1. Introduction

In the workplace, ideal supervisors are widely recognized by both subordinates and organizational scholars as those who demonstrate a dedication to their responsibilities without compromising their own or others’ personal well-being [

1]. Nevertheless, some supervisors are excessively involved in work and may even feel compelled to work. These supervisors are regarded as workaholics. Compared with regular subordinates, supervisors face numerous challenges and are more inclined to invest additional time and energy in work, albeit sometimes at the expense of their rest and family life. As such, supervisor workaholism is fairly prominent [

2]. While workaholism is intuitively regarded as an admirable work ethic, such as the Protestant work ethic [

3], and even endorsed within organizational culture [

4], existing research findings on its effects are inconclusive. On one hand, supervisor workaholism may have negative spillover effects on subordinate well-being [

2]. On the other hand, it may, in certain circumstances, enhance employee investment in work [

5]. Therefore, a more comprehensive understanding of supervisor workaholism is urgently needed. Insufficient comprehension of its impact on subordinates could lead to the misconception that being a workaholic improves subordinate job performance in management practice.

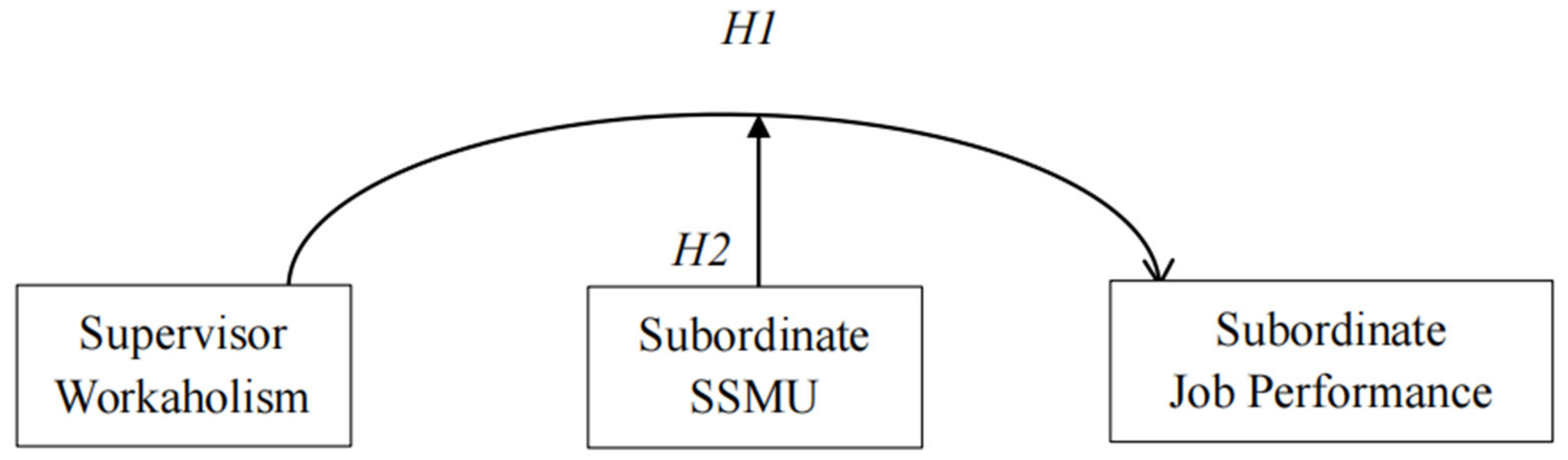

Drawing on the principle learning perspective and activation theory, we suggest a curvilinear, rather than a linear, relationship between supervisor workaholism and subordinate job performance, and we examine this relationship under a boundary condition. We posit that as supervisor workaholism increases from low to moderate levels, subordinates can more formulate behavioral principles toward devotion to work and hence improve their job performance. However, as supervisor workaholism increases from moderate to high levels, learning turns into physical and mental strain, resulting in diminished subordinate job performance. As such, moderate supervisor workaholism should lead to the highest subordinate job performance.

In addition, we leverage insights from social learning theory to explore an important and relevant moderating role of employees’ social-related social media use (SSMU) in the proposed curvilinear relationship. Our focus on SSMU stems from its ability to facilitate employees’ access to a broader spectrum of social learning information [

6,

7], thereby shaping the principle learning process from workaholic supervisors. Specifically, we propose that when supervisor workaholism is moderate to high, subordinate SSMU helps subordinates realize the detrimental effects of imitating the supervisor’s excessive work behavior due to accessing diverse social information. When supervisor workaholism is low to moderate, subordinate SSMU facilitates subordinate work-related learning from broader information sources, which results in enhanced performance. The logic can be found in our theory and hypothesis section.

Figure 1 depicts our proposed theoretical model.

Our work makes at least two major contributions to the literature. First, we combine the principle learning perspective with activation theory to develop a new framework for understanding the impact of supervisor workaholism on subordinate job performance. While previous scholars held contradictory views on the influence of workaholic supervisors on subordinates, we move beyond linear thinking and propose that there exists an optimal level of supervisor workaholism that maximizes subordinate job performance. Given the prevalent workplace norms that encourage dedication and overwork, which may value such workaholic tendencies [

8,

9], our approach emphasizes the need for scholars and practitioners to fully comprehend the influence of workaholic supervisors.

Second, prior research has highlighted the potential downsides of social media at work that contradict work ethics (e.g., cyberloafing and time theft) [

10,

11,

12]. However, this perspective only presents a partial view. Our study introduces a fresh approach based on social learning theory to address the beneficial aspects of using social media at work, as it allows employees to resist the pressure to mimic their workaholic supervisors. By focusing on the functional role of SSMU, our research complements existing studies by demonstrating its potential to enhance employee well-being and job performance. In this way, we respond to calls for investigating technology use in the workplace by examining how SSMU influences leadership dynamics [

13,

14,

15].

