Submitted:

25 September 2024

Posted:

26 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Relationship between Autophagy and Obesity

3.2. Nutritional Interwentions for Autophagy Activation in Overweigth/obese Humans

3.2.1. Calorie Restriction; Intermittent Fasting

3.2.2. Mediterranean Diet (Met Diet)

3.2.3. Dietary Polyphenols

3.2.4. Dietary Fatty Acids

3.2.5. Diet Modifications

3.2.6. Protein Intake

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Obesity Federation. World Obesity Atlas 2024. London: World Obesity Federation, 2024. https://data.worldobesity.org/publications/.

- World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed: 29 June 2024).

- Purnell,J. Definitions, Classification, and Epidemiology of Obesity. Endotext 2023, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279167/.

- https://www.worldobesity.org/what-we-do/our-policy-priorities/obesity-as-a-disease (accessed: 28 August 2024).

- Li, X. Qi, L. Gene-Environment Interactions on Body Fat Distribution. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Jul 27;20(15):3690. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases. 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases#%7Etext=Noncommunicable.20diseases.20(NCDs).20kill.2041-.20and.20middle-income.

- Abarca-Gómez L., Abdeen Z. A., Hamid Z. A., et al. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 9 million children, adolescents, and adults. The Lancet . 2017;390(10113):2627–2642. [CrossRef]

- Lemieux I, Després, J.P. Metabolic syndrome: past, present and future. Nutrients. 2020; 12(11):3501.

- Fathi Dizaji B. The investigations of genetic determinants of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2018;12(5):783-789. [CrossRef]

- Pal, SC, Méndez-Sánchez N. Screening for MAFLD: who, when and how? Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2023;14. [CrossRef]

- Jakubek, P.; Pakula, B.; Rossmeisl, M.; et al. Autophagy alterations in obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: the evidence from human studies. Intern Emerg Med 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klionsky, D.J; Petroni, G; Amaravadi,R.K; Baehrecke, E.H; Ballabio, A; Boya, P. et al. Autophagy in major human diseases. EMBO J. 2021 ;40(19):e108863. [CrossRef]

- Hassanpour, M; Rahbarghazi, R; Nouri, M; Aghamohammadzadeh, N; Safaei, N; Ahmadi, M. Role of autophagy in atherosclerosis: foe or friend? J Inflamm (Lond). 2019;16:8. [CrossRef]

- Soussi, H.; Clément, K.; Dugail, I. Adipose tissue autophagy status in obesity: Expression and flux--two faces of the picture. Autophagy. 2016;12(3):588-589. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Mariman, E.; Roumans, N.; Vink, R.G.; Goossens, G.H.; Blaak, E.E. et al. Adipose tissue autophagy related gene expression is associated with glucometabolic status in human obesity. Adipocyte. 2018;7(1):12-19. [CrossRef]

- Klionsky, D.J.; Petroni, G.; Amaravadi, R.K.; Baehrecke, E.H.; Ballabio, A.; Boya, P. et al. Autophagy in major human diseases. EMBO J. 2021; 40(19):e108863. [CrossRef]

- Gatica, D.; Chiong, M.; Lavandero, S.; Klionsky, D.J. Molecular mechanisms of autophagy in the cardiovascular system. Circ Res. 2015;116(3):456-467. [CrossRef]

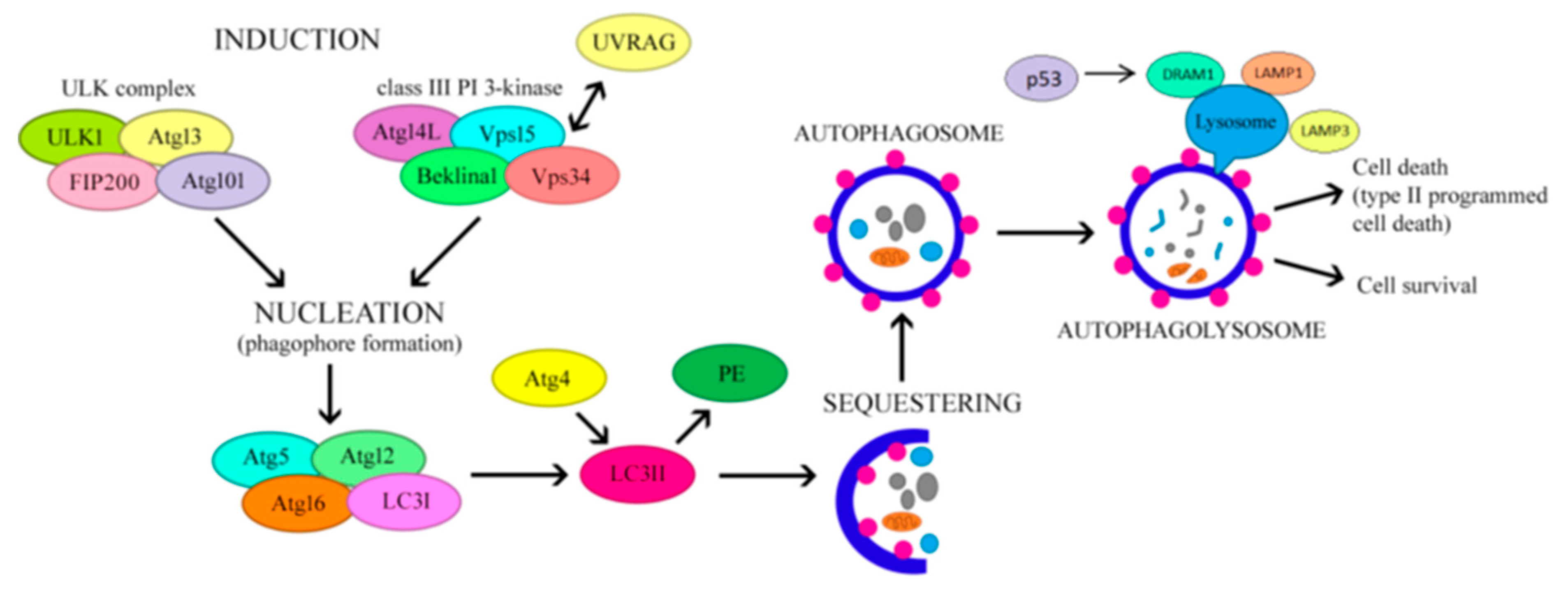

- Nishimura, T.; Tooze, S.A. Emerging roles of ATG proteins and membrane lipids in autophagosome formation. Cell Discov. 2020; 6(1):32. [CrossRef]

