1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which occurs when microbes evolve to be no longer susceptible to drugs once used to treat the infections they cause, poses a worldwide challenge to human and animal health [

1,

2]. More than two-thirds of antibiotics globally are used for livestock [

3], with animal-sourced food production commonly identified as a key driver of antibiotic overuse [

4]. The (over)use of antibiotics in livestock is undoubtedly a serious concern but blaming the livestock industry is a reductionist approach. The health effects of antibiotic resistance – like many of the problems of the Anthropocene – sit at the end of a complex causal chain comprising underlying drivers, ecological drivers, proximal causes and mediating factors [

5] none of which should be considered in isolation.

Planetary health advocates for a complex systems approach to human health [

6,

7,

8]: systems thinking and complexity is one of the five pillars of the field, set out in the Planetary Health Educational Framework [

9]. Planetary health also advocates respect for indigenous knowledge and worldviews, and recognition of their value [

10,

11,

12] as such views can help humanity re-engage with nature and pull back from the more damaging behaviours that have characterised the Anthropocene, such as overconsumption and environmental pollution [

13].

This paper explains how a planetary health framing can help to identify the complex factors that compromise human, animal and environmental health, and how they intersect. We use a case study that shows how the impact of climate change and the erosion of indigenous cattle management practices drives antibiotic use in cattle in Kwara State, Nigeria, the largest country in Western sub-Saharan Africa. This is the region of the world most adversely affected by AMR, with mortality rates twice that of Western Europe [

15].

