1. Introduction

Adolescence, generally defined as the period from 13 to 18 years of age, is a time of rapid and dramatic physical, emotional, and social change. Alongside the hormonal and physical changes that occur during puberty, adolescence is marked by significant psychosocial developments in the cognitive, emotional and self-concept domains, exposing adolescents to increased risk with respect to mental health problems [

1]. As a result, many mental health difficulties seen over the lifespan first appear during adolescence [

2].

The mental health status of adolescents has significant impacts on how these individuals engage with various aspects of their lives. Mental disorders – along with substance use disorders – are the leading causes of disability in adolescents, accounting for a quarter of disability in young people worldwide [

3]. The National Children’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy [

4] noted that, in 2015, “anxiety, depressive disorders and conduct disorders accounted for three of the five leading causes of disease burden for children aged 5-14 years” (p.17) [

4]. Many mental health problems first seen in adolescence will also persist into adulthood [

1]. Even those who no longer have a diagnosable disorder as adults have been found to function at a lower level throughout their adult years than those with no history of a mental disorder [

4].

1.1. Importance of Healthy Peer Relationships for Positive Mental Health

Good peer relationships are essential for the healthy social development of children and adolescents [

5,

6], serving a protective function against the development of mental health problems. Conversely, negative peer relations have been found to have adverse effects on mental health, forecasting maladaptive social, emotional and behavioral developmental trajectories [

7]. This is of particular significance during adolescence, as peer influences become increasingly important. If children and adolescents are unable to establish and maintain positive peer relationships or friendships, this can increase the risk of antisocial behaviors, substance abuse, and psychological problems in later life [

8].

A range of factors that are critical in forming positive peer relationships in adolescence have been identified. Amongst these, social competence, which refers to an individual’s ability to adjust to different or variable contexts, and to modify his or her behavior based on the demands of each situation, has been identified as crucial for forming positive peer relations. Young people with low social competence often fail to adapt their behavior effectively in different social contexts, and are thus more likely to experience victimization (bullying) by peers [

9]. Various mental health disorders place individuals at heightened risk of exhibiting social competence impairments during the adolescent years.

1.2. Attention-Deficit Symptomatology, Peer Relationships and Mental Health

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is the most common childhood neurodevelopmental disorder worldwide [

10], affecting approximately 7.8% of Australian children and adolescents [

11]. It is characterized by persistent, age-inappropriate inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that interferes with functioning across multiple settings, having effects in the domains of cognition, attention, behavior and emotion [

12,

13]. ADHD is characterized as predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive, or combined presentation [

12], depending on the dominant nature of the symptoms exhibited.

Young people with ADHD have been found to confront significant challenges in forming positive peer relationships [

14,

15]. Various social risk factors tend to be accentuated in young people with ADHD, which include:

- (i)

A lack of inhibition, which can lead to problems in co-operating or taking turns, as well as overbearing, intrusive or annoying behavior, which can be aversive to peers [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

- (ii)

Socio-cognitive deficits, which can precipitate failures to adjust responses appropriately in different social contexts, difficulties in recognizing social cues, and misunderstandings of peers’ intentions and behaviors [

9,

15].

- (iii)

Emotional dysregulation, which can prompt reactivity and frustration, having an adverse effect on behavior in social situations [

16,

20].

Peer rejection and victimization are two of the most serious relationship difficulties commonly experienced by adolescents with ADHD. More than half of children and young people with ADHD have been found to be rejected by their peers [

21]. Children and adolescents with ADHD are not only at higher risk of becoming victims of bullying by peers [

9,

14,

19], but are also more likely to act as perpetrators of bullying than those without ADHD [

15,

22,

23]. For example, one study [

23] indicated that 57.7% of 9- to 14-year-olds with ADHD reported having been victimized, bullying others, or both, as opposed to only 13.6% of those in a comparison group.

1.3. Sub-Clinical ADHD Symptomatology and Peer Relationships

In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), the notion of ‘presentations’ of ADHD reflects research evidence that ADHD is not a fixed disorder [

13]. Rather, its expression is changeable across different stages of life and within varying contexts. Given this, an individual with ADHD may display varying degrees of hyperactivity-impulsivity or inattention, and move forward as well as backward along this presentation continuum at different points in their lives. This can mean that some young people will have difficulties related to ADHD symptoms without attracting a formal diagnosis [

24]. Various researchers [

4,

25] concur that even when the severity of some children’s mental disorder symptoms falls below formal diagnostic thresholds, these individuals may nevertheless suffer significant functional impairments.

These points underscore the need for an increased awareness of sub-clinical ADHD symptomatology, and its implications for longer-term outcomes, including those associated with peer relationships and mental health. From this perspective, even when impairments are ‘milder’ on the presentation continuum and thus do not attract a formal ADHD diagnosis, adolescents exhibiting these symptoms are still worthy of concern due to the severe immediate and long-term consequences of such symptoms.

