1. Introduction: Dealing with Environment, Social and Governance Criteria (Past, Present and Future)

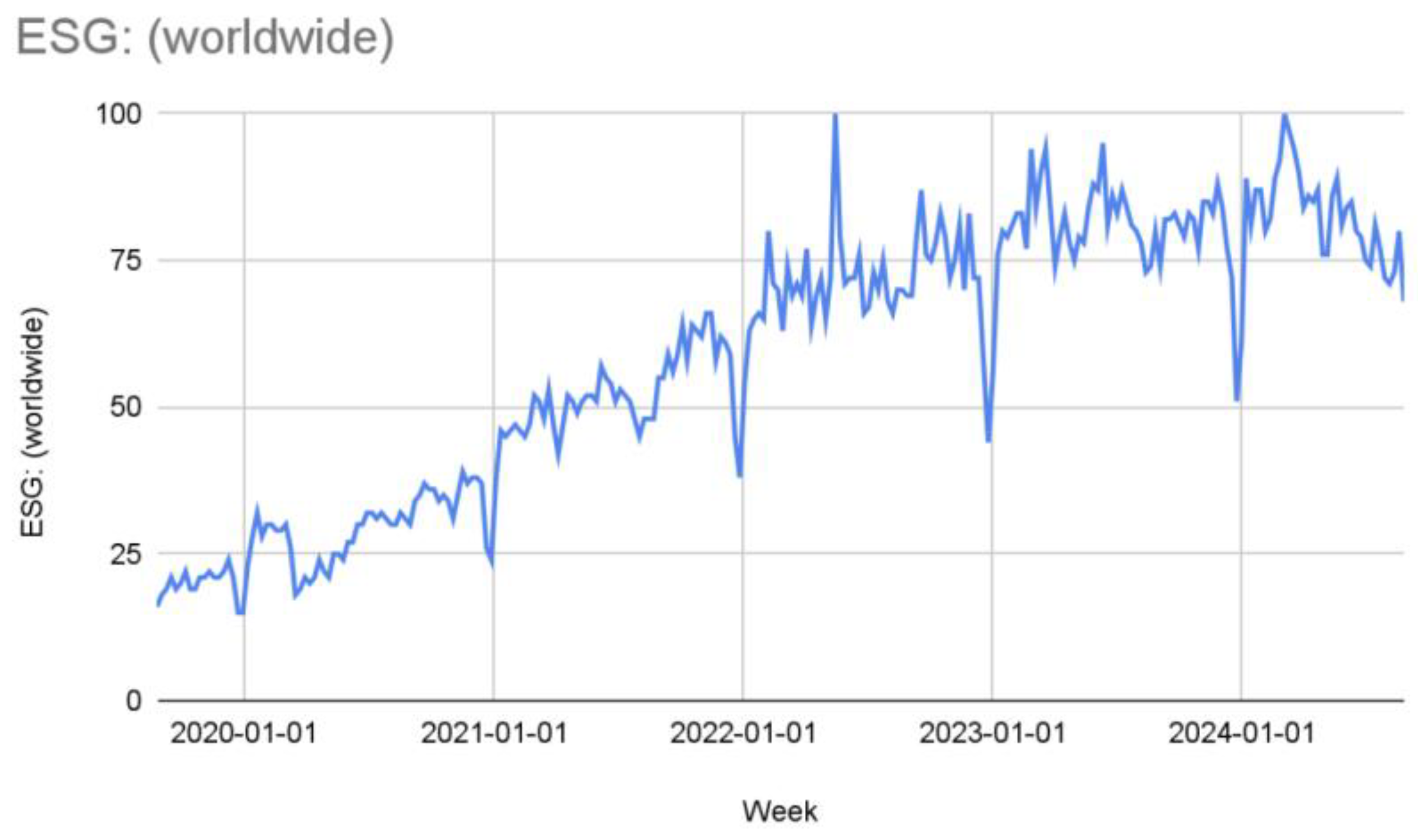

Quick research on Google Trends shows that interest in ESG and ESG-related issues is four times higher now than five years ago. The trend does not stop: the number is getting higher and higher as the understanding of Environmental, Social, and Governance factors (ESG) affecting corporate management and business policy is becoming paramount, irrespective of where we live.

Figure 1.

Google Trends graph showing the number of searches using “ESG” as a keyword.

Figure 1.

Google Trends graph showing the number of searches using “ESG” as a keyword.

This is also because of the issue's vague borders, as the acronym “ESG”, in its ambiguity, covers several fields related to economics, business, sociology, and, of course, the law [

47,

49,

53]. “ESG strategy” or just “ESG” refers to the need by companies (primarily MNEs) to pursue different goals in their routine activity beyond the maximisation of profits concerning the law.

The law does not set these goals. Instead, they stem from prominent stakeholders' different understandings of social relations [

85]. In this respect, far from binding, they are intended to be persuasive. If we use the ancient Roman law categories, we would say it’s a matter of

potestas rather than

auctoritas. These include environmental challenges, gender issues, social inclusiveness, etc [

85] (pag. 22).

EGS agenda soon intersected with taxation and tax policy concerns, as fiscal measures were often seen as ideal ways to stimulate such awareness. Proper tax policy is considered an accelerator to achieving the goals set by the stakeholders who insist on going beyond the traditional idea of business as a money-making activity [

8,

9]. However, the ESG agenda is mainly conceived as horizontal (addressing companies and individuals without government engagement).

Achieving ESG goals entails policymakers' broader vision at the institutional level. The basic idea is that a free market economy is the best economic growth and well-being option. Still, such freedom must be exercised consistently with needs and goals beyond the short-term return by MNEs: environment, inclusiveness, and respect for minorities are gaining traction and should be promoted as much as possible, far beyond the limits of the law. Public, binding law is inadequate to achieve this goal and convince MNEs to act consistently with the ESG standard: such an outcome should become a driver of the internal decision-making processes of the companies rather than being introduced from outside [

59].

In this respect, and these days, it is hard to hear dissenting opinions.

However, ESG strategy is still based worldwide on policy and soft law instruments. Although in some regions of the world (such as Europe

1) and specific states, ESG awareness has been transformed into positive law (that is, regulations and acts passed by national Parliaments and competent European bodies [

40,

63]), more and more needs to be done. The reason is simple: while there is a consensus on the necessity of introducing ESG criteria at several legislation levels, different opinions exist on assessing these goals and transferring a valuable idea into legally binding rules.

So far, in many countries, ESG is still either a soft law approach or a spontaneous, unilateral attitude of qualified companies (mostly MNEs), as the debate is in progress at various levels [

2].

The ESG project would consist of benchmarks, conditions, and parameters that companies must meet daily. Some of these requirements would demand disclosure of information concerning trade, while others would demand substantive actions.