- Nussenzweig, S.C.; Verma, S.; Finkel, T. The role of autophagy in vascular biology. Circ Res. 2015;116(3):480-488. [CrossRef]

- Hassanpour, M.; Rahbarghazi, R.; Nouri, M.; Aghamohammadzadeh, N.; Safaei, N.; Ahmadi, M. Role of autophagy in atherosclerosis: foe or friend? J Inflamm (Lond). 2019;16:8. [CrossRef]

- Klionsky, D.J,; Abdelmohsen, K.; Abe, A.; Abedin, M.J.; Abeliovich, H.; Acevedo Arozena, A.; Adachi, H.; Adams, C.; Adams, P.D.; Adeli, K.; Adhihetty, P.J.; Adler, S.G.; Agam, G.; Agarwal, R.; Aghi, M.K.; Agnello, M. et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (3rd edition) Autophagy. 2016;12:1–222.

- Terasawa, K.; Tomabechi ,Y.; Ikeda, M.; Ehara, H.; Kukimoto-Niino ,M.; Wakiyama, M.; Podyma-Inoue, K.A.; Rajapakshe, A.R.; Watabe, T.; Shirouzu, M.; Hara-Yokoyama, M. Lysosome-associated membrane proteins-1 and -2 (LAMP-1 and LAMP-2) assemble via distinct modes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016 Oct 21;479(3):489-495. Epub 2016 Sep 20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, B.Z.; Han, B.Z.; Zeng, Y.X.; Su, D.F.; Liu, C. The roles of macrophage autophagy in atherosclerosis. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2016;37(2):150-156. [CrossRef]

- Hou, K.; Li, S.; Zhang, M.; Qin, X. Caveolin-1 in autophagy: A potential therapeutic target in atherosclerosis. Clin Chim Acta. 2021;513:25-33. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Huang. C.; Xu, C.; Xie, L., Liang, J.J.; Liu. L, et al. Caveolin-1 regulates human trabecular meshwork cell adhesion, endocytosis, and autophagy. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120(8):13382-13391. [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Yang, X.; Jia, X.; Rong, Y.; Chen, L.; Zeng, T. et al. CAV1-CAVIN1-LC3B-mediated autophagy regulates high glucose-stimulated LDL transcytosis. Autophagy. 2020;16(6):1111-1129. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Nie, S.D.; Qu, M.L.; Zhou, D.; Wu, L.Y.; Shi, X.J. et al. The autophagic degradation of Cav-1 contributes to PA-induced apoptosis and inflammation of astrocytes. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(7). [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chan, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Ho, IHT.; Zhang, X. et al. The phytochemical polydatin ameliorates non-alcoholic steatohepatitis by restoring lysosomal function and autophagic flux. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23(6):4290-4300. [CrossRef]

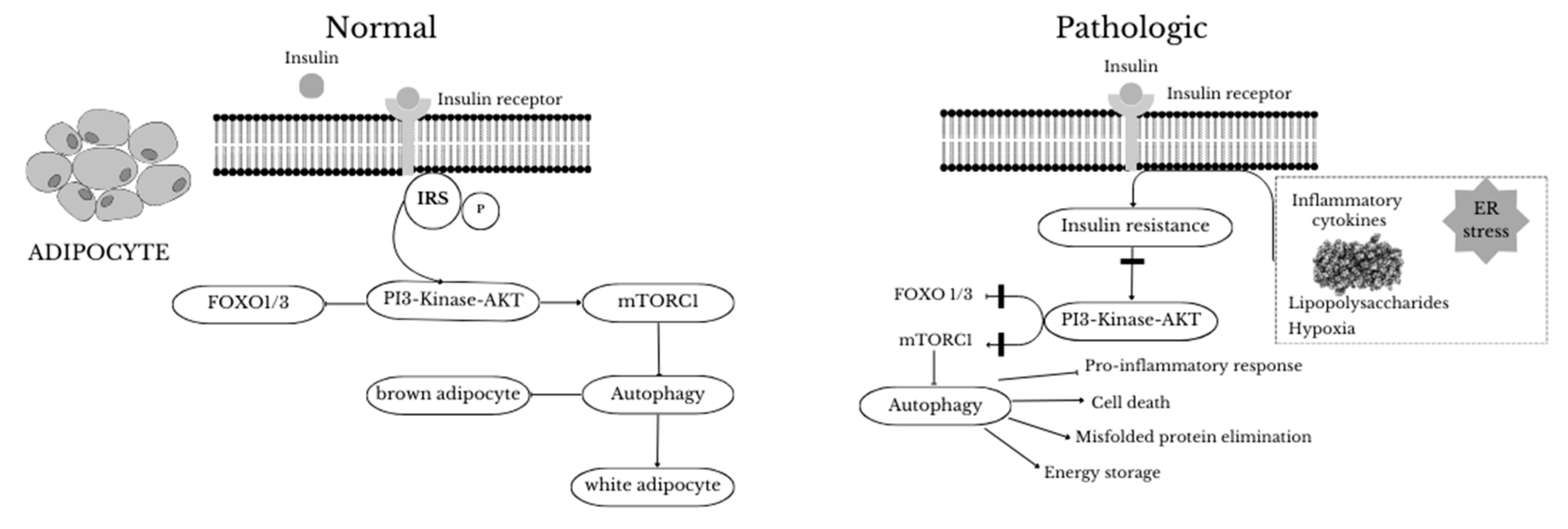

- Clemente-Postigo, M.; Tinahones, A.; Bekay, R.; Malagón, M.M.; Tinahones, F.J. The Role of Autophagy in White Adipose Tissue Function: Implications for Metabolic Health. Metabolites. 2020;10(5). [CrossRef]