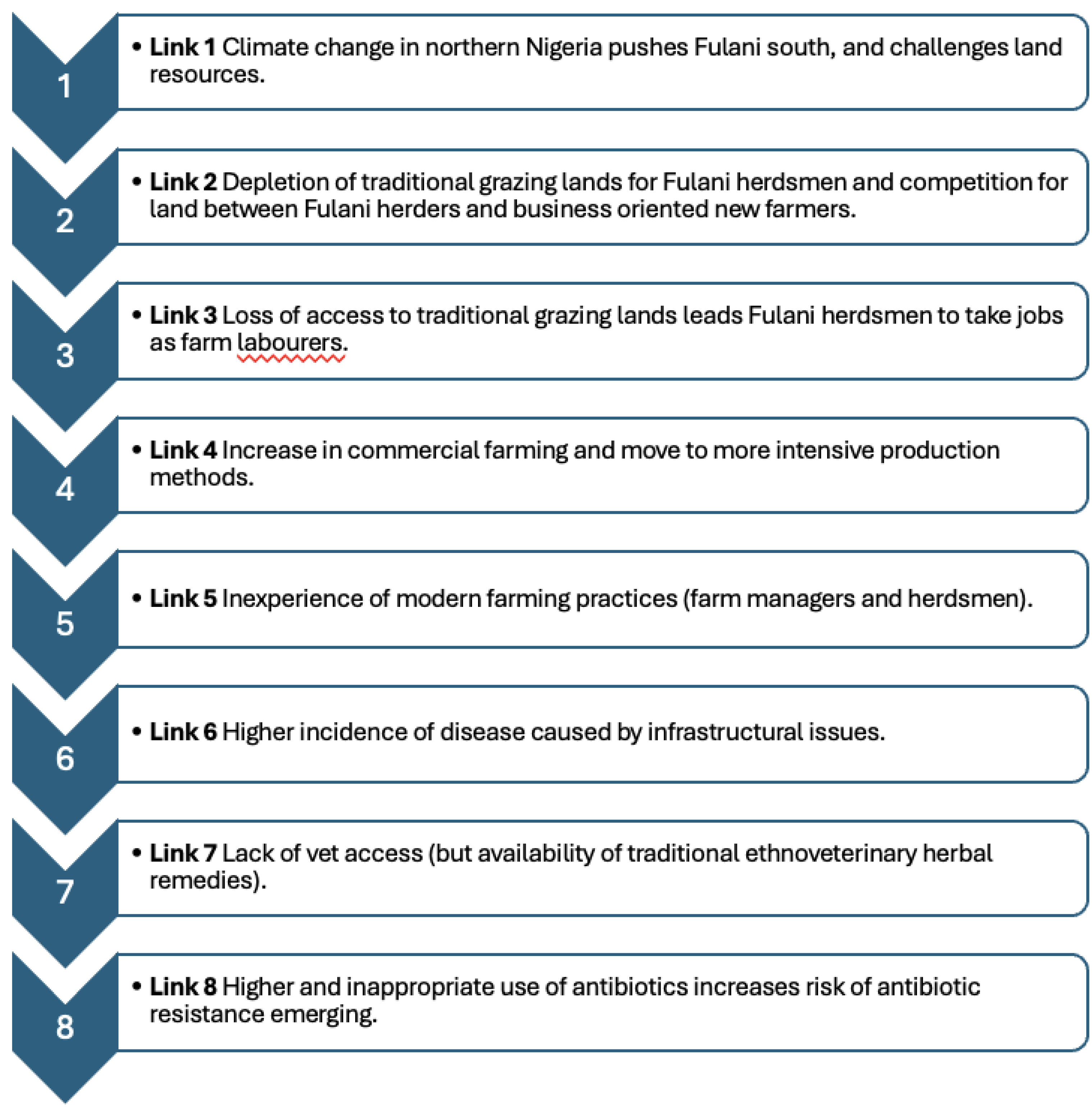

Approached through this framing, the underlying drivers of climate change are positioned at one end of a causal chain that, at the other, threatens the future efficacy of antibiotics and human, as well as animal, health (

Figure 1).

The case study we use to illustrate this framework – cattle management in Nigeria, Sub-Saharan Africa – is being investigated under an International Development Research Centre (IDRC)

1 grant to conduct field trials for the use of Bacteriocin-Rich Extract (BRE) as an alternative to antibiotics for mastitis, a disease of the teat/udder in ruminants (IDRC, n.d). BRE are low-cost, engineered, bacteriocin-producing lactic acid bacteria extracts with high antimicrobial activity. Mastitis is usually caused by bruising/grazing of the udder by sharp grass or bushes, overmilking (particularly in intensive systems), and/or infection of open wounds. Mastitis sometimes resolves on its own, but if untreated it can lead to the affected udder(s) becoming unproductive; cows being unable to feed calves, impacting calf health; abortion in pregnant cows [

15]; and losses to farmer livelihood. As much as 70% of all losses in dairy farming are caused by mastitis [

16]. It is the most economically damaging cattle disease worldwide [

17].

The cattle production system in Nigeria is somewhat unique [

18]. Ninety percent of the >15 million cattle heads in Nigeria are owned by the Fulani, a traditionally nomadic people who have driven cattle across the Sahara, Sahel and West Africa for at least 2,000 years. The Fulani are the largest pastoralist ethnic group in the world; in Nigeria, 15 million people, or 6.6% of the population, are of Fulani descent [

19]. Fulani cattle are primarily kept for beef, though Fulani women milk the cows and make cheese, which is sold commercially. Fulani graze cattle (as well as sheep and goats) on common ground or on land traditionally owned by settled Fulani or Fulani-tolerant farmers. However, a combination of climate change in northern Nigeria, which has pushed Fulani further south [

20], and a rising population across both Fulani and non-Fulani peoples in Nigeria [

21], is constraining land resources and creating rising tensions between farmers and Fulani.

The Fulani are an excluded minority within Nigeria, increasingly seen as problematic (e.g. [

22,

23]) and unwilling to engage with the ‘proper’ authorities; their children receive little formal schooling [

19], marry young and have a high birth rate [

24]. At the same time, Fulani herdsmen are key stakeholders in the expanding Nigerian cattle sector. Beef production in Nigeria increased from approx. 180,000 tonnes per year in 1990 to approx. 330,000 tonnes per year in 2019 [

25], with many Fulani employed by farm owners, who often live away from the farm, to look after the animals in systems that range from fully pastoral to intensive. Of interest to planetary health, and to efforts to combat antimicrobial resistance, is that Fulani indigenous practices include a well-developed herbal medicine tradition [

26] that may offer alternatives to antibiotic use in livestock; however, modernisation and intensification of the cattle sector in Nigeria risks this opportunity being lost.

This paper recognises fully the criticisms that have been levelled at the field of planetary health for not sufficiently considering animals within its holistic view of human and environmental health (e.g. [

27,

28]). It is outside of the scope of this paper to challenge such critique but we also hope to assure those primarily concerned with animal and livestock health that the topic is not outside the remit of the planetary health field. In fact, the lead author was one of the advisory group that drafted the Berlin Principles on One Health [

29] and is a current Senior Editor with CABI One Health [

30]. She thus spans the One and Planetary Health fields and seeks to build bridges between them by helping to highlight how the health of animals, humans, and the environments in which they live cannot be addressed in isolation.