The latter would include strategies to preserve the environment, increase renewables, respect minorities and people with different religious, social, and gender orientations, and so on [

85] (page 22). Although several papers have been published on the ESG criteria, there is a lack of consensus as to the actual boundaries of these policies, as some measures can be considered ESG relevant in some systems and others are not: this lack of standardisation is one of the pitfalls it will be addressed later in the paper.

Authors have already noted that taxation may play a role in fostering compliance. Still, most of the research carried out so far is aimed

pro futuro: it is dedicated to the possible impact deriving from the positivization of these criteria, that is, from their implementation via positive, hard law [

91].

Another question arises, and apparently, it hasn’t been investigated yet. It concerns the actual impact of the ESG criteria in the current legal system [

66]. Although these ESG-related policies are not binding, they might nonetheless play a role from an interpretive point of view. For instance, some expenses a business incurred to be ESG compliant that would fall outside the tax book as non-deductible for tax purposes might become significant. ESG compliance might become a driver of the interpretation of business choices by the companies, making relevant for tax purposes investments, depreciations and other accountancy decisions that wouldn’t be otherwise.

The legal nature of such criteria has to be investigated for this goal to be achieved [

52].

The first part of the paper shall be dedicated to the inception of the EGS criteria at the UN level, as the ESG issues have been tabled at the United Nations some 20 years ago for the first time [

85]. The point in this matter is whether such criteria can be considered an

acquis at the international level and part of human rights, as the UN has recently tabled

2. Should this be the case, ESG might become relevant from a legal perspective as a common principle accepted by most of the nation of a quasi-customary nature.

The second part of the paper will delve into EU law, checking the state of the art and the tax impact of the latest directives, such as the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive ((EU) 2022/2464).

The third and last part will try to conclude by arguing that EGS principles, uncertain as they are in terms of values to be pursued and principles to be endorsed, might already play an interpretive role in the daily implementation of tax rules, adjusting companies' tax liability in accordance with investments made and costs incurred.

This would be made possible by extending the scope of the business and making relevant costs for tax purposes outside the ordinary rules.

2. The Rise of ESG Awareness at the International Level

Entrepreneurial activity, like property, is regulated differently in several member states [71, 77, from an American perspective 80]. It is seriously limited in some due to the country's political orientation. In others, it might fall under the scrutiny of religious authorities or be conditioned by the latter's decision, although indirectly.

In most situations, and not only in so-called Western work, such an activity is free, and limitations by stature may be imposed only if necessary to meet overarching necessities or pursue a better higher goal.

In some countries, such as in the authors’ one, enterprise and property are not natural rights: they are granted only insofar as they prove to have a social value and to pursue a social goal (a “social function”) [

15].

Like freedom of the market economy, freedom of enterprise has been considered (and still is) the most efficient system of wealth governance worldwide [

74,

81]. Granting and fostering private initiatives has proved to be the best way to increase the well-being of the population in general. This is possible because the economy thrives when freedom is granted and (indirectly) because the business's success pays back to the community via taxes.

This conclusion, valid for individual initiatives, holds for associated businesses that routinely take the form of companies or corporations. In this respect, these entities have been created under the law to stimulate and foster initiatives further [

30]. There are remarkable distinctions amongst the various legal systems regarding the nature and functioning of corporations.

Yet one basic assumption has been held for decades, if not centuries: they are meant to maximise revenue and make the most of the business initiatives for the partners involved or, more recently, for the shareholders [

29].

Profit has been the most important and arguably the only compass for corporate activities worldwide.

Entrepreneurial activities have always been untested and unlimited. Value creation is always disruptive: goods and assets are destroyed to create new ones in Schumpeterian cycles. It is well known that several of these cycles create negative externalities in many contexts, including social, environmental, and human beings [

82].

Philosophers and academics have demonstrated that value creation does not exist in several circumstances but rather a value shift. Others have referred to rent-seeking phenomena [

55].

When such a shift occurs, ways and means are routinely introduced in the most advanced (or just sensitive) legal systems to re-introduce fairness in the community: such remedies are introduced or envisaged depending on the externality of the case. In recent situations, externalities have impacted social relations, the environment, and other shared aspects of life. In such cases, contract law, tort law, and eventually taxation have been used to compensate and offset entities that have suffered from the profit-making policy of corporations [

1]. For years, it was argued tort law and other ex-post remedies would suffice. Conversely, taxation would have contributed to reallocating profits, granting fairness, and consistently redistributing wealth with the constitutional principles of the case [

10,

23].

As time passed, it was observed from a policy point of view that such ex-post legal measures would not suffice and, in some cases, might conflict.

Most notably, in some situations, it was impossible to identify from a legal point of view the subject entitled to compensation or the legal remedy of the case [

24,

25,

46]. Eventually, some legal systems would fail to take adequate measures to prevent negative externalities that sometimes know no borders [

60].

In this respect, the role of global or local supranational organisations, such as the UN, the OECD, and the EU, becomes the pivotal element in a system overhaul to address the need for better social, environmental, and shared values, rights, and assets protection [

64].

A paradigm shift occurred, replacing (or coupling) the ex-post remedies with ex-ante ones with legal instruments (binding or persuasive) that would nudge or push the business activity to pursue other values and unfold consistently with a different agenda. Instead of promoting the protection of shared values and rights, international organisations argue that such a priority should become an element to be considered in every business's decision-making process [

47]. In other words, environmentally friendly policies (to give an example) were to be enacted not because of the fear of a possible tort liability or wrongdoing by the board of directors but rather because the need to respect the environment should derive from within to become a native element of the decision-making process [

53].

From an academic perspective, the keystone of the ESG strategy is the idea of internalising (ex-ante) elements that would play a role ex-post.

Stakeholders' sensibilities to these aspects date back decades for environmental and managerial aspects and arguably centuries for social factors [

12,

17,

70,

87]. In this respect, it isn't easy to give a date or a year in which this agenda started to be conceived.

Despite this, most of the literature refers to the 2004 report “Who Cares Wins,” which the Global Compact offered to the UN and endorsed by the latter. Since then, this has

de facto become the official UN position on the matter (see, for instance, the positions as they emerged at the High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (Rio de Janeiro, 2024)

https://hlpf.un.org/secretariat).

The report is a milestone in developing studies in sustainability. It codifies the Environmental, Social, and Governance criteria using the “ESG” acronym for the first time and spells out the strategy guidelines in this area.

Moreover, it identifies the lines of action in these fields, suggesting the measures to be taken by policymakers at the state level [

85]. The European intervention is coherent with the UN strategy [

18].

According to the UN strategy (the UN Global Compact), sound ESG-compliant legislation should be built on four distinctive pillars, embracing the three fields mentioned above.

These four pillars are human rights, labour, environment, and anti-corruption.