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Supervisor Workaholism

Workaholism denotes an addiction to excessive work involvement [

16]. This state is characterized by compulsive and excessive work behavior [

17]. Workaholics are characterized by their constant preoccupation with work and their tendency to exceed organizational expectations in their commitment to work [

18]. Although dedication to work and diligence are integral aspects of work ethics and modern work norms [

19,

20], workaholism reflects extreme engagement and an internal compulsion toward work, potentially leading to a range of negative outcomes for employees. Prior research has shown that workaholism is associated with heightened work pressure [

21], work-induced fatigue [

22], diminished levels of life satisfaction [

23], and decreased spousal marital contentment [

24], whereas only a handful of studies have focused on the interpersonal influence of workaholic supervisors. For instance, Russo and Waters [

25] studied the negative spillover effect of workaholism on work-family conflict, and She et al. [

5] discussed the influence of workaholic CEOs on team work engagement. However, the influence of supervisor workaholism on subordinate job performance has received limited empirical investigation.

Exploring the impact of workaholic supervisors on subordinate job performance holds both practical and theoretical significance. On the one hand, workaholism emerges prominently among employees holding leadership responsibilities [

2]. However, the manifestation of workaholism among supervisors remains a topic of debate. A lack of comprehensive understanding of the influence of workaholic supervisors may lead people to either excessively praise or excessively reject workaholic supervisors. On the other hand, despite workaholism being assessed as a continuous variable, researchers often compare the influence between higher and lower levels of workaholism from a linear perspective [

5,

26]. However, Gillet et al. [

27] revealed that a substantial portion of individuals demonstrate an average level of workaholism (37.99% in the sample). This group tends to exhibit improved perceived health and lower stress levels compared to those with higher levels (49.10% in the sample) or lower levels of workaholism (4.96% in the sample). Hence, there may exist an optimal level of workaholism that can yield desirable outcomes.

Drawing on the principle learning perspective from social learning theory and insights from the activation theory, we propose that a moderate level of supervisor workaholism could have the most beneficial impact on subordinate job performance. In this research, we conceptualize supervisor workaholism as an individual-level phenomenon. Since supervisors cultivate various relationships with different subordinates, some subordinates may be more familiar with the supervisor’s work habits and cognitive disposition, influencing the way they perceive the supervisor's workaholic tendencies. Therefore, members within the same workgroup may hold distinct perceptions of their supervisor’s workaholic tendency. This viewpoint aligns with existing works regarding workaholism as an individual-level variable [

28,

29].

2.2. Supervisor Workaholism and Subordinate Job Performance: A Principle Learning Perspective

Social learning theory [

30] proposed the social modeling effect, suggesting that role models who hold power and high positions in social hierarchies, such as supervisors in an organizational context, are more likely to engender mimicking behavior among observers [

30]. Consistent with this reasoning, existing studies identify role-modeling effects of supervisors on subordinates [

31], and Afota et al. [

32] propose that subordinates could mimic the supervisor's working hours. However, in addition to producing the same behaviors, observers can abstract the principles exemplified in the behaviors of role models and use them to generate new behavioral norms [

30]. According to this principle learning perspective from social learning theory, we predict that subordinates of workaholic supervisors could abstract behavioral principles from observing their supervisor’s behavioral and cognitive tendency, which in turn will affect their job performance.

In the workplace, when subordinates observe workaholic supervisors exhibiting excessive working behavior, constant thinking about work, and compulsion to work, they may abstract common themes exemplified in supervisors’ behavioral and cognitive tendencies: Devoting to work beyond standard work requirements is expected. For instance, when subordinates notice their supervisors working long hours and constantly thinking about work, even during non-work hours, they may interpret this behavior as an encouragement to exceed typical performance standards and prioritize work as the central aspect of their life. Consequently, subordinates may adopt a principle of full devotion to their job and strive to work beyond established standards. For example, previous studies have shown that workaholic CEOs can promote the work engagement of their executive teams in organizations [

2]. Therefore, as the supervisor’s workaholic tendency increases, their subordinates are more likely to formulate and internalize a principle that excessively devoting to work.

To better understand the impact of workaholic supervisors, we further draw upon the tenets of activation theory. The activation theory posits that each individual possesses an 'activation level' that optimally stimulates the central nervous system. At this level, individuals efficiently mobilize their cognitive resources and exhibit optimal job performance [

33]. However, excessively high and excessively low activation levels can hinder individuals from achieving optimal performance outcomes. Factors such as job demands and work-related stress act as stimuli in the work context, influencing an individual's activation level [

34]. For instance, prior research demonstrated a curvilinear relationship between job demands and job performance [

35], while the impact of abusive management practices [

36] and time pressure on subordinate creativity also exhibits a similar curvilinear relationship [

37]. Combining the viewpoint of principle learning and activation theory, we suggest a potential curvilinear relationship between supervisor workaholism and subordinate job performance.

Specifically, workaholic supervisors could enhance subordinate job performance by motivating subordinates through a process of learning principles. Working with a workaholic supervisor, subordinates may formulate a principle of devotion to work, working beyond standard requirements, and regarding work as the central part of life. This principle reflects the behavioral norm of subordinates and constitutes a part of their job demands, serving as a stimulus that activates job performance. Supporting this stance, workaholic CEOs may push TMT members to actively engage in work by demonstrating excessive work behavior and setting high standards [

2]. Activation theory suggests that compared with a low activation level, a moderate level of stimulation increases individual performance [

33]. Therefore, as the level of supervisor workaholism increases, subordinates are increasingly motivated to devote themselves to work. Their activation level increases toward the optimal level accordingly, resulting in improved performance. As a result, subordinates working with workaholic supervisors tend to show enhanced job performance by aligning their behavioral and cognitive patterns with the principles learned from supervisors.