1.4. The Present Study

The research reported in this paper was designed to address two primary goals. The first was to evaluate the extent to which attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms measured at the start of the study (Timepoint 1, November 2018) predicted peer relationships in Western Australian adolescents over an extended time period (through to April/May 2019, Timepoint 2). The second goal was to determine whether mental health measures from a further data collection timepoint (Timepoint 3, July/August 2020) were predicted significantly by ADHD symptoms at Timepoint 1, and also, whether peer relationships, measured at Timepoint 2, were significant mediators of any relationships between ADHD symptoms at Timepoint 1 and mental health outcomes at Timepoint 3. The specific research questions addressed in the study were:

Are young people with ADHD symptoms more likely to report known risk factors in terms of peer relationships (school belongingness, being a bully victim, bullying, and poor or no friendships) than those without such symptoms over the longer term?

Are young people with ADHD symptoms more likely to fare poorly in the longer term in terms of their mental health, as measured by levels of general wellbeing, depression, and worry – amount and frequency?

Are any observed relationships between ADHD symptoms and long-term mental health significantly mediated by the impact of ADHD on peer relationships?

2. Materials and Methods

This study was undertaken as part of a larger longitudinal project examining trajectories of loneliness and mental health in adolescents [

14]. Thus, participants formed a community sample, in which no deliberate attempts were made to include certain proportions of young people with ADHD symptoms (formally diagnosed or otherwise). The data for the present study were collected at three timepoints: Timepoint 1 – November 2018; Timepoint 2 – April/May 2019; and Timepoint 3 - July/August 2020 (please note that Timepoint 3 in the present study was Timepoint 4 in the broader study).

2.1. Participants

To be included in the study, participants needed to have complete data for all measures across the three timepoints. In all, 1246 participants met these criteria,

n=507 males with a mean age of 14.05 years (

SD = 1.47 years), and

n=739 females, with a mean age of 14.52 years (

SD = 1.31 years). Participants were enrolled across seven randomly selected schools in Perth, Western Australia (five state/government and two non-government). These schools represented a range of socioeconomic status areas as indicated by their Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage (ICSEA). ICSEA is set at an average of 1000 (

SD = 100), with higher ICSEA values indicating higher levels of educational advantage for students attending the school [

26]. The ICSEA values for schools in the study ranged from 939 to 1191, thus representing a range around the average level.

2.2. Instruments

Participants completed seven instruments across the three study timepoints.

2.2.1. Timepoint 1: Measures of ADHD Symptoms and Existing Peer Problems

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, Youth Self-Report Version (SDQ) [

27], a brief screening measure for adolescents aged from 11 to 17 years., was used to assess ADHD symptoms and existing peer problems. This instrument comprises 25 items which focus on difficulties in the emotional, conduct, hyperactivity/inattention, and peer relationship domains (five items each), with an additional prosocial behavior subscale (five items). Two subscales from the SDQ were used in the present study. These were the Hyperactive/Inattentive (ADHD) subscale and the Peer Relationship Problems subscales. Following rescoring of reverse-worded items, scores for the five items within each of these were averaged to provide a total score for each subscale.

2.2.2. Timepoint 2: Peer Relationship Measures

The 24-item Perth A-Loneness Scale (PALs) [

28] was used to measure loneliness in the current study. The PALs uses a six-point scale that ranges from ‘Never’ (0) to ‘Always’ (5), with higher scores indicating higher levels of loneliness. Houghton and colleagues [

14,

28,

29,

30] have conducted numerous studies in which the PALs has been demonstrated to have strong psychometric properties, and to comprise four correlated factors, which are presented as separate subscales in the measure. The two subscales used in the present study were friendship related loneliness (e.g., having trustworthy friends) and isolation (e.g., having few friends). Following reversals of relevant items, item scores were averaged for each of these two subscales to produce a single score for the friendship related loneliness and isolation factors respectively.

Items from the School Connectedness subscale of the California Healthy Kids Survey (CHKS) were used to assess perceived school belongingness in the study. The CHKS is part of the overall California School Climate, Health, and Learning Survey (Cal-SCHLS) System. Resnick et al. [

31] previously developed a measure for school belongingness, and the four items in the secondary CHKS are modified versions of items from that measure. The CHKS has been found to be theoretically and psychometrically sound [

32]. The items from the school belongness subscale used in the present study were: “I feel close to people at/from this school”; “I am happy with/to be at this school”; “I feel like I am part of this school”; and “I feel safe in my school”. A total score for school belongingness was calculated by averaging scores from these four items.

Two researcher-constructed subscales were used to assess the frequency with which participants experienced bullying, either as a victim or as a perpetrator (four questions on each). The items in each subscale measured different forms of bullying (i.e., physical, verbal, social and cyber-bullying). Average scores were generated for each of these subscales using the mean frequency scores of the four relevant items (i.e., “How often have you been physically/verbally/socially/cyber bullied?” and “How often have you taken part in physical/verbal/social/cyber bullying?”).

2.2.3. Timepoint 3: Mental Health Measures

The Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS), a brief version of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS), was used to provide a general measure of wellbeing at Timepoint 3. The SWEMWBS uses seven of the WEMWBS’s original 14 statements about thoughts and feelings. The seven statements are positively worded with five response categories, ranging from ‘none of the time’ to ‘all of the time’. The SWEMWBS has been validated for use in populations aged 15 to 21 years [

33]. The scores used in the present study were the Rasch-based transformed scores from the SWEMWBS, as these transformed scores approximate an interval level scale [

34].