In the first area (human rights), businesses should be committed to their respect and asked for it by their trade counterparts. Human rights theory was developed in history to defend individuals from the illiberal and tyrannic measures of the states, ultimately making the rule of law prevail [

37,

67,

69,

78]. Under the human rights theory, no measure should be enforced, although valid, if this would violate these fundamental sets of rights [

36,

54,

57]. Of course, there is no space here to delve into details [

56,

62,

76]. Still, it is essential to remember that both Human rights have a critical role in the application of taxation, as literature has demonstrated [

4], and that academics and judiciary have argued that although conceived to be applied in a vertical direction (state versus individual), human rights can also be used to regulate relations between private persons, such as companies and other entities (that is horizontal: individual versus individual). This is the “

Drittwirkung Theory”, as prominent German academics [for a summary, 93] have developed it for the first time, and it has been subsequently embraced by the European Court of Human Rights [

13,

22], for example.

The second pillar is based on labour and encourages companies to comply with worker freedom of association, respect for children, and prevent discrimination.

The third pillar is dedicated to the environment and demands that environmental respect be prioritised in companies' decision-making processes. In this respect, nature preservation should be a key element in any decision regarding investments and technical solutions in the production system.

Eventually, the fourth is dedicated to anti-money laundering and the duty of transparency.

At first glance, there is no room for or mention of taxation in these fields. On the contrary, even if taxation has never been mentioned, it may play a role in implementing these strategies [

68], and the relevance of the pillars might help shape the tax rules as every member state introduces them.

Moreover, the influence of the ESG criteria differs for the four pillars.

For some of them, such as numbers 1 and 4, legally binding rules already exist regarding the implementation of this agenda: the ECHR (although at a regional level) and the international treaty on anti-money laundering (United Nations Convention against Corruption, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 2349, p. 41; Doc. A/58/422) [

72] are to be considered. However, they could be more coherent from a methodological point of view, with the EGS approach being an internal measure of every business and not an external constraint to business activity [

47].

The point is that both the ECHR and the international treaties are external measures that influence the business's decision-making processes; they are not built into it; they do not affect the internal choices of the board of directors.

Pillars 2 and 3, on the other hand, rely primarily on internal decisions, even though numerous international treaties are already in force.

None of them, though, address tax measures.

3. ESG and Taxation: Sample Case (Business Income, Transfer Pricing, GAAR)

The interplay between ESG and taxation has already been investigated in the literature [

43]. In several contributions, taxation has been scrutinised as a powerful tool to boost the implementation of the ESG principles [

91]: most of the analysis has been carried on at a policy level, in some respect

de iuere condendo (how the law should be).

This paper investigates how the ESG principles (identified above) might influence the current daily application of tax rules.

In this respect, four possible fields have been identified: (1) the calculation of business income, (2) the transfer pricing regulations and (3) the application of the anti-avoidance rules, with particular emphasis on (4) the business purposes test.

In general, EGS principles impact both international and domestic tax rules. If the country of the case is an EU member, the influence of EGS on EU law might also be considered.

3.1. The ESG Impact on Taxable Business Income Calculation

While the actual method for determining taxable business income depends on the specific legislation of the case, in most situations and countries around the world, it comes from accounting principles

3 and considers the company's balance sheet (see footnote 3 above). In this respect, income is calculated based on the revenue originating from the trade activity minus costs the business incurs (other items are also considered, but for simplicity’s sake, we limit the analysis to the costs relevant for calculating business income).

Costs' relevance for tax purposes depends on several factors regulated differently in every legislation. In general terms, a cost the business incurs is tax deductible if, among other things, the good or service the fee has been paid for is relevant to the company

4.

Suppose costs are incurred for a service not pertinent to the business activity (thus, not relevant for the profit calculation). In that case, they can not be tax deductible as not relevant to the business. This principle is expressed in different ways in the respective legal systems, but it is in some respects common [

42].

In most systems, this correlation is not codified or specifically regulated: it would be impossible to foresee in advance the kind of costs eligible for tax deduction. Consequently, this is one of the most relevant cases of principle-based legislation [

27], where a principle (correlation between the cost incurred and the profit generated) is left to the interpreter to decide.

ESG criteria may play an interpretive role in this respect, possibly expanding (or reducing) costs incurred for services or goods that, although not directly or relevant to profit generation, might be coherent with pursuing an ESG goal.

For instance, costs incurred for environmental protection purposes far beyond the limits set by the law, costs incurred by the company to stimulate more inclusive policies, and so on.

The ESG pillars mentioned above, working as interpretive principles [

6,

73], would be best when a tax-sensitive decision (whether to deduct the cost or not) has to be made.

A similar position might be taken in the case of transfer pricing.

3.2. The ESG Criteria’s Influence on Transfer Pricing

Academic literature has focused on transfer pricing since the late seventies of the newest century [

19]. The common understanding is that transactions between associated enterprises should be assessed for tax purposes based on the arm’s length principle: the market value of assets sold or services delivered should be considered to prevent tax planning strategies aimed at allocating the taxable profits of a multinational group in a jurisdiction where taxes are lower or on a company that could offset those (taxable) profits with losses.

ESG principles may cast a new light on this scenario, as most of the rules currently applicable in calculating the arm’s length price are essentially soft law ones [

11,

45,

90] aimed at replicating a situation where independent parties negotiate to maximise the respective profit. Most states rely on OECD guidance [

65] or UN rules [

88]. These two supranational organisations have developed a sophisticated set of rules and methods to identify the value to be considered for tax purposes when a transaction potentially triggering a transfer price case occurs.

Although different, these methods share a common background: they aim to determine the market value of the goods sold and services delivered. This means that the principle used in this case is the “fair” market value, or, so to say, the expected value/price, assuming that normality is correlated with the market under free competition [

3,

5]. It was observed above that the ESG approach to business rejects this understanding, as different elements are to be considered in defining a company's decision-making process compliant with ESG values [

26].

The Transfer Pricing regulations should target not all prices misaligned with the arm’s length rules but only those that do not pursue a coherent ESG goal. An MNE might accept (or demand) a higher price for a product purchased if it incorporates costs sustained by the seller (group member) to align with ESG values.

Therefore, during an audit, the business should be allowed to demonstrate that the pricing policy between associated enterprises has been chosen not for tax purposes but to achieve higher compliance with some ESG values at the group level. Of course, the burden of proof should be on the taxpayer's shoulders. Being sensitive to ESG issues in this situation would not demand any change to the law, as it would depend on the interpretive aspect [

50] of the transfer pricing discipline and the understanding of “market” value.

In conclusion, in that scenario and right now, the ESG system may play a significant role as an interpretive tool: it would interact with other rules and regulations set at an interpretive level, although in some regions, such as the EU, tentative efforts are in progress to codify transfer pricing rules in the matter.

