1. Introduction

Skin cancer is the most prevalent form of cancer in humans with over 5.4 million new cases a year in the U.S. alone, with low-risk basal cell carcinoma (BCC): mainly Superficial (SBCC) or nodular (NBCC), non-melanoma skin cancer: (NMSC), constituting roughly 80% of all cancers [

1]. The epidermal keratinocytes are the cellular origin of either BCC, Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC), or other rare carcinomas, all termed Keratinocyte Carcinomas (KC) as well the frequent precancerous Actinic (Solar) Keratosis (AK) lesion. Most KC are caused by solar (actinic) ultraviolet (UV) damage to the DNA. The primary approach to BCC treatment is surgical, such as excisional biopsy and Mohs micrographic surgery, alongside non-surgical destructive options like cryosurgery, laser ablation or mechanical abrasion. Alternatively, for cases with extensive spread or for patients unwilling or unable to undergo surgery, topical chemotherapy agents like 5-fluorouracil cream and Imiquimod or photo dynamic therapy (PDT) are commonly used. [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]

Surgery and destructive techniques, despite their availability, require specialized skills and facilities, are invasive, often result in scarring, and come with a high cost. Complications, though infrequent, can lead to local infections, wound dehiscence, prolonged healing times and noticeable scarring. The high occurrence of actinic lesions has driven the demand for effective non-surgical treatments. Current topical medications include 5FU, which disrupts DNA synthesis, and the immunomodulator Imiquimod, both requiring extended treatment periods. Photo Dynamic Therapy (PDT) is another option, targeting multiple actinic keratoses and SBCCs (but not the frequent NBCC) with photosensitization treatments spanning several weeks (up to 6-12 weeks).

These therapies generally offer an 85-90% success rate in the first year, with a recurrence-free rate of 62.7% over five years for 5FU and 80% for PDT and Imiquimod. These therapies that require 6-12 weeks to complete involve side effects that include local pain, redness, swelling, edema, skin irritation, scarring and systemic adverse events lasting for months, often causing prolongation or cessation of treatment [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Thus, there is an unmet need for a safe and effective non-surgical, rapid, non-invasive alternative in the management of low-risk skin cancer.

As previously published [

11], an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) comprised of a concentrate of proteolytic enzymes enriched in bromelain (CPEEB10%), extracted from the stems of pineapples, was used for the topical treatment of BCC. This API is already approved for eschar removal (debridement) of deep burns in the US and throughout Europe, in addition to many other parts of the world, and is in late clinical development stage for debridement and wound bed preparation of chronic ulcers [

12,

13,

14]. In addition to its proteolytic properties, several studies have demonstrated that bromelain has anti-tumor, proapoptotic and inflammation modulating activities [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

In a study utilizing a mouse model with chemically induced skin papilloma using Dimethylbenzene(a) Anthracene and 12-O-Tetradecanoyl Phorbol-13-Acetate (DMBA–TPA), the application of bromelain on the skin was observed to reduce the tumor’s number and size. This study revealed that the mechanism behind bromelain’s tumor-suppressing effect involves the activation of p53, alterations in the Bax/Bcl-2 balance favoring apoptosis, the activation of caspase enzymes, a reduction in Cox-2 enzyme levels, and the obstruction of the NFκB signaling pathway through modulation of the MAPK and Akt/PKB pathways [

18,

19]. Furthermore, bromelain was found to reduce the growth rate of human epidermoid carcinoma-A431 and melanoma-A375 cell lines, as well as reducing keratinocytes’ capacity for attachment and uncontrolled proliferation [

20]. Bromelain also interferes with the process of metastasis by preventing platelet aggregation and reducing the invasiveness of tumor cells in the B16F10 murine melanoma cell line [

15]. The pro-apoptotic properties of bromelain were also demonstrated in oral squamous cell carcinoma cell lines Ca9-22 and SCC25 [

16]. The inflammation modulating effects may contribute to the scarless healing of the abraded/eroded treated sites and burns. [

13,

14,

15,

16,

21,

24,

25,

26].

We hypothesize that CPEEB represents a multifaceted synergistic approach to Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer (NMSC), specifically for the treatment of Keratinocyte Carcinomas (KC) that include BCC, SCC and AK, exploiting the proteolytic activity to target and destroy the main tumor masses and the underlying UV damaged basal membrane. The anticancer, pro-apoptotic effect should eliminate residual tumor cells that may remain in the treatment site. These effects result in a deep eroded ulcer of the BCC site including the adjacent basal membrane with more superficial ulceration-erosion of the non-cancerous skin surrounding the tumor, combined with the specific antitumor effect. Furthermore, the excellent safety profile of CPEEB and its inflammatory modulating properties are expected to promote fast, effective and scarless healing of the treated area.

This hypothesis has been tested in a small, published proof of concept (POC) study including three patients with six BCCs demonstrating a safe and effective eradication of clinically diagnosed superficially invasive basal cell carcinoma (SBCC), nodular BCC (NBCC), and one invasive Morphea type BCC (MBCC). Topical treatments of 2-4 ml of 10% CPEEB were applied 5-6 times over a period of less than 2 weeks. The treated BCC site, which was surrounded by a Zinc Oxide adhesive barrier, contained a 3-5 mm thick layer of CPEEB10%, and was covered by two layers of Opsite film, an occlusive transparent dressing (Smith & Nephew, Andover, MA). This treatment course ended as expected with a superficial erosion of the treated sites and a deeper small crater, a little larger than the original tumor’ size, all healing without scars in 2-3 weeks. All lesions were clinicaly assessed as completely cleared, with two lesions (a SBCC and the MBCC) that were excised 6 months post treatment, confirming (MOHS technique) complete histological clearence. At present, over 4 years later, none of the lesions have recurred. [

11]

The first POC study was followed by two additional small POC studies, which explored various methods of applying CPEEB5%, which are the subject of this manuscript. The primary objective of the studies was to assess the safety and tolerability of the CPEEB. The secondary objective was to assess the efficacy of the CPEEB in eradicating the BCCs.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design: We conducted a prospective open label trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of CPEEB5% in the treatment of BCC. The study plan included two treatment groups differing in the dosing regimens: (1) seven treatment applications applied every other day, and (2) seven daily treatment applications. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol (MW2020-11-26) was approved by the local institutional review boards and informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. The study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT05157763). In addition, a parallel study with a similar protocol design has been initiated in an Israeli hospital (MOH number 2021-04-21-009660 and Soroka IRB 0385-20).

