1. Introduction

Currently, entrepreneurship has become a fundamental driver for sustainable economic development, continuous innovation, and the creation of quality employment (Agu et al., 2021; Méndez-Picazo et al., 2021). In the university environment, fostering an entrepreneurial spirit among students not only promotes the creation of new businesses but also strengthens key competencies such as solving complex problems, effective leadership, and strategic decision-making in dynamic environments (Davey et al., 2016; Lyu et al., 2024).

Entrepreneurship not only drives economic growth but also has a significant social impact on communities. (Backes et al., 2022; Ciruela-Lorenzo et al., 2020). In Peru, where poverty and unemployment rates are high, fostering an entrepreneurial culture among young people can improve quality of life and create jobs, both for the entrepreneurs and their communities (Alva, 2017; Diez, David et al., 2023).

Social enterprises, focused on solving social and environmental problems, also tackle critical challenges such as education, health, and sustainability (Aboobaker & Renjini, 2020; Méndez-Picazo et al., 2021). Therefore, it is essential to integrate entrepreneurial education into universities, not only to prepare students for the job market but also to empower them to make positive contributions to society (Calanchez Urribarri et al., 2022; Fariña Sánchez & Suárez Ortega, 2023).

The growing body of evidence highlights the significant social impact of entrepreneurship (Acheampong & Tweneboah-Koduah, 2018; Kaur & Chawla, 2023). Cultivating an entrepreneurial mindset in students enables them to become agents of change in their communities, which is crucial in a country like Peru, marked by social and economic inequalities (Alva, 2017). Promoting an entrepreneurial culture in universities not only helps students develop practical skills but also inspires them to tackle social problems, create innovative solutions, and contribute to the overall well-being of society (Calanchez Urribarri et al., 2022; Talukder et al., 2024). It is essential for universities to implement programs that not only teach entrepreneurial skills but also foster a sense of social and community responsibility among future entrepreneurs(Aboobaker & Renjini, 2020; Gofman & Jin, 2024).

Universities, therefore, are no longer merely academic training centers; they have evolved into genuine incubators of innovative ideas and entrepreneurial projects capable of transforming entire sectors of the economy (Uddin et al., 2022; Yung et al., 2023). Building and strengthening an entrepreneurial culture in higher education institutions is recognized as a crucial factor in ensuring the long-term success and sustainability of future professionals and entrepreneurs (Isensee et al., 2020; Martínez-Martínez, 2022). This culture does not emerge by chance; it is the result of an intentional academic environment that fosters creativity, stimulates innovation, and provides the necessary tools, knowledge, and support for students to turn their ideas into viable and impactful business projects (Shi et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2023).

In the Peruvian context, university entrepreneurship has emerged as a strategic response to the economic and social challenges the country faces (Bullón-Solís et al., 2023; Cenzano & González, 2021). Despite its undeniable potential, the rate of formal entrepreneurship among young Peruvians remains low compared to other countries in the region, highlighting the urgent need to strengthen the entrepreneurial culture within higher education institutions (Aceituno-Aceituno et al., 2018; Chávez Vera et al., 2023).

In this regard, universities in Peru, in their fundamental role as catalysts for development, face the challenge of creating an ecosystem that not only motivates students to undertake entrepreneurial ventures but also provides them with the tools and competencies needed to overcome the inherent barriers of the local business environment, such as limited availability of financial resources, excessive bureaucracy, and the lack of robust institutional support (Vásquez-Pauca et al., 2022; Zapata et al., 2024). Encouraging entrepreneurship among Peruvian university students is essential not only for the creation of new businesses but also for catalyzing a profound transformation in the economy and society, driving a new generation of leaders capable of innovating and generating sustainable, long-lasting change (Calanchez Urribarri et al., 2022; Davila-Moran, 2022).

Despite the growing relevance of entrepreneurship in Peruvian universities, there is still a considerable gap in academic literature concerning the factors that determine the entrepreneurial culture in these institutions (Al-Jubari, 2019; Boscán Carroz et al., 2023). While some studies have explored youth entrepreneurship broadly, few have delved into how specific variables, such as attitude toward innovation and creativity, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and institutional support, influence the creation and consolidation of an entrepreneurial culture in the university context (Aboobaker & Renjini, 2020; Tessema Gerba, 2012). This gap is particularly significant in Peru, where fostering an entrepreneurial culture among university students is crucial to addressing the country’s economic and social challenges.

In response to this need, the present study seeks to fill this gap in the literature by providing a comprehensive analysis of the key factors that promote the creation of an entrepreneurial culture in Peruvian universities. Previous studies have applied the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) to analyze entrepreneurship in educational contexts, demonstrating its usefulness in understanding how attitudes, social norms, and self-efficacy influence entrepreneurial culture (Aliedan et al., 2022; Sampene et al., 2023). This study builds on these precedents to offer evidence-based recommendations that higher education institutions can adopt to strengthen their role in the national entrepreneurial ecosystem.

To understand the factors that influence the formation and consolidation of an entrepreneurial culture in the university setting, it is essential to rely on robust theoretical frameworks that allow for the precise and systematic analysis of interactions between key variables. In this context, Ajzen’s TPB (Theory of Planned Behavior) stands out as a powerful conceptual framework for unraveling the dynamics underlying the entrepreneurial process (Ajzen, 1991; Wijayati et al., 2021). The TPB posits that the intention to perform a behavior, such as entrepreneurship, is determined by three central components: attitude toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (Acheampong & Tweneboah-Koduah, 2018; Ajzen, 1991; Henley et al., 2017).

En el ámbito del emprendimiento universitario, la actitud de los estudiantes hacia la innovación y la creatividad, su percepción del apoyo social e institucional, y su autoeficacia (la confianza en su capacidad para emprender) son factores clave que determinan su intención emprendedora (Al-Jayyousi et al., 2019; Henley et al., 2017).

A positive attitude toward innovation and creativity can strengthen entrepreneurial intention, while a strong sense of self-efficacy can increase the perception of control over entrepreneurial behavior. This intention not only drives entrepreneurial action but also contributes to the creation and strengthening of an entrepreneurial culture within higher education institutions (Ceresia & Mendola, 2020; Yung et al., 2023). Additionally, the TPB allows for the exploration of how the perception of barriers and institutional support can mediate or moderate these relationships, offering a detailed framework to understand the complexity of the entrepreneurial phenomenon in the university context (Ajzen, 2020; Diez, David et al., 2023).

The present study focuses on examining how key variables identified by the TPB, such as attitude toward innovation and creativity, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and institutional support, influence the entrepreneurial culture within the Peruvian university context. It is proposed that these variables not only have a direct impact on entrepreneurial intention but also interact with each other to shape an ecosystem that can either strengthen or weaken the entrepreneurial culture (Barrales Martínez & Rodríguez Gutiérrez, 2023; Gimenez-Jimenez et al., 2022).

In this regard, it is anticipated that high entrepreneurial self-efficacy will foster a positive attitude toward innovation, which in turn increases the intention to undertake entrepreneurship and, consequently, strengthens the entrepreneurial culture (Eniola, 2020; Shi et al., 2019). Similarly, institutional support is considered a fundamental element that can moderate the relationship between entrepreneurial intention and the consolidation of a strong entrepreneurial culture (Alwakid et al., 2021; Prada-Villamizar & Sánchez-Peinado, 2021). This approach allows for a thorough analysis of the internal dynamics shaping the entrepreneurial climate in Peruvian universities, providing a deeper understanding of the mechanisms that can be implemented to foster a supportive entrepreneurial environment (Chávez Vera et al., 2023; Vásquez-Pauca et al., 2022).

This study aims to make a significant contribution to the existing knowledge on university entrepreneurship in the Peruvian context. Through the application of the TPB, it seeks to analyze how attitude toward innovation and creativity, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and institutional support influence entrepreneurial culture. In this regard, the following research questions are addressed: RQ1. How do attitude toward innovation and creativity, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and institutional support influence the formation of an entrepreneurial culture among university students? and RQ2. What role do entrepreneurial intention, external resources, and institutional support play as mediators in the relationship between attitude toward innovation and creativity, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial culture? This approach is expected to provide a deeper understanding of the factors that determine entrepreneurial intention and its impact on entrepreneurial culture within the university environment.

The results of this study will not only enrich the academic literature but also offer valuable practical implications for higher education institutions, helping them design more effective strategies to foster a dynamic and sustainable entrepreneurial environment (Agu et al., 2021; Martínez-Martínez, 2022). Furthermore, it is anticipated that the findings may serve as a foundation for future research and for the development of policies that promote entrepreneurship as a key driver of economic and social development in Peru.

The article is organized as follows:

Section 1 presents the literature review, the proposed hypotheses, and the conceptual model of the study.

