1. Introduction

An estimated 2.2 million individuals in the United States are living with Hepatitis C (HCV) and the prevalence has remained largely unchanged since the 2013-2016 time period [

1]. The emergence of Interferon-free direct-acting Anti-virals (DAAs) provided an efficacious and well tolerated treatment for HCV. After 8-12 weeks of treatment, DAA combinations clinically cure HCV for more than 95 percent of individuals with chronic HCV infection. Despite this, data shows that less than 50% of patients diagnosed with HCV were treated with DAAs from 2014 to 2020 [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Furthermore, a meta-analysis of 65 studies reported an overall treatment rate for HCV RNA positive patients of 41% (range 20%-51%) with 75% of the treatment studies performed in United States populations [

7]. With respect to improvements over time, Jaing et al 2023 reported improvement from 3% in 2011 (IFN era) to 54% in 2018 due primarily to universal coverage in Canada for all DAAs [

8,

9]. Thus, based on the literature, it is apparent that despite the widespread availability of DAAs, achieving treatment of more than half of the individuals who are identified as HCV infected (ie PCR positive) remains an elusive goal.

The literature suggests multiple impediments to care. One of the most effective is the use of a multifaceted team approach (10-15). This would include both enhanced personal interventions coupled with the use of electronic medical records to identify and contact potential candidates for therapy. In one study, these resource intensive interventions mediated primarily through primary care settings resulted in an improvement from 65% to 76% (12). An even more complex issue that is present in the literature, is that many individuals with HCV, have socioeconomic barriers such as drug additions, engagement in opioid agonist therapy, incarceration, poor or no insurance, flexible living conditions and complications related to reliable communication. While these issues are clearly present and addressable, there is a need to address the more critical issue of treatment after the first visit to either gastroenterology or infectious disease with a diagnosis of suspected HCV.

To achieve a more effective elimination of HCV, evidence-based information is needed to identify areas where intervention may be implemented to increase the treatment rates to above 50%. Given the fact that HCV is twice as likely to be in African American as non-AA patients, studies in clinics such as ours which see predominately AA patients should be useful. In addition, the location of our clinics in an Urban Medical Center which serves a population of socioeconomically challenged individuals may also provide clues to strategies for improved treatment rates. The primary objective of this study was to identify patients who were not treated after a visit to a GI clinic and compare them to patients who were treated. The hypothesis was that after identifying potential reasons for the failure to treat, interventions could then be made using evidence-based data. The 2019 patients were seen at least once in Gastroenterology (GI) or Infectious Disease (ID) clinics. They were evaluated for characteristics that were different between HCV patients who were treated and those not treated.

2. Methods

The electronic medical records of a large urban and predominately African American clinic population were searched for an ICD-10 billing code of hepatitis C virus visits in 2019. Data was collected under an institutional IRB approved project from 2019 HCV patient EMR charts including demographics, laboratory studies, and treatment history. If patients were seen in the last months of 2019, we used the 2020 records to assess a 6 month follow up visits for all patients to establish a baseline time frame for treatment of at least 6 months. We compared characteristics of patients who were treated with patients who were not treated using ANOVA or Chi-Squared assays. Fibrosis at the initial visit was based on laboratory data and online calculators using both Aspartate transaminase (AST) to Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) and Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4; which includes AST, Alanine transaminase (ALT), platelets and age of the patient). ZIP codes were used to provide median income data for patients based on data for 2020 income via searching INCOME BY ZIPCODE by CUBIT Planning Inc information on their website. Insurance information at the time of the initial visit was obtained from the medical records and classified as Medicare, Medicaid (if supplementing Medicare in the context of Medicaid advantage plans, it was defined as Medicaid) or Commercial. We also used the EMR to determine the number of 2019 visits each patient had prior to starting treatment. We did not assess whether treated patients had previous visits in 2018 and thus may have underestimated the number of visits prior to treatment for some patients. With respect to treatment, we defined success as treatment initiation within 6 months of the initial visit (i.e. through July 2020 for patients who had their first visit in December 2019). The analysis was performed using SAS JMP statistical software.