However, supervisor workaholism may not only fail to enhance but could also harm subordinate job performance when it reaches excessively high levels. Working with an extremely workaholic supervisor, subordinates may develop a principle of excessive work involvement. As proposed by activation theory, when work demands are extremely high, the activation level deviates from the optimal point, thus diminishing individual performance [

33]. Indeed, working excessively and being preoccupied with work-related issues, as well as overly emphasizing the importance of work, may lead to work overload [

21]. This can result in lower psychological detachment and lower satisfaction due to work-life conflict [

38]. Consequently, these detrimental psychological states, combined with insufficient personal resources, could hinder subordinate job performance. In support of this view, scholars proposed that workaholic supervisors may increase mental strain among subordinates [

2]. Overall, as a result of learning from workaholic supervisors, subordinate job performance may initially increase, but this positive effect can reverse when supervisor workaholism reaches excessive levels, leading to decreased job performance.

Hypothesis 1: Supervisor workaholism has an inverted U-shaped relationship with subordinate job performance, such that low to moderate levels of supervisor workaholism increase, but moderate to high levels of supervisor workaholism decrease, subordinate job performance.

2.3. Social-Related Social Media Usage as Contingency

Given the status of supervisors in the organization, learning principles from workaholic supervisors is an important social learning approach for subordinates, while not the only approach. Social learning theory posits that people have various sources of learning, such as learning from physical demonstrations provided by supervisors, and from symbolic models found in media platforms such as social media [

39].

Social media refers to computer-mediated communication tools that allow users from diverse communities to freely create, share, and exchange a wide range of information via the internet [

6]. Social-related social media usage (SSMU) denotes subordinates' use of social media to foster or form new social relationships and networks, facilitate social and personal information exchange, and provide social and emotional support within the organization [

40,

41]. Bandura and Walters [

35] proposed that media play an important role in the social learning process since people are exposed to the mass amount of information provided by newspapers, televisions, and films. Nowadays, social media has become an important platform where people demonstrate and share their behaviors and attitudes, akin to showcasing lifestyles [

42]. Thus, SSMU represents an alternative social learning approach for the subordinates of workaholic supervisors.

Social learning theory suggests that the attractiveness of a role model depends on their status in a specific social context and the desirability of the outcomes of their behaviors [

35]. SSMU provides diverse information by creating opportunities for subordinates to build and maintain social connections with a broader range of people beyond the workplace [

15,

43], while also blurring the boundary between work and non-work contexts [

44]. Despite supervisors may be role models with high status in the work context, in the mixed social environment created by SSMU, if subordinates do not appreciate the behavior and cognitive mode of workaholic supervisors, they will be more likely to disengage from social learning process, and therefore, their job performance will be less likely be affected by supervisor workaholism.

We propose that when the level of SSMU is high, the job performance of subordinates working with extreme workaholic supervisors will be less negatively affected. Firstly, compared to a lower level of SSMU, a higher level of SSMU means subordinates have broader access to information and more opportunities to learn from others beyond the workplace. Subordinates could be influenced by their friends who maintain a balanced work-life mode, as well as be attracted by others' diverse lifestyles beyond being fully devoted to their job through SSMU. Secondly, extreme workaholism often leads to negative outcomes for supervisors themselves, such as higher stress levels, less job satisfaction, more work-life conflicts, and burnout [

34]. As social learning theory proposes, if the exemplified behavior cannot generate desirable outcomes, the social learning process will be hindered [

35]. Observing these undesirable outcomes, subordinates may doubt learning from extreme workaholic supervisors. This effect would be more prevalent among subordinates who frequently use social media for social purposes, because they could frequently encounter a wide spectrum of negative emotions and reactions displayed by workaholic supervisors, while also being exposed to curated content and messages that may obscure the negative facets of other’s lives on social media. Consequently, subordinates with high levels of SSMU may perceive extreme workaholic supervisors as less appealing or even detrimental, given the visibility of negative outcomes associated with such tendencies. Taken together, for subordinates with a higher level of SSMU, they could be less likely to adopt the behavioral principle of excessively involving in work, thus their job performance would be influenced less by supervisor workaholism.

Similarly, we posit that high SSMU levels mitigate the negative impact of low-workaholic supervisors on subordinates' job performance. Supervisors with notably low workaholic tendencies may demonstrate minimal enthusiasm and dedication to work. In such cases, subordinates may not be fully motivated to exceed standard job expectations, thereby hindering their pursuit of enhanced job performance and personal growth. Therefore, supervisors with extremely low levels of workaholism are unlikely to be ideal role models. However, subordinates could benefit from expanded social learning facilitated by SSMU, which provides them with greater access to learn from others about how to perform better and work more efficiently. Supporting this view, social media use in the workplace has been proven to facilitate subordinates’ learning behaviors related to work [

45], enhance the communication of work-related knowledge and information [

46,

47,

48], and help subordinates improve job performance [

36]. Combing the low attractiveness of low workaholic supervisors as role models and the broader learning access provided by SSMU, subordinates could be less likely to learn principles about working from their supervisors, thus their job performance would be influenced less by supervisor workaholism.

In contrast, SSMU is less likely to influence the principle learning process for subordinates working with moderately workaholic supervisors. Previous studies have demonstrated that individuals with a moderate level of workaholism perceive higher health and lower stress [

27]. Moderately workaholic supervisors tend to maintain a moderate level of work and work-related preoccupation, which is conducive to improving job performance without creating excessive self-imposed pressure. Observing their supervisor benefit from a more balanced approach to work, subordinates are likely to regard supervisors as attractive role models, with SSMU unlikely to change this tendency.

Hypothesis 2: Subordinate SSMU moderates the inverted U-shaped relationship between supervisor workaholism and subordinate job performance, such that the inverted U-shaped relationship is less pronounced when subordinate SSMU is higher.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

To test our hypotheses, we recruited front-line subordinates and their corresponding middle managers (i.e., one subordinate paired with one direct supervisor) from six Chinese companies, with the assistance of an online research company specializing in business surveys. Previous research has validated collaborating with external research agencies as an effective method for recruiting participants [

49]. This partnership enabled access to a diverse participant pool, thereby enhancing the generalizability of the research results.