- Soussi, H.; Clément, K.; Dugail, I. Adipose tissue autophagy status in obesity: Expression and flux--two faces of the picture. Autophagy. 2016;12(3):588-589. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sowers, J.R.; Ren, J. Targeting autophagy in obesity: from pathophysiology to management. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018 Jun;14(6):356-376. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Vicario, C.; Alcaraz-Quiles, J.; García-Alonso, V.; Rius, B.; Hwang, S.H., Titos, E.; Lopategi, A.; Hammock, B.D.; Arroyo, V.; Clària J. Inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase modulates inflammation and autophagy in obese adipose tissue and liver: Role for omega-3 epoxides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:536–541. [CrossRef]

- Yasuda-Yamahara, M.; Kume, S.; Yamahara, K.; Nakazawa, J.; Chin-Kanasaki, M.; Araki, H.; Araki S.; Koya D.; Haneda, M.; Ugi, S. et al. Lamp-2 deficiency prevents high-fat diet-induced obese diabetes via enhancing energy expenditure. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015;465:249–255. [CrossRef]

- Sekar, M.; Thirumurugan, K. Autophagic Regulation of Adipogenesis Through TP53INP2: Insights from In Silico and In Vitro Analysis. Mol Biotechnol. 2024 May;66(5):1188-1205. Epub 2024 Jan 18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, G.; Xu, M.; Cui, Y.; He, W.; Zeng ,H.; Zeng, T.; Cheng, R.; Li, X. Caspase-1 Deficiency Modulates Adipogenesis through Atg7-Mediated Autophagy: An Inflammatory-Independent Mechanism. Biomolecules. 2024 Apr 20;14(4):501. PMCID: PMC11048440. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Barrado, M.J., Iglesias-Osma, M.C.; Pérez-García, E.; Carrero, S.; Blanco, E.J.; Carretero-Hernández, M.; Carretero, J. Role of Flavonoids in The Interactions among Obesity, Inflammation, and Autophagy. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2020 Oct 26;13(11):342. PMCID: PMC7692407. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambele, M.A.; Dhanraj, P.; Giles,R.; Pepper, M.S. Adipogenesis: A Complex Interplay of Multiple Molecular Determinants and Pathways. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Jun 16;21(12):4283. PMCID: PMC7349855. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; Pires, K.M.; Ferhat, M.; Chaurasia, B.; Buffolo, M.A.; Smalling, R. et al. Autophagy Ablation in Adipocytes Induces Insulin Resistance and Reveals Roles for Lipid Peroxide and Nrf2 Signaling in Adipose-Liver Crosstalk. Cell Rep. 2018;25(7):1708-1717.e5. [CrossRef]

- Kosacka, J.; Kern, M.; Klöting, N.; Paeschke, S; Rudich, A.; Haim, Y. et al. Autophagy in adipose tissue of patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;409:21-32. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; He, Y.; Okutsu, M.; Ong, L.C.; Jin, Y. Zheng, L. et al. Autophagy is involved in adipogenic differentiation by repressesing proteasome-dependent PPARγ2 degradation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;305(4). [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wang, D.; Zhao, W.; Xu, L. Deciphering the Roles of PPARγ in Adipocytes via Dynamic Change of Transcription Complex. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018 Aug 21;9:473. PMCID: PMC6110914. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vegiopoulos A, Rohm M, Herzig S. Adipose tissue: between the extremes. EMBO J. 2017. 36:1999–2017.

- Wang, S.; Lin, Y.; Gao, L.; Yang, Z.; Lin, J.; Ren, S.; Li, F.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Dong, Z.; Sun, P.; Wu, B. PPAR-γ integrates obesity and adipocyte clock through epigenetic regulation of Bmal1. Theranostics. 2022 Jan 16;12(4):1589-1606. PMCID: PMC8825584. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimori, Ko. Prostaglandin D2 and F2α as Regulators of Adipogenesis and Obesity. Biol and Pharmacol. 2022;45:8.

- Armani A, Berry A, Cirulli F, Caprio M. Molecular mechanisms underlying metabolic syndrome: the expanding role of the adipocyte. FASEB J. (2017) 31:4240–55.

- Ferhat, M.; Funai, K.; Boudina, S. Autophagy in Adipose Tissue Physiology and Pathophysiology. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2019;31(6):487-501. [CrossRef]

- Pietrocola, F.; Bravo-San Pedro, J.M. Targeting Autophagy to Counteract Obesity-Associated Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021 Jan 12;10(1):102. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichimiya, T.; Yamakawa, T.; Hirano, T.; Yokoyama, Y.; Hayashi, Y.; Hirayama, D.; Wagatsuma, K.; Itoi, T.; Nakase, H. Autophagy and Autophagy-Related Diseases: A Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Nov 26;21(23):8974. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovsan, J.; Blüher, M.; Tarnovscki, T.; Klöting, N.; Kirshtein, B.; Madar, L. et al. Altered autophagy in human adipose tissues in obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(2). [CrossRef]

- Xu Q, Mariman ECM, Roumans NJT, Vink RG, Goossens GH, Blaak EE, et al. Adipose tissue autophagy related gene expression is associated with glucometabolic status in human obesity. Adipocyte. 2018;7(1):12-19. [CrossRef]

- Chipurupalli, S.; Samavedam, U.; Robinson, N. Crosstalk Between ER Stress, Autophagy and Inflammation. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021 Nov 5;8:758311. PMCID: PMC8602556. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Cuervo, A.M. Lipophagy: connecting autophagy and lipid metabolism. Int J Cell Biol. 2012;2012:282041. [CrossRef]

