Submitted:

25 September 2024

Posted:

26 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourists’ Willingness to Pay for Sustainable Destinations

2.2. Sustainable Consumption Behaviou (SCB)

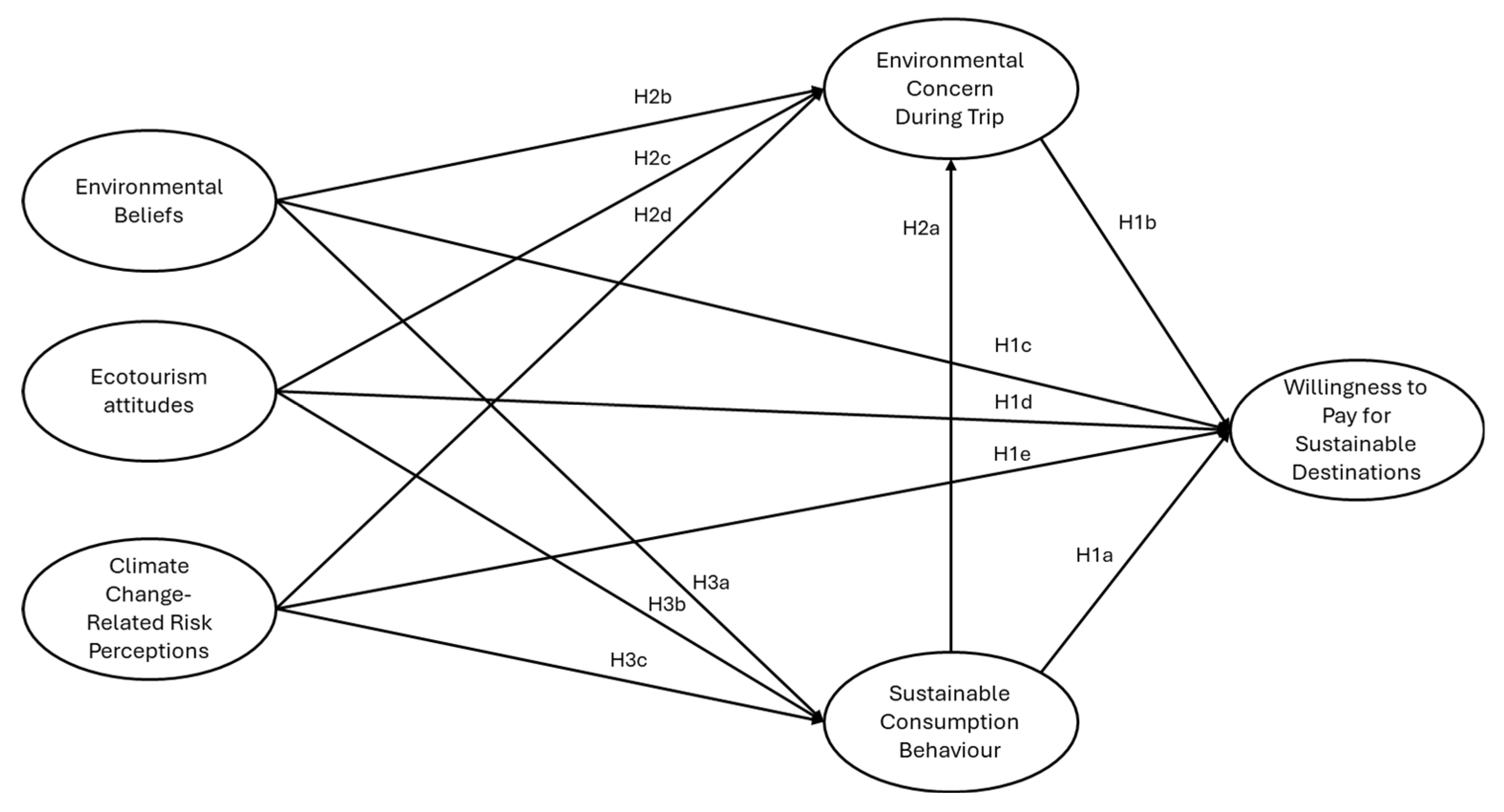

- H1a: Willingness to pay for Sustainable Destinations is positively affected by Sustainable Consumption Behavior.

2.3. Environmental Concern During Trip (ECDT)

- H1b: Willingness to pay for Sustainable Destinations is positively affected by Environmental Concern During Trip.

- H2a: Environmental Concern During Trip is positively affected by Sustainable Consumption Behavior.

2.4. Environmental Beliefs

- H3a: Sustainable Consumption Behavior is positively affected by Environmental Beliefs.

- H2b: Environmental Concern during trip is positively affected by Environmental Beliefs.

- H1c: Willingness to pay for Sustainable Destinations is positively affected by Environmental beliefs.

2.5. Ecotourism Attitudes

- H1d: Willingness to pay for Sustainable Destinations is positively affected by Ecotourism Attitudes.

- H3b: Sustainable Consumption Behavior is positively affected by Ecotourism Attitudes.

- H2c: Environmental Concern During Trip is positively affected by Ecotourism Attitudes.

2.6. Climate Change-Related Risk Perceptions (CC-RRP)

- H3c: Sustainable Consumption Behavior is positively affected by Climate change-related risk perceptions.