Per the advice of the market research agency, we collected supervisor-subordinate matched data via electronic questionnaires. Prior to distribution, the agency helped explain our research objectives to potential participants and provided lists of supervisor-subordinate dyads. Each dyad received a unique research ID and all participants were asked to fill in their research ID in questionnaires. Supervisors were informed of their corresponding subordinate’s name for performance rating purposes. Each supervisor’s questionnaire was matched with the corresponding subordinate’s response, forming paired supervisor-subordinate samples. These recruitment efforts resulted in 332 as the initial study sample.

To ensure the quality of data, all respondents were informed that the information obtained from the questionnaires was completely anonymous, strictly confidential, and used solely for scientific research purposes. We collected data over two measurement time points with a one-week time lag between each wave. At Time 1, subordinates were invited to report their social-related social media usage, and the corresponding supervisors were invited to evaluate their level of workaholism. In addition, all subordinates reported their length of employment, gender, and age as control variables. At Time 2, the supervisors evaluate their corresponding subordinates’ job performance. After matching supervisor-subordinate responses using the unique research ID and excluding 11 incomplete responses (where either the supervisor or subordinate failed to complete the questionnaire), the final sample consisted of 321 paired supervisor-subordinates. Among them, 49% were female (S.D. = 0.50). They were 34.92 years old on average (S.D. = 4.18 years) and had worked for 9.98 years (S.D. = 4.27 years) in their current organizations.

3.2. Measures

We asked supervisors to report their workaholism level as well as the job performance of their subordinates, and asked subordinates to report their use of social media for social purpose. The authors, fluent in both English and Chinese, translated the scales following recommended back-translation procedures when the Chinese version was unavailable. The first author translated the items into Chinese, and the two other authors translated them back into English. All the authors discussed together to resolve the differences to ensure conceptual clarity and equivalence.

Supervisor workaholism was measured with the 10-item workaholism scale [

17] to assess this variable. Sample items are: “I stay busy and keep many irons in the fire” and “it is difficult for me to relax when I stop working”. Responses were assessed on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Social-related social media usage was measured with the 4-item social-related social media usage scale [

46]. Subordinates rated their frequency of using social media for social purpose in daily life. Sample items include “I use social media to make friends within the organization”. Responses were assessed on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always).

Job performance was measured with the 7-item job performance scale developed by Williams and Anderson [

50]. Sample items include “he/she performs tasks that are expected of him/her”. Responses were assessed on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

We controlled subordinate tenure in current organization, gender, and age as they have been found to be related to job performance [

35].

4. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Descriptive statistics, bivariate correlations, and Cronbach’s alphas are displayed in

Table 1. The results showed that the relationship between supervisor workaholism and subordinate job performance was not significant (r = 0.01, n.s.), suggesting possible curvilinear effects.

To examine whether the three variables reflect distinct factors, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis using Mplus. We first specified a three-factor model and set the items loading on their corresponding latent factors. Then, we compared with other models in which items were allowed to load on other latent factors. The results suggest that the expected three-factor model best fits our data (χ2 = 362.69, df = 186, CFI = .95, SRMR = .04, RMSEA = .05). Other alternative models were significantly worse than the three-factor model (see

Table 2).

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

4.1.1. The Inverted U-Shaped Relationship between Supervisor Workaholism and Subordinate Job Performance

Hypotheses were tested using hierarchical regression analyses in SPSS 22.0. Following the common practice [

51], we included the predictors sequentially in the regression equation to predict subordinate job performance: (a) control variables, (b) supervisor workaholism, (c) the squared supervisor workaholism, (d) SSMU, the linear interaction between supervisor workaholism and SSMU, and the interaction between squared supervisor workaholism and SSMU. Supervisor workaholism and SSMU were mean-centered to facilitate interpretability and mitigate multicollinearity [

52].