- Tokarz, V. L.; MacDonald, P. E.; Klip, A. The cell biology of systemic insulin function. J. Cell Biol. 2018:217, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Hemmings, B.A.; Restuccia, D.F. PI3K-PKB/Akt pathway. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4(9). [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.H.; Cho, M.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Kwon, M.S.; Peak, J.J.; Kang, S.W. et al. Impaired macrophage autophagy induces systemic insulin resistance in obesity. Oncotarget. 2016;7(24):35577-35591. [CrossRef]

- Frendo-Cumbo, S.; Tokarz, V.L.; Bilan, P.J.; Brumell, J.H.; Klip, A. Communication Between Autophagy and Insulin Action: At the Crux of Insulin Action-Insulin Resistance? Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9. [CrossRef]

- Maixner, N.; Bechor, S.; Vershinin, Z.; Pecht, T.; Goldstein, N.; Haim, Y. et al. Transcriptional Dysregulation of Adipose Tissue Autophagy in Obesity. Physiology (Bethesda). 2016;31(4):270-282. [CrossRef]

- Maixner, N.; Pecht, T.; Haim, Y.; Chalifa-Caspi, V.; Goldstein, N.; Tarnovscki ,T. et al. A TRAIL-TL1A Paracrine Network Involving Adipocytes, Macrophages, and Lymphocytes Induces Adipose Tissue Dysfunction Downstream of E2F1 in Human Obesity. Diabetes. 2020;69(11):2310-2323. [CrossRef]

- Haim, Y.; Blüuher, M.; Slutsky, N.; Goldstein, N.; Klöting, N.; Harman-Boehm, I. et al. Elevated autophagy gene expression in adipose tissue of obese humans: A potential non-cell-cycle-dependent function of E2F1. Autophagy. 2015;11(11):2074-2088. [CrossRef]

- Böni-Schnetzler, M.; Häuselmann, S.P.; Dalmas, E.; Meier, D.T.; Thienel, C.; Traub, S. et al. β Cell-Specific Deletion of the IL-1 Receptor Antagonist Impairs β Cell Proliferation and Insulin Secretion. Cell Rep. 2018;22(7):1774-1786. [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.; Martinez-Lopez, N.; Otten, E.G.; Carroll, B.; Maetzel, D.; Singh, R. et al. Autophagy, lipophagy and lysosomal lipid storage disorders. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1861(4):269-284. [CrossRef]

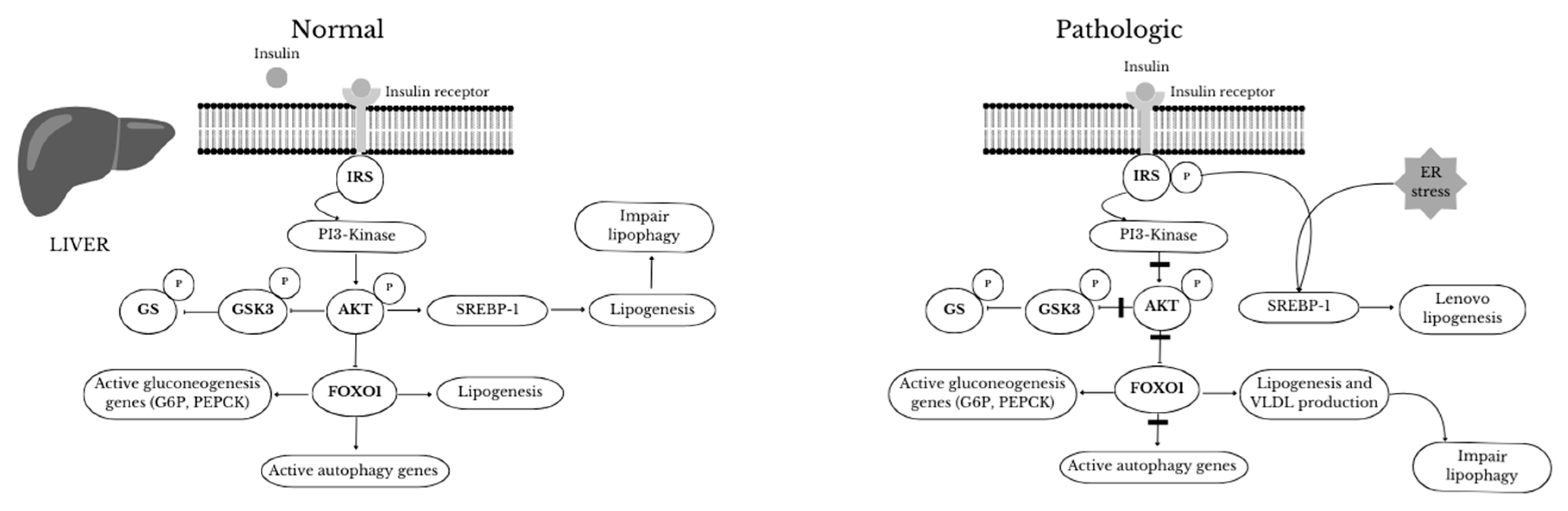

- Qian,Q.; Zhang, Z.; Orwig, A.; Chen, S.; Ding, W.X.; Xu, Y. et al. S-Nitrosoglutathione Reductase Dysfunction Contributes to Obesity-Associated Hepatic Insulin Resistance via Regulating Autophagy. Diabetes. 2018;67(2):193-207. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Kaushik, S.; Wang, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Novak, I.; Komatsu, M. et al. Autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Nature. 2009;458(7242):1131-1135. [CrossRef]

- Dann, S.G.; Selvaraj, A.; Thomas, G. mTOR Complex1-S6K1 signaling: at the crossroads of obesity, diabetes and cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13(6):252-259. [CrossRef]

- Yang L, Li P, Fu S, Calay ES, Hotamisligil GS. Defective hepatic autophagy in obesity promotes ER stress and causes insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2010;11(6):467-478. [CrossRef]