3. Results

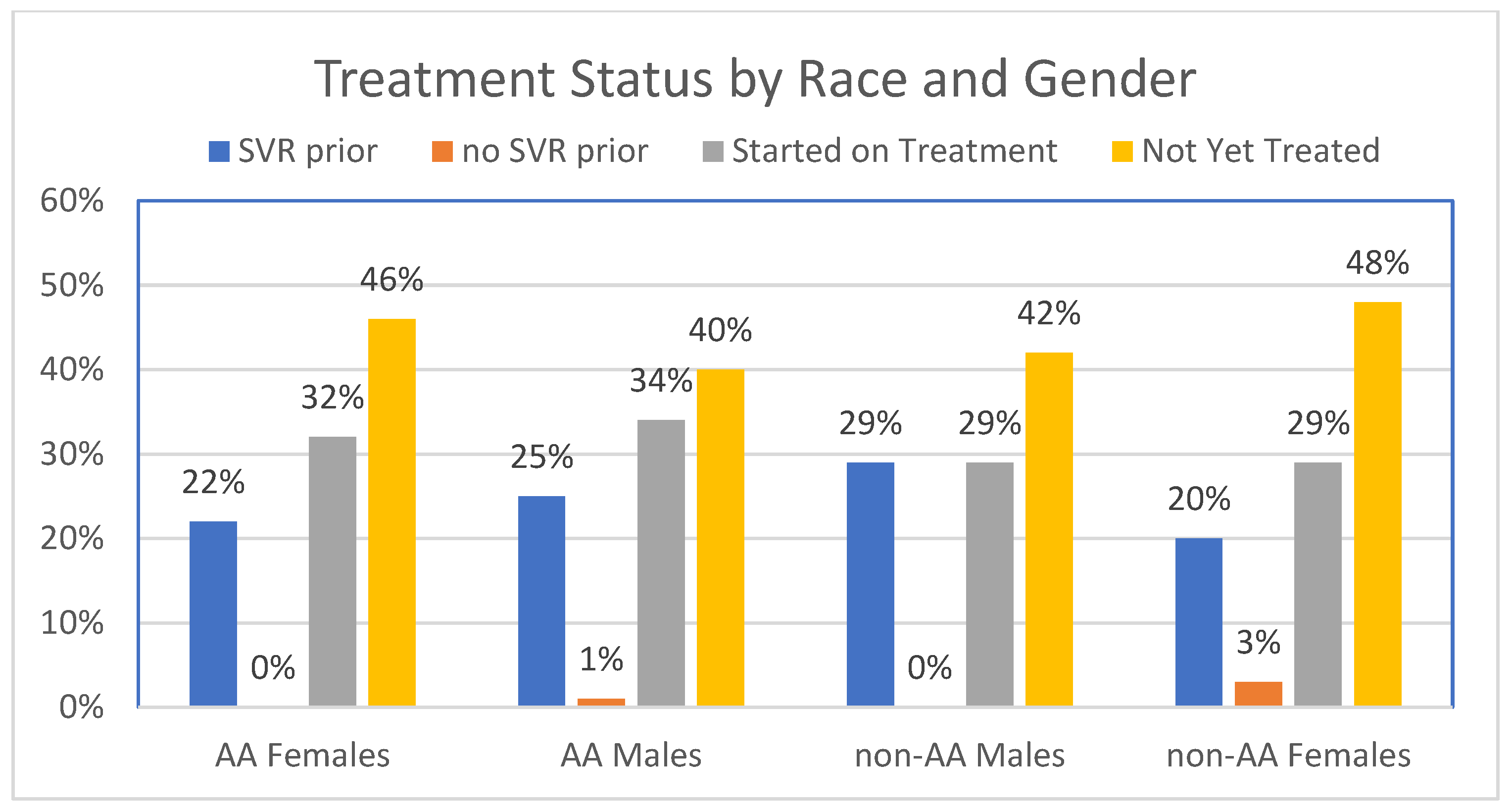

There were 587 patients with at least one visit in 2019. Treatment had been initiated in 140 patients prior to 2019 and an SVR was achieved in all but 6 of the 140 patients who initiated treatment prior to the 2019 visit (

Figure 1). The 6 patients seen in 2019 who had previously failed to achieve an SVR were not included in the untreated patient group. Of the 441 patients who were not yet treated at the first 2019 visit (441/587= 75%), only 189 (189/441 = 43%) were treated by July 2020. As shown in