Section 2 details the sample, the methods used, and the data collection process. The results are presented in

Section 3. In

Section 4, the findings are discussed, and finally,

Section 5 addresses the study’s limitations, potential directions for future research, and the theoretical and practical implications for university entrepreneurship management.

2. Literature Review, Hypothesis Development, and Conceptual Framework

2.1. Theoretical Foundations of Entrepreneurial Culture in the University Setting: Application of the TPB

Entrepreneurial culture in the university setting has garnered increasing interest in academic literature due to its essential role in promoting entrepreneurship among students (Beugelsdijk, 2007; Vicentin et al., 2024). This culture encompasses a set of values, attitudes, and behaviors that drive the creation and development of new ventures within higher education institutions (Donaldson, 2021; Krueger et al., 2013). Understanding the factors that contribute to the formation of an entrepreneurial culture is crucial for designing effective strategies that foster innovation and entrepreneurship among university students (Alawamleh et al., 2023; Kaur & Chawla, 2023).

To build a solid theoretical framework supporting the analysis of entrepreneurial culture in university students, it is essential to review and analyze Ajzen’s (1991) Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). This theory has become one of the most robust and widely used frameworks for explaining the relationship between individual attitudes and intentional behaviors (Ajzen, 2020; Henley et al., 2017). According to the TPB, human behavior is guided by three key components: attitude toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (Ajzen, 1991). These elements directly influence a person’s intention to engage in a specific behavior, which in turn determines the likelihood of that behavior being performed (Ajzen, 2002; Henley et al., 2017).

In the context of university entrepreneurship, the TPB has been essential for understanding how students’ attitudes toward innovation and entrepreneurship, perceived social pressures, and their sense of control over the entrepreneurial process affect their intention to start a business (Armitage & Conner, 2001; Henley et al., 2017). Previous studies have shown that the TPB is an effective framework for studying entrepreneurial culture, a crucial precursor to fostering entrepreneurship within universities (Aliedan et al., 2022; Sampene et al., 2023).

Within this framework, attitude toward innovation and creativity represents the extent to which students perceive entrepreneurship as positive and desirable (Ceresia & Mendola, 2020; Yung et al., 2023). Subjective norms reflect the influence of the expectations of significant people in the student’s life, such as family members, friends, and academic mentors, on their decision to pursue entrepreneurship (Ajzen, 2002; Henley et al., 2017). Lastly, perceived behavioral control refers to students’ perception of their ability to overcome challenges and barriers on the path to creating their own business (Acheampong & Tweneboah-Koduah, 2018).

The application of the TPB in the university setting allows not only for an understanding of entrepreneurial intention but also how this intention translates into concrete actions that foster an entrepreneurial culture (Ajzen, 2020; Cahigas et al., 2022). This is especially relevant in the Peruvian context, where promoting entrepreneurship among young people is crucial for economic and social development (Aceituno-Aceituno et al., 2018; Chávez Vera et al., 2023). Therefore, this study is based on the TPB to explore and model the relationships between the key variables that influence entrepreneurial culture among university students.

Additionally, factors such as entrepreneurial self-efficacy, institutional support, and the perception of entrepreneurial barriers have been identified in the literature as key determinants (Aboobaker & Renjini, 2020; Tessema Gerba, 2012). This study aims to explore how these elements interact to shape a strong entrepreneurial culture in the Peruvian university context, and from this analysis, formulate the hypotheses that will guide the empirical research.

In the following sections, we will delve into how the existing literature has addressed these factors, providing the theoretical foundation necessary for the development of the hypotheses and the conceptual model of the research.

2.2. Impact of Attitude Toward Innovation and Creativity on Entrepreneurial Culture, Entrepreneurial Intention, Resources, and Perception of Barriers

Attitude toward innovation and creativity is an essential component in the analysis of entrepreneurial behavior, especially in the university context (Al-Jayyousi et al., 2019; Henley et al., 2017). This attitude refers to students’ predisposition to adopt new ideas, experiment with original approaches, and seek innovative solutions (Abdu & Jibir, 2018; Kreiterling, 2023). The relevance of this attitude lies in its ability to influence a variety of interrelated factors that are critical for entrepreneurial success, including entrepreneurial culture, the intention to start a business, access to resources and external support, and the perception of entrepreneurial barriers (Prada-Villamizar & Sánchez-Peinado, 2021; Vamvaka et al., 2020). Below, we elaborate on how this attitude impacts each of these aspects.

Entrepreneurial culture within universities is defined as an environment that fosters the creation and development of new businesses, based on a shared set of values, attitudes, and behaviors that support entrepreneurship (Donaldson, 2021; Mukhtar et al., 2021) Attitude toward innovation and creativity plays a crucial role in shaping this culture (Calanchez Urribarri et al., 2022; Talukder et al., 2024). Students who value and promote innovation tend to actively contribute to creating an environment where new ideas are welcomed, and experimentation is encouraged (Al-Jayyousi et al., 2019; Diez, David et al., 2023). This, in turn, strengthens the entrepreneurial culture by facilitating an ecosystem where entrepreneurship is nurtured and promoted in a sustained manner (Lyu et al., 2024; Uddin et al., 2022).

The literature has demonstrated that an environment that values innovation and creativity tends to develop a stronger and more dynamic entrepreneurial culture (Audretsch & Belitski, 2021; Cai et al., 2019). Studies have found that institutions that integrate innovation into their academic and extracurricular programs are more effective in creating a solid entrepreneurial culture (Bullón-Solís et al., 2023; Chávez Vera et al., 2023). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Attitude toward Innovation and Creativity has a positive effect on Entrepreneurial Culture.

Entrepreneurial intention refers to an individual’s conscious and planned commitment to start a new venture (Al-Jayyousi et al., 2019). This intention is a key precursor of entrepreneurial behavior and is significantly influenced by the attitude toward innovation and creativity (Coduras et al., 2008; Henley et al., 2017). Students who perceive entrepreneurship as an opportunity to apply innovative ideas are more likely to develop a strong entrepreneurial intention (Collins et al., 2004; Kallas, 2019). This is because innovation and creativity not only make entrepreneurship more appealing but also present it as a viable path for personal and professional fulfillment (Alawamleh et al., 2023; Prada-Villamizar & Sánchez-Peinado, 2021).

Ajzen’s (1991) Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) suggests that attitude toward a specific behavior, such as entrepreneurship, is a key predictor of the intention to perform that behavior. In the context of university entrepreneurship, this theory has been validated in multiple studies showing how a positive attitude toward innovation and creativity can significantly drive entrepreneurial intention (Acheampong & Tweneboah-Koduah, 2018; Ajzen, 2020). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: Attitude toward Innovation and Creativity has a positive effect on Entrepreneurial Intention.

Access to external resources and institutional support are key factors in the success of any entrepreneurial initiative (Solano Acosta et al., 2018; Vásquez-Pauca et al., 2022). Attitude toward innovation and creativity directly influences students’ ability to access these resources (Beugelsdijk, 2007; Kreiterling, 2023). Students with a strong orientation toward innovation are generally more proactive in seeking opportunities that allow them to access funding, mentorship, and essential entrepreneurial networks (Bernal Suárez et al., 2021; Wang & Fu, 2023). This attitude not only enables them to better identify opportunities but also facilitates the creation of strategic partnerships that can provide the necessary support to turn ideas into successful businesses (Bu et al., 2023; Suryono et al., 2023).

The literature has shown that entrepreneurs with an innovative attitude tend to establish more effective relationships with external entities, including investors, financial institutions, and other key actors in the entrepreneurial ecosystem (Calanchez Urribarri et al., 2022; Ceresia & Mendola, 2020). This ability to access external resources and support is crucial for overcoming initial barriers and sustaining business growth (Bernal Suárez et al., 2021; Suryono et al., 2023). Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: Attitude toward Innovation and Creativity has a positive effect on External Resources and Support.

The perception of entrepreneurial barriers refers to how students identify and assess potential obstacles on their path to entrepreneurship (Borsi & Dőry, 2020; Ferreras-Méndez et al., 2021). These barriers can include financial, legal, market, or even personal challenges (Berman et al., 2022; Davila-Moran, 2022). Attitude toward innovation and creativity can significantly alter this perception (Buli & Yesuf, 2015; Lago et al., 2023). Students with a positive disposition toward innovation often view barriers not as insurmountable obstacles but as opportunities to apply creative solutions (Audretsch & Belitski, 2021; Liu et al., 2019). This mindset allows them to face challenges with greater resilience and adaptability, reducing the perception of risk and increasing their confidence in overcoming obstacles (Vicentin et al., 2024; Wilde & Hermans, 2021).

Studies have shown that a positive attitude toward innovation is associated with a lower perception of barriers, as innovative individuals tend to be more optimistic and view problems as challenges that can be overcome through creativity and innovation (Acheampong & Tweneboah-Koduah, 2018; Yung et al., 2023). This reduction in the perception of barriers is key to fostering persistence in entrepreneurship (Aceituno-Aceituno et al., 2018; Yeh et al., 2021). Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: Attitude toward Innovation and Creativity has a positive effect on the Perception of Entrepreneurial Barriers.