3.3. The ESG Impact on The Business Purpose Test Clause (and on Anti-Avoidance Measures)

The third field where an ESG-oriented interpretation of the law might make a difference is understanding abuse and avoidance provisions [

32].

Tax avoidance is a field of taxation that has aroused the interests of academics for decades, if not centuries. The issue has been thoughtfully investigated at several states' international and European levels [

89].

Another inquiry in these pages would be useless. However, domestic legislators and international policymakers are always active in providing further guidance, changing the positive law, and adjusting the scope of anti-abuse provisions while seeking to address more complicated schemes or to comply, at best, with the BEPS framework [

31].

Even if the boundaries of avoidance are still uncertain [

34], the OECD and, consequently, national legislators have chosen one of the most significant perspectives: the “

sound business purpose test” or “

principal purpose test” in other contexts

5 [

92].

This is true in the European arena, for instance, where the CJEU has used the “business purpose test” in the past to assess the validity, for tax purposes, of qualified transactions and group reorganisations [

94].

Essentially, this test is a routine benchmark used to distinguish between two categories of business decisions: those that are coherent with the company's goal in the case and those whose goal is only to minimise the burden of taxation in a selected country.

Although consequences depend on the legislation of the case, once a transaction is deprived of any business purpose, it is not relevant for tax purposes either. For instance, if a purchase (determining a cost) is incurred without any business purpose, the cost is generally not tax deductible. Likewise, if an M&A is arranged only to minimise the tax burden, such advantages may be denied by the tax administration of the case.

In this respect, both literature and case law are abundant.

The point of interest, however, is the meaning of “business purpose” to be accepted.

Irrespective of the burden of proof (taxpayer or tax office), there is a common consensus that the core asset to be addressed is the business purpose: the broader the purpose, the narrower the scope of such an anti-avoidance provision [

39].

Academia hasn’t thoughtfully centred attention on this point, as it has been taken for granted that the purpose of every business is profit-making [

29]. Of course, differences exist in strategies leading to profits in the short or long run, but eventually, the goal would be to increase income attributable to the business.

This scenario is evident if the contrary proof is considered. A taxpayer who wants to pass the “sound business purpose test” has to demonstrate that any decision taken was coherent with such a strategy and that there was a rationale underneath the enterprise's strategic choices. For instance, a contract has been concluded because it seems reasonable that the conditions the parties agreed on would have been profitable.

Some legal systems, such as the Italian one, have dubbed this clause “reasonable business management” (for instance, Supreme Court (Corte di Cassazione) case n. 6972 decided on 8 April 2015). In other words, any business decision that falls outside the “reasonability test” is deprived of any relevance for tax purposes. Typically, this clause challenges decisions that would reduce the taxable income.

In some respects, any transaction targeted by the transfer pricing provisions would fall under this clause. If a company (a subsidiary, for instance) is forced (by the parent) to buy a product for a price higher than the marked price, it could trigger this clause. There would be no reason (hence the unreasonableness of choice) to buy something higher if the product is available for a lower cost and is purchased from somebody else.

The difference is that transfer pricing provisions work only between associated enterprises, while the “sound business test” does not.

The application of ESG principles disrupts this scenario. Under the ESG approach, the purpose of the business is not (only) profit; the company is required to pursue different goals simultaneously. In a classic situation, the purchaser buys a product for the lowest price possible, while the seller tries to negotiate for the opposite: the highest possible price. The outcome of the negotiation depends on several factors, but in general terms, the price shall fall within the bracket, ranging from the offer of one party to the willingness of the other. In such a situation, each step closer to the position of one of the parties is a step farther from the other. ESG criteria, introducing elements of fairness and inclusiveness to the transaction, should not be conflictual. In a perfect scenario, both parties should agree on the value attributed to the merchandise traded.

If we embrace the idea that the goal of the business is not just profit-making, then, as a consequence, we should be in the position to accept that market price and arm’s length rule are crucial in defining costs and revenues for tax purposes, but are not the only ones. Most notably, EGS factors should be considered, and the pricing policy should be justified to mirror a different understanding of the environment and social relations. The price set the parties agree on does not derive only from the trade's egoistic (unilateral) opinions but from other factors of a non-conflictual nature [].

Such awareness should not be confused with the routine “trickle-down” effect of increased costs determined by pursuing green policies or inclusive strategies.

Of course, higher investments in the first and second sectors would entail a higher cost for the products sold or the services delivered. The ordinary rules falling under the transfer pricing regulation would cover such an increase. However, it is possible that the client's ESG consideration would influence a company's pricing policy in an attempt to expand the impact of ESG strategy on the overall business.

For example, an MNE would charge clients different prices depending on their compliance with specific values. In extreme cases, it would only negotiate with some clients if they complied with a determined standard, making it easier for the company to access qualified lines of funding from banks.

In the first of the two cases, a discrepancy in the pricing policy would occur just for ESG purposes, irrespective of the actual cost marked up [

91].

Consequently, it is possible to argue that the classic transfer pricing guidance would not capture some ESG-induced price dynamics, and adaptations are necessary.

De iure condito (considering the law for what it is), it is possible to argue that most of the methods to be used to assess the arm’s length value are best practices, as far as no state has ever introduced (at least in Europe) binding provisions obliging the tax office to proceed according to CUP or TNMM, for example.

On the contrary, it is true that in most legislations, reference to market prices or values is considered. It is not easy to understand what “fair market” value means to the purpose and whether a difference exists between value and cost to this extent.

This is an interpretive challenge that the courts of the tax office can address, rethinking the notion of “market” as specified above in a way that is not different from the understanding of business or enterprises.

3.4. Redesigning the Concept of Market Economy and its Impact on Market-oriented Tax Systems (and on the Application of a GAAR)

So far, it has been demonstrated that the modern mindset, ESG values-oriented business, and “enterprise” are not money-making machines but that this goal has to be coupled with other relevant achievements: equal opportunities, inclusiveness, and sustainability, to name a few [

85].

The same reasoning, in analogical terms, could be used for the idea of a market, which has been too long connected to the classic idea of a place (virtual or physical) where the individual interests of the parties determine prices. One of the pillars of market economies is that individuals' egoistic approach might have a positive externality on the community, and the more an individual is free to pursue his interests, the better it is for the community as a whole.

The ESG-oriented policy would demand that we relinquish this unilateralism and be ready to embrace pricing calculation methods that consider the other goals to be pursued [

58].

Further guidance and operative instruction from the relevant stakeholders are needed to achieve this goal.

If we accept that implementing the ESG system (in the principle of the law) might play a role in reshaping the business purpose test clause, we should be able to accept its influence in defining the scope of a GAAR.

General anti-avoidance rules depend on the context [

61]. Some are influenced by Civil law, others by Common law [

34], and, of course, within the EU, we have a coupon definition provided by the ATAD-1 directive [

33].