Table 1 and

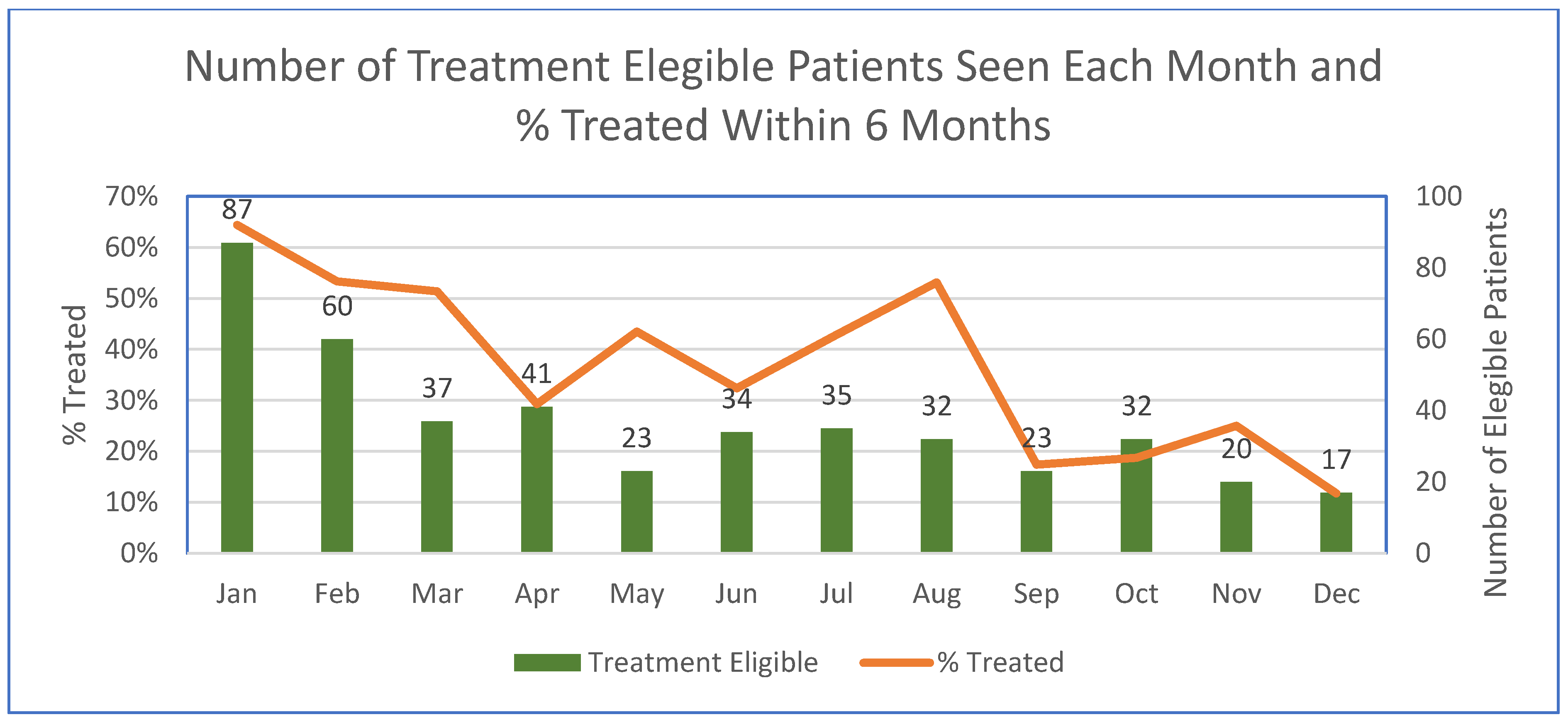

Figure 2, the number of total patients seen each month in 2019 declined from 114 in January to 25 in December. Also noted was a variation in the monthly percentage of patients who were eventually treated although the possibility that patients were seen for multiple visits prior to 2019 was not evaluated.

Neither race, nor gender were relevant to failure to treat (

Figure 1,

Table 2).