2.3. Impact of Entrepreneurial Intention on Culture, Resources, and Institutional Support

Entrepreneurial Intention is a key driver that motivates students to turn their innovative ideas into real projects, playing a crucial role in the university entrepreneurial ecosystem (Buli & Yesuf, 2015; Dheer & Castrogiovanni, 2023). This concept not only reflects the desire to start a business but also the willingness to take concrete actions to realize those aspirations (Hassan et al., 2020; Van Auken et al., 2006). In this context, Entrepreneurial Intention influences fundamental aspects of the entrepreneurial environment, such as entrepreneurial culture, access to external resources, and institutional support (Alferaih, 2022; Krueger et al., 2013).

The willingness or intention to engage in entrepreneurship directly impacts the formation and strengthening of Entrepreneurial Culture in universities (Anjum et al., 2021; Gallegos et al., 2024). Students with a strong inclination toward entrepreneurship often become active promoters of entrepreneurial practices and values within their academic environment (Alferaih, 2022; Krueger et al., 2013). This commitment not only inspires other students and faculty members to adopt an entrepreneurial mindset but also creates an atmosphere that values innovation, risk-taking, and creativity (Bataineh et al., 2023; Sarooghi et al., 2015). Moreover, a strong entrepreneurial intention can catalyze the creation of programs and activities that reinforce entrepreneurial culture, such as hackathons, incubators, and entrepreneurship networks (Agu et al., 2021; Buli & Yesuf, 2015). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5: Entrepreneurial Intention has a positive effect on Entrepreneurial Culture.

Students’ ability to access external resources and support is closely related to their entrepreneurial intention (Beugelsdijk, 2007; Ebabu Engidaw, 2021). Students with a strong intention to start a business are often more proactive in seeking opportunities to obtain funding, mentorship, and networks, all of which are critical elements for the success of their projects (Jena, 2020; Van Auken et al., 2006). This proactivity not only improves their chances of accessing the necessary resources but also facilitates the building of strategic alliances with key players in the entrepreneurial ecosystem, which can be crucial in overcoming initial barriers and ensuring sustained business growth (Nguyen et al., 2019; Wang & Fu, 2023). Thus, the following hypothesis is suggested:

H6: Entrepreneurial Intention has a positive effect on External Resources and Support.

Institutional Support is another key factor influenced by students’ Entrepreneurial Intention (Bradley et al., 2021; Yin & Wu, 2023). Educational institutions that recognize this entrepreneurial inclination tend to offer greater support through specific programs, infrastructure, and resources that facilitate entrepreneurship (Bataineh et al., 2023; Zaleskiewicz et al., 2020). This support may include access to incubators, legal and financial advisory services, and training programs in entrepreneurial skills (Berman et al., 2022; Hassan et al., 2020). The relationship between Entrepreneurial Intention and Institutional Support is bidirectional: while students with a strong intention to start a business seek and take advantage of the available support, this same support reinforces their intention by providing them with the necessary tools to achieve success (Brigas et al., 2023; Yi et al., 2024). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H7: Entrepreneurial Intention has a positive effect on Institutional Support.

2.4. Influence of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy on Innovation, Culture, and Entrepreneurial Vocation

Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy refers to an individual’s confidence in their ability to successfully carry out entrepreneurial activities (Dullas, 2018; Eniola, 2020). This concept is crucial in the development of entrepreneurship, as it directly influences motivation, persistence, and the willingness to face the challenges associated with creating and managing new businesses (Carsrud & Brännback, 2011; Fauziah et al., 2023). Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy not only affects students’ attitudes toward innovation and creativity but also significantly impacts the entrepreneurial culture within universities and the entrepreneurial vocation of students (Danish et al., 2019; Yi et al., 2024).

Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy directly influences how students perceive and engage with innovation and creativity (Andrews et al., 2021; Eniola, 2020). Those who are confident in their entrepreneurial abilities are more likely to explore new ideas and seek creative solutions to problems (Jiménez et al., 2015; Wathanakom et al., 2020). This self-confidence fosters a positive attitude toward innovation, encouraging students to take calculated risks and adopt novel approaches in their entrepreneurial projects (Tafadzwa Maziriri et al., 2019; Zaleskiewicz et al., 2020). The relationship between Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and attitude toward innovation is essential for the development of a dynamic and adaptable entrepreneurial environment (Andrews et al., 2021; Gallegos et al., 2024). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H8: Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy has a positive effect on Attitude toward Innovation and Creativity.

Confidence in one’s own entrepreneurial abilities also impacts the formation and strengthening of Entrepreneurial Culture within universities. Students with high Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy often become leaders in promoting entrepreneurial values and practices in their academic environment (Bardales-Cárdenas et al., 2024; Eniola, 2020). This confidence not only drives their active participation in entrepreneurship-related activities but also inspires others to follow their example, contributing to a culture that values innovation and risk-taking (Andrews et al., 2021; António Porfírio et al., 2023). In this way, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy acts as a key driver in the development and consolidation of a strong entrepreneurial culture (Atmono et al., 2023; Yeh et al., 2021). Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H9: Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy has a positive effect on Entrepreneurial Culture.

Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy is closely linked to Entrepreneurial Intention, as confidence in one’s entrepreneurial abilities is a crucial determinant in the decision to start a business (Barrientos-Báez et al., 2022; Ghouse et al., 2024). Students with high Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy are more likely to develop a strong entrepreneurial vocation, as they believe in their ability to overcome obstacles and succeed in the business world (Neneh, 2022; Zaidan et al., 2024). This relationship is fundamental to understanding how entrepreneurial intention is formed and what factors can enhance or limit this process (Wathanakom et al., 2020; Yeh et al., 2021). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H10: Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy has a positive effect on Entrepreneurial Vocation.

2.5. Mediation and Moderation Hypotheses in the Relationships between Self-Efficacy, Innovation, Intention, Resources, and Entrepreneurial Culture

Mediation and moderation hypotheses are fundamental for understanding how different variables interact in the development of entrepreneurial culture (Sarstedt et al., 2019). These hypotheses help identify the mechanisms through which one variable affects another and the conditions that can modify these relationships (Hair & Alamer, 2022). In the context of university entrepreneurship, mediation and moderation reveal how factors such as self-efficacy, attitude toward innovation, entrepreneurial intention, and external and institutional resources contribute to the creation of a favorable environment for entrepreneurship (Aboobaker & Renjini, 2020; Tessema Gerba, 2012). Understanding these complex interactions is essential for designing effective interventions that strengthen entrepreneurial culture within educational institutions (Danish et al., 2019; Mukhtar et al., 2021).

Attitude toward Innovation and Creativity can act as a mediator in the relationship between Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Entrepreneurial Culture (Audretsch & Belitski, 2021; Wilde & Hermans, 2021). This means that students’ confidence in their entrepreneurial abilities can influence their disposition toward innovation, which in turn impacts the entrepreneurial culture within the university (Beugelsdijk, 2007; Vicentin et al., 2024). Students with high self-efficacy are more likely to adopt a positive attitude toward innovation, which drives them to promote and strengthen the entrepreneurial culture in their academic environment (Bataineh et al., 2023; Gallegos et al., 2024). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H11: Attitude toward Innovation and Creativity will mediate the relationship between Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Entrepreneurial Culture.

Entrepreneurial Intention can act as a mediator in the relationship between Attitude toward Innovation and Creativity and Entrepreneurial Culture (Deza-Loyaga et al., 2021; Vamvaka et al., 2020). In this case, a positive attitude toward innovation could lead students to develop a strong intention to start a business, which subsequently contributes to the building of an entrepreneurial culture within the university (Bullón-Solís et al., 2023; Jena, 2020). This mediation suggests that entrepreneurial intention is a key factor that connects innovative attitudes with the promotion of a strong entrepreneurial culture (Anjum et al., 2021; Hassan et al., 2020). Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H12: Entrepreneurial Intention will mediate the relationship between Attitude toward Innovation and Creativity and Entrepreneurial Culture.

External Resources and Support can mediate the relationship between Entrepreneurial Intention and Entrepreneurial Culture (Nguyen et al., 2019; Solano Acosta et al., 2018). This implies that students’ intention to start a business drives their search for and utilization of external resources and support, which in turn strengthens the entrepreneurial culture within the university (Chávez Vera et al., 2023; Vásquez-Pauca et al., 2022). Students with a strong entrepreneurial vocation are more likely to identify and take advantage of available resources, which significantly contributes to the development of an environment that fosters and supports entrepreneurship (Berman et al., 2022; Wilde & Hermans, 2021). Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H13: External Resources and Support will mediate the relationship between Entrepreneurial Intention and Entrepreneurial Culture.