- Yoshizaki,T.; Kusunoki, C.; Kondo, M.; Yasuda, M.; Kume, S.; Morino, K. et al. Autophagy regulates inflammation in adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;417(1):352-357. [CrossRef]

- Ezaki, J.; Matsumoto, N.; Takeda-Ezaki, M.; Komatsu, M.; Takahashi, K.; Hiraoka, Y. et al. Liver autophagy contributes to the maintenance of blood glucose and amino acid levels. Autophagy. 2011;7(7):727-736. [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, S.; Perozzo, R.; Schmid, I.; Ziemiecki, A.; Schaffner, T.; Scapozza, L. et al. Calpain-mediated cleavage of Atg5 switches autophagy to apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8(10):1124-1132. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Jeong, Y.T.; Oh, H.; Kim,S.H.; Cho, J.M.; Kim, Y.N. et al. Autophagy deficiency leads to protection from obesity and insulin resistance by inducing Fgf21 as a mitokine. Nat Med. 2013;19(1):83-92. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Han, J.; Cao, S.Y.; Hong, T.; Zhuo, D.; Shi, J. et al. Hepatic autophagy is suppressed in the presence of insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia: inhibition of FoxO1-dependent expression of key autophagy genes by insulin. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(45):31484-31492. [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.; Lithgow, G.J.; Link, W. Long live FOXO: unraveling the role of FOXO proteins in aging and longevity. Aging Cell. 2016;15(2):196-207. [CrossRef]

- Fernández ÁF, Bárcena C, Martínez-García GG, Tamargo-Gómez I, Suárez MF, Pietrocola F, et al. Autophagy couteracts weight gain, lipotoxicity and pancreatic β-cell death upon hypercaloric pro-diabetic regimens. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(8). [CrossRef]

- Park HW, Park H, Semple IA, Jang I, Ro SH, Kim M, et al. Pharmacological correction of obesity-induced autophagy arrest using calcium channel blockers. Nat Commun. 2014;5. [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez A, Mayoral R, Agra N, Valdecantos MP, Pardo V, Miquilena-Colina ME, et al. Impaired autophagic flux is associated with increased endoplasmic reticulum stress during the development of NAFLD. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5(4):e1179. [CrossRef]

- Meng Q, Cai D. Defective hypothalamic autophagy directs the central pathogenesis of obesity via the IkappaB kinase beta (IKKbeta)/NF-kappaB pathway. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(37):32324-32332. [CrossRef]

- Yamahara K, Kume S, Koya D, Tanaka Y, Morita Y, Chin-Kanasaki M, et al. Obesity-mediated autophagy insufficiency exacerbates proteinuria-induced tubulointerstitial lesions. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(11):1769-1781. [CrossRef]

- Öst A, Svensson K, Ruishalme I, Brännmark C, Franck N, Krook H, et al. Attenuated mTOR signaling and enhanced autophagy in adipocytes from obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Mol Med. 2010;16(7-8):235-246.

- Bagherniya M, Butler AE, Barreto GE, Sahebkar A. The effect of fasting or calorie restriction on autophagy induction: A review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev. 2018;47:183-197. [CrossRef]

- Mei S, Ni HM, Manley S, Bockus A, Kassel KM, Luyendyk JP, et al. Differential roles of unsaturated and saturated fatty acids on autophagy and apoptosis in hepatocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;339(2):487-498. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Dou X, Ning H, Song Q, Wei W, Zhang X, et al. Sirtuin 3 acts as a negative regulator of autophagy dictating hepatocyte susceptibility to lipotoxicity. Hepatology. 2017;66(3):936-952. [CrossRef]

- de Luxán-Delgado B, Potes Y, Rubio-González A, Caballero B, Solano JJ, Fernández-Fernández M, et al. Melatonin reduces endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy in liver of leptin-deficient mice. J Pineal Res. 2016;61(1):108-123. [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Postigo, M.; Tinahones ,A.; El Bekay, R.; Malagón, M.M,; Tinahones, F.J. The Role of Autophagy in White Adipose Tissue Function: Implications for Metabolic Health. Metabolites. 2020 Apr 30;10(5):179. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Q, Mariman ECM, Roumans NJT, Vink RG, Goossens GH, Blaak EE, Jocken JWE. Adipose tissue autophagy related gene expression is associated with glucometabolic status in human obesity. Adipocyte. 2018 Jan 2;7(1):12-19. Epub 2018 Feb 5. PMCID: PMC5915036. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuñez CE, Rodrigues VS, Gomes FS, Moura RF, Victorio SC, Bombassaro B, Chaim EA, Pareja JC, Geloneze B, Velloso LA, Araujo EP. Defective regulation of adipose tissue autophagy in obesity. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013 Nov;37(11):1473-80. Epub 2013 Mar 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu Q, Mariman ECM, Roumans NJT, Vink RG, Goossens GH, Blaak EE, Jocken JWE. Adipose tissue autophagy related gene expression is associated with glucometabolic status in human obesity. Adipocyte. 2018 Jan 2;7(1):12-19. Epub 2018 Feb 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung KW, Chung HY. The Effects of Calorie Restriction on Autophagy: Role on Aging Intervention. Nutrients. 2019 Dec 2;11(12):2923. PMCID: PMC6950580. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Dietetics and Nutrition Terminology (IDNT) reference manual : standardized language for the nutrition care proces. 2011.

- He, C. et al. Exercise- induced BCL2-regulated autophagy is required for muscle glucose homeostasis. Nature 2012; 481, 511–515.

- Alrushud, A. S., Rushton, A. B., Kanavaki, A. M. & Greig, C. A. Effect of physical activity and dietary restriction interventions on weight loss and the musculoskeletal function of overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and mixed method data synthesis. BMJ Open 2017; 7, e014537.

- Halling, J. F. & Pilegaard, H. Autophagy- dependent beneficial effects of exercise. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2017; 7, a029777.

