

- Antonio González, G. Validación del instrumento “vocación de servicio para el cuidado humano” en estudiantes de licenciatura en enfermería. Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Mexico, 2016. https://repositorioinstitucional.buap.mx/items/27711378-8d1b-416f-b34e-05efd49ecea4/full.

- Antonio González, G.; Montes Andrade, J. S.; Ramírez-Girón, N.; Landeros-Olvera, E. Validación del instrumento de vocación de servicio al cuidado humano en estudiantes de enfermería. Index de Enfermería 2021, 30, 254-258.

- Cárdenas, B., L. El pensamiento reflexivo y crítico en la profesión de enfermería: estado del arte. In Desarrollo del Pensamiento Crítico y Reflexivo en enfermería en México. Una visión colegiada, Cárdenas, B., L., Bardallo, P., M., D Ed.; Editorial Cigome, 2014; pp 23-47.

- Felton Valencia, A. C. El enfoque dialectico de la identidad enfermera. 2013.

- Nava Galán, M. G. Profesionalización, vocación y ética de enfermería. Revista de Enfermería Neurológica 2012, 11, 62. (acccessed 2024/02/05). [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Xumet, J.-E.; García-Hernández, A.-M.; Fernández-González, J.-P.; Marrero-González, C.-M. Beyond scientific and technical training: Assessing the relevance of empathy and assertiveness in future physiotherapists: A cross-sectional study. Health Science Reports 2023, 6, e1600. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Segura, N.; Fuentes-Aparicio, L.; Fajardo, S.; Querol-Giner, F.; Atef, H.; Sillero-Sillero, A.; Marques-Sule, E. Physical Therapists' Ethical and Moral Sensitivity: A STROBE-Compliant Cross-Sectional Study with a Special Focus on Gender Differences. Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Marques-Sule, E.; Baxi, H.; Arnal-Gómez, A.; Cortés-Amador, S.; Sheth, M. Influence of Professional Values on Attitudes towards Professional Ethics in Future Physical Therapy Professionals. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Chen, S.; Li, X.; Tan, C.; Li, W.; Zhong, C.; Mei, R.; Ye, M. Gender differences in empathy, emotional intelligence and problem-solving ability among nursing students: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today 2023, 120, 105649. [CrossRef]

- Delgado, N.; Bonache, H.; Betancort, M.; Morera, Y.; Harris, L. T. Understanding the Links between Inferring Mental States, Empathy, and Burnout in Medical Contexts. Healthcare (Basel) 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, V. S.; Guerrero, E.; Chambel, M. J. Emotional intelligence and health students' well-being: A two-wave study with students of medicine, physiotherapy and nursing. Nurse Educ Today 2018, 63, 35-42. [CrossRef]

- Lee, W. L.; Rambiar, P. N. I. M.; Rosli, N. Q. B.; Nurumal, M. S.; Abdullah, S. S. S.; Danaee, M. Impact of increased digital use and internet gaming on nursing students' empathy: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today 2022, 119, 105563. [CrossRef]

- Arda Sürücü, H.; Anuş Topdemir, E.; Baksi, A.; Büyükkaya Besen, D. Empathic approach to reducing the negative attitudes of nursing undergraduate students towards cancer. Nurse Educ Today 2021, 105, 105039. [CrossRef]

- Yucel, H. Empathy levels in physiotherapy students: a four-year longitudinal study. Physiother Theory Pract 2022, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhu, Y. L.; Xia, B. Y.; Li, Y. W.; Zhang, J. The effect of structured empathy education on empathy competency of undergraduate nursing interns: A quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ Today 2020, 85, 104296. [CrossRef]

- Unal, E.; Ozdemir, A. The effect of hybrid simulated burn care training on nursing students' knowledge, skills, and empathy: A randomised controlled trial. Nurse Educ Today 2023, 126, 105828. [CrossRef]

- Ward, A.; Mandrusiak, A.; Levett-Jones, T. Cultural empathy in physiotherapy students: a pre-test post-test study utilising virtual simulation. Physiotherapy 2018, 104, 453-461. [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.; Kweon, Y. Effects of a Nonviolent Communication-Based Empathy Education Program for Nursing Students: A Quasi-Experimental Pilot Study. Nurs Rep 2022, 12, 824-835. [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Wang, L.; Sun, J.; Li, D. Y.; Zheng, B. Y.; He, S. W.; Zhu, L. H.; Latour, J. M. Effectiveness of empathy clinical education for children's nursing students: A quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ Today 2020, 85, 104260. [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, E. M.; Diab, I. A.; Ouda, M. M. A.; Elsharkawy, N. B.; Abdelkader, F. A. The effectiveness of assertiveness training program on psychological wellbeing and work engagement among novice psychiatric nurses. Nurs Forum 2020, 55, 309-319. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liao, A. W. X.; Goh, S. H. L.; Yoong, S. Q.; Lim, A. X. M.; Wang, W. Effectiveness and quality of peer video feedback in health professions education: A systematic review. Nurse Educ Today 2022, 109, 105203. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).