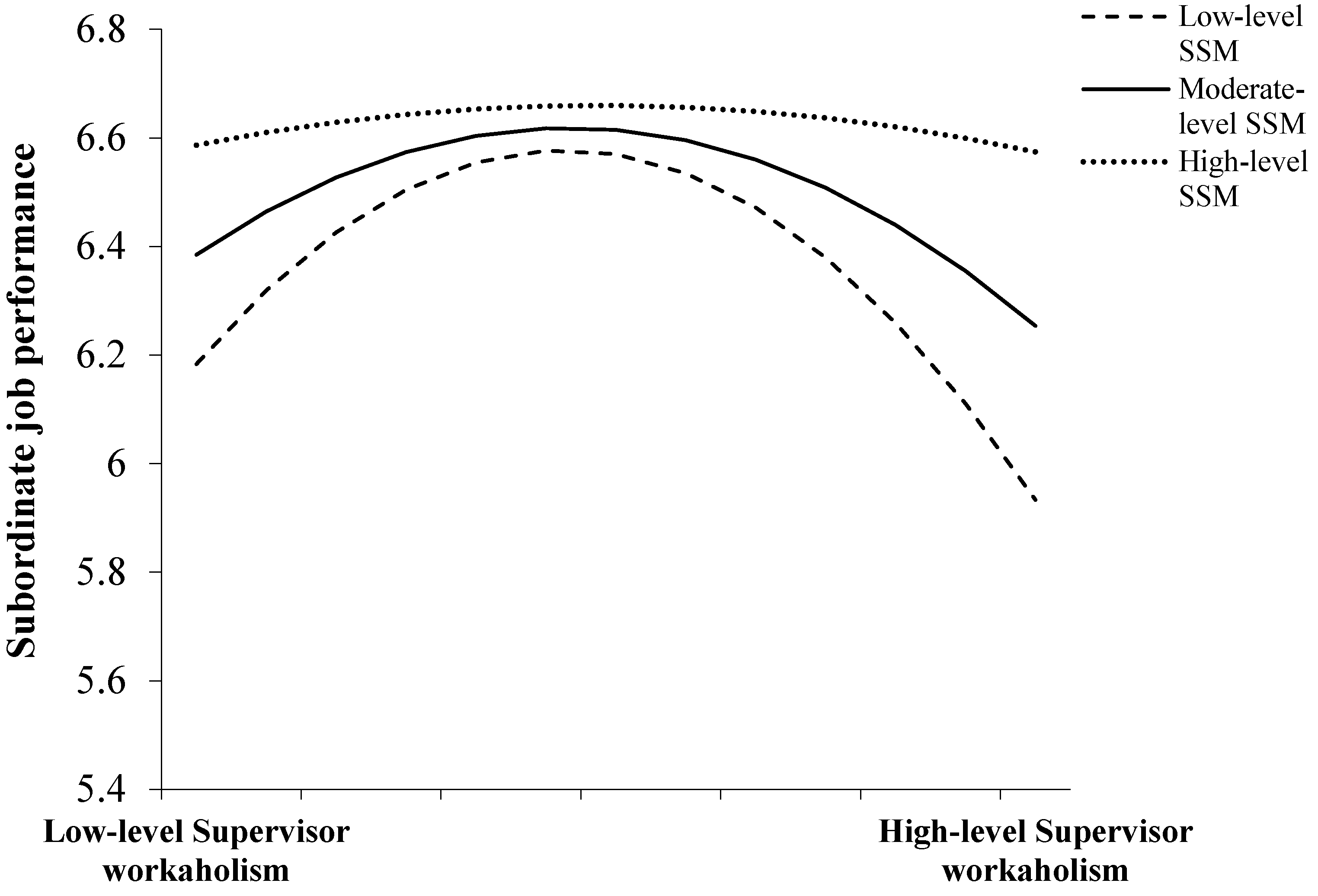

Hypothesis 1 predicted that supervisor workaholism has a curvilinear effect on subordinate job performance. To examine this effect, we began with comparing a baseline model including all controls and a linear effects model including supervisor workaholism. As shown in

Table 3, step 2, the linear effect of supervisor workaholism on subordinate job performance was non-significant (β = 0.001, SE = 0.05, ΔR² = 0.00, n.s.). However, the coefficient of the quadratic term of supervisor workaholism was negative and significant (β = –0.12, p < 0.01, ΔR² = 0.03;

Table 3 step 3), thus supporting for an inverted U-shaped relation between supervisor workaholism and subordinate job performance. We plotted this relationship in

Figure 2 based on Cohen et al.’s procedure [

53]. As depicted, the relationship between perceived supervisor workaholism and subordinate job performance showed an upward trend at lower levels of supervisor workaholism and a downward trend at higher levels of supervisor workaholism. We calculated the inflection point following Aiken et al.’s approach [

54]. The results revealed that the inflection point of supervisor workaholism was 4.04 on the seven-point scale. If a supervisor’s workaholism score fell below 4.04, there was an upward trend in their relationship with subordinate job performance. However, when a supervisor’s workaholism score exceeded 4.04, this trend turned downward. Taken together, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

4.1.2. The Moderating Effect of SSMU

Hypothesis 2 predicted that subordinate SSMU moderates the relationship between supervisor workaholism and subordinate job performance such that the inverted U-shaped relationship is more pronounced for subordinates with lower levels (vs. higher level) of SSMU. To test this hypothesis, we added the interaction terms between SSMU and supervisor workaholism, and between SSMU and supervisor workaholism-squared, into the hierarchical regression analyses.

Step 4 in

Table 3 showed the linear and quadratic two-way interactions with supervisor workaholism-squared and subordinate SSMU. The results indicated that the interaction between supervisor workaholism-squared and SSMU was positively related to subordinate job performance (β = 0.09, p < 0.05, ΔR² = 0.04;

Table 3 step 4). We plotted this interactive effect in

Figure 2. As the upper curve in

Figure 2 shows, the inverted U-shaped relation between supervisor workaholism and subordinate job performance became flattened as the level of subordinate SSMU increased. Conversely, as the lower curve in

Figure 2 demonstrates, the inverted U-shaped curve became sharpened as the level of subordinate SSMU decreased. This is consistent with our prediction: the inverted U-shaped relation between supervisor workaholism and subordinate job performance was less pronounced for employees with higher levels of SSMU. Hence, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

5. Discussion

The major objective of this study was to gain a better understanding of the influence of supervisor workaholism on the subordinate performance. Consistent with our hypotheses, subordinates exposed to intermediate levels of supervisor workaholism showed a higher likelihood of displaying higher levels of job performance. Notably, the negative effects of extremely high or low levels of supervisor workaholism were weaker when subordinates embraced high, rather than low, levels of SSMU. Below, we discuss the implications of these findings for research and practice.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Our findings hold significant implications for research regarding the impact of supervisor workaholism. Although extensive research has examined the negative impact of workaholism on employees [

38] and its interaction with technology-induced stress [

14], we have limited understanding of its interpersonal influence within supervisor-subordinate relationships and how workplace technology use may impact the effects of supervisor workaholism. Our research was inspired by the recent work suggesting that a moderate level of workaholism may yield desirable outcomes [

27] and represent the direct examinations of the influence of workaholic supervisors on subordinate job performance. While previous research suggested that workaholic supervisors may have positive effects on subordinates [

5,

26], our study demonstrated that the relationship between supervisor workaholism and subordinate job performance is more complex.