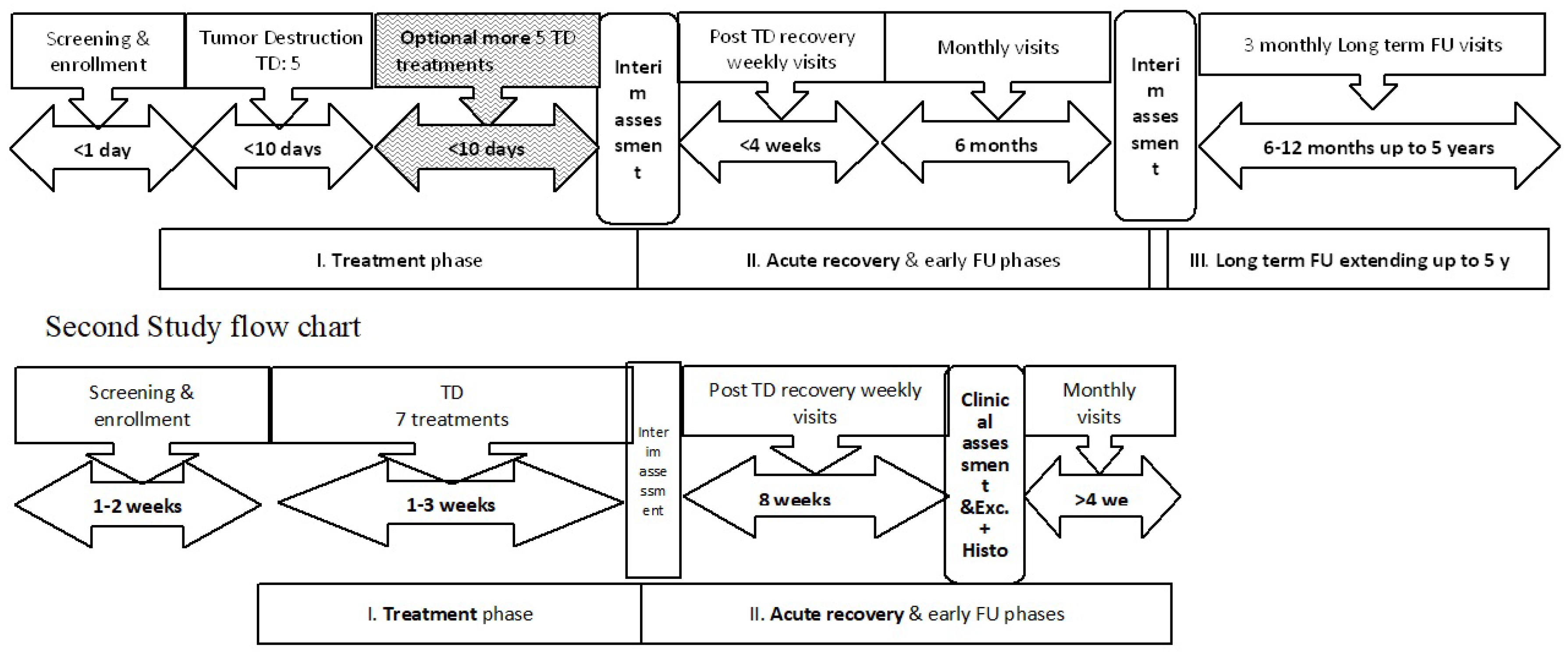

Setting and Subjects: The patients were treated at 4 medical centers, 3 in the US and 1 in Israel, with experienced dermatologists or plastic surgeons serving as the principal investigators. 16 adult patients (15 in the US and 1 in Israel) with one BCC each that was diagnosed clinically and confirmed by shave biopsy, were enrolled and received treatment. Of the 16 patients, 13 were males with an age ranging from 39-89 years. Twelve of the lesions were SBCC with the remainder NBCC. The first two study designs are depicted in

Figure 1.

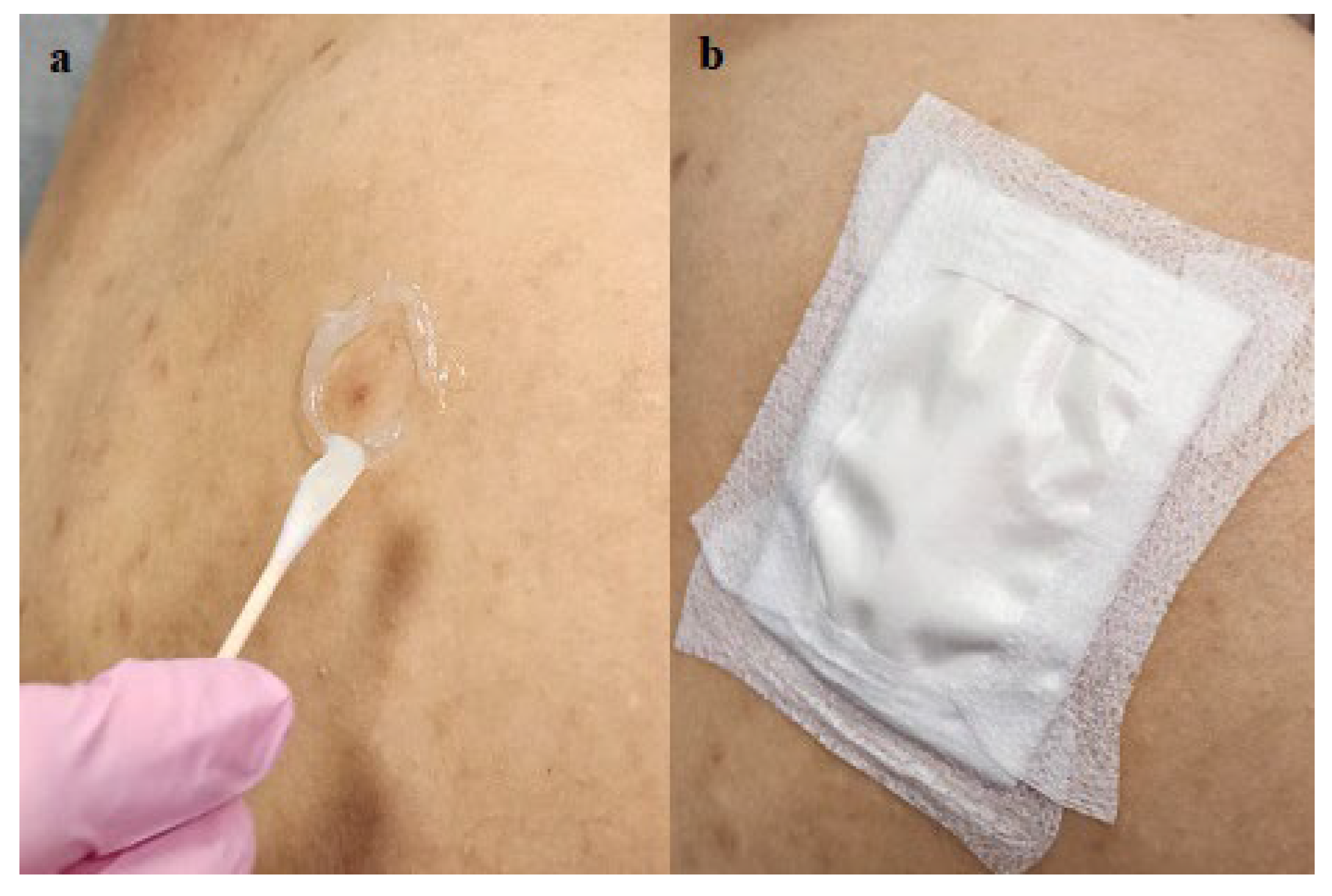

Interventions: In all patients CPEEB with a concentration of 5% (4 g in 10 ml water) was applied topically under an occlusive dressing within an adhesive barrier made of Aquaphor (petrolatum ointment, Beiersdorf AG, Germany) (

Figure 2) or colostomy rings (Coloplast Brava Protective Seal), for a period of 8-12 hours. Different occlusive dressings were used by the clinical sites. The volume of CPEEB applied was dependent on the volume of the occlusive chamber, which varied based on the thickness of the adhesive barrier around the treated site, the nature of the occlusive film and the skin topography.