- Shabkhizan R, Haiaty S, Moslehian MS, Bazmani A, Sadeghsoltani F, Saghaei Bagheri H, Rahbarghazi R, Sakhinia E. The Beneficial and Adverse Effects of Autophagic Response to Caloric Restriction and Fasting. Adv Nutr. 2023 Sep;14(5):1211-1225. Epub 2023 Jul 30. PMCID: PMC10509423. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun L., Xiong H., Chen L., Dai X., Yan X., Wu Y., et al. Deacetylation of ATG4B promotes autophagy initiation under starvation. Sci. Adv. 2022;8(31):eabo0412. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary R., Liu B., Bensalem J., Sargeant T.J., Page A.J., Wittert G.A., et al. Intermittent fasting activates markers of autophagy in mouse liver, but not muscle from mouse or humans. Nutrition. 2022;101:111662. [CrossRef]

- Noda N.N., Fujioka Y. Atg1 family kinases in autophagy initiation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015;72(16):3083–3096. [CrossRef]

- Bagherniya M, Butler AE, Barreto GE, Sahebkar A. The effect of fasting or calorie restriction on autophagy induction: A review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev. 2018 Nov;47:183-197. Epub 2018 Aug 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocot AM, Wróblewska B. Nutritional strategies for autophagy activation and health consequences of autophagy impairment. Nutrition. 2022 Nov-Dec;103-104:111686. Epub 2022 Apr 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang L, Licastro D, Cava E, Veronese N, Spelta F, Rizza W, Bertozzi B, Villareal DT, Hotamisligil GS, Holloszy JO, Fontana L. Long-Term Calorie Restriction Enhances Cellular Quality-Control Processes in Human Skeletal Muscle. Cell Rep. 2016 Jan 26;14(3):422-428. 4; Epub 2016 Jun 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary R, Liu B, Bensalem J, Sargeant TJ, Page AJ, Wittert GA, Hutchison AT, Heilbronn LK. Intermittent fasting activates markers of autophagy in mouse liver, but not muscle from mouse or humans. Nutrition. 2022 Sep;101:111662. Epub 2022 Mar 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Sowers JR, Ren J. Targeting autophagy in obesity: from pathophysiology to management. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018 Jun;14(6):356-376. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song DK, Kim YW. Beneficial effects of intermittent fasting: a narrative review. Journal of Yeungnam Medical Science. 2023;40(1):4–11.

- Kim KH, Lee MS. Autophagy--a key player in cellular and body metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014 Jun;10(6):322-37. Epub 2014 Mar 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitada M, Kume S, Takeda-Watanabe A, Tsuda S, Kanasaki K, Koya D. Calorie restriction in overweight males ameliorates obesity-related metabolic alterations and cellular adaptations through anti-aging effects, possibly including AMPK and SIRT1 activation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013 Oct;1830(10):4820-7.

- Hanningan, A.; Gorski,S. Macroautophagy. Autophagy.2009, 5; 140-151.

- Mariani S, di Giorgio MR, Martini P, Persichetti A, Barbaro G, Basciani S, Contini S, Poggiogalle E, Sarnicola A, Genco A, Lubrano C, Rosano A, Donini LM, Lenzi A, Gnessi L. Inverse Association of Circulating SIRT1 and Adiposity: A Study on Underweight, Normal Weight, and Obese Patients. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018 Aug 7;9:449. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baeken MW. Sirtuins and their influence on autophagy. J Cell Biochem. 2023 Feb 6. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu C, Ji L, Hu J, Zhao Y, Johnston LJ, Zhang X, Ma X. Functional Amino Acids and Autophagy: Diverse Signal Transduction and Application. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Oct 22;22(21):11427. PMCID: PMC8592284. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, S.K.; Singh, A.; Saini, M.; Gonzalez-Freire, M.; Leeuwenburgh, C.; Anton, S.D. Time-Restricted Eating Regimen Differentially Affects Circulatory miRNA Expression in Older Overweight Adults. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1843. [CrossRef]

- Zachari M, Ganley IG. The mammalian ULK1 complex and autophagy initiation. Essays Biochem. 2017 Dec 12;61(6):585-596. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega MA, Fraile-Martinez O, de Leon-Oliva D, Boaru DL, Lopez-Gonzalez L, García-Montero C, Alvarez-Mon MA, Guijarro LG, Torres-Carranza D, Saez MA, Diaz-Pedrero R, Albillos A, Alvarez-Mon M. Autophagy in Its (Proper) Context: Molecular Basis, Biological Relevance, Pharmacological Modulation, and Lifestyle Medicine. Int J Biol Sci. 2024 Apr 22;20(7):2532-2554. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sbai O, Torrisi F, Fabrizio FP, Rabbeni G, Perrone L. Effect of the Mediterranean Diet (MeDi) on the Progression of Retinal Disease: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2024; 16(18):3169. [CrossRef]

- García-Montero C, Fraile-Martínez O, Gómez-Lahoz AM, Pekarek L, Castellanos AJ, Noguerales-Fraguas F, et al. Nutritional components in western diet versus mediterranean diet at the gut microbiota-immune system interplay. implications for health and disease. Nutrients. 2021;13(2):1–53.

- Franco GA, Interdonato L, Cordaro M, Cuzzocrea S, Di Paola R. Bioactive Compounds of the Mediterranean Diet as Nutritional Support to Fight Neurodegenerative Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Apr 15;24(8):7318. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lorenzo C, Colombo F, Biella S, Stockley C, Restani P. Polyphenols and Human Health: The Role of Bioavailability. Nutrients. 2021 Jan 19;13(1):273. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey KB, Rizvi SI. Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2009 Nov-Dec;2(5):270-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokal, A; Stocerz K, ; Olczyk, P.; Kadela-Tomanek, M. Therapeutic potential of flavonoids used in traditional Chinese medicine – a comparative study of galangin, kaempferol, chrysin and fisetin. AAMS. 2024,78.