First, we found that subordinates under moderately workaholic supervisors tend to outperform those under supervisors with low levels of workaholism. This finding can be elucidated through the principle learning process between supervisors and subordinates. Subordinates led by supervisors with a moderate level of workaholism are more likely to grasp and adopt principles of exceeding typical standards of engagement in work and considering work as a vital component of life. The principles absorbed from moderately workaholic supervisors act as a catalyst, stimulating optimal job performance among subordinates. This aligns with prior research indicating a trickle-down effect of leaders' work involvement on follower engagement [

55], along with evidence that moderate job demands are instrumental in maximizing employee job performance [

56,

57]. In contrast, supervisors with lower levels of workaholism typically rarely work beyond standard. In the worst-case scenario, supervisors exhibiting extremely low levels of workaholism may invest minimal effort in completing tasks, leading to subordinates lacking the motivation to engage in discretionary work efforts.

Furthermore, when supervisor workaholism increased from moderate to high, subordinate job performance was found to decrease. We attribute this decline in performance to the work overload induced by learning from extremely workaholic supervisors. As suggested by activation theory, the principle of excessive work involvement may impose significant pressure on subordinates’ resources, surpassing the “optimal point” and ceasing to enhance employee job performance. Although studies have revealed the potential for workaholic leaders to enhance team work engagement [

5] and also the risk of damaging employee job performance through work overload [

2,

58], our research provides a comprehensive view of the contradictory influences of supervisor workaholism. By integrating the principle learning perspective and activation theory, we revealed that moderate levels of supervisor workaholism provided the optimal stimulation for achieving optimal job performance. From a theoretical standpoint, this suggests that the activation generated by a moderate workload (as proposed by activation theory), induced by the principle learning process (as suggested by social learning theory), enables moderately workaholic supervisors to optimally stimulate subordinate job performance.

This article also made theoretical contributions to the research on social media usage in the workplace. Scholars have emphasized the importance of conducting research that captures the intertwined relationships between technology use behaviors and work systems [

13,

15]. By exploring the effect of technology use on the supervisor-subordinate dyadic relationship, this study responds to the call by shedding light on how SSMU could help subordinates mitigate the adverse effects of supervisor workaholism. Previous research about workplace social media usage predominantly adopts either a technology affordance perspective or a demands and resource perspective [

59]. We propose that SSMU, from a social learning perspective, could serve as an alternative social learning approach by introducing various social information into the workplace context. SSMU acts as a catalyst, preventing subordinates from learning from supervisors with undesirable characteristics, thus mitigating the negative influence of workaholic supervisors.

This article contributes to a deeper understanding of the bright side of SSMU. Many studies categorized SSMU, a type of social media usage unrelated to work content, as a form of counterproductive work behavior [

10] such as time theft [

55] and cyberloafing [

60,

61], suggesting that it contradicts work ethics to some extent. However, some scholars recognize that social media usage bridges leisure and work, thereby having positive implications for job performance [

6,

7]. Notably, Wang et al. [

15] discovered that the positive effect of SSMU was particularly strong for those who have higher level of workload, but not for those with lower level of workload. Our results echoed their findings by confirming that SSMU promoted productivity (as demonstrated by the positive correlation between SSMU and subordinate job performance in

Table 1) and was particularly beneficial for subordinates who faced overwhelming demands caused by workaholic supervisors. Furthermore, our study extends their findings by revealing that SSMU is also beneficial for under-stimulated subordinates by affording them access to a wider array of learning opportunities. Overall, our research results imply that SSMU has the potential to help subordinates alleviate adverse work conditions such as supervisor workaholism.

5.2. Managerial Implications

Our research also has several important implications for managerial practice. First, our findings suggest that supervisor workaholism initially enhances subordinate job performance within a certain range. Considering the prevalent belief that workaholism symbolizes a dedicated work ethic, organizations may focus on the positive effect of workaholic supervisors, believing they would stimulate their subordinates to achieve better performance. However, they might not be aware of the holistic consequences of supervisor workaholism. This performance-enhancing effect disappears and turns into a performance-decreasing effect once supervisor workaholism surpasses a certain threshold.

Second, the level of subordinate SSMU plays a crucial role. Subordinates with higher levels of SSMU use show resilience to the negative effects of supervisor workaholism, maintaining a higher level of performance regardless of the supervisor workaholism level. Conversely, subordinates with lower levels of SSMU are more susceptible to the negative impacts of supervisor workaholism, experiencing more pronounced performance declines once supervisor workaholism surpasses the threshold.

Therefore, organizations should be aware of the consequences of supervisor workaholism and strive to keep it within manageable limits. Additionally, organizations can leverage the social learning process by guiding subordinates to recognize the importance and benefits of maintaining a balanced level of work involvement. For subordinates, our research suggests that using social media can be an effective approach to facilitate work-related learning, build social capital, and ultimately increase productivity, especially when dealing with workaholic or demotivated supervisors.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

The present research has some limitations that provide opportunities for future research. First, we did not dive deeply into the internal process of social learning between workaholic supervisors and subordinates. We encourage future research to explore the mechanisms through which subordinate job performance is influenced by their workaholic supervisors within the context of organizational social learning.

Second, this research exclusively examined SSMU as a boundary condition. Future studies could identify additional boundary conditions beyond social media use that may moderate the effects of supervisor workaholism on employee performance. According to social learning theory, observers may not always be willing or able to translate social learning process into behavioral changes [

30]. For instance, subordinates who have lower identification with workaholic supervisors or lack the capability to change behavior to meet supervisor expectation may be less likely to alter their behavior in response to workaholic supervisors. Therefore, future research should establish a more nuanced understanding of the interaction among supervisor workaholism, subordinate personality, and the use of information technology.

Third, we used the Dutch Work Addiction Scale developed by Schaufeli et al. [

17] to measure workaholism via supervisor self-assessment, but this method has two limitations. On one hnd, while the scale has strong psychometric properties and test-retest reliability across cultural contexts, it has been criticized for focusing too narrowly on the behavioral and cognitive aspects of work addiction, neglecting the complexity and multidimensionality of workaholism [

18,

62]. On the other hand, as this study explores the interpersonal effects of workaholism, subordinate assessments of their supervisor’s workaholic tendencies could also be a valid approach. Unfortunately, there is currently a lack of peer-assessment scales for measuring workaholism. We hope future research will overcome these limitations.