After the first 11 patients were treated, a data safety monitoring board (DSMB) convened, and it was decided to replace the Aquaphor adhesive barrier with a standard colostomy ring (

Figure 3) in order to simplify and standardize the application procedure and prevent leakage of the topical agent. The corrective action was implemented on 4 additional patients. Following these patients, an additional, last 16th patient was treated with a double colostomy ring (double volume treatment chamber) and a double layer of an occlusion film to prevent evaporation of the CPEEB. Thus, in addition to the first published POC study [

11] in these 2 studies there were 4 treatment groups based on the method of application (

Table 1). Group 1 (n=5) was treated with Aquaphor and a Telfa (non-adherent occlusive dressing, (Covidien, Mansfield, MA). Group 2 (n=6) was treated with Aquaphor (in one case additional silicone gel (Scar-away gel, Alliance Pharma, Cary NC) was applied) and Opsite Flexogrid transparent dressing (Smith & Nephew, Andover, MA) and a hydrocolloid dressing (Duoderm, Convatec, Bridgewater, NJ) dressing. Group 3 (n=4) was treated with a Colostomy ring + Tegaderm dressings while Group 4 (n=1) was treated with two Colostomy rings + a double layer of Tegaderm.

The total duration of the study was approximately 14-17 weeks (see

Figure 1- schematic study timeline). After completion of the treatment phase, the resulting wound was treated conservatively with a petrolatum-based ointment until wound closure. A low potency corticosteroid ointment was applied for several days towards the end of the wound healing phase to prevent formation of any granulation tissue at the discretion of the principal investigator. Two months after treatment all BCC sites were excised and assessed histologically for complete clearance.

Outcomes: The safety endpoints included the incidence and severity of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAE) and serious TEAE as well as presence of abnormal vital signs and pain. The efficacy endpoints were the proportion of patients who reached complete histological clearance of their BCC at the end of the treatment period and the proportion of patients who reached complete clinical clearance of their tumor at the end of the treatment period prior to surgical removal. Additional endpoints included patient compliance with treatment and time to complete healing. Post-hoc analyses evaluated efficacy endpoints in relation to the different application techniques that were implemented in these studies.

Statistical Analysis: Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. Categorical data were summarized with numbers and percentages. Continuous data were summarized as means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges based on data distribution. No formal hypothesis testing was performed.

3. Results

All patients tolerated the treatments very well, reporting a tingling-pricking sensation, 2-4 hours after application, but none asked to discontinue the treatment.

In the 15 patients treated under protocol MW2020-11-26 (groups 1, 2, 3 from the US), two of 4 (50%) patients showed complete histological clearance of SBCC, and 4 of 11 patients showed complete histological clearance of Nodular BCC. Clinical assessment of clearance was more favorable, with the same 50% clearance rate for SBCC, but clearance in 9 of 11 (81.8%) patients with NBCC. The last, 16th patient in Israel (group 4) had a NBCC that was clinically and histologically cleared after 2 months.