Table 3 presents the reason that patients were not treated. The dominant reason for not being treated was a lack of patient follow-up. With respect to comparing HCV patients who were treated or not treated,

Table 2 presents the data for a wide range of potential factors that could impact on treatment. Age for treated (61 years) vs Age for not treated (60 years) was not significantly different (p= 0.22). The primary reason for not treating was patient failure to follow up (n= 93; 76%). Insurance issues when mentioned in the EMR played a significantly lower part in failure to treat (15/252= 6%). Other reasons for not treating included drug or alcohol (9) and low fibrosis scores with failure to return (9). There were also 2 patients who were reluctant to agree to treatment. The dominance of follow up failures was true for both gender and race (

Figure 2,

Table 2). Most of our patients had Medicaid (n=133;53%) as their primary insurance, consistent with their being socioeconomically challenged. Medicare was the second most likely category of insurance (n=94; 37%) either due to age based retirement or disability. There was no relationship between the categories of insurance and the reason for not being treated. Treated and not treated HCV patients were also not different with respect to the clinic where seen (GI vs ID), the type of insurance and median income as defined by zip code. Somewhat unexpected was that of the 252 patients, 123 (49%) had more than one visit and yet were not treated. The degree of fibrosis (assessed by APRI and FIB-4) was not different between treated and not treated patients. This suggests that fibrosis assessment was not impacting on treatment decisions and that delaying treatment for fibrosis assessment was not needed. Patients with an average of 4 visits were more likely to be treated than those with 2 and having 1 visit with no follow-up was the most dramatic factor for patient treatment (42% vs 8% p<0.0001). PCR available at first visit to confirm infection was an important factor with respect to treatment (treated 38% vs not treated 25% p<0.02). Patients with a first visit early in 2019 were more likely to be subsequently treated than patients seen later despite the criteria of treatment being extended through the first 6 months of 2020.

4. Discussion

Consistent with results reported in the literature, significant numbers of our patients (57%) failed to be treated after a clinic visit. This low rate of treatment continues to be a reason that elimination of HCV remains elusive [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Perhaps more striking is the CDC report that there was a decline by half in the numbers of HCV patients treated between 2016 and 2020. While many of our patients were socioeconomically challenged as defined by Medicaid insurance, insurance was not a significant barrier to treatment even though in 2019, many of the Medicaid based insurances plans continued to require prior authorization for treatment. The primary reason for not being treated was the requirement of multiple visit for treatment with the subsequent failure of the patient to return for treatment after an initial visit [

14,

15]. We could not find any differences that predicted patients who would not be treated (or even fail to follow up) with the exception for patients with PCR confirmation of infection at first visit who were subsequently more likely to be treated. While there have been multiple studies identifying psychosocial issues, the major confounding issue remains the need for multiple visit prior to treatment and the failure of eligible patients to keep appointments. While issues such as substance abuse may be contributing factors, others include more seemingly mundane issue such as transportation and reliable methods for communication with respect to reminders of appointments continue to plague many patients.

With respect to the issue of whether GI or ID should be the sole providers of HCV treatment, our study clearly demonstrates that in 2019 at our institution, most patients (75%) were seen by GI with the remaining 25% being seen and treated by ID. No patients were treated outside of the two specialties. Several studies have suggested an increase in treatment rates could be achieved by treatment in primary care but data supporting that remains controversial, especially in settings like the US where multiple insurance payment models can create barriers to non-specialist care [

11,

12,

13]. It is important to note that our study does not focus on the issue of identifying and linking patients to HCV treatment evaluation since most patients come to the clinic via a referral from a primary care provider. While the issue of linkage to care as defined by a visit to GI or ID was not addressed, this study demonstrates that a significant number of patients who have been identified and subsequently linked to a specialist for care fail to be treated for their HCV.

While there is speculation about the possibility that poor health literacy and/or the presence of social determinants of health issues (SDOH) may play a role, studies to prospectively assess these issues with validated questionnaires are needed. The decline in patient visits from the beginning to end of 2019 and the fact that the number of patients treated decreased was unexpected and warrants further evaluation. With respect to this study, it is noted that the patients had their first visits in 2019 which is prior to the beginning of the COVID period in 2020. Studies to assess the issue of treatment in 2023 which would be post COVD are clearly warranted to obtain a clearer picture of treatment rates in the era of early treatment recommendation.

Since the degree of fibrosis has no impact on treatment, initiating treatment immediately after confirming infection with HCV should improve patient outcomes and may be the most successful way to improve treatment rates. The failure to treat patients with multiple visits does need further investigation since the second visits should clearly have defined the patient infection by PCR. This study also suggests that a policy to initiate treatment immediately upon confirmation of infection via PCR would significantly improve linkage to care.