Institutional Support can act as a mediator in the relationship between Entrepreneurial Intention and Entrepreneurial Culture (Atmono et al., 2023; Vásquez-Pauca et al., 2022). In this case, the intention to start a business motivates students to seek and take advantage of institutional support, which ultimately reinforces the entrepreneurial culture within the academic environment (Carsrud & Brännback, 2011; Zapata et al., 2024). Institutional support, which includes incubation programs, advisory services, and other resources, is essential for transforming entrepreneurial intention into a strong and sustainable entrepreneurial culture throughout the university (Vásquez-Pauca et al., 2022; Zapata et al., 2024). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H14: Institutional Support will mediate the relationship between Entrepreneurial Intention and Entrepreneurial Culture.

2.6. Impact of Resources, Institutional Support, and Perception of Barriers on Entrepreneurial Culture

Entrepreneurial culture in a university depends not only on students’ attitudes and competencies but also on external factors such as available resources, institutional support, and the perception of entrepreneurial barriers (Bardales-Cárdenas et al., 2024; Gimenez-Jimenez et al., 2022). These elements can either facilitate or hinder the development of an environment conducive to entrepreneurship. The availability of resources and institutional support is essential for students to carry out their ideas and projects (Vásquez-Pauca et al., 2022; Zapata et al., 2024). At the same time, the perception of entrepreneurial barriers can represent a significant obstacle, limiting students’ active participation in entrepreneurship (Alferaih, 2022; Van Auken et al., 2006). Understanding how these factors interact and affect entrepreneurial culture is key to designing strategies that promote a more favorable environment for entrepreneurship within educational institutions (Gimenez-Jimenez et al., 2022; Vásquez-Pauca et al., 2022).

External resources and support play a fundamental role in the creation and strengthening of Entrepreneurial Culture in universities (Donaldson, 2021; Martínez-Martínez, 2022). When students have access to funding, mentorship, and networks, they can more easily overcome the initial challenges of entrepreneurship, fostering an environment where entrepreneurial initiatives are valued and promoted (Cenzano & González, 2021; Wathanakom et al., 2020). The availability of these resources not only facilitates the growth of individual projects but also contributes to the formation of a collective culture that supports and values entrepreneurship (Cenzano & González, 2021; Donaldson, 2021). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H15: External Resources and Support have a positive effect on Entrepreneurial Culture.

Institutional Support is crucial for the development of a strong entrepreneurial culture within the academic environment (Pedroza-Zapata & Silva-Flores, 2020; Zapata et al., 2024). Universities that offer incubation programs, advisory services, and specific resources for entrepreneurship make it easier for students to turn their ideas into viable businesses (Aceituno-Aceituno et al., 2018; Chávez Vera et al., 2023). This support not only enhances students’ ability to engage in entrepreneurship but also consolidates an entrepreneurial culture throughout the institution, creating an environment where entrepreneurship is an essential component of the educational experience (Aceituno-Aceituno et al., 2018; Vásquez-Pauca et al., 2022). Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H16: Institutional Support has a positive impact on Entrepreneurial Culture.

The Perception of Entrepreneurial Barriers can have a significant impact on Entrepreneurial Culture within a university (Diez, David et al., 2023; Zaidan et al., 2024). When students perceive numerous barriers to entrepreneurship, such as difficulties in accessing funding, lack of mentorship, or an unfavorable regulatory environment, these factors are likely to discourage their participation in entrepreneurial activities (Acheampong & Tweneboah-Koduah, 2018; Ghouse et al., 2024). This can limit the development of an entrepreneurial culture, as the perception of barriers acts as a brake on innovation and risk-taking (Bernal Suárez et al., 2021; Suryono et al., 2023). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H17: The Perception of Entrepreneurial Barriers has a negative influence on Entrepreneurial Culture.