- H2d: Environmental Concern During Trip is positively affected by Climate change-related risk perceptions.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Questionnaire Development

3.2. Data Collection Procedures

3.3. Data Analysis Procedures

4. Results

4.1. Assessment of the Measurement Model

4.2. Data Screening

4.3. Dimensionality, Convergent Validity, Reliability, and Discriminant Validity Tests

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Montella, M.M. Wine Tourism and Sustainability: A Review. Sustainability 2017, 9. [CrossRef]

- Paiano, A.; Crovella, T.; Lagioia, G. Managing Sustainable Practices in Cruise Tourism: The Assessment of Carbon Footprint and Waste of Water and Beverage Packaging. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77. [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Burbano, V.C. The Drivers of Greenwashing. Calif. Manage. Rev. 2011, 54, 64–87. [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Mccabe, S. Sustainability and Marketing in Tourism: Its Contexts, Paradoxes, Approaches, Challenges and Potential. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 0, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.R.B.; Crouch, G.I. The Competitive Destination: A Sustainable Tourism Perspective; CABI, 2003; ISBN 0851996647.

- Khalifa, G.S.A. Factors Affecting Tourism Organization Competitiveness: Implications for the Egyptian Tourism Industry. African J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Cucculelli, M.; Goffi, G. Does Sustainability Enhance Tourism Destination Competitiveness? Evidence from Italian Destinations of Excellence. J. Clean. Prod. 2016. [CrossRef]

- López-sánchez, Y.; Pulido-fernández, J.I. In Search of the Pro-Sustainable Tourist: A Segmentation Based on the Tourist “Sustainable Intelligence”. Tour. Perspect. 2016, 17, 59–71. [CrossRef]

- Moeller, T.; Dolnicar, S.; Leisch, F. The Sustainability–Profitability Trade-off in Tourism: Can It Be Overcome? J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 155–169. [CrossRef]

- Masiero, L.; Nicolau, J.L. Price Sensitivity to Tourism Activities: Looking for Determinant Factors. Tour. Econ. 2012, 18, 675–689. [CrossRef]

- Dellaert, B.G.C.; Lindberg, K. Variations in Tourist Price Sensitivity: A Stated Preference Model to Capture the Joint Impact of Differences in Systematic Utility and Response Consistency. Leis. Sci. 2003, 25, 81–96. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [CrossRef]

- Galati, A.; Thrassou, A.; Christofi, M.; Vrontis, D.; Migliore, G. Exploring Travelers’ Willingness to Pay for Green Hotels in the Digital Era. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Manaktola, K.; Jauhari, V. Exploring Consumer Attitude and Behaviour towards Green Practices in the Lodging Industry in India. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 19, 364–377. [CrossRef]

- Seetaram, N.; Song, H.; Ye, S.; Page, S. Estimating Willingness to Pay Air Passenger Duty. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 72, 85–97. [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, L.F.; Langford, I.H.; Kenyon, W. Valuing Marine Parks in a Developing Country: A Case Study of the Seychelles. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2003, 373–390. [CrossRef]

- Reynisdottir, M.; Song, H.; Agrusa, J. Willingness to Pay Entrance Fees to Natural Attractions: An Icelandic Case Study. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 1076–1083. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Jia, J. Tourists’ Willingness to Pay for Biodiversity Conservation and Environment Protection, Dalai Lake Protected Area: Implications for Entrance Fee and Sustainable Management. Ocean Coast. Manag. J. 2012, 62, 24–33. [CrossRef]

- Surendran, A.; Sekar, C. An Economic Analysis of Willingness to Pay (WTP) for Conserving the Biodiversity. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2013, 37, 637–648. [CrossRef]

- Hultman, M.; Kazeminia, A.; Ghasemi, V. Intention to Visit and Willingness to Pay Premium for Ecotourism: The Impact of Attitude, Materialism, and Motivation. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1854–1861. [CrossRef]

- Meleddu, M.; Pulina, M. Evaluation of Individuals’ Intention to Pay a Premium Price for Ecotourism: An Exploratory Study. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2016, 65, 67–78. [CrossRef]

- Aydın, B.; Alvarez, M.D. Understanding the Tourists’ Perspective of Sustainability in Cultural Tourist Destinations. Sustainability 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- de Araújo, A.F.; Andrés Marques, I.; Ribeiro Candeias, T. Tourists’ Willingness to Pay for Environmental and Sociocultural Sustainability in Destinations: Underlying Factors and the Effect of Age. In Proceedings of the Transcending Borders in Tourism Through Innovation and Cultural Heritage; Katsoni, V., Şerban, A.C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 33–56. [CrossRef]

- McCreary, A.; Fatoric, S.; Seekamp, E.; Smith, J.W.; Kanazawa, M.; Davenport, M.A. The Influences of Place Meanings and Risk Perceptions on Visitors’ Willingness to Pay for Climate Change Adaptation Planning in a Nature-Based Tourism Destination. J. Park Recreat. Admi. 2018, 36, 121–140. [CrossRef]

- Jurado-Rivas, C.; Sánchez-Rivero, M. Willingness to Pay for More Sustainable Tourism Destinations in World Heritage Cities: The Case of Caceres, Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- de Araújo, A.F.; Marques, M.I.A.; Candeias, M.T.R.; Viera, A.L. Willingness to Pay for Sustainable Destinations: A Structural Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Hedlund, T. The Impact of Values, Environmental Concern, and Willingness to Accept Economic Sacrifices to Protect the Environment on Tourists’ Intentions to Buy Ecologically Sustainable Tourism Alternatives. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2011, 11, 278–288. [CrossRef]

- Agag, G.; Brown, A.; Hassanein, A.; Shaalan, A. Decoding Travellers’ Willingness to Pay More for Green Travel Products: Closing the Intention-Behaviour Gap. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1551–1575. [CrossRef]

- Dragolea, L.L.; Butnaru, G.I.; Kot, S.; Zamfir, C.G.; Nuţă, A.C.; Nuţă, F.M.; Cristea, D.S.; Ştefănică, M. Determining Factors in Shaping the Sustainable Behavior of the Generation Z Consumer. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Bulut, Z.A.; Kökalan Çımrin, F.; Doğan, O. Gender, Generation and Sustainable Consumption: Exploring the Behaviour of Consumers from Izmir, Turkey. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 597–604. [CrossRef]