The Children’s Depression Inventory, Self-Report (Short) version was used to assess symptoms of depression. The CDI is available both in its original 27-item version and in a briefer 12-item version (the CDI-2). The latter version typically takes between 5 and 15 minutes to complete. Each item in both forms of the CDI has three statements, and the respondent is asked to select the one answer that best describes their feelings over the past two weeks. The CDI-2 has been reported to have excellent psychometric properties [

35] and yields a Total Score that is very comparable to the one produced by the full-length version. The total CDI-2 raw score was used in the present study.

Two subscales from the Perth Adolescent Worry Scale (PAWS) [

36], a brief, psychometrically sound measure of worry for use with adolescents, was used as an index of wellbeing in the study. The PAWS comprises 12 items, six relating to Peer Relationships and six relating to Academic Success and the Future. Psychometric evaluations have affirmed that this instrument possesses excellent psychometric properties in terms of its reliability, construct validity, and criterion-related validity [

36]. There are two primary components of the PAWS, which relate to the frequency and the amount of worry experienced by respondents. The average rating for each component was used in the present study.

2.3. Data Collection Procedures

Approval to conduct the study was obtained from the University of Western Australia Human Ethics Committee (approval number 2023/ET000730) as well as the Western Australian Department of Education (approval number D18/0207029). Each of the participating school principals participating also provided their consent for the study to be conducted, and informed consent and/or verbal assent were obtained from each of the individual study participants and their parents. Participants completed the surveys online during their normal lessons across four separate occasions, over a period of approximately 28 months. At each data collection point, the survey was made available for 30 days to allow all students to access and complete the questionnaires.

Each participant was provided with a unique identification code for the entire study period. This permitted students to remain anonymous to the researchers, and also ensured that data could be linked precisely across the three study timepoints. To ensure rigorous study implementation procedures, each school principal nominated one teacher who was responsible for ensuring that the study processes were carried out with fidelity in his/her school. Each of these teachers received thorough written instructions to ensure that the procedures were carried out in a standardized manner across the study schools.

3. Results

Results are presented in this section in line with the research questions posed. Prior to conducting any analyses, data screening tests for all relevant assumptions of each intended statistical procedure were performed to ensure compliance with these underlying assumptions. All such analyses produced satisfactory results with respect to the distributional assumptions of regression analysis. Initially, all analyses were performed separately for males and females. However, in each case, it was found that the pattern of relationships that emerged was similar across the two subsamples. As a result, the two samples (males and females) were combined for the purposes of all subsequent analyses.

3.1. Research Question 1: ADHD Symptomatology and Peer Relationships

The first research question posed for the study was, Are young people with ADHD symptoms more likely to report known risk factors in terms of peer relationships (school belongingness, bullying, and poor or no friendships) than those without such symptoms? To address this question controlling for age, four hierarchical Multiple Regression Analyses (MRAs) were performed with age and SDQ ADHD scores from Timepoint 1 entered as independent variables (respectively), and the five peer relationship measures completed at Timepoint 2 (the PALS – Friendships factor; the PALS – Isolation factor; Being Bullied, Bullying Others; and the CHKS school belonging subscale) entered as dependent variables.

Furthermore, to ensure that ADHD scores made a

unique contribution to predicting peer relationship scores over and above any peer problems that participants were already exhibiting at Timepoint 1, a second set of hierarchical MRAs was performed, adding scores from the SDQ Peer Problems subscale prior to the SDQ ADHD subscale scores. The latter analysis was used to provide a stringent test of the unique contribution made to prediction by the ADHD subscale scores, that is, whether ADHD symptoms predicted peer relationship issues over and above any peer problems already exhibited at Timepoint 1. Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations for the male and female subsamples are shown in

Table 1, with outcomes of the MRAs in

Table 2.

As indicated, ADHD symptoms, as measured by the SDQ ADHD subscale, made a significant contribution to predicting all five of the peer relationship variables at Timepoint 2, over and above any variance accounted for by age. The R2 for each of these ranged from .04 through to .10 (4-10% variance accounted for by ADHD symptomatology). Given the large number of factors that can affect peer relationships, it is significant that these percentages are accounted for by ADHD symptoms alone. Thus, even when a formal diagnosis has not been delivered, exhibiting elevated levels of ADHD symptoms poses a significant long-term risk factor for difficulties in peer relationships.

Further affirmation of the unique contribution to predicting peer problems made by ADHD symptomatology was evident in the second MRA conducted for each of the dependent measures, in which the SDQ Peer Problems scores were entered prior to ADHD symptom scores. Again, in each case, ADHD symptoms made a statistically significant unique contribution to predicting peer problems over and above age and any peer problems that already existed. In some cases, the R2 did suggest that the addition of peer problems reduced the impact of the ADHD symptoms, but in the case of the being bullied/bullying measures, the R2 associated with ADHD symptoms was still between 3 and 4%. This result affirms the merit in screening for ADHD symptoms in addition to assessing existing peer problems, to predict problems that students may confront in the longer-term.