3. Results

Key stakeholders and FGD participants reported 39 cattle diseases/causative agents of disease, many of which had both English and Fulani names including mastitis/koti; Contagious Bovine Pleuropneumonia/Guyna; and Foot and Mouth Disease/Boru. Many antibiotics including amoxicillin, penicillin, streptomycin and Tylosin were named as common treatments. Also prominent in the discussions were ethnoveterinary treatments, with more than 50 named and described, including Yangyang leaf (

scientific name undetermined), which is mixed with water into paste and applied to the udder to treat mastitis caused by tick bites; baheda tree bark (

Terminalia bellirica), mixed with water and given as a drink or applied externally to treat snakebite; and konta (soda soap) for treating wounds. Fulani and non-Fulani farmers reported often using allopathic and ethnoveterinary in combination. Many of the challenges to prudent antibiotic use observed in Nigeria – and examined in the following sections – mirror those seen elsewhere in dairy production [

34,

35], such as ready availability of over-the-counter antibiotics; financial and geographical difficulty in accessing vet services; and challenges in keeping cattle sheds hygienic in low-resource settings. There were also some elements unique to the production system in Nigeria, such as the relationship between Fulani herders and the businessmen farmers who employ them.

In addition to the disease knowledge and management practices, and of equal important to the field of planetary health, the FDGs and key stakeholder interviews suggest that the confluence of changes in the environmental and political climates in Nigeria is challenging distributive justice, a key planetary health ethic [

36]. Disenfranchised Fulani herdsmen are being pushed into intensive practices with which they not only are they unfamiliar, but so too are the business-focused new farm owners who employ them. In such environments, unhygienic sheds and artificial feeds challenge animal health and, combined with poorly-regulated antibiotic use, create optimal conditions for AMR emergence.

Seen through the planetary health framework of underlying drivers leading to human health effects [

5] there is a causal chain leading to antibiotic resistance risk in Kwara State, Nigeria, which is illustrated in

Figure 1 and described in more detail in the sections below.

3.1. Climate Change Impacts in Northern Nigeria

Climate change is an ecological driver in the planetary health causal chain framework proposed by Sam Myers in 2017, [

5] the result of underlying drivers such as over consumption, demographic shifts and technology use. Links in a chain between climate change and AMR are slowly gaining recognition, [

37,

38,

39] though the impact of environmental changes remains under-represented in the AMR literature [

34]. During FGDs and interviews our study’s participants discussed the impact of climate change in Northern Nigeria, where drought and aridity are causing traditional grazing lands to dry up [

40]. Fulani herdsmen are being pushed further south, where there is more fertile land and a milder year-round climate, but climate change is also beginning to affect the south.

“[We] have difficulty sustaining irrigation system to sustain feeding, especially during dry season” – Farmer, FGDs

The increasingly challenging conditions create competition for land between Fulani and new farmer owners who are not of Fulani descent.

It is not only the environmental climate that is influencing the current situation in Nigeria but also the political environment, of which planetary health is mindful when planning solutions [

8,

41]. The Nigerian Government shows little respect for the Fulani pastoral culture and traditional practices [

42]. Programmes in south Nigeria to settle nomadic tribes by giving them land, schools, piped water and other amenities, as well as to designate routes from the north to the south for them, have not been entirely successful [

43]. With little evidence of consultation or co-production with the Fulani, and little regard for their culture or traditions, these political decisions deprive Fulani of land to graze their cattle – resulting in the challenges experienced in the next link we will explore in the causal chain.

3.2. Depletion of Traditional Grazing Lands for Fulani Herdsmen, and Competition for Land between Fulani Herders and Business-Oriented New Farmers

FGD participants expressed beliefs that there is no longer enough available pasture in Nigeria to feed the Fulani’s animals, and that,

“The system has to change” – FGD participant.

The challenges farmers reported in maintaining pasture during the dry season have a particularly detrimental effect on milk production, which in turn affects Fulani income.

“The pot of dairy products coming from traditional practitioners is getting smaller”. – Farmer, FGDs

Some key informants and FGD participants felt that the situation is exacerbated by rapid urbanization and Nigeria’s high birthrate among both Fulani and non-Fulani populations: Nigeria has an average birthrate of 5.1 live births per woman [

21], rising to 8.2 within the Hausa/Fulani [

44], against a world average of 2.3.

FDG participants felt that land shortages are making intensification of livestock rearing – into enclosures and indoor sheds – unavoidable. The contraction of grazing land may be driven as much by business interests that are seeking to emulate intensive North American and European farming practices, often with influence from foreign dairy industry players such as the Dutch-owned Wamco, as an environmental necessity [

45]. Other literature suggests Nigeria is not lacking in abundant, fertile land, but that this is currently under-utilized for agricultural productivity and pasture [

46,

47].