Finally, our sample is from China, a country deeply influenced by Confucian culture, which emphasizes a strong work ethic. Past research reveals that Chinese employees exhibit relatively higher levels of workaholism [

4] due to valuing hard work, treating work as a familial responsibility, and tending to integrate work-life boundary rather than separating professional and personal life [

63]. Thus, our findings regarding the curvilinear relationship between supervisor workaholism and subordinate employee performance should be interpreted with caution. Future research should extend the current study to other cultural settings to validate and expand upon our findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Tonglin Wu, Xuguang Hao and Jia Si; Data curation, Tonglin Wu; Formal analysis, Tonglin Wu; Funding acquisition, Tonglin Wu and Xuguang Hao; Investigation, Tonglin Wu; Methodology, Tonglin Wu; Project administration, Jia Si; Resources, Tonglin Wu and Xuguang Hao; Software, Tonglin Wu; Supervision, Xuguang Hao; Validation, Tonglin Wu, Xuguang Hao and Jia Si; Visualization, Tonglin Wu; Writing – original draft, Tonglin Wu; Writing – review & editing, Xuguang Hao and Jia Si.

Funding

This research was funded by POSTGRADUATE INNOVATIVE RESEARCH FUND OF UNIVERSITY OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS, grant number 202247.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because this research included subjects’ perception data (through questionnaires), thus no ethics approval was necessary for the study in accordance with the Local Legislation and Institutional Requirements.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the assistance provided by Professor. Li Guo from the University of International Business and Economics and Professor Jih-Yu Mao from the University of Nottingham Ningbo in improving this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Knight, R. 8 essential qualities of successful leaders. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2023. Available online: https://hbr.org/2023/12/8-essential-qualities-of-successful-leaders (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Clark, M.A.; W. Stevens, G.; S. Michel, J.; Zimmerman, L. Workaholism among leaders: Implications for their own and their followers’ well-being. In Research in Occupational Stress and Well-being; Gentry, W.A., Clerkin, C., Perrewé, P.L., Halbesleben, J.R.B., Rosen, C.C., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2016; Volume 14, pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, S. S. M.; Thompson, L. L. Implications of the protestant work ethic for cooperative and mixed-motive teams. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 4, 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Schaufeli, W. B.; Taris, T. W. “East is east and west is west and never the twain shall meet:” Work engagement and workaholism across eastern and western cultures. J. Behav. Soc. Sci. 2014, 1, 6–24. [Google Scholar]