3.2. Research Question 2: ADHD Symptomatology and Long-Term Wellbeing

The second research question posed was,

Are young people with ADHD symptoms more likely to fare poorly in the longer term in terms of their mental health, as measured by levels of general wellbeing, depression, and worry (amount and frequency)? Again, to address this question controlling for age, hierarchical MRAs were performed with age and SDQ ADHD scores from Timepoint 1 as independent variables (respectively), and the four measures of mental health completed at Timepoint 3 (the SWEMWBS, the CDI-2, the PAWS worry frequency and the PAWS worry amount items) entered as dependent variables. Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for all variables in the MRAs are shown in

Table 3, with outcomes of the MRAs shown in

Table 4.

As indicated in

Table 4, ADHD symptoms made a significant contribution to predicting all four of the mental health subscale scores over and above the contribution made by age. The

R2 for each of these was sizeable, ranging from .05 through to .13 (5-13% variance accounted for by ADHD symptoms). The largest

R2 was seen in the prediction of CDI-2 scores. Given the extended time period between Timepoint 1 and Timepoint 3, this suggests that ADHD symptoms have an enduring effect on key mental health outcomes in young people, contributing in the longer term to some 13% of score variance in depression scores, and 8% to overall wellbeing levels. This makes it clear that even when a formal diagnosis has not been delivered, exhibiting elevated levels of ADHD symptoms poses a significant risk to sound mental health and wellbeing in the longer term.

3.3. Research Question 3. Peer Relationships as Mediators of Links between ADHD Symptomatology and Long-Term Wellbeing

The third research question posed was,

Are any observed relationships between ADHD symptoms and long-term mental health significantly mediated by peer relationships (school belongingness; bullying; and friendships)? The goal of this analysis was to identify which of the peer relationship variables was most important in mediating relationships between ADHD symptoms and long-term mental health variables, to assist practitioners in setting meaningful intervention targets to interrupt long-term negative effects of ADHD symptoms on mental health. To address this question, an effect decomposition via path analysis was performed, in which ADHD symptomatology was the sole exogenous variable. In the second panel of the path analysis were the peer relationship (hypothesized mediating) variables, while the third panel included the four Timepoint 3 mental health measures. Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for all variables in the path analysis are shown in

Table 5, with outcomes of the path analysis shown in

Table 6.