A move from pastoral grazing to intensive livestock rearing has implications for climate change, as well as land use change, as beef is one of the most inefficient forms of protein production for human consumption and a major contributor to greenhouse gases [

48]. Intensive farming systems have higher carbon footprints than extensive systems due to imported feed supplements and fossil fuel use for powering on-farm machinery [

49,

50,

51], creating a feedback loop in which intensification is responsible for climate change, one of its own underlying drivers.

The contraction of grazing areas is eroding traditional Fulani pastoral lifestyles and pushing them to seek livelihoods elsewhere, many in new farms on land being bought up by affluent Nigerians who see farming as a business opportunity rather than a way of life. This leads to the next link in the causal chain, as Fulani move from owning their own means of production to being employees in a capitalist system.

3.3. Loss of Access to Traditional Grazing Lands Leads Fulani Herdsmen to Take Wage Labour on Commercial Farms

The Fulani are currently sandwiched between their pastoral, nomadic herding cultural traditions and a rapidly developing Nigeria whose government seems determined to settle them (Ezemenaka and Ekumoako, 2018). With climate change depleting their traditional grazing lands in the North and an increase in the number of commercial farmers coming into the cattle industry for business purposes, many Fulani take jobs as herdsmen on commercial farms, tending to the herds in fields in exchange for a salary, and for any milk the cattle produce. In many cases this arrangement seems to work well, with businessmen farmers recognising the Fulanis’ greater experience with cattle but there are also clashes. Fulani are used to the freedom to roam across West Africa, grazing more-or-less where they please on open ground, and on farms where more affluent Fulani have settled. This is changing, however, with more and more of the new generation of farmers wanting to keep the Fulani off their land, often for good reason:

“Infection came when some cows graze on where our cattle graze.” – Non-Fulani farmer, FGD

As cattle rearing is increasingly seen as a business opportunity, investors who are not of Fulani heritage do not want the Fulani on their land. Some Local Government Authorities, for example Édé, are demarcating lands to provide settlement points and serve as grazing areas for nomads in a bid to reduce farmer/herder clash, but these programmes seem to have little input from the Fulani themselves.

“Why we still have nomadic animals is because this is an ancient traditional method.” – Fulani farmer, FGD

This means that while the Fulani provide labour on such farms, the farms do not make use of their expertise in a particular kind of cattle production system – low-input, low-output pastoral herding. This threatens to lose important and animal-health-relevant ethnoveterinary knowledge.

3.4. Increase in Commercial Farming and Move to Intensive Production Methods: Challenges and Opportunities

Cattle production systems in Nigeria range from traditional herding of indigenous breeds (in southern Nigeria, Bunaji – White Fulani – are preferred to Bokolo (

Sokoto Gudali), which are less resilient in the dry season), who graze on wild ground or cultivated pasture, to enclosed or shed-raised crossbreeds (indigenous breeds crossed with foreign breeds such as Holstein Friesians) fed on silage and artificial feed [

18]. Many farms contain more than one production system. Even in commercial farms, most indigenous cattle are predominantly kept for beef, as milk yield is too low for commercial production (~ 1l per day per cow, which may be increased to ~3l per day if fed on cultivated pasture and/or silage).

Many of the new generation of farmers are neither of Fulani heritage nor from farming backgrounds: key informants we spoke to came from backgrounds as diverse as civil engineering and public administration, for example. They buy land and set themselves up as farmers as cattle ownership is seen as an indicator of social status and wealth, as well as a means of beef production and income. These businessmen farmers’ relationship with their animals, and the Fulani herders who tend to them, is purely transactional.

“I bought 10 Bororo [Fulani Red Cattle], cost of transport and purchase 103k [naira] and sold for 450-480k after 6 months.” – Farm owner, FGD

One Fulani farmer at the FGDs remarked,

“[The] problem in Nigeria [is that the] majority [are] after profit, we don’t look into major problems affecting the production system.” – Fulani farm owner, FGD

Such farmers often employ Fulani herdsmen to look after herds of 50-250 cattle for them. They experiment with crossbreeding the local Fulani cattle with foreign breeds (mostly Holstein Friesian) to increase milk production, as well as with cultivation of Napier grass and ‘Savia’ (Agrosavia Sanabera, a commercial variety of Guinea grass) for silage. These experiments have mixed success: the exotic breeds are more susceptible to disease, including FMD and foot rot, when they graze on uncultivated land, and they do not tolerate ticks well. They are only likely to survive and be productive if kept indoors all day, with implications for animal welfare, hygiene and resource costs, e.g. of artificial feed, as well as increases in greenhouse gas emissions linked to transportation of imported feed and operation of machinery [