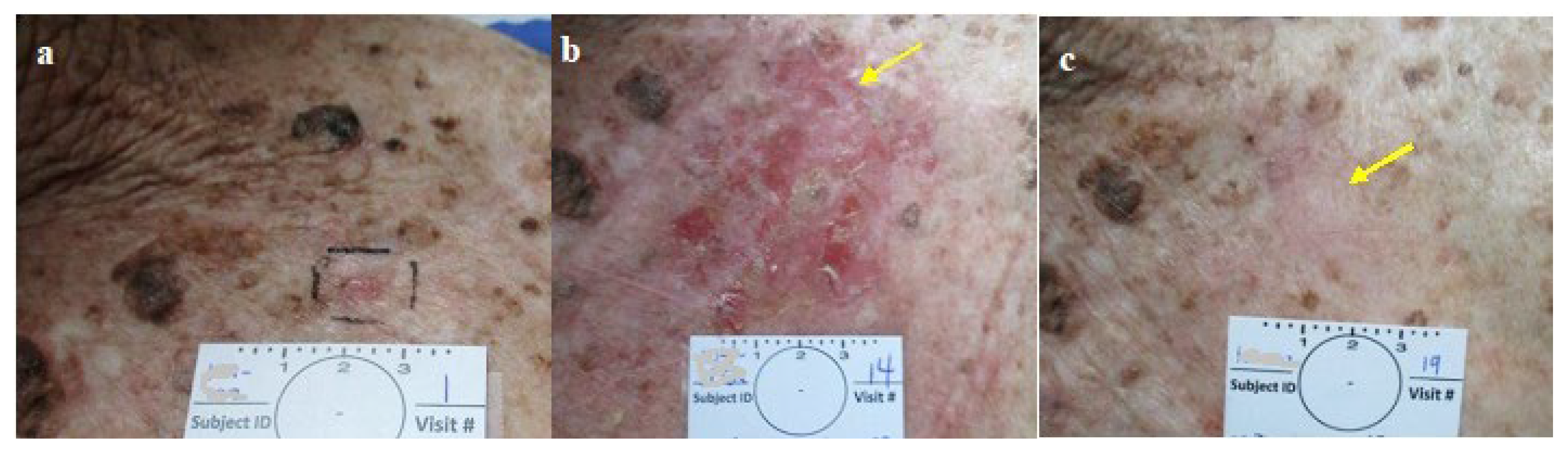

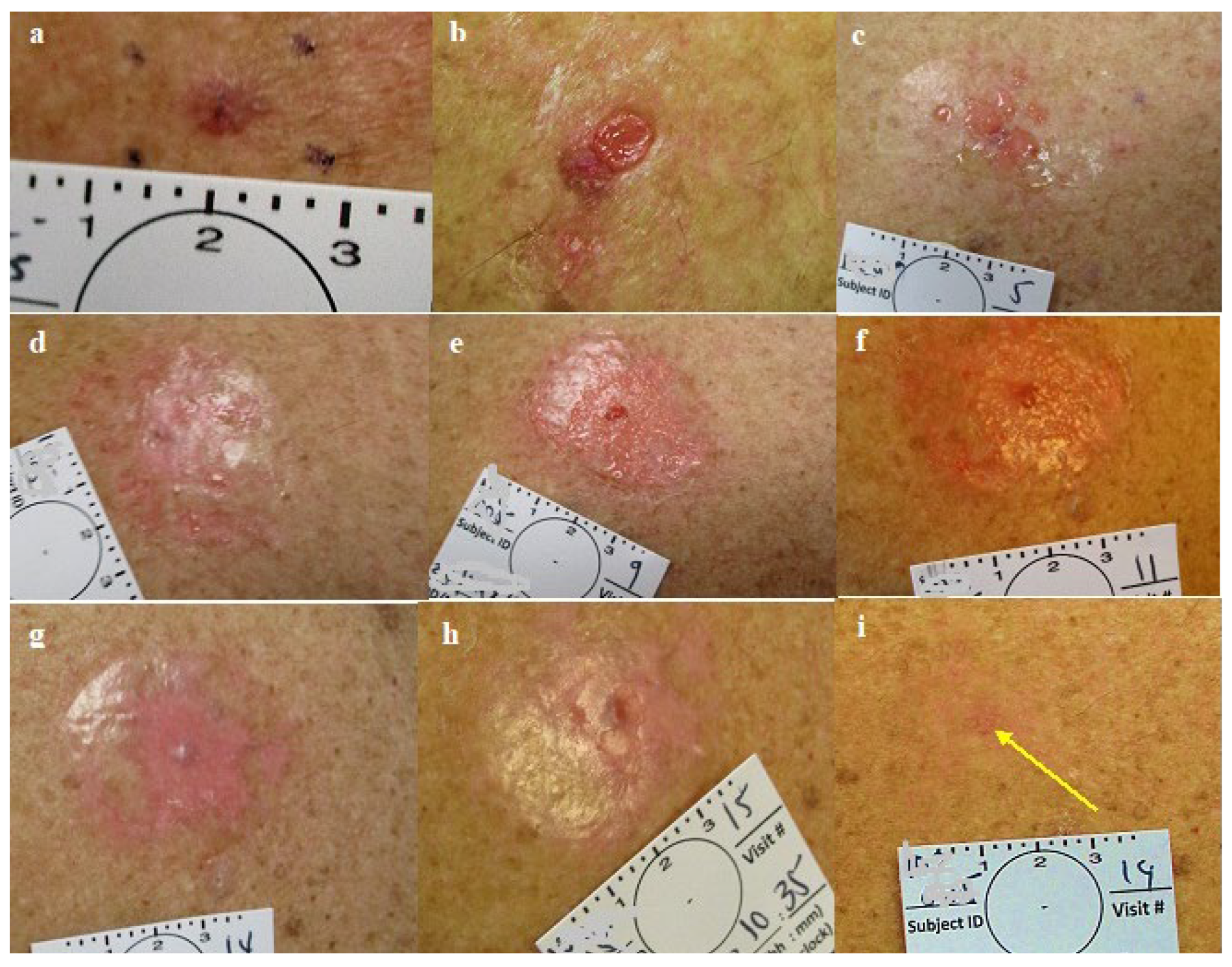

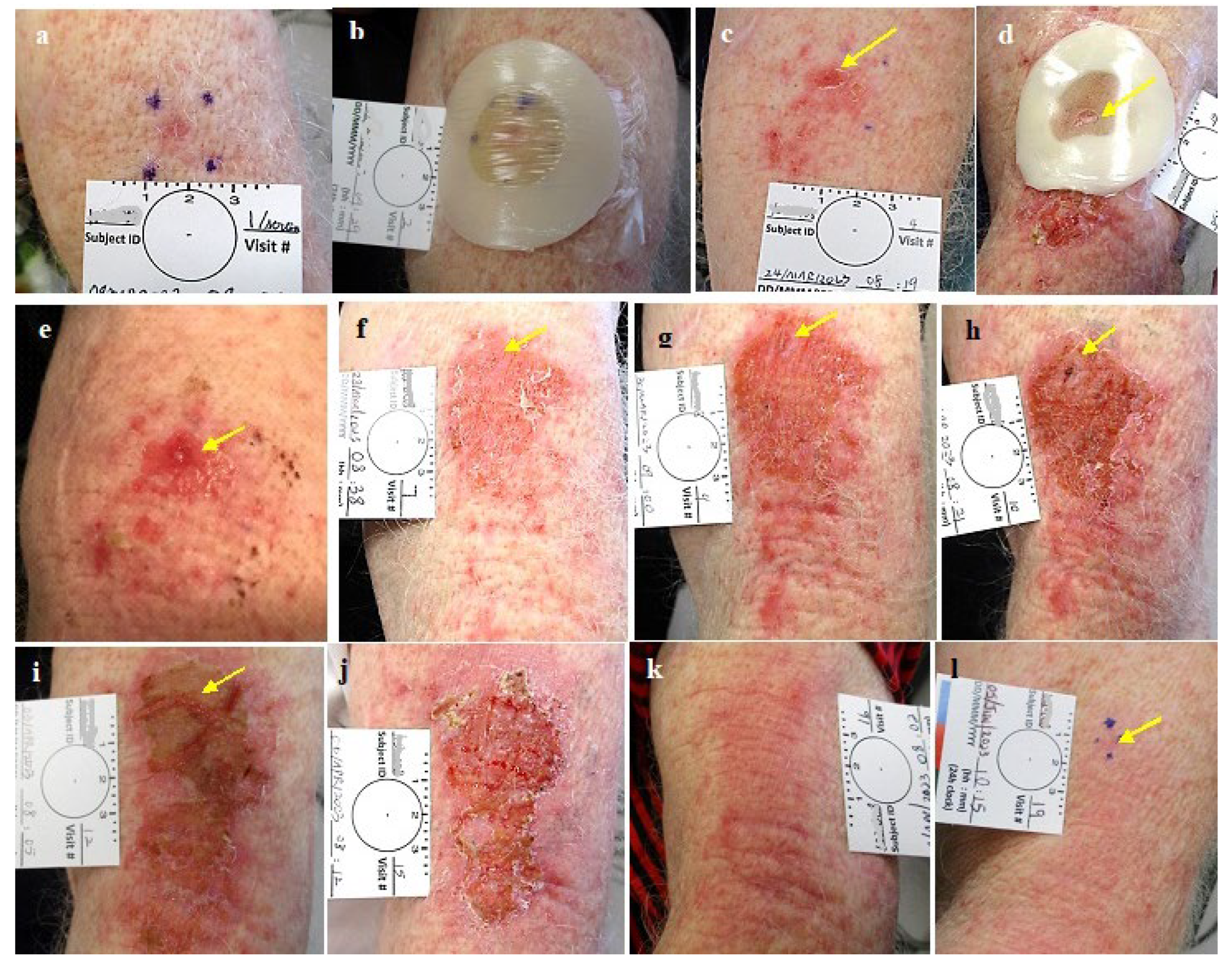

In a post hoc critical review of the photographs documenting all the cases, we saw that the target area (skin with the BCC lesion in the center), exposed to active CPEEB5%, was irritated or abraded after >3 applications and slightly eroded at the end of 7th treatment (

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) allowing an assessment of exposure to the CPEEB5%.

The treatment failed to eradicate the lesion in cases where the volume of the treatment chamber was insufficient to allow the CPEEB to completely cover the lesion that protruded above its level or when Aquaphor dripped down onto the lesion in the treatment chamber, or when a disrupted barrier allowed CPEEB5% to leak out or to desiccate (

Table 1).