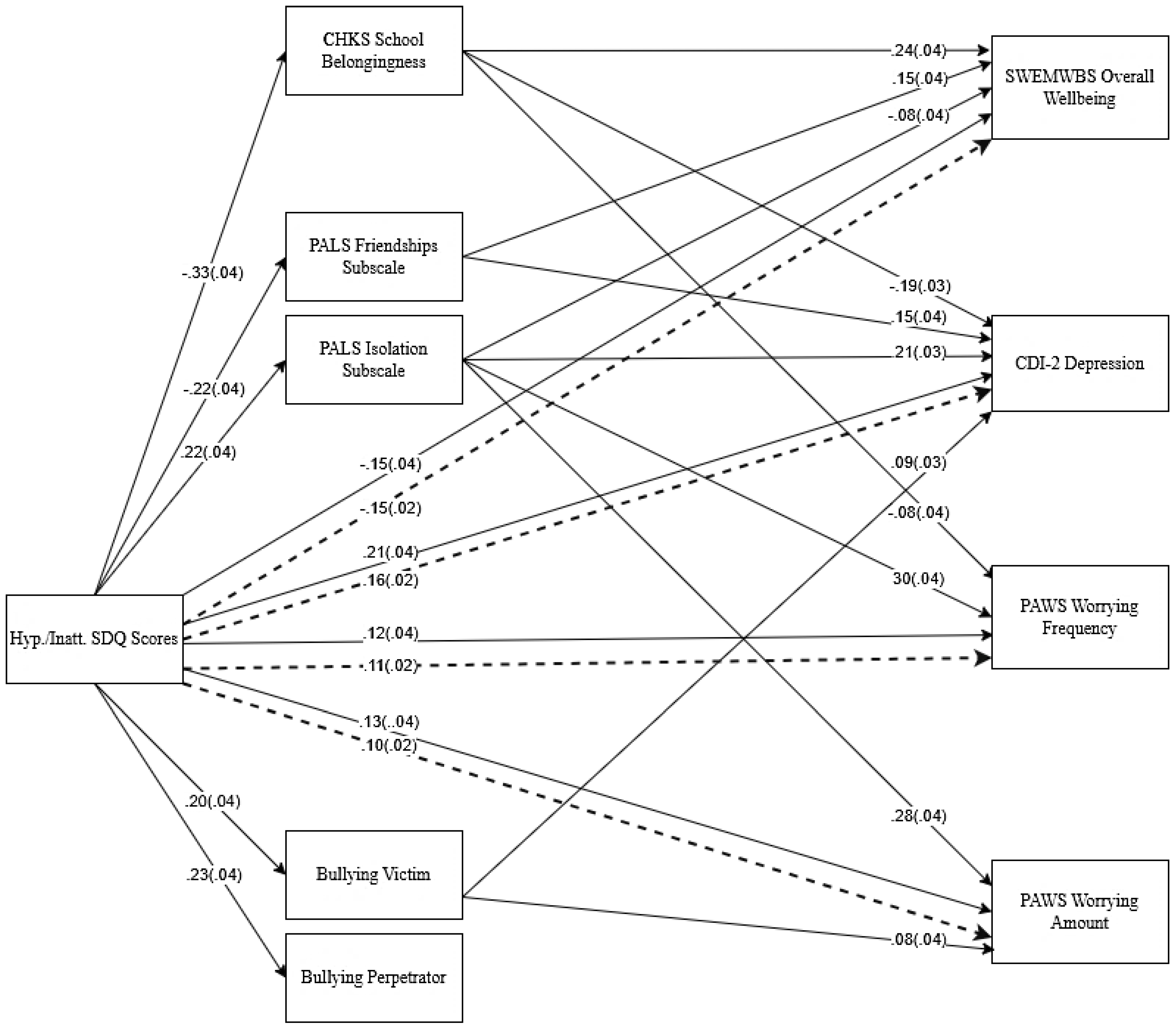

Figure 1 also shows all significant direct and indirect path coefficients generated within the model.

As indicated, ADHD symptoms had significant direct and indirect effects on all four mental health variables. For Wellbeing, the Direct Effect of ADHD symptoms was negative and significant, -.29(.04)*, with the Indirect Effect also significant and negative, -.15(.02)*. In contrast, the effect of ADHD symptoms on the remaining three variables was positive and significant, for Depression (DE = +.36; IE= +.16); Worry Frequency (DE = +.23; IE = +.11) and Worry Amount (DE = +.23; IE = +.11). Interestingly, the primary indirect effects were not mediated significantly by the bullying variables, but more through the Belonging, Friendships, and Isolation peer relationship variables. Specifically, over half (50%) of the indirect effects of ADHD symptoms on the mental health outcome variables could be attributed to only one or two of the peer relationship variables - for Wellbeing, to the Belonging and Friendship variables; for Depression, to the Belonging and Isolation variables; and for Worry Frequency and Amount, to the Isolation variable.

4. Discussion

Outcomes of the present study affirmed that young people with ADHD symptoms are at increased risk of exhibiting adverse mental health outcomes in the longer term, which can be attributed in part to the impact of ADHD symptoms on peer relationships. Given that participants were not necessarily formally diagnosed with ADHD, the results also underscore the need for increased awareness of the potential implications of sub-clinical forms of ADHD for longer-term mental health. In other words, the results suggest that even in the absence of a formal ADHD diagnosis, adolescents exhibiting ADHD symptoms may still confront significant impairments in relation to these symptoms.

The results of the present study relating to Research Question 1 (Are young people with ADHD symptoms more likely to report known risk factors in terms of peer relationships than those without such symptoms over the longer term?) indicated that ADHD symptoms made a significant unique contribution to predicting all five of the peer relationship variables at Timepoint 1. The unique contribution made by ADHD symptomatology was further affirmed in the second set of MRAs, which incorporated as predictors the SDQ Peer Problems scores. ADHD symptoms continued to make a statistically significant unique contribution to predicting peer problems over and above that predicted both by age and by peer problems, affirming that even in the absence of a formal diagnosis, exhibiting elevated levels of ADHD symptoms poses a significant long-term risk factor for peer relationship difficulties.

In terms of Research Question 2 (Are young people with ADHD symptoms more likely to fare poorly in the longer term in terms of their mental health, as measured by general wellbeing, depression, worry – frequency and amount?), ADHD symptoms made a significant unique contribution to predicting all four of the mental health and wellbeing subscale scores over and above the predictive contribution made by age. The effect sizes were substantial, suggesting that between 5 and 13% of the total variance across the four subscales could be accounted for by ADHD symptoms. Considering the extended time period between Timepoint 1 and Timepoint 3, this result affirms that ADHD symptomatology is likely to have an enduring effect on key mental health outcomes in young people, contributing in the longer term to some 13% of score variance in depression scores, and 8% to overall wellbeing levels. This makes clear that even when a formal diagnosis has not been delivered, exhibiting elevated levels of ADHD symptoms poses a significant long-term risk factor for mental health and wellbeing.

With respect to Research Question 3 (Are any observed relationships between ADHD symptoms and long-term mental health significantly mediated by peer relationships?), the focus was on identifying which of the peer relationship variables appeared to be most important in mediating the relationships between ADHD symptoms and the mental health variables. The path analysis performed to address this question indicated that ADHD symptoms had significant direct and indirect effects on all four of the mental health variables. For Wellbeing, the direct and indirect effects of ADHD symptoms were negative and significant, while for Depression, Worry Frequency and Worry Amount, the direct and indirect effects were all significant, but positive. The primary mediators associated with the significant indirect effects were the Belonging, Friendships and Isolation variables. This highlights both the importance of recognizing long-term relationships between ADHD symptoms and mental health, and also, the possibility of intervening upon these relationships, via the latter peer relationship variables.

While no previous studies could be located by the authors that addressed the specific questions addressed in the present study, the pattern of results aligns broadly with previous literature in the field. This previous literature suggests that around half of all young people with mental disorders continue to have difficulties in adulthood [

4]. The same body of literature has indicated that even those who go on to no longer have a diagnosable disorder as adults have a reduced chance of functioning effectively in comparison with those with no history of a mental disorder [

4]. Previous longitudinal findings, which reported on the longer-term trajectories for mental health in young people, have affirmed adolescence as a period in which individuals are at particular risk of experiencing loneliness [

28]. Loneliness, in turn, is a significant predictor of future depression, self-harm and suicidal ideation [

28].