Eventually, the BEPS project played a role either in shaping its understanding.

Just like in the case discussed above, there’s no room here to delve into the details of a GAAR as several prominent authors have already addressed the issue, and the debate has been going on for decades.

Despite the different perspectives and the rules applicable, the case of GAAR is a principles-based situation [

27], avoiding behaviour that defies a principle without defying specific regulations of the system (hence the necessity of a GAAR). Most of the authors, in addressing avoidance, consider it as a possible breach of the good faith principle [

32]; others refer to fairness [

38,

44], and eventually, some others to the reasonableness of the relationship between the tax authority and taxpayer [

35]. Most tax avoidance schemes do not violate the law (as it would be evasion); they defy this sort of good relationship at a systemic level.

In redesigning the legal system's overarching principles, EGS might contribute to fine-tuning the GAAR's application without formally affecting it.

In some cases, avoidance schemes have been said to violate the duty to pay taxes and the solidarity that should operate between members of the same community. In some Supreme Court decisions, avoidance has been connected directly with the duty to pay taxes, which is intended as a general principle of the system (see, for instance, Italian Supreme Court (Corte di Cassazione) cases n. 30055, 30056, and 30057, decided on 23 December 2008).

Anti-avoidance strategies are, in this respect, prompted by principle-based legislation and are system-dependent: the more a legal (e.g., tax system) is solidarity-oriented, the more the anti-avoidance provisions might be expected to be aggressive (or aggressively interpreted by the courts and the tax office). The more a system is liberal in the political sense of the word, the more freedom of enterprise and literal interpretation of the law should prevail.

The ESG principle, advocating a higher level of commitment by different businesses to the enterprise's social impact, should play a role in this respect. It could expand the scope of the provisions, eventually qualifying behaviours that would not otherwise, depending on the circumstances of the case, as “in avoidance of the (tax) law.”

The relevance of the circumstances of the case is justified by the fact that ESG philosophy should not be understood as a proxy for economic solidarity but rather as a different agenda that might overlap in some respects with the duty of solidarity [

75].

The point is that the ESG application (or, more precisely, the ESG-oriented interpretation of a GAAR) would not ultimately increase the latter's scope in general terms but in its expansion only in selected cases. Namely, those in potential conflict with ESG principles as specified in the taxonomy (Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2020 on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment and amending Regulation (EU) 2019/2088) [

79] or the 2004 report by the UN [

85].

In the case of the UN, the last aspect to be addressed concerns the interpretive role of the ESG principles, considering that no formal codification exists, and their extension has never been formalised officially in a legal text.

Consequently, the question that needs answering is whether the ESG principles play an interpretive role while lacking such a formal acknowledgement.

A positive answer seems possible.

4. The Role of the UN in Shaping the Environmental, Social and Governance Criteria

Sources of law depend on the system of the case, but at the international level, a common understanding exists about them. Customary law is, for instance, widely recognised as a source, although debate exists about its actual content. Treaty-based law is also a crucial element in the international legal system and, as a consequence, of several domestic ones.

In addition to these widely recognised sources of law, a significant position is attributed to the “

general principles of the law as they are recognised by civilised nations” (Article 38 (1) (c), Statute of the International Court of Justice) [

86]. Such principles (

general principles) also play a role in making EU law [

48,

51,

84]. The Court of Justice of the European Union routinely uses them in its decision-making processes [

7].

Human rights are also essential and play a role in making international law, irrespective of their regional recognition, such as in the European Convention on Human Rights case. In this respect, the link between ESG and human rights should be considered for this analysis [see UN, Investors, environmental, social and governance approaches and human rights Report, Human Rights Council Fifty-sixth session 18 June–12 July 2024, A/HRC/56/55, 2 May 2024].

Consequently, it is crucial to see whether the ESG principles might be considered general principles in the above-specified meaning.

According to mainstream literature [

48], such principles can arise both from the national legal systems and from the international system: in the case of ESG, the second option would be the most appropriate one, as not all states are currently engaged in the ESG revolution, although many of them are developing their policies in the matter.

According to the literature, general principles also have a regional scope and local application (not necessarily global) [

14].

The same literature concedes that the “recognition” does not require a formal statement. Still, it may stem from the routine application and the idea that these principles should be upheld and used in the legal system. There’s no specification as to their positive impact. Consequently, such principles can be binding per se or helpful in understanding the law, which finds its source elsewhere.

In this latter extension, we deal with interpretive principles, precisely the nature of the ESG this paper upholds. In this respect, ESG would not become per se a source of the law as under Article 38(1) of the ICJ statute. Instead, they would help to understand the extension of other rights.

However, other conditions must be met for a principle to qualify for this influence on the international and domestic legal systems.

For a rule to become a general principle of law formed within a legal system [

21] several conditions must be met. It has to be recognised in treaties and other international instruments; it should underlie general rules of international and customary law, and eventually, it should be inherent in the basic features and fundamental requirements of the international legal system.

The ESG principles, or at least their core, meet all these conditions as they emerge together. All countries worldwide agree on environmental, social, and policy issues, although with a different intensity.

Even if all the states have taken no explicit action, a consensus exists, and it is undeniable [

85]. Moreover, several prominent stakeholders have endorsed this situation. Lately, the UN has made a formal statement connecting the ESG agenda with human flights, reinforcing the common understanding of the

idem sentire [ see UN, Investors, environmental, social and governance approaches and human rights Report, Human Rights Council Fifty-sixth session 18 June–12 July 2024, A/HRC/56/55, 2 May 2024].

The latest steps by the EU with the taxonomy regulation (Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2020 on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment and amending Regulation (EU) 2019/2088) are in this direction. ESG are common principles shared by civilised nations, and eventually, their application (at the interpretive level) will become an undeniable feature of all legal systems.

5. Concluding Remarks: The Road Ahead (and a Possible Map)

For years, the ESG roadmap has swung between being a buzzword (a fashion issue) or one of the most promising drivers of change in the countries' legal systems, capable of striking a balance between common well-being and sustainable growth. As time passes, the second understanding prevails.

ESG values, as defined in the four pillars codified in 2004, are gaining traction in the business world, and more and more MNEs are directly and indirectly becoming compliant. The EU is tabling new proposals to strengthen CSR

6 [

16,

83], closely connected with ESG. However, the uncertainty of their borders makes them volatile and exposed to manipulation by stakeholders outside the democratic control system [

28]. These would be in the condition of setting priorities for the business world and hijacking decisions that should be taken according to the market forces or agendas set by elected constituencies.

Yet the risk seems worthwhile, considering the international community's need for sustainable growth. The ESG principles would also play a pivotal role in shaping the tax system of the following decades, introducing principle-based legislation, a focused environment, and the growth we need.