The use of Aquaphor (

Figure 2) as a barrier was challenging in being difficult to handle, liquified and often leaked after a few hours, sometimes dripped onto the treatment area possibly covering the lesion. (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). In sites where the barrier was disrupted and the skin beyond the barrier was exposed to the leaking CPEEB, it was irritated showing the exact pattern of the leak and a reduced effect on the target area (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). It seems that the Telfa occlusion was more effective in containing the CPEEB than the Opsite Flexogrid / Duoderm (group 1 compared to group 2). The challenging and unreliable Aquaphor adhesive barrier was the reason that a standard 2.5 mm thick colostomy ring (Coloplast Brava Protective Seal) was chosen to replace the Aquaphor (Group 3). However, the thin ring was found to restrict the chamber’s volume, being effective only in one case when the chamber was overfilled, compensating for the thin ring and slight leak, eradicating the NBCC (

Figure 6). The ring’s application was challenging, often leaking, reducing the already limited CPEEB’s volume (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7).

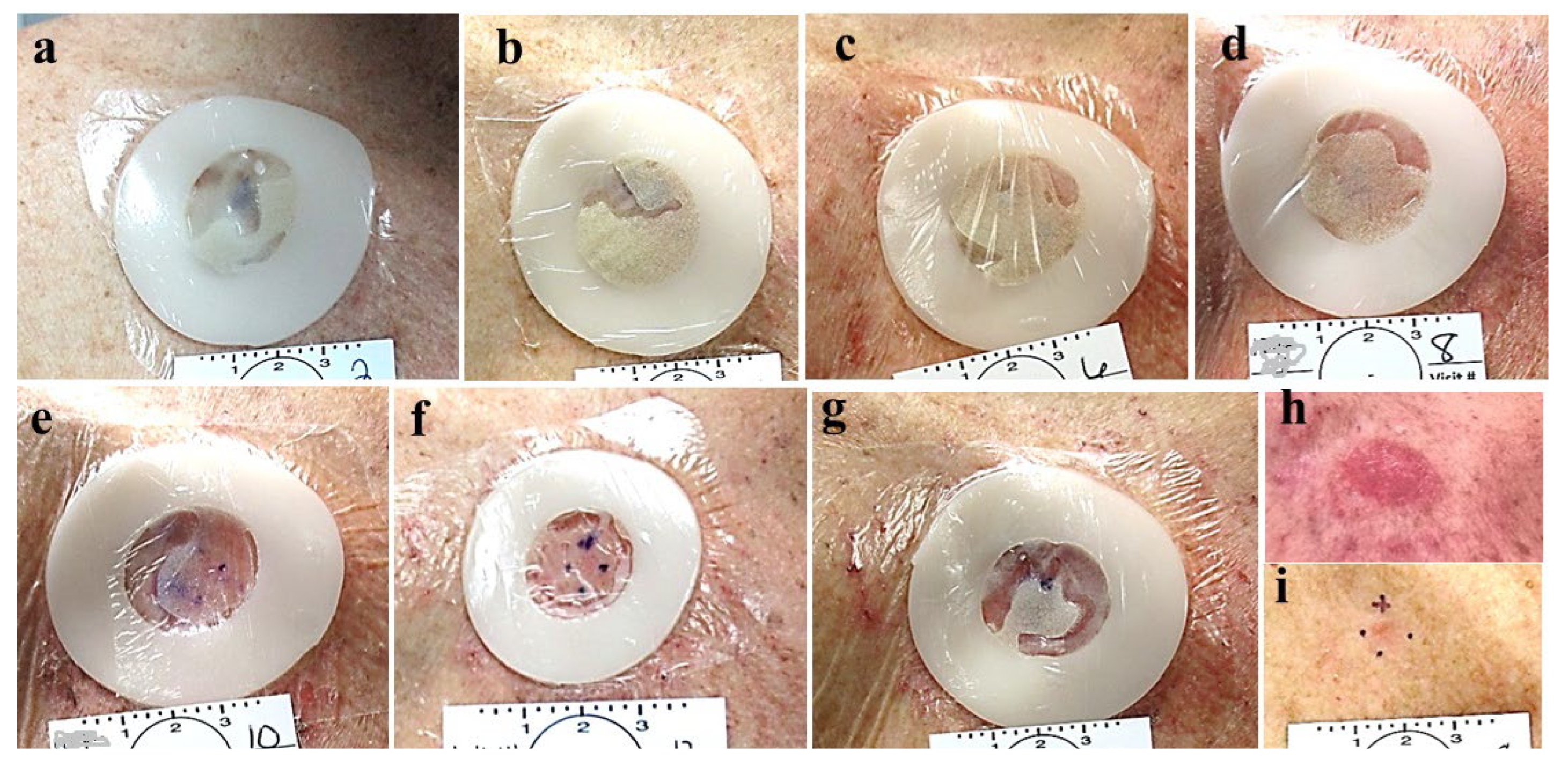

In cases where the CPEEB gel’s water evaporated through the vapor permeable single layer polyurethane film (Tegaderm), the enzyme was inactivated as witnessed by the skin that was not affected (

Figure 8).

In the last case, (Group 4), mitigating the previous studies’ experiences, two colostomy rings, one on top the other, forming a 5 mm thick barrier, were carefully applied to the skin and covered with a double layer of occluding polyurethane film (Tegaderm) to ensure it was watertight, leading to a larger, completely occlusive chamber and a complete clinical and histological clearance of the NBCC in 7 applications. All sites healed completely within 2-3 weeks with good cosmetic results (

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8).

Safety Results

Most TEAEs were mild in severity, and none were considered to be severe. Except for pruritus, no TEAE of moderate severity was reported by more than one patient. Moderate pruritus was reported by two patients. In both of these patients, the pruritus was classified as a Local TEAE and was considered to be treatment related.

Local AEs included: pruritus, pain, burning sensation and also skin reactions e.g., erythema, dermatitis, irritation, erosion, minor bleeding, and secretion/discharge. The local reactions resolved shortly after removal of the CPEEB dressing. AEs other than local AEs were reported by the investigators as not related to study treatment (e.g., distant site SCC, melanoma, lipoma, urinary tract infection. No SAEs were reported in the study. There were no discontinuations due to AEs.

The post treatment healing was uneventful and was completed in approximately 2 weeks with minimal or no scarring. In some cases, the healed skin looked better than the surrounding untreated skin after 2 months, sometimes making it difficult to identify the treated lesion’s site for the diagnostic excisional biopsy (

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

BCC is a slow growing, locally invasive epidermal-originated cutaneous tumor with a metastatic rate of <0.1%. Cutaneous SCC accounts for most of the remainder of NMSC cases, all arising from dysplastic epidermal keratinocytes that also cause the common Actinic Keratosis, forming together the entire spectrum of the larger group of the Keratinocyte Carcinomas (KC). Most of these lesions are low risk and the main damage that they cause is local, invading the dermis, the surrounding skin, and even propagating to deeper structures.

The diagnosis of these cutaneous tumors is rather easy to the trained eye that may be assisted by dermatoscopy and more sophisticated means such as confocal microscopy or biopsy with histopathology. However, very often (especially in the most frequent low risk smaller lesions) pretreatment diagnosis is limited to visual observation with or without dermatoscopy and the success of treatment is defined by a short (1 year) and long term (5 year) clinical assessment of the recurrency rate.