The results also align with previous findings related to the critical role played by effective social interaction skills in long-term mental health outcomes [

14]. With specific reference to young people with ADHD, Lawrence et al.’s report on the Young Minds Matter survey indicated that some 60% of children and adolescents (4-17 year-olds) with ADHD reported problems with peer friendships [

10]. In particular, 24.9% of those surveyed reported these problems to be ‘mild’ in severity, while a further 23.6% reported these problems to be ‘moderate’. Most alarmingly, 10.6% of children and adolescents surveyed reported having ‘severe’ problems in the area of peer relationships, and with respect to friendships.

The relatively minimal contribution to mediation made by the two bullying variables was somewhat surprising. This could be attributed to the fact that schools in Australia, including Western Australia, have accelerated their efforts to address problems with bullying over the last decade. For example, the Western Australian Department of Education now requires every public school to have an anti-bullying plan and steps in place to deal with all forms of bullying. Schools, parents, and children can also access a range of resources through the national Bullying No Way website [

37], which is underpinned by significant federal and state funding. Bullying, therefore, may not have the same degree of impact on young people in Western Australia that it has had historically. In some respects, this was a positive finding of the study.

With respect to some of the additional challenges that are likely to be confronted by students with ADHD symptoms in schools, Owens et al. [

38] indicated that peer dynamics are clearly related to academic performance. Specifically, positive peer dynamics create a social context in the classroom that may foster the growth of academic ‘enablers’. Being poorly regarded by classroom peers, may thus interfere with the development of important academic enablers in young people with ADHD symptoms. Therefore, developing classroom strategies that operate to support the development of positive peer relations, such as co-operative groupwork approaches and collaborative projects, may carry significant benefits for students with ADHD symptoms. The added advantage of such approaches is that these represent sustainable strategies that are more likely to produce the kind of durable behavior change that is needed to address peer problems definitively.

There would also be merit to screening for ADHD symptoms in addition to existing peer relationship problems as a long-term predictor of challenges. As noted, the primary mediators of the significant indirect effects seen in the present study were the Belonging, Friendships, and Isolation variables. This highlights both the importance of recognizing long-term relationships between ADHD symptoms and mental health, and also, the need to isolate key mechanisms by which these relationships operate. Knowledge of these mechanisms would better equip schools to recognize how the adverse mental health outcomes of such students are developing over time, and thus, to interrupt these relationships by focusing on what matters in terms of longer-term mental health outcomes.

Future research could explore in more depth the importance of friendship

quality in mediating the relationships between ADHD and long-term mental health outcomes. Powell et al. [

39] found that ADHD and symptoms of depression “were associated directly and indirectly via friendship quality, both for best friend and top three friends” (p.1035) [

39]. Thus, there is evidence that close, reciprocal friendships and a strong sense of belonging are protective factors against mental health problems. Also given the evidence that children with ADHD symptoms have few close friends, with some reporting no reciprocated friendships at all [

25,

40], delving further into the importance of friendship quality and how this can be fostered in children with ADHD symptomatology may be a fruitful direction for future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M, S.H., E.C.; methodology, C.M, S.H., E.C.; validation, C.M, S.H., E.C.; data curation, S.H.; formal analysis, C.M., E.C.; visualization, C.M, E.C.; Writing – original draft, C.M., E.C.; Writing – review and editing, C.M, S.H., E.C.; supervision, E.C., S.H.; project administration, C.M, S.H., E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a University of Western Australia International Fee Scholarship and a University of Western Australia Postgraduate Award.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee, and approved by the University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee and the Department of Education Western Australia (Approval Ref: 2023/ET000730, Approved 22/08/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical issues.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- McLaughlin, S., Staniland L., Egan S. J., Wheadon, J., Munro, C., Preece, D., Furlong, Y., Mavaddat, N., Thompson, A., Robinson, S., Chen, W., Myers, B. Interventions to reduce wait times for adolescents seeking mental health services: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2023, 13, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/ bmjopen-2023-073438.

- McGrath J.J., Al-Hamzawi, A., Alonso, J., Altwaijri, Y., Andrade, L.H., Bromet, E.J., Bruffaerts, R., de Almeida, J.M.C., Chardoul, S., Chiu, W.T., Degenhardt, L., Demler, O.V., Ferry, F., Gureje, O., Haro, J.M., Karam, E.G., Karam, G., Khaled, S.M., Kovess-Masfety, V., Magno, M., Medina-Mora, M.E., Moskalewicz, J., Navarro-Mateu, F., Nishi, D., Plana-Ripoll, O., Posada-Villa, J., Rapsey, C., Sampson, N.A., Stagnaro, J.C., Stein, D.J., Ten Have, M., Torres, Y., Vladescu, C., Woodruff, P.W., Zarkov, Z., Kessler, R.C.; WHO World Mental Health Survey Collaborators. Age of onset and cumulative risk of mental disorders: A cross-national analysis of population surveys from 29 countries. Lancet Psychiatry 2023, 10, 668–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S2215-0366(23)00193-1.