2.7. Theoretical Research Model

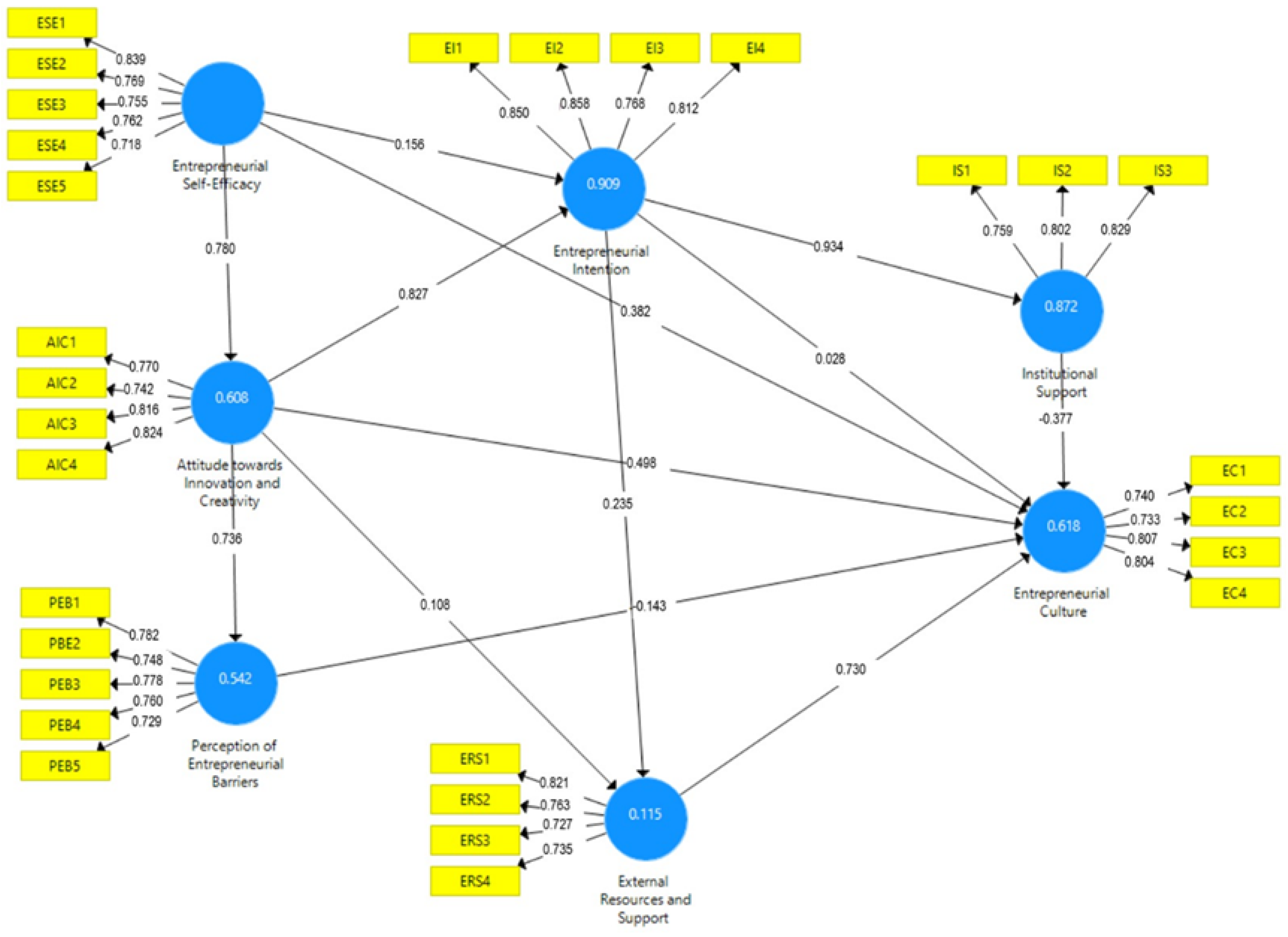

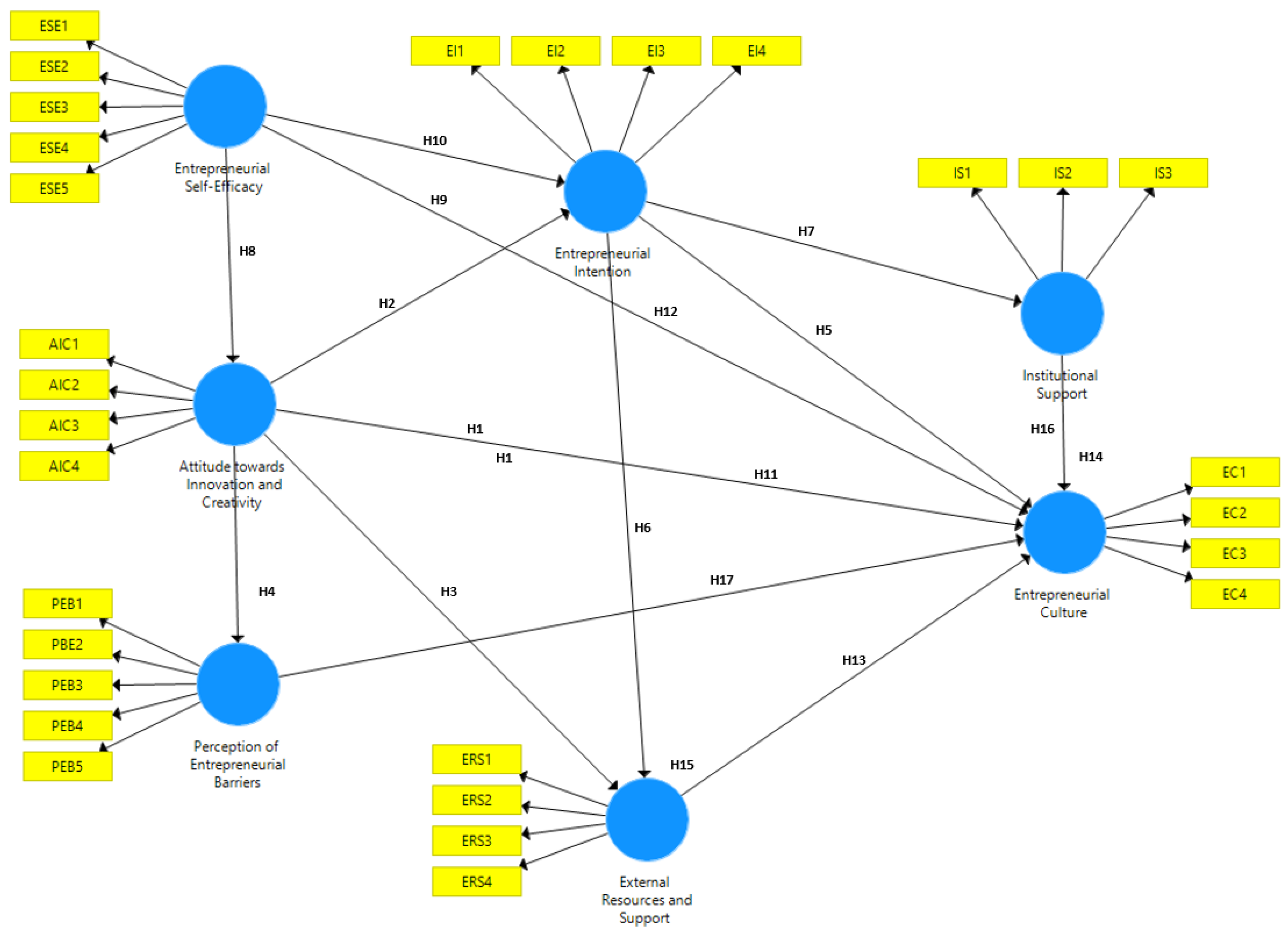

The research model developed in SmartPLS (Hair & Alamer, 2022) examines the main variables that influence the formation of Entrepreneurial Culture (EC) among university students. Key variables include Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy (ESE), Attitude toward Innovation and Creativity (AIC), Perception of Entrepreneurial Barriers (PEB), External Resources and Support (ERS), Institutional Support (IS), and Entrepreneurial Intention (EI), which acts as a mediating variable in several relationships. This model provides a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics that drive entrepreneurial culture in the academic environment (

Figure 1).

The novelty of this approach lies in the exploration of the interaction between factors such as the Perception of Barriers (PEB) and External Resources (ERS), as well as highlighting the central role of Entrepreneurial Intention (EI) as a mediator between several key variables. The model provides a solid foundation for designing educational strategies that foster an entrepreneurial spirit, emphasizing the importance of Institutional Support (IS) and available resources (ERS) in strengthening a robust Entrepreneurial Culture (EC) within universities.

3. Method

This study adopted a quantitative approach with a cross-sectional design, aiming to investigate the factors that influence entrepreneurial culture among university students (Hernández et al., 2018; Niño, 2019). The proposed model integrates seven key variables: the independent variables include Attitude toward Innovation and Creativity (AIC), Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy (ESE), External Resources and Support (ERS), Institutional Support (IS), and Perception of Entrepreneurial Barriers (PEB). Entrepreneurial Culture (EC) is considered the dependent variable, while Entrepreneurial Intention (EI) acts as a mediating variable, establishing relationships among the other variables.

3.1. Population and Sample of the Study

The target population for this study consisted of university students from a university in Lima, selecting those who participated in entrepreneurship-related activities or showed interest in the entrepreneurial field. No restrictions were placed on gender, age, or academic level, ensuring the relevance of the data collected (Hernández et al., 2018; Niño, 2019).

For participant selection, purposive sampling was used. Initially, the sample consisted of 1,112 students, but after the data cleaning and refinement process, the final sample included 948 participants. This sampling approach was appropriate to ensure that the students included met the specific criteria of the study, focused on analyzing the factors influencing entrepreneurial culture (Hernández et al., 2018). Purposive sampling is especially suitable when the aim is to test specific theories rather than generalize the results to a broader population, which is common in field research in social sciences (Hernández et al., 2018; Niño, 2019).

3.2. Data Collection Instrument

The data collection instrument was a questionnaire initially composed of 35 items. After a rigorous process of validation and refinement, it was reduced to 29 items, retaining only those that demonstrated greater clarity and relevance to the study’s objectives. Each item was measured on a 7-point Likert scale, where 1 corresponded to “strongly disagree” and 7 to “strongly agree,” allowing for an accurate capture of students’ perceptions and attitudes regarding the investigated variables.

The validation of the questionnaire was carried out by a panel of five experts in the fields of entrepreneurship and education, who assessed the coherence, clarity, and relevance of the items in relation to the key theoretical constructs of the study (Arias, 2019; Hernández et al., 2018). This process ensured that the questionnaire accurately measured aspects such as entrepreneurial culture, self-efficacy, innovation, and perceived barriers, ensuring its alignment with the proposed theoretical framework.

3.3. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Code of Ethics for Research of San Ignacio de Loyola University (USIL). The rights of participants were respected, data confidentiality was ensured, and the information collected was used responsibly, complying with the ethical standards in place at the institution.

3.4. Data Analysis

To assess potential common method variance (CMV) bias, Harman’s single-factor test (1976) was applied. According to this test, a single factor should not explain more than 50% of the total variance in the data (Kock, 2015; Podsakoff et al., 2003). The results indicated that the first factor explained 36.60% of the variance, so there was no significant CMV issue in this study.

Additionally, the correlation between constructs was analyzed. Correlations higher than 0.9 may indicate common method bias (Kock, 2015). In this case, the highest observed correlation was 0.801 between Attitude toward Innovation and Creativity (AIC) and Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy (ESE), which is below the 0.9 threshold, suggesting that no serious CMV issues were identified.

3.5. Data Normality

Although PLS-SEM does not require multivariate normality, data normality was verified using Mardia’s multivariate coefficient test, where the p-values were less than 0.05, confirming the non-normality of the data (Cain et al., 2017; Hair et al., 2019). However, since PLS-SEM is a non-parametric analysis, the lack of normality did not affect the validity of the model.

3.6. Structural Equation Modeling

For data analysis, Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was used with SmartPLS software version 3.1 (Chin, 1998; Hair & Alamer, 2022). This approach is particularly useful for modeling paths between latent constructs and is suitable for small samples and non-normal data (Hair et al., 2021; Sarstedt et al., 2019).

The analysis was conducted in two stages: first, the reliability and validity of the constructs were assessed to ensure the robustness of the model; second, the structural model was estimated, and the study hypotheses were analyzed with their respective significance levels (Becker et al., 2015; Cepeda Carrión et al., 2016). To evaluate the model, R², Q², and effect size f² indicators were used to interpret the influence of exogenous constructs on endogenous ones (Chin, 2010; Hair & Alamer, 2022) .

4. Results

4.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the survey respondents, consisting mostly of women (54.20%) and men (45.80%). Regarding age distribution, the largest group is between 18 and 30 years old (45.54%), followed by those under 18 (30.27%) and those over 30 years old (24.19%). Most respondents are in their 4th to 6th semester of study (42.04%), while 30.27% are in their 7th to 10th semester, and 27.68% are in the early semesters. In terms of involvement in entrepreneurship, 17.72% work full-time, 56.14% work part-time, and 26.13% are not involved in any entrepreneurial activity. Additionally, 75.38% have received entrepreneurship education, while 24.62% have not had access to such education.

4.2. Measurement Model Evaluation

In the measurement model evaluation, the reliability, validity, and collinearity scores of the latent constructs were analyzed, with the results presented in

Table 2. Reliability was determined using Cronbach’s alpha, rho_A, and composite reliability, all of which had values above 0.70, ensuring adequate internal consistency of the ítems (Becker et al., 2015; Hair et al., 2021). Convergent validity was assessed through the Average Variance Extracted (AVE), exceeding the threshold of 0.50 in all constructs, indicating that the items effectively capture the variance of each construct (Cepeda Carrión et al., 2016; Hair & Alamer, 2022). Furthermore, multicollinearity was evaluated using the Variance Inflation Factors (VIF), and all values were below 3.3, suggesting no significant collinearity issues (Chin, 2010; Hair & Alamer, 2022). These results confirm that the measurement model is reliable and valid for the data analyzed.