The treatment modality for these lesions should take into consideration their relatively low malignancy and slow growth but also their high incidence, often in the same individual that frequently is aged and with other comorbidities. Choice of treatment of KC depends on risk stratification of the tumor, patient preference or suitability, and availability of local services. High-risk tumors have a greater risk of recurrence and propagation. Therefore, the best and safest choice may be more extensive treatment: excisional surgery followed by histopathology often followed by reconstructive procedures.

As most lesions are small and limited to one or only a few cm², surgical excision under local anesthesia and followed by histopathologic assessment is considered the gold standard. The surgical procedure, though considered as limited and minor, can be rather costly and demanding for the patient. To be covered by the insurance provider, a positive pre-treatment diagnostic biopsy is required, adding to the patient’s discomfort and total costs. In recurrent, high-risk and extensive KC, the gold standard treatment is wide-margin excisional biopsy followed by Mohs Micrographic Surgery (MMS), which is both time and resource consuming. If MMS is not available, excision with predetermined wide margins or additional radiotherapy may be considered. While Mohs surgery is an effective and accurate therapy, it is unfortunately not readily available, is costly and may involve additional psychological trauma to the patients [

7,

9]. Excisional surgery always results in scars that are at least three times longer than the lesions’ diameter and carries the risk of surgical complications such as wound infection, dehiscence, delayed healing and even a larger scar [

4,

7,

9].

Thus, excisional biopsy is often replaced by physical destructive means such as freezing by cryotherapy or cautery by electrotherapy desiccation where it is impossible to have a post treatment histopathological diagnosis, and the success of treatment is determined exclusively by recurrency rate.

The large and growing incidence of these tumors and the challenges related to the available surgical/physical destructive treatments as well as the reluctance of many patients to undergo this ordeal every few months, spurred the development and use of several non-surgical, topically destructive chemical agents. These could be divided into chemical (Aldara-Imiquimod (5%) and 5FU (5%)) and physical light therapy (Photo Dynamic Therapy: PDT). Topical therapies are generally indicated for the more superficial, small size SBCC/SK, multiple lesions, advanced age, contraindication for surgery, immunosuppressed patients, their lower cost, surgery phobia and cosmetic concerns [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Topical 5FU that inhibits DNA synthesis is applied twice a day for up to 12 weeks while the immunomodulator Imiquimod is applied five times a week for up to 6-12 weeks. PDT based on photosensitization (2-6 weeks) is indicated for multiple solar Keratosis-SBCC. All may induce early and late side effects often in association with each other from light sensitivity, pain, edema, burns, pigmentation and scarring to carcinogenesis correlated to local and/or systemic immunosuppression or to the selection of PDT-resistant SCC.

All these non-surgical means are indicated for SBCC and AK but not for the frequent NBCC and share similar efficacy at 1 year (85-90% clearance) with 5-year recurrence rates of 60-80%.

While 5FU and Imiquimod are not expensive, their use involves long and demanding treatment courses (6-12 weeks), frequent local complications (e.g., pain, redness, ulcerations etc.) lasting for several months as well as systemic AEs [

8]. PDT treatment is more expensive and requires adequate setup and monitoring as the entire treatment course involves a local reaction, redness, pain and photosensitivity that may last for months [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. As mentioned, these treatments are not indicated for the common, frequent NBCC.

Despite the availability of non-surgical treatments for many of these tumors, due to the extended treatment time and the noticeable discomfort/complications involved, their use does not adequately address the challenge of this large and growing population. There is an unmet need for safe, effective and fast-acting non-surgical treatment modalities for all these common but demanding skin tumors. The need is for a treatment that will eradicate KC (mainly BCC, SBCC, as well as the more frequent NBCC) with only a few topical applications that will be readily tolerated by the patients without all the sequelae of the existing methods, ending in a scarless skin and 5-year recurrency-free rate of >90%.

CPEEB is known for its strong, multi target proteolytic activity, its potential anti-tumorigenic/ proapoptotic activity, as well as its favorable safety profile. The results of our preliminary studies point to its efficacy in eradicating SBCC and NBCC safely and tolerably when properly applied. The concentration may play a role as in high (10%) concentration it seems to be less sensitive to the application technique than is seen with the 5% concentration [

1]. The series of patients is too small and the variables too large to draw an accurate conclusion.

The proposed mode of action (MOA) of CPEEB in eradicating SBCC as well as NBCC is based on the following two activities:

Proteolysis of the different cutaneous structures according to their extra cellular matrix (ECM) density. This strong activity quickly destroys the tumors’ matrices that differ from the normal, denser and more resistant dermal collagenous extracellular matrix (ECM). This potent proteolysis explains the rapid (few days) eradication of these tumors that does not depend on the long anti-tumorigenic/proapoptotic activities that are related to the tumor’s cells growth cycle, which has a much slower effect. This proteolysis as seen in these studies seems to be dose/application related, also affecting the denser surrounding dermis but in a much weaker way, causing only a superficial erosion of the epidermis and the basal membrane complex underneath. This superficial erosion destroys the tumor’s horizontal edges as well as its vertical edges that penetrate the basal membrane. The immediate destruction of the tumor with its adjacent edges and the basal membrane is similar to surgical excision that removes the tumor with its surrounding tissues.

The role of the basal membrane as a factor and a barrier to tumor formation and propagation is well known as described recently by Riihilä et al. and Kavasi RM. et al. [

27,

28]. In syndromes where the basal membrane is genetically defective, as in Epidermolysis Bullosa or when the basal membrane is damaged by UV exposure, one of the outcomes is the development and propagation of KCs such as BCC and SCC. This pathogenesis explains the role of the UV damaged pathological matrix (basal membrane, ECM, MMPs etc.) that allows the local UV modified damaged Keratocyte cells to coalesce, form and spread as a KC tumor. Removing the tumor and its pathogenetic surrounding eradicates the tumor and decreases its potential recurrency, not unlike wide surgical excision of the tumor and its surrounding tissues.

- 2.

The anti-tumorigenic/proapoptotic effect of the CPEEB, which destroys stray tumor cells that were not removed by the proteolytic activities and may persist at the treatment site [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

Thus, CPEEB presents an application-related non-surgical means that combines an enzymatic “surgery-like” eradication of the tumor with its pathogenetic surrounding and a “chemotherapeutic” effect that are faster, safer and better tolerated than the present 5FU, Imiquimod or PDT. The CPEEB may represent a “next generation” alternative to the present non surgical modalities. The final outcome of fast and scarless healing of the superficial erosion is due to the preserved dermis that is prone to epithelialize and possibly to bromelain’s anti inflammatory properties that modulate rapid, minimally-scarred healing as found in other studies.

In the presented preliminary studies we encountered several challenges that may be considered for future studies:

The reduced concentration from 10% to 5% compared to the first POC may have caused the efficacy to be more application technique sensitive.

The application technique should be fine-tuned following the present study conclusions.