- Domonese N, Di Bella G, Cusumano C, Parisi A, Tagliaferri F, Ciriminna S, Barbagallo M. Mediterranean diet in the management and prevention of obesity. Exp Gerontol. 2023 Apr;174:112121. Epub 2023 Feb 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brimson JM, Prasanth MI, Malar DS, Thitilertdecha P, Kabra A, Tencomnao T, Prasansuklab A. Plant Polyphenols for Aging Health: Implication from Their Autophagy Modulating Properties in Age-Associated Diseases. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2021 Sep 27;14(10):982. [PubMed]

- Osorio-Conles Ó, Olbeyra R, Moizé V, Ibarzabal A, Giró O, Viaplana J, Jiménez A, Vidal J, de Hollanda A. Positive Effects of a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Almonds on Female Adipose Tissue Biology in Severe Obesity. Nutrients. 2022 Jun 24;14(13):2617. [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Quan, W., Zeng, M., Wang, Z., Chen, Q., Chen, J., Christian, M.; He, Z. . Regulation of autophagy by plant-based polyphenols: A critical review of current advances in glucolipid metabolic diseases and food industry applications. Food Frontiers.2023 4, 1039–1067. [CrossRef]

- Most J, Warnke I, Boekschoten MV, Jocken JWE, de Groot P, Friedel A, Bendik I, Goossens GH, Blaak EE. The effects of polyphenol supplementation on adipose tissue morphology and gene expression in overweight and obese humans. Adipocyte. 2018;7(3):190-196. Epub 2018 May 22. [PubMed]

- Timmers S., Konings E., Bilet L., Houtkooper R.H., van de Weijer T., Goossens G.H., Hoeks J., van der Krieken S., Ryu D., Kersten S., et al. Calorie restriction-like effects of 30 days of resveratrol supplementation on energy metabolism and metabolic profile in obese humans. Cell Metab. 2011;14:612–622. [CrossRef]

- Konings E, Timmers S, Boekschoten MV, Goossens GH, Jocken JW, Afman LA, Müller M, Schrauwen P, Mariman EC, Blaak EE. The effects of 30 days resveratrol supplementation on adipose tissue morphology and gene expression patterns in obese men. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014 Mar;38(3):470-3. Epub 2013 Aug 20. [PubMed]

- ettembre C, Di Malta C, Polito VA, Garcia Arencibia M, Vetrini F, Erdin Set al.TFEB links autophagy to lysosomal biogenesis.Science 2011;332: 1429–1433.

- Moskot M, Montefusco S, Jakóbkiewicz-Banecka J, Mozolewski P, Węgrzyn A, Di Bernardo D, Węgrzyn G, Medina DL, Ballabio A, Gabig-Cimińska M. The phytoestrogen genistein modulates lysosomal metabolism and transcription factor EB (TFEB) activation. J Biol Chem. 2014 Jun 13;289(24):17054-69. Epub 2014 Apr 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widlund, A. L.; Baur, J.; A.; Vang O. mTOR: more targets of resveratrol? Expert Rev Mol Med 2013;15, e10.

- Zhang J, Chiu JF, Zhang HW, et al. Autophagic cell death induced by resveratrol depends on the Ca2+/AMPK/mTOR pathway in A549 cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;86(2):317–328. [CrossRef]

- Tian Y, Song W, Li D, Cai L, Zhao Y. Resveratrol As A Natural Regulator Of Autophagy For Prevention And Treatment Of Cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2019 Oct 17;12:8601-8609. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park D, Jeong H, Lee MN, Koh A, Kwon O, Yang YR, Noh J, Suh PG, Park H, Ryu SH. Resveratrol induces autophagy by directly inhibiting mTOR through ATP competition. Sci Rep. 2016 Feb 23;6:21772. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansur AP, Roggerio A, Goes MFS, Avakian SD, Leal DP, Maranhão RC, Strunz CMC. Serum concentrations and gene expression of sirtuin 1 in healthy and slightly overweight subjects after caloric restriction or resveratrol supplementation: A randomized trial. Int J Cardiol. 2017 Jan 15;227:788-794. Epub 2016 Oct 27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, C.M.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; McManus, R.; Hercberg, S.; Lairon, D.; Planells, R.; Roche, H.M. High dietary saturated fat intake accentuates obesity risk associated with the fat mass and obesity-associated gene in adults. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 824–831.

- Liu W, Zhu M, Gong M, Zheng W, Zeng X, Zheng Q, Li X, Fu F, Chen Y, Cheng J, Rao Z, Lu Y, Chen Y. Comparison of the Effects of Monounsaturated Fatty Acids and Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on Liver Lipid Disorders in Obese Mice. Nutrients. 2023 Jul 19;15(14):3200. PMCID: PMC10386220. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang,J.; Nie, D.Modulation autophagy by Fatty acids. In: Cell Death - Autophagy, Apoptosis and Necrosis. IntechOpen 2015.