- Groening, C.; Sarkis, J.; Zhu, Q. Green Marketing Consumer-Level Theory Review: A Compendium of Applied Theories and Further Research Directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1848–1866. [CrossRef]

- Ertz, M.; Durif, F.; Lecompte, A.; Boivin, C. Does “Sharing” Mean “Socially Responsible Consuming”? Exploration of the Relationship between Collaborative Consumption and Socially Responsible Consumption. J. Consum. Mark. 2018, 35, 392–402. [CrossRef]

- Cesarina Mason, M.; Pauluzzo, R.; Muhammad Umar, R. Recycling Habits and Environmental Responses to Fast-Fashion Consumption: Enhancing the Theory of Planned Behavior to Predict Generation Y Consumers’ Purchase Decisions. Waste Manag. 2022, 139, 146–157. [CrossRef]

- Stănescu, C.G. The Responsible Consumer in the Digital Age: On the Conceptual Shift from ‘Average’ to ‘Responsible’ Consumer and the Inadequacy of the ‘Information Paradigm’ in Consumer Financial Protection. Tilbg. Law Rev. 2018, 24, 49–67. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, V.M.; Schänzel, H.A. A Tourism Inflex: Generation Z Travel Experiences. J. Tour. Futur. 2019, 5, 127–141. [CrossRef]

- Jham, V.; Malhotra, G. Relationship between Ethics and Buying: A Study of the Beauty and Healthcare Sector in the Middle East. Int. J. Serv. Technol. Manag. 2019, 25, 36–52.

- Nittala, R. Green Consumer Behavior of the Educated Segment in India. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2014, 26, 138–152. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Qin, Z.; Yuan, Q. The Impact of Eco-Label on the Young Chinese Generation: The Mediation Role of Environmental Awareness and Product Attributes in Green Purchase. Sustainability 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. Sustainable Consumption. In Handbook of sustainable development; Atkinson, G., Dietz, S., Neumayer, E., Eds.; MPG Books: Cheltenham, 2007; pp. 254–268. [CrossRef]

- Lehner, M.; Mont, O.; Heiskanen, E. Nudging – A Promising Tool for Sustainable Consumption Behaviour? J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 166–177. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. The Influence of Attitudes on Behavior. 2014.

- Kaiser, F.G.; Schultz, P.W. The Theory of Planned Behavior Without Compatibility? Beyond Method Bias and Past Trivial Associations. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 1522–1544. [CrossRef]

- Terlau, W.; Hirsch, D. Sustainable Consumption and the Attitude-Behaviour-Gap Phenomenon - Causes and Measurements towards a Sustainable Development. Proc. Food Syst. Dyn. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Guzmán Rincón, A.; Carrillo Barbosa, R.L.; Martín-Caro Álamo, E.; Rodríguez-Cánovas, B. Sustainable Consumption Behaviour in Colombia: An Exploratory Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Lazaroiu, G.; Andronie, M.; Uţă, C.; Hurloiu, I. Trust Management in Organic Agriculture: Sustainable Consumption Behavior, Environmentally Conscious Purchase Intention, and Healthy Food Choices. Front. Public Heal. 2019, 7. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Jha, M. Values Influencing Sustainable Consumption Behaviour: Exploring the Contextual Relationship. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 76, 77–88. [CrossRef]

- Al-Nuaimi, S.R.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Sustainable Consumption and Education for Sustainability in Higher Education. Sustainability 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, D.L. Contemporary Marketing; 15th ed.; South-Western Cengage Learning: Mason, Ohio, 2012; ISBN 9781111221782.

- Majeed, M.U.; Aslam, S.; Murtaza, S.A.; Attila, S.; Molnár, E. Green Marketing Approaches and Their Impact on Green Purchase Intentions: Mediating Role of Green Brand Image and Consumer Beliefs towards the Environment. Sustainability 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.C.Y. The Influence of Attitudes towards Healthy Eating on Food Consumption When Travelling. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.A.; Higham, J.E.S. Eyes Wide Shut? UK Consumer Perceptions on Aviation Climate Impacts and Travel Decisions to New Zealand. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 323–335. [CrossRef]

- Budeanu, A. Sustainable Tourist Behaviour – A Discussion of Opportunities for Change. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 499–508. [CrossRef]

- Juvan, E.; Dolnicar, S. The Attitude–Behaviour Gap in Sustainable Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 48, 76–95. [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Framing Behavioural Approaches to Understanding and Governing Sustainable Tourism Consumption: Beyond Neoliberalism, “Nudging” and “Green Growth”? J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 1091–1109. [CrossRef]

- Juvan, E.; Dolnicar, S. Drivers of Pro-Environmental Tourist Behaviours Are Not Universal. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 879–890. [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S. Tourist Behaviour Change for Sustainable Consumption (SDG Goal12): Tourism Agenda 2030 Perspective Article. Tour. Rev. 2023, 78, 326–331. [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Degrowing Tourism: Décroissance, Sustainable Consumption and Steady-State Tourism. Anatolia 2009, 20, 46–61. [CrossRef]

- Nekmahmud, M.; Ramkissoon, H.; Fekete-Farkas, M. Green Purchase and Sustainable Consumption: A Comparative Study between European and Non-European Tourists. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 43, 100980. [CrossRef]

- Matharu, M.; Jain, R.; Kamboj, S. Understanding the Impact of Lifestyle on Sustainable Consumption Behavior: A Sharing Economy Perspective. Manag. Environ. Qual. An Int. J. 2021, 32, 20–40. [CrossRef]