- She, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhou, J. How CEO workaholism influences firm performance: The roles of collective organizational engagement and TMT power distance. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, P. M.; Vaast, E. Social media and their affordances for organizing: A review and agenda for research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 150–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, R. M.; Aftab, H.; Aslam, S.; Majeed, M. U.; Correia, A. B.; Qureshi, H. A.; Lucas, J. L. Empirical investigation of work-related social media usage and social-related social media usage on employees’ work performance. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, E.; Reid, E. M.; Mazmanian, M. Signs of our time: Time-use as dedication, performance, identity, and power in contemporary workplaces. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2020, 14, 598–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, L. A brief history of long work time and the contemporary sources of overwork. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84 (S2), 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babasanda, F.; Ciobanu, A.; Oancea, R.; Tasențe, T. The relationship between intensity of social media use activity and counterproductive workplace behaviors. Black Sea J. Psychology 2024, 14, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtaza, G.; Neveu, J.-P.; Khan, R.; Talpur, Q. Gossip 2.0: The role of social media and moral attentiveness on counterproductive work behaviour. Appl. Psychol.-Int. Rev. 2023, 72, 1478–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Yao, Z.; Xiong, Z. The impact of work-related use of information and communication technologies after hours on time theft. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 187, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlikowski, W. J.; Scott, S. V. 10 sociomateriality: Challenging the separation of technology, work and organization. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2008, 2, 433–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buono, C.; Farnese, M. L.; Spagnoli, P. The workaholism–technostress interplay: Initial evidence on their mutual relationship. Behav. Sci. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Qian, J.; Parker, S. K. How can people benefit, and who benefits most, from using socialisation-oriented social media at work? An affordance perspective. Human Res. Mgmt. J. 2023, 1748-8583.12504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, W. E. Confessions of a Workaholic: the Facts about Work Addiction; World Publishing: New York, NY, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W. B.; Shimazu, A.; Taris, T. W. Being driven to work excessively hard: The evaluation of a two-factor measure of workaholism in the Netherlands and Japan. Cross Cult. Res. 2009, 43, 320–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M. A.; Smith, R. W.; Haynes, N. J. The multidimensional workaholism scale: Linking the conceptualization and measurement of workaholism. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 1281–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amos, C.; Zhang, L.; Read, D. Hardworking as a heuristic for moral character: Why we attribute moral values to those who work hard and its implications. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 158, 1047–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, G. Work, work ethic, work excess. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2004, 17, 424–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, J. T.; Robbins, A. S. Workaholism: Definition, measurement, and preliminary results. J. Pers. Assess. 1992, 58, 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, S.; Davis, L. G. Burnout: A comparative analysis of personality and environmental variables. Psychol. Rep. 1985, 57 (Suppl. 3), 1319–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.; Zickar, M. J. A cluster analysis investigation of workaholism as a syndrome. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B. E.; Flowers, C.; Ng, K.-M. The relationship between workaholism and marital disaffection: Husbands’ perspective. Fam. J. 2006, 14, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, J. A.; Waters, L. E. Workaholic worker type differences in work-family conflict: The moderating role of supervisor support and flexible work scheduling. Career Dev. Int. 2006, 11, 418–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.-Y. Do workaholic hotel supervisors provide family supportive supervision? A role identity perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 68, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, N.; Morin, A. J. S.; Ndiaye, A.; Colombat, P.; Sandrin, E.; Fouquereau, E. Complementary variable- and person-centred approaches to the dimensionality of workaholism. Appl. Psychol. -Int. Rev. 2022, 71, 312–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wijhe, C. I.; Peeters, M. C. W.; Schaufeli, W. B. Enough is enough: Cognitive antecedents of workaholism and its aftermath. Hum. Resour. Manage. 2014, 53, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, N.; Morin, A. J. S.; Cougot, B.; Gagne, M. Workaholism profiles: Associations with determinants, correlates, and outcomes. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 90, 559–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura. A. Social learning theory; prentice-hall series in social learning theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, D.; Gu, Q.; Zhang, Y. Role modeling effects: How leader’s job involvement affects follower creativity. Asia. Pac. J. Human Res. 2023, 61, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afota, M.-C.; Ollier-Malaterre, A.; Vandenberghe, C. How supervisors set the tone for long hours: Vicarious learning, subordinates’ self-motives and the contagion of working hours. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2019, 29, 100673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D. G. Activation theory and task design: An empirical test of several new predictions. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montani, F.; Vandenberghe, C.; Khedhaouria, A.; Courcy, F. Examining the inverted U-shaped relationship between workload and innovative work behavior: The role of work engagement and mindfulness. Hum. Relat. 2020, 73, 59–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O. Fairness perceptions as a moderator in the curvilinear relationships between job demands, and job performance and job satisfaction. Acad. Manage. J. 2001, 44, 1039–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Yun, S.; Srivastava, A. Evidence for a curvilinear relationship between abusive supervision and creativity in South Korea. Leadersh. Q. 2013, 24, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, M.; Oldham, G. R. The curvilinear relation between experienced creative time pressure and creativity: Moderating effects of openness to experience and support for creativity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, M. A.; Michel, J. S.; Zhdanova, L.; Pui, S. Y.; Baltes, B. B. All work and no play? A meta-analytic examination of the correlates and outcomes of workaholism. J. Manage. 2016, 42, 1836–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Mischel, W. Modifications of self-imposed delay of reward through exposure to live and symbolic models. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1965, 2, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali-Hassan, H.; Nevo, D.; Wade, M. Linking dimensions of social media use to job performance: The role of social capital. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2015, 24, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Benitez, J.; Hu, J. Impact of the usage of social media in the workplace on team and employee performance. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 103160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boy, J. D.; Uitermark, J. Lifestyle enclaves in the instagram city? Soc. Media Soc. 2020, 6, 205630512094069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Wang, H.; Khan, A. N. Mechanism to enhance team creative performance through social media: A transactive memory system approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 91, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühnel, J.; Vahle-Hinz, T.; De Bloom, J.; Syrek, C. J. Staying in touch while at work: Relationships between personal social media use at work and work-nonwork balance and creativity. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 1235–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Puijenbroek, T.; Poell, R. F.; Kroon, B.; Timmerman, V. The effect of social media use on work-related learning. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2014, 30, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, R. M.; Aftab, H.; Aslam, S.; Majeed, M. U.; Correia, A. B.; Qureshi, H. A.; Lucas, J. L. Empirical investigation of work-related social media usage and social-related social media usage on employees’ work performance. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, M. R.; Criscuolo, P.; George, G. Which problems to solve? Online knowledge sharing and attention allocation in organizations. Acad. Manage. J. 2015, 58, 680–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, M.; Chen, A. Empirical investigation of how social media usage enhances employee creativity: The role of knowledge management behavior. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valle, M.; Kacmar, K. M.; Zivnuska, S. Understanding the effects of political environments on unethical behavior in organizations. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 156, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L. J.; Anderson, S. E. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J. Manage. 1991, 17, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; Wang, H.; Kirkman, B. L.; Li, N. Understanding the curvilinear relationships between LMX differentiation and team coordination and performance. Pers. Psychol. 2016, 69, 559–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M. A.; Cheah, J.-H.; Ramayah, T.; Ting, H.; Chuah, F.; Cham, T. H. Moderation analysis: Issues and guidelines. J. Appl. Struct. Equ. Model. 2019, 3, i–xi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S. G.; Aiken, L. S. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences, 3rd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, US, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L. S.; West, S. G.; Reno, R. R. Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions, reprinted; SAGE: Newbury Park, Calif, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B.; Harold, C. M.; Kim, D. Stealing time on the company’s dime: Examining the indirect effect of laissez-faire leadership on employee time theft. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 183, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D. G.; Cummings, L. L. Activation theory and task design: Review and reconceptualization gardner. In Research in Organizational Behavior Edition: 10; Staw, B. W., Cummings, L. L., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Srikanth, P.; Thakur, M.; Dust, S. The curvilinear relationship between abusive supervision and performance: The moderating role of conscientiousness and the mediating role of attentiveness. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 150, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; She, Z. The impact of workaholic leaders on followers’ continuous learning. In The Oxford Handbook of Lifelong Learning, 2nd ed.; London, M., Ed.; Oxford University Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- van Zoonen, W.; Treem, J. W.; ter Hoeven, C. L. A tool and a tyrant: Social media and well-being in organizational contexts. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandon, A.; Kaur, P.; Ruparel, N.; Islam, J. U.; Dhir, A. Cyberloafing and cyberslacking in the workplace: Systematic literature review of past achievements and future promises. Internet Res. 2022, 32, 55–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, V. K. G.; Teo, T. S. H. Cyberloafing: A review and research agenda. Appl. Psychol. -Int. Rev. 2022, 73, 441–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, L.; Meneses, J.; Sil, S.; Silva, T.; Moreira, A. C. Workaholism scales: Some challenges ahead. Behav. Sci. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.; Chan, X. W.; Liu, X. Work–life conflict in China: A confucian cultural perspective. In Work-Life Interface; Adisa, T. A., Gbadamosi, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 249–284. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).