Though histopathological diagnosis is considered the gold standard for tumor diagnosis, in clinical practice, the majority of low risk NMSC KC (BCC, SCC and SK) are clinically-visually diagnosed, with or without dermatoscopy. Based on this non invasive diagnosis, patients are treated (surgically and/or non-surgically) and followed for possible recurrency. Pretreatment histopathology is reserved for the more invasive cases and as a prerequisite for insurance coverage of the entire surgical treatment process that involves two procedures (pre and post treatment surgery) and histopathology. Using biopsies and diagnostic histopathology in trials of low risk lesions does confirm the nature of the lesion that is treated and the completness of eradication but adds a layer of costs, complexity and scarring. The patient with small, low-risk BCC that is aware of the non-surgical, conservative alternatives may be reluctant to join such a study that involves two surgical procedures and more scarring. Thus, designing a surgery-free trial that is based on pre and post treatment clinical/dermatoscopy diagnosis is challanging and will involve more prolonged follow-up (up to 5 years) but may be more appealing to patients.

The final appearance of the treated lesions after 2 months is typical of a fresh, healing wound that easily can be diagnosed as a persistant superficial lesion. Histologically, the inflammation with its atypical cells (which are present at 2 months after treatment) may challenge accurate diagnosis. Thus, the timing for the final, post treatment clearance assessment and biopsy should be done at the end of all healing and inflammatory processes (after 3-6 months).

Following healing of the CPEEB treated sites, the skin looks intact and scarless, sometimes making the identication of the treated tumor’s exact location for assessment and diagnostic excision challenging. Thus, the tumor and its surrounding should be meticulously mapped initially on enrollment or even temporarily tatooed.

Strengths. While small, a strength of the study is the inclusion of two concentrations, different application techniques in multiple sites and investigators. The experienced PIs provided valuable insight regarding the challenges and advantages of CPEEB. All investigators considered the CPEEB 5% treatment to be safe with the resulting brief, local irritation and erosion, minimal and well tolerated by the patients, while noting its fast, complete, scarless healing. The investigators also agreed on the necessity to establish an easy and practical application technique and to confirm the long-term recurrence rate in additional clinical trials.

Limitations. The main limitation of the study is the small sample size limiting the ability to explore additional application techniques and the different treatment groups do not allow pooling and draw statistically significant results. The study was also not powered to demonstrate treatment efficacy or safety. One may argue that the study also lacked a relevant control group for comparison.

5. Conclusions

The results of these preliminary, proof-of-concept studies suggest that CPEEB may be a safe and efective means to treat SBCC and NBCC when properly appplyed in an adequate dose. It may offer a rapid, safe, and dose-dependent effective next generation treatment alternative to current therapies for BCC. Further research and larger scale studies will be necessary to regulate and fully comprehend the potential of CPEEB in the management of low risk BCC and possibly other KC skin tumors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, LR; methodology, LR, YS; data curation, LR, YS, BB, SKT; writing—original draft preparation, LR; writing—review and editing, AJS, YS, MDT; supervision, LR. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

MediWound: Yavneh, Israel.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by all local ethics committees.

Informed Consent Statement

all patients signed written informed consent forms.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

LR and YS are consultants to MediWound LTD that developed and market NexoBrid, EscharEx and the CPEEB. YS served as an investigator in this study. BB has served as an investigator, speaker and/or consultant for Almirall, Biofrontera, BMS, Pfizer, Evommune, Aiviva, Sirnaomics, Mediwound, BPGBio, Lemonex, Thirona and Minolabs. SKT has served as an investigator and consultant to MediWound for this study. AJS is a consultant and speaker for AstraZeneca.

Abbreviations

| 5FU |

5-fluorouracil |

| AE |

Adverse Event |

| AK |

Actinic (Solar) Keratosis |

| API |

Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient |

| BCC |

Basal Cell Carcinoma |

| CPEEB |

Concentrate of Proteolytic Enzymes Enriched in Bromelain |

| DSMB |

Data Safety Monitoring Board |

| IRB |

Institutional Review Board |

| KC |

Keratocyte Carcinoma |

| MBCC |

Morphea type BCC |

| MOH |

Ministry of Health |

| MOHS |

Micrographic Surgery (developed by Fredric E. Mohs 1938) |

| NBCC |

Nodular BCC |

| NMSC |

Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer |

| PDT |

Photo Dynamic Therapy |

| POC |

Proof Of Concept |

| SAE |

Serious Adverse Event |

| SBCC |

Superficial BCC |

| SCC |

Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| TEAE |

Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events |

| UV |

Ultraviolet |

References

- American Cancer Society https://www.cancer.org/.

- Skin cancer foundation https://www.skincancer.org/.

- Cancer.Net https://www.cancer.net/.

- Marzuka, A.G. and S. E. Book, Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med 2015, 88, 167–79. [Google Scholar]

- NCCN Guidelines; Cancer Treatment Reviews 64 (2018) 1-10; UpToDate (01/2021); Arch Dermatol. 1999 Oct;132(10):1177-83. J Invest Dermatol. 2017, 137, 614.

- Queirolo, P. Cinquini, M. Argenziano, G. Bassetto, F. Bossi, P. Boutros, A. Clemente, C. de Giorgi, V. Del Vecchio, M. Patuzzo, R. Peris, K. Quaglino, P. Reali, A. Zalaudek, I. and Spagnolo, F. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of basal cell carcinoma: a GRADE approach for evidence evaluation and recommendations by the Italian Association of Medical Oncology, ESMO Open. 2023, 8, 102037. [Google Scholar]

- Product FDA Labels; UpToDate (01/2021); Arch Dermatol. Redbook (01.2021) 1999, 132, 1177–83.

- Bichakjian, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. Guidelines of care for the management of basal cell carcinoma’. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018, 79, e101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta_AK, Paquet_M, Villanueva_E, Brintnell_W. Interventions for actinic keratoses.Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 12. Art. No.: CD004415. [CrossRef]

- B. Borgia F et al. Early and Late Onset Side Effects of Photodynamic Therapy Biomedicines 2018, 6, 12.

- Rosenberg L, et al. Basal Cell Carcinoma Destruction by a Concentrate of Proteolytic Enzymes Enriched in Bromelain: A Preliminary Report. 2021, 15.

- Shoham, Y. , et al. Bromelain-based enzymatic debridement of chronic wounds: A preliminary report. Int Wound J, 2018.

- Rosenberg L, Shoham Y, Krieger Y, et al. Minimally invasive burn care: a review of seven clinical studies of rapid and selective debridement using a bromelain-based debriding enzyme (Nexobrid®). Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2015, 28, 264–274. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shoham, Y. , et al. Bromelain-based enzymatic debridement of chronic wounds: A preliminary report. Int Wound J, 2018.

- Rathnavelu, V. , et al. Potential role of bromelain in clinical and therapeutic applications. Biomed Rep. 2016, 5, 283–288. [Google Scholar]

- Chobotova, K., A. B. Vernallis, and F.A. Majid. Bromelain’s activity and potential as an anti-cancer agent: Current evidence and perspectives. Cancer Lett 2010, 290, 148–56. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, T.C. , et al. Bromelain inhibits the ability of colorectal cancer cells to proliferate via activation of ROS production and autophagy. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0210274. [Google Scholar]

- Bhui, K. , et al. Bromelain inhibits COX-2 expression by blocking the activation of MAPK regulated NF-kappa B against skin tumor-initiation triggering mitochondrial death pathway. Cancer Lett 2009, 282, 167–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kalra, N. , et al. Regulation of p53, nuclear factor kappaB and cyclooxygenase-2 expression by bromelain through targeting mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in mouse skin. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2008, 226, 30–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bhui, K. , et al. Bromelain inhibits nuclear factor kappa-B translocation, driving human epidermoid carcinoma A431 and melanoma A375 cells through G(2)/M arrest to apoptosis. Mol Carcinog 2012, 51, 231–43. [Google Scholar]

- Maurer, H. R. Bromelain: Biochemistry, pharmacology and medical use. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2001, 58, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paroulek A F, J.M. , Rathinavelu A. The effects of the herbal enzyme bromelain against breast cancer cell line GI101A The FASEB Journal 2010.