- Testa, R.; Galati, A.; Schifani, G.; Di Trapani, A.M.; Migliore, G. Culinary Tourism Experiences in Agri-Tourism Destinations and Sustainable Consumption—Understanding Italian Tourists’ Motivations. Sustainability 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Merrilees, B.; Coghlan, A. Sustainable Urban Tourism: Understanding and Developing Visitor pro-Environmental Behaviours. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 26–46. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S.; Oates, C.; Thyne, M.; Alevizou, P.; McMorland, L.A. Comparing Sustainable Consumption Patterns across Product Sectors. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 137–145. [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D. The “New Environmental Paradigm”. J. Environ. Educ. 1978, 9, 10–19. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, S.M.; Manata, B. Measurement of Environmental Concern: A Review and Analysis. Front. Psuchology 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Weigel, R.; Weigel, J. Environmental Concern: The Development of a Measure. Environ. Behav. 1978, 10, 3–15. [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and Social Factors That Influence Pro-Environmental Concern and Behaviour: A Review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [CrossRef]

- Hirsh, J.B. Personality and Environmental Concern. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 245–248. [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T. The Value Basis of Environmental Concern. J. Soc. Issues 1994, 50, 65–84. [CrossRef]

- Takács-Sánta, A. Barriers to Environmental Concern. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2007, 14, 26–38.

- Kim, H.; Borges, M.C.; Chon, J. Impacts of Environmental Values on Tourism Motivation: The Case of FICA, Brazil. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 957–967. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.-M.; Wu, H.C. How Do Environmental Knowledge, Environmental Sensitivity, and Place Attachment Affect Environmentally Responsible Behavior? An Integrated Approach for Sustainable Island Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 557–576. [CrossRef]

- Corral-Verdugo, V.; Armendáriz, L.I. The “New Environmental Paradigm” in a Mexican Community. J. Environ. Educ. 2000, 31, 25–31. [CrossRef]

- Gooch, G.D. Environmental Beliefs and Attitudes in Sweden and the Baltic States. Environ. Behav. 1995, 27, 513–539. [CrossRef]

- Wiidegren, Ö. The New Environmental Paradigm and Personal Norms. Environ. Behav. 1998, 30, 75–100. [CrossRef]

- Catton, W.R.; Dunlap, R.E. Environmental Sociology: A New Paradigm. Am. Sociol. 1978, 13, 41–49.

- Huang, H. Media Use, Environmental Beliefs, Self-Efficacy, and pro-Environmental Behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2206–2212. [CrossRef]

- Corraliza, J.A.; Berenguer, J. Environmental Values, Beliefs, and Actions: A Situational Approach. Environ. Behav. 2000, 32, 832–848. [CrossRef]

- Buttel, F.H.; Flinn, W.L. Social Class and Mass Environmental Beliefs: A Reconsideration. Environ. Behav. 1978, 10, 433–450. [CrossRef]

- McCarty, J.A.; Shrum, L.J. The Influence of Individualism, Collectivism, and Locus of Control on Environmental Beliefs and Behavior. J. Public Policy Mark. 2001, 20, 93–104. [CrossRef]

- Kilbourne, W.; Pickett, G. How Materialism Affects Environmental Beliefs, Concern, and Environmentally Responsible Behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 885–893. [CrossRef]

- Edgell, M.C.R.; Nowell, D.E. The New Environmental Paradigm Scale: Wildlife and Environmental Beliefs in British Columbia. Soc. Nat. Resour. 1989, 2, 285–296. [CrossRef]

- Corral-Verdugo, V.; Bechtel, R.B.; Fraijo-Sing, B. Environmental Beliefs and Water Conservation: An Empirical Study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 247–257. [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.-J. Hotels’ Environmental Policies and Employee Personal Environmental Beliefs: Interactions and Outcomes. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 436–446. [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Lee, S.; Lee, C.-K.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, N.-J. An Integrated Model of Travelers’ pro-Environmental Decision-Making Process: The Role of the New Environmental Paradigm. Asia Pacific J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 935–948. [CrossRef]

- Patwary, A.K. Examining Environmentally Responsible Behaviour, Environmental Beliefs and Conservation Commitment of Tourists: A Path towards Responsible Consumption and Production in Tourism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 5815–5824. [CrossRef]

- Perkins, H.E.; Brown, P.R. Environmental Values and the So-Called True Ecotourist. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 793–803. [CrossRef]

- Wurzinger, S.; Johansson, M. Environmental Concern and Knowledge of Ecotourism among Three Groups of Swedish Tourists. J. Travel Res. 2006, 45, 217–226. [CrossRef]

- Barber, N.; Taylor, D.C.; Deale, C.S. Wine Tourism, Environmental Concerns, and Purchase Intention. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 146–165. [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S. Designing for More Environmentally Friendly Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102933. [CrossRef]

- Hultman, M.; Kazeminia, A.; Ghasemi, V. Intention to Visit and Willingness to Pay Premium for Ecotourism: The Impact of Attitude, Materialism, and Motivation. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1854–1861. [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.S.T.; Khanh, C.N.T. Ecotourism Intention: The Roles of Environmental Concern, Time Perspective and Destination Image. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 1141–1153. [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.C.; Murray, I. Resident Attitudes toward Sustainable Community Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 575–594. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-Y.; Chen, M.-Y.; Yang, S.-C. Residents’ Attitudes toward Support for Island Sustainable Tourism. Sustainability 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Kitnuntaviwat, V.; Tang, J.C.S. Residents’ Attitudes, Perception and Support for Sustainable Tourism Development. Tour. Hosp. Plan. Dev. 2008, 5, 45–60. [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-P. (Simon); Chancellor, H.C.; Cole, S.T. Measuring Residents’ Attitudes toward Sustainable Tourism: A Reexamination of the Sustainable Tourism Attitude Scale. J. Travel Res. 2009, 50, 57–63. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Liu, J.; Wei, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, L. Residents’ Attitudes towards Sustainable Tourism Development in a Historical-Cultural Village: Influence of Perceived Impacts, Sense of Place and Tourism Development Potential. Sustainability 2017, 9. [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, K.B. Attitudes towards ‘Sustainable Tourism’ in the UK: A View from Local Government. Tour. Manag. 1998, 19, 213–224. [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Alletorp, L. Attitudes in the Danish Tourism Industry to the Roles of Business and Government in Sustainable Tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2001, 3, 91–103. [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, T. Business Attitudes to Sustainable Tourism: Self-regulation in the UK Outgoing Tourism Industry. J. Sustain. Tour. 1995, 3, 210–231. [CrossRef]