49,

50,

51]. While some farmers in the FGDs spoke of Maizube, an intensive integrated farm in Niger State, Nigeria, they had heard can produce up to 60l of milk per cow per day, 20-30l was the most they were aware had been achieved in Nigeria and most farms produced much less. Foreign breeds are seen as essential to increasing milk production, but high-milk-yield cattle do not prosper in the Nigerian bush.

Many farmers gave examples of poor experiences with modern farming methods:

“There was a machine milking (mechanical dairy farm) at Shonga, but this was discontinued due to climate.” – Farmer, FGD

Farmers, farm owners and the Fulani appreciated that there is market value from commercial milk yields, but if this can only be achieved with supplementary feed, the cost/benefit calculations may bring little economic benefit from more modern methods. Fulani herdsmen mentioned dry cassava peel, maize concentrate, and molasses as supplementary feed, but commercial pellets increase the price of production further and present a risky entry point for premixed antibiotics into the production system [

52]. Combined with food price rises and shortages of food for human consumption in Nigeria, a move away from grazing systems does not offer an attractive business model at present.

A move to more commercial farming brings with it the commercial pharmaceutical industry to maintain herd health. Intensification is a recognised risk factor for antibiotic use, a touchpoint where antibiotics begin to enter the system [

53,

54]. Aligning with evidence from LMICs across the world [

55,

56], the farmers we spoke to described buying drugs directly (over-the-counter) from pharmacies and drug company representatives without a prescription or even consultation. Pharmaceutical drugs are also often added to feed, however the farmers we visited on farms, and who participated in FDGs, displayed little knowledge of (or control over) ready-mixed feed they bought for cattle raised in more intensive systems. This largely unregulated use of antibiotics within the commercial farms raises challenges for prudent antibiotic use when considered in light of the next link in the causal chain.

3.5. Inexperience (Fulani and Farm Owners) of Modern Farming Practices Leads to Use of Antibiotics as ‘Infrastructure’

The non-Fulani farm owners who attended the FGD had been farming for between two months and 15 years; Fulani in contrast come from generations of herders. Fulani are highly experienced in traditional farming methods, however they have less or no experience of intensive farming practices. This can raise some tensions and challenges for animal health management practices in general and for the use of antibiotics in particular.

Farm owners complained that Fulani employees will often push them to cull a sick animal rather than try to treat it. Considering the Fulani’s nomadic heritage, this makes sense as a biosecurity measure – without modern veterinary medicine, culling a sick animal is the best way to ensure that disease does not spread through the herd. A sick cow will slow down a herd on the move and cannot easily be isolated. Fulani traditional knowledge includes ways to spot emerging disease, e.g:

“If milker is milking and the colour of milk is changed it is easily detected and tasted and then is it discarded if this” – Fulani farm owner, FDG

“For mastitis (breast), once there is a problem with milk, you’ll know from the taste, and you prevent the calf from suckling.” – Fulani farm owner, FGD

Fulani employees are quick to push farmers to take cows with mastitis – or which have already lost teats to mastitis – to market and to quickly dispose of cattle suffering from ‘Gunya’ a catch-all term for infectious respiratory disease. Non-Fulani farmers claimed the Fulani had a way to mask mastitis at markets so that it would not affect the cow’s value.

Fulani will often leave a sick animal on its own, isolated from the rest of the herd, but this is less easy when cows are enclosed. They will often move herds if sickness is detected; this may move the herd away from an environmental source of pathogens but also risks spreading disease over the distances travelled if other animals are infected. Farm owners, in contrast, prefer to call a vet and treat the animal with drugs.

In the rural farms, access to a vet was not always straightforward or even possible, however. It may be uneconomical for the vet to visit, or only possible by charging a farm further away more than one that is nearer, a challenge that has been identified previously [

35]. Another factor is cost, which often comes up in dairy cattle literature (e.g. [

57,

58,

59]); some farmers simply cannot afford veterinary charges. The decision to engage a vet, or not, remains a complex cost-benefit analysis for LMIC farmers, based on the lost opportunity costs associated with a sick animal as well as the cost of vet’s fees and the medication he or she prescribes. This affects vaccination, as well as treatment (we observed no vaccine refusal or hesitancy other than due to lack of being able to afford the vaccination).