In the evaluation of the model’s discriminant validity, the Fornell-Larcker criteria and the Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT) were used. As shown in

Table 3, the Fornell-Larcker criterion was assessed by verifying that the square root of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) of each construct exceeded the correlations of that construct with the others, ensuring that the constructs measure different concepts and do not overlap (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Additionally, the HTMT criterion was used, which compares the relationships between constructs to identify whether they are sufficiently distinct (Henseler et al., 2015). The results showed that all HTMT ratios remained below the threshold of 0.900, ensuring discriminant validity in the model.

4.2. Common Method Bias or Variance

Common method bias occurs when the same individual responds to both the independent and dependent variables in a study, using similar items in a common context. Two methods were used to identify this bias: Harman’s single-factor test and the full collinearity test (VIF).

Harman’s single-factor test suggests that if common method bias exists, a single factor would explain more than 50% of the covariance among constructs. In this study, the value was 32.020%, below the threshold, indicating the absence of this bias (Fuller et al., 2016). Additionally, the full collinearity test (VIF) was conducted, introducing a random dummy variable to evaluate collinearity among constructs. A VIF higher than 3.3 would indicate potential common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). As shown in

Table 4, all VIF values are below 3.3, confirming the absence of collinearity issues and common method bias in the model.

4.3. Structural Path Model Analysis to Examine the Hypothesized Relationships

After evaluating the measurement model, the researchers proceeded to assess the structural model using the bootstrapping technique. The model was evaluated based on the coefficient of determination (R²) and the Q² statistics, which indicate the predictive accuracy and relevance of the model (Hair & Alamer, 2022).

Table 5 presents the R², adjusted R², and Q² values for different constructs. The coefficient of determination (R²) ranges from 0 to 1, where values closer to 1 indicate a higher predictive capacity of the model. In this study, the constructs “Attitude toward Innovation and Creativity” (0.608) and “Entrepreneurial Culture” (0.618) show high predictive capacity, while “Entrepreneurial Intention” presents a very high value of 0.909, indicating that the model is highly predictive for this variable. The constructs “External Resources and Support” (0.115) and “Perception of Entrepreneurial Barriers” (0.542) have moderate predictive capacity.

The adjusted R² values, which correct potential biases due to the number of variables in the model, also reflect consistency in the model’s predictive capacity. Additionally, Q² values greater than 0 for all constructs indicate that the model has predictive relevance (Hair & Alamer, 2022; Sarstedt et al., 2019). “Entrepreneurial Intention” (Q² = 0.875) and “Institutional Support” (Q² = 0.796) stand out for their high predictive relevance, further reinforcing the robustness of the structural model in these dimensions.

4.4. Results of Hypothesis Testing Using Bootstrapping

The hypothesis testing analysis using the bootstrapping method is shown in

Table 6 and

Figure 2, revealing that most of the proposed relationships in the model have significant support (Hair et al., 2021; Sarstedt et al., 2019). Attitude toward Innovation and Creativity (AIC) showed a positive impact on both Entrepreneurial Culture (EC) and Entrepreneurial Intention (EI), with β coefficients of 0.498 and 0.827, respectively, and p-values less than 0.001, indicating a high level of confidence in these relationships. Additionally, AIC also positively influenced External Resources and Support (ERS) and the Perception of Entrepreneurial Barriers (PEB), with significant coefficients of 0.108 and 0.736.

Entrepreneurial Intention (EI) also stood out for its positive effect on Entrepreneurial Culture (EC) and External Resources and Support (ERS), with coefficients of 0.728 and 0.235, respectively. However, the relationship between Entrepreneurial Intention and Institutional Support (IS) was especially strong, with a β coefficient of 0.934. Regarding Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy (ESE), it demonstrated a positive impact on AIC, EC, and EI, supporting its relevance in the model.

On the other hand, two relationships were not supported by the results: Institutional Support (IS) did not show a significant effect on Entrepreneurial Culture (β = -0.077, p = 0.274), and the same was true for the Perception of Entrepreneurial Barriers (PEB) on EC (β = -0.043, p = 0.432), suggesting that these factors do not play a crucial role in this context.

Figure 2.

Results of the structural model after bootstrapping analysis. Note: entrepreneurial self-efficacy (ESE), attitude towards innovation and creativity (AIC), perception of entrepreneurial barriers (PEB), external resources and support (ERS), institutional support (IS), entrepreneurial intention (EI), and entrepreneurial culture (EC). The coefficients of the significant relationships are shown next to the respective arrows.

Figure 2.

Results of the structural model after bootstrapping analysis. Note: entrepreneurial self-efficacy (ESE), attitude towards innovation and creativity (AIC), perception of entrepreneurial barriers (PEB), external resources and support (ERS), institutional support (IS), entrepreneurial intention (EI), and entrepreneurial culture (EC). The coefficients of the significant relationships are shown next to the respective arrows.

4.5. Results of the mediation analysis

The mediation analysis, presented in

Table 7, reveals that some of the proposed relationships in the model are partially mediated by intermediate variables, suggesting the presence of indirect mechanisms that strengthen certain connections between constructs (Hair & Alamer, 2022). Specifically, it is observed that Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy (ESE) exerts an indirect effect on Entrepreneurial Culture (EC) through Attitude towards Innovation and Creativity (AIC), with a mediation coefficient of 0.052 and a significant p-value of 0.012. This partial mediation indicates that, although ESE has a direct impact on EC, a significant portion of its effect is channeled through the strengthening of AIC. This suggests that individuals with higher entrepreneurial self-efficacy tend to develop more favorable attitudes towards innovation, which, in turn, promotes the development of an entrepreneurial culture.

Similarly, it is found that AIC influences EC indirectly through Entrepreneurial Intention (EI), with a mediation coefficient of 0.087 (p < 0.001). This finding reinforces the importance of EI as a key mediator, showing that innovative attitudes not only contribute directly to entrepreneurial culture but also do so significantly through entrepreneurial intention. This highlights that individuals with a high propensity for innovation and creativity are more likely to develop a strong intention to start a business, which ultimately leads to a greater consolidation of entrepreneurial culture in their environments.

However, not all proposed relationships show significant mediation. Specifically, the indirect effects of Entrepreneurial Intention (EI) through External Resources and Support (ERS) and Institutional Support (IS) were not significant, with coefficients that did not meet the significance threshold. This suggests that, although EI may have a direct effect on EC, ERS and IS do not act as effective mediators in this case. These results may indicate that, although access to resources and institutional support are relevant, their influence does not seem to be indirectly channeled through EI, at least within the proposed theoretical framework.

5. Discussion

The central objective of this study was to examine how attitude toward innovation and creativity, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and institutional support influence the consolidation of entrepreneurial culture among university students in Peru. These factors have been widely studied in various educational contexts, but there is a significant gap in the literature regarding their specific impact within the Peruvian university setting (Al-Jubari, 2019; Bullón-Solís et al., 2023; Cenzano & González, 2021).

To address this issue, the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991), was employed, which has proven to be a robust framework for understanding how attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control influence the intention to start a business and, consequently, the creation of an entrepreneurial culture (Armitage & Conner, 2001; Henley et al., 2017; Sampene et al., 2023).

This theoretical approach allowed for the unraveling of the complex interactions between key variables that, according to previous research, are fundamental for fostering a strong entrepreneurial ecosystem in higher education institutions (Aliedan et al., 2022; Calanchez Urribarri et al., 2022; Tessema Gerba, 2012). In the Peruvian context, where entrepreneurship plays a crucial role in job creation and reducing inequalities, strengthening the entrepreneurial culture in universities is vital to promoting sustainable economic development (Agu et al., 2021; Chávez Vera et al., 2023; Vásquez-Pauca et al., 2022).

The study revealed that attitude toward innovation has a positive effect on entrepreneurial culture in Peruvian universities. Students who promote innovation strengthen an environment conducive to the creation of new ideas and ventures (Ceresia & Mendola, 2020; Yung et al., 2023). This is consistent with studies that emphasize the importance of an innovative attitude for the development of an entrepreneurial culture (Audretsch & Belitski, 2021; Lyu et al., 2024). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy also has a significant impact, as students with high confidence in their entrepreneurial abilities are more likely to adopt innovative attitudes and foster entrepreneurial culture (Eniola, 2020; Shi et al., 2019). This finding aligns with studies that highlight self-efficacy as a key factor for entrepreneurship (Jiménez et al., 2015).