- Arrobas, F.; Ferreira, J.; Brito-Henriques, E.; Fernandes, A. Measuring Tourism and Environmental Sciences Students’ Attitudes towards Sustainable Tourism. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2020, 27, 100273. [CrossRef]

- Firth, T.; Hing, N. Ecotourism Intention: The Roles of Environmental Concern, Time Perspective and Destination Image. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 251–254. [CrossRef]

- Faleh Hunitie, M.; Saraireh, S.; Salem Al-Srehan, H.; Zakariya Al- Quran, A. Ecotourism Intention in Jordan: The Role of Ecotourism Attitude, Ecotourism Interest, and Destination Image. Inf. Sci. Lett. 2022, 11.

- Singh, T.; Slotkin, M.H.; Vamosi, A.R. Attitude towards Ecotourism and Environmental Advocacy: Profiling the Dimensions of Sustainability. J. Vacat. Mark. 2007, 13, 119–134. [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Verdugo, M.; Vega-Vázquez, M.; Oviedo-García, M.Á.; Orgaz-Agüera, F. The Relevance of Psychological Factors in the Ecotourist Experience Satisfaction through Ecotourist Site Perceived Value. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 124, 226–235. [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-García, M.Á.; Castellanos-Verdugo, M.; Vega-Vázquez, M.; Orgaz-Agüera, F. The Mediating Roles of the Overall Perceived Value of the Ecotourism Site and Attitudes Towards Ecotourism in Sustainability Through the Key Relationship Ecotourism Knowledge-Ecotourist Satisfaction. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 203–213. [CrossRef]

- Thi Khanh, C.N.; Phong, L.T. Impact of Environmental Belief and Nature-Based Destination Image on Ecotourism Attitude. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2020, 3, 489–505. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Sharma, S.; Sinha, S.K. How Sustainable Practices Influence Guests’ Willingness to Pay a Price Premium in Fiji. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2023, 15, 269–278. [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.C.C.; Gursoy, D.; Del Chiappa, G. The Influence of Materialism on Ecotourism Attitudes and Behaviors. J. Travel Res. 2014, 55, 176–189. [CrossRef]

- Grilli, G.; Tyllianakis, E.; Luisetti, T.; Ferrini, S.; Turner, R.K. Prospective Tourist Preferences for Sustainable Tourism Development in Small Island Developing States. Tour. Manag. 2021, 82, 104178. [CrossRef]

- Böhm, G.; Pfister, H.-R. Tourism in the Face of Environmental Risks: Sunbathing under the Ozone Hole, and Strolling through Polluted Air. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2011, 11, 250–267. [CrossRef]

- Cheng DeNian, C.D.; Zhou YongBo, Z.Y.; Wei XiangDong, W.X.; Wu Jian, W.J. A Study on the Environmental Risk Perceptions of Inbound Tourists for China Using Negative IPA Assessment. 2015.

- De Urioste-Stone, S.M.; Le, L.; Scaccia, M.D.; Wilkins, E. Nature-Based Tourism and Climate Change Risk: Visitors’ Perceptions in Mount Desert Island, Maine. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2016, 13, 57–65. [CrossRef]

- Shakeela, A.; Becken, S. Understanding Tourism Leaders’ Perceptions of Risks from Climate Change: An Assessment of Policy-Making Processes in the Maldives Using the Social Amplification of Risk Framework (SARF). J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 65–84. [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.; Clark, J.R.A.; Malesios, C. Social Capital and Willingness-to-Pay for Coastal Defences in South-East England. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 119, 74–82. [CrossRef]

- Viscusi, W.K.; Zeckhauser, R.J. The Perception and Valuation of the Risks of Climate Change: A Rational and Behavioral Blend. Clim. Change 2006, 77, 151–177. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.J.; Kahlor, L.A.; Griffin, D.J. I Share, Therefore I Am: A U.S.−China Comparison of College Students’ Motivations to Share Information about Climate Change. Hum. Commun. Res. 2014, 40, 112–135. [CrossRef]

- Cameron, T.A. Individual Option Prices for Climate Change Mitigation. J. Public Econ. 2005, 89, 283–301. [CrossRef]

- Hamed, A.; Madani, K.; Von Holle, B.; Wright, J.; Milon, J.W.; Bossick, M. How Much Are Floridians Willing to Pay for Protecting Sea Turtles from Sea Level Rise? Environ. Manage. 2016, 57, 176–188. [CrossRef]

- Joireman, J.; Barnes Truelove, H.; Duell, B. Effect of Outdoor Temperature, Heat Primes and Anchoring on Belief in Global Warming. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 358–367. [CrossRef]

- Ghaffar, A.; Islam, T. Factors Leading to Sustainable Consumption Behavior: An Empirical Investigation among Millennial Consumers. Kybernetes 2024, 53, 2574–2592. [CrossRef]