- Erskine, H. E., Moffitt, T. E., Copeland, W. E., Costello, E. J., Ferrari, A. J., Patton, G., L. Degenhardt, L., Vos, T., Whiteford, H. A., Scott, J.G. A heavy burden on young minds: The global burden of mental and substance use disorders in children and youth. Psychological Medicine 2015, 45, 1551–1563. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714002888.

- National Mental Health Commission. National children’s mental health and wellbeing strategy 2021. https://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/projects/childrens-strategy.

- Rapee, R. M., Oar, E. L., Johnco, C. J., Forbes, M. K., Fardouly, J., Magson, N. R., Richardson, C. E. Adolescent development and risk for the onset of social-emotional disorders: A review and conceptual model. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2019, 123, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2019.103501.

- Velő, S., Keresztény, Á., Ferenczi-Dallos, G., Pump, L., Móra, K., Balázs, J. The association between prosocial behaviour and peer relationships with comorbid externalizing disorders and quality of life in treatment-naïve children and adolescents with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Brain Sciences 2021, 11, 475, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11040475.

- Pfeifer, J. H. & Allen, N. B. Puberty initiates cascading relationships between neurodevelopmental, social, and internalizing processes across adolescence. Biological Psychiatry 2021, 89, 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.09.002.

- Taylor, M. & Houghton, S. Difficulties in initiating and sustaining peer friendships: perspectives on students diagnosed with AD/HD. British Journal of Special Education 2008, 35, 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8578.2008.00398.x.

- Ter-Stepanian, M., Martin-Storey, A., Bizier-Lacroix, R., Déry, M., Lemelin, J.-P., Temcheff, C. E. Trajectories of verbal and physical peer victimization among children with comorbid oppositional defiant problems, conduct problems and hyperactive-attention problems. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 2019, 50, 1037–1048. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-019-00903-7.

- Lawrence, D., Johnson, S., Hafekost, J., Boterhoven De Haan, K., Sawyer, M., Ainley, J., Zubrick, S. R. The mental health of children and adolescents: Report on the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing [Young Minds Matter] 2015. Australian Department of Health.

- Sawyer, M. G., Reece, C. E., Sawyer, A. C. P., Johnson, S. E., Lawrence, D. Has the prevalence of child and adolescent mental disorders in Australia changed between 1998 and 2013 to 2014. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2018, 57, 343–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.02.012.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, Fifth Edition; 2013. https://dsm.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787.x01_Neurodevelopmental_Disorders.

- Furlong, Y. & Chen, W. Ch30: Child and adolescent neuropsychiatry. In Agrawal, N., Faruqui, R., Bodani, M. (Eds.), Oxford textbook of neuropsychiatry (pp.359-378). Oxford University Press, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780198757139.003.0030.

- Houghton, S., Lawrence, D., Hunter, S. C. , Zadow, C., Kyron, M., Paterson, R., Carroll, A., Christie, R., Brandtman, M. Loneliness accounts for the association between diagnosed Attention Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder and symptoms of depression among adolescents. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 2020, 42, 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-020-09791.

- Faraone, S.V., Banaschewski, T., Coghill, D., Zheng, Y., Biederman, J., Bellgrove, M.A., Newcorn, J.H., Gignac, M., Al Saud, N.M., Manor, I., Rohde, L.A., Yang, L., Cortese, S., Almagor, D., Stein, M.A., Albatti, T.H., Aljoudi, H.F., Alqahtani, M.M.J., Asherson, P., Atwoli, L., Bölte, S., Buitelaar, J.K., Crunelle, C.L., Daley, D., Dalsgaard, S., Döpfner, M., Espinet, S., Fitzgerald, M., Franke, B., Gerlach, M., Haavik, J., Hartman, C.A., Hartung, C.M., Hinshaw, S.P., Hoekstra, P.J., Hollis, C., Kollins, S.H., Kooij, J.J., Kuntsi, J., Larsson, H., Li, T., Liu, J., Merzon, E., Mattingly, G., Mattos, P., McCarthy, S., Mikami, A.Y., Molina, B.S.G., Nigg, J.T., Purper-Ouakil, D., Omigbodun, O.O., Polanczyk, G.V., Pollak, Y., Poulton, A.S., Rajkumar, R.P., Reding, A., Reif, A., Rubia, K., Rucklidge, J., Romanos, M., Ramos-Quiroga, J.A., Schellekens, A., Scheres, A., Schoeman, R., Schweitzer, J.B., Shah, H., Solanto, M.V., Sonuga-Barke, E., Soutullo, C., Steinhausen, H.C., Swanson, J.M., Thapar, A., Tripp, G., van de Glind, G., van den Brink, W., Van der Oord, S., Venter, A., Vitiello, B., Walitza, S., Wang, Y. The World Federation of ADHD international consensus statement: 208 evidence-based conclusions about the disorder. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 2021, 128, 789–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.01.022.

- Gardner, D. M. & Gerdes, A. C. A review of peer relationships and friendships in youth with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders 2015, 19, 844–855. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054713501552.