Author Contributions

CA: data collection, manuscript preparation. RK: data collection, manuscript preparation. PN: Conception, data collection and curation, manuscript preparation. MM: supervision manuscript review.

Funding

No funding was available for this project and manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The project was approved by the Wayne State University Institutional Review Board.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest with respect to the project.

References

- Lewis, K.C.; Barker, L.K.; Jiles, R.B.; Gupta, N. Estimated Prevalence and Awareness of Hepatitis C Virus Infection Among US Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, January 2017–March 2020. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2023, 77, 1413–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asselah, T.; Marcellin, P.; Schinazi, R.F. Treatment of hepatitis C virus infection with direct-acting antiviral agents: 100% cure? Liver Int. 2018, 38 (Suppl. 1), 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakobsen, J.C.; Nielsen, E.E.; Feinberg, J.; Katakam, K.K.; Fobian, K.; Hauser, G.; et al. Direct-acting antivirals for chronic hepatitis C. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017, 9, CD012143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, V.H.; Huang, D.Q.; Le, M.H.; Jin, M.; Lee, E.Y.; Henry, L.; et al. Global treatment rate and barriers to direct-acting antiviral therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 146 studies and 1 760 352 hepatitis C virus patients. Liver International 2023, 43, 1195–1203. [PubMed]

- Nguyen, V.H.; Leslie, B.A.; Kam, M.D.; Yeo, Y.H.; Huang, D.Q.; Henry, L.; et al. Characteristics and Treatment Rate of Patients With Hepatitis C Virus Infection in the Direct-Acting Antiviral Era and During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States JAMA Network Open. 2022, 5, e2245424. [PubMed]

- Malespin, M.; Harris, C.; Kanar, O.; Jackman, K.; Smotherman, C.; Johnston, A.; et al. Barriers to treatment of chronic hepatitis C with direct acting antivirals in an urban clinic. Ann Hepatol. 2019, 18, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Con, P.; Wilson, D.L.; Tang, H.; Unigwe, I.; Riaz, M.; Ourhaan, N.; et al. Hepatitis C Cascade of Care in the Direct-Acting Antivirals Era: A Meta-Analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2023, 65, 1153–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, N.; Bruneau, J.; Makarenko, I.; Minoyan, N.; Zang, G.; Høj, S.B.; et al. HCV treatment initiation in the era of universal direct acting antiviral coverage - Improvements in access and persistent barriers. Int J Drug Policy. 2023, 113, 103954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. New estimates reveal declines in hepatitis C treatment in the US between 2015 and 2020. November 8, 2021. Accessed October 31, 2022.

- Millman, A.J.; Ntiri-Reid, B.; Irvin, R.; Kaufmann, M.H.; Aronsohn, A.; Duchin, J.S.; Scott, J.D.; Vellozzi, C. Barriers to Treatment Access for Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection: A Case Series. Top Antivir Med. 2017, 25, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blach, S.; Terrault, N.A.; Tacke, F.; Gamkrelidze, I.; Craxi, A.; Tanaka, J.; et al. Global change in hepatitis C virus prevalence and cascade of care between 2015 and 2020: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022, 7, 396–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, A.; Craig-Neil, A.; Hodwitz, K.; Wang, R.; Cheng, D.; Arbess, G.; Jeon, C.; Juando-Prats, C.; Kiran, T. Increasing treatment rates for hepatitis C in primary care. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 2023, 36, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kattakuzhy, S.; Gross, C.; Emmanuel, B.; Teferi, G.; Jenkins, V.; Silk, R.; et al. Expansion of Treatment for Hepatitis C Virus Infection by Task Shifting to Community-Based Nonspecialist Providers: A Nonrandomized Clinical Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2017, 167, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, P.; Vutien, P.; Hoang, J.; Trinh, S.; Le, A.; Yasukawa, L.A.; et al. Barriers to care for chronic hepatitis C in the direct-acting antiviral era: a single-center experience. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2017, 4, e000181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, S.A.; Sulkowski, M.S. Chronic Hepatitis C: Advances in Therapy and the Remaining Challenges. Med Clin North Am. 2023, 107, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).