“We’ll call the vet if they’re near” – Farm manager, FGD.

“If the vet is near, we call them and if they are not near, you’ll go to them to explain to them and then you’ll get the drugs they describe to you to use.” – Fulani farm owner, FGD

Veterinarians also pointed to the lack of a cold chain for vaccines, both in terms of transporting them from veterinary practices to the farms, and storage at either end, exacerbated by frequent power cuts that make maintaining consistent low temperatures challenging, an issue we have highlighted previously in India [

37]. This was also a cause of mistrust of veterinarians and their products, as Fulani and farmers knew that some drugs deteriorated if they could not be kept cold (the cold chain was also an issue for the Nigerian academics, who reported that often as much as 80% of samples they take from fieldwork can be lost due to freezer failure during powercuts):

“Poor drug storage and fake drugs leading to inefficiency (under sunlight for long periods – expired). The sellers don’t disclose this to the farmers buying them.” – Farm owner, FGD

“Most drugs are fake, hence we don’t get results well.” – Fulani farm owner, FGD

In human medicine, antibiotics have become ‘infrastructural’ [

60], used as a quick fix [

61] for more deep-rooted issues such as poor hygiene, overcrowding, and poor nutrition: this is mirrored in livestock. Animal welfare in indoor sheds is poorer than in extensive systems [

62,

63]; this can leave farms, particularly in LMICs, dependent on antibiotics to maintain herd health with the immediate needs of keeping the herd productive outweighing concerns about the externality of the impact of AMR on human health due to the emergence of resistant infections [

64].

There is however, an alternative – and this is not only the BRE we will trial in the next phase of our project – but rather one that looks through a planetary health lens to the possible benefits offered by the ethnoveterinary practices of the Fulani and advocates for reducing the risk of these practices being lost by ensuring they are properly appreciated. This danger of losing traditional knowledge is the next link we will consider.

3.6. Disease Management in Fulani Ethnoveterinary Tradition

Discussions with the key stakeholders and FDG participants indicated that Fulani herdsmen have a wide variety of traditional ethnoveterinary practices and herbal remedies available to identify sickness, manage herd health and treat sick animals.

“We are cattle rearers and we usually use our own local knowledge, for Gunya, we use Guinea corn and local oils and rub on the body.” – Fulani farm owner, FGD

“[To prevent/treat mastitis] the nipple should be massaged before delivery so that dirts can be removed. Pus is not hygienic to calves.” – Fulani farm owner, FGD

Armed with this knowledge, Fulani herdsmen may attempt to treat a sick animal themselves for up to two weeks before reporting the issue and calling in a vet (in later stages of our project, we hope to explore the impact of this on both health outcomes and antibiotic use).

While the field of planetary health seeks to incorporate and make visible the valuable contribution of traditional practices [

12], we must also be careful not to fetishise traditional healers: their knowledge is not perfect [

26] and needs to be seen as complementary to modern veterinary science, not as a replacement for it or in opposition to it. One Fulani farmer who attended the FGD believed that FMD is incurable once the cow is infected, for example, while another did not know that vaccination is available for some diseases. Fulani farmers recognise themselves that herbal remedies do not always work:

“When herbs are used, they work well except for Gunya which is highly tedious to manage due to case of recurrence about a month or two after.” – Fulani farm owner, FGD

This knowledge is clearly valuable, but there is a feeling that it is in danger of being lost:

“It is the elderly ones among the Fulani that knows most of the herbs. The knowledge of the herbs is waning along the lineage. They have the methods of application of these herbs.” – Veterinarian, FGD

One Fulani farmer was happy to admit that they were not always able to detect cases of mastitis early enough, suggesting that they may be open to using point-of-care diagnosis tools. Recognising which diseases herbal remedies work on effectively and on which they do not may open opportunities for discussing better cooperation between vets and traditional healers and identifying points at which treatment needs to be handed over to stronger, but more expensive, allopathic medicine. A traditional Fulani herbal treatment was reported as costing as little as a tenth of the cost of the veterinary alternative (1-2,000 Naira compared to 8-10,000; 1US$ = approx. 1,600 Naira), and most Fulani remedies are homemade, at even less cost, which may be all that local farmers are able to afford.

Some of the veterinarians at the FGDs who saw value in learning more about the traditional Fulani practices claimed such knowledge exchange is hampered by the Fulani being very secretive about their traditional knowledge and generally unwilling to share it with outsiders; one veterinarian said that Fulani would not even use these remedies in the presence of non-Fulani.