- Hoza, B., Mrug, S., Gerdes, A. C., Hinshaw, S. P., Bukowski, W. M., et al. What aspects of peer relationships are impaired in children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2005, 73, 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.411.

- Kok, F. M., Groen, Y., Fuermaier, A. B. M., Tucha, O. Problematic peer functioning in girls with ADHD: A systematic literature review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0165119.

- McQuade, J. D., Breslend, N. L., and Groff, D. Experiences of physical and relational victimization in children with ADHD: The role of social problems and aggression. Aggressive Behavior 2018, 44, 416–425. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21762.

- Factor, P. I., Rosen, P. J., Reyes, R. A. The relation of poor emotional awareness and externalizing behavior among children with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders 2016, 20, 168–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054713494005.

- Becker, S. P, Luebbe, A. M., Langberg, J. M. Co-occurring mental health problems and peer functioning among youth with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A review and recommendations for future research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 2012, 15, 279–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-012-0122-y.

- Bacchini, D., Affuso, G., Trotta, T. Temperament, ADHD and peer relations among schoolchildren: The mediating role of school bullying. Aggressive Behavior 2008, 34, 447–459. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20271.

- Wiener, J. & Mak, M. Peer victimization in children with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Psychology in the Schools 2008, 46, 116–131. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20358.

- He, J.P., Burstein, M., Schmitz, A., Merikangas, K. R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): the factor structure and scale validation in U.S. adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2013, 41, 583–595. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9696-6.

- Mikami, A. Y. & Normand, S. The importance of social contextual factors in peer relationships of children with ADHD. Current Developmental Disorders Reports 2015, 2, 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40474-014-0036-0.

- MySchool. Guide to understanding the Index of Community Socio-educational Advantage (ICSEA), 2020. https://www.myschool.edu.au/media/1820/guide-to-understanding-icsea-values.pdf.

- Goodman, R., Meltzer, H., Bailey, V. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1998, 7, 125–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s007870050057. ISSN 1018-8827.

- Houghton, S., Hattie, J., Wood, L., Carroll, A., Martin, K., Tan, C. Conceptualising loneliness in adolescents: Development and validation of a self-report instrument. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 2014, 45, 604–616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-013-0429-z.

- Houghton, S., Hattie, J., Carroll, A., Wood, L., Baffour, B. It hurts to be lonely! Loneliness and positive mental wellbeing in Australian rural and urban adolescents. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools 2016, 26, 52–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2016.1.

- Houghton, S., Kyron, M., Hunter, S. C., Lawrence, D., Hattie, J., Carroll, A., Zadow, C. Adolescents' longitudinal trajectories of mental health and loneliness: The impact of COVID-19 school closures. Journal of Adolescence 2022, 94, 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1002/jad.12017.

- Resnick, M.D., Bearman, P.S., Blum, R., Bauman, K.E., Harris, K.M., Jones, J., Tabor, J., Beuhring, T., Sieving, R.E., Shew, M., Ireland, M., Bearinger, L.H., Udry, J. Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the national longitudinal study on adolescent health. JAMA 1997, 278, 823–832. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1997.03550100049038.

- Mahecha, J. & Hanson, T. California School Climate, Health, and Learning Surveys, 2020. California Department of Education’s School Health and Safety Office.

- McKay, M. T. & Andretta, J. R. Evidence for the psychometric validity, internal consistency and measurement invariance of Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale scores in Scottish and Irish adolescents. Psychiatry Research 2017, 255, 382–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.06.071.

- Taggart, F., Stewart-Brown, S., Parkinson, J. Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS), 2016. NHS Scotland. https://s3.amazonaws.com/helpscout.net/docs/assets/5f97128852faff0016af3a34/attachments/5fe10a9eb624c71b7985b8f3/WEMWBS-Scale.pdf.

- Masip, A. F., Amador-Campos, J. A., Gómez-Benito, J. & Gándara, V. del Barrio. Psychometric properties of the Children’s Depression Inventory in community and clinical sample. The Spanish Journal of Psychology 2010, 13, 990–999. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1138741600002638.

- Hunter, S. C., Houghton, S., Kyron, M., Lawrence, D., Page, A. C., Chen, W. C, Macqueen, L. Development of the Perth Adolescent Worry Scale (PAWS). Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology 2022, 50, 521–535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-021-00853-6.

- Australian Education Authorities. Bullying No Way website, 2024. https://bullyingnoway.gov.au/.

- Owens, J. S., Qi, H., Himawan, L. K., Lee, M., Mikami, A. Y. Teacher practices, peer dynamics, and academic enablers: A pilot study exploring direct and indirect effects among children at risk for ADHD and their classmates. Frontiers in Education 2021, 5, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.609451.

- Powell, V., Riglin, L., Ng-Knight, T., Frederickson, N., Woolf, K., McManus, C., Collishaw, S., Shelton, K., Thapar, A., Rice, F. Investigating friendship difficulties in the pathway from ADHD to depressive symptoms. Can parent–child relationships compensate? Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology 2021, 49, 1031–1041. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-021-00798-w.

- Simmons, J. A.; Antshel, K. M. Bullying and depression in youth with ADHD: A systematic review. Child & Youth Care Forum 2021, 50, 379–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-020-09586-x.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).