Taxation may stimulate this agenda, but the opposite is also true. The development of an ESG-consistent economy would demand countries to adjust taxes according to the commitment of the MNEs to this purpose.

For the time being, the ESG can not be considered binding rules. Still, interpretive guidance can adjust the implementation of rules and regulations that international tax law is familiar with, bending their application to the new agenda.

Consequently, the judiciary can interpret the law using ESG criteria defined by the UN. The tax office should also consider them in the routine application of anti-avoidance measures or the opted regulations specified above.

The EU's attempt to codify these values and include them in EU law would foster this trend and make their application more solid and robust. In the long run, however, their application is a way of enforcing the solidarity principle, which should contribute to the overall burden of taxation.

A company (MNE or not) that is ESG compliant demonstrates the will to support common welfare and pursue a shared goal. Doing so and acting consistently with ESG values diverges from the profit-maximization paradigm on which taxation is built.

In other words, taxes are written and enforced assuming the taxpayer is a rational economic player seeking to maximise revenue. Should this not be the case anymore (as ESG applications would demand), tax applications should be adjusted accordingly.

Funding

This research has been funded under the FIRD 2023 programme by the University of Ferrara.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the support and the assistance provided by Ms. Anna Miotto in the research phase and of the TRN – Tax Research Network Steering Committee for the invaluable suggestions and feedbacks received during the 2023 Annual Conference at the University of Cardff.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

| 1 |

Directive (EU) 2022/2464 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 amending Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Directive 2013/34/EU, as regards corporate sustainability reporting. The directive has entered into force on 5 january 2023. |

| 2 |

UN, Investors, environmental, social and governance approaches and human rights Report, Human Rights Council Fifty-sixth session 18 June–12 July 2024, A/HRC/56/55, 2 May 2024. |

| 3 |

For instance in the UK “The profits of a trade must be calculated in accordance with generally accepted accounting practice, subject to any adjustment required or authorised by law in calculating profits for corporation tax purposes.” Corporation Tax Act 2009, Chapter 3, 46(1). |

| 4 |

See footnote 3: “In the Corporation Tax Acts, in the context of the calculation of the profits of a trade, references to receipts and expenses are to any items brought into account as credits or debits in calculating the profits (...)” 48(1). |

| 5 |

Principal pupose test clause is introduced under Article 29 (9) OECD Model Convention reads as follows: Notwithstanding the other provisions of this Convention, a benefit under this Convention shall not be granted in respect of an item of income or capital if it is reasonable to conclude, having regard to all relevant facts and circumstances, that obtaining that benefit was one of the principal purposes of any arrangement or transaction that resulted directly or indirectly in that benefit, unless it is established that granting that benefit in these circumstances would be in accordance with the object and purpose of the relevant provisions of this Convention. |

| 6 |

Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 amending Directive 2013/34/EU as regards disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups. |

References

- Aragão, Alexandra. “Polluter-Pays Principle.” In Encyclopedia of Contemporary Constitutionalism, 1–24. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022.

- Arvidsson, Susanne. Challenges in Managing Sustainable Business: Reporting, Taxation, Ethics and Governance. Edited by Susanne Arvidsson. 1st ed. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2018.

- Baistrocchi, Eduardo A. “The International Tax Regime and the BRIC World: Elements for a Theory.” Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 33, no. 4 (2013): 733–66. [CrossRef]

- Baker, Philip. “Some Recent Decisions of the European Court of Human Rights on Tax Matters.” European Taxation 55, no. 2/3 (2015): 250. [CrossRef]

- Behrens, Kristian, Susana Peralt, and Pierre M. Picard. “Transfer Pricing Rules, OECD Guidelines, and Market Distortions.” Journal of Public Economic Theory 16, no. 4 (August 10, 2014): 650–80. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, Andrea. “The Game of Interpretation in International Law: The Players, The Cards, and Why the Game Is Worth the Candle.” In Interpretation in International Law, edited by Andrea Bianchi, Daniel M. Peat, and Mattews Windsor, 34–60. books.google.com, 2015.

- Bobek, Michal. “The Court of Justice of the European Union.” The Oxford Handbook of EU Law. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2015, 153–77.

- Bonham, Jonathan, and Amoray Riggs-Cragun. “Motivating ESG Activities through Contracts, Taxes and Disclosure Regulation.” Chicago Booth Research Paper, no. 22–05 (2022): 1–53. [CrossRef]

- Bressan, Silvia. “ESG, Taxes, and Profitability of Insurers.” Sustainability 18, no. 15 (September 20, 2023): 13937. [CrossRef]

- Brokelind, Cécile, ed. Principles of Law: Function, Status and Impact in EU Tax Law. Amsterdam, Netherlands: IBFD Publications, 2014.

- Calderón, José. “The OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines as a Source of Tax Law: Is Globalization Reaching the Tax Law?” Intertax 35, no. 1 (2007): 4–29.

- Churchville, Sara. “The Roles of the Board in the Era of ESG and Stakeholder Capitalism: Overview and Key Insights.” The Conference Board. United States of America. Policy Commons, 2023.

- Clapham, Andrew. “The ‘Drittwirkung’ of the Convention.” In The European System for The Protection of Human Rights, edited by Ronald Macdonald, Franz Matscher, and Herbert Petzold, 163–206. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 1993.

- Conforti, Benedetto, and Massimo Iovane. Diritto internazionale. Naples: Editoriale Scientifica, 2021.

- Cornelius, Nelarine, Mathew Todres, Shaheena Janjuha-Jivraj, Adrian Woods, and James Wallace. “Corporate Social Responsibility and the Social Enterprise.” Journal of Business Ethics 81, no. 2 (2008): 355–70. [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, Francesca, Silvia Gaia, Claudia Girardone, and Stefano Piserà. “The Effects of the EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive on Corporate Social Responsibility.” The European Journal of Finance 30, no. 7 (May 2, 2024): 726–52. [CrossRef]

- Daugaard, Dan, and Ashley Ding. “Global Drivers for ESG Performance: The Body of Knowledge.” Sustainability 14, no. 4 (February 18, 2022): 2322. [CrossRef]

- Delaney, Denise, and Stewart Philip. “Study on Sustainability-Related Ratings, Data and Research.” European Commission, 2021.

- Eden, Lorraine. “Taxes, Transfer Pricing, and the Multinational Enterprise.” The Oxford Handbook in International Business, Oxford University Press: Oxford 591 (2001): 619. [CrossRef]

- Eleftheriadis, Pavolos. “The Primacy of EU Law: Interpretive, Not Structural.” European Papers 8, no. 3 (2024): 1255–91. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Jaye. “General Principles and Comparative Law.” European Journal of International Law 22, no. 4 (2011): 949–71. [CrossRef]

- Engle, Eric. “Third Party Effect of Fundamental Rights (Drittwirkung).” Hanse Law Review 5, no. 2 (2009): 165–73.