“We don’t know the traditional ways and their ways of preventing [mastitis]” – veterinarian, FGD

“I want to implore you that if you have proven effective herbal remedy [for snake bite] don’t hide it, inform the authority so that knowledge can be utilized effectively.” – veterinarian, FGD

The Fulani had similar opinions of vets, who they claimed (and vets confirmed) remove labels from drugs they administer when Fulani herdsmen are watching to prevent the herdsmen from buying the same drugs themselves in the future without a prescription. Fulani spoke of using traditional and allopathic medicine together, rather than seeing one as exclusionary of the other:

“I’ve treated TB with herbs after diagnosis from a vet before.” – Fulani farmer, FGD

There was broad support from veterinarians for scientific research on the Fulani natural remedies to better understand their efficacy, with suggestions that research into this topic should receive Nigerian Government investment – as existing literature has also highlighted [

65]. Kenyan traditional medicinal plants are starting to gain more academic attention [

66].

3.7. Use of Antibiotics to Manage Disease

Awareness of antibiotics, antibiotic resistance and its causes was reasonably high amongst participants. FGD participants named several antibiotics that were regularly used in animal health (including Amoxicillin, Enrofloxacin, Penicillin, Streptomycin, Tylosin). They knew that drugs for human use should not be used for animals or vice versa and that overuse of antibiotics leads to resistance. It was generally agreed that in Nigeria anyone can buy antibiotics over-the-counter from a pharmacy without a prescription, and antibiotics (such as ‘PenStrep’ – Penicillin and Streptomycin) – were considered to be probiotics, used to improve general health. Farmers and herders will often note what the veterinarian uses, and the next time the animal is ill, they will buy that drug again directly from the pharmacy.

Little testing is done to determine the causative agent of the disease or which drugs it may be susceptible to, largely due to lack of ability to afford such testing and paucity of laboratories – none of the veterinarians we engaged had testing facilities at their surgeries. It was thought that some of the commercial dairy farms may be able to afford this, but we did not come across any directly.

“Who can afford it [testing]? One who cannot afford treatment can’t afford the testing (AST).” – Farm owner, FDG

“Animals are owned on average by poor people.” – Veterinarian, FDG

One FGD participant suggested that key private sector players in the EU, where antibiotic use in livestock has reduced significantly in recent years, could be engaged to promote prudent ABU in LMICs, giving examples and sharing best practice of how the reduction has been achieved.

Whilst the farm owners and managers expressed a preference for using veterinarians as soon as illness was detected, the Fulani preferred to try traditional practices first and go to the vet only if these practices failed. There has been little research into the risks associated with this practice – i.e. whether delayed treatment does in fact lead to poorer health outcomes in the sick animals, or if it has an impact on the emergence of antibiotic resistance. Existing papers [

67,

68] are increasingly pointing to the value of ethnoveterinary practices for treating low-level ill-health, and Fulani farmers reported that their treatments are often effective. Many non-Fulani farmers respected and had faith in the traditional remedies and one farmer had set up an area within his farm where the herbs could be grown, which he jokingly called his ‘lab’. It may well be the case that there is space for traditional remedies and allopathic veterinary practices to exist along a continuum and to lie side-by-side for much of it: it may be effective for initial treatment to be carried out using traditional remedies, and veterinary doctors to step in only when these treatments fail. It is the intermediary step, of using over-the-counter allopathic veterinary medicines without prescription that raises problems, including sub-dosing, not following the complete regimen, and using the wrong drug for the infection.

Several of the participants recognised that there would be value in conducting more extensive scientific research into the Fulani traditional remedies and their efficacy, both for the purpose of better integrating the ethnoveterinary and allopathic practices, and for creating improved treatments using the active ingredients of traditional remedies. More scientific understanding of, for example, appropriate doses, combinations of ingredients, specific qualities such as anti-inflammatory actions, or conditions for use would be valuable to capture. This is something our team hopes to focus on in future stages of our research and future funding.

3.8. The End of the Causal Chain

The stages noted above lead to the end point of the causal chain – the risk of human health being compromised by loss of antibiotic efficacy.

3.9. Further Issues of Note

Common tropes of farmers, and herdsmen, being uneducated, ignorant and unwilling to change were rampant. Typical comments recorded during the research included:

“The vets should educate the farmers” – veterinary practitioner, key informant

“The problem is that they are uneducated, they need to be trained” – farm manager, FGD.

“They do not have the knowledge of these things [hygiene, especially in cow sheds], especially in [their] dialect” – farm manager, FGD.