- Saari, U.A.; Damberg, S.; Frömbling, L.; Ringle, C.M. Sustainable Consumption Behavior of Europeans: The Influence of Environmental Knowledge and Risk Perception on Environmental Concern and Behavioral Intention. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 189, 107155. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Zhong, W.; Naz, S. Can Environmental Knowledge and Risk Perception Make a Difference? The Role of Environmental Concern and Pro-Environmental Behavior in Fostering Sustainable Consumption Behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Hsu, L.T.; Han, H.; Kim, Y. Understanding How Consumers View Green Hotels: How a Hotel’s Green Image Can Influence Behavioural Intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 901–914. [CrossRef]

- Atzori, R.; Fyall, A.; Tasci, A.D.A.; Fjelstul, J. The Role of Social Representations in Shaping Tourist Responses to Potential Climate Change Impacts: An Analysis of Florida ’ s Coastal Destinations. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Leiserowitz, A.; Maibach, E.W.; Roser-Renouf, C.; Feinberg, G.; Howe, P. Climate Change in the American Mind: Americans’ Global Warming Beliefs and Attitudes in April 2013; 2013. [CrossRef]

- Lorenzoni, I.; Leiserowitz, A.; De Franca Doria, M.; Poortinga, W.; Pidgeon, N.F. Cross-National Comparisons of Image Associations with “Global Warming” and “Climate Change” Among Laypeople in the United States of America and Great Britain1 . J. Risk Res. 2006, 9, 265–281. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.L. Interactive LISREL in Practice: Getting Started with a SIMPLIS Approach; Springer: London, 2011;

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; 7th ed.; Pearson, 2014;

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R.; Black, W. Multivariate Data Analysis; 5th ed.; Prentice Hall International: London, 1998;

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; 4th ed.; Guilford Press, 2015;

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; Wiley: New York, 1989;

- Barnes, J.; Cote, J.; Cudeck, R.; Malthouse, E. Factor Analysis - Checking Assumptions of Normality Before Conducting Factor Analysis. J. Consum. Psychol. 2001, 10, 79–81.

- Cote, J.; Netemeyer, R.; Bentler, P. Structural Equations Modeling - Improving Model Fit by Correlating Errors. J. Consum. Psychol. 2001, 10, 87–88.

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, 2007;

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [CrossRef]

- Gerbing, D.W.; Anderson, J.C. An Updated Paradigm for Scale Development Incorporating Unidimensionality and Its Assessment. J. Mark. Res. 1988, 25, 186–192. [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K. Marketing Research: An Applied Orientation; Prentice Hall: New Jersey, 1996;

- Nunnally, J. Psychometric Theory; 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, 1978;

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Youjae Yi On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [CrossRef]

- Hancock, G.R.; Mueller, R.O. Rethinking Construct Reliability Within Latent Variable Systems. In Structural Equation Modeling: Present and Future; Cudeck, R., du Toit, S., Sörbom, D., Eds.; Scientific Software International, 2001; pp. 195–216.

- Raykov, T. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1997. [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J.A. Introducing LISREL; SAGE Publications: London, 2000;

- Kuhn, T. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1966; ISBN 0226458075.

- Lewis, S.L.; Maslin, M. The Human Planet: How Humans Caused the Anthropocene; Penguin and Yale University Press, 2018;

- Oreskes, N.; Conway, M. Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming; Bloomsbury, 2012;

- Maslin, M. Climate Change: A Very Short Introduction; 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2021; ISBN 978–0–19–263863–2.

- World Bank Group. International Tourism, Number of Arrivals: World Tourism Organization, Yearbook of Tourism Statistics, Compendium of Tourism Statistics and Data Files Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ST.INT.ARVL?end=2020&start=1995.

- Lo, J.S.K.; McKercher, B. Tourism gentrification and neighbourhood transformation. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2023, 9, 923–939. [CrossRef]

- Pásková, M.; Štekerová, K.; Zanker, M.; Lasisi, T.T.; Zelenka, J. Water Pollution Generated by Tourism: Review of System Dynamics Models. Heliyon 2024, 10. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Jia, L. Estimation of Carbon Emissions from Tourism Transport and Analysis of Its Influencing Factors in Dunhuang. Sustainability 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. New Trends in Measuring Environmental Attitudes: Measuring Endorsement of the New Ecological Paradigm: A Revised NEP Scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Schwartz, S.; Capanna, C.; Vecchione, M.; Barbaranelli, C. Personality and Politics: Values, Traits, and Political Choice. Polit. Psychol. 2006, 27, 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Fukukawa, K.; Shafer, W.E.; Lee, G.M. Values and Attitudes Toward Social and Environmental Accountability: A Study of MBA Students. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 71, 381–394. [CrossRef]

| N (1545) | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 571 | 37,0 |

| Male | 970 | 62,8 |

| Other/preferred not to say | 4 | ,3 |

| Country of residence | ||

| Spain | 1313 | 85,0 |

| Portugal | 232 | 15,0 |

| Age | ||

| 18 to 24 years | 847 | 54,8 |

| 25 to 34 years | 157 | 10,2 |

| 35 to 44 years | 168 | 10,9 |

| 45 to 54 years | 241 | 15,6 |

| 55 to 64 years | 114 | 7,4 |

| 65 years or more | 18 | 1,2 |

| Formal education | ||

| University degree | 734 | 47,5 |

| Secondary school | 575 | 37,2 |

| Masters’ degree or PhD | 157 | 10,2 |

| Primary school | 70 | 4,5 |

| No formal education | 9 | ,6 |

| Monthly family income | ||

| Up to 1,000€ | 307 | 20,4 |

| 1000 to 1500€ | 370 | 24,6 |

| 1051€ to 2000€ | 288 | 19,1 |

| 2001€ to 2500€ | 201 | 13,3 |

| 2501€ to 3000€ | 143 | 9,5 |

| Over 3000€ | 198 | 13,1 |

| Item | Standard Beta | SE | t-Value | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Planet-B Attitudes | → | Countries around the world should take action to address climate change. | .952 | |||