- Englisch, Joachim. “Ability to Pay in European Tax Law.” In Principles of Law: Function, Status and Impact in EU Tax Law, edited by Cécile Brokelind, 439–64. Amsterdam, Netherlands: IBFD Publications, 2014.

- Faure, Michael. “Regulatory Strategies in Environmental Liability.” In The Regulatory Function of European Private Law, edited by Fabrizio Cafaggi and Horatia Watt. Cheltenham, England: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2009.

- Faure, Michal, and Marjan Peeters. “Liability and Climate Change.” Journal of Environmental Law 24, no. 2 (2012): 385–87.

- Fonseca, Jacob. “ESG Investing: How Corporate Tax Avoidance Affects Corporate Governance & ESG Analysis.” Illinois Business Law Journal 25, no. 1 (2020): 1–18.

- Freedman, Judith. “Improving (Not Perfecting) Tax Legislation: Rules and Principles Revisited.” British Tax Review 32, no. 6 (2010): 717.

- Freitas Netto, Sebastião Vieira de, Marcos Felipe Falcão Sobral, Ana Regina Bezerra Ribeiro, and Gleibson Robert da Luz Soares. “Concepts and Forms of Greenwashing: A Systematic Review.” Environmental Sciences Europe 32, no. 19 (2020): 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, Milton. “A Friedman Doctrine-- The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits.” New York Times, September 13, 1970.

- Gindis, David. “Conceptualizing the Business Corporation: Insights from History.” Journal of Institutional Economics 16 (April 28, 2020): 569–77. [CrossRef]

- Ginevra, Guglielmo. “The EU Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive and the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Action Plan: Necessity and Adequacy of the Measures at EU Level.” Intertax 45, no. 2 (2017): 120–37. [CrossRef]

- Greggi, Marco. “Avoidance and Abus de Droit: The European Approach in Tax Law.” eJournal of Tax Research 6, no. 1 (2008): 23.

- ———. “The EU Directive Against Tax Avoidance (ATAD 1).” In Contemporary Issues in Tax Research, edited by Emer Mulligan and Lynne Oats, 1–21. Birmingham: Fiscal Publications, 2017.

- Greggi, Marco, and Ken Devos. “A Comparison of Common Law and Civil Law GAARs: The Cases of Australia and Italy.” International Tax Law Review (RDTI) 21, no. 1 (2016): 17–46.

- Gribnau, Hans. “Corporate Social Responsibility and Tax Planning: Not by Rules Alone.” Social & Legal Studies 24, no. 2 (2015): 225–50. [CrossRef]

- Hannum, Hurst, S. James Anaya, Dinah L. Shelton, and Rosa Celorio. International Human Rights: Problems of Law, Policy, and Practice. 7th ed. Aspen Casebook. Philadelphia, PA: Aspen, 2023.

- Harpaz, Guy. “The European Court of Justice and Its Relations with the European Court of Human Rights: The Quest for Enhanced Reliance, Coherence and Legitimacy.” Common Market Law Review 46, no. 1 (2009): 105–41. [CrossRef]

- Hemels, Sigrid. “Fairness and Taxation in a Globalized World.” Journal of Osaka University of Economics 66, no. 4 (2015): 237. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, L. “Tax Avoidance.” British Tax Review 2 (2005): 197–206.

- Hummel, Katrin, and Dominik Jobst. “An Overview of Corporate Sustainability Reporting Legislation in the European Union.” Accounting in Europe, 2024, 1–36. [CrossRef]

- Jones, John Avery. “Tax Law: Rules or Principles?” Fiscal Studies 17, no. 3 (1996): 63.

- Kayis-Kumar, Ann, Peter Mellor, and Chris Evans. “The Deductibility of Tax-Related Expenses: Historical and Comparative Perspectives.” Australian Tax Review 48, no. 2 (2019): 100–116.

- Knuutinen, Reijo, and Matleena Pietiläinen. “Responsible Investment: Taxes and Paradoxes.” Nordic Tax Journal 2017, no. 1 (2017): 135–50. [CrossRef]

- Kogler, Christoph, and Erich Kirchler. “Taxpayers’ Subjective Concepts of Taxes, Tax Evasion, and Tax Avoidance.” In Ethics and Taxation, 191–205. Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2020.

- Lasiński-Sulecki, Krzysztof. “OECD Guidelines. Between Soft-Law and Hard-Law in Transfer Pricing Matters.” Comparative Law Review 17, no. 1 (2014): 63–79. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Maria. “Tort, Regulation and Environmental Liability.” Legal Studies (Society of Legal Scholars) 22, no. 1 (2002): 33–52.

- Leins, Stefan. “‘Responsible Investment’: ESG and the Post-Crisis Ethical Order.” Economy and Society 49, no. 1 (2020): 71–91. [CrossRef]

- Lenaerts, Koen. “The Rule of Law and the Coherence of the Judicial System of the European Union.” Common Market L. Rev. 44, no. 6 (2007): 1625–59. [CrossRef]

- Li, Ting-Ting, Kai Wang, Toshiyuki Sueyoshi, and Derek D. Wang. “ESG: Research Progress and Future Prospects.” Sustainability 13, no. 21 (2021): 11663. [CrossRef]

- Lohse, T., Nadine Riedel, and C. Spengel. “The Increasing Importance of Transfer Pricing Regulations: A Worldwide Overview.” Intertax 42, no. 6/7 (2014): 352–404.

- Lorenz, Werner. “General Principles of Law: Their Elaboration in the Court of Justice of the European Communities.” The American Journal of Comparative Law 13, no. 1 (1964): 1. [CrossRef]

- Martinho, Sandra. “Looking at the‘ Tax’ in ESG through a Sustainable Investor Lens.” Intergovernmental Org. In-House Couns. J. 1, no. 2 (2022): 29–41.

- Matos, Pedro. ESG and Responsible Institutional Investing around the World: A Critical Review. London: CFA Institute Research Foundation, 2020.

- Mazzeschi, Riccardo Pisillo. International Human Rights Law: Theory and Practice. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature, 2021.

- Mazzucato, Mariana. The Value of Everything: Making and Taking in the Global Economy. Boston, MA: Hachette Book Group, 2018.

- Mertens, Thomas. A Philosophical Introduction to Human Rights. Law in Context. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- Mertus, Julie. The United Nations and Human Rights: A Guide for a New Era. Global Institutions. London, England: Routledge, 2005.

- Michels-Kim, Nina, and Tae Hyoung Kim. “Transfer Pricing Strategies for the New Normal.” Strategic Finance 104, no. 3 (2022): 24–31.

- Milne, Janet E. “Environmental Taxation and ESG: Silent Partners: Between Public and Private Solutions.” In Sustainable Finances and the Law, edited by Rute Saraiva and Paulo Alves Pardal, 16:253–79. Economic Analysis of Law in European Legal Scholarship. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024.