“They are not careful enough.” – farm manager, FGD.

Unfortunately, this is an attitude often mirrored in academic literature on the Fulani (e.g. [

69]). Other accusatory comments such as

“They don’t like to mix with people”, suggested that some participants did not even consider the Fulani to be ‘normal’ people.

Elite FGD participants made suggestions that the Fulani “should be encouraged to have Android phones”, with little regard for the lack of wifi or data coverage in rural fields. Many Fulani do use phones, for example as one Fulani farmer described,

“We make concoction to treat diseases immediately we notice and local herbs – by calling our father,” – Fulani farmer, FGD

However, they were criticised for using these phones to connect with their own networks and radio stations broadcasting programmes in their own dialect, rather than these channels being considered as ways of disseminating information to Fulani.

The Fulani farmers were willing to consider different approaches – but wanted proof that if things are done a different way, results will be better.

Facilitator, FGD: “If the BRE is proven effective would farmers be prepared to use them, despite all the local remedies and alternatives available?”

Farmer, FGD: “You’ve not introduced the drug yet, so we can’t know.”

Facilitator: “After trials, it would be introduced with results.”

Farmer, FGD: “As long as it is effective and cost effective.”

“Farmers like to give a new product a trial especially if it is relatively cheaper than existing similar products.” – Drug seller, FGD

The more business-oriented approach to farming could be beneficial to changing farmers’ practices away from antibiotics towards alternatives such as BRE that do not threaten human health, by proving the economic benefit of the alternatives.

“We need to explain to them [the farmers] how these projects directly affect their income and how it can be of benefit to them and not only for AMR.” – veterinarian, FGD

There were also suggestions that training on sanitation and housing in modern farming practices, as well as animal nutrition and farm finance, for both farm owners and Fulani workers would be beneficial; this is more practical than training in ‘antibiotic resistance’ which may be outside of the farmers’ powers to address [

34], and needs to be tackled at a more systematic level through tighter government regulation that ensures veterinary prescription only. Better water, sanitation and hygiene conditions for cattle, combined with good, natural nutrition and plenty of access to outdoor space, will have a strong positive influence on animal health, and is likely to reduce the need for antibiotics to clean up problems caused by poorer welfare conditions.

It was not clear from the FGDs that farmers or Fulani are indeed ‘uneducated’ and ‘ignorant’; while they may not have undertaken a veterinary medicine degree, the discussions indicated they understood complex issues, such as the microbiome and its role in immune response, and often referred to pathogens by their scientific names. ‘Educating’ them further but leaving them with no easier access to affordable veterinary services, water and sanitation infrastructure or practical training in modern herd management practices is unlikely to change the current situation significantly.

4. Discussion

Several potential solutions arose from the discussions that may provide a way forward for Nigerian cattle production that maximises the health of humans, animals and the environment, and which respects the indigenous knowledge of the Fulani herders, so that the use of antibiotics within the sector can be minimized and optimized.

First, spaces for Fulani practice that enable them to maintain their nomadic way of life and graze cattle on open ground, at which they are skilled and experienced, is necessary. The benefits to humans, animals and the environment from grass-fed rather than intensive dairy and beef production systems has long been recognised [

70,

71,

72,

73]. Settlements provided for Fulani seem to be focussed on encouraging them to stay in one place, and to intensify cattle production for the benefit of external actors, rather than allocating land along migratory routes that enable Fulani pastoralists and their herds to move around, grazing and stopping where this fits with their lifestyle.

Second, more research is needed on Fulani practices and ethnoveterinary knowledge, to ensure indigenous knowledge is preserved, and to determine how these fit best with, and can complement, modern veterinary science. This should include research on active ingredients, dosing regimes and outcomes of delaying allopathic treatment.

Third, more research is needed into impact of climate change on animal health and antibiotic use in dairy cattle in Nigeria (and globally) including thresholds at which ill-health is triggered, low-resource mitigations – such as grazing cattle amongst trees, which we witnessed on several farms – and likely challenges to pasture and grazing crops in future under different climate change predictions.

Finally, communication needs to be better facilitated between Fulani healers and veterinarians to share knowledge in both directions; animal health knowledge can be shared over Fulani radio stations and through their traditional communication channels, but this needs to respect their culture and practices and acknowledge the challenges they face, with awareness that they are largely operating in open countryside without running water, electricity or access to (affordable) veterinary services. In turn, Fulani can share their ethnoveterinary practices with the livestock sector to determine how they can be better integrated into animal health regimes.