| → | Nature has great value which makes its conservation important for current and future generations. | .948 | .016 | 60.447 | *** | |

| → | Governments should take action on climate change. | .952 | .013 | 75.296 | *** | |

| → | Human activities are a major cause of climate change. | .928 | .018 | 51.955 | *** | |

| → | All citizens have a responsibility to act against climate change. | .908 | .020 | 47.875 | *** | |

| → | The balance of nature is very delicate and easily upset. | .874 | .021 | 41.875 | *** | |

| → | Plants and animals have as much right as humans to exist. | .884 | .021 | 43.532 | *** | |

| → | Humans are severely abusing the environment. | .829 | .024 | 35.996 | *** | |

| → | Nature has great value which makes its conservation important for current and future generations. | .833 | .024 | 36.594 | *** | |

| → | Sustainable tourism can enhance the personal development of visitors. | .832 | .023 | 36.466 | *** | |

| → | Climate change will harm me and my family. | .835 | .025 | 36.670 | *** | |

| → | When humans interfere with nature, it often produces disastrous consequences. | .710 | .029 | 25.942 | *** | |

| → | Sustainable tourism must avoid interfering with local habitat, flora and fauna. | .760 | .029 | 29.594 | *** | |

| → | The role of sustainable destination management goes beyond the economic function. | .750 | .027 | 28.826 | *** | |

| → | I am willing to sacrifice some of my comfort in order to stop climate change (e.g., by using more public transport, using less water, electricity and gas). | .844 | .023 | 37.756 | *** | |

| → | Sustainable tourism destinations must restrict the volume of visitors to preserve their cultural identity. | .659 | .032 | 22.823 | *** | |

| Environmental concern during trip | → | The environmental impact of the main means of transport and mobility at the destination. | .921 | |||

| → | The environmental impact of trip’s duration. | .846 | .029 | 32.938 | *** | |

| → | The environmental impact of the activities to be carried out (outings, visits, shows, etc.). | .888 | .026 | 36.077 | *** | |

| → | The accommodation has a label showing its environmental friendliness. | .858 | .028 | 34.263 | *** | |

| → | Plan departure times to reduce their environmental impact (e.g., by avoiding traffic jams, etc.). | .821 | .030 | 30.332 | *** | |

| Sustainable Consumption Behaviour | → | I give preference to products from organisations that pay their employees fairly. | .934 | |||

| → | I give preference to products from organisations that offer good conditions to their workers. | .953 | .019 | 52.571 | *** | |

| → | I give preference to organisations that care about working conditions throughout their supply chain. | .944 | .019 | 51.391 | *** | |

| → | I give preference to products that have a lower environmental impact. | .863 | .024 | 37.729 | *** | |

| Willingness to pay for Sustainable Destinations | → | I am willing to pay more to visit a destination that adopts sustainable practices. | .954 | |||

| → | I am willing to pay more for tourism services (hotels, restaurants, tours, etc.) in destinations that adopt sustainable practices. | .873 | .023 | 40.935 | *** | |

| → | I am willing to pay more to visit a destination that is more environmentally friendly. | .949 | .018 | 54.729 | *** | |

| Constructs’ convergent validity and reliability | CA | CR | MaxR(H) | AVE | ||

| No Planet-B Attitudes | .974 | 0.976 | 0.983 | 0.722 | ||

| Environmental concern during trip | .945 | 0.939 | 0.944 | 0.756 | ||

| Sustainable Consumption Behaviour | .951 | 0.976 | 0.965 | 0.957 | ||

| Willingness to pay for Sustainable Destinations | .948 | 0.947 | 0.957 | 0.947 | ||

| Model fit statistics: | X2/df=2.836; GFI=.905; NFI=.966; AGFI=.882; RMSEA=.053 | |||||

| AVE | MSV | ASV | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sustainable Consumption Behaviour | 0,849 | 0,561 | 0,447 | 0,921a | |||

| 2. No Planet-B Attitudes | 0,722 | 0,578 | 0,439 | 0,749 | 0,850 a | ||

| 3. Environmental Concern During Trip | 0,756 | 0,258 | 0,228 | 0,508 | 0,423 | 0,870 a | |

| 4. Willingness to pay for Sustainable Destinations | 0,858 | 0,578 | 0,449 | 0,722 | 0,760 | 0,498 | 0,926 a |

| Std. Beta | SE | t | p | R2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