- Morriss, Andrew P., and Roger E. Meiners. “Borders and the Environment.” Environmental Law 39 (2009): 141.

- Mosquera Valderrama, Irma, Addy Mazz, Luís Eduardo Schoueri, Natalia Quiñones, Craig West, Pasquale Pistone, and Frederik Zimmer. “Tools Used by Countries to Counteract Aggressive Tax Planning in Light of Transparency.” Intertax 46, no. 2 (2018): 140.

- Neier, Aryeh. The International Human Rights Movement: A History. 2nd ed. Human Rights and Crimes against Humanity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020.

- Odobaša, Rajko, and Katarina Marošević. “Expected Contributions of the European Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) to the Sustainable Development of the European Union.” EU and Comparative Law Issues and Challenges Series 7, no. 1 (2023): 593–612.

- OECD. Environmental Justice: Context, Challenges and National Approaches. OECD, 2024.

- ———. OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations 2017. OECD Publishing, 2017.

- Ooi, Vincent, and Alvin W-L See. “Promoting ESG Investing by Trustees: Risk Management and Structuring Solutions.” King’s Law Journal: KLJ 35, no. 1 (January 2, 2024): 68–88. [CrossRef]

- Ovádek, Michal. “The Rule of Law in the EU: Many Ways Forward but Only One Way to Stand Still?” Journal of European Integration 40, no. 4 (2018): 495–503. [CrossRef]

- Parchomovsky, Gideon, and Danielle A. Chaim. “The Missing ‘T’ in ESG.” Vanderbilt Law Review 77, no. 3 (2024): 789–843.

- Peerenboom, Randall. “The Future of Rule of Law: Challenges and Prospects for the Field.” Hague Journal on the Rule of Law 1, no. 1 (2009): 5–14. [CrossRef]

- Pierre, Jon. “Thematic Review: Reinventing Governance, Reinventing Democracy?” Policy and Politics 37, no. 4 (2009): 591–609. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez de Santiago, José María, and Luis Arroyo Jiménez. “A Silent Revolution. Property and Free Enterprise Before the Spanish Constitutional Court.” In Fundamental Rights Challenges, edited by Cristina Izquierdo-Sans, Carmen Martínez-Capdevila, and Magdalena Nogueira-Guastavino, 289–98. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021.

- Rose, Cecily, Michael Kubiciel, and Oliver Landwehr, eds. The United Nations Convention against Corruption: A Commentary. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Rösler, Hannes. “Interpretation of EU Law.” In Max Planck Encyclopedia of European Private Law, 2:979–82. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Max-Planck-Institut für Europäische Rechtsgeschichte, 2012. https://www.humanitas.lt/uploads/Products/product_196908/9780199578955.pdf.

- Rothbard, Murray N. The Essential Von Mises. Bramble Minibooks, 1973.

- Sangiovanni, Andrea. “Solidarity in the European Union.” Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 33, no. 2 (June 1, 2013): 213–41. [CrossRef]

- Sarat, Austin, and Thomas R. Kearns. “The Unsettled Status of Human Rights: An Introduction.” In Human Rights: Concepts, Contests, Contingencies, edited by Austin Sarat and Thomas R. Kearns, 1–24. Amherst Series in Law, Jurisprudence & Social Thought. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2001.

- Schepel, Harm. “Constitutionalising the Market, Marketising the Constitution, and to Tell the Difference: On the Horizontal Application of the Free Movement Provisions in EU Law: Horizontal Application of Free Movement Provisions.” European Law Journal 18, no. 2 (2012): 177–200. [CrossRef]

- Schukking, Jolien. “Protection of Human Rights and the Rule of Law in Europe: A Shared Responsibility.” Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 36, no. 2 (2018): 152–58. [CrossRef]

- Sica, Francesco, Francesco Tajani, Paz Sáez-Pérez, and José Marín-Nicolás. “Taxonomy and Indicators for ESG Investments.” Sustainability 15, no. 22 (2023): 15979. [CrossRef]

- Siegan, Bernard H. Economic Liberties and the Constitution. New York: Routledge, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, Thomas D. Rethinking Economic Behaviour: How the Economy Really Works. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000.

- Sjåfjell, Beate. “Internalizing Externalities in EU Law: Why Neither Corporate Governance nor Corporate Social Responsibility Provides the Answers.” The George Washington International Law Review 40, no. 4 (2008): 977–1024.

- Szabó, Dániel Gergely, and Karsten Engsig Sørensen. “New EU Directive on the Disclosure of Non-Financial Information (CSR).” European Company and Financial Law Review 12, no. 3 (2015): 307–40. [CrossRef]

- Tamm, Ditlev. “The History of the Court of Justice of the European Union Since Its Origin.” In The Court of Justice and the Construction of Europe: Analyses and Perspectives on Sixty Years of Case-Law - La Cour de Justice et La Construction de l’Europe: Analyses et Perspectives de Soixante Ans de Jurisprudence, 9–35. The Hague, The Netherlands: T. M. C. Asser Press, 2013.

- The Global Compact. “Who Cares Wins.” United Nations, 2004.

- Thirlway, Hugh. The Sources of International Law. London, England: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Tsang, Albert, Tracie Frost, and Huijuan Cao. “Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosure: A Literature Review.” The British Accounting Review 55, no. 1 (2023): 101149. [CrossRef]

- UN. “Practical Manual on Transfer Pricing for Developing Countries.” New York: United Nations, 2021. http://www.un.org/esa/ffd/documents/UN_Manual_TransferPricing.pdf.

- Vanistendael, F. J. G. M. “Can EU Tax Law Accommodate a Uniform Anti-Avoidance Concept?” In Practical Problems in European and International Tax Law, edited by H. Jochum, P. H. J. Essers, M. Lang, N. Winkeljohann, and B. Wiman, 2:73. Amsterdam: IBFD, 2006.

- Vega, Alberto. “International Governance through Soft Law: The Case of the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines.” Transtate Working Papers, no. 163 (2012): 1–37.

- Weaver, Brett, François Marlier, Kpmg Global, Matthew Whipp, and Søren Dalby. “ESG Tax Transparency: The Global Journey.” International Tax Review, 2022, 1–7.

- Weeghel, Stef van. “A Deconstruction of the Principal Purposes Test.” World Tax Journal 11, no. 1 (January 17, 2019): 3–45. [CrossRef]

- Wissenschaftliche Dienste. “Drittwirkung von Grundrechten.” Deutscher Bundestag, 2023.

- Zalasiński, A. “Proportionality of Anti-Avoidance and Anti-Abuse Measures in the ECJ’s Direct Tax Case Law.” Intertax 35, no. 5 (2007): 310–21. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).