- O'Rourke EJ, Kuballa P, Xavier R, Ruvkun G. ω-6 Polyunsaturated fatty acids extend life span through the activation of autophagy. Genes Dev. 2013 Feb 15;27(4):429-40. Epub 2013 Feb 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciesielska K, Gajewska M. Fatty Acids as Potent Modulators of Autophagy Activity in White Adipose Tissue. Biomolecules. 2023 Jan 30;13(2):255. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang B, Zhou Y, Wu M, Li X, Mai K, Ai Q. ω-6 Polyunsaturated fatty acids (linoleic acid) activate both autophagy and antioxidation in a synergistic feedback loop via TOR-dependent and TOR-independent signaling pathways. Cell Death Dis. 2020 Jul 30;11(7):607. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camargo A, Rangel-Zúñiga OA, Alcalá-Díaz J, Gomez-Delgado F, Delgado-Lista J, García-Carpintero S, Marín C, Almadén Y, Yubero-Serrano EM, López-Moreno J, Tinahones FJ, Pérez-Martínez P, Roche HM, López-Miranda J. Dietary fat may modulate adipose tissue homeostasis through the processes of autophagy and apoptosis. Eur J Nutr. 2017 Jun;56(4):1621-1628. Epub 2016 Mar 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viguerie N, Vidal H, Arner P, Holst C, Verdich C, Avizou S, Astrup A, Saris WH, Macdonald IA, Klimcakova E, Clément K, Martinez A, Hoffstedt J, Sørensen TI, Langin D; Nutrient-Gene Interactions in Human Obesity--Implications for Dietary Guideline (NUGENOB) project. Adipose tissue gene expression in obese subjects during low-fat and high-fat hypocaloric diets. Diabetologia. 2005 Jan;48(1):123-31. Epub 2004 Dec 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capel F, Viguerie N, Vega N, Dejean S, Arner P, Klimcakova E, Martinez JA, Saris WH, Holst C, Taylor M, Oppert JM, Sørensen TI, Clément K, Vidal H, Langin D. Contribution of energy restriction and macronutrient composition to changes in adipose tissue gene expression during dietary weight-loss programs in obese women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Nov;93(11):4315-22. Epub 2008 Sep 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanjani NA, Vafa M. Protein Restriction, Epigenetic Diet, Intermittent Fasting as New Approaches for Preventing Age-associated Diseases. Int J Prev Med. 2018 Jun 29;9:58. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu C, Markova M, Seebeck N, Loft A, Hornemann S, Gantert T, Kabisch S, Herz K, Loske J, Ost M, Coleman V, Klauschen F, Rosenthal A, Lange V, Machann J, Klaus S, Grune T, Herzig S, Pivovarova-Ramich O, Pfeiffer AFH. High-protein diet more effectively reduces hepatic fat than low-protein diet despite lower autophagy and FGF21 levels. Liver Int. 2020 Dec;40(12):2982-2997. Epub 2020 Jul 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soussi H, Reggio S, Alili R, Prado C, Mutel S, Pini M, Rouault C, Clément K, Dugail I. DAPK2 Downregulation Associates With Attenuated Adipocyte Autophagic Clearance in Human Obesity. Diabetes. 2015 Oct;64(10):3452-63. Epub 2015 Jun 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Dietary strategies | Model of Obesity | Parametr studies | Effect on Autophagy | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calorie restriction or Intermittent fasting |

Sceletal muscle of body fat-matched endurance athletes ; sceletal muscle of obese women; Obese human (subcutaneous, white adipose tissue |

Decreased mTOR signaling through reducing insulin and IGF-1 levels and increased the AMP/ATP ratio, which leads to the activation of AMPK as well as several other products involved in the stimulation of this process (ATG 5, ATG6, ATG7, ATG8, LC3-II, Beclin1, p62, SIRT1, LAMP2, ULK1 and ATG101) | Enhanced | [96,97,98,99,100] |

| Calorie restriction 25% for 7 weeks | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMNCs) of overweight male | Activated of AMPK and SIRT1 | Enhanced | [106] |

| Mediterranean Diet vs Mediterranean Diet with almonds |

Obese human (subcutaneous, white adipose tissue |

Increased expression of autophagy-related ATG 7 and ATG12 in VAT from the MDSA group, while ATG5 show non-significant trend (p=0.054) | Enhanced | [117] |

| Dietary polyphenols | Obese human (subcutaneous, white adipose tissue |

Activated cAMP, AMPK, MAPK, increased AKT, SIRT1, PI3K, Nrf2/HO-1, PINK1/Parkin, PPARδ genes expression | Enhanced | [118] |

| Epigallocatechin-3-gallate + resveratrol (280 mg +80 mg/d) vs placebo – 12 weeks | Obese human (subcutaneous, white adipose tissue |

Activated genes expression of ATP6V1A, ATP6V1H, CD68, HSL/LIPE, LAMP2, PI4K2A, UCP2, GAPDH | Enhanced | [119] |

| Resveratrol 150 mg once daily for 30 days | Obese men (sceletal muscle) | Activated AMPK, increased SIRT1 and PGC-1α protein levels | Enhanced | [120] |

| Resveratrol 150 mg once daily for 30 days | Obese men (sceletal muscle) | Activated TFEB (transcriptional factor EB) expression Inhibited mTOR activity |

Enhanced | [121] |

| Resveratrol (500 mg/d) vs Calorie restriction (1000 kcal/d) | Overweight human (blood) | Resveratrol and caloric restriction increased significantly serum concentrations of SIRT1 proteins | Enhanced | [128] |

| Four diets for 12 weeks: a high-saturated fatty acid diet (HSFA), a high-monounsaturated fatty acid diet (HMUFA), and two low-fat, high-complex carbohydrate diets supplemented with long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (LFHCC n-3) or placebo (LFHCC). | Obese human (subcutaneous) white adipose tissue |

Significantly increased expression of autophagy-related BECN1 and ATG7 genes after the HMUFA diet; increased the expression of the apoptosis-related CASP3 gene after the LFHCC and LFHCC n-3 diets. Expression of other autophagy markers, LC3, LAMP2, and ULK1, tended to increase after the consumption of the LFHCC n-3 diet. | Enhanced | [135] |

| Low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet (LF) vs moderate-fat, low-carbohydrate diet (MF) for 10 weeks | Obese human (subcutaneous) white adipose tissue |

Expression FABP4, SIRT3, NR3C1, GABARAPL2, and FNTA genes was 15–65% higher in the MF than the LF. | Enhanced in MF diet vs LF | [136,137] |

| Hypocaloric diet (1500-1600 kcal/day) and low protein (10%) vs Hypocaloric (1500-1600 kcal/day) and high protein (30E%) for 3 weeks prior bariatric surgery | Liver sample collected during surgery | Significantly elevated autophagy flux and FGF21 levels in liver in patients in LP diet versus HP | Enhanced in LP diet vs HP | [138] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).