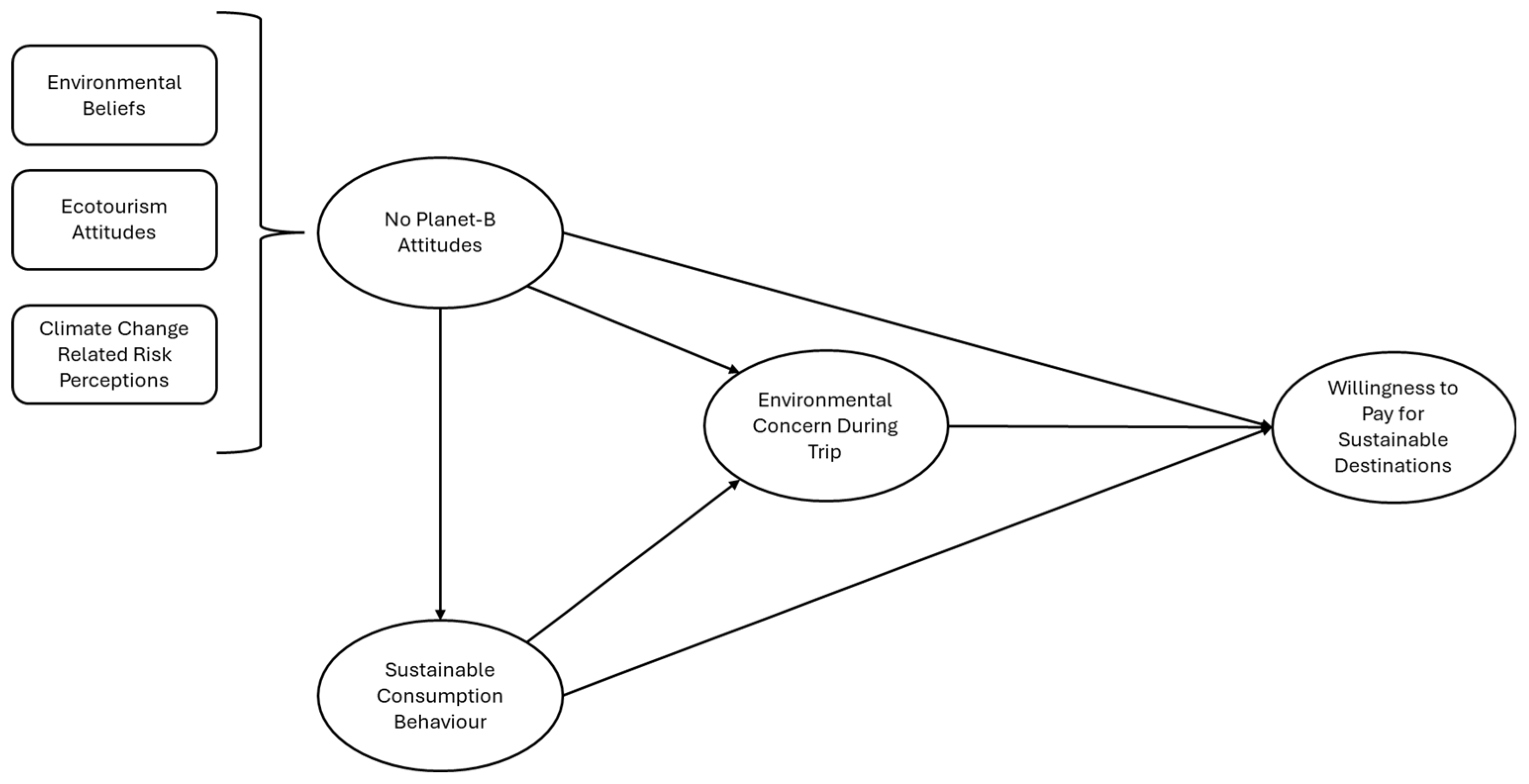

| No Planet-B Attitudes | → | Sustainable Consumption Behaviour | .740 | .028 | 26.735 | *** | .547 |

| No Planet-B Attitudes | → | Environmental Concern During Trip | .122 | .055 | 2.492 | .013 | .297 |

| Sustainable Consumption Behaviour | → | Environmental Concern During Trip | .449 | .055 | 9.021 | *** | |

| No Planet-B Attitudes | → | Willingness to pay for Sustainable Destinations | .425 | .038 | 11.539 | *** | .609 |

| Sustainable Consumption Behaviour | → | Willingness to pay for Sustainable Destinations | .361 | .041 | 9.149 | *** | |

| Environmental concern during trip | → | Willingness to pay for Sustainable Destinations | .082 | .028 | 2.750 | .006 | |

| Model fit statistics: X2/df = 2.2856; GFI = .923; NFI = .970; AGFI = 900; RMSEA = .050 | |||||||

| H1a | Willingness to pay for Sustainable Destinations is positively affected by Sustainable Consumption Behaviour. | Supported |

| H1b | Willingness to pay for Sustainable Destinations is positively affected by Environmental Concern During Trip. | Supported |

| H1c | Willingness to pay for Sustainable Destinations is positively affected by Environmental beliefs. | Supported |

| H1d | Willingness to pay for Sustainable Destinations is positively affected by Ecotourism Attitudes. | Supported |

| H1e | Willingness to pay for Sustainable Destinations is positively affected by Climate change-related risk perceptions. | Supported |

| H2a | Environmental Concern During Trip is positively affected by Sustainable Consumption Behaviour | Supported |

| H2b | Environmental Concern during trip is positively affected by Environmental Beliefs. | Supported |

| H2c | Environmental Concern During Trip is positively affected by Ecotourism Attitudes. | Supported |

| H2d | Environmental Concern During Trip is positively affected by Climate change-related risk perceptions. | Supported |

| H3a | Sustainable Consumption Behaviour is positively affected by Environmental Beliefs. | Supported |

| H3b | Sustainable Consumption Behaviour Destinations is positively affected by Ecotourism Attitudes. | Supported |

| H3c | Sustainable Consumption Behaviour is positively affected by Climate change-related risk perceptions. | Supported |

| Effects on Sustainable Consumption Behaviour | Direct | Indirect | Total |

| No Planet-B Attitudes | .740 | - | .740 |

| Effects on Environmental Concern During Trip | Direct | Indirect | Total |

| No Planet-B Attitudes | .122 | .332 | .507 |

| Sustainable Consumption Behaviour | .449 | - | .449 |

| Effects on Willingness to pay for Sustainable Destinations | Direct | Indirect | Total |

| No Planet-B Attitudes | .425 | .304 | .730 |

| Sustainable Consumption Behaviour | .361 | .037 | .398 |

| Environmental Concern During Trip | .082 | - | .082 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).