- Lee, J.-H. The potential use of bromelain as a natural oral medicine having anticarcinogenic activities. Food Sci Nutr 2019, 7, 1656–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspani, L. , Limiroli, E. , Ferrario, P., and Bianchi, M. In vivo and in vitro effects of bromelain on PGE2 and SP concentrations in the inflammatory exudate in rats. Pharmacology 2002, 65, 83. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, L. P. , Greer, P. K., Trinh, C. T, et al. Treatment with oral bromelain decreases colonic inflammation in the IL-10-deficient murine model of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Immunol. 2005, 116, 135. [Google Scholar]

- ER Secor Jr Bromelain exerts anti-inflammatory effects in an ovalbumin-induced murine model of allergic airway disease. Cell Immunol. 2005, 237, 68–75. [CrossRef]

- Pilvi, Riihilä; et al. Matrix metalloproteinases in keratinocyte carcinomas. Experimental Dermatology. 2021, 30, 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kavasi, R-M; et al. Matrix Effectors in the Pathogenesis of Keratinocyte-Derived Carcinomas. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 879500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the studies. In the first proof of concept (POC) study, the enrollment (1 day) and treatment phases were shorter (no diagnostic histology and only 5-6 daily treatments) compared to the second study. The post treatment phases were longer in the first POC study (excisional biopsy after 6 months for two lesions and follow up for >4 years) compared to the second study where all underwent excisional biopsy after 2 months and follow up until wound closure at 1 month. The 3rd study conducted in Israel followed the same scheme as the second study in the US. TD: tumor destruction; FU: follow up.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the studies. In the first proof of concept (POC) study, the enrollment (1 day) and treatment phases were shorter (no diagnostic histology and only 5-6 daily treatments) compared to the second study. The post treatment phases were longer in the first POC study (excisional biopsy after 6 months for two lesions and follow up for >4 years) compared to the second study where all underwent excisional biopsy after 2 months and follow up until wound closure at 1 month. The 3rd study conducted in Israel followed the same scheme as the second study in the US. TD: tumor destruction; FU: follow up.

Figure 2.

Group 1: a. Application of Aquaphor adhesive barrier and b. coverage by Telfa.

Figure 2.

Group 1: a. Application of Aquaphor adhesive barrier and b. coverage by Telfa.

Figure 3.

Group 3: a-d, the colostomy rings chambers are overfilled so in spite of some leakage (b, c,) and dehydration (e) enough active CPEEB remained to successfully eradicate the BCC.

Figure 3.

Group 3: a-d, the colostomy rings chambers are overfilled so in spite of some leakage (b, c,) and dehydration (e) enough active CPEEB remained to successfully eradicate the BCC.

Figure 4.

Group 1. a. Nodular BCC pre treatment, b. post first treatment, c. post treatment #2. d. one day post treatment #3. e. post treatment #4. f. Post treatment #5. g. One day post treatment #6, pre treatment #7. h. post treatment #7. i. Two months post last treatment, before excisional biopsy see yellow arrow: clinical and histological clearing.

Figure 4.

Group 1. a. Nodular BCC pre treatment, b. post first treatment, c. post treatment #2. d. one day post treatment #3. e. post treatment #4. f. Post treatment #5. g. One day post treatment #6, pre treatment #7. h. post treatment #7. i. Two months post last treatment, before excisional biopsy see yellow arrow: clinical and histological clearing.

Figure 5.

Group 2: CPEEB dripping underneath Aquaphor irritating the exposed skin a. SBCC pre treatment, b. Post 7 applications (arrow points to the lesion). c. 3 weeks later, complete healing, complete clinical clearence but histologically incomplete clearance.

Figure 5.

Group 2: CPEEB dripping underneath Aquaphor irritating the exposed skin a. SBCC pre treatment, b. Post 7 applications (arrow points to the lesion). c. 3 weeks later, complete healing, complete clinical clearence but histologically incomplete clearance.

Figure 6.

Group 2: a. NBCC pre treatment b. post 6 applications (arrow points to the lesion) c. 4 weeks later, complete healing, complete clinical clearence but histologicly suspected residual BCC.

Figure 6.

Group 2: a. NBCC pre treatment b. post 6 applications (arrow points to the lesion) c. 4 weeks later, complete healing, complete clinical clearence but histologicly suspected residual BCC.

Figure 7.

Group 3: Leakage under a colostomy ring with the expected irritation of the exposed skin below the treated lesion decreasing the CPEEB dose. Good healing at 2 weeks and treated area after 2 months before excisional biopsy that was positive for suspected residual BCC in a scar. The arrows point to the treated tumor.

Figure 7.

Group 3: Leakage under a colostomy ring with the expected irritation of the exposed skin below the treated lesion decreasing the CPEEB dose. Good healing at 2 weeks and treated area after 2 months before excisional biopsy that was positive for suspected residual BCC in a scar. The arrows point to the treated tumor.

Figure 8.

Group 3: Evaporation of the CPEEB water through the occluding film. Dry CPEEB crusts are seen on the film’s inner surface in all applications (a-g). At the end of the treatment g: minimal, insuficient effect on the target lesion and surrounding skin and final outcome after 6 weeks (i).

Figure 8.

Group 3: Evaporation of the CPEEB water through the occluding film. Dry CPEEB crusts are seen on the film’s inner surface in all applications (a-g). At the end of the treatment g: minimal, insuficient effect on the target lesion and surrounding skin and final outcome after 6 weeks (i).

Table 1.

Efficacy of CPEEB: Relation to Barrier and Occlusive Film.

Table 1.

Efficacy of CPEEB: Relation to Barrier and Occlusive Film.

| Group % |

Barrier |

Occlusive film |

Water tight |

Leaking dressing |

BCCs S/ N/ M |

Clinical clearance |

Histologic clearance |

POC

10 % |

Thick ZnOx |

x2 Opsite |

Y |

N |

6

3/ 2/ 1 |

Y all |

Y 6/6 |

| 1 5% |

Thick Aquaphor |

Telfa+ Hypafix |

Y |

N |

5

2/3 |

Y all |

Y 5/5 |

| 2 5% |

Thin Aquaphor |

Flexigrid+ DuoDerm |

N |

Y |

6

1/ 5 |

Y 3, N 3 |

N 6/6 |

| 3 5% |

1 ring |

Tegaderm |

N |

Y |

4

1/ 3 |

Y 1, N3 |

Y 1 N 3 |

| 4 5% |

2 rings |

x2 Tegaderm |

Y |

N |

1

0/ 1 |

Y |

Y 1/1 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).