Both external resources and institutional support are essential for strengthening entrepreneurial culture, enabling students to access funding and mentorship (Bernal Suárez et al., 2021; Wang & Fu, 2023). Institutional support, through programs and resources, is also crucial for consolidating this entrepreneurial environment (Aceituno-Aceituno et al., 2018; Zapata et al., 2024).

The results also showed that entrepreneurial self-efficacy acts as a partial mediator in the relationship between attitude toward innovation and entrepreneurial culture. This means that students who are confident in their entrepreneurial abilities develop a greater disposition toward innovation, which strengthens their contribution to entrepreneurial culture (Jiménez et al., 2015; Tafadzwa Maziriri et al., 2019). This finding is consistent with previous studies that highlight how entrepreneurial self-efficacy not only drives creativity but also reinforces leadership and persistence in the university context (Eniola, 2020; Zaleskiewicz et al., 2020).

Additionally, it was found that attitude toward innovation and creativity indirectly influences entrepreneurial culture through entrepreneurial intention (Neneh, 2022). This reinforces the idea that students with a strong inclination toward innovation not only develop clear intentions to start a business but also drive the consolidation of an entrepreneurial culture (Bullón-Solís et al., 2023; Jena, 2020). Entrepreneurial intention, therefore, emerges as a key factor in connecting innovative attitudes with the creation of a strong entrepreneurial culture in the university setting (Anjum et al., 2021; Hassan et al., 2020).

However, some results suggest that neither external resources nor institutional support acted as significant mediators in the relationship between entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial culture. This indicates that, while access to resources and institutional support are important for entrepreneurship, their influence is not channeled indirectly through entrepreneurial intention (Nguyen et al., 2019; Vásquez-Pauca et al., 2022). This finding differs from previous studies, suggesting the need for further investigation into how these factors may influence specific contexts.

The findings of this study provide important theoretical implications for the field of university entrepreneurship, specifically in the Peruvian context. Firstly, the results reinforce the usefulness of the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991) as an appropriate framework to understand how attitudes toward innovation, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and institutional support influence entrepreneurial culture (Henley et al., 2017; Sampene et al., 2023). These findings are consistent with previous research demonstrating that a positive attitude toward innovation and confidence in one’s abilities are key factors in the development of an entrepreneurial culture (Ceresia & Mendola, 2020; Shi et al., 2019). (Ceresia & Mendola, 2020; Shi et al., 2019).

This study also highlights the importance of self-efficacy as a partial mediator, providing new insights into how confidence in entrepreneurial abilities can strengthen the attitude toward innovation and, in turn, entrepreneurial culture (António Porfírio et al., 2023; Danish et al., 2019). This aligns with studies suggesting that entrepreneurial self-efficacy not only directly influences the intention to start a business but also mediates its relationship with entrepreneurial culture, fostering a more conducive environment for the creation of new ventures (Eniola, 2020; Jiménez et al., 2015).

Additionally, the results reveal that institutional support and external resources, while important, do not act as significant mediators between entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial culture in this context. This presents a theoretical challenge that suggests the need to reexamine the role of these factors in specific cultural and educational contexts such as Peru(Nguyen et al., 2019; Vásquez-Pauca et al., 2022). This theoretical contribution is particularly valuable for designing future theoretical models that explore the interactions between these constructs in university settings.

The study’s results have significant practical implications for universities and educational policies in Peru. Firstly, fostering a positive attitude toward innovation and creativity should be a priority in educational programs, as these factors have been shown to be key in consolidating a strong entrepreneurial culture (Audretsch & Belitski, 2021; Calanchez Urribarri et al., 2022). Universities should implement programs that not only teach technical skills but also cultivate an innovative mindset among students, providing spaces for experimentation and the development of new ideas (Aliedan et al., 2022; Lyu et al., 2024).

Secondly, special attention should be given to strengthening entrepreneurial self-efficacy, as it has a direct impact on both the attitude toward innovation and entrepreneurial culture. Institutions can achieve this by creating mentorship networks, incubation programs, and opportunities for students to face real entrepreneurial challenges, which will increase their confidence in their entrepreneurial abilities (Eniola, 2020; Shi et al., 2019). Investing in the development of this confidence will not only enhance students’ ability to start businesses but also positively influence their peers and the university environment.

Lastly, although external resources and institutional support did not act as significant mediators, they remain crucial elements for facilitating entrepreneurship. Universities should continue providing structural support, such as access to funding, business incubators, and legal advice, to help students turn their ideas into viable businesses (Nguyen et al., 2019; Vásquez-Pauca et al., 2022). These measures will not only foster an entrepreneurial culture but also contribute to long-term economic and social development in Peru.

6. Conclusions

The results of this study confirmed the positive influence of attitude toward innovation and creativity, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and institutional support on the consolidation of an entrepreneurial culture among university students in Peru. It was observed that a positive attitude toward innovation and creativity fosters the creation of a university environment that values the generation of new ideas and entrepreneurial solutions, significantly contributing to strengthening the entrepreneurial culture.

Furthermore, entrepreneurial self-efficacy played a crucial role, as students who are confident in their entrepreneurial abilities are more inclined to actively participate in the creation of an entrepreneurial culture. However, institutional support and external resources did not show a strong mediating role, highlighting the need to further examine these elements in specific contexts.

This study has expanded the application of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) by analyzing how factors such as attitude toward innovation and creativity, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and institutional support influence the formation of an entrepreneurial culture in a university context. While TPB has been widely used in research on entrepreneurial intention, this work provides empirical evidence from a developing country, such as Peru, which has been underexplored in international academic literature.

One of the most important contributions is the confirmation of the key role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy as a partial mediator between attitude toward innovation and the consolidation of an entrepreneurial culture. This reinforces the relevance of self-efficacy not only as a factor that directly influences entrepreneurial intention but also as a facilitating element that enhances other variables, such as creativity and innovation, within the university ecosystem.

Additionally, this study highlights that, although institutional support and external resources are essential elements for entrepreneurship, their influence does not act as a significant mediator in the process of forming an entrepreneurial culture, challenging previous research that has pointed to their mediating role. This finding suggests the need to rethink how these factors interact in different educational and cultural contexts, particularly in developing countries.

Finally, this research offers a new approach to analyzing contextual factors in university entrepreneurship, emphasizing the need to further investigate the role of government policies and the economic environment as possible influences on entrepreneurial culture, which could enrich future theoretical models.

This study presents several limitations that should be considered when interpreting its results. Firstly, the cross-sectional nature of the research prevents observation of how the variables evolve over time. A longitudinal approach would allow for a deeper analysis of the dynamics between attitude toward innovation, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial culture (Ajzen, 2020; Henley et al., 2017). Additionally, the sample was limited to students from a single Peruvian university, which restricts the generalization of the findings to other institutions and international contexts (Bullón-Solís et al., 2023). Expanding the sample to a national or international level could provide more generalizable results.

Additionally, although variables such as institutional support and external resources were included, other important factors that could influence entrepreneurial culture, such as the economic environment and government policies, were not considered in this study. These factors could enrich future analyses. Finally, although the Theory of Planned Behavior was used as the theoretical framework, it is recommended to consider other theoretical models that include factors such as intrinsic motivation or entrepreneurial resilience, which would allow for a more holistic approach to the phenomenon.

Based on the findings and the limitations mentioned, several opportunities for future research are identified. Firstly, it is recommended to conduct longitudinal studies that allow for the analysis of how attitude toward innovation, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial culture evolve over time. This would provide a more dynamic and comprehensive perspective on the interactions between these variables. Additionally, expanding the study to different universities in Peru and other countries would facilitate the comparison of results and strengthen the external validity of the findings.

Another interesting area for future research would be the inclusion of contextual factors such as the economic environment, government policies, and access to financing, which could significantly influence the development of entrepreneurial culture among university students. Analyzing these variables would allow for a better understanding of the barriers and opportunities that entrepreneurs face in different contexts.

Finally, it is suggested to explore other theoretical models that include variables such as intrinsic motivation, entrepreneurial resilience, or achievement orientation, which would enrich the analysis of factors that influence entrepreneurial intention. These future investigations would contribute to a deeper understanding of university entrepreneurship and provide stronger foundations for the design of educational programs and public policies.

References

- Abdu, M.; Jibir, A. Determinants of firms innovation in Nigeria. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences 2018, 39(3), 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboobaker, N.; Renjini, D. Human capital and entrepreneurial intentions: Do entrepreneurship education and training provided by universities add value? On the Horizon 2020, 28(2), 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceituno-Aceituno, P.; Casero-Ripollés, A.; Escudero-Garzás, J.-J.; Bousoño-Calzón, C. University training on entrepreneurship in communication and journalism business projects. Comunicar 2018, 26(57), 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, G.; Tweneboah-Koduah, E.Y. Does past failure inhibit future entrepreneurial intent? Evidence from Ghana. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 2018, 25(5), 849–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agu, A.G.; Kalu, O.O.; Esi-Ubani, C.O.; Agu, P.C. Drivers of sustainable entrepreneurial intentions among university students: An integrated model from a developing world context. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 2021, 22(3), 659–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 1991, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 2002, 32(4), 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies 2020, 2(4), 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawamleh, M.; Francis, Y.H.; Alawamleh, K.J. Entrepreneurship challenges: The case of Jordanian start-ups. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 2023, 12(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alferaih, A. Starting a New Business? Assessing University Students’ Intentions towards Digital Entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights 2022, 2(2), 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliedan, M.M.; Elshaer, I.A.; Alyahya, M.A.; Sobaih, A.E.E. Influences of University Education Support on Entrepreneurship Orientation and Entrepreneurship Intention: Application of Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14(20), 13097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jayyousi, O.; Al-Alawi, A.; Al-Mahamid, S.; Bugawa, A. (2019). Entrepreneurial University and Organizational Innovation: The Case of Arabian Gulf University, Bahrain. En A. Visvizi, M.D. Lytras, A. Sarirete (Eds.), Management and Administration of Higher Education Institutions at Times of Change (pp. 117-136). Emerald Publishing Limited. [CrossRef]

- Al-Jubari, I. College Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention: Testing an Integrated Model of SDT and TPB. SAGE Open 2019, 9(2), 215824401985346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alva, E. Disappearance of Micro Enterprises in Peru. Factors in Their Death Rate. The Lima District Case. Econommía y Desarrollo 2017, 158, 76–90. [Google Scholar]

- Alwakid, W.; Aparicio, S.; Urbano, D. The Influence of Green Entrepreneurship on Sustainable Development in Saudi Arabia: The Role of Formal Institutions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18(10), 5433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M.E.; Borrego, M.; Boklage, A. Self-efficacy and belonging: The impact of a university makerspace. International Journal of STEM Education 2021, 8(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, T.; Farrukh, M.; Heidler, P.; Díaz Tautiva, J.A. Entrepreneurial Intention: Creativity, Entrepreneurship, and University Support. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. [CrossRef]

- António Porfírio, J.; Augusto Felício, J.; Carrilho, T.; Jardim, J. Promoting entrepreneurial intentions from adolescence: The influence of entrepreneurial culture and education. Journal of Business Research 2023, 156, 113521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, F. El Proyecto de Investigación, introducción a la metodología científica, 8va ed.; Episteme: 2019.

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology 2001, 40(4), 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atmono, D.; Rahmattullah, M.; Setiawan, A.; Mustofa, R.H.; Pramudita, D.A.; Ulfatun, T.; Reza, R.; Mustofa, A. The effect of entrepreneurial education on university student’s entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE) 2023, 12(1), 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.; Belitski, M. Towards an entrepreneurial ecosystem typology for regional economic development: The role of creative class and entrepreneurship. Regional Studies 2021, 55(4), 735–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backes, D.S.; Müller, L.D.B.; Mello, G.B.D.; Marchiori, M.R.T.C.; Büscher, A.; Erdmann, A.L. Entrepreneurial Nursing interventions for the social emancipation of women in recycling. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP 2022, 56, e20210466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardales-Cárdenas, M.; Cervantes-Ramón, E.F.; Gonzales-Figueroa, I.K.; Farro-Ruiz, L.M. Entrepreneurship skills in university students to improve local economic development. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 2024, 13(1), 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrales Martínez, A.; Rodríguez Gutiérrez, P.I. Mujeres emprendedoras y actividades informales de comercio en organizaciones virtuales: Discusión teórico-metodológica. VISUAL REVIEW. International Visual Culture Review / Revista Internacional de Cultura Visual 2023, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos-Báez, A.; Martínez-González, J.A.; García-Rodríguez, F.J.; Gómez Galán, J. Entrepreneurial competence perceived by university students: Quantitative and descriptive analysis. JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES 2022, 15(2), 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataineh, M.J.; Marcuello, C.; Sánchez-Sellero, P. Toward sustainability: The role of social entrepreneurship in creating social-economic value in renewable energy social enterprises. REVESCO. Revista de Estudios Cooperativos 2023, 143, e85561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, R. SmartPLS 3.3. SmartPLS GmbH, Boenningstedt. 2015. http://www.smartpls.com.

- Berman, A.; Cano-Kollmann, M.; Mudambi, R. Innovation and entrepreneurial ecosystems: Fintech in the financial services industry. Review of Managerial Science 2022, 16(1), 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal Suárez, A.L.; Pinzón Carreño, K.D.; Gutiérrez Mejía, D.P.; Colmenares Botía, L.L. Local Economic Development Opportunities that could be potentialized through International Cooperation, in the Agricultural Sector of the Municipality of Socha—Boyacá. Revista de Economía del Caribe 2021, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beugelsdijk, S. Entrepreneurial culture, regional innovativeness and economic growth. Journal of Evolutionary Economics 2007, 17(2), 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsi, B.; Dőry, T. Perception of multilevel factors for entrepreneurial innovation success: A survey of university students. Acta Oeconomica 2020, 70(4), 615–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscán Carroz, M.C.; Meleán Romero, R.A.; Chávez Vera, K.J.; Calanchez Urribarri, Á. Emprendimiento peruano en el marco del desarrollo sostenible. Retos 2023, 13(26), 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, S.W.; Kim, P.H.; Klein, P.G.; McMullen, J.S.; Wennberg, K. Policy for innovative entrepreneurship: Institutions, interventions, and societal challenges. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 2021, 15(2), 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigas, J.; Gonçalves, F.; Marques, H.; Gonçalves, J. Role of a media arts gallery in a polytechnic university to enhance entrepreneurship. HUMAN REVIEW. International Humanities Review / Revista Internacional de Humanidades 2023, 18, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, Y.; Li, S.; Huang, Y. Research on the influencing factors of Chinese college students’ entrepreneurial intention from the perspective of resource endowment. The International Journal of Management Education 2023, 21(3), 100832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buli, B.M.; Yesuf, W.M. Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions: Technical-vocational education and training students in Ethiopia. Education + Training 2015, 57, 891–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullón-Solís, O.; Carhuancho-Mendoza, I.; Valero-Palomino, F.R.; Moreno-Rodríguez, R.Y. University youth entrepreneurship: Approach from attitude, education and behavioral control. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia 2023, 28(Especial 9), 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahigas, M.M.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Persada, S.F.; Ong, A.K.S.; Nadlifatin, R. Understanding the perceived behavior of public utility bus passengers during the era of COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines: Application of social exchange theory and theory of planned behavior. Research in Transportation Business Management 2022, 45, 100840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, W.; Lysova, E.I.; Khapova, S.N.; Bossink, B.A.G. Does Entrepreneurial Leadership Foster Creativity Among Employees and Teams? The Mediating Role of Creative Efficacy Beliefs. Journal of Business and Psychology 2019, 34(2), 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, M.K.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, K.-H. Univariate and multivariate skewness and kurtosis for measuring nonnormality: Prevalence, influence and estimation. Behavior Research Methods 2017, 49(5), 1716–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calanchez Urribarri, A.; Chavez Vera, K.; Reyes Reyes, C.; Ríos Cubas, M. Innovative performance to strengthen the culture of entrepreneurship in Peru. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia 2022, 27(100), 1837–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsrud, A.; Brännback, M. Entrepreneurial Motivations: What Do We Still Need to Know?: JOURNAL OF SMALL BUSINESS MANAGEMENT. Journal of Small Business Management 2011, 49(1), 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenzano, C.H.; González, D. STUDY OF THE START-UP ECOSYSTEM IN LIMA, PERU: CHALLENGES ON THE WAY TO 2030. 30th Annual Conference of the International Association for Management of Technology (IAMOT 2021) 2021, 938–952. [CrossRef]

- Cepeda Carrión, G.; Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Roldán, J.L. Prediction-oriented modeling in business research by means of PLS path modeling: Introduction to a JBR special section. Journal of Business Research 2016, 69(10), 4545–4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceresia, F.; Mendola, C. Am I an Entrepreneur? Entrepreneurial Self-Identity as an Antecedent of Entrepreneurial Intention. Administrative Sciences 2020, 10(3), 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez Vera, K.J.; Velita, J.; Rosas, C. Peruvian entrepreneurship: Factors and interventions that facilitate its development. Revista de Ciencias Sociales. [CrossRef]

- Chin 2023, W.W. Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Quarterly 1998, 22(1), vii–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. Bootstrap Cross-Validation Indices for PLS Path Model Assessment. En V. Esposito Vinzi 2010, W.W. Chin, J. Henseler, H. Wang (Eds.), Handbook of Partial Least Squares (pp. 83-97). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [CrossRef]